Dolly Everett's suicide leads teen to create 'powerful and relevant' cyberbullying ad

A striking new ad about cyberbullying, directed by a 15-year-old girl, has been lauded as "brave", "disturbing" and "relevant" less than two years after the suicide of Amy 'Dolly' Everett shocked the nation .

Key points:

- Film shows a girl receiving texts like "kill urself" as oblivious parents sit by

- Dolly's parents hope it shows others how cyberbullying can creep into the home

- Film's teen director says every high schooler on social media has experience with it

Dolly was just 14 when she died early last year after being tormented by cyberbullies.

Now, stirred by her death, teenager Charlotte McLaverty has created a powerful short film that depicts how modern bullying is more than just sticks and stones in the playground.

It follows a teen girl in school uniform holding her phone, which pings with the notification sound every time another girl throws a rock at her.

The settings are all at home, including in the bedroom, bathroom and around the kitchen table as oblivious parents sit by.

As the film goes on more kids are given stones to throw and texts rapidly appear on the victim's phone, with messages like "why don't u just go kill urself".

"I was hoping to relate to how it feels to be cyberbullied for most teens," Charlotte told the ABC.

"The rocks being thrown was like the visual representation of what it feels like.

"The fact that the bully is there with her and none of the parents or children realise what's happening."

One in five young people report being cyberbullied in any one year, according to research by the advocacy organisation Dolly's Dream, which was established by Dolly's parents last year.

The organisation has this week launched a new internet hub to help parents better understand and deal with online safety, including bullying.

Australia's eSafety Commissioner, Julie Inman Grant, also operates a cyberbullying reporting scheme for people aged 18 or under, and can issue an order to have material taken down.

Since July 2015 it has handled more than 1,300 complaints about cyberbullying of young Australians and says it has had a 100 per cent compliance rate from social media sites.

Dolly's mum Kate Everett said she hoped the ad would inspire teens to speak up.

"Dolly left us with a message that was 'speak, even if your voice shakes'," she said.

"I hope it reveals to parents how cyberbullying can happen anywhere, even at the dining table or watching TV with the family."

'Not like a punch in the face'

Charlotte's ad is being billed as a project that is "by teens, for teens" and she said part of the problem was cyberbullying was sometimes missed, even by the victims.

"It's not like a punch in the face. It's constant, relentless comments," she said.

"And it's harder to know — a punch in the face is like, 'Oh I'm being bullied'. You come home with a black eye.

"These type of comments, it's such a grey area, it's hard to know if you're even being cyberbullied, but you're hurt."

"It's so difficult, that's why we need to start talking."

Charlotte said the technology hadn't been around long enough to know if the issue had become better or worse, but she was adamant it was pervasive.

"Everyone who's had social media for over a year has either witnessed, experienced or been a victim or a bully," she said.

"Everyone who has social media can have some sort of story about it."

The ad was publicly released this week but has already been welcomed by viewers who described it as "so relevant" and "fantastic", with some saying it should be shown in every high school.

"Powerful and disturbing ... it's sad that this happens and brave that this has been made," one person wrote in response.

"The young girl who created this represents the situation so accurately," wrote another.

The film ends with the victim catching one of the thrown rocks and staring down her bully.

"Just to give a little bit of hope at the end of the film," Charlotte said.

- X (formerly Twitter)

Related Stories

'dolly saw the good in everybody she met': mourners gather to remember nt teen.

Is there a better way to talk about suicide? Quentin Bryce thinks so

- Community and Society

Bullying: A Case Study Revisited

Cruelty and its impact, years later.

Posted April 9, 2015

- How to Handle Bullying

- Find a therapist to support kids or teens

Several years ago, a teacher shared a scenario that exemplified how crafty and insidious bullying can be. I blogged about it at the time and reprinted the story here—as well as a followed up with the young victim:

From the outside, the abuse looked innocuous enough—kids around a table in the cafeteria, singing fragments of popular songs and laughing . Nothing to catch the attention of monitors—until another student bade a young teacher to listen carefully to the lyrics. Muse’s popular song was only tweaked, becoming "Far away / you can’t be far enough away / far away from the people who don’t care if you live or die." Instead of Lady Gaga’s lyrics, the kids chanted “you are so ugly / you are a disease. The boys don’t even want what you’re givin’ for free. No one wants your Love / Ew, yuck, ew / you’re such a joke.” Instead of Beyonce’s, “If you like it then you should’ve put a ring on it,” they sang “you’re a f*#% up and loser put a bag on it.” The repertoire was extensive, and new songs were added every week.

By and large, the students were careful to write lyrics that would pass censorship and not attract attention to themselves for profanity. They delighted in their own cleverness, and in their ability to get many uninvolved bystanders to sing a chorus as they waited in the food line. In other words, the humiliation of one girl became a popular bonding experience, and ad-libbing new lyrics was a way to get positive peer attention.

As they saw it, it was all just a joke. Ha Ha. Can’t she take a little joke?

Recently, I tracked down the victim (she is at a top-tier college) and she agreed to reflect on her experiences. I first asked whether she remembered the correct lyrics to those songs, all these years later. My mistake. I assumed the alternate lyrics were seared into her brain. Instead, she told me she had forgotten the revised songs, and would not have recalled the lyrics had I not transcribed them, years ago. When I asked whether she had ever gotten an apology , or if one would change anything now, she didn’t think there was any need.

Gratifying as it was to see her doing well, these were not the responses I anticipated. But as parents and educators think about bullying, it is important to keep in mind that not all incidents—not even all ongoing cruelties that clearly affect a young adult—will scar her for life. And that we may, at times, do a disservice to young people by rushing in to fix what we perceive as threatening, undermining their own abilities to handle it.

Our inability to gauge resilience is complicated by the fact that much cruelty lies in intersubjective nuances that are equally impossible to grasp, let alone gauge. However, much of the capacity for reparation lies in those nuances as well.

To my mind, singing cruelly revised songs (and encouraging others to sing along) was ongoing abuse, one that called for an intervention. However, "loud singing on the bus" was the only concrete issue that was ever addressed. The victim herself refused any involvement of school authorities, and—as she appears to be thriving—it seems this was the "right call" on her part. (Was it that she could not quite define herself as a victim? That she was handling her "victimization" in ways that adults could not see? That the teacher saw to it that ringleaders got in trouble for unrelated offenses? That—appearances to the contrary—she is burdened by insecurity and secret shame ?)

Interviewing this young woman prompted me to track down, and reconsider, something Clive Seale wrote almost two decades ago:

“in the ebb and flow of everyday interactions, as has been conveyed so effectively in the work of [Erving] Goffman, there exist numerous opportunities for small psychic losses, exclusions and humiliations, alternating with moments of repair and optimism . [Thomas] Scheff (1990) has sought to understand this quality of everyday interaction as consisting of cycles of shame and pride as the social bond is alternately damaged and repaired. The experience of loss and repair is, then, a daily event. In this sense “ bereavement ” (and recovery from it) describes the continual daily acknowledgement of the problem of human embodiment.” (1998)

To adults looking on, cruel song lyrics certainly seem a large "ebb" in the flow of this young student’s life—one requiring intervention. Her story, however, reminds us that as we forge ahead, looking for ways to protect our children against bullying, we must simultaneously enable them to negotiate the "ebbs" in life. A first step in this may simply involve helping them identify the "flow." This is not to lessen active response to bullying, or to sweep it under the rug, but to teach our children to challenge the negative self-narratives that form around bullying experiences. And—perhaps more importantly—to teach them that as bystanders, they contribute to the narratives of others (either implicitly or explicitly). At the risk of sounding Pollyannaish, the identification of counter-factual evidence may go far in challenging this negativity. It turns out, this is precisely what this young women was able to—though a group of friends outside the school environment, who not only raised awareness of, but contributed to, her flow.

Laura Martocci, Ph.D . is a Social Psychologist known for her work on bullying and shame. A former faculty member and dean at Wagner College, her current work centers around identity (re)construction and the transformative potential in change.

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Teletherapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Coronavirus Disease 2019

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

ITS PSYCHOLOGY

Learn All About Psychology

- Neuro Psychology

- Educational Psychology

- Research Psychology

- Mental Disorder

- Personality Disorder

- Relationship

- Social Skills

19 Cases of Bullying among Real and Overwhelming Youth

Table of Contents

Last Updated on April 13, 2023 by Mike Robinson

We present 19 cases of real bullying and cyberbullying characterized by their fatal outcomes and the lack of training of education professionals. The cases and stories of bullying in schools and outside them with cyberbullying have multiplied in recent years.

Bullying can cause severe mental distress. The cases of adolescents and minors who take their own lives due to the different types of bullying should be alarming to educational professionals. Schools must implement immediate and decisive actions to curtail this unacceptable behavior trend.

1-Miriam, eight years old

Miriam is an eight-year-old girl who goes to elementary school. She loves animals, so she always has pictures of them in her books. She even has a backpack shaped like a puppy.

