Another Word

From the writing center at the university of wisconsin-madison.

#essayhack: What TikTok can Teach Writing Centers about Student Perceptions of College Writing

By Holly Berkowitz, University of Tennessee at Chattanooga

There is a widespread perception that TikTok, the popular video-sharing social media platform, is primarily a tool of distraction where one mindlessly scrolls through bite-sized bits of content. However, due to the viewer’s ability to engage with short-form video content, it is undeniable that TikTok is also a platform from which users gain information; whether this means following a viral dance tutorial or learning how to fold a fitted sheet, TikTok houses millions of videos that serve as instructional tutorials that provides tips or how-tos for its over one billion active users.

That TikTok might be considered a learning tool also has implications for educational contexts. Recent research has revealed that watching or even creating TikToks in classrooms can aid learning objectives, particularly relating to language acquisition or narrative writing skills. In this post, I discuss the conventions of and consequences for TikToks that discuss college writing. Because of the popularity of videos that spotlight “how-tos” or “day in the life” style content, looking at essay or college writing TikTok can be a helpful tool for understanding some larger trends and student perceptions of writing. Due to the instructional nature of TikToks and the ways that students might be using the app for advice, these videos can be viewed as parallel or ancillary to the advice that a Writing Center tutor might provide.

A search for common hashtags including the words “essay,” “college writing,” or “essay writing hack” yields hundreds of videos that pertain to writing at the college level. Although there is a large variety in content due to the sheer amount of content, this post focuses on two genres of videos as they represent a large portion of what is shared: first, videos that provide tips or how-tos for certain AI tools or assignment genres and second, videos that invite the viewer to accompany the creator as they write a paper under a deadline. Shared themes include attempts to establish peer connections and comfort viewers who procrastinate while writing, a focus on writing speed and concrete deliverables (page count, word limit, or hours to write), and an emphasis on digital tools or AI software (especially that which is marked as “not cheating”). Not only does a closer examination into these videos help us meet writers where they are more precisely, but it also draws writing center workers’ attention to lesser known digital tools or “hacks” that students are using for their assignments.

“How to write” Videos

Videos in the “how to” style are instructional and advice-dispensing in tone. Often, the creator utilizes a digital writing aid or provides a set of writing tips or steps to follow. Whether these videos spotlight assistive technologies that use AI, helpful websites, or suggestions for specific forms of writing, they often position writing as a roadblock or adversary. Videos of this nature attempt to reach viewers by promising to make writing easier, more approachable, or just faster when working under a tight deadline; they almost always assume the writer in question has left their writing task to the last possible moment. It’s not surprising then that the most widely shared examples of this form of content are videos with titles like “How to speed-write long papers” or “How to make any essay longer” (this one has 32 million views). It is evident that this type of content attempts to target students who suffer from writing-related anxiety or who tend to procrastinate while writing.

Sharing “hacks” online is a common practice that manifests in many corners of TikTok where content creators demonstrate an easier or more efficient way of achieving a task (such as loading a dishwasher) or obtaining a result (such as finding affordable airline tickets). The same principle applies to #essay TikTok, where writing advice is often framed as a “hack” for writing faster papers, longer papers, or papers more likely to result in an A. This content uses a familiar titling convention: How to write X (where X might be a specific genre like a literature review, or just an amount of pages or words); How to write X in X amount of time; and How to write X using this software or AI program. The amount of time is always tantalizingly brief, as two examples—“How to write a 5 page essay in 2 mins” and “How to write an essay in five minutes!! NO PLAGIARISM!!”—attest to. While some of these are silly or no longer useful methods of getting around assignment parameters, they introduce viewers to helpful research and writing aids and sometimes even spotlight Writing Center best practices. For instance, a video by creator @kaylacp called “Research Paper Hack” shows viewers how to use a program called PowerNotes to organize and code sources; a video by @patches has almost seven million views and demonstrates using an AI bot to both grade her paper and provide substantive feedback. Taken as a whole, this subsect of TikTok underscores that there is a ready audience for content that purports to assist writers in meeting the deliverables of a writing assignment using a path of least resistance.

Similarly, TikTok contains myriad videos that position the creator as a sort of expert in college writing and dispense tips for improving academic writing and style. These videos are often created by upperclassmen who claim to frequently receive As on essays and tend to use persuasive language in the style of an infomercial, such as “How to write a college paper like a pro,” “How to write research papers more efficiently in 5 easy steps!” or “College students, if you’re not using this feature, you’re wasting your time.” The focus in these videos is even more explicit than those mentioned above, as college students are addressed in the titles and captions directly. This is significant because it prompts users to engage with this content as they might with a Writing Center tutor or tutoring more generally. These videos are sites where students are learning how to write more efficiently but also learning how their college peers view and treat the writing process.

The “how to write” videos share several common themes, most prevalent of which is an emphasis on concrete deliverables—you will be able to produce this many pages in this many minutes. They also share a tendency to introduce or spotlight different digital tools and assistive technologies that make writing more expedient; although several videos reference or demonstrate how to use ChatGPT or OpenAI, most creators attempt to show viewers less widely discussed platforms and programs. As parallel forms of writing instruction, these how-tos tend to focus on quantity over quality and writing-as-product. However, they also showcase ways that AI can be helpful and generative for writers at all stages. Most notably they direct our attention to the fact that student writers consistently encounter writing- and essay- related content while scrolling TikTok.

Write “with me” Videos

Just as the how-to style videos target writers who view writing negatively and may have a habit of procrastinating writing assignments, write “with me” videos invite the viewer to join the creator as they work. These videos almost always include a variation of the phrase— “Write a 5- page case analysis w/ me” or “pull an all nighter with me while I write a 10- page essay.” One of the functions of this convention is to establish a peer-to-peer connection with the viewer, as they are brought along while the creator writes, experiences writer’s block, takes breaks, but ultimately completes their assignment in time. Similarly to the videos discussed above, these “with me” videos also center on writing under a deadline and thus emphasize the more concrete deliverables of their assignments. As such, the writing process is often made less visible in favor of frequent cuts and timestamps that show the progression toward a page or word count goal.

One of the most common effects of “with me” videos is to assure the viewer that procrastinating writing is part and parcel of the college experience. As the content creators grapple with and accept their own writing anxieties or deferring habits, they demonstrate for the viewer that it is possible to be both someone who struggles with writing and someone who can make progress on their papers. In this way, these videos suggest to students that they are not alone in their experiences; not only do other college students feel overwhelmed with writing or leave their papers until the day before they are due, but you can join a fellow student as they tackle the essay writing process. One popular video by @mercuryskid with over 6 million views follows them working on a 6000 word essay for which they have received several extensions, and although they don’t finish by the end of the video, their openness about the struggles they experience while writing may explain its appeal.

Indeed, in several videos of this kind the creator centers their procrastination as a means of inviting the viewer in; often the video will include the word in the title, such as “write 2 essays due at 11:59 tonight with me because I am a chronic procrastinator” or “write the literature essay i procrastinated with me.” Because of this, establishing a peer connection with the hypothetical viewer is paramount; @itskamazing’s video in which she writes a five page paper in three hours ends with her telling the viewer, “If you’re in college, you’re doing great. Let’s just knock this semester out.” One video titled “Writing essays doesn’t need to be stressful” shows a college-aged creator explaining what tactics she uses for outlining and annotating research to make sure she feels prepared when she begins to write in earnest. Throughout, she directly hails the viewer as “you” and attempts to cultivate a sense of familiarity with the person on the other side of the screen; in some moments her advice feels like listening in on a one-sided Writing Center session.

