Social Psychology - Science topic

- asked a question related to Social Psychology

- 28 Aug 2024

- 2 Sept 2024

- 0 Recommendations

- 16 Jul 2024

- 45 Recommendations

- 23 Jun 2024

- 24 Jun 2024

- 4 Recommendations

- Understanding Human Behavior: Psychology delves into the complexities of human behavior, cognition, emotions, and motivations. In conflict situations, understanding these aspects can provide insights into why conflicts arise, how they escalate, and what drives individuals or groups to engage in violent or peaceful actions.

- Conflict Resolution: Psychology offers techniques and strategies for conflict resolution and mediation. By understanding the psychological factors contributing to conflicts, peace studies can develop more effective approaches to negotiate and resolve conflicts, promote reconciliation, and build sustainable peace.

- Trauma and Healing: Psychology plays a crucial role in addressing trauma and promoting healing in post-conflict societies. It helps in understanding the psychological impact of violence, displacement, and loss on individuals and communities, guiding interventions for psychological well-being and resilience building.

- Group Dynamics and Identity: Psychology studies group dynamics, social identity, and intergroup relations, which are central to understanding conflicts based on ethnicity, religion, nationality, or ideology. This understanding can inform strategies for fostering intergroup dialogue, promoting tolerance, and preventing conflicts rooted in identity differences.

- Behavioral Change and Peacebuilding: Psychology offers insights into behavioral change theories and techniques, which are essential for designing effective peacebuilding interventions. It helps in addressing issues like prejudice, discrimination, and radicalization by targeting attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors that contribute to conflict.

- 9 Recommendations

- 14 Recommendations

- 18 May 2024

- 1 Recommendation

- 22 Mar 2024

- Any books or ways can be recommended for self-learning?

- Any test or exam which I can take so as to prove my knowledge of psychology and statistics?

- Are there any academic forum or journal that can help me to get the updated news and ideas in psychology?

- 3 Recommendations

- 30 Mar 2024

- 28 Feb 2024

- 6 Recommendations

- 17 Feb 2024

- 26 Dec 2023

- 26 Jan 2024

- 25 Oct 2018

- DISCUSSION_D.Prokopowicz_.Does corporate social responsibility develop...social market economi es.jpg 225 kB

- 21 Jan 2024

- 15 Recommendations

- 24 Oct 2023

- 16 Nov 2023

- 25 Oct 2023

- 26 Oct 2023

- 15 Oct 2023

- 17 Oct 2023

- 25 Jun 2014

- 14 Oct 2023

- 192 Recommendations

- 14 Apr 2023

- 23 Jul 2023

- 10 Recommendations

- 12 Jun 2023

- 12 Jan 2011

- 22 May 2023

- 15 May 2023

- 8 Recommendations

- 23 Mar 2023

- 14 Dec 2022

- 14 Oct 2022

- 17 Oct 2022

- 28 Dec 2018

- QUESTIONS - Big Data_Important Topics 20 21.jpg 242 kB

- 20 Aug 2022

- ....RESEARCH TOPIC_D.Prokopowicz_The SARS-CoV-2 (Covid-19) coronavirus pandemic has forced increased internetisation.. ...jpg 283 kB

- 90 Recommendations

- 23 May 2020

- 14 Aug 2022

- 49 Recommendations

- 30 Jul 2022

- 20 Jul 2022

- 24 Jul 2022

- 1-s2.0-S0165178115307137-ma in.pdf 401 kB

- 48 Recommendations

- 12 Apr 2017

- 28 Jun 2022

- 19 Jun 2022

- 26 Dec 2021

- 30 Recommendations

- 25 Jun 2020

- 19 May 2022

- 10 Jun 2020

- 12 May 2022

- 18 Apr 2022

- 25 Apr 2022

- 18 Recommendations

- 25 Jan 2022

- 26 Jan 2022

- 30 Dec 2021

- 31 Dec 2021

- DISCUSSION_D.Prokopowicz_...Will the social aspects of interpersonal contacts..barrier...creation of electronic banks without staff 2 x.jpg 239 kB

- 168 Recommendations

- 25 Apr 2021

- 13 Oct 2021

- 26 Sept 2021

- 24 Sept 2021

- 210 Recommendations

- 31 May 2021

- 180 Recommendations

- 17 Jul 2021

- 300 Recommendations

- 29 Jul 2021

- 285 Recommendations

- 20 Sept 2021

- 22 Sept 2021

- 19 Dec 2018

- 17 Sept 2021

- 5 Recommendations

- 29 Aug 2021

- 16 Sept 2021

- 16 Recommendations

- 14 Oct 2014

- 11 Sept 2021

- 26 Dec 2020

- 5 Sept 2021

- 330 Recommendations

- 11 Aug 2021

- 18 Aug 2021

- 24 Recommendations

- 2 Recommendations

- 23 Jun 2021

- 30 Jul 2021

- Especial Experiencia ( 2).pdf 689 kB

- 21 Sept 2018

- DISCUSSION_D.Prokopowicz_.Can economic news in the media influence...psychology...investor behavior...capital marke ts.jpg 268 kB

- 25 Dec 2020

- 30 May 2021

- 2.jpg 35.4 kB

- 420 Recommendations

- 23 May 2021

- 26 May 2021

- 13 May 2021

- 14 May 2021

- 26 Recommendations

- Screenshot 2021-05-05 at 6.03.11 PM.png 10.9 kB

- 11 Apr 2020

- Are there any other theories that distinguish between internal and external perspectives/aspects of identity?

- Any info or comments on this distinction would be most welcome.

- 35 Recommendations

- 22 Mar 2021

- 30 Apr 2021

- 12 Recommendations

- 27 Apr 2021

- 21 Apr 2021

- 18 Nov 2018

- 16 Apr 2021

- 10 Apr 2021

- 11 May 2020

- DISCUSSION_D.Prokopowicz_.Are you superstitious can a scientist be superstitious 1 x.jpg 296 kB

- 345 Recommendations

- 28 Nov 2020

- 23 Feb 2021

- 10 Feb 2021

- 11 Feb 2021

- 105 Recommendations

- 19 Jan 2021

- 22 Jan 2021

- 25 Recommendations

- 30 Dec 2020

- 60 Recommendations

- 24 Dec 2020

- 36 Recommendations

- Iyer, G. R., Blut, M., Xiao, S. H., & Grewal, D. (2020). Impulse buying: a meta-analytic review. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science , 48 (3), 384-404.

- Amos, C., Holmes, G. R., & Keneson, W. C. (2014). A meta-analysis of consumer impulse buying. Journal of Retailing and Consumer Services , 21 (2), 86-97.

- 84 Recommendations

- 16 Dec 2020

- 13 Dec 2020

- 5e - Schneider_2302_Chapter_8_ma in.pdf 560 kB

- 72 Recommendations

- 11 Dec 2020

- 27 Nov 2020

- 20 Recommendations

- 26 Nov 2020

- 30 Oct 2020

- 26 Feb 2010

- 17 Nov 2020

- 13 Nov 2020

- 15 Nov 2020

- 12 Oct 2020

- 19 Oct 2020

- 22 Recommendations

- 15 Sept 2020

- 15 Oct 2020

- 120 Recommendations

- 21 Sept 2020

- 27 Sept 2020

- 16 Mar 2015

- 24 Sept 2020

- 21 May 2019

- DISCUSSION_D.Prokopowicz_..Is capital significance still attributed to behavioral psychology of behavior of stock market investo rs.jpg 295 kB

- 20 Sept 2020

- 28 Aug 2020

- 18 Aug 2020

- 26 Jul 2020

- 13 Aug 2020

- 30 May 2020

- 42 Recommendations

- 30 Jul 2020

- 25 May 2020

- 29 Jul 2020

- 16 Mar 2017

- 27 Jul 2020

- Recruit researchers

- Join for free

- Login Email Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google Welcome back! Please log in. Email · Hint Tip: Most researchers use their institutional email address as their ResearchGate login Password Forgot password? Keep me logged in Log in or Continue with Google No account? Sign up

Psychology Unlocked

The free online psychology textbook, social psychology research topics.

January 24, 2017 Daniel Edward Blog , Social Psychology 0

Whether you’re looking for social psychology research topics for your A-Level or AP Psychology class, or considering a research question to explore for your Psychology PhD, the Psychology Unlocked list of social psychology research topics provides you with a strong list of possible avenues to explore.

Where possible we include links to university departments seeking PhD applications for certain projects. Even if you are not yet considering PhD options, these links may prove useful to you in developing your undergraduate or masters dissertation.

Lots of university psychology departments provide contact details on their websites.

If you read a psychologist’s paper and have questions that you would like to learn more about, drop them an email.

Lots of psychologists are very happy to receive emails from genuinely interested students and are often generous with their time and expertise… and those who aren’t will just overlook the email, so no harm done either way!

Psychology eZine

Subscribe to our weekly newsletter for videos, articles, news and more.

We use Sendinblue as our marketing platform. By Clicking below to submit this form, you acknowledge that the information you provided will be transferred to Sendinblue for processing in accordance with their terms of use

- The Dunning-Kruger Effect: Why we think we know more than we do

- The Yale Food Addiction Scale: Are you addicted to food?

