Improving economics teaching and learning for over 20 years

Case study 1: First Year Economic Theory

Steve Cook and Duncan Watson Swansea University

Published February 2013

Part of the Handbook chapter on Assessment Design and Methods

When considering assessment methods in economics, arguably one of the most interesting potential case studies concerns introductory economic theory. Amongst the various challenges faced by those delivering such a module are the issues of setting the tone for subsequent years of study and addressing the transition between school and university education. For many years, first year undergraduate economic theory at Swansea University has been split into two modules. Both labelled Principles of Economics, the ‘A’ version of the module is taken by students arriving with post-GCSE experience of Economics (A-level, AS-level, foundation year, IB etc.), while students without such a background are enrolled on Principles of Economics B. These year-long modules combine both standard introductory microeconomic and macroeconomic content and are structured in such a fashion as to equally prepare students from differing backgrounds for the demands of their future studies. In an attempt to increase student engagement, 2009–10 saw the introduction of a new assessment scheme for Principles of Economics A. The ‘old’ scheme comprised of a mid-year January multiple-choice examination, an in-class disclosed examination and a standard summer (May/June) examination. [1] The weightings attached to these components were 30 per cent, 10 per cent and 60 per cent respectively. The new assessment scheme involved the introduction of six within-tutorial mini-assessments spread throughout the year with the best five marks to be included at weighting of 4 per cent each. The revised assessment scheme therefore involved a reduction in the weighting of other assessment components to accommodate the tutorial-based assessment, and consequently involved a corresponding change in the content of these components. The resulting structure was then: tutorial-based exercises (20 per cent), January examination (20 per cent), in-class examination (10 per cent) and summer examination (50 per cent). It should be noted that these summative assessment components are in addition to formative elements contained within the module.

The revised assessment scheme sought to achieve a number of objectives. First, it aimed to increase the extent to which students work consistently throughout the year by introducing an additional six elements of assessment within term. Second, it aimed to introduce a mechanism for students to gauge their understanding of topics and material as soon as possible. As a number of elements of the syllabus will be familiar to students from their earlier studies, there is always a possibility of students focusing their attention and efforts on those topics which are new and paying insufficient attention to previously considered concepts and terminology. Obviously this is not to be encouraged as, aside from the necessity for understanding to be refreshed, it will prove particularly problematic when material is presented in a different, extended or advanced manner to that previously experienced. However, this may only come to light when confronted with assessment which forces closer examination of topics in formal setting. The use of frequent lower weighted assessment allows any misdirection of efforts or gaps in knowledge to be addressed quickly ahead of becoming substantive issues detected in a more weighty assessment component. A third obvious intention of the in-tutorial assessment was to increase the preparedness of students for their more heavily weighted assessments later in the module. The regularity of testing not only ensures a familiarity with the ‘rules and regulations’ of examinations and settles students ahead of the more substantive latter assessment components, but also allows knowledge to build progressively through the year.

In terms of the structure or mechanics of the tutorial-based assessment, this was very straightforward to devise. The module already contained a series of fortnightly tutorials which involved students discussing and working through previously circulated exercise sheets designed to illustrate material presented in lectures. The expectation is that students attempt the exercises ahead of the sessions and then focus more closely with their tutor during tutorials on those elements they feel warrant further analysis to improve their understanding. The tutorial-based assessments were introduced to six sessions (three in each teaching block). This meant that time allocated to the circulated exercises sheets was reduced to allow time to undertake a 10-minute mini-assessment. In each instance, the assessment involved a series of very short questions which were very similar in nature to those covered in the circulated exercise sheet. This reveals a further objective of the assessment in its role as a further prompt to attempt the circulated exercise sheets and engagement with the tutor to resolve any uncertainties concerning material. An example of the nature of the tutorial-based assessment is provided below. This simple mini-test provides students and tutors alike with a quick means of assessing understanding of material covered. In this particular case, the four-part assessment picks up upon issues in consumer choice. Alternatively phrased the questions ask: ‘What is implied by the positioning of an indifference curve?’, ‘What is implied by the slope of an indifference curve?’, ‘What is implied by the shape of an indifference curve?’, ‘How can we construct/manipulate/employ budget lines/constraints’. It can be seen that the exercises provided are simple in nature to assess quickly understanding in a manner that goes beyond that afforded by multiple-choice examination. However, the demands on the tutor are minimal as the marking involved is very straightforward and hence feedback can be provided to all students extremely quickly. Importantly, these are crucial issues and the assessment of student understanding of them can be assessed quickly ahead of formalising the knowledge to move on to consider substitution and income effects.

The feedback on the revised assessment can be considered in two ways. First, changes in module marks can be considered. Information on this is provided in Table 1. However, before considering the figures provided, a number of issues must be recognised. The information to be considered provides broad measures of student performance on the Principles of Economics A module over a three-year period. Table 1 provides three sets of information on the two Principles of Economics modules. The first set of information simply provides the number of students taking the module each year. Clearly version ‘B’ is larger than ‘A’. The second set of information presents the change in the average module mark relative to the year before assessment on Principles of Economics A was revised. In this instance, the other module which does not have a revised assessment method acts as something of a control (albeit in a loose sense). The ‘Average Difference’ column provides information on average difference in the marks students obtain on this module and those they obtain elsewhere. By considering the relative performance both across modules for each year and then over a number of years, some control for cohort effects is present and a snapshot of the general impact of changes in assessment design can be inferred. However, it is recognised that a variety of factors (different students, different questions etc.) make it difficult to identify the true impact of a change in assessment.

Level-1 Economic Theory: Student Numbers, Mean Mark and Relative Module Performance

An example of the Level 1 tutorial-based assessment

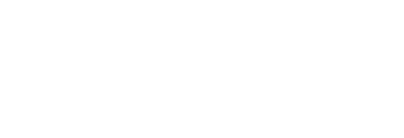

1. The indifference curves below (denoted as E, F and G) relate to differing levels of utility obtained from the consumption of Goods X and Y. One of the indifference curves corresponds to 2 utils, another corresponds to 8 utils, while another corresponds to 6 utils. Which curve depicts 8 utils?

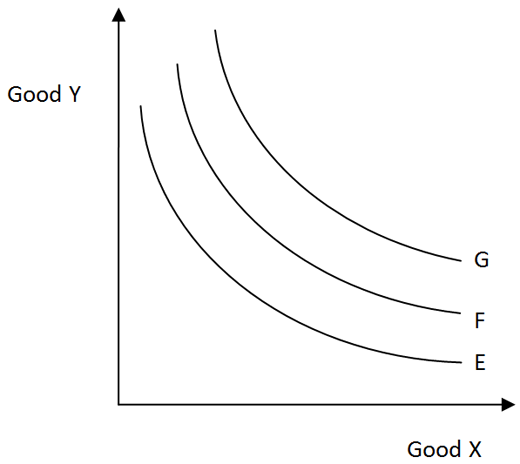

2. Consider the indifference curve depicted in the diagram below. Annotate this diagram by marking two distinct points on this indifference curve. Label these points ‘C’ and ‘D’ in such a way that point ‘D’ corresponds to a lower marginal rate of substitution than point ‘C’. Using a single sentence, explain your answer.

3. It is known that the indifference curve for two goods is L-shaped. What does this tell you about the relationship between these goods?

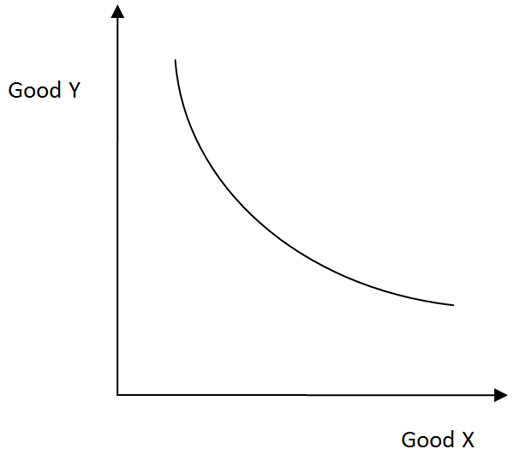

4. Consider the budget line (BL) depicted in the diagram below for given prices of Goods X and Y and a given level of money income. Suppose that following the drawing of BL, the price of Good X remains the same, the price of Good Y doubles, and the level of money income doubles. Sketch the new budget line on the diagram below.

