Synonyms of scholarly

- as in literate

- as in educational

- More from M-W

- To save this word, you'll need to log in. Log In

Thesaurus Definition of scholarly

Synonyms & Similar Words

- knowledgeable

- well - read

- intellectual

- professorial

- well - bred

- enlightened

- self - educated

- overeducated

- self - taught

- homeschooled

- self - instructed

- polyhistoric

Antonyms & Near Antonyms

- unscholarly

- uncivilized

- uncultivated

- semiliterate

- unintellectual

- unknowledgeable

- uninstructed

- undereducated

- educational

- pedagogical

- postgraduate

- instructive

- nonacademic

- noneducational

- extracurricular

- cocurricular

- noncollegiate

Thesaurus Entries Near scholarly

Cite this entry.

“Scholarly.” Merriam-Webster.com Thesaurus , Merriam-Webster, https://www.merriam-webster.com/thesaurus/scholarly. Accessed 7 Apr. 2024.

More from Merriam-Webster on scholarly

Nglish: Translation of scholarly for Spanish Speakers

Britannica English: Translation of scholarly for Arabic Speakers

Subscribe to America's largest dictionary and get thousands more definitions and advanced search—ad free!

Can you solve 4 words at once?

Word of the day.

See Definitions and Examples »

Get Word of the Day daily email!

Popular in Grammar & Usage

The tangled history of 'it's' and 'its', more commonly misspelled words, why does english have so many silent letters, your vs. you're: how to use them correctly, every letter is silent, sometimes: a-z list of examples, popular in wordplay, the words of the week - apr. 5, 12 bird names that sound like compliments, 10 scrabble words without any vowels, 12 more bird names that sound like insults (and sometimes are), 8 uncommon words related to love, games & quizzes.

- Features for Creative Writers

- Features for Work

- Features for Higher Education

- Features for Teachers

- Features for Non-Native Speakers

- Learn Blog Grammar Guide Community Events FAQ

- Grammar Guide

Words to Use in an Essay: 300 Essay Words

Hannah Yang

Table of Contents

Words to use in the essay introduction, words to use in the body of the essay, words to use in your essay conclusion, how to improve your essay writing vocabulary.

It’s not easy to write an academic essay .

Many students struggle to word their arguments in a logical and concise way.

To make matters worse, academic essays need to adhere to a certain level of formality, so we can’t always use the same word choices in essay writing that we would use in daily life.

If you’re struggling to choose the right words for your essay, don’t worry—you’ve come to the right place!

In this article, we’ve compiled a list of over 300 words and phrases to use in the introduction, body, and conclusion of your essay.

The introduction is one of the hardest parts of an essay to write.

You have only one chance to make a first impression, and you want to hook your reader. If the introduction isn’t effective, the reader might not even bother to read the rest of the essay.

That’s why it’s important to be thoughtful and deliberate with the words you choose at the beginning of your essay.

Many students use a quote in the introductory paragraph to establish credibility and set the tone for the rest of the essay.

When you’re referencing another author or speaker, try using some of these phrases:

To use the words of X

According to X

As X states

Example: To use the words of Hillary Clinton, “You cannot have maternal health without reproductive health.”

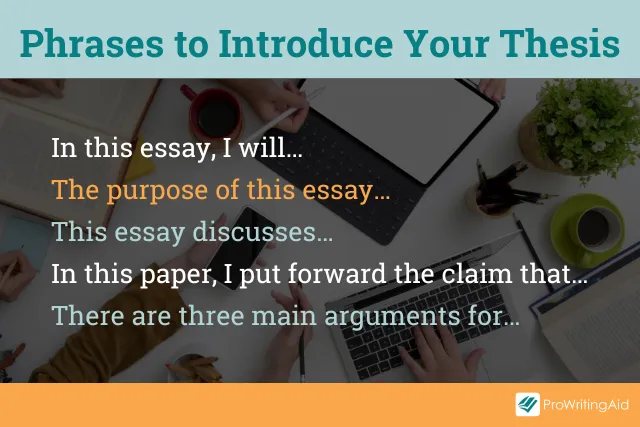

Near the end of the introduction, you should state the thesis to explain the central point of your paper.

If you’re not sure how to introduce your thesis, try using some of these phrases:

In this essay, I will…

The purpose of this essay…

This essay discusses…

In this paper, I put forward the claim that…

There are three main arguments for…

Example: In this essay, I will explain why dress codes in public schools are detrimental to students.

After you’ve stated your thesis, it’s time to start presenting the arguments you’ll use to back up that central idea.

When you’re introducing the first of a series of arguments, you can use the following words:

First and foremost

First of all

To begin with

Example: First , consider the effects that this new social security policy would have on low-income taxpayers.

All these words and phrases will help you create a more successful introduction and convince your audience to read on.

The body of your essay is where you’ll explain your core arguments and present your evidence.

It’s important to choose words and phrases for the body of your essay that will help the reader understand your position and convince them you’ve done your research.

Let’s look at some different types of words and phrases that you can use in the body of your essay, as well as some examples of what these words look like in a sentence.

Transition Words and Phrases

Transitioning from one argument to another is crucial for a good essay.

It’s important to guide your reader from one idea to the next so they don’t get lost or feel like you’re jumping around at random.

Transition phrases and linking words show your reader you’re about to move from one argument to the next, smoothing out their reading experience. They also make your writing look more professional.

The simplest transition involves moving from one idea to a separate one that supports the same overall argument. Try using these phrases when you want to introduce a second correlating idea:

Additionally

In addition

Furthermore

Another key thing to remember

In the same way

Correspondingly

Example: Additionally , public parks increase property value because home buyers prefer houses that are located close to green, open spaces.

Another type of transition involves restating. It’s often useful to restate complex ideas in simpler terms to help the reader digest them. When you’re restating an idea, you can use the following words:

In other words

To put it another way

That is to say

To put it more simply

Example: “The research showed that 53% of students surveyed expressed a mild or strong preference for more on-campus housing. In other words , over half the students wanted more dormitory options.”

Often, you’ll need to provide examples to illustrate your point more clearly for the reader. When you’re about to give an example of something you just said, you can use the following words:

For instance

To give an illustration of

To exemplify

To demonstrate

As evidence

Example: Humans have long tried to exert control over our natural environment. For instance , engineers reversed the Chicago River in 1900, causing it to permanently flow backward.

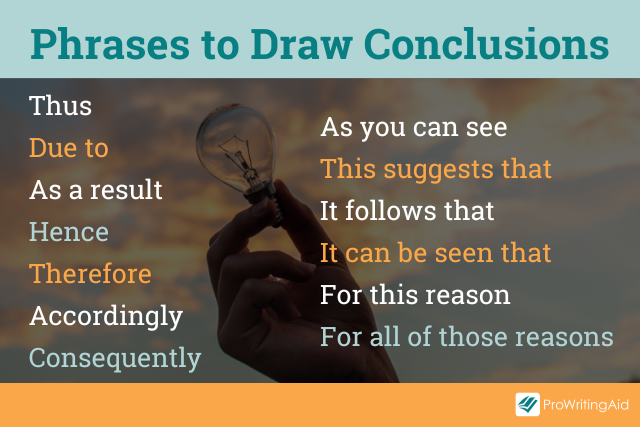

Sometimes, you’ll need to explain the impact or consequence of something you’ve just said.

When you’re drawing a conclusion from evidence you’ve presented, try using the following words:

As a result

Accordingly

As you can see

This suggests that

It follows that

It can be seen that

For this reason

For all of those reasons

Consequently

Example: “There wasn’t enough government funding to support the rest of the physics experiment. Thus , the team was forced to shut down their experiment in 1996.”

When introducing an idea that bolsters one you’ve already stated, or adds another important aspect to that same argument, you can use the following words:

What’s more

Not only…but also

Not to mention

To say nothing of

Another key point

Example: The volcanic eruption disrupted hundreds of thousands of people. Moreover , it impacted the local flora and fauna as well, causing nearly a hundred species to go extinct.

