Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies, 7th edition

At the crossroads of corporate strategy and finance lies valuation. This book enables everyone, from the budding professional to the seasoned manager, to excel at measuring and maximizing shareholder and company value.

John Wiley & Sons, 2020 | Tim Koller, Marc Goedhart, David Wessels

Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies , celebrating 30 years in print, is now in its seventh edition (John Wiley & Sons, June 2020). Carefully revised and updated, this edition includes new insights on topics such as digital; environmental, social, and governance issues; and long-term investing, as well as fresh case studies.

Clear, accessible chapters cover the fundamental principles of value creation, analysis and forecasting of performance, capital structure and dividends, valuation of high-growth companies, and much more. Financial Times calls the book “one of the practitioners’ best guides to valuation.”

This book provides useful information, such as the following, for financial professionals in any location:

- complete, detailed guidance on every crucial aspect of corporate valuation

- explanation of the strategies, techniques, and nuances of valuation that every manager needs to know

- details on both core and advanced valuation techniques and management strategies

In addition, the book’s companion website provides more information on key issues in valuation, including through videos, discussions of trending topics, and real-world valuation examples from capital markets.

Valuation: Measuring and Managing the Value of Companies is a handbook that can help managers, investors, and students understand how to foster corporate health and create value for the future—goals that have never been more timely.

Inside Valuation

With the authors, in the news, yahoo finance “on the move”, valuewalk’s value talks, the startup life, about the authors.

Tim Koller is a partner in McKinsey's Stamford, Connecticut, office, where he is a founder of McKinsey's Strategy and Corporate Finance Insights team, a global group of corporate-finance expert consultants. In his 35 years in consulting, Tim has served clients globally on corporate strategy and capital markets, mergers and acquisitions transactions, and strategic planning and resource allocation. He leads the firm's research activities in valuation and capital markets. Before joining McKinsey, he worked with Stern Stewart & Company and with Mobil Corporation. He received his MBA from the University of Chicago.

Marc Goedhart is a senior expert in McKinsey's Amsterdam office and an endowed professor of corporate valuation at Rotterdam School of Management, Erasmus University (RSM). Over the past 25 years, Marc has served clients across Europe on portfolio restructuring, M&A transactions, and performance management. He received his PhD in finance from Erasmus University.

David Wessels is an adjunct professor of finance at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania. Named by Bloomberg Businessweek as one of America's top business school instructors, he teaches courses on corporate valuation and private equity at the MBA and executive MBA levels. David is also a director in Wharton's executive education group, serving on the executive development faculties of several Fortune 500 companies. A former consultant with McKinsey, he received his PhD from the University of California at Los Angeles.

Business valuation

Trace this topic

Papers published on a yearly basis

Citation Count

2,241 citations

428 citations

309 citations

131 citations

124 citations

Trending Questions (10)

Network information, related topics (5), performance.

Corporate Valuation pp 3–24 Cite as

An Overview of Corporate Valuation

- Benedicto Kulwizira Lukanima 2

- First Online: 05 August 2023

405 Accesses

Part of the book series: Classroom Companion: Business ((CCB))

Valuation is one of the important topics in the business field, and it plays a key role in many areas of finance such as corporate finance, mergers and acquisitions (M&A), and portfolio management. Although the term “valuation” seems to be common, many people may be unaware of its core components. There are different ways in which valuation can be performed—hence, it is not an absolute process. Therefore, different analysts recommend different values for the same company or equity, simply because of different valuation approaches depending on valuation purposes and the suitability of valuation approaches. From this point of view, the definition of value (or valuation) depends on the valuation approach—for example, we have intrinsic value, relative value, market value, and book value.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Buying options

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Durable hardcover edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Bibliography

Brown, G.R. (1998), The idea that valuation is an art, not a science, is hardly mentioned these days, Journal of Property Valuation, and Investment , 16 (1). doi: https://doi.org/10.1108/jpvi.1998.11216aaa.001

DePamphilis, D. M (2019), Mergers and Acquisitions Cash Flow Valuation Basics, In: Mergers, Acquisitions, and Other Restructuring Activities: An Integrated Approach to Process, Tools, Cases, and Solutions 10th ed. , Elsevier Inc., 177 – 205, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/C2017-0-02823-9

Chapter Google Scholar

Fabozzi, F. J., Focardi, F. M., & Jonas, C. (2017), Equity Valuation: Science, Art, or Craft ? Issue 4, CFA Institute.

Google Scholar

Fischoff, S. (2021), Business Valuation Is More Art Than Science, Available vis Financial Poise, https://www.financialpoise.com/art-of-business-valuation/ .Accessed on July 1, 2021.

Mackintosh, J. (2022). Value Investing Is Back. But for How Long? A bounce in bond yields is good news for dividend payers. Available via The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/value-investing-is-back-but-for-how-long-11643726540 . Accessed February 01, 2022.

Nelson, B. (2022). Investing’s First Principles: The Discounted Cash Flow Model. Available via CFA. https://blogs.cfainstitute.org/investor/2022/01/19/investings-first-principles-the-discounted-cash-flow-model/ . Accessed January 19, 2022.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Finance and Accounting, Universidad del Norte, Barranquilla, Colombia

Benedicto Kulwizira Lukanima

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Benedicto Kulwizira Lukanima .

1 Electronic Supplementary Material

Chapter slides—refer to the PowerPoint files for ► Chap. 1 . (PPTX 1548 kb)

Excel illustrations—refer to Excel workings for ► Chap. 1 . (XLSX 17 kb)

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2023 The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Cite this chapter.

Kulwizira Lukanima, B. (2023). An Overview of Corporate Valuation. In: Corporate Valuation. Classroom Companion: Business. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28267-6_1

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-28267-6_1

Published : 05 August 2023

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-031-28266-9

Online ISBN : 978-3-031-28267-6

eBook Packages : Economics and Finance Economics and Finance (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience.

Valuation Topics

Find the databases and market data, books and guides, training events, news and more that are important to your particular valuation topic.

Case Law & Expert Testimony

Compensation

Cost of Capital

Discounts & Premiums

Economic Damages & Lost Profits

Estate & Gift

Fair Value for Financial Reporting

Global Business Valuation

Industry Analysis

Intellectual Property

Market Comparables

Standards of Value

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Int J Environ Res Public Health

Analysis of Academic Literature on Environmental Valuation

Francisco guijarro.

1 Research Institute for Pure and Applied Mathematics, Universitat Politècnica de València, 46022 Valencia, Spain

Prodromos Tsinaslanidis

2 Department of Economics, University of Western Macedonia, 52100 Kastoria, Greece

Environmental valuation refers to a variety of techniques to assign monetary values to environmental impacts, especially non-market impacts. It has experienced a steady growth in the number of publications on the subject in the last 30 years. We performed a search for papers containing the term “environmental valuation” in the title, abstract, or keywords. The search was conducted with an online literature search engine of the Web of Science (WoS) electronic databases. A search of this database revealed that the term “environmental valuation” appeared for the first time in 1987. Since then a large number of studies have been published, including significant breakthroughs in theory and applications. In the present work 661 publications were selected for a review of the literature on environmental valuation over the period 1987–2019. This paper analyzes the evolution of the leading methodologies and authors, highlights the preference for the choice experiment method over the contingent valuation method, and shows that relatively few papers have had a strong impact on the researchers in this area.

1. Introduction

Environmental valuation has traditionally been considered in the context of non-market valuation. Its aim is to obtain a monetary measure of the benefit or cost to the welfare of individuals and social groups of environmental improvement interventions or the consequences of environmental degradation [ 1 , 2 ]. However, the ultimate goal is not to value a (non-market) environmental good in monetary terms, but to provide decision-makers with the necessary tools to take the appropriate political initiatives to efficiently allocate resources, impose taxes and design compensation schemes [ 3 , 4 ], even after assuming the difficulties of developing theoretically grounded practical policy tools and avoiding political manipulation [ 5 ].

