Risk Prediction Models for Lung Cancer: A Systematic Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Department of School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Department of School of Health and Related Research, University of Sheffield, Sheffield, United Kingdom.

- PMID: 26712102

- DOI: 10.1016/j.cllc.2015.11.007

Many lung cancer risk prediction models have been published but there has been no systematic review or comprehensive assessment of these models to assess how they could be used in screening. We performed a systematic review of lung cancer prediction models and identified 31 articles that related to 25 distinct models, of which 11 considered epidemiological factors only and did not require a clinical input. Another 11 articles focused on models that required a clinical assessment such as a blood test or scan, and 8 articles considered the 2-stage clonal expansion model. More of the epidemiological models had been externally validated than the more recent clinical assessment models. There was varying discrimination, the ability of a model to distinguish between cases and controls, with an area under the curve between 0.57 and 0.879 and calibration, the model's ability to assign an accurate probability to an individual. In our review we found that further validation studies need to be considered; especially for the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial 2012 Model Version (PLCOM2012) and Hoggart models, which recorded the best overall performance. Future studies will need to focus on prediction rules, such as optimal risk thresholds, for models for selective screening trials. Only 3 validation studies considered prediction rules when validating the models and overall the models were validated using varied tests in distinct populations, which made direct comparisons difficult. To improve this, multiple models need to be tested on the same data set with considerations for sensitivity, specificity, model accuracy, and positive predictive values at the optimal risk thresholds.

Keywords: Clinical utility; Prediction models; Prediction models' design; Prediction models' discrimination; Validation results.

Copyright © 2016 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Research Support, Non-U.S. Gov't

- Systematic Review

- Decision Support Techniques*

- Early Detection of Cancer / methods

- Lung Neoplasms / diagnosis*

- Lung Neoplasms / epidemiology

- Models, Statistical

- Predictive Value of Tests

- Risk Assessment

- Risk Factors

- Sensitivity and Specificity

Log in using your username and password

- Search More Search for this keyword Advanced search

- Latest content

- Current issue

- Instructions for Authors

- BMJ Journals More You are viewing from: Google Indexer

You are here

- Online First

- Chemotherapy decision-making in advanced lung cancer: a prospective qualitative study

- Article Text

- Article info

- Citation Tools

- Rapid Responses

- Article metrics

- Annmarie Nelson 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0002-9867-3806 Mirella Longo 1 ,

- Anthony Byrne 1 ,

- Stephanie Sivell 1 ,

- http://orcid.org/0000-0001-5425-2383 Simon Noble 1 ,

- Jason Lester 2 ,

- Lesley Radley 3 ,

- David Jones 3 ,

- Catherine Sampson 1 and

- Despina Anagnostou 1

- 1 Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Centre, School of Medicine , Cardiff University , Cardiff , South Glamorgan , UK

- 2 Velindre Cancer Centre , Cardiff , Cardiff , UK

- 3 Cardiff University , Cardiff , South Glamorgan , UK

- Correspondence to Professor Annmarie Nelson, Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Centre, School of Medicine, Cardiff University, Cardiff cf14 4ys, South Glamorgan, UK; nelsona9{at}Cardiff.ac.uk

Objective To study how treatment decisions are made alongside the lung cancer clinical pathway.

Methods A prospective, multicentre, multimethods, five-stage, qualitative study. Mediated discourse, thematic, framework and narrative analysis were used to analyse the transcripts.

Results 51 health professionals, 15 patients with advanced lung cancer, 15 family members and 18 expert stakeholders were recruited from three UK NHS trusts. Multidisciplinary team (MDT) members constructed treatment recommendations around patient performance status, pathology, clinical information and imaging. Information around patients’ social context, needs and preferences were limited. The provisional nature of MDTs treatment recommendations was not always linked to future discussions with the patient along the pathway, that is, patients’ interpretation of their prognosis, treatment discussions occurring prior to seeing the oncologist. This together with the rapid disease trajectory placed additional stress on the oncologist, who had to introduce a different treatment option from that recommended by the MDT or patient’s expectations. Palliative treatment was not referred to explicitly as such, due to its potential for confusion. Patients were unaware of the purpose of each consultation and did not fully understand the non-curative intent of treatment pathways. Patients’ priorities were framed around social and family needs, such as being able to attend a family event.

Conclusion Missed opportunities for information giving, affect both clinicians and patients; the pathway for patients with non-small cell lung cancer focuses on clinical management at the expense of patient-centred care. Treatment decisions are a complex process and patients draw conclusions from healthcare interactions prior to the oncology clinic, which prioritises aggressive treatment and influences decisions.

- communication

- supportive care

- clinical assessment

- quality of life

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ .

https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjspcare-2020-002395

Statistics from Altmetric.com

Request permissions.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Introduction

New developments in immunotherapy offer promising treatment for advanced lung cancer. 1 However, a considerable number of patients with non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) present with locally advanced or metastatic disease and are currently unsuitable for curative treatment with a median survival of 6–8 months. 2 The fear of destroying hope places a huge burden on the clinicians who may resort to the treatment imperative; 3 patients’ limited understanding of treatment with palliative intent 4 5 further hinders the patients’ opportunity to consider all available options and to make an informed decision. Treatment decisions become time bound, complex and require information and awareness for both patients and clinicians.

Chemotherapy with palliative intent is used for symptom control and to improve quality of life; however, systemic anticancer treatment (SACT) may have unintentionally detrimental effects. For patients in advanced stage, including NSCLC, SACT can increase early treatment-related mortality, 6–10 toxicities, emergency and inpatient admissions 11 and affect quality of life, even in patients with good performance status. 12 Around 10% of patients with lung cancer are dying within 30 days of SACT and this is arguably overly aggressive care. The urgency of administering treatments, in an attempt to mitigate deterioration, can also result in underpreparation of patients and families at the end of life 13 14 and patients become less likely to die in their preferred place of death. 15 Documentation of end of life discussions and discontinuation of treatment is rare; 16 17 however, early links with palliative care teams improve the timing of final chemotherapy administration and transition to hospice services. 18–20 Patients opting out of SACT 21 show greater acceptance of terminal status, focus on the present and on time with family.

The WHO places responsiveness and participation as key to achieving integrated people-centred health services and advocates care in respect of people’s preferences. 22 Clinical pathways aim to support decisions along the treatment pathway; however, in oncology, these seem to focus on when to start anticancer treatment—not when to stop. Studying the treatment decision-making process, alongside the patient clinical pathway, helps to understand the interaction of factors at different levels and how these influence the success or the failure of patient-centred care in the context of these very sensitive consultations. This study aimed to understand how palliative chemotherapy treatment decisions are determined and what intervention could support Patients with NSCLC and clinicians when considering AntiCancer Therapy (the PACT study). The paper adheres to Consolidated criteria for Reporting Qualitative research guidelines ( online supplementary 1 ; online supplementary table e1 ).

Supplemental material

The PACT study was a five-stage, prospective, qualitative multicentre, multimethods study. The original protocol 23 was adhered to with the exception of using narrative analysis in place of interpretative phenomenological analysis as clear narratives emerged in the data. A conceptual framework was built around study aim and objectives ( figure 1 ).

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Patients with non-small cell lung cancer and clinicians when considering AntiCancer Therapy (PACT) conceptual framework. MDT, multidisciplinary team.

Participants

A stakeholder approach was used to purposively sample study participants. For phases 1–4, clinicians and patients were recruited from three hospitals set within three University Health Boards in Wales. UK experts with an interest in lung cancer were invited to the expert consensus event. The data collected throughout phases 2–4 included the same patient/doctor dyad. Patient and public involvement (PPI) was incorporated throughout the study and in accordance with the national standards.

Approach and consent

Patients with a diagnosis of NSCLC and due to attend their first appointment with the oncologist were eligible to be part of the study. Multidisciplinary team (MDT) members were recruited and consented first. Clinicians identified eligible participants and provided them with an information sheet and a cover letter which included a reply slip where they would specify their contact details if they wished to be contacted about the study. Consent from clinicians, patients, companions and experts attending the consensus event was taken by the researchers (CS, DS, ML). Audio recording and fields notes were used throughout.

