Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- My Account Login

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Review Article

- Open access

- Published: 19 June 2020

The social brain of language: grounding second language learning in social interaction

- Ping Li ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-3314-943X 1 &

- Hyeonjeong Jeong ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-5094-5390 2

npj Science of Learning volume 5 , Article number: 8 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

38k Accesses

41 Citations

38 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

For centuries, adults may have relied on pedagogies that promote rote memory for the learning of foreign languages through word associations and grammar rules. This contrasts sharply with child language learning which unfolds in socially interactive contexts. In this paper, we advocate an approach to study the social brain of language by grounding second language learning in social interaction. Evidence has accumulated from research in child language, education, and cognitive science pointing to the efficacy and significance of social learning. Work from several recent L2 studies also suggests positive brain changes along with enhanced behavioral outcomes as a result of social learning. Here we provide a blueprint for the brain network underlying social L2 learning, enabling the integration of neurocognitive bases with social cognition of second language while combining theories of language and memory with practical implications for the learning and teaching of a new language in adulthood.

Similar content being viewed by others

The language network as a natural kind within the broader landscape of the human brain

People are surprisingly hesitant to reach out to old friends

Cortical gene expression architecture links healthy neurodevelopment to the imaging, transcriptomics and genetics of autism and schizophrenia

The study of the neuroscience of cognition has made great strides in the last two decades, thanks to the rapid developments in non-invasive neuroimaging techniques and the corresponding data analytics. At the same time, the study of language acquisition, including second language (L2) learning by children and adults, has also progressed significantly from behavioral research toward neurocognitive understanding, thanks also to new methods including neuroimaging. These two domains of study (i.e., cognitive neuroscience and language learning) have seen increasingly happy marriages of approaches, theories, and methodologies in the last two decades, driven largely by the New Science of Learning 1 , a framework for studying learning at the intersection of psychology, neuroscience, education, and machine learning. Specifically, this framework argues that learning should be studied along three important dimensions: a computational process, a social process, and a process supported by brain circuits linking perception and action. Meltzoff and colleagues 1 further suggested that human language acquisition provides a bona fide example for connecting computational learning, social learning, and brain circuits for perception and action. Despite the call from this multi-disciplinary perspective, researchers in cognitive neuroscience and language acquisition have remained to focus on the individual learner, especially in the study of adult L2 learning. This tradition has seriously limited our understanding of a key aspect of what it means to learn: learning in the social context, interactively.

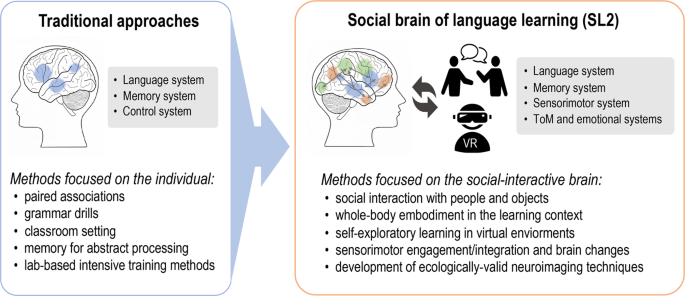

The study of language learning focused on the individual might have had its origin in the tradition of generative linguistics 2 , 3 , according to which linguistics as a science should study the language competence of the idealized speaker and the corresponding innate mechanisms that enable humans to learn language. Although the neuroscience of language has largely avoided accepting the generative tradition, the focus on the individual, and consequently, the brain structure and function of the individual (i.e., the “single-brain” approach 4 ), has not changed as a field (see Fig. 1 for illustration ) . This is unfortunate, since language serves a social communicative purpose and is fundamentally a social behavior. Note that there are some exceptions to this focus, especially in (a) the study of child language learning (see discussion next), and (b) social neuroscience, which has begun to focus on how brains respond to social interactions using methodologies such as hyper-scanning 4 , 5 . In addition, although leading models of the neurobiology of language do not incorporate a social component 6 , there have been recent efforts to extend the landscape to include pragmatic reasoning 7 , theory of mind 8 , and social interaction 9 .

Left: Traditional approaches for “single-brain” study of language learning; Right: “Social-interactive brain” research and emerging methods.

In this paper, we advocate an approach focused on grounding L2 learning in social interaction; we call this approach “Social L2 Learning” (SL2). Specifically, we define “social interaction” here as “learning through real-life or simulated real-life environments where learners can interact with objects and people, perform actions, receive, use, and integrate perceptual, visuospatial, and other sensorimotor information, which enables learning and communication to become embodied.” Notwithstanding generative linguistics and individual-brain study approaches, the field of first language (L1) acquisition has clearly demonstrated that children, from the earliest stages, depend on social interactions to learn 1 . This dependence may be initially coordinated through “joint attention” and shared intentionality between the infant and the parent/caregiver 10 . Computational models that incorporate social-interactive cues from mother–child interactions perform significantly better than models with no such cues included 11 , 12 . Kuhl et al. 13 further indicated that social learning is crucial even when children learn an L2: American babies exposed to Mandarin Chinese through a “DVD condition” (pre-recorded audiovisual or audio-only material) did not demonstrate learning of Mandarin phonetic categories as did babies who were exposed to the same material through a “live condition” (experimenter interacting with the infant during learning). For adults, however, folk wisdom suggests that they can learn an L2 rapidly without social cues (e.g., through intensive training in a classroom) and may be less dependent on the presence of peer learners. Limited evidence, however, suggests that social cues such as joint attention may also enhance L2 learning success through orienting the learner’s attention to the correct meaning among competing alternatives 14 .

Theoretical frameworks for understanding the social brain of language Learning

The proposed SL2 model is focused on grounding L2 learning in social interaction based on both behavioral and brain data. A number of important theoretical framworks have already paved the way for the SL2 model, some of which are separately known in the domains of psycholinguistics, memory, and cognition, respectively.

First, while the classic Critical Period Hypothesis 15 suggests a biology-based account of effects of age of acquisition (AoA) on learning, the Competition Model, in its various formulations 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 , 20 , provides a social-based and interactive-emergentist account of the differences between L1 and L2 learning. Upon this account, the principles of learning are not fundamentally different between the child learning an L1 and the adult learning an L2 (e.g., contra the “less is more” hypothesis 21 ), but the processes and contexts within which learning takes place may be significantly different. For children, language learning is a natural event that unfolds in the environment where they grow up. They can naturally integrate the rich perceptual and sensorimotor experiences from this environment, interacting with the objects and people and performing actions in it. Picking up and using a spoon while hearing the sound “spoon” is part of the learning process, which differs from the process where adults sitting in the classroom look at a picture of spoon and associate it to an existing label in their native language. According to MacWhinney 17 , adult L2 learning is susceptible to several major “risk factors”, factors that prevent adults from acquiring a foreign language to native competence. These include thinking in L1 only (which implies the need to translate from L2 to L1 rather than directly using L2 as a medium), social isolation (learning as an individual or through in-group communities only), and lack of perception-action resonance (lack of direct contact with the target objects or actions in the environment while learning L2). These risk factors, particularly social isolation and lack of perception-action-based contexts, may explain why adult learners display the strong parasitic L2-on-L1 representations 22 : on the one hand, adults typically start to learn L2 when they have already established a solid L1 (“entrenchment” in L1), which lends easily to L2-to-L1 translation and association; on the other hand, they lack a dynamic and variable environment to build direct relations between L2 words and the objects/concepts to which the words refer 23 . With regard to the risk factors of thinking in L1 and social isolation, empirical evidence has shown that study-abroad experience may provide some environmental support, particularly in attenuating L1 to L2 interference for late adult learners 24 .

These theoretical perspectives are consistent with a larger trend in psycholinguistics to examine language learning and bilingualism not as an individualized but a general communicative experience. Adults show significant differences in how they learn two (or more) languages, the frequency and contexts with which they use the languages, and the communicative purposes for which each language is needed, therefore showing that bilingualism is a highly dynamic developmental process 19 , 25 , 26 , 27 . The SL2 approach advocated here also echoes a movement in the broader language science, from sociocultural theory 28 to usage-based language learning 29 and conversational analysis 30 , all of which view language learning as a socially grounded process. Ellis 31 summarizes this movement with regard to its focus on “how language is learned from the participatory experience of processing language during embodied interaction in social and cultural contexts where individually desired outcomes are goals to be achieved by communicating intentions, concepts, and meaning with others.”