- Addicted to Pepsi Max? Understand addiction in six minutes (video)

- Functional Fixedness: The cognitive bias and how to beat it

- Summer Spending Spree! How Summer Burns A Hole In Your Pocket

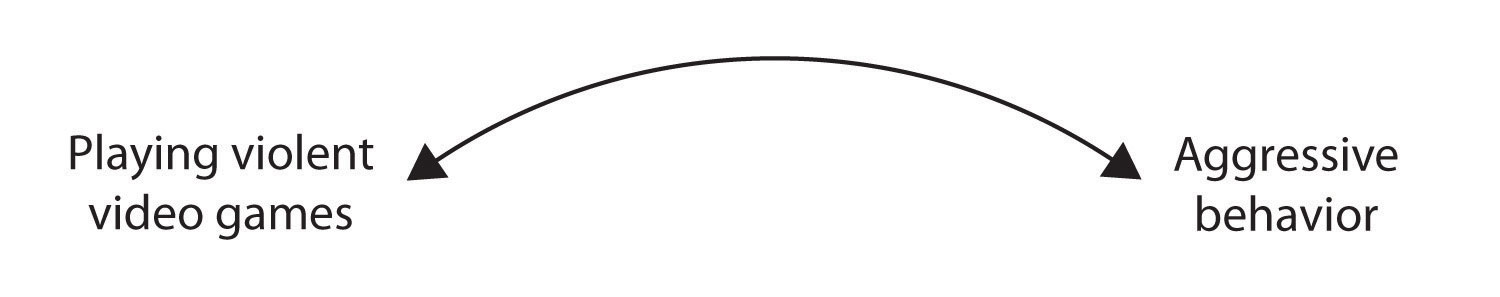

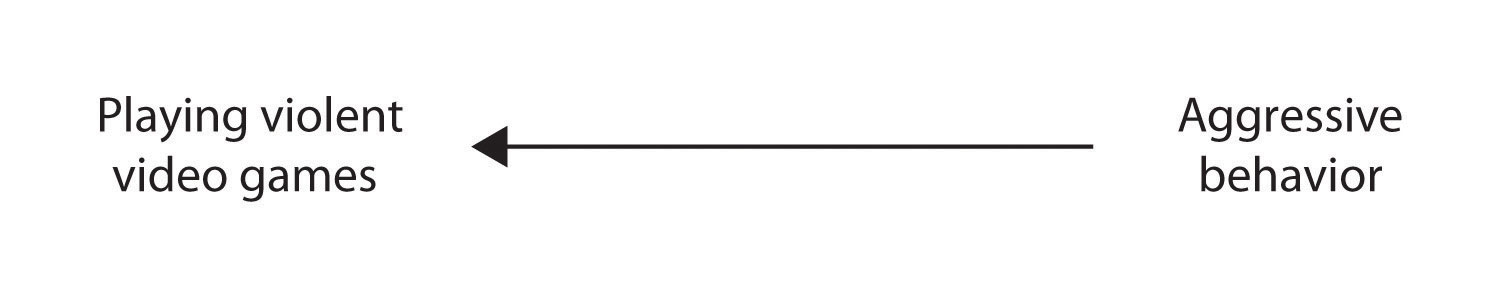

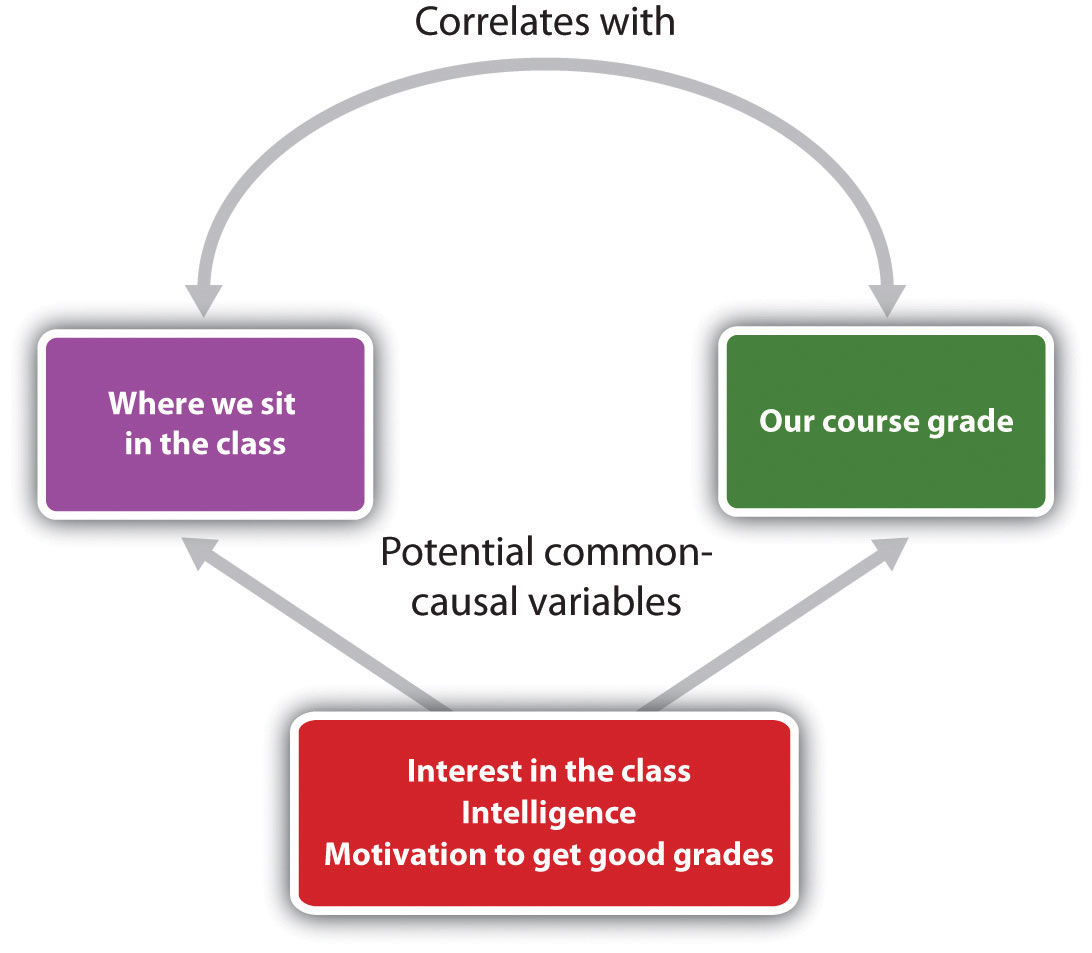

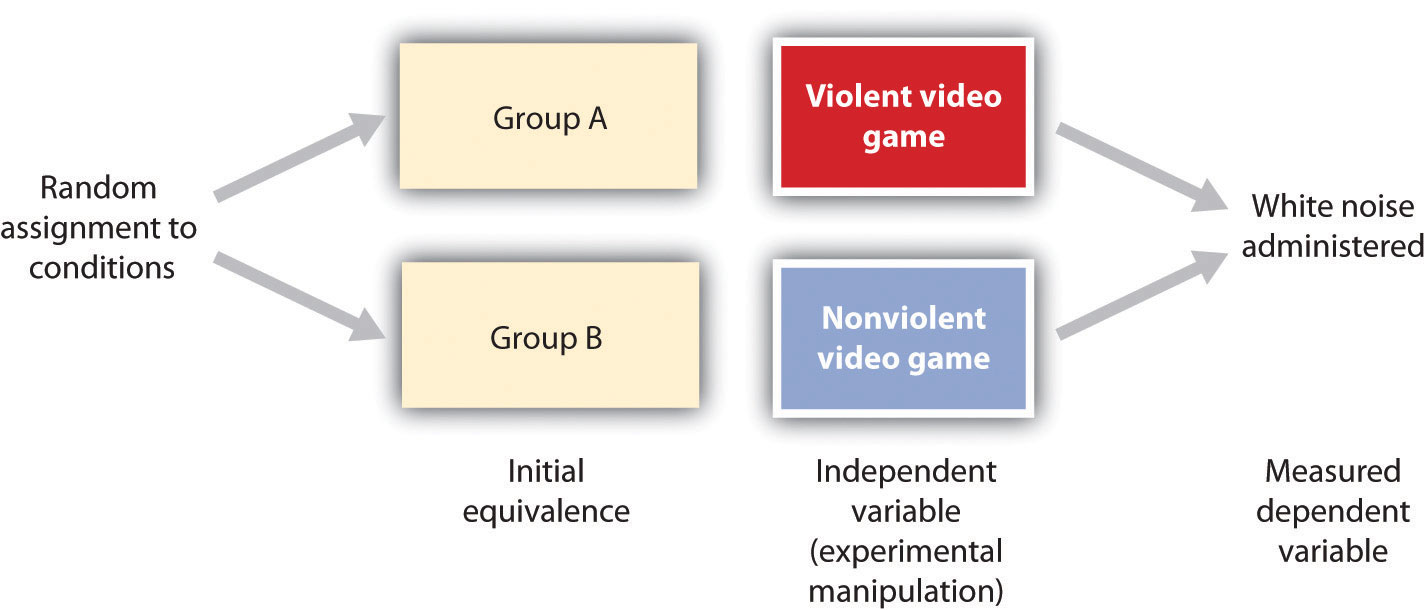

What social factors are involved with the development of aggressive thoughts and behaviours? Is aggression socially-defined? Do different societies have differing definitions of aggression?

There has recently been a significant amount of research conducted on the influence of video games and television on aggression and violent behaviour.

Some research has been based on high-profile case studies, such as the aggressive murder of Jamie Bulger in 1993 by two children (Robert Thompson and Jon Venables). There is also a significant body of experimental research.

Attachment and Relationships

This is a huge area of research with lots of crossover into developmental psychology. What draws people together? How do people connect emotionally? What is love? What is friendship? What happens if someone doesn’t form an attachment with a parental figure?

This area includes research on attachment styles (at various stages of life), theories of love, friendship and attraction.

Attitudes and Attitude Change

Attitudes are a relatively enduring and general evaluation of something. Individuals hold attitudes on everything in life, from other people to inanimate objects, groups to ideologies.

Attitudes are thought to involve three components: (1) affective (to do with emotions), (2) behavioural, and (3) cognitive (to do with thoughts).

Research on attitudes can be closely linked to Prejudice (see below).

Authority and Leadership

Perhaps the most famous study of authority is Milgram’s (1961) Obedience to Authority . This research area has grown into a far-reaching and influential topic.

Research considers both positive and negative elements of authority, and applied psychology studies consider the role of authority in a particular social setting, such as advertising, in the workplace, or in a classroom.

The Psychology of Crowds (Le Bon, 1895) paved a path for a fascinating area of social psychology that considers the social group as an active player.

Groups tend to act differently from individuals, and specific individuals will act differently depending on the group they are in.

Social psychology research topics about groups consider group dynamics, leadership (see above), group-think and decision-making, intra-group and inter-group conflict, identities (see below) and prejudices (see below).

Gordon Allport’s (1979) ‘The Nature of Prejudice’ is a seminal piece on group stereotyping and discrimination.

Social psychologists consider what leads to the formation of stereotypes and prejudices. How and why are prejudices used? Why do we maintain inaccurate stereotypes? What are the benefits and costs of prejudice?

This interesting blog post on the BPS Digest Blog may provide some inspiration for research into prejudice and political uncertainty.

Pro- and Anti-Social Behaviour

Behaviours are only pro- or anti-social because of social norms that suggest so. Social Psychologists therefore investigate the roots of these behaviours as well as considering what happens when social norms are ignored.

Within this area of social psychology, researchers may consider why people help others (strangers as well as well as known others). Another interesting question regards the factors that might deter an individual from acting pro-socially, even if they are aware that a behaviour is ‘the right thing to do’.

The bystander effect is one such example of social inaction.

Self and Social Identity

Tajfel and Turner (1979) proposed Social Identity Theory and a large body of research has developed out of the concepts of self and social identity (or identities).

Questions in this area include: what is identity? What is the self? Does a social identity remain the same across time and space? What are the contributory factors to an individual’s social identity?

