DigitalCommons@UNMC

Home > Eppley Institute > Theses & Dissertations

Theses & Dissertations: Cancer Research

Theses/dissertations from 2023 2023.

Development of Combination Therapy Strategies to Treat Cancer Using Dihydroorotate Dehydrogenase Inhibitors , Nicholas Mullen

Overcoming Resistance Mechanisms to CDK4/6 Inhibitor Treatment Using CDK6-Selective PROTAC , Sarah Truong

Theses/Dissertations from 2022 2022

Omics Analysis in Cancer and Development , Emalie J. Clement

Investigating the Role of Splenic Macrophages in Pancreatic Cancer , Daisy V. Gonzalez

Polymeric Chloroquine in Metastatic Pancreatic Cancer Therapy , Rubayat Islam Khan

Evaluating Targets and Therapeutics for the Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer , Shelby M. Knoche

Characterization of 1,1-Diarylethylene FOXM1 Inhibitors Against High-Grade Serous Ovarian Carcinoma Cells , Cassie Liu

Novel Mechanisms of Protein Kinase C α Regulation and Function , Xinyue Li

SOX2 Dosage Governs Tumor Cell Identity and Proliferation , Ethan P. Metz

Post-Transcriptional Control of the Epithelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition (EMT) in Ras-Driven Colorectal Cancers , Chaitra Rao

Use of Machine Learning Algorithms and Highly Multiplexed Immunohistochemistry to Perform In-Depth Characterization of Primary Pancreatic Tumors and Metastatic Sites , Krysten Vance

Characterization of Metastatic Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma in the Immunosuppressed Patient , Megan E. Wackel

Visceral adipose tissue remodeling in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma cachexia: the role of activin A signaling , Pauline Xu

Phos-Tag-Based Screens Identify Novel Therapeutic Targets in Ovarian Cancer and Pancreatic Cancer , Renya Zeng

Theses/Dissertations from 2021 2021

Functional Characterization of Cancer-Associated DNA Polymerase ε Variants , Stephanie R. Barbari

Pancreatic Cancer: Novel Therapy, Research Tools, and Educational Outreach , Ayrianne J. Crawford

Apixaban to Prevent Thrombosis in Adult Patients Treated With Asparaginase , Krishna Gundabolu

Molecular Investigation into the Biologic and Prognostic Elements of Peripheral T-cell Lymphoma with Regulators of Tumor Microenvironment Signaling Explored in Model Systems , Tyler Herek

Utilizing Proteolysis-Targeting Chimeras to Target the Transcriptional Cyclin-Dependent Kinases 9 and 12 , Hannah King

Insights into Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma Pathogenesis and Metastasis Using a Bedside-to-Bench Approach , Marissa Lobl

Development of a MUC16-Targeted Near-Infrared Antibody Probe for Fluorescence-Guided Surgery of Pancreatic Cancer , Madeline T. Olson

FGFR4 glycosylation and processing in cholangiocarcinoma promote cancer signaling , Andrew J. Phillips

Theses/Dissertations from 2020 2020

Cooperativity of CCNE1 and FOXM1 in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer , Lucy Elge

Characterizing the critical role of metabolic and redox homeostasis in colorectal cancer , Danielle Frodyma

Genomic and Transcriptomic Alterations in Metabolic Regulators and Implications for Anti-tumoral Immune Response , Ryan J. King

Dimers of Isatin Derived Spirocyclic NF-κB Inhibitor Exhibit Potent Anticancer Activity by Inducing UPR Mediated Apoptosis , Smit Kour

From Development to Therapy: A Panoramic Approach to Further Our Understanding of Cancer , Brittany Poelaert

The Cellular Origin and Molecular Drivers of Claudin-Low Mammary Cancer , Patrick D. Raedler

Mitochondrial Metabolism as a Therapeutic Target for Pancreatic Cancer , Simon Shin

Development of Fluorescent Hyaluronic Acid Nanoparticles for Intraoperative Tumor Detection , Nicholas E. Wojtynek

Theses/Dissertations from 2019 2019

The role of E3 ubiquitin ligase FBXO9 in normal and malignant hematopoiesis , R. Willow Hynes-Smith

BRCA1 & CTDP1 BRCT Domainomics in the DNA Damage Response , Kimiko L. Krieger

Targeted Inhibition of Histone Deacetyltransferases for Pancreatic Cancer Therapy , Richard Laschanzky

Human Leukocyte Antigen (HLA) Class I Molecule Components and Amyloid Precursor-Like Protein 2 (APLP2): Roles in Pancreatic Cancer Cell Migration , Bailee Sliker

Theses/Dissertations from 2018 2018

FOXM1 Expression and Contribution to Genomic Instability and Chemoresistance in High-Grade Serous Ovarian Cancer , Carter J. Barger

Overcoming TCF4-Driven BCR Signaling in Diffuse Large B-Cell Lymphoma , Keenan Hartert

Functional Role of Protein Kinase C Alpha in Endometrial Carcinogenesis , Alice Hsu

Functional Signature Ontology-Based Identification and Validation of Novel Therapeutic Targets and Natural Products for the Treatment of Cancer , Beth Neilsen

Elucidating the Roles of Lunatic Fringe in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma , Prathamesh Patil

Theses/Dissertations from 2017 2017

Metabolic Reprogramming of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Cells in Response to Chronic Low pH Stress , Jaime Abrego

Understanding the Relationship between TGF-Beta and IGF-1R Signaling in Colorectal Cancer , Katie L. Bailey

The Role of EHD2 in Triple-Negative Breast Cancer Tumorigenesis and Progression , Timothy A. Bielecki

Perturbing anti-apoptotic proteins to develop novel cancer therapies , Jacob Contreras

Role of Ezrin in Colorectal Cancer Cell Survival Regulation , Premila Leiphrakpam

Evaluation of Aminopyrazole Analogs as Cyclin-Dependent Kinase Inhibitors for Colorectal Cancer Therapy , Caroline Robb

Identifying the Role of Janus Kinase 1 in Mammary Gland Development and Breast Cancer , Barbara Swenson

DNMT3A Haploinsufficiency Provokes Hematologic Malignancy of B-Lymphoid, T-Lymphoid, and Myeloid Lineage in Mice , Garland Michael Upchurch

Theses/Dissertations from 2016 2016

EHD1 As a Positive Regulator of Macrophage Colony-Stimulating Factor-1 Receptor , Luke R. Cypher

Inflammation- and Cancer-Associated Neurolymphatic Remodeling and Cachexia in Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma , Darci M. Fink

Role of CBL-family Ubiquitin Ligases as Critical Negative Regulators of T Cell Activation and Functions , Benjamin Goetz

Exploration into the Functional Impact of MUC1 on the Formation and Regulation of Transcriptional Complexes Containing AP-1 and p53 , Ryan L. Hanson

DNA Polymerase Zeta-Dependent Mutagenesis: Molecular Specificity, Extent of Error-Prone Synthesis, and the Role of dNTP Pools , Olga V. Kochenova

Defining the Role of Phosphorylation and Dephosphorylation in the Regulation of Gap Junction Proteins , Hanjun Li

Molecular Mechanisms Regulating MYC and PGC1β Expression in Colon Cancer , Jamie L. McCall

Pancreatic Cancer Invasion of the Lymphatic Vasculature and Contributions of the Tumor Microenvironment: Roles for E-selectin and CXCR4 , Maria M. Steele

Altered Levels of SOX2, and Its Associated Protein Musashi2, Disrupt Critical Cell Functions in Cancer and Embryonic Stem Cells , Erin L. Wuebben

Theses/Dissertations from 2015 2015

Characterization and target identification of non-toxic IKKβ inhibitors for anticancer therapy , Elizabeth Blowers

Effectors of Ras and KSR1 dependent colon tumorigenesis , Binita Das

Characterization of cancer-associated DNA polymerase delta variants , Tony M. Mertz

A Role for EHD Family Endocytic Regulators in Endothelial Biology , Alexandra E. J. Moffitt

Biochemical pathways regulating mammary epithelial cell homeostasis and differentiation , Chandrani Mukhopadhyay

EPACs: epigenetic regulators that affect cell survival in cancer. , Catherine Murari

Role of the C-terminus of the Catalytic Subunit of Translesion Synthesis Polymerase ζ (Zeta) in UV-induced Mutagensis , Hollie M. Siebler

LGR5 Activates TGFbeta Signaling and Suppresses Metastasis in Colon Cancer , Xiaolin Zhou

LGR5 Activates TGFβ Signaling and Suppresses Metastasis in Colon Cancer , Xiaolin Zhou

Theses/Dissertations from 2014 2014

Genetic dissection of the role of CBL-family ubiquitin ligases and their associated adapters in epidermal growth factor receptor endocytosis , Gulzar Ahmad