Data analysis

Inductive thematic analysis was used initially to aid understanding of the data before specific methodologies were overlaid. Principles of mediated discourse analysis were applied to MDT meetings to understand team dynamics and working practices, the role played by key MDT members and factors influencing allocation of patients to treatment pathways. Narrative analysis was used to study the consultations between the patient/companion and clinician and follow-up face-to-face interviews. Narrative analysis highlighted the priorities of the participants in single consultations; it also enabled the decision-making trajectory to be modelled through a generic consultation with priorities for each participant indicated at each phase. The OPTION (Observing PaTient InvOlvemeNt) tool 24 was used as a consultation process framework to assess how clinicians involved patients in consultations under key clinical domains ( online supplementary 2 ; online supplementary table e2 ); this was reflected in the interview guide ( online supplementary 4 ). Phase 5 drew together expert stakeholders and provided the platform where information from phases 1 to 4 could be shared, questioned and prioritised by all parties. Group discussions were held and covered seven areas of enquiry (eg, patients’ preparedness; online supplementary 4 , online supplementary table e3 ). The composition of groups ensured that while the focus was on the patient, the intervention would receive input from carers and health professionals at each stage of the clinical pathway. A deductive thematic analysis (coding tree focus group 3— online supplementary 5 , online supplementary tables e4-e10 ) of the group discussions was initially organised around responses to the areas of enquiry and then transformed into a series of statements of suggested practice attached to the clinical pathway. Data saturation was determined by the researchers. NVIVO (V.12) was used to organise the data.

Research team reflexivity

The research team comprised clinical oncology consultants, palliative care consultants, patient representatives and experienced postdoctoral researchers with expertise in healthcare research, decision-making, ethnography, discourse analysis and narrative analysis. This variety helped to balance knowledge and assumptions, personal experiences and biases towards aims of treatment, or the dynamic relationships of patients and healthcare professionals. Data collection was undertaken by experienced and trained researchers (DS, CS, ML) not associated with patients or clinical sites.

Between March 2015 and January 2017, a total of 99 participants were recruited into the study ( online supplementary 6 ; online supplementary table e11 ). Participants who declined to take part were not recorded.

PPI involvement

One public contributor (PC) contributed to the development of the research proposal. During the study, two PCs commented on the: information available to patients and their families; jargon used at MDT meetings; and patient recruitment strategies. They took part in the consensus day. They read a sample of anonymised transcripts of patient–clinician consultations and contributed to validate, interpret and contextualise the findings. The PCs continue to be involved in the dissemination of the study results and have agreed to join the follow-up study.

Lung cancer MDT meetings

Each MDT meeting followed local site routines; however, the primary purpose was to provide accurate diagnosis and recommend treatment pathways. Meetings usually included a chest physician, an oncologist, a radiologist, a pathologist, a lung clinical nurse specialist (CNS) and an MDT coordinator. Palliative care consultants were not always present. Patients were primarily represented through technology ( figure 2 ). Patient-focused clinical and social information was limited.

Presenting patient information at the multidisciplinary team meeting.

Radiology and pathology reports were the key references for making treatment recommendations, with the chest physician and the oncologist making key contributions to the decision-making discussions. Performance status was significant in moderating discussion of treatment options. However, treatment decisions were sometimes based on a historical performance status (quotation 1— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ).

The provisional nature of a treatment recommendation was not always clearly linked to future discussions with the patient at identified key points on the pathway, that is, considering what the chest physician would discuss and how the patient’s interpretation of their prognosis and any treatment discussions would be conveyed to the oncologist.

Oncology clinic

Four themes emerged from the analysis of the oncology consultation and follow-up interviews: process and priorities were key themes influencing the choice/availability of treatment options and decision-making in the oncology consultation; and the concept of palliative treatment intent and prognosis were key challenges to communication of options. The intersection between these four themes influenced the explicit discussion of options and terminal prognoses and gave insights into the uncertainty for patients around treatment options (quotation 2— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ).

Patients were generally unaware that the oncology consultation was a treatment decision-making event and carried expectations about their treatment plan originating earlier by prior events on the clinical pathway (for instance, discussion with the chest physician) (quotations 3 and 4— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ). This suggests a series of missed opportunities for ‘preparedness’ from both parties.

The oncology consultation evolved over several stages; at each stage, each stakeholder held specific priorities ( figure 3 ).

Example of narrative analysis applied to the oncology consultation.

Patients focused on relationships, placing their disease in the context of everyday life and were concerned with what would happen next. Treatment context was focused on external priorities, such as being able to attend a special family event, and existing relationships with health professionals, all of which influenced their perception and knowledge of a particular treatment option (quotation 5— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ). Key issues were challenges for successful communication of their priorities, expertise and constancy within health professional relationships, and the need for adequate support to live with the uncertainty of their disease trajectory.

Oncologists were concerned with establishing rapport, were aware of time pressures and followed their own established structure. Performance status description alone did not provide the necessary contextual information for the oncologist who often had to re-evaluate the patient at the time of consultation. Key issues were communicating other treatment options (quotation 6— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ), managing uncertainty; particularly where the proposed MDT treatment decision trajectory had changed or where expectations from the chest physician consultation were no longer possible (quotation 7— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ).

Companions acted as the patient advocate and their role was to confirm patients’ knowledge, needs and preference (quotation 8— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ) and provide information on the patient’s quality of life. Key issues were preparing the patient to be as well as possible for treatment, having a consistent point of contact with the health professional team, and being aware of potentially different coping styles between patients and carers.

CNS s advocated for the patient perspective and highlighted relationships, patient’s home context and priorities, where they were known to them (quotation 9— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ). Key issues were the need for ongoing contact, explain terminology and outline treatment practicalities again, and giving the patient opportunities to reflect on their decisions.

Situations where a patient did not wish to discuss prognosis explicitly presented challenges for the oncologist (quotation 10— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ). Similar challenges arose when there was no formal documentation of how prognosis had been discussed with, and understood by, the patient and carer. Communication skills were key to the confidence of the oncologist in navigating the consultation without directly discussing prognosis.

Palliative intent of treatment

The most common treatment option offered was palliative chemotherapy, where the word ‘palliative’ was unspoken and remained implicit in the description (quotation 11— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ). There was potential for broad interpretation around the possibility of chemotherapy extending life (quotation 12— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ), and patient misunderstanding of the purpose as being palliative. However, when palliative was used, this often led to confusion as patients were uncertain about what exactly the oncologist was referring to.

The distinction between palliative treatments perceived as ‘active’ was significant, which indicated the lack of a positive alternative supportive care option. This was reinforced by oncologists’ discussion of their reluctance to use palliative terminology to avoid distress, suggesting ambivalence or lack of understanding around how palliative chemotherapy is presented (quotation 13— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ).

Treatment decision around SACT

Patients opting for SACT without questioning the oncologist had often discussed the proposed treatment option with the chest physician or CNS and had placed their trust in those health professionals. A further deciding factor was where patients felt that their only option was SACT, compounded by the lack of clear definition of what constitutes an active palliative pathway as a viable option.

Opting out of a proposed treatment was challenging for patients; patients did not want ‘active treatment’, as described by oncologists, for quality of life reasons (quotation 14— online supplementary 7 , online supplementary table e12 ) but were compromised further when oncologists positioned palliative chemotherapy as an option that had to be overtly refused. Table 1 displays the treatment pathways and survival of our study participants.

- View inline

Patients’ planned and actual treatment pathway

Consensus day: defining the key components of the intervention

The findings from phases 1 to 4 set the framework underpinning the design of the intervention. These consistently highlight a lack of ‘preparedness’ along the clinical pathway ( figure 4 ).

Statements of suggested practice mapped to the clinical pathway. MDT, multidisciplinary team; NHS, National Health Service.

