Tim van Gelder

Epistemology is everywhere.

Argument Mapping , Critical Thinking , Education , Expertise , Reasoning , Teaching , Thinking

How are critical thinking skills acquired? Five perspectives

Almost everyone agrees that critical thinking skills are important. Almost everyone agrees that it is worth investing effort (in education, or in workplace training) to improve these skills. And so it is rather surprising to find that there is, in the academic literature, little clarity, and even less consensus, about one of the most basic questions you’d need answered if you wanted to generate any sort of gains in critical thinking skills (let alone generate those gains cost-effectively); viz., how are critical thinking skills acquired?

Theories on this matter come in five main kinds:

- Formal Training. CT skills are simply the exercise of generic thinking power which can be strengthened by intensive training, much as general fitness can be enhanced by running, swimming or weightlifting. This approach recommends working out in some formal ‘mental gym’ such as chess, mathematics or symbolic logic as the most convenient and effective way to build these mental muscles.

- Theoretical Instruction. CT skills are acquired by learning the relevant theory (logic, statistics, scientific method, etc.). This perspective assumes that mastering skills is a matter of gaining the relevant theory . People with poor CT poor skills lack only a theoretical understanding; if they are taught the theory in sufficient detail, they will automatically be able to exhibit the skills, since exhibiting skills is just a matter of following explicit (or explicable) rules.

- Situated Cognition. CT is deeply tied to particular domains and can only be acquired through properly “situated” activity in each domain. Extreme versions deny outright that there are any generic CT skills (e.g. McPeck). Moderate versions claim, more plausibly, that increasingly general skills are acquired through engaging in domain-specific CT activities. According to the moderate version general CT skills emerge gradually in a process of consolidation and abstraction from particular, concrete deployments, much as general sporting skills (e.g., hand-eye coordination) are acquired by playing a variety of particular sports in which those general skills are exercised in ways peculiar to those sports.

- Practice sees CT skills as acquired by directly practicing the general skills themselves, applying them to many particular problems within a wide selection of specific domains and contexts. The Practice perspective differs from Formal Training in that it is general CT skills themselves which are being practiced rather than formal substitutes, and the practice takes place in non-formal domains. It differs from Situated Cognition in that it is practice of general skills aimed at improving those general capacities, rather than embedded deployment of skills aimed at meeting some specific challenge within that domain.

- Evolutionary Psychology views the mind as constituted by an idiosyncratic set of universal, innate, hard-wired cognitive capacities bequeathed by natural selection due to the advantages conferred by those capacities in the particular physical and social environments in which we evolved. The mind does not possess and cannot attain general-purpose CT skills; rather, it can consolidate strengths in those particular forms or patterns of thinking for which evolution has provided dedicated apparatus. Cultivating CT is a matter of identifying and nurturing those forms.

Formal training is the oldest and most thoroughly discredited of the perspectives. It seems now so obvious that teaching latin, chess, music or even formal logic will have little or no impact on general critical thinking skills that it is hard to understand now how this idea could ever have been embraced. And we also know why it fails: it founders on the rock of transfer . Skills acquired in playing chess do not transfer to, say, evaluating political debates. Period.

Theoretical Instruction has almost as old a philosophical pedigree as Formal Training. It has been implemented in countless college critical thinking classes whose pedagogical modus operandi is to teach students “what they need to know” to be better critical thinkers, by lecturing at them and having them read slabs out of textbooks. Token homework exercises are assigned primarily as a way of assessing whether they have acquired the relevant knowledge; if they can’t do the exercises, what they need is more rehearsing of theory. As you can probably tell from the tone of this paragraph, I believe this approach is deeply misguided. The in-depth explanation was provided by philosophers such as Ryle and Heidegger who established the primacy of knowledge-how over knowledge-that, of skills over theory.

Current educational practice subscribes overwhelmingly (and for the most part unwittingly) to the moderate version of Situated Cognition. That is, we typically hope and expect that students’ general CT skills will emerge as a consequence of their engaging in learning and thinking as they proceed through secondary and especially tertiary education studying a range of particular subjects. However, students generally do not reach levels of skill regarded as both desirable and achievable. As Deanna Kuhn put it, “Seldom has there been such widespread agreement about a significant social issue as there is reflected in the view that education is failing in its most central mission—to teach students to think.” In my view the weakness of students’ critical thinking skills, after 12 or even 16 years of schooling, is powerful evidence of the inadequacy of the Situated Cognition perspective.

There may be some truth to the Evolutionary Psychology perspective. However in my view the best argument against it is the fact that another perspective – Practice – actually seems quite promising. The basic idea behind it is very simple and plausible. It is a truism that, in general, skills are acquired through practice. The Practice perspective simply says that generic critical thinking skills are really just like most other skills (that is, most other skills that are acquired, like music or chess or trampolining, rather than skills that are innate and develop naturally, like suckling or walking).

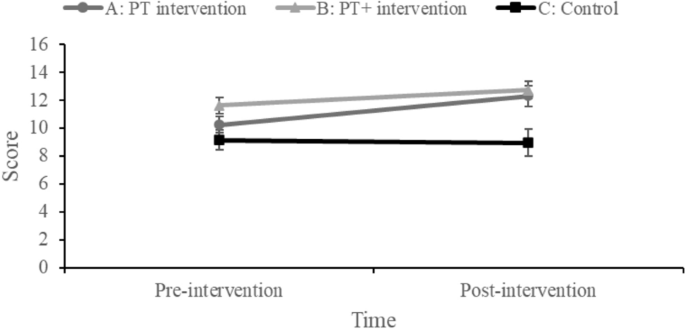

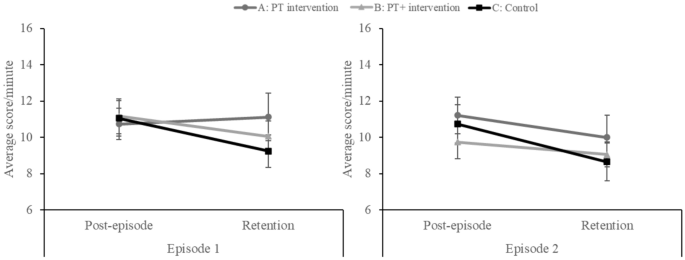

In our work in the Reason Project at the University of Melbourne we refined the Practice perspective into what we called the Quality (or Deliberate) Practice Hypothesis. This was based on the foundational work of Ericsson and others who have shown that skill acquisition in general depends on extensive quality practice. We conjectured that this would also be true of critical thinking; i.e. critical thinking skills would be (best) acquired by doing lots and lots of good-quality practice on a wide range of real (or realistic) critical thinking problems. To improve the quality of practice we developed a training program based around the use of argument mapping, resulting in what has been called the LAMP (Lots of Argument Mapping) approach. In a series of rigorous (or rather, as-rigorous-as-possible-under-the-circumstances) studies involving pre-, post- and follow-up testing using a variety of tests, and setting our results in the context of a meta-analysis of hundreds of other studies of critical thinking gains, we were able to establish that critical thinking skills gains could be dramatically accelerated, with students reliably improving 7-8 times faster, over one semester, than they would otherwise have done just as university students. (For some of the detail on the Quality Practice hypothesis and our studies, see this paper , and this chapter .)

So if I had to choose one theory out of the five on offer, I’d choose Practice. Fortunately however we are not in a forced-choice situation. Practice is enhanced by carefully-placed Theoretical Instruction. And Practice can be reinforced by Situated Cognition, i.e. by engaging in domain-specific critical thinking activities, even when not framed as deliberate practice of general CT skills. As one of the greatest critical thinkers said in one of the greatest texts on critical thinking :

“Popular opinions, on subjects not palpable to sense, are often true, but seldom or never the whole truth. They are a part of the truth; sometimes a greater, sometimes a smaller part, but exaggerated, distorted, and disjoined from the truths by which they ought to be accompanied and limited.”