Strategies for the identification of chemical probes to study signaling pathways , Jamie Leigh Arnst

Defining the mechanism of signaling through the C-terminus of MUC1 , Roger B. Brown

Targeting telomerase in human pancreatic cancer cells , Katrina Burchett

The identification of KSR1-like molecules in ras-addicted colorectal cancer cells , Drew Gehring

Mechanisms of regulation of AID APOBEC deaminases activity and protection of the genome from promiscuous deamination , Artem Georgievich Lada

Characterization of the DNA-biding properties of human telomeric proteins , Amanda Lakamp-Hawley

Studies on MUC1, p120-catenin, Kaiso: coordinate role of mucins, cell adhesion molecules and cell cycle players in pancreatic cancer , Xiang Liu

Epac interaction with the TGFbeta PKA pathway to regulate cell survival in colon cancer , Meghan Lynn Mendick

Theses/Dissertations from 2013 2013

Deconvolution of the phosphorylation patterns of replication protein A by the DNA damage response to breaks , Kerry D. Brader

Modeling malignant breast cancer occurrence and survival in black and white women , Michael Gleason

The role of dna methyltransferases in myc-induced lymphomagenesis , Ryan A. Hlady

Design and development of inhibitors of CBL (TKB)-protein interactions , Eric A. Kumar

Pancreatic cancer-associated miRNAs : expression, regulation and function , Ashley M. Mohr

Mechanistic studies of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization (MOMP) , Xiaming Pang

Novel roles for JAK2/STAT5 signaling in mammary gland development, cancer, and immune dysregulation , Jeffrey Wayne Schmidt

Optimization of therapeutics against lethal pancreatic cancer , Joshua J. Souchek

Theses/Dissertations from 2012 2012

Immune-based novel diagnostic mechanisms for pancreatic cancer , Michael J. Baine

Sox2 associated proteins are essential for cell fate , Jesse Lee Cox

KSR2 regulates cellular proliferation, transformation, and metabolism , Mario R. Fernandez

Discovery of a novel signaling cross-talk between TPX2 and the aurora kinases during mitosis , Jyoti Iyer

Regulation of metabolism by KSR proteins , Paula Jean Klutho

The role of ERK 1/2 signaling in the dna damage-induced G2 , Ryan Kolb

Regulation of the Bcl-2 family network during apoptosis induced by different stimuli , Hernando Lopez

Studies on the role of cullin3 in mitosis , Saili Moghe

Characteristics of amyloid precursor-like protein 2 (APLP2) in pancreatic cancer and Ewing's sarcoma , Haley Louise Capek Peters

Structural and biophysical analysis of a human inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase polymorphism , Peter David Simone

Functions and regulation of Ron receptor tyrosine kinase in human pancreatic cancer and its therapeutic applications , Yi Zou

Theses/Dissertations from 2011 2011

Coordinate detection of new targets and small molecules for cancer therapy , Kurt Fisher

The role of c-Myc in pancreatic cancer initiation and progression , Wan-Chi Lin

The role of inosine triphosphate pyrophosphatase (ITPA) in maintanence [sic] of genomic stability in human cells , Miriam-Rose Menezes

Molecular insights into major histocompatibility complex class I folding and assembly , Laura Christina Simone

The role of bcl-2 in colon cancer metastatic progression , Wang Wang

A rational peptidomimetic approach towards generation of high affinity BRCT (BRCA1) inhibitors , Ziyan Yuan

D-type cyclins and breast cancer , Quian Zhang

- Eppley Institute Website

- McGoogan Library

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Ovarian Cancer Treatment Decisions: Accessing Gynecologic Oncology Care

Add to collection, downloadable content.

- March 20, 2019

- Affiliation: Gillings School of Global Public Health, Department of Health Policy and Management

- Ovarian cancer is the most fatal gynecologic malignancy and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related deaths among women in the U.S (USCS 2015). The majority (>80%) of women is diagnosed at late stages (III or IV), often when the prognosis is poor and the 5-year survival rate is 37-45% (Howlader et al. 2015; USCS 2015). Poor prognosis has been attributed to a lack of an early detection strategy, lack of access of specialist care, variations in surgical and chemotherapeutic treatment and patient variability in uptake, as well as healthcare systems characteristics that may contribute to variable quality of care and delays (Bristow et al. 2014b; Carney et al. 2002; Cliby et al. 2015; Thrall et al. 2011). While earlier research efforts have shown treatment from a gynecologic oncologist (GO) to be associated with improved survival, studies have suggested that a substantial number of women with ovarian cancer still do not receive care from a GO at any point during their care (Vernooij et al. 2007). Less is known about when women are accessing the care from a GO (i.e. preoperative/consult only, intraoperatively, postoperatively, or continuous involvement at all phases) and how accessing a GO at different phases of care (i.e. timing) impacts survival. Furthermore, gaps still exist in the literature on the role of a patient’s psychosocial experience and voice in ovarian cancer care (Erwin 2010; Herzog et al. 2014). The overall objective of this research was to understand the effect of timing of GO involvement on mortality (Aim 1 and 2) and explore the patient-level preferences and roles around decision-making and decisional self-efficacy among women with ovarian cancer (Aim 3). Through use of cancer registries supplemented with medical record abstraction (n=2,162) and survey data (n=170), this research examined different aspects around when and where ovarian cancer patients accessed a GO and among those largely seen by a GO, we explored patient-centered factors associated with having greater decisional efficacy and/or decisional support needs. Based on our findings, differences in GO involvement were evident by patient age, race, and place of care. The patient’s perception of a GO as the most important physician in treatment decisions about care did not affect decisional efficacy, but other psychosocial domains did. Though our results likely reflects the confluence of clinical management processes, patient- and provider treatment preferences, and the complexities of the patient-provider clinical interaction that determine the extent of care, it underscores the importance of further examining equitable care delivery to all subgroups of women, particularly those whom may be vulnerable to decisional support needs. We expect that our research findings will help future efforts to identify, understand, and implement interventions to improve receipt of continuous, quality care associated with increased survival and consistent with patient needs.

- decision-making

- Public health

- ovarian cancer

- https://doi.org/10.17615/65y5-z206

- Dissertation

- In Copyright

- Wheeler, Stephanie

- Reeve, Bryce

- Hall, Ingrid

- Brewster, Wendy

- Bennett, Antonia

- Doctor of Philosophy

- University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Graduate School

This work has no parents.

Select type of work

Master's papers.

Deposit your masters paper, project or other capstone work. Theses will be sent to the CDR automatically via ProQuest and do not need to be deposited.

Scholarly Articles and Book Chapters

Deposit a peer-reviewed article or book chapter. If you would like to deposit a poster, presentation, conference paper or white paper, use the “Scholarly Works” deposit form.

Undergraduate Honors Theses

Deposit your senior honors thesis.

Scholarly Journal, Newsletter or Book

Deposit a complete issue of a scholarly journal, newsletter or book. If you would like to deposit an article or book chapter, use the “Scholarly Articles and Book Chapters” deposit option.

Deposit your dataset. Datasets may be associated with an article or deposited separately.

Deposit your 3D objects, audio, images or video.

Poster, Presentation, Protocol or Paper

Deposit scholarly works such as posters, presentations, research protocols, conference papers or white papers. If you would like to deposit a peer-reviewed article or book chapter, use the “Scholarly Articles and Book Chapters” deposit option.

Ovarian Cancer: An Integrated Review

Affiliations.

- 1 Carolina's Medical Center, Charlotte, NC. Electronic address: [email protected].

- 2 Assistant Vice President Patient Care Services, Carolina's Medical Center, Rock Hill, SC.

- 3 Interim Dean, Harris College of Nursing & Health Sciences, Associate Dean for Nursing & Professor, Texas Christian University, Ft Worth, TX.

- PMID: 30867104

- DOI: 10.1016/j.soncn.2019.02.001

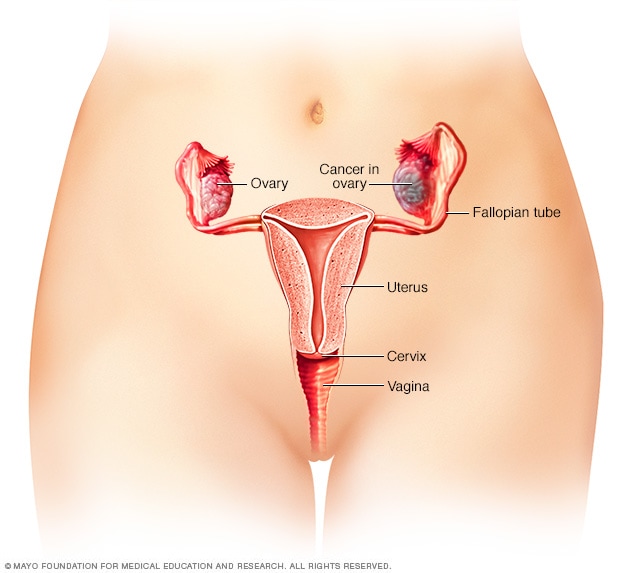

Objective: To provide an overview of the risk factors, modifiable and non-modifiable, for ovarian cancer as well as prevention, diagnostic, treatment, and long-term survivorship concerns. This article will also examine current and future clinical trials surrounding ovarian cancer.