From consideration of the results presented in Table 1 it can be seen that a dramatic jump in the mean for Principles of Economics A occurred following the introduction of a revised assessment scheme. From inspection of the results for Principles of Economics B, it is apparent that this module experienced an increase in its mean mark at the same time. However, the increases in marks on the modules differ, with the module with in-tutorial assessment experiencing an increase of 8.5 percentage points in its first year following the change, in comparison to the increase of 4.9 percentage points on the other module. This is indicative of an increase above and beyond a cohort effect. Similarly, when considering the average difference between the marks obtained by students on this module and elsewhere, this narrowed for Principles of Economics A (from being an average of 7.6 percentage points below to only 1.4 percent points below) while it widened on the corresponding Principles of Economics B module (on average students scored 6.6 percentage points less in 2008–09, and 6.8 percentage points less in 2009–10). It should be noted that historically these theory-based modules do return lower marks than other application-based modules taken at Level 1. The results obtained in the second year of delivery of the module under the revised assessment policy (2010–11) make for interesting reading. On the one hand, it appears that the noted improvement in the previous year has been reversed, with the gulf between the mark obtained on the module and elsewhere widening (it increases to 3.2 percentage points). In combination with the increased average mark, this is indicative of a cohort effect, with marks increasing in general, but not by as much on this module as elsewhere. However, at the same time the corresponding gulf for the Principles of Economics B module has widened by more (2.4 percentage points from –6.8 per cent to –9.2 per cent). This would then suggest that a general disparity between theoretical and non-theoretical modules has been less acute for the module where a revised assessment policy has been implemented. Considering the results presented for all years available, the introduction of a new assessment structure has led to an increase in marks and a narrowing of the differences between the module concerned and others when considered from its time of implementation to the present day, while the module without changes in assessment has seen the gulf between it and others widen. In terms of qualitative feedback on in-tutorial assessment, its introduction has received favourable comment from students and staff alike.

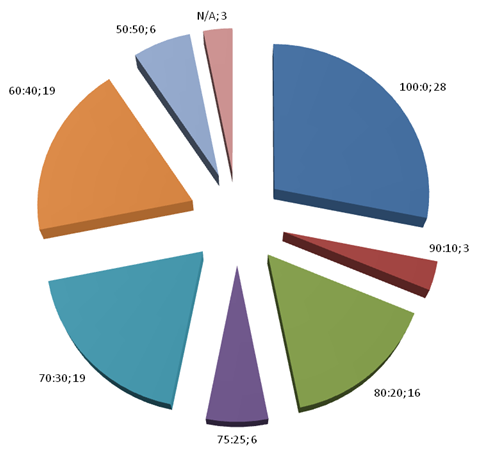

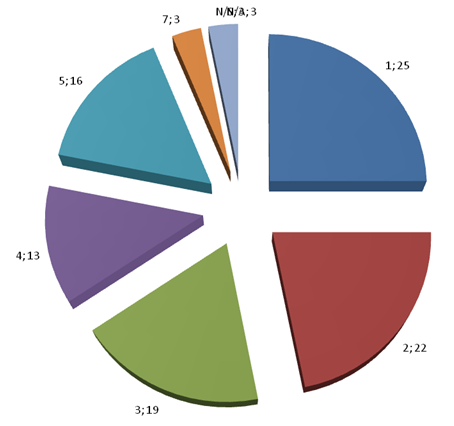

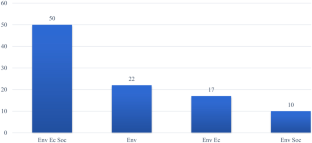

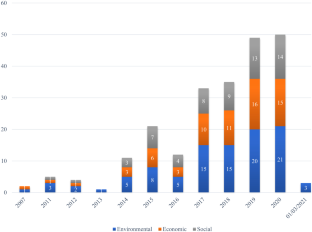

Considering the level of assessment on the Level 1 economic theory module, the summative assessment is entirely based upon examination, although an element of it is disclosed (10 per cent), six elements are mini-assessment or quizzes (20 per cent) and a further element is multiple-choice examination (20 per cent). Therefore only 50 per cent is based upon an essay-based examination. To consider this assessment split relative to other Economics departments (or groups) in the UK, a survey was conducted involving 32 departments. [2] The information gleaned from this on the assessment of Level 1 economic theory is reported in Figure 2 below. This chart provides a breakdown of the examination/coursework split for analogous Level 1 economic theory modules along with a figure indicating the percentage of departments adopting this approach. It can be seen that the most popular form of assessment is via 100 per cent examination (28 per cent of surveyed departments adopting this approach), followed by 60:40 and 70:30 splits (both being adopted by 19 per cent of departments). However, the division of assessment between these two components could mask a range of differing numbers of assessments. This is of particular importance as to the extent that one of the aims of assessment should be to increase engagement, the frequency of assessment is of importance. For example, Principles of Economics A, has four forms of assessment but nine points of summative assessment are employed. Figure 3, containing the results for 32 UK Economics departments, surprisingly shows that a single element of summative assessment is the most popularly employed frequency of assessment (25 per cent of departments surveyed), followed by two and then three points of assessment (22 per cent and 19 per cent respectively).

Considering the outcomes noted above and the information contained in the survey of economics departments, the new assessment scheme has proved successful and has also led to a high frequency of assessment relative to the national norm. However, given the improvements in outcomes and student experience, along with the relative ease of implementation, the additional resources required for such a change are a very small price to pay for a huge return.

Figure 2: A survey of Level 1 Economic Theory assessment weightings

(Exam : Coursework; Percentage of institutions)

Figure 3: A survey of Level 1 Economic Theory assessment components

(Number of components; Percentage of institutions)

[1] The ‘disclosed’ examination involves the provision of two essay titles approximately six weeks ahead of the examination date. Students are asked to prepare for both, with the actual essay to be attempted not revealed until turning over the test paper in the examination venue.

[2] A survey of UK Economics Departments was conducted to consider provision relating to all of the case studies considered herein (Level 1 economic theory; final year dissertation; final year econometrics). Results are reported for instances where information was available for all areas covered by the case studies. The desire to use a consistent sample across all case studies resulted in the use of 32 departments.

- Assessment and monitoring

- Views on request

Browser does not support script.

- Departments and Institutes

- Research centres and groups

- Chair's Blog: Summer Term 2022

- Staff wellbeing

Case studies

Case studies usually involve real-life situations and often take the form of a problem-based inquiry approach; in other words students are presented with a complex real life situation that they are asked to find a solution to. “The benefits of utilizing case studies in instruction include the way that cases model how to think professionally about real problems and situations, helping candidates to think productively about concrete experiences” (Kleinfeld, 1990 in Ulanoff, Fingon and Beltran, 2009). The case study method involves placing students in the role of decision-makers and asking them to address a challenge that may confront a company, non-profit organisation or government department. In the absence of a single straightforward answer students are expected to exchange ideas, consider possible theoretical explanations and data, and weigh up possible solutions. Based on this exchange and evaluation of mixed data they are expected to come up with a decision, and choose a solution to the particular challenge. Though case study learning and assessment may take many forms the common thread is that the case study involves a real-life situation and finding solutions is the focus of the assessment.

Advantages of case studies

- Enables students to apply their knowledge and skills to real life situations.

- Can be undertaken individually or as a group assessment.

- Generally designed to assess the higher levels of Bloom’s taxonomy of educational objectives (application, analysis and evaluation).

- Well adapted to multi- or inter-disciplinary learning.

- Calls on students to demonstrate a range of different skills such as the selection on information, analysis, decision-making problem-solving and presentation.