Often, you'll want to present two sides of the same argument. When you need to compare and contrast ideas, you can use the following words:

On the one hand / on the other hand

Alternatively

In contrast to

On the contrary

By contrast

In comparison

Example: On the one hand , the Black Death was undoubtedly a tragedy because it killed millions of Europeans. On the other hand , it created better living conditions for the peasants who survived.

Finally, when you’re introducing a new angle that contradicts your previous idea, you can use the following phrases:

Having said that

Differing from

In spite of

With this in mind

Provided that

Nevertheless

Nonetheless

Notwithstanding

Example: Shakespearean plays are classic works of literature that have stood the test of time. Having said that , I would argue that Shakespeare isn’t the most accessible form of literature to teach students in the twenty-first century.

Good essays include multiple types of logic. You can use a combination of the transitions above to create a strong, clear structure throughout the body of your essay.

Strong Verbs for Academic Writing

Verbs are especially important for writing clear essays. Often, you can convey a nuanced meaning simply by choosing the right verb.

You should use strong verbs that are precise and dynamic. Whenever possible, you should use an unambiguous verb, rather than a generic verb.

For example, alter and fluctuate are stronger verbs than change , because they give the reader more descriptive detail.

Here are some useful verbs that will help make your essay shine.

Verbs that show change:

Accommodate

Verbs that relate to causing or impacting something:

Verbs that show increase:

Verbs that show decrease:

Deteriorate

Verbs that relate to parts of a whole:

Comprises of

Is composed of

Constitutes

Encompasses

Incorporates

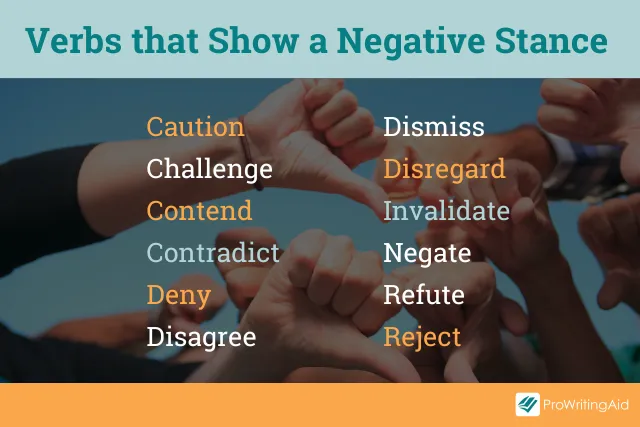

Verbs that show a negative stance:

Misconstrue

Verbs that show a positive stance:

Substantiate

Verbs that relate to drawing conclusions from evidence:

Corroborate

Demonstrate

Verbs that relate to thinking and analysis:

Contemplate

Hypothesize

Investigate

Verbs that relate to showing information in a visual format:

Useful Adjectives and Adverbs for Academic Essays

You should use adjectives and adverbs more sparingly than verbs when writing essays, since they sometimes add unnecessary fluff to sentences.

However, choosing the right adjectives and adverbs can help add detail and sophistication to your essay.

Sometimes you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is useful and should be taken seriously. Here are some adjectives that create positive emphasis:

Significant

Other times, you'll need to use an adjective to show that a finding or argument is harmful or ineffective. Here are some adjectives that create a negative emphasis:

Controversial

Insignificant

Questionable

Unnecessary

Unrealistic

Finally, you might need to use an adverb to lend nuance to a sentence, or to express a specific degree of certainty. Here are some examples of adverbs that are often used in essays:

Comprehensively

Exhaustively

Extensively

Respectively

Surprisingly

Using these words will help you successfully convey the key points you want to express. Once you’ve nailed the body of your essay, it’s time to move on to the conclusion.

The conclusion of your paper is important for synthesizing the arguments you’ve laid out and restating your thesis.

In your concluding paragraph, try using some of these essay words:

In conclusion

To summarize

In a nutshell

Given the above

As described

All things considered

Example: In conclusion , it’s imperative that we take action to address climate change before we lose our coral reefs forever.

In addition to simply summarizing the key points from the body of your essay, you should also add some final takeaways. Give the reader your final opinion and a bit of a food for thought.

To place emphasis on a certain point or a key fact, use these essay words:

Unquestionably

Undoubtedly

Particularly

Importantly

Conclusively

It should be noted

On the whole

Example: Ada Lovelace is unquestionably a powerful role model for young girls around the world, and more of our public school curricula should include her as a historical figure.

These concluding phrases will help you finish writing your essay in a strong, confident way.

There are many useful essay words out there that we didn't include in this article, because they are specific to certain topics.

If you're writing about biology, for example, you will need to use different terminology than if you're writing about literature.

So how do you improve your vocabulary skills?

The vocabulary you use in your academic writing is a toolkit you can build up over time, as long as you take the time to learn new words.

One way to increase your vocabulary is by looking up words you don’t know when you’re reading.

Try reading more books and academic articles in the field you’re writing about and jotting down all the new words you find. You can use these words to bolster your own essays.

You can also consult a dictionary or a thesaurus. When you’re using a word you’re not confident about, researching its meaning and common synonyms can help you make sure it belongs in your essay.

Don't be afraid of using simpler words. Good essay writing boils down to choosing the best word to convey what you need to say, not the fanciest word possible.

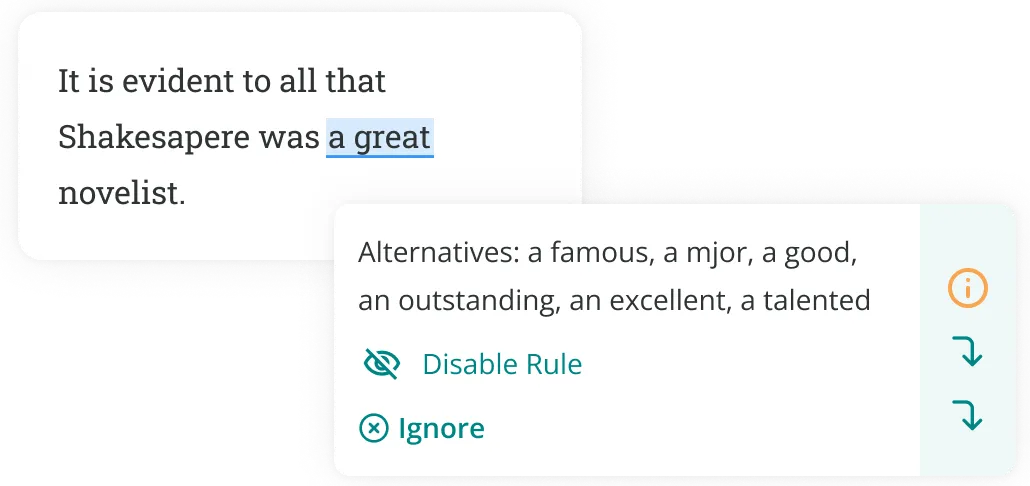

Finally, you can use ProWritingAid’s synonym tool or essay checker to find more precise and sophisticated vocabulary. Click on weak words in your essay to find stronger alternatives.

There you have it: our compilation of the best words and phrases to use in your next essay . Good luck!

Good writing = better grades

ProWritingAid will help you improve the style, strength, and clarity of all your assignments.

Hannah Yang is a speculative fiction writer who writes about all things strange and surreal. Her work has appeared in Analog Science Fiction, Apex Magazine, The Dark, and elsewhere, and two of her stories have been finalists for the Locus Award. Her favorite hobbies include watercolor painting, playing guitar, and rock climbing. You can follow her work on hannahyang.com, or subscribe to her newsletter for publication updates.

