Trade Schools, Colleges and Universities

Join Over 1.5 Million People We've Introduced to Awesome Schools Since 2001

Where do you want to study?

What do you want to study?

What's your {{waterMark}} code?

Trade Schools Home > Articles > Issues in Education

Major Issues in Education: 20 Hot Topics (From Grade School to College)

By Publisher | Last Updated August 1, 2023

In America, issues in education are big topics of discussion, both in the news media and among the general public. The current education system is beset by a wide range of challenges, from cuts in government funding to changes in disciplinary policies—and much more. Everyone agrees that providing high-quality education for our citizens is a worthy ideal. However, there are many diverse viewpoints about how that should be accomplished. And that leads to highly charged debates, with passionate advocates on both sides.

Understanding education issues is important for students, parents, and taxpayers. By being well-informed, you can contribute valuable input to the discussion. You can also make better decisions about what causes you will support or what plans you will make for your future.

This article provides detailed information on many of today's most relevant primary, secondary, and post-secondary education issues. It also outlines four emerging trends that have the potential to shake up the education sector. You'll learn about:

- 13 major issues in education at the K-12 level

- 7 big issues in higher education

- 5 emerging trends in education

13 Major Issues in Education at the K-12 Level

1. Government funding for education

School funding is a primary concern when discussing current issues in education. The American public education system, which includes both primary and secondary schools, is primarily funded by tax revenues. For the 2021 school year, state and local governments provided over 89 percent of the funding for public K-12 schools. After the Great Recession, most states reduced their school funding. This reduction makes sense, considering most state funding is sourced from sales and income taxes, which tend to decrease during economic downturns.

However, many states are still giving schools less cash now than they did before the Great Recession. A 2022 article from the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities (CBPP) notes that K-12 education is set to receive the largest-ever one-time federal investment. However, the CBPP also predicts this historic funding might fall short due to pandemic-induced education costs. The formulas that states use to fund schools have come under fire in recent years and have even been the subjects of lawsuits. For example, in 2017, the Kansas Supreme Court ruled that the legislature's formula for financing schools was unconstitutional because it didn't adequately fund education.

Less funding means that smaller staff, fewer programs, and diminished resources for students are common school problems. In some cases, schools are unable to pay for essential maintenance. A 2021 report noted that close to a quarter of all U.S. public schools are in fair or poor condition and that 53 percent of schools need renovations and repairs. Plus, a 2021 survey discovered that teachers spent an average of $750 of their own money on classroom supplies.

The issue reached a tipping point in 2018, with teachers in Arizona, Colorado, and other states walking off the job to demand additional educational funding. Some of the protests resulted in modest funding increases, but many educators believe that more must be done.

2. School safety

Over the past several years, a string of high-profile mass shootings in U.S. schools have resulted in dozens of deaths and led to debates about the best ways to keep students safe. After 17 people were killed in a shooting at a high school in Parkland, Florida in 2018, 57 percent of teenagers said they were worried about the possibility of gun violence at their school.

Figuring out how to prevent such attacks and save students and school personnel's lives are problems faced by teachers all across America.

Former President Trump and other lawmakers suggested that allowing specially trained teachers and other school staff to carry concealed weapons would make schools safer. The idea was that adult volunteers who were already proficient with a firearm could undergo specialized training to deal with an active shooter situation until law enforcement could arrive. Proponents argued that armed staff could intervene to end the threat and save lives. Also, potential attackers might be less likely to target a school if they knew that the school's personnel were carrying weapons.

Critics argue that more guns in schools will lead to more accidents, injuries, and fear. They contend that there is scant evidence supporting the idea that armed school officials would effectively counter attacks. Some data suggests that the opposite may be true: An FBI analysis of active shooter situations between 2000 and 2013 noted that law enforcement personnel who engaged the shooter suffered casualties in 21 out of 45 incidents. And those were highly trained professionals whose primary purpose was to maintain law and order. It's highly unlikely that teachers, whose focus should be on educating children, would do any better in such situations.

According to the National Education Association (NEA), giving teachers guns is not the answer. In a March 2018 survey , 74 percent of NEA members opposed arming school personnel, and two-thirds said they would feel less safe at work if school staff were carrying guns. To counter gun violence in schools, the NEA supports measures like requiring universal background checks, preventing mentally ill people from purchasing guns, and banning assault weapons.

3. Disciplinary policies

Data from the U.S. Department of Education Office for Civil Rights in 2021 suggests that black students face disproportionately high rates of suspension and expulsion from school. For instance, in K-12 schools, black male students make up only 7.7 percent of enrollees but account for over 40% percent of suspensions. Many people believe some teachers apply the rules of discipline in a discriminatory way and contribute to what has been termed the "school-to-prison pipeline." That's because research has demonstrated that students who are suspended or expelled are significantly more likely to become involved with the juvenile justice system.

In 2014, the U.S. Department of Justice and the Department of Education issued guidelines for all public schools on developing disciplinary practices that reduce disparities and comply with federal civil rights laws. The guidelines urged schools to limit exclusionary disciplinary tactics such as suspension and expulsion. They also encourage the adoption of more positive interventions such as counseling and restorative justice strategies. In addition, the guidelines specified that schools could face a loss of federal funds if they carried out policies that had a disparate impact on some racial groups.

Opponents argue that banning suspensions and expulsions takes away valuable tools that teachers can use to combat student misbehavior. They maintain that as long as disciplinary policies are applied the same way to every student regardless of race, such policies are not discriminatory. One major 2014 study found that the racial disparities in school suspension rates could be explained by the students' prior behavior rather than by discriminatory tactics on the part of educators.

In 2018, the Federal Commission on School Safety (which was established in the wake of the school shootings in Parkland, Florida) was tasked with reviewing and possibly rescinding the 2014 guidelines. According to an Education Next survey taken shortly after the announced review, only 27 percent of Americans support federal policies that limit racial disparities in school discipline.

4. Technology in education

Technology in education is a powerful movement that is sweeping through schools nationwide. After all, today's students have grown up with digital technology and expect it to be part of their learning experience. But how much of a role should it play in education?

Proponents point out that educational technology offers the potential to engage students in more active learning, as evidenced in flipped classrooms . It can facilitate group collaboration and provide instant access to up-to-date resources. Teachers and instructors can integrate online surveys, interactive case studies, and relevant videos to offer content tailored to different learning styles. Indeed, students with special needs frequently rely on assistive technology to communicate and access course materials.

But there are downsides as well. For instance, technology can be a distraction. Some students tune out of lessons and spend time checking social media, playing games, or shopping online. One research study revealed that students who multitasked on laptops during class scored 11 percent lower on an exam that tested their knowledge of the lecture. Students who sat behind those multitaskers scored 17 percent lower. In the fall of 2017, University of Michigan professor Susan Dynarski cited such research as one of the main reasons she bans electronics in her classes.

More disturbingly, technology can pose a real threat to student privacy and security. The collection of sensitive student data by education technology companies can lead to serious problems. In 2017, a group called Dark Overlord hacked into school district servers in several states and obtained access to students' personal information, including counselor reports and medical records. The group used the data to threaten students and their families with physical violence.

5. Charter schools and voucher programs

School choice is definitely among the hot topics in education these days. Former U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos was a vocal supporter of various forms of parental choice, including charter schools and school vouchers.