A second aspect of these “with me” videos is an intense focus on the specifics of a writing task. The titles of these videos usually follow a formula that invites the viewer with the writer as they write X amount in X time, paralleling the structure of how-to-write videos. The emphasis here, due to the last-minute nature of the writing contexts, is always on speed: “write a 2000- word essay with me in 4.5 hours” or “Join me as I write a 10- page essay that is due at 11:59pm.” Since these videos often need to cover large swaths of time during which the creator is working, there are several jumps forward in time, sped up footage, and text stamps or zoom-ins that update the viewer on how many pages or words the writer has completed since the last update. Overall, this brand of content demonstrates how product-focused writers become when large amounts of writing are completed in a single setting. However, it also makes this experience seem more manageable to viewers, as we frequently see writers in videos take naps and breaks during these high-stakes writing sessions. Furthermore, although the writers complain and appear stressed throughout, these videos tend to close with the writer submitting their papers and celebrating their achievement.

Although these videos may send mixed messages to college students using TikTok who experience struggles with writing productivity, they can be helpful for viewers as they demonstrate the shared nature of these struggles and concerns. Despite the overarching emphasis on the finished product, the documentary-style of this content shows how writing can be a fraught process. For tutors or those removed from the experience of being in college, these videos also illuminate some of the reasons students procrastinate writing; we see creators juggling part-time jobs, other due dates, and family obligations. This genre of TikToks shows the power that social media platforms have due to the way they can amplify the shared experience of students.

To conclude, I gesture toward a few of the takeaways that #essay and #collegewriting TikTok might provide for those who work in Writing Centers, especially those who frequently encounter students who struggle with procrastination. First, because TikTok is a video-sharing platform, the content often shows a mixture of writing process and product. Despite a heavy emphasis in these videos on the finished product that a writer turns in to be graded, several videos necessarily also reveal the steps that go into writing, even marathon sessions the night before a paper is due. We primarily see forward progress but we also see false starts and deletions; we mostly see the writer once they have completed pre-writing tasks but we also see analyzing a prompt, outlining, and brainstorming. Additionally, this genre of TikTok is instructive in that it shows how often students wait until before a paper is due to begin and just how many writers are working solely to meet a deadline or deliverable. While as Writing Center workers we cannot do much to shift this mindset, we can make a more considerable effort to focus on time management and executive functioning skills in our sessions. Separating the essay writing process into manageable chunks or steps appears to be a skill that college students are already seeking to develop independently when they engage on social media, and Writing Centers are equipped to help students refine these habits. Finally, it is worth considering the potential for university Writing Center TikTok accounts. A brief survey of videos created by Writing Center staff reveals that they draw on similar themes and tend to emphasize product and deliverables—for example, a video titled “a passing essay grade” that shows someone going into the center and receiving an A+ on a paper. Instead, these accounts could create a space for Writing Centers to actively contribute to the discourse on college writing that currently occupies the app and create content that parallels a specific Writing Center or campus’s values.

Holly Berkowitz is the Coordinator of the Writing and Communication Center at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga. She recently received her PhD from the University of Wisconsin–Madison, where she also worked at the UW-Madison Writing Center. Although she does not post her own content, she is an avid consumer of TikTok videos.

The Grim Reality of Banning TikTok

T he U.S. government, once again, wants to ban TikTok. The app has become an incontrovertible force on American phones since it launched in 2016, defining the sounds and sights of pandemic-era culture. TikTok’s burst on the scene also represented a first for American consumers, and officials—a popular social media app that wasn’t started on Silicon Valley soil, but in China.

On March 13, the U.S. House of Representatives passed a bill to force TikTok’s Chinese parent company, ByteDance, to sell TikTok or else the app will be banned on American phones. The government will fine the two major mobile app stores and any cloud hosting companies to ensure that Americans cannot access the app.

While fashioned as a forced divestiture on national security grounds, let’s be real: This is a ban. The intent has always been to ban TikTok, to punish it and its users without solving any of the underlying data privacy issues lawmakers claim to care about. Texas Rep. Dan Crenshaw said it outright : “No one is trying to disguise anything… We want to ban TikTok.”

But, as such, a ban of TikTok would eliminate an important place for Americans to speak and be heard. It would be a travesty for the free speech rights of hundreds of millions of Americans who depend on the app to communicate, express themselves, and even make a living. And perhaps more importantly, it would further balkanize the global internet and disconnect us from the world.

Read more: What to Know About the Bill That Could Get TikTok Banned in the U.S.

This isn’t the first time the government has tried to ban TikTok: In 2021, former President Donald Trump issued an executive order that was halted in federal court when a Trump-appointed judge found it was “arbitrary and capricious” because it failed to consider other means of dealing with the problem. Another judge found that the national security threat posted by TikTok was “phrased in the hypothetical.” When the state of Montana tried to ban the app in 2023, a federal judge found it “oversteps state power and infringes on the constitutional rights of users,” with a “pervasive undertone of anti-Chinese sentiment.”

Trump also opened a national security review with the power to force a divestment, something Biden has continued to this day with no resolution; and last year, lawmakers looked poised to pass a bill banning TikTok, but lost steam after a high-profile grilling of its top executive. (Trump has done an about-face on the issue and recently warned that banning TikTok will only help its U.S. rivals like Meta.)

TikTok stands accused of being a conduit for the Chinese Communist Party, guzzling up sensitive user data and sending it to China. There’s not much evidence to suggest that’s true, except that their parent company ByteDance is a Chinese company, and China’s government has its so-called private sector in a chokehold. In order to stay compliant, you have to play nice.

In all of this, it’s important to remember that America is not China. America doesn't have a Great Firewall with our very own internet free from outside influences. America allows all sorts of websites that the government likes, dislikes, and fears onto our computers. So there’s an irony in allowing Chinese internet giants onto America’s internet when, of course, American companies like Google and Meta’s services aren’t allowed on Chinese computers.

And because of America’s robust speech protections under the First Amendment, the U.S. finds itself playing a different ballgame than the Chinese government in this moment. These rights protect Americans against the U.S. government, not from corporations like TikTok, Meta, YouTube, or Twitter, despite the fact that they do have outsized influence over modern communication. No, the First Amendment says that the government cannot stop you from speaking without a damned good reason. In other words, you’re protected against Congress—not TikTok.

The clearest problem with a TikTok ban is it would immediately wipe out a platform where 170 million Americans broadcast their views and receive information—sometimes about political happenings. In an era of mass polarization, shutting off the app would mean shutting down the ways in which millions of people—even those with unpopular views—speak out on issues they care about. The other problem is that Americans have the constitutional right to access all sorts of information—even if it’s deemed to be foreign propaganda. There’s been little evidence to suggest that ByteDance is influencing the flow of content at the behest of the Chinese government, though there’s some reports that are indeed worrying, including reports that TikTok censored videos related to the Tiananmen Square massacre, Tibetan independence, and the banned group Falun Gong.

Still, the Supreme Court ruled in 1964 that Americans have the right to receive what the government deems to be foreign propaganda. In Lamont v. Postmaster General , for instance, the Court ruled that the government couldn’t halt the flow of Soviet propaganda through the mail. The Court essentially said that the act of the government stepping in and banning propaganda would be akin to censorship, and the American people need to be free to evaluate these transgressive ideas for themselves.

Further, the government has repeatedly failed to pass any federal data privacy protections that would address the supposed underlying problem of TikTok gobbling up troves of U.S. user data and handing it to a Chinese parent company. Biden only made moves in February 2024 to prevent data brokers from selling U.S. user data to foreign adversaries like China, arguably a problem much bigger than one app. But the reality is that the government has long been more interested in banning a media company than dealing with a real public policy issue.

There is legitimate concern in Washington and elsewhere that it’s not the government that controls so much of America’s speech, but private companies like those bred in Silicon Valley. But the disappearance of TikTok would further empower media monopolists like Google and Meta, who already control about half of all U.S. digital ad dollars, and give them a tighter choke hold over our communication. There’s already a paucity of platforms where people speak; removing TikTok would eliminate one of the most important alternatives we have.