Get started with ProWritingAid

Drop us a line or let's stay in touch via :

- Master Your Homework

- Do My Homework

Researching Paper Synonyms: A Guide

This guide provides an overview of synonym research as it pertains to paper writing. Synonyms are words that have similar meanings, and when used in academic papers they can add sophistication and subtlety to the writer’s message. By using different forms of expression, writers can avoid redundancy while conveying their ideas more effectively. This guide will explain how researchers can identify appropriate synonyms for various contexts, discuss strategies for utilizing them effectively in academic writing, and provide a few key resources for locating relevant alternatives.

I. Introduction to Researching Paper Synonyms: A Guide

Ii. exploring the different types of writing papers, iii. understanding how words are used in written contexts, iv. examining examples of synonyms for commonly used paper terms, v. developing effective strategies for integrating synonymous language into academic writing, vi. utilizing online resources to enhance knowledge of discourse and vocabulary usage in scholarly papers, vii. conclusion: enhancing your use of word variation in academic writing.

Are you looking for a way to make your research paper stand out from the rest? Researching and using synonyms within an academic paper can be an effective tool that enriches writing and enhances comprehension. Synonym use is not only beneficial in expressing ideas with more clarity, but it also helps demonstrate expertise on certain topics.

In this guide, we will discuss how to effectively utilize synonyms when researching for papers. We’ll delve into what synonyms are; show you ways to look up relevant words quickly; examine which types of text lend themselves best to having their language altered; and present strategies for successfully incorporating multiple terms that still keep your writing clear.

- Handy tips :Keep track of each different term used so they don’t become repetitive or confusing

Exploring the Varied Forms of Written Composition Writing is an art form which can take many shapes and forms. A research paper is a type of written work that requires one to delve deeply into subject matter, conduct extensive research, and provide new insights or solutions for existing problems. There are several types of papers that may be assigned in English classes: essays, term papers, reports, book reviews and capstone projects. All these different pieces come with their own set of guidelines for structure and content.

The essay , arguably the most widely used form of writing assignment out there today, demands good organization as well as a thoughtful argument developed through analysis of evidence from credible sources. It should have an introduction where the topic is introduced; body paragraphs providing evidence in support or refutation; and finally a conclusion summing up all points made throughout the essay in relation to its main thesis statement. Essays could also involve creative elements such as narrative stories depending on what they are being written about! A term paper , however differs slightly since it usually centers around topics covered during class lectures over a semester period rather than something entirely based upon independent exploration by the student themselves like essays do. This means more focus needs to go into finding relevant information related to whatever has been discussed previously within class settings while developing appropriate arguments backed by source materials such as journal articles or books on said topic areas pertinent to course material already taught this semester long duration prior..

Exploring How Word Meanings Differ in Different Contexts

When writing a research paper, it is important to use accurate and precise language. To achieve this goal, one must be familiar with commonly used terms within the field of study. Fortunately, there are often many synonyms that can be used for these same words.

- Analysis: Evaluation; Investigation; Examination

This broad term encompasses any kind of in-depth examination or review conducted on a specific topic or subject matter. As such, analysis can refer to examining an existing process or system as well as studying an individual’s thought processes related to their experiences with a given situation. Synonyms such as “evaluation” and “investigation” also apply when describing the act of conducting an analysis during research paper writing.

- Conclusion: Summation; Summary; Verdict

The conclusion marks the end of your research paper by summarizing all key points discussed throughout its entirety while drawing meaningful conclusions from them based on evidence found during the investigation stage mentioned above. Herein lies why common synonyms like “summation” and “verdict” make sense when talking about reaching closure on one’s project since they provide additional ways to express what it means for something to have been concluded successfully through logical reasoning rather than leaving readers without proper guidance at its conclusionary moments!

Harnessing the Power of Synonyms

Integrating synonymous language into academic writing can be an effective way to increase clarity and precision in a paper. It adds depth to both ideas and arguments, providing readers with greater insight while also giving writers more expressive options for conveying their message. Research indicates that using synonym-rich text has been proven to enhance readability and help facilitate understanding.

One key strategy when integrating synonymous language is proper selection of words. Writers should seek out terms which accurately convey intended meaning but don’t sound overly repetitive or redundant when used within close proximity of each other in sentences or paragraphs. Varying sentence structure, grammar usage, and context clues are all important factors in helping craft well-constructed papers filled with appropriate synonymous word choice.

In today’s digitally-driven world, having an arsenal of online tools at one’s disposal is essential for achieving fluency in any language. To understand the nuances and subtleties associated with discourse and vocabulary usage when writing scholarly papers, it is crucial to have access to reliable resources.

A great place to start learning about effective word choice is a research paper synonym dictionary; these collections of words can help broaden ones understanding of different academic terms. Additionally, free English grammar websites are invaluable sources that offer guidance on how to construct sentences correctly using appropriate syntax. Beyond this, there are numerous articles available from well respected universities that explain specific aspects related to crafting quality scholarly work.

- Research Paper Synonyms

- English Grammar Websites

In conclusion, effectively using word variation in academic writing can be beneficial for all students. This practice allows for better communication of ideas and more comprehensive understanding of the written material as a whole. Here are some strategies to help you enhance your use of word variation:

- Do research. Consider synonyms or related terms that will add variety and nuance to your paper. Utilize online dictionaries, thesauruses, or other resources to find these alternatives.

- Think broadly. When considering what words could serve as possible replacements, don’t limit yourself just to single-word options—you may also want explore phrases with similar meanings.

English: The research conducted for this paper has provided a valuable guide to understanding the potential synonyms of various words in academic papers. The insights gained from this work can be used to improve the clarity and accuracy of written assignments, thus contributing to an improved learning environment. Ultimately, it is hoped that future studies will build on these findings in order to further expand our knowledge base regarding effective word choices for academic writing.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Scholarly Writing: Scholarly Writing

Introduction.

Scholarly writing is also known as academic writing. It is the genre of writing used in all academic fields. Scholarly writing is not better than journalism, fiction, or poetry; it is just a different category. Because most of us are not used to scholarly writing, it can feel unfamiliar and intimidating, but it is a skill that can be learned by immersing yourself in scholarly literature. During your studies at Walden, you will be reading, discussing, and producing scholarly writing in everything from discussion posts to dissertations. For Walden students, there are plenty of opportunities to practice this skill in a writing intensive environment.

The resources in the Grammar & Composition tab provide important foundations for scholarly writing, so please refer to those pages as well for help on scholarly writing. Similarly, scholarly writing can differ depending on style guide. Our resources follow the general guidelines of the APA manual, and you can find more APA help in the APA Style tab.

Read on to learn about a few characteristics of scholarly writing!

Writing at the Graduate Level

Writing at the graduate level can appear to be confusing and intimidating. It can be difficult to determine exactly what the scholarly voice is and how to transition to graduate-level writing. There are some elements of writing to consider when writing to a scholarly audience: word choice, tone, and effective use of evidence . If you understand and employ scholarly voice rules, you will master writing at the doctoral level.

Before you write something, ask yourself the following:

- Is this objective?

- Am I speaking as a social scientist? Am I using the literature to support my assertions?

- Could this be offensive to someone?

- Could this limit my readership?

Employing these rules when writing will help ensure that you are speaking as a social scientist. Your writing will be clear and concise, and this approach will allow your content to shine through.

Specialized Vocabulary

Scholarly authors assume that their audience is familiar with fundamental ideas and terms in their field, and they do not typically define them for the reader. Thus, the wording in scholarly writing is specialized, requiring previous knowledge on the part of the reader. You might not be able to pick up a scholarly journal in another field and easily understand its contents (although you should be able to follow the writing itself).

Take for example, the terms "EMRs" and "end-stage renal disease" in the medical field or the keywords scaffolding and differentiation in teaching. Perhaps readers outside of these fields may not be familiar with these terms. However, a reader of an article that contains these terms should still be able to understand the general flow of the writing itself.