Her companions laugh and make fun of her, comparing her with the animals on the stickers on her backpack because she is overweight. Also, since she is “fat,” they take her money and snacks at recess.

Although she has told the teachers repeatedly, they have not done much to change the situation. To try to improve the situation, Miriam stopped eating and is in the hospital for anorexia.

2-Tania: Fourteen years old.

Tania, a 14-year-old teenager, has tried to commit suicide due to her high school classmates’ continuous threats, robberies, and aggressions. The situation has not changed despite filing 20 complaints against 19 of her classmates.

In January 2014, she was admitted to the hospital for 15 days due to an overdose of Valium pills. Despite her attempted suicide, the threats are still ongoing.

3-Diego: Eleven years old

It is a recent case of school bullying in Spain; Diego, an eleven-year-old boy, was a victim of this practice in a school in Madrid.

His mother remembers that her son told her he did not want to go to school, so his mood was always very sad; once, he lost his voice because of a blow he had suffered at school from his classmates.

The day he committed suicide, his mother went to pick him up at school, and he ran frantically to the car to get out safely. Later that evening, he killed himself.

4-Jokin Z: Fourteen years old

It was one of the first cases of bullying that came to light in Spain. After being bullied for months, he decided to commit suicide. The parents felt helpless. They tried for two years to prevent this tragedy and remove the suffering of their teenage son.

As a result of his suicide, eight students had charges brought against them. The parents were also arrested. However, only one individual was convicted.

5-Jairo: Sixteen years old

Jairo is a 16-year-old boy from a town in Seville who faced severe bullying because of his physical disability. He has a prosthetic leg due to a wrong operation. His classmates continually make fun of him and his disability.

Not only did they trip him, but they also tried to take it off in the gymnastics class. On the other hand, in the social networks, there were photos of him manipulated with computer programs with bad words that made Jairo not want to go to school.

Due to the suffering caused by this type of behavior, Jairo asked to change schools and is currently at another institute.

6-Yaiza: Seven years old

At seven years old, Yaiza suffered bullying from her classmates. They insulted her continuously, to the point that Yaiza had difficulty convincing herself that what her classmates told her was false. Not only did they insult her, but they also stole her breakfast and even once threw a table at her.

She was fortunate to have a teacher who was involved in the issue of bullying and helped make changes at the school. The teacher brought attention to bullying to better understand why these practices occur in schools.

7-Alan: Seventeen years old

This seventeen-year-old teenager was bullied by his classmates because he was a transsexual. He took his life on December 30, 2015, after taking pills mixed with alcohol.

It was not the first time he tried since he had been receiving therapy numerous times because he had suffered for years. As in other cases, Alan was no longer in school, but that was not enough.

8-Ryan: Fourteen years old

After years of psychological aggression, in 2003, Ryan, then fourteen years old, decided to commit suicide. He did so because he was supposedly gay. It all started because a friend of his published online that he was homosexual.

Because of this, he did not stop receiving jokes, ridicule, and humiliation from his classmates. This case helped to approve the Harassment Prevention Act in Vermont of the US States months after his death.

9-Arancha: Sixteen years old

This 16-year-old girl decided to throw herself from the sixth floor. The reason was the bullying she suffered from classmates in Madrid.

Arancha suffered from motor and intellectual disabilities, which was more than enough for her class to bully her. Although her parents reported this fact to the police, it was not enough to prevent the fatal outcome.

Minutes before launching herself from the building, she said goodbye to the people closest to her by sending them a message through WhatsApp, saying, “I was tired of living.”

10-Lolita: Fifteen years old

Lolita is currently under medical treatment due to the depression she suffers, which has paralyzed her face. This young woman from Maip, Chile, was bullied by four classmates at her school.

Her classmates mocked and humiliated her in class, which seriously affected her. According to the mother, the school knew about her daughter’s mistreatment and did nothing to prevent it.

11-Rebecca: Fifteen years

The case of Rebecca from the state of Florida is an example of cyberbullying. She decided to take her own life in 2013 due to the continuous threats and humiliations suffered by colleagues on social networks.

She and her mother had informed the teachers at school of this situation. Unfortunately, they did not work to stop the attacks on her. She posted on her profile days before her death, “I’m dead. “I cannot stand it anymore.”

12-Phoebe Prince: Fifteen years old

This 15-year-old Irish immigrant girl was harassed by nine teenagers who had criminal charges brought up in 2010. She was bullied physically and psychologically, and there was cyberbullying through cell phones and the internet.

Phoebe was humiliated and assaulted for three months in high school until she ended up hanging herself. The people who harassed her continued to do so even after her death.

13-Rehtaeh: Fifteen years old

This girl from Halifax, Nova Scotia, decided to hang herself in her bathroom after suffering cyber bullying. Her schoolmates and strangers took part in the bullying. Rehtaeh got drunk at a party, where, apart from raping her, they photographed her while it happened.

This photo began circulating everywhere, so even kids she did not know asked her to sleep with them on social networks. Her classmates also insulted her and made fun of her.

14-Oscar: Thirteen years old

This minor, who is 13 years old and in the first year of secondary school, decided to ingest liquid drain cleaner for pipes for the sole purpose of not going to school. Oscar was harassed not only by his classmates but also by one of his teachers.

Oscar could not contain the urge to go to the bathroom due to a urinary problem. His teacher never let him go, so he once urinated on himself. From that moment on, he had to deal with the treatment he received from his teacher and his classmates, who made fun of him and insulted him repeatedly.

15-Monica: Sixteen years old

Mónica lived in Ciudad Real (Spain) and was 16 years old when she decided to commit suicide because of the treatment she received at school from her classmates. They would insult her on the bus, threaten her, and publish photos and nasty comments on social networks.

She decided to commit suicide to end all the hell that her classmates made her go through. Even though her father, one day before he took his own life, complained to the head of studies about what was happening to his daughter.

16-María: Eleven years old

This girl from Madrid (Spain) suffered harassment from her classmates at a religious school. Her classmates not only made fun of her but even physically mistreated her.

Teachers disputed these claims and did not defend her or take measures to stop them from happening. Because of this, she tried to overdose on pills without success.

17-Amanda: Fifteen years old

Amanda, a Canadian-born minor, committed suicide after posting a video on social media reporting that she was suffering bullying.

It all started when he sent a topless photo of herself to a stranger on the webcam; from that moment, insults and harassment began on the internet.

This bullying lasted three years. Amanda even changed schools to rebuild her life, but it did not help. The abuse caused anxiety and acute depression that led her to consume drugs.

18-Zaira: Fifteen years old

Here is another victim of bullying from classmates. In the case of Zaira, it all started when they recorded her with a cell phone while she was in the bathroom. These girls spread the video among all the school’s classmates and others outside her school.

Because of these recordings, Zaira had to take the continuous teasing of her classmates and even physical abuse. Thanks to a lower-class classmate, she faced bullying, and this story had a happy ending.

19-Marco: Eleven years

This child had spent five years enduring the harassment he suffered from his classmates. They made fun of him because he was supposedly overweight, although, in reality, he was not.

They humiliated him on many occasions, and once, they even took off his clothes in gym class. A teacher knew what was happening to him and did not take action. Marco is currently in another school after telling him everything that happened to his parents.

Conclusions About Bullying

These 19 cases are only 19 of many in our schools. These examples show the flaws that exist in education systems worldwide. The education system professionals are not doing enough to address these abuses.

Despite all we know about bullying, there still needs to be more information about its prevention and action. The schools are not prepared to face this type of situation, leading them to ignore this behavior in their students and leave the families alone with this problem.

Also Read: 11 Human Body Games for Children

To reduce the number of suicides due to school bullying in children, we must educate everyone involved. By providing adequate training, people will know what guidelines to follow in these situations to prevent adolescent suicide.

Related Post

10 activities for children with down syndrome.

The 6 Most Common Bone Marrow Diseases

What is Solomon Syndrome? 7 Guidelines to Combat It

The Role of Dopamine in Love

Child Aggression: Symptoms, Causes and Treatments

What is Vicarious Learning?

