July 26, 2011

The Science Behind Dreaming

New research sheds light on how and why we remember dreams--and what purpose they are likely to serve

By Sander van der Linden

Getty Images

For centuries people have pondered the meaning of dreams. Early civilizations thought of dreams as a medium between our earthly world and that of the gods. In fact, the Greeks and Romans were convinced that dreams had certain prophetic powers. While there has always been a great interest in the interpretation of human dreams, it wasn’t until the end of the nineteenth century that Sigmund Freud and Carl Jung put forth some of the most widely-known modern theories of dreaming. Freud’s theory centred around the notion of repressed longing -- the idea that dreaming allows us to sort through unresolved, repressed wishes. Carl Jung (who studied under Freud) also believed that dreams had psychological importance, but proposed different theories about their meaning.

Since then, technological advancements have allowed for the development of other theories. One prominent neurobiological theory of dreaming is the “activation-synthesis hypothesis,” which states that dreams don’t actually mean anything: they are merely electrical brain impulses that pull random thoughts and imagery from our memories. Humans, the theory goes, construct dream stories after they wake up, in a natural attempt to make sense of it all. Yet, given the vast documentation of realistic aspects to human dreaming as well as indirect experimental evidence that other mammals such as cats also dream, evolutionary psychologists have theorized that dreaming really does serve a purpose. In particular, the “threat simulation theory” suggests that dreaming should be seen as an ancient biological defence mechanism that provided an evolutionary advantage because of its capacity to repeatedly simulate potential threatening events – enhancing the neuro-cognitive mechanisms required for efficient threat perception and avoidance.

So, over the years, numerous theories have been put forth in an attempt to illuminate the mystery behind human dreams, but, until recently, strong tangible evidence has remained largely elusive.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

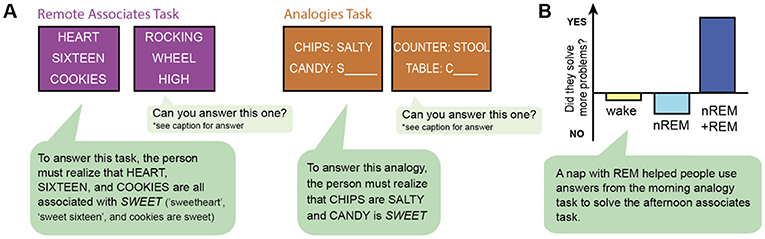

Yet, new research published in the Journal of Neuroscience provides compelling insights into the mechanisms that underlie dreaming and the strong relationship our dreams have with our memories. Cristina Marzano and her colleagues at the University of Rome have succeeded, for the first time, in explaining how humans remember their dreams. The scientists predicted the likelihood of successful dream recall based on a signature pattern of brain waves. In order to do this, the Italian research team invited 65 students to spend two consecutive nights in their research laboratory.

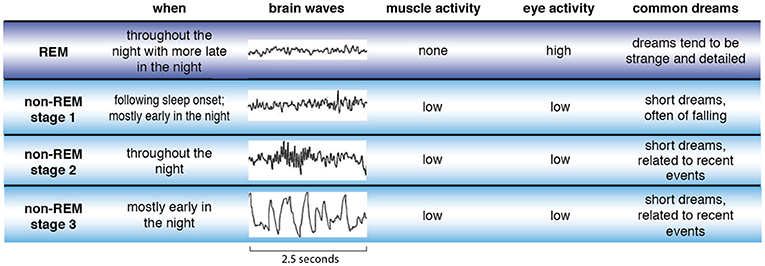

During the first night, the students were left to sleep, allowing them to get used to the sound-proofed and temperature-controlled rooms. During the second night the researchers measured the student’s brain waves while they slept. Our brain experiences four types of electrical brain waves: “delta,” “theta,” “alpha,” and “beta.” Each represents a different speed of oscillating electrical voltages and together they form the electroencephalography (EEG). The Italian research team used this technology to measure the participant’s brain waves during various sleep-stages. (There are five stages of sleep; most dreaming and our most intense dreams occur during the REM stage.) The students were woken at various times and asked to fill out a diary detailing whether or not they dreamt, how often they dreamt and whether they could remember the content of their dreams.

While previous studies have already indicated that people are more likely to remember their dreams when woken directly after REM sleep, the current study explains why. Those participants who exhibited more low frequency theta waves in the frontal lobes were also more likely to remember their dreams.

This finding is interesting because the increased frontal theta activity the researchers observed looks just like the successful encoding and retrieval of autobiographical memories seen while we are awake. That is, it is the same electrical oscillations in the frontal cortex that make the recollection of episodic memories (e.g., things that happened to you) possible. Thus, these findings suggest that the neurophysiological mechanisms that we employ while dreaming (and recalling dreams) are the same as when we construct and retrieve memories while we are awake.

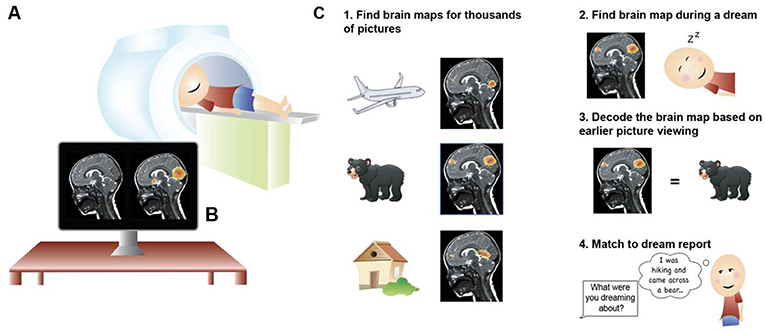

In another recent study conducted by the same research team, the authors used the latest MRI techniques to investigate the relation between dreaming and the role of deep-brain structures. In their study, the researchers found that vivid, bizarre and emotionally intense dreams (the dreams that people usually remember) are linked to parts of the amygdala and hippocampus. While the amygdala plays a primary role in the processing and memory of emotional reactions, the hippocampus has been implicated in important memory functions, such as the consolidation of information from short-term to long-term memory.

The proposed link between our dreams and emotions is also highlighted in another recent study published by Matthew Walker and colleagues at the Sleep and Neuroimaging Lab at UC Berkeley, who found that a reduction in REM sleep (or less “dreaming”) influences our ability to understand complex emotions in daily life – an essential feature of human social functioning. Scientists have also recently identified where dreaming is likely to occur in the brain. A very rare clinical condition known as “Charcot-Wilbrand Syndrome” has been known to cause (among other neurological symptoms) loss of the ability to dream. However, it was not until a few years ago that a patient reported to have lost her ability to dream while having virtually no other permanent neurological symptoms. The patient suffered a lesion in a part of the brain known as the right inferior lingual gyrus (located in the visual cortex). Thus, we know that dreams are generated in, or transmitted through this particular area of the brain, which is associated with visual processing, emotion and visual memories.

Taken together, these recent findings tell an important story about the underlying mechanism and possible purpose of dreaming.

Dreams seem to help us process emotions by encoding and constructing memories of them. What we see and experience in our dreams might not necessarily be real, but the emotions attached to these experiences certainly are. Our dream stories essentially try to strip the emotion out of a certain experience by creating a memory of it. This way, the emotion itself is no longer active. This mechanism fulfils an important role because when we don’t process our emotions, especially negative ones, this increases personal worry and anxiety. In fact, severe REM sleep-deprivation is increasingly correlated to the development of mental disorders. In short, dreams help regulate traffic on that fragile bridge which connects our experiences with our emotions and memories.

Are you a scientist who specializes in neuroscience, cognitive science, or psychology? And have you read a recent peer-reviewed paper that you would like to write about? Please send suggestions to Mind Matters editor Gareth Cook, a Pulitzer prize-winning journalist at the Boston Globe. He can be reached at garethideas AT gmail.com or Twitter @garethideas .

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Open access

- Published: 14 October 2019

Predicting the affective tone of everyday dreams: A prospective study of state and trait variables

- Eugénie Samson-Daoust 1 ,

- Sarah-Hélène Julien 1 ,

- Dominic Beaulieu-Prévost ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7926-5295 2 &

- Antonio Zadra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3671-7081 1 , 3

Scientific Reports volume 9 , Article number: 14780 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

3924 Accesses

10 Citations

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

Although emotions are reported in a large majority of dreams, little is known about the factors that account for night-to-night and person-to-person variations in people’s experience of dream affect. We investigated the relationship between waking trait and state variables and dream affect by testing multilevel models intended to predict the affective valence of people’s everyday dreams. Participants from the general population completed measures of personality and trauma history followed by a three-week daily journal in which they noted dream recall, valence of dreamed emotions and level of perceived stress for the day as well as prior to sleep onset. Within-subject effects accounted for most of the explained variance in the reported valence of dream affect. Trait anxiety was the only variable that significantly predicted dream emotional valence at the between-subjects level. In addition to highlighting the need for more fine-grained measures in this area of research, our results point to methodological limitations and biases associated with retrospective estimates of general dream affect and bring into focus state variables that may best explain observed within-subject variance in emotions experienced in everyday dreams.