Charter schools are funded through a combination of public and private money and operate independently of the public system. They have charters (i.e., contracts) with school districts, states, or private organizations. These charters outline the academic outcomes that the schools agree to achieve. Like mainstream public schools, charter schools cannot teach religion or charge tuition, and their students must complete standardized testing . However, charter schools are not limited to taking students in a certain geographic area. They have more autonomy to choose their teaching methods. Charter schools are also subject to less oversight and fewer regulations.

School vouchers are like coupons that allow parents to use public funds to send their child to the school of their choice, which can be private and may be either secular or religious. In many cases, vouchers are reserved for low-income students or students with disabilities.

Advocates argue that charter schools and school vouchers offer parents a greater range of educational options. Opponents say that they privatize education and siphon funding away from regular public schools that are already financially strapped. The 2018 Education Next survey found that 44 percent of the general public supports charter schools' expansion, while 35 percent oppose such a move. The same poll found that 54 percent of people support vouchers.

6. Common Core

The Common Core State Standards is a set of academic standards for math and language arts that specify what public school students are expected to learn by the end of each year from kindergarten through 12th grade. Developed in 2009, the standards were designed to promote equity among public K-12 students. All students would take standardized end-of-year tests and be held to the same internationally benchmarked standards. The idea was to institute a system that brought all schools up to the same level and allowed for comparison of student performance in different regions. Such standards would help all students with college and career readiness.

Some opponents see the standards as an unwelcome federal intrusion into state control of education. Others are critical of the way the standards were developed with little input from experienced educators. Many teachers argue that the standards result in inflexible lesson plans that allow for less creativity and fun in the learning process.

Some critics also take issue with the lack of accommodation for non-traditional learners. The Common Core prescribes standards for each grade level, but students with disabilities or language barriers often need more time to fully learn the material.

The vast majority of states adopted the Common Core State Standards when they were first introduced. Since then, more than a dozen states have either repealed the standards or revised them to align better with local needs. In many cases, the standards themselves have remained virtually the same but given a different name.

And a name can be significant. In the Education Next 2018 survey, a group of American adults was asked whether they supported common standards across states. About 61 percent replied that they did. But when another group was polled about Common Core specifically, only 45 percent said they supported it.

7. Standardized testing

During the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) years, schools—and teachers—were judged by how well students scored on such tests. Schools whose results weren't up to par faced intense scrutiny, and in some cases, state takeover or closure. Teachers' effectiveness was rated by how much improvement their students showed on standardized exams. The Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), which took effect in 2016, removed NCLB's most punitive aspects. Still, it maintained the requirement to test students every year in Grades 3 to 8, and once in high school.

But many critics say that rampant standardized testing is one of the biggest problems in education. They argue that the pressure to produce high test scores has resulted in a teach-to-the-test approach to instruction in which other non-tested subjects (such as art, music, and physical education) have been given short shrift to devote more time to test preparation. And they contend that policymakers overemphasize the meaning of standardized test results, which don't present a clear or complete picture of overall student learning.

8. Teacher salaries

According to 2021-22 data from the National Center for Education Statistics (NCES), in most states, teacher pay has decreased over the last several years. However, in some states average salaries went up. It's also important to note that public school teachers generally enjoy pensions and other benefits that make up a large share of their compensation.

But the growth in benefits has not been enough to balance out the overall low wages. An Economic Policy Institute report found that even after factoring in benefits, public-sector teachers faced a compensation penalty of 14.2 percent in 2021 relative to other college graduates.

9. The teaching of evolution

In the U.S., public school originated to spread religious ideals, but it has since become a strictly secular institution. And the debate over how to teach public school students about the origins of life has gone on for almost a century.

Today, Darwin's theory of evolution through natural selection is accepted by virtually the entire scientific community. However, it is still controversial among many Americans who maintain that living things were guided into existence. A pair of surveys from 2014 revealed that 98 percent of scientists aligned with the American Association for the Advancement of Science believed that humans evolved. But it also revealed that, overall, only 52 percent of American adults agreed.

Over the years, some states have outright banned teachers from discussing evolution in the classroom. Others have mandated that students be allowed to question the scientific soundness of evolution, or that equal time be given to consideration of the Judeo-Christian notion of divine creation (i.e., creationism).

Some people argue that the theory of intelligent design—which posits that the complexities of living things cannot be explained by natural selection and can best be explained as resulting from an intelligent cause—is a legitimate scientific theory that should be allowed in public school curricula. They say it differs from creationism because it doesn't necessarily ascribe life's design to a supernatural deity or supreme being.

Opponents contend that intelligent design is creationism in disguise. They think it should not be taught in public schools because it is religiously motivated and has no credible scientific basis. And the courts have consistently held that the teaching of creationism and intelligent design promotes religious beliefs and therefore violates the Constitution's prohibition against the government establishment of religion. Still, the debate continues.

10. Teacher tenure

Having tenure means that a teacher cannot be let go unless their school district demonstrates just cause. Many states grant tenure to public school teachers who have received satisfactory evaluations for a specified period of time (which ranges from one to five years, depending on the state). A few states do not grant tenure at all. And the issue has long been mired in controversy.

Proponents argue that tenure protects teachers from being dismissed for personal or political reasons, such as disagreeing with administrators or teaching contentious subjects such as evolution. Tenured educators can advocate for students without fear of reprisal. Supporters also say that tenure gives teachers the freedom to try innovative instruction methods to deliver more engaging educational experiences. Tenure also protects more experienced (and more expensive) teachers from being arbitrarily replaced with new graduates who earn lower salaries.

Critics contend that tenure makes it difficult to dismiss ineffectual teachers because going through the legal process of doing so is extremely costly and time-consuming. They say that tenure can encourage complacency since teachers' jobs are secure whether they exceed expectations or just do the bare minimum. Plus, while the granting of tenure often hinges on teacher evaluations, 2017 research found that, in practice, more than 99 percent of teachers receive ratings of satisfactory or better. Some administrators admit to being reluctant to give low ratings because of the time and effort required to document teachers' performance and provide support for improvement.

11. Bullying

Bullying continues to be a major issue in schools all across the U.S. According to a National Center for Education Statistics study , around 22 percent of students in Grades 6 through 12 reported having been bullied at school, or on their way to or from school, in 2019. That figure was down from 28 percent in 2009, but it is still far too high.

The same study revealed that over 22 percent of students reported being bullied once a day, and 6.3 percent reported experiencing bullying two to ten times in a day. In addition, the percentage of students who reported the bullying to an adult was over 45 percent in 2019.

But that still means that almost 60 percent of students are not reporting bullying. And that means children are suffering.

Bullied students experience a range of emotional, physical, and behavioral problems. They often feel angry, anxious, lonely, and helpless. They are frequently scared to go to school, leading them to suffer academically and develop a low sense of self-worth. They are also at greater risk of engaging in violent acts or suicidal behaviors.

Every state has anti-bullying legislation in place, and schools are expected to develop policies to address the problem. However, there are differences in how each state defines bullying and what procedures it mandates when bullying is reported. And only about one-third of states call for school districts to include provisions for support services such as counseling for students who are victims of bullying (or are bullies themselves).

12. Poverty

Student poverty is a growing problem. Data from the National Center for Education Statistics show that as of the 2019-2020 school year, low-income students comprised a majority (52 percent) of public school students in the U.S. That represented a significant increase from 2000-2001, when only 38 percent of students were considered low-income (meaning they qualified for free or discounted school lunches).

The numbers are truly alarming: In 39 states, at least 40 percent of public school enrollees were eligible to receive free or reduced-price lunches, and 22 of those states had student poverty rates of 50 percent or more.