Long Words Phobia (Hipopotomonstrosesquipedaliofobia)

21 Activities for Children with ADHD

Cognitive Stimulation: 10 Exercises for Adults and Children

Aggressive Communication: Features and Examples

The 10 Most Common Neurological Symptoms

Mental Hygiene: What it is and 10 tips to have it

The 4 Major Stress Hormones

Mythomania Symptoms, Causes and Treatment

- The Ultimate Guide to Overcoming Driving OCD

- Why Happiness Is a Choice: How to Live a Fulfilling Life

- A Guide on How to Rebuild Your Life After Trauma

- Understanding Trauma Bonding and Its Effects

Its Psychology

Quick Links

- Privacy Policy

- Terms and Conditions

- About Its Psychology

Recent Posts

- The Battle of Resistance vs Resilience: How to Build Mental Toughness

Need help dealing with violent or distressing online content? Learn more

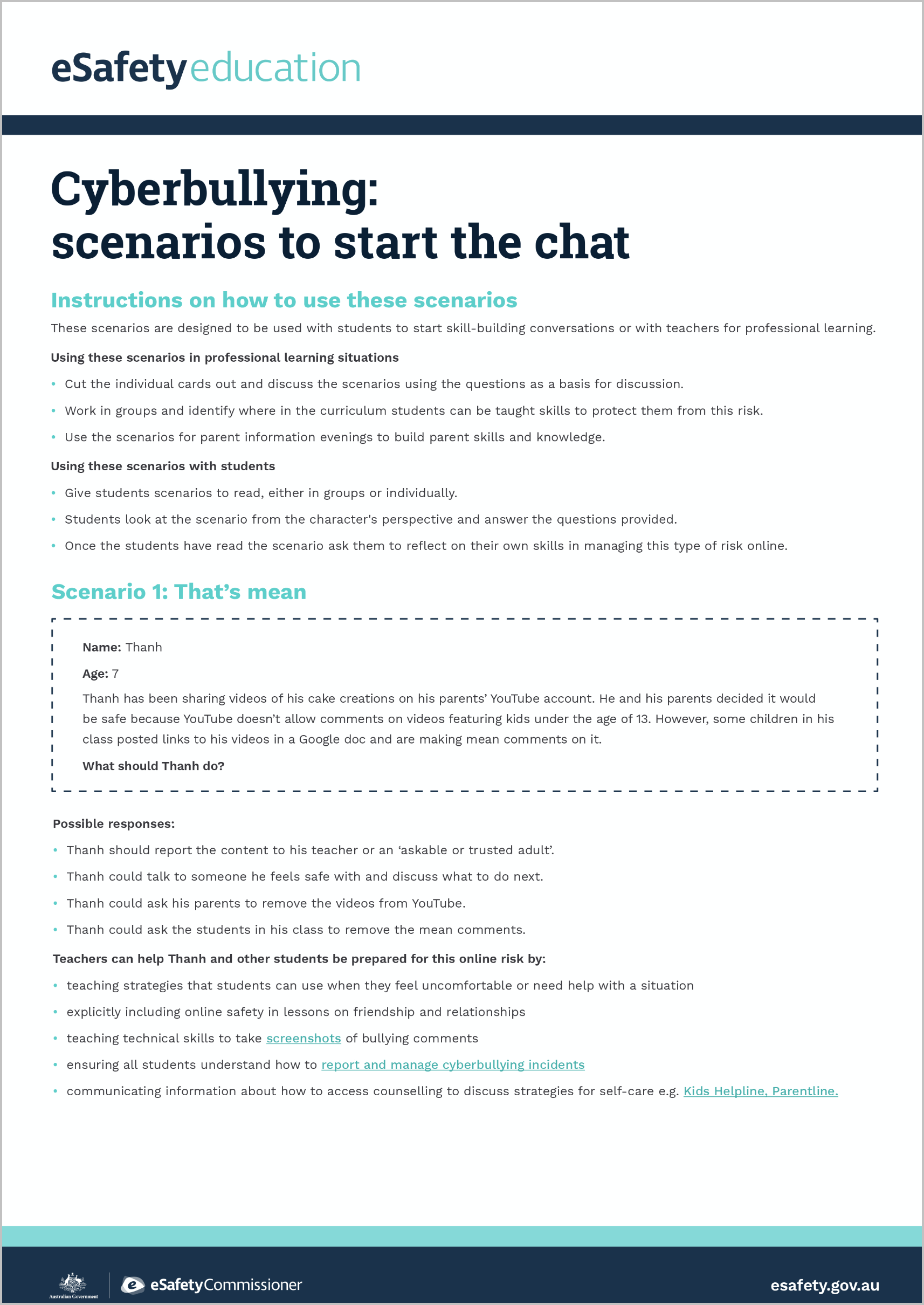

Cyberbullying: scenarios

Instructions on how to use these scenarios .

These scenarios are designed to be used with students to start skill-building conversations or with teachers for professional learning.

Using these scenarios in professional learning situations

- Cut the individual cards out and discuss the scenarios using the questions as a basis for discussion.

- Work in groups and identify where in the curriculum students can be taught skills to protect them from this risk.

- Use the scenarios for parent information evenings to build parent skills and knowledge.

Using these scenarios with students

- Give students scenarios to read, either in groups or individually.

- Students look at the scenario from the character's perspective and answer the questions provided.

- Once the students have read the scenario ask them to reflect on their own skills in managing this type of risk online.

Scenario 1: That’s mean

Name: thanh.

Thanh has been sharing videos of his cake creations on his parents’ YouTube account. He and his parents decided it would be safe because YouTube doesn’t allow comments on videos featuring kids under the age of 13. However, some children in his class posted links to his videos in a Google doc and are making mean comments on it.

What should Thanh do?

Possible responses:

- Thanh should report the content to his teacher or an ‘askable or trusted adult’.

- Thanh could talk to someone he feels safe with and discuss what to do next.

- Thanh could ask his parents to remove the videos from YouTube.

- Thanh could ask the students in his class to remove the mean comments.

Teachers can help Thanh and other students be prepared for this online risk by:

- teaching strategies that students can use when they feel uncomfortable or need help with a situation

- explicitly including online safety in lessons on friendship and relationships

- teaching technical skills to take screenshots of bullying comments

- ensuring all students understand how to report and manage cyberbullying incidents

- communicating information about how to access counselling to discuss strategies for self-care e.g. Kids Helpline, Parentline.

Scenario 2: WhatsApp

A group of students in Kobe’s class have been invited to join the same WhatsApp group. At first, it was to chat about a soccer game, but the students enjoyed using WhatsApp. Soon it seemed like everyone was in the chat. Kobe wasn't asked, and a friend showed him a message posted in the group which said 'Kobe is a cry baby. No one let him in the chat.'

How could Kobe’s friends help him?

Suggested responses:

- His friends could send Kobe an encouraging direct message.

- His friends could encourage the group to include Kobe for example they could say: ‘Kobe comes up with great ideas for projects. Let’s include him.’

Teachers can help Kobe and other students be prepared for this online risk by:

- discussing social media age restrictions and the benefits and risks of using social media

- explicitly including online safety in lessons on relationships and wellbeing

- working with students in the class to include other students online and offline

- discussing how students can access support if they don’t feel comfortable talking to their teacher e.g. Kids Helpline , a school counsellor.

Scenario 3: Image-based abuse or cyberbullying

Amy broke up with Joe (16 years old) a few months ago. Joe says he is really upset and can't get over her. Even though Amy has asked him to give her some space, he sends her direct messages on social all the time. Amy is shocked when Joe sends her some nude images taken of her when they were in a relationship. He doesn't include a message with the photos. (Source: YeS project)

How can Amy and Joe get support?

- Amy could use Youth Law Australia to get information about sexting laws in their state.

- Amy could talk to a trusted adult or teacher about the situation and problem solve how to get support.

- Amy could report any issues to the social media company first, if she feels she needs help - she can use The eSafety guide to find out how. See eSafety's reporting pages for advice, support and FAQs.

- Amy might ask a teacher/counsellor to help her report the issue. eSafety’s guide to explicit images in schools provides specific guidance for schools on how to do this safely.

- Amy could contact the eSafety image-based abuse team (for complaints about sharing nude images without consent ) or the cyberbullying team (for complaints about posts that seriously harass, threaten, humiliate or intimidate). The teams work together closely, so if Amy is unsure about the category they will help her work it out. They can assist with liaising with social media companies, as well as providing advice and referrals to support services.

- Joe could explore eSafety young people to get strategies to help him take action to turn the situation around.

Teachers can help Amy, Joe and other students be prepared for this online risk by:

- including online examples in lessons on respectful relationships, consent and wellbeing

- ensuring all students understand social media standards and the consequence for misuse even in private communications

- ensuring all students understand how to report an online safety issue to the social media company and when to escalate to the eSafety Commissioner. See eSafety's reporting pages for advice, support and FAQs.

- helping all students know where to go for help if they have been called a bully or shared an intimate image without someone's consent

- promoting appropriate counselling and support services to all students.

Cyberbullying scenarios

eSafety acknowledges all First Nations people for their continuing care of everything Country encompasses — land, waters and community. We pay our respects to First Nations people, and to Elders past, present and future.

First Nations people should be aware that this website may contain images and voices of people who have died.

Find information and resources for First Nations people.

Read our Reconciliation Action Plan .