Zimbardo’s (1972) Stanford Prison Experiment famously considered the role of social identities.

Research in this area also links with work on groups (see above), social cognition (see below), and prejudices (see above).

Social Cognition

Social cognition regards the way we think and use information. It is the cross-over point between the fields of social and cognitive psychology.

Perhaps the most famous concept in this area is that of schemas – general ideas about the world, which allow us to make sense of new (and old) information quickly.

Social cognition also includes those considering heuristics (mental shortcuts) and some cognitive biases.

Social Influence

This is one of the first areas of social psychology that most students learn. Remember the social conformity work by Asch (1951) on the length of lines?

Other social psychology research topics within this area include persuasion and peer-pressure.

Social Representations

Social Representations (Moscovici, 1961) ‘make something unfamiliar, or unfamiliarity itself, familiar’ (Moscovici, 1984). This is a theory with its academic roots in Durkheim’s theory of collective representations.

Researchers working within this framework consider the social role of knowledge. How does information translate from the scientific realm of expert knowledge to the socially accessible realm of the layperson? How do we make sense of new information? How do we organise separate and distinct facts in a way that make sense to our needs?

One of the most famous studies using Social Representations Theory is Jodelet’s (1991) study of madness.

- Social Article

- Social Psychology

Copyright © 2024 | WordPress Theme by MH Themes

- Social Psychology and Social Processes

- Reconciling cultural and professional power in psychotherapy from The Humanistic Psychologist August 30, 2024

- Sexual orientation and gender diversity research manuscript writing guide from Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity July 19, 2024

- The associations between internet use and well-being from Technology, Mind, and Behavior July 9, 2024

- Fostering school safety and valuing intersectional identities: Promoting Black queer youths’ sense of belonging in schools from Translational Issues in Psychological Science June 25, 2024

- Steady as she goes! Daily fluctuations in cognitive ability are associated with risk of Alzheimer’s disease from Neuropsychology March 22, 2024

- Risks and protective factors for young immigrant language brokers who experience discrimination from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority March 1, 2024

- Bringing effective posttraumatic stress disorder treatment to those in need: Prolonged exposure for primary care from Psychological Services February 22, 2024

- The multicultural play therapy room: Intentional decisions on toys and materials from International Journal of Play Therapy February 6, 2024

- Workplace racial composition is an important factor for Black parents’ communication of racial socialization messages from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology November 28, 2023

- Children’s ethnic–racial identity and mothers’ cultural socialization are protective for young Latine children’s mental health from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology October 11, 2023

- The effects of personal and family perfectionism on psychological functioning among Asian and Latinx youths in the United States from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology September 5, 2023

- Racial ingroup identification can predict attitudes toward paying college athletes from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology July 13, 2023

- Your stress is my stress: Sexual minority stress and relationship functioning in female same-gender couples from Couple and Family Psychology: Research and Practice June 8, 2023

- Where manhood is fragile, men die young from Psychology of Men & Masculinities March 20, 2023

- Innovative theory and methods for the next generation of diversity, equity, and inclusion sciences from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology March 10, 2023

- Losing my religion: Who walks away from their faith and why? from Psychology of Religion and Spirituality March 1, 2023

- Peace studies and the legacy of Emile Bruneau from Peace and Conflict: Journal of Peace Psychology December 1, 2022

- Diverse audience members’ responses to diverse movie superheroes: When does a demographic match between the viewer and a character make a difference? from Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts November 30, 2022

- Group psychology and the January 6 insurrection from Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice September 15, 2022

- The positive relationship between indigenous language use and community-based well-being in four Nahua ethnic groups in Mexico from Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology August 30, 2022

- Ethnicity matters: Effects of ethnic-racial socialization for African American and Caribbean Black adolescents from Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology August 9, 2022

- How do people of color resist racism? from Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology June 28, 2022

- Social support and identity help explain how gendered racism harms Black women’s mental health from Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology May 10, 2022

- Cognitive biases can affect experts’ judgments: A broad descriptive model and systematic review in one domain from Law and Human Behavior May 4, 2022

- Sticking together: Creating cohesive collectives April 5, 2022 from Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice

- Special double issue: Savoring Buddhist and contemporary practices of mindfulness: Challenges and opportunities November 18, 2021 from The Humanistic Psychologist

- The long shadows of bad policies: A model for understanding the psychological impacts of Indian residential schools in Canada from Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne October 12, 2021

- Why are interracial interactions so hard? “Learning goals” open the door to more positive relations from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology August 27, 2021

- How do young adult immigrants engage civically? What role does social connection play? from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology July 28, 2021

- Does COVID-19 affect the fairness of the plea process for defendants? from Law and Human Behavior May 3, 2021

- How can we provide quality care for incarcerated transgender individuals? from Psychological Services April 19, 2021

- Resisting health mandates: A case of groupthink? from Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice March 10, 2021

- Get out of jail free? Achieving racial equity in pretrial reform from Law and Human Behavior February 5, 2021

- Moving away from using ethnicity as a proxy for cultural values from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology December 16, 2020

- New ways of measuring “The Talk”: Considering racial socialization quality and quantity from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology December 10, 2020

- Building a cumulative psychological science: Looking back and looking forward from Canadian Psychology / Psychologie canadienne November 30, 2020

- The group dynamics of COVID-19 from Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice November 19, 2020

- Body positivity in music: Can listening to a single song help you feel better about your body? from Psychology of Popular Media November 5, 2020

- Does better memory help to maintain physical health? from Psychology and Aging October 22, 2020

- Do beliefs about God affect suicide risk? A study of “Divine Struggle” among men recovering from substance abuse from Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity September 15, 2020

- Do beliefs about sexual orientation predict voting? Findings from the 2016 U.S. presidential election from Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity August 17, 2020

- Is this apartment still available? Maybe not for exonerees from Law and Human Behavior August 17, 2020

- Discrimination affects both physical health and relationships in Black families from Journal of Family Psychology August 17, 2020

- Toppled statues and peaceful marches: How do privileged group members react to protests for social equality? from Journal of Personality and Social Psychology July 10, 2020

- Can strongly identifying with both ethnic and national cultures protect immigrants from hostile social contexts? from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology May 27, 2020

- Fundamental Questions in Emotion Regulation from Emotion April 21, 2020

- Does It Make Sense to Say That Groups Are Satisfied? Multilevel Measurement Models for Group Collective Constructs from Group Dynamics: Theory, Research, and Practice March 26, 2020

- How Do Recent College Graduates Navigate Ideological Bubbles? Findings From a Longitudinal Qualitative Study from Journal of Diversity in Higher Education March 24, 2020

- What Is the Role of Economic Insecurity in Health? The Unequal Burden of Sexual Assault Among Women from Psychology of Violence March 17, 2020

- Who Identifies as Queer? A Study Looks at the Partnering Patterns of Sexual Minority Populations from Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity February 24, 2020

- Current Evolutionary Perspectives on Women from Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences February 14, 2020

- Perceived Underemployment Among African American Parents: What Are the Implications for Couples’ Relationships? from Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology February 6, 2020

- Should Seeing Be Believing? Evidence-Based Recommendations by Psychologists May Reduce Mistaken Eyewitness Identifications from Law and Human Behavior January 27, 2020

- Patterns of Alcohol Use Among Minority Populations in the U.S. from American Journal of Orthopsychiatry December 17, 2019

- Was Everything Better in the Good Old Days? from Psychology and Aging December 13, 2019

- Does Cultural Revitalization Impact Academic Attainment and Healthy Living? from Cultural Diversity & Ethnic Minority Psychology November 27, 2019

- What’s Next for Graduate Training in Psychology in Canada? from Canadian Psychology November 13, 2019

- How Should We Decide Whom to Imprison? The Use of Risk Assessment Instruments in Sentencing Decisions from Law and Human Behavior October 23, 2019

- Are Two Heads Better Than One? The Effects of Interviewer Familiarity and Supportiveness on Children’s Testimony In Repeated Interviews from Law and Human Behavior October 9, 2019

- Basic Statistical Errors Are Common in Canadian Psychology Journals...But the Computer Programs That Detect Them Are Far From Perfect from Canadian Psychology September 24, 2019

- Connecting the Dots: Identifying Suspected Serial Sexual Offenders Through Forensic DNA Evidence from Psychology of Violence September 18, 2019

- Racial / Ethnic Differences in Caregivers' Perceptions of the Need for and Utilization of Adolescent Psychological Counseling and Support Services from Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology August 27, 2019

- New Directions in the Study of Human Emotional Development from Developmental Psychology August 23, 2019

- Can Moral Judgment, Critical Thinking, and Islamic Fundamentalism Explain ISIS and Al-Qaeda's Armed Political Violence from Psychology of Violence August 9, 2019

- Drawing Legal Age Boundaries: A Tale of Two Maturities from Law and Human Behavior July 3, 2019

- Tabling, Discussing, and Giving In: Meeting Dissent in Three Workgroups from Group Dynamics May 30, 2019

- Microaggressions: What They Are, And How They Are Associated With Adjustment Outcomes from Psychological Bulletin April 10, 2019

- Updating Maps for a Changing Territory: Redefining Youth Marginalization from American Psychologist October 12, 2018

- From Exotic to Invisible: Asian American Women's Experiences of Discrimination from Asian American Journal of Psychology July 26, 2018

- Taking A Closer Look at Social Comparison Theory from Psychological Bulletin April 19, 2018

- Age-Related Differences in Associative Memory: Empirical Evidence and Theoretical Perspectives from Psychology and Aging March 21, 2018

- Secure or Insecure? A Culturally Sensitive Tool to Assess the Emotional Components of Attachment from International Perspectives in Psychology December 15, 2017

- How Writers Create Engaging Characters: Exploring the Role of Personality, Empathy, and Experience from Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts November 29, 2017

- Learning, Interrupted: Cell Phone Calls Sidetrack Toddlers' Word Learning from Developmental Psychology November 21, 2017

- The Stories We Tell: Exploring the Professional Narratives of Latino/a Psychologists from Journal of Latina/o Psychology November 7, 2017

- Gratitude and Capacity for Prosociality: Findings from a Meta-Analytic Review from Psychological Bulletin August 16, 2017

- Does Research Support Classroom Trigger Warnings? from Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in Psychology July 27, 2017

- Campus Threat Management from Journal of Threat Assessment and Management May 5, 2017

- Is There Such a Thing as Asian Culture? Unveiling Asian American Achievement from Asian American Journal of Psychology April 12, 2017

- The Experiences of Chinese American Young Adults Who Have Gay and Lesbian Siblings from Asian American Journal of Psychology September 6, 2016