Since it launched in 2016, TikTok has been the most influential social media app in the world, not because it affects public policy or necessarily creates monoculture—neither are particularly true, in fact—but because it has given people a totally different way to spend time online. In doing so, it disrupted the monopolies of American tech companies like Meta, which owns Facebook and Instagram, and forced every rival to in some way mimic its signature style. There’s Facebook and Instagram Reels, YouTube Shorts, Snapchat Spotlight, and every other app seems to be an infinitely-scrolling video these days.

Still, Americans choose to use TikTok and their conversations will not easily port over to another platform in the event of it being banned. Instead, cutting through the connective tissue of the app will sever important ways that Americans—especially young Americans—are speaking at a time when those conversations are as rich as ever.

The reality is that if Congress wanted to solve our data privacy problems, they would solve our data privacy problems. But instead, they want to ban TikTok, so they’ve found a way to try and do so. The bill will proceed to the Senate floor, then to the president’s desk, and then it will land in the U.S. court system. At that point, our First Amendment will once again be put to the test—a free speech case that’s very much not in the abstract, but one whose results will affect 170 million Americans who just want to use an app and have their voices be heard.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- Coco Gauff Is Playing for Herself Now

- Scenes From Pro-Palestinian Encampments Across U.S. Universities

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at [email protected]

Kyle Chayka Industries

Essay: How do you describe TikTok?

The automatic culture of the world's favorite new social network..

Hi! This is a 3,400-word essay about a technology that was totally new to me as of a few weeks ago. You can click the headline to read it in your browser. It’s a total experiment, so please let me know what you think.

This newsletter is a running series of essays on algorithmic culture and work updates from me, Kyle Chayka . Subscribe here .

For someone who writes about technology, I’m not really an early adopter. I don’t use virtual-reality goggles or participate in Twitch streams. Like everyone on the internet, I heard a lot about TikTok — teens! short videos! “ hype houses ”! — but for a long time I didn’t think I needed to try it out. How would another social network fit into my life? Don’t Twitter and Instagram cover my professional and personal needs at this point? (Snapchat I skipped over entirely.) What could TikTok, which serves an infinite stream of sub-60-second video clips, add, especially if I don’t care about meme-dances, which seemed to be its main purpose?

Then, out of some combination of boredom and curiosity, like everything else these days, I downloaded the app. What I found is that you don’t just try TikTok; you immerse yourself in it. You sink into its depths like a 19th-century diver in a diving bell. More than any other social network since MySpace it feels like a new experience, the emergence of a different kind of technology and a different mode of consuming media. In this essay I want to try to describe that experience, without any news hooks, experts, theory, or data — just a personal encounter.

The literary term “ ekphrasis ” usually refers to a detailed description of a piece of visual art in a text, translating it (in a sense) into words. Lately I’ve been thinking about ekphrasis of technology and media: How do you communicate what using or viewing something is like? Some of my favorite writing might fall into this vein. Junichiro Tanizaki’s 1933 essay “ In Praise of Shadows ” narrates the Japanese encounter with Western technology like electric lights and porcelain toilets. Walter Benjamin’s 1936 “ The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction ” shows how the rise of photography changed how people looked at visual art. By describing such experiences as exactly as possible, these essays become valuable artifacts in their own right, documenting historic shifts in human perception that happened as a result of tools we invented.

We can’t return to the headspace of buildings without electric lights or a time when photography was scarce instead of omnipresent, but the texts allow us a glimpse. So this is my experiment: an ekphrasis of TikTok, while it’s still fresh.

When you begin your TikTok journey, you are not faced with a choice of accounts to follow. Where Twitter and Instagram ask you to build your list yourself (the former more than the latter) TikTok simply launches you into the waterfall of content. You can check a few boxes as to which subjects you’re interested in — food, crafts, video games, travel — or not. Then there is the main feed, labeled “For You,” an evocation of customization and personal intimacy. Videos start playing, each clip looping until you make it stop. You might start seeing, as I did, minute-long clips of:

— Gravestones being scraped down

— Wax being melted to seal letters

— An animated role-playing game

— Firefighters making shepherds pie

— Tours of luxury apartments

— Students playing pranks on their teachers

— Dogs and cats doing funny things

The videos are flashes of narrative, many arduously constructed and edited, each self-contained but linked to the next by the shape of the container, the iPhone screen and the app feed. It’s like watching a montage of movie trailers, each crafted to addict your eye and ear, but with each new clip you have to begin constructing the story over again. Will the cat do something funny? Will the couple break up? Will this guy chug five beers? Or it’s like the flickering nonsense of images and text as a film spool runs out .

The mechanism to navigate the TikTok feed is your thumb swiping, like a gondolier’s paddle, up to move forward to new content, down to go back to what you’ve already seen. This one interaction is enough to allow For You to get to know your content preferences. You either watch a video to completion and then maybe like or share it, or you skip it and move on to the next.

The true pilot of the feed, however, is not the user but the recommendation algorithm, the equation that decides which video gets served to you next. More than any other social network, TikTok’s core product is its algorithm. We complain about being served bad Twitter ads or Instagram not showing us friends’ accounts, as if they’ve suddenly stopped existing, but it’s harder to fault the TikTok algorithm if only because it’s so much better at delivering a varied stream of content than its predecessors.

A Spotify autoplay station, for example, most often follows the line of an artist or genre, serving relatively similar content over and over again. But TikTok recognizes that contrast is just as important as similarity to maintain our interest. It creates a shifting feed of topics and formats that actually feels personal, the way my Twitter feed, built up over more than a decade, feels like a reflection of my self.

But I know who I follow on Twitter; they are voices I’ve chosen to incorporate into my feed. On TikTok, I never know where something’s coming from or why, only if I like it. There is no context. If Twitter is all about provenance — trusted people signing off on each other’s content, retweeting endorsements — TikTok is simply about the end result. Each video is evaluated on its own merits, one at a time.

You can feel the For You feed trying subjects out on you. Dogs? Yes. Cats? Not so much. Rural Chinese fishing? Sure. Scooter tricks? No. Skateboarding? Yes. Fingerpicked guitar outside a cabin? Duh. And through the process of trial and error you get an assortment of videos that are on their own niche but put together resemble something like individual taste . It’s a mix as quirky as your own personal interests usually feel to you, though the fact that all of this content already exists on the platform gradually undercuts the sense of uniqueness: If many other people besides you didn’t also like it, it wouldn’t be there.

A like count appears on the right side of each video, reassuring you that 6,000 other people have also enjoyed this clip enough to hit the button. Usually, the higher number does signify a better video, unlike tweets, for which the opposite is usually true. You can click into a comment section on each TikTok, too, which feel like YouTube comment sections: people jockeying to write the best riff or joke, bonus content after you watch the clip. There are no time stamps on the main feed. Unlike other social networks, it’s intentionally difficult to figure out when a TikTok video was originally posted, and many accounts repost popular videos anyway. This lends the feed an atmosphere of eternal present: It’s easy to imagine that everything you’re watching is happening right now , a gripping quality that makes it even harder to stop watching.

Over the time I’ve been on TikTok the content of my feed has moved through phases. I can’t be sure how much the shifts are baked in to the system and how much they are a result of me engaging with different content (I’m not reporting on the structure of the algorithm here, just spelunking). There was a heavy skateboarding phase at first, but the mix has evolved into cooking lessons, clips of learning Chinese, home construction tips from This Old House, art-making close-ups, and early 2000s video games. If you search for a particular hashtag, hit like on a few videos, or follow an account, the For You algorithm tweaks your feed, adding in a bit more of that type of content.

(A note on content mixture: “The mix” is famously how Tina Brown described the combination of different kinds of stories in Vanity Fair when she was the magazine’s very successful editor-in-chief in the ‘80s. Brown’s mix was hard-hitting news, fluffy celebrity profiles, glamorous fashion shoots, and smart critical commentary, all combined into one magazine. TikTok automates the mix of all these topics, going farther than any other platform to mimic the human editor.)

