- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

2.3: Case Selection (Or, How to Use Cases in Your Comparative Analysis)

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 150427

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the importance of case selection in case studies.

- Consider the implications of poor case selection.

Introduction

Case selection is an important part of any research design. Deciding how many cases, and which cases to include, clearly help determine the outcome of our results. Large-N research is when the number of observations or cases is large enough that we would need mathematical, usually statistical, techniques to discover and interpret any correlations or causations. In order for a large-N analysis to yield any relevant findings, a number of conventions need to be observed.

- First, the sample needs to be representative of the studied population. Thus, if we wanted to understand the long-term effects of COVID, we would need to know the approximate details of those who contracted the virus. Once the parameters of the population are known, we can then determine a sample that represents the larger population. For example, women make up 55% of all long-term COVID survivors. Thus, any sample we generate needs to be at least 55% women.

- Second, some kind of randomization technique needs to be involved. In other words, there must be randomly selected people within the sample. Randomization would help to reduce bias in the study. Also, when cases (people with long-term COVID) are randomly chosen they need to ensure a fairer representation of the studied population.

- The sample needs to be large enough, hence the large-N designation, for any conclusions to have any external validity. Generally speaking, the larger the number of observations/cases in the sample, the more validity in the study. There is no magic number. However, the sample of long-term COVID patients should be at least over 750 people, with an aim of around 1,200 to 1,500 people.

When it comes to comparative politics, we rarely ever reach the numbers typically used in large-N research. There are approximately 195 fully recognized countries, a dozen partially recognized countries, and even fewer areas or regions of study, such as Europe or Latin America. Given this, what is the strategy when one case, or a few cases, is being studied? What happens if we are only wanting to know the COVID-19 response in the United States, and not the rest of the world? How do we randomize to ensure the results are not biased? These questions are legitimate issues that many comparativist scholars face when completing research.

Does randomization work with case studies? Gerring suggests that it does not, as “any given sample may be widely representative” (pg. 87). Thus, random sampling is not a reliable approach when it comes to case studies. And even if the randomized sample is representative, there is no guarantee that the gathered evidence would be reliable.

In large-N research, potential errors and/or biases may be ameliorated (make better or more tolerable), especially if the sample is large enough. Incorrect or biased inferences are less of a worry when we have 1,500 cases versus 15 cases. In small -N research, case selection simply matters much more.

According to Blatter and Haverland (2012), “case studies are ‘case-centered’, whereas large-N studies are ‘variable-centered’". In large-N studies, the concern is with conceptualization and operationalization of variables. So which data should be included in the analysis of long-term COVID patients? A survey might be an option, with appropriately constructed questions. Why? For almost all survey-based large-N research, the question responses become the coded variables used in the statistical analysis.

Case selection can be driven by a number of factors in comparative politics.

- First, it can derive from the interests of the researcher(s). For example, if the researcher lives in Germany, they may want to research the spread of COVID-19 within the country, possibly using a subnational approach comparing infection rates among German states.

- Second, case selection may be driven by area studies. Researchers may pick areas of study due to their personal interests. For example, an European researcher may study COVID-19 infection rates among European Union member-states.

- Compare their similarities or their differences.

- Compare the typical or atypical (deviate from the norm).

Types of Case Studies: Descriptive vs. Causal

John Gerring (2017) suggests that the central question posed by the researcher dictates the aim of the case study. Is the study meant to be descriptive? If so, what is the researcher looking to describe? How many cases (countries, incidents, events) are there? Or is the study meant to be causal, where the researcher is looking for a cause and effect? Given this, Gerring categorizes case studies into two types: descriptive and causal.

Descriptive case studies are “not organized around a central, overarching causal hypothesis or theory” (pg. 56). Researchers simply seek to describe what they observe. They are useful for transmitting information regarding the studied political phenomenon. For a descriptive case study, a scholar might choose a case that is considered typical of the population, such as the effects of the pandemic on medium-sized cities in the US. This city would have to exhibit the tendencies of medium-sized cities throughout the entire country.

First, we would have to conceptualize what we mean by ‘a medium-size city’.

Second, we would then have to establish the characteristics of medium-sized US cities, so that our case selection is appropriate. Alternatively, cases could be chosen for their diversity . In keeping with our example, maybe we want to look at the effects of the pandemic on a range of US cities, from small, rural towns, to medium-sized suburban cities to large-sized urban areas.

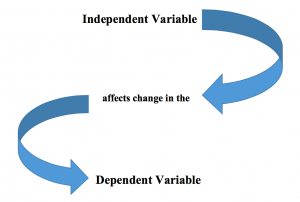

Causal case studies are “organized around a central hypothesis about how X affects Y” (pg. 63). The context around a specific political phenomenon allows for researchers to identify the aspects that set up the conditions, and the mechanisms for that outcome to occur. Scholars refer to this as the causal mechanism . Remember, causality is when a change in one variable verifiably causes an effect or change in another variable. Thus, Gerring divides the mechanisms into three categories. The differences revolve around how the central hypothesis is utilized in the study.

- Exploratory case studies are used to identify a potential causal hypothesis. Researchers will single out the independent variables that seem to affect the outcome, or dependent variable. Context is more about hypothesis generating as opposed to hypothesis testing. Case selection can vary widely depending on the goal of the researcher. For example, if the scholar is looking to develop an ‘ideal-type’, they might seek out an extreme case. Thus, if we want to understand the ideal-type capitalist system, we would investigate a country that practices a pure or ‘extreme’ form of the economic system.

- Estimating case studies start with a hypothesis already in place. The goal is to test the hypothesis through collected data/evidence. Researchers seek to estimate the ‘causal effect’. In other words, is the relationship between the independent and dependent variables positive, negative, or none existent.

- Diagnostic case studies help to “confirm, disconfirm, or refine a hypothesis” (Gerring 2017). Case selection can vary. For example, scholars can choose a least-likely case, or a case where the hypothesis is confirmed even though the context would suggest otherwise. A good example would be looking at Indian democracy, which has existed for over 70 years. India has a high level of ethnolinguistic diversity, is relatively underdeveloped economically, and has a low level of modernization through large swaths of the country. All of these factors strongly suggest that India should not have democratized, should have failed to stay a democracy in the long-term, or have disintegrated as a country.

Most Similar/Most Different Systems Approach

Single case studies are valuable as they provide an opportunity for in-depth research on a topic that requires it. However, in comparative politics, our approach is to compare. Given this, we are required to select more than one case. Challenges quickly emerge. First, how many cases do we pick? Second, how do we apply the case selection techniques, descriptive vs. causal? Do we pick two extreme cases if using an exploratory approach, or two least-likely cases if choosing a diagnostic case approach?

English scholar John Stuart Mill developed several approaches to comparison with the explicit goal of isolating a cause within a complex environment. Two of these methods, the 'method of agreement' and the 'method of difference' have influenced comparative politics.

- In the 'method of agreement', two or more cases are compared for their commonalities. The scholar looks to isolate the common characteristic, or variable, which is then established as the cause for their similarities.

- In the 'method of difference', two or more cases are compared for their differences. The scholar looks to isolate the characteristic, or variable, that the cases do not have in common.

From these two methods, comparativists have developed two approaches.

What Is the Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD)?

Derived from Mill’s ‘method of difference’, the Most Similar Systems Design Design (MSSD) compares cases but the outcomes differ in result. In this approach, an attempt is made to keep as many of the variables the same across the selected cases. Remember, the independent variable (cause) is the factor that doesn’t depend on changes in other variables. The dependent variable (effect) is affected by, or dependent on, the independent variable. In a most similar systems approach, the variables of interest should remain the same.

There is no national healthcare system in the United States. Meanwhile, New Zealand, Australia, Ireland, UK, and Canada have robust, publicly accessible national health systems. All these countries have similar systems: English heritage and language use, liberal market economies, strong democratic institutions, and high levels of wealth and education. Yet, despite these similarities, the end results vary. The US does not look like its peer countries.

Just for fun! Try your hand at some cause-and-effect scenarios:

Source: Upperelementary Snapshots

What Is the Most Different Systems Design (MDSD)?

In a Most Different System Design, the cases selected are different from each other, but result in the same outcome. Thus, the dependent variable is the same. Different independent variables exist between the cases, such as democratic v. authoritarian regime, liberal market economy v. non-liberal market economy. Or it could include other variables such as societal homogeneity (uniformity) vs. societal heterogeneity (diversity), where a country may find itself unified ethnically/religiously/racially, or fragmented along those same lines.

An example would be countries that are classified as economically liberal. The Heritage Foundation lists countries Singapore, Taiwan, Estonia, Australia, New Zealand, Switzerland, Chile, and Malaysia as either free or mostly free. Yet, these countries differ greatly from one another. Singapore and Malaysia are considered flawed or illiberal democracies (see chapter 5 for more discussion), whereas Estonia is still classified as a developing country. Australia and New Zealand are wealthy, Malaysia is not. Chile and Taiwan became economically free countries under authoritarian military regimes, which is not the case for Switzerland. In other words, why do we have different systems producing the same outcome?

- Previous Chapter

- Next Chapter

This chapter discusses the role of the most-similar systems design and most-different systems design in comparative public policy analysis. The methods are based on John Stuart Mill’s ‘eliminative methods of induction’ and regularly mentioned in educational books in social research methodology in general and in comparative politics in particular. However, their role has been less prominent in the literature on public policy. The methods are particularly useful in cross-country studies where the number of research units is limited, but where the researcher operates with a variable-oriented approach. The present contribution outlines how the most-similar systems design and the most-different systems design should be applied in deductive and inductive research efforts. It also challenges claims that the methods are unable to cope with interaction effects and multiple causation. The chapter also discusses to what extent the two methods are still relevant, given the recent advances made in multi-level modelling and in qualitative comparative analysis (OCA). Here, the argument is raised that the most-similar systems design and the most-different systems design are useful for accounting for complex social processes, and also have the advantage of making it possible to eliminate a large number of potentially relevant explanatory variables from further analysis. As a consequence thereof, regression models using multi-level techniques should often be constructed according to the logical foundations of a most-different systems approach in situations where the number of cases is low at the system level.

You are not authenticated to view the full text of this chapter or article.

Access options

Get access to the full article by using one of the access options below.

Other access options

Institutional Login

Log in with Open Athens, Shibboleth, or your institutional credentials

Table of Contents

- [66.249.64.20|109.248.223.228]

- 109.248.223.228

Character limit 500 /500

Building and Scaling a Design System in Figma: A Case Study

Building a design system for a multinational company means cataloging every component in meticulous detail. It’s a massive undertaking that calls for both a big-picture view and a focus on specifics. Here’s how one design system team leader accomplished it.

By Abigail Beshkin

Abigail is a veteran of Pratt Institute and Columbia Business School, where she oversaw the design and production team for Columbia Business magazine. Her work has appeared in the New York Times and been heard on NPR.

Determining how to build a design system for a multinational company means cataloging every component and pattern in meticulous detail. It’s a massive undertaking that calls for both a big-picture view and a focus on specifics. Here’s how one design system team leader accomplished it.

When Switzerland-based holding company ABB set out to create a design system , the goal was to knit together a consistent look and feel for hundreds of software products, many of which power the mechanical systems that keep factories, mines, and other industrial sites humming. It was no small task for a company with almost two dozen business units and nearly 150,000 employees around the world. For Abdul Sial , who served as the lead product designer on ABB’s 10-person design system team, scaling the library of components and patterns depended on maintaining openness and transparency, with an emphasis on extensive documentation.

The Role of a Design System Designer

Increasingly, large companies like ABB have teams dedicated exclusively to creating and maintaining design systems. “A design system allows for consistency, going to market in a fair time and not allowing production to get stuck on customizations that are not building value,” says Madrid-based designer Alejandro Velasco . Or, as Alexandre Brito , a designer in Lisbon, Portugal, explains, “Design systems come to provide structure whenever there are many people using the same set of tools. It’s like everyone having the same language.”

If a traditional style guide covers the design basics—fonts and colors, for instance—a design system has a much further reach. “A design system is a mix of a style guide, plus design components, design patterns, code components and, on top of it, documentation,” Sial says. When he worked on ABB’s design system, about 120 designers used it on a regular basis. The effort represented version 4.8 of the system, and the team dubbed it “Design Evolution.”

Design system designers play a different role than those who focus solely on individual products. “You have the bird’s-eye view of all the different products that a company is using,” Sial says.

Working in design operations also calls for communicating with stakeholders throughout a company. “Design system designers have to be social,” says Velasco. “A design system designer has to really like to work and talk with people who have different roles within an organization. They have to be able to distinguish what feedback to include in order to build the design system around the company’s needs.”

The Life Cycle of a Component

Working on ABB’s design system, Sial was guided by one overarching philosophy: “Documentation, documentation, documentation.” For every reusable element on ABB’s websites, mobile screens, or large stand-alone screens, Sial wanted to show what he calls the life cycle of a component. That meant extensive record-keeping for all components and patterns—breadcrumbs, headers, inputs, or buttons, to name just a few. “What are the journeys it went through? What decisions went into it? That way we’re not always recreating everything. Before trying something, you can read and see that someone already tested it,” Sial says.

In his experience, this philosophy is a departure from the typical approach to documentation. In the fast-paced world of product development, for example, documentation is often written at the end of the project or abandoned altogether. But for design systems, Sial says, documentation should be more than an afterthought. “A design system is never done; it needs continuous improvement,” he says. “Design system creators and consumers want to understand the thought processes and decisions in order to keep improving it.”