Environmental valuation methods have been used to determine the benefits and costs related to the use of environmental goods, improving their conditions or remedying environmental damage and must consider the complexity of the area. For example, the economic benefits of national parks extend beyond tourism; natural amenities and recreation facilities often serve to attract and retain people, entrepreneurs, businesses, and retirees [ 6 ]. On the other hand, some researchers have provided evidence of how worsening environmental conditions can affect the value of other goods. For example, noise and air pollution from road traffic have been reported to negatively impact real estate prices [ 7 , 8 ], and [ 9 ] reported that 55% of those surveyed in Brisbane (Australia) considered that noise adversely affected the value of their property.

Economists have traditionally developed tools to measure environmental values by estimating individuals’ willingness to pay to benefit from environmental goods. The costs associated with environmental deterioration are measured by the loss suffered by the individuals who benefited from the damaged good, and deciding the appropriate compensation for losing the benefit (willingness to accept) [ 10 , 11 ].

The general approach of Total Economic Value (TEV) combines all the different values, which are grouped according to the service provided by the environmental good ( Figure 1 ). The use values are those derived from the actual use of the resource, while the non-use values are not related to its present use. The former includes the direct use value—the value derived from the direct use and exploitation of the environmental good, the ecological value—defined by the benefits that environmental goods provide to support forms of life and biodiversity and the option value—related to future use opportunities of the good. Non-use values are composed of the existence value—the value that individuals give to environmental goods for their mere existence—and the bequest value—the value estimated by individuals when considering the use of goods in the future by their heirs.

The concept of Total Economic Value of environment, taken from [ 12 ].

The aim of environmental valuation methods is to measure the values included in TEV. Although some authors have classified valuation methods from a more general perspective [ 13 ], the methods specifically related to environmental valuation can be classified as follows:

- - Contingent valuation method. Values are estimated in a hypothetical market based on surveys in which respondents are asked how much they are willing to pay for the use and conservation of an environmental good. The purpose of contingent valuation is to estimate individual willingness to pay for changes in the quantity or quality of environmental goods or services [ 3 ].

- - Choice experiment method. This method provides the respondents with alternative choices in which different environmental goods are defined by their attributes. According to [ 14 ], “the most significant advance in environmental valuation may be to move away from a focus on value and focus instead on choice behaviour and data that generate information on choices.”.

- - Travel cost method. Values are estimated by accounting for the cost incurred by people who travel to visit an environmental good. The method assumes that the willingness to pay must be at least as large as the travel cost incurred.

- - Hedonic price method. Values are computed from the prices of traded goods. This approach is frequently used when the price of traded goods is influenced by environmental factors [ 8 ].

The field of environmental valuation has recently expanded both from a theoretical and practical point of view [ 15 ]. This paper aims to outline the advances made by researchers according to their impact on the research area and highlights the key aspects covered by leaders in this field.

To determine the most important topics and assess the academic impact of environmental valuation, we performed a bibliometric analysis considering publications in the Web of Science from 1987 to 2019. We assessed their productivity through their historical evolution and the distribution of papers by journal. The units of analysis were ordered by the citation and co-citation structure and the results gave insights into the organization and future trends on research in environmental valuation.

We performed a search for papers containing the term “environmental valuation” in the title, abstract or keywords. The search was conducted on the online literature search engine of the Web of Science electronic databases. On 17 December 2019 we obtained 661 results from the search engine covering the period 1987–2019, including articles, book chapters, proceedings papers and reviews of 1442 authors. Table 1 shows the protocol followed to perform the data collection and some key figures.

Procedure for the data collection and key figures.

The dataset is analysed in the following section on R [ 16 ], a free software environment for statistical computing and graphics. The bibliometrix [ 17 ] package was used to compile most of the tables in this paper.

3.1. Environmental Evaluation Publication History

The number of publications per year is depicted in Figure 2 . The first known paper on environmental valuation, published in 1987, was followed by a steady increase in number of environmental valuation-related publications over time.

Distribution of Environmental valuation publications by year (1987–2019).

Although the research was published in a wide range of journals, the 4 most popular were: Ecological Economics, Environmental & Resource Economics, Environmental Values, and Journal of Environmental Management– with nearly 30% of the studies ( Table 2 ). Ecological Economics stands out as the most prolific source on this subject with 109 papers, which represents 16.5% of the total sample. Not surprisingly, the top Journals are particularly involved with environmental and ecological issues. The first 6 Journals are grouped into Environmental Sciences or Environmental Studies categories from the Journal Citation Reports of the Web of Science. When taking the impact factor into consideration, the top 6 Journals were ranked into the first quartile of their corresponding categories in 2018, while the rest of Journals are between the first and second quartile in most cases.

Most relevant journals that have published the greatest number of environmental valuation papers.

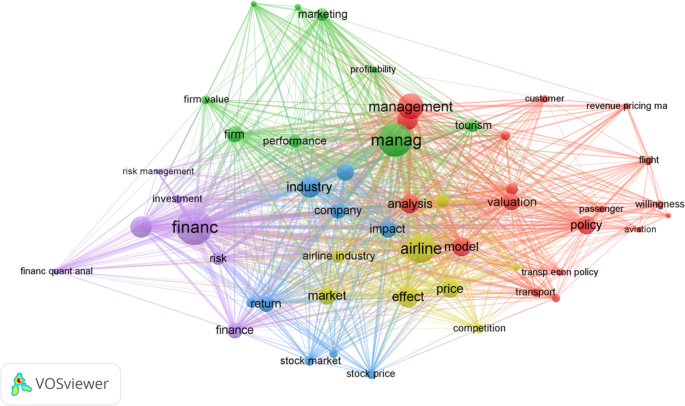

3.2. Leading Topics in Environmental Valuation Research

The most common keywords used by researchers include “environmental evaluation”, “willingness to pay”, and “ecosystem services” ( Table 3 ). The keyword “environmental valuation” was used in 38% of the publications analyzed. The following keywords give useful insights into the evolution of the research topic and the methods developed and applied to value environmental goods and damage. The second most often used keyword is “willingness to pay”, which is commonly found in publications related to stated preference methods. The two abovementioned approaches to this group of environmental valuation methods occupy positions 4 (choice experiment) and 5 (contingent valuation). The choice experiment method also appears in the 7th position as “choice experiments”. The total of both alternatives (78) comes just after the “environmental valuation” keyword.

The 10 most used keywords by number of publications related with environmental valuation.

As the search procedure is automatic, the system differentiates “Choice experiment” from “Choice experiments”. In order to consider all the possible synonyms, we conducted a new experiment by searching for individual terms in the keywords ( Table 3 ). For example, the word “choice” was used to collect all the papers with a keyword related to the choice experiment method. This provided similar expressions to those given in Table 3 : Choice modeling, Choice modelling, Choice model, Choice experiment method, etc. The analysis showed that keywords related to the choice experiment method appeared in 165 papers, while other methods had a lower frequency (contingent valuation method, 69; hedonic price method, 18; travel cost method, 11).

The relevance of choice experiments as a prominent keyword used by researchers has increased over time. We show the evolution of four keyword categories through 3 equally spaced subperiods: 1987–1997, 1998–2008 and 2009–2019 ( Figure 3 ). The first two subperiods were dominated by keywords associated with contingent valuation methods (with labels “contingent valuation” and “contingent valuation method”) and cost-benefit analysis. However, a sudden change was found in the trend during the subperiod 2009–2019. During this time the choice experiments (with labels “choice experiment”, “choice experiments” and “choice experiment model”) dominated the researchers’ interest, closely followed by the willingness to pay keyword.

Evolution of the main keywords used by researchers in environmental valuation.

