0800 118 2892

- +44 (0)203 151 1280

Teen Cocaine Addiction Case Study: Chloe's Story

This case study of drug addiction can affect anyone – it doesn’t discriminate on the basis of age, gender or background. At Serenity Addiction Centres, our drug detox clinic is open to everyone, and our friendly and welcoming approach is changing the way rehab clinics are helping clients recover from addiction.

We’ve asked former Serenity client, Chloe, to share her experience of drug rehab with Serenity Addiction Centre’s assistance.

Chloe’s Addiction

If you met Chloe today, you would never know about her past. This born and bred London girl is 20 years old, and a flourishing law student with a bright future in the City.

A few years ago though, it seemed as if this straight A student was about to throw away her life, thanks to a class A drug addiction .

Chloe had a great childhood. By her own admission, school was a breeze for her, with strong academic achievement and social skills making her as successful on the playground as she was in the classroom.

Age 7, Chloe started at a boarding school, and loved having friends around her all the time. With no parents about, Chloe and her friends found themselves invited to house parties. As soon as I could convince people they we 18, they moved on to London’s nightclubs.

It was here where Chloe first came across drugs, and it was a slippery slope to cocaine addiction. She explains: “At 15, I was taking poppers, graduated to MDMA at 16, and then I tried cocaine at our year 13 parties. I got separated from my friends, and found them taking cocaine in a back room. I didn’t want to be left out, so I tried it.”

Chloe scored straight As in her A levels, and accepted a place at Kings College London to study law. She was introduced to new people, and it seemed that cocaine was available at every place they went. Parties, clubs, and even her new friends were all good sources of a line of cocaine. As a self confessed wild child by this point, Chloe didn’t want to miss out.

The demands of a law degree were high, but so was Chloe’s desire for more cocaine.

Going out almost every night to snort coke, she started to wonder if she was becoming an addict. She spent every penny of the generous allowance from her parents. Chloe spent every penny available on credit cards, and even took on a £2000 bank loan to support her habit.

Chloe estimated that at one point, her addiction had saddled her with more than £13,000 of debt.

Coming out of Addiction Denial

Chloe’s light bulb moment finally came when her best friend, who she shared a flat with, sat her down and asked why they were drifting apart.

Chloe realised that cocaine had become more important to her than her friends, family, and studies. It had to stop. Chloe found the details for Serenity Addiction Centres, and called the same day to ask for help with her addiction.

One thing Chloe particularly appreciated about Serenity Addiction Centres was the flexible approach of the counsellors . They got to know Chloe, listening to her worries, and working out a non-residential rehab plan for her. This allowed her to continue with her studies.

Chloe’s treatment was organised at a clinic not far from her university, allowing her to keep her studies on track, and keeping her life as normal as possible.

Chloe says: “Talking about how I was using cocaine, along with contributing problems from earlier in my life, were a massive help. I didn’t want to be known just as a party girl”.

“If I’d not found Serenity Addiction Centres, there would probably have been a long wait for NHS treatment. Serenity Addiction Centres got the right treatment. Everything was organised with privacy and discretion. I only shared what was happening with my flatmate.”

This level of discretion was really helpful, and the rapid results of her treatment meant that after just three months Chloe felt able to tell her parents what had been happening.

Life after rehab

It’s amazing that Chloe has now had nearly a year where not taken cocaine, and faced her debts by working part time to repay what she owes. Even better, thanks to Serenity’s fast intervention. Chloe is on course for a 2:1 in her law degree.

If you’re ready to detox? Serenity Addiction Centre’s addiction support team are here to help you find the rehab programme which works for you. Serenity can help you beat your addiction. Gaining control over drugs, allowing you to move on and take back control of your life.

This Drug Addiction Case Study is here so others may identify. Contact us today , and begin your detox journey with Serenity Addiction Centres.

FREE CONSULTATION

Get a no-obligation confidential advice from our medical experts today

Request a call back

We provide a healthy environment uniquely suited to support your growth and healing.

- Rehab Clinic - Serenity Rehabilitation LTD. Arquen House,4-6 Spicer Street, St Albans, Hertfordshire AL3 4PQ

- 0800 118 2892 +44(0)203 151 1280

- Testimonials

- Case Studies

Popular Pages

- Alcohol Addiction

- How To Home Detox From Alcohol

- Alcohol Rehab Centres

- Methadone addiction

Top Locations

- Leicestershire

Module 9: Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

Case studies: substance-abuse disorders, learning objectives.

- Identify substance abuse disorders in case studies

Case Study: Benny

The following story comes from Benny, a 28-year-old living in the Metro Detroit area, USA. Read through the interview as he recounts his experiences dealing with addiction and recovery.

Q : How long have you been in recovery?

Benny : I have been in recovery for nine years. My sobriety date is April 21, 2010.

Q: What can you tell us about the last months/years of your drinking before you gave up?

