An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Wiley - PMC COVID-19 Collection

Students’ experience of online learning during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A province‐wide survey study

Lixiang yan.

1 Centre for Learning Analytics at Monash, Faculty of Information Technology, Monash University, Clayton VIC, Australia

Alexander Whitelock‐Wainwright

2 Portfolio of the Deputy Vice‐Chancellor (Education), Monash University, Melbourne VIC, Australia

Quanlong Guan

3 Department of Computer Science, Jinan University, Guangzhou China

Gangxin Wen

4 College of Cyber Security, Jinan University, Guangzhou China

Dragan Gašević

Guanliang chen, associated data.

The data is not openly available as it is restricted by the Chinese government.

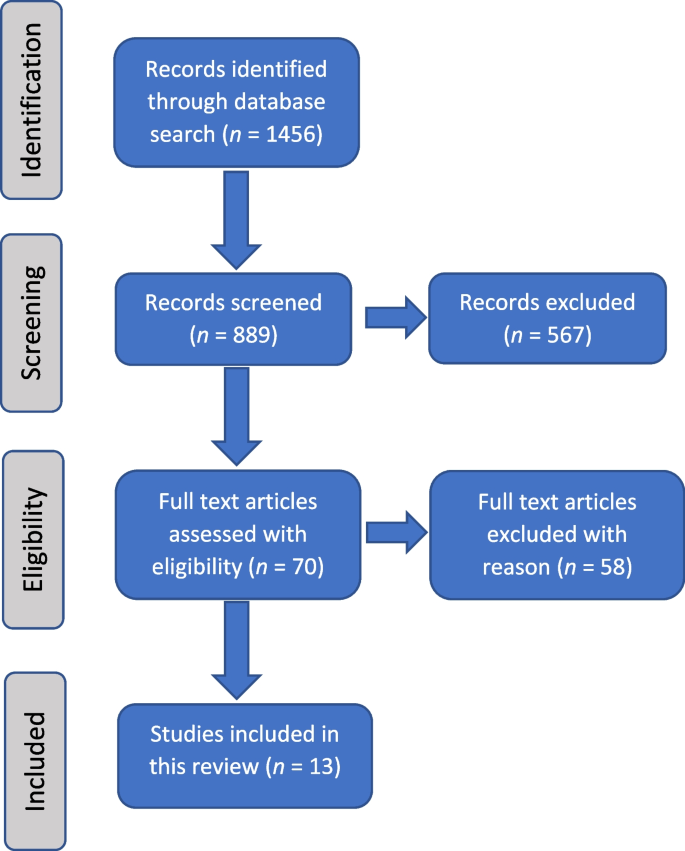

Online learning is currently adopted by educational institutions worldwide to provide students with ongoing education during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Even though online learning research has been advancing in uncovering student experiences in various settings (i.e., tertiary, adult, and professional education), very little progress has been achieved in understanding the experience of the K‐12 student population, especially when narrowed down to different school‐year segments (i.e., primary and secondary school students). This study explores how students at different stages of their K‐12 education reacted to the mandatory full‐time online learning during the COVID‐19 pandemic. For this purpose, we conducted a province‐wide survey study in which the online learning experience of 1,170,769 Chinese students was collected from the Guangdong Province of China. We performed cross‐tabulation and Chi‐square analysis to compare students’ online learning conditions, experiences, and expectations. Results from this survey study provide evidence that students’ online learning experiences are significantly different across school years. Foremost, policy implications were made to advise government authorises and schools on improving the delivery of online learning, and potential directions were identified for future research into K‐12 online learning.

Practitioner notes

What is already known about this topic

- Online learning has been widely adopted during the COVID‐19 pandemic to ensure the continuation of K‐12 education.

- Student success in K‐12 online education is substantially lower than in conventional schools.

- Students experienced various difficulties related to the delivery of online learning.

What this paper adds

- Provide empirical evidence for the online learning experience of students in different school years.

- Identify the different needs of students in primary, middle, and high school.

- Identify the challenges of delivering online learning to students of different age.

Implications for practice and/or policy

- Authority and schools need to provide sufficient technical support to students in online learning.

- The delivery of online learning needs to be customised for students in different school years.

INTRODUCTION

The ongoing COVID‐19 pandemic poses significant challenges to the global education system. By July 2020, the UN Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2020) reported nationwide school closure in 111 countries, affecting over 1.07 billion students, which is around 61% of the global student population. Traditional brick‐and‐mortar schools are forced to transform into full‐time virtual schools to provide students with ongoing education (Van Lancker & Parolin, 2020 ). Consequently, students must adapt to the transition from face‐to‐face learning to fully remote online learning, where synchronous video conferences, social media, and asynchronous discussion forums become their primary venues for knowledge construction and peer communication.

For K‐12 students, this sudden transition is problematic as they often lack prior online learning experience (Barbour & Reeves, 2009 ). Barbour and LaBonte ( 2017 ) estimated that even in countries where online learning is growing rapidly, such as USA and Canada, less than 10% of the K‐12 student population had prior experience with this format. Maladaptation to online learning could expose inexperienced students to various vulnerabilities, including decrements in academic performance (Molnar et al., 2019 ), feeling of isolation (Song et al., 2004 ), and lack of learning motivation (Muilenburg & Berge, 2005 ). Unfortunately, with confirmed cases continuing to rise each day, and new outbreaks occur on a global scale, full‐time online learning for most students could last longer than anticipated (World Health Organization, 2020 ). Even after the pandemic, the current mass adoption of online learning could have lasting impacts on the global education system, and potentially accelerate and expand the rapid growth of virtual schools on a global scale (Molnar et al., 2019 ). Thus, understanding students' learning conditions and their experiences of online learning during the COVID pandemic becomes imperative.

Emerging evidence on students’ online learning experience during the COVID‐19 pandemic has identified several major concerns, including issues with internet connection (Agung et al., 2020 ; Basuony et al., 2020 ), problems with IT equipment (Bączek et al., 2021 ; Niemi & Kousa, 2020 ), limited collaborative learning opportunities (Bączek et al., 2021 ; Yates et al., 2020 ), reduced learning motivation (Basuony et al., 2020 ; Niemi & Kousa, 2020 ; Yates et al., 2020 ), and increased learning burdens (Niemi & Kousa, 2020 ). Although these findings provided valuable insights about the issues students experienced during online learning, information about their learning conditions and future expectations were less mentioned. Such information could assist educational authorises and institutions to better comprehend students’ difficulties and potentially improve their online learning experience. Additionally, most of these recent studies were limited to higher education, except for Yates et al. ( 2020 ) and Niemi and Kousa’s ( 2020 ) studies on senior high school students. Empirical research targeting the full spectrum of K‐12students remain scarce. Therefore, to address these gaps, the current paper reports the findings of a large‐scale study that sought to explore K‐12 students’ online learning experience during the COVID‐19 pandemic in a provincial sample of over one million Chinese students. The findings of this study provide policy recommendations to educational institutions and authorities regarding the delivery of K‐12 online education.

LITERATURE REVIEW

Learning conditions and technologies.

Having stable access to the internet is critical to students’ learning experience during online learning. Berge ( 2005 ) expressed the concern of the divide in digital‐readiness, and the pedagogical approach between different countries could influence students’ online learning experience. Digital‐readiness is the availability and adoption of information technologies and infrastructures in a country. Western countries like America (3rd) scored significantly higher in digital‐readiness compared to Asian countries like China (54th; Cisco, 2019 ). Students from low digital‐readiness countries could experience additional technology‐related problems. Supporting evidence is emerging in recent studies conducted during the COVID‐19 pandemic. In Egypt's capital city, Basuony et al. ( 2020 ) found that only around 13.9%of the students experienced issues with their internet connection. Whereas more than two‐thirds of the students in rural Indonesia reported issues of unstable internet, insufficient internet data, and incompatible learning device (Agung et al., 2020 ).

Another influential factor for K‐12 students to adequately adapt to online learning is the accessibility of appropriate technological devices, especially having access to a desktop or a laptop (Barbour et al., 2018 ). However, it is unlikely for most of the students to satisfy this requirement. Even in higher education, around 76% of students reported having incompatible devices for online learning and only 15% of students used laptop for online learning, whereas around 85% of them used smartphone (Agung et al., 2020 ). It is very likely that K‐12 students also suffer from this availability issue as they depend on their parents to provide access to relevant learning devices.