The popularity of the choice experiment method –over the contingent valuation method—was predicted by Adamowicz [ 14 ]: “The most significant advance in environmental valuation may be to move away from a focus on value and focus instead on choice behaviour and data that generate information on choices.” We can suggest several reasons to support the observed trend. First, the design of both methodologies makes the choice experiment method to extract more information than the contingent valuation method does. Results from contingent valuation are elicited by asking respondents for their willingness to pay (or willingness to accept). In a bidding game, the respondent is asked if he is willing to pay a specific amount of money. If the answer is yes, a higher amount is asked and, if the answer is no, a lower amount is proposed. The questionnaire is repeated until an initial yes changes to a no or vice versa. However, the choice experiment method uses attributes to define alternatives and information of the willingness to pay is obtained by observing the choices made by respondents [ 18 ]. As stated by Hoyos [ 15 ], the choice experiment method allows estimating the mean willingness to pay and also the marginal willingness to pay for the different attributes. Handling with more alternatives and attributes makes the application of the choice experiment more complex. However, its implementation has been facilitated by the development of statistical software. Furthermore, web-based surveys are becoming popular and easy to implement and the number of connected people to the internet keeps increasing, which limits biased sampling, then allowing presenting the choice set in a friendly manner [ 19 ]. An additional benefit from using the choice experiment method is related with the sensitivity to scope. This is one of the main concerns about the contingent valuation method, where the use of labels in the choice experiment may mitigate the lack of sensitivity to the scope [ 19 ].

3.3. The Most Influential Authors in Environmental Valuation

The most prominent authors in an area of research can be identified by citation analysis. Of the top 10 most influential publications on environmental valuation according to the number of citations, Boxall and Adamowicz [ 20 ] leads with 527 citations ( Table 4 ). The authors use a latent class model to evaluate choice behaviour as a function of observable attributes of the choices and latent heterogeneity in the respondents’ characteristics. Although it has the highest number of citations, the paper by Lancsar and Louviere [ 21 ] received more cites on a yearly basis. The choice experiment model dominates the top ranked papers of Table 4 in which the authors introduce different environmental valuation examples to illustrate their proposals. Some of the top ranked papers are devoted either to the demonstration of case studies or to a review of the literature.

The 10 most frequently cited papers on environmental valuation.

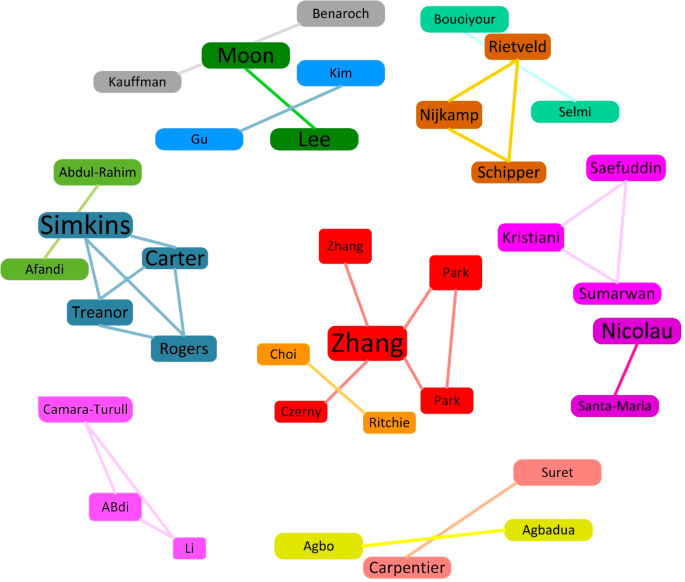

We have analyzed the relevance of different authors in the topic according to the number of publications and the number of citations per year. Figure 4 gives one line to each author, where the extremes represent the year of the first (left circle) and last publication (right circle). Hanley was cited for the longest period, which was 25 years (1995–2019). The diameter of the circles varies in proportion to the number of papers published each year and the colour denotes the number of cites received. For example, the paper by Hanley et al. [ 22 ] has the highest number of citations per year (21.9) in the table. Although this is not the most cited paper according to the bibliographic analysis, it appears in the figure because Hanley is the most prolific researcher.

Relevance of authors according to their production and the number of citations.

The figure distinguishes two groups of authors. The first incorporates those who have been publishing on the topic for roughly 20 years: Hanley, Adamowicz, Boxall, Spash and Brouwer. The other group contains those who published between 2007 and 2019: Meyerhoff, Schaafsma, Hoyos, Mariel and Thorsen.

It should be noted that a few papers are responsible for a high percentage of the citations ( Figure 5 ). gives the number of citations in descending order. Only 7 papers received more than 300 citations for the whole period analyzed, while 55.7% received 10 or fewer. This shows that only a few papers influenced this research topic during this period.

Distribution of citations per paper.

Lastly, there is another interesting point related to the authors’ affiliation country; Figure 6 separates the papers whose authors’ affiliations are all located at the same country (Single Country Publications, SCP) and those with authors’ affiliations from different countries (Multiple Country Publications, MCP). The UK and the USA dominate the research on environmental valuation according to the number of papers published during the analyzed period. There are only 5 European countries in the top 10, while China is the only Asian representative. China is also in the last position in the top 10. Regarding the collaboration between authors from different countries, researchers from the UK and Spain are the most likely to collaborate in multinational publications, while Brazilian and Chinese affiliations produced the fewest publications with contributions from foreign authors.

Most productive countries in environmental valuation.

3.4. Co-Citation Analysis

This subsection begins with some comments about what productivity is in the field of research publication. Of course this is a wide field of debate, but some preliminaries must be established before proceeding with the co-citation analysis. According to [ 29 ], there are several measures to account for productivity. The most basic bibliometric measure is the number of papers published, which provides the raw data for all citation analysis. Another measure is the number of citations, which determines the recognition and influence of a paper. Then we can distinguish between citations received from papers published in Journals indexed in WoS, or citations received for other Journals not considered in WoS. As stated by [ 29 ], a measure of association between highly cited papers is used to form clusters: “That measure is the number of times pairs of papers have been co-cited, that is, the number of later papers that have cited both of them”. Hence, co-citation implies that two papers are cited in a third paper and assumes that both papers are related. We have performed a co-citation analysis by differentiating 3 main clusters in different colours ( Figure 7 ). The references of cluster 1 are represented by the book by Mitchell and Carson [ 30 ], in which the authors describe the contingent valuation method and claim that “the contingent valuation (CV) method offers the most promising approach for determining public willingness to pay for many public goods”. However, the positivist perspective in Mitchell and Carson [ 30 ] is contested by other prominent works in the same group. The report in Arrow et al. [ 31 ] indicate several drawbacks to the contingent valuation method and gives some guidelines to be used if the proposal is to produce useful information for natural resource damage assessment. The research in Kahneman and Knetsch [ 32 ] reports the most serious shortcoming of the CV method. According to these authors: “the assessed value of a public good is demonstrably arbitrary, because willingness to pay for the same good can vary over a wide range depending on whether the good is assessed on its own or embedded as part of a more inclusive package”. There is a more recent relevant book in this group, Bateman et al. [ 33 ], which gives a general approach to stated preferences techniques with application to different non-market goods and services.

Co-citation network analysis.

The cluster 2 (in red) elicited from the co-citation analysis is led by the paper by Boxall et al. [ 26 ], “A comparison of stated preference methods for environmental valuation”. This paper introduces an empirical comparison of the contingent valuation method and choice experiments. Most papers in this group follow the approach in Boxall et al. [ 26 ]. For example, Adamowicz et al. [ 34 ] examine the choice experiment as “an extension or variant of contingent valuation”. The paper in Adamowicz et al. [ 35 ] had earlier compared a stated preference model and a revealed preference model for recreational site choice. The earliest work in the group is the book by Ben-Akiva et al. [ 36 ], which analyzes the discrete choice method from a more general perspective.

And lastly, the cluster 3 covers different references related to choice modelling approaches but with a different approach to the publications in the second group. Again, a single book is the leader in number of cites: Louviere et al. [ 37 ]. Interestingly, this book is not the only reference which gives a survey of choice modelling. The paper by Hoyos [ 15 ] provides a review of the state of the art of environmental valuation with discrete choice experiments; Hanley et al. [ 22 ] examine the choice modelling approach to environmental valuation. The authors state that this methodology “can be considered as an alternative to more familiar valuation techniques based on stated preferences such as the contingent valuation method”; Hanley et al. [ 23 ] also outline choice experiments and analyze its roots in Lancaster’s characteristics theory of value; while the paper by Lancaster [ 38 ] is another relevant work in this group.