Original Thought

Scholarly writing communicates original thought, whether through primary research or synthesis, that presents a unique perspective on previous research. In a scholarly work, the author is expected to have insights on the issue at hand, but those insights must be grounded in research, critical reading , and analysis rather than personal experience or opinion. Take a look at some examples below:

Needs Improvement: I think that childhood obesity needs to be prevented because it is bad and it causes health problems.

Better: I believe that childhood obesity must be prevented because it is linked to health problems and deaths in adults (McMillan, 2010).

Good: Georges (2002) explained that there "has never been a disease so devastating and yet so preventable as obesity" (p. 35). In fact, the number of deaths that can be linked to obesity are astounding. According to McMillan (2010), there is a direct correlation between childhood obesity and heart attacks later in their adult lives, and the American Heart Association's 2010 statistic sheet shows similar statistics: 49% of all heart attacks are preventable (AHA, 2010). Because of this correlation, childhood obesity is an issue that must be addressed and prevented to ensure the health of both children and adults.

Notice that the first example gives a personal opinion but cites no sources or research. The second example gives a bit of research but still emphasizes the personal opinion. The third example, however, still gives the writer's opinion (that childhood obesity must be addressed), but it does so by synthesizing the information from multiple sources to help persuade the reader.

Careful Citation

Scholarly writing includes careful citation of sources and the presence of a bibliography or reference list. The writing is informed by and shows engagement with the larger body of literature on the topic at hand, and all assertions are supported by relevant sources.

Crash Course in Scholarly Writing Video

Note that this video was created while APA 6 was the style guide edition in use. There may be some examples of writing that have not been updated to APA 7 guidelines.

- Crash Course in Scholarly Writing (video transcript)

Related Webinars

Didn't find what you need? Search our website or email us .

Read our website accessibility and accommodation statement .

- Next Page: Common Course Assignments

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

- I nfographics

- Show AWL words

- Subscribe to newsletter

- Incidental learning

- Incidental learning tool

- Pronunciation

- Part of speech

- Word family

- Common/uncommon

- General/Academic

- Collocation

- About vocabulary building

- AWL highlighter/gapfill

- AWL tag cloud/gapfill

- ACL highlighter/gapfill

- AFL highlighter/gapfill

- Multi highlighter

- NAWL highlighter

- AVL highlighter

- DCL highlighter

- EAWL highlighter

- MAWL highlighter

- MAVL highlighter

- MAWL/MAVL highlighter

- CAWL highlighter

- CSAVL highlighter

- SWL highlighter

- SPL highlighter

- SVL/MSVL profiler

- GSL highlighter

- NGSL highlighter

- New-GSL highlighter

- About the AWL

- AWL word finder

- AWL highlighter & gapfill

- AWL tag cloud & gapfill

- AWL word cloud

- AWL word cloud (sublist)

- About the ACL

- ACL by headword

- ACL by type

- ACL by frequency

- ACL highlighter & gapfill

- ACL mind map

- About the GSL

- GSL by frequency

- GSL alphabetical

- GSL limiter

- About technical vocab

- Secondary Vocab Lists

- Middle Sch Vocab Lists

- Science Word List

- Secondary Phrase Lists

- Nursing Collocation List

- Other specific lists

- Text profiler

- Word & phrase profiler

- Academic concordancer

- Guide to the concordancer

- Academic corpora

- Concordancers review

- Environment

- Physical Health

Show AWL words on this page.

Levels 1-5: grey Levels 6-10: orange

Show sorted lists of these words.

Any words you don't know? Look them up in the website's built-in dictionary .

Choose a dictionary . Wordnet OPTED both

- Academic vocab

The Academic Word List (AWL) The 570 headwords, and other forms, by level

For another look at the same content, check out YouTube » or Youku » , or the AWL infographic » .

This page describes the Academic Word List (AWL), giving information on what the AWL is , as well as a complete list of all words in the AWL . The list is rather static. More dynamic tools for understanding and using the AWL words can be found in other sections of the website, namely the AWL highlighter and gapfill maker , AWL tag cloud and gapfill maker , the AWL finder , and a vocabulary profiler . Other pages also contain information on how to use word lists as well as more detailed information on the main different word lists available for academic study .

What is the AWL?

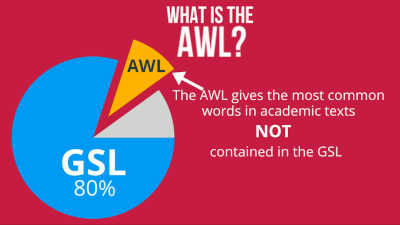

The Academic Word List (AWL), developed by Averil Coxhead at Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand, contains 570 word families which frequently appear in academic texts, but which are not contained in the General Service List (GSL) . When compiling the list, the author found that the AWL covers around 10% of words in academic texts; if you are familiar with words in the GSL, which covers around 80% of words in written texts, you would have knowledge of approximately 90% of words in academic texts. The words in the AWL are not connected with any particular subject, meaning they are useful for all students.

The 570 word families of the AWL are divided into 10 lists (called sublists) according to how frequent they are. Sublist 1 has the most frequent word families, sublist 2 the next most frequent word families, up to sublist 10, which has the least frequent. Each sublist contains 60 word families, except for sublist 10, which only has 30.

The list below contains all 570 headwords in the AWL, along with sublist number, and related word forms. All words contain hyperlinks to the Wordnet dictionary , hosted on this site (definitions open in an alert box on the same page).

There is a downloadable copy of this list , with study guidance, in the vocabulary resources section .

Check out the Quizzes section for exercises to practise using words in the AWL.

The Academic Word List

Below is a complete copy of the Academic Word List. It shows headwords, sublist, and individual word forms. There are hyperlinks giving definitions. There is an alternative version of the list, with frequency information for individual word forms , on another page.

GET FREE EBOOK

Like the website? Try the books. This extract from Unlock the Academic Wordlist: Sublists 1-3 contains all sublist 1 words, plus exercises, answers and more!

Author: Sheldon Smith ‖ Last modified: 05 March 2024.

Sheldon Smith is the founder and editor of EAPFoundation.com. He has been teaching English for Academic Purposes since 2004. Find out more about him in the about section and connect with him on Twitter , Facebook and LinkedIn .

The AWL highlighter allows you to highlight words from the AWL (Academic Word List) in any text you choose.

The Academic Word List (AWL) contains 570 word families which frequently appear in academic texts.

The Academic Collocation List (ACL) is a list containing 2,469 of the most frequent and useful collocations which occur in written academic English.

Academic vocabulary consists of general words, non-general academic words, and technical words.

Resources for vocabulary contains additional activities and information (requires users to be logged in).

Learning vocabulary depends on knowing how much to learn, the type of vocabulary to study, and how to study it properly.

Places on our 2024 summer school are filling fast. Don’t miss out. Enrol now to avoid disappointment

- 40 Useful Words and Phrases for Top-Notch Essays

To be truly brilliant, an essay needs to utilise the right language. You could make a great point, but if it’s not intelligently articulated, you almost needn’t have bothered.

Developing the language skills to build an argument and to write persuasively is crucial if you’re to write outstanding essays every time. In this article, we’re going to equip you with the words and phrases you need to write a top-notch essay, along with examples of how to utilise them.

It’s by no means an exhaustive list, and there will often be other ways of using the words and phrases we describe that we won’t have room to include, but there should be more than enough below to help you make an instant improvement to your essay-writing skills.

If you’re interested in developing your language and persuasive skills, Oxford Royale offers summer courses at its Oxford Summer School , Cambridge Summer School , London Summer School , San Francisco Summer School and Yale Summer School . You can study courses to learn english , prepare for careers in law , medicine , business , engineering and leadership.

General explaining

Let’s start by looking at language for general explanations of complex points.

1. In order to

Usage: “In order to” can be used to introduce an explanation for the purpose of an argument. Example: “In order to understand X, we need first to understand Y.”

2. In other words

Usage: Use “in other words” when you want to express something in a different way (more simply), to make it easier to understand, or to emphasise or expand on a point. Example: “Frogs are amphibians. In other words, they live on the land and in the water.”