Documentation is especially important for a design system as large as ABB’s. “With such a large team you have to be able to scale,” he says. “How can we make sure that everybody who joins the team can quickly go to any component and understand how it started, how it was edited, and what version they are using?”

Finding the Right Tool

There are many tools out there for building design systems, including Figma, Sketch, and Adobe XD. Sial experimented with several, trying a mix of design and project management tools before settling on Figma, which offers ample space for documentation.

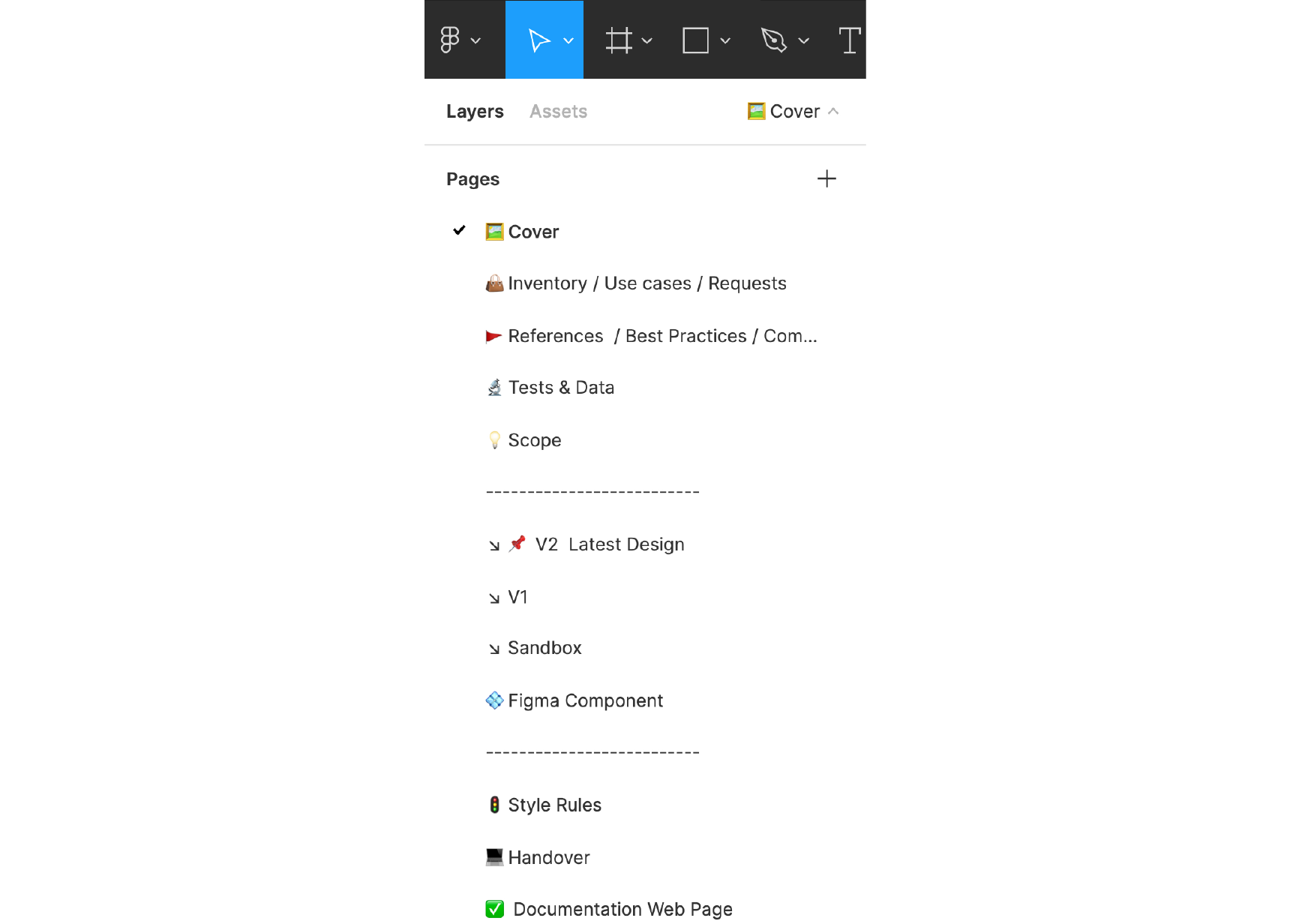

Sial and his team determined that every component should sit within its own file. “Most of the time, you’re working on one component at a time. If you put all the components in one file, it slows down Figma. By giving each component its own file, it’s quicker to open and you have the whole history and documentation in one place,” he says.

Setting the Hierarchy

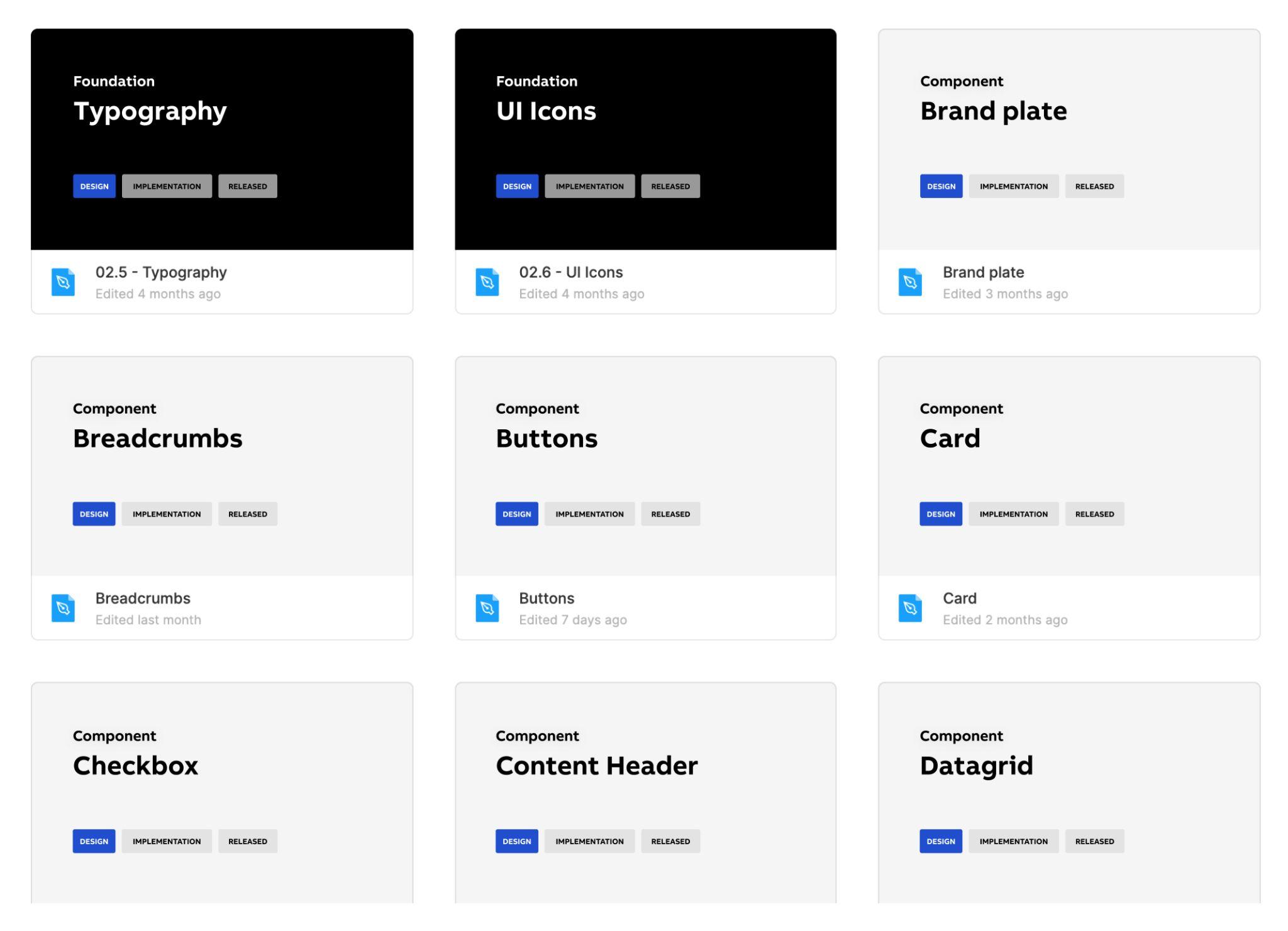

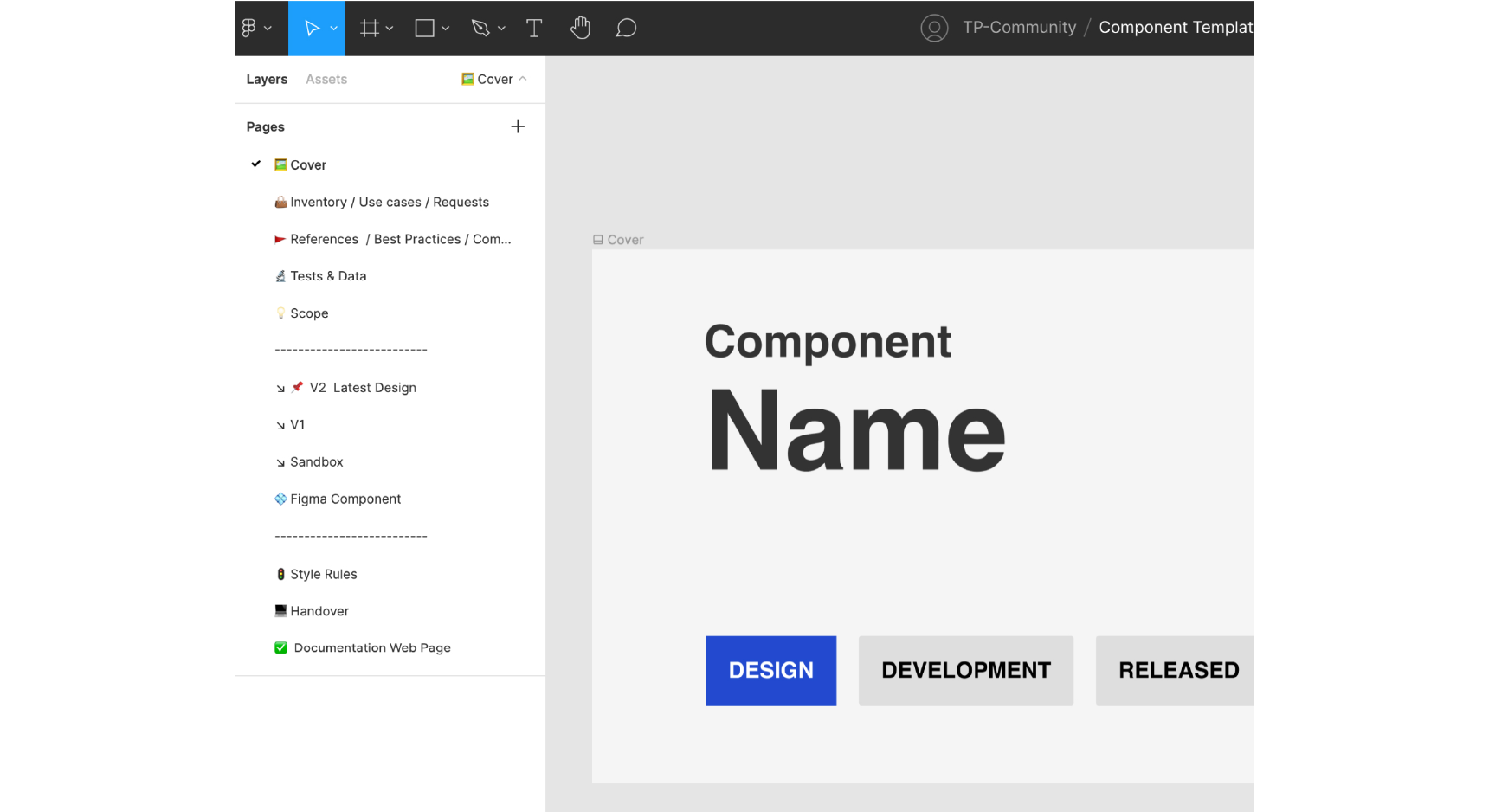

Sial set up the ABB design system so that the file for each component and pattern has the same pages. The images that follow detail what’s on each page.

Sial recommends setting up a simple cover page for every component. In Figma, this enables a thumbnail preview of all the components and helps with the browsability of files. In the ABB setup, the cover page includes the component name and what phase it’s in: design, development, or released. The status can be easily updated when the component progresses.