4. Discussion

Environmental valuation is intrinsically difficult because realistic environmental valuation situations are rarely observed, and singularities in environmental assets impede a uniform treatment of those values outlined by the Total Economic Value. Notwithstanding the difficulties, a plethora of papers have been published during the last decades.

As a result of this research it can be concluded that revealed preferences methodologies are surpassed by works focused on stated preference methods for the analyzed period as a whole. The research discloses the relevance of stated preference methods over revealed preferences methods, with a clear dominance of choice experiment over any other environmental valuation method, as predicted by Adamowicz [ 14 ]. The complexity of the choice experiment method has resulted in new challenges and research lines for academics. Choosing and implementing experimental designs, interpreting standard and more advanced random utility models, and estimating measures of willingness-to-pay are some of the issues covered by researchers [ 39 ].

Differences on the environmental valuation have been also revealed by the co-citation analysis, which reports different clusters by considering the methods used in the environmental valuation process. Despite its past influence, none of the travel cost and hedonic price methods is in the 10 most popular methods of environmental valuation, according to the keywords in the dataset used. In addition, the leading Journals in the publication of environmental valuation papers are ranked in prominent positions by WoS in their corresponding categories. The paper also distinguish two groups of authors according to the time they have published on the topic. The first group initiates the growth of the area in the mid-1990s, while the second group concentrates its impact mainly from 2010.

The abovementioned differences in the use of the environmental valuation methods do not imply that one method is unequivocally better or worse than another since its appropriateness depends on a particular situation. In other words, no single method is suitable in all valuation scenarios. Rather, the choice of the valuation method is context-specific. Revealed preference methods can be prioritized when budget and time are constrained. Stated preference methods require a complex questionnaire development and data analysis, which translates into an additional need of resources (both money and time). Conversely, revealed preference methods can only capture use values, while stated preference methods can estimate both use and non-use values. In addition, using multiple methodologies can be appropriate in some situations. For example, the combination of revealed and stated preference methods can improve benefit estimation of a single component [ 35 ]. This approach can be useful when a revealed preference method is utilized as the main valuation instrument, but some environmental values are more accurately estimated by using another method and the result is aggregated. In this case, the researcher must be careful to avoid double counting if the components of value captured by the different methods overlap [ 40 ].

5. Conclusions

From the evolution of environmental valuation publications in the last 30 years, we can assert that the discipline has been consolidated. Papers related to choice experiments have dominated academic production in the last decade. In the current stage of environmental valuation researchers will have to cope with new challenges and emerging trends. As in other research areas, the increasing ability to collect enormous amounts of data facilitates the creation of the available massive databases, which can be used to take environmental valuation methodologies to the next stage in their evolution by incorporating machine learning techniques in the valuation process. However, this evolution should not be restricted to new applications of the well-known valuation methods only. Researchers must develop new approaches to deal with new elements in the valuation process. We expect that climate change, as one of the defining challenges of the 21st century, will attract most attention from researchers to propose new approaches in environmental valuation [ 41 , 42 ]. As knowledge and perception are subjective, the intangible aspects must be explicitly considered in the new valuation methods [ 13 ]. In this regard, we may conclude that the future path of environmental valuation is not necessarily related to new methodologies, but to the inheritance and assimilation of consolidated techniques commonly used in other scientific areas.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank three anonymous referees for their constructive comments and suggestions that substantially improved this article.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, F.G. and P.T.; methodology, F.G. and P.T.; software, F.G.; validation, P.T.; formal analysis, F.G.; investigation, F.G. and P.T.; resources, P.T.; data curation, F.G.; writing—original draft preparation, F.G.; writing–review and editing, P.T.; visualization, F.G. and P.T.; supervision, P.T. All authors have read and agree to the published version of the manuscript.

This research received no external funding.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

- Search Menu

- Browse content in A - General Economics and Teaching

- Browse content in A1 - General Economics

- A11 - Role of Economics; Role of Economists; Market for Economists

- A13 - Relation of Economics to Social Values

- A14 - Sociology of Economics

- Browse content in C - Mathematical and Quantitative Methods

- Browse content in C0 - General

- C02 - Mathematical Methods

- Browse content in C1 - Econometric and Statistical Methods and Methodology: General

- C10 - General

- C11 - Bayesian Analysis: General

- C12 - Hypothesis Testing: General

- C13 - Estimation: General

- C14 - Semiparametric and Nonparametric Methods: General

- C15 - Statistical Simulation Methods: General

- C18 - Methodological Issues: General

- Browse content in C2 - Single Equation Models; Single Variables

- C21 - Cross-Sectional Models; Spatial Models; Treatment Effect Models; Quantile Regressions

- C22 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes

- C23 - Panel Data Models; Spatio-temporal Models

- Browse content in C3 - Multiple or Simultaneous Equation Models; Multiple Variables

- C32 - Time-Series Models; Dynamic Quantile Regressions; Dynamic Treatment Effect Models; Diffusion Processes; State Space Models

- C38 - Classification Methods; Cluster Analysis; Principal Components; Factor Models

- Browse content in C4 - Econometric and Statistical Methods: Special Topics

- C45 - Neural Networks and Related Topics

- Browse content in C5 - Econometric Modeling

- C50 - General

- C51 - Model Construction and Estimation

- C52 - Model Evaluation, Validation, and Selection

- C53 - Forecasting and Prediction Methods; Simulation Methods

- C55 - Large Data Sets: Modeling and Analysis

- C58 - Financial Econometrics

- Browse content in C6 - Mathematical Methods; Programming Models; Mathematical and Simulation Modeling

- C61 - Optimization Techniques; Programming Models; Dynamic Analysis

- C62 - Existence and Stability Conditions of Equilibrium

- C65 - Miscellaneous Mathematical Tools

- Browse content in C7 - Game Theory and Bargaining Theory

- C70 - General

- C72 - Noncooperative Games

- C73 - Stochastic and Dynamic Games; Evolutionary Games; Repeated Games

- C78 - Bargaining Theory; Matching Theory

- Browse content in C8 - Data Collection and Data Estimation Methodology; Computer Programs

- C81 - Methodology for Collecting, Estimating, and Organizing Microeconomic Data; Data Access

- Browse content in C9 - Design of Experiments

- C91 - Laboratory, Individual Behavior

- C92 - Laboratory, Group Behavior

- C93 - Field Experiments

- Browse content in D - Microeconomics

- Browse content in D0 - General

- D03 - Behavioral Microeconomics: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in D1 - Household Behavior and Family Economics

- D10 - General

- D11 - Consumer Economics: Theory

- D12 - Consumer Economics: Empirical Analysis

- D14 - Household Saving; Personal Finance

- D15 - Intertemporal Household Choice: Life Cycle Models and Saving

- D18 - Consumer Protection

- Browse content in D2 - Production and Organizations

- D20 - General

- D21 - Firm Behavior: Theory

- D22 - Firm Behavior: Empirical Analysis

- D23 - Organizational Behavior; Transaction Costs; Property Rights

- D24 - Production; Cost; Capital; Capital, Total Factor, and Multifactor Productivity; Capacity

- D25 - Intertemporal Firm Choice: Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in D3 - Distribution

- D30 - General

- D31 - Personal Income, Wealth, and Their Distributions

- Browse content in D4 - Market Structure, Pricing, and Design

- D40 - General

- D43 - Oligopoly and Other Forms of Market Imperfection

- D44 - Auctions

- D47 - Market Design

- D49 - Other

- Browse content in D5 - General Equilibrium and Disequilibrium

- D50 - General

- D51 - Exchange and Production Economies

- D52 - Incomplete Markets

- D53 - Financial Markets

- Browse content in D6 - Welfare Economics

- D60 - General

- D61 - Allocative Efficiency; Cost-Benefit Analysis

- D62 - Externalities

- Browse content in D7 - Analysis of Collective Decision-Making

- D70 - General

- D71 - Social Choice; Clubs; Committees; Associations

- D72 - Political Processes: Rent-seeking, Lobbying, Elections, Legislatures, and Voting Behavior