Technical issues surrounding technological devices could also influence students’ experience in online learning. (Barbour & Reeves, 2009 ) argues that students need to have a high level of digital literacy to find and use relevant information and communicate with others through technological devices. Students lacking this ability could experience difficulties in online learning. Bączek et al. ( 2021 ) found that around 54% of the medical students experienced technical problems with IT equipment and this issue was more prevalent in students with lower years of tertiary education. Likewise, Niemi and Kousa ( 2020 ) also find that students in a Finish high school experienced increased amounts of technical problems during the examination period, which involved additional technical applications. These findings are concerning as young children and adolescent in primary and lower secondary school could be more vulnerable to these technical problems as they are less experienced with the technologies in online learning (Barbour & LaBonte, 2017 ). Therefore, it is essential to investigate the learning conditions and the related difficulties experienced by students in K‐12 education as the extend of effects on them remain underexplored.

Learning experience and interactions

Apart from the aforementioned issues, the extent of interaction and collaborative learning opportunities available in online learning could also influence students’ experience. The literature on online learning has long emphasised the role of effective interaction for the success of student learning. According to Muirhead and Juwah ( 2004 ), interaction is an event that can take the shape of any type of communication between two or subjects and objects. Specifically, the literature acknowledges the three typical forms of interactions (Moore, 1989 ): (i) student‐content, (ii) student‐student, and (iii) student‐teacher. Anderson ( 2003 ) posits, in the well‐known interaction equivalency theorem, learning experiences will not deteriorate if only one of the three interaction is of high quality, and the other two can be reduced or even eliminated. Quality interaction can be accomplished by across two dimensions: (i) structure—pedagogical means that guide student interaction with contents or other students and (ii) dialogue—communication that happens between students and teachers and among students. To be able to scale online learning and prevent the growth of teaching costs, the emphasise is typically on structure (i.e., pedagogy) that can promote effective student‐content and student‐student interaction. The role of technology and media is typically recognised as a way to amplify the effect of pedagogy (Lou et al., 2006 ). Novel technological innovations—for example learning analytics‐based personalised feedback at scale (Pardo et al., 2019 ) —can also empower teachers to promote their interaction with students.

Online education can lead to a sense of isolation, which can be detrimental to student success (McInnerney & Roberts, 2004 ). Therefore, integration of social interaction into pedagogy for online learning is essential, especially at the times when students do not actually know each other or have communication and collaboration skills underdeveloped (Garrison et al., 2010 ; Gašević et al., 2015 ). Unfortunately, existing evidence suggested that online learning delivery during the COVID‐19 pandemic often lacks interactivity and collaborative experiences (Bączek et al., 2021 ; Yates et al., 2020 ). Bączek et al., ( 2021 ) found that around half of the medical students reported reduced interaction with teachers, and only 4% of students think online learning classes are interactive. Likewise, Yates et al. ( 2020 )’s study in high school students also revealed that over half of the students preferred in‐class collaboration over online collaboration as they value the immediate support and the proximity to teachers and peers from in‐class interaction.

Learning expectations and age differentiation

Although these studies have provided valuable insights and stressed the need for more interactivity in online learning, K‐12 students in different school years could exhibit different expectations for the desired activities in online learning. Piaget's Cognitive Developmental Theory illustrated children's difficulties in understanding abstract and hypothetical concepts (Thomas, 2000 ). Primary school students will encounter many abstract concepts in their STEM education (Uttal & Cohen, 2012 ). In face‐to‐face learning, teachers provide constant guidance on students’ learning progress and can help them to understand difficult concepts. Unfortunately, the level of guidance significantly drops in online learning, and, in most cases, children have to face learning obstacles by themselves (Barbour, 2013 ). Additionally, lower primary school students may lack the metacognitive skills to use various online learning functions, maintain engagement in synchronous online learning, develop and execute self‐regulated learning plans, and engage in meaningful peer interactions during online learning (Barbour, 2013 ; Broadbent & Poon, 2015 ; Huffaker & Calvert, 2003; Wang et al., 2013 ). Thus, understanding these younger students’ expectations is imperative as delivering online learning to them in the same way as a virtual high school could hinder their learning experiences. For students with more matured metacognition, their expectations of online learning could be substantially different from younger students. Niemi et al.’s study ( 2020 ) with students in a Finish high school have found that students often reported heavy workload and fatigue during online learning. These issues could cause anxiety and reduce students’ learning motivation, which would have negative consequences on their emotional well‐being and academic performance (Niemi & Kousa, 2020 ; Yates et al., 2020 ), especially for senior students who are under the pressure of examinations. Consequently, their expectations of online learning could be orientated toward having additional learning support functions and materials. Likewise, they could also prefer having more opportunities for peer interactions as these interactions are beneficial to their emotional well‐being and learning performance (Gašević et al., 2013 ; Montague & Rinaldi, 2001 ). Therefore, it is imperative to investigate the differences between online learning expectations in students of different school years to suit their needs better.

Research questions

By building upon the aforementioned relevant works, this study aimed to contribute to the online learning literature with a comprehensive understanding of the online learning experience that K‐12 students had during the COVID‐19 pandemic period in China. Additionally, this study also aimed to provide a thorough discussion of what potential actions can be undertaken to improve online learning delivery. Formally, this study was guided by three research questions (RQs):

RQ1 . What learning conditions were experienced by students across 12 years of education during their online learning process in the pandemic period? RQ2 . What benefits and obstacles were perceived by students across 12 years of education when performing online learning? RQ3 . What expectations do students, across 12 years of education, have for future online learning practices ?

Participants

The total number of K‐12 students in the Guangdong Province of China is around 15 million. In China, students of Year 1–6, Year 7–9, and Year 10–12 are referred to as students of primary school, middle school, and high school, respectively. Typically, students in China start their study in primary school at the age of around six. At the end of their high‐school study, students have to take the National College Entrance Examination (NCEE; also known as Gaokao) to apply for tertiary education. The survey was administrated across the whole Guangdong Province, that is the survey was exposed to all of the 15 million K‐12 students, though it was not mandatory for those students to accomplish the survey. A total of 1,170,769 students completed the survey, which accounts for a response rate of 7.80%. After removing responses with missing values and responses submitted from the same IP address (duplicates), we had 1,048,575 valid responses, which accounts to about 7% of the total K‐12 students in the Guangdong Province. The number of students in different school years is shown in Figure 1 . Overall, students were evenly distributed across different school years, except for a smaller sample in students of Year 10–12.

The number of students in each school year

Survey design

The survey was designed collaboratively by multiple relevant parties. Firstly, three educational researchers working in colleges and universities and three educational practitioners working in the Department of Education in Guangdong Province were recruited to co‐design the survey. Then, the initial draft of the survey was sent to 30 teachers from different primary and secondary schools, whose feedback and suggestions were considered to improve the survey. The final survey consisted of a total of 20 questions, which, broadly, can be classified into four categories: demographic, behaviours, experiences, and expectations. Details are available in Appendix.

All K‐12 students in the Guangdong Province were made to have full‐time online learning from March 1, 2020 after the outbreak of COVID‐19 in January in China. A province‐level online learning platform was provided to all schools by the government. In addition to the learning platform, these schools can also use additional third‐party platforms to facilitate the teaching activities, for example WeChat and Dingding, which provide services similar to WhatsApp and Zoom. The main change for most teachers was that they had to shift the classroom‐based lectures to online lectures with the aid of web‐conferencing tools. Similarly, these teachers also needed to perform homework marking and have consultation sessions in an online manner.

The Department of Education in the Guangdong Province of China distributed the survey to all K‐12 schools in the province on March 21, 2020 and collected responses on March 26, 2020. Students could access and answer the survey anonymously by either scan the Quick Response code along with the survey or click the survey address link on their mobile device. The survey was administrated in a completely voluntary manner and no incentives were given to the participants. Ethical approval was granted by the Department of Education in the Guangdong Province. Parental approval was not required since the survey was entirely anonymous and facilitated by the regulating authority, which satisfies China's ethical process.

The original survey was in Chinese, which was later translated by two bilingual researchers and verified by an external translator who is certified by the Australian National Accreditation Authority of Translators and Interpreters. The original and translated survey questionnaires are available in Supporting Information. Given the limited space we have here and the fact that not every survey item is relevant to the RQs, the following items were chosen to answer the RQs: item Q3 (learning media) and Q11 (learning approaches) for RQ1, item Q13 (perceived obstacle) and Q19 (perceived benefits) for RQ2, and item Q19 (expected learning activities) for RQ3. Cross‐tabulation based approaches were used to analyse the collected data. To scrutinise whether the differences displayed by students of different school years were statistically significant, we performed Chi‐square tests and calculated the Cramer's V to assess the strengths of the association after chi‐square had determined significance.