Benny : To sum it up, it was a living hell. Every day I would wake up and promise myself I would not drink that day and by the evening I was intoxicated once again. I was a hardcore drug user and excessively taking ADHD medication such as Adderall, Vyvance, and Ritalin. I would abuse pills throughout the day and take sedatives at night, whether it was alcohol or a benzodiazepine. During the last month of my drinking, I was detached from reality, friends, and family, but also myself. I was isolated in my dark, cold, dorm room and suffered from extreme paranoia for weeks. I gave up going to school and the only person I was in contact with was my drug dealer.

Q : What was the final straw that led you to get sober?

Benny : I had been to drug rehab before and always relapsed afterwards. There were many situations that I can consider the final straw that led me to sobriety. However, the most notable was on an overcast, chilly October day. I was on an Adderall bender. I didn’t rest or sleep for five days. One morning I took a handful of Adderall in an effort to take the pain of addiction away. I knew it wouldn’t, but I was seeking any sort of relief. The damage this dosage caused to my brain led to a drug-induced psychosis. I was having small hallucinations here and there from the chemicals and a lack of sleep, but this time was different. I was in my own reality and my heart was racing. I had an awful reaction. The hallucinations got so real and my heart rate was beyond thumping. That day I ended up in the psych ward with very little recollection of how I ended up there. I had never been so afraid in my life. I could have died and that was enough for me to want to change.

Q : How was it for you in the early days? What was most difficult?

Benny : I had a different experience than most do in early sobriety. I was stuck in a drug-induced psychosis for the first four months of sobriety. My life was consumed by Alcoholics Anonymous meetings every day and sometimes two a day. I found guidance, friendship, and strength through these meetings. To say early sobriety was fun and easy would be a lie. However, I did learn it was possible to live a life without the use of drugs and alcohol. I also learned how to have fun once again. The most difficult part about early sobriety was dealing with my emotions. Since I started using drugs and alcohol that is what I used to deal with my emotions. If I was happy I used, if I was sad I used, if I was anxious I used, and if I couldn’t handle a situation I used. Now that the drinking and drugs were out of my life, I had to find new ways to cope with my emotions. It was also very hard leaving my old friends in the past.

Q : What reaction did you get from family and friends when you started getting sober?

Benny : My family and close friends were very supportive of me while getting sober. Everyone close to me knew I had a problem and were more than grateful when I started recovery. At first they were very skeptical because of my history of relapsing after treatment. But once they realized I was serious this time around, I received nothing but loving support from everyone close to me. My mother was especially helpful as she stopped enabling my behavior and sought help through Alcoholics Anonymous. I have amazing relationships with everyone close to me in my life today.

Q : Have you ever experienced a relapse?

Benny : I experienced many relapses before actually surrendering. I was constantly in trouble as a teenager and tried quitting many times on my own. This always resulted in me going back to the drugs or alcohol. My first experience with trying to become sober, I was 15 years old. I failed and did not get sober until I was 19. Each time I relapsed my addiction got worse and worse. Each time I gave away my sobriety, the alcohol refunded my misery.

Q : How long did it take for things to start to calm down for you emotionally and physically?

Benny : Getting over the physical pain was less of a challenge. It only lasted a few weeks. The emotional pain took a long time to heal from. It wasn’t until at least six months into my sobriety that my emotions calmed down. I was so used to being numb all the time that when I was confronted by my emotions, I often freaked out and didn’t know how to handle it. However, after working through the 12 steps of AA, I quickly learned how to deal with my emotions without the aid of drugs or alcohol.

Q : How hard was it getting used to socializing sober?

Benny : It was very hard in the beginning. I had very low self-esteem and had an extremely hard time looking anyone in the eyes. But after practice, building up my self-esteem and going to AA meetings, I quickly learned how to socialize. I have always been a social person, so after building some confidence I had no issue at all. I went back to school right after I left drug rehab and got a degree in communications. Upon taking many communication classes, I became very comfortable socializing in any situation.

Q : Was there anything surprising that you learned about yourself when you stopped drinking?

Benny : There are surprises all the time. At first it was simple things, such as the ability to make people smile. Simple gifts in life such as cracking a joke to make someone laugh when they are having a bad day. I was surprised at the fact that people actually liked me when I wasn’t intoxicated. I used to think people only liked being around me because I was the life of the party or someone they could go to and score drugs from. But after gaining experience in sobriety, I learned that people actually enjoyed my company and I wasn’t the “prick” I thought I was. The most surprising thing I learned about myself is that I can do anything as long as I am sober and I have sufficient reason to do it.

Q : How did your life change?

Benny : I could write a book to fully answer this question. My life is 100 times different than it was nine years ago. I went from being a lonely drug addict with virtually no goals, no aspirations, no friends, and no family to a productive member of society. When I was using drugs, I honestly didn’t think I would make it past the age of 21. Now, I am 28, working a dream job sharing my experience to inspire others, and constantly growing. Nine years ago I was a hopeless, miserable human being. Now, I consider myself an inspiration to others who are struggling with addiction.