Data sources: A review of articles dated 2006-2018 from CINAHL, UpToDate, and National Comprehensive Cancer Network guidelines.

Conclusion: There is no screening test for ovarian cancer and with diagnosis often in the late stages, recurrence is high in this population. Early identification can range from knowing the vague symptoms associated with the cancer to prophylactic surgical removal of at-risk tissue. Standard treatment for ovarian cancer is surgery followed by combination chemotherapy. Although advances are being made, ovarian cancer remains the most fatal female gynecologic cancer.

Implications for nursing practice: Becoming familiar with and educating women about risk factors and the elusive symptoms of ovarian cancer can increase patient autonomy and advocacy, as well as potentially improve patient outcomes for those affected by ovarian cancer.

Keywords: BRCA; gynecologic; oncology; ovarian cancer; prevention; risk factors.

Copyright © 2019 Elsevier Inc. All rights reserved.

Publication types

- Ovarian Neoplasms / diagnosis

- Ovarian Neoplasms / epidemiology*

- Ovarian Neoplasms / prevention & control

- Ovarian Neoplasms / therapy

- Risk Factors

Ovarian Cancers: Evolving Paradigms in Research and Care (2016)

Chapter: 1 introduction and background.

Introduction and Background

Although recent years have seen many promising advances in cancer research, there remain surprising gaps in the fundamental knowledge about and understanding of ovarian cancer. Researchers now know that ovarian cancer, like many other types of cancer, should not be thought of as a single disease; instead, several distinct subtypes exist with different origins, different risk factors, different genetic mutations, different biological behaviors, and different prognoses, and much remains to be learned about them. For example, researchers do not have definitive knowledge of exactly where these various ovarian cancers originate and how they develop. Such unanswered questions have impeded progress in the prevention, early detection, treatment, and management of ovarian cancers. In particular, the failure to achieve major reductions in ovarian cancer morbidity and mortality during the past several decades is likely due to several factors, including

- A lack of research focusing on specific disease subtypes;

- An incomplete understanding of genetic and nongenetic risk factors;

- An inability to develop and validate effective screening and early detection tools;

- Inconsistency in the delivery of the standard of care;

- Limited evidence-based personalized medicine approaches tailored to the disease subtypes and other tumor characteristics; and

- Limited attention paid to research on survivorship issues, including supportive care with long-term management of active disease.

The symptoms of ovarian cancers can be nonspecific and are often not seen as indicating a serious illness by women or their health care providers until the symptoms worsen, at which point the cancer may be widespread and difficult to cure. The fact that these cancers are not diagnosed in many women until they are at an advanced stage is a major factor contributing to the high mortality rate for ovarian cancer, especially for women with high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC)—the most common and lethal subtype. Indeed, roughly two-thirds of women with ovarian cancer are diagnosed with an advanced-stage cancer or with a cancer that has not been definitively staged, and the 5-year survival rate for these women is less than 30 percent (Howlader et al., 2015). Although many ovarian cancers respond well to initial treatment, including the surgical removal of grossly visible tumor (cytoreduction) and chemotherapy, the vast majority of the tumors recur. Recurrent ovarian cancers may again respond to further treatment, but virtually all of them will ultimately become resistant to current drug therapies.

Finally, less emphasis has been placed on research that focuses on how to improve therapeutic interventions by subtype or on how to reduce the morbidity of ovarian cancers. Little emphasis has been placed on understanding survivorship issues and the supportive care needs of women with ovarian cancer, including management of the physical side effects of treatment (including both initial and chronic, ongoing therapies) and addressing the psychosocial effects of diagnosis and treatment. The lasting impact of a diagnosis of ovarian cancer and its related treatment can be significant both for the women who experience recurrent disease and for the women who experience long (or indefinite) periods of remission. This report gives an overview of the state of the science in ovarian cancer research, highlights the major gaps in knowledge in that field, and provides recommendations that might help reduce the incidence of and morbidity and mortality from ovarian cancers by focusing on promising research themes and technologies that could advance risk prediction, early detection, comprehensive care, and cure.

STUDY CHARGE AND APPROACH

In spite of their high mortality rates, ovarian cancers often do not receive as much attention as other cancers. In part, this is because ovarian cancers are relatively uncommon. Furthermore, ovarian cancer has been called a “silent killer” because researchers once believed that there were no perceptible symptoms in the earlier stages of the disease (Goff, 2012). However, more recent research has shown that most women diagnosed with ovarian cancer report symptoms such as bloating, pelvic or abdominal pain, and urinary symptoms, and many women recall having these symptoms

for an extended period of time before diagnosis (Goff et al., 2000, 2004). Often, due to the nonspecific nature of ovarian cancer symptoms, patients and physicians do not recognize these early symptoms as indicative of ovarian cancer (Gajjar et al., 2012; Jones et al., 2010; Lockwood-Rayermann et al., 2009).

In this context, in 2006 the U.S. Congress passed the Gynecologic Cancer Education and Awareness Act of 2005, 1 which amended the Public Health Service Act (42 U.S.C. 247b-17) to direct the secretary of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to launch a campaign to “increase the awareness and knowledge of health care providers and women with respect to gynecologic cancers.” The law is commonly known as Johanna’s Law in memory of Johanna Silver Gordon, a public school teacher from Michigan who died from late-stage ovarian cancer (Twombly, 2007). The law was reauthorized in 2010, 2 and, as part of the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2014, Congress directed the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to use funds from Johanna’s Law to perform a review of the state of the science in ovarian cancer. 3

Study Charge

In the fall of 2014, with support from the CDC, the Institute of Medicine (IOM) formed the Committee on the State of the Science in Ovarian Cancer Research to examine and summarize the state of the science in ovarian cancer research, to identify key gaps in the evidence base and challenges to addressing those gaps, and to consider opportunities for advancing ovarian cancer research (see Box 1-1 ). The committee determined that the best way to facilitate progress in reducing morbidity and mortality would be to identify the research gaps that were most salient and that, if addressed, could affect the greatest number of women.

The committee was also asked to consider ways to translate and disseminate new findings and to communicate these findings to all stakeholders. This report, therefore, not only describes evidence-based approaches to translation and dissemination, but it also suggests strategies for communicating those approaches.

________________

1 Gynecologic Cancer Education and Awareness Act of 2005, Public Law 475, 109th Cong., 2nd sess. (January 12, 2007).

2 To reauthorize and enhance Johanna’s Law to increase public awareness and knowledge with respect to gynecologic cancers, Public Law 324, 111th Cong., 2nd sess. (December 22, 2010).

3 Explanatory statement submitted by Mr. Rogers of Kentucky, Chairman of the House Committee on Appropriations regarding the House amendment to the Senate amendment on H.R. 3547, consolidated... , 113th Cong., 2nd sess., Congressional Record 160, no. 9, daily ed. (January 15, 2014):H 1035.

BOX 1-1 Statement of Task

An ad hoc committee under the auspices of the Institute of Medicine will review the state of the science in ovarian cancer research and formulate recommendations for action to advance the field. The committee will:

- Summarize and examine the state of the science in ovarian cancer research;

- Identify key gaps in the evidence base and the challenges to addressing those gaps;

- Consider opportunities for advancing ovarian cancer research; and

- Examine avenues for translation and dissemination of new findings and communication of new information to patients and others.

The committee will make recommendations for public- and private-sector efforts that could facilitate progress in reducing the incidence of and morbidity and mortality from ovarian cancer.

The committee emphasizes that its charge was to focus on research in ovarian cancer and, particularly, to focus on the gaps in the evidence base that, if addressed, would have the greatest impact on the lives of women diagnosed with or at risk for ovarian cancer. The committee did not explore issues affecting the care of women with ovarian cancer (e.g., health insurance coverage and policy issues) in depth. For example, while the regulatory process for drug approval is interconnected with the clinical trial enterprise (e.g., the design of clinical trials may determine what data are gathered and, in turn, affect the approval process), a full examination of issues related to the approval of new drugs was beyond the scope of this report. Furthermore, it was outside the scope of this report to fully evaluate specific research programs in ovarian cancer. In addition, this report does not offer an exhaustive cataloguing of every actor engaged in ovarian cancer research, nor does it detail every effort made by stakeholders to engage in dissemination and implementation efforts. Rather, the examples given in this report are meant to highlight the efforts being made, recognizing there are many other similar efforts.