5 thoughts on “ How are critical thinking skills acquired? Five perspectives ”

Add Comment

- Pingback: Critical Thinking Skills | Knowledge Management and Communication in the Life Sciences

- Pingback: How are critical thinking skills acquired?

I credit LEGOs, the game of MasterMind, and Brit-Com’s. Good parenting, and encouragement and a natural interest in puzzles of all kinds and card games, also helped. Took a while to successfully apply the knowledge to people/social, though; much less black-and-white.

- Pingback: CL Project 2: Critical Thinking | On Language

- Pingback: How are critical thinking skills acquired? | The Thinker

Leave a comment

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Working with sources

- What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples

What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples

Published on May 30, 2022 by Eoghan Ryan . Revised on May 31, 2023.

Critical thinking is the ability to effectively analyze information and form a judgment .

To think critically, you must be aware of your own biases and assumptions when encountering information, and apply consistent standards when evaluating sources .

Critical thinking skills help you to:

- Identify credible sources

- Evaluate and respond to arguments

- Assess alternative viewpoints

- Test hypotheses against relevant criteria

Table of contents

Why is critical thinking important, critical thinking examples, how to think critically, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about critical thinking.

Critical thinking is important for making judgments about sources of information and forming your own arguments. It emphasizes a rational, objective, and self-aware approach that can help you to identify credible sources and strengthen your conclusions.

Critical thinking is important in all disciplines and throughout all stages of the research process . The types of evidence used in the sciences and in the humanities may differ, but critical thinking skills are relevant to both.

In academic writing , critical thinking can help you to determine whether a source:

- Is free from research bias

- Provides evidence to support its research findings

- Considers alternative viewpoints

Outside of academia, critical thinking goes hand in hand with information literacy to help you form opinions rationally and engage independently and critically with popular media.

Prevent plagiarism. Run a free check.

Critical thinking can help you to identify reliable sources of information that you can cite in your research paper . It can also guide your own research methods and inform your own arguments.

Outside of academia, critical thinking can help you to be aware of both your own and others’ biases and assumptions.

Academic examples

However, when you compare the findings of the study with other current research, you determine that the results seem improbable. You analyze the paper again, consulting the sources it cites.

You notice that the research was funded by the pharmaceutical company that created the treatment. Because of this, you view its results skeptically and determine that more independent research is necessary to confirm or refute them. Example: Poor critical thinking in an academic context You’re researching a paper on the impact wireless technology has had on developing countries that previously did not have large-scale communications infrastructure. You read an article that seems to confirm your hypothesis: the impact is mainly positive. Rather than evaluating the research methodology, you accept the findings uncritically.

Nonacademic examples

However, you decide to compare this review article with consumer reviews on a different site. You find that these reviews are not as positive. Some customers have had problems installing the alarm, and some have noted that it activates for no apparent reason.

You revisit the original review article. You notice that the words “sponsored content” appear in small print under the article title. Based on this, you conclude that the review is advertising and is therefore not an unbiased source. Example: Poor critical thinking in a nonacademic context You support a candidate in an upcoming election. You visit an online news site affiliated with their political party and read an article that criticizes their opponent. The article claims that the opponent is inexperienced in politics. You accept this without evidence, because it fits your preconceptions about the opponent.

There is no single way to think critically. How you engage with information will depend on the type of source you’re using and the information you need.

However, you can engage with sources in a systematic and critical way by asking certain questions when you encounter information. Like the CRAAP test , these questions focus on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

When encountering information, ask:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert in their field?

- What do they say? Is their argument clear? Can you summarize it?

- When did they say this? Is the source current?

- Where is the information published? Is it an academic article? Is it peer-reviewed ?

- Why did the author publish it? What is their motivation?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence? Does it rely on opinion, speculation, or appeals to emotion ? Do they address alternative arguments?

Critical thinking also involves being aware of your own biases, not only those of others. When you make an argument or draw your own conclusions, you can ask similar questions about your own writing:

- Am I only considering evidence that supports my preconceptions?

- Is my argument expressed clearly and backed up with credible sources?

- Would I be convinced by this argument coming from someone else?

If you want to know more about ChatGPT, AI tools , citation , and plagiarism , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- ChatGPT vs human editor

- ChatGPT citations

- Is ChatGPT trustworthy?

- Using ChatGPT for your studies

- What is ChatGPT?

- Chicago style

- Paraphrasing

Plagiarism

- Types of plagiarism

- Self-plagiarism

- Avoiding plagiarism

- Academic integrity

- Consequences of plagiarism

- Common knowledge

The only proofreading tool specialized in correcting academic writing - try for free!

The academic proofreading tool has been trained on 1000s of academic texts and by native English editors. Making it the most accurate and reliable proofreading tool for students.

Try for free

Critical thinking refers to the ability to evaluate information and to be aware of biases or assumptions, including your own.

Like information literacy , it involves evaluating arguments, identifying and solving problems in an objective and systematic way, and clearly communicating your ideas.

Critical thinking skills include the ability to:

You can assess information and arguments critically by asking certain questions about the source. You can use the CRAAP test , focusing on the currency , relevance , authority , accuracy , and purpose of a source of information.

Ask questions such as:

- Who is the author? Are they an expert?

- How do they make their argument? Is it backed up by evidence?

A credible source should pass the CRAAP test and follow these guidelines:

- The information should be up to date and current.

- The author and publication should be a trusted authority on the subject you are researching.

- The sources the author cited should be easy to find, clear, and unbiased.

- For a web source, the URL and layout should signify that it is trustworthy.

Information literacy refers to a broad range of skills, including the ability to find, evaluate, and use sources of information effectively.

Being information literate means that you:

- Know how to find credible sources

- Use relevant sources to inform your research

- Understand what constitutes plagiarism

- Know how to cite your sources correctly

Confirmation bias is the tendency to search, interpret, and recall information in a way that aligns with our pre-existing values, opinions, or beliefs. It refers to the ability to recollect information best when it amplifies what we already believe. Relatedly, we tend to forget information that contradicts our opinions.

Although selective recall is a component of confirmation bias, it should not be confused with recall bias.

On the other hand, recall bias refers to the differences in the ability between study participants to recall past events when self-reporting is used. This difference in accuracy or completeness of recollection is not related to beliefs or opinions. Rather, recall bias relates to other factors, such as the length of the recall period, age, and the characteristics of the disease under investigation.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

Ryan, E. (2023, May 31). What Is Critical Thinking? | Definition & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved March 25, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/working-with-sources/critical-thinking/

Is this article helpful?

Eoghan Ryan

Other students also liked, student guide: information literacy | meaning & examples, what are credible sources & how to spot them | examples, applying the craap test & evaluating sources, "i thought ai proofreading was useless but..".

I've been using Scribbr for years now and I know it's a service that won't disappoint. It does a good job spotting mistakes”

Defining Critical Thinking

- A Brief History of the Idea of Critical Thinking

- Critical Thinking: Basic Questions & Answers

- Our Conception of Critical Thinking

- Sumner’s Definition of Critical Thinking

- Research in Critical Thinking

- Critical Societies: Thoughts from the Past

Translate this page from English...

*Machine translated pages not guaranteed for accuracy. Click Here for our professional translations.

For full copies of this and many other critical thinking articles, books, videos, and more, join us at the Center for Critical Thinking Community Online - the world's leading online community dedicated to critical thinking! Also featuring interactive learning activities, study groups, and even a social media component, this learning platform will change your conception of intellectual development.

Critical Thinking Definition, Skills, and Examples

- Homework Help

- Private School

- College Admissions

- College Life

- Graduate School

- Business School

- Distance Learning

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/ADHeadshot-Cropped-b80e40469d5b4852a68f94ad69d6e8bd.jpg)

- Indiana University, Bloomington

- State University of New York at Oneonta

Critical thinking refers to the ability to analyze information objectively and make a reasoned judgment. It involves the evaluation of sources, such as data, facts, observable phenomena, and research findings.