- D73 - Bureaucracy; Administrative Processes in Public Organizations; Corruption

- D74 - Conflict; Conflict Resolution; Alliances; Revolutions

- D78 - Positive Analysis of Policy Formulation and Implementation

- Browse content in D8 - Information, Knowledge, and Uncertainty

- D80 - General

- D81 - Criteria for Decision-Making under Risk and Uncertainty

- D82 - Asymmetric and Private Information; Mechanism Design

- D83 - Search; Learning; Information and Knowledge; Communication; Belief; Unawareness

- D84 - Expectations; Speculations

- D85 - Network Formation and Analysis: Theory

- D86 - Economics of Contract: Theory

- D87 - Neuroeconomics

- Browse content in D9 - Micro-Based Behavioral Economics

- D90 - General

- D91 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making

- D92 - Intertemporal Firm Choice, Investment, Capacity, and Financing

- Browse content in E - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics

- Browse content in E0 - General

- E00 - General

- E03 - Behavioral Macroeconomics

- Browse content in E1 - General Aggregative Models

- E17 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E2 - Consumption, Saving, Production, Investment, Labor Markets, and Informal Economy

- E20 - General

- E21 - Consumption; Saving; Wealth

- E22 - Investment; Capital; Intangible Capital; Capacity

- E23 - Production

- E24 - Employment; Unemployment; Wages; Intergenerational Income Distribution; Aggregate Human Capital; Aggregate Labor Productivity

- Browse content in E3 - Prices, Business Fluctuations, and Cycles

- E30 - General

- E31 - Price Level; Inflation; Deflation

- E32 - Business Fluctuations; Cycles

- E37 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E4 - Money and Interest Rates

- E40 - General

- E41 - Demand for Money

- E42 - Monetary Systems; Standards; Regimes; Government and the Monetary System; Payment Systems

- E43 - Interest Rates: Determination, Term Structure, and Effects

- E44 - Financial Markets and the Macroeconomy

- E47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in E5 - Monetary Policy, Central Banking, and the Supply of Money and Credit

- E50 - General

- E51 - Money Supply; Credit; Money Multipliers

- E52 - Monetary Policy

- E58 - Central Banks and Their Policies

- Browse content in E6 - Macroeconomic Policy, Macroeconomic Aspects of Public Finance, and General Outlook

- E60 - General

- E61 - Policy Objectives; Policy Designs and Consistency; Policy Coordination

- E62 - Fiscal Policy

- E63 - Comparative or Joint Analysis of Fiscal and Monetary Policy; Stabilization; Treasury Policy

- E64 - Incomes Policy; Price Policy

- E65 - Studies of Particular Policy Episodes

- E66 - General Outlook and Conditions

- Browse content in E7 - Macro-Based Behavioral Economics

- E71 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on the Macro Economy

- Browse content in F - International Economics

- Browse content in F0 - General

- F02 - International Economic Order and Integration

- Browse content in F1 - Trade

- F14 - Empirical Studies of Trade

- Browse content in F2 - International Factor Movements and International Business

- F21 - International Investment; Long-Term Capital Movements

- F22 - International Migration

- F23 - Multinational Firms; International Business

- Browse content in F3 - International Finance

- F30 - General

- F31 - Foreign Exchange

- F32 - Current Account Adjustment; Short-Term Capital Movements

- F33 - International Monetary Arrangements and Institutions

- F34 - International Lending and Debt Problems

- F36 - Financial Aspects of Economic Integration

- F37 - International Finance Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- F38 - International Financial Policy: Financial Transactions Tax; Capital Controls

- Browse content in F4 - Macroeconomic Aspects of International Trade and Finance

- F40 - General

- F41 - Open Economy Macroeconomics

- F42 - International Policy Coordination and Transmission

- F43 - Economic Growth of Open Economies

- F44 - International Business Cycles

- F47 - Forecasting and Simulation: Models and Applications

- Browse content in F5 - International Relations, National Security, and International Political Economy

- F51 - International Conflicts; Negotiations; Sanctions

- Browse content in F6 - Economic Impacts of Globalization

- F63 - Economic Development

- F65 - Finance

- Browse content in G - Financial Economics

- Browse content in G0 - General

- G00 - General

- G01 - Financial Crises

- G02 - Behavioral Finance: Underlying Principles

- Browse content in G1 - General Financial Markets

- G10 - General

- G11 - Portfolio Choice; Investment Decisions

- G12 - Asset Pricing; Trading volume; Bond Interest Rates

- G13 - Contingent Pricing; Futures Pricing

- G14 - Information and Market Efficiency; Event Studies; Insider Trading

- G15 - International Financial Markets

- G17 - Financial Forecasting and Simulation

- G18 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G19 - Other

- Browse content in G2 - Financial Institutions and Services

- G20 - General

- G21 - Banks; Depository Institutions; Micro Finance Institutions; Mortgages

- G22 - Insurance; Insurance Companies; Actuarial Studies

- G23 - Non-bank Financial Institutions; Financial Instruments; Institutional Investors

- G24 - Investment Banking; Venture Capital; Brokerage; Ratings and Ratings Agencies

- G28 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G29 - Other

- Browse content in G3 - Corporate Finance and Governance

- G30 - General

- G31 - Capital Budgeting; Fixed Investment and Inventory Studies; Capacity

- G32 - Financing Policy; Financial Risk and Risk Management; Capital and Ownership Structure; Value of Firms; Goodwill

- G33 - Bankruptcy; Liquidation

- G34 - Mergers; Acquisitions; Restructuring; Corporate Governance

- G35 - Payout Policy

- G38 - Government Policy and Regulation

- G39 - Other

- Browse content in G4 - Behavioral Finance

- G40 - General

- G41 - Role and Effects of Psychological, Emotional, Social, and Cognitive Factors on Decision Making in Financial Markets

- Browse content in G5 - Household Finance

- G50 - General

- G51 - Household Saving, Borrowing, Debt, and Wealth

- G52 - Insurance

- G53 - Financial Literacy

- Browse content in H - Public Economics

- H0 - General

- Browse content in H1 - Structure and Scope of Government

- H11 - Structure, Scope, and Performance of Government

- H19 - Other

- Browse content in H2 - Taxation, Subsidies, and Revenue

- H22 - Incidence

- H24 - Personal Income and Other Nonbusiness Taxes and Subsidies; includes inheritance and gift taxes

- H25 - Business Taxes and Subsidies

- H26 - Tax Evasion and Avoidance

- Browse content in H3 - Fiscal Policies and Behavior of Economic Agents

- H31 - Household

- Browse content in H4 - Publicly Provided Goods

- H40 - General

- H41 - Public Goods

- Browse content in H5 - National Government Expenditures and Related Policies

- H50 - General

- H52 - Government Expenditures and Education

- H53 - Government Expenditures and Welfare Programs

- H54 - Infrastructures; Other Public Investment and Capital Stock

- H55 - Social Security and Public Pensions

- H56 - National Security and War

- H57 - Procurement

- Browse content in H6 - National Budget, Deficit, and Debt

- H63 - Debt; Debt Management; Sovereign Debt

- Browse content in H7 - State and Local Government; Intergovernmental Relations

- H70 - General

- H72 - State and Local Budget and Expenditures

- H74 - State and Local Borrowing

- H75 - State and Local Government: Health; Education; Welfare; Public Pensions

- Browse content in H8 - Miscellaneous Issues

- H81 - Governmental Loans; Loan Guarantees; Credits; Grants; Bailouts

- Browse content in I - Health, Education, and Welfare

- Browse content in I1 - Health

- I11 - Analysis of Health Care Markets

- I12 - Health Behavior

- I13 - Health Insurance, Public and Private

- I18 - Government Policy; Regulation; Public Health

- Browse content in I2 - Education and Research Institutions

- I22 - Educational Finance; Financial Aid

- I23 - Higher Education; Research Institutions

- I28 - Government Policy

- Browse content in I3 - Welfare, Well-Being, and Poverty

- I30 - General

- I38 - Government Policy; Provision and Effects of Welfare Programs

- Browse content in J - Labor and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in J0 - General