3. To put it another way

Usage: This phrase is another way of saying “in other words”, and can be used in particularly complex points, when you feel that an alternative way of wording a problem may help the reader achieve a better understanding of its significance. Example: “Plants rely on photosynthesis. To put it another way, they will die without the sun.”

4. That is to say

Usage: “That is” and “that is to say” can be used to add further detail to your explanation, or to be more precise. Example: “Whales are mammals. That is to say, they must breathe air.”

5. To that end

Usage: Use “to that end” or “to this end” in a similar way to “in order to” or “so”. Example: “Zoologists have long sought to understand how animals communicate with each other. To that end, a new study has been launched that looks at elephant sounds and their possible meanings.”

Adding additional information to support a point

Students often make the mistake of using synonyms of “and” each time they want to add further information in support of a point they’re making, or to build an argument . Here are some cleverer ways of doing this.

6. Moreover

Usage: Employ “moreover” at the start of a sentence to add extra information in support of a point you’re making. Example: “Moreover, the results of a recent piece of research provide compelling evidence in support of…”

7. Furthermore

Usage:This is also generally used at the start of a sentence, to add extra information. Example: “Furthermore, there is evidence to suggest that…”

8. What’s more

Usage: This is used in the same way as “moreover” and “furthermore”. Example: “What’s more, this isn’t the only evidence that supports this hypothesis.”

9. Likewise

Usage: Use “likewise” when you want to talk about something that agrees with what you’ve just mentioned. Example: “Scholar A believes X. Likewise, Scholar B argues compellingly in favour of this point of view.”

10. Similarly

Usage: Use “similarly” in the same way as “likewise”. Example: “Audiences at the time reacted with shock to Beethoven’s new work, because it was very different to what they were used to. Similarly, we have a tendency to react with surprise to the unfamiliar.”

11. Another key thing to remember

Usage: Use the phrase “another key point to remember” or “another key fact to remember” to introduce additional facts without using the word “also”. Example: “As a Romantic, Blake was a proponent of a closer relationship between humans and nature. Another key point to remember is that Blake was writing during the Industrial Revolution, which had a major impact on the world around him.”

12. As well as

Usage: Use “as well as” instead of “also” or “and”. Example: “Scholar A argued that this was due to X, as well as Y.”

13. Not only… but also

Usage: This wording is used to add an extra piece of information, often something that’s in some way more surprising or unexpected than the first piece of information. Example: “Not only did Edmund Hillary have the honour of being the first to reach the summit of Everest, but he was also appointed Knight Commander of the Order of the British Empire.”

14. Coupled with

Usage: Used when considering two or more arguments at a time. Example: “Coupled with the literary evidence, the statistics paint a compelling view of…”

15. Firstly, secondly, thirdly…

Usage: This can be used to structure an argument, presenting facts clearly one after the other. Example: “There are many points in support of this view. Firstly, X. Secondly, Y. And thirdly, Z.

16. Not to mention/to say nothing of

Usage: “Not to mention” and “to say nothing of” can be used to add extra information with a bit of emphasis. Example: “The war caused unprecedented suffering to millions of people, not to mention its impact on the country’s economy.”

Words and phrases for demonstrating contrast

When you’re developing an argument, you will often need to present contrasting or opposing opinions or evidence – “it could show this, but it could also show this”, or “X says this, but Y disagrees”. This section covers words you can use instead of the “but” in these examples, to make your writing sound more intelligent and interesting.

17. However

Usage: Use “however” to introduce a point that disagrees with what you’ve just said. Example: “Scholar A thinks this. However, Scholar B reached a different conclusion.”

18. On the other hand

Usage: Usage of this phrase includes introducing a contrasting interpretation of the same piece of evidence, a different piece of evidence that suggests something else, or an opposing opinion. Example: “The historical evidence appears to suggest a clear-cut situation. On the other hand, the archaeological evidence presents a somewhat less straightforward picture of what happened that day.”

19. Having said that

Usage: Used in a similar manner to “on the other hand” or “but”. Example: “The historians are unanimous in telling us X, an agreement that suggests that this version of events must be an accurate account. Having said that, the archaeology tells a different story.”

20. By contrast/in comparison

Usage: Use “by contrast” or “in comparison” when you’re comparing and contrasting pieces of evidence. Example: “Scholar A’s opinion, then, is based on insufficient evidence. By contrast, Scholar B’s opinion seems more plausible.”

21. Then again

Usage: Use this to cast doubt on an assertion. Example: “Writer A asserts that this was the reason for what happened. Then again, it’s possible that he was being paid to say this.”

22. That said

Usage: This is used in the same way as “then again”. Example: “The evidence ostensibly appears to point to this conclusion. That said, much of the evidence is unreliable at best.”

Usage: Use this when you want to introduce a contrasting idea. Example: “Much of scholarship has focused on this evidence. Yet not everyone agrees that this is the most important aspect of the situation.”

Adding a proviso or acknowledging reservations

Sometimes, you may need to acknowledge a shortfalling in a piece of evidence, or add a proviso. Here are some ways of doing so.

24. Despite this

Usage: Use “despite this” or “in spite of this” when you want to outline a point that stands regardless of a shortfalling in the evidence. Example: “The sample size was small, but the results were important despite this.”

25. With this in mind

Usage: Use this when you want your reader to consider a point in the knowledge of something else. Example: “We’ve seen that the methods used in the 19th century study did not always live up to the rigorous standards expected in scientific research today, which makes it difficult to draw definite conclusions. With this in mind, let’s look at a more recent study to see how the results compare.”

26. Provided that

Usage: This means “on condition that”. You can also say “providing that” or just “providing” to mean the same thing. Example: “We may use this as evidence to support our argument, provided that we bear in mind the limitations of the methods used to obtain it.”

27. In view of/in light of

Usage: These phrases are used when something has shed light on something else. Example: “In light of the evidence from the 2013 study, we have a better understanding of…”

28. Nonetheless

Usage: This is similar to “despite this”. Example: “The study had its limitations, but it was nonetheless groundbreaking for its day.”

29. Nevertheless

Usage: This is the same as “nonetheless”. Example: “The study was flawed, but it was important nevertheless.”

30. Notwithstanding

Usage: This is another way of saying “nonetheless”. Example: “Notwithstanding the limitations of the methodology used, it was an important study in the development of how we view the workings of the human mind.”

Giving examples

Good essays always back up points with examples, but it’s going to get boring if you use the expression “for example” every time. Here are a couple of other ways of saying the same thing.

31. For instance

Example: “Some birds migrate to avoid harsher winter climates. Swallows, for instance, leave the UK in early winter and fly south…”

32. To give an illustration

Example: “To give an illustration of what I mean, let’s look at the case of…”

Signifying importance

When you want to demonstrate that a point is particularly important, there are several ways of highlighting it as such.

33. Significantly

Usage: Used to introduce a point that is loaded with meaning that might not be immediately apparent. Example: “Significantly, Tacitus omits to tell us the kind of gossip prevalent in Suetonius’ accounts of the same period.”

34. Notably

Usage: This can be used to mean “significantly” (as above), and it can also be used interchangeably with “in particular” (the example below demonstrates the first of these ways of using it). Example: “Actual figures are notably absent from Scholar A’s analysis.”

35. Importantly

Usage: Use “importantly” interchangeably with “significantly”. Example: “Importantly, Scholar A was being employed by X when he wrote this work, and was presumably therefore under pressure to portray the situation more favourably than he perhaps might otherwise have done.”

Summarising

You’ve almost made it to the end of the essay, but your work isn’t over yet. You need to end by wrapping up everything you’ve talked about, showing that you’ve considered the arguments on both sides and reached the most likely conclusion. Here are some words and phrases to help you.

36. In conclusion

Usage: Typically used to introduce the concluding paragraph or sentence of an essay, summarising what you’ve discussed in a broad overview. Example: “In conclusion, the evidence points almost exclusively to Argument A.”