Finally, the committee focused as much as possible on the research gaps and the challenges to addressing those gaps that are unique to ovarian cancer. However, those research gaps and challenges that are common to all types of cancer research, or even to all health care research, are described as appropriate. For example, while the clinical trials system is extremely important to the ovarian cancer research enterprise, many of the outstanding

questions and concerns related to the clinical trials system are shared with all types of cancer research and could not be explored or discussed in detail. Therefore, the committee turned to previous IOM reports specific to the clinical trials system in general for guidance, and then considered aspects of the system that are particularly relevant for ovarian cancer research.

Study Approach

The study committee included 15 members with expertise in ovarian cancer, gynecologic oncology, gynecologic pathology, gynecologic surgery, molecular biology, cancer genetics and genomics, genetic counseling, cancer epidemiology, immunology, biostatistics, bioethics, advocacy, survivorship, and health communication. (See Appendix E for biographies of the committee members.)

A variety of sources informed the committee’s work. The committee met in person four times, and during two of those meetings it held public sessions to obtain input from a broad range of relevant stakeholders. In addition, the committee conducted extensive literature reviews, reached out to a variety of public and private stakeholders, and commissioned one paper.

The committee encountered a number of challenges. In some cases, it found itself limited by what was available in the published literature. At other times, it was challenged by the use of different methodologies for the classification of ovarian cancers in the research literature. For instance, many studies in the literature consolidate all types of ovarian cancer instead of studying and reporting them by subtype. In its review of the evidence, the committee discerns, where possible, whether the reported findings apply to ovarian cancers as a whole or to particular subtypes. One other major challenge to reviewing and summarizing the evidence base on ovarian cancer, particularly in summarizing the epidemiology by subtype, was the way that the grading, classification, and nomenclature for ovarian cancers have varied over the years.

In order to guide its deliberative process, the committee chose to make recommendations about research gaps based on the continuum of cancer care (see Figure 1-1 ). The committee focused on cross-cutting research areas critical to each phase of the continuum: the basic biology of ovarian cancers, innovative clinical trial design, intervention development, methods to reduce practice-related disparities, and supportive care research and practice. Finally, the committee considered evidence and strategies for the dissemination and implementation of knowledge across all of these domains.

DEFINITIONS OF KEY TERMS

This section provides definitions of several key terms that are relevant to this report, and also provides an explanation of how the committee

FIGURE 1-1 Framework for research in ovarian cancer. NOTE: Colored figures represent phases of the ovarian cancer care continuum where research can be focused. Black boxes indicate critical areas of ongoing cross-cutting research that span these phases.

selected terms for consistency throughout the report. A glossary including more terms is provided in Appendix B , and a list of key acronyms is included in Appendix A .

Target Population

This report is concerned with women with ovarian cancers. However, the committee recognizes that there is a small subpopulation of transgender men who may be at risk for ovarian cancers, particularly due to the use of testosterone therapy (Dizon et al., 2006; Hage et al., 2000).

Basic Cancer Terminology

The terms “cancer,” “carcinoma,” and “tumor” can be confused or interchanged at times. Cancer is “a term for diseases in which abnormal cells divide without control and can invade nearby tissues,” while a tumor (which can be cancerous or noncancerous) is “an abnormal mass of tissue that results when cells divide more than they should or do not die when they should” (NCI, 2015d). Carcinomas are cancers that “begin in the skin or in tissues that line or cover internal organs” (i.e., arising from epithelial cells) (NCI, 2015d). As was noted previously, this report focuses on ovarian carcinomas, because they are the most common and most lethal of the ovarian cancer subtypes.

While the committee endeavored to focus on carcinomas wherever possible, there were times when that was not possible, and the terms “cancer” and “tumor” are used when appropriate. For example, many studies are based on ovarian cancers collectively and do not analyze data based on the subtypes. The committee also uses the term “tumor” when discussing the physical mass itself. Finally, although the term “ovarian cancer” technically represents an array of disease subtypes, the committee refers to the disease in the plural form (i.e., “ovarian cancers”) whenever appropriate in order to emphasize the heterogeneity of the disease and all its subtypes.

When ovarian cancer reappears in a woman, it is usually referred to as “relapsed” or “recurrent” disease. The National Cancer Institute (NCI) defines cancer recurrence as “cancer that has recurred (come back), usually after a period of time during which the cancer could not be detected. The cancer may come back to the same place as the original (primary) tumor or to another place in the body” (NCI, 2015d). Noting that a cancer that has recurred is also called “relapsed cancer,” the NCI defines relapse as “the return of a disease or the signs and symptoms of a disease after a period of improvement.” In this report, for consistency the committee uses only the terms “recurrent” or “recurrence”—and not “relapsed” or “relapse”—but

it recognizes that there may be subtle differences, preferences, or interpretations in the use of the two terms.

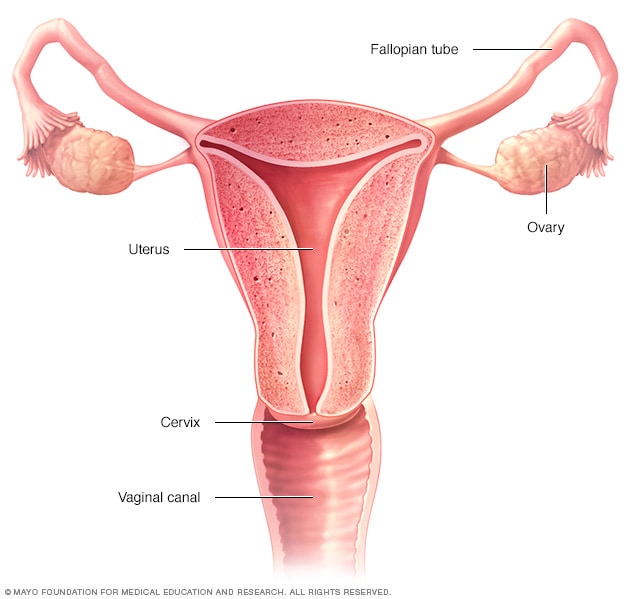

DEFINING AND CLASSIFYING OVARIAN CANCERS

“Ovarian cancer” is a generic term that can be used for any cancer involving the ovaries. The ovaries are composed of several different cell types, including the germ cells, specialized gonadal stromal cells (e.g., granulosa cells, theca cells, Leydig cells, and fibroblasts), and epithelial cells; ovarian cancers can arise from any of these cell types. Ovarian cancers with epithelial differentiation (carcinomas) account for more than 85 percent of ovarian cancers and are responsible for most ovarian cancer–related deaths (Berek and Bast, 2003; Braicu et al., 2011; SEER Program, 2015; Seidman et al., 2004). Consequently, this report will focus on the biology of ovarian carcinomas, while recognizing that although other, less common types of ovarian malignancies do exist, they are responsible for a smaller fraction of ovarian cancer–related deaths.

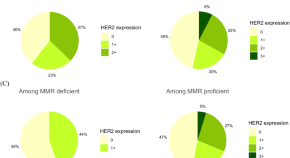

As with ovarian cancers in general, ovarian carcinomas are quite heterogeneous and come in a variety of different tumor types (see Figure 1-2 ). The major ovarian carcinoma subtypes are named according to how closely the tumor cells resemble normal cells lining different organs in the female genitourinary tract. Specifically, serous, endometrioid, and a subset

FIGURE 1-2 Percentage of cases by major ovarian carcinoma subtype. NOTE: Other* refers to mixed or transitional carcinomas where it is not possible to categorize to a single subtype. SOURCE: Gilks et al., 2008; Seidman et al., 2003, 2004.

of mucinous carcinomas exhibit morphological features that are similar to normal epithelial cells in the fallopian tube, endometrium, and endocervix, respectively. Furthermore, clear cell carcinomas resemble cells seen in the gestational endometrium (Scully et al., 1999).

Over the past several years, researchers have developed a streamlined classification scheme in which the majority of ovarian carcinomas can be divided into five types:

- Endometrioid carcinoma (EC),

- Clear cell carcinoma (CCC),

- Low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC), and

- Mucinous carcinoma (MC) (Gurung et al., 2013; Kalloger et al., 2011).

Some researchers have offered an even simpler classification with a scheme in which ovarian carcinomas are divided into Type I and Type II tumors based on shared features (Shih and Kurman, 2004). In this scheme, Type I carcinomas are low-grade, relatively unaggressive, and genetically stable tumors that often arise from recognizable precursor lesions such as endometriosis or benign tumors and frequently harbor somatic mutations that deregulate specific cell signaling pathways or chromatin remodeling complexes. ECs, CCCs, MCs, and LGSCs are considered Type I tumors and are often characterized by KRAS, BRAF , or PTEN mutations. Type II carcinomas are high-grade, biologically aggressive tumors from their inception, with a propensity for metastasis from small, even microscopic, primary lesions. HGSCs represent the majority of Type II tumors and are characterized by the mutation of TP53 and frequent mutations of genes (e.g., BRCA1 and BRCA2 ) that lead to homologous recombination defects (Pennington et al., 2014).