Good critical thinkers can draw reasonable conclusions from a set of information, and discriminate between useful and less useful details to solve problems or make decisions. Employers prioritize the ability to think critically—find out why, plus see how you can demonstrate that you have this ability throughout the job application process.

Why Do Employers Value Critical Thinking Skills?

Employers want job candidates who can evaluate a situation using logical thought and offer the best solution.

Someone with critical thinking skills can be trusted to make decisions independently, and will not need constant handholding.

Hiring a critical thinker means that micromanaging won't be required. Critical thinking abilities are among the most sought-after skills in almost every industry and workplace. You can demonstrate critical thinking by using related keywords in your resume and cover letter, and during your interview.

Examples of Critical Thinking

The circumstances that demand critical thinking vary from industry to industry. Some examples include:

- A triage nurse analyzes the cases at hand and decides the order by which the patients should be treated.

- A plumber evaluates the materials that would best suit a particular job.

- An attorney reviews evidence and devises a strategy to win a case or to decide whether to settle out of court.

- A manager analyzes customer feedback forms and uses this information to develop a customer service training session for employees.

Promote Your Skills in Your Job Search

If critical thinking is a key phrase in the job listings you are applying for, be sure to emphasize your critical thinking skills throughout your job search.

Add Keywords to Your Resume

You can use critical thinking keywords (analytical, problem solving, creativity, etc.) in your resume. When describing your work history , include top critical thinking skills that accurately describe you. You can also include them in your resume summary , if you have one.

For example, your summary might read, “Marketing Associate with five years of experience in project management. Skilled in conducting thorough market research and competitor analysis to assess market trends and client needs, and to develop appropriate acquisition tactics.”

Mention Skills in Your Cover Letter

Include these critical thinking skills in your cover letter. In the body of your letter, mention one or two of these skills, and give specific examples of times when you have demonstrated them at work. Think about times when you had to analyze or evaluate materials to solve a problem.

Show the Interviewer Your Skills

You can use these skill words in an interview. Discuss a time when you were faced with a particular problem or challenge at work and explain how you applied critical thinking to solve it.

Some interviewers will give you a hypothetical scenario or problem, and ask you to use critical thinking skills to solve it. In this case, explain your thought process thoroughly to the interviewer. He or she is typically more focused on how you arrive at your solution rather than the solution itself. The interviewer wants to see you analyze and evaluate (key parts of critical thinking) the given scenario or problem.

Of course, each job will require different skills and experiences, so make sure you read the job description carefully and focus on the skills listed by the employer.

Top Critical Thinking Skills

Keep these in-demand critical thinking skills in mind as you update your resume and write your cover letter. As you've seen, you can also emphasize them at other points throughout the application process, such as your interview.

Part of critical thinking is the ability to carefully examine something, whether it is a problem, a set of data, or a text. People with analytical skills can examine information, understand what it means, and properly explain to others the implications of that information.

- Asking Thoughtful Questions

- Data Analysis

- Interpretation

- Questioning Evidence

- Recognizing Patterns

Communication

Often, you will need to share your conclusions with your employers or with a group of colleagues. You need to be able to communicate with others to share your ideas effectively. You might also need to engage in critical thinking in a group. In this case, you will need to work with others and communicate effectively to figure out solutions to complex problems.

- Active Listening

- Collaboration

- Explanation

- Interpersonal

- Presentation

- Verbal Communication

- Written Communication

Critical thinking often involves creativity and innovation. You might need to spot patterns in the information you are looking at or come up with a solution that no one else has thought of before. All of this involves a creative eye that can take a different approach from all other approaches.

- Flexibility

- Conceptualization

- Imagination

- Drawing Connections

- Synthesizing

Open-Mindedness

To think critically, you need to be able to put aside any assumptions or judgments and merely analyze the information you receive. You need to be objective, evaluating ideas without bias.

- Objectivity

- Observation

Problem Solving

Problem-solving is another critical thinking skill that involves analyzing a problem, generating and implementing a solution, and assessing the success of the plan. Employers don’t simply want employees who can think about information critically. They also need to be able to come up with practical solutions.

- Attention to Detail

- Clarification

- Decision Making

- Groundedness

- Identifying Patterns

More Critical Thinking Skills

- Inductive Reasoning

- Deductive Reasoning

- Noticing Outliers

- Adaptability

- Emotional Intelligence

- Brainstorming

- Optimization

- Restructuring

- Integration

- Strategic Planning

- Project Management

- Ongoing Improvement

- Causal Relationships

- Case Analysis

- Diagnostics

- SWOT Analysis

- Business Intelligence

- Quantitative Data Management

- Qualitative Data Management

- Risk Management

- Scientific Method

- Consumer Behavior

Key Takeaways

- Demonstrate that you have critical thinking skills by adding relevant keywords to your resume.

- Mention pertinent critical thinking skills in your cover letter, too, and include an example of a time when you demonstrated them at work.

- Finally, highlight critical thinking skills during your interview. For instance, you might discuss a time when you were faced with a challenge at work and explain how you applied critical thinking skills to solve it.

University of Louisville. " What is Critical Thinking ."

American Management Association. " AMA Critical Skills Survey: Workers Need Higher Level Skills to Succeed in the 21st Century ."

- How To Become an Effective Problem Solver

- 2020-21 Common Application Essay Option 4—Solving a Problem

- College Interview Tips: "Tell Me About a Challenge You Overcame"

- Types of Medical School Interviews and What to Expect

- The Horse Problem: A Math Challenge

- What to Do When the Technology Fails in Class

- A Guide to Business Letters Types

- Landing Your First Teaching Job

- How to Facilitate Learning and Critical Thinking

- Best Majors for Pre-med Students

- Problem Solving in Mathematics

- Discover Ideas Through Brainstorming

- What You Need to Know About the Executive Assessment

- Finding a Job for ESL Learners: Interview Basics

- Finding a Job for ESL Learners

- Job Interview Questions and Answers

- Programs & Services

- Delphi Center

Ideas to Action (i2a)

- What is Critical Thinking?

The ability to think critically calls for a higher-order thinking than simply the ability to recall information.

Definitions of critical thinking, its elements, and its associated activities fill the educational literature of the past forty years. Critical thinking has been described as an ability to question; to acknowledge and test previously held assumptions; to recognize ambiguity; to examine, interpret, evaluate, reason, and reflect; to make informed judgments and decisions; and to clarify, articulate, and justify positions (Hullfish & Smith, 1961; Ennis, 1962; Ruggiero, 1975; Scriven, 1976; Hallet, 1984; Kitchener, 1986; Pascarella & Terenzini, 1991; Mines et al., 1990; Halpern, 1996; Paul & Elder, 2001; Petress, 2004; Holyoak & Morrison, 2005; among others).

After a careful review of the mountainous body of literature defining critical thinking and its elements, UofL has chosen to adopt the language of Michael Scriven and Richard Paul (2003) as a comprehensive, concise operating definition:

Critical thinking is the intellectually disciplined process of actively and skillfully conceptualizing, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, and/or evaluating information gathered from, or generated by, observation, experience, reflection, reasoning, or communication, as a guide to belief and action.

Paul and Scriven go on to suggest that critical thinking is based on: "universal intellectual values that transcend subject matter divisions: clarity, accuracy, precision, consistency, relevance, sound evidence, good reasons, depth, breadth, and fairness. It entails the examination of those structures or elements of thought implicit in all reasoning: purpose, problem, or question-at-issue, assumptions, concepts, empirical grounding; reasoning leading to conclusions, implication and consequences, objections from alternative viewpoints, and frame of reference. Critical thinking - in being responsive to variable subject matter, issues, and purposes - is incorporated in a family of interwoven modes of thinking, among them: scientific thinking, mathematical thinking, historical thinking, anthropological thinking, economic thinking, moral thinking, and philosophical thinking."