- Neural Evidence for Growth in Pure Altruism Across the Adult Life Span from Journal of Experimental Psychology: General September 1, 2016

- Are Violent Video Games Associated With More Civic Behaviors Among Youth? from Psychology of Popular Media Culture August 9, 2016

- A Sex Difference in Sports Interest: What Does Evolution Say? from Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences May 4, 2016

- What's the Relational Toll of Living in a Sexist and Heterosexist Context? from Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity March 23, 2016

- Dealing With the Past: Survivors of Severe Human Rights Abuses and Their Perspectives on Economic Reparations in Argentina from International Perspectives in Psychology January 28, 2016

- Is Suicide a Tragic Variant of an Evolutionarily Adaptive Set of Behaviors? from Psychological Review January 12, 2016

- Special Issue on Collective Harmdoing from Peace and Conflict December 8, 2015

- Evaluators, Not Just Those They Evaluate, Influence Personality Test Results from Law and Human Behavior December 2, 2015

- The New Normal? Addressing Gun Violence in America from American Journal of Orthopsychiatry May 28, 2015

- Gay and Poor: The Intersection of Sexual Orientation and Socioeconomic Status from Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity March 17, 2015

- You're So Gay: Homophobic Name Calling as Bullying Behavior from American Journal of Orthopsychiatry February 24, 2015

- The Behavioral Immune System: Taking Stock and Charting New Directions from Evolutionary Behavioral Sciences December 2, 2014

- Gay and Married, or Single and Straight? from Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity November 12, 2014

- Heaven, Help Us from Journal of Family Psychology October 22, 2014

- It Gets Better, Right? from Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Sexual Diversity September 16, 2014

- Does Children's Biological Functioning Predict Parenting Behavior? from Developmental Psychology September 10, 2014

- We're in This Together from Journal of Family Psychology August 12, 2014

- The Chief Diversity Officer from Journal of Diversity in Higher Education July 24, 2014

- There's No Place Like Home from American Journal of Orthopsychiatry June 11, 2014

- Sexual Orientation and Custody Disputes: How Research Can Influence Policy and Practice from Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity April 28, 2014

- Replication from Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts March 24, 2014

- What a Piece of Work Is a Man from Psychology of Men and Masculinity October 23, 2013

- Predicting and Preventing Sexual Aggression by College Men from Psychology of Violence September 12, 2013

- When Two Wrongs Make a Third Wrong from Law and Human Behavior September 10, 2013

- Fighting Fire With Fire from Psychology of Violence August 13, 2013

View more journals in the Social Psychology and Social Processes subject area.

APA Journals Article Spotlight ®

APA Journals Article Spotlight is a free summary of recently published articles in an APA Journal .

Browse Article Spotlight topics

- Basic/Experimental Psychology

- Clinical Psychology

- Core of Psychology

- Developmental Psychology

- Educational Psychology, School Psychology, and Training

- Forensic Psychology

- Health Psychology and Medicine

- Industrial/Organizational Psychology and Management

- Neuroscience and Cognition

Contact APA Publications

Current Research in Social Psychology

Editors: michael lovaglia, university of iowa; shane soboroff, st. ambrose university.

Current Research in Social Psychology ( CRISP ) is a peer reviewed, electronic journal publishing theoretically driven, empirical research in major areas of social psychology. Publication is sponsored by the Center for the Study of Group Processes at the University of Iowa, which provides free access to its contents. Authors retain copyright for their work. CRISP is permanently archived at the Library of the University of Iowa and at the Library of Congress. Beginning in April, 2000, Sociological Abstracts publishes the abstracts of CRISP articles.

Citation Format: Lastname , Firstname . 1996. "Title of Article." Current Research in Social Psychology 2:15-22 https://crisp.org.uiowa.edu

RECENT ISSUES

Finding Positives in the Pandemic: The Role of Relationship Status, Self-Esteem, Mental Health, and Personality.

Examining Public Attitudes And Ideological Divides Through Media Engagement: An Empirical Analysis of Moral Foundations Theory Amidst the Covid-19 Pandemic.

When Race is Not Enough: Lessons Learned Using Racially Tagged Names.

Formation of a Positive Social Identity: How Significant are Attitudes, Subjective Norms, and Perceived Similarity Concerning Group Identification?

Passive Social Network Usage and Hedonic Well-Being Among Vietnamese University Students: A Moderated Mediation Model Involving Self-Esteem and Sense of Self.

Cognitive Dissonance and Depression: A Qualitative Exploration of a Close Relationship.

Gender Differences in Support for Collective Punishment: The Moderating Role of Malleability Mindset.

Hard Feelings? Predicting Attitudes Toward Former Romantic Partners.

Perceived Control in Multiple Option Scenarios: Choice, Control, and the Make-a-Difference Metric.

Drivers of Prosocial Behavior: Exploring the Role of Mindset and Perceived Cost.

Malleability of Laïcité: People with High Social Dominance Orientation Use Laïcité to Legitimize Public Prayer by Catholics but not by Muslims.

Differences and Predictive Abilities of Competitiveness Between Motivation Levels, Contexts, and Sex.

Parental Rejection and Peer Acceptance: The Mediating Role of Cognitive Bias.

A Novel Approach for Measuring Self-Affirmation.

Ingroup Bias in the Context of Meat Consumption: Direct and Indirect Attitudes Toward Meat-Eaters and Vegetarians.

Perceptions of Case Complexity and Pre-Trial Publicity Through the Lens of Information Processing.

"Muslims' Desire for Intergroup Revenge in the Aftermath of the Christchurch Attack: The Predictive Role of Ingroup Identification, Perceived Intergroup Threat, and the Norm of Reciprocity. "

"Personal Networks and Social Support in Disaster Contexts."

"Aggressive and Avoidant Action Tendencies Towards Out-Groups: The Distinct Roles of In-Group Attachment vs. Glorification and Cognitive vs. Affective Ambivalence."

"We (Might) Want You: Expectations of Veterans' General Competence and Leadership."

"Situation Attribution Mediates Intention to Overlook Negative Signals Among Romantic Partners."

"Software Program, Bot, or Artificial Intelligence? Affective Sentiments across General Technology Labels"

"Privilege is Invisible to Those Who Have It": Some Evidence that Men Underestimate the Magnitude of Gender Differences in Income.

"Perceived Control and Intergroup Discrimination."

"Leadership, Gender, and Vocal Dynamics in Small Groups."

Taking Responsibility for an Offense: Being Forgiven Encourages More Personal Responsibility, More Empathy for the Victim, and Less Victim Blame.

Potential Factors Influencing Attitudes Toward Veterans Who Commit Crimes: An Experimental Investigation of PTSD in the Legal System.

"Is that Discrimination? I'd Better Report it!" Self-presentation Concerns Moderate the Prototype Effect.

Relation Between Attitudinal Trust and Behavioral Trust: An Exploratory Study

Comparing Groups' Affective Sentiments to Group Perceptions.

Perceived Autonomous Help and Recipients' Well-Being: Is Autonomous Help Good for Everyone.

S tudying Gay and Straight Males' Implicit Gender Attitudes to Understand Previously Found Gender Differences in Implicit In-Group Bias.

Nepotistic Preferences in a Computerized Trolley Problem.

Telecommuting, Primary Caregiving, and Gender as Status .

You're Either With Us or Against Us: In-Group Favoritism and Threat .

Impact of the Anticipation of Membership Change on Transactive Memory and Group Performance.

Mindfulness Increases Analytical Thought and Decreases Just World Beliefs .

Status, Performance Expectations, and Affective Impressions: An Experimental Replication.

The Effects of African-American Stereotype Fluency on Prejudicial Evaluation of Targets .

Status Characteristics and Self-Categoriation: A Bridge Across theoretical Traditions.

Why do Extraverts Feel More Positive Affect and Life Satisfaction? The Indirect Effects of Social Contribution and Sense of Power.

In-group Attachment and Glorification, Perceptions of Cognition-Based Ambivalence as Contributing to the Group, and Positive Affect.

Mentoring to Improve a Child's Self-Concept: Longitudinal Effects of Social Intervention on Identity and Negative Outcomes.

Affect, Emotion, and Cross-Cultural Differences in Moral Attributions.

The Effects of Counterfactual Thinking on College Students' Intentions to Quit Smoking Cigarettes .

Self-Enhancement, Self-Protection and Ingroup Bias.

The Moderating Effect of Socio-emotional Factors on the Relationship Between Status and Influence in Status Characteristics Theory.

What We Know About People Shapes the Inferences We Make About Their Personalities.

The Pros and Cons of Ingroup Ambivalence: The Moderating Roles of Attitudinal Basis and Individual Differences in Ingroup Attachment and Glorification.

Effects of Social Anxiety and Group Membership of Potential Affiliates on Social Reconnection After Ostracism.

"Yes, I Decide You Will Recieve Your Choice": Effects of Authoritative Agreement on Perceptions of Control.

Being Generous to Look Good: Perceived Stigma Increases Prosocial Behavior in Smokers.

Acting White? Black Young Adults Devalue Same-Race Targets for Demonstrating Positive-but-Stereotypically White Traits

Looking Up for Answers: Upward Gaze Increases Receptivity to Advice

Which Judgement Do Women Expect from a Female Observer When They Claim to be a Victim of Sexism?

Neighborhood Deterioration and Perceptions of Race

The Use of Covert and Overt Jealousy Tactics in Romantic Relationships: The Moderating Role of Relationship Satisfaction

The Impact of Status Differences on Gatekeeping: A Theoretical Bridge and Bases for Investigation

Reducing Prejudice with (Elaborated) Imagined and Physical Intergroup Contact Interverventions

Are Depressed Individuals More Susceptible to Cognitive Dissonance?

Gender Differences in the Need to Belong: Different Cognitive Representations of the Same Social Groups

Fight The Power: Comparing and Evaluating Two Measures of French and Raven's (1959) Bases of Social Power

Mother Knows Best So Mother Fails Most: Benevolent Stereotypes and the Punishment of Parenting Mistakes

Blame Attributions about Disloyalty

Attitudes Towards Muslims are More Favorable on a Survery than on an Implicit Relational Assessment Procedure

Attributions to Low Group Effort can Make You Feel Better: The Distinct Roles of In-group Identification, Legitimacy of Intergroup Status, and Controllability Perceptions

The Role of Collective and Personal Self-Esteem in a Military Context

On Bended Knee: Embodiment and Religious Judgments

Identity Salience and Identity Importance in Identity Theory

Sexist Humor and Beliefs that Justify Societal Sexism

Future-Oriented People Show Stronger Moral Concerns

Further Examining the Buffering Effect of Self-Esteem and Mastery on Emotions

Group-Based Resiliency: Contrasting the Negative Effects of Threat to the In-Group

You Validate Me, You Like Me, You're Fun, You Expand Me: "I'm Yours!"