For the analyses, students were segmented into four categories based on their school years, that is Year 1–3, Year 4–6, Year 7–9, and Year 10–12, to provide a clear understanding of the different experiences and needs that different students had for online learning. This segmentation was based on the educational structure of Chinese schools: elementary school (Year 1–6), middle school (Year 7–9), and high school (Year 10–12). Children in elementary school can further be segmented into junior (Year 1–3) or senior (Year 4–6) students because senior elementary students in China are facing more workloads compared to junior students due to the provincial Middle School Entry Examination at the end of Year 6.

Learning conditions—RQ1

Learning media.

The Chi‐square test showed significant association between school years and students’ reported usage of learning media, χ 2 (55, N = 1,853,952) = 46,675.38, p < 0.001. The Cramer's V is 0.07 ( df ∗ = 5), which indicates a small‐to‐medium effect according to Cohen’s ( 1988 ) guidelines. Based on Figure 2 , we observed that an average of up to 87.39% students used smartphones to perform online learning, while only 25.43% students used computer, which suggests that smartphones, with widespread availability in China (2020), have been adopted by students for online learning. As for the prevalence of the two media, we noticed that both smartphones ( χ 2 (3, N = 1,048,575) = 9,395.05, p < 0.001, Cramer's V = 0.10 ( df ∗ = 1)) and computers ( χ 2 (3, N = 1,048,575) = 11,025.58, p <.001, Cramer's V = 0.10 ( df ∗ = 1)) were more adopted by high‐school‐year (Year 7–12) than early‐school‐year students (Year 1–6), both with a small effect size. Besides, apparent discrepancies can be observed between the usages of TV and paper‐based materials across different school years, that is early‐school‐year students reported more TV usage ( χ 2 (3, N = 1,048,575) = 19,505.08, p <.001), with a small‐to‐medium effect size, Cramer's V = 0.14( df ∗ = 1). High‐school‐year students (especially Year 10–12) reported more usage of paper‐based materials ( χ 2 (3, N = 1,048,575) = 23,401.64, p < 0.001), with a small‐to‐medium effect size, Cramer's V = 0.15( df ∗ = 1).

Learning media used by students in online learning

Learning approaches

School years is also significantly associated with the different learning approaches students used to tackle difficult concepts during online learning, χ 2 (55, N = 2,383,751) = 58,030.74, p < 0.001. The strength of this association is weak to moderate as shown by the Cramer's V (0.07, df ∗ = 5; Cohen, 1988 ). When encountering problems related to difficult concepts, students typically chose to “solve independently by searching online” or “rewatch recorded lectures” instead of consulting to their teachers or peers (Figure 3 ). This is probably because, compared to classroom‐based education, it is relatively less convenient and more challenging for students to seek help from others when performing online learning. Besides, compared to high‐school‐year students, early‐school‐year students (Year 1–6), reported much less use of “solve independently by searching online” ( χ 2 (3, N = 1,048,575) = 48,100.15, p <.001), with a small‐to‐medium effect size, Cramer's V = 0.21 ( df ∗ = 1). Also, among those approaches of seeking help from others, significantly more high‐school‐year students preferred “communicating with other students” than early‐school‐year students ( χ 2 (3, N = 1,048,575) = 81,723.37, p < 0.001), with a medium effect size, Cramer's V = 0.28 ( df ∗ = 1).

Learning approaches used by students in online learning

Perceived benefits and obstacles—RQ2

Perceived benefits.

The association between school years and perceived benefits in online learning is statistically significant, χ 2 (66, N = 2,716,127) = 29,534.23, p < 0.001, and the Cramer's V (0.04, df ∗ = 6) indicates a small effect (Cohen, 1988 ). Unsurprisingly, benefits brought by the convenience of online learning are widely recognised by students across all school years (Figure 4 ), that is up to 75% of students reported that it is “more convenient to review course content” and 54% said that they “can learn anytime and anywhere” . Besides, we noticed that about 50% of early‐school‐year students appreciated the “access to courses delivered by famous teachers” and 40%–47% of high‐school‐year students indicated that online learning is “helpful to develop self‐regulation and autonomy” .

Perceived benefits of online learning reported by students

Perceived obstacles

The Chi‐square test shows a significant association between school years and students’ perceived obstacles in online learning, χ 2 (77, N = 2,699,003) = 31,987.56, p < 0.001. This association is relatively weak as shown by the Cramer's V (0.04, df ∗ = 7; Cohen, 1988 ). As shown in Figure 5 , the biggest obstacles encountered by up to 73% of students were the “eyestrain caused by long staring at screens” . Disengagement caused by nearby disturbance was reported by around 40% of students, especially those of Year 1–3 and 10–12. Technological‐wise, about 50% of students experienced poor Internet connection during their learning process, and around 20% of students reported the “confusion in setting up the platforms” across of school years.

Perceived obstacles of online learning reported by students

Expectations for future practices of online learning – RQ3

Online learning activities.

The association between school years and students’ expected online learning activities is significant, χ 2 (66, N = 2,416,093) = 38,784.81, p < 0.001. The Cramer's V is 0.05 ( df ∗ = 6) which suggests a small effect (Cohen, 1988 ). As shown in Figure 6 , the most expected activity for future online learning is “real‐time interaction with teachers” (55%), followed by “online group discussion and collaboration” (38%). We also observed that more early‐school‐year students expect reflective activities, such as “regular online practice examinations” ( χ 2 (3, N = 1,048,575) = 11,644.98, p < 0.001), with a small effect size, Cramer's V = 0.11 ( df ∗ = 1). In contrast, more high‐school‐year students expect “intelligent recommendation system …” ( χ 2 (3, N = 1,048,575) = 15,327.00, p < 0.001), with a small effect size, Cramer's V = 0.12 ( df ∗ = 1).

Students’ expected online learning activities

Regarding students’ learning conditions, substantial differences were observed in learning media, family dependency, and learning approaches adopted in online learning between students in different school years. The finding of more computer and smartphone usage in high‐school‐year than early‐school‐year students can probably be explained by that, with the growing abilities in utilising these media as well as the educational systems and tools which run on these media, high‐school‐year students tend to make better use of these media for online learning practices. Whereas, the differences in paper‐based materials may imply that high‐school‐year students in China have to accomplish a substantial amount of exercise, assignments, and exam papers to prepare for the National College Entrance Examination (NCEE), whose delivery was not entirely digitised due to the sudden transition to online learning. Meanwhile, high‐school‐year students may also have preferred using paper‐based materials for exam practice, as eventually, they would take their NCEE in the paper format. Therefore, these substantial differences in students’ usage of learning media should be addressed by customising the delivery method of online learning for different school years.

Other than these between‐age differences in learning media, the prevalence of smartphone in online learning resonates with Agung et al.’s ( 2020 ) finding on the issues surrounding the availability of compatible learning device. The prevalence of smartphone in K‐12 students is potentially problematic as the majority of the online learning platform and content is designed for computer‐based learning (Berge, 2005 ; Molnar et al., 2019 ). Whereas learning with smartphones has its own unique challenges. For example, Gikas and Grant ( 2013 ) discovered that students who learn with smartphone experienced frustration with the small screen‐size, especially when trying to type with the tiny keypad. Another challenge relates to the distraction of various social media applications. Although similar distractions exist in computer and web‐based social media, the level of popularity, especially in the young generation, are much higher in mobile‐based social media (Montag et al., 2018 ). In particular, the message notification function in smartphones could disengage students from learning activities and allure them to social media applications (Gikas & Grant, 2013 ). Given these challenges of learning with smartphones, more research efforts should be devoted to analysing students’ online learning behaviour in the setting of mobile learning to accommodate their needs better.

The differences in learning approaches, once again, illustrated that early‐school‐year students have different needs compared to high‐school‐year students. In particular, the low usage of the independent learning methods in early‐school‐year students may reflect their inability to engage in independent learning. Besides, the differences in help seeking behaviours demonstrated the distinctive needs for communication and interaction between different students, that is early‐school‐year students have a strong reliance on teachers and high‐school‐year students, who are equipped with stronger communication ability, are more inclined to interact with their peers. This finding implies that the design of online learning platforms should take students’ different needs into account. Thus, customisation is urgently needed for the delivery of online learning to different school years.