- J00 - General

- Browse content in J1 - Demographic Economics

- J11 - Demographic Trends, Macroeconomic Effects, and Forecasts

- J12 - Marriage; Marital Dissolution; Family Structure; Domestic Abuse

- J13 - Fertility; Family Planning; Child Care; Children; Youth

- J15 - Economics of Minorities, Races, Indigenous Peoples, and Immigrants; Non-labor Discrimination

- J16 - Economics of Gender; Non-labor Discrimination

- J18 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J2 - Demand and Supply of Labor

- J20 - General

- J21 - Labor Force and Employment, Size, and Structure

- J22 - Time Allocation and Labor Supply

- J23 - Labor Demand

- J24 - Human Capital; Skills; Occupational Choice; Labor Productivity

- J26 - Retirement; Retirement Policies

- J28 - Safety; Job Satisfaction; Related Public Policy

- Browse content in J3 - Wages, Compensation, and Labor Costs

- J30 - General

- J31 - Wage Level and Structure; Wage Differentials

- J32 - Nonwage Labor Costs and Benefits; Retirement Plans; Private Pensions

- J33 - Compensation Packages; Payment Methods

- J38 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J4 - Particular Labor Markets

- J41 - Labor Contracts

- J44 - Professional Labor Markets; Occupational Licensing

- J45 - Public Sector Labor Markets

- J46 - Informal Labor Markets

- J49 - Other

- Browse content in J5 - Labor-Management Relations, Trade Unions, and Collective Bargaining

- J51 - Trade Unions: Objectives, Structure, and Effects

- J52 - Dispute Resolution: Strikes, Arbitration, and Mediation; Collective Bargaining

- Browse content in J6 - Mobility, Unemployment, Vacancies, and Immigrant Workers

- J61 - Geographic Labor Mobility; Immigrant Workers

- J62 - Job, Occupational, and Intergenerational Mobility

- J63 - Turnover; Vacancies; Layoffs

- J64 - Unemployment: Models, Duration, Incidence, and Job Search

- J65 - Unemployment Insurance; Severance Pay; Plant Closings

- J68 - Public Policy

- Browse content in J7 - Labor Discrimination

- J71 - Discrimination

- Browse content in J8 - Labor Standards: National and International

- J88 - Public Policy

- Browse content in K - Law and Economics

- Browse content in K1 - Basic Areas of Law

- K12 - Contract Law

- Browse content in K2 - Regulation and Business Law

- K22 - Business and Securities Law

- K23 - Regulated Industries and Administrative Law

- Browse content in K3 - Other Substantive Areas of Law

- K31 - Labor Law

- K32 - Environmental, Health, and Safety Law

- K34 - Tax Law

- K35 - Personal Bankruptcy Law

- Browse content in K4 - Legal Procedure, the Legal System, and Illegal Behavior

- K42 - Illegal Behavior and the Enforcement of Law

- Browse content in L - Industrial Organization

- Browse content in L1 - Market Structure, Firm Strategy, and Market Performance

- L10 - General

- L11 - Production, Pricing, and Market Structure; Size Distribution of Firms

- L13 - Oligopoly and Other Imperfect Markets

- L14 - Transactional Relationships; Contracts and Reputation; Networks

- L15 - Information and Product Quality; Standardization and Compatibility

- Browse content in L2 - Firm Objectives, Organization, and Behavior

- L21 - Business Objectives of the Firm

- L22 - Firm Organization and Market Structure

- L23 - Organization of Production

- L24 - Contracting Out; Joint Ventures; Technology Licensing

- L25 - Firm Performance: Size, Diversification, and Scope

- L26 - Entrepreneurship

- L29 - Other

- Browse content in L3 - Nonprofit Organizations and Public Enterprise

- L33 - Comparison of Public and Private Enterprises and Nonprofit Institutions; Privatization; Contracting Out

- Browse content in L4 - Antitrust Issues and Policies

- L43 - Legal Monopolies and Regulation or Deregulation

- L44 - Antitrust Policy and Public Enterprises, Nonprofit Institutions, and Professional Organizations

- Browse content in L5 - Regulation and Industrial Policy

- L51 - Economics of Regulation

- Browse content in L6 - Industry Studies: Manufacturing

- L66 - Food; Beverages; Cosmetics; Tobacco; Wine and Spirits

- Browse content in L8 - Industry Studies: Services

- L81 - Retail and Wholesale Trade; e-Commerce

- L85 - Real Estate Services

- L86 - Information and Internet Services; Computer Software

- Browse content in L9 - Industry Studies: Transportation and Utilities

- L92 - Railroads and Other Surface Transportation

- L94 - Electric Utilities

- Browse content in M - Business Administration and Business Economics; Marketing; Accounting; Personnel Economics

- Browse content in M0 - General

- M00 - General

- Browse content in M1 - Business Administration

- M12 - Personnel Management; Executives; Executive Compensation

- M13 - New Firms; Startups

- M14 - Corporate Culture; Social Responsibility

- M16 - International Business Administration

- Browse content in M2 - Business Economics

- M20 - General

- M21 - Business Economics

- Browse content in M3 - Marketing and Advertising

- M30 - General

- M31 - Marketing

- M37 - Advertising

- Browse content in M4 - Accounting and Auditing

- M40 - General

- M41 - Accounting

- M42 - Auditing

- M48 - Government Policy and Regulation

- Browse content in M5 - Personnel Economics

- M51 - Firm Employment Decisions; Promotions

- M52 - Compensation and Compensation Methods and Their Effects

- M54 - Labor Management

- Browse content in N - Economic History

- Browse content in N1 - Macroeconomics and Monetary Economics; Industrial Structure; Growth; Fluctuations

- N10 - General, International, or Comparative

- N12 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- Browse content in N2 - Financial Markets and Institutions

- N20 - General, International, or Comparative

- N21 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- N22 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- N23 - Europe: Pre-1913

- N24 - Europe: 1913-

- N25 - Asia including Middle East

- N27 - Africa; Oceania

- Browse content in N3 - Labor and Consumers, Demography, Education, Health, Welfare, Income, Wealth, Religion, and Philanthropy

- N32 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- Browse content in N4 - Government, War, Law, International Relations, and Regulation

- N43 - Europe: Pre-1913

- Browse content in N7 - Transport, Trade, Energy, Technology, and Other Services

- N71 - U.S.; Canada: Pre-1913

- Browse content in N8 - Micro-Business History

- N80 - General, International, or Comparative

- N82 - U.S.; Canada: 1913-

- Browse content in O - Economic Development, Innovation, Technological Change, and Growth

- Browse content in O1 - Economic Development

- O11 - Macroeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O12 - Microeconomic Analyses of Economic Development

- O13 - Agriculture; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Other Primary Products

- O16 - Financial Markets; Saving and Capital Investment; Corporate Finance and Governance

- O17 - Formal and Informal Sectors; Shadow Economy; Institutional Arrangements

- Browse content in O2 - Development Planning and Policy

- O23 - Fiscal and Monetary Policy in Development

- Browse content in O3 - Innovation; Research and Development; Technological Change; Intellectual Property Rights

- O30 - General

- O31 - Innovation and Invention: Processes and Incentives

- O32 - Management of Technological Innovation and R&D

- O33 - Technological Change: Choices and Consequences; Diffusion Processes

- O34 - Intellectual Property and Intellectual Capital

- O35 - Social Innovation

- O38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in O4 - Economic Growth and Aggregate Productivity