This conceptualization of critical thinking has been refined and developed further by Richard Paul and Linder Elder into the Paul-Elder framework of critical thinking. Currently, this approach is one of the most widely published and cited frameworks in the critical thinking literature. According to the Paul-Elder framework, critical thinking is the:

- Analysis of thinking by focusing on the parts or structures of thinking ("the Elements of Thought")

- Evaluation of thinking by focusing on the quality ("the Universal Intellectual Standards")

- Improvement of thinking by using what you have learned ("the Intellectual Traits")

Selection of a Critical Thinking Framework

The University of Louisville chose the Paul-Elder model of Critical Thinking as the approach to guide our efforts in developing and enhancing our critical thinking curriculum. The Paul-Elder framework was selected based on criteria adapted from the characteristics of a good model of critical thinking developed at Surry Community College. The Paul-Elder critical thinking framework is comprehensive, uses discipline-neutral terminology, is applicable to all disciplines, defines specific cognitive skills including metacognition, and offers high quality resources.

Why the selection of a single critical thinking framework?

The use of a single critical thinking framework is an important aspect of institution-wide critical thinking initiatives (Paul and Nosich, 1993; Paul, 2004). According to this view, critical thinking instruction should not be relegated to one or two disciplines or departments with discipline specific language and conceptualizations. Rather, critical thinking instruction should be explicitly infused in all courses so that critical thinking skills can be developed and reinforced in student learning across the curriculum. The use of a common approach with a common language allows for a central organizer and for the development of critical thinking skill sets in all courses.

- SACS & QEP

- Planning and Implementation

- Why Focus on Critical Thinking?

- Paul-Elder Critical Thinking Framework

- Culminating Undergraduate Experience

- Community Engagement

- Frequently Asked Questions

- What is i2a?

Copyright © 2012 - University of Louisville , Delphi Center

How it works

For Business

Join Mind Tools

Article • 8 min read

Critical Thinking

Developing the right mindset and skills.

By the Mind Tools Content Team

We make hundreds of decisions every day and, whether we realize it or not, we're all critical thinkers.

We use critical thinking each time we weigh up our options, prioritize our responsibilities, or think about the likely effects of our actions. It's a crucial skill that helps us to cut out misinformation and make wise decisions. The trouble is, we're not always very good at it!

In this article, we'll explore the key skills that you need to develop your critical thinking skills, and how to adopt a critical thinking mindset, so that you can make well-informed decisions.

What Is Critical Thinking?

Critical thinking is the discipline of rigorously and skillfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions, and beliefs. You'll need to actively question every step of your thinking process to do it well.

Collecting, analyzing and evaluating information is an important skill in life, and a highly valued asset in the workplace. People who score highly in critical thinking assessments are also rated by their managers as having good problem-solving skills, creativity, strong decision-making skills, and good overall performance. [1]

Key Critical Thinking Skills

Critical thinkers possess a set of key characteristics which help them to question information and their own thinking. Focus on the following areas to develop your critical thinking skills:

Being willing and able to explore alternative approaches and experimental ideas is crucial. Can you think through "what if" scenarios, create plausible options, and test out your theories? If not, you'll tend to write off ideas and options too soon, so you may miss the best answer to your situation.

To nurture your curiosity, stay up to date with facts and trends. You'll overlook important information if you allow yourself to become "blinkered," so always be open to new information.

But don't stop there! Look for opposing views or evidence to challenge your information, and seek clarification when things are unclear. This will help you to reassess your beliefs and make a well-informed decision later. Read our article, Opening Closed Minds , for more ways to stay receptive.

Logical Thinking

You must be skilled at reasoning and extending logic to come up with plausible options or outcomes.

It's also important to emphasize logic over emotion. Emotion can be motivating but it can also lead you to take hasty and unwise action, so control your emotions and be cautious in your judgments. Know when a conclusion is "fact" and when it is not. "Could-be-true" conclusions are based on assumptions and must be tested further. Read our article, Logical Fallacies , for help with this.

Use creative problem solving to balance cold logic. By thinking outside of the box you can identify new possible outcomes by using pieces of information that you already have.

Self-Awareness

Many of the decisions we make in life are subtly informed by our values and beliefs. These influences are called cognitive biases and it can be difficult to identify them in ourselves because they're often subconscious.

Practicing self-awareness will allow you to reflect on the beliefs you have and the choices you make. You'll then be better equipped to challenge your own thinking and make improved, unbiased decisions.

One particularly useful tool for critical thinking is the Ladder of Inference . It allows you to test and validate your thinking process, rather than jumping to poorly supported conclusions.

Developing a Critical Thinking Mindset

Combine the above skills with the right mindset so that you can make better decisions and adopt more effective courses of action. You can develop your critical thinking mindset by following this process:

Gather Information

First, collect data, opinions and facts on the issue that you need to solve. Draw on what you already know, and turn to new sources of information to help inform your understanding. Consider what gaps there are in your knowledge and seek to fill them. And look for information that challenges your assumptions and beliefs.

Be sure to verify the authority and authenticity of your sources. Not everything you read is true! Use this checklist to ensure that your information is valid:

- Are your information sources trustworthy ? (For example, well-respected authors, trusted colleagues or peers, recognized industry publications, websites, blogs, etc.)

- Is the information you have gathered up to date ?

- Has the information received any direct criticism ?

- Does the information have any errors or inaccuracies ?

- Is there any evidence to support or corroborate the information you have gathered?

- Is the information you have gathered subjective or biased in any way? (For example, is it based on opinion, rather than fact? Is any of the information you have gathered designed to promote a particular service or organization?)

If any information appears to be irrelevant or invalid, don't include it in your decision making. But don't omit information just because you disagree with it, or your final decision will be flawed and bias.

Now observe the information you have gathered, and interpret it. What are the key findings and main takeaways? What does the evidence point to? Start to build one or two possible arguments based on what you have found.

You'll need to look for the details within the mass of information, so use your powers of observation to identify any patterns or similarities. You can then analyze and extend these trends to make sensible predictions about the future.

To help you to sift through the multiple ideas and theories, it can be useful to group and order items according to their characteristics. From here, you can compare and contrast the different items. And once you've determined how similar or different things are from one another, Paired Comparison Analysis can help you to analyze them.

The final step involves challenging the information and rationalizing its arguments.

Apply the laws of reason (induction, deduction, analogy) to judge an argument and determine its merits. To do this, it's essential that you can determine the significance and validity of an argument to put it in the correct perspective. Take a look at our article, Rational Thinking , for more information about how to do this.

Once you have considered all of the arguments and options rationally, you can finally make an informed decision.

Afterward, take time to reflect on what you have learned and what you found challenging. Step back from the detail of your decision or problem, and look at the bigger picture. Record what you've learned from your observations and experience.

Critical thinking involves rigorously and skilfully using information, experience, observation, and reasoning to guide your decisions, actions and beliefs. It's a useful skill in the workplace and in life.

You'll need to be curious and creative to explore alternative possibilities, but rational to apply logic, and self-aware to identify when your beliefs could affect your decisions or actions.

You can demonstrate a high level of critical thinking by validating your information, analyzing its meaning, and finally evaluating the argument.

Critical Thinking Infographic

See Critical Thinking represented in our infographic: An Elementary Guide to Critical Thinking .

You've accessed 1 of your 2 free resources.

Get unlimited access

Discover more content

How to Guides

Planning Your Continuing Professional Development

Assess and Address Your CPD Needs

Book Insights

Do More Great Work: Stop the Busywork. Start the Work That Matters.