In terms of the perceived benefits and challenges of online learning, our results resonate with several previous findings. In particular, the benefits of convenience are in line with the flexibility advantages of online learning, which were mentioned in prior works (Appana, 2008 ; Bączek et al., 2021 ; Barbour, 2013 ; Basuony et al., 2020 ; Harvey et al., 2014 ). Early‐school‐year students’ higher appreciation in having “access to courses delivered by famous teachers” and lower appreciation in the independent learning skills developed through online learning are also in line with previous literature (Barbour, 2013 ; Harvey et al., 2014 ; Oliver et al., 2009 ). Again, these similar findings may indicate the strong reliance that early‐school‐year students place on teachers, while high‐school‐year students are more capable of adapting to online learning by developing independent learning skills.

Technology‐wise, students’ experience of poor internet connection and confusion in setting up online learning platforms are particularly concerning. The problem of poor internet connection corroborated the findings reported in prior studies (Agung et al., 2020 ; Barbour, 2013 ; Basuony et al., 2020 ; Berge, 2005 ; Rice, 2006 ), that is the access issue surrounded the digital divide as one of the main challenges of online learning. In the era of 4G and 5G networks, educational authorities and institutions that deliver online education could fall into the misconception of most students have a stable internet connection at home. The internet issue we observed is particularly vital to students’ online learning experience as most students prefer real‐time communications (Figure 6 ), which rely heavily on stable internet connection. Likewise, the finding of students’ confusion in technology is also consistent with prior studies (Bączek et al., 2021 ; Muilenburg & Berge, 2005 ; Niemi & Kousa, 2020 ; Song et al., 2004 ). Students who were unsuccessfully in setting up the online learning platforms could potentially experience declines in confidence and enthusiasm for online learning, which would cause a subsequent unpleasant learning experience. Therefore, both the readiness of internet infrastructure and student technical skills remain as the significant challenges for the mass‐adoption of online learning.

On the other hand, students’ experience of eyestrain from extended screen time provided empirical evidence to support Spitzer’s ( 2001 ) speculation about the potential ergonomic impact of online learning. This negative effect is potentially related to the prevalence of smartphone device and the limited screen size of these devices. This finding not only demonstrates the potential ergonomic issues that would be caused by smartphone‐based online learning but also resonates with the aforementioned necessity of different platforms and content designs for different students.

A less‐mentioned problem in previous studies on online learning experiences is the disengagement caused by nearby disturbance, especially in Year 1–3 and 10–12. It is likely that early‐school‐year students suffered from this problem because of their underdeveloped metacognitive skills to concentrate on online learning without teachers’ guidance. As for high‐school‐year students, the reasons behind their disengagement require further investigation in the future. Especially it would be worthwhile to scrutinise whether this type of disengagement is caused by the substantial amount of coursework they have to undertake and the subsequent a higher level of pressure and a lower level of concentration while learning.

Across age‐level differences are also apparent in terms of students’ expectations of online learning. Although, our results demonstrated students’ needs of gaining social interaction with others during online learning, findings (Bączek et al., 2021 ; Harvey et al., 2014 ; Kuo et al., 2014 ; Liu & Cavanaugh, 2012 ; Yates et al., 2020 ). This need manifested differently across school years, with early‐school‐year students preferring more teacher interactions and learning regulation support. Once again, this finding may imply that early‐school‐year students are inadequate in engaging with online learning without proper guidance from their teachers. Whereas, high‐school‐year students prefer more peer interactions and recommendation to learning resources. This expectation can probably be explained by the large amount of coursework exposed to them. Thus, high‐school‐year students need further guidance to help them better direct their learning efforts. These differences in students’ expectations for future practices could guide the customisation of online learning delivery.

Implications

As shown in our results, improving the delivery of online learning not only requires the efforts of policymakers but also depend on the actions of teachers and parents. The following sub‐sections will provide recommendations for relevant stakeholders and discuss their essential roles in supporting online education.

Technical support

The majority of the students has experienced technical problems during online learning, including the internet lagging and confusion in setting up the learning platforms. These problems with technology could impair students’ learning experience (Kauffman, 2015 ; Muilenburg & Berge, 2005 ). Educational authorities and schools should always provide a thorough guide and assistance for students who are experiencing technical problems with online learning platforms or other related tools. Early screening and detection could also assist schools and teachers to direct their efforts more effectively in helping students with low technology skills (Wilkinson et al., 2010 ). A potential identification method involves distributing age‐specific surveys that assess students’ Information and Communication Technology (ICT) skills at the beginning of online learning. For example, there are empirical validated ICT surveys available for both primary (Aesaert et al., 2014 ) and high school (Claro et al., 2012 ) students.

For students who had problems with internet lagging, the delivery of online learning should provide options that require fewer data and bandwidth. Lecture recording is the existing option but fails to address students’ need for real‐time interaction (Clark et al., 2015 ; Malik & Fatima, 2017 ). A potential alternative involves providing students with the option to learn with digital or physical textbooks and audio‐conferencing, instead of screen sharing and video‐conferencing. This approach significantly reduces the amount of data usage and lowers the requirement of bandwidth for students to engage in smooth online interactions (Cisco, 2018 ). It also requires little additional efforts from teachers as official textbooks are often available for each school year, and thus, they only need to guide students through the materials during audio‐conferencing. Educational authority can further support this approach by making digital textbooks available for teachers and students, especially those in financial hardship. However, the lack of visual and instructor presence could potentially reduce students’ attention, recall of information, and satisfaction in online learning (Wang & Antonenko, 2017 ). Therefore, further research is required to understand whether the combination of digital or physical textbooks and audio‐conferencing is appropriate for students with internet problems. Alternatively, suppose the local technological infrastructure is well developed. In that case, governments and schools can also collaborate with internet providers to issue data and bandwidth vouchers for students who are experiencing internet problems due to financial hardship.

For future adoption of online learning, policymakers should consider the readiness of the local internet infrastructure. This recommendation is particularly important for developing countries, like Bangladesh, where the majority of the students reported the lack of internet infrastructure (Ramij & Sultana, 2020 ). In such environments, online education may become infeasible, and alternative delivery method could be more appropriate, for example, the Telesecundaria program provides TV education for rural areas of Mexico (Calderoni, 1998 ).

Other than technical problems, choosing a suitable online learning platform is also vital for providing students with a better learning experience. Governments and schools should choose an online learning platform that is customised for smartphone‐based learning, as the majority of students could be using smartphones for online learning. This recommendation is highly relevant for situations where students are forced or involuntarily engaged in online learning, like during the COVID‐19 pandemic, as they might not have access to a personal computer (Molnar et al., 2019 ).

Customisation of delivery methods

Customising the delivery of online learning for students in different school years is the theme that appeared consistently across our findings. This customisation process is vital for making online learning an opportunity for students to develop independent learning skills, which could help prepare them for tertiary education and lifelong learning. However, the pedagogical design of K‐12 online learning programs should be differentiated from adult‐orientated programs as these programs are designed for independent learners, which is rarely the case for students in K‐12 education (Barbour & Reeves, 2009 ).

For early‐school‐year students, especially Year 1–3 students, providing them with sufficient guidance from both teachers and parents should be the priority as these students often lack the ability to monitor and reflect on learning progress. In particular, these students would prefer more real‐time interaction with teachers, tutoring from parents, and regular online practice examinations. These forms of guidance could help early‐school‐year students to cope with involuntary online learning, and potentially enhance their experience in future online learning. It should be noted that, early‐school‐year students demonstrated interest in intelligent monitoring and feedback systems for learning. Additional research is required to understand whether these young children are capable of understanding and using learning analytics that relay information on their learning progress. Similarly, future research should also investigate whether young children can communicate effectively through digital tools as potential inability could hinder student learning in online group activities. Therefore, the design of online learning for early‐school‐year students should focus less on independent learning but ensuring that students are learning effective under the guidance of teachers and parents.

In contrast, group learning and peer interaction are essential for older children and adolescents. The delivery of online learning for these students should focus on providing them with more opportunities to communicate with each other and engage in collaborative learning. Potential methods to achieve this goal involve assigning or encouraging students to form study groups (Lee et al., 2011 ), directing students to use social media for peer communication (Dabbagh & Kitsantas, 2012 ), and providing students with online group assignments (Bickle & Rucker, 2018 ).