Q : What are the main benefits that emerged for you from getting sober?

Benny : There are so many benefits of being sober. The most important one is the fact that no matter what happens, I am experiencing everything with a clear mind. I live every day to the fullest and understand that every day I am sober is a miracle. The benefits of sobriety are endless. People respect me today and can count on me today. I grew up in sobriety and learned a level of maturity that I would have never experienced while using. I don’t have to rely on anyone or anything to make me happy. One of the greatest benefits from sobriety is that I no longer live in fear.

Case Study: Lorrie

Figure 1. Lorrie.

Lorrie Wiley grew up in a neighborhood on the west side of Baltimore, surrounded by family and friends struggling with drug issues. She started using marijuana and “popping pills” at the age of 13, and within the following decade, someone introduced her to cocaine and heroin. She lived with family and occasional boyfriends, and as she puts it, “I had no real home or belongings of my own.”

Before the age of 30, she was trying to survive as a heroin addict. She roamed from job to job, using whatever money she made to buy drugs. She occasionally tried support groups, but they did not work for her. By the time she was in her mid-forties, she was severely depressed and felt trapped and hopeless. “I was really tired.” About that time, she fell in love with a man who also struggled with drugs.

They both knew they needed help, but weren’t sure what to do. Her boyfriend was a military veteran so he courageously sought help with the VA. It was a stroke of luck that then connected Lorrie to friends who showed her an ad in the city paper, highlighting a research study at the National Institute of Drug Abuse (NIDA), part of the National Institutes of Health (NIH.) Lorrie made the call, visited the treatment intake center adjacent to the Johns Hopkins Bayview Medical Center, and qualified for the study.

“On the first day, they gave me some medication. I went home and did what addicts do—I tried to find a bag of heroin. I took it, but felt no effect.” The medication had stopped her from feeling it. “I thought—well that was a waste of money.” Lorrie says she has never taken another drug since. Drug treatment, of course is not quite that simple, but for Lorrie, the medication helped her resist drugs during a nine-month treatment cycle that included weekly counseling as well as small cash incentives for clean urine samples.

To help with heroin cravings, every day Lorrie was given the medication buprenorphine in addition to a new drug. The experimental part of the study was to test if a medication called clonidine, sometimes prescribed to help withdrawal symptoms, would also help prevent stress-induced relapse. Half of the patients received daily buprenorphine plus daily clonidine, and half received daily buprenorphine plus a daily placebo. To this day, Lorrie does not know which one she received, but she is deeply grateful that her involvement in the study worked for her.

The study results? Clonidine worked as the NIDA investigators had hoped.

“Before I was clean, I was so uncertain of myself and I was always depressed about things. Now I am confident in life, I speak my opinion, and I am productive. I cry tears of joy, not tears of sadness,” she says. Lorrie is now eight years drug free. And her boyfriend? His treatment at the VA was also effective, and they are now married. “I now feel joy at little things, like spending time with my husband or my niece, or I look around and see that I have my own apartment, my own car, even my own pots and pans. Sounds silly, but I never thought that would be possible. I feel so happy and so blessed, thanks to the wonderful research team at NIDA.”

- Liquor store. Authored by : Fletcher6. Located at : https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Bunghole_Liquor_Store.jpg . License : CC BY-SA: Attribution-ShareAlike

- Benny Story. Provided by : Living Sober. Located at : https://livingsober.org.nz/sober-story-benny/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

- One patientu2019s story: NIDA clinical trials bring a new life to a woman struggling with opioid addiction. Provided by : NIH. Located at : https://www.drugabuse.gov/drug-topics/treatment/one-patients-story-nida-clinical-trials-bring-new-life-to-woman-struggling-opioid-addiction . License : Public Domain: No Known Copyright

Change Password

Your password must have 6 characters or more:.

- a lower case character,

- an upper case character,

- a special character

Password Changed Successfully

Your password has been changed

Create your account

Forget yout password.

Enter your email address below and we will send you the reset instructions

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to reset your password

Forgot your Username?

Enter your email address below and we will send you your username

If the address matches an existing account you will receive an email with instructions to retrieve your username

- April 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 4 CURRENT ISSUE pp.255-346

- March 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 3 pp.171-254

- February 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 2 pp.83-170

- January 01, 2024 | VOL. 181, NO. 1 pp.1-82

The American Psychiatric Association (APA) has updated its Privacy Policy and Terms of Use , including with new information specifically addressed to individuals in the European Economic Area. As described in the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, this website utilizes cookies, including for the purpose of offering an optimal online experience and services tailored to your preferences.

