- Prodigy Math

- Prodigy English

- Is a Premium Membership Worth It?

- Promote a Growth Mindset

- Help Your Child Who's Struggling with Math

- Parent's Guide to Prodigy

- Assessments

- Math Curriculum Coverage

- English Curriculum Coverage

- Game Portal

The 14 Most Effective Ways to Help Your Kids with Math

Written by Ashley Crowe

Help your child build essential math skills through an engaging fantasy video game!

- Parent Resources

- How to help kids with math at home

Making math homework challenging and fun

- Signs of math struggle

How Prodigy can help kids with math

Math can be a daunting subject. Not only does it cover a huge range of skills, but it’s also one of the few subjects where a strong understanding of the fundamentals is essential for future learning.

Math is taught differently now than when many parents were in school. There’s more focus on the basics, which is great (no, really, it is). But that can feel incredibly frustrating when you’re trying to help your child understand their math homework.

No matter your history with math, you can still help your child master mathematical concepts at home. And you may even have some lightbulb moments you missed in middle school.

Whether your child is struggling with math or wants to improve their skills, It’s time to ditch the math stress and tackle this subject together! Keep reading for our 14 best tips to help kids with math .

How to help kids with math at home (even if you hate math)

If you have a less than stellar math history, it’s okay! You can still help your child learn the math they need to succeed. Here’s how.

1. Maintain a positive attitude

A lot of kids (and adults) feel anxiety when presented with a math problem. But if your child is struggling with a concept, that doesn’t mean they’re bad at math. You’re not bad at math either!

Math is a skill that takes practice , just like any other. You’ll learn it, even if it’s confusing right now. This just means you don’t understand it yet.

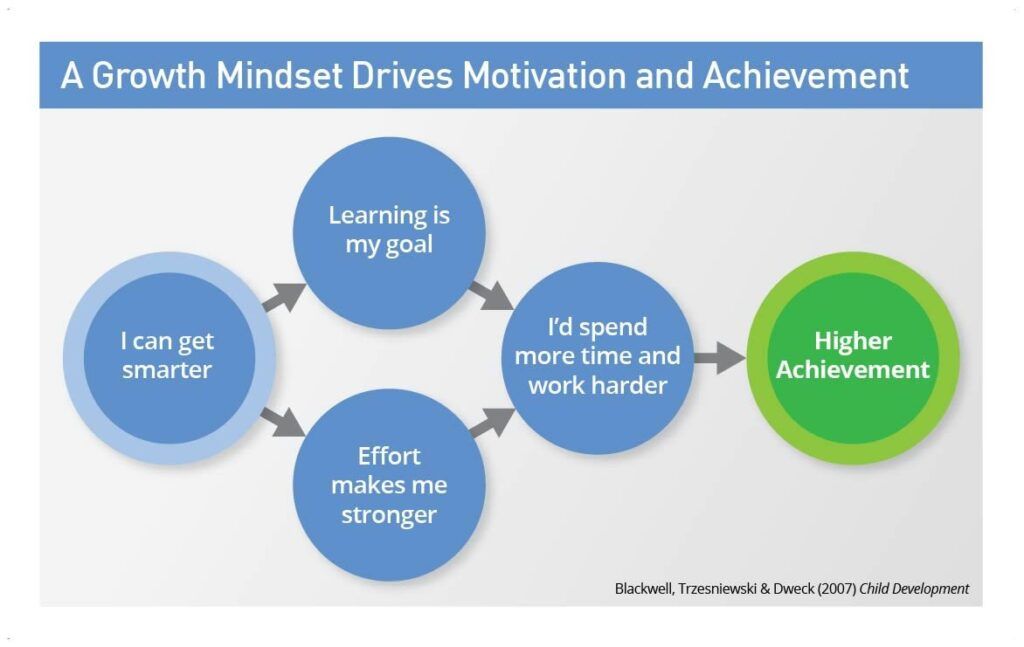

Encourage this attitude with your child to help them build their math confidence. They can grow into math understanding, but it takes time. Use a growth mindset approach and you’ll both be amazed at what you can learn.

2. Ask math questions that interest your child

Let’s face it — some math can be boring. If your kid doesn’t care much about trains, why should they care about how fast they’re going or where they’ll meet? Instead of pushing them to answer these standard questions, ask them about what they’re actually interested in .

Math is everywhere. You’ll find mathematical relationships throughout nature. Your child can discover angles and physics while jumping toy monster trucks. Or they can explore measurements while baking or doing crafts .

Find numbers in what they already love and watch their interest in math grow!

3. Encourage communication

Your kid can talk your ear off about their favorite Roblox game, but when it comes to school questions, they shut down. That’s normal, but it can also make it difficult to keep up with their studies.

When possible, try to open up some judgement-free conversations about math . Ask how it’s going and if they feel good about their new lessons. Don’t jump in and try to solve their problems right away. And be careful about remarks like, “oh, that’s easy”. If they talk, just listen.

If your child is reluctant to share, check in with their teacher. Ask about the topics they’re studying and how you can help. Then, use these insights to get the conversation going at home.

4. Be patient and take it slow

Math builds on itself, but that means it can be tricky to keep up if your child is struggling with a new concept. When this happens, slow down and back up. Don’t keep pushing new ideas until they understand the old ones.

This same advice works for you, too. Be patient with yourself — it’s been a while since you’ve learned 4th grade math, and the work may look a lot different now. But with some time and perseverance, you can help your child succeed.

5. Practice and refine math vocabulary

Math vocabulary is all around us, but that doesn’t mean we’re very comfortable with it. Try using math vocabulary in everyday language and it will slowly start feeling a lot less intimidating. Bring up percentages when you're shopping a sale, or talk about parts of a whole while cooking.

Of course, there are plenty of math words we don’t see everyday. Do you remember exponents, tangents, or the commutative property? If not, that’s totally okay! All you need is a refresher and some practice.

For example, when your child is studying areas, take some time to make sure you understand what you’re actually discovering. Understanding the bigger concept (calculating the amount of surface space vs just plugging in length and width) is what will bring those light bulb moments.

6. Show math in everyday life

We’ve said it before, but it’s worth repeating — math is everywhere. It’s probably not trigonometry or pre-calculus, but you’re doing math all the time. Pay attention and you’ll catch these math moments. When you do, share them with your child.

When kids are young, just counting or sorting is a great start. As they get older, look for math lessons while baking, shopping, playing games, or talking about money. Budgeting is a major life skill that uses so much math. Find these practical math moments and help your child see the value in a math education.

7. Get your child to teach you math

Math looks a little different now. If your kid’s homework is confusing for you, ask them to explain their process .

This is a great connecting moment to share with your child. And it can set you up to be a better helper if they run into frustration in later lessons.

8. Talk about math around the house

Seriously, math is everywhere. It’s true! And that means you’re not bad at math — you do it every day! Find places to use math around your house to help your child’s math abilities come to life.

Count the slices of pizza the next time you order out, then determine the percentage of pizza everyone has eaten. Get your little ones to help you sort socks. Talk about the probability of rolling an even number during your family night board game session. Look around and you’ll find tons of opportunities!

9. Use online math resources

If you have access to the internet, there’s always somewhere you can get all of your math questions answered.

There are many free learning resources, like those on the Prodigy blog . Give them a read and then explore math together with your child. There are always opportunities to learn something new online, especially when it comes to math!

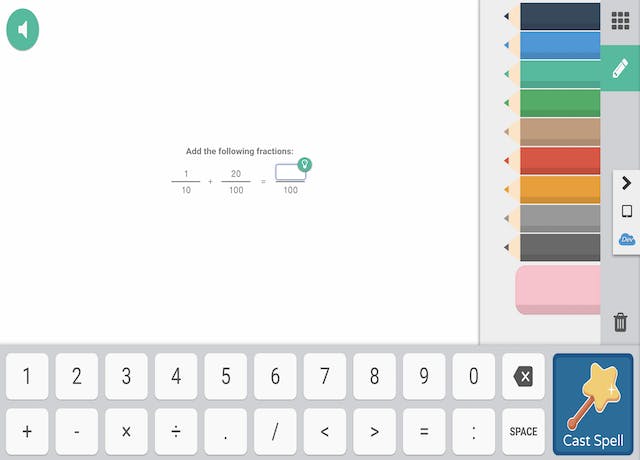

10. Try game-based learning

If you find your child getting frustrated, ditch the textbooks and worksheets and try something different.

Game-based learning is all the rage, and for good reason. Kids are naturally drawn to games , whether they’re cooperative board games or video games played on their tablets. Why? Because games are fun and exciting!

Game-based learning can take the stress out of math instruction. Kids can practice their math with just the right mix of the familiar and the challenging.

Prodigy Math , for example, is a game-based learning platform where players explore fantasy worlds, build characters and battle friends — all while answering curriculum-aligned math questions !

The adaptive algorithm always adjusts to math your child’s grade and skill level, so they can grow their math confidence while you take a homework break. And with your own parent account, you can support their learning and keep track of what they’re working on.