Low-income students tend to perform worse in school than their more affluent peers. Studies have shown that family income strongly correlates to student achievement on standardized tests. That may be partly because parents with fewer financial resources generally can't afford tutoring and other enrichment experiences to boost student achievement. In addition, low-income children are much more likely to experience food instability, family turmoil, and other stressors that can negatively affect their academic success.

All of this means that teachers face instructional challenges that go beyond students' desires to learn.

13. Class size

According to NCES data , in the 2017-2018 school year, the average class size in U.S. public schools was 26.2 students at the elementary level and 23.3 students at the secondary level.

But anecdotal reports suggest that today, classrooms commonly have more than 30 students—sometimes as many as 40.

Conventional wisdom holds that smaller classes are beneficial to student learning. Teachers often argue that the size of a class greatly influences the quality of the instruction they are able to provide. Research from the National Education Policy Center in 2016 showed smaller classes improve student outcomes, particularly for early elementary, low-income, and minority students.

Many (but not all) states have regulations in place that impose limits on class sizes. However, those limits become increasingly difficult to maintain in an era of budget constraints. Reducing class sizes requires hiring more teachers and constructing new classrooms. Arguably, allowing class sizes to expand can enable districts to absorb funding cuts without making reductions to other programs such as art and physical education.

7 Big Issues in Higher Education

1. Student loan forgiveness

Here's how the American public education system works: Students attend primary and secondary school at no cost. They have the option of going on to post-secondary training (which, for most students, is not free). So with costs rising at both public and private institutions of higher learning, student loan debt is one of the most prominent issues in education today. Students who graduated from college in 2022 came out with an average debt load of $37,338. As a whole, Americans owe over $1.7 trillion in student loans.

Currently, students who have received certain federal student loans and are on income-driven repayment plans can qualify to have their remaining balance forgiven if they haven't repaid the loan in full after 20 to 25 years, depending on the plan. Additionally, the Public Service Loan Forgiveness (PSLF) program allows qualified borrowers who go into public service careers (such as teaching, government service, social work, or law enforcement) to have their student debt canceled after ten years.

However, potential changes are in the works. The Biden-Harris Administration is working to support students and make getting a post-secondary education more affordable. In 2022, the U.S. Department of Education provided more than $17 billion in loan relief to over 700,000 borrowers. Meanwhile, a growing number of Democrats are advocating for free college as an alternative to student loans.

2. Completion rates

The large number of students who begin post-secondary studies but do not graduate continues to be an issue. According to a National Student Clearinghouse Research Center report , the overall six-year college completion rate for the cohort entering college in 2015 was 62.2 percent. Around 58 percent of students completed a credential at the same institution where they started their studies, and about another 8 percent finished at a different institution.

Completion rates are increasing, but there is still concern over the significant percentage of college students who do not graduate. Almost 9 percent of students who began college in 2015 had still not completed a degree or certificate six years later. Over 22 percent of them had dropped out entirely.

Significant costs are associated with starting college but not completing it. Many students end up weighed down by debt, and those who do not complete their higher education are less able to repay loans. Plus, students miss out on formal credentials that could lead to higher earnings. Numbers from the Bureau of Labor Statistics show that in 2021 students who begin college but do not complete a degree have median weekly earnings of $899. By contrast, associate degree holders have median weekly wages of $963, and bachelor's degree recipients have median weekly earnings of $1,334.

Students leave college for many reasons, but chief among them is money. To mitigate that, some institutions have implemented small retention or completion grants. Such grants are for students who are close to graduating, have financial need, have used up all other sources of aid, owe a modest amount, and are at risk of dropping out due to lack of funds. One study found that around a third of the institutions who implemented such grants noted higher graduation rates among grant recipients.

3. Student mental health

Mental health challenges among students are a growing concern. A survey by the American College Health Association in the spring of 2019 found that over two-thirds of college students had experienced "overwhelming anxiety" within the previous 12 months. Almost 45 percent reported higher-than-average stress levels.

Anxiety, stress, and depression were the most common concerns among students who sought treatment. The 2021 report by the Center for Collegiate Mental Health (CCMH) noted the average number of appointments students needed has increased by 20 percent.

And some schools are struggling to keep up. A 2020 report found that the average student-to-clinician ratio on U.S. campuses was 1,411 to 1. So, in some cases, suffering students face long waits for treatment.

4. Sexual assault

The Bureau of Justice Statistics reports that more than 75 percent of sexual assaults are not reported to law enforcement, so the actual number of incidents could be much higher.

And the way that colleges and universities deal with sexual assault is undergoing changes. Title IX rules makes sure that complaints of sexual assault or harassment are taken seriously and ensuring the accused person is treated fairly.

Administrators were also required to adjudicate such cases based on a preponderance of evidence, meaning that they had to believe that it was more likely than not that an accused was guilty in order to proceed with disciplinary action. The "clear and convincing" evidentiary standard, which required that administrators be reasonably certain that sexual violence or harassment occurred, was deemed unacceptable.

Critics argued that the guidelines failed to respect the due process rights of those accused of sexual misconduct. Research has found that the frequency of false sexual assault allegations is between two and 10 percent.

In 2017, the Trump administration rescinded the Obama-era guidelines. The intent was to institute new regulations on how schools should handle sexual assault allegations. The changes went into effect on August 14, 2020, defining sexual harassment more narrowly and only requiring schools to investigate formal complaints about on-campus incidents officially filed with designated authorities, such as Title IX coordinators. The updated guidelines also allow schools to use the clear and convincing standard for conviction.

Victims' rights advocates were concerned this approach would deter victims from coming forward and hinder efforts to create safe learning environments.

The Biden administration is expected to release their proposed revisions to Title IX in October 2023 which could see many of the Trump administration changes rescinded.

5. Trigger warnings

The use of trigger warnings in academia is a highly contentious issue. Trigger warnings alert students that upcoming course material contains concepts or images that may invoke psychological or physiological reactions in people who have experienced trauma. Some college instructors provide such warnings before introducing films, texts, or other content involving things like violence or sexual abuse. The idea is to give students advance notice so that they can psychologically prepare themselves.

Some believe that trigger warnings are essential because they allow vulnerable people to prepare for and navigate difficult content. Having trigger warnings allows students with post-traumatic stress to decide whether they will engage with the material or find an alternative way to acquire the necessary information.

Critics argue that trigger warnings constrain free speech and academic freedom by discouraging the discussion of topics that might trigger distressing reactions in some students. They point out that college faculty already provide detailed course syllabi and that it's impossible to anticipate and acknowledge every potential trigger.

In 2015, NPR Ed surveyed more than 800 faculty members at higher education institutions across the U.S. and found that around half had given trigger warnings before bringing up potentially disturbing course material. Most did so on their own initiative, not in response to administrative policy or student requests. Few schools either mandate or prohibit trigger warnings. One notable exception is the University of Chicago, which in 2016 informed all incoming first-year students that it did not support such warnings.

6. College accreditation

In order to participate in federal student financial aid programs, institutions of higher education must be accredited by an agency that is recognized by the U.S. Department of Education. By law, accreditors must consider factors such as an institution's facilities, equipment, curricula, admission practices, faculty, and support services. The idea is to enforce an acceptable standard of quality.

But while federal regulations require accreditors to assess each institution's "success with respect to student achievement," they don't specify how to measure such achievement. Accreditors are free to define that for themselves. Unfortunately, some colleges with questionable practices, low graduation rates, and high student loan default rates continue to be accredited. Critics argue that accreditors are not doing enough to ensure that students receive good value for their money.