Similar content being viewed by others

Evidence of an active role of dreaming in emotional memory processing shows that we dream to forget

Dreams share phenomenological similarities with task-unrelated thoughts and relate to variation in trait rumination and COVID-19 concern

Emotion dysregulation mediates the relationship between nightmares and psychotic experiences: results from a student population

Introduction.

Despite decades of advances in dream research, relatively little is known about how dreams are formed and what factors predict their content and emotional tone. One of the most widely studied models of dream content is the continuity hypothesis of dreaming 1 , 2 which posits that dreams are generally continuous with the dreamer’s current thoughts, concerns and salient experiences. In line with this conceptualization of dreams, a large proportion of dream research 1 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 has been dedicated to quantifying various dimensions of people’s dream reports and investigating their relationship to different aspects of people’s waking life. While much of this work has helped refine our understanding of which aspects of waking life (e.g., day-to-day actions, ongoing concerns, learning tasks, stressful experiences, psychological well-being) are most likely to be reflected or embodied in various facets of people’s dreams (e.g., settings, interpersonal interactions, activities, thematic contents), attempts to identify factors accounting for night-to-night or person-to-person variations in the intensity and valence of dream affect have yielded mixed results 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 .

Given that emotions are present in a vast majority of home and laboratory dream reports 7 , 14 , 15 , 16 , 17 and that some theorists 18 , 19 , 20 believe that affect plays a key role in structuring dream content, elucidating why people experience negatively toned dreams on some nights and positively toned dreams on others is of prime importance. Among the most studied factors hypothesised to influence dream valence are stress 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 , trait or personality characteristics 25 , 26 , 27 , history of traumatic experiences 28 , 29 , 30 , 31 , and psychological well-being 7 , 18 , 32 , 33 . Relatedly, one neurocognitive model 34 , 35 of dysphoric and everyday dream production suggests that variations in the frequency and intensity of negative dream emotions are partially determined by affect load , or day-to-day variations in emotional stress, and that the relation between dream content and stress varies as a function of affect distress , or the disposition to experience events with distressing, reactive emotions.

Many of the factors believed to predict the experience of negative dreams, including trauma history and psychopathology, have been associated with disturbed dreaming 28 , 36 , 37 , 38 and likely contribute to the development and heightening of affect distress 34 , 39 . Similarly, other dispositional traits related to the concept of affect distress, such as boundary thinness 40 (used to describe particularly sensitive and vulnerable individuals prone to mixing thoughts, images and feelings) and trait anxiety 41 (stable individual differences in the tendency to experience anxiety across situations) are also correlated with indices of negative dream content, including frequency of bad dreams and nightmares 27 , 33 , 42 , 43 , 44 , 45 . Thus, affect distress may be viewed as encompassing a range of factors known to impact dream affect, including trauma history, psychopathology, trait anxiety, and boundary thinness.

While several studies have investigated the differential impact of state and trait factors on dream content 7 , 11 , 12 , 32 , 42 , 46 , 47 , 48 , 49 , 50 , most have focused solely on nightmares, have been purely retrospective in nature, or did not weigh state-related findings against trait factors such as personality or psychopathology. Only two studies 42 , 48 have ever used a prospective design to assess the effect of trait and daily state measures on everyday dreams. The first one 42 assessed state anxiety and depression (what the authors termed “mood”) in relation to trait measures believed to underlie nightmare occurrence. They found statistically significant correlations between their state and trait variables and nightmare frequency, but only in individuals with thin psychological boundaries. The second study 48 obtained similar results in that daily stress was found to statistically predict general sleep-related experiences—a concept elaborated by Watson 51 to describe nocturnal phenomena such as nightmares, falling dreams, flying dreams and sleep paralysis—but only in young adults scoring high on a measure of trait dissociation (the tendency to experience psychological detachment from reality).

In sum, in addition to giving rise to inconsistent results, research on the determinants of dream affect has been limited by the often retrospective nature of the study design, single measurement points, focus on nightmare incidence or broad sleep-related experiences, and a failure to evaluate the interactive role of state and trait factors within a larger conceptual framework. We therefore used a prospective, multilevel design to investigate the interplay between daily fluctuations in perceived levels of stress and trait indices of affect distress as determinants of dream affect. Individuals from the general population first completed questionnaire measures of sleep and dream experiences, trait anxiety, boundary thinness, trauma history, and PTSD symptoms, followed by at least three consecutive weeks of daily assessments of perceived stress as well as dream recall, including the emotional valence associated with each remembered dream. Since daily measures ( N = 2538) were nested within individuals ( N = 128), multilevel hierarchical linear modelling (HLM) analyses were performed in order to examine the distinctive effect of state and trait variables.

Descriptive statistics and intercorrelations of tested variables

Table 1 presents the means, standard deviations and zero-order Pearson correlations between study variables. Daily measures were averaged per participant over the study’s duration to investigate their association to trait variables. All observed correlations were in the expected direction. The highest obtained correlation ( r = 0.752) was between the mean daily level of maximum stress and the mean level of stress prior to bedtime. The fact that daily maximum stress was more strongly correlated with daily dream valence ( r = 0.300) than was daily stress prior to bedtime ( r = 0.185) suggests that the two variables tapped into different facets of perceived stress. As can be seen in the table, trait anxiety was statistically correlated with a majority of other studied variables, while sex did not show statistically significant correlations with any of the other measures.

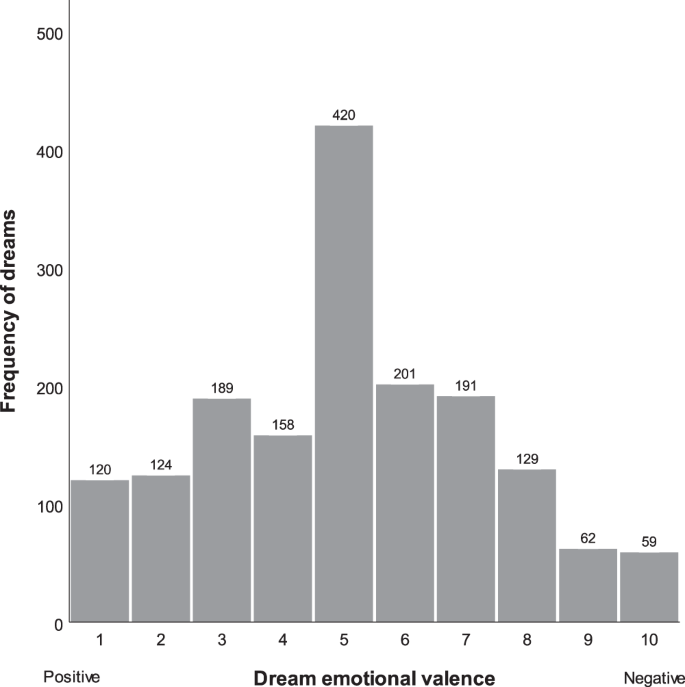

Multilevel models predicting dream valence as outcome

A total of 1700 nights led to a dream recall in participants over the study’s three-week duration, of which 1653 (97.2%) contained ratings on the dream’s emotional valence. Of the 1700 nights, 773 (45.5%) yielded more than one recalled dream and participants reported an average of 6.9 dreams per week. Figure 1 presents the distribution of dream valence ratings for the 1653 dream reports. The mean dream valence score was 5.08 ( SD = 2.27), or at the midpoint of the positive to negative rating scale. As can also be seen in the figure, highly positive dreams (scores of 1 or 2) were approximately twice as frequent as highly negative ones (scores of 9 or 10).

Distribution of dream emotional valence for 1653 dream reports.

Table 2 presents the intercepts-only model (i.e., unconditional model) for daily measures of dream valence. The intraclass correlation was 0.161, indicating that 16.1% of the variance in dream valence occurred between subjects, while 83.9% of the variance occurred within subjects (i.e., across days).