- In the case of a group-based approach students are given the opportunity to demonstrate their ability to collaborate and communicate effectively.

- Supports the development of a range of valuable employability skills which are likely to be attractive to employers and students alike.

Challenges of case studies

- Case studies can be used in time-constrained examinations but this method of assessment really lends itself better to a coursework approach.

- Can be a complex activity that involves negotiating a range of media that may be hard to contain in a controlled environment.

- It is important to have realistic expectations of what actually can be achieved.

- Planning and preparing for case study work can be time-consuming for teachers.

How students might experience case studies

There is some evidence to suggest that case studies increase students’ motivation. Students are often very interested in working on real life situations. It brings their learning alive and enables them not only to develop solutions to actual situations/problems but also to understand in new ways the valuable role that theory and relevant concepts can play as part of this process. In addition as part of their work on the case study they are clearly developing valuable transferable skills that they can take forward into the workplace and society at large. Students may not be used to this form of assessment so they will need clear guidance as to what is expected (length, format, main elements), a clear explanation of marking criteria as well as development in the different skills they will need to acquire in order to successfully complete the case study. These will in part depend on the nature of the case study - is data analysis involved?; where and how will students find relevant qualitative and quantitative data?; what is the appropriate way of citing and referencing?

Reliability, validity, fairness and inclusivity of case studies

Teaching and learning activities should be carefully designed to support the work on the case study or the development of the relevant skills and knowledge bases. From an inclusive design perspective case studies are an attractive form of learning and assessment. Depending on the nature of the inquiry students may be given a degree of choice over their case study and thus be in a position to bring their different backgrounds and experience to bear. In any case, it is important to ensure that the chosen case studies are accessible to all students taking the course. In the case of first year students the teacher may want to provide all the relevant materials to the students. For more advanced students, they may be expected to do some research and to identify relevant supporting materials for the case study inquiry. Where group work is involved a number of options may be considered to ensure fairness. The students may complete some elements of both formative and summative work as a group as well as others individually. For example, students may complete various tasks or give a presentation on the case study as a group but write up part of the final case study individually. In addition, it is relatively common practice to ask students engaged in groupwork to write a short reflective piece discussing their experience of group work. Students can also be asked to rate their contribution and the contribution of other members of the group using one of a number of online group assessment tools such as WebPA and Teammates.

How to maintain and ensure rigour in case studies

Critical to ensuring rigour is having clarity about the different parts of the case study or, in the case of a single assessment task, the criteria against which the assessment will be marked; the weight that will be attached to different parts of the assignment, and the marking scheme. Marking and moderation should follow departmental practice.

How to limit possible misconduct in case studies

Whether the students are working in groups or individually teachers can check that the work is the work of particular students by designing in opportunities to assess (formatively or summatively) work at several points in the assessment process. This can be done by asking students to present work in written or oral form – either by submitting assignment tasks via Moodle or making short presentations in class. In addition to serving as a check for misconduct this also provides an opportunity for teachers and peers to give constructive feedback on the development of the case study and as such constitutes good practice.

LSE examples

Daniel Ferreira discussed his use of case studies in teaching Master’s level Finance students for many years, and, starting in 2016/17 undergraduates with the introduction of the Finance department’s new BSc programme

http://lti.lse.ac.uk/lse-innovators/irene-papanicolas-healthy-collaboration/

Further resources

University of New South Wales, Sydney: Assessment by Case Studies and Scenarios https://teaching.unsw.edu.au/assessment-case-studies-and-scenarios

Assessment Resources at Hong Kong University: Types of Assessment Methods: Case Study http://ar.cetl.hku.hk/am_case_study.htm

Bonney, K.M. (2015) Case Study Teaching Method Improves Student Performance and Perceptions of Learning Gains. Journal of Microbiological Education , 16(1): 21–28

Ulanoff, S.H., Fingon, J.C. and Beltrán, D. (2009) Using Case Studies To Assess Candidates’ Knowledge and Skills in a Graduate Reading Program, Teacher Education Quarterly, 6(2): 125-142

Fry, H., Ketteridge, S. and Marshall, S. (1999) A Handbook for Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, Routledge, UK

Back to Assessment methods

Back to Toolkit Main page

Contact your Eden Centre departmental adviser

If you have any suggestions for future Toolkit development, get in touch using our email below!

Email: [email protected].

Economic Impact Case Study Tool for Transit (2016)

Chapter: chapter 2 - case study selection and compilation.

Below is the uncorrected machine-read text of this chapter, intended to provide our own search engines and external engines with highly rich, chapter-representative searchable text of each book. Because it is UNCORRECTED material, please consider the following text as a useful but insufficient proxy for the authoritative book pages.

7 C H A P T E R 2 The work scope for this study called for seven case studies to be developed as a pilot demonstration of the TPICS con cept for transit. These case studies are built upon the struc ture and process developed for SHRP 2 Project C03 (EDR Group et al., 2012). This process follows closely that which was used to develop highway case studies while identifying which adaptations are necessary to improve the highway pro cess for application to transit cases. The process of identifying potential case studies serves to provide a basis for estimat ing the feasibility of expanding the existing system of case studies to encompass a larger set of transit cases if desired in the future. 2.1 Identification and Selection Process The selection process for the seven pilots involved four steps, which are described in this section. This process pro vided a list of additional projects that could be studied in the future. This process may help in identifying more options for study at a later date. Case Selection Step 1: Define Criteria The first step was to develop a request for case study nomi nations. The project team initially developed a draft set of project criteria, which was reviewed by the project panel, and then incorporated the approved criteria into an announce ment seeking case study nominations. The announcement text can be seen in Figure 1. Compared with the previous work for SHRP 2 C03 in compil ing a highway database, the transit project used a more recent, and shorter time period. The reason for specifying the 2000â 2010 time period was to ensure a focus on projects that are old enough to have a high likelihood that postÂproject economic development impacts will be clearly completed and hence observable, yet are not so old that it is difficult to find local agency contacts who were in their jobs long enough to remem ber preÂproject conditions and local factors affecting project outcomes. The latter consideration is particularly notable because multiple local interviews are required to provide infor mation regarding the role of the transit investment relative to other factors in affecting observed economic and develop ment outcomes. Thus, the specified time period was judged optimal for initial case studies as older or newer projects would be more likely to involve greater staff effort to complete the case studies. (Older projects could require more effort to find suitable interviewees; newer projects could require more effort to discern emerging trends not yet reflected in public datasets.) The project team recognizes, however, that in the future there may also be cases where there is sufficient infor mation available to enable the further addition of some older and some more recent projects. The issue of time period for future studies is discussed in Chapter 5. The solicitation for transit case nominations also utilized a smaller cost threshold than the highwayÂfocused case studies after which they are formatted due to the expectation that transit projects are smaller than the major highway projects selected. The reason for the minimum $5 million investment size was to focus on projects that are large enough to have a reasonable likelihood of finding impacts. While it is indeed desirable to include projects that had disappointingly small economic development impacts (as well as those with sur prisingly large impacts), it was agreed that the pilot case studies should not focus on small projects that had little, if any, expectation of economic development impacts. As we will discuss in more detail later (in Chapter 5), for future case studies, we would recommend a higher threshold as few of the projects nominated or those subsequently investigated were so small. Case Study Selection and Compilation