A sense emerges of teaching the algorithm what you like, bearing with it through periods of irrelevance and engaging in a way that shapes your feed. I barely look at the tab that shows me videos from people I actually follow, but I still follow them to make them show up more often in my For You feed. The process inspires patience and empathy, the way building a piece of IKEA furniture makes you like it more . It’s easy to get mad at Twitter because its algorithmic intrusions are so obvious; it’s harder with TikTok when the algorithm is all there is. The feed is a seamless environment that the user is meant to stay within.

I didn’t tell TikTok I was interested in sensory deprivation tanks, but through some combination of randomness, metrics, and triangulation of my interests based on what else I engaged with, the app delivered a single video from a float spa and I immediately followed the account. Such specific genres of content are available elsewhere on the internet — I could follow a sensory deprivation YouTube channel or Instagram account — but the TikTok feed centralizes them and titrates the niche topic into my feed as often as I might want to see it, maybe one out of a hundred videos. After all, one video doesn’t mean I want dozens more of the same kind, as the YouTube algorithm seems to think.

Before the 2010s we used to watch cable television, sitting on the couch with the remote pointed actively at the screen. If the show on one channel was boring, we changed it. If everything was boring, we engaged in an activity called channel flipping, switching continuously one to the next until something caught our eye. (On-demand streaming means we now flip through thumbnails more than channels; platform-flipping is the new channel-flipping.) TikTok is an eternal channel flip, and the flip is the point: there is no settled point of interest to land on. Nothing is meant to sustain your attention, even for cable TV’s traditional 10 minutes between commercial breaks.

Like cable television, the viewer does not select the content on TikTok, only whether they want to watch it at that moment or not. It’s a marked contrast to how, in the past decade, social media platforms marketed themselves as offering user agency: you could follow anything or anyone you want, breaking traditional media’s hold on audiences. Instead, TikTok’s For You offers the passivity of linear cable TV with the addition of automated, customized variety and without the need for human editors to curate content or much action from the user to choose it. (Passivity is a feature; Netflix just announced that it’s exploring a version of linear TV .) Like Facebook , and unlike streaming, TikTok also claims to offload the risk of being an actual publisher: the content is all user-generated. Thus it’s both cheap and infinite.

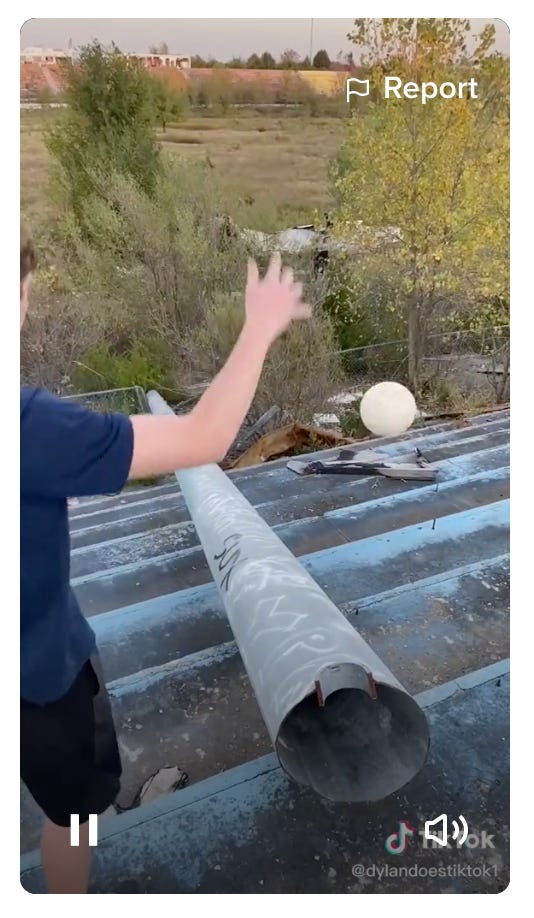

The passivity induces a hypnotized flow state in the user. You don’t have to think, only react. The content often reinforces this thoughtlessness. It’s ephemera, fragments of the human mundane; Rube Goldberg machines are very popular. Sure, you can learn about food or news, but the most essentially TikTok thing I’ve seen in the past few days is a video of a young man who took a giant ball he made of beige rubber bands to an abandoned industrial site and bounced it around, off ledges and down cement steps, in the violet haze of early dusk. The clip is calm and quiet but also surreal, like a piece of video art you might watch for 15 minutes in a gallery. It has no symbolism, no story arc, only a pleasant absence of meaning and the brain-tickling pleasure of the ball gently squishing when it hits a surface, like an alien exploring the earth, unaccustomed to gravity.

I’m biased in favor of such ambient content, which is probably why I get so much of it. But numb immersion — like a sensory deprivation tank — seems to be the point of the platform. On Twitter we get breaking news; on Instagram we see our friends and go shopping; on Facebook we (not me personally) join groups and share memes. On TikTok we are simply entertained. This is not to discount it as a very real force for politics, activism, and the business of culture, or a vehicle to create content and join in conversations. But for users, pure consumption is encouraged. The best bodily position in which to watch TikTok is supine, muscles slack, phone above your face like it’s an endless tunnel into the air.

Sometimes a TikTok binge — short and intense until you get sick of it, like a salvia trip — has the feeling of a game. You keep flipping to the next video as if in search of some goal, though there are only ever more videos. You want to come to an end, though there is no such thing. This stumbling process is why users describe encountering a new subject matter as “finding [topic] TikTok,” like Cooking TikTok or Tiny House TikTok or Carpentry TikTok. There’s a sense of discovery because you wouldn’t necessarily know how to get there otherwise, only through the munificence of the algorithm. A limiting of possibilities is recast as a kind of magic.

What is the theory of media that TikTok injects into the world? What are the new aesthetic standards that it will set as it becomes even more popular, beyond its current 850 million active users? It seems to combine Tumblr-style tribal niches with the brevity and intimacy of Instagram stories and the scalability of YouTube, where mainstream fame is most possible. The startup Quibi received billions of dollars of investment to bet on short-form video watched on phones. The company shut down within eight months of launch, but it wasn’t wrong about the format; it just produced terrible content (see my review of the service for Frieze ). TikTok is compelling because it’s so wide, a social network with the userbase of Facebook but fully multimedia, with the kinds of expensive-looking video editing and effects we’re used to on television. The platform presents media (or life itself?) as a permanent reality TV show, and you can tune in to any corner of it at any time.

TikTok isn’t limited to power users or a particular demographic (as in the case of the mutual addiction of Twitter and journalists), and that’s largely because of the adeptness of its algorithmic feed. There is no effort required to fine tune it, only time and swiping. Though the interface looks a little messy, it’s actually relatively simple, a quality that Instagram has abandoned under Facebook’s ownership in favor of cramming in every feature and format possible. (Where do we post what on there now — what’s a grid post, a story, or a reel, which are just Instagram’s shitty TikTok clone?) In fact, just surfing TikTok feels vaguely creative, as if you move through the field of content with your mind alone.

Even if you are only watching, you are a part of TikTok. Internet culture has always been interactive; part of the joy of Lolcats was that you could make your own, using the template as a tool for self-expression and inside jokes. In recent years that kind of creative self-expression via social media has fallen by the wayside in favor of retweets, shares, and likes, centralizing authority around a few influential accounts and pushing the emphasis toward brands (which buy ads and drive revenue) and consumerism. TikTok returns triumphantly to the lowbrow, the absurd, the unimportant.