Please read the entire Privacy Policy and Terms of Use. By closing this message, browsing this website, continuing the navigation, or otherwise continuing to use the APA's websites, you confirm that you understand and accept the terms of the Privacy Policy and Terms of Use, including the utilization of cookies.

Substance Use Disorders and Addiction: Mechanisms, Trends, and Treatment Implications

- Ned H. Kalin , M.D.

Search for more papers by this author

The numbers for substance use disorders are large, and we need to pay attention to them. Data from the 2018 National Survey on Drug Use and Health ( 1 ) suggest that, over the preceding year, 20.3 million people age 12 or older had substance use disorders, and 14.8 million of these cases were attributed to alcohol. When considering other substances, the report estimated that 4.4 million individuals had a marijuana use disorder and that 2 million people suffered from an opiate use disorder. It is well known that stress is associated with an increase in the use of alcohol and other substances, and this is particularly relevant today in relation to the chronic uncertainty and distress associated with the COVID-19 pandemic along with the traumatic effects of racism and social injustice. In part related to stress, substance use disorders are highly comorbid with other psychiatric illnesses: 9.2 million adults were estimated to have a 1-year prevalence of both a mental illness and at least one substance use disorder. Although they may not necessarily meet criteria for a substance use disorder, it is well known that psychiatric patients have increased usage of alcohol, cigarettes, and other illicit substances. As an example, the survey estimated that over the preceding month, 37.2% of individuals with serious mental illnesses were cigarette smokers, compared with 16.3% of individuals without mental illnesses. Substance use frequently accompanies suicide and suicide attempts, and substance use disorders are associated with a long-term increased risk of suicide.

Addiction is the key process that underlies substance use disorders, and research using animal models and humans has revealed important insights into the neural circuits and molecules that mediate addiction. More specifically, research has shed light onto mechanisms underlying the critical components of addiction and relapse: reinforcement and reward, tolerance, withdrawal, negative affect, craving, and stress sensitization. In addition, clinical research has been instrumental in developing an evidence base for the use of pharmacological agents in the treatment of substance use disorders, which, in combination with psychosocial approaches, can provide effective treatments. However, despite the existence of therapeutic tools, relapse is common, and substance use disorders remain grossly undertreated. For example, whether at an inpatient hospital treatment facility or at a drug or alcohol rehabilitation program, it was estimated that only 11% of individuals needing treatment for substance use received appropriate care in 2018. Additionally, it is worth emphasizing that current practice frequently does not effectively integrate dual diagnosis treatment approaches, which is important because psychiatric and substance use disorders are highly comorbid. The barriers to receiving treatment are numerous and directly interact with existing health care inequities. It is imperative that as a field we overcome the obstacles to treatment, including the lack of resources at the individual level, a dearth of trained providers and appropriate treatment facilities, racial biases, and the marked stigmatization that is focused on individuals with addictions.