11. Join education-based parent groups

Looking for new and effective ways to help your child with their studies? Join some parent-led groups focused on education (try the Prodigy Parent Community on Facebook!). Online or local in-person groups are great for finding a variety of tips and tricks to help you help your child.

Homeschooling groups are a great place to start. Or ask other parents from your child’s class how they’re coping with the newest lesson. You can even use Instagram to find parent influencers sharing their best ideas for helping your child learn. Parents understand the struggle, and they’re here to help!

12. Keep the workspace neat and tidy

Where does your child do most of their homework?

If they’re working at the kitchen table, help them stay focused by removing distractions from the area. If they have their own desks, remind them to neaten it up every now and again. Math requires focus, and a cluttered space can lead to a distracted mind.

13. Provide homework help

It’s rare that a child loves doing homework. It’s already been a long day, and it’s understandable if they just want to get back to the things they love. If your child is really struggling with homework, offer to help!

It’s frustrating to look at the same problem over and over and never see the solution. That’s not helping them learn — it’s just breaking their confidence. Instead, step in with a fresh set of eyes and tackle it together. Talk through the problem and give a new perspective. It may be just what they need for their next “a-ha” moment.

14. Consider getting a math tutor

As your child moves into high school math courses, you may reach the end of your math comfort levels. In this case, look at your child’s math tutoring options.

Another student in class may do the trick. But if that’s not the right fit, find an experienced educator, whether you’re looking for in-person or online tutoring sessions . This may be just the thing your child needs to boost their academic confidence.

If your child barely makes it through their nightly math problems, look for ways to add a little fun to their practice.

Is there a way to relate their latest math lesson to one of their favorite things? For elementary students, think of beloved TV show characters or toys. Early math (like addition and subtraction) is easy to take off the page with their favorite toy collection. Create a set of rocks or stuffed animals. Then add, take away and sort.

Even high school math can be better understood using fun learning moments. Angles can be explored while playing a game of pool. Or throw a Pi day extravaganza, complete with delicious treats. Get creative, and be sure to celebrate their math wins along the way!

Look for signs of math struggle

It’s normal for your child to run into some difficulty in their math classes. Math is a complicated subject, and it can get very abstract at times. Encourage them to keep trying and use our tips above to help them along their learning journey.

But sometimes the struggle can build to a point where they may need additional help. Talk with your child’s teacher if you notice any of these signs of school struggle:

- Falling grades

- Loss of appetite

- Lack of communication

- Change in emotional state

- Lack of enthusiasm about school

Your child may not communicate the stress they feel, but try talking with them. They may have just fallen behind and have lost some of their confidence with math. Or it may be more than just math class affecting their mood. Open up communication to figure out the cause of their struggles, then brainstorm a solution plan together with their teacher.

Over the last couple of years, many have felt the pressure of trying to be both parent and teacher. If you find both you and your kids struggling with their math lessons, step back and try Prodigy Math.

This engaging learning platform can help you keep math learning fun and your child’s confidence high!

To them, it’s a fun video game they can enjoy during screen time. But while they’re enjoying the exciting world of Prodigy, they can practice math while you monitor their progress from the parent dashboard.

Prodigy meets your child where they are and keeps them on track with grade standards. No more butting heads or stressful kitchen table math lessons.

Give Prodigy Math a try today and take the stress out of your evenings!

clock This article was published more than 5 years ago

This is why it’s so hard to help with your kid’s math homework

Two years ago I walked into a car rental return center in Charlotte and interrupted Adrianette Felix mid-rant.

“I can’t even help my own child do her homework, it’s so frustrating, and I feel so stupid,” she said. “What kind of mother can’t understand first-grade math?”

Man needed help with son’s third-grade math homework and got it from a stranger on the subway

Felix and I spent the next half-hour engaged in a spirited discussion about the state of math education in America; how we got here, why it’s changed; and where experts on math education hope it’s taking us.

The simple answer to why math education has changed, “Common Core State Standards,” is only part of the story. Math teacher Christopher Danielson outlines the rest of the story in his book, “ Common Core Math for Parents for Dummies ,” and it goes something like this: Math education in America has evolved in response to concerns about our international competitiveness, first with Europe, and later, with Russia and its space program. Consequently, American math education prioritized the education of professional scientists and mathematicians who could get satellites in orbit and send men to the moon.

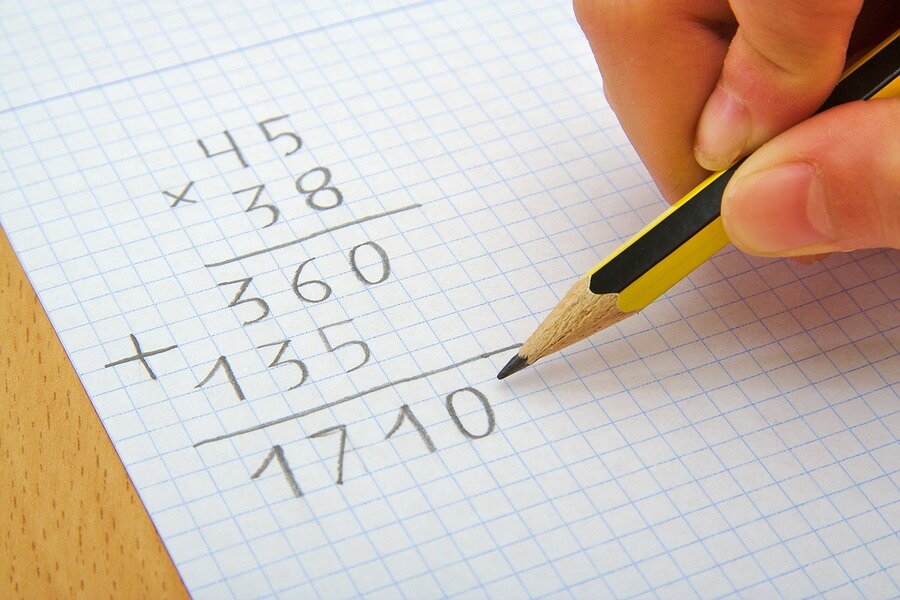

While we were busy chasing those lofty goals, we failed to educate most students in the basic foundations of math. To rectify this, the education pendulum swung back in the other direction, toward rote memorization. Cue the era of multiplication-table work sheets and timed math facts, tasks that still make up the bulk of elementary school math homework assignments.

The summer conundrum: Fight brain drain or give the kids a break?

Between 1989 and 2009, in large part because of the advent of No Child Left Behind , state standards and the testing necessary to measure states’ progress, math education became what Danielson refers to as a “mile-wide, inch-deep curriculum.” We teach many topics in each grade but at a superficial level. Math education became a series of skills served up in bits and pieces but never as part of a unified, mathematical whole.

Notably, we failed to give American children math sense, a natural and instinctive dexterity with numbers.

I was one of those children, despite having been educated in the top-ranked public school district in Massachusetts ( Dover-Sherborn Regional High School ). My mathematical education was characterized by drills memorization and instructions to accept abstract axioms and mathematical order of operations as “simply how it’s done,” concepts, my teachers promised, I would understand later. I dutifully followed their directions, memorized the steps and regurgitated on demand, but the understanding I had been promised never materialized. What I got instead was a raging case of math anxiety and the belief that I am not a math person.

It wasn’t until my mid-40s, when I retook Algebra with my middle school students and a gifted educator, that I discovered the truth: I had not failed at math; my math education had failed me.

With rare exception, most American children still receive a similarly counterproductive math education, one that produces adults who can recite multiplication tables but can’t make change when the cash register isn’t working, let alone view math as poetry.

“The highest achieving kids in the world are the ones who see math as a big web of interconnected ideas, and the lowest achieving students in the world are the kids who take a memorization approach to math. The United States, you won’t be surprised to hear, has more memorizers than any country in the world,” said Jo Boaler , professor of mathematics education at Stanford University, in a phone interview.

This chopping up of mathematical concepts, asserts Boaler, is where American math education fails children, and why Felix gets frustrated by her daughter’s math homework. Felix learned how to memorize, while her daughter is learning something much more valuable and useful: number sense, relevance and mental flexibility.

When the average teacher has about 200 separate math concepts or skills to teach in a given year, the connections between each piece disappear. “The kids don’t get to see them, and most teachers don’t know about them, either,” Boaler says. “When teachers are armed with the research about brain growth and [the reality that] everybody can learn math, it changes what they do. Teachers that are empowered with this research are doing amazing things. Really amazing things.”

Math coach Tracy Zager agrees. “It’s a phenomenal time to be a math teacher. We are in a time of great revolution and excitement, moving away from rote memorization and toward an understanding of process. It doesn’t mean that answers don’t matter, and it doesn’t mean that skills and memorization don’t matter, but when a student does something wrong, we want them to understand why, ” she said in a phone interview.

In her book, “ Becoming the Math Teacher You Wish You’d Had ,” Zager writes, “Math is not about following directions, it’s about making new directions.” So I emailed her to ask about the direction she would take math education.

“We have to undertake the real work: high-quality, sustained, classroom-based professional development,” she said. “Doing it systematically would take money and time and belief in teachers as professionals.”