Special attention should be paid to students enrolled in high schools. For high‐school‐year students, in particular, students in Year 10–12, we also recommend to provide them with sufficient access to paper‐based learning materials, such as revision booklet and practice exam papers, so they remain familiar with paper‐based examinations. This recommendation applies to any students who engage in online learning but has to take their final examination in paper format. It is also imperative to assist high‐school‐year students who are facing examinations to direct their learning efforts better. Teachers can fulfil this need by sharing useful learning resources on the learning management system, if it is available, or through social media groups. Alternatively, students are interested in intelligent recommendation systems for learning resources, which are emerging in the literature (Corbi & Solans, 2014 ; Shishehchi et al., 2010 ). These systems could provide personalised recommendations based on a series of evaluation on learners’ knowledge. Although it is infeasible for situations where the transformation to online learning happened rapidly (i.e., during the COVID‐19 pandemic), policymakers can consider embedding such systems in future online education.

Limitations

The current findings are limited to primary and secondary Chinese students who were involuntarily engaged in online learning during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Despite the large sample size, the population may not be representative as participants are all from a single province. Also, information about the quality of online learning platforms, teaching contents, and pedagogy approaches were missing because of the large scale of our study. It is likely that the infrastructures of online learning in China, such as learning platforms, instructional designs, and teachers’ knowledge about online pedagogy, were underprepared for the sudden transition. Thus, our findings may not represent the experience of students who voluntarily participated in well‐prepared online learning programs, in particular, the virtual school programs in America and Canada (Barbour & LaBonte, 2017 ; Molnar et al., 2019 ). Lastly, the survey was only evaluated and validated by teachers but not students. Therefore, students with the lowest reading comprehension levels might have a different understanding of the items’ meaning, especially terminologies that involve abstract contracts like self‐regulation and autonomy in item Q17.

In conclusion, we identified across‐year differences between primary and secondary school students’ online learning experience during the COVID‐19 pandemic. Several recommendations were made for the future practice and research of online learning in the K‐12 student population. First, educational authorities and schools should provide sufficient technical support to help students to overcome potential internet and technical problems, as well as choosing online learning platforms that have been customised for smartphones. Second, customising the online pedagogy design for students in different school years, in particular, focusing on providing sufficient guidance for young children, more online collaborative opportunity for older children and adolescent, and additional learning resource for senior students who are facing final examinations.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

There is no potential conflict of interest in this study.

ETHICS STATEMENT

The data are collected by the Department of Education of the Guangdong Province who also has the authority to approve research studies in K12 education in the province.

Supporting information

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work is supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (62077028, 61877029), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangdong (2020B0909030005, 2020B1212030003, 2020ZDZX3013, 2019B1515120010, 2018KTSCX016, 2019A050510024), the Science and Technology Planning Project of Guangzhou (201902010041), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (21617408, 21619404).

SURVEY ITEMS

Yan, L , Whitelock‐Wainwright, A , Guan, Q , Wen, G , Gašević, D , & Chen, G . Students’ experience of online learning during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A province‐wide survey study . Br J Educ Technol . 2021; 52 :2038–2057. 10.1111/bjet.13102 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

- Aesaert, K. , Van Nijlen, D. , Vanderlinde, R. , & van Braak, J. (2014). Direct measures of digital information processing and communication skills in primary education: Using item response theory for the development and validation of an ICT competence scale . Computers & Education , 76 , 168–181. 10.1016/j.compedu.2014.03.013 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Agung, A. S. N. , Surtikanti, M. W. , & Quinones, C. A. (2020). Students’ perception of online learning during COVID‐19 pandemic: A case study on the English students of STKIP Pamane Talino . SOSHUM: Jurnal Sosial Dan Humaniora , 10 ( 2 ), 225–235. 10.31940/soshum.v10i2.1316 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Anderson, T. (2003). Getting the mix right again: An updated and theoretical rationale for interaction . The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning , 4 ( 2 ). 10.19173/irrodl.v4i2.149 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Appana, S. (2008). A review of benefits and limitations of online learning in the context of the student, the instructor and the tenured faculty . International Journal on E‐learning , 7 ( 1 ), 5–22. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bączek, M. , Zagańczyk‐Bączek, M. , Szpringer, M. , Jaroszyński, A. , & Wożakowska‐Kapłon, B. (2021). Students’ perception of online learning during the COVID‐19 pandemic: A survey study of Polish medical students . Medicine , 100 ( 7 ), e24821. 10.1097/MD.0000000000024821 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Barbour, M. K. (2013). The landscape of k‐12 online learning: Examining what is known . Handbook of Distance Education , 3 , 574–593. [ Google Scholar ]

- Barbour, M. , Huerta, L. , & Miron, G. (2018). Virtual schools in the US: Case studies of policy, performance and research evidence. In Society for information technology & teacher education international conference (pp. 672–677). Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). [ Google Scholar ]

- Barbour, M. K. , & LaBonte, R. (2017). State of the nation: K‐12 e‐learning in Canada, 2017 edition . http://k12sotn.ca/wp‐content/uploads/2018/02/StateNation17.pdf [ Google Scholar ]

- Barbour, M. K. , & Reeves, T. C. (2009). The reality of virtual schools: A review of the literature . Computers & Education , 52 ( 2 ), 402–416. [ Google Scholar ]

- Basuony, M. A. K. , EmadEldeen, R. , Farghaly, M. , El‐Bassiouny, N. , & Mohamed, E. K. A. (2020). The factors affecting student satisfaction with online education during the COVID‐19 pandemic: An empirical study of an emerging Muslim country . Journal of Islamic Marketing . 10.1108/JIMA-09-2020-0301 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Berge, Z. L. (2005). Virtual schools: Planning for success . Teachers College Press, Columbia University. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bickle, M. C. , & Rucker, R. (2018). Student‐to‐student interaction: Humanizing the online classroom using technology and group assignments . Quarterly Review of Distance Education , 19 ( 1 ), 1–56. [ Google Scholar ]

- Broadbent, J. , & Poon, W. L. (2015). Self‐regulated learning strategies & academic achievement in online higher education learning environments: A systematic review . The Internet and Higher Education , 27 , 1–13. [ Google Scholar ]

- Calderoni, J. (1998). Telesecundaria: Using TV to bring education to rural Mexico (Tech. Rep.). The World Bank. [ Google Scholar ]

- Cisco . (2018). Bandwidth requirements for meetings with cisco Webex and collaboration meeting rooms white paper . http://dwz.date/dpbc [ Google Scholar ]

- Cisco . (2019). Cisco digital readiness 2019 . https://www.cisco.com/c/m/en_us/about/corporate‐social‐responsibility/research‐resources/digital‐readiness‐index.html#/ (Library Catalog: www.cisco.com). [ Google Scholar ]

- Clark, C. , Strudler, N. , & Grove, K. (2015). Comparing asynchronous and synchronous video vs. text based discussions in an online teacher education course . Online Learning , 19 ( 3 ), 48–69. [ Google Scholar ]

- Claro, M. , Preiss, D. D. , San Martín, E. , Jara, I. , Hinostroza, J. E. , Valenzuela, S. , Cortes, F. , & Nussbaum, M. (2012). Assessment of 21st century ICT skills in Chile: Test design and results from high school level students . Computers & Education , 59 ( 3 ), 1042–1053. 10.1016/j.compedu.2012.04.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences . Routledge Academic. [ Google Scholar ]

- Corbi, A. , & Solans, D. B. (2014). Review of current student‐monitoring techniques used in elearning‐focused recommender systems and learning analytics: The experience API & LIME model case study . IJIMAI , 2 ( 7 ), 44–52. [ Google Scholar ]

- Dabbagh, N. , & Kitsantas, A. (2012). Personal learning environments, social media, and self‐regulated learning: A natural formula for connecting formal and informal learning . The Internet and Higher Education , 15 ( 1 ), 3–8. 10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.06.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Garrison, D. R. , Cleveland‐Innes, M. , & Fung, T. S. (2010). Exploring causal relationships among teaching, cognitive and social presence: Student perceptions of the community of inquiry framework . The Internet and Higher Education , 13 ( 1–2 ), 31–36. 10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.002 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gašević, D. , Adesope, O. , Joksimović, S. , & Kovanović, V. (2015). Externally‐facilitated regulation scaffolding and role assignment to develop cognitive presence in asynchronous online discussions . The Internet and Higher Education , 24 , 53–65. 10.1016/j.iheduc.2014.09.006 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gašević, D. , Zouaq, A. , & Janzen, R. (2013). “Choose your classmates, your GPA is at stake!” The association of cross‐class social ties and academic performance . American Behavioral Scientist , 57 ( 10 ), 1460–1479. [ Google Scholar ]