7. College rankings

Every year, prospective college students and their families turn to rankings like the ones produced by U.S. News & World Report to compare different institutions of higher education. Many people accept such rankings as authoritative without truly understanding how they are calculated or what they measure.

It's common for ranking organizations to refine their methodologies from year to year and change how they weigh various factors—which means it's possible for colleges to rise or fall in the rankings despite making no substantive changes to their programs or institutional policies. That makes it difficult to compare rankings from one year to the next, since things are often measured differently.

For colleges, a higher ranking can lead to more visibility, more qualified applicants, and more alumni donations (in short: more money). And the unfortunate reality is that some schools outright lie about test scores, graduation rates, or financial information in their quest to outrank their competitors.

Others take advantage of creative ways to game the system. For example, U.S. News looks at the test scores of incoming students at each institution, but it only looks at students who begin in the fall semester. One school instituted a program where students with lower test scores could spend their first semester in a foreign country and return to the school in the spring, thus excluding them from the U.S. News calculations.

Rankings do make useful information about U.S. colleges and universities available to all students and their families. But consumers should be cautious about blindly accepting such rankings as true measures of educational quality.

5 Emerging Trends in Education

1. Maker learning

The maker movement is rapidly gaining traction in K-12 schools across America. Maker learning is based on the idea that you will engage students in learning by encouraging interest-driven problem solving and hands-on activities (i.e., learning by doing). In collaborative spaces, students identify problems, dream up inventions, make prototypes, and keep tinkering until they develop something that makes sense. It's a do-it-yourself educational approach that focuses on iterative trial and error and views failure as an opportunity to refine and improve.

Maker education focuses on learning rather than teaching. Students follow their interests and test their own solutions. For example, that might mean creating a video game, building a rocket, designing historical costumes, or 3D-printing an irrigation system for a garden. It can involve high-tech equipment, but it doesn't have to. Repurposing whatever materials are on hand is an important ideal of the maker philosophy.

There is little hard data available on the maker trend. However, researchers at Rutgers University are currently studying the cognitive basis for maker education and investigating its connection to meaningful learning.

2. Moving away from letter grades

Many education advocates believe that the traditional student assessment models place too much emphasis on standardization and testing. They feel that traditional grading models do not sufficiently measure many of the most prized skills in the 21st-century workforce, such as problem-solving, self-advocacy, and creativity. As a result, a growing number of schools around the U.S. are replacing A-F letter grades with new assessment systems.

Formed in 2017, the Mastery Transcript Consortium is a group of more than 150 private high schools that have pledged to get rid of grade-based transcripts in favor of digital ones that provide qualitative descriptions of student learning as well as samples of student work. Some of the most famous private institutions in America have signed on, including Dalton and Phillips Exeter.

The no-more-grades movement is taking hold in public schools as well. Many states have enacted policies to encourage public schools to use something other than grades to assess students' abilities. It's part of a larger shift toward what's commonly known as mastery-based or competency-based learning, which strives to ensure that students become proficient in defined areas of skill.

Instead of letter grades, report cards may feature phrases like "partially meets the standard" or "exceeds the standard." Some schools also include portfolios, capstone projects, or other demonstrations of student learning.

But what happens when it's time to apply to college? It seems that even colleges and universities are getting on board. At least 85 higher education institutions across New England (including Dartmouth and Harvard) have said that students with competency-based transcripts will not be disadvantaged during the admission process.

3. The rise of micro-credentials

Micro-credentials, also known as digital badges or nanodegrees, are mini qualifications that demonstrate a student's knowledge or skills in a given area. Unlike traditional college degrees that require studying a range of different subjects over a multi-year span, micro-credentials are earned through short, targeted education focused on specific skills in particular fields. They tend to be inexpensive (sometimes even free) and are typically taken online.

Some post-secondary schools are developing micro-credentialing partnerships with third-party learning providers, while other schools offer such solutions on their own. A 2020 Campus Technology article stated 70 percent of higher education institutions offer some type of alternative credentialing.

Micro-credentials can serve as evidence that students have mastered particular skills, but the rigor and market worth of such credentials can vary significantly. Still, they are an increasingly popular way of unbundling content and providing it on demand.

4. Flipped classrooms

A growing number of schools are embracing the notion of flipped learning. It's an instructional approach that reverses the traditional model of the teacher giving a lecture in front of the class, then sending students home to work through assignments that enhance their understanding of the concepts. In flipped learning, students watch lecture videos or read relevant course content on their own before class. Class time is devoted to expanding on the material through group discussions and collaborative learning projects (i.e., doing what was traditionally meant as homework). The instructor is there to guide students when questions or problems arise.

Provided that all students have access to the appropriate technology and are motivated to prepare for each class session, flipped learning can bring a wide range of benefits. For example, it allows students to control their own learning by watching lecture videos at their own pace; they can pause, jot down questions, or re-watch parts they find confusing. The model also encourages students to learn from each other and explore subjects more deeply.

Flipped learning is becoming widespread in all education levels, but it is especially prevalent at the college level. In a 2017 survey , 61 percent of college faculty had used the flipped model in some or all of their classes and another 24% of instructors were considering trying it.

5. Social-emotional learning

There is a growing consensus that schools are responsible for fostering students' social and emotional development and their cognitive skills. Social-emotional learning (SEL) focuses on helping students develop the abilities to identify their strengths, manage their emotions, set goals, show empathy, make responsible decisions, and build and maintain healthy relationships. Research has shown that such skills play a key role in reducing anti-social behavior, boosting academic achievement, and improving long-term health.

Every state has developed SEL competencies at the preschool level. The number of states with such competencies for higher grades is growing.

Explore Your Educational Options

Learning about current issues in education may have brought up some questions that could hold the key to the future you want to build. How do I get the skills I need for my chosen career? How can I learn more about the programs offered at trade schools near me ?

You can get started right here, right now. You can get started right here, right now. The search tool below will narrow down the best options based on your zip code. And these vocational schools are eager to provide the information you need to decide on the right fit for you.

"I recommend using Trade-Schools.net because you can find the program that you are interested in nearby or online. " Trade-Schools.net User

Related Articles

clock This article was published more than 2 years ago

Public education is facing a crisis of epic proportions

How politics and the pandemic put schools in the line of fire.

A previous version of this story incorrectly said that 39 percent of American children were on track in math. That is the percentage performing below grade level.

Test scores are down, and violence is up . Parents are screaming at school boards , and children are crying on the couches of social workers. Anger is rising. Patience is falling.

For public schools, the numbers are all going in the wrong direction. Enrollment is down. Absenteeism is up. There aren’t enough teachers, substitutes or bus drivers. Each phase of the pandemic brings new logistics to manage, and Republicans are planning political campaigns this year aimed squarely at failings of public schools.

Public education is facing a crisis unlike anything in decades, and it reaches into almost everything that educators do: from teaching math, to counseling anxious children, to managing the building.

Political battles are now a central feature of education, leaving school boards, educators and students in the crosshairs of culture warriors. Schools are on the defensive about their pandemic decision-making, their curriculums, their policies regarding race and racial equity and even the contents of their libraries. Republicans — who see education as a winning political issue — are pressing their case for more “parental control,” or the right to second-guess educators’ choices. Meanwhile, an energized school choice movement has capitalized on the pandemic to promote alternatives to traditional public schools.

“The temperature is way up to a boiling point,” said Nat Malkus, senior fellow at the American Enterprise Institute, a conservative-leaning think tank. “If it isn’t a crisis now, you never get to crisis.”