While teachers, administrators and education policymakers do battle over Zager’s question, Felix and her daughter need help today, with tonight’s homework assignment.

For that kind of practical advice, I returned to Danielson and his book, “Common Core for Math for Parents for Dummies.” Danielson suggests that parents stop giving kids easy answers and instead focus on asking these five essential questions:

- “Why?” and “How do you know?”

- “Is it good enough?”

- “Does this make sense?”

- “What’s going on here?”

The questions, “Why?” and “How do you know?” require children to construct arguments, to justify their answers and to think about the reasons their answer may be correct. It’s not enough to know that 8 + 4 = 12, as Danielson writes, students must be able to articulate how they might figure out the sum of 8 and 4 if they do not automatically know the answer.

“What if” is a fantastic question to ask in any context, but in math, it’s particularly important. “What if” is at the root of play, experimentation, innovation and exploration. “What if” allows us to push students to contemplate questions beyond their immediate understanding and can fuel curiosity, deeper learning and intellectual breakthroughs.

The question “Is it good enough” gets at the concepts of estimation and precision. Is it good enough to say that .99 repeating is close enough to 1 to say that they are equal? Asking this question requires that students pay attention to units and attend to precision both numerically and linguistically.

“Does this make sense?” is a great question to ask at every step of the process, from choosing a path forward (“Does it make sense to add here?”) to the final answer (“Does that answer make sense?”) and gives kids the opportunity to pause, take stock and exercise judgment. Sometimes, of course, the answer to this question is going to be, “No,” and wrong answers can be just as useful as the right ones, Danielson argues, because, “A classroom climate that only values right answers is less likely to encourage students to persevere.”

Finally, the question, “What’s going on here?” helps kids look for the underlying structure of a problem. For example, “If you know that n is a whole number, then 2 n is an even number and 2 n + 1 is an odd number. What’s more, the expression 2 n + 1 represents all odd numbers. This is the power of looking for and making use of structure — representing infinitely many things in a single short expression.”

I had given Felix a copy of Danielson’s book after we first met, so I called her to find out how she and her daughter are faring in math.

“Oh, honey, we are doing fantastic. That book was fantastic,” she said. “My daughter is doing great in math, and I can help her when she needs it. Plus, I get to feel smarter than a third-grader.”

This is where successful math education starts; with adults who know what questions to ask and who have the skills to help children discover their own solutions.

Jessica Lahey is a teacher and the author of “ The Gift of Failure: How the Best Parents Learn to Let Go So Their Children Can Succeed ” and a forthcoming book on preventing addiction in children.

Follow On Parenting on Facebook for more essays, news and updates, and join our discussion group here to talk about parenting and balancing a career. You can sign up here for our weekly newsletter.

More reading:

School’s still in. Here’s how to help them get through to the end.

9 ways parents can empower a child who has learning issues

10 ways to take the struggle out of homework

Barnard’s president on how to develop STEM-confident girls

High Impact Tutoring Built By Math Experts

Personalized standards-aligned one-on-one math tutoring for schools and districts

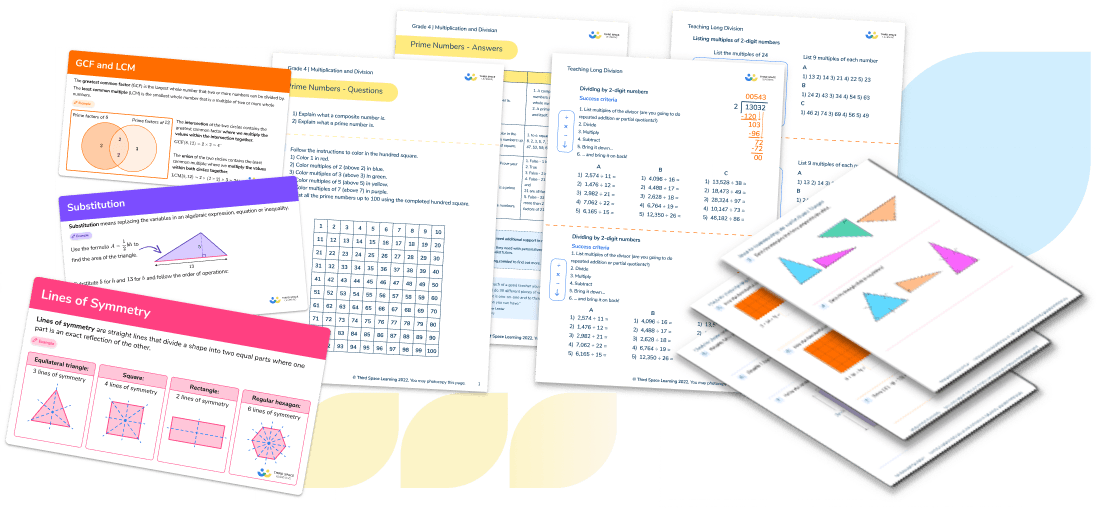

Free ready-to-use math resources

Hundreds of free math resources created by experienced math teachers to save time, build engagement and accelerate growth

Math Homework Guide For Helping Kids With Math At Home

Sophie Bartlett

While the amount and difficulty of math homework that your child will receive will vary from school to school, one thing is common to all parents: you will at some point be asked to help your child with math homework.

This blog is part of our series of blogs designed for teachers, schools and parents supporting home learning .

Depending on your age, how recently you were taught elementary school math, and your own attitude toward learning math, you may face that moment with a level head or with a rising sense of panic.

Much of today’s math may at first glance seem unfamiliar to you – math curriculums have changed quite a lot in the last 5-10 years, never mind the last 20 – and elementary school children today in every grade are expected to do more and demonstrate greater understanding than in many previous years.

If you feel like you’re more in the ‘panic’ than relaxed camp, you’re not alone. Hundreds of thousands of parents across the country feel the same way!

As experts in math tutoring, we’re on hand to support you to support your children!

The research shows that input from carers and parents is the key factor in determining good outcomes at elementary school.

However, we also understand that when you’re busy juggling the needs of your children, yourself, and completing the 1001 other daily tasks that come with being a parent, planning a math lesson is the last thing you feel like doing.

So in this article we aim to give you the key information about what elementary school math now entails, some math homework activities suitable for each grade, and lots of links to more worksheets, workbooks, and more.

The move to math mastery

- Math in your child’s elementary school

How to help with 1st grade math (6-7 year olds)

How to help with 2nd grade math (7-8 year olds), how to help with 3rd grade math (8-9 year olds), how to help with 4th grade math (9-10 year olds), how to help with 5th grade math (10-11 year olds).

- How to help with 5th grade math – state assessments (10-11 year olds)

How to help with 6th grade math (11-12 year olds)

Final thoughts on math at home.

Recently, math curriculums have placed an emphasis on mastery, fluency, and problem-solving in math.

In a nutshell, the onus is on a deep understanding of mathematical concepts, rather than learning strategies and facts off by heart, and this is something to bear in mind as you look to help your child with math throughout elementary school.

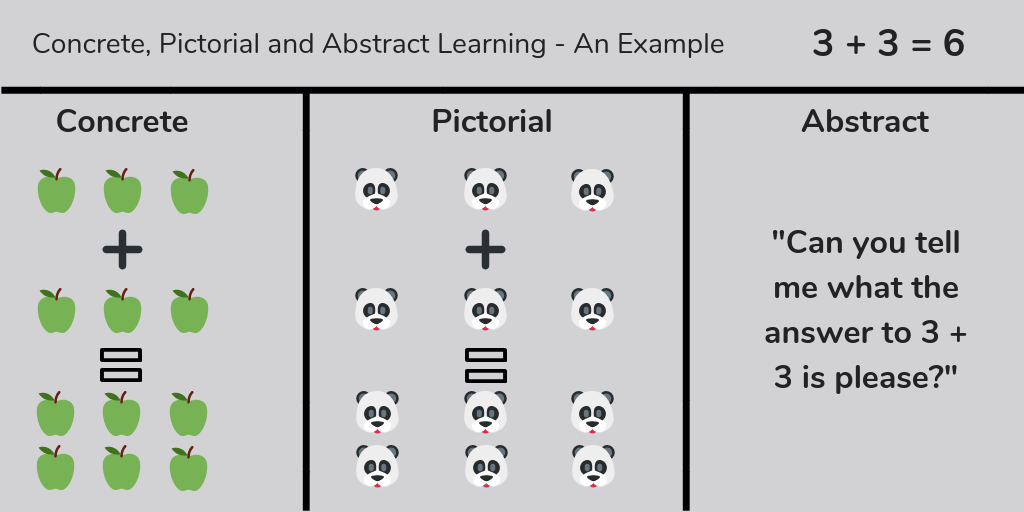

Approaches like concrete-representational-abstract , open up the inner workings of mathematical concepts and allow us to really take a look at what we’re doing with numbers.

Studies have shown that by using concrete math resources in the first phase of learning, children are more able to understand representational images (like pictograms or bar models) in the second phase of learning.

These two steps make the abstract phase of learning (when there are only numbers involved) seem like a completely natural progression.