Pleading Innocents: Laboratory Evidence of Plea Bargaining's Innocence Problem

The Moral Identity and Group Affiliation

Threat, Prejudice, and Stereotyping in the Context of Japanese, North Korean, and South Korean Intergroup Relations

Exams may be Dangerous to Grandpa's Health: How Inclusive Fitness Influences Students' Fraudulent Excuses

To View Archived CRISP Issues Click here

To View the Notice for Contributors Click here . Includes formatting and citation guidelines.

To View the Editorial Board Click here

Instant insights, infinite possibilities

61 intriguing psychology research topics to explore

Last updated

11 January 2024

Reviewed by

Brittany Ferri, PhD, OTR/L

Short on time? Get an AI generated summary of this article instead

Psychology is an incredibly diverse, critical, and ever-changing area of study in the medical and health industries. Because of this, it’s a common area of study for students and healthcare professionals.

We’re walking you through picking the perfect topic for your upcoming paper or study. Keep reading for plenty of example topics to pique your interest and curiosity.

- How to choose a psychology research topic

Exploring a psychology-based topic for your research project? You need to pick a specific area of interest to collect compelling data.

Use these tips to help you narrow down which psychology topics to research:

Focus on a particular area of psychology

The most effective psychological research focuses on a smaller, niche concept or disorder within the scope of a study.

Psychology is a broad and fascinating area of science, including everything from diagnosed mental health disorders to sports performance mindset assessments.

This gives you plenty of different avenues to explore. Having a hard time choosing? Check out our list of 61 ideas further down in this article to get started.

Read the latest clinical studies

Once you’ve picked a more niche topic to explore, you need to do your due diligence and explore other research projects on the same topic.

This practice will help you learn more about your chosen topic, ask more specific questions, and avoid covering existing projects.

For the best results, we recommend creating a research folder of associated published papers to reference throughout your project. This makes it much easier to cite direct references and find inspiration down the line.

Find a topic you enjoy and ask questions

Once you’ve spent time researching and collecting references for your study, you finally get to explore.

Whether this research project is for work, school, or just for fun, having a passion for your research will make the project much more enjoyable. (Trust us, there will be times when that is the only thing that keeps you going.)

Now you’ve decided on the topic, ask more nuanced questions you might want to explore.

If you can, pick the direction that interests you the most to make the research process much more enjoyable.

- 61 psychology topics to research in 2024

Need some extra help starting your psychology research project on the right foot? Explore our list of 61 cutting-edge, in-demand psychology research topics to use as a starting point for your research journey.

- Psychology research topics for university students

As a university student, it can be hard to pick a research topic that fits the scope of your classes and is still compelling and unique.

Here are a few exciting topics we recommend exploring for your next assigned research project:

Mental health in post-secondary students

Seeking post-secondary education is a stressful and overwhelming experience for most students, making this topic a great choice to explore for your in-class research paper.

Examples of post-secondary mental health research topics include:

Student mental health status during exam season

Mental health disorder prevalence based on study major

The impact of chronic school stress on overall quality of life

The impacts of cyberbullying

Cyberbullying can occur at all ages, starting as early as elementary school and carrying through into professional workplaces.

Examples of cyberbullying-based research topics you can study include:

The impact of cyberbullying on self-esteem

Common reasons people engage in cyberbullying

Cyberbullying themes and commonly used terms

Cyberbullying habits in children vs. adults

The long-term effects of cyberbullying

- Clinical psychology research topics

If you’re looking to take a more clinical approach to your next project, here are a few topics that involve direct patient assessment for you to consider:

Chronic pain and mental health

Living with chronic pain dramatically impacts every aspect of a person’s life, including their mental and emotional health.

Here are a few examples of in-demand pain-related psychology research topics:

The connection between diabetic neuropathy and depression

Neurological pain and its connection to mental health disorders

Efficacy of meditation and mindfulness for pain management

The long-term effects of insomnia

Insomnia is where you have difficulty falling or staying asleep. It’s a common health concern that impacts millions of people worldwide.

This is an excellent topic because insomnia can have a variety of causes, offering many research possibilities.

Here are a few compelling psychology research topics about insomnia you could investigate:

The prevalence of insomnia based on age, gender, and ethnicity

Insomnia and its impact on workplace productivity

The connection between insomnia and mental health disorders

Efficacy and use of melatonin supplements for insomnia

The risks and benefits of prescription insomnia medications

Lifestyle options for managing insomnia symptoms

The efficacy of mental health treatment options

Management and treatment of mental health conditions is an ever-changing area of study. If you can witness or participate in mental health therapies, this can make a great research project.

Examples of mental health treatment-related psychology research topics include:

The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) for patients with severe anxiety

The benefits and drawbacks of group vs. individual therapy sessions

Music therapy for mental health disorders

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) for patients with depression

- Controversial psychology research paper topics

If you are looking to explore a more cutting-edge or modern psychology topic, you can delve into a variety of controversial and topical options:

The impact of social media and digital platforms

Ever since access to internet forums and video games became more commonplace, there’s been growing concern about the impact these digital platforms have on mental health.

Examples of social media and video game-related psychology research topics include:

The effect of edited images on self-confidence

How social media platforms impact social behavior

Video games and their impact on teenage anger and violence

Digital communication and the rapid spread of misinformation

The development of digital friendships

Psychotropic medications for mental health

In recent years, the interest in using psychoactive medications to treat and manage health conditions has increased despite their inherently controversial nature.

Examples of psychotropic medication-related research topics include:

The risks and benefits of using psilocybin mushrooms for managing anxiety

The impact of marijuana on early-onset psychosis

Childhood marijuana use and related prevalence of mental health conditions

Ketamine and its use for complex PTSD (C-PTSD) symptom management

The effect of long-term psychedelic use and mental health conditions

- Mental health disorder research topics

As one of the most popular subsections of psychology, studying mental health disorders and how they impact quality of life is an essential and impactful area of research.

While studies in these areas are common, there’s always room for additional exploration, including the following hot-button topics:

Anxiety and depression disorders

Anxiety and depression are well-known and heavily researched mental health disorders.

Despite this, we still don’t know many things about these conditions, making them great candidates for psychology research projects:

Social anxiety and its connection to chronic loneliness

C-PTSD symptoms and causes

The development of phobias

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) behaviors and symptoms

Depression triggers and causes

Self-care tools and resources for depression

The prevalence of anxiety and depression in particular age groups or geographic areas

Bipolar disorder

Bipolar disorder is a complex and multi-faceted area of psychology research.

Use your research skills to learn more about this condition and its impact by choosing any of the following topics:

Early signs of bipolar disorder

The incidence of bipolar disorder in young adults

The efficacy of existing bipolar treatment options

Bipolar medication side effects

Cognitive behavioral therapy for people with bipolar

Schizoaffective disorder

Schizoaffective disorder is often stigmatized, and less common mental health disorders are a hotbed for new and exciting research.

Here are a few examples of interesting research topics related to this mental health disorder:

The prevalence of schizoaffective disorder by certain age groups or geographic locations

Risk factors for developing schizoaffective disorder

The prevalence and content of auditory and visual hallucinations

Alternative therapies for schizoaffective disorder

- Societal and systematic psychology research topics

Modern society’s impact is deeply enmeshed in our mental and emotional health on a personal and community level.

Here are a few examples of societal and systemic psychology research topics to explore in more detail:

Access to mental health services

While mental health awareness has risen over the past few decades, access to quality mental health treatment and resources is still not equitable.

This can significantly impact the severity of a person’s mental health symptoms, which can result in worse health outcomes if left untreated.

Explore this crucial issue and provide information about the need for improved mental health resource access by studying any of the following topics:

Rural vs. urban access to mental health resources

Access to crisis lines by location

Wait times for emergency mental health services

Inequities in mental health access based on income and location

Insurance coverage for mental health services

Systemic racism and mental health

Societal systems and the prevalence of systemic racism heavily impact every aspect of a person’s overall health.

Researching these topics draws attention to existing problems and contributes valuable insights into ways to improve access to care moving forward.

Examples of systemic racism-related psychology research topics include:

Access to mental health resources based on race

The prevalence of BIPOC mental health therapists in a chosen area

The impact of systemic racism on mental health and self-worth

Racism training for mental health workers

The prevalence of mental health disorders in discriminated groups

LGBTQIA+ mental health concerns

Research about LGBTQIA+ people and their mental health needs is a unique area of study to explore for your next research project. It’s a commonly overlooked and underserved community.

Examples of LGBTQIA+ psychology research topics to consider include:

Mental health supports for queer teens and children

The impact of queer safe spaces on mental health

The prevalence of mental health disorders in the LGBTQIA+ community

The benefits of queer mentorship and found family

Substance misuse in LQBTQIA+ youth and adults

- Collect data and identify trends with Dovetail

Psychology research is an exciting and competitive study area, making it the perfect choice for projects or papers.

Take the headache out of analyzing your data and instantly access the insights you need to complete your next psychology research project by teaming up with Dovetail today.

Should you be using a customer insights hub?

Do you want to discover previous research faster?

Do you share your research findings with others?

Do you analyze research data?

Start for free today, add your research, and get to key insights faster

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 18 April 2023

Last updated: 27 February 2023

Last updated: 22 August 2024

Last updated: 5 February 2023

Last updated: 16 August 2024

Last updated: 9 March 2023

Last updated: 30 April 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 4 July 2024

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 5 March 2024

Last updated: 13 May 2024

Latest articles

Related topics, .css-je19u9{-webkit-align-items:flex-end;-webkit-box-align:flex-end;-ms-flex-align:flex-end;align-items:flex-end;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-flex-direction:row;-ms-flex-direction:row;flex-direction:row;-webkit-box-flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-flex-wrap:wrap;-ms-flex-wrap:wrap;flex-wrap:wrap;-webkit-box-pack:center;-ms-flex-pack:center;-webkit-justify-content:center;justify-content:center;row-gap:0;text-align:center;max-width:671px;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}}@media (max-width: 799px){.css-je19u9{max-width:400px;}.css-je19u9>span{white-space:pre;}} decide what to .css-1kiodld{max-height:56px;display:-webkit-box;display:-webkit-flex;display:-ms-flexbox;display:flex;-webkit-align-items:center;-webkit-box-align:center;-ms-flex-align:center;align-items:center;}@media (max-width: 1079px){.css-1kiodld{display:none;}} build next, decide what to build next, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- How it works

Useful Links

How much will your dissertation cost?