Because the data collected thus far provide compelling evidence that each of the various Type I tumors has distinct biological and molecular features, these tumors will be referred to by their specific histologic type throughout the remainder of this report. However, the Type I and Type II terminology will be used where necessary, most often in referring to studies conducted using this classification scheme. Furthermore, because the majority of ovarian carcinomas are HGSCs, and HGSCs are the subtype with the worst prognosis, this report will primarily focus on this subtype. When referring to historical or large-scale epidemiologic studies of ovarian cancer for which the tumor subtypes were not specified, readers can reasonably assume that most of the tumors were HGSCs.

After being classified by subtype, tumors are usually also assigned a grade, based on how closely the tumor cells resemble their normal counter-

parts. Both two-grade and three-grade systems have been applied in various situations; in both types of systems, the lower-grade tumors more closely resemble normal cells than the higher-grade tumors (Malpica et al., 2004; Silverberg, 2000).

OVARIAN CANCER PATTERNS AND DEMOGRAPHICS 4

Although ovarian cancer is relatively rare, it is one of the deadliest cancers. It was estimated that more than 21,000 women in the United States would receive a diagnosis of an ovarian cancer in the year 2015 5 (Howlader et al., 2015). This represents almost 12 new cases for every 100,000 women and 2.6 percent of all new cancer cases in women in the United States. Nearly 200,000 women in the United States are living with ovarian cancer in any given year, and approximately 1.3 percent of all American women will be diagnosed with ovarian cancer at some point in their lives, which qualifies ovarian cancer as a rare disease as defined by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Genetic and Rare Diseases Information Center (NIH, 2015a). Still, according to estimates, more than 14,000 American women will have died from ovarian cancer in 2015, which corresponds to approximately 7.7 deaths per 100,000 women and 5.1 percent of all cancer deaths among American women (ACS, 2015; Howlader et al., 2015). Despite its relatively low incidence, ovarian cancer is the fifth leading cause of cancer deaths among U.S. women and the eighth leading cause of women’s cancer deaths worldwide (Ferlay et al., 2015; Howlader et al., 2015). By comparison, breast cancer is more common—among American women the estimated number of new cases of breast cancer each year is 10 times the number of new cases of ovarian cancer—but ovarian cancer is more deadly, with a death-to-incidence ratio that is more than three times higher than for breast cancer (Howlader et al., 2015) (see Figure 1-3 ).

The survival rate for ovarian cancer is quite low. For 2005 to 2011, the 5-year survival rate in the United States was just 45.6 percent. By contrast, the 5-year survival rate in the United States for the same period was nearly 90 percent for breast cancer, more than 80 percent for endometrial cancer, and nearly 70 percent for cervical cancer. However, given the typical course of initial remission and subsequent recurrence for women with ovarian cancer, the 5-year survival metric may not reflect the overall disease course. At advanced stages, MCs and CCCs in particular have poorer prognoses and survival rates than other carcinoma subtypes (Mackay et al., 2010).

4 Terminology to describe race and ethnicity reflects the terminology used in the original sources.

5 Because historical epidemiologic data typically combine the multiple types of ovarian cancer, they are discussed as a single disease in this discussion of epidemiology.

FIGURE 1-3 The ratio between the death and incidence rates for ovarian, breast, endometrial, and cervical cancers per 100,000 women in the United States, 2008–2012. SOURCE: Howlader et al., 2015.

The incidence of ovarian cancer has declined slightly since the mid-1970s, when the incidence was approximately 16 new cases per 100,000 women (Howlader et al., 2015). Mortality from ovarian cancer has also declined—from 9.8 deaths per 100,000 women in 1975 to 7.4 deaths per 100,000 women in 2012. However, the decline in mortality is relatively small when compared to reductions in death rates achieved for most other female gynecological cancers and for breast cancer in women. For example, the death rate from breast cancer fell by one-third between 1975 and 2012, from 31.4 deaths per 100,000 women to 21.3 deaths per 100,000, and the death rate from cervical cancer dropped by more than half during that same period, from 5.6 deaths per 100,000 women to 2.3 deaths per 100,000.

Among women who were diagnosed with ovarian cancer between 1975 and 1977, only 36 percent lived 5 years or more, while nearly half (46 percent) of women diagnosed with ovarian cancer between 2005 and 2007 lived at least 5 years beyond their diagnosis (Howlader et al., 2015). However, that improvement in survival rates was driven primarily by improvements in survival among white women; survival rates decreased (from 42 to 36 percent) over the same period for black women (ACS, 2015; also see section Race and Ethnicity later in this chapter).

Stage Distribution

Ovarian cancer’s high mortality and low survival rates can be attributed in part to the fact that it is rarely diagnosed at an early stage. Indeed, 60 percent of women are diagnosed with advanced disease, when the cancer has already spread beyond the ovary to distant organs or lymph nodes (Howlader et al., 2015). In comparison, as seen in Figure 1-4 , other female cancers are more commonly diagnosed during the localized or regional stages.

The relatively late stage of diagnosis for ovarian cancer is particularly important because survival is highly correlated with the stage at diagnosis (see Figure 1-5 ). While the 5-year survival rate is 45.6 percent overall, it is substantially higher for women diagnosed while the cancer is still at the localized stage (92.1 percent) or the regional stage (73.2 percent), and it is substantially lower for women diagnosed at the distant stage (28.3 percent) (ACS, 2015; Howlader et al., 2015). Survival is lowest among women who receive an unstaged ovarian cancer diagnosis (22.9 percent).

White and black women show similar patterns of stage distribution (see Figure 1-6 ). However, there is a difference in stage of diagnosis in women

FIGURE 1-4 Distribution (percentage) of stage of diagnosis for cancers of the breast, endometrium, cervix, and ovary among U.S. women, 2005–2011. SOURCE: Howlader et al., 2015.

FIGURE 1-5 Five-year relative survival (percentage) from ovarian cancer by stage at diagnosis among U.S. women, 2005–2011. SOURCE: Howlader et al., 2015.

FIGURE 1-6 Stage distribution (percentage of cases) at diagnosis among white and black U.S. women diagnosed with ovarian cancer, 2003–2009. SOURCE: Howlader et al., 2015.

of different ages, with women younger than age 65 tending to be diagnosed at earlier stages than women older than age 65 (see Figure 1-7 ).

Ovarian cancer incidence increases with age, with a sharp increase in the rate beginning in the mid-40s (see Figure 1-8 ). From 2008 to 2012, nearly 88 percent of all new cases of ovarian cancer occurred among women ages 45 and older, with 69 percent of cases among women ages 55 and older, and the average age at diagnosis was 63 years. A half-century ago, most cases occurred among women between the ages of 35 and 63, and the average age at diagnosis was 48.5 years (Munnell, 1952).While the age-adjusted incidence rate for ovarian cancer among all women is nearly 12 cases per 100,000 women, the rate varies sharply with age, with women younger than age 65 having an incidence rate of 7.5 cases per 100,000 women while women 65 years old and older have an incidence rate of more than 42 cases per 100,000 women (Howlader et al., 2015).

Mortality rates also increase sharply with age. The death rate for women aged 65 and older is approximately 13 times that of women less than age 65 (see Figure 1-9 ). Furthermore, while mortality rates have de-

FIGURE 1-7 Stage distribution (percentage of cases) at diagnosis among women diagnosed with ovarian cancer by age, 2003–2009. SOURCE: Howlader et al., 2015.

FIGURE 1-8 Age-adjusted incidence of ovarian cancer per 100,000 women in the United States by age group. SOURCE: SEER Program, 2015.

FIGURE 1-9 Trends in age-adjusted death rates from ovarian cancer per 100,000 women in the United States by age group, 1975–2012. SOURCE: Howlader et al., 2015.

clined overall in the past 40 years, most of this decline is attributable to decreases in mortality among women diagnosed with ovarian cancer less than age 65 (ACS, 2015; Howlader et al., 2015).

Race and Ethnicity

The patterns of ovarian cancer incidence and mortality differ substantially among women of different races and ethnic backgrounds (see Figure 1-10 ). Whites have the highest incidence of ovarian cancer, followed by Hispanics, American Indian/Alaska Natives, blacks, and Asian/Pacific Islanders (ACS, 2015; Howlader et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2014). The 5-year survival rate is highest among Asian/Pacific Islanders, followed by Hispanics, whites, American Indian/Alaska Natives, and blacks, while mortality rates are highest among whites, followed by blacks, Hispanics, American Indian/Alaska Natives, and Asian/Pacific Islanders. A particularly dramatic contrast can be seen between black and Asian/Pacific Islander women. While the two groups are similar in having low incidence rates, black women have the second-highest mortality rates and the lowest survival rates, while Asian/Pacific Islanders have the lowest mortality and the highest survival rates. The incidence of ovarian cancer, particularly HGSC, is higher than average in women of Ashkenazi Jewish ancestry, in part because of the higher prevalence of deleterious mutations in cancer-predisposition genes such as BRCA1 and BRCA2 among these women (ACS, 2015; Moslehi et al., 2000).