- Gikas, J. , & Grant, M. M. (2013). Mobile computing devices in higher education: Student perspectives on learning with cellphones, smartphones & social media . The Internet and Higher Education , 19 , 18–26. [ Google Scholar ]

- Harvey, D. , Greer, D. , Basham, J. , & Hu, B. (2014). From the student perspective: Experiences of middle and high school students in online learning . American Journal of Distance Education , 28 ( 1 ), 14–26. 10.1080/08923647.2014.868739 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kauffman, H. (2015). A review of predictive factors of student success in and satisfaction with online learning . Research in Learning Technology , 23 . 10.3402/rlt.v23.26507 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kuo, Y.‐C. , Walker, A. E. , Belland, B. R. , Schroder, K. E. , & Kuo, Y.‐T. (2014). A case study of integrating interwise: Interaction, internet self‐efficacy, and satisfaction in synchronous online learning environments . International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning , 15 ( 1 ), 161–181. 10.19173/irrodl.v15i1.1664 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lee, S. J. , Srinivasan, S. , Trail, T. , Lewis, D. , & Lopez, S. (2011). Examining the relationship among student perception of support, course satisfaction, and learning outcomes in online learning . The Internet and Higher Education , 14 ( 3 ), 158–163. 10.1016/j.iheduc.2011.04.001 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Liu, F. , & Cavanaugh, C. (2012). Factors influencing student academic performance in online high school algebra . Open Learning: The Journal of Open, Distance and e‐Learning , 27 ( 2 ), 149–167. 10.1080/02680513.2012.678613 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Lou, Y. , Bernard, R. M. , & Abrami, P. C. (2006). Media and pedagogy in undergraduate distance education: A theory‐based meta‐analysis of empirical literature . Educational Technology Research and Development , 54 ( 2 ), 141–176. 10.1007/s11423-006-8252-x [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Malik, M. , & Fatima, G. (2017). E‐learning: Students’ perspectives about asynchronous and synchronous resources at higher education level . Bulletin of Education and Research , 39 ( 2 ), 183–195. [ Google Scholar ]

- McInnerney, J. M. , & Roberts, T. S. (2004). Online learning: Social interaction and the creation of a sense of community . Journal of Educational Technology & Society , 7 ( 3 ), 73–81. [ Google Scholar ]

- Molnar, A. , Miron, G. , Elgeberi, N. , Barbour, M. K. , Huerta, L. , Shafer, S. R. , & Rice, J. K. (2019). Virtual schools in the US 2019 . National Education Policy Center. [ Google Scholar ]

- Montague, M. , & Rinaldi, C. (2001). Classroom dynamics and children at risk: A followup . Learning Disability Quarterly , 24 ( 2 ), 75–83. [ Google Scholar ]

- Montag, C. , Becker, B. , & Gan, C. (2018). The multipurpose application Wechat: A review on recent research . Frontiers in Psychology , 9 , 2247. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02247 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Moore, M. G. (1989). Editorial: Three types of interaction . American Journal of Distance Education , 3 ( 2 ), 1–7. 10.1080/08923648909526659 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muilenburg, L. Y. , & Berge, Z. L. (2005). Student barriers to online learning: A factor analytic study . Distance Education , 26 ( 1 ), 29–48. 10.1080/01587910500081269 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Muirhead, B. , & Juwah, C. (2004). Interactivity in computer‐mediated college and university education: A recent review of the literature . Journal of Educational Technology & Society , 7 ( 1 ), 12–20. [ Google Scholar ]

- Niemi, H. M. , & Kousa, P. (2020). A case study of students’ and teachers’ perceptions in a finnish high school during the COVID pandemic . International Journal of Technology in Education and Science , 4 ( 4 ), 352–369. 10.46328/ijtes.v4i4.167 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Oliver, K. , Osborne, J. , & Brady, K. (2009). What are secondary students’ expectations for teachers in virtual school environments? Distance Education , 30 ( 1 ), 23–45. 10.1080/01587910902845923 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pardo, A. , Jovanovic, J. , Dawson, S. , Gašević, D. , & Mirriahi, N. (2019). Using learning analytics to scale the provision of personalised feedback . British Journal of Educational Technology , 50 ( 1 ), 128–138. 10.1111/bjet.12592 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ramij, M. , & Sultana, A. (2020). Preparedness of online classes in developing countries amid covid‐19 outbreak: A perspective from Bangladesh. Afrin, Preparedness of Online Classes in Developing Countries amid COVID‐19 Outbreak: A Perspective from Bangladesh (June 29, 2020) .

- Rice, K. L. (2006). A comprehensive look at distance education in the k–12 context . Journal of Research on Technology in Education , 38 ( 4 ), 425–448. 10.1080/15391523.2006.10782468 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Shishehchi, S. , Banihashem, S. Y. , & Zin, N. A. M. (2010). A proposed semantic recommendation system for elearning: A rule and ontology based e‐learning recommendation system. In 2010 international symposium on information technology (Vol. 1, pp. 1–5).

- Song, L. , Singleton, E. S. , Hill, J. R. , & Koh, M. H. (2004). Improving online learning: Student perceptions of useful and challenging characteristics . The Internet and Higher Education , 7 ( 1 ), 59–70. 10.1016/j.iheduc.2003.11.003 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Spitzer, D. R. (2001). Don’t forget the high‐touch with the high‐tech in distance learning . Educational Technology , 41 ( 2 ), 51–55. [ Google Scholar ]

- Thomas, R. M. (2000). Comparing theories of child development. Wadsworth/Thomson Learning. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2020, March). Education: From disruption to recovery . https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse (Library Catalog: en.unesco.org)

- Uttal, D. H. , & Cohen, C. A. (2012). Spatial thinking and stem education: When, why, and how? In Psychology of learning and motivation (Vol. 57 , pp. 147–181). Elsevier. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Lancker, W. , & Parolin, Z. (2020). Covid‐19, school closures, and child poverty: A social crisis in the making . The Lancet Public Health , 5 ( 5 ), e243–e244. 10.1016/S2468-2667(20)30084-0 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang, C.‐H. , Shannon, D. M. , & Ross, M. E. (2013). Students’ characteristics, self‐regulated learning, technology self‐efficacy, and course outcomes in online learning . Distance Education , 34 ( 3 ), 302–323. 10.1080/01587919.2013.835779 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wang, J. , & Antonenko, P. D. (2017). Instructor presence in instructional video: Effects on visual attention, recall, and perceived learning . Computers in Human Behavior , 71 , 79–89. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.01.049 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Wilkinson, A. , Roberts, J. , & While, A. E. (2010). Construction of an instrument to measure student information and communication technology skills, experience and attitudes to e‐learning . Computers in Human Behavior , 26 ( 6 ), 1369–1376. 10.1016/j.chb.2010.04.010 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- World Health Organization . (2020, July). Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID‐19): Situation Report‐164 (Situation Report No. 164). https://www.who.int/docs/default‐source/coronaviruse/situation‐reports/20200702‐covid‐19‐sitrep‐164.pdf?sfvrsn$=$ac074f58$_$2

- Yates, A. , Starkey, L. , Egerton, B. , & Flueggen, F. (2020). High school students’ experience of online learning during Covid‐19: The influence of technology and pedagogy . Technology, Pedagogy and Education , 9 , 1–15. 10.1080/1475939X.2020.1854337 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Open access

- Published: 16 December 2021

Do our children learn enough in Sky Class? A case study: online learning in Chinese primary schools in the COVID era March to May 2020

- Lina Zhao ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5962-1475 1 ,

- Peter Thomas 1 &

- Lingling Zhang 2

Smart Learning Environments volume 8 , Article number: 35 ( 2021 ) Cite this article

3951 Accesses

3 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

All human being’s ways of living, working and studying were significantly impacted by the Covid-19 in 2020. In China, the Ministry of Education reacted fast in ensuring that primary school students could learn online at home by promoting the Sky Class program from February 2020. Educators, parents, and students all faced the challenges of adapting to new online teaching and learning environments. In this small-scale case study, Sky Class’s content and the participants’ experiences, will be presented. Four primary school teachers and five primary school students and their parents participated in three-rounds of interviews sharing their perspectives and experiences of online learning. The study showed that the students gained more parental support and that they benefited from using multimedia functions, like replay, in their Sky Classes. However, the majority of participants reported that the students learnt less. By mapping the learning activities and themes from Sky Class against Cope and Kalantzis’ e-learning ecologies, our study found that only ubiquitous learning and multimodal meaning were achieved. We suggest the reason may be that high cognitive learning was not achieved due to less teachers’ supervision, lack of interaction, delayed feedback, shorter learning times and communication. In conclusion, innovative pedagogies, which can foster different types of learning from the e-learning ecologies may overcome the negative aspects reported about Sky Class. Further research is required for implementing online technology as a catalyst for educational change.