Michael Bungay Stanier

Add comment

Comments (1)

priyanka ghogare

Get 20% off your first year of Mind Tools

Our on-demand e-learning resources let you learn at your own pace, fitting seamlessly into your busy workday. Join today and save with our limited time offer!

Sign-up to our newsletter

Subscribing to the Mind Tools newsletter will keep you up-to-date with our latest updates and newest resources.

Subscribe now

Business Skills

Personal Development

Leadership and Management

Member Extras

Most Popular

Newest Releases

Pain Points Podcast - Balancing Work And Kids

Pain Points Podcast - Improving Culture

Mind Tools Store

About Mind Tools Content

Discover something new today

Pain points podcast - what is ai.

Exploring Artificial Intelligence

Pain Points Podcast - How Do I Get Organized?

It's Time to Get Yourself Sorted!

How Emotionally Intelligent Are You?

Boosting Your People Skills

Self-Assessment

What's Your Leadership Style?

Learn About the Strengths and Weaknesses of the Way You Like to Lead

Recommended for you

Business Operations and Process Management

Strategy Tools

Customer Service

Business Ethics and Values

Handling Information and Data

Project Management

Knowledge Management

Self-Development and Goal Setting

Time Management

Presentation Skills

Learning Skills

Career Skills

Communication Skills

Negotiation, Persuasion and Influence

Working With Others

Difficult Conversations

Creativity Tools

Self-Management

Work-Life Balance

Stress Management and Wellbeing

Coaching and Mentoring

Change Management

Team Management

Managing Conflict

Delegation and Empowerment

Performance Management

Leadership Skills

Developing Your Team

Talent Management

Problem Solving

Decision Making

Member Podcast

How it works

Transform your enterprise with the scalable mindsets, skills, & behavior change that drive performance.

Explore how BetterUp connects to your core business systems.

We pair AI with the latest in human-centered coaching to drive powerful, lasting learning and behavior change.

Build leaders that accelerate team performance and engagement.

Unlock performance potential at scale with AI-powered curated growth journeys.

Build resilience, well-being and agility to drive performance across your entire enterprise.

Transform your business, starting with your sales leaders.

Unlock business impact from the top with executive coaching.

Foster a culture of inclusion and belonging.

Accelerate the performance and potential of your agencies and employees.

See how innovative organizations use BetterUp to build a thriving workforce.

Discover how BetterUp measurably impacts key business outcomes for organizations like yours.

A demo is the first step to transforming your business. Meet with us to develop a plan for attaining your goals.

- What is coaching?

Learn how 1:1 coaching works, who its for, and if it's right for you.

Accelerate your personal and professional growth with the expert guidance of a BetterUp Coach.

Types of Coaching

Navigate career transitions, accelerate your professional growth, and achieve your career goals with expert coaching.

Enhance your communication skills for better personal and professional relationships, with tailored coaching that focuses on your needs.

Find balance, resilience, and well-being in all areas of your life with holistic coaching designed to empower you.

Discover your perfect match : Take our 5-minute assessment and let us pair you with one of our top Coaches tailored just for you.

Best practices, research, and tools to fuel individual and business growth.

View on-demand BetterUp events and learn about upcoming live discussions.

The latest insights and ideas for building a high-performing workplace.

- BetterUp Briefing

The online magazine that helps you understand tomorrow's workforce trends, today.

Innovative research featured in peer-reviewed journals, press, and more.

Founded in 2022 to deepen the understanding of the intersection of well-being, purpose, and performance

We're on a mission to help everyone live with clarity, purpose, and passion.

Join us and create impactful change.

Read the buzz about BetterUp.

Meet the leadership that's passionate about empowering your workforce.

For Business

For Individuals

How to develop critical thinking skills

Cultivate your creativity

Foster creativity and continuous learning with guidance from our certified Coaches.

Jump to section

What are critical thinking skills?

How to develop critical thinking skills: 12 tips, how to practice critical thinking skills at work, become your own best critic.

A client requests a tight deadline on an intense project. Your childcare provider calls in sick on a day full of meetings. Payment from a contract gig is a month behind.

Your day-to-day will always have challenges, big and small. And no matter the size and urgency, they all ask you to use critical thinking to analyze the situation and arrive at the right solution.

Critical thinking includes a wide set of soft skills that encourage continuous learning, resilience , and self-reflection. The more you add to your professional toolbelt, the more equipped you’ll be to tackle whatever challenge presents itself. Here’s how to develop critical thinking, with examples explaining how to use it.

Critical thinking skills are the skills you use to analyze information, imagine scenarios holistically, and create rational solutions. It’s a type of emotional intelligence that stimulates effective problem-solving and decision-making .

When you fine-tune your critical thinking skills, you seek beyond face-value observations and knee-jerk reactions. Instead, you harvest deeper insights and string together ideas and concepts in logical, sometimes out-of-the-box , ways.

Imagine a team working on a marketing strategy for a new set of services. That team might use critical thinking to balance goals and key performance indicators , like new customer acquisition costs, average monthly sales, and net profit margins. They understand the connections between overlapping factors to build a strategy that stays within budget and attracts new sales.

Looking for ways to improve critical thinking skills? Start by brushing up on the following soft skills that fall under this umbrella:

- Analytical thinking: Approaching problems with an analytical eye includes breaking down complex issues into small chunks and examining their significance. An example could be organizing customer feedback to identify trends and improve your product offerings.

- Open-mindedness: Push past cognitive biases and be receptive to different points of view and constructive feedback . Managers and team members who keep an open mind position themselves to hear new ideas that foster innovation .

- Creative thinking: With creative thinking , you can develop several ideas to address a single problem, like brainstorming more efficient workflow best practices to boost productivity and employee morale .

- Self-reflection: Self-reflection lets you examine your thinking and assumptions to stimulate healthier collaboration and thought processes. Maybe a bad first impression created a negative anchoring bias with a new coworker. Reflecting on your own behavior stirs up empathy and improves the relationship.

- Evaluation: With evaluation skills, you tackle the pros and cons of a situation based on logic rather than emotion. When prioritizing tasks , you might be tempted to do the fun or easy ones first, but evaluating their urgency and importance can help you make better decisions.

There’s no magic method to change your thinking processes. Improvement happens with small, intentional changes to your everyday habits until a more critical approach to thinking is automatic.

Here are 12 tips for building stronger self-awareness and learning how to improve critical thinking:

1. Be cautious

There’s nothing wrong with a little bit of skepticism. One of the core principles of critical thinking is asking questions and dissecting the available information. You might surprise yourself at what you find when you stop to think before taking action.

Before making a decision, use evidence, logic, and deductive reasoning to support your own opinions or challenge ideas. It helps you and your team avoid falling prey to bad information or resistance to change .

2. Ask open-ended questions

“Yes” or “no” questions invite agreement rather than reflection. Instead, ask open-ended questions that force you to engage in analysis and rumination. Digging deeper can help you identify potential biases, uncover assumptions, and arrive at new hypotheses and possible solutions.

3. Do your research

No matter your proficiency, you can always learn more. Turning to different points of view and information is a great way to develop a comprehensive understanding of a topic and make informed decisions. You’ll prioritize reliable information rather than fall into emotional or automatic decision-making.

4. Consider several opinions

You might spend so much time on your work that it’s easy to get stuck in your own perspective, especially if you work independently on a remote team . Make an effort to reach out to colleagues to hear different ideas and thought patterns. Their input might surprise you.

If or when you disagree, remember that you and your team share a common goal. Divergent opinions are constructive, so shift the focus to finding solutions rather than defending disagreements.

5. Learn to be quiet

Active listening is the intentional practice of concentrating on a conversation partner instead of your own thoughts. It’s about paying attention to detail and letting people know you value their opinions, which can open your mind to new perspectives and thought processes.