Get the latest info to your inbox

What's on

Find the latest webinars, events and campaigns

Ask a general question about our work

Keep up to date across all our platforms

- Disclaimer and copyright

- Accessibility

- Privacy policy

- Freedom of information

Watch CBS News

A 15-year-old boy died by suicide after relentless cyberbullying, and his parents say the Latin School could have done more to stop it

By Megan Hickey

April 25, 2022 / 10:44 PM CDT / CBS Chicago

CHICAGO (CBS) -- A 15-year-old boy named Nate Bronstein was enrolled at one of the most prestigious private schools in Chicago and had a promising future — that is, until his parents say he became a victim of relentless cyberbullying by his classmates.

Nate took his own life.

And in an exclusive interview with CBS 2 Investigator Megan Hickey, his parents allege that the Latin School of Chicago could have done more to stop it.

Rose and Robert Bronstein never fathomed that they'd be speaking about their son, Nate in the past tense.

"I still can't process it," said Rose Bronstein.

"He definitely wanted to go to a college that had big time sports," said Robert Bronstein. "He loved to make people laugh, and laugh himself."

And of the school, Rose added, "It's a toxic culture – so toxic that we lost our son from it."

The Bronsteins' 10th-grader was a super-sharp, funny kid; A pillar in their family of five. He was a new transfer last fall to the Latin School of Chicago, at 59 W. North Blvd. in the Gold Coast.

But he was bullied by his classmates to the point that he didn't want to live to see his future.

"It had been kept from us, so that's why we were completely, completely taken off guard when this happened," said Robert Bronstein.

The Bronsteins had concerns about their son adjusting to a new school — and according to a 68-page lawsuit just filed in the Circuit Court of Cook County, they raised those concerns repeatedly with administrators.

Bronstein Complaint (Filed 4.25.22) by Adam Harrington on Scribd

But according to the filing, they had no idea about the extent of the cyberbullying that tormented Nate.

But the Bronsteins say Latin did.

"Our son would still be alive today if Latin would have done their job and reported to us what had gone on within the school," said Rose Bronstein.

The Bronsteins say they were never told that on Dec. 13, 2021, Nate asked for a meeting with his dean of students to report that several students were bullying him via a text message thread provided to CBS 2, and on Snapchat.

One of those Snapchats, according to the lawsuit, encouraged Nate to kill himself. Another used a phrase that's understood to be an indirect death threat.

The dean listened, but took no disciplinary action, according to the filing.

And exactly one month later, Nate's father found him hanging from a shower in the bathroom in their home. A noose was tied around his neck.

Again, he was just 15.

"We would have known, and we would have protected him, and he'd still be here today," said Rose Bronstein.

It wasn't until after Nate died that the family was made aware of the texts, the Snapchats, the taunting — from another parent at Latin. And that's a problem — a legal one in the State of Illinois.

Illinois General Assembly Public Act 098-0669 requires that every school in the state, including private schools, have an anti-bullying policy.

That policy must include information about how bullying should be reported and how it is to be investigated, and also that bullying incidents must be reported to the parents of those involved.

"When there's an alleged incident of bullying, they are supposed to notify the parents of both parties involved," said Vitto Mendez, one of the leading experts in the country on state anti-bullying laws and their effectiveness.

Vitto Mendez confirmed that school administrators in the state of Illinois are legally obligated to report incidents of bullying to the family members of those involved.

Anna DiPronio Mendez is the executive director of the National Association of People Against Bullying, and she can speak to why notification is so important. Her son Daniel's school knew about his bullying, but she was never notified until after he took his own life in 2009.

He was just 16.

"It's one of my biggest regrets that I've lived with to this day is why was I not contacted? Why was I not told?" she said.

In the weeks and months following Nate's death, students, parents, and even a current employee of the school reached out to tell the family they were not alone in their concerns about an alleged cover-up culture at Latin.

You don't have to look much farther than Instagram to see public testimonials to that effect.

The Survivors of Latin Instagram account was a public account with close to 3,000 followers. According to the creator, the 121 pages' worth of stories involve "anti-Blackness, xenophobia, racism, classism, sexual assault, homophobia, transphobia, and misogyny."

The Instagram page was taken down as of Monday night, but a Survivors of Latin Facebook page remained in place .

"Look, our son was 15, and his perception of what he can and can't handle isn't necessarily accurate – but that's why the policies exist, and that's why, now, the law exists – to involve parents," said Robert Bronstein. "The school has to err on the side of a lot of transparency,"

To be clear, the family isn't suing Latin for the money. They've pledged to donate any money gained through legal proceedings to anti-bullying and anti-suicide charities. They say they're speaking out because remaining silent would disrespect their son's memory.

"You can't allow this to go on, because it's going to happen to another child," said Robert Bronstein.

The Bronsteins never got to watch their son grow up. But they hope they might give other parents the chance to step in.

"We need transparency into what they did and didn't do while he was a student there, and after the fact," said Robert Bronstein, "because if this can be allowed to just be swept under the rug, then it's going to happen again — and we're not going to be complicit in that."

We reached out to the Latin School with several questions upon the filing of the lawsuit. The school issued the following statement late Monday:

"Our school community deeply grieves the tragic and untimely passing of one its students. It is a loss that impacts our whole community. Our hearts go out to the family, and we wish them healing and peace. With respect to their lawsuit, however, the allegations of wrongdoing by the school officials are inaccurate and misplaced. The school's faculty and staff are compassionate people who put students' interests first, as they did in this instance. While we are not, at this time, going to comment on any specific allegation in this difficult matter, the school will vigorously defend itself, its faculty and its staff against these unfounded claims."

If you or someone you know is concerned about suicide, you can contact the 24/7, confidential National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 800-273-8255. You can also reach the Crisis Text Line by texting HOME to 741741, or go here to online chat. More helpful resources can be found here .

Megan Hickey is a member of the 2 Investigator team, focusing on topical investigative stories.

Featured Local Savings

More from cbs news.

20-year-old stabbed during attempted robbery on CTA platform in The Loop

Man robbed, sexually assaulted in River North

CPD seek 4 suspects in robbery at CTA Red Line Belmont stop

2 men found guilty in 2015 murder of 7-year-old Amari Brown

Open Access is an initiative that aims to make scientific research freely available to all. To date our community has made over 100 million downloads. It’s based on principles of collaboration, unobstructed discovery, and, most importantly, scientific progression. As PhD students, we found it difficult to access the research we needed, so we decided to create a new Open Access publisher that levels the playing field for scientists across the world. How? By making research easy to access, and puts the academic needs of the researchers before the business interests of publishers.

We are a community of more than 103,000 authors and editors from 3,291 institutions spanning 160 countries, including Nobel Prize winners and some of the world’s most-cited researchers. Publishing on IntechOpen allows authors to earn citations and find new collaborators, meaning more people see your work not only from your own field of study, but from other related fields too.

Brief introduction to this section that descibes Open Access especially from an IntechOpen perspective

Want to get in touch? Contact our London head office or media team here

Our team is growing all the time, so we’re always on the lookout for smart people who want to help us reshape the world of scientific publishing.

Home > Books > Adolescences

The Dark Side of YouTube: A Systematic Review of Literature

Submitted: 11 June 2021 Reviewed: 17 August 2021 Published: 06 September 2021

DOI: 10.5772/intechopen.99960

Cite this chapter

There are two ways to cite this chapter:

From the Edited Volume

Adolescences

Edited by Massimo Ingrassia and Loredana Benedetto

To purchase hard copies of this book, please contact the representative in India: CBS Publishers & Distributors Pvt. Ltd. www.cbspd.com | [email protected]

Chapter metrics overview

498 Chapter Downloads

Impact of this chapter

Total Chapter Downloads on intechopen.com

Total Chapter Views on intechopen.com

The prolific use of social media platforms, such as YouTube, has paved the way for the potential consumption of inappropriate content that targets the vulnerable, especially impressionable adolescents. The systematic review of literature has identified 24 papers that focused on the “dark side” of YouTube for adolescent users. The analysis showed that eight themes emerged: the glamorization of smoking, the promotion of alcohol use, videos that focused on body image/health, videos on bullying, self-harm/suicide, advertising, drugs and general vulnerabilities. The results revealed that videos that contain smoking and alcohol frequently feature sexualized imagery. Smoking videos also frequently feature violence. Smoking and alcohol are also often featured in music videos. The analysis also showed that researchers call for awareness, more strict advertising guidelines and promotion of health messages especially in terms of body image/health, self-harm/suicide and bullying. It is recommended that parents regulate the YouTube consumption of their younger adolescent children, as children do not always understand the risks associated with the content consumed, or might get desensitized against the risks associated with the content.

- Adolescents

- Vulnerabilities

Author Information

Marie hattingh *.

- Department of Informatics, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa

*Address all correspondence to: [email protected]

1. Introduction

In [ 1 ] it was reported that the main reasons adolescent use social media is for information sharing, alleviating boredom, escapism, to interact socially with peers, building social capital and to receive feedback on their appearances. Therefore, adolescents’ participation in social media platforms is an important aspect for “social participation” [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 ]. However, research has also shown that social media use can have an impact on the emotional state of the adolescent and the extent to which they can be influenced by peers [ 5 ]. Although, research on adolescents’ use of social media is widely reported, this research is focusing on one social media platform, YouTube. YouTube is a video sharing platform that allows content creators to share videos easily, and viewers can view most videos without subscription, registration or restriction.