Introduction

The Chinese government reacted fast both in terms of controlling the pandemic and in continuing fundamental education nationally by promoting Sky Class programs. At 2 am on 23 January 2020, the central government of China issued a notice to start the “Wuhan Lockdown” to stop the outbreak of the coronavirus disease (Lockdowns rise, 2020 ). From 10 am, schools, companies, and all public transport, including buses, railways, flights, and ferry services were suspended. Four days after the Wuhan lockdown, the Ministry of Education directed authorities to shut down all schools nationally to prevent the spread of Covid-19 (Ministry of Education of People’s Republic of China, 2020b ). The Sky class program of K-12 was developed eighteen days after the Wuhan lockdown. Primary schools which were thought of as the last field in education to be intruded on by online or distance learning, now had to accept this new teaching and learning form to cope with home quarantine and social distance policies.

This small-scale designed descriptive case study illustrates what Sky Class looked like, and the participants reactions to the use of online technology for meaningful learning in primary school sectors. The themes that were developed from interview data will address the following questions:

Main research question: Did Chinese primary school students gain adequate learning through Sky Class program?

Sub-question 1: What does a sky class look like?

Sub-question 2: What were teachers, students, and their parents’ perceptions towards participating in online learning at the primary school level? Challenges and opportunities?

Children and online learning

Online learning is defined as the implementation of teaching and learning practices in an online environment. It is a form of distance education, as learning occurs through the internet synchronously or asynchronously where students can learn collaboratively with their teachers and peers or independently by themselves regardless of time and space (Singh & Thurman, 2019 ; Yilmaz, 2019 ). Online learning allows both learners and teachers, who cannot attend a school, to learn due to Covid-19 social restrictions, to access education and educational information from different locations.

Online learning has grown fast during the past decade in many countries due to its advantages, resulting in educational change that shifts learners from physical face-to-face classrooms to virtual classrooms in universities (Aldhafeeri & Khan, 2016 ). First of all, online learning provides a flexible learning environment for students regardless of their physical location and availability which increased participation rates (Kim, 2020 ; Yilmaz, 2019 ). Secondly, online education offered a lower cost option for both education organization and students compared to in-person classes (Khurana, 2016 ; Kim, 2020 ; Yilmaz, 2019 ). In addition, many young children have been initiated into using digital technologies in their home lives so that the transition to engage in online learning activities is enhanced (Yelland, 2006 ).

However, online learning has limitations as many programs failed to provide the environment that engages students via active communication and social interaction (O'Doherty et al., 2018 ). Moreover, negative issues such as social isolation, lack of interaction and participation, and delayed feedback were raised in evaluation of online learning programs (Khurana, 2016 ). There are also limitations in implementing online technologies with young children for learning purposes. The increasing time that children spend in front of the screen might negatively impact their cognitive and physical development (Cordes & Miller, 2004 ; House, 2012 ). It is argued that children need to physically interact with their environments, for instance, it is important for them to engage in hands-on activities and physical play (House, 2012 ), as thinking develops from experience with concrete materials (a developmental perspective). This is because concrete materials in natural settings allows young children to be actively interactive (Cordes & Miller, 2000 ; Elkind, 2007 ). Online learning may not provide sufficient opportunities for young children to interact with physical objects through hands-on activities and physical play.

Another limitation to be considered is that young children’s readiness for participation in online learning is limited by their lack of abilities to access and use online learning systems effectively (Wedenoja, 2020 ). Moreover, adult supervision is required when young children participate in online learning and other types of online activities, therefore, adult availability and involvement also impacts young children’s online learning experiences (Kim, 2020 ; Youn et al., 2012 ). Nevertheless, with the unexpected crisis of Covid-19, the primary school teachers and students had to adopt online learning where “school and home’s spaces and times are mixed up” (Malta Campos & Vieira, 2021 , p. 137).

Although, online learning or distance learning have been seen as viable alternative practices in the Covid-19 period, there is a lack of research exploring the implementation of online technologies in the primary school settings (Ching-Ting et al., 2014 ; Dong et al., 2020 ; Kerckaert et al., 2015 ). This study will help fill this gap by illustrating a full picture of online learning practices with young learners in China and examining Chinese primary students’ online learning experiences and their teachers, and parents’ perspectives towards online learning during the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020.

This program utilised the case study method to collect and analyse the data of implementing online technology to support young students’ home learning during the Covid-19 quarantine in China. A case study suited the need to explore and examine “a contemporary phenomenon within its real-life, especially when the boundaries between a phenomenon and context are not clear and the researcher has little control over the phenomenon and context” (Yin, 2013 , p. 13), by providing deep understanding, rich details and insights into participants’ experiences and perspectives (Billington, 2016 ).

Participants

In this study, we invited participants who were currently employed as primary school teachers (teaching any subjects), and currently enrolled as primary school students (aged 6–13) and their parents who participated in Sky Class program for three-round interviews. A recruitment advertisement was posted on the WeChat social media circle, 46 adults participants showed their interests in participating the study. After a pilot interview of 46 teachers and parents, four teachers (see Table 1 ) who participated in recording sky class videos and live streaming class; and five families (see Table 2 ) whose children participated in the whole sky class program from the primary school sector were selected for interviews. The selected participants were considered to be the representative of the Sky Class program. One family from Shanghai only agreed to provide the Sky Class timetable from their children’s school. The rest of the participants were from Wuhan, Hohhot, Qingdao, Xi’an, and Zhejiang (see Tables 1 , 2 ).

Data collection

Adults were initially interviewed for 30–50 min., and primary school students for 10–20 min. using sets of semi-open questions. Then, in the second and third round interviews (10–30 min.), they answered researcher’s follow up questions. All the interviews were conducted in Mandarin through video chat using the WeChat application and were recorded using the iPhone’s Voice Memos with password protection. Other digitalised data included online learning schedules, screenshots of applications and digital copies of online learning materials collected from the participants as well.

Parents’ consents were needed in this case study as the participant children were aged under 16. Moreover, one guardian was required to accompany their child in the interview to ensure that young children’s identities and rights were protected. All the participants’ identities were protected using anonymities. Any personal identifying information was not recorded, and accidental mentions were delated. Any data or information that participants wanted deleted were removed.

Data analysis

The interviewed teachers, students and parents shared their perspectives, experience and stories of participating in Sky Class. Their interview data was put through an open coding method in the first-round analysis to capture the descriptive segments to address the sub-research question of what a sky class looked like. Then, during the second-round coding, the useful segments were further categorised into sub-themes as “lacking self-discipline”, “lacking interactions”, “lacking immediately feedback”, “short learning time”, “parents support” and “replay function” to address the sub-question of what the participants’ experience of and perceptions toward primary school students’ participation in online learning. These analyses indicated that in general, the participants had feelings of dissatisfaction towards the Sky Class; and concern that the primary school students might not engage in learning online effectively. They further concluded that the Sky Class could not replace physical classes at the primary school level. However, Sky Class has opportunities to be utilised as supplementary activities for physical classes enhancing young learner’s learning experiences after the pandemic.