FIGURE 1-10 Age-adjusted ovarian cancer incidence and mortality per 100,000 U.S. women by race and ethnicity, 2008–2012. SOURCE: Howlader et al., 2015.

Furthermore, the variations in the incidence rates of ovarian cancer by race and ethnicity change as women age (see Figure 1-11 ). For example, whites and Asian/Pacific Islanders have similar incidence rates until around age 50, when their incidence rates begin to diverge. White women aged 45–49 have an age-specific incidence rate of 15.1 cases per 100,000, and Asian/Pacific Islanders of the same age group have a very similar rate of 15.5 cases per 100,000. By contrast, white women aged 80–84 have an incidence rate of 50.8 cases per 100,000, while Asian/Pacific Islanders of the same age group have a dramatically lower rate of 30.1 cases per 100,000.

Historical trends also show considerable variations by race. Between 2003 and 2012, mortality rates decreased significantly among whites and Hispanics, while declines in mortality among blacks, Asian/Pacific Island-

FIGURE 1-11 Age-specific incidence rates of ovarian cancer per 100,000 women in the United States by race/ethnicity and age at diagnosis, 2008–2012. NOTE: Rates for American Indian/Alaska Natives are only displayed for ages 50 through age 69, because the number of cases in other age groups were less than 16 per age group. SOURCE: SEER Program, 2015.

ers, and American Indian/Alaskan Natives were not statistically significant (Howlader et al., 2015). Moreover, while survival rates have increased among women overall and among white women since the mid-1970s, survival rates have declined slightly among black women (see Figure 1-12 ). Furthermore, although black women had higher rates of survival compared to white women and to women overall in 1975, by the mid-1980s survival rates had begun to reverse, such that black women now have lower survival rates than white women and women of all races overall even despite gains in survival among blacks in the 1990s (ACS, 2015).

In the United States, there are slight geographic variations in ovarian cancer incidence, but these variations are not significant (Howlader et al., 2015; Ries et al., 2007). However, the differences in mortality from state to state are significant. In the United States, from 2008 to 2012 the death rate for ovarian cancer was 7.7 deaths per 100,000 women. During that same period, the age-adjusted death rates by state ranged from a low of 5.3 deaths per 100,000 women in Hawaii to a high of 9.0 deaths per 100,000 women in Oregon (Howlader et al., 2015). Despite the wide variation

FIGURE 1-12 Trends in 5-year relative survival rates (percentage) for ovarian cancer among U.S. women by race, 1975–2011. SOURCE: Howlader et al., 2015.

across the states, only Alabama, Oregon, Pennsylvania, and Washington have significantly higher rates, statistically speaking, than the United States as a whole, while only Florida, Hawaii, and Texas have significantly lower rates than the national average.

Ovarian cancer incidence and mortality also vary internationally, with incidence and mortality rates being higher in more developed regions than in less developed regions (Ferlay et al., 2015).

Aside from genetics (e.g., the higher proportion of mutations in cancer-predisposition genes among Ashkenazi Jewish women), the reasons behind the racial and ethnic differences in outcomes are unknown, but they might be explained in part by other variables such as differences in access to health care or the quality of that care (Baicker et al., 2005; IOM, 2003, 2012). Similarly, the reasons behind geographic variation in the demographics of ovarian cancer are unknown, and might be explained by other variables such as race and ethnicity (e.g., the higher proportion of Asian and Pacific Islanders in Hawaii) or differences in access to health care or the quality of that care in different geographic regions (Baicker et al., 2005; IOM, 2003, 2012). (See Chapter 4 for more on access and standards of care for women with ovarian cancer.) Overall, as noted previously, reporting on the demographics and epidemiology of ovarian cancer is challenging because of the fact that most of the data sources aggregate the various subtypes, and even when the data are reported by subtype, differences in the grading, classification, and nomenclature of the subtypes create challenges in summarizing and comparing data.

THE LANDSCAPE OF STAKEHOLDERS IN OVARIAN CANCER RESEARCH

Many public and private organizations are involved in funding, supporting, and carrying out ovarian cancer research, and they are involved in a variety of ways. The research is sometimes focused on ovarian cancers exclusively, but it sometimes looks at broader populations (e.g., women with gynecologic cancers). A complete cataloguing of every stakeholder in ovarian cancer research and of their individual efforts is beyond the scope of this report. Instead, this section offers an overview of the wide range of stakeholders and highlights the areas of ovarian cancer research that are getting the most attention and the methods used by stakeholders to communicate about new findings in ovarian cancer research.

Federal Stakeholders

While there are a number of different federal stakeholders in ovarian cancer research, the CDC, the U.S. Department of Defense (DoD), and the NIH (and the NCI in particular) are collectively responsible for the majority of the funding for ovarian cancer research at the federal level. The sections below give an overview of the funding levels and focus areas for these agencies. Where possible, the areas of focus are presented in alignment with the Common Scientific Outline (CSO), an international classification system used by cancer researchers to compare research portfolios. The CSO consists of seven broad areas of interest:

- Etiology (causes of cancer);

- Prevention;

- Early detection, diagnosis, and prognosis;

- Cancer control, survivorship, and outcomes research; and

- Scientific model systems (DoD, 2015b).

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The CDC conducts and supports studies, often in collaboration with partners, to “develop, implement, evaluate, and promote effective cancer prevention and control practices” (CDC, 2015). In general, the CDC approaches cancer by monitoring cancer demographics (surveillance), by conducting research and evaluation, by partnering with other stakeholders to help translate evidence, and by developing educational materials (CDC, 2015). Most of the CDC’s work in ovarian cancer is performed through its Division of Cancer Prevention and Control. 6 Since fiscal year (FY) 2000, the CDC has received about $5 million annually in congressional appropriations to support its Ovarian Cancer Control Initiative. In addition, in 2008 the CDC started receiving funds under Johanna’s Law to improve communication with women regarding gynecologic cancers. The CDC’s Inside Knowledge 7 campaign works to raise awareness about cervical, ovarian, uterine, vaginal, and vulvar cancers. Between 2010 and 2014, ads produced for the Inside Knowledge campaign were seen or heard around 3.5 million times and were worth a total of $136 million in donated ad value (CDC, 2014).

6 For more information, see http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/dcpc/about (accessed July 21, 2015).

7 For more information, see http://www.cdc.gov/cancer/knowledge (accessed September 1, 2015).

U.S. Department of Defense

The DoD’s Ovarian Cancer Research Program (OCRP) 8 received congressional appropriations from FY 1997 to FY 2014 totaling $236.45 million and received another $20 million in appropriations for FY 2015 (DoD, 2015a). Since the inception of the DoD OCRP, more than 130 ovarian cancer survivors have taken part in efforts to establish the OCRP’s priorities and research award mechanisms, and they have helped choose the research to be funded. From FY 1997 through FY 2013, the OCRP funded 313 awards in a variety of areas (see Figure 1-13 ). These awards show a focus on biology, treatment, and early detection, diagnosis, and prognosis. OCRP’s research priorities include understanding the precursor lesions, microenvironment, and pathogenesis of all types of ovarian cancer; developing and improving the performance and reliability of screening, diagnostic approaches, and treatment; developing or validating models to study initiation and progression; investigating tumor response to therapy; and enhancing the pool of ovarian cancer scientists (DoD, 2015a).

National Institutes of Health

The NCI of the NIH has initiated several activities to advance ovarian cancer research with intramural and extramural funding. In the past, five ovarian cancer–specific specialized programs of research excellence (SPOREs) in the United States conducted ovarian cancer research in early detection, imaging technologies, risk assessment, immunosuppression, and novel therapeutic approaches (NCI, 2015e). The NCI currently lists four active SPOREs for ovarian cancer.

The NCI is involved in ovarian cancer research in a variety of other ways. For example, the Clinical Proteomic Tumor Analysis Consortium (CPTAC) is trying to understand the molecular basis of cancer in order to help improve the diagnosis, treatment, and prevention of cancer (NCI, 2015b). To accomplish these goals, CPTAC is using the data collected by The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) analysis of ovarian tumors. The NCI has also supported a follow-up of the Prostate, Lung, Colorectal, and Ovarian (PLCO) Cancer Screening Trial to analyze the biological material and risk factor information in order to better understand the risks and identify early biomarkers, including biomarkers for ovarian cancers. (See Chapter 3 for more on the PLCO Cancer Screening Trial.)