Second and independently, human memory research suggests that item-based learning (encoding) and use (retrieval) are highly interdependent. This is due to the associative nature of memory, in which the cognitive operations used for encoding stimulus items directly impact their subsequent retrieval. A well-established hypothesis in this regard is the “encoding-specificity” principle 32 , according to which semantic memories are more successfully retrieved if they are recalled in the same context as when they were originally encoded (e.g., if word lists were encoded underwater they would be recalled better underwater than on dry land 33 ). Related to this hypothesis is the “levels of processing” theory 34 that suggests deeper, more elaborative, or richer semantic processing during encoding would lead to more successful retrieval than shallow or surface-level processing of the same material. If encoding involves more elaborative semantic processing, e.g., using multimodal information, it will have a positive impact on memory retention and retrieval. Both the “dual encoding” theory 35 and the multimedia learning theories 36 suggest that elaborative processing with multimodal sensory information could enhance the quality of semantic memory, hence leading to better recall. One of the predictions here is a “multimodal advantage” such that, for example, people learn better with words and pictures together than with words alone 37 .

There have been several studies that build on the encoding-specificity principle to account for bilingual language processing. Marian and Kaushanskaya 38 proposed a language-dependent memory hypothesis to explain bilingual semantic/conceptual representation, according to which language is encoded in the episodic memory of an event and therefore forms part of one’s autobiographical memory. It is this episodic encoding that influences the accessibility of semantic memories. They observed that memories were more accessible when retrieved in the same language in which they were originally encoded or learned. Furthermore, this language specificity in bilingual memory is influenced by variables such as AoA, proficiency in the L2, and history of usage in the two languages 39 , 40 ; for example, richer memories were associated with an earlier age of L2 learning.

The richness of memory with regard to AoA may be explained by the rich episodic experiences/events associated with specific perceptual-sensory features in the environments, perhaps because early L1 learning includes these experiences but late L2 learning typically does not. This leads us to the embodied cognition theory 41 , 42 , according to which body-specific (e.g., head, hand, foot) and modality-specific (e.g., auditory, visual, tactile) experiences form an integral part of the learner’s mental representation of concepts, objects, and actions. This contrasts with classic cognitive theories of symbolic representation that argue that cognition and cognitive operations are modular, and that language is unrelated to the rest of cognition including perception and action 43 , 44 . The embodied cognition theory highlights the whole-body interaction with the context, that is, “interaction between perception, action, the body and the environment” 45 , and when engaged, will also activate the brain’s perceptual and sensorimotor cortex 46 , 47 . Although the embodied cognition hypotheses have been examined in many studies of brain and behavior, so far, the focus has been on native L1 speakers; whether and how body-specific and modality-specific experiences play the same role in L2 learning has not received much attention 48 , 49 . Our SL2 model argues for the important role of social interaction for L2 learning and draws on the link between learning and perception and action, as suggested by the New Science of Learning framework 1 .

Social interaction for second language learning: neuroimaging evidence

How do the theoretical frameworks above shed light on our SL2 approach in understanding the social brain of L2 learning? Although many recent neuroimaging studies have examined brain changes resulting from L2 learning 50 , most of this literature has focused on traditional L2 learning methods such as rote memorization or translation-based learning, in either classroom settings or lab-based intensive training 51 , 52 , 53 , 54 , 55 . Their findings suggest largely the engagement of language-related neural networks (e.g., the classic frontal-parietal network) and memory-related brain regions (e.g., the medial temporal region for the learning and consolidation of linguistic information; see Fig. 1 for illustration). So far, only a handful of studies have provided initial evidence on the neural networks implicated in social-based L2 learning, pointing to the following key patterns.

First, the supramarginal gyrus (SMG) and the angular gyrus (AG) could play a significant role. In one of the first studies in this domain, Jeong et al. 56 trained Japanese speakers to learn Korean words under two conditions, either through L1 translation or simulated social interaction in which the participants watched videos that showed joint activities in real-life situations (e.g., the L2 target word “Dowajo”, meaning help me in English, is shown in the video with an actor trying to move a heavy bag and asking another actor for help). The authors then asked participants to retrieve the target L2 words in a functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) session. The results indicated that the words learned through videos with social interactions produced more activation in the right SMG whereas the words learned from translation produced more activity in the left middle frontal gyrus (MFG). Interestingly, retrieval of L1 words (acquired by these participants in childhood through daily life) also produced greater activation in the right SMG. These findings can be interpreted to suggest that L2 words learned via social interaction (as simulated in videos through short-term training) are processed in a similar fashion as L1 words.

Second, the right inferior parietal cortex (IPL, including both SMG and AG) has been implicated more strongly in virtual reality-based (VR) interactive learning as compared with non-virtual, word-to-picture association, learning 57 . Legault and colleagues found that cortical thickness, a structural brain measure of gray-matter thickness from the surface of the cortex to the white matter, is associated with different contexts of learning: after 2–3 weeks of intensive L2 vocabulary training across seven sessions, the VR learners showed a positive correlation in the right IPL with performance across all training sessions, while the non-VR learners showed a positive correlation at the final stages only in the right inferior frontal gyrus (IFG), a region associated with effective explicit language training 58 (though there is counter evidence 59 ). Furthermore, cortical thickness in the right SMG was correlated with higher accuracy scores of the delayed retention test, but only for the VR learning group. The VR group was engaged in 3D virtual environments in which the learners could dynamically view or play with the objects in an interactive manner.

Third, the right SMG is shown to be more activated in simulated partner-based learning than individual-based learning of word meanings, indicating that the mere presence of a social partner would facilitate L2 word learning 59 , like in child language learning. Verga and Kotz 59 further found that participants with higher learning outcomes showed higher activity in the right IFG during an interactive learning condition but not during an individualized non-interactive learning condition. Levels of activity in the right lingual gyrus (LG) and right caudate nucleus (CN), previously implicated in visual search process and visuospatial learning, were also found to correlate with temporal coordination between a learner and a partner during simulated interactive learning.

These brain imaging data suggest that social-based L2 learning versus classroom-based individual learning conditions can lead to distinct neural correlates; for example, social learning of L2 may engage more strongly the brain regions for visual and spatial processing 57 , 59 , which may have consequences on both encoding (learning) and retrieval of information (memory). In contrast to the idea that only the child brain may respond to social learning, these findings suggest that the adult brain displays significant neuroplasticity in response to social interaction. Jeong et al. 56 showed that if an L2 word was initially encoded in a more socially interactive condition (through video simulations), it engaged the relevant brain areas as in L1, areas that would not become activated if learning had occurred through word association or translation as in a typical L2 classroom.

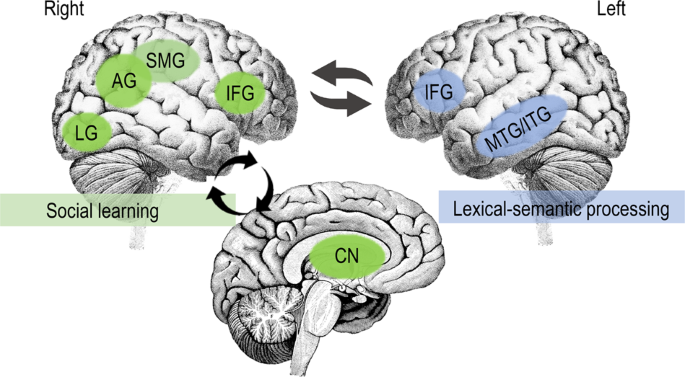

Figure 2 illustrates the proposed neural correlates of social interaction in the frontal, parietal, and subcortical regions for L2 learning. The strong engagement of the SMG, AG, IFG, along with the visual (LG) and subcortical regions (CN), may form an important neural network for understanding how SL2 is instantiated in the human brain. Importantly, this network highlights the stronger role of the right-hemisphere brain regions as compared with the typical left-lateralized language networks. The IFG has long been implicated in lexical-semantic processing and its integration with memory 60 , which is shown bilaterally in both hemispheres in Fig. 2 . The other regions, the SMG, AG, LG, CN, are illustrated in Fig. 2 on the right hemisphere. The role of this “right-heavy” network is evidence of the significant neurocognitive impacts of social L2 learning as opposed to traditional methods (Fig. 1 ).