Experts reach for comparisons. The best they can find is the earthquake following Brown v. Board of Education , when the Supreme Court ordered districts to desegregate and White parents fled from their cities’ schools. That was decades ago.

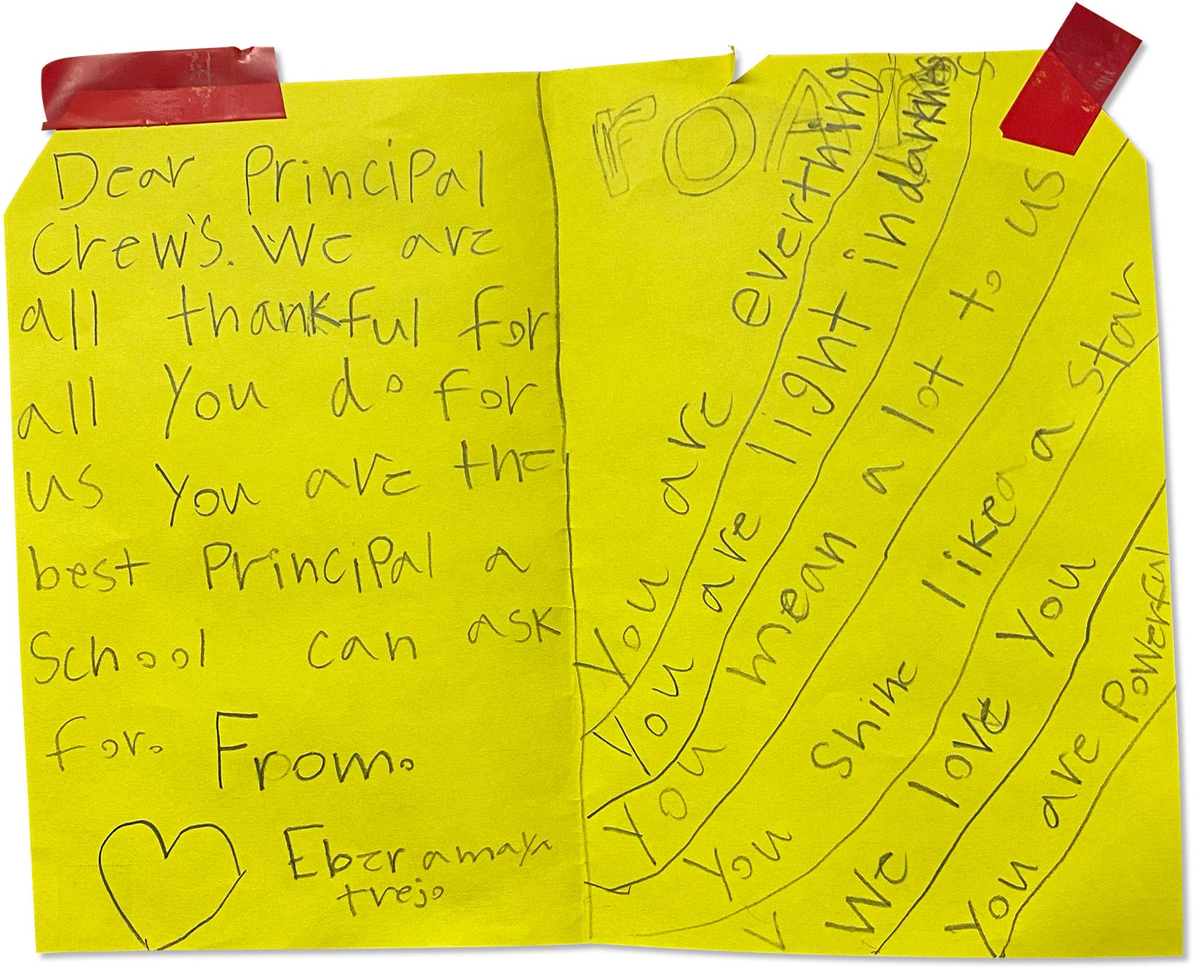

Today, the cascading problems are felt acutely by the administrators, teachers and students who walk the hallways of public schools across the country. Many say they feel unprecedented levels of stress in their daily lives.

Remote learning, the toll of illness and death, and disruptions to a dependable routine have left students academically behind — particularly students of color and those from poor families. Behavior problems ranging from inability to focus in class all the way to deadly gun violence have gripped campuses. Many students and teachers say they are emotionally drained, and experts predict schools will be struggling with the fallout for years to come.

Teresa Rennie, an eighth-grade math and science teacher in Philadelphia, said in 11 years of teaching, she has never referred this many children to counseling.

“So many students are needy. They have deficits academically. They have deficits socially,” she said. Rennie said that she’s drained, too. “I get 45 minutes of a prep most days, and a lot of times during that time I’m helping a student with an assignment, or a child is crying and I need to comfort them and get them the help they need. Or there’s a problem between two students that I need to work with. There’s just not enough time.”

Many wonder: How deep is the damage?

Learning lost

At the start of the pandemic, experts predicted that students forced into remote school would pay an academic price. They were right.

“The learning losses have been significant thus far and frankly I’m worried that we haven’t stopped sinking,” said Dan Goldhaber, an education researcher at the American Institutes for Research.

Some of the best data come from the nationally administered assessment called i-Ready, which tests students three times a year in reading and math, allowing researchers to compare performance of millions of students against what would be expected absent the pandemic. It found significant declines, especially among the youngest students and particularly in math.

The low point was fall 2020, when all students were coming off a spring of chaotic, universal remote classes. By fall 2021 there were some improvements, but even then, academic performance remained below historic norms.

Take third grade, a pivotal year for learning and one that predicts success going forward. In fall 2021, 38 percent of third-graders were below grade level in reading, compared with 31 percent historically. In math, 39 percent of students were below grade level, vs. 29 percent historically.

Damage was most severe for students from the lowest-income families, who were already performing at lower levels.

A McKinsey & Co. study found schools with majority-Black populations were five months behind pre-pandemic levels, compared with majority-White schools, which were two months behind. Emma Dorn, a researcher at McKinsey, describes a “K-shaped” recovery, where kids from wealthier families are rebounding and those in low-income homes continue to decline.

“Some students are recovering and doing just fine. Other people are not,” she said. “I’m particularly worried there may be a whole cohort of students who are disengaged altogether from the education system.”

A hunt for teachers, and bus drivers

Schools, short-staffed on a good day, had little margin for error as the omicron variant of the coronavirus swept over the country this winter and sidelined many teachers. With a severe shortage of substitutes, teachers had to cover other classes during their planning periods, pushing prep work to the evenings. San Francisco schools were so strapped that the superintendent returned to the classroom on four days this school year to cover middle school math and science classes. Classes were sometimes left unmonitored or combined with others into large groups of unglorified study halls.

“The pandemic made an already dire reality even more devastating,” said Becky Pringle, president of the National Education Association, referring to the shortages.

In 2016, there were 1.06 people hired for every job listing. That figure has steadily dropped, reaching 0.59 hires for each opening last year, Bureau of Labor Statistics data show. In 2013, there were 557,320 substitute teachers, the BLS reported. In 2020, the number had fallen to 415,510. Virtually every district cites a need for more subs.

It’s led to burnout as teachers try to fill in the gaps.

“The overall feelings of teachers right now are ones of just being exhausted, beaten down and defeated, and just out of gas. Expectations have been piled on educators, even before the pandemic, but nothing is ever removed,” said Jennifer Schlicht, a high school teacher in Olathe, Kan., outside Kansas City.