The culture that it perpetuates are memes and patterns, like the dance moves that users assign to specific clips of songs. Audio is a way to navigate the platform: You can browse all the videos made to a particular soundtrack, making it very potent for spreading music. Users also create reaction videos to other videos, showing a selfie shot next to the original clip. Everything is participatory, and the nature of the algorithm makes it so that a video from an unknown account can go as viral as easily as one from a famous account. (This is true of all social networks but particularly extreme on TikTok.) The singular TikTok is less important than the continued flow of the feed and the emergence of recognizable tropes of TikTok culture that get traded back and forth, like the “ I Ain’t Seen Two Pretty Best Friends ” meme. The game is to interpolate that phrase into a video, sometimes into an otherwise straight-faced script: the surprise of the meme line, which is more absurdist symbol than meaningful language, tips you to the fact that it’s a joke.

In his aforementioned essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” Walter Benjamin wrote that “aura” was contained in the physical presence of a unique work of art; it induced a special feeling that wasn’t captured by the reproducible photograph. By now we’ve long accepted that photographs can be art, too; even if they’re reproductions, they still maintain an aura. The evolution that I’m grasping for here — having started this paragraph over many times — is that now, in our age of the reproducibility of anything, the meaning of the discrete work of art itself has weakened. The aura is not contained within a single specific image, video, or physical object but a pattern that can be repeated by anyone without cheapening its power — in fact, the more it’s repeated, the more its impact increases. The unit of culture is the meme, its original author or artist less important than its primary specimens, which circulate endlessly, inspiring new riffs and offshoots. TikTok operates on and embraces this principle.

Could it be that we’re encouraged to assign some authorship to the algorithm itself, as the prime actor of the platform? After all it’s the equation that’s bringing us this smooth, entrancing feed, that’s encouraging creators to create and consumers to consume. I don’t think that’s true, though, or at least not yet. We have to remember that the algorithm is also the work of its human creators at Bytedance in China, who have in the past been directed to “suppress posts created by users deemed too ugly, poor, or disabled for the platform” as well as censor political speech, according to The Intercept . Recommendation algorithms can be tools of soft censorship, subtly shaping a feed to be as glossy, appealing, and homogenous as possible rather than the truest reflection of either reality or a user’s desires. In Hollywood, a producer tells you if you’re not hot enough to be an actor; on TikTok, the algorithm lets you know if you don’t fit the mold.

As it is, TikTok molds what and how I consume more than what I want to create. I feel no drive to make a TikTok video, maybe because the platform’s demographic is younger than I am and it still requires more video editing than I can handle, though it can also algorithmically crop video clips to moments of action. But when I switch over to Instagram and watch the automatic flip of stories from my friends and various brands, it suddenly feels boring and dead, like going from color TV back to black and white. I don’t want to only get content from people I follow; I want the full breadth of the platform, perfectly filtered. The grid of miscellany of Instagram’s discover tab doesn’t stand up to TikTok’s total immersion.

TikTok’s feed is finely tuned and personalized, but I think what’s more important is how it automates the entire experience of online consumption. You don’t have to decide what you’re interested in; you just surrender to the platform. Automation gets disguised as customization. That makes the structure and priorities of the algorithm even more important as it increasingly determines what we watch, read, and hear, and what people are incentivized to create in digital spaces to get attention. And TikTok absolutely wants all of your attention. It’s not about casual browsing, not glancing at Twitter to see the latest news or checking your friend’s Instagram profile for updates. It’s a move directly toward an addiction that will be incredibly profitable for the company. And the more we trust that algorithmic feed, the easier it will be for the app to exploit its audiences.

This was an interesting experiment to write because I had no formal constraints from an external publication and of course no editing or feedback before publishing it. I wrote it just to document an obsession, and as with many obsessions, it’s fading a bit as I write it all out. At this point I’ve documented all the thoughts I have currently, in a fairly loose way.

I would really like messages about this piece! Did it work, did it not work? Is this productive or not? There are more essays I’d like to write like this, without the pressure to fully compel public readers. But its main utility is to share ideas and start conversations, so it needs to accomplish at least that.

Please comment, email me by replying, tweet about this, post it on your LinkedIn, or whatever platform you choose. Make a TikTok reaction video.

If you like this piece, please hit the heart button below! It helps me reach more readers on Substack. Email me at [email protected] or reply. Also:

— Follow me on Twitter

— Buy my book on minimalism, The Longing for Less

— Read more of my writing: kylechayka.com

Ready for more?

Find anything you save across the site in your account

How TikTok Holds Our Attention

By Jia Tolentino

Marcella is eighteen and lives in a Texas suburb so quiet that it sometimes seems like a ghost town. She downloaded TikTok last fall, after seeing TikTok videos that had been posted on YouTube and Instagram. They were strange and hilarious and reminded her of Vine, the discontinued platform that teen-agers once used for uploading anarchic six-second videos that played on a loop. She opened TikTok, and it began showing her an endless scroll of videos, most of them fifteen seconds or less. She watched the ones she liked a few times before moving on, and double-tapped her favorites, to “like” them. TikTok was learning what she wanted. It showed her more absurd comic sketches and supercuts of people painting murals, and fewer videos in which girls made fun of other girls for their looks.

When you watch a video on TikTok, you can tap a button on the screen to respond with your own video, scored to the same soundtrack. Another tap calls up a suite of editing tools, including a timer that makes it easy to film yourself. Videos become memes that you can imitate, or riff on, rapidly multiplying much the way the Ice Bucket Challenge proliferated on Facebook five years ago.

Marcella was lying on her bed looking at TikTok on a Thursday evening when she began seeing video after video set to a clip of the song “Pretty Boy Swag,” by Soulja Boy. In each one, a person would look into the camera as if it were a mirror, and then, just as the song’s beat dropped, the camera would cut to a shot of the person’s doppelgänger. It worked like a punch line. A guy with packing tape over his nose became Voldemort. A girl smeared gold paint on her face, put on a yellow hoodie, and turned into an Oscar statue. Marcella propped her phone on her desk and set the TikTok timer. Her video took around twenty minutes to make, and is thirteen seconds long. She enters the frame in a white button-down, her hair dark and wavy. She adjusts her collar, checks her reflection, looks upward, and—the beat drops—she’s Anne Frank.

Marcella’s friends knew about TikTok, but almost none of them were on it. She didn’t think that anyone would see what she’d made. Pretty quickly, though, her video began getting hundreds of likes, thousands, tens of thousands. People started sharing it on Instagram. On YouTube, the Swedish vlogger PewDiePie, who has more than a hundred million subscribers, posted a video mocking the media for suggesting that TikTok had a “Nazi problem”—Vice had found various accounts promoting white-supremacist slogans—then showed Marcella’s video, laughed, and said, “Never mind, actually, this does not help the case I was trying to make.” (PewDiePie has been criticized for employing anti-Semitic imagery in his videos, though his fans insist that his work is satire.) Marcella started to get direct messages on TikTok and Instagram, some of which called her anti-Semitic. One accused her of promoting Nazism. She deleted the video.

In February, a friend texted me a YouTube rip of Marcella’s TikTok. I was alone with my phone at my desk on a week night, and when I watched the video I screamed. It was terrifyingly funny, like a well-timed electric shock. It also made me feel very old. I’d seen other TikToks, mostly on Twitter, and my primary impression was that young people were churning through images and sounds at warp speed, repurposing reality into ironic, bite-size content. Kids were clearly better than adults at whatever it was TikTok was for—“I haven’t seen one piece of content on there made by an adult that’s normal and good,” Jack Wagner, a “popular Instagram memer,” told The Atlantic last fall —though they weren’t the only ones using the platform. Arnold Schwarzenegger was on TikTok, riding a minibike and chasing a miniature pony. Drag queens were on TikTok, opera singers were on TikTok, the Washington Post was on TikTok, dogs I follow on Instagram were on TikTok. Most important, the self-made celebrities of Generation Z were on TikTok, a cohort of people in their teens and early twenties who have spent a decade filming themselves through a front-facing camera and meticulously honing their understanding of what their peers will respond to and what they will ignore.