Using these steps is a great way to help your child understand the way that math applies to the real world, and it means that they will be well-equipped to deal with all sorts of mathematical conundrums.

Math in your child’s elementary school

Once you know about the standards your state follows and where some of these more ‘modern’ math concepts come from, the key thing to know as a parent is how your own elementary school is implementing these standards.

This will help you understand exactly what it is that your child needs to know for math at each point of their elementary school life.

The main elements you should get on top of are as follows:

- The state standards or scheme of work your school is following

- Your school’s home learning or homework policy

- Key curriculum terminology that may be new to you

1. Your school’s math curriculum

Most schools now publish on their website the math topics that children will be studying each year and each term. They may refer to this as their scheme of work or their curriculum. There are lots of different ways schools teach these topics but Eureka Math is one of the most popular curricula and one you may hear about a lot!

This is an invaluable resource for you as a parent as it means you can make sure that you’re supporting them with the right homework help at the right time. If your child hasn’t completed their place value module this semester, it will make it harder for them to do multiplication x 100 or work with decimals as an example.

2. Your school’s home learning or homework policy

Before Covid-19 times, home learning in a school context was generally just used to refer to the ‘added extras’; the stuff relevant to your school’s math curriculum that you could do to support it.

While in subjects like Geography and History it might suggest museums or websites to visit, in math it was more likely to be focused on recall of number facts and multiplication facts, and occasional homework sheets.

Now of course home learning incorporates so much more to it than just ‘homework.’ However, your school will have a policy on what it expects or wants families to do for math homework in addition to ordinary lessons and it’s worth taking a look at this before worrying that your child has too much or too little math homework.

Read more: The homework debate in elementary schools

3. Important terminology in elementary math

Even if you have a great working relationship with your child’s class teacher, some of the jargon used in schools can be almost indecipherable.

Here are just some of the more esoteric and unexpected key terms that teachers may use when talking about math:

But don’t worry. We’ve created a free math dictionary for kids and parents that includes all these terms and more. Head over there whenever you encounter a word whose meaning is unclear.

Now we have run through the key things you need to know about what your child is learning in math at school, we can move onto how you can help them with their math homework!

While kindergarten might have introduced many new ideas and a very different way of learning than preschool, 1st grade is when your child will be tested on how well they’ve actually understood what they’ve learned.

Here are some quick tips you can use to help your child feel prepared for the challenges ahead of them.

Math tip 1: Check their understanding of the basics

Moving into 1st grade, there are some basic math concepts children should feel comfortable with. The key topics to check are:

- Does your child know how to count to 100?

- Can your child write numbers from 0 to 20?

- Can you child answer “how many?” questions about groups of objects?

- Can your child count up starting at any given number?

- Can your child solve basic addition and subtraction problems?

- Can your child understand the numbers 11-19 as a ten plus some ones?

- Can your child name basic 2D and 3D shapes?

If your child is struggling with any of these, they’ll probably find parts of what they learn in 1st grade that much harder. Luckily, you can find ways to help them practice these in our dedicated 1st grade math page.

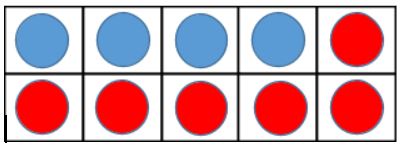

Math tip 2: Work on helping your child recognize number bonds

Number bonds are pairs of numbers that add up to certain totals e.g. 3 + 7 = 10. A good understanding of number bonds is important for nearly every part of math your child will learn and an important building block to develop number sense, so it’s crucial they feel comfortable with them.

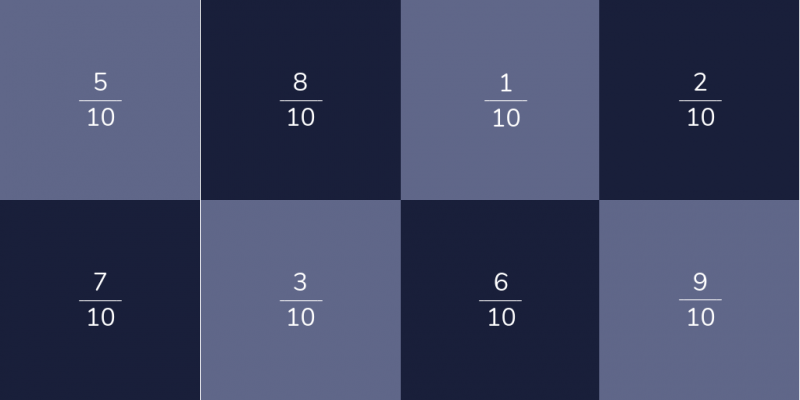

The most important number bonds are those that add up to 10. Look at the example below:

Children should understand the relationship between 4, 6 and 10 and the different ways these three numbers can interact. So they should understand that 4 + 6 = 10 is the same as 6 + 4 = 10, and that 10 – 6 = 4 or 10 – 4 = 6 are the reverse .

Once your child is happy with numbers bonds up to 10, you will want to move on to number bonds up to 20. These are slightly more complex, and need a basic knowledge of place value as well.

For example, the expression 9 + 5 can be reformulated as 10 + 4, but this is much easier to do if your child understands that 9 is close to 10 and 4 is close to 5.

- 1st Grade Math : Home Learning Toolkit for 6 and 7 Year Olds

It’s likely that your 7-year-old will encounter many concepts that are new to them during their 2nd grade math lessons, and this can be a daunting time for some young children.

New ideas, coupled with the higher expectations of accuracy in their answers can be a shock to the system for some 2nd graders, so here are a few quick tricks that will help your child get over any mathematical shaped obstacles swiftly and smoothly.

Math tip 1: Cultivate accuracy as a habit in 2nd grade

An easy way to work on cultivating accuracy is by getting your child to measure anything and everything with a ruler or a tape measure. This is a good way for you to ensure that your child is giving accurate answers to questions, without the questions themselves being too difficult.

For example, a quick measuring activity that helps promote accuracy in answers could be as simple as this:

Mom: “So Sophie, can you tell me how many centimeters long my cell phone is?”

Sophie (using a ruler/tape measure): “I think it’s about 7cm long.”

Mom: “ You’re right it is roughly 7cm long, but can you tell me exactly how long it is?”

Sophie: “It is 7.4cm long.”

Mom: “It is! Well done.”

This may be a simple example, but it shows you just how easy it can be to implement real-life math into your daily life in a useful way.

There are lots of ways you can make it fun, whether that be by measuring each other’s height, recording how much a plant grows each day or even seeing how long the pet dog’s tail is. The possibilities are endless here!

Cultivate a habit of accuracy early on, and this will be reflected across your child’s learning for the remainder of their school life (and not just in math).

Math tip 2: Work with equal groups of objects to gain foundations for multiplication

In 3rd grade, students will dive deep into multiplication, so it’s important for 2nd graders to begin setting a foundation for understanding the concept.

Second graders should already be proficient in skip counting by 2s, 5s, and 10s, so take it a step further by asking them to skip count by 3s, 4s, or any other number (up to 12). This will familiarize them with the numbers they will see in the times tables.

Another way to help set a foundation for multiplication is to ask your child to organize objects into rows and columns to make an array. You could even practice during snack time at home, using food like crackers or M&Ms to organize into an array.

Add in the mathematical element by asking them to use addition to determine the total number of objects in the array. (Add up the number in each column or add up the number in each row.) They can also be asked to write an equation to represent the total.

Math tip 3: Challenging your 2nd grade child with math at home

Up until this point, your 7-year-old will be used to using one operation (adding or subtracting) at a time.

Challenge them by mixing it up!

Ask your child to mentally add up the things you buy on a shopping trip. Every now and then, put something back to keep the subtraction practice going.

One of the most important things to do at this stage is to try and incorporate math into everyday life in fun and engaging ways, and this is just one of the ways you can do so!

Another favorite way is to incorporate some of these math games into family life at home. There are loads to choose from, indoor, outdoor or even in the car!

- 2nd Grade Math : Home Learning Toolkit for 7 and 8 Year Olds

At this age, it’s useful to introduce a couple of new concepts that, while it is important to ensure they are not too difficult, can be a little confusing at first.

At this point in elementary school your child will be dealing with large numbers and more complex operations. This might seem daunting, there’s plenty you can do to get over these hurdles at home.

Math tip 1: Use written strategies to add and subtract large numbers

If you’re shopping online, enlist your 8 year old to help you. Tell them exactly what’s on your wish list (and don’t be afraid to push the boat out). Once your child has a list of items and prices, work together using written addition to find the total.

This is your chance to really splash the (metaphorical) cash, so if you’ve had your eye on that $1,000 sofa or the $2,300 TV, now is the time to add it to your shopping list! Just make sure hands stay well away from that “buy now button”….

Math tip 2: Help them get started with division and multiplication

Your child may have learned the very basics of multiplication, but it is covered much more heavily in 3rd grade, and division is introduced for the first time.

Rather than just getting your child to memorize the multiplication facts, support their learning by helping them see multiplication and division in more simple terms.