8 For more information, see http://cdmrp.army.mil/ocrp (accessed July 21, 2015).

FIGURE 1-13 Areas of ovarian cancer research funded by OCRP, FY 1997–2011. SOURCE: DoD, 2015b.

Overall, the NCI supported $100.6 million in research 9 related to ovarian cancer in FY 2013 while providing $559.2 million for breast cancer research, $63.4 million for cervical cancer research, and $17.8 million for endometrial cancer research (NCI, 2015g). However, the research projects listed as being related to ovarian cancer are not necessarily limited to ovarian cancer, and they include studies of multiple cancers (including ovarian cancer) or areas of cross-cutting research related to ovarian cancer. Fur-

9 The NCI notes that “the estimated NCI investment is based on funding associated with a broad range of peer-reviewed scientific activities” (NCI, 2015g). The NCI research portfolio for ovarian cancer may be found at http://fundedresearch.cancer.gov/nciportfolio/search/get?site=Ovarian+Cancer&fy=PUB2013 (accessed December 2, 2015).

thermore, data collected by the DoD 10 through the International Cancer Research Partnership indicates that the funded amount is significantly less when considering only new grants awarded by the NCI each year. Only 52 projects involving ovarian cancer research totaling $33.4 million were started in 2010, 58 new projects totaling $20.4 million in 2011, and 52 new projects totaling $16.3 million in 2012 (ICRP, 2015). Figure 1-14 shows that, like the DoD, the NCI portfolio for ovarian cancer research focuses primarily on treatment, biology, and early detection, diagnosis, and prognosis.

The Office of Cancer Survivorship (OCS), 11 part of the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences at the NCI, “works to enhance the quality and length of survival of all persons diagnosed with cancer and to minimize or stabilize adverse effects experienced during cancer survivorship. The office supports research that both examines and addresses the long- and short-term physical, psychological, social, and economic effects of cancer and its treatment among pediatric and adult survivors of cancer and their families” (NCI, 2014).

Figure 1-15 shows the areas of cancer survivorship research expertise at the NCI. As of October 2015, the Division of Cancer Control and Population Sciences had two open funding opportunities for general cancer survivorship research: one focused on the efficacy and impact of care planning, and the other examined the effects of physical activity and weight control interventions on cancer prognosis and survival (NCI, 2015a). Neither of these grant opportunities specified a focus on ovarian cancer survivorship.

Private Stakeholders

A wide variety of private stakeholders are engaged in ovarian cancer research, including professional societies, advocacy organizations, women’s health groups, and disease-specific foundations. In some cases, the organization specifically focuses on ovarian cancer and ovarian cancer research. However, many others focus on cancer or women’s health broadly (e.g., the American Cancer Society and the American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists). Overall, private funders of ovarian cancer research tend to focus funding on biology and treatment, with very little funding directed toward the etiology of ovarian cancer or survivorship issues.

Private stakeholders can support young researchers with grant funding; provide training and educational opportunities; encourage collabora-

10 Personal communication, Patricia Modrow, data assembled by the U.S. Department of Defense Ovarian Cancer Research Program, January 16, 2015.

11 For more information about the OCS, see http://cancercontrol.cancer.gov/ocs (accessed May 15, 2015).

FIGURE 1-14 Areas of ovarian cancer research funded by the NCI. SOURCE: NCI, 2013.

tive, transdisciplinary efforts; and engage consumers, survivors, and their families. Examples of previous and current efforts by individual private stakeholders include

- The Health, Empowerment, Research, and Awareness Women’s Cancer Foundation awarded the Sean Patrick Multidisciplinary Collaborative Grant for cross-disciplinary projects to allow scientists to come together and test ideas that may not be fundable by other agencies (HERA, 2015).

- The Marsha Rivkin Center for Ovarian Cancer Research awards Bridge Funding Awards to researchers who are close to fundable grant scores for the DoD or the NIH but require additional data to ensure a successful resubmission (Rivkin Center, 2015).

- The Ovarian Cancer Research Fund (OCRF) provides funding to researchers at all stages of their careers; OCRF awards include funding for recent graduates, newly independent researchers who are building laboratories, and senior researchers working on collaborative projects (OCRF, 2015).

FIGURE 1-15 Expertise areas for cancer survivorship research at the NCI. SOURCE: NCI, 2015c.

- The Society of Gynecologic Oncology (SGO) released Pathways to Progress in Women’s Cancer in 2011, a research agenda based on discussions of working groups at a 2010 research summit. One working group focused on ovarian cancers, and the report provides short-term, intermediate, and long-term research priorities (SGO, 2011).

- The Honorable Tina Brozman Foundation for Ovarian Cancer Research (also known as Tina’s Wish) funds research specifically in the early detection and prevention of ovarian cancer and also supports a consortium to advance such research (Tina’s Wish, 2015).

The Role of Advocacy in Ovarian Cancer Research

Advocacy has positively affected ovarian cancer research, public knowledge, and awareness. Many different types of people play the role of

advocate—women with ovarian cancer, partners, family members, health care professionals, and activists—and their advocacy efforts range from the individual, patient level to the societal level, but all of these different efforts have had effects on funding efforts, policy change, and the direction of research.

Patients self-advocate by taking active roles in their own care. Researchers have recognized this concept of self-advocacy as an important part of patient-centered care, and it has been described as “a distinct type of advocacy in which an individual or group supports and defends their interests either in the face of a threat or proactively to meet their needs” (Hagan and Donovan, 2013, p. 3). However, despite claims that self-advocacy may improve quality of life, health care use, and symptom management, these potential effects have not been adequately studied.

Nurses can serve as advocates for patients by protecting patients’ rights, incorporating patients’ beliefs and values into their care plans, and respecting the autonomy of the patient to ensure access to quality care (Temple, 2002). Advocacy groups provide education, information, and personal support to patients, family caregivers, and the general public. Many advocacy groups also use lobbying efforts to influence policy, including the direction of research and funding.

Large-scale advocacy efforts have arguably had a great impact on cancer research and funding. In the late 1990s, survivors advocated for wider recognition of early-stage ovarian cancer symptoms. Until that time, physicians and medical textbooks had claimed that women did not experience symptoms until advanced stages of disease (Twombly, 2007). Johanna’s Law is considered a victory of advocacy groups’ lobbying efforts. Furthermore, Congress has appropriated funds for ovarian cancer research and education programs since FY 1997. The establishment and unified efforts of national advocacy organizations are partially responsible for the significant funding increases in the intervening years (Temple, 2002).

Advocacy groups have also been integral to the advancement of ovarian cancer research through their participation in the design and administration of studies (Armstrong et al., 2014; Holman et al., 2014). The scientific literature emphasizes the importance of patient advocates in patient-centered research, citing examples of the collaboration between researchers and patient advocates in research studies (Armstrong et al., 2014; Holman et al., 2014; Staton et al., 2008).

Several large advocacy groups at the national and international levels focus on ovarian cancer. For example, the Ovarian Cancer National Alliance (OCNA), a national advocacy organization, has among its activities the Survivors Teaching Students: Saving Women’s Lives® program, which is aimed at educating caregivers and medical, nursing, and other professional

students about the early signs and symptoms of ovarian cancer. Recently, OCNA spearheaded the formation of the first congressional Ovarian Cancer Caucus with the support of Rosa DeLauro (D-CT) and Sean Duffy (R-WI). The first meeting was held on September 29, 2015, in Washington, DC. The National Ovarian Cancer Coalition (NOCC), another national advocacy organization, funds the Teal Initiative to improve education and awareness. NOCC also supports specific research in ovarian cancer and provides survivor support, primarily through its Faces of Hope program, which is “dedicated to improving the quality of life for women affected by ovarian cancer, as well as providing support for their loved ones and caregivers” (NOCC, 2014). At the international level, the charity Ovarian Cancer Action encourages collaboration among ovarian cancer researchers around the world. Half of its funds go to the Ovarian Cancer Action Research Centre in the United Kingdom, which exclusively supports “research that can be translated into meaningful outcomes for real women in real life” (Ovarian Cancer Action, 2015). In addition, every few years Ovarian Cancer Action hosts an international forum to bring researchers together to share information, inspire collaboration, and develop white papers. In 2011 the forum developed the paper Rethinking Ovarian Cancer: Recommendations for Improving Outcomes, which outlined recommendations for improving outcomes for women with ovarian cancer (Vaughan et al., 2011). A number of other advocacy groups work at the local and national levels to support research in ovarian cancer.