If you’re brainstorming with your team or having a 1:1 with a coworker , listen, ask clarifying questions, and work to understand other peoples’ viewpoints. Listening to your team will help you find fallacies in arguments to improve possible solutions.

6. Schedule reflection

Whether waking up at 5 am or using a procrastination hack, scheduling time to think puts you in a growth mindset . Your mind has natural cognitive biases to help you simplify decision-making, but squashing them is key to thinking critically and finding new solutions besides the ones you might gravitate toward. Creating time and calm space in your day gives you the chance to step back and visualize the biases that impact your decision-making.

7. Cultivate curiosity

With so many demands and job responsibilities, it’s easy to seek solace in routine. But getting out of your comfort zone helps spark critical thinking and find more solutions than you usually might.

If curiosity doesn’t come naturally to you, cultivate a thirst for knowledge by reskilling and upskilling . Not only will you add a new skill to your resume , but expanding the limits of your professional knowledge might motivate you to ask more questions.

You don’t have to develop critical thinking skills exclusively in the office. Whether on your break or finding a hobby to do after work, playing strategic games or filling out crosswords can prime your brain for problem-solving.

9. Write it down

Recording your thoughts with pen and paper can lead to stronger brain activity than typing them out on a keyboard. If you’re stuck and want to think more critically about a problem, writing your ideas can help you process information more deeply.

The act of recording ideas on paper can also improve your memory . Ideas are more likely to linger in the background of your mind, leading to deeper thinking that informs your decision-making process.

10. Speak up

Take opportunities to share your opinion, even if it intimidates you. Whether at a networking event with new people or a meeting with close colleagues, try to engage with people who challenge or help you develop your ideas. Having conversations that force you to support your position encourages you to refine your argument and think critically.

11. Stay humble

Ideas and concepts aren’t the same as real-life actions. There may be such a thing as negative outcomes, but there’s no such thing as a bad idea. At the brainstorming stage , don’t be afraid to make mistakes.

Sometimes the best solutions come from off-the-wall, unorthodox decisions. Sit in your creativity , let ideas flow, and don’t be afraid to share them with your colleagues. Putting yourself in a creative mindset helps you see situations from new perspectives and arrive at innovative conclusions.

12. Embrace discomfort

Get comfortable feeling uncomfortable . It isn’t easy when others challenge your ideas, but sometimes, it’s the only way to see new perspectives and think critically.

By willingly stepping into unfamiliar territory, you foster the resilience and flexibility you need to become a better thinker. You’ll learn how to pick yourself up from failure and approach problems from fresh angles.

Thinking critically is easier said than done. To help you understand its impact (and how to use it), here are two scenarios that require critical thinking skills and provide teachable moments.

Scenario #1: Unexpected delays and budget

Imagine your team is working on producing an event. Unexpectedly, a vendor explains they’ll be a week behind on delivering materials. Then another vendor sends a quote that’s more than you can afford. Unless you develop a creative solution, the team will have to push back deadlines and go over budget, potentially costing the client’s trust.

Here’s how you could approach the situation with creative thinking:

- Analyze the situation holistically: Determine how the delayed materials and over-budget quote will impact the rest of your timeline and financial resources . That way, you can identify whether you need to build an entirely new plan with new vendors, or if it’s worth it to readjust time and resources.

- Identify your alternative options: With careful assessment, your team decides that another vendor can’t provide the same materials in a quicker time frame. You’ll need to rearrange assignment schedules to complete everything on time.

- Collaborate and adapt: Your team has an emergency meeting to rearrange your project schedule. You write down each deliverable and determine which ones you can and can’t complete by the deadline. To compensate for lost time, you rearrange your task schedule to complete everything that doesn’t need the delayed materials first, then advance as far as you can on the tasks that do.

- Check different resources: In the meantime, you scour through your contact sheet to find alternative vendors that fit your budget. Accounting helps by providing old invoices to determine which vendors have quoted less for previous jobs. After pulling all your sources, you find a vendor that fits your budget.

- Maintain open communication: You create a special Slack channel to keep everyone up to date on changes, challenges, and additional delays. Keeping an open line encourages transparency on the team’s progress and boosts everyone’s confidence.

Scenario #2: Differing opinions

A conflict arises between two team members on the best approach for a new strategy for a gaming app. One believes that small tweaks to the current content are necessary to maintain user engagement and stay within budget. The other believes a bold revamp is needed to encourage new followers and stronger sales revenue.

Here’s how critical thinking could help this conflict:

- Listen actively: Give both team members the opportunity to present their ideas free of interruption. Encourage the entire team to ask open-ended questions to more fully understand and develop each argument.

- Flex your analytical skills: After learning more about both ideas, everyone should objectively assess the benefits and drawbacks of each approach. Analyze each idea's risk, merits, and feasibility based on available data and the app’s goals and objectives.

- Identify common ground: The team discusses similarities between each approach and brainstorms ways to integrate both idea s, like making small but eye-catching modifications to existing content or using the same visual design in new media formats.

- Test new strategy: To test out the potential of a bolder strategy, the team decides to A/B test both approaches. You create a set of criteria to evenly distribute users by different demographics to analyze engagement, revenue, and customer turnover.

- Monitor and adapt: After implementing the A/B test, the team closely monitors the results of each strategy. You regroup and optimize the changes that provide stronger results after the testing. That way, all team members understand why you’re making the changes you decide to make.

You can’t think your problems away. But you can equip yourself with skills that help you move through your biggest challenges and find innovative solutions. Learning how to develop critical thinking is the start of honing an adaptable growth mindset.

Now that you have resources to increase critical thinking skills in your professional development, you can identify whether you embrace change or routine, are open or resistant to feedback, or turn to research or emotion will build self-awareness. From there, tweak and incorporate techniques to be a critical thinker when life presents you with a problem.

Elizabeth Perry, ACC

Elizabeth Perry is a Coach Community Manager at BetterUp. She uses strategic engagement strategies to cultivate a learning community across a global network of Coaches through in-person and virtual experiences, technology-enabled platforms, and strategic coaching industry partnerships. With over 3 years of coaching experience and a certification in transformative leadership and life coaching from Sofia University, Elizabeth leverages transpersonal psychology expertise to help coaches and clients gain awareness of their behavioral and thought patterns, discover their purpose and passions, and elevate their potential. She is a lifelong student of psychology, personal growth, and human potential as well as an ICF-certified ACC transpersonal life and leadership Coach.

How divergent thinking can drive your creativity

How to improve your creative skills for effective problem-solving, what’s convergent thinking how to be a better problem-solver, can dreams help you solve problems 6 ways to try, 6 ways to leverage ai for hyper-personalized corporate learning, what is lateral thinking 7 techniques to encourage creative ideas, 8 creative solutions to your most challenging problems, thinking outside the box: 8 ways to become a creative problem solver, critical thinking is the one skillset you can't afford not to master, similar articles, what is creative thinking and why does it matter, discover the 7 essential types of life skills you need, 6 big picture thinking strategies that you'll actually use, what are analytical skills examples and how to level up, how intrapersonal skills shape teams, plus 5 ways to build them, stay connected with betterup, get our newsletter, event invites, plus product insights and research..

3100 E 5th Street, Suite 350 Austin, TX 78702

- Platform Overview

- Integrations

- Powered by AI

- BetterUp Lead

- BetterUp Manage™

- BetterUp Care™

- Sales Performance

- Diversity & Inclusion

- Case Studies

- Why BetterUp?

- About Coaching

- Find your Coach

- Career Coaching

- Communication Coaching

- Life Coaching

- News and Press

- Leadership Team

- Become a BetterUp Coach

- BetterUp Labs

- Center for Purpose & Performance

- Leadership Training

- Business Coaching

- Contact Support

- Contact Sales

- Privacy Policy

- Acceptable Use Policy

- Trust & Security

- Cookie Preferences

The State of Critical Thinking 2020

November 2020, introduction.