I sent an e-mail to Marcella. (That’s her middle name.) She’s from a military family, and likes to stay up late listening to music and writing. Marcella is Jewish, and she and her brothers were homeschooled. Not long before she made her video, her family had stopped at a base to renew their military I.D.s. One of her brothers glanced at her new I.D. and joked, accurately, that she looked like Anne Frank.

In correspondence, Marcella was as earnest and thoughtful as her video had seemed flip. She understood that it could seem offensive out of context—a context that was invisible to nearly everyone who saw it—and she was sanguine about the angry messages that she’d received. TikTok, like the rest of the world, was a mixed bag, she thought, with bad ideas, and cruelty, and embarrassment, but also with so much creative potential. Its ironic sensibility was perfectly suited for people her age, and so was its industrial-strength ability to turn non-famous people into famous ones—even if only temporarily, even if only in a minor way. Marcella had accepted her brush with Internet fame as an odd thrill, and not an entirely foreign one: her generation had grown up on YouTube, she noted, watching ordinary kids become millionaires by turning on laptop cameras in their bedrooms and talking about stuff they like. The videos that I’d been seeing, chaotic and sincere and nihilistic and very short, were the natural expressions of kids who’d had smartphones since they were in middle school, or elementary school. TikTok, Marcella explained, was a simple reaction to, and an absurdist escape from, “the mass amounts of media we are exposed to every living day.”

TikTok has been downloaded more than a billion times since its launch, in 2017, and reportedly has more monthly users than Twitter or Snapchat. Like those apps, it’s free, and peppered with advertising. I downloaded TikTok in May, adding its neon-shaded music-note logo to the array of app icons on my phone. TikTok’s parent company, ByteDance, is based in China, which, in recent years, has invested heavily and made major advances in artificial intelligence. After a three-billion-dollar investment from the Japanese conglomerate SoftBank, last fall, ByteDance was valued at more than seventy-five billion dollars, the highest valuation for any startup in the world.

I opened the app, and saw a three-foot-tall woman making her microwave door squeak to the melody of “Yeah!,” by Usher, and then a dental hygienist and her patient dancing to “Baby Shark.” A teen-age girl blew up a bunch of balloons that spelled “ PUSSY ” to the tune of a jazz song from the beloved soundtrack of the anime series “Cowboy Bebop.” Young white people lip-synched to audio of nonwhite people in ways that ranged from innocently racist to overtly racist. A kid sprayed shaving cream into a Croc and stepped into it so that shaving cream squirted out of the holes in the Croc. In five minutes, the app had sandblasted my cognitive matter with twenty TikToks that had the legibility and logic of a narcoleptic dream.

TikTok is available in a hundred and fifty markets. Its videos are typically built around music, so language tends not to pose a significant barrier, and few of the videos have anything to do with the news, so they don’t easily become dated. The company is reportedly focussing its growth efforts on the U.S., Japan, and India, which is its biggest market—smartphone use in the country has swelled, and TikTok now has two hundred million users there. ByteDance often hacks its way into a market, aggressively courting influencers on other social-media networks and spending huge amounts on advertising, much of which runs on competing platforms. Connie Chan, a general partner at Andreessen Horowitz, told me that investors normally look for “organic growth” in social apps; ByteDance has been innovative, she said, in its ability and willingness to spend its way to big numbers. One former TikTok employee I spoke to was troubled by the company’s methods: “On Instagram, they’d run ads with clickbaity images—an open, gashed wound, or an overtly sexy image of a young teen girl—and it wouldn’t matter if Instagram users flagged the images as long as the ad got a lot of engagement first.”

In April, the Indian government briefly banned new downloads of the app, citing concerns that it was exposing minors to pornography and sexual predation. (At least three people in India have died from injuries sustained while creating TikToks: posing with a pistol, hanging out on train tracks, trying to fit three people on a moving bike.) In court, ByteDance insisted that it was losing five hundred thousand dollars a day from the ban. The company announced plans to hire more local content moderators and to invest a billion dollars in India during the next three years. The ban was lifted, and the company launched a campaign: every day, three randomly selected users who promoted TikTok on other platforms with the hashtag #ReturnOfTikTok would receive the equivalent of fourteen hundred dollars.

TikTok is a social network that has nothing to do with one’s social network. It doesn’t ask you to tell it who you know—in the future according to ByteDance, “large-scale AI models” will determine our “personalized information flows,” as the Web site for the company’s research lab declares. The app provides a “Discover” page, with an index of trending hashtags, and a “For You” feed, which is personalized—if that’s the right word—by a machine-learning system that analyzes each video and tracks user behavior so that it can serve up a continually refined, never-ending stream of TikToks optimized to hold your attention. In the teleology of TikTok, humans were put on Earth to make good content, and “good content” is anything that is shared, replicated, and built upon. In essence, the platform is an enormous meme factory, compressing the world into pellets of virality and dispensing those pellets until you get full or fall asleep.

ByteDance has more than a dozen products, a number of which depend on A.I. recommendation engines. These platforms collect data that the company aggregates and uses to refine its algorithms, which the company then uses to refine its platforms; rinse, repeat. This feedback loop, called the “virtuous cycle of A.I.,” is what each TikTok user experiences in miniature. The company would not comment on the details of its recommendation algorithm, but ByteDance has touted its research into computer vision, a process that involves extracting and classifying visual information; on the Web site of its research lab, the company lists “short video recommendation system” among the applications of the computer-vision technology that it’s developing. Although TikTok’s algorithm likely relies in part, as other systems do, on user history and video-engagement patterns, the app seems remarkably attuned to a person’s unarticulated interests. Some social algorithms are like bossy waiters: they solicit your preferences and then recommend a menu. TikTok orders you dinner by watching you look at food.

After I had watched TikTok on and off for a couple of days, the racist lip-synchs disappeared from my feed. I started to see a lot of videos of fat dogs, teen-agers playing pranks on their teachers, retail workers making lemonade from the lemons of being bored and underpaid. I still sometimes saw things I didn’t like: people in horror masks popping into the frame, or fourteen-year-old girls trying to be sexy, or rich kids showing off the McMansions where they lived. But I often found myself barking with laughter, in thrall to the unhinged cadences of the app. The over-all effect called to mind both silent-movie slapstick and the sort of exaggerated, knowing stupidity one finds on the popular Netflix sketch show “I Think You Should Leave.” Some videos displayed new forms of digital artistry: a Polish teen-ager with braces and slate-blue eyes, who goes by @jeleniewska, makes videos in which she appears to be popping in and out of mirrors, phones, and picture frames. Others drew on surprising sources: an audio clip from Cecelia Condit’s art piece “ Possibly in Michigan ,” from 1983, went viral under the track label “oh no no no no no no no no silly” after a sixteen-year-old found the film on a list of “creepy videos” that had been posted on YouTube.

I found it both freeing and disturbing to spend time on a platform that didn’t ask me to pretend that I was on the Internet for a good reason. I was not giving TikTok my attention because I wanted to keep up with the news, or because I was trying to soothe and irritate myself by looking at photos of my friends on vacation. I was giving TikTok my attention because it was serving me what would retain my attention, and it could do that because it had been designed to perform algorithmic pyrotechnics that were capable of making a half hour pass before I remembered to look away.

We have been inadvertently preparing for this experience for years. On YouTube and Twitter and Instagram, recommendation algorithms have been making us feel individually catered to while bending our selfhood into profitable shapes. TikTok favors whatever will hold people’s eyeballs, and it provides the incentives and the tools for people to copy that content with ease. The platform then adjusts its predilections based on the closed loop of data that it has created. This pattern seems relatively trivial when the underlying material concerns shaving cream and Crocs, but it could determine much of our cultural future. The algorithm gives us whatever pleases us, and we, in turn, give the algorithm whatever pleases it. As the circle tightens, we become less and less able to separate algorithmic interests from our own.