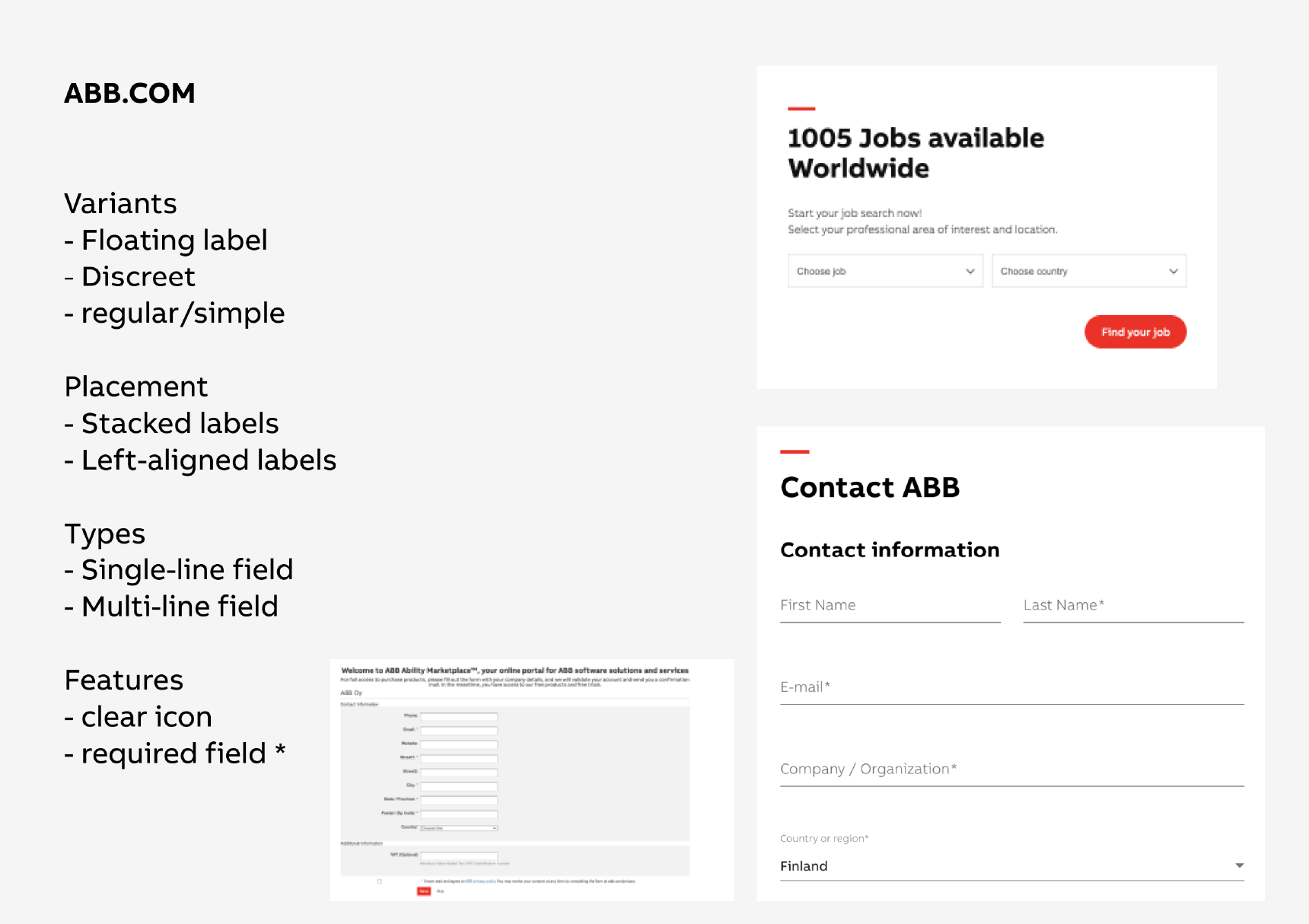

Inventory, Use Cases, and Requests

This page contains examples of the numerous ways that a component shows up in a company’s digital product. In the case of a text field component, for instance, the inventory page would show how the text field looks on abb.com compared to how it appears on an iPhone compared to how it shows up on an Android device. “The inventory allows us to understand clearly what’s already there,” says Sial.

This page should also show the ways the component is being used incorrectly. “This allows you to look at your products and see where there are alignments and misalignments,” Sial says. He advises teams launching a design system project to begin by cataloging what already exists. “Start with inventory and it will guide you as you’re creating the design,” he says.

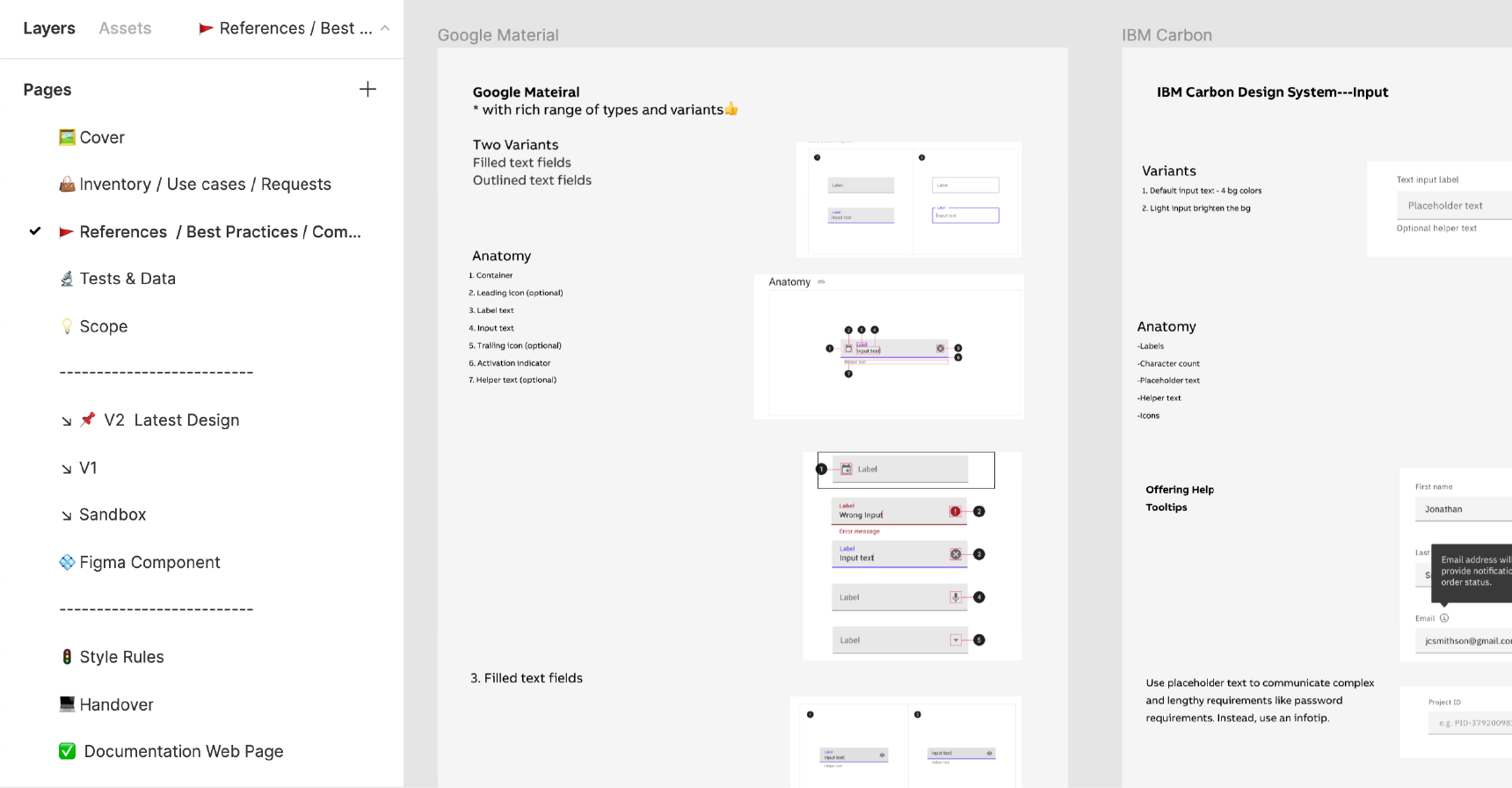

References, Best Practices, and Competitive Analysis

Sial advises creating a section of each component file akin to a vision board, showing how other companies design comparable pieces. “As with anything else, best practice is to perform competitive analysis and see how other people are doing it,” he says. “Observe other products and see their learnings.”

Tests and Data

The test results data page aggregates all the data related to testing a component, including the results of A/B testing and feedback from users and stakeholders. In short, Sial says, “It’s the whole story of a component.” Perhaps the design team tried a new variation two years ago and found it didn’t work? “Maybe we worked on that variation and we discarded it for some reason,” he says. If so, this kind of history can save significant time by making sure that designers don’t try it again.

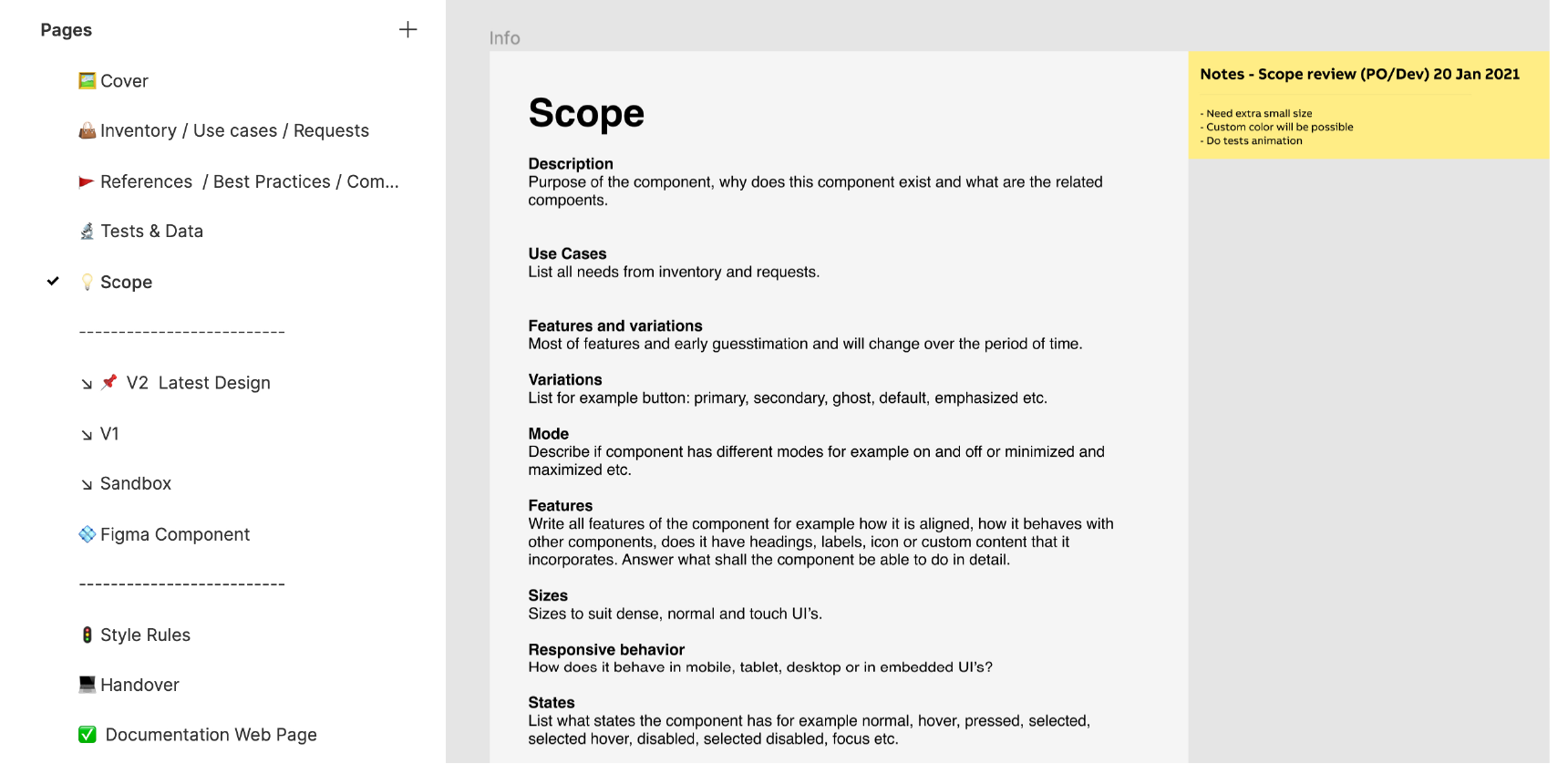

The next page lays out a component’s scope so designers can bring a design to fruition. By the time they arrive at the scope page, Sial says, “You have a story. You understand the inventory of all the products. You know what you need to build and you know the requirements. Now it’s time to write it down and make a brief out of it.” He adds that creating the scope should be a collaborative process with the product owners, developers, and designers.