According to [ 6 ] 80% of parents survey in the United States of America (USA) indicate that their children younger than 11 years of age watches videos on YouTube. According to [ 7 ] 85% of USA boys and 70% of USA girls between the ages 13 and 17 years of age use YouTube on a daily basis.

In [ 3 ] it was shown that adolescents develop a familiarity with the YouTubers (both as content creators and viewers) as they can identify with what they represent. This prolific use of YouTube by adolescents, and even pre-adolescent children, expose children to a variety of content: good and bad. Although it has been reported that adolescent do access YouTube content “for good” such as incidental learning [ 8 ], informal learning [ 9 ], dealing with anxiety [ 10 ], practicing safe sexual health [ 11 ] and to obtain information regarding medical procedures [ 12 ] to name a few, unfortunately a number of studies have reported on using YouTube “for bad”.

This chapter reports on a systematic review of literature on the negative aspects associated with YouTube, specifically concerning adolescents.

The chapter is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a description of the research methodology, Section 3 provides the data analysis and results. The results are discussed in Section 4 and the chapter is concluded in Section 5.

2. Research methodology

This study employed a systematic review of literature as the methodology. Two research platforms (ProQuest and Ebscohost) were used to access scholarly articles. The ProQuest platform included 12 databases (including ProQuest Central, Health & medical Collection, healthcare Administration database, Nursing and Allied Heath Database and Psychology Database) and the Ebscohost platform included multiple databases (including APA PscyArticles, APA PsycInfo, Family and Society Studies Worldwide, Health Source – consumer edition, Health source: Nursing/academic edition, humanities source, MEDLINE,) In both instances the search terms used were “YouTube” AND “(adolescents or teenagers)”. In both instances “YouTube” had to appear in the title of the paper and “adolescents/teenagers” needed to appear in the abstract of the paper. This search criteria ensured that the search was focused on the YouTube social media platform, with the user segment of adolescents or teenagers. The only filtered aspect was that only peer reviewed scholarly articles should be included.

Duplicate paper

Not written in English

Not focusing on “dark side” aspects

Table 1 illustrates that the final results obtained was a review of 24 papers. These 24 papers.

Search results.

Thematic Analysis [ 13 ] was employed to analyze the content of each of the 24 papers. Phase one is concerned with the researcher familiarizing herself with the data. This was accomplished by reviewing the articles obtained in the search and applying the exclusion criteria. Phases two to five almost occurred in parallel. Phase two was concerned with coding which involves the identification of the theme addressed by the paper. Eight main themes were identified and is illustrated in Table 2 . The third phase was concerned with sub-themes. For example, it emerged that YouTube videos featuring smoking also features violence and sexualized imagery. Phase four was concerned with reviewing the themes. This phase involved identifying links between sub-themes, for example it emerged that YouTube videos featuring alcohol also featured sexualized content. This is illustrated in Figure 1 . Phase five was self-evident, as the eight themes that emerged was very well-defined in terms of the context in which it was presented. Phase six is concerned with the write up of the data. This was done in two phases, first by providing a short description on each of the studies and then discussing the results in Section 6.

Themes identified from paper.

Themes and sub-themes.

3. Data analysis and result

Thematic analysis uncovered eight major themes. The themes that were uncovered are detailed in Table 2 .

Figure 1 illustrate how the themes (in yellow) are connected with the sub themes (in blue). The themes and sub themes have emerged from the literature where the authors discussed the theme in terms of the sub themes. For example, Kim et al. [ 14 ] conducted a content analysis of smoking fetish videos on YouTube and discovered videos containing smoking glamourizes the activity and it also contains a lot of sexualized imagery and violence. They call for guidelines to manage videos as young children have access to videos that should have parental guidance (PG) ratings.

Likewise, YouTube videos featuring alcohol, also contained sexualized imagery, were present in a number of music videos [ 18 ] where the use of alcohol was glamourized [ 20 ] and advertised [ 19 ].

Each of these themes will be discussed below.

3.1 Smoking

Four of the twenty four articles discussed the promotion and “eroticized” nature [ 14 ] of smoking. In [ 14 ] 200 videos were sampled from 2300 videos obtained by using the search words “smoking fetish” and “smoking fetishism”. Their analysis revealed (at 4 November 2007) 2220 smoking fetish videos. Using the same search term (“smoking fetch”) it was observed by looking at the playlists only, that there are over 7000 smoking fetish videos now 1 . Their analysis further showed that although some content was not available for under 18-year old’s, 85.1% of the content was available to everybody. Their study further found that almost 60% of the smoking fetish videos were sexually charged with scantily clad women. They also recommended stronger rating for the videos as it contained sexuality and violence.

In [ 16 ] it was tested whether health messages that informs adolescents of the risks of smoking had an impact on their perception of smoking. Their research showed that smoking exposure to adolescents on YouTube correlates with an apparent increased prevalence of smoking.

In [ 15 ] it was investigated how tobacco was presented in music videos. The results showed that, at that time (2015), the music videos contained 203 million representations of tobacco products where adolescents were exposed four times more than adults to tobacco products per head of the UK population. The research also showed that for both alcohol and tobacco girls were more.

In [ 17 ] it was explained that adolescents perceive cigars to be less harmful than cigarettes. As a consequence, smokers remove the tobacco binder through a process known as “freaking”. The results of their multi-study indicated that adolescents participate in freaking because they believe it ‘Easier to smoke’ (54%), ‘Beliefs in reduction of health risks’ (31%), ‘Changing the burn rate’ (15%) and ‘Taste enhancement’ (12%). Study 2, which concentrated on the comments of freaking videos, indicated that adolescents were unaware or not understanding the risks associated with smoking.

3.2 Alcohol

The alcohol theme is associated with the presence or consumption of alcohol in YouTube videos. Four papers reported on the extent to which alcohol was present in YouTube videos.

Further to what was reported above, [ 15 ] also investigated how the presence of alcohol was presented in music videos. The results showed that, at that time (2015), the music videos contained 1006 million representations of alcohol products where adolescents were exposed five times higher for alcohol than for tobacco and four times higher than adults for alcohol representations per head of the UK population. Exposed than boys.

In a further study of Cranwell et al. [ 18 ] analyzed “lyrics and visual imagery” of “49 UK Top 40 songs and music videos”. They found that the presence of alcohol in music videos were often accompanied with sexualized imagery or the objectification of women., that the use of alcohol was part of the image, lifestyle and sociability of the video actors and finally the videos promoted excessive drinking with no regards to consequences. Their study concluded, with a caution to the role of advertisers play in the promotion of music video product placements. The placement of alcohol in the videos are often not in line with the “advertising codes of practice”.

Managing the advertising content on social media, has received some attention. In [ 19 ] it was investigated whether organizations conform to their digital marketing standards, even on social media. Specifically, the study focused on the extent alcohol is advertised/promoted on YouTube to viewers that are under the legal drinking age. The also, found that alcohol companies’ digital marketing is not sufficient to protect underage viewers from viewing advertisements that promotes the consumption of alcoholic beverages.

In [ 20 ] it was further reported that alcohol use was presented as a fun, social activity with underage drinkers. A content analysis on 137 YouTube videos were conducted and concluded that YouTube is an effective platform to advertise alcohol use to adolescents.

3.3 Body image/health

The body image/health theme is concerned with the way body image/health information is communicate and perceived on YouTube. Three papers reported on the dissemination of body image/health data on YouTube.

In [ 21 ] an experimental study was conducted to examine the effects of health advice on “adolescent girls’ state of self-objectification, appearance anxiety and preference on products that can be used to enhance appearance”. The study used YouTube videos to inform adolescent girls on healthy behaviors. The results from 154 adolescent girls showed that younger girls tend to self-objectify more. Furthermore, the younger adolescent girls’ self-objectification mediated the effects on appearance anxiety and the use of products to improve their appearance.

In [ 22 ] misinformation spread on YouTube regarding anorexia was investigated. Three doctors analyzed 140 videos on YouTube regarding anorexia. They classified content as “informative, pro-anorexia, or other”. It was found there were less pro-anorexia videos than informational videos creating awareness on anorexia, but pro-anorexia videos were more liked by the viewers. The researchers advocated for more awareness on truthfulness of YouTube videos, especially concerning beauty and lifestyle advice. They recommended that celebrities should be employed to create awareness of anorexia.

In [ 23 ] it was reported on adolescents accessing YouTube videos to learn about weight loss. They reported that adolescents showed negative feelings regarding body image. The exploratory research analyzed 50 videos that were identified by searching with the key word “diet”. Their analysis concluded that the videos did not show appropriate guidelines to safely lose weight as it was made by non-qualified people. They recommended that policies by government should be in place, or at least be present on the YouTube platform to guide the information being made available on YouTube.