One of TikTok’s early competitors was Musical.ly, a lip-synching app based in Shanghai that had a large music library and had become extremely popular with American children. In 2016, an executive at an ad agency focussed on social media told the Times that Musical.ly was “ the youngest social network we’ve ever seen ,” adding, “You’re talking about first, second, third grade.” ByteDance bought Musical.ly the following year, for an amount reportedly in the vicinity of a billion dollars, and merged the app with TikTok in August, 2018. In February, the Federal Trade Commission levied a $5.7-million fine against the company: the agency found that a large percentage of Musical.ly users, who were now TikTok users, were under the age of thirteen, and the app did not ask for their ages or seek parental consent, as is required by federal law. The F.T.C. “uncovered disturbing practices, including collecting and exposing the location” of these children, according to an agency statement. TikTok handled this in a blunt, makeshift fashion: it added an age gate that asked for your birthday but which defaulted to the current date, meaning that users who failed to enter their age were instantly kicked off the app, and their videos were deleted. TikTok did not seem terribly worried about the complaints that followed these deletions. It was now big enough not to care.

A few months after TikTok arrived in the U.S., a nineteen-year-old rapper and singer from Georgia named Montero Lamar Hill uploaded a song that he had been trying for weeks to promote as the basis of a meme. Hill, who goes by the stage name Lil Nas X, had spent much of his teens attempting to go viral on Twitter and elsewhere. There is a sweetness to his self-presentation, which seems optimized for digital interaction; he wears ten-gallon hats and fringe and glitter, a laugh-crying-cowboy emoji come to life. “The Internet is basically, like, my parents in a way,” he told the Times this spring, after people began making videos featuring a snippet of his song “Old Town Road,” in which they would drink “yee yee juice” and turn into cowboys and cowgirls. The song went to No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in April, and stayed there longer than any song ever had.

Certain musical elements serve as TikTok catnip: bass-heavy transitions that can be used as punch lines; rap songs that are easy to lip-synch or include a narrative-friendly call and response. A twenty-six-year-old Australian producer named Adam Friedman, half of the duo Cookie Cutters, told me that he was now concentrating on lyrics that you could act out with your hands. “I write hooks, and I try it in the mirror—how many hand movements can I fit into fifteen seconds?” he said. “You know, goodbye, call me back, peace out, F you.”

TikTok employs an artist-relations team that contacts musicians whose songs are going viral and coaches them on how to use the platform. Some videos include links to Apple Music, which pays artists per stream, though not very much. Virality can thus pay off elsewhere, relieving the pressure for TikTok to compensate artists directly. It is, these days, a standard arrangement: you will be “paid” in exposure, giving your labor to a social platform in part because a lot of other people are doing it and in part because you might be one of the people whom the platform sends, however briefly, to the top.

If you are one of those people, TikTok can be a godsend. Sub Urban, a nineteen-year-old artist from New Jersey, got a deal with Warner Records after millions of TikTokers started doing a dance from the video game Fortnite to his song “Cradles.” In August, a twenty-one-year-old rapper from Sacramento who goes by the name Stunna Girl learned that a song of hers had gone viral on the app, and soon signed a record deal with Capitol. TikTok also offers artists the uniquely moving experience of watching total strangers freely and enthusiastically produce music videos for them. Jonathan Visger, an electronic artist known as Absofacto, told me that it had changed his entire outlook on his career to see nearly two million TikToks all set to his 2015 single “Dissolve,” a heady pop song that inspired a meme in which people appeared to be falling through a series of portals.

“I think the song worked well for the platform because the lyrics are ‘I just wanted you to watch me dissolve, slowly, in a pool full of your love,’ ” Visger told me recently. “Which is a lot like ‘I’m on the Internet, I want to be seen, and I want you to like it.’ ” I asked him if he’d been thinking about the Internet when he was writing it. “No!” he said, laughing. “I was thinking about unrequited love.”

ByteDance is developing a music-streaming service—which will likely launch first in emerging markets, such as India—and it is currently negotiating the renewal of old Musical.ly licensing agreements with the three companies that control roughly eighty per cent of music globally. ByteDance also has acquired a London-based startup called Jukedeck, which has been developing A.I. music-creation tools, including a program that can interpret video and compose music that suits it. Incorporating such technology into TikTok could give ByteDance total ownership of content created within the app. Multiple people at TikTok and ByteDance told me that they were not aware of any plans to add this sort of tool, but TikTok’s plans have a way of abruptly changing.

In some respects, what’s sonically valuable on TikTok isn’t any different from what has long succeeded on radio; no pop-songwriting practice is more established than crafting a good hook. But the app could begin to influence composition in other ways. Digital platforms and digital attention spans may make hit songs shorter, for instance. (“Old Town Road” clocks in at under two minutes.) Adam Friedman has begun producing music directly for influencers, and engineering it for maximum TikTok success. “We start with the snippet, and if it does well on TikTok we’ll produce the full song,” he told me. I suggested that some people might think there was a kind of artistic integrity missing from this process. “The influencer is playing a central role in our culture, and it’s not new,” he said. “There’ve always been socialites, people of influence, the Paris World’s Fair. Whatever mecca that people go to for culture is where they go to for culture, and in this moment it’s TikTok.”

TikTok’s U.S. operations are currently based at a co-working space in a generic four-story building on a busy thoroughfare in Culver City, in Los Angeles. I visited the office twice this summer, after an extensive e-mail correspondence with a company spokesperson. The first person TikTok offered for an on-the-record chat was a twenty-year-old TikToker named Ben De Almeida, who lives in Alberta and, on the app, goes by @benoftheweek. De Almeida first went viral on TikTok with a video that noted his resemblance to the actor Noah Centineo, best known for his roles on “The Fosters” and in teen movies on Netflix. De Almeida wore red striped pants and a yellow shirt and was accompanied by a handler; he radiated good-natured charisma. When I extended my hand, he immediately went in for a hug. “I’m excited to share what it’s like to be a TikToker,” he said.

De Almeida was in L.A. for the summer, “collabing,” he told me. He said that he’d “always wanted to be a creator,” using the term that has become a catchall identity for people who make money by producing content for social platforms. He’d grown up admiring YouTubers, “people like Shane Dawson and iJustine,” and had begun making online videos when he was twelve. He used to post videos on Snapchat, but he got on TikTok in November and now has two million followers. In conversation, De Almeida, like other TikTok teens I talked to, mixed the ecstatically strange dialect of people who love memes—a language in which every word sets off a chain of incomprehensible referents—with the sort of anodyne corporate jargon I associate with marketing professionals. “In this generation, you get steeped in the culture of online video,” he said. “You naturally pick up on what can be a trend.” He pulled out his phone and showed me one of his early TikTok hits, in which he pretended to put a can of beans in the microwave and burn his mom’s house down.

Link copied

Later that day, in West Hollywood, at an outpost of Joe & the Juice, I met with Jacob Pace, the ebullient twenty-one-year-old C.E.O. of a content-production company called Flighthouse. Pace wore a charcoal T-shirt and had the erratic energy of a champion sled dog on break. Flighthouse has more than nineteen million followers on TikTok, and its videos reflect an intuitive understanding of its audience: Pikachu in a baseball cap, dancing; a girl eating Flamin’ Hot Cheetos in a bowl full of milk. Pace has fifteen employees working under him to make TikToks, some of which serve as back-end marketing for record labels that have paid Flighthouse to promote particular songs. He was about to travel to New York to present to ad agencies. “What gets me out of bed in the morning is creating and impacting culture,” he said. Figuring out how to make TikToks that people liked and related to was, he said, like “helping to perfect a machine that will one day start running perfectly.”

Many of the people whose professional lives are dependent on or tied to TikTok were eager to talk to me, but that eagerness was not shared by people who actually work for the company. A former TikTok employee told me, in a direct message, “As strategic as it appears from the outside it’s a complete chaos on the inside.” After my first visit to the L.A. office, I sent a TikTok representative a list of questions asking for basic information, including the number of employees at the company, the number of moderators, the demographics of its users, and the number of hours of video uploaded to the platform daily. The representative informed me, weeks later, that there were “a couple hundred people working on TikTok in the US” and “thousands of moderators” across all of TikTok’s markets, and she said that she couldn’t answer any of the other questions.