- O40 - General

- O43 - Institutions and Growth

- Browse content in O5 - Economywide Country Studies

- O53 - Asia including Middle East

- Browse content in P - Economic Systems

- Browse content in P1 - Capitalist Systems

- P16 - Political Economy

- P18 - Energy: Environment

- Browse content in P2 - Socialist Systems and Transitional Economies

- P26 - Political Economy; Property Rights

- Browse content in P3 - Socialist Institutions and Their Transitions

- P31 - Socialist Enterprises and Their Transitions

- P34 - Financial Economics

- P39 - Other

- Browse content in P4 - Other Economic Systems

- P43 - Public Economics; Financial Economics

- P48 - Political Economy; Legal Institutions; Property Rights; Natural Resources; Energy; Environment; Regional Studies

- Browse content in Q - Agricultural and Natural Resource Economics; Environmental and Ecological Economics

- Browse content in Q0 - General

- Q02 - Commodity Markets

- Browse content in Q3 - Nonrenewable Resources and Conservation

- Q31 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q32 - Exhaustible Resources and Economic Development

- Browse content in Q4 - Energy

- Q40 - General

- Q41 - Demand and Supply; Prices

- Q42 - Alternative Energy Sources

- Q43 - Energy and the Macroeconomy

- Browse content in Q5 - Environmental Economics

- Q50 - General

- Q51 - Valuation of Environmental Effects

- Q53 - Air Pollution; Water Pollution; Noise; Hazardous Waste; Solid Waste; Recycling

- Q54 - Climate; Natural Disasters; Global Warming

- Q56 - Environment and Development; Environment and Trade; Sustainability; Environmental Accounts and Accounting; Environmental Equity; Population Growth

- Browse content in R - Urban, Rural, Regional, Real Estate, and Transportation Economics

- Browse content in R0 - General

- R00 - General

- Browse content in R1 - General Regional Economics

- R10 - General

- R11 - Regional Economic Activity: Growth, Development, Environmental Issues, and Changes

- R12 - Size and Spatial Distributions of Regional Economic Activity

- Browse content in R2 - Household Analysis

- R20 - General

- R21 - Housing Demand

- R23 - Regional Migration; Regional Labor Markets; Population; Neighborhood Characteristics

- Browse content in R3 - Real Estate Markets, Spatial Production Analysis, and Firm Location

- R30 - General

- R31 - Housing Supply and Markets

- R32 - Other Spatial Production and Pricing Analysis

- R33 - Nonagricultural and Nonresidential Real Estate Markets

- R38 - Government Policy

- Browse content in R4 - Transportation Economics

- R41 - Transportation: Demand, Supply, and Congestion; Travel Time; Safety and Accidents; Transportation Noise

- Browse content in R5 - Regional Government Analysis

- R51 - Finance in Urban and Rural Economies

- Browse content in Z - Other Special Topics

- Browse content in Z1 - Cultural Economics; Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology

- Z11 - Economics of the Arts and Literature

- Z13 - Economic Sociology; Economic Anthropology; Social and Economic Stratification

- Advance articles

- Editor's Choice

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access

- About The Review of Financial Studies

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Terms and Conditions

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Article Contents

1. empirically grounded models of subjective beliefs, 2. expectation formation in asset pricing, 3. macro and monetary economics connections, 4. macro and monetary drivers of asset prices, 5. intermediary asset pricing and beyond, 6. intermediary asset pricing: assessment and future directions, 7. international finance, 8. an asset pricing view of exchange rates, acknowledgement.

- < Previous

Review Article: Perspectives on the Future of Asset Pricing

- Article contents

- Figures & tables

- Supplementary Data

Markus Brunnermeier, Emmanuel Farhi, Ralph S J Koijen, Arvind Krishnamurthy, Sydney C Ludvigson, Hanno Lustig, Stefan Nagel, Monika Piazzesi, Review Article: Perspectives on the Future of Asset Pricing, The Review of Financial Studies , Volume 34, Issue 4, April 2021, Pages 2126–2160, https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhaa129

- Permissions Icon Permissions

The field of asset pricing is a rich and diverse discipline that has contributed to many areas of discourse, including those of fundamental importance to policy makers, investors, and households. 1 As we look ahead during a time of substantial economic and political change, it is apparent that society faces many pressing questions, both new and old, that the field is uniquely suited to informing.

To contribute to this conversation, the NBER Asset Pricing program convened a panel discussion on “Perspectives on the Future of Asset Pricing” at its November 8, 2019, meeting that took place at Stanford University. The objective of the panel was to identify some of the important questions the field could productively address in the next five to 10 years. The panelists, consisting of experts in several subfields of asset pricing, were invited to share their views on these questions with an eye toward innovative research topics that are ripe for exploring, and the metrics the field could be using to gauge progress.

This article summarizes these views. The list of topics covered by the panelists is by no means exhaustive. We hope that this article shall nevertheless serve as a productive conduit for identifying some key questions for investigation and generating a concerted research effort toward answering them.

Beliefs are central to asset pricing. 2 Asset prices are forward-looking, and essentially any asset-pricing model implies that investors price assets based on their beliefs about the joint distribution of some stochastic discount factor (SDF) |$M_{t+1}$| and payoffs |$X_{t+1}$| . An observer outside the field of asset pricing might therefore guess that a major part of the research efforts in asset pricing are devoted to understanding how investors form beliefs. This is, at least so far, not the case.

The vast majority of theoretical and empirical work in asset pricing is based on the rational expectations (RE) paradigm. Under RE, as in Lucas (1978) , investors are assumed to know the economy’s underlying model and the model parameters, and to forecast rationally.

Within the RE paradigm, there is no role for the study of beliefs: theoretically, beliefs are implied by the model; empirically, an econometrician can recover investor beliefs from the large-sample empirical distribution of |$M_{t+1}$| and |$X_{t+1}$| .

RE-based approaches have been useful to establish a benchmark, but asset prices have not yielded easily to RE-based explanations. Seeing the increasingly complicated dynamics in preferences and endowment processes researchers use to reverse-engineer better-fitting RE models, it is natural to wonder whether more progress could be made by treating belief dynamics as an object of theoretical and empirical study.

I propose that such a research program should be organized around the following three principles:

Research focus should be on motivating, building, calibrating, and estimating models with non-RE beliefs rather than on merely rejecting RE models. To make further progress, we need structural models of belief dynamics that can compete with RE models in explaining asset prices and empirically observed beliefs.

Deviating from RE does not necessarily imply assuming irrationality. For example, models of Bayesian learning relax the RE assumption that agents know the model of the world and its parameter values, while retaining the rational forecasting assumption. Exploration of cognitive limitations, bounded rationality, and heuristics that relax the rational forecasting assumption may have promising insights to offer as well, but even models of rational learning can produce asset-price properties that are quite different from those in an RE setting. 3

Belief dynamics should be disciplined with data on beliefs and micro decisions. While reverse-engineering of preferences and technology to fit asset prices is common in the literature, I would argue that we should not follow this approach with beliefs. Taking beliefs seriously as an object of scientific study also means bringing in empirical data that helps pin down their dynamics.

In line with these principles, a number of areas seem promising for future research:

1.1 Belief measurement

The availability of beliefs data has improved substantially in recent years, but for beliefs data to become a standard ingredient of asset-pricing research, further progress on measurement is necessary.

So far we do not have a good understanding of investor expectations of firm cash flows. Existing work on expectations in asset pricing has often focused on return expectations, but return expectations alone, especially ones limited to relatively short forecast horizons, do not provide a complete picture of how beliefs dynamics explain variation in price levels. Forecasts of earnings and dividends by analysts, used in De la O and Myers (2019) , and by CFOs in the Graham and Harvey (2011) survey are a start, but there is more to be done.

Collecting more data on long-run expectations would be useful. Much of the currently available expectations data is focused on short forecast horizons such as one year. Asset prices, however, depend on expectations over much longer horizons.