This mapping signifies a departure from a traditional clinical pathway, providing information on all treatment options early, and identifying patients’ priorities and preferences to inform MDT recommendations in advance of the oncology consultation. The data confirm that a future intervention should include a systematic collection and bidirectional flow of relevant information along the pathway, starting from primary care.

Tailored qualitative methods were used to understand how palliative chemotherapy treatment decisions are determined in advanced lung cancer. Data collection began with the MDT meetings where treatment discussions begin. MDT members constructed treatment recommendations mainly around patient performance status, pathology, clinical information and imaging. Patients’ needs were not fully addressed because information about their social needs and preferences was limited. 25

Measures of performance status did not fully capture patients’ overall function and in this context where risks and benefits are finely balanced, alternative indicators regarding patients’ ability to tolerate treatment, for example, frailty, cachexia should be considered. 26–28 Here, the palliative care ethos of keeping people as well as possible for as long as possible highlights the risks of tipping the balance—between preserving patients’ function, and ability to take part in everyday activities, to hastening decline from avoidable toxicities. With increasing evidence to support the benefits of specialist palliative care for patients with advanced cancer, 29 there is an argument against avoidable harm by SACT, and disenfranchisement of patients’ access to better care.

Prognosis was the link for the oncologist to discuss available treatment options, and was compromised either by situations where a patient expressed a clear desire not to refer explicitly to prognosis, or where there was lack of information sharing among clinicians about how prognosis had been interpreted by the patient. 30 Further, for patients with NSCLC, decision-making is a continuous process 17 rather than a single event. With a rapid disease trajectory, the health of the patient might change significantly before the oncology appointment. The oncologist may have to re-evaluate the patient and consider a different treatment option to that recommended at the MDT. 31 This proved particularly demanding for less experienced clinicians; training protocols have been developed but they did not always result in increased competency. 32 Clinicians’ attitude towards hope is also contributory to limited disclosure as Atul Gawande 33 describes it “Suppose I was wrong, I wondered, and she proved to be that miracle patient who survived metastatic lung cancer?” (p168). In addition to this, clinicians might be hesitant to crush patients’ expectations when discussing palliative cancer treatments. Communication styles 34 35 can affect patients’ experiences and treatment choices, new approaches to treatment decisions, such as the global Choosing Wisely initiative 36 encourage the use of prompt questions by clinicians and patients to weigh up the risks and benefits of treatment including the potential trigger question, ‘What if I do nothing’.

Issues relating to palliative terminology often arose; 4 however, patients’ understanding of ‘palliative’ can be improved 37 and, differentiating between palliative care and end-of-life care, to what is effectively supportive oncology, could also improve referral. 38 From a population perspective, societal challenges have been identified, including a public acceptance of death as part of being human, and the education of patients and families about treatment goals for cancer. 39 40

The study adopted a coproductive approach, which ensured that all relevant stakeholders contributed to inform the intervention. The robust multiqualitative design allowed the study of the patient journey from different perspectives and levels. Patients represented geographical, and socioeconomic diversity, and different communities of professional practice. This study did not aim to contest or verify the appropriateness of the treatment decisions made. However, from the analysis of the treatment decision-making process, it emerged that there is a series of missed opportunities along the clinical pathway and these impacted on both clinicians and patients. Embedding patients’ values and preferences into the treatment decision-making process may facilitate difficult consultations, reduce aggressive end-of-life treatments, and reflect more closely patients’ goals and motives in their everyday lives.

Conclusions

Current cancer clinical pathways are not designed to include the circumstances, priorities and preferences of patients taking part in these highly sensitive consultations. The optimal management of advanced patients with NSCLC necessitates going beyond the treatment of symptoms by reflecting what matters to the patients within their personal context.

This patient population is characterised by a complex intersection of terminal disease with a short prognosis and declining functioning. Decisions around treatment towards end of life have a particular acuity, the limited patient understanding of the aims of treatment and the challenges faced by the clinicians who might resort to the treatment imperative may result in a clinical pathway heavily weighted towards SACT.

In the palliative context, the concept of hope realigns more realistically from hope of a cure to hope of comfort and quality of life. This study promotes opportunities for engagement with the patient (and family) and clinicians at different levels of the pathway to identify goals of care echoing the patient’s view of a life worth living.

Although these findings reflect the narratives of the study participants and the researchers’ interpretation of these, they also reflect elements easily applicable to many patients diagnosed with advanced cancer.

- Hellmann MD ,

- Rizvi NA , et al

- Connell CM ,

- De Vries RG , et al

- McIlfatrick S ,

- McCorry NK , et al

- Catalano PJ ,

- Cronin A , et al

- O’Hara C , et al

- O'Brien MR ,

- Whitehead B ,

- Murphy PN , et al

- Hamilton K , et al

- Wallington M ,

- Bomb M , et al

- Neville BA ,

- Landrum MB , et al

- Prigerson HG ,

- Shah MA , et al

- Burgers JA ,

- Murray SA ,

- Kendall M ,

- Mitchell G , et al

- Higginson IJ ,

- Sen-Gupta GJ

- Helde-Frankling M ,

- Runesdotter S , et al

- Traeger L ,

- Rapoport C ,

- Wright E , et al

- Jackson VA , et al

- Wright AA ,

- Ray A , et al

- Walling A ,

- Dy S , et al

- Anagnostou D ,

- Noble S , et al

- Hutchings H ,

- Edwards A , et al

- Arora S , et al

- Rockwood K ,

- MacKnight C , et al

- Gambassi G ,

- van Kan GA ,

- Abellan van Kan G , et al

- Moffatt H ,

- Moorhouse P ,

- Mallery L , et al

- Ziegler LE ,

- Craigs CL ,

- West RM , et al

- Laryionava K ,

- Reiter-Theil S , et al

- Trinidad SB ,

- Hopley EK , et al

- Johnson LA ,

- Morse R , et al

- Henselmans I ,

- Van Laarhoven HW ,

- Van der Vloodt J , et al

- Levinson W ,

- Kallewaard M ,

- Bhatia RS , et al

- Carpenter BD

- El-Jawahri A , et al

- Harrington SE ,

Twitter @annmarienelson0, @MirellaLongo18

Contributors AN conceived and designed the study; drafted the manuscript. AN, SN, AB, SS and JL secured funding for the study. DA, CS and ML led the collection and analysis of the data. All authors made substantial contribution to the analysis and interpretation of the data. The public contributors (LR and DJ) supported the study throughout and carried out the validation of the findings. ML and CS contributed to the drafting of the manuscript. All authors reviewed and commented on the drafts of this manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript. CS and DA are joint last authors.

Funding This study was funded by The Velindre Stepping Stones Appeal within Velindre NHS Trust Charitable Funds; Grant No 2013/009. Sponsored by Cardiff University; and coordinated by the Marie Curie core-funded Marie Curie Palliative Care Research Centre at Cardiff University. AN, AB, ML, SS and SN’s posts are funded by Marie Curie Cancer Care core grant funding (grant reference MCCC-FCO-17-C).

Competing interests None declared.

Patient consent for publication Not required.

Ethics approval Ethical approval was granted (REC 14/WA/1103).

Provenance and peer review Not commissioned; internally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement Data are available upon reasonable request. Anonymised narratives from the transcripts will be available upon request.

Read the full text or download the PDF:

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 14 January 2022

Deep learning-based algorithm for lung cancer detection on chest radiographs using the segmentation method

- Akitoshi Shimazaki 1 ,

- Daiju Ueda 1 , 2 ,

- Antoine Choppin 3 ,

- Akira Yamamoto 1 ,

- Takashi Honjo 1 ,

- Yuki Shimahara 3 &

- Yukio Miki 1

Scientific Reports volume 12 , Article number: 727 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

20k Accesses

45 Citations

7 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Lung cancer

- Radiography

We developed and validated a deep learning (DL)-based model using the segmentation method and assessed its ability to detect lung cancer on chest radiographs. Chest radiographs for use as a training dataset and a test dataset were collected separately from January 2006 to June 2018 at our hospital. The training dataset was used to train and validate the DL-based model with five-fold cross-validation. The model sensitivity and mean false positive indications per image (mFPI) were assessed with the independent test dataset. The training dataset included 629 radiographs with 652 nodules/masses and the test dataset included 151 radiographs with 159 nodules/masses. The DL-based model had a sensitivity of 0.73 with 0.13 mFPI in the test dataset. Sensitivity was lower in lung cancers that overlapped with blind spots such as pulmonary apices, pulmonary hila, chest wall, heart, and sub-diaphragmatic space (0.50–0.64) compared with those in non-overlapped locations (0.87). The dice coefficient for the 159 malignant lesions was on average 0.52. The DL-based model was able to detect lung cancers on chest radiographs, with low mFPI.