3.4 Bullying

Bullying is concerned with the actions to cause physical or emotional harm to another party. Four papers reported on the extent of bullying content visible in YouTube videos. In [ 2 , 31 ] it was identified as a common theme as part of digital vulnerabilities of adolescents. However, two papers focused exclusively on bullying.

In [ 24 ] investigated the degree to which bullying content is present on YouTube. They found that 89 videos showed violence, 38 videos presented content related to suicide. Only 56 videos were promulgating positive messages related to finding help. They concluded that professional agencies should work towards spreading messages to stop bullying behavior.

In [ 25 ] it was reported that YouTube is the most popular social networking platform among Canadian adolescents. This research reported on the analysis of 55 video logs (vlogs) about bullying. They recommended that YouTube can be used as a platform to disseminate and discuss bully behavior.

3.5 Self-harm/suicide

Self-harm/suicide theme is associated with activity to inflict injuries on themselves, or in extreme cases take their own lives. Four papers reported on these types of activities. In [ 32 ] research on the “blue whale challenge” was reported. The “blue whale challenge” encouraged adolescents to self-harm and eventually kill themselves. Through a thematic analysis of comments on 60 publicly posted YouTube videos, they learnt that although the comments were focused on raising awareness of the risks of the challenge, it might encourage vulnerable individuals to partake in the challenge. They advocated for “safe messaging guidelines” to create awareness to social media users on the risks associated with content that promote self-harm/suicide.

In [ 26 ] reference is made to another challenge, namely Tide pod, which encourages non-suicidal self-harm. The analysis of 413 YouTube videos that featured content on self-harm/suicide revealed that 80% of the videos promoted awareness regarding the risks. Other results indicated that an anlysis of the comments revealed that 2.9% of the comments encouraged suicide, 2.1% of the comments were on how to fight suicidal thoughts, 5.4% of the comments were related to the poster wanting to commit suicide and 5.8% of the comments were negative. They concluded that further research is needed to investigate the negative impact social media platforms can have on the mental health of adolescents.

In [ 27 ] the 50 most popular videos depicting self-harm was analyzed. It was revealed that 58% of the videos did not warn viewers of the potential sensitive content to be displayed. The analysis showed that 42% of the videos were portraying a neutral message with regards to self-harm, 27% of the videos discouraged self-harm. However, 23% of the videos provided “mixed messages” regarding self-harm and 7% of the videos encouraged self-harm. They concluded their research by recommending that teachers and parents need to be made aware of self-harm content on YouTube to which vulnerable adolescents can be exposed to.

In [ 28 ] 65 videos that demonstrated the asphyxiation game was analyzed. Results showed that 90% of the videos featured males. The videos demonstrated different asphyxiation techniques, including hypoxic seizures (55%) and the sleeper hold (88%). The researchers concluded that YouTube provides a platform for adolescents to view videos on choking and that continued exposure to such videos might normalize the act of choking. They advocated for increased awareness of this to alert youths to the risks associated with the choking games.

3.6 Advertising

Product advertisement on YouTube, is not always regulated by the same digital marketing guidelines as formal digital marketing platforms. Two papers spoke directly about the advertisement of products in YouTube videos.

Further to the promotion of alcohol in [ 19 ] to underage drinkers, as reported above, another paper investigated the presence of product placement in microcelebrities’ YouTube videos.

In [ 29 ] 1961 comments were analyzed and it revealed that the followers of the specific YouTube channel accepted the commercial content promoted by the star of the YouTube channel. However, they cautioned that viewers are not always aware of product placement, due to lack of transparency, and that viewers might have a skewed view of the life of microcelebrities and the extent to which their lifestyles are supported by industry.

Three papers, [ 2 , 30 , 31 ] reference drugs as being a theme in YouTube videos. Although [ 2 , 31 ] referenced the presence of drugs as a general theme, [ 30 ] explained in detail the effect of Salvia, a short-acting hallucinogenic drug that adolescents in the United States used. The research focused on the analysis of self-taped videos of the use of Salvia. It was reported that the onset of the drugs’ effects was quick, within 30 seconds and lasted for approximately 8 minutes. The research concluded that YouTube was an effective medium to showcase the effect of drug use.

3.8 Vulnerabilities

Through content analysis [ 2 , 31 ] found that YouTube content creators focused on four major themes of: sex, bullying, pregnancy and drugs. These four themes presented the vulnerabilities adolescents are exposed through YouTube content. They concluded that the language used in the YouTube content was aimed at adolescents. Furthermore, they found that the videos that adolescents made themselves, were more often watched by other adolescents. Videos that were made by institutions to promote a certain “positive” message, were not well watched, or distributed.

4. Discussion

The analysis of the 24 articles provided eight “dark side” themes associated with YouTube content that adolescents engage with. These “dark side” themes describe the typical dangers that adolescent can be exposed to when viewing YouTube videos.

It was apparent that a number of videos featured sexualized imagery, in addition to the promotion of smoking and alcohol consumption [ 14 , 18 ]. The promotion of alcohol to underage drinkers were also revealed [ 19 , 20 ].

It was quite interesting to observe that the context in which smoking and alcohol was promoted was through music videos. Often in the music videos, smoking and the consumption of alcohol was perceived as fun, and socializing activities [ 18 ].

A number of papers reported that certain YouTube videos do attempt to create awareness of the risks and dangers associated with some activities promoted on YouTube [ 26 , 32 ]. However, the research reported mixed results. For example, in [ 22 ] it was reported that there are fewer pro-anorexia videos observed from the sample than informational videos that caution against anorexia, however the pro-anorexia videos were more “liked” than the informational videos.

A common theme that emerged from the research was: “regulation”. In [ 14 ] it was stated that the regulation of smoking advertisements, and smoking fetishism is not sufficient. Strong regulations on advertising was also mentioned in [ 19 ]. Advertising Agencies need to be made aware, or realize that the viewers of YouTube content are becoming younger [ 6 ], and potentially more vulnerable due to the desensitizing effect of over consumption of YouTube content. The promotion of inappropriate products, such underage drinking and smoking, and the potential unawareness of a young viewer of intentional product placement [ 29 ] need to be more effectively regulated. Adolescents are greatly influenced by social media influencers [ 33 ] or microcelebrities [ 29 ] and although the intention of these influencers or microcelebrities are not always negative, they might unintentionally promote negative behavior. Furthermore, the use of “corrective messages” [ 16 ] to counteract the effect of making smoking socially acceptable. This was also advocated by [ 24 ] who argued that governmental institutions or professional organizations invest in the promulgation of “positive messages” to prevent bullying and assist adolescents who are/have been bullied.

Parents need to be aware of the availability of potentially harmful content on YouTube (also other video sharing platforms such as Tic Toc). Often, the harmful videos do not limit underage or vulnerable viewers to access the content. Although it was shown that some videos to promulgate health messages, parents need to ensure that their children do not get desensitized due to the over consumption of content. Children often do not understand the risks associated with certain “fun” activities such as freaking [ 17 ] or games [ 26 , 32 ].

Adolescents’ motivation of social media use in general can provide the explanation of the impact it can have on adolescent well-being. In [ 1 ] it was shown that motivation for social media use which include passing the time or escapism are inversely related to well-being and body satisfaction and well-being respectively. Therefore, apart from the “negative message” received on social media, such as YouTube, the reason for “escaping” or “passing the time” using social media can further have a detrimental effect on adolescent well-being.

5. Conclusions

YouTube (and similar video sharing platforms) is a popular social media platform for adolescents. Although not all the content on YouTube is problematic, this research has shown that there is truly worrisome content on YouTube which adolescents, especially young adolescents have free access to. Although social media use in general need to be regulated, parents need to regulate the content that their younger adolescents consume of YouTube as the do not always understand the risks associated with the content presented. Also, due to the presentation of some content as “fun” and “sociable”, it can normalize viewers into believing that it is acceptable to partake in illustrated activities.

Apart from “being aware” of potential harmful content on YouTube which can have a detrimental impact on the well-being of adolescents, regulating authorities need to capitalize on the prolific viewership of YouTube by promoting “positive messages” on YouTube.

Furthermore, although the focus of the study was on uncovering the themes that can promulgate “negative messages”, parents, users and regulators need to be aware that the motivations of adolescents’ YouTube use might in itself be harmful to their well-being.

Due to the limited number of empirical studies conducted on the “dark themes of YouTube”, future research can be dedicated to uncovering the impact these dark themes have on the well-being of adolescents.