Research shows the gaps in the number of available educators are most acute in areas including special education and educators who teach English language learners, as well as substitutes. And all school year, districts have been short on bus drivers , who have been doubling up routes, and forcing late school starts and sometimes cancellations for lack of transportation.

Many educators predict that fed-up teachers will probably quit, exacerbating the problem. And they say political attacks add to the burnout. Teachers are under scrutiny over lesson plans, and critics have gone after teachers unions, which for much of the pandemic demanded remote learning.

“It’s just created an environment that people don’t want to be part of anymore,” said Daniel A. Domenech, executive director of AASA, The School Superintendents Association. “People want to take care of kids, not to be accused and punished and criticized.”

Falling enrollment

Traditional public schools educate the vast majority of American children, but enrollment has fallen, a worrisome trend that could have lasting repercussions. Enrollment in traditional public schools fell to less than 49.4 million students in fall 2020 , a 2.7 percent drop from a year earlier .

National data for the current school year is not yet available. But if the trend continues, that will mean less money for public schools as federal and state funding are both contingent on the number of students enrolled. For now, schools have an infusion of federal rescue money that must be spent by 2024.

Some students have shifted to private or charter schools. A rising number , especially Black families , opted for home schooling. And many young children who should have been enrolling in kindergarten delayed school altogether. The question has been: will these students come back?

Some may not. Preliminary data for 19 states compiled by Nat Malkus, of the American Enterprise Institute, found seven states where enrollment dropped in fall 2020 and then dropped even further in 2021. His data show 12 states that saw declines in 2020 but some rebounding in 2021 — though not one of them was back to 2019 enrollment levels.

Joshua Goodman, associate professor of education and economics at Boston University, studied enrollment in Michigan schools and found high-income, White families moved to private schools to get in-person school. Far more common, though, were lower-income Black families shifting to home schooling or other remote options because they were uncomfortable with the health risks of in person.

“Schools were damned if they did, and damned if they didn’t,” Goodman said.

At the same time, charter schools, which are privately run but publicly funded, saw enrollment increase by 7 percent, or nearly 240,000 students, according to the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools. There’s also been a surge in home schooling. Private schools saw enrollment drop slightly in 2020-21 but then rebound this academic year, for a net growth of 1.7 percent over two years, according to the National Association of Independent Schools, which represents 1,600 U.S. schools.

Absenteeism on the rise

Even if students are enrolled, they won’t get much schooling if they don’t show up.

Last school year, the number of students who were chronically absent — meaning they have missed more than 10 percent of school days — nearly doubled from before the pandemic, according to data from a variety of states and districts studied by EveryDay Labs, a company that works with districts to improve attendance.

This school year, the numbers got even worse.

In Connecticut, for instance, the number of chronically absent students soared from 12 percent in 2019-20 to 20 percent the next year to 24 percent this year, said Emily Bailard, chief executive of the company. In Oakland, Calif., they went from 17.3 percent pre-pandemic to 19.8 percent last school year to 43 percent this year. In Pittsburgh, chronic absences stayed where they were last school year at about 25 percent, then shot up to 45 percent this year.

“We all expected that this year would look much better,” Bailard said. One explanation for the rise may be that schools did not keep careful track of remote attendance last year and the numbers understated the absences then, she said.

The numbers were the worst for the most vulnerable students. This school year in Connecticut, for instance, 24 percent of all students were chronically absent, but the figure topped 30 percent for English-learners, students with disabilities and those poor enough to qualify for free lunch. Among students experiencing homelessness, 56 percent were chronically absent.

Fights and guns

Schools are open for in-person learning almost everywhere, but students returned emotionally unsettled and unable to conform to normally accepted behavior. At its most benign, teachers are seeing kids who cannot focus in class, can’t stop looking at their phones, and can’t figure out how to interact with other students in all the normal ways. Many teachers say they seem younger than normal.

Amy Johnson, a veteran teacher in rural Randolph, Vt., said her fifth-graders had so much trouble being together that the school brought in a behavioral specialist to work with them three hours each week.

“My students are not acclimated to being in the same room together,” she said. “They don’t listen to each other. They cannot interact with each other in productive ways. When I’m teaching I might have three or five kids yelling at me all at the same time.”

That loss of interpersonal skills has also led to more fighting in hallways and after school. Teachers and principals say many incidents escalate from small disputes because students lack the habit of remaining calm. Many say the social isolation wrought during remote school left them with lower capacity to manage human conflict.

Just last week, a high-schooler in Los Angeles was accused of stabbing another student in a school hallway, police on the big island of Hawaii arrested seven students after an argument escalated into a fight, and a Baltimore County, Md., school resource officer was injured after intervening in a fight during the transition between classes.

There’s also been a steep rise in gun violence. In 2021, there were at least 42 acts of gun violence on K-12 campuses during regular hours, the most during any year since at least 1999, according to a Washington Post database . The most striking of 2021 incidents was the shooting in Oxford, Mich., that killed four. There have been already at least three shootings in 2022.

Back to school has brought guns, fighting and acting out

The Center for Homeland Defense and Security, which maintains its own database of K-12 school shootings using a different methodology, totaled nine active shooter incidents in schools in 2021, in addition to 240 other incidents of gunfire on school grounds. So far in 2022, it has recorded 12 incidents. The previous high, in 2019, was 119 total incidents.

David Riedman, lead researcher on the K-12 School Shooting Database, points to four shootings on Jan. 19 alone, including at Anacostia High School in D.C., where gunshots struck the front door of the school as a teen sprinted onto the campus, fleeing a gunman.

Seeing opportunity

Fueling the pressure on public schools is an ascendant school-choice movement that promotes taxpayer subsidies for students to attend private and religious schools, as well as publicly funded charter schools, which are privately run. Advocates of these programs have seen the public system’s woes as an excellent opportunity to push their priorities.

EdChoice, a group that promotes these programs, tallies seven states that created new school choice programs last year. Some are voucher-type programs where students take some of their tax dollars with them to private schools. Others offer tax credits for donating to nonprofit organizations, which give scholarships for school expenses. Another 15 states expanded existing programs, EdChoice says.

The troubles traditional schools have had managing the pandemic has been key to the lobbying, said Michael McShane, director of national research for EdChoice. “That is absolutely an argument that school choice advocates make, for sure.”

If those new programs wind up moving more students from public to private systems, that could further weaken traditional schools, even as they continue to educate the vast majority of students.

Kevin G. Welner, director of the National Education Policy Center at the University of Colorado, who opposes school choice programs, sees the surge of interest as the culmination of years of work to undermine public education. He is both impressed by the organization and horrified by the results.

“I wish that organizations supporting public education had the level of funding and coordination that I’ve seen in these groups dedicated to its privatization,” he said.

A final complication: Politics

Rarely has education been such a polarizing political topic.

Republicans, fresh off Glenn Youngkin’s victory in the Virginia governor’s race, have concluded that key to victory is a push for parental control and “parents rights.” That’s a nod to two separate topics.

First, they are capitalizing on parent frustrations over pandemic policies, including school closures and mandatory mask policies. The mask debate, which raged at the start of the school year, got new life this month after Youngkin ordered Virginia schools to allow students to attend without face coverings.

The notion of parental control also extends to race, and objections over how American history is taught. Many Republicans also object to school districts’ work aimed at racial equity in their systems, a basket of policies they have dubbed critical race theory. Critics have balked at changes in admissions to elite school in the name of racial diversity, as was done in Fairfax, Va. , and San Francisco ; discussion of White privilege in class ; and use of the New York Times’s “1619 Project,” which suggests slavery and racism are at the core of American history.