37. Above all

Usage: Used to signify what you believe to be the most significant point, and the main takeaway from the essay. Example: “Above all, it seems pertinent to remember that…”

38. Persuasive

Usage: This is a useful word to use when summarising which argument you find most convincing. Example: “Scholar A’s point – that Constanze Mozart was motivated by financial gain – seems to me to be the most persuasive argument for her actions following Mozart’s death.”

39. Compelling

Usage: Use in the same way as “persuasive” above. Example: “The most compelling argument is presented by Scholar A.”

40. All things considered

Usage: This means “taking everything into account”. Example: “All things considered, it seems reasonable to assume that…”

How many of these words and phrases will you get into your next essay? And are any of your favourite essay terms missing from our list? Let us know in the comments below, or get in touch here to find out more about courses that can help you with your essays.

At Oxford Royale Academy, we offer a number of summer school courses for young people who are keen to improve their essay writing skills. Click here to apply for one of our courses today, including law , business , medicine and engineering .

Comments are closed.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

What Is a Scholarly Source? | Beginner's Guide

Scholarly sources (aka academic sources) are written by experts in their field. They’re supported by evidence and informed by up-to-date research.

As a student, you should aim to use scholarly sources in your research and to follow the same kinds of scholarly conventions in your own writing. This means knowing how to:

- Distinguish between different types of sources

- Find sources for your research

- Evaluate the relevance and credibility of sources

- Integrate sources into your text and cite them correctly

Table of contents

What is a scholarly source, types of sources, how do i find scholarly sources, how do i evaluate sources, integrating and citing sources, frequently asked questions about scholarly sources.

Scholarly sources are written by experts and are intended to advance knowledge in a specific field of study.

They serve a range of purposes, including:

- Communicating original research

- Contributing to the theoretical foundations of a discipline

- Summarizing current research trends

Scholarly sources use formal and technical language, as they’re written for readers with knowledge of the discipline.

They should:

- Aim to educate or inform

- Support their arguments and conclusions with evidence

- Be attributed to a specific author or authors, also indicating their academic qualifications

They should not:

- Present a biased perspective

- Contain spelling or grammatical errors

- Rely on appeals to emotion

Scholarly sources should be well structured and contain information on the methodology used in the research they describe. They may also include a literature review . They contain formal citations wherever information from other sources is referenced.

Scholarly books are typically published by a university press or academic publisher. Scholarly articles are typically longer than popular articles. They are published in discipline-specific journals and are typically peer-reviewed.

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

Various types of sources are used in academic writing. Different sources may become relevant at different stages of the research process .

The sources commonly used in academic writing include:

- Academic journals

- Scholarly books

- Encyclopedias

Depending on your research topic and approach, each of these sources falls into one of three categories:

- Primary sources provide direct evidence about your research topic (e.g., a diary entry from a historical figure).

- Secondary sources interpret or provide commentary on primary sources (e.g., an academic book).

- Tertiary sources summarize or consolidate primary and secondary sources but don’t provide original insights (e.g., a bibliography).

Tertiary sources are not typically cited in academic writing , but they can be used to learn more about a topic.

If you’re unsure what kinds of sources are relevant to your topic, consult your instructor.

In practically any kind of research, you’ll have to find sources to engage with. How you find your sources will depend on what you’re looking for. The main places to look for sources are:

- Research databases: A good place to start is with Google Scholar . Also consult the website of your institution’s library to see what academic databases they provide access to.

- Your institution’s library: Consult your library’s catalog to find relevant sources. Browse the shelves of relevant sections. You can also consult the bibliographies of any relevant sources to find further useful sources.

When using academic databases or search engines, you can use Boolean operators to include or exclude keywords to refine your results.

Knowing how to evaluate sources is one of the most important information literacy skills. It helps you ensure that the sources you use are scholarly, credible , and relevant to your topic, and that they contain coherent and informed arguments.

- Evaluate the credibility of a source using the CRAAP test or lateral reading . These help you assess a source’s currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, and purpose.

- Evaluate a source’s relevance by analyzing how the author engages with key debates, major publications or scholars, gaps in existing knowledge, and research trends.

- Evaluate a source’s arguments by analyzing the relationship between a source’s claims and the evidence used to support them.

When you are evaluating sources, it’s important to think critically and to be aware of your own biases.

Scribbr Citation Checker New

The AI-powered Citation Checker helps you avoid common mistakes such as:

- Missing commas and periods

- Incorrect usage of “et al.”

- Ampersands (&) in narrative citations

- Missing reference entries

In addition to finding and evaluating sources, you should also know how to integrate sources into your writing. You can use signal phrases to introduce sources in your text, and then integrate them by:

- Quoting : This means including the exact words of another source in your paper. The quoted text must be enclosed in quotation marks or (for longer quotes) presented as a block quote . Quote a source when the meaning is difficult to convey in different words or when you want to analyze the language itself.

- Paraphrasing : This means putting another person’s ideas into your own words. It allows you to integrate sources more smoothly into your text, maintaining a consistent voice. It also shows that you have understood the meaning of the source. You can do this by yourself or use a paraphrasing tool .

- Summarizing : This means giving an overview of the essential points of a source. Summaries should be much shorter than the original text. You should describe the key points in your own words and not quote from the original text.

You must cite a source whenever you reference someone else’s work. This gives credit to the author. Failing to cite your sources is regarded as plagiarism and could get you in trouble.

The most common citation styles are APA , MLA , and Chicago style . Each citation style has specific rules for formatting citations.

The easiest way to create accurate citations is to use the free Scribbr Citation Generator . Simply enter the source title, URL, or DOI , and the generator creates your citation automatically.

Generate accurate citations with Scribbr

Scholarly sources are written by experts in their field and are typically subjected to peer review . They are intended for a scholarly audience, include a full bibliography, and use scholarly or technical language. For these reasons, they are typically considered credible sources .

Popular sources like magazines and news articles are typically written by journalists. These types of sources usually don’t include a bibliography and are written for a popular, rather than academic, audience. They are not always reliable and may be written from a biased or uninformed perspective, but they can still be cited in some contexts.

There are many types of sources commonly used in research. These include:

- Journal articles

You’ll likely use a variety of these sources throughout the research process , and the kinds of sources you use will depend on your research topic and goals.

It is important to find credible sources and use those that you can be sure are sufficiently scholarly .

- Consult your institute’s library to find out what books, journals, research databases, and other types of sources they provide access to.

- Look for books published by respected academic publishing houses and university presses, as these are typically considered trustworthy sources.

- Look for journals that use a peer review process. This means that experts in the field assess the quality and credibility of an article before it is published.

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

When searching for sources in databases, think of specific keywords that are relevant to your topic , and consider variations on them or synonyms that might be relevant.

Once you have a clear idea of your research parameters and key terms, choose a database that is relevant to your research (e.g., Medline, JSTOR, Project MUSE).

Find out if the database has a “subject search” option. This can help to refine your search. Use Boolean operators to combine your keywords, exclude specific search terms, and search exact phrases to find the most relevant sources.

Is this article helpful?

Other students also liked.

- Types of Sources Explained | Examples & Tips

- How to Find Sources | Scholarly Articles, Books, Etc.

- Evaluating Sources | Methods & Examples

More interesting articles

- Applying the CRAAP Test & Evaluating Sources

- Boolean Operators | Quick Guide, Examples & Tips

- How to Block Quote | Length, Format and Examples

- How to Integrate Sources | Explanation & Examples

- How to Paraphrase | Step-by-Step Guide & Examples

- How to Quote | Citing Quotes in APA, MLA & Chicago

- How to Write a Summary | Guide & Examples

- Primary vs. Secondary Sources | Difference & Examples

- Signal Phrases | Definition, Explanation & Examples

- Student Guide: Information Literacy | Meaning & Examples

- Synthesizing Sources | Examples & Synthesis Matrix

- Tertiary Sources Explained | Quick Guide & Examples

- What Are Credible Sources & How to Spot Them | Examples

- What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples

"I thought AI Proofreading was useless but.."