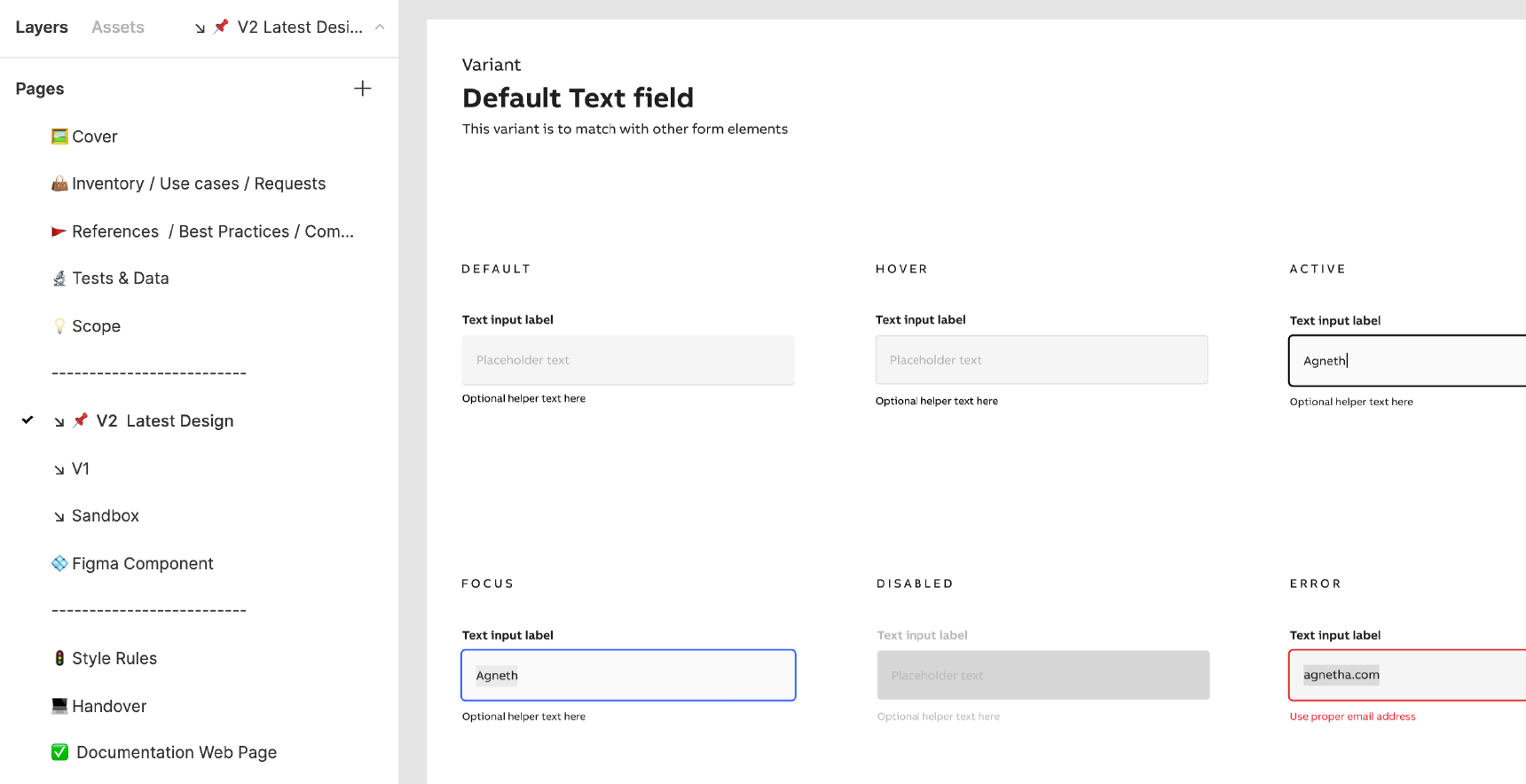

Images of the final versions of the component are found here, with the latest iteration pinned on top. Other designers should be able to review and comment on it.

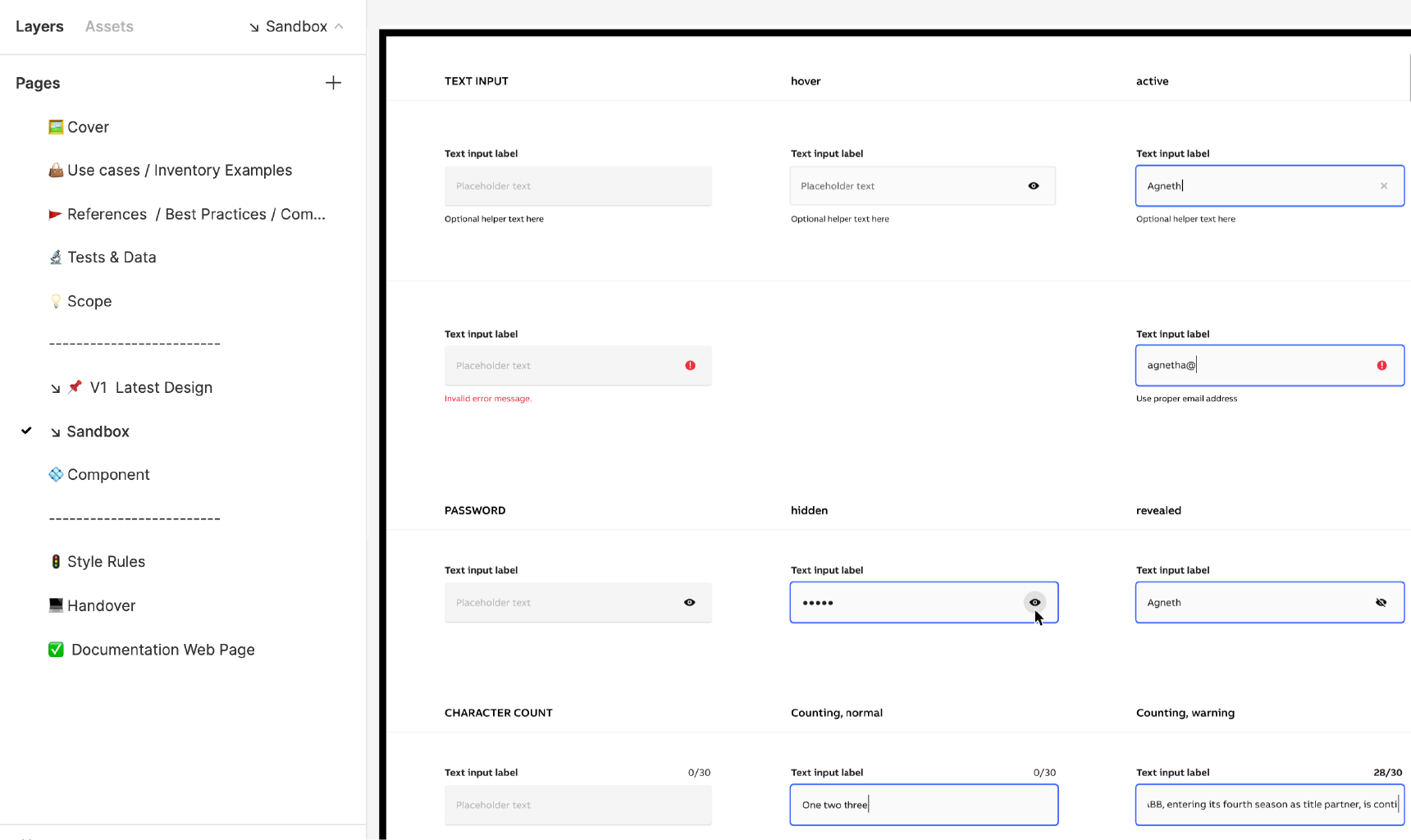

The sandbox enables designers to experiment with different iterations of a component or pattern directly in Figma. “It can be messy, and there’s no standardization,” Sial says. “It’s just a playground where a designer has the freedom to do anything.”

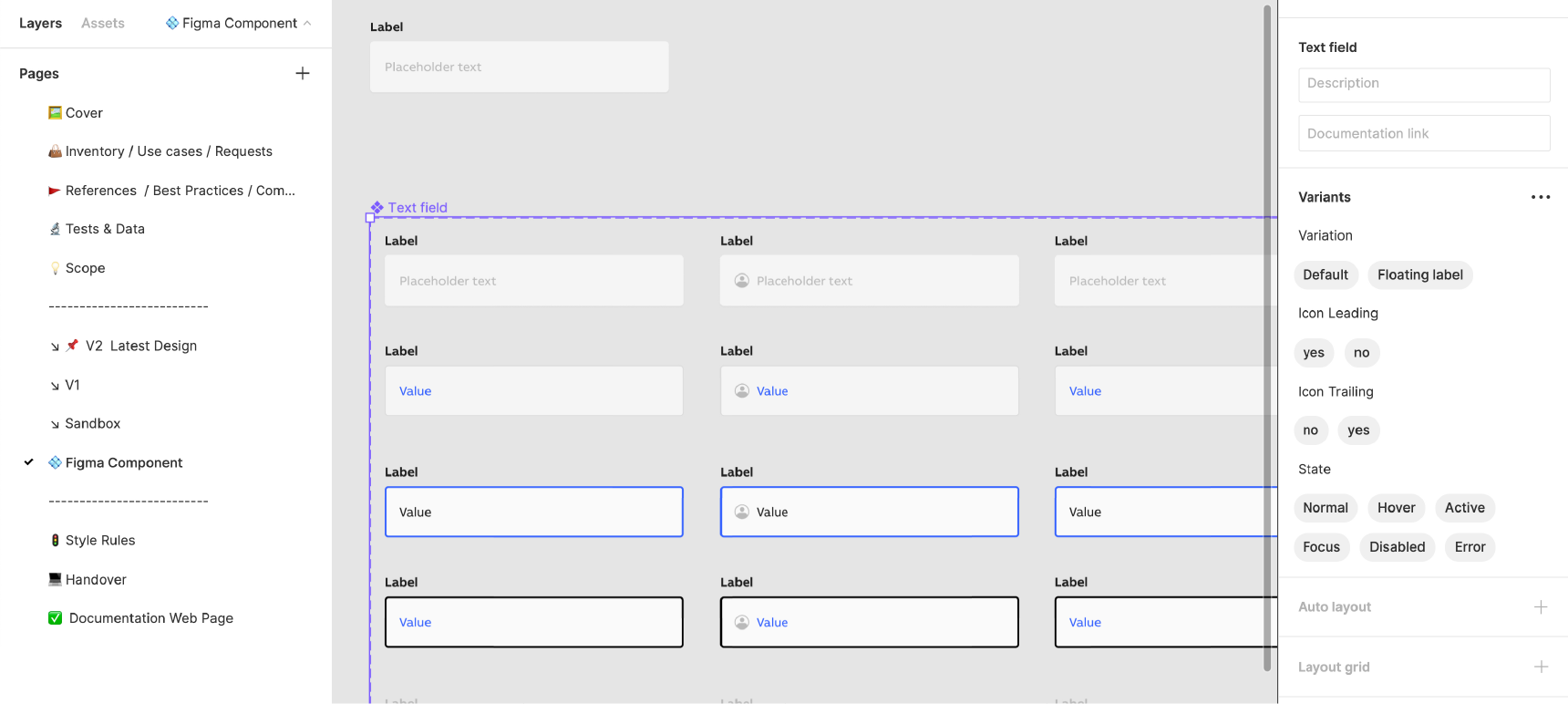

Figma Component

The file also contains a page for the Figma component itself, a UI element that is easily repeatable throughout the design system. The designer can make changes to the component, and that change will populate throughout all the instances of that component across the company, keeping everything consistent. This page will be exported to the Figma design system library, and any individual designer can drag and drop the Figma component into their design. If the design system team needs to make a change to the component, they can make it once and deploy it throughout the company.

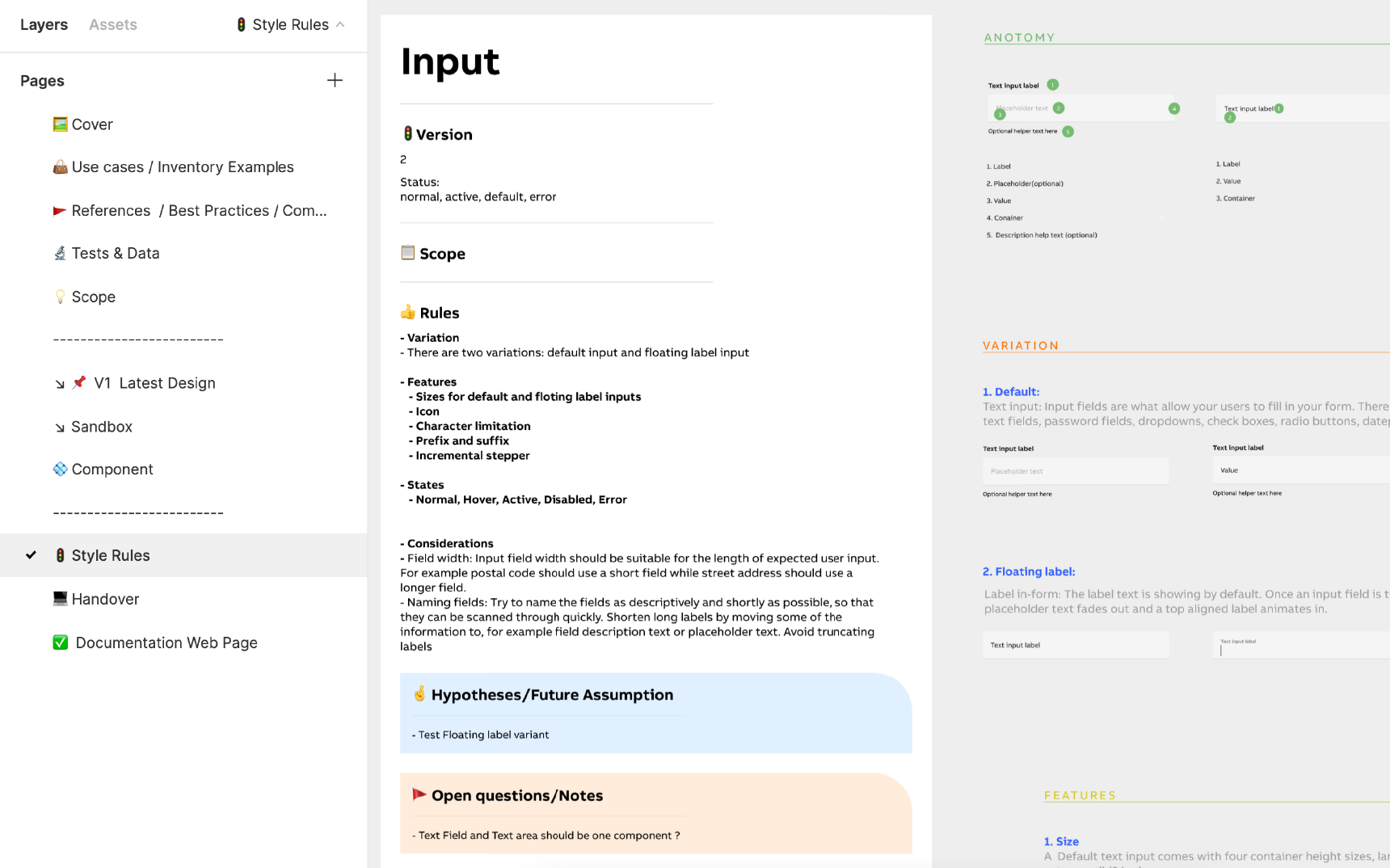

Style Rules

Next, the design system designers and developers create the style rules page, a kind of catch-all for elements that, Sial says, “are not visible in the design.” For example, how will the component render when you scroll down the page? It’s also where the design system team keeps track of unresolved questions or issues. He says he was surprised at how integral this page turned out to be: “At first, we thought this page was not that important, but now we realize we spend most of our time here.”