- 1. Jarman HK, Marques MD, McLean SA, et al (2021) Motivations for Social Media Use: Associations with Social Media Engagement and Body Satisfaction and Well-Being among Adolescents. J Youth Adolescence. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-020-01390-z

- 2. Montes-Vozmediano M, García-Jiménez A, Menor-Sendra J (2018) Teen videos on YouTube: Features and digital vulnerabilities. Comunicar, English ed 26:61-69. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.3916/C54-2018-06

- 3. Claire B, Link to external site this link will open in a new window, Florence M, et al (2020) Searching for Oneself on YouTube: Teenage Peer Socialization and Social Recognition Processes. Social Media + Society 6:. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.1177/2056305120909474

- 4. Weinstein E, Kleiman EM, Franz PJ, et al (2021) Positive and negative uses of social media among adolescents hospitalized for suicidal behavior. Journal of Adolescence 87:63-73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2020.12.003

- 5. Fabris MA, Marengo D, Longobardi C, Settanni M (2020) Investigating the links between fear of missing out, social media addiction, and emotional symptoms in adolescence: The role of stress associated with neglect and negative reactions on social media. Addictive Behaviors 106:106364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2020.106364

- 6. (2021) 25 YouTube Statistics that May Surprise You: 2021 Edition. In: Social Media Marketing & Management Dashboard. https://blog.hootsuite.com/youtube-stats-marketers/ . Accessed 22 May 2021

- 7. (2019) 73+ YouTube Statistics Everyone Should Know in 2021. In: TechJury. https://techjury.net/blog/youtube-statistics/ . Accessed 23 May 2021

- 8. Hattingh M (2017) A Preliminary Investigation of the Appropriateness of YouTube as an Informal Learning Platform for Pre-teens. In: Xie H, Popescu E, Hancke G, Fernández Manjón B (eds) Advances in Web-Based Learning – ICWL 2017. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 101-110

- 9. Dyosi N, Hattingh M (2018) Understanding the Extent of and Factors Involved in the Use of YouTube as an Informal Learning Tool by 11- to 13-Year-Old Children. In: Wu T-T, Huang Y-M, Shadiev R, et al (eds) Innovative Technologies and Learning. Springer International Publishing, Cham, pp 351-361

- 10. Xiaoli Gao, Hamzah SH, Kar Yung Yiu C, et al (2013) Dental Fear and Anxiety in Children and Adolescents: Qualitative Study Using YouTube. Journal of Medical Internet Research 15:18-18. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2290

- 11. Ohlrichs Y, Roosjen H (2017) Youtube Series Support Dutch Girls in Choosing a Contraceptive Method. Journal of Sexual Medicine 14:e275–e275. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.04.327

- 12. Clerici CA, Veneroni L, Bisogno G, et al (2012) Videos on rhabdomyosarcoma on YouTube: an example of the availability of information on pediatric tumors on the web. Journal of pediatric hematology/oncology 34:e329–e331. https://doi.org/10.1097/MPH.0b013e31825886f8

- 13. Braun V, Clarke V (2012) Thematic analysis. pp 57-71

- 14. Kim K, Paek H-J, Lynn J (2010) A Content Analysis of Smoking Fetish Videos on YouTube: Regulatory Implications for Tobacco Control. Health Communication 25:97. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/10410230903544415

- 15. Cranwell J, Opazo-Breton M, Britton J (2016) Adult and adolescent exposure to tobacco and alcohol content in contemporary YouTube music videos in Great Britain: a population estimate. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 70:488. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206402

- 16. Romer D, Jamieson PE, Jamieson KH, et al (2017) Counteracting the Influence of Peer Smoking on YouTube. Journal of Health Communication 22:337-345. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/10810730.2017.1290164

- 17. Nasim A, Blank MD, Cobb CO, et al (2014) How to freak a Black & Mild: a multi-study analysis of YouTube videos illustrating cigar product modification. Health Education Research 29:41-57. https://doi.org/10.1093/her/cyt102

- 18. Cranwell J, Britton J, Bains M (2017) “F*ck It! Let’s Get to Drinking--Poison our Livers!”: a Thematic Analysis of Alcohol Content in Contemporary YouTube MusicVideos. International Journal of Behavioral Medicine 24:66-76. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.1007/s12529-016-9578-3

- 19. Barry AE, Johnson E, Rabre A, et al (2015) Underage Access to Online Alcohol Marketing Content: A YouTube Case Study. Alcohol and Alcoholism 50:89-94. https://doi.org/10.1093/alcalc/agu078

- 20. Mayor S (2017) YouTube videos promote positive images of alcohol, finds study. BMJ: British Medical Journal (Online) 358:. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.1136/bmj.j4365

- 21. Aubrey JS, Speno AG, Gamble H (2020) Appearance Framing versus Health Framing of Health Advice: Assessing the Effects of a YouTube Channel for Adolescent Girls. Health Communication 35:384-394. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1564955

- 22. Syed-Abdul S, Fernandez-Luque L, Jian W-S, et al (2013) Misleading Health-Related Information Promoted Through Video-Based Social Media: Anorexia on YouTube. Journal of Medical Internet Research 15:. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.2196/jmir.2237

- 23. Gurgel CA, Polo GP, dos Santos MSRF, et al (2017) Videos About Diets Broadcast on Youtube: A Communication Channel Very Accessed by Adolescent. Annals of Nutrition & Metabolism 71:544

- 24. Basch CH, Ruggles KV, Berdnik A, Basch CE (2017) Characteristics of the most viewed YouTube™ videos related to bullying. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health 29:1872-4. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.1515/ijamh-2015-0063

- 25. Caron C (2017) Speaking Up About Bullying on YouTube: Teenagers’ Vlogs as Civic Engagement. Canadian Journal of Communication 42:645-668. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.22230/qc2017v42n4a3156

- 26. Dagar A, Falcone T (2020) High Viewership of Videos About Teenage Suicide on YouTube. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 59:1-3.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaac.2019.10.012

- 27. Potera C (2011) YouTube Self-Harm Videos Under Scrutiny. AJN The American Journal of Nursing 111:20. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NAJ.0000398530.98917.3f

- 28. Linkletter M, Gordon K, Dooley J (2010) The Choking Game and YouTube: A Dangerous Combination. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 49:274-279. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922809339203

- 29. de Carvalho BJ, Marôpo L (2020) “I’m Sorry You Don’t Flag It When You Advertise”: Audience and Commercial Content on the Sofia Barbosa Youtube Channel. Comunicação e Sociedade 37:93-107. https://doi.org/10.17231/comsoc.37 (2020).2394

- 30. Lange JE, Daniel J, Homer K, et al (2010) Salvia divinorum : Effects and use among YouTube users. Drug & Alcohol Dependence 108:138-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.11.010

- 31. Jiménez AG, Link to external site this link will open in a new window, Vozmediano MM (2020) Subject matter of videos for teens on YouTube. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth 25:63-78. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.1080/02673843.2019.1590850

- 32. Khasawneh A, Link to external site this link will open in a new window, Madathil KC, et al (2020) Examining the Self-Harm and Suicide Contagion Effects of the Blue Whale Challenge on YouTube and Twitter: Qualitative Study. JMIR Mental Health 7:. http://dx.doi.org.uplib.idm.oclc.org/10.2196/15973

- 33. van Eldik AK, Kneer J, Lutkenhaus RO, Jansz J (2019) Urban Influencers: An Analysis of Urban Identity in YouTube Content of Local Social Media Influencers in a Super-Diverse City. Front Psychol 10:2876. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02876

- 30 May 2021

© 2021 The Author(s). Licensee IntechOpen. This chapter is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License , which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Continue reading from the same book

Edited by Massimo Ingrassia

Published: 09 November 2022

By Jocelyn Lachance

232 downloads

By Loredana Benedetto, Ilenia Schipilliti and Massimo...

89 downloads

By Doina-Carmen Manciuc, Cristina Sapaniuc, Alexandra...