The left hemisphere regions (blue) handle lexical-semantic processing, while the right hemisphere cortical plus the subcortical regions (green) participate in social learning. IFG inferior frontal gyrus, SMG supramarginal gyrus, AG angular gyrus, LG lingual gyrus, CN caudate nucleus, MTG/ITG middle temporal gyrus/inferior temporal gyrus (Note: the right hemisphere is depicted on the left side and left hemisphere on the right side).

There are a number of important issues for further consideration with regard to the SL2 network charted in Fig. 2 . First, it is important to understand how the various areas collaborate and communicate with each other during learning and memory. A true brain network is one that involves modules, communities, and pathways that are dynamically connected and organized. An important research direction in neuroscience today is the network science approach towards the analysis of functional/structural brain patterns underlying cognition, and significant advances have been made in applying this approach to the understanding of neural circuits of learning and memory, including L2 learning 61 , 62 , 63 . It remains to be understood how the left frontal IFG and right parietal IPL areas (including SMG and AG) form a dynamic network in support of SL2 learning, alongside the visual and subcortical regions (LG and CN). It is possible that the LG and CN regions play an important early role in visuospatial analysis and learning in social settings, which feeds into action-based lexico-semantic and conceptual integration that heavily involves the SMG and AG regions, as evidenced in studies by Verga and Kotz 59 , Jeong et al. 56 , and Legault et al. 48 . The IFG then coordinates this network with significant participation of semantic memory and cognitive control as well as lexical retrieval 64 . In this regard, the IFG also plays a significant role in modulating competition between L1 and L2 in a language control network 19 , 65 .

Second, a related issue for further study is how such neural networks evolve during development, which would allow us to understand the degree to which time of learning (e.g., AoA), extent of learning, and increased proficiency may impact the dynamic changes in the neural network 50 . Elsewhere significant progress has been made in this domain 20 , 66 , 67 , but the focus there has been on the relationship between cognitive control and bilingualism and the related debate on bilingual cognitive advantage (see a recent discussion 25 ). Methodologically, to study the developmental process we will also need to pursue longitudinal neuroimaging work 51 as well as short-term intensive training paradigms. Finally, much work is needed for understanding how the SL2 network may overlap with neural networks implicated in other types of social interaction 68 , 69 . Hagoort and Indefrey 7 , 70 suggested that pragmatic inference in language processing involves the “theory of mind” (ToM) or the mentalizing network 71 , 72 , in which the medial prefrontal (mPFC), along with the temporoparietal junction (TPJ) regions, play an important role in social reasoning such as thinking about other people’s beliefs, emotions, and intentions. Not surprisingly, the extended language network (ELN) hypothesis for narrative text comprehension 73 significantly overlaps with the ToM network, involving mPFC and the TPJ in building story coherence, drawing inference, and interpreting pragmatic meaning in the narrative story being read. The ELN network allows the reader to follow the plots, empathize with the characters, and take the protagonist’s perspectives 74 , 75 . We hypothesize that the SL2 network in Fig. 2 dynamically connects to mPFC and TPJ implicated in ToM and social reasoning, although this hypothesis needs to be examined carefully by comparing learning with social interaction versus without.

New approaches toward SL2 as a theoretical hypothesis and a practical model

Embodied semantic representation in l1 and l2.

In a typical adult L2 learning setting, students rely on translation/association of two languages and rote memory, unlike the child who acquires the L1 with sensorimotor experiences in an enriched perceptual environment. For example, in an L2 classroom, the teacher introduces a new L2 word (e.g., Japanese “inu”) by its translation equivalent in the L1 (e.g., English “dog”) and the learner’s task is to form paired associations between L1 and L2 when learning the L2 vocabulary. Although this method is efficient early on, it leads to what is called a parasitic lexical representation: the L2 word is conveniently linked to a conceptual system already established through the L1 19 , 22 . Because the task of word association or translation does not encourage direct L2-to-concept relations, the link from the L2 word to the concept is weak, and has to be indirectly mediated via the L1-to-concept link 23 . More significantly from the SL2 perspective is the “collateral damage” of this parasitism: the new L2 representation lacks the relevant perceptual-spatial-sensorimotor features (e.g., shape, size, motion and location of “inu” or dog), features that are an integral part of the lexical-semantic representation in the L1.

Why can’t the adult L2 learner take the newly acquired L2 representation and map it to the rich embodied features in the L1 representational system, given that would be the most efficient way? Several computational models 22 , 76 , 77 have systematically manipulated the timing of adding new L2 items to L1 lexical structure during simultaneous or sequential learning of the two languages and showed that the L2 lexical organization is sensitive to AoA: the later L2 is learned, the less well organized and more fragmented the L2 representations are. Thus, parasitism is characteristic of L2 semantic learning in late adulthood. Hernandez et al. 19 and Li 78 attributed this to the mechanism of “entrenchment”, in which the lexical structure established by the L1 early on is entrenched to resist radical changes during later L2 learning. The entrenchment may have led to late adult L2 learner’s inability to map L2 forms directly to the rich L1 lexico-semantic representations. In a recent neuroimaging study comparing L1 vs. L2 embodied semantic representations, Zhang et al. 79 showed that L1 speakers engage a more integrated brain network connecting key areas for language and sensorimotor integration during lexico-semantic processing, whereas L2 speakers fail to activate the necessary sensorimotor information, recruiting a less integrated embodied brain system for the same task.

The persistent parasitism could also be attributed to the different contexts in which the two languages have been learned. Recent evidence from affective processing indicates that affective-specific experiences are more strongly evoked in L1 than in L2 words due to the different contexts of social learning (e.g., family vs. workplace interactions) and the co-evolution of emotional regulation systems with early language systems 80 , 81 , 82 . Consistent with embodied semantic differences 79 , such emotionality differences between L1 and L2 have been found most reliable when the L2 is a later-learned or less proficient language 80 , showing evidence that the L2 representation, if acquired late, cannot easily incorporate the rich social and affective features of the L1 representation.

How can the L2 learner break away from this parasitism so as to establish the L2 representation on a par with the L1 representation? SL2 provides a theoretical framework for addressing this question from an embodied cognition perspective. Recent work suggests that embodied actions, even when no direct social interaction is involved, can impact learning outcomes simply by engaging the body, for example, through gestures. Mayer et al. 49 showed neurocognitive differences between (a) L2 vocabulary learning with gestures that activated the superior temporal sulcus, STS, and the premotor areas, versus (b) learning without gestures that activated the right lateral occipital cortex only. Critically, learners in the gesture condition showed significantly better memory for L2 words, hence more sustained retention, than the non-gesture learners, even after 2–6 months. Such findings point to the significance of embodied “body-specific” (hands in this case) activities for learning, and are consistent with the sensorimotor-based neural accounts of semantic representation 20 . According to the “hub-and-spoke model” 83 , 84 , “modality-specific” versus “modality-independent” (or “amodal”) representations are realized in different neural circuits, in visual/auditory/motor areas versus anterior temporal lobe, respectively. However, the outcome conceptual system must encode knowledge through integrating higher-order relationships among sensory, motor, affect, and language experiences. In this regard, one of the outstanding questions raised by Pulvermüller 84 was whether semantic learning from embodied experience and context could lead to different semantic representations in the mind and the brain. This question becomes particularly relevant when we examine the contexts of SL2 learning.