In 2018, the Reboot Foundation released a first-of-its-kind survey looking at the public’s attitudes toward critical thinking and critical thinking education. The report found that critical thinking skills are highly valued, but not taught or practiced as much as might be hoped for in schools or in public life.

The survey suggested that, despite recognizing the importance of critical thinking, when it came to critical thinking practices—like seeking out multiple sources of information and engaging others with opposing views—many people’s habits were lacking. Significant numbers of respondents reported relying on inadequate sources of information, making decisions without doing enough research, and avoiding those with conflicting viewpoints.

In late 2019, the Foundation conducted a follow up survey in order to see how the landscape may have shifted. Without question, the stakes surrounding better reasoning have increased. The COVID-19 pandemic requires deeper interpretive and analytical skills. For instance, when it comes to news about a possible vaccine, people need to assess how it was developed in order to judge whether it will actually work.

Misinformation, from both foreign and domestic sources, continues to proliferate online and, perhaps most disturbingly, surrounding the COVID-19 health crisis. Meanwhile, political polarization has deepened and become more personal . At the same time, there’s both a growing awareness and divide over issues of racism and inequality. If that wasn’t enough, changes to the journalism industry have weakened local civic life and incentivized clickbait, and sensationalized and siloed content.

Part of the problem is that much of our public discourse takes place online, where cognitive biases can become amplified, and where groupthink and filter bubbles proliferate. Meanwhile, face-to-face conversations—which can dissolve misunderstandings and help us recognize the shared humanity of those we disagree with—go missing.

Critical thinking is, of course, not a cure-all, but a lack of critical thinking skills across the population exacerbates all these problems. More than ever, we need skills and practice in managing our emotions, stepping back from quick-trigger evaluations and decisions, and over-relying on biased or false sources of information.

To keep apprised of the public’s view of critical thinking, the Reboot Foundation conducted its second annual survey in late 2019. Unfortunately, the COVID-19 pandemic forced a delay in the release of the results. Nevertheless, this most recent survey dug deeper than our 2018 poll, and looked especially into how the public understands the state of critical thinking education. For the first time, our team also surveyed teachers on their views on teaching critical thinking.

General Findings

Support for critical thinking skills remains high, but there is also clearly skepticism that individuals are getting the help they need to acquire improved reasoning skills. A very high majority of people surveyed (94 percent) believe that critical thinking is “extremely” or “very important.” But they generally (86 percent) find those skills lacking in the public at large. Indeed, 60 percent of the respondents reported not having studied critical thinking in school. And only about 55 percent reported that their critical thinking skills had improved since high school, with almost a quarter reporting that those skills had deteriorated.

There is also broad support among the public and teachers for critical thinking education, both at the K-12 and collegiate levels. For example, 90 percent think courses covering critical thinking should be required in K-12.

Many respondents (43 percent) also encouragingly identified early childhood as the best age to develop critical thinking skills. This was a big increase from our previous survey (just 20 percent) and is consistent with the general consensus among social scientists and psychologists.

There are worrisome trends—and promising signs—in critical thinking habits and daily practices. In particular, individuals still don’t do enough to engage people with whom they disagree.

Given the deficits in critical thinking acquisition during school, we would hope that respondents’ critical thinking skills continued to improve after they’ve left school. But only about 55 percent reported that their critical thinking skills had improved since high school, with almost a quarter reporting that their skills had actually deteriorated since then.

Questions about respondents’ critical thinking habits brought out some encouraging information. People reported using more than one source of information when making a decision at a high rate (around 77 percent said they did this “always” or “often”) and giving reasons for their opinions (85 percent). These numbers were, in general, higher than in our previous survey (see “Comparing Survey Results” below).

In other areas of critical thinking, responses were more mixed. Almost half of respondents, for example, reported only “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” seeking out people with different opinions to engage in discussion. Many also reported only “sometimes,” “rarely,” or “never” planning where (35 percent) or how (36 percent) to get information on a given topic.

These factors are tied closely together. Critical thinking skills have been challenged and devalued at many different levels of society. There is, therefore, no simple fix. Simply cleansing the internet of misinformation, for example, would not suddenly make us better thinkers. Improving critical thinking across society will take a many-pronged effort.

Comparing Survey Results

Several interesting details emerged in the comparison of results from this survey to our 2018 poll. First, a word of caution: there were some demographic differences in the respondents between the two surveys. This survey skewed a bit older: the average age was 47, as opposed to 36.5. In addition, more females responded this time: 57 percent versus 46 percent.

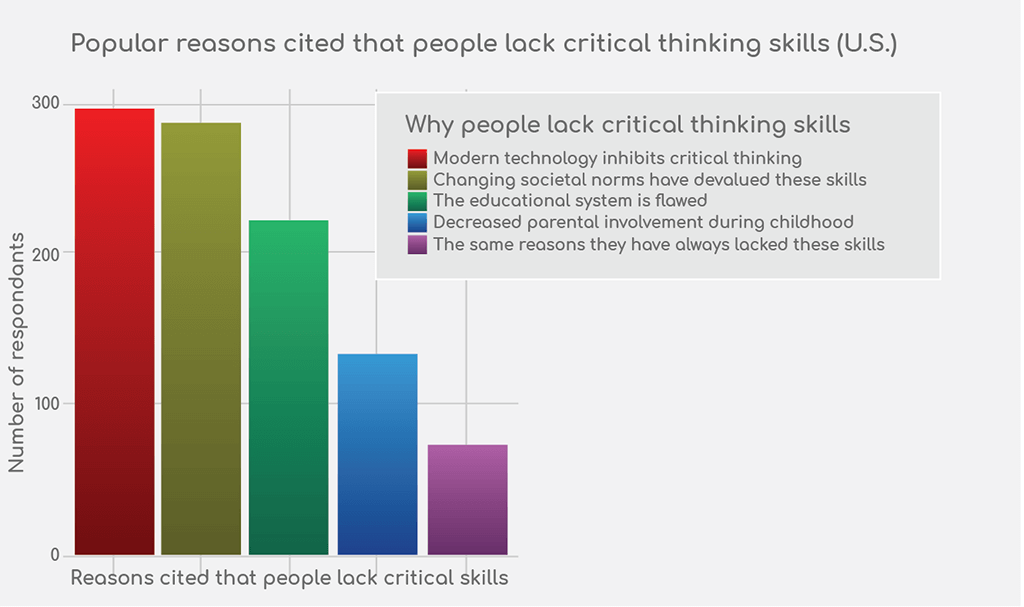

That said, there was a great deal of consistency between the surveys on participants’ general views of critical thinking. Belief in the importance of critical thinking remains high (94 percent versus 96 percent), as does belief that these skills are generally lacking in society at large. Blame, moreover, was spread to many of the same culprits. Slightly more participants blamed technology this time (29 versus 27 percent), while slightly fewer blamed the education system (22 versus 26 percent).

Respondents were also generally agreed on the importance of teaching critical thinking at all levels. Ninety-five percent thought critical thinking courses should be required at the K-12 level (slightly up from 92 percent); and 91 percent thought they should be required in college (slightly up from 90 percent). (These questions were framed slightly differently from year to year, which could have contributed to the small increases.)

One significant change came over the question of when it is appropriate to start developing critical thinking skills. In our first survey, less than 20 percent of respondents said that early childhood was the ideal time to develop critical thinking skills. This time, 43 percent of respondents did so. As discussed below, this is an encouraging development since research indicates that children become capable of learning how to think critically at a young age.

In one potentially discouraging difference between the two surveys, our most recent survey saw more respondents indicate that they did less critical thinking since high school (18 percent versus just 4 percent). But similar numbers of respondents indicated their critical thinking skills had deteriorated since high school (23 percent versus 21 percent).