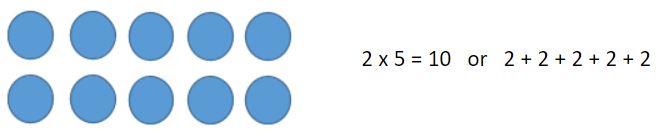

One of the simplest ways to look at multiplying is repeated addition . 5 x 2 can be seen as 2 lots of 5 (or 5 + 5). Equally, 2 x 5 can be seen as 5 lots of 2 (or 2 + 2 + 2 + 2 + 2.) Develop this understanding by showing this using objects:

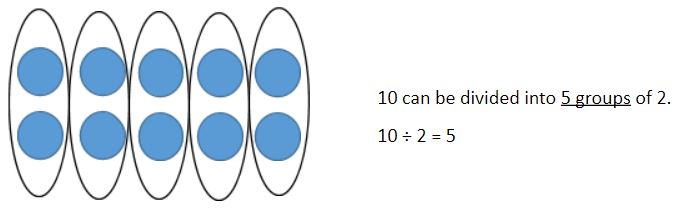

Division can be explained in terms of grouping and sharing. Grouping involves seeing an expression such as 10 ÷ 2 as, “How many groups of 2 can be made from 10?”

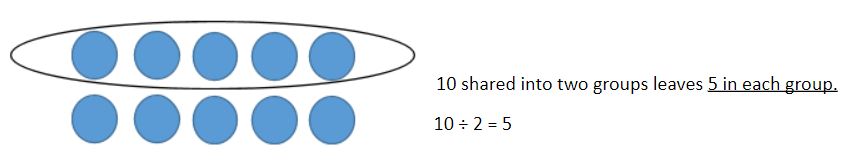

While sharing involves seeing 10 ÷ 2 as, “If I share 10 into 2 equal groups, how many are in each group?”

Math tip 3: Practice multiplication facts every day with your 3rd grader

The more you practice, the better. Sing it, shout it, whisper it, dance it. Whatever it takes!

Although it might not seem like the most entertaining math in the world, a solid knowledge of your multiplication facts removes barriers to more complex math further down the line.

Multiplication facts play a huge role in everyday life, with many of us taking them for granted. For example, if you are shopping and see that pineapples are $2.00 each and you know that you require 3 of them, you have no problem working out that this will come to a total of $6.00.

At 8 years old your child might not be able to work that out just yet, and that is why it is so important for them to cement their multiplication fact knowledge as early as possible.

Math tip 4: Challenge your 3rd grader with some fractions!

One way to really ramp up the difficulty level is by getting fractions involved. They may not be anyone’s favorite part of math, but you should not underestimate their importance both in and out of the classroom.

Ordering fractions can be a challenge for even the strongest mathematicians at this age, so try ordering tenths first before moving onto other fractions like quarters, halves and thirds.

You can make this more fun by creating a simple clothesline and pegging fraction cards to it. Adding a time limit to activities such as this can also help your child to engage with the task, so why not give them the challenge of ordering all of the tenth fractions in under a minute?

- 3rd Grade Math : Home Learning Toolkit for 8 and 9 Year Olds

This is the age when knowledge retention really begins to come to the fore, and if you spend just five minutes a day revisiting a few fundamental skills, you’ll find that your child can take on new ideas effortlessly. In particular, familiarizing your child with angles, and continuing to practice multiplication facts (up to twelve) will stand them in good stead in the future.

Math tip 1: Get the protractor out (whenever you can)

Protractors have a funny way of muddling most young mathematicians, and it certainly doesn’t help that there are two rows of numbers to contend with!

That being said, it is a crucial part of a mathematician’s pencil case, so try to have one on hand and use it wherever possible to measure angles accurately. This is a great way to make an otherwise dull trip to the home improvement store for your child exciting, as they help you to measure the all-important angles on everything from tins of paint through to planks of wood.

Bringing in active math such as this can be a great way to cement learning, and you should find that your child is much more engaged with the topic as a result too!

Math tip 2: Get your 9-year-old to read the time, all the time!

Telling and writing time is a skill mastered in 3rd grade, but it is one that can be quickly forgotten without practice. Time may go quickly for us adults, but for kids who have grown up predominantly reading the time on phone screens and tablets, analog clocks look like something from another planet.

You can avoid the confusion by hanging analog clocks in your home from an early age and modeling reading the time out loud at every opportunity. Practice makes perfect when it comes to telling time, so be patient and keep at it.

Try to remember to ask your child what the time is every time you take a glance up at the clock, as not only will this be a good chance to help them learn how to tell the time, but it might just remind you to get the dinner out of the oven too!

Math tip 3: Challenge your 4th grader with math at home

Weather permitting, take a walk down to your local bus stop or if the rain is proving too potent, browse train timetables online. (Bonus points if it’s a timetable that really applies to your commute or a regular journey!)

Challenge your 9-year-old to work out the difference in time between stops on the route.

Can they find the shortest stop?

The longest one?

How long does the whole route take?

Not only is reading timetables interesting, but it’s also a skill that could be useful in later life. They will have no excuses for missing the bus to high school if they have been taught how to read timetables properly!

If riding a bus is not common for you or your child, you can also look at an online map and calculate how long the commute takes in your car to various places around your town.

- 4th Grade Math : Home Learning Toolkit for 9 and 10 Year Olds

At this age, it’s worth having conversations around what your child finds difficult and easy in math.

Everyone struggles with math at some point, but if you can ask for help, you’re much more likely to succeed. With the introduction of several completely new topics, now is the time to work through any misunderstandings and avoid them building up into a bigger issue.

Math tip 1: De-mystify the relationship between fractions and decimals

The relationship between fractions and decimals is one that puzzles many 10-year-olds (and in fact, a lot of adults too!).

When children first encounter fractions at school, there’s no mention of decimals, so it’s no surprise that it comes as a bit of a shock later on. The important thing to remember is that fractions and decimals are just two different ways of showing part of a whole.

One tried and tested technique that is used by teachers and parents across the land is to bring many children’s favorite food, the trusty pizza, into the mix here. If you are splitting the pizza into four, why not ask the question of how much each person is getting as a fraction and a decimal?

By being able to visualize the mathematics taking place in front of them, children are better equipped to work out the answer, and of course, they get some pizza too! This is a fantastic way to help your child with math at home.

Math tip 2: Challenge your 5th grader with math at home

At this age, the curriculum offers plenty of challenges for 10-year-olds.

Being able to recall equivalent fractions and decimals will stand your child in good stead, and if you are looking to challenge your child then these are the topics you should do it with.

Quick quizzes on converting decimals into their equivalent fractions are a good way to encourage learning on these topics, and you can easily incorporate them into everyday life. Examples could include:

- I’ve filled this glass of water up ½ to the top. How much room is left in it as a decimal?

- We’ve walked 0.25 of the way to school. How far is that as a fraction?

- ⅕ of your dinner is made up of vegetables, how much is this in decimal form?

There will be a lot of other examples that come up in your everyday life, but these ones are just there to inspire you!

If you’re searching for something to accompany the real life math, take a look at our blog which tackles how you can tackle 5th grade math in greater detail.

How to help with 5th grade math – state assessments (10-11 year olds)

Fifth grade is typically a grade level where students will have state assessments across multiple content areas at the end of the year. With these assessments looming, it can feel like a mad dash to the finish line, but you have to remember one simple thing…

Don’t panic!

Just remember that there’s plenty that you can do in a short amount of time to boost your child’s confidence in math.

Begin by taking a look at practice test papers together as this is one of the best ways for both of you to find out which math problems your child finds easy and which ones need a bit of work. It also helps to break word problems down step-by-step to scaffold your child’s understanding of math questions.

Bear in mind that it is normal for children to react differently to test papers than to the work they see day-to-day, so try to build a positive experience around tests to relieve the pressure (the promise of a trip to the park after completing a sample test is a good way of doing this).

Math tip 1: Practice taking tests the fun way

The best way to get your child on board with practice test papers is to take them together.

Don’t worry about getting the answers wrong – by showing your child that mistakes are the first step in plugging knowledge gaps and growing, you’re teaching them to be more resilient in the face of a challenge.

The best part?

You can ask them to teach you how to correct your mistakes, which will help to consolidate their own learning in the process.

If you don’t have the time to sit and take the whole test, you can do one question a day together for a strong, steady build-up of skills. Slow and steady definitely wins the race.

Math tip 2: Never neglect the basics!

A common mistake is to focus on the plethora of new concepts, leaving basic skills like mental arithmetic to stagnate.

Strong foundations in basic math make the harder stuff more accessible; if you’re getting nowhere with the tough questions, go back to the basics.

A good grasp of place value, multiplication facts and mental arithmetic will help when you revisit those difficult questions later on.

Math tip 3: Challenging your 5th grader with math at home

Once your 11-year-old has the basics down and feels confident with exam technique, you can stretch their learning by introducing pre-algebra.