Table 3 presents the multilevel model predicting dream valence using trait (Level-2) and state (Level-1) predictors. At Level-2, when all predictors were entered in the model as fixed terms, trait anxiety (STAI-T) was the only variable to statistically predict dream valence. At Level-1, neither of the two daily measures of perceived stress statistically predicted the dream valence experienced on the subsequent night. Dream recall frequency per night was the only statistically significant Level-1 predictor. This measure was used as a control variable since dream valence was only provided for the best remembered dream on a given night when more than one dream was recalled (45.5% had multiple recalls) and thus the two variables were not entirely independent.

When standardized scores for trait anxiety (ZSTAI-T) were entered as a single predictor of dream valence in a separate model, it was found to be an even better predictor ( p < 0.001) than when it was considered alongside other predictor variables, with each increase in standard deviation STAI-T scores explaining a 0.33 unit increase in dream valence ratings. This model reduced the unexplained between-subject variance by 11.6%, thus explaining a total of 1.9% of the variance in dream valence ratings obtained over the study’s 3-week duration.

Post Hoc multilevel models predicting dream valence as an outcome variable

Since interactions between predictors could potentially explain why neither of our perceived stress variables predicted dream valence 42 , 48 , we tested for possible interactions, particularly between trait variables (Level-2) and daily perceived stress (Level-1), but did not find a statistically significant interaction that could predict dream valence. The only statistically significant interaction predicting dream valence was between trait anxiety (STAI-T) scores and dream recall frequency ( p = 0.007), which was positive and expected since the dream valence rating of the most vivid or best-remembered dream on a given night can increase when a greater number of dreams is recalled on that night.

Since daily perceived stress did not predict the dream valence experienced on the subsequent night, models testing for potential a dream-lag effect (i.e., increased incorporation in dreams of events having occurred 5–7 days prior to the dream) 52 , 53 were also computed post hoc. Separate datasets pairing daily perceived stress levels from previous days (i.e., two to seven days prior to recalled dreams) with reported valence of subsequently recalled dream were generated. No statistically significant effect of perceived stress from the past 2 to 7 days on dream valence was found in any of the datasets tested, thus refuting a possible delayed effect of perceived stress on subsequently experienced dream affect.

Additional multilevel models predicting perceived stress as outcome

Using a reversed model, we aimed to predict daily stress scores (both maximum and prior to bedtime) using dream valence and DRF from the preceding night, along with the other predictor variables. The models only yielded a statistically significant effect of trait anxiety as a predictor of both maximum ( p = 0.031) and bedtime stress levels ( p = 0.007) (see Supplementary Tables S1 and S2 for more details).

We investigated the relationship between waking trait and state variables and dream affect by testing multilevel models aiming to predict the affective valence of people’s everyday dreams. Moreover, this was the first time a prospective day-by-day design was used to test predictors of dream valence at the between-subject as well as within-subject levels of variance. The results showed that daily measures of perceived stress collected from a non-clinical sample of adults do not, as suggested by some theorists, predict the emotional valence of dreams experienced later that night, nor on immediately subsequent nights. This study is also the first to identify trait anxiety as a key dispositional variable in predicting dream valence, even when trait measures are weighed against state variables.

Taken as a whole, these results run counter to previous findings indicating that state variables are better predictors of dysphoric dream frequency than are dispositional traits 46 , 47 , and that daily stress or mood interacts with trait variables to predict nightmares 42 , 48 . Previous positive results could be due to methodological considerations as these studies either lacked a multilevel, prospective design, focused on nightmare occurrence 42 , 46 , 47 or general sleep-related experiences 48 instead of everyday dreams, or focused on undergraduate (often psychology) students instead of recruiting participants from the general adult population 46 , 47 , 48 .

Our results are reminiscent of Cellucci and Lawrence’s study 49 of nightmare sufferers showing that daily ratings of general and maximum anxiety were statistically correlated with nightmare frequency and intensity in only a small minority of participants. Since trait variables were not assessed in their study, why nightmare occurrence was related to daily anxiety in some participants but not others remains to be determined. In line with this question, Soffer-Dudek and Shahar 48 found that daily stress predicted “general sleep-related experiences” only in individuals scoring high in trait dissociation (a trait strongly correlated with boundary thinness), while Blagrove and Fisher 42 found that correlations between state anxiety and nightly incidence of nightmares were only statistically significant in participants scoring high on boundary thinness. While the interplay between dispositional and state factors underlying nightmare occurrence may play a role in the emotional tone of everyday dreams, the current study showed no statistical interactions between various trait variables and daily levels of perceived stress in predicting dream valence.

With respect to the other dispositional traits investigated, it is noteworthy that although traumatic experiences, including aversive events during one’s childhood, are well-documented correlates of disturbed dreaming 21 , 34 , 54 , 55 , 56 , we found no statistically significant effect of trauma history on everyday dream affect. Most findings linking trauma and dream content, however, have come from work focused on trauma-related nightmares, typically in patients diagnosed with PTSD. By contrast, only 23 (18%) of our participants had a cut-off score of 3 or greater on the PC-PTSD (indicative of ongoing trauma-related difficulties) and only 16% reported more than one dream with an affect score of 9 or 10 (indicative of a nightmare) during the three weeks of the study. In fact, as shown in Fig. 1 , dreams with highly intense negative affect represented less than 8% of the over 1600 dream reports collected in the current study.

Similarly, while boundary thinness has been linked to dream content variables such as high dream recall, frequent nightmares and negatively-toned dreams 26 , 43 , 57 , 58 , 59 , it had no predictive value in our models of everyday dream valence. This trait variable may be better suited to the study of nightmare sufferers, a population specifically investigated by Hartmann et al . 59 when developing this personality construct, or to individuals prone to particularly vivid or bizarre dreams 26 .

Turning to the construct of affect load, the current study did not find evidence to support the idea that daily variations in perceived stress are temporally related night-to-night variations in dream affect. It should be noted that studies having reported an effect of affect load on the emotional content of dreams did so by measuring affect load retrospectively (e.g., for the past month) at a single point in time 7 , 46 , 47 rather than on a day-to-day basis. This underscores the importance of how state factors are assessed since correlates of retrospectively estimated state variables can be biased by dispositional factors (e.g., personality) and are not necessary correlates of prospective, day-to-day measurements of these constructs. In fact, this is not the first time in dream research that prospective study designs have yielded findings contradicting results obtained with retrospective measurements of dream-related variables, including correlates of dream recall and dream content 60 , 61 , 62 .

The concept of affect load may also need to be better defined to allow for more directly comparable study results. For example, in exploring the effects of stress on dreams, researchers have investigated acute stressors 63 , 64 , experimental stressors 22 , 65 , emotional stressors 66 , as well as cumulative stressors 21 . Additionally, in light of the recently proposed social simulation theory of dream function 67 in which dreaming is conceptualized as simulating social skills and bonds to strengthen waking social relationships, the study of social or interpersonal stressors 68 in relation to dream content may be particularly valuable, especially since a vast majority of dream reports feature social interactions 5 , 15 , 69 and that concerns of an interpersonal nature are frequent in everyday dreams 1 , 3 . Moreover, as suggested by some researchers 50 , dream content may be more reactive to the emotional nature of stressors than to the stressors per se . Finally, it is important to note that our participants were not particularly stressed—or at least did not perceive that they were—during the 3-week study as reflected by their mean score of 3.6 (out of 9) on our measure of daily maximum stress and 1.7 (out of 9) for daily bedtime stress. It is possible that direct or interaction effects of state and trait variables on dream affect become heightened, and thus more readily observable, during periods of acute or chronic stress.

When stress or affect load are studied in relation to dream content, they are usually assessed with self-report questionnaires. However, subjective levels of perceived stress can differ from variations or patterns in the biological markers of cortisol 70 , 71 . It is thus possible that physiological modulation of stress response, as opposed to subjective stress perception, plays a role in people’s nightly experience of dream affect. Of note, Nagy et al . 72 found a blunted cortisol awakening response in women reporting frequent nightmares, which was independent of lifestyle, psychiatric symptoms and demographic variables. This led the authors to hypothesize that low cortisol reactivity could be a trait-like feature of nightmare sufferers. Similarly, some researchers 73 have suggested that the gradual rise in people’s cortisol level from the middle of the night until its peak in the morning could account for observed increases in dream emotionality, bizarreness, vividness and length across the night 74 , independently of sleep stage. The use of biomarkers such as cortisol, which can be sampled in saliva 72 , could therefore be of particular interest in investigating the range and intensity of dream emotions reported both within and across nights.