8study team decided to provide a 1Âyear grace period and accept projects completed between 1999 and 2011. Six of the case study nominations fell outside of that period and, thus, were deleted from further consideration for this study. While these projects were taken out of the running for this TPICS for Transit pilot demonstration, they could still make for good case studies for an expanded TPICS sys tem in the future. The announced project date range was defined in the first place to minimize likely staff effort for case study data collection and interview completion. With a better funded effort in the future, those date requirements could be relaxed further. 2. Check for Inclusion in Prior SHRP 2 Study. While the ear lier SHRP 2 study focused on developing TPICS for high ways, it ended up developing nine case studies for highway/ transit intermodal facilities. Those projects, while also good candidates for inclusion in the new TPICS for Transit, already have case studies developed and, hence, are not candidates for new case study development. Thus, those nine projects were also deleted from further consideration for this study. 3. Check for Low Passenger Activity Level. While all forms of transit may be candidates for case study development, the pilot demonstration should focus on projects that have a substantial level of service provided all day long with activity focused at specific sites so as to support significant economic development nearby. Many commuter rail stops and stations have activity concentrated during rushÂhour periods, with relatively infrequent service at other times. As a result, the economic impact of most commuter rail stations or stops is relatively limited (e.g., a commuter rail station with takeÂout coffee and sandwich sales). For this reason, four of the five commuter rail projects were deleted from further consideration for this study. 4. Screen Out Upgrades to Existing Facilities. Projects with âstate of good repairâ goals typically have broadly diffused Case Selection Step 2: Distribution of Request for Nomination of Case Studies The second step was to distribute the announcement to applicable organizations. During May of 2015, it went out to the following groups: ⢠Association of Metropolitan Planning Organizations (AMPO)âelectronic newsletter; ⢠APTAâdistributed to bus and rail transit committees; ⢠Project Panel for TCRP Project HÂ50; and ⢠Standing committees of TRB, who distributed it to their members and friends listsâ â ADD10 Committee on Transportation and Economic Development, â ADD30 Committee on Transportation and Land Use, â APO28 Committee on Public Transportation Planning and Development, â APO65 Committee on Rail Transportation System, and â APO45 Committee on Intermodal Transfer Facilities. The announcement was also forwarded by a panel member to FTA. Altogether, 61 nominations were received from a wide variety of respondents, including a list from FTA. Case Selection Step 3: Review of Nominated Case Studies The third step was to subject the 61 nominated case study projects to a formal review process in order to identify a short list of cases that are most relevant for this study. This involved exam ination of the extent to which the nominated cases met specified selection criteria and appeared to have economic impacts that could be measured. There were five elements to this review: 1. Check for Project Dates. While the formal announcement asked for projects completed between 2000 and 2010, the Figure 1. Announcement of case nomination need. Seeking Case Study Nominations: Transit Improvements that Trigger Economic Development APTA and TCRP (under Project H-50) are developing a pilot database of case studies documenting the actual economic development impacts of transit investments. This project will complement a similar set of highway economic impact case studies developed for SHRP2, called TPICS. Verifiable examples of actual, observed impacts are a key part of this project. We are looking for suggestions or nominations of potentially relevant case studies, which: involve projects completed no earlier than 2000 and no later than 2010 involved a project investment of at least $5 million had localized economic development occur (regardless of the catalysts for that investment and regardless of whether the project has been studied before for any purpose) have local agencies or individuals who can be interviewed regarding the project history and any economic development that followed the transit investment.

9 Another three station construction projects were deleted from further consideration because there was evidence indi cating that relatively little development had occurred to date within their vicinity. Again, they may still be reasonable can didates for a broader TPICS for Transit, but those cases would not be able to showcase the value of inÂdepth case study analy sis in this pilot demonstration. (See Chapter 5 for further dis cussion of sampling issues relevant to full rollÂout of the case study database for transit.) Table 1 presents the 27 identified candidate projects that emerged from the case study nomination and review process, along with information on mode, location, timing, and cost. All 27 of these projects were considered good candidates for a fully developed TPICS for Transit system. Case Selection Step 4: Refinement of a Short List for Case Study Development The fourth and final step was to analyze the 27 remain ing transit projects in terms of their mix of project type, regional location, market setting, and project cost, as well transportation impacts, which make local economic impact measurement difficult. Hence, they are not con ducive for pilot case study examples. These include proj ects involving wideÂarea or systemÂwide reconstruction or upgrades of equipment. In those cases, there was no single location in which the improvements were focused and, therefore, no specific area where economic devel opment impacts would be most likely to occur. Another three projects were deleted from further consideration for that reason. 5. Check for Economic Impact. Of the remaining case study nominations, six more were removed from the list because their impact was primarily residential development with only small neighborhood retail activity. Only projects that had observable job and income effects (e.g., office, medical, or industrial activity impacts) were considered for the pilot case study examples. The reason was to main tain consistency with the original focus of the TPICS for Highways database, which sought to measure economic development impactsâthat is, job and worker income generation. Table 1. List of 27 finalist candidate projects, with descriptive information. Project Name Mode City State Comple on Year Cost ($Ms) Central Phoenix LRT Corridor LRT Phoenix AZ 2008 $1,400 Orange Line BRT BRT Los Angeles CA 2005 $324 BART to Airport HRT San Francisco CA 2003 $1,483 Mission Valley East Extension LRT San Diego CA 2005 $506 North Hollywood Extension HRT Los Angeles CA 2000 $1,310 Denver Southwest LRT LRT Denver CO 2000 $177 WMATA Branch Ave Extension HRT Washington DC 2001 $900 WMATA Largo Extension HRT Washington DC 2004 $607 NoMa Gallaudet Red Line Sta on HRT Washington DC 2004 $104 Atlanta North Line Extension HRT Atlanta GA 2000 $463 Boston Silver Line BRT Boston MA 2004 $374 Hiawatha Corridor LRT Minneapolis MN 2004 $715 LYNX Blue Line LRT Charlo e NC 2007 $427 Hudson Bergen LRT LRT Jersey City NJ 2000 $2,200 Riverline LRT LRT Trenton NJ 2004 $1,100 Atlan c Terminal refurbishment LRT, HRT,BRT, Bus Brooklyn NY 2010 $108 Euclid Corridor BRT Cleveland OH 2007 $200 EmX Phase I BRT BRT Eugene OR 2007 $25 Interstate MAX LRT Portland OR 2004 $350 Gateway Transit Center LRT Portland OR 2006 $32 Tren Urbano HRT San Juan PR 2004 $2,280 North Central Corridor LRT Dallas TX 2002 $120 Green Line Downtown Plan Bus Atlanta GA 2002 $6 Dallas Area Rapid Transit (DART) LRT Plano TX 2002 $63 Univ. & Med Ctr. TRAX Extension LRT Salt Lake City UT 2002 $238 St. Louis/St. Clair MetroLink Extension LRT St. Louis MO 2001 $339 Kent Sta on & Retail HRT Kent WA 2001 Note: LRT = light rail transit, HRT = heavy rail transit, BRT = bus rapid transit.