“Everything has been politicized,” said Domenech, of AASA. “You’re beside yourself saying, ‘How did we ever get to this point?’”

Part of the challenge going forward is that the pandemic is not over. Each time it seems to be easing, it returns with a variant vengeance, forcing schools to make politically and educationally sensitive decisions about the balance between safety and normalcy all over again.

At the same time, many of the problems facing public schools feed on one another. Students who are absent will probably fall behind in learning, and those who fall behind are likely to act out.

A similar backlash exists regarding race. For years, schools have been under pressure to address racism in their systems and to teach it in their curriculums, pressure that intensified after the murder of George Floyd in 2020. Many districts responded, and that opened them up to countervailing pressures from those who find schools overly focused on race.

Some high-profile boosters of public education are optimistic that schools can move past this moment. Education Secretary Miguel Cardona last week promised, “It will get better.” Randi Weingarten, president of the American Federation of Teachers, said, “If we can rebuild community-education relations, if we can rebuild trust, public education will not only survive but has a real chance to thrive.”

But the path back is steep, and if history is a guide, the wealthiest schools will come through reasonably well, while those serving low-income communities will struggle. Steve Matthews, superintendent of the 6,900-student Novi Community School District in Michigan, just northwest of Detroit, said his district will probably face a tougher road back than wealthier nearby districts that are, for instance, able to pay teachers more.

“Resource issues. Trust issues. De-professionalization of teaching is making it harder to recruit teachers,” he said. “A big part of me believes schools are in a long-term crisis.”

Valerie Strauss contributed to this report.

The pandemic’s impact on education

The latest: Updated coronavirus booster shots are now available for children as young as 5 . To date, more than 10.5 million children have lost one or both parents or caregivers during the coronavirus pandemic.

In the classroom: Amid a teacher shortage, states desperate to fill teaching jobs have relaxed job requirements as staffing crises rise in many schools . American students’ test scores have even plummeted to levels unseen for decades. One D.C. school is using COVID relief funds to target students on the verge of failure .

Higher education: College and university enrollment is nowhere near pandemic level, experts worry. ACT and SAT testing have rebounded modestly since the massive disruptions early in the coronavirus pandemic, and many colleges are also easing mask rules .

DMV news: Most of Prince George’s students are scoring below grade level on district tests. D.C. Public School’s new reading curriculum is designed to help improve literacy among the city’s youngest readers.

Four of the biggest problems facing education—and four trends that could make a difference

Eduardo velez bustillo, harry a. patrinos.

In 2022, we published, Lessons for the education sector from the COVID-19 pandemic , which was a follow up to, Four Education Trends that Countries Everywhere Should Know About , which summarized views of education experts around the world on how to handle the most pressing issues facing the education sector then. We focused on neuroscience, the role of the private sector, education technology, inequality, and pedagogy.

Unfortunately, we think the four biggest problems facing education today in developing countries are the same ones we have identified in the last decades .

1. The learning crisis was made worse by COVID-19 school closures

Low quality instruction is a major constraint and prior to COVID-19, the learning poverty rate in low- and middle-income countries was 57% (6 out of 10 children could not read and understand basic texts by age 10). More dramatic is the case of Sub-Saharan Africa with a rate even higher at 86%. Several analyses show that the impact of the pandemic on student learning was significant, leaving students in low- and middle-income countries way behind in mathematics, reading and other subjects. Some argue that learning poverty may be close to 70% after the pandemic , with a substantial long-term negative effect in future earnings. This generation could lose around $21 trillion in future salaries, with the vulnerable students affected the most.

2. Countries are not paying enough attention to early childhood care and education (ECCE)

At the pre-school level about two-thirds of countries do not have a proper legal framework to provide free and compulsory pre-primary education. According to UNESCO, only a minority of countries, mostly high-income, were making timely progress towards SDG4 benchmarks on early childhood indicators prior to the onset of COVID-19. And remember that ECCE is not only preparation for primary school. It can be the foundation for emotional wellbeing and learning throughout life; one of the best investments a country can make.

3. There is an inadequate supply of high-quality teachers

Low quality teaching is a huge problem and getting worse in many low- and middle-income countries. In Sub-Saharan Africa, for example, the percentage of trained teachers fell from 84% in 2000 to 69% in 2019 . In addition, in many countries teachers are formally trained and as such qualified, but do not have the minimum pedagogical training. Globally, teachers for science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM) subjects are the biggest shortfalls.

4. Decision-makers are not implementing evidence-based or pro-equity policies that guarantee solid foundations

It is difficult to understand the continued focus on non-evidence-based policies when there is so much that we know now about what works. Two factors contribute to this problem. One is the short tenure that top officials have when leading education systems. Examples of countries where ministers last less than one year on average are plentiful. The second and more worrisome deals with the fact that there is little attention given to empirical evidence when designing education policies.

To help improve on these four fronts, we see four supporting trends:

1. Neuroscience should be integrated into education policies

Policies considering neuroscience can help ensure that students get proper attention early to support brain development in the first 2-3 years of life. It can also help ensure that children learn to read at the proper age so that they will be able to acquire foundational skills to learn during the primary education cycle and from there on. Inputs like micronutrients, early child stimulation for gross and fine motor skills, speech and language and playing with other children before the age of three are cost-effective ways to get proper development. Early grade reading, using the pedagogical suggestion by the Early Grade Reading Assessment model, has improved learning outcomes in many low- and middle-income countries. We now have the tools to incorporate these advances into the teaching and learning system with AI , ChatGPT , MOOCs and online tutoring.

2. Reversing learning losses at home and at school

There is a real need to address the remaining and lingering losses due to school closures because of COVID-19. Most students living in households with incomes under the poverty line in the developing world, roughly the bottom 80% in low-income countries and the bottom 50% in middle-income countries, do not have the minimum conditions to learn at home . These students do not have access to the internet, and, often, their parents or guardians do not have the necessary schooling level or the time to help them in their learning process. Connectivity for poor households is a priority. But learning continuity also requires the presence of an adult as a facilitator—a parent, guardian, instructor, or community worker assisting the student during the learning process while schools are closed or e-learning is used.

To recover from the negative impact of the pandemic, the school system will need to develop at the student level: (i) active and reflective learning; (ii) analytical and applied skills; (iii) strong self-esteem; (iv) attitudes supportive of cooperation and solidarity; and (v) a good knowledge of the curriculum areas. At the teacher (instructor, facilitator, parent) level, the system should aim to develop a new disposition toward the role of teacher as a guide and facilitator. And finally, the system also needs to increase parental involvement in the education of their children and be active part in the solution of the children’s problems. The Escuela Nueva Learning Circles or the Pratham Teaching at the Right Level (TaRL) are models that can be used.

3. Use of evidence to improve teaching and learning

We now know more about what works at scale to address the learning crisis. To help countries improve teaching and learning and make teaching an attractive profession, based on available empirical world-wide evidence , we need to improve its status, compensation policies and career progression structures; ensure pre-service education includes a strong practicum component so teachers are well equipped to transition and perform effectively in the classroom; and provide high-quality in-service professional development to ensure they keep teaching in an effective way. We also have the tools to address learning issues cost-effectively. The returns to schooling are high and increasing post-pandemic. But we also have the cost-benefit tools to make good decisions, and these suggest that structured pedagogy, teaching according to learning levels (with and without technology use) are proven effective and cost-effective .