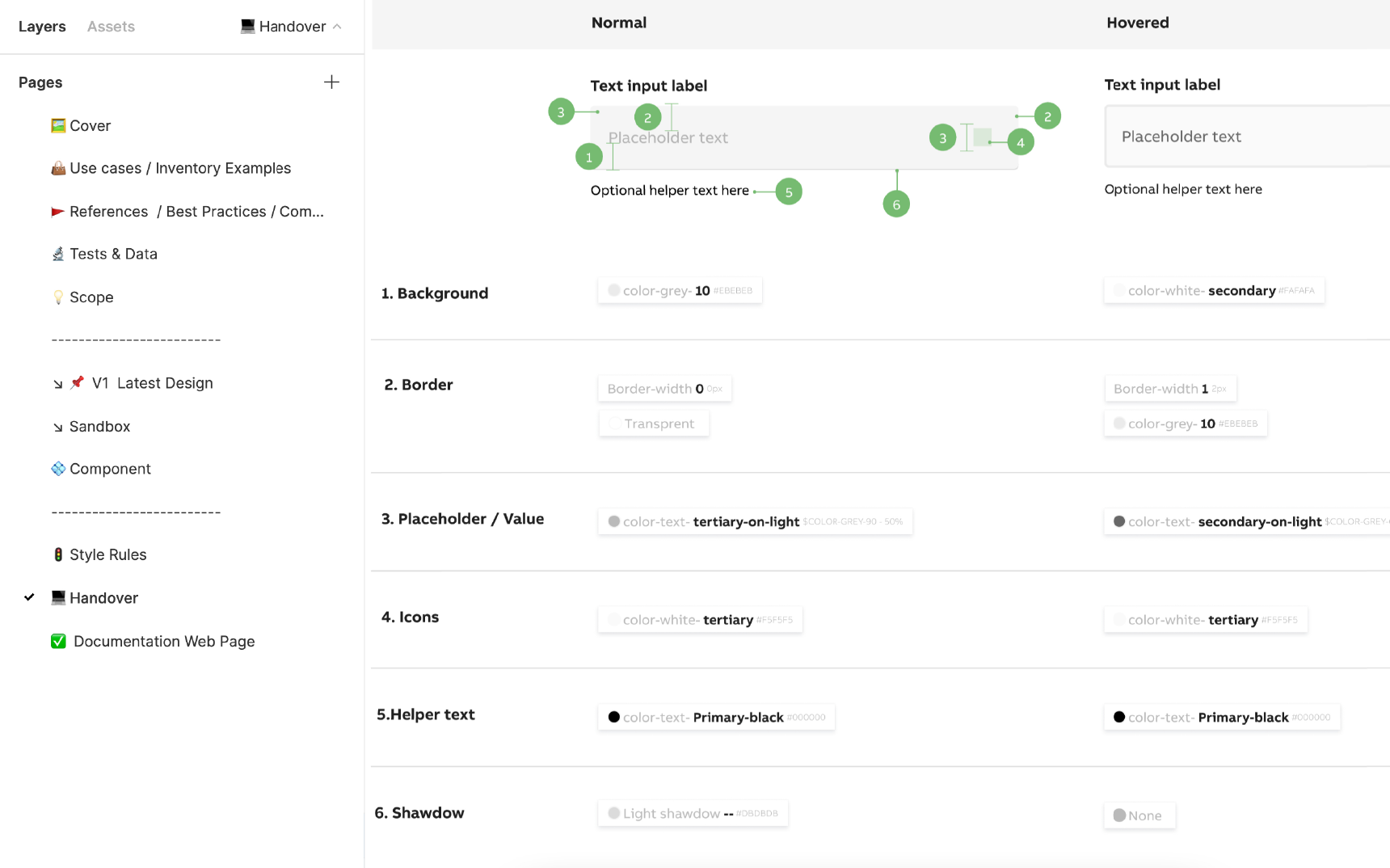

The handover notes are the instructions for developers on writing the code for the component. The handover document begins with the anatomy of the component, then includes its variations.

The ABB system handover documents also include design tokens . Becoming increasingly popular in large-scale design systems such as ABB’s, design tokens are pieces of platform-agnostic style information about UI elements, such as color, typeface, or font size. With design tokens, a designer can change a value—indicate that a call-to-action button should be orange instead of blue, for instance—and that change will populate everywhere the token is used, whether it is on a website, iOS, or Android platform.

Sial also created a Figma token plug-in to expand the scope of tokens designers can create in Figma. “Figma supports colors, typography, shadows, and grid styles,” he says. The plug-in will generate tokens for more variables, such as opacity and border width. It also creates a standardized naming convention, so designers don’t have to keep track of token names manually. “The plug-in bridges the gap between developers and designers. It allows both to work on a single source of truth for design; if one makes a change in one place, that change takes effect everywhere in the design and code,” he says.

Sial stresses that in his system, developers take an active role throughout the creation of a component. “Early on, we would involve our developers when we had something ready to show them,” he says. “Then we realized that’s not working, and now we literally start kickoff sessions with them.”

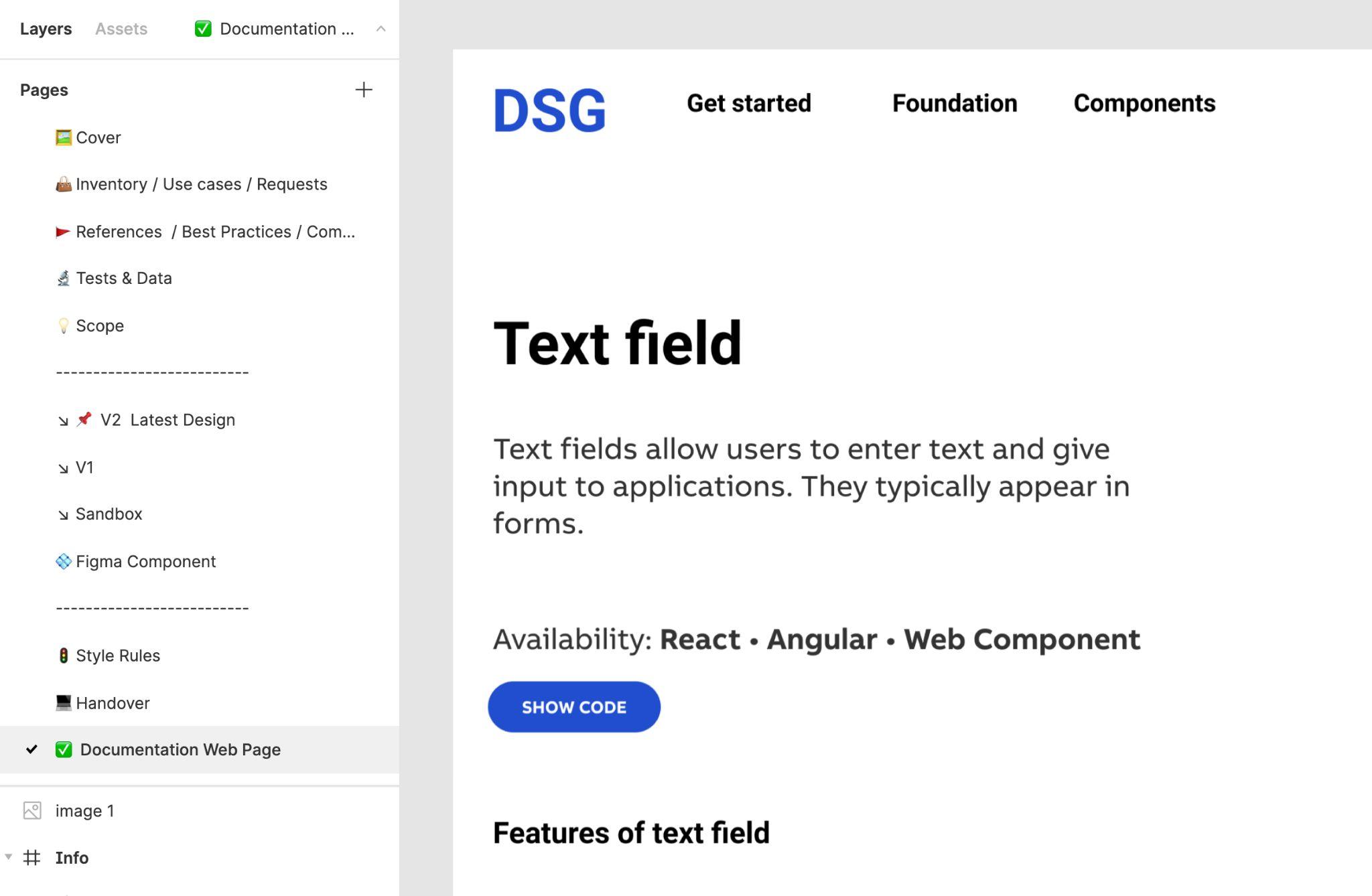

Documentation Webpage

The last page of each file contains a webpage with the final design, showing how the component looks as a finished product. “We create a page that shows how the live example will look so the users, in this case our designers, can see how it will look at the end of the day on a real website,” Sial says.

Collaboration Is Key

The role of a design system designer is multifaceted. As Alejandro Velasco says, “Designing a design system involves so many roles, and if I’m leading that, I’m the glue for the project.”

It’s an enormous undertaking and not necessarily the right move for all companies. Startups, for instance, might do better to begin with an out-of-the-box system such as Google Material Design or the IBM Carbon Design System , rather than dedicating extensive resources to creating one. Still, the time might come when that won’t suffice, says Alexandre Brito: “As soon as you have multiple designers working together, you start to realize that there’s a need for someone to build rules that are more in line with the product or brand you’re building.”

Building a design system takes work and dedication; it also takes collaboration. Sial stresses that involving all stakeholders in the development of ABB’s system throughout the process was a priority. “It was really iterative work with my whole team. It was all about listening to them and we took the time to learn and test it thoroughly and develop this structure,” he says.

Having a structure that includes extensive documentation, including history and best practices, is at the core of the Figma design system. “It’s a success because people can read the documentation all in one place,” Sial says. “They can see everything, starting from the use case to the design and moving on to the handover and the final component page. People can see the whole life cycle of a component.”

You can browse Abdul Sial’s Figma file in its entirety here: Component Template .

Further Reading on the Toptal Blog:

- Saving Product X: A Design Thinking Case Study

- All About Process: Dissecting Case Study Portfolios

- The Benefits of a Design System: Making Better Products, Faster

- Helping AI See Clearly: A Dashboard Design Case Study

- Design Problem Statements: What They Are and How to Frame Them

Understanding the basics

What is a design system.

While a traditional style guide covers the design basics—fonts and colors, for instance—a design system has a much further reach. The design system documentation for Switzerland-based holding company ABB, for example, contains design components, patterns, and code components.

What role does a design system designer play in an organization?

Design system designers play a different role than designers who focus solely on individual products. They tend to have more of a bird’s-eye view of all the products a company is using. They also must interface and communicate with stakeholders throughout a company.

What are some best practices when building a design system?

One approach is to organize it in Figma and give each component and pattern its own file. This design system case study demonstrates one approach: At ABB, each file has several pages with extensive documentation on all the ways the element is used throughout the product and all the iterations it went through. Showing the full life cycle of a component is key to building and scaling a design system.

- DesignProcess

World-class articles, delivered weekly.