10 ⢠Mix of regions: MidÂAtlantic/Northeast (2), Great Lakes/ Plains (1), Rockies/West (3), Southwest (0), and South east (1). Table 2 provides the list of the 7 projects with relevant characteristics. 2.2 Types of Projects Covered Transit cases required a different project type framework than the highway cases in the original TPICS database. The classifications described here were used during the case screen ing process as well as implemented for the online database. The new TPICS for Transit was designed to cover transit lines, transit stations, and transit service enhancements. They were classified by four modal groups: bus, BRT, LRT, and HRT. They were also classified by four operational categories: (1) opening of new line or service, (2) extension of existing line or ser vice, (3) new terminal facility, and (4) service improvement. This makes for 16 possible classification categories as shown in Table 3. (See Chapter 5 for discussion of possibilities for inclusion of additional types of transit projects in a full roll out of the case study database for transit.) These categories serve to guide users seeking to select case studies that are relevant to them. Each of the 16 categories should eventually have at least 5 cases for viewing and com paring results within the category. While it is easy to proliferate categories by defining additional dimensions or finer distinc tions among cases, it would be counterproductive because it would increase the likelihood that a user searching for relevant cases would come up with few or zero matching cases. There is no overlap between the new transit categories and the old highway categories with the exception of a highway project category called âintermodal road/transit terminalsââ which covers projects that could also be used within an expanded transit case study database. as the existence of prior research documenting at least some aspect of their economic impact. Sections 2.2 and 2.3 discuss the types of projects and locations and settings that are covered by TPICS for Transit. Overall, the 27 projects show that there was some repre sentation by all types of modes (bus, bus rapid transit [BRT], light rail transit [LRT], and heavy rail transit [HRT]), among all regions of the United States, across a range of regions and mar kets, and with a wide range of costs. However, there was par ticularly strong representation by light rail projects (accounting for 50% of projects), and particularly weak representation by busÂonly projects (only two projects). The study team sought to identify a short list of cases that would be most likely to be successful in terms of impact mea surement while preserving a reasonable mix of project types and locations. Preliminary research was conducted to deter mine the extent to which there are past studies that have already identified economic and/or development impacts. While there is no requirement that information be available from prior studies, the existence of previously collected information does indicate that the pilot case study effort is most likely to be suc cessful in assembling impact data and generating an interest ing story. That is a consideration when only a small number of illustrative cases are to be completed for this pilot demonstra tion. Eleven projects were eliminated because no prior impact information was located. Based on this review, 7 cases were selected; 6 from the 16 remaining cases and 1 project that was identified after the review process. These recommended projects were selected because (a) they all have employment or development impact information already available, and most have both, and (b) they represent a broad and even mix of project types and locations: ⢠Mix of mode types: BRT (3), LRT (1), and HRT (3); ⢠Mix of investment types: new service (3), line exten sion (2), station facility (2); and Table 2. Projects selected for case studies. Project Name Mode* City State Year Completed Cost ($Ms) Investment Type Arapahoe at Village Center LRT Greenwood Village CO 2006 $18 Station Los Angeles Orange Line BRT BRT Los Angeles CA 2005 $305 New Service BART Extension to Airport HRT San Francisco CA 2003 $1,552 Extension NoMa Gallaudet Red Line HRT Washington DC 2004 $120 Station Atlanta North Line Extension HRT Atlanta GA 2000 $463 Extension Boston Silver Line BRT BRT Boston MA 2005 $625 New Service HealthLine/Euclid Corridor BRT Cleveland OH 2007 $200 New Service Note: LRT = light rail transit, HRT = heavy rail transit, BRT = bus rapid transit.

11 of regions used was reduced to five by creating three combined regions: Rockies/West, Great Lakes/Plains, and MidÂAtlantic/ Northeast. The description in Impact Area is flexible and pro vides additional information on local area of impact for transit cases compared with the county perspective used for highways. Market Setting The market context of a projectâs location can be an impor tant impact factor because the size of the market served by a given project would be expected to influence the magnitude of its economic impact. Market size is reflected in the definition of a Metropolitan Statistical Area (MSA) concept as defined by the U.S. Office of Management and Budget and adopted by the U.S. Census. Every county that is part of an urban area with 50,000 or more inhabitants and is connected economi cally to the surrounding area (based on commuting patterns) is classified as part of a metropolitan area. While the county level of analysis was appropriate for highway impact analyses for identifying Urban/Class Levels in TPICS for Highways, the study team determined that this would not be appropriate for transit projects. Given that the spatial scale of a county is relatively large in comparison with a transit system, narrowed criteria were added for this study so that project locations 2.3 Classification of Project Settings The case studies for both highway and transit projects share a common set of project descriptor variables, as shown in Table 4. The differences are minor and basically limited changing impact area descriptors and activity level measures to be relevant for transit projects. Construction and Analysis Periods An initial study date was chosen to be 1 year before the construction start date. If the construction period was very long and data availability was significantly better for a differ ent year near the time construction was initiated, this year was substituted. This year affected the collection of setting data and preÂproject conditions. The postÂconstruction study date was selected to be as recent as data availability allowed to best correspond with impact information collected in interviews. Location Regions are defined on the basis of the U.S. Department of Commerceâs Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA) regionsâ which divides the United States into eight regions. The number Table 3. Transit projects types and modes for transit cases. Project Type Mode New Service Extension of Line Terminal Facility Service Improvement Bus Bus Rapid Transit Light Rail Transit Heavy Rail Transit Table 4. Case study project information elementsâdescriptors. Case Study Data Existing Highway TPICS New Transit TPICS Analysis Period Initial Study Date and Post Construction Study Data Same Construction Period Start and End Years, Months Duration Same Project Location Impact Area (County), City, State, Region, Latitude & Longitude Same, except impact area is a sub-county area Market Setting Market Size, Urban/Class Level, Airport Travel Distance Same Socio-economic Setting Population Density, Population Growth Rate, Employment Growth Rate and Distress Level* Same Project Cost Planned Capital Cost (YOE$s), Actual Capital Cost (YOE$s), Actual Capital Cost (constant $s) Same Project Size Length (miles) (not applicable for interchanges) Same (not applicable for stations) Activity Level Average Daily Traffic Average Weekday Riders * Note that a lower distress level indicates an improved economic condition.

12 factors that aided or impeded the project timeline, cost, or impact; 2. Project typeâbus, BRT, heavy rail (commuter or inter city), or light rail or new service, service extension, expan sion, or operational improvement; 3. Location typeâmunicipality, neighborhood; 4. Project motivationâe.g., urban growth management, job access, air quality nonÂcompliance, and congestion mitigation; 5. Project costâplanned if available; 6. Construction periodâstart and end years; 7. Project sizeâpassenger volume and capacity; 8. Transportation characteristics and impactsâpre/post transit system characteristics by mode, pre/post change in passenger volume and/or passengerÂmiles, comparison with previous modal options, if relevant; 9. Photo of the transportation facilitiesâif available; and 10. Suggested other contacts. In addition to local transit agency contacts, information was obtained or corroborated using FTA documents and the National Transit Database. (Note that the FTA is now compiling pre/post data on new starts, see www.fta.dot.gov/12907_9197.) Data Collection Step 2: Project Setting and Development Process Available public data sources were examined to obtain empir ical data (when available) to prove context and backÂup the reported effects. The research analyst identified and attempted to contact at least three local informants: for example, a repre sentative of the local planning department, for the Chamber of Commerce, and for the economic development agency. Three perspectives were obtained to support completeness of data col lection and enable a âtriangulationâ of the appropriate valu ation of the projectâs role in affecting the observed economic and development outcomes. The following was collected: 11. Location settingâarea population level, density, employ ment, distress; could be classified as either within a âPrincipal Cityâ or the suburban part of the MSA. Socio-economic Setting The economic distress metric used for this project is one of relative position in the initial study year (the year before project construction commenced). It is defined as the ratio of local unemployment to the U.S. level and must be at least 20% higher than that average to count as economically distressed. The 20% criterion was selected by the analysis team after observing that some counties have borderline conditions and flip back and forth between the distress and nonÂdistressed categories from year to year. This helps to avoid distress classi fication changes associated with economic booms and down turns. Growth rates are calculated for the 5 years preceding the study period to provide context on the situation leading up to the project. 2.4 Information Collection Process Case studies required both empirical data and interview data to be compiled for the previously described settings and project characteristics data and the additional case study components of the TPICS databases listed in Table 5. The process for data collection had three major steps. Data Collection Step 1: Basic Project Description The research analyst reviewed existing published informa tion on the project to collect basic information and to gain some understanding to the project context. The analyst then contacted the transit agency (with a referral from APTA) to assemble additional details about the project. In some cases, this was referred to local planning department staff. The fol lowing is collected: 1. Description of projectâshort narrative, including name of project sponsoring agency and identification of Case Study Data Existing Highway TPICS New Transit TPICS Project Narrative Project motivation, history, impact factors, project role in outcomes <same> Further Documents Attachments and URL for external docs <same> Case Study Authorship Author name, organization, date <same> Pre/Post Conditions Local (municipal), county & state socio-economics Local (zipcode-based), county & state socio-economics, plus transportation conditions Project Impacts Direct and indirect economic impacts Direct impacts only Table 5. Case study project information elementsâanalysis.