Simulated social interaction, technology, and the brain

In addition to the cognitive and neuroscience models that support SL2 theoretically, recent advances in technology have enabled us to study SL2 as a practical model toward building embodied representations in the L2 through technology-based learning. Because of the L1 vs. L2 embodied representation differences 79 , the L2 learner should aim at integrating modality-specific information with the newly acquired L2 amodal representations, in order to fully approach native-like conceptual-semantic representations. Technology-based learning could aid in this process from the earliest stages of learning, given the ample evidence from (a) technology-enhanced child language learning 85 , 86 , (b) prevalence of technology-based multimedia learning for both children and adults 36 , and (c) evidence of multimedia learning effects on the brain 37 . For example, in child language, despite a clear advantage of live learning compared to screen-based DVD learning 13 , it is now shown that direct face-to-face human interaction is not a necessary condition for infant foreign language learning. Children can benefit from technology such as Skype and other screen media platforms, provided that these technologies can deliver simulated social interactions, for example, through video chats 85 . Lytle et al. 86 showed that when the same learning materials from Kuhl et al. 13 were delivered to children through play sessions with an interactive touchscreen video, children can indeed learn from the videos. This study clearly points to both the role of interactive social play (simulated through touchscreen videos) and the impact of technology, breaking the simple dichotomy between live human learning (as effective) vs. screen-based learning (as ineffective).

In real-life learning situations, students observe and integrate multiple sources of information including actions and intentions of the speaker for using specific words in specific contexts. In a follow-up study of Jeong et al. 56 , Jeong et al. 87 examined fMRI evidence during learning (i.e., encoding), under both traditional translation and simulated social interaction conditions. The authors controlled for the amount of visual information in the two conditions by using L1 text and L1 videos as baseline comparisons. In the simulated video condition, participants had to infer the meaning of L2 target words by observing social interactions of others. Learning of L2 words in this condition resulted in additional activation in the bilateral posterior STS and right IPL. Compared with learning through L1 translation, this condition also resulted in significant positive correlations between performance scores at delayed post-test and neural activities in the right TPJ, hippocampus, and motor areas.

Jeong et al.’s new findings showed that simulated social interaction methods, compared with traditional translation/association methods, may result in stronger neural activities in key brain regions implicated for memory, perception and action, which can boost both recall and sustained long-term retention. These results are consistent with the semantic memory encoding and retrieval theories reviewed earlier. They are also consistent with recent multimedia learning effects on the brain, reflected in the bimodal encoding advantage that materials learned in multimodal conditions (e.g., learned from videos that engage both auditory and visual channels 37 ) may lead to sustained neural activities in AG, mPFC, hippocampus, posterior cingulate, and subcortical areas. These brain areas, including mPFC, TPJ, and hippocampus, significantly overlapped with the SL2 brain network and the ToM network that relies on social learning and reasoning (Fig. 2 ).

Videos or other multimedia platforms, although very effective as discussed, nevertheless have their limits with regard to social interaction and “whole-body” embodiment/engagement as in real life. Recent technological advances in immersive technologies (e.g., virtual reality, VR and augmented reality, AR) enable social interaction to a greater extent, by simulating real-world contexts and promoting student learning through active and self-exploratory discovery processes 88 . VR also provides a new platform to connect cognition, language learning, and social interaction, as it allows researchers to simulate the process of learning in its natural ecology without sacrificing experimental rigor 89 , 90 . In the current consideration, and in light of Competition Model and Embodied Cognition theories discussed, VR provides a tool for students to learn L2 in a new way. Specifically, it enables the adult learner, like the child L1 learner, to directly map (“perceptually ground”) the L2 material during learning onto objects, actions, and episodic memory to form embodied semantic representations in the L2.

Although VR has been applied to L2 teaching and learning, systematic and experimental research is still scarce in understanding the effects of VR as a function of both features of the technology and characteristics of the learner 90 . Lan et al. 91 and Hsiao et al. 92 provided early evidence in this regard. The authors trained American students to learn Mandarin Chinese vocabulary through Second Life , a popular desktop virtual platform of gaming and social networking, and demonstrated that (a) the virtual learners needed only about half of the number of exposures to gain the same level of performance as learners through traditional associative learning, and (b) virtual learners showed faster acceleration of later-stage learning. More importantly, clear individual differences in learning were observed: the low-achieving learners tended to follow a fixed route in the virtual space (using the “nearest neighbor” strategy to learn), whereas the high-achieving learners were more exploratory, grouping together similarly sounding words or similarly looking objects for learning. Interestingly, such individual difference patterns could be captured by statistical methods such as “roaming entropy” to quantify the degree or variability of movement trajectories in self-directed exploration of space, a measure previously shown to correlate with neural development during spatial navigation 93 : better learners showed higher roaming entropy, indicating more exploratory analyses of the virtual environment. Thus, navigation patterns in the VR may reflect how learners conceptually organize the environment and their abilities to explore it interactively.

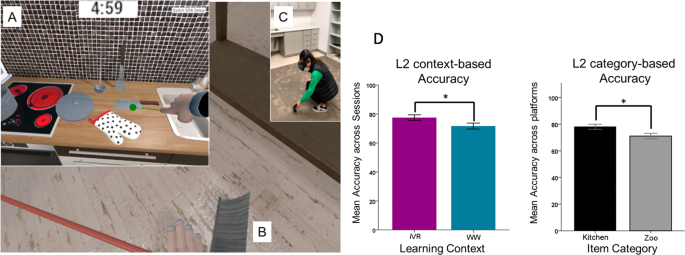

Most L2 virtual learning studies, like Lan et al. 91 , have relied on desktop virtual platforms like Second Life rather than more interactive and immersive VR (iVR). Limited evidence suggests that iVR, with its more realistic simulation of the visuospatial environment and more bodily activity and interaction, leads to higher accuracy in memory recall tasks 94 . It is likely that iVR, compared to desktop VR, more strongly engages the perceptual-motor systems and maximizes the integration of modality-specific experience, and therefore generates better embodied representation 90 . In Legault et al. 48 , participants wore head-mounted displays to view and interact with objects/animals in an iVR kitchen or zoo, and showed significantly better performance of L2 vocabulary attainment than learning through the L2-to-L1 word-to-word association method. Further, the kitchen words were learned better than the animal words, presumably because the learner could more directly manipulate the virtual objects in the kitchen (e.g., squatting and picking up a broom and moving it around; see Fig. 3 for an illustration) than they could with the virtual animals in the zoo. The iVR kitchen environment thus conferred more “whole-body” interactive experience to the learner, especially with respect to the engagement of the sensorimotor system 95 .

a In the iVR kitchen, the learner used her handset to point to any item and hear the corresponding word (e.g., “dao”, Chinese knife in the example). b The learner could pick up and move objects (broom in the example) by pressing a trigger button with index finger; ( c ) position of the learner picking up the item (broom)—the learner consented to the use of her photo here. d Left panel: Effect of learning context (iVR vs. word-word association); Right panel: effect of category of learning (iVR kitchen vs. iVR zoo). Error bars indicate 95% confidence intervals (CIs). * indicates significant effect (from Legault et al. 48 ; copyright permission from MDPI).

In terms of the SL2 framework, VR has the promise of providing a context of learning for children and adults on equal footing, and in particular, it simulates “situated learning”, a condition whereby learning takes place through real-world experiences and visuospatial analyses of the learning environment, experiences and analyses that are often absent in a typical classroom 88 . Therefore, the positive benefits of SL2 learning based on either real or simulated social interactions are clear, including at least the aforementioned aspects of (a) embodied, native-like, neural representation 56 , (b) more sustained long-term memory 49 , and (c) less susceptibility to L1 interference 24 . These benefits not only apply to foreign language learning, but also other educational contents such as spatial learning and memory 90 and learning of subjects in STEM (i.e., science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) 88 .