Furthermore, since dream emotional valence was measured for the best-recalled dream upon awakening in the morning, the current study is limited to a narrow portion of participants’ sleep mentation. In addition, given the recency of morning dreams 75 and the aforementioned increase in dreamlike qualities of sleep mentation across the night, dream emotional valence was likely based on dreams occurring moments before morning awakenings. Affect load could thus have been processed through the emotional valence of dreams that were not collected in the present study (i.e., dreams from earlier periods of the night or other forms of unrecalled sleep mentation). Such a hypothesis could be tested with serial laboratory-based awakenings for dream collection across the sleep period, although the proportion of dreams containing emotions as well as their valence tend to differ when they are self-reported in the laboratory 13 , 14 , 17 , 76 as opposed to participants’ natural home enviornment 16 , 77 , 78 , 79 .

Finally, our sample of over 1600 dream reports revealed a roughly equal distribution of positive and negative emotions, as well as a higher proportion of intense positive emotions as opposed to negative emotions. This finding adds to the growing evidence showing that when the presence and valence of dreamed emptions are scored by the participants themselves as opposed to by external judges, as done in early studies of dream content 15 , a considerably higher proportion (70% to 100%) of dream reports are found to contain emotions 16 , 77 , 78 , 79 and that positive dream affect is particularly more frequent than when dream reports are assessed by external raters 17 , 79 . These findings also highlight the interest of investigating positive dimensions of waking states, such as mindfulness 27 and positive emotions 7 in relation to dream affect. In a related vein, the study of how self-regulation techniques such as relaxation and meditation may modulate the impact of state and trait factors on dream content also merits investigation.

In sum, results of the present study showed that trait anxiety, but not day-to-day levels of perceived stress, predicted the affective tone of home dream reports and revealed a potential bias in previous studies associated with the use of one-time retrospective assessments of state variables in predicting night-to-night variations in dream affect. The present results also underscore the need for additional research on factors underlying the valence of emotions experienced in everyday dreams as opposed to focusing solely on nightmares or trauma-related dreams. In particular, the study of different categories of stressors and the use of stress biomarkers could be particularly useful in elucidating the differential impact of state and trait factors on dream content.

Data were collected as part of a larger online study conducted on the Qualtrics Research Suite platform. After providing informed consent, participants were emailed a link giving them access to the study materials. Participants first completed a series of questionnaires on sleep, personality, trait anxiety and trauma history. They then received, over a maximum of four consecutive weeks, daily scheduled notifications to complete a questionnaire on dream recall in the morning as well as an evening questionnaire on the stress and emotions experienced that day. The project was approved by the Arts and Science Research Ethics Committee of the Université de Montréal, Canada (Project no. CERAS-2017-18-013-P) and all research was performed in accordance with their guidelines and regulations.

Participants

One hundred and twenty-eight non-paid participants (98 women, 30 men, M age = 42.55, SD age = 14.63, range = 19–76 years) were recruited from the general adult population between February and July 2018 via ads in free local newspapers (74.9% of sample), social networks (9.4%), email lists (8.6%) and community posters (7.1%). Study materials were available in both French and English to reflect the bilingual nature of Montreal, Canada. One hundred and twelve of the 128 volunteers (87.5%) completed the study in French. Eighty-eight participants (68.8% of sample) were working at the time of study, 20 (15.6%) were students, 12 (9.4%) were retired, 5 (3.9%) were unemployed, and 3 (2.3%) did not specify their occupation. Of the 285 people who initially expressed interest in the study, 151 provided written informed consent and completed the first set of questionnaires. Of these 151 participants, 23 (18 women, 5 men) were excluded for providing fewer than three consecutive days of matching stress and dream valence data. Participants’ morning dream data were paired with their stress ratings completed prior to bedtime the night before. Sixty-six of 128 participants (51.6%) completed one or more days of data collection beyond the 21 consecutive days required. These data were included in the analyses as they contained validly paired evening stress and morning dream valence scores.

Retrospective measures

Participants first completed a general Sleep and Dream Questionnaire 33 used to assess basic sleep, dream and demographic variables.

Boundary thinness

The short form of the Boundary Questionnaire (BQ18) 80 , which contains 18 items derived from the original Boundary Questionnaire 40 , was used to measure boundary thinness or thickness, a personality trait associated with various aspects of dreaming 57 , including high dream recall 43 and nightmare prevalence 58 . People with thin psychological boundaries are typically described as being creative, sensitive, vulnerable and easily mixing thoughts, images and feelings. The total score of the BQ18 consists of a sum of the ratings (ranging from 0 to 4) on the 18 items after inverting the ratings on 4 items. Scores on the BQ18 are positively correlated ( r = 0.87, N = 856) with total scores on the original Boundary Questionnaire 80 . Cronbach’s alpha (α) for the BQ18 in the present study was 0.70.

Trait anxiety

The Trait scale of the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory – Form Y (STAI-T) 81 measures anxiety as an enduring personality trait and consists of 20 statements that pertain to how participants “generally feel.” Each item is rated on a 4-point Likert scale. The total score is calculated as a sum of all the ratings (ranging from 0 to 80), with a higher score indicating higher trait anxiety. The STAI-T is widely used and has been translated in multiple languages, including in French Canadian 82 . The latter shows a correlation of r = 0.82 with the original English version and a test-retest correlation of r = 0.94. The original French-Canadian translation shows strong internal consistency (α = 0.91) and an identical reliability (α = 0.91) obtained in the present study.

Youth trauma

A shortened French version 83 of the Early Trauma Inventory Self Report (ETISR-SF) 84 was used to assess a range of physical, emotional, and sexual abuse experiences that may have occurred before the age of 18. The seven items, presented in “Yes-No” format, yield a total score ranging between 0 and 7. Cronbach’s alpha (α) for the ETISR-SF in the present study was 0.73.

Posttraumatic stress disorder

The Primary Care PTSD Screen (PC-PTSD) 85 measures four factors specific to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD): reexperiencing, avoidance, hyperarousal and numbing. A positive response to any of the yes/no items indicates that the responder may have PTSD or trauma-related problems, and a cut-off score of 3 is recommended to detect positive cases. Cronbach’s alpha (α) for the PC-PTSD in the present study was 0.75.

Prospective measures

Dream recall and content were assessed each morning via URL links emailed to each participant at 3:00 AM. To ensure that reported dream recall data was for the targeted day, daily links expired at 6:00 PM. This time range was sufficiently broad to accommodate participants’ occupations and schedules. Reminders were automatically sent out at 3:00 PM if the morning questionnaire had not been completed by that time. Waking perceived stress for the day was measured prior to bedtime with links sent out at 6:00 PM and expiring at 3:00 AM. A reminder was sent at 12:00 AM (i.e. midnight) if participants had not completed the evening questionnaire by that time.

Dream affect and content

Dream recall was assessed with a single item, “Did you dream last night?” and a “Yes-No” answer format. If “No” was selected, participants had the option of returning to the questionnaire if ever they remembered a dream later in the day. If participants answered “Yes,” they were required to indicate if they remembered one, two, or three or more dreams from that night. These values were used to calculate participants’ dream recall frequency. Participants then had to indicate (for the most vivid or best-remembered dream from the night if more than one dream was recalled), the dream’s emotional valence by answering the question, “What was the general emotion of your dream?” using a 10-point Likert scale ranging from positive (1) to negative (10).

Perceived stress

Two daily measures of perceived stress were completed prior to bedtime using a 10-point Likert scale ranging from not stressed at all (0) to extremely stressed (9). The first measure required participants to rate the maximum level of stress experienced that day while the second required participants to rate their stress level at the time of questionnaire completion (i.e., prior to bedtime). These scales, reviewed by Dr. Sonia J. Lupien, director of the Centre for Studies on Human Stress ( https://humanstress.ca/ ), were used instead of more exhaustive instruments such as the Daily Stress Inventory 86 due to the multi-week nature of the study and our desire to limit volunteers’ workload.

Statistical analyses

Data were analyzed using hierarchical linear modeling (HLM) with IBM SPSS Statistics (version 25), where affect load (level 1: affective dream content [outcome], perceived stress [predictor]) was underpinned by the participants’ dispositional measures (level 2 predictors: trait anxiety, boundary thinness, trauma history, PTSD, sex, age). The level of statistical significance for every analysis was set at p = 0.05. This type of multilevel analysis is ideally suited to such a dataset as it a) allows for the analysis of multiple relationships while considering shared variance at both levels, b) takes into account dependency across measurement time points, c) doesn’t require balanced designs in which different individuals have a fixed number of prospective data points without any missing data, and d) has fewer assumptions and is less likely to underestimate error than other statistical methods 87 .