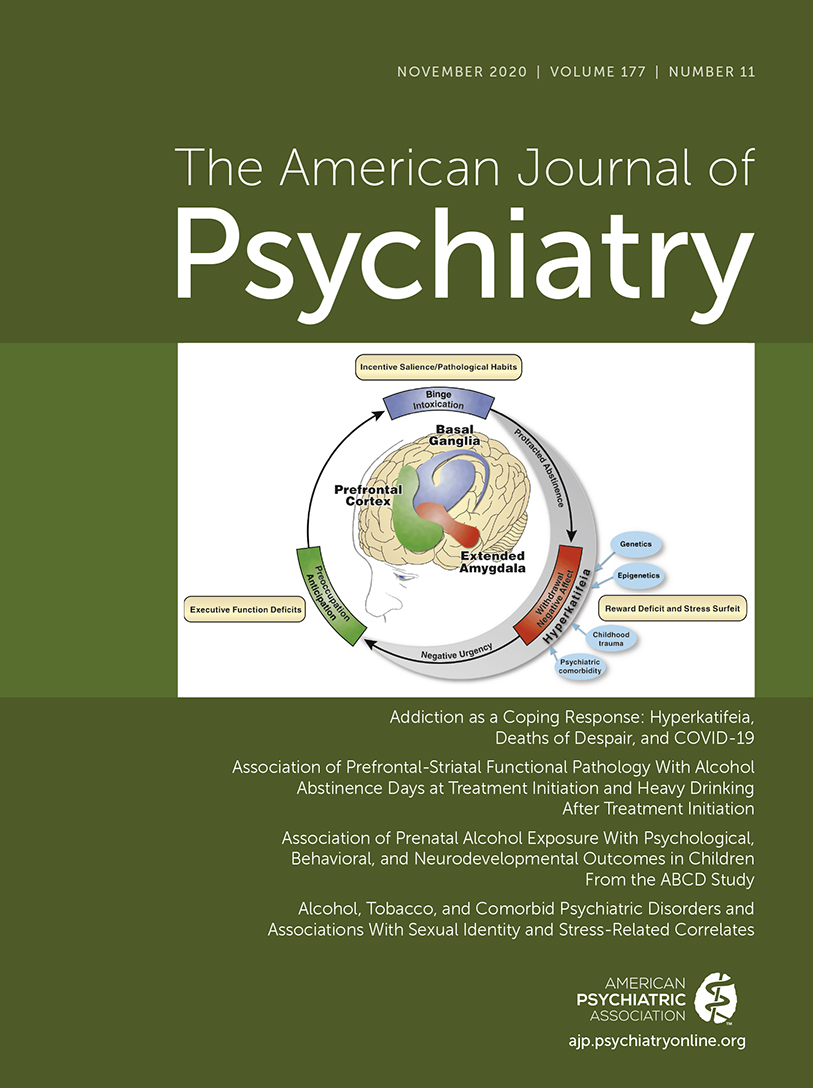

This issue of the Journal is focused on understanding factors contributing to substance use disorders and their comorbidity with psychiatric disorders, the effects of prenatal alcohol use on preadolescents, and brain mechanisms that are associated with addiction and relapse. An important theme that emerges from this issue is the necessity for understanding maladaptive substance use and its treatment in relation to health care inequities. This highlights the imperative to focus resources and treatment efforts on underprivileged and marginalized populations. The centerpiece of this issue is an overview on addiction written by Dr. George Koob, the director of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), and coauthors Drs. Patricia Powell (NIAAA deputy director) and Aaron White ( 2 ). This outstanding article will serve as a foundational knowledge base for those interested in understanding the complex factors that mediate drug addiction. Of particular interest to the practice of psychiatry is the emphasis on the negative affect state “hyperkatifeia” as a major driver of addictive behavior and relapse. This places the dysphoria and psychological distress that are associated with prolonged withdrawal at the heart of treatment and underscores the importance of treating not only maladaptive drug-related behaviors but also the prolonged dysphoria and negative affect associated with addiction. It also speaks to why it is crucial to concurrently treat psychiatric comorbidities that commonly accompany substance use disorders.

Insights Into Mechanisms Related to Cocaine Addiction Using a Novel Imaging Method for Dopamine Neurons

Cassidy et al. ( 3 ) introduce a relatively new imaging technique that allows for an estimation of dopamine integrity and function in the substantia nigra, the site of origin of dopamine neurons that project to the striatum. Capitalizing on the high levels of neuromelanin that are found in substantia nigra dopamine neurons and the interaction between neuromelanin and intracellular iron, this MRI technique, termed neuromelanin-sensitive MRI (NM-MRI), shows promise in studying the involvement of substantia nigra dopamine neurons in neurodegenerative diseases and psychiatric illnesses. The authors used this technique to assess dopamine function in active cocaine users with the aim of exploring the hypothesis that cocaine use disorder is associated with blunted presynaptic striatal dopamine function that would be reflected in decreased “integrity” of the substantia nigra dopamine system. Surprisingly, NM-MRI revealed evidence for increased dopamine in the substantia nigra of individuals using cocaine. The authors suggest that this finding, in conjunction with prior work suggesting a blunted dopamine response, points to the possibility that cocaine use is associated with an altered intracellular distribution of dopamine. Specifically, the idea is that dopamine is shifted from being concentrated in releasable, functional vesicles at the synapse to a nonreleasable cytosolic pool. In addition to providing an intriguing alternative hypothesis underlying the cocaine-related alterations observed in substantia nigra dopamine function, this article highlights an innovative imaging method that can be used in further investigations involving the role of substantia nigra dopamine systems in neuropsychiatric disorders. Dr. Charles Bradberry, chief of the Preclinical Pharmacology Section at the National Institute on Drug Abuse, contributes an editorial that further explains the use of NM-MRI and discusses the theoretical implications of these unexpected findings in relation to cocaine use ( 4 ).

Treatment Implications of Understanding Brain Function During Early Abstinence in Patients With Alcohol Use Disorder

Developing a better understanding of the neural processes that are associated with substance use disorders is critical for conceptualizing improved treatment approaches. Blaine et al. ( 5 ) present neuroimaging data collected during early abstinence in patients with alcohol use disorder and link these data to relapses occurring during treatment. Of note, the findings from this study dovetail with the neural circuit schema Koob et al. provide in this issue’s overview on addiction ( 2 ). The first study in the Blaine et al. article uses 44 patients and 43 control subjects to demonstrate that patients with alcohol use disorder have a blunted neural response to the presentation of stress- and alcohol-related cues. This blunting was observed mainly in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex, a key prefrontal regulatory region, as well as in subcortical regions associated with reward processing, specifically the ventral striatum. Importantly, this finding was replicated in a second study in which 69 patients were studied in relation to their length of abstinence prior to treatment and treatment outcomes. The results demonstrated that individuals with the shortest abstinence times had greater alterations in neural responses to stress and alcohol cues. The authors also found that an individual’s length of abstinence prior to treatment, independent of the number of days of abstinence, was a predictor of relapse and that the magnitude of an individual’s neural alterations predicted the amount of heavy drinking occurring early in treatment. Although relapse is an all too common outcome in patients with substance use disorders, this study highlights an approach that has the potential to refine and develop new treatments that are based on addiction- and abstinence-related brain changes. In her thoughtful editorial, Dr. Edith Sullivan from Stanford University comments on the details of the study, the value of studying patients during early abstinence, and the implications of these findings for new treatment development ( 6 ).