Similar content being viewed by others

Generative models improve fairness of medical classifiers under distribution shifts

Ira Ktena, Olivia Wiles, … Sven Gowal

Segment anything in medical images

Jun Ma, Yuting He, … Bo Wang

Towards a general-purpose foundation model for computational pathology

Richard J. Chen, Tong Ding, … Faisal Mahmood

Introduction

Lung cancer is the primary cause of cancer death worldwide, with 2.09 million new cases and 1.76 million people dying from lung cancer in 2018 1 . Four case-controlled studies from Japan reported in the early 2000s that the combined use of chest radiographs and sputum cytology in screening was effective for reducing lung cancer mortality 2 . In contrast, two randomized controlled trials conducted from 1980 to 1990 concluded that screening with chest radiographs was not effective in reducing mortality in lung cancer 3 , 4 . Although the efficacy of chest radiographs in lung cancer screening remains controversial, chest radiographs are more cost-effective, easier to access, and deliver lower radiation dose compared with low-dose computed tomography (CT). A further disadvantage of chest CT is excessive false positive (FP) results. It has been reported that 96% of nodules detected by low-dose CT screening are FPs, which commonly leads to unnecessary follow-up and invasive examinations 5 . Chest radiography is inferior to chest CT in terms of sensitivity but superior in terms of specificity. Taking these characteristics into consideration, the development of a computer-aided diagnosis (CAD) model for chest radiograph would have value by improving sensitivity while maintaining low FP results.

The recent application of convolutional neural networks (CNN), a field of deep learning (DL) 6 , 7 , has led to dramatic, state-of-the-art improvements in radiology 8 . DL-based models have also shown promise for nodule/mass detection on chest radiographs 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , which have reported sensitivities in the range of 0.51–0.84 and mean number of FP indications per image (mFPI) of 0.02–0.34. In addition, radiologist performance for detecting nodules was better with these CAD models than without them 9 . In clinical practice, it is often challenging for radiologists to detect nodules and to differentiate between benign and malignant nodules. Normal anatomical structures often appear as if they are nodules, which is why radiologists must pay careful attention to the shape and marginal properties of nodules. As these problems are caused by the conditions rather than the ability of the radiologist, even skillful radiologists can misdiagnose 14 , 15 .

There are two main methods for detecting lesions using DL: detection and segmentation. The detection method is a region-level classification, whereas the segmentation method is a pixel-level classification. The segmentation method can provide more detailed information than the detection method. In clinical practice, classifying the size of a lesion at the pixel-level increases the likelihood of making a correct diagnosis. Pixel-level classification also makes it easier to follow up on changes in lesion size and shape, since the shape can be used as a reference during detection. It also makes it possible to consider not only the long and short diameters but also the area of the lesion when determining the effect of treatment 16 . However, to our knowledge, there are no studies using the segmentation method to detect pathologically proven lung cancer on chest radiographs.

The purpose of this study was to train and validate a DL-based model capable of detecting lung cancer on chest radiographs using the segmentation method, and to evaluate the characteristics of this DL-based model to improve sensitivity while maintaining low FP results.

The following points summarize the contributions of this article:

This study developed a deep learning-based model for detection and segmentation of lung cancer on chest radiographs.

Our dataset is high quality because all the nodules/masses were pathologically proven lung cancers, and these lesions were pixel-level annotated by two radiologists.

The segmentation method was more informative than the classification or detection methods, which is useful not only for the detection of lung cancer but also for follow-up and treatment efficacy.

Materials and methods

Study design.

We retrospectively collected consecutive chest radiographs from patients who had been pathologically diagnosed with lung cancer at our hospital. Radiologists annotated the lung cancer lesions on these chest radiographs. A DL-based model for detecting lung cancer on radiographs was trained and validated with the annotated radiographs. The model was then tested with an independent dataset for detecting lung cancers. The protocol for this study was comprehensively reviewed and approved by the Ethical Committee of Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine (No. 4349). Because the radiographs had been acquired during daily clinical practice and informed consent for their use in research had been obtained from patients, the Ethical Committee of Osaka City University Graduate School of Medicine waived the need for further informed consent. All methods were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations.

Eligibility and ground truth labelling

Two datasets were used to train and test the DL-based model, a training dataset and a test dataset. We retrospectively collected consecutive chest radiographs from patients pathologically diagnosed with lung cancer at our hospital. The training dataset was comprised of chest radiographs obtained between January 2006 and June 2017, and the test dataset contained those obtained between July 2017 and June 2018. The inclusion criteria were as follows: (a) pathologically proven lung cancer in a surgical specimen; (b) age > 40 years at the time of the preoperative chest radiograph; (c) chest CT performed within 1 month of the preoperative chest radiograph. If the patient had multiple chest radiographs that matched the above criteria, the latest radiograph was selected. Most of these chest radiographs were taken as per routine before hospitalization and were not intended to detect lung cancer. Chest radiographs on which radiologists could not identify the lesion, even with reference to CT, were excluded from analysis. For eligible radiographs, the lesions were annotated by two general radiologists (A.S. and D.U.), with 6 and 7 years of experience in chest radiography, using ITK-SNAP version 3.6.0 ( http://www.itksnap.org/ ) . These annotations were defined as ground truths. The radiologists had access to the chest CT and surgical reports and evaluated the lesion characteristics including size, location, and edge. If > 50% of the edge of the nodule was traceable, the nodule was considered to have a “traceable edge”; if not, it was termed an “untraceable edge”.

Model development

We adopted the CNN architecture using segmentation method. The segmentation method outputs more information than the detection method (which present a bounding box) or the classification method (which determine the malignancy from a single image). Maximal diameter of the tumor is particularly important in clinical practice. Since the largest diameter of the tumor often coincides with an oblique direction, not the horizontal nor the vertical direction, it is difficult to measure with detection methods which present a bounding box. Our CNN architecture was based on the encoder-decoder architecture to output segmentation 17 . The encoder-decoder architecture has a bottleneck structure, which reduces the resolution of the feature map and improves the model robustness to noise and overfitting 18 .

In addition, one characteristic of this DL-based model is that it used both a normal chest radiograph and a black-and-white inversion of a chest radiograph. This is an augmentation that makes use of the experience of radiologists 19 . It is known that black-and-white inversion makes it easier to confirm the presence of lung lesions overlapping blind spots. We considered that this augmentation could be effective for this model as well, so we applied a CNN architecture to each of the normal and inverted images and then an ensemble model using these two architectures 20 . Supplementary Fig. S1 online shows detailed information of the model.

Using chest radiographs from the training dataset, the model was trained and validated from scratch, utilizing five-fold cross-validation. The model when the value of the loss function was the smallest within 100 epochs using Adam (learning rate = 0.001, beta_1 = 0.9, beta_2 = 0.999, epsilon = 0.00000001, decay = 0.0) was adopted as the best-performing.

Model assessment

A detection performance test was performed on a per-lesion basis using the test dataset to evaluate whether the model could identify malignant lesions on radiographs. The model calculated the probability of malignancy in a lesion detected on chest radiographs as an integer between 0 and 255. If the center of output generated by the model was within the ground truth, it was considered true positive (TP). All other outputs were FPs. When two or more TPs were proposed by the model for one ground truth, they were considered as one TP. If there was no output from the model for one ground truth, it was one FN. Two radiologists (A.S. and D.U.) retrospectively referred to the radiograph and CT to evaluate what structures were detected by the FP output. The dice coefficient was also used to evaluate segmentation performance.