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Academic Phrasebank

- GENERAL LANGUAGE FUNCTIONS

- Being cautious

- Being critical

- Classifying and listing

- Compare and contrast

- Defining terms

- Describing trends

- Describing quantities

- Explaining causality

- Giving examples

- Signalling transition

- Writing about the past

The Academic Phrasebank is a general resource for academic writers. It aims to provide you with examples of some of the phraseological ‘nuts and bolts’ of writing organised according to the main sections of a research paper or dissertation (see the top menu ). Other phrases are listed under the more general communicative functions of academic writing (see the menu on the left). The resource should be particularly useful for writers who need to report their research work. The phrases, and the headings under which they are listed, can be used simply to assist you in thinking about the content and organisation of your own writing, or the phrases can be incorporated into your writing where this is appropriate. In most cases, a certain amount of creativity and adaptation will be necessary when a phrase is used. The items in the Academic Phrasebank are mostly content neutral and generic in nature; in using them, therefore, you are not stealing other people’s ideas and this does not constitute plagiarism. For some of the entries, specific content words have been included for illustrative purposes, and these should be substituted when the phrases are used. The resource was designed primarily for academic and scientific writers who are non-native speakers of English. However, native speaker writers may still find much of the material helpful. In fact, recent data suggest that the majority of users are native speakers of English. More about Academic Phrasebank .

This site was created by John Morley .

Academic Phrasebank is the Intellectual Property of the University of Manchester.

Copyright © 2023 The University of Manchester

+44 (0) 161 306 6000

The University of Manchester Oxford Rd Manchester M13 9PL UK

Connect With Us

The University of Manchester

A.I.-Generated Garbage Is Polluting Our Culture

By Erik Hoel

Mr. Hoel is a neuroscientist and novelist and the author of The Intrinsic Perspective newsletter.

Increasingly, mounds of synthetic A.I.-generated outputs drift across our feeds and our searches. The stakes go far beyond what’s on our screens. The entire culture is becoming affected by A.I.’s runoff, an insidious creep into our most important institutions.

Consider science. Right after the blockbuster release of GPT-4, the latest artificial intelligence model from OpenAI and one of the most advanced in existence, the language of scientific research began to mutate. Especially within the field of A.I. itself.

Adjectives associated with A.I.-generated text have increased in peer reviews of scientific papers about A.I.

Frequency of adjectives per one million words

Commendable

A study published this month examined scientists’ peer reviews — researchers’ official pronouncements on others’ work that form the bedrock of scientific progress — across a number of high-profile and prestigious scientific conferences studying A.I. At one such conference, those peer reviews used the word “meticulous” more than 34 times as often as reviews did the previous year. Use of “commendable” was around 10 times as frequent, and “intricate,” 11 times. Other major conferences showed similar patterns.

Such phrasings are, of course, some of the favorite buzzwords of modern large language models like ChatGPT. In other words, significant numbers of researchers at A.I. conferences were caught handing their peer review of others’ work over to A.I. — or, at minimum, writing them with lots of A.I. assistance. And the closer to the deadline the submitted reviews were received, the more A.I. usage was found in them.

If this makes you uncomfortable — especially given A.I.’s current unreliability — or if you think that maybe it shouldn’t be A.I.s reviewing science but the scientists themselves, those feelings highlight the paradox at the core of this technology: It’s unclear what the ethical line is between scam and regular usage. Some A.I.-generated scams are easy to identify, like the medical journal paper featuring a cartoon rat sporting enormous genitalia. Many others are more insidious, like the mislabeled and hallucinated regulatory pathway described in that same paper — a paper that was peer reviewed as well (perhaps, one might speculate, by another A.I.?).

What about when A.I. is used in one of its intended ways — to assist with writing? Recently, there was an uproar when it became obvious that simple searches of scientific databases returned phrases like “As an A.I. language model” in places where authors relying on A.I. had forgotten to cover their tracks. If the same authors had simply deleted those accidental watermarks, would their use of A.I. to write their papers have been fine?

What’s going on in science is a microcosm of a much bigger problem. Post on social media? Any viral post on X now almost certainly includes A.I.-generated replies, from summaries of the original post to reactions written in ChatGPT’s bland Wikipedia-voice, all to farm for follows. Instagram is filling up with A.I.-generated models, Spotify with A.I.-generated songs. Publish a book? Soon after, on Amazon there will often appear A.I.-generated “workbooks” for sale that supposedly accompany your book (which are incorrect in their content; I know because this happened to me). Top Google search results are now often A.I.-generated images or articles. Major media outlets like Sports Illustrated have been creating A.I.-generated articles attributed to equally fake author profiles. Marketers who sell search engine optimization methods openly brag about using A.I. to create thousands of spammed articles to steal traffic from competitors.

Then there is the growing use of generative A.I. to scale the creation of cheap synthetic videos for children on YouTube. Some example outputs are Lovecraftian horrors, like music videos about parrots in which the birds have eyes within eyes, beaks within beaks, morphing unfathomably while singing in an artificial voice, “The parrot in the tree says hello, hello!” The narratives make no sense, characters appear and disappear randomly, and basic facts like the names of shapes are wrong. After I identified a number of such suspicious channels on my newsletter, The Intrinsic Perspective, Wired found evidence of generative A.I. use in the production pipelines of some accounts with hundreds of thousands or even millions of subscribers.

As a neuroscientist, this worries me. Isn’t it possible that human culture contains within it cognitive micronutrients — things like cohesive sentences, narrations and character continuity — that developing brains need? Einstein supposedly said : “If you want your children to be intelligent, read them fairy tales. If you want them to be very intelligent, read them more fairy tales.” But what happens when a toddler is consuming mostly A.I.-generated dream-slop? We find ourselves in the midst of a vast developmental experiment.

There’s so much synthetic garbage on the internet now that A.I. companies and researchers are themselves worried, not about the health of the culture, but about what’s going to happen with their models. As A.I. capabilities ramped up in 2022, I wrote on the risk of culture’s becoming so inundated with A.I. creations that when future A.I.s are trained, the previous A.I. output will leak into the training set, leading to a future of copies of copies of copies, as content became ever more stereotyped and predictable. In 2023 researchers introduced a technical term for how this risk affected A.I. training: model collapse . In a way, we and these companies are in the same boat, paddling through the same sludge streaming into our cultural ocean.

With that unpleasant analogy in mind, it’s worth looking to what is arguably the clearest historical analogy for our current situation: the environmental movement and climate change. For just as companies and individuals were driven to pollute by the inexorable economics of it, so, too, is A.I.’s cultural pollution driven by a rational decision to fill the internet’s voracious appetite for content as cheaply as possible. While environmental problems are nowhere near solved, there has been undeniable progress that has kept our cities mostly free of smog and our lakes mostly free of sewage. How?

Before any specific policy solution was the acknowledgment that environmental pollution was a problem in need of outside legislation. Influential to this view was a perspective developed in 1968 by Garrett Hardin, a biologist and ecologist. Dr. Hardin emphasized that the problem of pollution was driven by people acting in their own interest, and that therefore “we are locked into a system of ‘fouling our own nest,’ so long as we behave only as independent, rational, free-enterprisers.” He summed up the problem as a “tragedy of the commons.” This framing was instrumental for the environmental movement, which would come to rely on government regulation to do what companies alone could or would not.

Once again we find ourselves enacting a tragedy of the commons: short-term economic self-interest encourages using cheap A.I. content to maximize clicks and views, which in turn pollutes our culture and even weakens our grasp on reality. And so far, major A.I. companies are refusing to pursue advanced ways to identify A.I.’s handiwork — which they could do by adding subtle statistical patterns hidden in word use or in the pixels of images.