Although dream valence was the main outcome variable of interest, models predicting daily perceived stress were also tested to investigate possible effects of dreamed emotions on daytime stress. Dream valence had a normal distribution and enough anchor points (10) to approximate continuity. It was thus tested using linear mixed-effects modeling (MIXED command). Since both measures of daily perceived stress were positively skewed, they were tested under a Poisson distribution using a generalized estimating equation (GENLIN command) which, in both cases, presented a better model fit than with a normal distribution under a linear mixed-effects model.

When dream valence was the outcome variable, measures of daily stress from the preceding day were used as Level-1 predictors while trait, trauma and demographic variables were used as Level-2 predictors. Since dream recall frequency was measured daily, it was also used as a Level-1 predictor to assess its possible mediating effect on dream valence and other predictor variables, with values from 1 (one dream remembered on that night) to 3 (three or more dreams remembered). When daily stress was the outcome of interest, the dataset was shifted in order for a given night’s dream valence to be paired with levels of perceived stress of the following day. Considering that participants’ first daily measurement was for perceived stress, there was a smaller total of 2410 observations, not 2538, because the first stress values and last dream valence values were unpaired and thus excluded.

We first computed an intercepts-only model where time was not specified as a repeated measures variable and no predictors entered. This procedure is recommended to determine the amount of between-subject variance in the outcome variable, also known as the intraclass correlation 88 . The intraclass correlation was thus calculated by dividing the value of the intercept (between-group) variance by the sum of the residual (within-group) variance and intercept.

We then progressively added predictors to the unconditional model, beginning with individual Level-2 predictors. All Level-2 variables were grand mean centered. Level-1 stress predictor variables were centered to each participants’ mean for the duration of the study to account for dispositional biases in reported self-ratings.

Finally, post hoc analyses were performed to test alternate hypotheses. Interactions were tested between predictors to assess whether the model generalized to the whole sample or if some effects were moderated by other variables. We individually tested and reported the potential moderating effects of every level 2 predictor and of dream recall and valence (level 1) on each of the two level 1 stress predictors. The effect on dream valence of the stress variables from 2 to 7 days ago was also tested using lagged independent variables.

Data Availability

The datasets generated during and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Domhoff, G. W. Finding meaning in dreams: a quantitative approach ., https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4899-0298-6 (Plenum Press, 1996).

Book Google Scholar

Hall, C. S. & Nordby, V. J. The individual and his dreams . (Signet, 1972).

Domhoff, G. W. The emergence of dreaming: mind-wandering, embodied simulation, and the default network . (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Han, H. J., Schweickert, R., Xi, Z. & Viau-Quesnel, C. The cognitive social network in dreams: transitivity, assortativity, and giant component proportion are monotonic. Cogn. Sci. 40 , 671–696 (2016).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Pesant, N. & Zadra, A. Dream content and psychological well-being: a longitudinal study of the continuity hypothesis. J. Clin. Psychol. 62 , 111–121 (2006).

Schredl, M. & Erlacher, D. Relation between waking sport activities, reading, and dream content in sport students and psychology students. J. Psychol. 142 , 267–275 (2008).

Sikka, P., Pesonen, H. & Revonsuo, A. Peace of mind and anxiety in the waking state are related to the affective content of dreams. Sci. Rep. 8 , 1–13 (2018).

Article CAS Google Scholar

Davidson, J., Lee-Archer, S. & Sanders, G. Dream imagery and emotion. Dreaming 15 , 33–47 (2005).

Article Google Scholar

Gilchrist, S., Davidson, J. & Shakespeare-Finch, J. Dream emotions, waking emotions, personality characteristics and well-being — a positive psychology approach. Dreaming 17 , 172–185 (2007).

Nixon, A., Robidoux, R., Dale, A. L. & De Koninck, J. Pre-sleep and post-sleep mood as a complementary evaluation of emotionally impactful dreams. Int. J. Dream Res. 10 , 141–150 (2017).

Google Scholar

Schredl, M. Factors affecting the continuity between waking and dreaming: emotional intensity and emotional tone of the waking-life event. Sleep Hypn. 8 , 1–5 (2006).

Schredl, M. & Reinhard, I. The continuity between waking mood and dream emotions: direct and second-order effects. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 29 , 271–282 (2010).

St-Onge, M., Lortie-Lussier, M., Mercier, P., Grenier, J. & De Koninck, J. Emotions in the diary and REM dreams of young and late adulthood women and their relation to life satisfaction. Dreaming 15 , 116–128 (2005).

Fosse, R., Stickgold, R. & Hobson, J. A. The mind in REM sleep: reports of emotional experience. Sleep 24 , 1–9 (2001).

Hall, C. S. & Van de Castle, R. L. The content analysis of dreams. Central Psychology Series (Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1966).

Merritt, J. M., Stickgold, R., Pace-Schott, E. F., Williams, J. & Hobson, J. A. Emotion profiles in the dreams of men and women. Conscious. Cogn. 3 , 46–60 (1994).

Sikka, P., Valli, K., Virta, T. & Revonsuo, A. I know how you felt last night, or do I? Self- and external ratings of emotions in REM sleep dreams. Conscious. Cogn. 25 , 51–66 (2014).

Cartwright, R. D. The twenty-four hour mind: the role of sleep and dreaming in our emotional lives . (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Hartmann, E. The nature and functions of dreaming . (Oxford University Press, 2010).

Kramer, M. The selective mood regulatory function of dreaming: an update and revision. In The functions of dreaming . (eds Moffitt, A., Kramer, M. & Hoffmann, R.) 139–195 (State University of New York Press, 1993).

Cook, C. A. L., Caplan, R. D. & Wolowitz, H. Nonwaking responses to waking stressors: dreams and nightmares. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 20 , 199–226 (1990).

De Koninck, J. & Koulack, D. Dream content and adaptation to a stressful situation. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 84 , 250–260 (1975).

Delorme, M. A., Lortie-Lussier, M. & De Koninck, J. Stress and coping in the waking and dreaming states during an examination period. Dreaming 12 , 171–183 (2002).

Roberts, J., Lennings, C. J. & Heard, R. Nightmares, life stress, and anxiety: an examination of tension reduction. Dreaming 19 , 17–29 (2009).

Blagrove, M. & Pace-Schott, E. F. Trait and neurobiological correlates of individual differences in dream recall and dream content. In International Review of Neurobiology: Dreams and Dreaming . (eds Clow, A. & McNamara, P.) 92 , 155–180 (Elsevier, 2010).

Hartmann, E., Rosen, R. & Rand, W. Personality and dreaming: boundary structure and dream content. Dreaming 8 , 31–39 (1998).

Simor, P., Köteles, F., Sándor, P., Petke, Z. & Bódizs, R. Mindfulness and dream quality: the inverse relationship between mindfulness and negative dream affect. Scand. J. Psychol. 52 , 369–375 (2011).

Duval, M., McDuff, P. & Zadra, A. Nightmare frequency, nightmare distress, and psychopathology in female victims of childhood maltreatment. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 201 , 767–772 (2013).

Esposito, K., Benitez, A., Barza, L. & Mellman, T. A. Evaluation of dream content in combat-related PTSD. J. Trauma. Stress 12 , 681–687 (1999).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Helminen, E. & Punamäki, R.-L. Contextualized emotional images in children’s dreams: psychological adjustment in conditions of military trauma. Int. J. Behav. Dev. 32 , 177–187 (2008).

Valli, K. et al . The threat simulation theory of the evolutionary function of dreaming: evidence from dreams of traumatized children. Conscious. Cogn. 14 , 188–218 (2005).

Blagrove, M., Farmer, L. & Williams, E. The relationship of nightmare frequency and nightmare distress to well-being. J. Sleep Res. 13 , 129–136 (2004).

Zadra, A. & Donderi, D. C. Nightmares and bad dreams: their prevalence and relationship to well-being. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 109 , 273–281 (2000).

Levin, R. & Nielsen, T. A. Disturbed dreaming, posttraumatic stress disorder, and affect distress: a review and neurocognitive model. Psychol. Bull. 133 , 482–528 (2007).

Levin, R. & Nielsen, T. A. Nightmares, bad dreams and emotion dysregulation: a review and new neurocognitive model of dreaming. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 18 , 84–88 (2009).

Sandman, N. et al . Nightmares as predictors of suicide: an extension study including war veterans. Sci. Rep. 7 , 1–7 (2017).