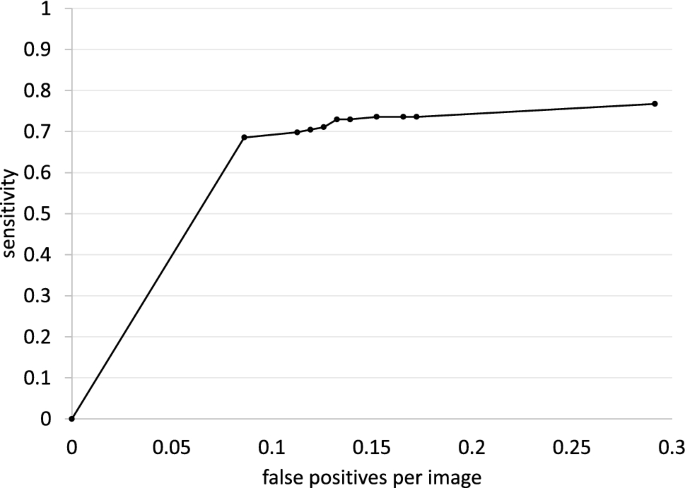

Statistical analysis

In the detection performance test, metrics were evaluated on a per-lesion basis. We used the free-response receiver-operating characteristic (FROC) curve to evaluate whether the bounding boxes proposed by the model accurately identified malignant cancers in radiographs 21 . The vertical axis of the FROC curve is sensitivity and the horizontal axis is mFPI. Sensitivity is the number of TPs that the model was able to identify divided by the number of ground truths. The mFPI is the number of FPs that the model mistakenly presented divided by the number of radiographs in the dataset. Thus, the FROC curve shows sensitivity as a function of the number of FPs shown on the image.

One of the authors (D.U.) performed all analyses, using R version 3.6.0 ( https://www.r-project.org/ ). The FROC curves were plotted by R software. All statistical inferences were performed with two-sided 5% significance level.

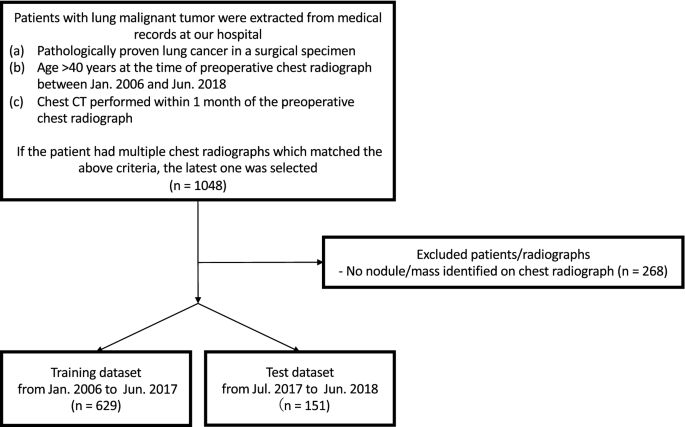

Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the eligibility criteria for the chest radiographs. For the training dataset, 629 radiographs with 652 nodules/masses were collected from 629 patients (age range 40–91 years, mean age 70 ± 9.0 years, 221 women). For the test dataset, 151 radiographs with 159 nodules/masses were collected from 151 patients (age range 43–84 years, mean age 70 ± 9.0 years, 57 women) (Table 1 ).

Flowchart of dataset selection.

The DL-based model had sensitivity of 0.73 with 0.13 mFPI in the test dataset (Table 2 ). The FROC curve is shown in Fig. 2 . The highest sensitivity the model attained was 1.00 for cancers with a diameter of 31–50 mm, and the second highest sensitivity was 0.85 for those with a diameter > 50 mm. For lung cancers that overlapped with blind spots such as the pulmonary apices, pulmonary hila, chest wall, heart, or sub-diaphragmatic space, sensitivity was 0.52, 0.64, 0.52, 0.56, and 0.50, respectively. The sensitivity of lesions with traceable edges on radiographs was 0.87, and that for untraceable edges was 0.21. Detailed results are shown in Table 2 .

The dice coefficient for all 159 lesions was on average 0.52 ± 0.37 (standard deviation, SD). For 116 lesions detected by the model, the dice coefficient was on average 0.71 ± 0.24 (SD). The dice coefficient for all 71 lesions overlapping blind spots was 0.34 ± 0.38 (SD). For 39 lesions detected by the model that overlapped with blind spots, the dice coefficient was 0.62 ± 0.29 (SD).

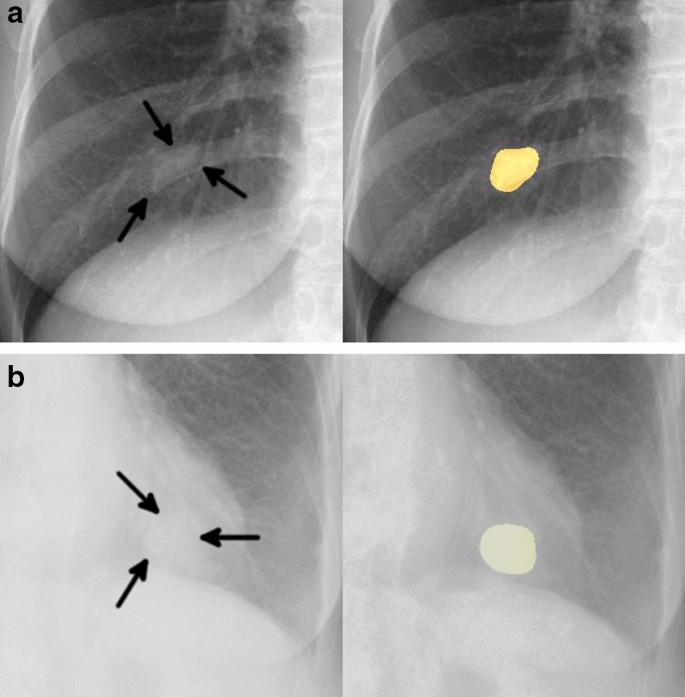

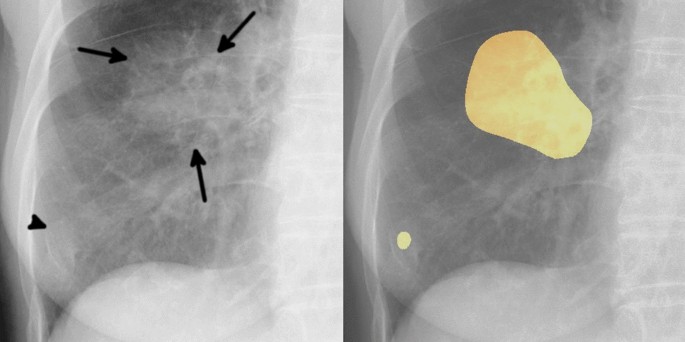

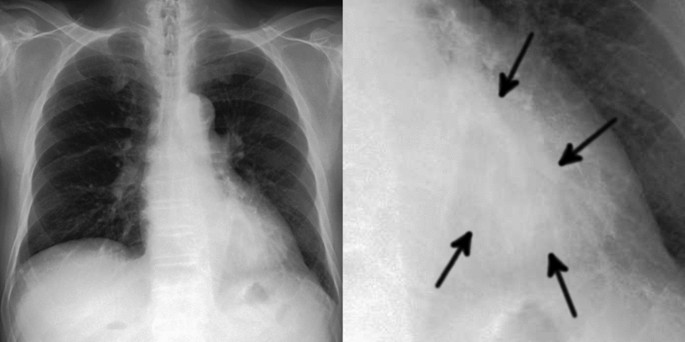

Of the 20 FPs, 19 could be identified as some kind of structure on the chest radiograph by radiologists (Table 3 ). In these 20 FPs, 13 overlapped with blind spots. There were 43 FNs, ranging in size from 9 to 72 mm (mean 21 ± 15 mm), 32 of which overlapped with blind spots (Table 4 ). There were four FNs > 50 mm, all of which overlapped with blind spots. Figure 3 shows representative cases of our model. Figure 4 shows overlapping of a FP output with normal anatomical structures and Fig. 5 shows a FN lung cancer that overlapped with a blind spot. Supplementary Fig. S2 online shows visualized images of the first and last layers. An ablation study to use black-and-white inversion images is shown in Supplementary Data online.