A common justification for inaction is that human editors can always fiddle around with whatever patterns are used if they know enough. Yet many of the issues we’re experiencing are not caused by motivated and technically skilled malicious actors; they’re caused mostly by regular users’ not adhering to a line of ethical use so fine as to be nigh nonexistent. Most would be uninterested in advanced countermeasures to statistical patterns enforced into outputs that should, ideally, mark them as A.I.-generated.

That’s why the independent researchers were able to detect A.I. outputs in the peer review system with surprisingly high accuracy: They actually tried. Similarly, right now teachers across the nation have created home-brewed output-side detection methods , like adding hidden requests for patterns of word use to essay prompts that appear only when copied and pasted.

In particular, A.I. companies appear opposed to any patterns baked into their output that can improve A.I.-detection efforts to reasonable levels, perhaps because they fear that enforcing such patterns might interfere with the model’s performance by constraining its outputs too much — although there is no current evidence this is a risk. Despite public pledges to develop more advanced watermarking, it’s increasingly clear that the companies are dragging their feet because it goes against the A.I. industry’s bottom line to have detectable products.

To deal with this corporate refusal to act we need the equivalent of a Clean Air Act: a Clean Internet Act. Perhaps the simplest solution would be to legislatively force advanced watermarking intrinsic to generated outputs, like patterns not easily removable. Just as the 20th century required extensive interventions to protect the shared environment, the 21st century is going to require extensive interventions to protect a different, but equally critical, common resource, one we haven’t noticed up until now since it was never under threat: our shared human culture.

Erik Hoel is a neuroscientist, a novelist and the author of The Intrinsic Perspective newsletter.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here’s our email: [email protected] .

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Instagram , TikTok , WhatsApp , X and Threads .

Synonym of the day

Attend is a synonym of nurse, attend is another word for nurse.

✅ Nurse means to look after someone carefully ( I nursed my friend through their illness ).

✅ Attend means to take care of and devote yourself to someone ( The doctor attended her every day ).

✅ Both of these words mean to take care of someone, but they can also mean to look after something, like your health or your finances ( I carefully nursed my savings ; I attended my own boundaries ).

See all synonyms for nurse

Sign Up Now For Synonym Of The Day

- By clicking "I'M IN", you are accepting Dictionary.com Terms & Conditions and Privacy policies.

- Name This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

escapade is a synonym of caper

Escapade is another word for caper.

✅ A caper is a lighthearted or frivolous activity, often a prank or an episode of silliness ( We had to put a stop to her candy hiding capers ).

✅ An escapade is a prank or generally reckless but lighthearted activity ( Their youthful escapades were famous all over town ).

✅ Both of these terms often refer to a childish or silly activity.

✅ Caper and escapade can also refer to illegal acts, but in a more lighthearted way ( After that escapade with my cousins, I thought it best to lay low ; I was reading about a caper committed by a cat burglar ).

See all synonyms for caper

- Email This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

clog is a synonym of block

Clog is another word for block.

✅ Block means to obstruct something, generally with obstacles ( The rock had blocked the mouth of the tunnel ).

✅ Clog means to obstruct something, often with something thick, sticky, or built up over time ( The debris clogged the pipes ).

✅ Both of these words mean to obstruct a way or path ( Water builds up in the tub if you clog the drain ).

✅ Block sometimes suggests that a route has been obstructed on purpose ( They blocked the roads for safety during the parade ), whereas clog suggests an accident or negligence.

See all synonyms for block

Start every day with the Synonym of the Day right in your inbox

- Apr 04, 2024 renowned

- Apr 03, 2024 enliven

- Apr 02, 2024 downtime

- Apr 01, 2024 auspicious

- Mar 31, 2024 upbeat

- Mar 30, 2024 grouchy

- Mar 29, 2024 settled

- Mar 28, 2024 belligerent

- Mar 27, 2024 surety

Carolyn Hax: A second career as an author nets three books, zero spousal support

Dear Carolyn: Is it unreasonable of me to want my spouse to congratulate me? When I retired, I started writing and have now published three books and several magazine articles. While I’m far from a bestseller, my spouse has never said anything positive — or anything at all — when they were published.

I don’t expect flowers or a special dinner, but some kind of recognition would be nice. Am I being unreasonable?

Author: I use this answer sparingly, for obvious reasons, but here I think it’s apt:

The problem lies almost as much in your asking me as it does in your spouse’s silence.

Let’s back all the way up for a sec, to the beginning: What did you say to your spouse about the nonresponse when you published your first book?

First! Book! I mean, newspaper writers write a lot of books — so I know writers of big, little, multiple and best-selling books. And every time it’s a Big Deal. So much work.

About Carolyn Hax

Therefore, a notable thing happened to launch your writing career — and a notable thing did not happen in your marriage in response.

Yet we are talking about it now as if you haven’t broached the subject with your spouse, ever. So I am wondering what you said or did when you first witnessed the yawning void where a loved one’s normal supportive gestures would have been. Even superficial performative ones (in the event of differing tastes).

The response I’d expect is along these lines: “I just did something big; at least, it was big for me — and when you let a milestone like that go by without saying anything to me at all, I was stunned, and I still feel hurt.”

If you haven’t been that direct — if instead you’ve poked and nudged around the subject hoping your spouse would volunteer … something — then we’re long past treating this as a narrowly defined spousal failure to take you out to a celebratory dinner.

Because what you’re telling me here is the time between now and your last real conversation with your spouse can be measured in book publications. It has been at least three book publications since you and your spouse last told each other the truth.

Please give that idea careful thought. Weigh for how long and to what extent your marriage has calcified, then use those two data points to get at the why.

Then invite your spouse to talk. Really talk. And listen.

Congratulations on your new career, by the way, and good luck.

Dear Carolyn: My sister “Wendy” has always been the “marches to her own drummer” sibling. She’s smart, has a terrific job, a loving family, etc., but has always seemed a little out of step with the rest of the world.

Several years ago, “Liz” — another sister — took me aside and said she and her husband had started to think Wendy was somewhere on the autism spectrum. I felt a lot of Wendy-related things immediately click into place in my head and make sense.

Liz feels very strongly that we should say and do NOTHING. My feeling is equally strong in the other direction. I have two dear school friends who weren’t diagnosed with autism until their 50s. Both shared with me their enormous sense of relief and self-acceptance stemming from this diagnosis.

I have even suggested we share our thoughts with Wendy’s husband and allow him to raise the subject with Wendy in some gentle, organic way. Liz nixes this as well. I would really appreciate your thoughts.

— Indiana Sibling

Indiana Sibling: If you can forgive me for not weighing in on whether and what to tell Wendy, then I might have something useful to say about you and Liz.

You are not a “we” here. You are not joined by restrictions on privileged information, because Liz did not give you information that only she has access to or is supposed to have.

Liz didn’t give you information at all, in fact. Not about Wendy. All you got from Liz were her thoughts. You now have your thoughts, which you can give or not to anyone as you see fit.

You and Liz each know as much about Wendy as you ever did.

So, again, there’s no “we” in any conversations you do or don’t have with Wendy about information you don’t have. If you want to talk to Wendy someday about your experiences with your friends and connections you made to Wendy, then that’s your prerogative.

I do recommend talking about this with Liz before saying boo to Wendy, though, if that’s the way you decide to go here — and also saying nothing of Liz to Wendy. That’s basic accountability hygiene.

I also recommend thinking of Wendy in terms of Wendy and not in terms of your other friends. You can be so right about their sense of relief and still be wrong that Wendy will share it.

Maybe get out of your certainty for a bit, and really listen for things Liz understands about Wendy that you don’t (or vice versa). And that Wendy accepts in herself.

More from Carolyn Hax

From the archive:

They refused to host sick dog; mother-in-law is ‘livid’

A stay-at-home mom trapped in a career woman’s life

Estranged dad pressures child who wants ‘no contact ever’

Has breast cancer treatment altered her dating prospects?

Can’t understand why brother blocked your number? Hello?