Have an expert academic write your dissertation paper!

Dissertation Services

Get unlimited topic ideas and a dissertation plan for just £45.00

Order topics and plan

Get 1 free topic in your area of study with aim and justification

Yes I want the free topic

35 Best Social Psychology Dissertation Topics

Published by Carmen Troy at January 2nd, 2023 , Revised On August 11, 2023

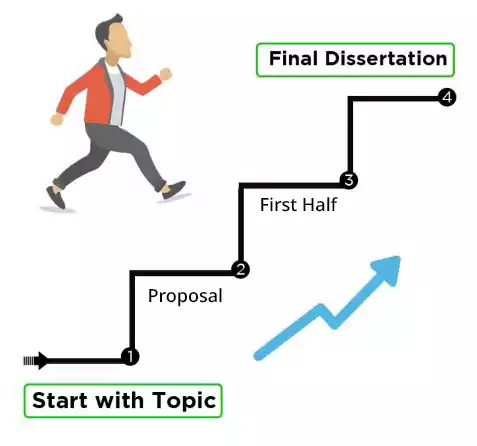

A dissertation or a thesis paper is the fundamental prerequisite to the degree programme, irrespective of your academic discipline. The field of social psychology is not different.

When working on the dissertation, the students must demonstrate what they wish to accomplish with their study. They must be authentic with their ideas and solutions to achieve the highest possible academic grade.

A dissertation in social psychology should examine the influence others have on people’s behaviour. This is because the interaction of people in different groups is the main focus of the discipline. Social connections in person are the main focus of social psychology and therefore your chosen social psychology topic should be based on a real-life social experience or phenomenon.

Also read: Sociology dissertation topics

We have compiled a list of the top social psychology dissertation topics to help you get started.

List of Social Psychology Dissertation Topics

- What impact do priming’s automatic effects have on complex behaviour in everyday life?

- The social intuitionist model examines the role that emotion and reason play in moral decision-making.

- Examine the lasting effects of cognitive dissonance.

- What psychological consequences does spanking have on kids?

- Describe the consequences and root causes of childhood attention-deficit / hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

- Explain the causes of antisocial behaviour in young people.

- Discuss infants’ early warning symptoms of mental disease.

- List the main factors that young adults most commonly experience; increased stress and depression.

- Describe several forms of torture in detail, emphasising how they affect children’s minds and adult lives.

- Describe the impact of violent video games and music on a child’s development.

- Talk about how the family influences early non-verbal communication in infants.

- Examine the scope and persistence of the variables influencing the impact of automatic priming on social behaviour.

- What does this mean for upholding one’s integrity and comprehending interpersonal relationships?

- Examine the connection between loneliness and enduring health issues.

- Identify several approaches to measuring older people’s social networks.

- Compare and contrast the types of social networks, housing, and elderly people’s health across time.

- The primary causes of young people’s moral decline are social influences. Discuss.

- Discuss what has improved our understanding of social psychology using examples from social psychology theories.

- What are the socio-psychological reasons and consequences of drinking alcohol?

- What makes some persons more attractive in social situations?

- Discuss how culture affects a society’s ability to be cohesive and united.

- Discuss how a person’s career affects their social standing in society.

- What psychological effects might long-term caregiving have?

- How ddoesa leader’s relationship and followers change under charismatic leadership?

- Discuss the tactics that support and thwart interpersonal harmony using the group identity theory as your foundation.

- Discuss the benefits and drawbacks of intimate cross-cultural relationships.

- Examine and clarify the socio-psychological components of cults using examples.

- Discuss how sociocultural perceptions have an impact on socio-psychology.

- How has technology affected communication and interpersonal relationships?

- What part does religion play in bringing people together?

- Describe the socio-psychological impacts of dense population and crowded living.

- What are the effects of a child’s introverted personality on others?

- Explain how carelessness on the part of parents and childhood obesity are related.

- Study the psychological, moral, and legal ramifications of adoption.

- What are the corrective and preventative steps that can stop child abuse?

Note: Along with free dissertation topics , ResearchProspect also provide top-notch dissertation writing services at the best price to ease the excessive study load.

Hire a Dissertation Writer

Orders completed by our expert writers are

- Formally drafted in an academic style

- Free Amendments and 100% Plagiarism Free – or your money back!

- 100% Confidential and Timely Delivery!

- Free anti-plagiarism report

- Appreciated by thousands of clients. Check client reviews

Choosing social psychology dissertation topics can be frustrating. We have provided you with original dissertation topic suggestions to aid you in developing a thought-provoking and worthwhile dissertation for your degree.

If you need help with the complete dissertation writing process, you may want to additionally read about our proposal writing service and the full dissertation writing service .

Free Dissertation Topic

Phone Number

Academic Level Select Academic Level Undergraduate Graduate PHD

Academic Subject

Area of Research

Frequently Asked Questions

How to find social psychology dissertation topics.

To discover social psychology dissertation topics:

- Explore recent research in journals.

- Investigate real-world social issues.

- Examine psychological theories.

- Consider cultural influences.

- Brainstorm topics aligned with your passion.

- Aim for novelty and significance in your chosen area.

You May Also Like

Need interesting and manageable history dissertation topics or thesis? Here are the trending history dissertation titles so you can choose the most suitable one.

Engineering is one of the most rewarding careers in the world. With solid research, investigation and analysis, engineering students dig deep through different engineering scopes to complete their degrees.

Medical law becomes increasingly important as healthcare dominates as a social issue. Graduate students must select a thesis subject as part of their programs. The subject you choose must have sufficient data to support your thesis.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

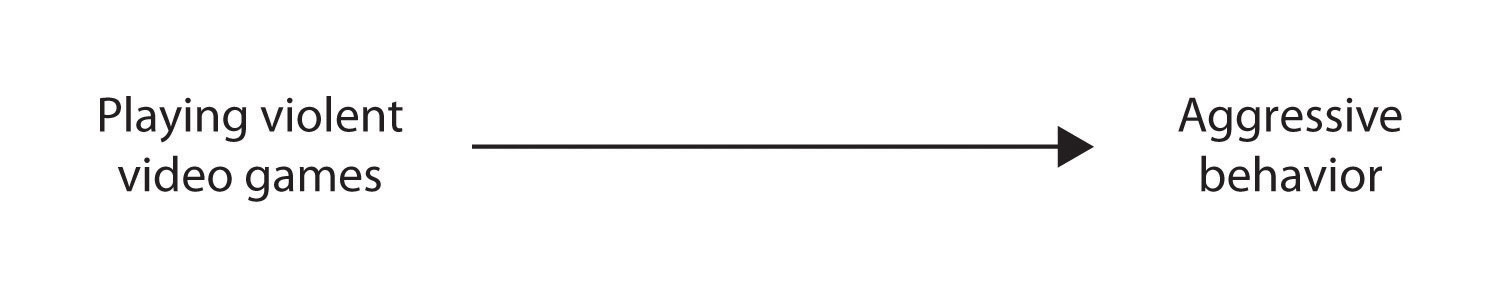

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

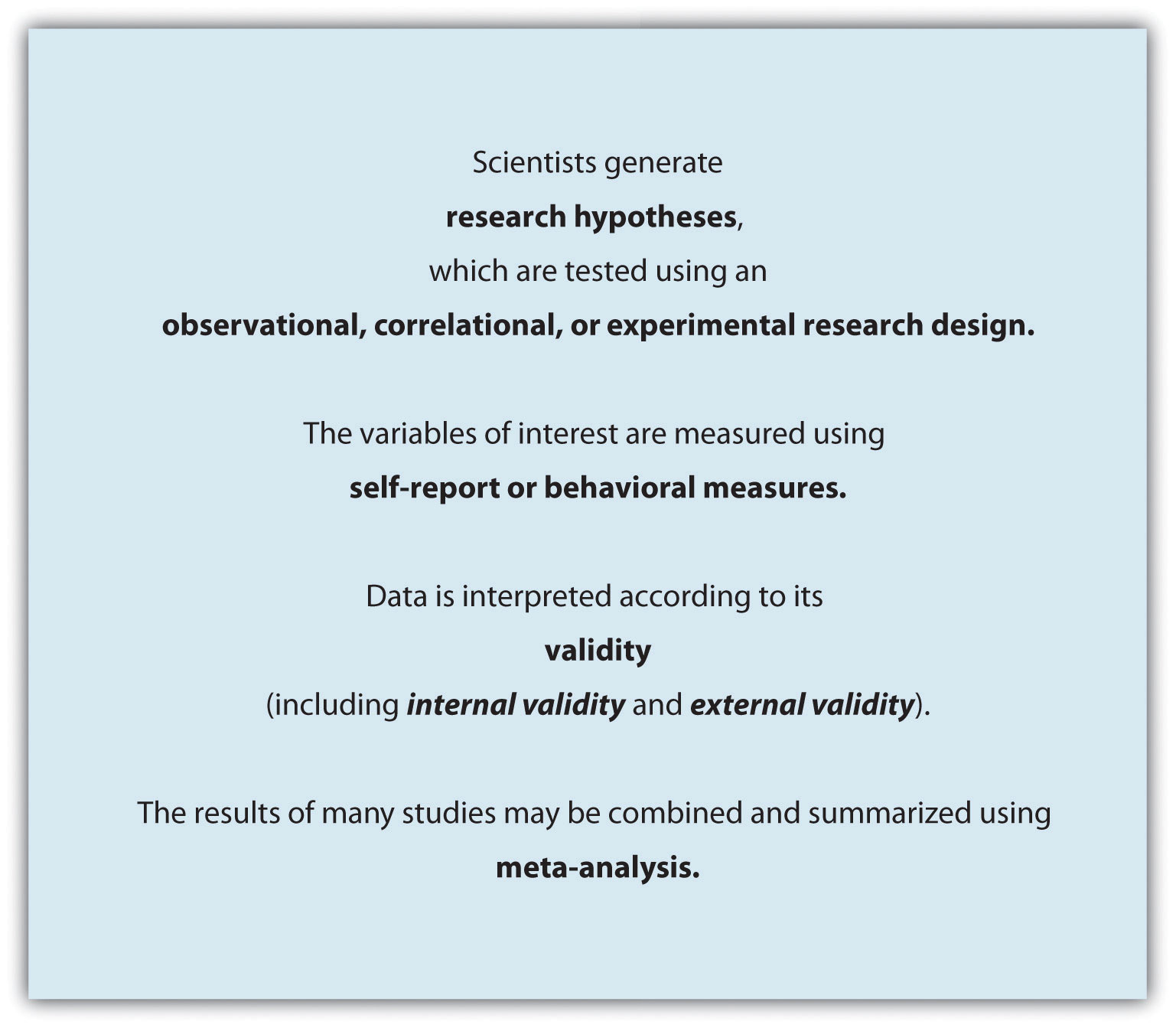

1.3 Conducting Research in Social Psychology

Learning objectives.