Finally, encouraging points of comparison emerged in responses to questions about particular critical thinking activities. Our most recent survey saw a slight uptick in the number of respondents reporting engagement in activities like collaborating with others, planning on where to get information, seeking out the opinions of those they disagree with, keeping an open mind, and verifying information. (See Appendix 1: Data Tables.)

These results could reflect genuine differences from 2018, in either actual activity or respondents’ sense of the importance of these activities. But demographic differences in age and gender could also be responsible.

There is reason to believe, however, that demographic differences are not the main factor, since there is no evident correlation between gender and responses in either survey. Meanwhile, in our most recent survey older respondents reported doing these activities less frequently . Since this survey skewed older, it might have been anticipated that respondents would report doing these activities less. But the opposite is the case.

Findings From Teacher Survey

Teachers generally agree with general survey respondents about the importance of critical thinking. Ninety-four percent regard critical thinking as “extremely” or “very important.”

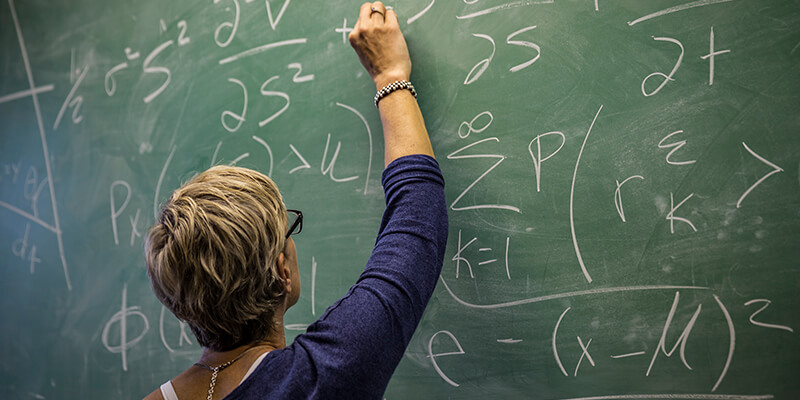

Teachers, like general survey participants, also share concerns that young people aren’t acquiring the critical thinking skills they need. They worry, in particular, about the impact of technology on their students’ critical thinking skills. In response to a question about how their school’s administration can help them teach critical thinking education more effectively, some teachers said updated technology (along with new textbooks and other materials) would help, but others thought laptops, tablets, and smartphones were inhibiting students’ critical thinking development.

This is an important point to clarify if we are to better integrate critical thinking into K-12 education. Research strongly suggests that critical thinking skills are best acquired in combination with basic facts in a particular subject area. The idea that critical thinking is a skill that can be effectively taught in isolation from basic facts is mistaken.

Another common misconception reflected in the teacher survey involves critical thinking and achievement. Although a majority of teachers (52 percent) thought all students benefited from critical thinking instruction, a significant percentage (35) said it primarily benefited high-ability students.

At Reboot, we believe that all students are capable of critical thinking and will benefit from critical thinking instruction. Critical thinking is, after all, just a refinement of everyday thinking, decision-making, and problem-solving. These are skills all students must have. The key is instilling in our young people both the habits and subject-area knowledge needed to facilitate the improvement and refinement of these skills.

Teachers need more support when it comes to critical thinking instruction. In the survey, educators repeatedly mentioned a lack of resources and updated professional development. In response to a question about how administrators could help teachers teach critical thinking more effectively, one teacher asked for “better tools and materials for teaching us how to teach these things.”

Others wanted more training, asking directly for additional support in terms of resources and professional training. One educator put it bluntly: “Provide extra professional development to give resources and training on how to do this in multiple disciplines.”

Media literacy is still not being taught as widely as it should be. Forty-four percent of teachers reported that media literacy courses are not offered at their schools, with just 31 percent reporting required media literacy courses.

This is despite the fact that teachers, in their open responses, recognized the importance of media literacy, with some suggesting it should be a graduation requirement. Many organizations and some governments, notably Finland’s , have recognized the media literacy deficit and taken action to address it, but the U.S. education system has been slow to act.

Thinking skills have been valuable in all places and at all times. But with the recent upheavals in communication, information, and media, particularly around the COVID-19 crisis, such skills are perhaps more important than ever.

Part of the issue is that the production of information has been democratized—no longer vetted by gatekeepers but generated by anyone who has an internet connection and something to say. This has undoubtedly had positive effects, as events and voices come to light that might have previously not emerged. The recording of George Floyd’s killing is one such example. But, at the same time, finding and verifying good information has become much more difficult.

Technological changes have also put financial pressures on so-called “legacy media” like newspapers and television stations, leading to sometimes precipitous drops in quality, less rigorous fact-checking (in the original sense of the term), and the blending of news reports and opinion pieces. The success of internet articles and videos is too often measured by clicks instead of quality. A stable business model for high-quality public interest journalism remains lacking. And, as biased information and propaganda fills gaps left by shrinking newsrooms, polarization worsens. (1)

Traditional and social media both play into our biases and needs for in-group approval. Online platforms have proven ideal venues for misinformation and manipulation. And distractions abound, damaging attention spans and the quality of debate.

Many hold this digital upheaval at least partially responsible for recent political upheavals around the world. Our media consumption habits increasingly reinforce biases and previously held beliefs, and expose us to only the worst and most inflammatory views from the other side. Demagogues and the simple, emotion-driven ideas they advance thrive in this environment of confusion, isolation, and sensationalism.

It’s not only our public discourse that suffers. Some studies have suggested that digital media may be partially responsible for rising rates of depression and other mood disorders among the young. (2)

Coping with this fast-paced, distraction-filled world in a healthy and productive manner requires better thinking and better habits of mind, but the online world itself tends to encourage the opposite. This is not to suggest our collective thinking skills were pristine before the internet came along, only that the internet presents challenges to our thinking that we have not seen before and have not yet proven able to meet.

There are some positive signs, with more attention and resources being devoted to neglected areas of education like civics and media literacy ; organizations trying to address internet-fueled polarization and extremism; and online tools being developed to counter fake news and flawed information.

But we also need to support the development of more general reasoning skills and habits: in other words, “critical thinking.”

Critical thinking has long been a staple of K-12 and college education, theoretically, at least, if not always in practice. But the concept can easily appear vague and merely rhetorical without definite ideas and practices attached to it.

When, for example, is the best age to teach critical thinking? What activities are appropriate? Should basic knowledge be acquired at the same time as critical thinking skills, or separately? Some of these questions remain difficult to answer, but research and practice have gone far in addressing others.

Part of the goal of our survey was to compare general attitudes about critical thinking education—both in the teaching profession and the general public—to what the best and most recent research suggests. If there is to be progress in the development of critical thinking skills across society, it requires not just learning how best to teach critical thinking but diffusing that knowledge widely, especially to parents and educators.

The surveys were distributed through Amazon’s MTurk Prime service.

For the general survey, respondents answered a series of questions about critical thinking, followed by a section that asked respondents to estimate how often they do certain things, such as consult more than one source when searching for information. The questions in the “personal habit” section appeared in a randomized order to reduce question ordering effects. Demographic questions appeared at the end of the survey.

For the teacher survey, respondents were all part of a teacher panel created by MTurk Prime. They also answered a series of questions on critical thinking, especially focused on the role of critical thinking in their classrooms. After that, respondents answered a series of questions about how they teach—these questions were also randomized to reduce question ordering effects. Finally, we asked questions related to the role of media literacy in their classrooms.

To maintain consistency with the prior survey and to explore relationships across time, many of the questions remained the same from 2018. In some cases, following best practices in questionnaire design , we revamped questions to improve clarity and increase the validity and reliability of the responses.

For all surveys, only completed responses coming from IP addresses located in the U.S. were analyzed. 1152 respondents completed the general survey; 499 teachers completed the teacher survey.