Subscription implies consent to our privacy policy

Toptal Designers

- Adobe Creative Suite Experts

- Agile Designers

- AI Designers

- Art Direction Experts

- Augmented Reality Designers

- Axure Experts

- Brand Designers

- Creative Directors

- Dashboard Designers

- Digital Product Designers

- E-commerce Website Designers

- Full-Stack Designers

- Information Architecture Experts

- Interactive Designers

- Mobile App Designers

- Mockup Designers

- Presentation Designers

- Prototype Designers

- SaaS Designers

- Sketch Experts

- Squarespace Designers

- User Flow Designers

- User Research Designers

- Virtual Reality Designers

- Visual Designers

- Wireframing Experts

- View More Freelance Designers

Join the Toptal ® community.

Comparative methods

Tags_migration, old_description, description.

Comparative method is about looking at an object of study in relation to another. The object of study is normally compared across space and/or time. Comparative methods can be qualitative and quantitative. Often, there is a trade-off: the more cases to compare, the less comparable variables available and vice versa.

The comparative method is often applied when looking for patterns of similarities and differences, explaining continuity and change. Often applied in comparative research is the Most Similar Systems Design (that consists in comparing very similar cases that differ in the dependent variable, on the assumption that this will make it easier to find those independent variables which explain the presence/absence of the dependent variable) or the Most Different Systems Design (comparing very different cases, all of which have the same dependent variable in common, so that any other circumstance that is present in all the cases can be regarded as the independent variable).

A challenge in comparative research is that what may seem as the same category across countries may in fact be defined very differently in these same countries.

Nupi.no is using "cookies" to improve the quality of the website. For more information please read our Privacy Statement . By continuing to use our website, you accept our use of cookies.

Political and Social Science

Seminar 5: How to Select Cases and Make Comparisons

Introduction

Comparative case studies offer detailed insight into the causal mechanisms, processes, policies, motivations, decisions, beliefs and constraints facing actors – which statistics, large-scale surveys and cultural historiographies often struggle to explain.

As we discussed in week 1, case-oriented approaches place the integrity of the case, not variables, center-stage.

The language of variables, not the case, dominate the research process of variable-oriented comparative work. In case-oriented research the configuration of explanatory factors within-the-case is what matters, in terms of explaining the “outcome” of interest.

It is “Y” centred research.

What distinguishes the “case study approach” from “analytic narratives” is that the researcher operates from the assumption that their “case” reveals something about a broader population of cases. It shines a light on a bigger argument.

For example, generally, few people will care about your case on Ireland, Switzerland or Belgium, what they care about is it’s broader theoretical relevance.

Case selection

Since the case is often constructed on the basis of a specific outcome or theory of interest, case selection is purposive i.e. it is not based on random sampling. It is theory driven.

In case studies, researchers want to explain a given outcome such as the re-emergence of far-right politics in Europe, and therefore they must violate the statistical rule of “choosing cases on the dependent variable”.

But actively selecting cases (the dependent variable) can lead to accusations of selection bias. How can purposive case selection be justified?

Political scientists require methodological justification for their case selection. It is not sufficient to say you are studying Irish politics because you speak the language and know the country. Nor is it sufficient to pick a case in order to ‘prove’ your theoretical claim.

What is your case study a case of?

The central question facing any case study researcher is “ what is my case a case study of ?”. Small N qualitative case studies inform the scholarly community about something larger than the case itself, even if the case cannot result in a complete generalization.

Case studies make a powerful contribution toward theory testing and theory building, something we will discuss in more detail in week 7.

Usually it is assumed that case studies are “countries”. But they can be anything from a person, a time period, a company, an event, a decision or a public policy.

What matters is how you construct the case study.

But what is a case? Is it an observation?

Methodologically, case studies should be bounded in time and space, related to a wider population of cases, and theoretically relevant.

Depending on the research question you are asking, or the puzzle that interests you, cases can be:

- Identified and established by the researcher (networks of elite influence)

- Objects that exist independently of the researcher (nation-states)

- Theoretically constructed by the researcher (benevolent tyranny)

- Theoretically accepted conventions (post-industrial societies)

Hancké (2009) uses the example of the Law and Justice Party in Poland, from 1995-2005, as a case study of rising populism in Eastern Europe. The case study is an in-depth analysis of the causal mechanisms that enabled populism to emerge in Poland, but it is framed against a broader universe of cases: the rise of populism in central and eastern Europe.

Single case studies

The weakest case studies are perhaps those selected to illustrate a theory.

A case study that challenges a scholarly community to think differently about the relevant dimensions of an existing theory is a much better contribution to social science debate.

These type of cases are often called “critical” or “crucial” case studies.

In terms of single case studies, casual process-tracing is the most widely used methodological strategy in political science. Causal process-tracing (which we will spend an entire seminar in week 9 on) attempts to unpack the precise causal chain or intermediate steps, or set of functional relationships, leading x to cause y.

They actively select their dependent variable in to trace the causal process leading x-y.

This is why we describe small N case study research as ‘purposive’. Researchers purposively select their case in order to explain a given “outcome” of interest.

Casual mechanism

For example, if we say that “democratic countries are wealthier”, we could unpack the causal mechanism into the following steps (with distinct empirical observations):

- Step 1: the median voter in a market economy has an income below the median

- Step 2: these voters support and elect parties that redistribute income

- Step 3: this redistribution leads to higher spending among the low-income majority

- Step 4: this results in higher consumption and aggregate demand

- Step 5: higher aggregate demand leads to higher employment and economic growth

This is not designed to be an empirical statement of fact. It is a reconstruction of a purported causal mechanism. Most importantly, each step can be empirically tested, against other proposed theories on why democracies are wealthier.

This is an essential point. In case study research, one needs a counter-factual, and an engagement with an alternative hypotheses/explanations for the same outcome. It’s not simply a matter of “telling a story” or a “I told you so argument”.

Critical case studies

Critical or crucial case studies challenge an existing theory.

Imagine you find a case where all existing theories suggest that given conditions X1, X2, X3, X4, we should expect to find a specified outcome Y1. Instead, we find a case with the opposite outcome.

Centralized wage-setting in a liberal market economy: the case of Ireland.

The researcher engages an existing theory, stacks the cards against herself, and then explains why the existing theory cannot explain the aberration observed.

It is not designed to generalize but to problematize.

Consider another example, almost all OECD countries experienced the common shock of declining interest rates and the expansion of cheap credit, but not every country experienced the emergence of an asset-price or housing bubble.

The same pressure in different institutional settings lead to different outcomes. Why?

Most different/most similar

Case studies are hard work and require a lot of careful reasoning by the researcher to ensure they are making valid comparisons that meaningfully speak to a wider population of cases, and which are of theoretical interest to a broader scientific community.

The most powerful techniques of comparison in the qualitative case study approach are those that make the dimensions of their case studies explicit.

The basic idea behind this approach originates in John Stuart Mills “ A System of Logic “, and it’s usually referred to as the “ Method of Difference ” and “ Method of Agreement ” approach.

Alternatively, it is often referred to as a “ most different or most similar ” research design.

In the method of difference you select cases that are similar in every relevant characteristic expect for two: the outcome you are trying to explain (y – dependent variable ), and what you think explains this outcome (x – independent variable ).

Table 1 illustrates the logical structure of this comparative approach.

Examine the table. In this analysis, what explains the variation in house price inflation between case A (Ireland) and case B (Netherlands)?

Table 1: Method of Difference

The method of agreement works the other way around: everything between the two cases is different except for the explanation (x) and the outcome (y) .

Table 2 illustrates the logical structure in this type of comparative analysis.

What explains the collapse of social partnership in Ireland and Italy in this example?

Table 2: Method of Agreement

Conclusion

The essential point to remember – and the main takeaway of this seminar – is that you need to defend your case selection, and think systematically about your comparisons.

Causal process tracing is a technique that will enable you to do this (week 8/9).

Gerring & Seawright (2008) suggest 7 case selection procedures, each of which facilities a different strategy for within-case analysis. These case selection procedures are:

- Typical (cases that confirm a given theory)

- Diverse (cases that illuminate the full range of variation on X, Y or X/Y)

- Extreme (cases with an extremely unusual values on X or Y)

- Deviant (cases that deviate from an established cross-case population)

- Influential (cases with established and influential configurations of X’s)

- Most similar (cases are similar on all variables except X1 and Y)

- Most different (cases are different on all variables except X1 and Y)

I would add “crucial or critical” cases to this list (cases that problematise a theory).

Discuss these case selection procedures and their methodological justification, and identify which is most appropriate to your research design.

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply.

- Already have a WordPress.com account? Log in now.

- Subscribe Subscribed

- Copy shortlink

- Report this content

- View post in Reader

- Manage subscriptions

- Collapse this bar

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

6 Chapter 8: Comparative Politics

Comparative politics centers its inquiry into politics around a method, not a particular object of study. This makes it unique since all the other subfields are orientated around a subject or focus of study. The comparative method is one of four main methodological approaches in the sciences (the others being statistical method, experimental method, and case study method). The method involves analyzing the relationship between variables that are different or similar to one another. Comparative politics commonly uses this comparative method on two or more countries and evaluating a specific variable across these countries, such as a political structure, institution, behavior, or policy. For example, you may be interested in what form of representative democracy best brings about consensus in government. You may compare majoritarian and proportional representation systems, such as the United States and Sweden, and evaluate the degree to which consensus develops in these governments. Conversely, you may take two proportional systems, such as Sweden and the United Kingdom, and evaluate whether there is any difference in consensus-building among similar forms of representative government. Although comparative politics often makes comparisons across countries, it can also conduct comparative analysis within one country, looking at different governments or political phenomena through time.

The comparative method is important to political science because the other main scientific methodologies are more difficult to employ. Experiments are very difficult to conduct in political science—there simply is not the level of recurrence and exactitude in politics as there is in the natural world. The statistical method is used more often in political science but requires mathematical manipulation of quantitative data over a large number of cases. The higher the number of cases (the letter N is used to denote number of cases), the stronger your inferences from the data. For a smaller number of cases, like countries, of which there is a limited number, the comparative method may be superior to statistical methodology. In short, the comparative method is useful to the study of politics in smaller cases that require comparative analysis between variables.

Most Similar Systems Design (MSSD)

This strategy is predicated on comparing very similar cases which differ in their dependent variable. In other words, two systems or processes are producing very different outcomes—why? The assumption here is that comparing similar cases that bring about different outcomes will make it easier for the researcher to control factors that are not the causal agent and isolate the independent variable that explains the presence or absence of the dependent variable. A benefit of this strategy is that it keeps confusing or irrelevant variables out of the mix by identifying two similar cases at the outset. Two similar cases implied a number of control variables—elements that make the cases similar—and very few elements that are dissimilar. Among those dissimilar elements is likely your independent variable that produced the presence/absence of your dependent variable. A downside to this approach is that when comparing across countries, it can be difficult to find similar cases due to a limited number of them. There can be a more strict or loose application of the MSSD model—similarities may be fairly exact or roughly the same, depending on the characteristic involved, and will influence your research project accordingly.

Example 8.1

Suppose you want to study how well forms of representative government develop consensus and agreement over policy matters. You may observe that nearly identical representative systems of government exist in County A and Country B, but are producing very different results.

- Country A has a proportional representation system and has a long and successful track record of producing consensus among lawmakers over a number of policy issues.

- Country B, however, is riddled with partisan disagreement and a lack of consensus over a similar kind and number of policy issues.

In this instance, you may also observe a number of similarities that act as control variables in your research—both countries have a bicameral legislature, a similar number of representatives per capita. This is a research project well suited to the MSSD approach, as it allows multiple control points (proportional representation, bicameral legislature, number of representatives, etc.) and allows for the researcher to focus on fine grain points of difference among the cases. You may observe in this example one intriguing difference in demographics—County A’s population is smaller and largely homogenous, whereas Country B’s population is larger and more diverse. It may be that in Country B this diverse population is well represented in the legislature but leads to more policy disputes and a relative lack of consensus when compared to Country A.

Most Different Systems Design (MDSD)

This strategy is predicated on comparing very different cases that are all have the same dependent variable. This strategy allows the research to identify a point of similarity between otherwise different cases and thus identify the independent variable that is causing the outcome. In other words, the cases we observe may have very different variables between them yet we can identify the same outcome happening—why do we have different systems producing the same outcome? The task is to then sift through the variables existing between the cases and isolate those that are in fact similar, since a similar variable between the cases may in fact be the causal agent that is producing the same outcome. An advantage to the MDSD approach is that it doesn’t have as many variables that need to be analyzed as the MSSD approach does—a researcher only needs to identify the same variable that exists across all different cases. The MSSD approach, on the other hand, tends to have a lot more variables that have to be considered although it may provide a more precise link between the independent and dependent variables.

Example 8.2

Let’s use an example that will help illustrate the MDSD approach. Suppose you observe two very different forms of representative government producing the same outcome: Country A has a majoritarian, winner-take-all representational system and Country B has a proportional representation system, yet in both countries there is a high degree of efficiency and consensus in the legislative process.

Why do two systems have the same outcome?

You may list a number of variables and compare them across the two cases, sifting through to locate similar variables. Unlike the MSSD approach, which seeks to locate different variables across similar cases, the MDSD approach is the opposite—the task is to locate similar variables across different cases. You may observe that despite the fact that these two countries have very different systems of representation, both have unicameral legislatures and a low number of representatives per capita. These factors may produce higher levels of efficiency and consensus in the legislative process, thus explaining the same dependent variable despite different cases.

The Nation-State

Much of comparative politics focuses on comparisons across countries, so it is necessary to examine the basic unit of comparative politics research—the nation-state.