Free-response receiver-operating characteristic curve for the test dataset.

Two representative true positive cases. The images on the left are original images, and those on the right are images output by our model. ( a ) A 48-year-old woman with a nodule in the right lower lobe that was diagnosed as adenocarcinoma. The nodule was confused with rib and vessels (arrows). The model detected the nodule in the right middle lung field. ( b ) A 74-year-old woman with a nodule in the left lower lobe that was diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma. The nodule overlapped with the heart (arrows). The lesion was identifiable by the model because its edges were traceable.

Example of one false positive case. The image on the left is an original image, and the image on the right is an image output by our model. An 81-year-old woman with a mass in the right lower lobe that was diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma. The mass in the right middle lung field (arrows) was carcinoma. Our model detected this lesion, and also detected a slightly calcified nodule in the right lower lung field (arrowhead). This nodule was an old fracture of the right tenth rib, but was misidentified as a malignant lesion because its shape was obscured by overlap with the right eighth rib and breast.

Example of one false negative case. The image on the left is a gross image, and the image on the right is an enlarged image of the lesion. A 68-year-old man with a mass in the left lower lobe that was diagnosed as adenocarcinoma. This lesion overlapped with the heart and is only faintly visible (arrows). Our model failed to detect the mass.

In this study, we developed a model for detecting lung cancer on chest radiographs and evaluated its performance. Adding pixel-level classification of lesions in the proposed DL-based model resulted in sensitivity of 0.73 with 0.13 mFPI in the test dataset.

To our knowledge, ours is the first study to use the segmentation method to detect pathologically proven lung cancer on chest radiographs. We found several studies that used classification or detection methods to detect lung cancer on chest radiographs, but not the segmentation method. Since the segmentation method has more information about the detected lesions than the classification or detection methods, it has advantages not only in the detection of lung cancer but also in follow-up and treatment efficacy. We achieved performance as high as that in similar previous studies 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 using DL-based lung nodule detection models, with fewer training data. It is particularly noteworthy that the present method achieved low mFPI. In previous studies, sensitivity and mFPI were 0.51–0.84 and 0.02–0.34, respectively, and used 3,500–13,326 radiographs with nodules or masses as the training data, compared with the 629 radiographs used in the present study. Although comparisons to these studies are difficult because the test datasets were different, our accuracy was similar to that of the detection models employed in most of the previous studies. We performed pixel-level classification of the lesions based on the segmentation method and included for analysis only lesions that were pathologically proven to be malignant, based on examination of surgically resected specimens. All previous studies 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 have included potentially benign lesions, clinically malignant lesions, or pathologically malignant lesions by biopsy in their training data. Therefore, our model may be able to analyze the features of the malignant lesions in more detail. In regard with the CNN, we created this model based on Inception-ResNet-v2 17 , which combines the Inception structure and the Residual connection. In the Inception-ResNet block, convolutional filters of multiple sizes are combined with residual connections. The use of residual connections not only avoids the degradation problem caused by deep structures but also reduces the training time. In theory, the combination of these features further improves the recognition accuracy and learning efficiency 17 . By using this model with combining normal and black-white-inversion images, our results achieved comparable or better performance with fewer training data than previous studies. In regard with the robustness of the model, we consider this model to be relatively robust against imaging conditions or body shape because we consecutively collected the dataset and did not set any exclusion criteria based on imaging conditions or body shape.

The dice coefficient for 159 malignant lesions was on average 0.52. On the other hand, for the 116 lesions detected by the model, the dice coefficient was on average 0.71. These values provide a benchmark for the segmentation performance of lung cancer on chest radiograph. The 71 lesions which overlapped with blind spots tended to have a low dice coefficient with an average of 0.34, but for 39 lesions detected by the model that overlapped with blind spots, the average dice coefficient was 0.62. This means that lesions overlapping blind spots were not only difficult to detect, but also had low accuracy in segmentation. On the other hand, the segmentation accuracy was relatively high for lesions that were detected by the model even if they overlapped with the blind spots.

Two interesting tendencies were found after retrospectively examining the characteristics of FP outputs. First, 95% (19/20) FPs could be visually recognized on chest radiographs as nodule/mass-like structures. The model identified some nodule-like structures (FPs), which overlapped with vascular shadows and ribs. This is also the case for radiologists in daily practice. Second, nodules with calcification overlapped with normal anatomical structures tended to be misdiagnosed by the model (FPs). Five FPs were non-malignant calcified lung nodules on CT and also overlapped with the heart, clavicle or ribs. As the model was trained only on malignant nodules without calcification in the training dataset, calcified nodules should not be identified in theory. Most calcified nodules are actually not identified by the model, however, this was not the case for calcified nodules that overlapped with normal anatomical structures. In other word, there is a possibility that the model could misidentify the lesion as a malignant if the features of calcification that should signal a benign lesion are masked by normal anatomical structures.

When we investigated FNs, we found that nodules in blind spots and metastatic nodules tended to be FNs. With regard to blind spots, our model showed a decrease in sensitivity for lesions that overlapped with normal anatomical structures. It was difficult for the model to identify lung cancers that overlapped with blind spots even when the tumor size was large (Fig. 5 ). In all FNs larger than 50 mm, there was wide overlap with normal anatomical structures, for the possible reason that it becomes difficult for the model to detect subtle density differences in lesions that overlapped with large structures such as the heart. With regard to metastatic nodules, 33% (14/43) metastatic lung cancers were FNs. These metastatic nodules ranged in size from 10 to 20 mm (mean 14 ± 3.8 mm) and were difficult to visually identify on radiographs, even with reference to CT. In fact, the radiologists had overlooked most of the small metastatic nodules at first and could only identify them retrospectively, with knowledge of the type of lung cancer and their locations.

There are some limitations of this study. The model was developed using a dataset collected from a single hospital. Although our model achieved high sensitivity with low FPs, the number of FPs may be higher in a screening cohort and the impact of this should be considered. Furthermore, an observer’s performance study is needed to evaluate the clinical utility of the model. In this study, we included only chest radiographs containing malignant nodules/masses. The fact that we used only pathologically proven lung cancers and pixel-level annotations by two radiologists in our dataset is a strength of our study, on the other hand, it may reduce the detection rate of benign nodules/masses. This is often not a problem in clinical practice. Technically, all areas other than the malignant nodules/masses could be trained as normal areas. However, normal images should be mixed in and tested to evaluate the model for detailed examination in clinical practice.

In conclusion, a DL-based model developed using the segmentation method showed high performance in the detection of lung cancer on chest radiographs. Compared with CT, chest radiographs have advantages in terms of accessibility, cost effectiveness, and low radiation dose. However, the known effectiveness of the model for lung cancer detection is limited. We believe that a CAD model with higher performance can support clinical detection and interpretation of malignant lesions on chest radiographs and offers additive value in lung cancer detection.

Bray, F. et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 68 , 394–424. https://doi.org/10.3322/caac.21492 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Sagawa, M. et al. The efficacy of lung cancer screening conducted in 1990s: Four case–control studies in Japan. Lung Cancer 41 , 29–36. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0169-5002(03)00197-1 (2003).

Fontana, R. S. et al. Lung cancer screening: The Mayo program. J. Occup. Med. 28 , 746–750. https://doi.org/10.1097/00043764-198608000-00038 (1986).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kubik, A. et al. Lack of benefit from semi-annual screening for cancer of the lung: Follow-up report of a randomized controlled trial on a population of high-risk males in Czechoslovakia. Int. J. Cancer 45 , 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijc.2910450107 (1990).