4. The role of the private sector

When properly regulated the private sector can be an effective education provider, and it can help address the specific needs of countries. Most of the pedagogical models that have received international recognition come from the private sector. For example, the recipients of the Yidan Prize on education development are from the non-state sector experiences (Escuela Nueva, BRAC, edX, Pratham, CAMFED and New Education Initiative). In the context of the Artificial Intelligence movement, most of the tools that will revolutionize teaching and learning come from the private sector (i.e., big data, machine learning, electronic pedagogies like OER-Open Educational Resources, MOOCs, etc.). Around the world education technology start-ups are developing AI tools that may have a good potential to help improve quality of education .

After decades asking the same questions on how to improve the education systems of countries, we, finally, are finding answers that are very promising. Governments need to be aware of this fact.

To receive weekly articles, sign-up here

Consultant, Education Sector, World Bank

Senior Adviser, Education

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Top issues for young voters? Stories from a swing state.

Why are we so divided? Zero-sum thinking is part of it.

It may be neither higher nor intelligence

Bridget Long, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, addresses the impact of the COVID-19 crisis in the field of education.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

Post-pandemic challenges for schools

Harvard Staff Writer

Ed School dean says flexibility, more hours key to avoid learning loss

With the closing of schools, the COVID-19 pandemic has revealed many of the injustices facing schoolchildren across the country, from inadequate internet access to housing instability to food insecurity. The Gazette interviewed Bridget Long, A.M. ’97, Ph.D. ’00, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education and Saris Professor of Education and Economics, regarding her views on the impact the public health crisis has had on schools, the lessons learned from the pandemic, and the challenges ahead.

Bridget Long

GAZETTE: The pandemic exposed many inequities that already existed in the education landscape. Which ones concern you the most?

LONG: Persistent inequities in education have always been a concern, but with the speed and magnitude of the changes brought on by the pandemic, it underscored several major problems. First of all, we often think about education as being solely an academic enterprise, but our schools really do so much more. Immediately, we saw children and families struggling with basic needs, such as access to food and health care, which our schools provide but all of a sudden were removed. We also shifted our focus, once we had to be in lockdown, to the differences in students’ home environments, whether it was lack of access to technology and the other commitments and demands on their time in terms of family situations, space, basic needs, and so forth. The focus had to shift from leveling the playing field within school or within college to instead what are the differences in inequities inside students’ homes and neighborhoods and the differences in the quality and rigor and supports available to students of different backgrounds. All of this was just exacerbated with the pandemic. There are concerns about learning loss and how that will vary across different income groups, communities, and neighborhoods. But there are also concerns about trauma and the mental health strain of the pandemic and how the strain of racial injustice and political turmoil has also been experienced — no doubt differently by different parts of population. And all of that has impacted students’ well-being and academic performance. The inequities we have long seen have become worse this year.

GAZETTE: Now that those inequities have been exposed, what can leaders in education do to navigate those issues? Are there any specific lessons learned?

LONG: Something that many educators already understood is that one size does not fit all. This is why education is so complex and why it has been so challenging to bring about improvements because there’s no silver bullet. The solution depends on the individual, the community, and the classroom.

At first, the public health crisis underscored that we needed to meet students where they are. This has been a long-held lesson among experienced education professionals, but it became even more important. In many respects, it butted up against some of our systems, which tried to come up with across-the-board approaches when instead what we needed was a bit of nimbleness depending on the context of the particular school or classroom and the individual needs of students.

Where you have seen some success and progress is where principals and teachers have been proactive and creative in how they can meet the needs of their students. What’s underneath all of this, regardless of whether we’re face-to-face or on technology, is the importance of people and personal connections. Education is a labor-intensive industry. Technology can help us in many respects to supplement or complement what we do, but the key has always been individual personal connection. Some teachers have been able to connect with their students, whether by phone or on Zoom, or schools, where they put concerted effort into doing outreach in the community to check on families to make sure they had basic needs. Some schools were able to understand what challenges their students were facing and were somewhat flexible and proactive to address those challenges, especially if they already had strong parental engagement. That’s where you have continued to see progress and growth.

“In many respects, this crisis forced the entire field to rethink our teaching in a way that I don’t know has happened before.”

GAZETTE: You spoke about concerns about learning loss. What can we do to avoid a lost year?

LONG: One of the difficulties is that the experience has differed tremendously. For some students, their parents have been able to supplement or their schools have been able to react. The hope is that they will not lose much learning time, while other students effectively haven’t been in school for almost a year; they have lost quite a bit of ground. As a teacher, you can imagine your students come back to school, and all of a sudden, students of the same chronological age are actually in very different places, depending on their individual family situation and what accommodations were able to be made. I think there’s a great deal we can do to try to address that. First of all, we have to have some understanding of what gains students have made as well as things they haven’t learned yet. That means taking a moment to see where a student is in their learning. The second thing is to make sure we’re capturing the lessons learned from this pandemic by identifying places where teachers and schools used a combination of technology, outreach, personal instruction, and tutors and mentors, and helped students make progress in their learning. We need to share those lessons more broadly so that other districts can see examples that have worked.

As we look ahead, I think it will take extending learning time to close the gaps. Schools will have to decide whether that is after school, weekends, or summer, and whether or not that’s going to involve the teachers themselves, or if it’s going to be using the best tools that are out there, such as videos and technology platforms that students and families use themselves. There has already been talk by some districts of extending the school year into summer or having summer-camp-type programs to give students additional time to work through some of the material.

The other important piece is partnerships. Schools oftentimes work with members of the community or nonprofit organizations, and that’s a really important layer in our system. After-school programs, enrichment programs, tutors, and mentors are essential, and we really want to continue with that expanded sense of capacity and partnership. It’s going to have an impact on all of us if we lose a generation, or if this generation goes backwards in terms of their learning. It certainly is in all of our best interests to try to contribute to the solution.

GAZETTE: Many parents gained renewed appreciation of the work teachers do. Do you think the pandemic would lead to a reappraisal of the profession?

LONG: Certainly, in the beginning, there was so much more appreciation for what teachers do. As parents needed to start doing homeschooling, there was a new understanding of just how difficult teaching is. Imagine having a classroom with different personalities, different strengths and assets, and also different weaknesses, and somehow being nimble enough to continue that class moving forward. As time has gone on, I worry a little bit about the level of contentiousness in some communities as schools haven’t reopened. There is the balancing act between caring for children’s learning and the fact that we have to make sure that the adults are safe and supported. You hear stories of teachers trying to teach from home while they are also homeschooling their own children. I would hope that coming out of this would be an appreciation of the amazing things teachers do in the classroom, as well as also some acknowledgement that these are people who are also living through a devastating pandemic with all the stress and strain that every individual is going through.

One other point is that given that we know that teachers do more than just academics, we need to make sure our teachers are trained to be able to provide social emotional support to students. As some of the students come back into the classroom, we need to acknowledge that they may be dealing with devastating losses, or the frustration of being kept inside, or the violence that is happening in their homes and neighborhoods. It’s very hard to learn if you’re first dealing with those kinds of issues. Our teachers already do so much, and we need to support them more and provide even more training to help them address that wide-ranging set of challenges their students may be facing even before they can get to the learning part.

“Something that many educators already understood is that one size does not fit all. This is why education is so complex and why it has been so challenging to bring about improvements because there’s no silver bullet.”

GAZETTE: Are there any silver linings in education brought on by the pandemic?