VR is an excellent example of the power of today’s technology-based learning, and it urges us to study how students can take advantage of rapidly developing technologies for better learning outcomes. We need to pay attention to the specific key features that support VR learning (e.g., immersive experience, spatial navigation, and user interactivity), the individual differences therein (e.g., cognitive characteristics of the learner including memory and motivation), and the underlying neurocognitive mechanisms (e.g., sensorimotor integration) that enable VR as an effective tool 90 . In this regard, the SL2 approach we advocate here will have the potential of not only benefitting students in terms of reaching native-like linguistic representation and communicative competence, but also providing specific recommendations to teachers in the classroom, especially for those struggling students who may need help in integrating multiple sources of information through contextualized learning. For example, as indicated by Legault et al. 48 , it is the struggling students (“the less successful learners”) who benefitted more from VR learning than from non-VR learning, whereas for the successful learners, VR versus non-VR learning did not make a significant difference. Consistent with the larger trend in education to promote personalized learning and active learning in STEM 96 , there is a movement for today’s classroom instructions to be structured differently from the traditional “teacher-centered” instructional methods, to encourage more “student-centered” interactions and in-depth discussions (e.g., the “flipped classroom” model). E-learning technologies including VR play a significant role in this movement.

Future directions

New exciting research in the neurocognitive mechanisms of SL2 has just begun. To understand different aspects of L2 learning from a multi-level language systems and multiple networks perspective 7 , neuroimaging studies should extend their focus from the lexico-semantic level to phonological, morphological, syntactic, and discourse levels with the SL2 approach. For example, if, as in infant L1 learning, L2 phonology can be learned through socially enriched linguistic exposure (e.g., multi-talker variability, visible articulation), then even late L2 adult learners may advance to native competence 97 . It is also important to examine how social interaction impacts the acquisition of different types of syntactic rules (e.g., cross-linguistically different syntactic features), as demonstrated in a recent fMRI study of the acquisition of possessive constructions in Japanese Sign Language 98 . The relationship between lexical versus syntactic acquisition is also a topic of significant research interest. While lexical learning typically elicits stronger involvement of the declarative system, morphosyntactic learning likely involves to a greater extent the procedural memory system 99 , 100 . How L2 lexical learning may also engage the procedural memory system in light of the SL2 brain network (Fig. 2 ) needs to be seriously considered and carefully examined in future studies.

Despite the significant effects of social L2 learning, individual differences have been observed as discussed 48 , 92 . It is therefore important to examine in greater detail both the contexts of learning and the characteristics of the learner 90 . Specifically, the magnitude of the effects might depend on the interaction between features of social learning and the learner’s cognitive and linguistic abilities. It is possible that highly interactive, embodied experiences are more helpful to some than to others 48 : learners who are poor at abstract associative learning may benefit more from social-interactive learning. A challenge to future research will be to identify the nature of the interaction between the individual learner’s inherent abilities and the richness of the social learning context.

Finally, a number of new directions present further research opportunities. For example, systematic investigation is needed for understanding the role of various types of non-verbal information that may contribute to positive L2 learning outcomes. Previous cognitive neuroscience studies have provided empirical evidence that non-verbal information (e.g. gesture, communicative intention) facilitates speech comprehension and production, as well as language learning in children and adults 49 , 101 , 102 . Furthermore, it is important to study how SL2 facilitates affective processing such as emotion and motivation 81 , 103 and consequently how it engages the brain’s limbic and subcortical reward systems. As discussed earlier, there is evidence that emotional responses are more strongly associated with L1 than L2 and social contexts may be a significant contributor to this association 80 , 81 . Indeed, social interaction has been studied as one of the most crucial contributors to the development of learning motivation in L2 acquisition 104 , 105 . The SL2 approach provides a framework for integrating previous findings and hypotheses with new insights from affective and cognitive neuroscience to fully understand the social brain of language learning.

Meltzoff, A., Kuhl, P., Movellan, J. & Sejnowski, T. Foundations for a new science of learning. Science 325 , 284–288 (2009).

CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Chomsky, N. Syntactic structures . Janua Linguarum 4 (The Hague, Mouton, 1957).

Chomsky, N. Aspects of the Theory of Syntax (MIT, Cambridge, MA, 1965).

Redcay, E. & Schilbach, L. Using second-person neuroscience to elucidate the mechanisms of social interaction. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 20 , 495–505 (2019).

Babiloni, F. & Astolfi, L. Social neuroscience and hyperscanning techniques: past, present and future. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 44 , 76–93 (2014).

PubMed Google Scholar

Hickok, G. & Poeppel, D. The cortical organization of speech processing. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 8 , 393–402 (2007).

CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Hagoort, P. The neurobiology of language beyond single-word processing. Science 366 , 55–58 (2019).

Ferstl, E. C. Neuroimaging of text comprehension: Where are we now? Ital. j. linguist. 22 , 61–88 (2010).

Google Scholar

Verga, L. & Kotz, S. A. How relevant is social interaction in second language learning? Front. Hum. Neurosci. 7 , 550 (2013).

PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Tomasello, M. The social-pragmatic theory of word learning. Pragmatics 10 (4), 401–413 (2000).

Yu, C. & Ballard, D. A unified model of early word learning: Integrating statistical and social cues. Neurocomputing 70 (13-15), 2149–2165 (2007).

Li, P., & Zhao, X. In Research Methods in Psycholinguistics and the Neurobiology of Language: A Practical Guide (eds. de Groot, A. & Hagoort, P.) 208–229 (Malden, MA: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2017).

Kuhl, P., Tsao, F. M. & Liu, H. M. Foreign-language experience in infancy: effects of short-term exposure and social interaction on phonetic learning. PNAS 100 (15), 9096–9101 (2003).

Verga, L. & Kotz, S. A. Help me if I can’t: Social interaction effects in adult contextual word learning. Cognition 168 , 76–90 (2017).

Lenneberg, E. H. Biological Foundations of Language (John Wiley & Sons, New York, 1967).

Bates, E., & MacWhinney, B. In Mechanisms of Language Acquisition (ed. MacWhinney, B.) 157–194 (Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1987).

MacWhinney, B. The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition (eds. Gass, S. & Mackey, A.) 211–227 (New York: Routledge, 2012).

Li, P., & MacWhinney, B. In The Encyclopedia of Applied Linguistics (ed. Chapelle, C. A.) 1–5 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Malden, MA, 2013).

Hernandez, A., Li, P. & MacWhinney, B. The emergence of competing modules in bilingualism. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9 , 220–5 (2005).

Hernandez, A. & Li, P. Age of acquisition: its neural and computational mechanisms. Psychol. Bull. 133 (4), 638–650 (2007).

Johnson, J. S. & Newport, E. L. Critical period effects in second language learning: the influence of maturational state on the acquisition of English as a second language. Cogn. Psychol. 21 , 60–99 (1989).

Zhao, X. & Li, P. Bilingual lexical interactions in an unsupervised neural network model. IJB 13 , 505–524 (2010).

Kroll, J. F. & Stewart, E. Category interference in translation and picture naming: evidence for asymmetric connections between bilingual memory representations. J. Mem. Lang. 33 , 149–174 (1994).

Linck, J., Kroll, J. & Sunderman, G. Losing access to the native language while immersed in a second language: Evidence for the role of inhibition in second-language learning. Psychol. Sci. 20 (12), 1507–1515 (2009).

DeLuca, V., Rothman, J., Bialystok, E. & Pliatsikas, C. Redefining bilingualism as a spectrum of experiences that differentially affects brain structure and function. PNAS 116 (15), 7565–7574 (2019).

Grosjean, F. In The Psycholinguistics of Bilingualism (eds. Grosjean, F. & Li, P.) 5–25 (Wiley & Sons, Inc., Malden, MA, 2013).

Li, P. In The Handbook of Language Emergence (eds. MacWhinney, B., & O’Grady, W.) 511–536 (John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Maiden, MA, 2015).

Lantolf, J. Sociocultural theory and L2: State of the art. Stud. Second Lang. Acquis. 28 , 67–109 (2006).

Tomasello, M. Constructing a Language: A Usage-based Theory of Language Acquisition (Harvard University Press, Cambridge, 2003).

Hall, J. K. The contributions of conversation analysis and interactional linguistics to a usagebased understanding of language: expanding the transdisciplinary framework. Mod. Lang. J. 103 , 80–94 (2019).

Ellis, N. C. Essentials of a theory of language cognition. Mod. Lang. J. 103 , 39–60 (2019).

Tulving, E. & Thomson, D. M. Encoding specificity and retrieval processes in episodic memory. Psychol. Rev. 80 (5), 352–373 (1973).