Raghu, V. K. et al. Feasibility of lung cancer prediction from low-dose CT scan and smoking factors using causal models. Thorax 74 , 643–649. https://doi.org/10.1136/thoraxjnl-2018-212638 (2019).

Hinton, G. Deep learning—a technology with the potential to transform health care. JAMA 320 , 1101–1102. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.11100 (2018).

LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y. & Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 521 , 436–444. https://doi.org/10.1038/nature14539 (2015).

Article ADS CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Ueda, D., Shimazaki, A. & Miki, Y. Technical and clinical overview of deep learning in radiology. Jpn. J. Radiol. 37 , 15–33. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11604-018-0795-3 (2019).

Nam, J. G. et al. Development and validation of deep learning–based automatic detection algorithm for malignant pulmonary nodules on chest radiographs. Radiology 290 , 218–228. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2018180237 (2019).

Park, S. et al. Deep learning-based detection system for multiclass lesions on chest radiographs: Comparison with observer readings. Eur. Radiol. 30 , 1359–1368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00330-019-06532-x (2020).

Yoo, H., Kim, K. H., Singh, R., Digumarthy, S. R. & Kalra, M. K. Validation of a deep learning algorithm for the detection of malignant pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs. JAMA Netw. Open 3 , e2017135. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.17135 (2020).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sim, Y. et al. Deep convolutional neural network–based software improves radiologist detection of malignant lung nodules on chest radiographs. Radiology 294 , 199–209. https://doi.org/10.1148/radiol.2019182465 (2020).

Hwang, E. J. et al. Development and validation of a deep learning-based automated detection algorithm for major thoracic diseases on chest radiographs. JAMA Netw. Open 2 , e191095. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.1095 (2019).

Manser, R. et al. Screening for lung cancer. Cochrane Database Syst Rev CD001991. https://doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD001991.pub3 (2013).

Berlin, L. Radiologic errors, past, present and future. Diagnosis (Berl) 1 , 79–84. https://doi.org/10.1515/dx-2013-0012 (2014).

Article Google Scholar

From the RECIST committee. Schwartz, L.H. et al. RECIST 1.1-Update and clarification. Eur. J. Cancer. 62 , 132–137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejca.2016.03.081 (2016).

Szegedy, C., Ioffe, S., Vanhoucke, V. & Alemi, A. A. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning . In Proceedings of the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence , 4278–4284 (AAAI Press, San Francisco, California, USA, 2017).

Matějka P. et al. Neural Network Bottleneck Features for Language Identification. In Proceedings of Odyssey 2014. vol. 2014. International Speech Communication Association , 299–304 (2014).

Sheline, M. E. et al. The diagnosis of pulmonary nodules: Comparison between standard and inverse digitized images and conventional chest radiographs. Am. J. Roentgenol. 152 (2), 261–263. https://doi.org/10.2214/ajr.152.2.261 (1989).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Wang, G., Hao, J., Ma, J. & Jiang, H. A comparative assessment of ensemble learning for credit scoring. Expert. Syst. Appl. 38 (1), 223–230 (2011).

Bunch, P., Hamilton, J., Sanderson, G. & Simmons, A. A free response approach to the measurement and characterization of radiographic observer performance. Proc. SPIE 127 , 124–135. https://doi.org/10.1117/12.955926 (1977).

Article ADS Google Scholar

Download references

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to LPIXEL Inc. for joining this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology, Graduate School of Medicine, Osaka City University, Osaka, Japan

Akitoshi Shimazaki, Daiju Ueda, Akira Yamamoto, Takashi Honjo & Yukio Miki

Smart Life Science Lab, Center for Health Science Innovation, Osaka City University, Osaka, Japan

LPIXEL Inc, Tokyo, Japan

Antoine Choppin & Yuki Shimahara

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Material preparation, data collection and analysis were performed by A.S., D.U., A.Y. and T.H. Model development was performed by A.C. and Y.S. The first draft of the manuscript was written by A.S. and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Daiju Ueda .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

Akitoshi Shimazaki has no relevant relationships to disclose. Daiju Ueda has no relevant relationships to disclose. Antoine Choppin is an employee of LPIXEL Inc. Akira Yamamoto has no relevant relationships to disclose. Takashi Honjo has no relevant relationships to disclose. Yuki Shimahara is the CEO of LPIXEL Inc. Yukio Miki has no relevant relationships to disclose.

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

Supplementary information., rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Shimazaki, A., Ueda, D., Choppin, A. et al. Deep learning-based algorithm for lung cancer detection on chest radiographs using the segmentation method. Sci Rep 12 , 727 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04667-w

Download citation

Received : 04 August 2021

Accepted : 29 December 2021

Published : 14 January 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-04667-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Deep volcanic residual u-net for nodal metastasis (nmet) identification from lung cancer.

- M. Ramkumar

- K. Kalirajan

Biomedical Engineering Letters (2024)

Fairness of artificial intelligence in healthcare: review and recommendations

- Taichi Kakinuma

- Shinji Naganawa

Japanese Journal of Radiology (2024)

Lung tumor analysis using a thrice novelty block classification approach

- S. L. Soniya

- T. Ajith Bosco Raj

Signal, Image and Video Processing (2023)

Radon transform-based improved single seeded region growing segmentation for lung cancer detection using AMPWSVM classification approach

- K. Vijila Rani

- M. Eugine Prince

An efficient transfer learning approach for prediction and classification of SARS – COVID -19

- Krishna Kumar Joshi

- Kamlesh Gupta

- Jitendra Agrawal

Multimedia Tools and Applications (2023)

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing: Cancer newsletter — what matters in cancer research, free to your inbox weekly.

EDITORIAL article

Editorial: lung adenocarcinoma: from genomics to immunotherapy.

- 1 Department of Central Laboratory, Cancer Hospital of Dalian University of Technology, Liaoning Cancer Hospital and Institute, Shenyang, China

- 2 Cancer Genomics and Systems Biology Lab, Department of Medical Biotechnologies, University of Siena, Siena, Italy

- 3 Department of Medical Biotechnologies, Med Biotech Hub and Competence Centre, University of Siena, Siena, Italy

Editorial on the Research Topic Lung adenocarcinoma: from genomics to immunotherapy

Introduction

Lung cancer is the second most common type of cancer and is the leading cause of cancer death globally. In 2018, almost 2.1 million new cases were diagnosed, accounting for ∼12% of the cancer burden worldwide ( Sung et al., 2021 ). The malignant stage of lung cancer is known as lung adenocarcinoma, which is the most common and is diagnosed in both smokers and non-smokers.

There are two main types of lung cancer, the non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) and the small cell lung cancer (SCLC). Genomic studies have indicated that more than 80% of lung malignancies are classified as NSCLC, of which adenocarcinoma is the predominant subtype. In metastatic patients, although significant progress has been made for tumors harboring druggable mutations such as EGFR, the majority of those is lacking of such mutations and the prognosis remains poor. Platinum doublet chemotherapy has been the mainstay first-line treatment for patients who are diagnosed with metastatic lung adenocarcinoma without a targetable mutation ( Bodor et al., 2018 ).

In recent years, immunotherapy has emerged as a treatment option that has shown a strong response in a subset of patients. The immune agents block crucial checkpoints and regulate the immune response, but the tumor cells evade the patient’s immune system. By blocking these receptor–ligand interactions, a particular subset of T cells is activated to recognize and respond to tumor cells. While such responses to immunotherapy are promising, they have only been effective in ∼20% of patients ( Murciano-Goroff et al., 2020 ).

Therefore, there is an urgent need to understand the underlying mechanism of lung adenocarcinoma from genome to immunotherapy. To address this unmet need, this Research Topic will focus on advancements related to lung adenocarcinoma (LUAD) and the identification of novel biomarkers as new therapy-determining or companion prognostic tools for the development of precise mechanism-based treatments.