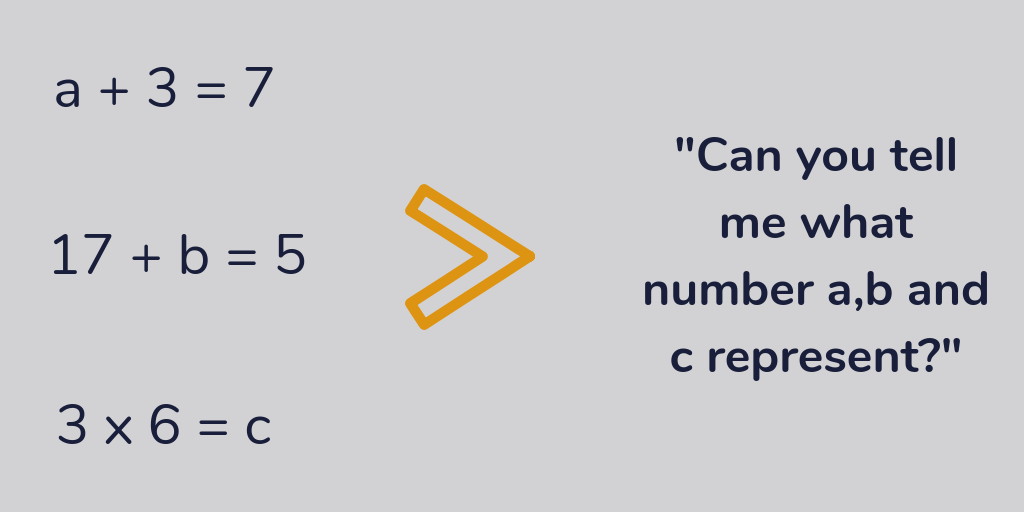

Confident mathematicians will enjoy the novelty and challenge of working out what the letters mean in simple equations. Keep things simple to begin with and work your way up to more difficult equations in the future. Examples of some equations you could start with include:

Equations are never high on most children’s to-do lists, but they do become increasingly important as school life goes on, so beginning to secure this knowledge at an early age is only ever beneficial.

5th Grade Math : Home Learning Toolkit for 10 and 11 Year Olds

With a new school, new friends, and new subjects all to deal with, kids can feel overwhelmed with the start of 6th grade before they even start! While it might be tempting to try and help with subjects like math by finding ways to ‘get ahead’, the best support you can offer is to make math seem less scary to your child.

Math tip 1: Make math a ‘normal’ part of life

As adults, we use math in our day-to-day lives without really thinking about it. Sometimes it doesn’t even seem like math to us, because we’ve become so used to it.

Your child won’t have that kind of context yet – to them math is still just a bunch of facts that aren’t related to real life.

Luckily, the fact that we use math all the time makes it very easy to give your child that context: get them involved in activities like shopping, cooking, working out holiday budgets; anywhere you realize you use math, get your child involved!

Math tip 2: Take time to ‘review’ the day with your child

Some of you might already automatically ask your child how their day was when they get home – and your child might reply with a one word answer, if they reply at all!

But if you take this just a little bit further, you can actually help your child strengthen the memories of what they learned that day. Your child might start by talking about things that happened with friends, or ‘funny’ bits of lessons (which we call ‘episodic’ memories).

At this point, asking something like “What were you supposed to be learning about when X happened?” will help your child remember that topic – and as they talk about it, they’ll be making that memory stronger in their minds.

It’s important not to ignore the ‘off-topic’ stuff, or try and get around it – these stories are important to your child, and listening to them shows you’re really interested in what happened to them at school.

Math tip 3: Help your child develop a Growth Mindset

A Growth Mindset is a way of looking at work. Instead of saying “I can’t do this” when they run into an especially hard problem, someone with a growth mindset will say “I can’t do this yet, but I can learn to.” It’s developing your child into young learners!

Your child may already be learning about Growth Mindset in school – it is very popular with teachers – but how you speak at home will also have an impact.

Many of us struggle with the kind of math your child will be starting to learn in 6th grade, and it’s a very natural reaction to say “I wasn’t very good at math when I was your age.”

You might mean that your child is much better at it than you are, but that’s not what they hear; you’ve managed to make it to adulthood apparently being “not very good” at math – if that’s the case, why should they bother trying?

You can encourage your child to develop a growth mindset by using phrases like “You’re working very hard on that”, “I’m sure I learned this but I’ve forgotten, can we both look at it?” and “I’m sure you can get this if you keep going” instead.

To summarize, if you find yourself wondering ‘how can I help my child with math homework?’, the simple answer is to work in stages depending on the level your child is at.

1. Early stages of math

If they are in the early stages of their mathematical journey in any single concept then you should help them by using concrete manipulatives to help them visualize the problem.

- Is your child struggling to work out what half of 12 is? 12 pieces of pasta on the kitchen table could help solve this.

- Do centimeters and inches prove problematic? Using a ruler to measure their favorite toys can help here.

The use of concrete resources is only limited by your imagination and there are hundreds of examples to be found all around the house which can help your child get better at math.

2. Good foundations

Once your child has a firm grasp on the basics, it is time to move onto representational problems to help them continue to progress.

You certainly don’t have to be an artist to use pictures as representations to help your child with math. By creating simple scenarios on paper rather than with physical objects, it begins to remove reliance on having something in front of them to help them solve the problem.

This ensures that they are using their brain as they have nothing else to help them!

3. Developing broader understanding

The final stage is to move past both the concrete and representational stage and onto the abstract stage which consists of numbers and more formal written strategies.

These are the types of questions your child will come up against in their tests, so by introducing them to them at home, you will help to ensure that they are already one step ahead of the game.

Just as when a teacher is teaching a whole class, different techniques work for different children struggling with math, so it is crucial that you take the time to find the thing that will give your child that aha moment!

Looking for more detail? Try these articles

- The best free websites and apps for math homework help

- Division for kids: How to help at home

- Fractions for kids: How to teach it at home

Do you have students who need extra support in math? Give your students more opportunities to consolidate learning and practice skills through personalized math tutoring with their own dedicated online math tutor. Each student receives differentiated instruction designed to close their individual learning gaps, and scaffolded learning ensures every student learns at the right pace. Lessons are aligned with your state’s standards and assessments, plus you’ll receive regular reports every step of the way. Personalized one-on-one math tutoring programs are available for: – 2nd grade tutoring – 3rd grade tutoring – 4th grade tutoring – 5th grade tutoring – 6th grade tutoring – 7th grade tutoring – 8th grade tutoring Why not learn more about how it works ?

The content in this article was originally written by primary school teacher Sophie Bartlett and has since been revised and adapted for US schools by elementary math teacher Katie Keeton.

Related articles

Home Learning Ideas, Activities and Guides For Primary and Secondary School Teachers

Free Home Learning Packs For Primary Maths KS1 & KS2

Back To School Tips For Parents: 10 Ways To Help Your Child Get Ready And Excited For Primary School!

How To Prevent The Summer Slide: 10 Ways Parents Can Ensure Their Child Is Prepared For The New School Year

PEMDAS Math Poster (Spanish Version) [FREE]

Trying to help remember what the mnemonic PEMDAS stands for? Display this poster to engage young learners with answering questions on the order of operations.

Check out more English and Spanish posters available in our US resource library!

Privacy Overview

3 Ways to Strengthen Math Instruction

- Share article

Students’ math scores have plummeted, national assessments show , and educators are working hard to turn math outcomes around.

But it’s a challenge, made harder by factors like math anxiety , students’ feelings of deep ambivalence about how math is taught, and learning gaps that were exacerbated by the pandemic’s disruption of schools.

This week, three educators offered solutions on how districts can turn around poor math scores in a conversation moderated by Peter DeWitt, an opinion blogger for Education Week.

Here are three takeaways from the discussion. For more, watch the recording on demand .

1. Intervention is key

Research shows that early math skills are a key predictor of later academic success.

“Children who know more do better, and math is cumulative—so if you don’t grasp some of the earlier concepts, math gets increasingly harder,” said Nancy Jordan, a professor of education at the University of Delaware.

For example, many students struggle with the concept of fractions, she said. Her research has found that by 6th grade, some students still don’t really understand what a fraction is, which makes it harder for them to master more advanced concepts, like adding or subtracting fractions with unlike denominators.

At that point, though, teachers don’t always have the time in class to re-teach those basic or fundamental concepts, she said, which is why targeted intervention is so important.

Still, Jordan’s research revealed that in some middle schools, intervention time is not a priority: “If there’s an assembly, or if there is a special event or whatever, it takes place during intervention time,” she said. “Or ... the children might sit on computers, and they’re not getting any really explicit instruction.”

2. ‘Gamify’ math class

Students today need new modes of instruction that meet them where they are, said Gerilyn Williams, a math teacher at Pinelands Regional Junior High School in Little Egg Harbor Township, N.J.

“Most of them learn through things like TikTok or YouTube videos,” she said. “They like to play games, they like to interact. So how can I bring those same attributes into my lesson?”

Part of her solution is gamifying instruction. Williams avoids worksheets. Instead, she provides opportunities for students to practice skills that incorporate elements of game design.

That includes digital tools, which provide students with the instant feedback they crave, she said.