Godden, G. & Baddeley, A. Context-dependent memory in two natural environments: on land and underwater. Br. J. Psychol. 6 , 355–369 (1975).

Craik, F. I. & Lockhart, R. S. Levels of processing: a framework for memory research. J. Verbal Learning Verbal Behav. 11 (6), 671–684 (1972).

Paivio, A. Mental Representations: A Dual Coding Approach . (Oxford University Press, Oxford, 1990).

Mayer, R. E., Moreno, R., Boire, M. & Vagge, S. Maximizing constructivist learning from multimedia communications by minimizing cognitive load. J. Educ. Psychol. 91 (4), 638–643 (1999).

Liu, C., Wang, R., Li, L., Ding, G., Yang, J. & Li, P. Effects of encoding modes on memory of naturalistic events. J. Neurolinguist. 53 , 100863 (2020).

Marian, V. & Kaushanskaya, M. in Relations Between Language and Memory : Sabest Saarbrucker Beitrage zur Sprach- und Transl (ed. Zelinsky-Wibbelt, C.) 95–120 (Frankfrut, Peter Lang, 2011).

Marian, V. & Neisser, U. Language-dependent recall of autobiographical memories. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 129 (3), 361–368 (2000).

Marian, V. & Kaushanskaya, M. Language context guides memory content. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 14 (5), 925–933 (2007).

Barsalou, L. W., Niedenthal, P. M., Barbey, A. K. & Ruppert, J. A. In The Psychology of Learning and Motivation: Advances in Research and Theory (ed. Ross, B. H.) 43–92 (Elsevier Science, 2003).

Glenberg, A. M., Sato, M. & Cattaneo, L. Use-induced motor plasticity affects the processing of abstract and concrete language. Curr. Biol. 18 , R290–R291 (2008).

Chomsky, N. Lectures on Government and Binding (Foris Publications, Dordrecht, Holland, & Cinnaminson, NJ, 1981).

Fodor, J. A. The Modularity of Mind (MIT Press, Cambridge, MA, 1983).

Barsalou, L. W. In Embodied Grounding: Social, Cognitive, Affective, and Neuroscientific Approaches (eds. Semin, G. R. & Smith, E. R.) 9–42 (Cambridge University Press, 2008).

Aziz-Zadeh, L. & Damasio, A. Embodied semantics for actions: findings from functional brain imaging. J. Physiol. Paris 102 (1-3), 35–9 (2008).

Willems, R. M. & Casasanto, D. Flexibility in embodied language understanding. Front. Psychol. 2 , 116 (2011).

Legault, J. et al. Immersive virtual reality as an effective tool for second language vocabulary learning. Languages 4 (1), 13 (2019).

Mayer, K. M., Yildiz, I. B., Macedonia, M. & von Kriegstein, K. Visual and motor cortices differentially support the translation of foreign language words. Curr. Biol. 25 (4), 530–535 (2015).

Li, P., Legault, J. & Litcofsky, K. A. Neuroplasticity as a function of second language learning: anatomical changes in the human brain. Cortex 58 , 301–24 (2014).

Grant, A. M., Fang, S.-Y. Y. & Li, P. Second language lexical development and cognitive control: a longitudinal fMRI study. Brain Lang. 144 , 35–47 (2015).

Qi, Z., Han, M., Garel, K., Chen, E. & Gabrieli, J. White-matter structure in the right hemisphere predicts Mandarin Chinese learning success. J. Neurolinguist. 33 , 14–28 (2015).

Yang, J., Gates, K., Molenaar, P. & Li, P. Neural changes underlying successful second language word learning: An fMRI study. J. Neurolinguist. 33 , 29–49 (2015).

Breitenstein, C. et al. Hippocampus activity differentiates good from poor learners of a novel lexicon. NeuroImage 25 (3), 958–968 (2005).

Tagarelli, K., Shattuck, K., Turkeltaub, P. & Ullman, M. Language learning in the adult brain: a neuroanatomical meta-analysis of lexical and grammatical learning. NeuroImage 193 , 178–200 (2019).

Jeong, H. et al. Learning second language vocabulary: neural dissociation of situation-based learning and text-based learning. NeuroImage 50 (2), 802–9 (2010).

Legault, J., Fang, S., Lan, Y. & Li, P. Structural brain changes as a function of second language vocabulary training: Effects of learning context. Brain Cogn. 134 , 90–102 (2019).

Stein, M., Winkler, C., Kaiser, A. & Dierks, T. Structural brain changes related to bilingualism: does immersion make a difference? Front. Psychol. 5 , 1116 (2014).

Verga, L. & Kotz, S. A. Spatial attention underpins social word learning in the right fronto-parietal network. NeuroImage 195 , 165–173 (2019).

Thompson-Schill, S. Neuroimaging studies of semantic memory: inferring “how” from “where”. Neuropsychologia 41 (3), 280–292 (2003).

Bressler, S. & Menon, V. Large-scale brain networks in cognition: emerging methods and principles. Trends Cogn. Sci. 14 (6), 277–290 (2010).

Bassett, D. & Sporns, O. Network neuroscience. Nat. Neurosci. 20 (3), 353–364 (2017).

Li, P. & Grant, A. Second language learning success revealed by brain networks. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 19 , 657–664 (2016).

Hagoort, P. On Broca, brain, and binding: a new framework. Trends Cogn. Sci. 9 (9), 416–423 (2005).

Abutalebi, J. & Green, D. Bilingual language production: the neurocognition of language representation and control. J. Neurolinguist. 20 (3), 242–275 (2007).

Nichols, E. S. & Joanisse, M. F. Functional activity and white matter microstructure reveal the independent effects of age of acquisition and proficiency on second-language learning. NeuroImage 143 , 15–25 (2016).

Sun, X., Li, L., Ding, G., Wang, R. & Li, P. Effects of language proficiency on cognitive control: Evidence from resting-state functional connectivity. Neuropsychologia 129 , 263–275 (2019).

Noordzij, M. L. et al. Brain mechanisms underlying human communication. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 3 , 14 (2009).

Redcay, E. et al. Live face-to-face interaction during fMRI: a new tool for social cognitive neuroscience. NeuroImage 50 (4), 1639–47 (2010).

Hagoort, P. & Indefrey, P. The neurobiology of language beyond single words. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 37 (1), 347–362 (2014).

Frith, C. & Frith, U. Social cognition in humans. Curr. Biol. 17 (16), R724–R732 (2007).

Adolphs, R. The social brain: neural basis of social knowledge. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 60 , 693–716 (2009).

Ferstl, E. C., Neumann, J., Bogler, C. & von Cramon, D. Y. The extended language network: a meta-analysis of neuroimaging studies on text comprehension. Hum. Brain. Mapp. 29 (5), 581–93 (2008).

Mason, R. & Just, M. The role of the theory-of-mind cortical network in the comprehension of narratives. Lang. Linguist. Compass 3 , 157–174 (2009).

Li, P. & Clariana, R. B. Reading comprehension in L1 and L2: An integrative approach. J. Neurolinguist. 50 , 94–105 (2019).

Peñaloza, C., Grasemann, U., Dekhtyar, M., Miikkulainen, R. & Kiran, S. BiLex: a computational approach to the effects of age of acquisition and language exposure on bilingual lexical access. Brain Lang ., in press, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bandl.2019.104643 (2020).

Zhao, X. & Li, P. Simulating cross-language priming with a dynamic computational model of the lexicon. Biling.: Lang. Cogn. 16 , 288–303 (2013).

Li, P. Lexical organization and competition in first and second languages: computational and neural mechanisms. Cogn. Sci. 33 , 629–664 (2009).

Zhang, X., Yang, J., Wang, R. & Li, P. A neuroimaging study of semantic representation in first and second languages. Lang. Cogn. Neurosci . In press, https://doi.org/10.1080/23273798.2020.1738509 (2020).

Caldwell-Harris, C. L. Emotionality differences between a native and foreign language: implications for everyday life. Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 24 , 214–219 (2015).

Pavlenko, A. Affective processing in bilingual speakers: disembodied cognition? Int. J. Psychol. 47 , 405–428 (2012).