Schredl, M. & Engelhardt, H. Dreaming and psychopathology: dream recall and dream content of psychiatric inpatients. Sleep Hypn. 3 , 44–54 (2001).

Soffer-Dudek, N. Arousal in nocturnal consciousness: how dream- and sleep-experiences may inform us of poor sleep quality, stress, and psychopathology. Front. Psychol. 8 , 1–10 (2017).

Nielsen, T. A. The stress acceleration hypothesis of nightmares. Front. Neurol. 8 , 1–23 (2017).

Hartmann, E. Boundaries in the mind: a new psychology of personality . (Basic Books, 1991).

Sylvers, P., Lilienfeld, S. O. & LaPrairie, J. L. Differences between trait fear and trait anxiety: implications for psychopathology. Clin. Psychol. Rev. 31 , 122–137 (2011).

Blagrove, M. & Fisher, S. Trait-state interactions in the etiology of nightmares. Dreaming 19 , 65–74 (2009).

Schredl, M., Schäfer, G., Hofmann, F. & Jacob, S. Dream content and personality: thick vs. thin boundaries. Dreaming 9 , 257–263 (1999).

Sándor, P., Horváth, K., Bódizs, R. & Konkolÿ Thege, B. Attachment and dream emotions: The mediating role of trait anxiety and depression. Curr. Psychol . 1–10, https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9890-y (2018).

Nielsen, T. A. et al . Development of disturbing dreams during adolescence and their relation to anxiety symptoms. Sleep 23 , 1–10 (2000).

Levin, R., Fireman, G., Spendlove, S. & Pope, A. The relative contribution of affect load and affect distress as predictors of disturbed dreaming. Behav. Sleep Med. 9 , 173–183 (2011).

Schredl, M. Effects of state and trait factors on nightmare frequency. Eur. Arch. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 253 , 241–247 (2003).

Soffer-Dudek, N. & Shahar, G. Daily stress interacts with trait dissociation to predict sleep-related experiences in young adults. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 120 , 719–729 (2011).

Cellucci, A. J. & Lawrence, P. S. Individual differences in self-reported sleep variable correlations among nightmare sufferers. J. Clin. Psychol. 34 , 721–725 (1978).

Malinowski, J. E. & Horton, C. L. Evidence for the preferential incorporation of emotional waking-life experiences into dreams. Dreaming 24 , 18–31 (2014).

Watson, D. Dissociations of the night: individual differences in sleep-related experiences and their relation to dissociation and schizotypy. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 110 , 526–535 (2001).

Nielsen, T. A., Kuiken, D., Alain, G., Stenstrom, P. & Powell, R. A. Immediate and delayed incorporations of events into dreams: Further replication and implications for dream function. J. Sleep Res. 13 , 327–336 (2004).

Eichenlaub, J.-B. et al . The nature of delayed dream incorporation (‘dream-lag effect’): personally significant events persist, but not major daily activities or concerns. J. Sleep Res. 28 , 1–8 (2019).

Agargun, M. Y. et al . Nightmares and dissociative experiences: the key role of childhood traumatic events. Psychiatry Clin. Neurosci. 57 , 139–145 (2003).

Wittmann, L., Schredl, M. & Kramer, M. Dreaming in posttraumatic stress disorder: a critical review of phenomenology, psychophysiology and treatment. Psychother. Psychosom. 76 , 25–39 (2007).

Duval, M. & Zadra, A. Frequency and content of dreams associated with trauma. Sleep Med. Clin. 5 , 249–260 (2010).

Aumann, C., Lahl, O. & Pietrowsky, R. Relationship between dream structure, boundary structure and the big five personality dimensions. Dreaming 22 , 124–135 (2012).

Zborowski, M., McNamara, P., Hartmann, E., Murphy, M. & Mattle, L. Boundary structure related to sleep measures and to dream content. Sleep 21S , 284 (1998).

Hartmann, E., Russ, D., Oldfield, M., Sivan, I. & Cooper, S. Who has nightmares? Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 44 , 49–56 (1987).

Wood, J. M. & Bootzin, R. R. The prevalence of nightmares and their independence from anxiety. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 99 , 64–68 (1990).

Robert, G. & Zadra, A. Measuring nightmare and bad dream frequency: impact of retrospective and prospective instruments. J. Sleep Res. 17 , 132–139 (2008).

Beaulieu-Prévost, D. & Zadra, A. Absorption, psychological boundaries and attitude towards dreams as correlates of dream recall: two decades of research seen through a meta-analysis. J. Sleep Res. 16 , 51–59 (2007).

Wood, J. M., Bootzin, R. R., Rosenhan, D., Nolen-Hoeksema, S. & Jourden, F. Effects of the 1989 San Francisco earthquake on frequency and content of nightmares. J. Abnorm. Psychol. 101 , 219–224 (1992).

Soffer-Dudek, N. & Shahar, G. Effect of exposure to terrorism on sleep-related experiences in Israeli young adults. Psychiatry Interpers. Biol. Process. 73 , 264–276 (2010).

Koulack, D., Prevost, F. & De Koninck, J. Sleep, dreaming, and adaptation to a stressful intellectual activity. Sleep 8 , 244–253 (1985).

Cartwright, R. D., Lloyd, S., Knight, S. & Trenholme, I. Broken dreams: a study of the effects of divorce and depression on dream content. Psychiatry 47 , 251–9 (1984).

Revonsuo, A., Tuominen, J. & Valli, K. Avatars in the machine: dreaming as a simulation of social reality. In Open Mind: Philosophy and the Mind Sciences in the 21st Century (eds Metzinger, T. & Windt, J. M.) 2 , 1295–1322 (MIND Group, 2016).

Takahashi, T. et al . Anxiety, reactivity, and social stress-induced cortisol elevation in humans. Neuroendocrinol. Lett. 26 , 351–354 (2005).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Tuominen, J., Stenberg, T., Revonsuo, A. & Valli, K. Social contents in dreams: an empirical test of the Social Simulation Theory. Conscious. Cogn. 69 , 133–145 (2019).

van Eck, M. M., Berkhof, H., Nicolson, N. A. & Sulon, J. The effects of perceived stress, traits, mood states, and stressful daily events on salivary cortisol. Psychosom. Med. 58 , 447–458 (1996).

Hirvikoski, T., Lindholm, T., Nordenström, A., Nordström, A. L. & Lajic, S. High self-perceived stress and many stressors, but normal diurnal cortisol rhythm, in adults with ADHD (attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder). Horm. Behav. 55 , 418–424 (2009).

Nagy, T. et al . Frequent nightmares are associated with blunted cortisol awakening response in women. Physiol. Behav. 147 , 233–237 (2015).

Payne, J. D. Memory consolidation, the diurnal rhythm of cortisol, and the nature of dreams: a new hypothesis. In International Review of Neurobiology: Dreams and Dreaming (eds Clow, A. & McNamara, P.) 92, 101–134 (Elsevier, 2010).

Carr, M. & Solomonova, E. Dream recall and content in different stages of sleep and time-of-night effect. In Dreams: Understanding Biology, Psychology, and Culture (eds Valli, K., Hoss, R. J. & Gongloff, R. P.) 188–194 (Greenwood Publishing Group, 2019).

Trinder, J. & Kramer, M. Dream recall. Am. J. Psychiatry 128 , 296–301 (1971).

Foulkes, D., Sullivan, B., Kerr, N. H. & Brown, L. Appropriateness of dream feelings to dreamed situations. Cogn. Emot. 2 , 29–39 (1988).

Nielsen, T. A., Deslauriers, D. & Baylor, G. W. Emotions in dream and waking event reports. Dreaming 1 , 287–300 (1991).

Schredl, M. & Doll, E. Emotions in diary dreams. Conscious. Cogn. 7 , 634–646 (1998).

Sikka, P., Feilhauer, D., Valli, K. & Revonsuo, A. How you measure is what you get: differences in self- and external ratings of emotional experiences in home dreams. Am. J. Psychol. 130 , 367–384 (2017).

Kunzendorf, R. G., Hartmann, E., Cohen, R. & Cutler, J. Bizarreness of the dreams and daydreams reported by individuals with thin and thick boundaries. Dreaming 7 , 265–271 (1997).

Spielberger, C. D., Gorsuch, R. L., Lushene, R. E., Vagg, P. R. & Jacobs, G. A. Manual for the State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (Form Y): Self-Evaluation Questionnaire. Consulting Psychologists Press , https://doi.org/10.5370/JEET.2014.9.2.478 (Consulting Psychologists Press, 1983).