But not all the games are digital. Williams’ students sometimes play “trashketball,” a game in which they work in teams to answer math questions. If they get the question right, they can crumble the piece of paper and throw it into a trash can from across the room.

“The kids love this,” she said.

Williams also incorporates game-based vocabulary into her instruction, drawing on terms from video games.

For example, “instead of calling them quizzes and tests, I call them boss battles,” she said. “It’s less frightening. It reduces that math anxiety, and it makes them more engaging.

“We normalize things like failure, because when they play video games, think about what they’re doing,” Williams continued. “They fail—they try again and again and again and again until they achieve success.”

3. Strengthen teacher expertise

To turn around math outcomes, districts need to invest in teacher professional development and curriculum support, said Chaunté Garrett, the CEO of ELLE Education, which partners with schools and districts to support student learning.

“You’re not going to be able to replace the value of a well-supported and well-equipped mathematics teacher,” she said. “We also want to make sure that that teacher has a math curriculum that’s grounded in the standards and conceptually based.”

Students will develop more critical thinking skills and better understand math concepts if teachers are able to relate instruction to real life, Garrett said—so that “kids have relationships that they can pull on, and math has some type of meaning and context to them outside of just numbers and procedures.”

It’s important for math curriculum to be both culturally responsive and relevant, she added. And teachers might need training on how to offer opportunities for students to analyze and solve real-world problems.

“So often, [in math problems], we want to go back to soccer and basketball and all of those things that we lived through, and it’s not that [current students] don’t enjoy those, but our students live social media—they literally live it,” Garrett said. “Those are the things that have to live out in classrooms right now, and if we’re not doing those things, we are doing a disservice.”

Sign Up for EdWeek Update

Edweek top school jobs.

Sign Up & Sign In

Here's Why Math is Making Your Child Cry and What You Can Do About It

Written by Kira Gavalakis

It’s understandable that we, as parents, don’t want to grade our kids harshly or give them criticism. We want them to be happy, and feel good about themselves, especially as a student. As a result, we may avoid chatting with our kids about their grades, or even simply brush it off as a bad teacher. But what’s actually happening is that we’re making math more difficult for our kids through our manifestation of denial.

To our kids, our denial might look like anger, frustration, or sadness, making those math tears come even quicker.

I’ll put it simply: math is making your child cry because we as parents are making it difficult.

I know, it’s probably a little hard to hear at first. But in this article, I’ll give you some steps on how you can alleviate those math tears and set your kid up for math success.

Passing vs. Getting the Right Answer

We all want our kids to do well. But in math, there’s a difference between doing well and actually understanding the concepts.

There are two real ways to look at how your child is learning math.

- Did they get the answer correct?

- Can they explain how they got that answer and how to apply it in real-world examples?

Typically, even if a child is getting #1, the tears are coming because #2 isn’t helping them get to the problem on their own. Since mathematics is very abstract, it can be tough to pin down the concepts that guide math exercises and problems.

For instance, even if your child has memorized their multiplication tables, they may not really understand why 4x3 is 12. They’ve just memorized a series of numbers, so when they move onto the next lesson, they’re missing a fundamental understanding of why two numbers multiplied together equal their product. This can snowball, creating much bigger issues later on, sometimes even years into the future.

So now, it’s back to us as parents. If we aren’t able to allow our children to make mistakes, get things wrong, and ask questions, they’ll never stop to ask for help. They’ll motor on through math classes, missing basic concepts, and struggling unnecessarily as a result. They’ll be so focused on impressing us, that the root of the mathematical problems will fly out the window, and you’ll both be wondering why math is so frustrating.

Looking at Math Differently As a Parent

When we’re not allowing our kids to fail because of our own fears, we’re sacrificing their learning process. It’s actually one of the reasons I created Elephant Learning; to provide kids with abstract problems put into real life terms and situations, and to give them the opportunity to be wrong.

What our platform does is give kids the opportunity to fail . Since a gamification platform doesn’t hold emotions, it won’t feel upset, angry, or guilty if a student gets a problem wrong. Instead, it’s trained to continue pushing concepts that kids are getting wrong more and more into their game, so they can keep practicing until they’re mastered.

Related: Emotion is Holding You Back as a Homeschooling Parent

When we as parents are too emotionally involved in our kid’s learning experience, we project our desire for them to be right so badly that we sacrifice their own ability to understand the process behind the math they’re doing.

So… how do we change this thought process?

First, we need to recognize that our fear of “wrong” is what’s making our children frustrated with math. We’re showing that getting an answer wrong and learning from it is worse than getting an answer right and not understanding it.

Next, we need to follow Thomas Edison’s words: “I have not failed. I’ve just found 10,000 ways that won’t work.” This means looking at your children’s failures as practice rounds and learning opportunities, instead of letting it trigger your natural fear of your kid not understanding something. If you’re looking for your child to have big successes as Thomas Edison did, you have to allow those 10,000 mistakes, failures, and wrong answers without any hesitation.

Kids especially have to be able to play with ideas in their heads, go through trial and error scenarios, and uncover different solutions without the fear of disappointing you. If we as parents are getting in the way of that, we’ll continue making learning math harder than it needs to be.

How to Look at Math Differently

A lot of parents want their kids to be able to ace a quiz or test, and may not bother checking that they fully understand the concepts at play. And ultimately, what we’re impressing on our children is our own fear of being wrong, which in turn, will teach our kids to fear being wrong. We’re training them to fear “wrong” -ness more than a lack of understanding, to their long-term detriment.

How to Start Practicing This in Real Life

- The first thing you have to do is accept the reality of how your child is performing in math class, and say it out loud. “My child isn’t understanding the deeper meaning behind the math they’re learning in school.”

- Next, find a learning tool or an expert in this field like Elephant Learning that can help teach your child a deeper understanding of the concepts, instead of just getting the questions right.

If you decide to join us here at Elephant Learning, we start students older than 5 in a placement exam, which was designed to start behind your student and catch up to them. For example, if you chose the third-grade exam, we’re actually testing them on second-grade concepts like addition and subtraction to see if they’re even ready for third-grade material they’re being given in school.

This way, you’ll get a good idea of what your child understands and what they don’t understand. Then, we’ll start building the language. Because even if they don’t understand the procedures and processes, they’ll understand the underlying concepts.

It’s important to view Elephant Learning as a tool, regardless of the other academic programs they’re utilizing (tutors, after-school programs, etc).

The involvement on the parent’s part is minimal. And sometimes, that’s just what our kids need to turn tears into 10,000 successes.

Related Posts

Benjamin Franklin: From Self-Taught School Dropout to Founding Father

Learn how Franklin became an accomplished inventor, a renowned writer, and a Founding Father despite his lack of formal education!

Jim Carrey: From Childhood Homelessness to Famous Actor

Learn how Jim Carrey overcame his difficult childhood to become a famous comedic actor!

Albert Einstein: Overcame Early School Challenges, Won Nobel Prize

Discover how Einstein overcame his childhood challenges with a traditional school curriculum to change the world of physics!

Guaranteed Results

Your child will learn at least 1 year of mathematics over the course of the next 3 months using our system just 10 minutes/day, 3 days per week or we will provide you a full refund.

Empower Your Children With Mathematics

Our only mission is to empower children with mathematics. Got a question? We LOVE mathematics and are happy to help!

We are available online 24/7

© 2022 Elephant Learning, LLC 1-888-736-5876

Tips for doing Math Homework with Kids!

Published by Salsabilatuzzahra Jaha S.Psi. from BehaviorPALS Center

Homework is one of the things that are usually done when children start school. Homework serves as one of the teaching media so that children can understand the material and continue to practice. For example, math homework. As parents, we can help our children's math homework to the maximum and make our children more enthusiastic about learning mathematics. The following are tips for parents in guiding their children who are just starting school in doing homework.

- Prepare the Homework Kit

Set up storage space like a drawer in the kitchen for a set of math homework tools. Plan the contents with your child: pencil, eraser, ruler, tape measure, scissors, construction paper, graph paper, counter (beads or nuts), calculator, and glue. The drawer can be expanded with your child by adding special tools (compass and protractor, for example) according to the child's curriculum material.

- Have a Routine Schedule for Math

Encourage positive attitudes and study habits by scheduling math homework time at the same time and location each day. We can use the room, family room, kitchen table or several rooms in the house.

- Ready to help

This is the most important thing in helping children with homework. Make yourself available during Homework time. Together with your child, you can create a relationship that encourages natural conversation and interaction.

- Be relaxed and positive

Remember that you are not expected to act as a mathematician. So, stay relaxed and don't be too pushy. However, you should also be positive that even if you are not a mathematician, you can help your child learn. Giving your child one-on-one attention will have a positive effect if you focus on establishing natural conversation and two-way communication.

When Doing Homework. Keep the atmosphere as calm as possible and minimize distractions in order to maintain focus.

- Try to be more interested in children's activities!

Show your child that you are interested in their activities while doing their math homework. Ask your child to explain what they do and why.