Ivaz, L., Costa, A. & Dunabeitia, J. The emotional impact of being myself: emotions and foreign-language processing. J. Exp. Psychol. Learn. Mem. Cogn. 42 , 489–496 (2016).

Lambon Ralph, M. A., Jefferies, E., Patterson, K. & Rogers, T. The neural and computational bases of semantic cognition. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 18 (1), 42–55 (2017).

Pulvermüller, F. How neurons make meaning: brain mechanisms for embodied and abstract-symbolic semantics. Trends Cogn. Sci. 17 (9), 458–470 (2013).

Myers, L., LeWitt, R., Gallo, R. & Maselli, N. Baby FaceTime: Can toddlers learn from online video chat? Dev. Sci. 20 , e12430 (2017).

Lytle, S., Garcia-Sierra, A. & Kuhl, P. Two are better than one: Infant language learning from video improves in the presence of peers. PNAS 115 (40), 9859–9866 (2018).

Jeong, H., Li, P., Suzuki, W., Sugiura, M. & Kawashima, R. Neural mechanisms of language learning from social contexts, Manuscript under review (2020).

Dede, C. Immersive interfaces for engagement and learning. Science 323 (5910), 66–69 (2009).

Peeters, D. Virtual reality: a game-changing method for the language sciences. Psychon. Bull. Rev. 26 (3), 894–900 (2019).

Li, P., Legault, J., Klippel, A. & Zhao, J. Virtual reality for student learning: understanding individual differences. Hum. Behav. Brain 1 , 28–36 (2020).

Lan, Y. J., Fang, S. Y., Legault, J. & Li, P. Second language acquisition of Mandarin Chinese vocabulary: context of learning effects. Educ. Technol. Res. Dev. 63 (5), 671–690 (2015).

Hsiao, I. Y. T., Lan, Y. J., Kao, C. L. & Li, P. Visualization analytics for second language vocabulary learning in virtual worlds. J. Educ. Techno. Soc. 20 (2), 161–175 (2017).

Freund, J. et al. Emergence of individuality in genetically identical mice. Science 340 , 756–759 (2013).

Krokos, E., Catherine, P. & Amitabh, V. Virtual memory palaces: immersion aids recall. Virtual Real. 23 , 1–15 (2019).

Johnson-Glenberg, M. C., Birchfield, D. A., Tolentino, L. & Koziupa, T. Collaborative embodied learning in mixed reality motion-capture environments: two science studies. J. Educ. Psychol. 106 (1), 86–104 (2014).

Nature Editorial. STEM education: to build a scientist. Nature 523 (7560), 371–373 (2015).

Zhang, Y. et al. Neural signatures of phonetic learning in adulthood: a magnetoencephalography study. Neuroimage 46 , 226–240 (2009).

Yusa, N., Kim, J., Koizumi, M., Sugiura, M. & Kawashima, R. Social interaction affects neural outcomes of sign language learning as a foreign language in adults. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 11 , 115, https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2017.00115 (2017).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Ullman, M. T. The neuronal basis of lexicon and grammar in first and second language: The declarative/procedural model. Biling. Lang. Cogn. 4 (1), 105–122 (2001).

Ullman, M. T. & Lovelett, J. T. Implications of the declarative/procedural model for improving second language learning: The role of memory enhancement techniques. Second Lang. Res. 34 (1), 39–65 (2018).

Goldin-Meadow, S. & Alibali, M. W. Gesture’s role in speaking, learning, and creating language. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 64 , 257–283 (2013).

Ozyurek, A. In Oxford Handbook of Psycholinguistics (eds. Rueschemeyer, S.A. & Gaskell, M.G.) 592–607 (Oxford University Press, 2018).

Ripollés, P. et al. The role of reward in word learning and its implications for language acquisition. Curr. Biol. CB 24 (21), 2606–11 (2014).

Dörnyei, Z. In Individual Differences and Instructed Language Learning (ed. Robinson, P.) 137–158 (John Benjamins, 2002).

MacIntyre, P. D. & Legatto, J. J. A dynamic system approach to willingness to communicate: Developing an idiodynamic method to capture rapidly changing affect. Appl. Linguist. 32 (2), 149–171 (2011).

Download references

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank the generous support to the research reported in this article by the US National Science Foundation’s Integrative Neural and Cognitive Systems (NCS) program (NCS-1533625; BCS-1633817) and by a Faculty Startup Fund from the Hong Kong Polytechnic University to PL and the MEXT KAKENHI Grant of Japan (#18K00776) to HJ. We thank Peter Hagoort for his helpful comments on an earlier version of this article.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Chinese and Bilingual Studies, Faculty of Humanities, The Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Kowloon, Hong Kong, China

Graduate School of International Cultural Studies & Department of Human Brain Science, Institute of Development, Aging, and Cancer, Tohoku University, Aoba-ku, Sendai, Japan

Hyeonjeong Jeong

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

P.L. and H.J. conceptualized the article. P.L. provided the overall framework of the article, and P.L. and H.J. both reviewed the literature and wrote the article.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ping Li .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons license, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons license and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Li, P., Jeong, H. The social brain of language: grounding second language learning in social interaction. npj Sci. Learn. 5 , 8 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-020-0068-7

Download citation

Received : 17 December 2019

Accepted : 29 May 2020

Published : 19 June 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-020-0068-7

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Brain gray matter morphometry relates to onset age of bilingualism and theory of mind in young and older adults.

- Xiaoqian Li

- Kwun Kei Ng

- W. Quin Yow

Scientific Reports (2024)

Knee flexion of saxophone players anticipates tonal context of music

- Nádia Moura

npj Science of Learning (2023)

Psychological Impact of Languages on the Human Mind: Research on the Contribution of Psycholinguistics Approach to Teaching and Learning English

Journal of Psycholinguistic Research (2023)

RETRACTED ARTICLE: IoT Based Multimodal Social Interaction Activity Framework for the Physical Education System

- Liang Zhuang

- Ching-Hsien Hsu

- Priyan Malarvizhi Kumar

Wireless Personal Communications (2022)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Center for Applied Second Language Studies

Burning Questions: Second Language Research

Language teaching is as much an art as it is a science. Effective teachers excel at the art of language teaching, and we at CASLS understand the science behind second language research. With help from practicing teachers, we identified and answered teachers’ top burning questions about language learning.

Show All Answers

What proficiency level do high school students achieve?

The majority of students studying a world language in a traditional high school program reach benchmark level 3 in reading by the fourth year of study, regardless of the target language.

Students typically reach benchmark level 4 in writing and speaking by the fourth year of study. Interestingly, the data suggest that students progress faster in speaking and writing than in reading. Download the full report. Hide

Does block or traditional scheduling affect success in language programs?

Since the 1980s, teachers have debated the benefits of organizing class time according to different types of schedules.

Many schools have replaced the traditional schedule, in which classes meet forty to fifty-five minutes each school day, with a block schedule, in which classes meet for twice as long every other school day. Our data shows that students do equally well in either scheduling format after two years of instruction. Download the full report. Hide

Do early language programs improve high school proficiency?

Teachers often hear that beginning language study early will help students become more proficient, and many schools now offer early language programs.

Does it matter whether students start language study in elementary or middle school? Our data shows that students who begin in elementary school are about 70% more likely to reach basic communication levels by high school. Students who begin in middle school are about 50% more likely. Download the full report. Hide

How many hours of instruction do students need to reach Intermediate-high proficiency?

Teachers, administrators, and parents often underestimate the amount of time students need to reach Intermediate proficiency and can be disappointed in learning outcomes later.

How many hours of instruction do students need? Our data shows that only 15% of students reach Intermediate-mid proficiency after approximately 720 hours of study, which is about four years in a typical high school program. Download the full report. Hide

What motivates students to study world languages?

We know it’s important for students to take extended sequences of world language classes to become proficient, but many students just want to get the requirements over with as soon as possible.