13 All transit impacts were documented in immediate station areas. A buffer distance was not predetermined to apply to all projects so that local context could be considered. Impact col lection for TPICS for Transit relied more on interviews with local contacts and local sources than highway case studies because of the geographic scale of the cases. Because of the small geographies involved, little data is available through nationally available public sources that could be consistently used across projects. While highway projects utilized national databases to estimate impacts, for transit cases, this informa tion was only used to describe for pre/post conditions and not attributed to the project unless local sources specifically corroborated effects. The highway cases utilized countyÂlevel economic multi pliers that reflect wider regional impacts of major projects on business suppliers and worker income reÂspending. The transit project cases do not use these factors to estimate indirect effects. The reason that these were excluded is that the transit projects are typically at a smaller scale than highways and are not neces sarily expected to have major impacts at a countyÂwide level. Because of the subÂcounty nature of most transit impacts, we did not utilize IMPLAN data to calculate project specific impacts on wages and business sales, but included this infor mation in the requests from local contacts. This led to fewer of the transit studies including this impact category. Project Documentation The research analysts assembled information from Steps 1 through 3 to prepare a succinct narrative concerning the project. Following the format of TPICS for highways, the case study documentation is be organized into six sections, including the narrative and ⢠Project Characteristicsâpreceding Items 1â7, ⢠Project Settingâpreceding Item 11, 12. Pre/post economic statisticsâpre/post change in employment, wages, business sales, property values, tax revenuesâbased on published databases; 13. Observed economic and development impactsâ attributable to the project (same items as 12. Pre/post economic statistics above, plus observed square feet of development or private investment $); 14. Perception of the transit projectâs roleâin causing the observed economic and development impacts; 15. Identification of factorsâthat aided or impeded the project timeline, cost, or observed economic and devel opment impacts; and 16. Photos of development around the project siteâif available. In addition to local planners, business groups, and eco nomic development agents, speaking to specific businesses and other government agencies such as departments of rev enue was sometimes helpful. Significant portions of setting and economic data were obtained from national data sources such as the Census Bureau, Bureau of Economic Analysis, and Bureau of Labor Statistics. Specific data products include the County Business Patternâs zipcodeÂbased tabulations; BEAâs CA1, CA4, and CA25N Reports; the Statistics of U.S. Busi nesses; the Census of Governmentâs State and Local Finance information; and the Local Area Unemployment Statistics series from BLS. Data Collection Step 3: Impact Analysis The impact measures for transit projects are confined to the direct developmentâinduced changes, and reflect outcomes that are attributable to the projects as shown in Table 6. It is also important to note that the relevance of the various impact measures listed below, and the capability to effectively mea sure them varies depending on the scale of the project. Table 6. Case study economic impact measures. Outcome Measure Existing Highway TPICS New Transit TPICS Direct Employment Effect Change in direct jobs at project site and vicinity <same> Direct Economy Effect Change in wages & business sales calculated using IMPLAN data, or from local sources <same> Regional Economy Indirect impact multipliers (county level) -- Not applicable -- Private Investment Added sq. ft. of development, or $ of private investment in development <same> Capitalization of Private investment Change in property values <same> Fiscal Impact of Private Investment Change in state & local tax revenue generated in this area <same> Attribution of Credit to the Project % share of impact that is attributable to the project <same>

14 the role any of the projects has had on increasing transit use may help in gauging its importance with regard to develop ment. Many of these projects also provided major transporta tion efficiency benefits that were not a focus of the case studies. The BART extension to SFO, for example, serves a very high volume of travelers between the airport and other parts of San Francisco, saving people time, money, and hassle. However, these users provided little or no development impetus in the area around the new stations and, consequently, any economic impact related to their use was difficult to capture and beyond the scope of these case studies. Using station entrances and exits at new locations can provide good insight into the eco nomic role of a station in attracting new residents or employees, except in cases where stations have high numbers of transfers from outside the system, such as at SFO or when a station has significant parkÂandÂride volumes. The study team accord ingly focused on station area ridership counts and only made use of line ridership numbers for those cases that involved a new line with new stations. Table 8 provides an overview of the economic develop ment impacts of these seven pilot projects. Through research and interviews, nearby development projects were identified. When possible, the researchers used interviews to ascertain the portion of permanent employment change that was considered to be attributable to the transit project. Overall Findings Overall, the case studies showed wide variation in the num ber of jobs that were attributable to the transit projects and development around it. The most significant development and new employment following the opening of transit facili ties is seen in the NoMa Station and Boston Silver Line cases, where transit service improved access to underdeveloped land close to urban cores that would not have been able to develop as densely if they relied only on private vehicle commuting. Much less significant development occurred around stations and lines that passed through already developed residential ⢠Project Impactsâpreceding Items 13 and 14, ⢠Pre/Post Conditionsâpreceding Items 8 and 12, and ⢠Project Imagesâpreceding Items 9 and 16. The narrative contains the names of the Research Analyst, Organization, Interview Informants, and external documents used and provides related web links and/or document attach ments. The next section reviews the online database in which cases are documented. 2.5 Case Study Results Site-Specific Findings Results of the seven pilot case studies are shown in full in Appendix C. A brief summary of key findings is provided here. In general, the case studies focused on measuring the economic development of areas adjacent to the transit sys tem investment sites or corridors. The focus was specifically on identifying the extent to which new jobs emerged (and new development occurred) in station areas that can reason ably be linked to new transit service. An effort was made to adjust the job impact estimates to net out effects of other fac tors that may have also helped generate employment in the station vicinity. The job numbers were also defined to ignore temporary infrastructure jobs, and they focused specifically on direct effectsâthat is, they did not account for multi plier effects such as additional indirect (supplier) or induced (worker spending) impacts on jobs in a broader surrounding region. Displacement effects (spatial relocations of business) occurring within walking distance of a transit station were netted out of the totals, although it was not possible to fully account for broader spatial shifts. Other real estate investment developments (usually a precursor to some if not all the job attraction) were also investigated and, when possible, data on dollars of investment and property values was also compiled. Table 7 provides information on transit facility utilization for the seven pilot projects in order to offer some perspective on the transportation impacts of the projects. Understanding Table 7. Transit facility utilization. Project Name Previous Local Service Volume Impact at Completion Most Recent Utilization Volume Arapahoe at Village Center 13,350 (1) 20,350 (1) Los Angeles Orange Line BRT 22,000 (3) 28,000 (3) BART Extension to Airport 3,000 (2) 8,000 (2) 21,000 (2) NoMa-Gallaudet Red Line 0 (4) 2,000 (2) 9,000 (2) Atlanta North Line Extension 8,750 (1) Boston Silver Line BRT 0 (4) 3,650 (3) 16,000 (3) HealthLine/Euclid Corridor 9,000 (3) 12,500 (3) 16,000 (3) Notes: (1) station daily entrances; (2) station daily exits; (3) line daily ridership; (4) local bus routes are busier today than prior to improvements, but are excluded from utilization figures for new facilities.