Gauthier, J. & Bouchard, S. Adaptation canadienne-française de la forme revisée du State-Trait Anxiety Inventory de Spielberger. Rev. Can. des Sci. du Comport. 25 , 559–578 (1993).

Hébert, M., Cyr, M. & Zuk, S. Traduction et adaptation française du Early Trauma Inventory Self-Report - Short Form (ETISR-SF, 2007) de Bremner, Bolus et Mayer (2008).

Bremner, J. D., Bolus, R. & Mayer, E. A. Psychometric properties of the Early Trauma Inventory-Self Report. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 195 , 211–218 (2007).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Prins, A. et al . The primary care PTSD screen (PC–PTSD): development and operating characteristics. Prim. Care Psychiatry 9 , 9–14 (2004).

Brantley, P. J., Waggoner, C. D., Jones, G. N. & Rappaport, N. B. A daily stress inventory: development, reliability, and validity. J. Behav. Med. 10 , 61–73 (1987).

Woltman, H., Feldstain, A., MacKay, C. & Rocchi, M. An introduction to hierarchical linear modeling. Tutor. Quant. Methods Psychol. 8 , 52–69 (2012).

Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. S. Using multivariate statistics , https://doi.org/10.1037/022267 (Pearson Education Inc., 2019).

Download references

Acknowledgements

This research was funded by a grant from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC #435-2015-1181) and from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR # MOP 97865) to A.Z. The authors would like to thank Pierre McDuff for his help with statistical analyses, the Interdisciplinary Research Centre on Intimate Relationship Problems and Sexual Abuse (CRIPCAS) and the Centre for Studies on Human Stress (CSHS) for their assistance in the early phases of the study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Psychology, Université de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada

Eugénie Samson-Daoust, Sarah-Hélène Julien & Antonio Zadra

Department of Sexology, Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM), Montreal, QC, Canada

Dominic Beaulieu-Prévost

Center for Advanced Research in Sleep Medicine (CARSM), Hôpital du Sacré-Coeur de Montréal, Montreal, QC, Canada

Antonio Zadra

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

E.S.D. contributed to study design, conducted the study, analysed the results and wrote the manuscript draft. S.H.J. contributed to the study design and data collection. D.B.P. contributed to the statistical analyses and reviewed the manuscript. A.Z. obtained the grants, designed and supervised the study and reviewed the manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Antonio Zadra .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary tables, rights and permissions.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Samson-Daoust, E., Julien, SH., Beaulieu-Prévost, D. et al. Predicting the affective tone of everyday dreams: A prospective study of state and trait variables. Sci Rep 9 , 14780 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50859-w

Download citation

Received : 28 May 2019

Accepted : 15 September 2019

Published : 14 October 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-019-50859-w

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

By submitting a comment you agree to abide by our Terms and Community Guidelines . If you find something abusive or that does not comply with our terms or guidelines please flag it as inappropriate.

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Dreams and Dreaming

Dreams and dreaming have been discussed in diverse areas of philosophy ranging from epistemology to ethics, ontology, and more recently philosophy of mind and cognitive science. This entry provides an overview of major themes in the philosophy of sleep and dreaming, with a focus on Western analytic philosophy, and discusses relevant scientific findings.

1.1 Cartesian dream skepticism

1.2 earlier discussions of dream skepticism and why descartes’ version is special, 1.3 dreaming and other skeptical scenarios, 1.4 descartes’ solution to the dream problem and real-world dreams, 2.1 are dreams experiences, 2.2 dreams as instantaneous memory insertions, 2.3 empirical evidence on the question of dream experience, 2.4 dreams and hallucinations, 2.5 dreams and illusions, 2.6 dreams as imaginative experiences, 2.7 dreaming and waking mind wandering, 2.8 the problem of dream belief, 3.1 dreaming as a model system and test case for consciousness research, 3.2 dreams, psychosis, and delusions, 3.3 beyond dreams: dreamless sleep experience and the concepts of sleep, waking, and consciousness, 4. dreaming and the self, 5. immorality and moral responsibility in dreams, 6.1 the meaning of dreams, 6.2 the functions of dreaming, 7. conclusions, other internet resources, related entries, 1. dreams and epistemology.

Dream skepticism has traditionally been the most famous and widely discussed philosophical problem raised by dreaming (see Williams 1978; Stroud 1984). In the Meditations , Descartes uses dreams to motivate skepticism about sensory-based beliefs about the external world and his own bodily existence. He notes that sensory experience can also lead us astray in commonplace sensory illusions such as seeing things as too big or small. But he does not think such cases justify general doubts about the reliability of sensory perception: by taking a closer look at an object seen under suboptimal conditions, we can easily avoid deception. By contrast, dreams suggest that even in a seemingly best-case scenario of sensory perception (Stroud 1984), deception is possible. Even the realistic experience of sitting dressed by the fire and looking at a piece of paper in one’s hands (Descartes 1641: I.5) is something that can, and according to Descartes often does, occur in a dream.

There are different ways of construing the dream argument. A strong reading is that Descartes is trapped in a lifelong dream and none of his experiences have ever been caused by external objects (the Always Dreaming Doubt ; see Newman 2019). A weaker reading is that he is just sometimes dreaming but cannot rule out at any given moment that he is dreaming right now (the Now Dreaming Doubt ; see Newman 2019). This is still epistemologically worrisome: even though some of his sensory-based beliefs might be true, he cannot determine which these are unless he can rule out that he is dreaming. Doubt is thus cast on all of his beliefs, making sensory-based knowledge slip out of reach.

Cartesian-style skeptical arguments have the following form (quoted from Klein 2015):

- If I know that p , then there are no genuine grounds for doubting that p .

- U is a genuine ground for doubting that p .

- Therefore, I do not know that p .

If we apply this to the case of dreaming, we get:

- If I know that I am sitting dressed by the fire, then there are no genuine grounds for doubting that I am really sitting dressed by the fire.

- If I were now dreaming, this would be a genuine ground for doubting that I am sitting dressed by the fire: in dreams, I have often had the realistic experience of sitting dressed by the fire when I was actually lying undressed in bed!

- Therefore, I do not know that I am now sitting dressed by the fire.

Importantly, both strong and weak versions of the dream argument cast doubt only on sensory-based beliefs, but leave other beliefs unscathed. According to Descartes, that 2+3=5 or that a square has no more than 4 sides is knowable even if he is now dreaming:

although, in truth, I should be dreaming, the rule still holds that all which is clearly presented to my intellect is indisputably true. (Descartes 1641: V.15)

By Descartes’ lights, dreams do not undermine our ability to engage in the project of pure, rational enquiry (Frankfurt 1970; but see Broughton 2002).

Dream arguments have been a staple of philosophical skepticism since antiquity and were so well known that in his objections to the Meditations , Hobbes (1641) criticized Descartes for not having come up with a more original argument. Yet, Descartes’ version of the problem, more than any other, has left its mark on the philosophical discussion.

Earlier versions tended to touch upon dreams just briefly and discuss them alongside other examples of sensory deception. For example, in the Theaetetus (157e), Plato has Socrates discuss a defect in perception that is common to

dreams and diseases, including insanity, and everything else that is said to cause illusions of sight and hearing and the other senses.

This leads to the conclusion that knowledge cannot be defined through perception.

Dreams also appear in the canon of standard skeptical arguments used by the Pyrrhonists. Again, dreams and sleep are just one of several conditions (including illness, joy, and sorrow) that cast doubt on the trusthworthiness of sensory perception (Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers; Sextus Empiricus, Outlines of Pyrrhonism) .

Augustine ( Against the Academics ; Confessions) thought the dream problem could be contained, arguing that in retrospect, we can distinguish both dreams and illusions from actual perception (Matthew 2005: chapter 8). And Montaigne ( The Apology for Raymond Sebond ) noted that wakefulness itself teems with reveries and illusions, which he thought were even more epistemologically worrisome than nocturnal dreams.

Descartes devoted much more space to the discussion of dreaming and cast it as a unique epistemological threat distinct from both waking illusions and evil genius or brain-in-a-vat-style arguments. His claim that he has often been deceived by his dreams implies he also saw dreaming as a real-world (rather than merely hypothetical) threat.

This is further highlighted by the intimate, first-person style of the Meditations . Their narrator is supposed to exemplify everyone’s epistemic situation, illustrating the typical defects of the human mind. Readers are further drawn in by Descartes’ strategy of moving from commonsense examples towards more sophisticated philosophical claims (Frankfurt 1970). For example, Descartes builds up towards dream skepticism by first considering familiar cases of sensory illusions and then deceptively realistic dreams.