- Explain why social psychologists rely on empirical methods to study social behavior.

- Provide examples of how social psychologists measure the variables they are interested in.

- Review the three types of research designs, and evaluate the strengths and limitations of each type.

- Consider the role of validity in research, and describe how research programs should be evaluated.

Social psychologists are not the only people interested in understanding and predicting social behavior or the only people who study it. Social behavior is also considered by religious leaders, philosophers, politicians, novelists, and others, and it is a common topic on TV shows. But the social psychological approach to understanding social behavior goes beyond the mere observation of human actions. Social psychologists believe that a true understanding of the causes of social behavior can only be obtained through a systematic scientific approach, and that is why they conduct scientific research. Social psychologists believe that the study of social behavior should be empirical —that is, based on the collection and systematic analysis of observable data .

The Importance of Scientific Research

Because social psychology concerns the relationships among people, and because we can frequently find answers to questions about human behavior by using our own common sense or intuition, many people think that it is not necessary to study it empirically (Lilienfeld, 2011). But although we do learn about people by observing others and therefore social psychology is in fact partly common sense, social psychology is not entirely common sense.

In case you are not convinced about this, perhaps you would be willing to test whether or not social psychology is just common sense by taking a short true-or-false quiz. If so, please have a look at Table 1.1 “Is Social Psychology Just Common Sense?” and respond with either “True” or “False.” Based on your past observations of people’s behavior, along with your own common sense, you will likely have answers to each of the questions on the quiz. But how sure are you? Would you be willing to bet that all, or even most, of your answers have been shown to be correct by scientific research? Would you be willing to accept your score on this quiz for your final grade in this class? If you are like most of the students in my classes, you will get at least some of these answers wrong. (To see the answers and a brief description of the scientific research supporting each of these topics, please go to the Chapter Summary at the end of this chapter.)

Table 1.1 Is Social Psychology Just Common Sense?

| Answer each of the following questions, using your own initution, as either true or false. |

|---|

| Opposites attract. |

| An athlete who wins the bronze medal (third place) in an event is happier about his or her performance than the athlete who wins the silver medal (second place). |

| Having good friends you can count on can keep you from catching colds. |

| Subliminal advertising (i.e., persuasive messages that are displayed out of our awareness on TV or movie screens) is very effective in getting us to buy products. |

| The greater the reward promised for an activity, the more one will come to enjoy engaging in that activity. |

| Physically attractive people are seen as less intelligent than less attractive people. |

| Punching a pillow or screaming out loud is a good way to reduce frustration and aggressive tendencies. |

| People pull harder in a tug-of-war when they’re pulling alone than when pulling in a group. |

One of the reasons we might think that social psychology is common sense is that once we learn about the outcome of a given event (e.g., when we read about the results of a research project), we frequently believe that we would have been able to predict the outcome ahead of time. For instance, if half of a class of students is told that research concerning attraction between people has demonstrated that “opposites attract,” and if the other half is told that research has demonstrated that “birds of a feather flock together,” most of the students in both groups will report believing that the outcome is true and that they would have predicted the outcome before they had heard about it. Of course, both of these contradictory outcomes cannot be true. The problem is that just reading a description of research findings leads us to think of the many cases that we know that support the findings and thus makes them seem believable. The tendency to think that we could have predicted something that we probably would not have been able to predict is called the hindsight bias .

Our common sense also leads us to believe that we know why we engage in the behaviors that we engage in, when in fact we may not. Social psychologist Daniel Wegner and his colleagues have conducted a variety of studies showing that we do not always understand the causes of our own actions. When we think about a behavior before we engage in it, we believe that the thinking guided our behavior, even when it did not (Morewedge, Gray, & Wegner, 2010). People also report that they contribute more to solving a problem when they are led to believe that they have been working harder on it, even though the effort did not increase their contribution to the outcome (Preston & Wegner, 2007). These findings, and many others like them, demonstrate that our beliefs about the causes of social events, and even of our own actions, do not always match the true causes of those events.

Social psychologists conduct research because it often uncovers results that could not have been predicted ahead of time. Putting our hunches to the test exposes our ideas to scrutiny. The scientific approach brings a lot of surprises, but it also helps us test our explanations about behavior in a rigorous manner. It is important for you to understand the research methods used in psychology so that you can evaluate the validity of the research that you read about here, in other courses, and in your everyday life.

Social psychologists publish their research in scientific journals, and your instructor may require you to read some of these research articles. The most important social psychology journals are listed in Table 1.2 “Social Psychology Journals” . If you are asked to do a literature search on research in social psychology, you should look for articles from these journals.

Table 1.2 Social Psychology Journals

| The research articles in these journals are likely to be available in your college library. A fuller list can be found here: |

|---|

We’ll discuss the empirical approach and review the findings of many research projects throughout this book, but for now let’s take a look at the basics of how scientists use research to draw overall conclusions about social behavior. Keep in mind as you read this book, however, that although social psychologists are pretty good at understanding the causes of behavior, our predictions are a long way from perfect. We are not able to control the minds or the behaviors of others or to predict exactly what they will do in any given situation. Human behavior is complicated because people are complicated and because the social situations that they find themselves in every day are also complex. It is this complexity—at least for me—that makes studying people so interesting and fun.

Measuring Affect, Behavior, and Cognition

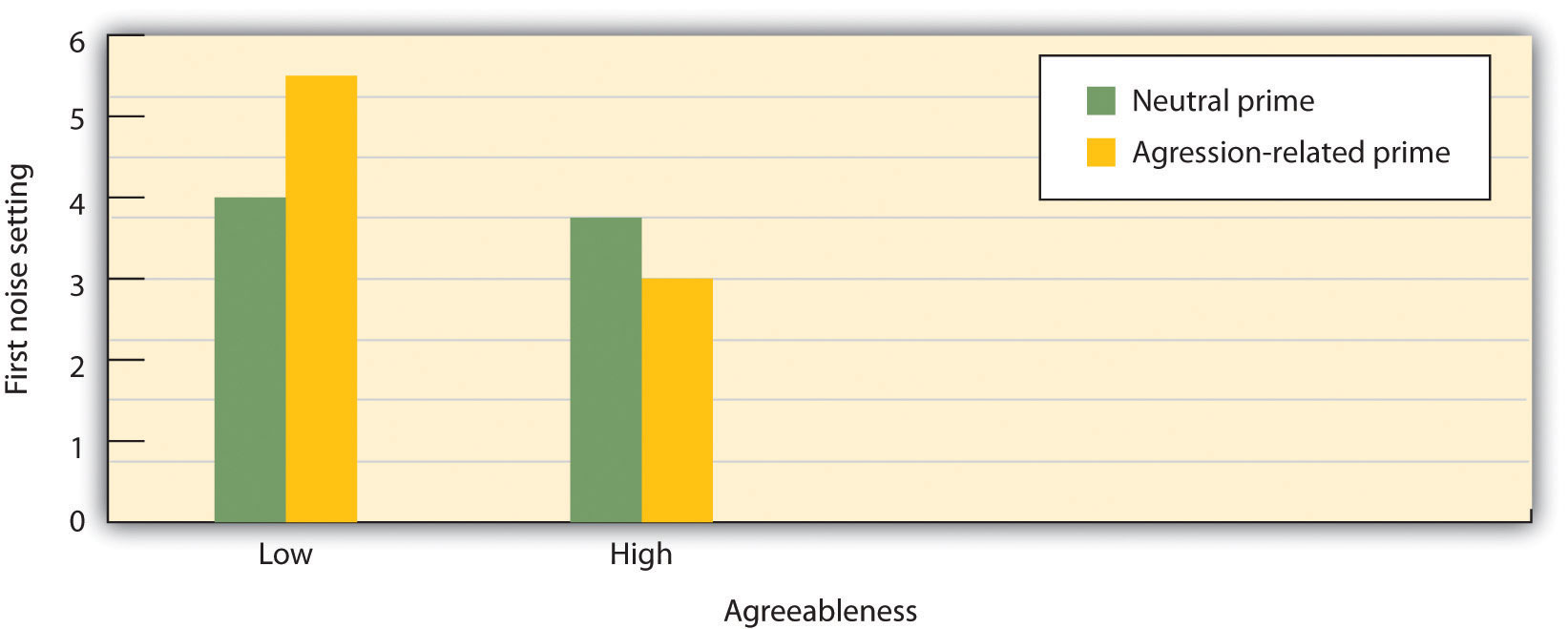

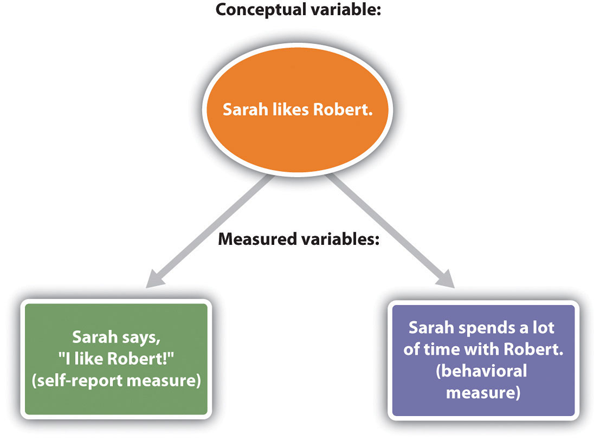

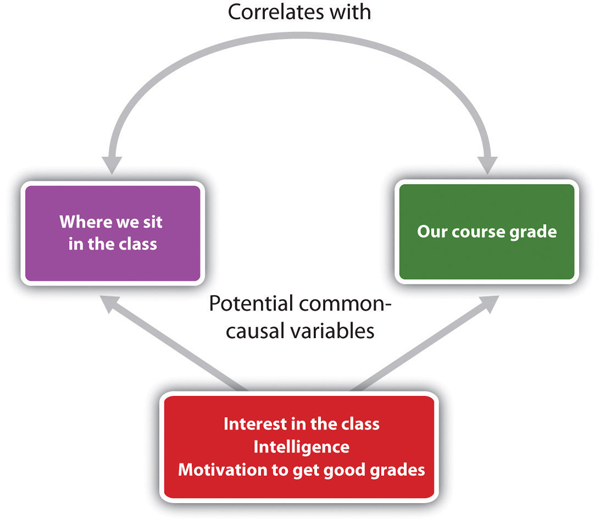

One important aspect of using an empirical approach to understand social behavior is that the concepts of interest must be measured ( Figure 1.4 “The Operational Definition” ). If we are interested in learning how much Sarah likes Robert, then we need to have a measure of her liking for him. But how, exactly, should we measure the broad idea of “liking”? In scientific terms, the characteristics that we are trying to measure are known as conceptual variables , and the particular method that we use to measure a variable of interest is called an operational definition .