15 examples of multiple strengths. Not surprisingly, some char acteristics are correlated; for instance, a supportive business community is likely to be able to encourage more open zoning rules. Key observations are as follows: ⢠A supportive business community can have an impor- tant influence on obtaining the maximum economic value from the transit investment. The NoMaâGallaudet station in Washington, D.C., provides a clear example. Busi ness development organizations in this closeÂin region not far from Union Station were able to make a strong case for WMATA to add an inner city station at a time when the region was focused on a rail extension to Dulles Air port and the outer suburbs. The federal government also took advantage of the new station to locate some offices. Similar examples of strong business support can be found in Denver where the TÂRex project was built to provide service to the regionâs Tech Center. Clevelandâs HealthLine along Euclid Avenue got its name from the hospital and health center at one end of the line rather than the origi nally proposed generic name of the Silver Line. This helped promote the major business activities located along the line and served to differentiate the operation from other transit services. In Atlanta, the business community in and around the Perimeter Center was a strong advocate for the extension of MARTA. ⢠Zoning flexibility can be key and was mentioned in most of the case studies, including Atlanta; Washington, D.C.; Cleveland; and Denver. Of course, a successful zoning strategy also requires underlying development demand. ⢠Connections to the rest of the regional transportation network can also be important. The ability to provide access across the region adds important potential develop ment energy. These connections need not rely exclusively on transit, however. Denverâs TÂRex included roadway improvements as well as a âcall and rideâ service to improve last mile access to the light rail line. Atlantaâs transit con nection to the Perimeter Center also benefited from nearby highway improvements. areas, such as the Los Angeles Orange Line and San Francisco BART airport extension. The HealthLine is part of a larger effort to revitalize inner city Cleveland that has increased its impact. The Arapahoe at Village Center Station, like the Atlanta North Line Extensionâs two stations, largely serves corporate campus style office facilities on the urban fringe, which results in lower total development figures than transit services in denser parts of metro areas. A crowded commercial real estate market in D.C. also encouraged development around the NoMa Station, whereas consistent double digit vacancy rates in places like L.A. postÂproject slowed the demand for new commercial properties around stations. The recession in 2008 appears to have seriously slowed the development impacts of many of the studied transit projects. Even in areas such as the NoMa neighborhood where these effects were less pronounced, only half of planned develop ment has been completed in the 11 years since the station opened. This indicates that impacts may continue to grow into future years as planned projects âcome off hold.â Fifteen years after the completion of Atlantaâs North Line Extension, companies continue to cite transit access as an important fac tor in their decisions to locate in Sandy Springs, Georgiaâ the city served by the new stations. Studying the economic development impact of transit is challenging because, in one sense, development may be most clearly considered a direct result of infrastructure improve ments if they occur within walking distance of stations, which is why a ¼Âmile radius was typically considered. This guide line does not, however, preclude the potential for some tran sit investments to support or enable development benefits in locales elsewhere in the transit network, particularly insofar as the transit projects enhance connectivity and access to wider neighborhoods. Factors Affecting Local Development Impacts No single characteristic guarantees a strong positive eco nomic impact. Indeed, most of these case studies provide Table 8. Economic development impacts. Project Name Major Economic Sectors Affected Nearby Devel. (Sq. Ft.) Jobs Attracted Arapahoe at Village Center High Tech and Financial 775,000 1,005 Los Angeles Orange Line BRT Retail 1,300,000 825 BART Extension to Airport Services and Visitors None observed 0 NoMa Gallaudet Red Line Fed & Non-Profit Office 8,000,000 10,000 Atlanta North Line Extension Corporate Headquarters 500,000 750 Boston Silver Line BRT Class A Office 10,000,000 3,350 HealthLine/Euclid Corridor Healthcare, Education 380,000 1,360 Notes: (1) station daily entrances; (2) station daily exits; (3) line daily ridership; (4) local bus routes are busier today than prior to improvements, but are excluded from utilization figures for new facilities.

16 actually occur. They also show that economic development impacts are not always correlated with ridership changes. For instance, some projects with relatively high ridership (e.g., Los Angeles Orange Line and San Francisco BART to Air port) had relatively little immediate economic development impact, while others with lower ridership had more economic development impact (e.g., Washingtonâs NoMaâGallaudet Station). The implication is that project impacts can look dif ferent depending on whether one focuses on ridership out comes, on economic development outcomes, or both. A much stronger and more nuanced base of insights will be gained as a broader set of case studies becomes completed later on. The next two chapters lay out the database, web tool design, and data collection processes that can be utilized to enable the assembly and use of a broader set of case studies in the future. Factors that slowed economic development impacts were the lack of conditions identified above as helping to stimu late local developmentâfor example, there was a lack of local business interest in redeveloping areas surrounding new sta tions located along the BART line to San Francisco airport and the Orange Line in Los Angeles. In the latter case, strong local preference to continue the current style of suburban residen tial housing led to a focus of development opportunities at the existing business centers at either end of the line (rather than along the middle of the line). Altogether, these types of case study observations serve to provide both planners and interested stakeholders with a dose of realityâportraying both the opportunities to make a dif ference in economic development and the factors that must realistically be confronted to make desired new development

Welcome to OpenBook!

You're looking at OpenBook, NAP.edu's online reading room since 1999. Based on feedback from you, our users, we've made some improvements that make it easier than ever to read thousands of publications on our website.

Do you want to take a quick tour of the OpenBook's features?

Show this book's table of contents , where you can jump to any chapter by name.

...or use these buttons to go back to the previous chapter or skip to the next one.

Jump up to the previous page or down to the next one. Also, you can type in a page number and press Enter to go directly to that page in the book.

To search the entire text of this book, type in your search term here and press Enter .

Share a link to this book page on your preferred social network or via email.

View our suggested citation for this chapter.

Ready to take your reading offline? Click here to buy this book in print or download it as a free PDF, if available.

Get Email Updates

Do you enjoy reading reports from the Academies online for free ? Sign up for email notifications and we'll let you know about new publications in your areas of interest when they're released.

Browser does not support script.

- Events and Seminars

Impact Case Studies

Impact case study: Improving the lives of the ultra-poor

Summary: Researchers at LSE provided robust evidence that large, one-off interventions can produce sustainable economic benefits for individuals, improving the lives of people in extreme poverty. Read the impact case study .

Professor Oriana Bandiera Professor of Economics | Sir Anthony Atkinson Chair in Economics

Professor Robin Burgess Professor of Economics | Director of IGC

Impact case study: State capacity: crafting effective development strategies Summary: LSE research has made a significant contribution to understanding state development and the causes of state fragility, shaping the work of multilateral development agencies. Read the impact case study .

Professor Sir Tim Besley School Professor of Economics and Political Science

Impact case study: Understanding and improving subjective wellbeing

Summary: LSE research has significantly contributed to promoting subjective wellbeing as a central objective of public policy, and provided new tools to support its measurement. Read the impact case study .

Professor Lord Richard Layard Emeritus Professor of Economics | Community Wellbeing Programme Co-Director

Professor Paul Dolan Professor of Behavioural Science

Impact case study: Supporting the development of a safer, more robust financial system for the eurozone

Summary: In response to the eurozone crisis, LSE economists co-developed an influential proposal for European Safe Bonds (ESBies), which would protect the financial system from future shocks. Read the impact case study .

Professor Ricardo Reis Arthur Williams Phillips Professor of Economics

Professor Dimitri Vayanos Professor of Finance | Director, Financial Markets Group

Impact case study: Improving productivity through better management practices

Summary: LSE research has demonstrated how management practices affect productivity, providing vital evidence for designing industrial strategies to tackle low productivity. Read the impact case study .

Professor John Van Reenen Ronald Coase Chair in Economics and School Professor

Professor Nicholas Bloom Stanford Institute for Economic Policy Research

Professor Raffaella Sadun Harvard Business School

Knowledge Exchange and Impact (KEI) LSE's guidance for engaging non-academic audiences with research

Do Your Students Know How to Analyze a Case—Really?

Explore more.

- Case Teaching

- Student Engagement

J ust as actors, athletes, and musicians spend thousands of hours practicing their craft, business students benefit from practicing their critical-thinking and decision-making skills. Students, however, often have limited exposure to real-world problem-solving scenarios; they need more opportunities to practice tackling tough business problems and deciding on—and executing—the best solutions.

To ensure students have ample opportunity to develop these critical-thinking and decision-making skills, we believe business faculty should shift from teaching mostly principles and ideas to mostly applications and practices. And in doing so, they should emphasize the case method, which simulates real-world management challenges and opportunities for students.

To help educators facilitate this shift and help students get the most out of case-based learning, we have developed a framework for analyzing cases. We call it PACADI (Problem, Alternatives, Criteria, Analysis, Decision, Implementation); it can improve learning outcomes by helping students better solve and analyze business problems, make decisions, and develop and implement strategy. Here, we’ll explain why we developed this framework, how it works, and what makes it an effective learning tool.

The Case for Cases: Helping Students Think Critically

Business students must develop critical-thinking and analytical skills, which are essential to their ability to make good decisions in functional areas such as marketing, finance, operations, and information technology, as well as to understand the relationships among these functions. For example, the decisions a marketing manager must make include strategic planning (segments, products, and channels); execution (digital messaging, media, branding, budgets, and pricing); and operations (integrated communications and technologies), as well as how to implement decisions across functional areas.