How can we inspire students to continue studying world languages? Motivating students is a challenge for teachers of all subjects, and a complete answer would take a book (or two). Our study shows that one factor, high levels of language proficiency, correlates strongly with students’ desire to continue studying language. Successful learners were eleven times more likely to want to continue, which would lead to even greater mastery. Download the the full report. Hide

How do proficiency levels compare between K-12 and university students?

High school students with three years of study have approximately the same proficiency levels as university students with one year of study.

Eighth grade students with 540 hours of instruction have had about as much class time as third-year high school students. Students’ productive skills are often slightly higher than their reading scores. Most students in U.S. programs do not reach proficiency levels that allow them to effectively communicate in the language. Download the the full report. Hide

How do heritage students perform on proficiency tests?

Heritage students show higher levels of language proficiency in all skills, but the difference is strongest in productive skills.

Heritage students have markedly higher speaking and writing scores than those of non-heritage students, particularly in the early years of high school language programs. By the fourth year, non-heritage students are catching up. The progress of heritage students is slower overall, probably because most high school programs do not challenge these students to reach high levels of proficiency. Download the full report. Hide

What factors are important for an effective K-8 program?

Teachers understand that it’s better to start teaching world languages in elementary school, and many parents are beginning to ask for elementary language programs. But what kind of program would be best?

In terms of bang for the buck, immersion programs lead to the highest proficiency levels. For non-immersion programs, such as FLES, the two key factors for effective programs are time and intensity. Language programs that meet several times each week during the whole school year and continue for multiple years are generally the most effective. Download the full report. Hide

What levels of proficiency do immersion students achieve?

Virtually all students enrolled at a young age in immersion programs succeed in reaching the ACTFL Intermediate proficiency levels by the end of high school.

At these levels, students successfully handle everyday communicative tasks in the target language. In traditional four-year high school language programs, less than half the students completing the program reach these proficiency levels. Download the full report. Hide

- Even more »

Account Options

- Try the new Google Books

- Advanced Book Search

Get this book in print

- Springer Shop

- Barnes&Noble.com

- Books-A-Million

- Find in a library

- All sellers »

Selected pages

Other editions - View all

Common terms and phrases, about the author (2022).

Dr Christine Coombe is an Associate Professor of General Studies at Dubai Men’s College, Higher Colleges of Technology in the UAE. She served as President of the TESOL International Association from 2011 to 2012. Christine has authored/edited over 50 books on different aspects of English language teaching, learning and assessment. Throughout her career she has received several awards including the 2018 James E Alatis Award for exemplary service to TESOL. In 2017 she was named to TESOL’s 50@50 list which honored 50 top professionals who have made an impact on ELT in the past 50 years.

Bibliographic information

Language Learning Strategies

- First Online: 13 January 2022

Cite this chapter

- Mirosław Pawlak 3 , 4

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

403 Accesses

1 Citations

Language learning strategies (LLS), or “actions chosen by learners for the purpose of language learning” ( Griffiths, 2018 ) have been the object of empirical inquiry for over four decades since specialists identified their adept use as one of the characteristics of good language learners (e.g., Rubin, 1975 ).

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Cohen, A. D. (2011). Strategies in learning and using a second language. Routledge.

Google Scholar

Cohen, A. D., & Griffiths, C. (2015). Revisiting LLS research 40 years later. TESOL Quarterly, 53 , 414–429.

Article Google Scholar

Dörnyei, Z. (2005). The psychology of the language learner: Individual factors in second language acquisition . Lawrence Erlbaum.

Dörnyei, Z., & Ryan, S. (2015). The psychology of the language learner revisited . Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Ehrman, M., Leaver, B., & Oxford, R. L. (2003). A brief overview of individual differences in second language learning. System, 31 , 313–330.

Grenfell, M., & Macaro, E. (2007). Claims and critiques. In A. D. Cohen & E. Macaro (Eds.), Language learner strategies: Thirty years of research and practice (pp. 9–28). Oxford University Press.

Griffiths, C. (2018). The strategy factor in successful language learning: The tornado effect . Multilingual Matters.

Griffiths, C., & Oxford, R. L. (2014). The twenty-first century landscape of language learning strategies: Introduction to this special issue. System, 43 , 1–10.

Larsen-Freeman, D., & Cameron, L. (2008). Complex dynamic systems and applied linguistics . Oxford University Press.

McDonough, S. (1999). Learner strategies. Language Teaching, 32 , 1–18.

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know . Heinle & Heinle.

Oxford, R. L. (2011). Teaching and researching language learning strategies. Pearson Education.

Oxford, R. L. (2017). Teaching and researching language learning strategies. Self-regulation in context . Routledge.

Pawlak, M. (2011). Research into language learning strategies: Taking stock and looking ahead’. In J. Arabski & A. Wojtaszek (Eds.), Individual differences in SLA (pp. 17–37). Multilingual Matters.

Pawlak, M. (2021). Investigating language learning strategies: Prospects pitfalls and challenges. Language Teaching Research 25 (5), 817–835.

Pawlak, M., & Oxford, R. L. (2018). Conclusion: The future of research into language learning strategies. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 8 , 523–532.

Plonsky, L. (2011). Systematic review article: The effectiveness of second language strategy instruction: A meta-analysis. Language Learning, 61 , 993–1038.

Rubin, J. (1975). What the “good language learner” can teach us. TESOL Quarterly, 9 , 41–51.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Faculty of Pedagogy and Fine Arts, Adam Mickiewicz University, Kalisz, Poland

Mirosław Pawlak

State University of Applied Sciences in Konin, Konin, Poland

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mirosław Pawlak .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European Knowledge Development Institute, Ankara, Türkiye

Hassan Mohebbi

Higher Colleges of Technology (HCT), Dubai Men’s College, Dubai, United Arab Emirates

Christine Coombe

The Research Questions

What are patterns of LLS use in less studied domains (e.g., grammar, pronunciation, culture)?

How do learners use LLS in technology-enhanced environments?

How do learners use LLS in content-based language instruction (e.g. study abroad)?

How do senior learners employ LLS when learning different skills and subsystems?

How is the use of LLS for learning skills and subsystems mediated by other variables and clusters of such variables (e.g., beliefs, boredom, willingness to communicate)?

How do learners use LLS in different kinds of learning tasks (e.g., meaning and form-oriented)?

How does LLS use change over time (e.g., over a longer period, in a given lesson)?

How is the use of LLS related to attainment in terms of explicit and implicit knowledge?

What are the best ways to teach LLS in different contexts?

What are the best tools to tap into LLS use, both in general and in specific tasks?

Suggested Resources

Cohen, A. D. (2014) . Strategies in learning and using a second language. London and New York: Routledge .

The book is a substantially revised version of a previous publication. It comprises eight chapters in which the author attempts to disentangle the definitional and terminological confusion which surrounds the concept of strategies for learning and using a second language, and overviews methods used in LLS research, issues involved in strategies-based instruction as well as the empirical evidence for such pedagogic intervention. Importantly, Andrew Cohen also considers the use of strategies for choosing the language of thought and for dealing with assessment. The volume is invaluable reading not only for researchers and teacher educators, but also for teachers who are interested in fostering strategic learning, and undergraduate and graduate students working on their theses.

Cohen, A. D., & Macaro, E. (Eds.). (2007). Language learner strategies: Thirty years of research and practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press .

This edited collection constitutes an early attempt to confront theoretical issues in the study of LLS and to synthesize existing empirical evidence based on thirty years of research. It brings together 12 chapters by leading scholars in the field which are divided into two parts. Part One, Issues, theories, and frameworks , addresses claims and critiques aimed at LLS, surveys opinions of experts in this domain, and zooms in on such issues as the psychological and sociolinguistic perspectives on LLS, factors influencing strategy use, the research methods that can be applied in the study of strategies, grammar as a neglected facet of LLS research, and the question of strategies-based instruction. Part Two, Reviewing thirty years of empirical LLS research , summarizes the main results of studies that have focused on strategies related to listening, reading, vocabulary, writing and communication. The book closes with a chapter by the editors who consider key issues in light of the book contents and provide a research agenda for the field.

Griffiths, C. (2018). The strategy factor in successful language learning: The tornado effect. Bristol: Multilingual Matters .