Relatively Low Amounts of Alcohol Intake During Pregnancy Are Associated With Subtle Neurodevelopmental Effects in Preadolescent Offspring

Excessive substance use not only affects the user and their immediate family but also has transgenerational effects that can be mediated in utero. Lees et al. ( 7 ) present data suggesting that even the consumption of relatively low amounts of alcohol by expectant mothers can affect brain development, cognition, and emotion in their offspring. The researchers used data from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study, a large national community-based study, which allowed them to assess brain structure and function as well as behavioral, cognitive, and psychological outcomes in 9,719 preadolescents. The mothers of 2,518 of the subjects in this study reported some alcohol use during pregnancy, albeit at relatively low levels (0 to 80 drinks throughout pregnancy). Interestingly, and opposite of that expected in relation to data from individuals with fetal alcohol spectrum disorders, increases in brain volume and surface area were found in offspring of mothers who consumed the relatively low amounts of alcohol. Notably, any prenatal alcohol exposure was associated with small but significant increases in psychological problems that included increases in separation anxiety disorder and oppositional defiant disorder. Additionally, a dose-response effect was found for internalizing psychopathology, somatic complaints, and attentional deficits. While subtle, these findings point to neurodevelopmental alterations that may be mediated by even small amounts of prenatal alcohol consumption. Drs. Clare McCormack and Catherine Monk from Columbia University contribute an editorial that provides an in-depth assessment of these findings in relation to other studies, including those assessing severe deficits in individuals with fetal alcohol syndrome ( 8 ). McCormack and Monk emphasize that the behavioral and psychological effects reported in the Lees et al. article would not be clinically meaningful. However, it is feasible that the influences of these low amounts of alcohol could interact with other predisposing factors that might lead to more substantial negative outcomes.

Increased Comorbidity Between Substance Use and Psychiatric Disorders in Sexual Identity Minorities

There is no question that victims of societal marginalization experience disproportionate adversity and stress. Evans-Polce et al. ( 9 ) focus on this concern in relation to individuals who identify as sexual minorities by comparing their incidence of comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders with that of individuals who identify as heterosexual. By using 2012−2013 data from 36,309 participants in the National Epidemiologic Study on Alcohol and Related Conditions–III, the authors examine the incidence of comorbid alcohol and tobacco use disorders with anxiety, mood disorders, and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The findings demonstrate increased incidences of substance use and psychiatric disorders in individuals who identified as bisexual or as gay or lesbian compared with those who identified as heterosexual. For example, a fourfold increase in the prevalence of PTSD was found in bisexual individuals compared with heterosexual individuals. In addition, the authors found an increased prevalence of substance use and psychiatric comorbidities in individuals who identified as bisexual and as gay or lesbian compared with individuals who identified as heterosexual. This was most prominent in women who identified as bisexual. For example, of the bisexual women who had an alcohol use disorder, 60.5% also had a psychiatric comorbidity, compared with 44.6% of heterosexual women. Additionally, the amount of reported sexual orientation discrimination and number of lifetime stressful events were associated with a greater likelihood of having comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders. These findings are important but not surprising, as sexual minority individuals have a history of increased early-life trauma and throughout their lives may experience the painful and unwarranted consequences of bias and denigration. Nonetheless, these findings underscore the strong negative societal impacts experienced by minority groups and should sensitize providers to the additional needs of these individuals.

Trends in Nicotine Use and Dependence From 2001–2002 to 2012–2013

Although considerable efforts over earlier years have curbed the use of tobacco and nicotine, the use of these substances continues to be a significant public health problem. As noted above, individuals with psychiatric disorders are particularly vulnerable. Grant et al. ( 10 ) use data from the National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions collected from a very large cohort to characterize trends in nicotine use and dependence over time. Results from their analysis support the so-called hardening hypothesis, which posits that although intervention-related reductions in nicotine use may have occurred over time, the impact of these interventions is less potent in individuals with more severe addictive behavior (i.e., nicotine dependence). When adjusted for sociodemographic factors, the results demonstrated a small but significant increase in nicotine use from 2001–2002 to 2012–2013. However, a much greater increase in nicotine dependence (46.1% to 52%) was observed over this time frame in individuals who had used nicotine during the preceding 12 months. The increases in nicotine use and dependence were associated with factors related to socioeconomic status, such as lower income and lower educational attainment. The authors interpret these findings as evidence for the hardening hypothesis, suggesting that despite the impression that nicotine use has plateaued, there is a growing number of highly dependent nicotine users who would benefit from nicotine dependence intervention programs. Dr. Kathleen Brady, from the Medical University of South Carolina, provides an editorial ( 11 ) that reviews the consequences of tobacco use and the history of the public measures that were initially taken to combat its use. Importantly, her editorial emphasizes the need to address health care inequity issues that affect individuals of lower socioeconomic status by devoting resources to develop and deploy effective smoking cessation interventions for at-risk and underresourced populations.