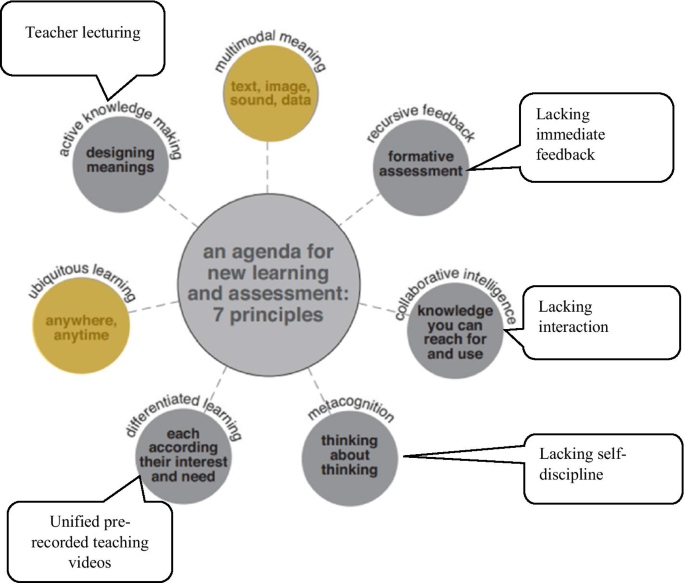

e-Learning ecologies and 7-affordences

The e-learning ecologies model and its e-affordances were utilised to assess the effectiveness of implementing online technology in Sky Class to see if new learning was promoted (Cope & Kalantzis, 2017 ). E-learning ecologies illustrates the possible innovative pedagogy patterns that can be designed for promoting new learning with digital technologies. Seven affordances were developed to demonstrate what new learning looks like with innovative and effective implementation pedagogies.

The annotated chart (see Fig. 1 ) was developed after examining the described learning activities and the resultant themes in the Sky Class to illustrate which affordances were addressed in the e-learning ecologies. We could only identify two affordances—ubiquitous learning and multimodal meaning—as the students were provided a wide range of digital technologies for accessing various multimedia resources such as teaching videos and live streaming classes (yellow-coloured circles in the Fig. 1 ). The rest of the affordances were hardly evidenced in our data. This showed that the innovative pedagogies that promoted independent, collaborative, critical, creative learning were missing in Sky Class online learning practices.

Mapping Sky Class learning activities and themes in e-learning ecologies (Cope & Kalantzis, 2017 , p 14)

On 12th February 2020, the Ministry of Education officially issued a notice promoting a policy of “suspending classes without stopping learning” which encouraged all schools to provide the online learning programs called Sky Class to their students to learn from home (Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, 2020a ; Zhang et al., 2020 , XinHua News, 2020 ).

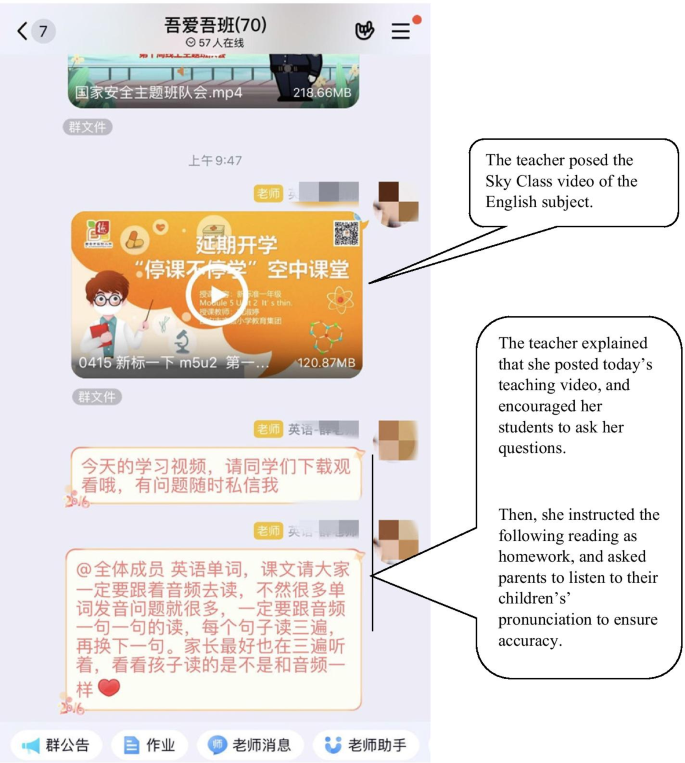

Based on our interview data, the Sky Class programs from the six regions are similar and mainly include asynchronous pre-recorded video teaching and synchronous live student Q&A torturing. The regional education departments gathered groups of teachers to develop sets teaching videos in literacy, numeracy and English for asynchronous online learning practices for their regional primary schools. The students can watch these pre-recorded teaching videos via TV and school websites daily based on their own schedules. Their classroom teachers also posted these videos files in their virtual classes that were established on WeChat or QQ program (see Fig. 2 ). Synchronous online leaning practices were promoted by each school from the six regions using student Q&A sessions which were live streaming teaching practices using Reng Reng Tong or the Teng Xun Class applications as a part of their regional Sky Class a few months after the Wuhan lockdown. All these practises ensured that students were able to access to sky classes by different devices based on their availabilities which indicated that ubiquitous learning from e-learning ecologies was successfully addressed in the Sky Class program.

A screen shot of a participant teacher posting a Sky Class video and homework in her class QQ group chat

However, in Hohhot region, the students from Year 3 and upper were required to attend the Sky Class. The students from Year 1–2 were still on holiday, and their major learning activities were finishing their holiday homework which was assigned by their classroom teachers in the last term of 2019.

The main form of the teaching videos for Sky Class are similar from the six regions according to our interview data, as they were PowerPoint slide shows (PPT) with teachers’ voices. More engaging teaching videos were produced a month later (from April 2020) by including teachers’ live images, cartons and 3D features, as the teachers received technique support and advice on recording and editing the videos. The camera function from the students’ side was not enabled in these sky classes at all. The students could participate in live streaming sky classes in some degree via microphone or chat box, to ask or answer questions synchronously. However, most of time they were passively involved in sky classes, as they just watched the screen silently. The teachers were still focused on orally explaining the teaching content in either recorded videos or live streaming classes which showed that the Chinese pedagogy of “teacher-centred lecturing” heavily impacted teachers’ practices on the Sky Class, indicating that the elements of active knowledge making and differentiated learning were not strongly reflected.

The classroom teachers assigned the homework based on the learning intentions of each day’s Sky Class teaching videos on their virtual class (see Fig. 3 ). The students still used pen and paper to work on their tasks first. After they finished their work, they needed to photocopy their work and send them back to their teachers though virtual class portals with their parents’ assistance. The teacher marked these digital copies and provided the feedback on their virtual classes on smartphones or computers.

A screen shot of a participant teacher marking students’ homework digitally in Ding Ding application

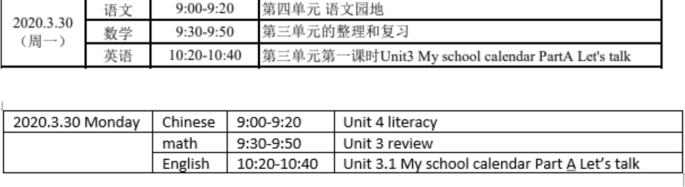

By examining the timetables of the Sky Classes from the six regions, literacy, numeracy and English were the main focus and delivered in the morning session which was similar to the physical school’s timetables (see Figs. 4 , 5 ). However, the total learning hours was decreased in Sky Class timetables compared to the physical school class timetable.

The sky class timetable in Wuhan region in April

The sky class timetable in Hohhot region in March

Each teaching video was only 20–30 min. long (45 min. each physical class) based on guidelines from the Ministry of Education that the teaching videos should not be too long for primary school students in terms of protecting their eye development and reducing the risk of short sightedness (Ministry of Education of People’s Republic of China, 2020a ). Longer breaks (30–60 min.) between each sky class and one two-hour lunch break for a day were required by the Ministry of Education (Ministry of Education of People’s Republic of China, 2020a , 2020c ). These requirements on the schedule of sky classes reduced actual learning time from 4–4.7 hr. per weekday in physical schools to 0.67–2.75 hr. online.

The participants also reported that the learning hours were shorter than the traditional school classes, and that they were concerned about shorter learning hours which might negatively impact young students learning. Student Yao said: “ Each class is short, so we might not learn that much .” Teacher Xue reported that the poor quality of her students’ homework indicated that the students did not spend enough time on studying English. The participant parents were also concerned that their children could not absorb knowledge and information taught in the Sky Class due to such short learning times which might cause children to be left behind. Parent Zhu reported:

The learning time is obviously short. At school, they have 4 classes in the morning, and 3 classes in the afternoon. At home, 40 minutes in total for a sky class in a day. I do not think they can understand all the taught knowledge thoroughly in such a short time.