179 downloads

Advertisement

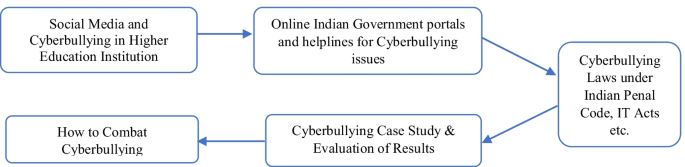

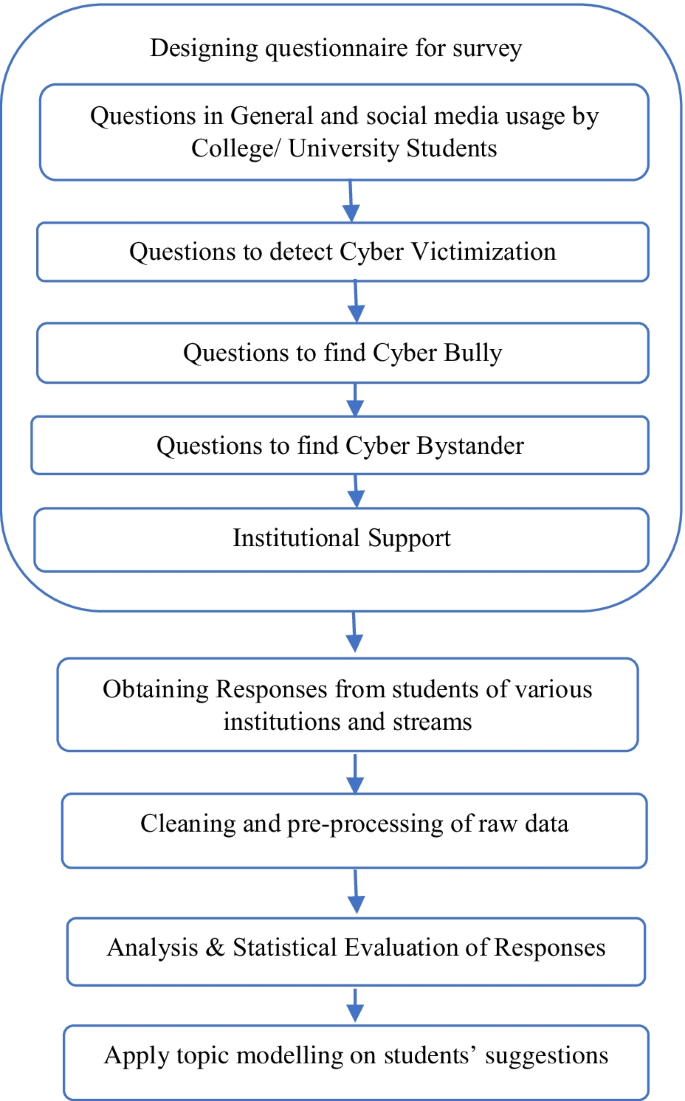

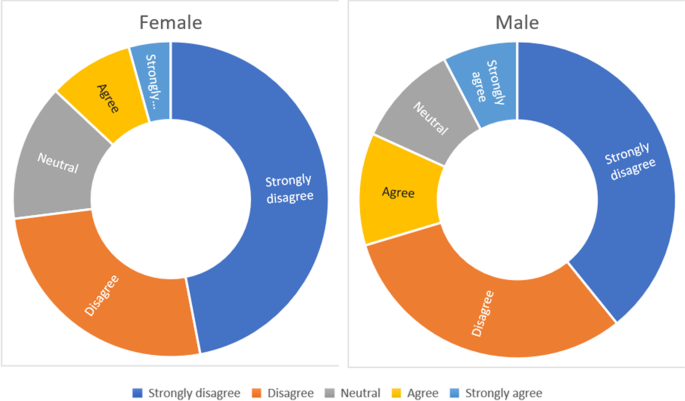

Indian government initiatives on cyberbullying: A case study on cyberbullying in Indian higher education institutions

- Published: 04 July 2022

- Volume 28 , pages 581–615, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

- Manpreet Kaur ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7680-3075 1 &

- Munish Saini ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4129-2591 1

20k Accesses

15 Citations

Explore all metrics

In the digitally empowered society, increased internet utilization leads to potential harm to the youth through cyberbullying on various social networking platforms. The cyberbullying stats keep on rising each year, leading to detrimental consequences. In response to this online threat, the Indian Government launched different helplines, especially for the children and women who need assistance, various complaint boxes, cyber cells, and made strict legal provisions to curb online offenses. This research evaluates the relevant initiatives. Additionally, a survey is conducted to get insights into cyberbullying in higher education institutions, discussing multiple factors responsible for youth and adolescents being cyberbullied and a few measures to combat it in universities/colleges.

Similar content being viewed by others

Cyberbullying in the University Setting

Exploratory Research to Identify the Characteristics of Cyber Victims on Social Media in New Zealand

Destructive Digital Ecosystem of Cyber Bullying Perfective Within the Information Technology Age

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

1 Introduction

Cyberbullying is harassment done to the victim to cause harm via any electronic method, including social media resulting in defamation, public disclosure of private facts, and intentional emotional distress (Watts et al., 2017 ). It can be related to sending and posting cruel texts or images with the help of social media and other digital communication devices to harm a victim (Washington, 2015 ). It is a repeated behavior done by the individual with the help of social media, over the gaming, and messaging platforms that target mainly to lower the victims' self-esteem.

In the past decade, Cyberbullying has been an emerging phenomenon that has a socio-psychological impact on adolescents. With the advancement of digital technology, youth is more attached to social media, resulting in cyberbullying. With the increasing usage of techno-savvy gadgets, social media applications are highly prevalent among the youth, which can be advantageous and disadvantageous. It allows sharing posts, photos, and messages personally and privately among friends, while on the other hand, it involves an increase in cyberbullying by creating fake accounts on the apps (Ansary, 2020 ).

In July 2021, 4,80 billion people worldwide were on social media, that's almost 61% of the world's total population depicting an annual growth of 5.7% as 7 lac new users join per day (Digital Around the World, 2021 ). As the number of users increases, there is a surge in cyberbullying; according to a UNICEF poll, more than 33% of youngsters are reported as victims of online bullying in 30 countries worldwide (UNICEF, 2020 ). Moreover, it is seen that one in five has skipped school due to fear of cyberbullying and violence. According to NCRB, 50,035 cases of cybercrime were reported in India in the year 2020, among which 1614 cases of cyberstalking, 762 cases of cyber blackmailing, 84 cases of defamation, 247 cases of fake profiles, and 838 cases of fake news were investigated. NCRB data Footnote 1 reported that cybercrimes in India increased by 63.48% (27248 cases to 44548 cases) from 2018 to 2019, which upsurged by 12.32% in 2020 (44548 cases to 50035cases).

Multiple cases of cyberbullying were reported across the country. As per news reports, in November 2016, a 23-year-old Ooshmal Ullas, MBBS student of KMCT Medical College in Mukkam, Kerala, committed suicide by jumping due to being cyberbullied over a Facebook post and injured her spine, legs, and head. Footnote 2 One more incident was reported on 9 January 2018 where a 20 years old Hindu woman killed herself after facing harassment on WhatsApp over her friendship with a Muslim man in Karnataka. Footnote 3 Another case was witnessed, a 15-year-old boy connected with the 'Bois locker room', an Instagram group where they share photos of minor girls and exchange lewd comments, was arrested by Delhi police on 4 May 2020. Footnote 4 An incident occurred on 26 June 2014 a 17 years old girl committed suicide after Satish and Deepak, her friends, morphed her photos and posted them on Facebook along with her cell phone number. Footnote 5 Many such cases are reported every year, and this rising number of suicides due to cyberbullying is alarming and worrisome.

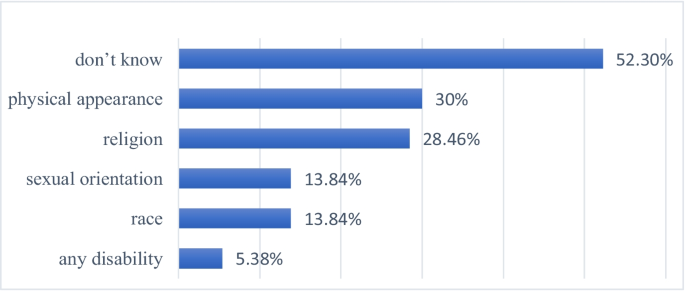

The primary cause of cyberbullying is anonymity, in which a bully can easily target anyone over the internet by hiding their original identity. The psychological features play an eminent role in determining whether a person is a victim or a bully. A pure bully has a high level of aggression and needs succorance, whereas the pure victim has high levels of interception, empathy, and nurturance (Watts et al., 2017 ). It has been found that various factors are responsible for becoming a cyberbully. According to Tanrikulu (Tanrikulu & Erdur-Baker, 2021 ), Personality traits are responsible for cyberbullying behavior. The primary cause is online inhibition, in which a person bullies others with the motives of harm, domination, revenge, or entertainment. Other causes are moral disengagement as the findings imply that, regardless of the contemporaneous victimization status, moral disengagement has an equal impact on bullying perpetration for those who are most engaged. Pure bullies have more moral disengagement than those bullies/victims who aren't as active in bullying (Runions et al., 2019 ). The next one is Narcissism , which means individuals consider social status and authority dominant over their human relations. The last is aggression, which refers to overcoming negativities and failures by force, triggering them to do cyberbullying for satisfaction. Similarly, there are some personality traits associated with cyberbullying participants as a study (Ngo et al., 2021 ) examined three groups of online users where the first one is the "Intervene" group which believes in uplifting the morale of victims by responding to cyberbullying acts while others are the "Ignore" group that doesn't involve in reacting to the cyberbullying acts and just ignores the victims or leave the cyberspace and the third one is "Join in" that either promote the bullying or just enjoy watching cyberbullying act without any participation. The adolescents belonging to intervene group may play a critical role in reducing cyberbullying behavior and its consequences.