In addition to perceived first moments, investors’ subjective perception of risk are also of obvious relevance to asset pricing. 4 Data on beliefs about the perceived downside tails of the distribution would be particularly interesting. Since crashes and disasters are infrequent, objective historical data does little to pin down these tails, leaving lots of room for subjective judgements. Eliciting beliefs about the shape of distributions is a challenging problem, but further research on belief elicitation methods may bring progress in this area, too ( Manski, 2018 ).

Finally, in many asset-pricing applications, we are interested in dynamics of beliefs at frequencies of the business cycle, or even lower. This means that we need long time series. The time series available in survey data have lengthened substantially, but there are still potential benefits from innovations that can help to extend beliefs data backwards in time, for example, with proxies constructed from textual analysis of media, somewhat akin to what Manela and Moreira (2017) have done to extend the VIX index.

1.2 Beliefs and actions

If a respondent in a survey states a belief, this does not necessarily mean that the respondent is ready to act in accordance with this stated belief. In addition to a decision-relevant signal, stated beliefs likely contain measurement noise. For example, it is unlikely that respondents deliberate as carefully when stating beliefs as they would if they actually had to take an action. Moreover, even if stated beliefs truly reflect respondents’ perceptions, actual or cognitive costs of taking an action may prevent respondents from perfectly aligning their choices with these beliefs. To sort out these issues, more research on the connection of beliefs and actions is needed. 5

For asset pricing, we also need to understand the properties of this measurement error when we aggregate across respondents. If measurement error averages out within the population, or within demographic groups, then matching asset-pricing models with beliefs moments based on such aggregates may be fine, even if the links between stated beliefs and actions are distorted by measurement error at the individual level. To the extent that more sophisticated agents play a bigger role in financial markets, how the belief-action relationship varies with sophistication is an important issue as well. 6

Another important question to sort out is whose beliefs matter for pricing. Individual investors’ beliefs can differ from those of professional investors. The relative importance of their beliefs in influencing asset prices likely differs by aggregation level: For allocation decisions at the asset class level (e.g. stocks vs. bonds), it seems likely that individuals exert substantial influence because the investment products they choose from often have predetermined allocations to an asset class; at the individual stock level, fund managers have discretion; at the investment-style level (e.g., small vs. large stocks) there is probably a mix of predetermined choices by individuals and managerial discretion. Sorting this out empirically would also help in linking belief-based approaches with a demand-system analysis as in Koijen and Yogo (2019) .

1.3 Modeling belief formation

Models of investor belief dynamics need to take a stand on the sources of information that investors rely on when they form their beliefs and how they digest this information to produce forecasts. Two questions in this regard seem particularly interesting.

How do investors form beliefs when faced with high-dimensional prediction problems? Existing asset-pricing models with parameter learning typically consider settings with a small number of predictor variables. Reality, however, looks different. For example, to value stocks, investors must forecast cash flows. They observe a vast number of potential predictor variables, but they do not know the precise functional relationship between predictors and future cash flows and need to learn it from observed data. In a simple linear setting with homogeneous investors, Martin and Nagel (2019) show that this can give rise to return predictability and a “factor zoo.” Further efforts to close the gap between the simplistic environments investors face in asset-pricing models and the messy real world seem necessary.

The second question concerns the role of memory. Data can shape beliefs only if it is remembered. In theory, one could imagine a Bayesian learner that takes into account “all available” history when learning about pricing-relevant stochastic processes. But when mapping these models into the real world, it is not clear what “all available” means. Some implementations of learning models set time zero to 1926, because this is where the CRSP database starts, but this is obviously not the true starting point of investors’ learning process. Moreover, there are reasons to expect that memory could be limited. More research, both empirically and theoretically, is needed to better understand investors’ formation of memory, including those of institutions (e.g., through maintenance of data sets or establishment of decision rules). 7

1.4 Beyond asset pricing: Macro-finance

The drivers of stock price dynamics emphasized in asset pricing research are largely disconnected from the drivers of the business cycle that macroeconomists focus on (see, e.g., Cochrane 2017 ). This question should be revisited through the lens of models with non-RE belief dynamics. Shocks to beliefs are potential source of links between asset prices and macro quantities. Exactly how such links could play out is an open question. 8

Beliefs effects could operate in ways that are quite different from time-varying preferences that macro and asset-pricing research has already explored in various ways. For example, belief effects can be specific to technologies or markets. An individual could be optimistic about the housing market but, at the same time, pessimistic about the stock market. Beliefs data will be important to sort out the commonalities and differences between different sectors and markets.

Interactions of beliefs with frictions are potentially interesting. For example, belief heterogeneity can interact with frictions in a way that amplifies shocks ( Caballero and Simsek (2020) ). The housing market seems to be a particularly interesting area to explore these types of mechanisms, as it features substantial frictions and plays a big role in the macroeconomy.

1.5 Conclusion

Asset prices express investors’ beliefs about the future. Our understanding of how investors form these beliefs, how they evolve over time, and how we can measure them is still limited. Empirically grounded research on investor beliefs holds promise to unlock some of the mysteries of asset pricing.

The conventional agenda in the asset pricing literature studies quantitative rational expectation models. 9 This approach is particularly well suited for the study of recurring patterns, such as the comovement of price-dividend ratios on stocks with the business cycle or the seasonality in the housing market during a calendar year. (Volume and prices are above trend during the summer, while activity in housing markets slows down in the winter.) In rational expectation models, the expectations of agents reflect these recurring patterns and are consistent with the equilibrium dynamics of the model. The model is successful if the distributions of equilibrium prices and quantities are consistent with those in the data.

An advantage of this approach is that agents’ expectations do not introduce free parameters. Rational expectations impose cross-equation restrictions on agents’ expectations and equilibrium dynamics that constrain these parameters to be the same. This approach imposes a welcome discipline on the model if there are no data on expectations. By design, the approach assumes that all agents have the same expectations. To study differences in expectations, a researcher has to specify the source of information that only some agents may receive, while others do not.

Recent years have witnessed a massive effort to collect expectational data. These new data enable researchers to be more agnostic about how agents arrive at their expectations. It is now possible to discipline expectations with direct observations on households and firms. More and more surveys that ask respondents about their expectations also ask them about their characteristics (e.g., household or firm age, income, or sales) and choices (e.g., investments). These data allow researchers to study the joint distribution of expectations, characteristics, and choices. Now a model is successful if it can match the observed joint distribution in the data.

Freeing up expectations is especially appealing to study unique episodes that are associated with structural change. In these instances, it is often not clear how agents were forming expectations at the time. For example, what explains postwar house price booms? Two major boom-bust episodes stand out in the United States, because they coincide with booms in other countries (e.g., chapter 4.5 in Piazzesi and Schneider 2016 ). The first boom occurred during the late 1970s and early 1980s, while the second boom occurred in the early 2000s; both episodes had unique features. An important contributor to the first boom was the Great Inflation. How did households form expectations about future inflation during this unique event? Low interest rates during the second boom made it cheap for households to borrow and increased the value of houses, computed as the present value of a stream of future housing services. When house prices collapsed in 2007, interest rates came down further and remained close to zero. Did households during the boom foresee the low rates after the collapse? Did home buyers at the peak of the boom expect house prices to further appreciate, or were they aware that house prices were about to decline? What did renters expect during these years? Again, surveys help us understand households’ expectations and actions during this unique episode. It is difficult to think about these house price booms as recurring patterns.

2.1 Big data collection efforts

Central banks have recently pioneered massive data collection efforts to improve the foundations of their economic models and ultimately their conduct of monetary policy. Many private companies, such as Vanguard, contribute to this effort because they want to better understand their clients. The surveys ask individual households or firms about their expectations for the future. Some surveys ask respondents to forecast aggregate variables: macro-economic indicators (e.g., inflation, GDP growth) or financial variables (e.g., stock returns, bond returns). Other questions ask about individual-specific variables such as income. More and more, surveys ask the same respondents about their expectations and actual choices. For example, households are asked about their stock return forecasts and stock holdings. Other surveys ask firms about their current sales and sales forecasts.