A nation is a group of people bound together by a similar culture, language, and common descent, whereas a state is a political sovereign entity with geographic boundaries and a system of government. A nation-state, in an ideal sense, is when the boundaries of a national community are the same as the boundaries of a political entity. In this sense, we may say that a nation-state is a country in which the majority of its citizens share the same culture and reflect this shared identity in a sovereign political entity located somewhere in the world. Nation-states are therefore countries with a predominant ethnic group that articulates a culturally and politically shared identity. As should be apparent, this definition has some gray areas—culture is fluid and changes over time; migration patterns can change the make up of a nation-state and thus influence cultural and political changes; minority populations may substantially contribute to the characteristics that make up a shared national identity, and so on.

Nations may include a diaspora or population of people that live outside the nation-state. Some nations do not have states. The Kurdish nation is an example of a distinct ethnic group that lacks a state—the Kurds live in a region that straddles the borders of Turkey, Iraq, Syria, and Iran. Some other examples of nations without states include the numerous indigenous nations of the Americas, the Catalan and Basque nations in Spain, the Palestinian people in the Middle East, the Tibetan and Uyghur people in China, the Yoruba people of West Africa, and the Assamese people in India. Some previously stateless nations have since attained statehood—the former Yugoslav republics, East Timor, and South Sudan are somewhat recent examples. Not all stateless nations seek their own state, but many if not most have some kind of movement for greater autonomy if not independence. Some autonomous of breakaway regions are nations that have by force exercised autonomy from another country that claims that region. There are many such regions in the former Soviet Union: Abkhazia and South Ossetia (breakaway regions from Georgia), Transdniestria (breakaway region from Moldovia), Nagorno-Karabagh (breakaway region from Azerbaijan), and the recent self-declared autonomous provinces of Luhansk and Donetsk in the Ukraine. Most of these movements for autonomy are actively supported by Russia in an effort to control their sphere of influence. Abkhazians, South Ossetians, Trandniestrians, and residents of Luhansk and Donetsk can apply for Russian passports.

Lastly, some countries are not nation-states either because they do not possess a predominate ethnic majority or have structured a political system of more devolved power for semi-autonomous or autonomous regions. Belgium, for example, is a federal constitutional monarchy with a parliamentary system with three highly autonomous regions: Flanders, Wallonia, and the Brussels capital region. The European Union is an interesting case of a supra-national political union of 28 states with a standardized system of laws and an internal single economic market. An outgrowth of economic agreements among Western European countries in the 1950s, the EU is today one of the largest single markets in the world and accounts for roughly a quarter of the global economic output. In addition to a parliament, the EU government, located in Brussels, Belgium, has a commission to execute laws, a courts system, and two councils, one for national ministers of the member states and the other for heads of state or government of the member states. The EU’s complicated political system allows for varying and overlapping levels of legal and political authority. Some member states have anti-EU movements in their countries that broadly share a concern over a loss of political and cultural autonomy in their country. The United Kingdom’s decision to leave the EU, known as “Brexit,” has been a complex and controversial process.

As this brief overview suggests, the concept of a nation-state is central to global politics. Crucial questions on what constitutes a nation-state underpin many of the most significant political conflicts in the world. Autonomous movements that seek greater sovereignty for a particular nation are found in every region of the world. At the heart of the relationship between nations and states is the idea of self-determination—that distinct cultural groups should be able to define their own political and economic destiny. Self-determination as a conception of justice suggests that freedom is not just individual but also communal—the freedom of defined groups to autonomy and self-direction.

Self-determination as a conception of justice suggests that freedom is not just individual but also communal—the freedom of defined groups to autonomy and self-direction.

The push and pull of power that brings nations together or tears them apart is everywhere in global politics. Moreover, states may appear stronger than they actually are, as the unexpected fall of the Soviet Union suggests. The legitimacy of the state and the cohesiveness of a nation go a long way toward understanding stability in the global world.

Comparing Constitutional Structures and Institutions

In Chapter Four we provided an overview of constitutions as a blueprints for political systems and in Chapter Three’s focus on political institutions we discussed legislative, executive, and judicial units and powers such as unicameral or bicameral legislatures, presidential systems, judicial review, and so on. The relationship between similar and different institutional forms make up the nuts and bolts of comparative political inquiry. In comparing constitutions across countries, each constitution speaks to the unique characteristics of a political community but there are also similarities. Constitutions typically outline the nature of political leadership, structure a form of political representation, provide for some form of executive authority, define a legal system for adjudicating law, and authorize and limit the reach of government power. On the other hand, there are several unique factors that determine a constitution an government. Geography, for example, often has a profound impact on the constitutional structure and form of government.

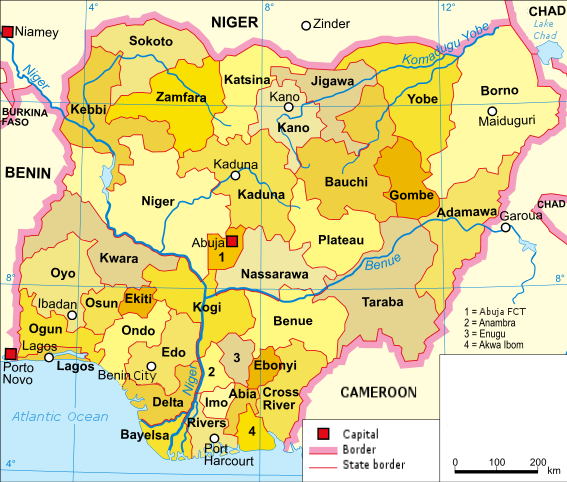

Large countries with scattered populations, for example, must be more sensitive to the legitimacy of the state in regions far removed from the center of government power. Some governments have moved their seat of power to more centralized and less populous cities in response to this concern—Abuja, Nigeria, Canberra, Australia, Dodoma, Tanzania, Yamoussoukro, Côte d’Ivoire, Brasilia, Brazil and Washington DC in the United States are examples of capital cities founded as a more central location in order to better balance power among competing regions.

Another factor is social stratification—differentiation in society based on wealth and status. What is typically regarded as lower, middle, and upper classes in most developed societies, social stratification can be complex, overlapping, and influenced by a variety of group characteristics such as race or ethnicity and gender. Social stratification can lead to political stratification—differing levels of access, representation, influence, and control of political power in government. This derived power can in turn reinforce social stratification in various ways. For example, the wealthy and privileged of a country may have derived political power from their wealth and in turn shape and influence government in such a way as to protect and increase their wealth, influence, and privilege. With the comparative method of political inquiry, political scientists can study the degrees to which social stratification effects political processes across countries. This kind of comparative inquiry can yield important insights such as whether wealth derived from group characteristics leads to greater political stratification than wealth derived across more diverse groups, or whether reforms directed at lessening political stratification have any effect on social stratification.

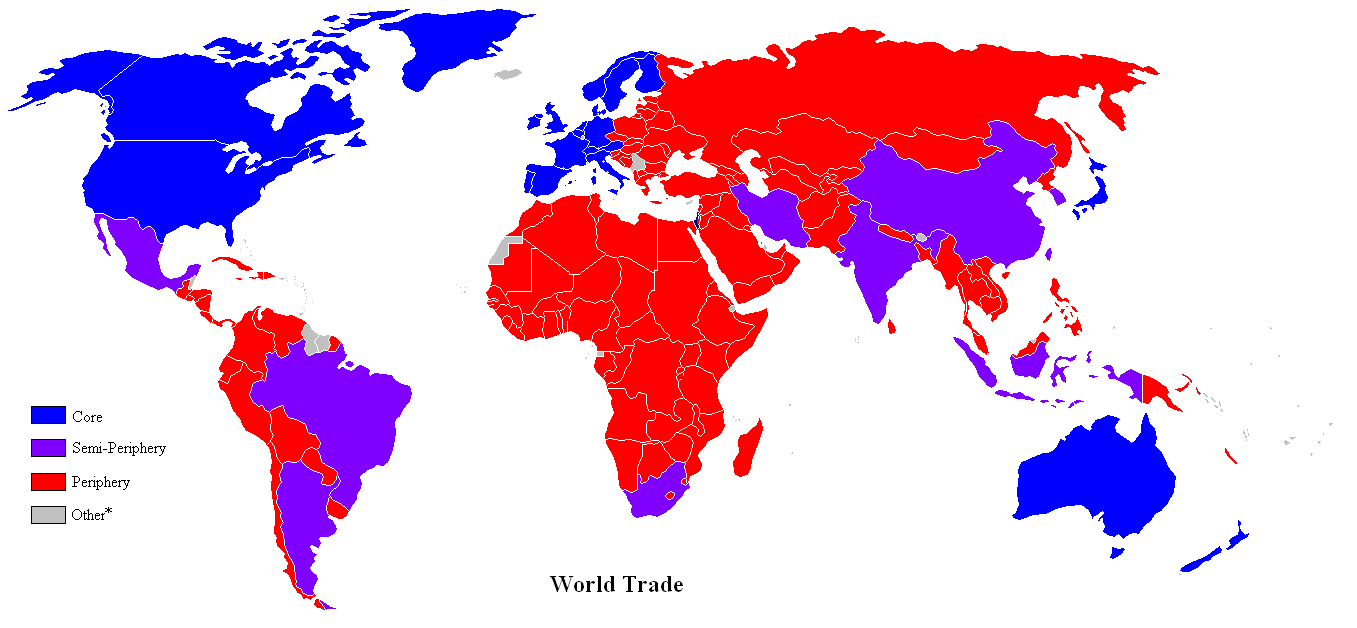

Lastly, global stratification suggests when looking at the global system, there is an unequal distribution of capital and resources such that countries with less powerful economies are dependent on countries with more powerful economies. Three broad classes define this global stratification: core countries, semi-peripheral countries, and peripheral countries. Core countries are highly industrialized and both control and benefit from the global economic market. Their relationship to peripheral countries is typically predicated on resource extraction—core countries may trade or may seek to outright control natural resources in the peripheral countries. Take as an example two open pit uranium mines located near Arlit in the African country of Niger. Niger, one of the poorest countries in the world, was a former colony of France. These mines were developed by French corporations, with substantial backing from the French government, in the early 1970s. French corporations continue to own, process, and transport uranium from the Arlit mines. The vast majority of the uranium needed for French nuclear power reactors and the French nuclear weapons program comes from Arlit. The mines have completely transformed Niger in a number of ways. 90% of the value of Niger’s exports come from uranium extraction and processing, leading to what some economists call a “resource curse”—a situation in which an economy is dominated by a single natural resource, hampering the diversification of the economy, industrialization, and the development of a highly skilled workforce.

Semi-periphery countries have intermediate levels of industrialization and development with a particular focus on manufacturing and service industries. Core countries rely on semi-peripheral countries to provide low cost services, making the economies of core and semi-peripheral countries well integrated with one another, but also creating an economic situation in which semi-peripheral countries become increasingly dependent on consumption in core countries and the global economy generally, sometimes at the expense of more economic self-sufficient and sustainable development. As an example, let’s consider Malaysia, a newly industrialized Asian country of over 40 million people. Malaysia has had a GDP growth rate of over 5% for 50 years. Previously a resource extraction economy, Malaysia went through rapid industrialization and is currently a major manufacturing economy, and is one of the world’s largest exporters of semi-conductors, IT and communication equipment, and electrical devices. It is also the home country of the Karex corporation, the world’s biggest producer of condoms.

Included among core countries are the United States and Canada, Western Europe and the Nordic countries, Australia, Japan, and South Korea. Semi-peripheral countries include China, India, Russia, Iran, Malaysia, Indonesia, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, and South Africa. Periphery countries include most of Africa, the Middle East, Central America, Eastern Europe, and several Asian countries. Reflect on the relationship between core, semi-peripheral, and peripheral countries. Do you think this relationship is predicated more on exploitation and control or mutually beneficial economic partnerships in a global environment? Choose three countries—one core, one semi-peripheral, and one peripheral—that have political and economic ties to one another. Evaluate and analyze relations between these countries. What are the prominent economic interactions? What best characterizes the diplomacy and political relations between these countries? Are the forms of government similar or different?

The Value of Languages and Comprehensive Knowledge

Comparative politics arguably requires more comprehensive knowledge of countries, political systems, cultures, and languages than the other sub-disciplines in political science. Language skill, in particular, is often essential for the comparativist to conduct good research. Having some facility with languages spoken in the countries or regions central to the research project gives researcher access to information and opens up avenues of communication and knowledge that is needed for in-depth understanding.

In conducting field research, knowledge of local languages is critically important. Conducting interviews and doing observations in the field require familiarity with common languages spoken in the area. Grants are available from the US State Department and academic institutions for graduate students (and in some cases promising undergraduates) for language programs. The best environment for learning a foreign language is immersive—ideally, students should spend time in areas they have research interests in to gain familiarity with the language(s) and cultural practices. For example, if one wanted to conduct a comparative research project on political development in Kosovo and Abkhazia—two breakaway autonomous republics of similar size and population that are key sites of the geopolitical struggle between the West and Russia—it would be necessary to have some familiarity with Albanian (the dominant language of Kosovo) and Abkhaz, but it may also be helpful to have some exposure to Serbian, Russian, and Georgian as well.