TikTok’s primary selling point is that it feels unusually fun, like it’s the last sunny corner on the Internet. I asked multiple TikTok employees whether the company did anything to insure that this mood prevailed in the videos that the app served its users. Speaking with an executive, in August, about the app’s “Discover” page, I asked, “What if the most trending thing was something that you didn’t want to be the most trending thing? Would you put something else in its place?” The executive said that doing so would run counter to TikTok’s ethos. A few weeks later, the online trade magazine Digiday reported that TikTok had begun sending select media companies a weekly newsletter that previewed “ the trending hashtags that the platform plans to promote .” A copy of the newsletter that I obtained lists such hashtags as #BeachDay and #AlwaysHustling, and it instructs, “If you’re interested in participating, make sure to upload your video no earlier than one day before the hashtag launch.” Later, a representative told me that the company might choose not to include certain hashtags on the “Discover” page, and that TikTok was interested in highlighting positive trends, like #TikTokDogs.

TikTok employees in Los Angeles declined to talk in any detail about their relationship to ByteDance headquarters, in Beijing, and everyone I spoke to emphasized that the U.S. operation was fairly independent. But one former employee, who left the company in 2018, described this as a “total fabrication.” (A ByteDance spokesperson, in response, said that the markets were becoming more independent and that much of that process had happened within the past year.) TikTok’s technology was developed in China, and it is refined in China. Another ex-employee, who had worked in the Shanghai office, said that nearly all product features are shipped out from Shanghai and Beijing, where most of ByteDance’s engineers are based. “At a tech company, where the engineers are is what matters,” the writer and former Facebook product manager Antonio Garcia-Martinez told me. “Everyone else is a puppet paid to lie to you.”

The direct predecessor of TikTok is Douyin, a short-video platform that ByteDance launched in China in 2016. Douyin is headquartered in Shanghai, and ByteDance says that it has more than five hundred million monthly active users. Zhou Rongrong, a twenty-nine-year-old Ph.D. candidate at the Central Academy of Fine Arts, in Beijing, who has studied Internet art in China, said that most young people in the country are on Douyin. In particular, she said, the app has opened up new kinds of economic potential for people outside the country’s traditional centers of power. “For example, I had no way before to see these ways that rural people can cook their dishes,” Zhou said. Douyin has given rise to influencers like Yeshi Xiaoge—the name means “brother who cooks in the wilderness”—who films himself preparing elaborate meals, and who has released his own line of beef sauce. Rural administrations have begun advertising their regions’ produce and tourist attractions on the app.

Though it remains broadly similar to TikTok, Douyin has become more advanced than its global counterpart, particularly with respect to e-commerce. With three taps on Douyin, you can buy a product featured in a video; you can book a stay at a hotel after watching a video shot there; you can take virtual tours of a city’s stores and restaurants, get coupons for those establishments, and later post geo-tagged video reviews. Fabian Bern, the head of a marketing company that works closely with Douyin influencers, told me that some power users can make “fifteen to twenty thousand U.S. dollars” on a shopping holiday like Singles’ Day.

So far, TikTok has concentrated more on expanding its user base than on offering opportunities for e-commerce. If TikTok wants to keep growing, it will need to attract more people who are no longer in their teens, and it will need to hold their attention. Many people are not terribly interested in even the choicest memes the world has to offer; in August, the Verge reported that a “significant majority” of new TikTok users give up on the app after thirty days. Bern thinks that TikTok content will soon become more mature, as has already happened with Douyin, which now contains micro-vlogs, life-style content, business advice, and videos from local police. Selected users on Douyin can upload videos as long as five minutes. Fictional mini-dramas have begun to appear.

“This meme content, people will get bored with it,” Bern said. “And companies are, like, ‘We cannot make this type of content or we’ll damage our brands.’ ”

ByteDance’s founder, Zhang Yiming, was twenty-nine when he started the company, in 2012. Zhang, who rarely gives interviews, was raised in Fujian Province, the son of a civil servant and a nurse, and attended university in the northern port city of Tianjin. He briefly worked at Microsoft in China, and bounced between startups for a while. He then pitched Chinese investors on the idea of a news-aggregation app that would use machine learning to provide people with whatever they wished to read. The app, called Jinri Toutiao, was launched within the year. Its name means “today’s top headlines.” It’s a bit like Reddit, if Reddit were guided by A.I. rather than by the upvotes and downvotes of its readers.

Like TikTok, Toutiao starts feeding you content as soon as you open it, and it adjusts the mix by tracking and analyzing your scrolling behavior, the time of day, and your location. It can deduce how its users read while commuting, and what they like to look at before bed. It reportedly has around a hundred and twenty million daily active users, most of whom are under thirty. On average, they read their tailored feeds for more than an hour each day. The app has a reputation for promoting lowbrow clickbait.

In China, daily life has become even more tech-driven than it is in the U.S. People can pay for things by letting cameras scan their faces; last year, a high school in Hangzhou installed scanners that recorded classrooms every thirty seconds and classified students’ facial expressions as neutral, happy, sad, angry, upset, or surprised. The Chinese government has been assembling what it calls the Social Credit System, a network of overlapping assessments of citizen trustworthiness, with opaque calculations that integrate information from public records and private databases. The government has also set benchmarks for progress in artificial-intelligence development at five-year intervals. Last year, Tianjin announced plans to put sixteen billion dollars toward A.I. funding; Shanghai announced a plan to raise fifteen billion.

There are two principal approaches to artificial intelligence. In symbolic A.I., humans give computers a set of elaborate rules that guide them through a task. This works well for things like chess, but everyday tasks—identifying faces, interpreting language—tend to be governed by human instinct as much as by rules. And so another approach, known as neural networks, or machine learning, has predominated in the past two decades or so. Under this model, computers learn by recognizing patterns in data and continually adjusting until the desired output—a correctly labelled face, a properly translated phrase—is consistently achieved. In this sort of system, the quantity of data is, broadly speaking, more important than the sophistication of the program interpreting it. The sheer number of users that Chinese companies have, and the types of data that come from the integration of tech with daily life, give those companies a crucial advantage.

Chinese tech companies are often partly funded by the government, and they openly defer to its requests, turning over user messages and purchase data, for instance. Tencent, which owns WeChat, has a “Follow Our Party” sign on a statue in front of its headquarters. The Wall Street Journal has reported that a ByteDance office in Beijing includes a room for a cybersecurity team of the Chinese police, which the company informs when it “ finds criminal content like terrorism or pedophilia ” on its apps. Last year, ByteDance was ordered to suspend Toutiao and to shut down a meme-centric social app called Neihan Duanzi—the name means something like “implied jokes”—because the content had become too vulgar, too disorderly, for the state. Zhang issued an apology, written in the language of government control. ByteDance had allowed content to appear that was “incommensurate with socialist core values, that did not properly implement public opinion guidance,” he said.

Three days later, the Times reported that the Chinese government had deployed facial-recognition technology to identify Uighurs, a Muslim minority in the country, through its nationwide network of surveillance cameras. China has imprisoned more than a million Uighurs in reëducation camps, in Xinjiang, and has subjected them to a surge in arrests, trials, and prison sentences. In August, I asked a ByteDance spokesperson about the fear that the massive trove of facial closeups accumulated on its various products could be misused. Even if people trusted ByteDance not to do anything sinister, I said, what if a third party got hold of the company’s data? The spokesperson told me that the data of American users was stored in-country—TikTok’s data is now kept in the U.S. and Singapore, the rep said—and noted, nonchalantly, that people made their faces available to other platforms, too. Of course, U.S. tech companies often don’t seem answerable enough to the government—or, rather, to the public. The American system has its own weaknesses.