For anything that we might wish to measure, there are many different operational definitions, and which one we use depends on the goal of the research and the type of situation we are studying. To better understand this, let’s look at an example of how we might operationally define “Sarah likes Robert.”

Figure 1.4 The Operational Definition

An idea or conceptual variable (such as “how much Sarah likes Robert”) is turned into a measure through an operational definition.

One approach to measurement involves directly asking people about their perceptions using self-report measures. Self-report measures are measures in which individuals are asked to respond to questions posed by an interviewer or on a questionnaire . Generally, because any one question might be misunderstood or answered incorrectly, in order to provide a better measure, more than one question is asked and the responses to the questions are averaged together. For example, an operational definition of Sarah’s liking for Robert might involve asking her to complete the following measure:

I enjoy being around Robert.

Strongly disagree 1 2 3 4 5 6 Strongly agree

I get along well with Robert.

I like Robert.

The operational definition would be the average of her responses across the three questions. Because each question assesses the attitude differently, and yet each question should nevertheless measure Sarah’s attitude toward Robert in some way, the average of the three questions will generally be a better measure than would any one question on its own.

Although it is easy to ask many questions on self-report measures, these measures have a potential disadvantage. As we have seen, people’s insights into their own opinions and their own behaviors may not be perfect, and they might also not want to tell the truth—perhaps Sarah really likes Robert, but she is unwilling or unable to tell us so. Therefore, an alternative to self-report that can sometimes provide a more valid measure is to measure behavior itself. Behavioral measures are measures designed to directly assess what people do . Instead of asking Sara how much she likes Robert, we might instead measure her liking by assessing how much time she spends with Robert or by coding how much she smiles at him when she talks to him. Some examples of behavioral measures that have been used in social psychological research are shown in Table 1.3 “Examples of Operational Definitions of Conceptual Variables That Have Been Used in Social Psychological Research” .

Table 1.3 Examples of Operational Definitions of Conceptual Variables That Have Been Used in Social Psychological Research

| Conceptual variable | Operational definitions |

|---|---|

| Aggression | • Number of presses of a button that administers shock to another student |

| • Number of seconds taken to honk the horn at the car ahead after a stoplight turns green | |

| Interpersonal attraction | • Number of times that a person looks at another person |

| • Number of millimeters of pupil dilation when one person looks at another | |

| Altruism | • Number of pieces of paper a person helps another pick up |

| • Number of hours of volunteering per week that a person engages in | |

| Group decision-making skills | • Number of groups able to correctly solve a group performance task |

| • Number of seconds in which a group correctly solves a problem | |

| Prejudice | • Number of negative words used in a creative story about another person |

| • Number of inches that a person places their chair away from another person |

Social Neuroscience: Measuring Social Responses in the Brain

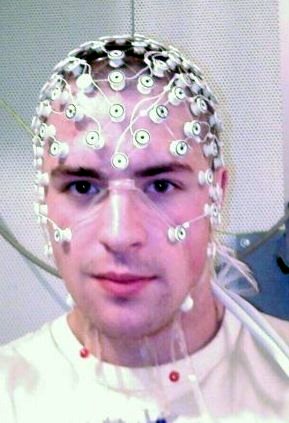

Still another approach to measuring our thoughts and feelings is to measure brain activity, and recent advances in brain science have created a wide variety of new techniques for doing so. One approach, known as electroencephalography (EEG) , is a technique that records the electrical activity produced by the brain’s neurons through the use of electrodes that are placed around the research participant’s head . An electroencephalogram (EEG) can show if a person is asleep, awake, or anesthetized because the brain wave patterns are known to differ during each state. An EEG can also track the waves that are produced when a person is reading, writing, and speaking with others. A particular advantage of the technique is that the participant can move around while the recordings are being taken, which is useful when measuring brain activity in children who often have difficulty keeping still. Furthermore, by following electrical impulses across the surface of the brain, researchers can observe changes over very fast time periods.

This woman is wearing an EEG cap.

goocy – Research – CC BY-NC 2.0.

Although EEGs can provide information about the general patterns of electrical activity within the brain, and although they allow the researcher to see these changes quickly as they occur in real time, the electrodes must be placed on the surface of the skull, and each electrode measures brain waves from large areas of the brain. As a result, EEGs do not provide a very clear picture of the structure of the brain.

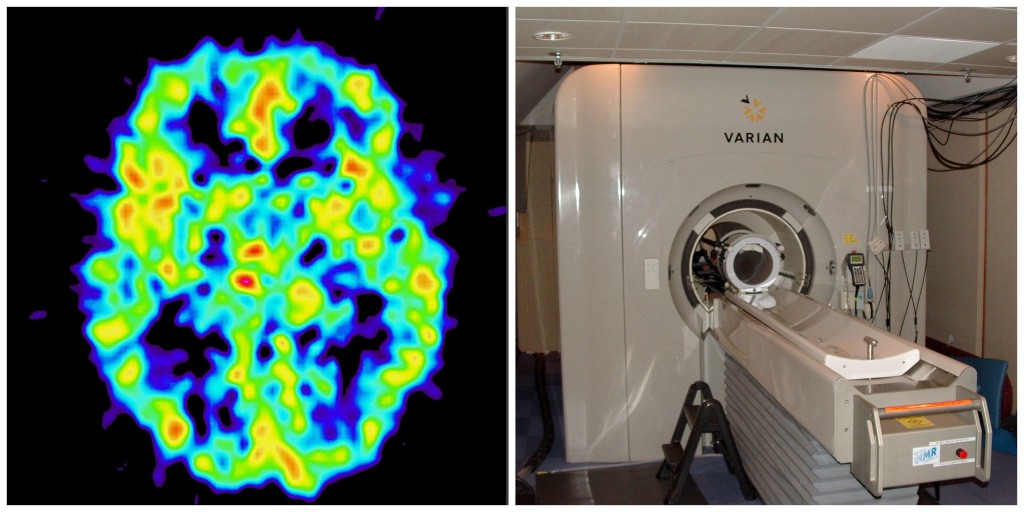

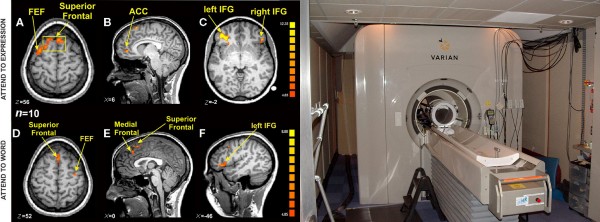

But techniques exist to provide more specific brain images. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) is a neuroimaging technique that uses a magnetic field to create images of brain structure and function . In research studies that use the fMRI, the research participant lies on a bed within a large cylindrical structure containing a very strong magnet. Nerve cells in the brain that are active use more oxygen, and the need for oxygen increases blood flow to the area. The fMRI detects the amount of blood flow in each brain region and thus is an indicator of which parts of the brain are active.

Very clear and detailed pictures of brain structures (see Figure 1.5 “Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)” ) can be produced via fMRI. Often, the images take the form of cross-sectional “slices” that are obtained as the magnetic field is passed across the brain. The images of these slices are taken repeatedly and are superimposed on images of the brain structure itself to show how activity changes in different brain structures over time. Normally, the research participant is asked to engage in tasks while in the scanner, for instance, to make judgments about pictures of people, to solve problems, or to make decisions about appropriate behaviors. The fMRI images show which parts of the brain are associated with which types of tasks. Another advantage of the fMRI is that is it noninvasive. The research participant simply enters the machine and the scans begin.

Figure 1.5 Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI)

The fMRI creates images of brain structure and activity. In this image, the red and yellow areas represent increased blood flow and thus increased activity.

Reigh LeBlanc – Reigh’s Brain rlwat – CC BY-NC 2.0; Wikimedia Commons – public domain.

Although the scanners themselves are expensive, the advantages of fMRIs are substantial, and scanners are now available in many university and hospital settings. The fMRI is now the most commonly used method of learning about brain structure, and it has been employed by social psychologists to study social cognition, attitudes, morality, emotions, responses to being rejected by others, and racial prejudice, to name just a few topics (Eisenberger, Lieberman, & Williams, 2003; Greene, Sommerville, Nystrom, Darley, & Cohen, 2001; Lieberman, Hariri, Jarcho, Eisenberger, & Bookheimer, 2005; Ochsner, Bunge, Gross, & Gabrieli, 2002; Richeson et al., 2003).

Observational Research

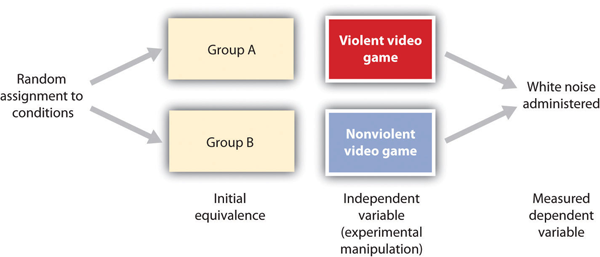

Once we have decided how to measure our variables, we can begin the process of research itself. As you can see in Table 1.4 “Three Major Research Designs Used by Social Psychologists” , there are three major approaches to conducting research that are used by social psychologists—the observational approach , the correlational approach , and the experimental approach . Each approach has some advantages and disadvantages.

Table 1.4 Three Major Research Designs Used by Social Psychologists

| Research Design | Goal | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observational | To create a snapshot of the current state of affairs | Provides a relatively complete picture of what is occurring at a given time. Allows the development of questions for further study. | Does not assess relationships between variables. |

| Correlational | To assess the relationships between two or more variables | Allows the testing of expected relationships between variables and the making of predictions. Can assess these relationships in everyday life events. | Cannot be used to draw inferences about the causal relationships between the variables. |

| Experimental | To assess the causal impact of one or more experimental manipulations on a dependent variable | Allows the drawing of conclusions about the causal relationships among variables. | Cannot experimentally manipulate many important variables. May be expensive and take much time to conduct. |

The most basic research design, observational research , is research that involves making observations of behavior and recording those observations in an objective manner . Although it is possible in some cases to use observational data to draw conclusions about the relationships between variables (e.g., by comparing the behaviors of older versus younger children on a playground), in many cases the observational approach is used only to get a picture of what is happening to a given set of people at a given time and how they are responding to the social situation. In these cases, the observational approach involves creating a type of “snapshot” of the current state of affairs.