Comparativists should ideally have broad but deep knowledge of the world—understanding regional issues, environmental resources, demographics, and relations between countries provides a pool of general knowledge that can help comparativists avoid obstacles while conducting their research. For example, if one were conducting a study on the relationship between women’s access to contraceptives and the percent of women in the workforce with a data set of some 150 countries, it is useful to know that in the non-Magreb countries of Africa women make up a disproportionately large percentage of agricultural labor. Despite low access to contraceptives, sub-Saharan African countries have relatively high percentages of women in the work force due to the cross-cultural norm of women farmers.

Field Research in Comparative Politics

A crucial component of doing comparative politics is field research—the collection of data or information in the relevant areas of your research focus. Where political theory is akin to the discipline of philosophy, comparative politics is akin to anthropology in this field research component. Comparativists are encouraged to “leave the office” and bring their research out into the relevant areas in the world. Being on the ground affords the researcher a firsthand perspective and access to the sources that underpin good comparative analysis. Conducting surveys with local respondents, doing interviews with key actors in and out of government, and making participant observations are some common methods of gathering evidence for the field researcher. To continue with the above example of Kosovo and Abkhazia, suppose a researcher was interested in comparing constitutional development and reform in the two republics. Interviews with key actors in developing those respective constitutions would provide a firsthand account of the process, while surveys conducted with local responses could measure the degree of support for key reforms. A researcher could also conduct participant observations of the legislative process, media events, or council meetings.

Being in the field always comes with surprises that may alter the research project in numerous ways. Poor infrastructure may hamper travel. Corruption may create obstacles in survey work or interviews. Locals may be unwilling to work with a foreign researcher whose intentions are in doubt. It is always important to balance your ideal research project with the practical realities you find on the ground. Deciding whether to take a short or long trip abroad is also an important consideration—shorter trips may bring more focus and efficiency to your work and also afford more opportunity to identify points of comparison and contrast, whereas longer trips can be more open-ended and immersive, giving the researcher the opportunity to develop contacts and and have a more in-depth cultural experience. Lastly, case selection and sampling are important considerations—macro-level case selection involves identifying a country to conduct field work; meso-level selection involves locating relevant regions or towns; micro-level selection involves identifying individuals to interview or specific documents for content analysis.

Comparative politics is more about a method of political inquiry than a subject matter in politics. The comparative method seeks insight through the evaluation and analysis of two or more cases. There are two main strategies in the comparative method: most similar systems design, in which the cases are similar but the outcome (or dependent variable) is different, and most different systems design, in which the cases are different but the outcome is the same. Both strategies can yield valuable comparative insights. A key unit of comparison is the nation-state, which gives a researcher relatively cohesive cultural and political entities as the basis of comparison. A nation-state is the overlap of a definable cultural identity (a nation) with a political system that reflects and affirms characteristics of that identity (a state).

In comparing constitutions and political institutions across countries, it is important to analyze the factors that shape unique constitutional and institutional designs. Geography and basic demographics play a role, but also social stratification, or difference among individuals in terms of wealth or prestige. Social stratification is often reflected, and subsequently reinforced, in political stratification (differentiation in political power, access, and representation). Lastly, global stratification suggests an imbalance of power in the global world, in which core countries are able to control or influence economic and political processes in semi-periphery and periphery countries.

In the next chapter, we will consider a very different set of sub-disciplines—American politics and public policy and administration.

Media Attributions

- IV DV © Jay Steinmetz is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- 1024px-Kurdistan_wkp_reg_en © Ferhates is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Geopolitics_South_Russia © Spiridon Ion Cepleanu is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- Nigeria-karte-politisch_english is licensed under a CC BY-SA (Attribution ShareAlike) license

- World_trade_map © Lou Coban is licensed under a Public Domain license

- Sawe, Benjamin Elisha. "What is the Most Spoken Language in the World?" WorldAtlas, Jun. 7, 2019, worldatlas.com/articles/most-popular-languages-in-the-world.html (accessed on August 7, 2019).. ↵

Politics, Power, and Purpose: An Orientation to Political Science Copyright © 2019 by Jay Steinmetz is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

case selection and the comparative method: introducing the case selector

- Published: 14 August 2017

- Volume 17 , pages 422–436, ( 2018 )

Cite this article

- timothy prescott 1 &

- brian r. urlacher 1

665 Accesses

2 Citations

5 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

We introduce a web application, the Case Selector ( http://und.edu/faculty/brian.urlacher ), that facilitates comparative case study research designs by creating an exhaustive comparison of cases from a dataset on the dependent, independent, and control variables specified by the user. This application was created to aid in systematic and transparent case selection so that researchers can better address the charge that cases are ‘cherry picked.’ An examination of case selection in a prominent study of rebel behaviour in civil war is then used to illustrate different applications of the Case Selector.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this article

Price includes VAT (Russian Federation)

Instant access to the full article PDF.

Rent this article via DeepDyve

Institutional subscriptions

Similar content being viewed by others

Case Study Research

Qualitative Comparative Analysis

Ahmed, A. and Sil, R. (2012) ‘When Multi-method Research Subverts Methodological Pluralism—or, Why We Still Need Single-Method Research’, Perspectives on Politics 10(4): 935–953.

Article Google Scholar

Asher, H. (2016) Polling and the Public: What every citizen should know , Washington, DC: CQ Press.

Google Scholar

Balcells, L. (2010) ‘Rivalry and Revenge: Violence Against Civilians in Conventional Civil Wars’, International Studies Quarterly 54(2): 291–313.

Brady, H. E. and Collier, D. (eds) (2004) Rethinking Social Inquiry: Diverse Tools, Shared Standards , Lanhan, MD: Rowman and Littlefield.

Dafoe, A. and Kelsey, N. (2014) ‘Observing the capitalist peace: Examining market-mediated signaling and other mechanisms’, Journal of Peace Research 51(5): 619–633.

DeRouen Jr, K., Ferguson, M. J., Norton, S., Park, Y. H., Lea, J., and Streat-Bartlett, A. (2010) ‘Civil War Peace Agreement Implementation and State Capacity’, Journal of Peace Research 47(3): 333–346.

Dogan, M. (2009) ‘Strategies in Comparative Sociology’, New Frontiers in Comparative Sociology , Leiden, Netherlands: Brill, pp. 13–44.

Durkheim, E. (1982) [1895] The Rules of Sociological Method , New York, NY: Free Press.

Book Google Scholar

Eck, K and Hultman, L. (2007) ‘One-Sided Violence Against Civilians in War: Insights from New Fatality Data’, Journal of Peace Research 44(2): 233–246.

Fearon, J. D. and Laitin, D. D. (2008) ‘Integrating Qualitative and Quantitative Methods’, The Oxford Handbook of Political Methodology , New York, NY: Oxford University Press. pp. 756–776.

Freedman, D. A. (2008) ‘Do the Ns Justify the Means?’, Qualitative & Multi - Method Research 6(2): 4–6.

George, A. L. and Bennett, A. (2004) Case Studies and Theory Development in the Social Sciences , Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

Gerring, J. and Cojocaru, L. (2016) ‘Selecting Cases for Intensive Analysis: A Diversity of Goals and Methods’, Sociological Methods & Research 45(3): 392–423.

Gerring, J. (2001) Social Science Methodology: A Criterial Framework, Cambridge, UK: University of Cambridge Press.

Gerring, J. (2004) ‘What Is a Case Study and What Is It Good for?’, American Political Science Review 98(2): 341–354.

Gerring, J. (2007) Case Study Research: Principles and Practices , Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Glynn, A. N., and Ichino, N. (2016) ‘Increasing Inferential Leverage in the Comparative Method Placebo Tests in Small-n Research’, Sociological Methods & Research 45(3): 598–629.

Iacus, S. M., King, G., Porro, G., and Katz, J. N. (2012) ‘Causal Inference Without Balance Checking: Coarsened Exact Matching’, Political Analysis 20(1): 1–24.

Kohli, A., Evans, P., Katzenstein, P. J., Przeworski, A., Rudolph, S. H., Scott, J. C., and Skocpol, T. (1995) ‘The Role of Theory in Comparative Politics: A Symposium’, World Politics 48(1), 1–49.

Kalyvas, S. N. 2006. The Logic of Violence in Civil War , Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

King, G., Keohane, R. O., and Verba, S. (1994) Designing Social Inquiry: Scientific Inference in Qualitative Research , Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Kuperman, A. J. (2004) ‘Is Partition Really the Only Hope? Reconciling Contradictory Findings About Ethnic Civil Wars’, Security Studies 13(4): 314–349.

Lijphart, A. (1971) ‘Comparative Politics and Comparative Method, American Political Science Review 65(3): 682–698.

Maoz, Z. (2002) ‘Case Study Methodology in International Studies: From Storytelling to Hypothesis Testing’, Evaluating Methodology in International Studies , Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press, pp. 161–186.

Mahoney, J. (2010) ‘After KKV: The New Methodology of Qualitative Research’, World Politics , 62(1): 120–147.

Mill, J. S. (1872) A System of Logic . London, England: Longmans, Green, Reader, and Dyer.

Nielsen, Richard A. 2016. Case Selection via Matching. Sociological Methods & Research 45(3): 569 - 597.

Peters, B. G. (1998) Comparative politics: Theory and methods , Washington Square, NY: New York University Press.

Przeworski, A. and Teune, H. (1970) The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry , New York, NY: Wiley-Interscience.

Ragin, C. C. (2014) The Comparative Method: Moving Beyond Qualitative and Quantitative Strategies . Berkley, CA: University of California Press.

Ragin, C. C., Berg-Schlosser, D., and de Meur, G. (1996) ‘Political Methodology: Qualitative Methods’, A New Handbook of Political Science , New York, NY: Oxford University Press, pp. 749–769.

Sambanis, N. (2004a) ‘What is Civil War? Conceptual and Empirical Complexities of an Operational Definition’, Journal of Conflict Resolution 48(6): 814–858.

Sambanis, N. (2004b) ‘Using Case Studies to Expand Economic Models of Civil War’, Perspectives on Politics 2(2): 259–279.

Seawright, J. and Gerring, J. (2008) ‘Case Selection Techniques in Case Study Research: A Menu of Qualitative and Quantitative Options’, Political Research Quarterly 61(2): 294–308.

Schrodt, P. A. (2014) ‘Seven Deadly Sins of Contemporary Quantitative Political Analysis’, Journal of Peace Research 51(2): 287–300.

Slater, D. and Ziblatt, D. (2013) ‘The Enduring Indispensability of the Controlled Comparison’, Comparative Political Studies 46(10): 1301–1327.

Snyder, R. (2001) ‘Scaling Down: The Subnational Comparative Method’, Studies in Comparative International Development 36(1): 93–110.

Tarrow, S. (2010) ‘The Strategy of Paired Comparison: Toward a Theory of Practice’, Comparative Political Studies 43(2): 230–259.

Weinstein, J. M. (2007) Inside Rebellion: The Politics of Insurgent Violence , Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Wood, R. M. (2010) ‘Rebel Capability and Strategic Violence Against Civilians’, Journal of Peace Research 47(5): 601–614.

Yang, Z., Matsumura, Y. Kuwata, S., Kusuoka, H., and Takeda, H. (2003) ‘Similar Case Retrieval from the Database of Laboratory Test Results’, Journal of Medical Systems 27(3): 271–281.

Yin, R. K. (2003) Case Study Research: Design and Method , Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, Inc.

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and feedback over the course of the review processes. This project has been significantly improved by their suggestions. The authors have also agreed to provide access to the Case Selector through their faculty webpages at their affiliated institutions.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Political Science Department, University of North Dakota, 293 Centennial Drive, Grand Forks, ND, USA

timothy prescott & brian r. urlacher

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to brian r. urlacher .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

prescott, t., urlacher, b.r. case selection and the comparative method: introducing the case selector. Eur Polit Sci 17 , 422–436 (2018). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0128-5

Download citation

Published : 14 August 2017

Issue Date : September 2018

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/s41304-017-0128-5

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- comparative method

- case selection

- qualitative methods

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

There are a number of different ways to categorize case studies. One of the most recent ways is through John Gerring. He wrote two editions on case study research (2017) where he posits that the central question posed by the researcher will dictate the aim of the case study. ... In a Most Different System Design, the cases selected are ...

In comparative political research we distinguish between the 'Most Similar Systems Design' (MSSD) and the 'Most Different Systems Design' (MDSD). In the present work, I argue that the applicability of the two research strategies is determined by the features of the research task. Three essential distinctions are important when assessing ...

"Most Different Systems" and "Most Similar Systems": ... On the Applicability of the Most Similar Systems Design and the Most D... Go to citation Crossref Google Scholar. ... A Case Study. Show details Hide details. STEVEN E. SCHIER. American Politics Quarterly. Apr 1982.

The corresponding research logic of Most Similar Systems Design and Most Different Systems Design is introduced and explained herein. ... For case studies to contribute to cumulative development of knowledge and theory they must all explore the same phenomenon, pursue the same research goal, adopt equivalent research strategies, ask the same ...

Most Similar/Most Different Systems Approach. Single case studies are valuable as they provide an opportunity for in-depth research on a topic that requires it. However, in comparative politics, our approach is to compare. ... In a Most Different System Design, the cases selected are different from each other, but result in the same outcome ...

This chapter discusses the role of the most-similar systems design and most-different systems design in comparative public policy analysis. The methods are based on John Stuart Mill's 'eliminative methods of induction' and regularly mentioned in educational books in social research methodology in general and in comparative politics in particular. However, their role has been less ...