Conclusions

Maladaptive substance use and substance use disorders are highly prevalent and are among the most significant public health problems. Substance use is commonly comorbid with psychiatric disorders, and treatment efforts need to concurrently address both. The papers in this issue highlight new findings that are directly relevant to understanding, treating, and developing policies to better serve those afflicted with addictions. While treatments exist, the need for more effective treatments is clear, especially those focused on decreasing relapse rates. The negative affective state, hyperkatifeia, that accompanies longer-term abstinence is an important treatment target that should be emphasized in current practice as well as in new treatment development. In addition to developing a better understanding of the neurobiology of addictions and abstinence, it is necessary to ensure that there is equitable access to currently available treatments and treatment programs. Additional resources must be allocated to this cause. This depends on the recognition that health care inequities and societal barriers are major contributors to the continued high prevalence of substance use disorders, the individual suffering they inflict, and the huge toll that they incur at a societal level.

Disclosures of Editors’ financial relationships appear in the April 2020 issue of the Journal .

1 US Department of Health and Human Services: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Center for Behavioral Health Statistics and Quality: National Survey on Drug Use and Health 2018. Rockville, Md, SAMHSA, 2019 ( https://www.samhsa.gov/data/nsduh/reports-detailed-tables-2018-NSDUH ) Google Scholar

2 Koob GF, Powell P, White A : Addiction as a coping response: hyperkatifeia, deaths of despair, and COVID-19 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1031–1037 Link , Google Scholar

3 Cassidy CM, Carpenter KM, Konova AB, et al. : Evidence for dopamine abnormalities in the substantia nigra in cocaine addiction revealed by neuromelanin-sensitive MRI . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1038–1047 Link , Google Scholar

4 Bradberry CW : Neuromelanin MRI: dark substance shines a light on dopamine dysfunction and cocaine use (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1019–1021 Abstract , Google Scholar

5 Blaine SK, Wemm S, Fogelman N, et al. : Association of prefrontal-striatal functional pathology with alcohol abstinence days at treatment initiation and heavy drinking after treatment initiation . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1048–1059 Abstract , Google Scholar

6 Sullivan EV : Why timing matters in alcohol use disorder recovery (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1022–1024 Abstract , Google Scholar

7 Lees B, Mewton L, Jacobus J, et al. : Association of prenatal alcohol exposure with psychological, behavioral, and neurodevelopmental outcomes in children from the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development Study . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1060–1072 Link , Google Scholar

8 McCormack C, Monk C : Considering prenatal alcohol exposure in a developmental origins of health and disease framework (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1025–1028 Abstract , Google Scholar

9 Evans-Polce RJ, Kcomt L, Veliz PT, et al. : Alcohol, tobacco, and comorbid psychiatric disorders and associations with sexual identity and stress-related correlates . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1073–1081 Abstract , Google Scholar

10 Grant BF, Shmulewitz D, Compton WM : Nicotine use and DSM-IV nicotine dependence in the United States, 2001–2002 and 2012–2013 . Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1082–1090 Link , Google Scholar

11 Brady KT : Social determinants of health and smoking cessation: a challenge (editorial). Am J Psychiatry 2020 ; 177:1029–1030 Abstract , Google Scholar

- Cited by None

- Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders

- Addiction Psychiatry

- Transgender (LGBT) Issues

March 1, 2017

Case Study: When Chronic Pain Leads to a Dangerous Addiction

How did an educated, elderly engineer wind up with a heroin habit?

By Daniel Barron

It was 4 P.M., and Andrew

* had just bought 10 bags of heroin. In his kitchen, he tugged one credit-card-sized bag from the rubber-banded bundle and laid it on the counter with sacramental reverence. Pain shot through his body as he pulled a cutting board from the cabinet. Slowly, deliberately, he tapped the bag's white contents onto the board and crushed it with the flat edge of a butter knife, forming a line of fine white powder. He snorted it in one pass and shuffled back to his armchair. It was bitter, but snorting heroin was safer than injecting, and he was desperate: his prescription pain medication was gone.

I met Andrew the next day in the emergency room, where he told me about the previous day's act of desperation. I admitted him to control his swelling legs and joint pain. He was also detoxing from opioids.