Faculty can use many types of cases to help students develop these skills. These include the prototypical “paper cases”; live cases , which feature guest lecturers such as entrepreneurs or corporate leaders and on-site visits; and multimedia cases , which immerse students into real situations. Most cases feature an explicit or implicit decision that a protagonist—whether it is an individual, a group, or an organization—must make.

For students new to learning by the case method—and even for those with case experience—some common issues can emerge; these issues can sometimes be a barrier for educators looking to ensure the best possible outcomes in their case classrooms. Unsure of how to dig into case analysis on their own, students may turn to the internet or rely on former students for “answers” to assigned cases. Or, when assigned to provide answers to assignment questions in teams, students might take a divide-and-conquer approach but not take the time to regroup and provide answers that are consistent with one other.

To help address these issues, which we commonly experienced in our classes, we wanted to provide our students with a more structured approach for how they analyze cases—and to really think about making decisions from the protagonists’ point of view. We developed the PACADI framework to address this need.

PACADI: A Six-Step Decision-Making Approach

The PACADI framework is a six-step decision-making approach that can be used in lieu of traditional end-of-case questions. It offers a structured, integrated, and iterative process that requires students to analyze case information, apply business concepts to derive valuable insights, and develop recommendations based on these insights.

Prior to beginning a PACADI assessment, which we’ll outline here, students should first prepare a two-paragraph summary—a situation analysis—that highlights the key case facts. Then, we task students with providing a five-page PACADI case analysis (excluding appendices) based on the following six steps.

Step 1: Problem definition. What is the major challenge, problem, opportunity, or decision that has to be made? If there is more than one problem, choose the most important one. Often when solving the key problem, other issues will surface and be addressed. The problem statement may be framed as a question; for example, How can brand X improve market share among millennials in Canada? Usually the problem statement has to be re-written several times during the analysis of a case as students peel back the layers of symptoms or causation.

Step 2: Alternatives. Identify in detail the strategic alternatives to address the problem; three to five options generally work best. Alternatives should be mutually exclusive, realistic, creative, and feasible given the constraints of the situation. Doing nothing or delaying the decision to a later date are not considered acceptable alternatives.

Step 3: Criteria. What are the key decision criteria that will guide decision-making? In a marketing course, for example, these may include relevant marketing criteria such as segmentation, positioning, advertising and sales, distribution, and pricing. Financial criteria useful in evaluating the alternatives should be included—for example, income statement variables, customer lifetime value, payback, etc. Students must discuss their rationale for selecting the decision criteria and the weights and importance for each factor.

Step 4: Analysis. Provide an in-depth analysis of each alternative based on the criteria chosen in step three. Decision tables using criteria as columns and alternatives as rows can be helpful. The pros and cons of the various choices as well as the short- and long-term implications of each may be evaluated. Best, worst, and most likely scenarios can also be insightful.

Step 5: Decision. Students propose their solution to the problem. This decision is justified based on an in-depth analysis. Explain why the recommendation made is the best fit for the criteria.

Step 6: Implementation plan. Sound business decisions may fail due to poor execution. To enhance the likeliness of a successful project outcome, students describe the key steps (activities) to implement the recommendation, timetable, projected costs, expected competitive reaction, success metrics, and risks in the plan.

“Students note that using the PACADI framework yields ‘aha moments’—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.”

PACADI’s Benefits: Meaningfully and Thoughtfully Applying Business Concepts

The PACADI framework covers all of the major elements of business decision-making, including implementation, which is often overlooked. By stepping through the whole framework, students apply relevant business concepts and solve management problems via a systematic, comprehensive approach; they’re far less likely to surface piecemeal responses.

As students explore each part of the framework, they may realize that they need to make changes to a previous step. For instance, when working on implementation, students may realize that the alternative they selected cannot be executed or will not be profitable, and thus need to rethink their decision. Or, they may discover that the criteria need to be revised since the list of decision factors they identified is incomplete (for example, the factors may explain key marketing concerns but fail to address relevant financial considerations) or is unrealistic (for example, they suggest a 25 percent increase in revenues without proposing an increased promotional budget).

In addition, the PACADI framework can be used alongside quantitative assignments, in-class exercises, and business and management simulations. The structured, multi-step decision framework encourages careful and sequential analysis to solve business problems. Incorporating PACADI as an overarching decision-making method across different projects will ultimately help students achieve desired learning outcomes. As a practical “beyond-the-classroom” tool, the PACADI framework is not a contrived course assignment; it reflects the decision-making approach that managers, executives, and entrepreneurs exercise daily. Case analysis introduces students to the real-world process of making business decisions quickly and correctly, often with limited information. This framework supplies an organized and disciplined process that students can readily defend in writing and in class discussions.

PACADI in Action: An Example

Here’s an example of how students used the PACADI framework for a recent case analysis on CVS, a large North American drugstore chain.

The CVS Prescription for Customer Value*

PACADI Stage

Summary Response

How should CVS Health evolve from the “drugstore of your neighborhood” to the “drugstore of your future”?

Alternatives

A1. Kaizen (continuous improvement)

A2. Product development

A3. Market development

A4. Personalization (micro-targeting)

Criteria (include weights)

C1. Customer value: service, quality, image, and price (40%)

C2. Customer obsession (20%)

C3. Growth through related businesses (20%)

C4. Customer retention and customer lifetime value (20%)

Each alternative was analyzed by each criterion using a Customer Value Assessment Tool

Alternative 4 (A4): Personalization was selected. This is operationalized via: segmentation—move toward segment-of-1 marketing; geodemographics and lifestyle emphasis; predictive data analysis; relationship marketing; people, principles, and supply chain management; and exceptional customer service.

Implementation

Partner with leading medical school

Curbside pick-up

Pet pharmacy

E-newsletter for customers and employees

Employee incentive program

CVS beauty days

Expand to Latin America and Caribbean

Healthier/happier corner

Holiday toy drives/community outreach

*Source: A. Weinstein, Y. Rodriguez, K. Sims, R. Vergara, “The CVS Prescription for Superior Customer Value—A Case Study,” Back to the Future: Revisiting the Foundations of Marketing from Society for Marketing Advances, West Palm Beach, FL (November 2, 2018).

Results of Using the PACADI Framework

When faculty members at our respective institutions at Nova Southeastern University (NSU) and the University of North Carolina Wilmington have used the PACADI framework, our classes have been more structured and engaging. Students vigorously debate each element of their decision and note that this framework yields an “aha moment”—they learned something surprising in the case that led them to think differently about the problem and their proposed solution.

These lively discussions enhance individual and collective learning. As one external metric of this improvement, we have observed a 2.5 percent increase in student case grade performance at NSU since this framework was introduced.

Tips to Get Started

The PACADI approach works well in in-person, online, and hybrid courses. This is particularly important as more universities have moved to remote learning options. Because students have varied educational and cultural backgrounds, work experience, and familiarity with case analysis, we recommend that faculty members have students work on their first case using this new framework in small teams (two or three students). Additional analyses should then be solo efforts.

To use PACADI effectively in your classroom, we suggest the following:

Advise your students that your course will stress critical thinking and decision-making skills, not just course concepts and theory.

Use a varied mix of case studies. As marketing professors, we often address consumer and business markets; goods, services, and digital commerce; domestic and global business; and small and large companies in a single MBA course.

As a starting point, provide a short explanation (about 20 to 30 minutes) of the PACADI framework with a focus on the conceptual elements. You can deliver this face to face or through videoconferencing.

Give students an opportunity to practice the case analysis methodology via an ungraded sample case study. Designate groups of five to seven students to discuss the case and the six steps in breakout sessions (in class or via Zoom).

Ensure case analyses are weighted heavily as a grading component. We suggest 30–50 percent of the overall course grade.

Once cases are graded, debrief with the class on what they did right and areas needing improvement (30- to 40-minute in-person or Zoom session).