- Learn from mistakes

If your child gets an answer wrong, ask them to prove that the answer is correct. Remember that:

Calm down. Mistakes are an opportunity to learn and can help children to keep trying! Willing to try again is an important quality that all children should have.

But if your child becomes more frustrated and less satisfied, stop. Ask them to tell you about things they can do successfully. Remind them that they can and do. They have learned many things that require patience and practice in the past and some of them take longer than others. Such as riding a bicycle, writing paragraphs, speaking a second language, playing a musical instrument, or perfecting a dance routine

. Help your child to see that it is important to solve these math problems, even if they are difficult. Give your child the time they need to work on the questions. Encourage them to do their best.

- Team approach

Your child's teacher and other members of the teaching team are your partners in education. So, parents, and teachers are on the same team in education! You can use your child's journal to communicate with the teacher. You can also ask for strategies to use at home related to your child's topic and learning style.

- Studying together!

Remember that we are just parents. It's okay if you don't know the answer. However, if your child asks for your help and you don't know the answer, be honest and say, "I don't know, but let's work it out together." Keep helping children by doing it together.

If the problem is too difficult for you, admit it, then model it and emphasize to your child the determination to keep trying to solve it.

If you continue to be unsuccessful, don't hesitate to ask your child's teacher or other members of the teaching team for help. This will give your child permission to do the same when they are stuck.

Those were some tips for parents when helping children in doing math homework. We can use this opportunity to get closer to children and also reduce children's anxiety in learning mathematics. May be useful!

By Salsabilatuzzahra Jaha S.Psi from BehaviorPALS Center

CODE (2015). Inspiring Your Child to Love Math. Ontario: Council of Ontario Directors of Education. https://www.parentengagementmatters.ca/downloads/inspiring-your-child-to-learn-and-love-math/doc/en/module01_resource_guide_2015-09-21.pdf

Homework, Math, kids

Children 4 Years - 6 Years / 4 Tahun - 6 Tahun / Counting / Berhitung / Education / Pendidikan / Tips for doing Math Homework with Kids!

Top 10 Ways to Help Your Kids Do Well in Math

By: peggy gisler, ed.s. and marge eberts, ed.s..

Make Sure Your Children Understand Mathematical Concepts

Help Them Master the Basic Facts

Teach Them to Write Numbers Neatly

Provide Help Immediately When Your Children It

Show Them How to Handle Their Math Homework

Encourage Them to Do More Than the Assigned Problems

Explain How to Solve Word Problems

Help Your Children Learn the Vocabulary of Mathematics

Teach Them How to Do Math "In Their Head"

Make Math Part of Your Children's Daily Life

Fe most popular slideshow.

An Age-by-Age Guide to Teaching Kids About "The Birds & The Bees"

12 Simple Developmental Activities to Play with Your Baby

Top 10 Graduation Gifts

8 printable thank-you cards for teacher appreciation week, subscribe to family education.

Your partner in parenting from baby name inspiration to college planning.

- AI Generator

4,426 Child Doing Math Homework Stock Photos & High-Res Pictures

Browse 4,426 child doing math homework photos and images available, or start a new search to explore more photos and images..

The Hechinger Report

Covering Innovation & Inequality in Education

Confused by your kid’s math homework? Here’s how it all adds up

Share this:

- Click to share on LinkedIn (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Pinterest (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)

- Click to email a link to a friend (Opens in new window)

The Hechinger Report is a national nonprofit newsroom that reports on one topic: education. Sign up for our weekly newsletters to get stories like this delivered directly to your inbox. Consider supporting our stories and becoming a member today.

Get important education news and analysis delivered straight to your inbox

- Weekly Update

- Future of Learning

- Higher Education

- Early Childhood

- Proof Points

Allonda Hawkins said the way her children are expected to do math is “100 percent different” from the way she learned.

“There are terms that I’ve never heard before, like arrays. It’s very foreign to me and it’s hard to teach,” said the 38-year-old real estate agent from Winston-Salem, North Carolina.

The mother of four children, ages 5 to 11, often turns to YouTube for explanations and recruits her fifth grader, Zoe, to help her younger siblings. Hawkins said she’s catching on more now that she can eavesdrop on her kids’ online classes, but still is frustrated that she doesn’t have more guidance.

“There are a lot of teachers that lack grace with parents who don’t understand,” Hawkins said of the new approach to math. “We end up teaching [our kids] the old ways, which don’t fully benefit them — especially with assignments where they have to show their work.”

With virtual learning, parents across the country are getting an up-close look at math instruction — and, like Hawkins, they don’t always know what to make of it. But with more than half of American kids still learning at home as of Feb. 21 (either all virtually or in hybrid programs), it’s time for parents to get up to speed.

Experts say it’s important for parents to know the basic ideas behind the current methods if they are going to help their kids. Positive parental help could make the difference between students being excited about math or falling behind during the pandemic, said Jennifer Bay-Williams, co-author of “Elementary and Middle School Mathematics: Teaching Developmentally” and professor of education at the University of Louisville.

The new approach is actually not all that new. It’s grounded in research going back more than 30 years and is reflected in the Common Core State Standards, which are used in 41 states. (And most states now follow standards with the same principles, whether or not they call them Common Core.) Instead of memorizing procedures to solve problems, kids are now asked to think through various ways to arrive at an answer and then explain their strategies. While some parents believe these methods are just a more complicated way of teaching math, they are designed to promote a deeper understanding of the subject and help students make lasting connections.

“There’s not just one way to solve a problem,” said Megan Burton, president of the Association of Mathematics Teacher Educators and associate professor of elementary education at Auburn University in Alabama. To fully grasp deeper mathematical concepts, “students need to think about what makes sense and build on what they learn.”

“There are a lot of teachers that lack grace with parents who don’t understand.” Allonda Hawkins, parent

Educators and mathematicians pushed for states to adopt Common Core math in hopes of moving away from a curriculum that was “a mile wide and an inch deep” and focusing more on big ideas, said Bay-Williams. When the Obama administration offered benefits to states that adopted the Core, the standards took on a partisan edge. But they were not meant to be political, Bay-Williams said. They were meant as simply a short list of concepts that would prompt teachers to spend more time on core mathematical ideas and would be common across states. In addition to a brief outline of what kids should learn in each grade, they include eight standards for mathematical practice that frame how to do math.

Related: PROOF POINTS — Evidence increases for writing during math class

The first practice standard, to make sense of problems and persevere in solving them, is the top priority, said Bay-Williams. A focus on understanding problems and working to solve them should shift the pressure away from just getting homework done correctly and encourage parents to ask how their children are thinking.

“It creates in kids this identity that they can do math” when they are asked to explain their thought processes, Bay-Williams said. “Just memorizing something their parents show them and then practice, practice, practice, leads to a different emotional reaction and a different way they think about themselves as a math doer.”

Research is clear that allowing kids to experience a “productive struggle” pays off in children’s math ability. “Productive struggle” is merely wrestling with an idea or pondering a new concept, which is when teachers say learning occurs.

127 = 12 tens and 7 ones

“Kids need to know math may be a little challenging, but it’s going to make sense” eventually, said Burton. When watching a kid struggle to complete a math problem, “it’s very tempting for a parent to want to get in there and rescue the child, which doesn’t always help in the long run,” she said.

One of the key concepts in Common Core math is that students are asked to look at numbers and think about the amounts they represent. For instance, 100 can be thought of as 100 ones, or a bundle of 10 units of 10, or “10 tens.” And 127 can be thought of as a bundle of 12 units of 10 and seven ones, or “12 tens and 7 ones,” or even “10 tens and 27 ones.”

Students are asked to use the idea that numbers can be represented differently when problem solving, too.

Take 4 x 27.

Traditionally, a student would line up the numbers vertically, multiply 4 x 7, carry the 2, then multiply … well, most adults remember the procedure. (The answer is 108.)

Now, kids are encouraged to think: Wait a minute, that’s really just 4 x 25, which is 100, plus 4 x 2, which is 8. If I add the two products together, I get 108.

4 x 27 = (4 x 25) + (4 x 2)

“That works pretty slick and makes more sense,” said DeAnn Huinker, professor of mathematics education at University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee and director of the university’s Center for Mathematics and Science Education Research. “I can do that in my head, write down a couple of partial products and add it up.”

Huinker advocates redefining math success: “It’s not being able to tell me the answer to three times five within a heartbeat. Rather, being successful means: ‘I understand what three times five is.’ ” (For those following along at home, it’s three groups of five.)

Math practices today emphasize reasoning, being able to make a viable argument and critiquing others. Teachers have students pause and think before diving in to learn a standard algorithm, said Bay-Williams. In a classroom, students might pair off and share their math strategies with a partner. With remote learning, teachers may ask students to turn to an online interactive whiteboard or record a short video.

For some students, it might help to use a number line to see the relationship between numbers. If a student is given the problem 12 minus 7, the student can start at 7, jump to 10 (that’s 3), and then jump to 12 (that’s 2), so the difference is 3 plus 2, or 5. Ten in this example is known as a “benchmark number,” said Huinker, and students are encouraged to use benchmarks to move toward more efficient and meaningful computation strategies.

3 x 5 = three groups of five