The Role of Consortia and Collaboration in Ovarian Cancer Research

Because of the relative rarity of ovarian cancers, especially when subdivided according to subtypes, collaborative research efforts are necessary in order to collect sufficient data for statistically significant results. Many consortia and multisite studies have evolved to promote the sharing of biospecimens, clinical data, and epidemiologic data in order to ensure sufficient sample sizes in studies. These consortia and collaborations operate at both the national and international levels. Common uses of consortia include carrying out research on the genetic and nongenetic risk factors of developing ovarian cancers, studying mechanisms of disease relapse and resistance, and identifying newer therapies (AOCS, 2015; COGS, 2009; NRG Oncology, 2015; OCAC, 2015; OCTIPS, 2015). Furthermore, groups will often team together in coalitions to promote transdisciplinary research and also to promote the translation and dissemination of information. For example, in 2015, OCNA, NOCC, and OCRF provided funding for the Stand Up To Cancer (SU2C) Dream Team for ovarian cancer. This team will bring together experts in DNA repair, translational investigators, and

clinicians “to create new programs in discovery, translation, and clinical application, while cross-fertilizing and educating researchers at all levels to enhance collaboration and catalyze translational science” (SU2C, 2015).

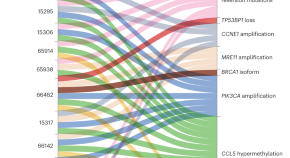

Consortia and coalitions have had clear, measureable impacts on the research base for ovarian cancers. For example, as a result of the Collaborative Oncological Gene-environment Study (COGS), 14 new markers for risk of ovarian cancer were identified (only 8 had been known before COGS) (COGS, 2014). Based on the work of this coalition, TCGA researchers completed a detailed analysis of ovarian cancer, which confirmed that mutations in the TP53 gene (which encodes a protein that normally suppresses tumor development) are present in nearly all HGSCs (Bell et al., 2011). The analysis also examined gene expression patterns and identified signatures that correlate with survival outcomes, affirmed four subtypes of HGSCs, and identified dozens of genes that might be targeted by gene therapy (NIH, 2011, 2015b).

NCI’s National Clinical Trials Network

In 1955 the NCI established the Clinical Trials Cooperative Group Program. As the science of cancer treatment was evolving, researchers realized that collaborative efforts were necessary to accrue sufficient numbers for clinical trials in order to more rapidly compare the value of new therapies to existing standards of care, particularly for the use of chemotherapy in the treatment of solid tumors (DiSaia et al., 2006; IOM, 2010b). The work of the cooperative groups led to advances in the treatment of women with ovarian cancer specifically, including a demonstration of the value of adding paclitaxel to cisplatin, confirmation of the value of cytoreductive surgery, and a demonstration of the value of carboplatin for late-stage ovarian cancers (IOM, 2010b). The groups have also studied issues related to the quality of life and the prevention of ovarian cancer. Between 1970 and 2005, clinical trials of the Gynecologic Oncology Group (GOG) alone included approximately 35,000 women with ovarian cancer (DiSaia et al., 2006).

In 2014, based in part on the IOM report A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century , the NCI transformed the cooperative group program into the new National Clinical Trials Network (IOM, 2010b, 2011, 2013b; NCI, 2015f). This reorganization consolidated nine cooperative groups into five new groups:

- The Alliance for Clinical Trials in Oncology;

- The ECOG-ACRIN Cancer Research Group (a merger of two cooperative groups: the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group and the American College of Radiology Imaging Network);

- NRG Oncology (a merger of three cooperative groups: the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project, the Radiation Therapy Oncology Group, and the GOG);

- The Southwest Oncology Group; and

- The Children’s Oncology Group (NCI, 2015f).

PREVIOUS WORK AT THE INSTITUTE OF MEDICINE

The IOM has a long history of producing reports related to various aspects of cancer care, and many of them are directly relevant to this current study. This section describes some examples of previous IOM work that is related to the work of this committee.

Prevention and Early Detection

In 2005 the IOM report Saving Women’s Lives: Strategies for Improving Breast Cancer Detection and Diagnosis (IOM, 2005) recommended the development of tools to identify the women who would benefit most from breast cancer screening based on “individually tailored risk prediction techniques that integrate biologic and other risk factors.” The report also called for the development of tools that “facilitate communication regarding breast cancer risk to the public and to health care providers.” In addition, the report called for more research on breast cancer screening and detection technologies, including research on various aspects of technology adoption (e.g., monitoring the use of technology in clinical practice).

A 2007 IOM report, Cancer Biomarkers , offered recommendations on the methods, tools, and resources needed to discover and develop biomarkers for cancer; guidelines, standards, oversight, and incentives needed for biomarker development; and the methods and processes needed for clinical evaluation and adoption of such biomarkers (IOM, 2007a). Specific recommendations from the report included establishing international consortia to generate and share data, supporting high-quality biorepositories of prospectively collected samples, and developing criteria for conditional coverage of new biomarker tests. Subsequently, in 2010, an IOM report, Evaluation of Biomarkers and Surrogate Endpoints in Chronic Disease , outlined a framework for the evaluation of biomarkers (IOM, 2010a).

In Initial National Priorities for Comparative Effectiveness Research (IOM, 2009), the committee offered two priorities that are relevant to ovarian cancer genetics: “Compare the effectiveness of adding informa-

tion about new biomarkers (including genetic information) with standard care in motivating behavior change and improving clinical outcomes” and “Compare the effectiveness of genetic and biomarker testing and usual care in preventing and treating breast, colorectal, prostate, lung, and ovarian cancer, and possibly other clinical conditions for which promising biomarkers exist” (IOM, 2009, p. 4).

In 2007, the IOM’s National Cancer Policy Forum hosted a workshop on cancer-related genetic testing and counseling. According to the published summary of that workshop, participants observed that “genetic testing and counseling are becoming more complex and important for informing patients and families of risks and benefits of certain courses of action, and yet organized expert programs are in short supply. The subject matter involves not only the scientific and clinical aspects but also workforce and reimbursement issues, among others” (IOM, 2007b)

Clinical Trials

The 2005 IOM report on breast cancer detection called for public health campaigns and for improved information and communication about the value of participation in clinical trials (including the participation of healthy individuals).

A 2010 report, A National Cancer Clinical Trials System for the 21st Century: Reinvigorating the NCI Cooperative Group Program (IOM, 2010b), called for the restructuring of the NCI Cooperative Group Program and set four goals:

- Improve the speed and efficiency of the design, launch, and conduct of clinical trials (e.g., improve collaboration among stakeholders);

- Incorporate innovative science and trial design into cancer clinical trials (e.g., support standardized central biorepositories, develop and evaluate novel trial designs);

- Improve the means of prioritization, selection, support, and completion of cancer clinical trials (e.g., develop national unified standards); and

- Incentivize the participation of patients and physicians in clinical trials (e.g., develop electronic tools to alert clinicians to available trials for specific patients, encourage eligibility criteria to allow broad participation, cover cost of patient care in trials).

Palliative and End-of-Life Care

Improving Palliative Care for Cancer (IOM, 2001) called for incorporating palliative care into clinical trials. The report also noted that infor-

mation on palliative and end-of-life care is largely absent from materials developed for the public about cancer treatment, and the committee recommended strategies for disseminating information and improving education about end-of-life care. The report recommended that the NCI require comprehensive cancer centers to carry out research in palliative care and symptom control and that the Health Care Finance Administration (now the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services) fund demonstration projects for service delivery and reimbursement that integrate palliative care throughout the course of the disease.

Dying in America (IOM, 2015) noted that palliative care can begin early in the course of treatment, in conjunction with treatment, and can continue throughout the continuum of care. The report further observed that “a palliative approach can offer patients near the end of life and their families the best chance of maintaining the highest possible quality of life for the longest possible time” (IOM, 2015, p. 1).

Delivering High-Quality Cancer Care: Charting a New Course for a System in Crisis (IOM, 2013a) addressed the delivery of cancer care, including palliative and end-of-life care. The study called for providing patients and their families with understandable information about palliative (and other) care and recommended that “the cancer care team should provide patients with end-of-life care consistent with their needs, values, and preferences” (IOM, 2013a, p. 9).

Communication and Survivorship

From Cancer Patient to Cancer Survivor (IOM, 2006) called for actions to raise awareness about the needs of cancer survivors, including the establishment of cancer survivorship as a distinct phase of cancer care. In 2008, the IOM report Cancer Care for the Whole Patient: Meeting Psychosocial Health Needs (IOM, 2008) recommended that facilitating effective communication between patients and care providers, identifying psychosocial health needs, and engaging and supporting patients in managing their illnesses should all be considered as part of the standard of care. The report emphasized the importance of educating patients and their families and of enabling patients to actively participate in their own care by providing tools and training in how to obtain information, make decisions, solve problems, and communicate more effectively with their health care providers. The report further called for the government to invest in a large-scale demonstration and evaluation of various approaches to the efficient provision of psychosocial health care.

Women’s Health Research (IOM, 2010c) found that there are many barriers to the translation of research findings in general and that some have aspects that are “peculiar to women.” The committee recommended

specific research on how to translate research findings on women’s health into clinical practice and public health policies.