Finally, much attention has been devoted to several dreams Descartes reportedly had as a young man. Some believe these dreams embodied theoretical doubts he developed in the Discourse and Meditations (Baillet 1691; Leibniz 1880: IV; Cole 1992; Keefer 1996). Hacking (2001:252) suggests that for Descartes, dream skepticism was not just a philosophical conundrum but a source of genuine doubt. There is also some discussion about the dream reports’ authenticity (Freud 1940; Cole 1992; Clarke 2006; Browne 1977).

In the Meditations , after discussing the dream argument, Descartes raises the possibility of an omnipotent evil genius determined to deceive us even in our most basic beliefs. Contrary to dream deception, Descartes emphasizes that the evil genius hypothesis is a mere fiction. Still, it radicalizes the dream doubt in two respects. One, where the dream argument left the knowability of certain general truths intact, these are cast in doubt by the evil genius hypothesis . Two, where the dream argument, at least on the weaker reading, involves just temporary deception, the evil genius has us permanently deceived.

One modernized version, the brain-in-a-vat thought experiment, says that if evil scientists placed your brain in a vat and stimulated it just right, your conscious experience would be exactly the same as if you were still an ordinary, embodied human being (Putnam 1981). In the Matrix -trilogy (Chalmers 2005), Matrixers live unbeknownst to themselves in a computer simulation. Unlike the brain-in-a-vat , they have bodies that are kept alive in pods, and flaws in the simulation allow some of them to bend its rules to their advantage.

Unlike dream deception, which is often cast as a regularly recurring actuality (cf. Windt 2011), brain-in-a-vat-style arguments are often thought to be merely logically or nomologically possible. However, there might be good reasons for thinking that we actually live in a computer simulation (Bostrom 2003), and if we lend some credence to radical skeptical scenarios, this may have consequences for how we act (Schwitzgebel 2017).

Even purely hypothetical skeptical scenarios may enhance their psychological force by capitalizing on the analogy with dreams. Clark (2005) argues that the Matrix contains elements of “industrial-strength deception” in which both sensory experience and intellectual functioning are exactly the same as in standard wake-states, whereas other aspects are more similar to the compromised reasoning and bizarre shifts that are the hallmark of dreams.

At the end of the Sixth Meditation , Descartes suggests a solution to the dream problem that is tied to a reassessment of what it is like to dream. Contrary to his remarks in the First Meditation , he notes that dreams are only rarely connected to waking memories and are often discontinuous, as when dream characters suddenly appear or disappear. He then introduces the coherence test:

But when I perceive objects with regard to which I can distinctly determine both the place whence they come, and that in which they are, and the time at which they appear to me, and when, without interruption, I can connect the perception I have of them with the whole of the other parts of my life, I am perfectly sure that what I thus perceive occurs while I am awake and not during sleep. (Meditation VI. 24)

For all practical purposes, he has now found a mark by which dreaming and waking can be distinguished (cf. Meditation I.7), and even if the coherence test is not fail-safe, the threat of dream deception has been averted.

Descartes’ remarks about the discontinuous and ad hoc nature of many dreams are backed up by empirical work on dream bizarreness (see Hobson 1988; Revonsuo & Salmivalli 1995). Still, many of his critics were not convinced this helped his case against the skeptic. Even if Descartes’ revised phenomenological description characterizes most dreams, one might occasionally merely dream of successfully performing the test (Hobbes 1641), and in some dreams, one might seem to have a clear and distinct idea but this impression is false (Bourdin 1641). Both the coherence test and the criterion of clarity and distinctness would then be unreliable.

How considerations of empirical plausibility impact the dream argument continues to be a matter of debate. Grundmann (2002) appeals to scientific dream research to introduce an introspective criterion: when we introspectively notice that we are able to engage in critical reflection, we have good reason to think that we are awake and not dreaming. However, this assumes critical reasoning to be uniformly absent in dreams. If attempts at critical reasoning do occur in dreams and if they generally tend to be corrupted, the introspective criterion might again be problematic (Windt 2011, 2015a). There are also cases in which even after awakening, people mistake what was in fact a dream for reality (Wamsley et al. 2014). At least in certain situations and for some people, dream deception might be a genuine cause of concern (Windt 2015a).

2. The ontology of dreams

In what follows, the term “conscious experience” is used as an umbrella term for the occurrence of sensations, thoughts, impressions, emotions etc. in dreams (cf. Dennett 1976). These are all phenomenal states: there is something it is like to be in these states for the subject of experience (cf. Nagel 1974). To ask about dream experience is to ask whether it is like something to dream while dreaming, and whether what it is like is similar to (or relevantly different from) corresponding waking experiences.

Cartesian dream skepticism depends on a seemingly innocent background assumption: that dreams are conscious experiences. If this is false, then dreams are not deceptive experiences during sleep and we cannot be deceived, while dreaming, about anything at all. Whether dreams are experiences is a major question for the ontology of dreams and closely bound up with dream skepticism.

The most famous argument denying that dreams are experiences was formulated by Norman Malcolm (1956, 1959). Today, his position is commonly rejected as implausible. Still, it set the tone for the analysis of dreaming as a target phenomenon for philosophy of mind.

For Malcolm, the denial of dream experience followed from the conceptual analysis of sleep: “if a person is in any state of consciousness it logically follows that he is not sound asleep” (Malcolm 1956: 21). Following some remarks of Wittgenstein’s (1953: 184; see Chihara 1965 for discussion), Malcolm claimed

the concept of dreaming is derived, not from dreaming, but from descriptions of dreams, i.e., from the familiar phenomenon that we call “telling a dream”. (Malcolm 1959:55)

Malcolm argued that retrospective dream reports are the sole criterion for determining whether a dream occurred and there is no independent way of verifying dream reports. While first-person, past-tense psychological statements (such as “I felt afraid”) can at least in principle be verified by independent observations (but see Canfield 1961; Siegler 1967; Schröder 1997), he argued dream reports (such as “in my dream, I felt afraid”) are governed by different grammars and merely superficially resemble waking reports. In particular, he denied dream reports imply the occurrence of experiences (such as thoughts, feelings, or judgements) in sleep:

If a man had certain thoughts and feelings in a dream it no more follows that he had those thoughts and feelings while asleep, than it follows from his having climbed a mountain in a dream that he climbed a mountain while asleep. (Malcolm 1959/1962: 51–52)

What exactly Malcolm means by “conscious experience” is unclear. Sometimes he seems to be saying that conscious experience is conceptually tied to wakefulness (Malcolm 1956); other times he claims that terms such as mental activity or conscious experience are vague and it is senseless to apply them to sleep and dreams (Malcolm 1959: 52).

Malcolm’s analysis of dreaming has been criticized as assuming an overly strict form of verificationism and a naïve view of language and conceptual change. A particularly counterintuitive consequence of his view is that there can be no observational evidence for the occurrence of dreams in sleep aside from dream reports. This includes behavioral evidence such as sleepwalking or sleeptalking, which he thought showed the person was partially awake; as he also thought dreams occur in sound sleep, such sleep behaviors were largely irrelevant to the investigation of dreaming proper. He also claimed adopting a physiological criterion of dreaming (such as EEG measures of brain activity during sleep) would change the concept of dreaming, which he argued was tied exclusively to dream reporting. This claim was particularly radical as it explicitly targeted the discovery of REM sleep and its association with dreaming (Dement & Kleitman 1957), which is commonly regarded as the beginning of the science of sleep and dreaming. Malcolm’s position was that the very project of a science of dreaming was misguided.

Contra Malcolm, most assume that justification does not depend on strict criteria with the help of which the truth of a statement can be determined with absolute certainty, but “on appeals to the simplicity, plausibility, and predictive adequacy of an explanatory system as a whole” (Chihara & Fodor 1965: 197). In this view, behavioral and/or physiological evidence can be used to verify dream reports (Ayer 1960) and the alleged principled difference between dream reports and other first-person, past-tense psychological sentences (Siegler 1967; Schröder 1997) disappears.

Putnam noted that Malcolm’s analysis of the concept of dreaming relies on the dubious idea that philosophers have access to deep conceptual truths that are hidden to laypeople:

the lexicographer would undoubtedly perceive the logical (or semantical) connection between being a pediatrician and being a doctor, but he would miss the allegedly “logical” character of the connection between dreams and waking impressions. […] this “depth grammar” kind of analyticity (or “logical dependence”) does not exist. (Putnam 1962 [1986]: 306)