Novel prognostic biomarkers for lung adenocarcinoma

The original articles published in the present Research Topic updated about novel prognostic biomarkers in lung adenocarcinoma patients through in silico approaches. In particular, Wang et al. F’s group assessed the roles of unlocking phenotypic plasticity (UPP) in immune status, prognosis, and treatment in patients with LUAD based on the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) database ( https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.941567/full ). They proposed UPP as a new and reliable prognosis indicator to predict the patient’s overall survival and help the clinician to predict therapeutic responses and make individualized treatment plans.

Similarly, Zhou X et al. investigated the expression of indolethylamine N-methyltransferase (INMT) and its clinical value as a prognostic biomarker in LUAD based on TCGA and Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) databases ( https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.946848/full ). They found that INMT expression was significantly downregulated in LUAD, and the low expression of INMT was associated with poor prognosis but favorable immunotherapy response in LUAD.

Song Y et al. highlighted the association of necroptosis with LUAD and its potential use in guiding immunotherapy based on transcriptomic and clinical data of patients from TCGA and GEO databases ( https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2022.1027741/full ). They analyzed 902 samples and identified a prognostic signature of five necroptosis-related genes that could be used to predict the prognosis of LUAD patients.

Additionally, Zhu X’s group focused their attention on the role of basement membranes (BMs) and their related genes for prognosis prediction in LUAD patients from TCGA and GEO databases ( https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/genetics/articles/10.3389/fgene.2023.1100560/full ). They used a training set of data and a verification cohort and identified a prognostic signature of ten BM-associated genes that could be used to predict the prognosis of LUAD patients and guide personalized treatment.

Zhang et al. investigated the relationship between cuproptosis and long non-coding RNAs (lncRNAs) in carcinogenesis and prognosis/treatment of LUAD patients based on transcriptomic data of 507 samples from TCGA database ( https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/pharmacology/articles/10.3389/fphar.2023.1236655/full ). They constructed a prognostic model associated with the prognosis of patients with LUAD undergoing therapy and confirmed their results through in-vitro experiments.

Finally, Liu R’s group has dedicated its work to studying the correlation between neutrophils and tumor development in LUAD based on data from the TCGA database and in-vitro experiments, identifying 30 hub genes that were significantly associated with neutrophil infiltration and developing a neutrophil scoring system associated with prognosis, and tumor immune microenvironment.

Relevant case reports

The present Research Topic also contains interesting, unusual, and noteworthy case reports that can help clinicians and scientists identify new trends, evaluate new therapeutic effects, as well as create new research questions. In particular, Hodges A et al. presented a 62-year female with Lynch syndrome, who developed an EGFR-positive lung adenocarcinoma highlighting the complex interplay of genetic cancer predisposition syndromes and the development of spontaneous driver mutations in the disease course and the subsequent management of tumors arising ( https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2023.1193503/full ).

Li H et al. presented a 35-year female with a rare lung cancer exhibiting choriocarcinoma features demonstrating the potential of chemo-immunotherapy in treating this aggressive subtype of lung cancer ( https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2024.1324057/abstract ).

Last but not least, Quanqing L et al. presented a 67-year female with a squamous cell carcinoma (NSCLC) that transforms into small cell carcinoma (SCLC) after five cycles of immunotherapy targeting PD-1 treatment (Sintilimab) of NSCLC ( https://www.frontiersin.org/journals/oncology/articles/10.3389/fonc.2024.1329152/full ). This histological transformation could represent a potential mechanism of cancer therapeutic resistance.

In conclusion, this Research Topic highlights the importance of good prognostic biomarkers in determining the most effective treatment and revolutionizing cancer precision medicine. The Research Topic of articles provides a comprehensive overview of current advancements in prognostic and therapeutic lung cancer biomarkers offering a substantive framework that informs ongoing scientific inquiry and clinical practice, aiming to improve the understanding and management of LUAD patients.

Author contributions

YM: Conceptualization, Validation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. MP: Conceptualization, Data curation, Validation, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing. EF: Conceptualization, Data curation, Supervision, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Acknowledgments

We deeply thank all the authors and reviewers who have participated in this Research Topic.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Bodor, J. N., Kasireddy, V., and Borghaei, H. (2018). First-line therapies for metastatic lung adenocarcinoma without a driver mutation. J. Oncol. Pract. 14 (9), 529–535. doi:10.1200/JOP.18.00250

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

Murciano-Goroff, Y. R., Warner, A. B., and Wolchok, J. D. (2020). The future of cancer immunotherapy: microenvironment-targeting combinations. Cell Res. 30 (6), 507–519. doi:10.1038/s41422-020-0337-2

Sung, H., Ferlay, J., Siegel, R. L., Laversanne, M., Soerjomataram, I., Jemal, A., et al. (2021). Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. Ca. Cancer J. Clin. 71 (3), 209–249. doi:10.3322/caac.21660

Keywords: solid cancer, cancer biomarkers, cancer prognosis, disease monitoring, lung cancer, precision medicine

Citation: Meng Y, Palmieri M and Frullanti E (2024) Editorial: Lung adenocarcinoma: from genomics to immunotherapy. Front. Genet. 15:1399127. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2024.1399127

Received: 11 March 2024; Accepted: 27 March 2024; Published: 09 April 2024.

Edited and reviewed by:

Copyright © 2024 Meng, Palmieri and Frullanti. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Elisa Frullanti, [email protected]

† These authors share last authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Help & Support

Stopping Lung Cancer Before It Progresses

by Vince Tedjasaputra, Ph.D. | April 17, 2024

- Lung Cancer

Lung cancer is still the leading cause of death by cancer in the U.S., with someone diagnosed about every two minutes. To address this, the American Lung Association has renewed a partnership with LUNGevity to fund innovative research to intercept lung cancer—that is, detecting and treating pre-cancerous cells before they have a chance to become malignant.

Accelerating Innovation

This partnership is not a typical research endeavor; it is part of the American Lung Association Research Institute’s new Accelerator Program , which seeks to form collaborations with government, industry and other non-profit organizations like LUNGevity who have a shared mission to improve lung health.

"Early detection of lung cancer is crucial to saving lives,” says Harold Wimmer, President and CEO of the American Lung Association, stressing how critical this partnership is. “By investing in research to intercept lung cancer at its earliest stages, we have the potential to revolutionize how we approach this disease and improve outcomes for patients."

Leading the Team

Heading this ambitious initiative are Dr. Avrum Spira , Boston Medical Center, and Dr. Steven Dubinett University of California, Los Angeles, who are esteemed leaders in the field of lung cancer research. Their collaborative project, titled “Intercept Lung Cancer Through Immune, Imaging & Molecular Evaluation In TIME,” seeks to define how lung cancer progresses.

By utilizing cutting-edge technologies like robot-assisted bronchoscopy, they aim to establish a timeline of pre-cancerous cell evolution into malignant cancer—a pivotal step toward early detection and intervention.

"This project represents an evolution of our ongoing efforts to understand and intercept lung cancer before it progresses,” reflects Dr. Spira. “By unraveling the molecular and immune mechanisms underlying lung cancer development, we can develop targeted strategies for early detection and intervention."

Continuing the Legacy of Impactful Lung Cancer Research

The partnership builds on a successful previous collaborative effort, which included research funded by the American Lung Association, LUNGevity Foundation and Stand Up To Cancer. This collaboration has already yielded significant findings, from mapping the pre-cancer genome to identifying enzymes and proteins associated with pre-malignant cells.

Here are a few of the recent breakthrough findings published by the Lung Cancer Interception Team:

- Unlocking Mechanisms of Cancer Treatment Resistance : The discovery of an enzyme called APOBEC3B, that influences how lung cancer develops resistance to EGFR-targeted therapy, which holds the promise of enhancing treatment effectiveness ( Nature Genetics, December 2023 ).

- Modeling how cancer cells change their DNA : A novel computational method allows scientists to study how cancer cells change their DNA, leading to innovations that can improve lung cancer treatments ( PLOS Computational Biology, October 2023 ).

- Insights into Immune Evasion : A comprehensive review which sheds light on how cancer cells evade detection by immune systems, providing a roadmap for the development of novel immunotherapeutic strategies ( Immunity, October 2023 ).