On supporting science journalism

If you're enjoying this article, consider supporting our award-winning journalism by subscribing . By purchasing a subscription you are helping to ensure the future of impactful stories about the discoveries and ideas shaping our world today.

Andrew looked older than his 69 years. His face was wrinkled with exhaustion. A frayed, tangled mop of grizzled hair fell to his shoulders. Andrew had been a satellite network engineer, first for the military, more recently for a major telecommunications company. An articulate, soft-spoken fellow, he summed up his (rather impressive) career modestly: “Well, I'd just find where a problem was and then find a way to fix it.”

Yet there was one problem he couldn't fix. “Doctor, I'm always in the most terrible pain,” he said, with closed eyes. “I had no other options. I started using heroin, bought it from my neighbor to help with the pain. I'm scared stiff.”

For two decades Andrew had suffered serial joint failures from a combination of arthritis, obesity and other factors. Each began as an achy pain and ended in a joint replacement. His right shoulder was the first to go, followed by both hips, a knee and an ankle. Pain always ensued. The new joints kept getting infected: more surgery, more pain. To make things worse, a bathtub mishap broke his right femur. That led to an operation to insert a full-length titanium rod. A perfect storm of complications had left Andrew barely able to hobble around the small apartment he shared with his adult son. (Andrew's wife had left him shortly after he broke his femur, and his son took him in.) Pain became Andrew's all-consuming nemesis, devouring most of his waking hours.

Andrew was first prescribed an opioid after one of his many surgeries. This was in the late 1990s, around the time when prescriptions for these painkillers began to take off nationally. His doctor began him on Vicodin, a commonly used opioid that combines hydrocodone with acetaminophen (Tylenol).

Pain, like vision, touch or taste, is a sensory signal. The brain has an elaborate network of receptors, neurons and centers dedicated to pain. Opioids exert their effects by binding to mu-opioid receptors, which are densely concentrated in brain regions that regulate pain perception and reward. Activating mu receptors blocks pain signals in the spinal cord and the response to this signal in the brain. Mu receptors also cause the release of dopamine in reward pathways, which is why opioids cause both analgesia and euphoria.

Surgery after surgery, opioids became Andrew's vitamins, as vital to his pain control as blood pressure drugs are for hypertension. Yet in 2005 Andrew noticed he was feeling anxious about his pill supply. “You start out with a bottle of 30 pills, then there's only 20, then only 10. It's scary when you run out.”

Credit: Chris Gash

Months after his surgeries, after his scars were healed, he still struggled with deep, biting pain. It had spread throughout his body and required more pills to tame. Andrew had transitioned from what is called acute pain (pain from his surgical wounds) to chronic pain (pain in the absence of an obvious cause). He had also developed a tolerance to the opioids. On a cellular level, this means that his neurons expressed fewer mu receptors, so he needed to flood his system with higher doses to get the same effect as before. (Andrew, ever the engineer, appreciated the irony of wrangling yet another network, this time with drugs.)

Possibly, the opioids had contributed to Andrew's spreading pain. Some patients on these drugs have been known to develop increased pain sensitivity known as opioid-induced hyperalgesia.

From Prescription Meds to Street Drugs

As his tolerance for opioids grew, Andrew found that even 15 milligrams of oxycodone no longer worked for him. After he relocated to his son's apartment, he no longer had a primary care provider familiar with his history and could not refill his medications.

With nowhere to turn, Andrew mentioned his situation to his neighbor, who sold him diverted opioids—prescription medications hawked on the street. When these ran out, his neighbor sold him heroin. Andrew's dependence on heroin terrified him, and at $100 a day, it threatened to bankrupt him as well.

This trajectory is by no means unusual, according to Andrew's lead doctor, William Becker, an addiction medicine specialist and assistant professor at the Yale School of Medicine: “Chronic pain is the new initiation to heroin. We're finding that it's older and older patients, who start on the path to chronic pain, then on to opioids, then on to heroin.” Andrew's case is a “classic example,” he said. “The numbers are controversial, but as tens of millions of people taking opioids for pain age, we think 10 percent and maybe more will develop at least a mild opioid use disorder. And their pain isn't going away. We have to become more fluent in managing the co-occurrence of chronic pain and addiction.”

His words and recent warnings from U.S. surgeon general Vivek H. Murthy about the “urgent health crisis” caused by our lax approach to opioids now come to mind every time I consider writing a prescription for one of these painkillers. I also think of Andrew standing at his kitchen counter, hands trembling as he forms a line of heroin.

Relief and Release

Luckily for Andrew, Becker runs the Opioid Reassessment Clinic, which is pioneering strategies to taper patients with chronic pain from high-dose opioid use to Suboxone, a clever sublingual tablet that combines buprenorphine and naloxone. Buprenorphine activates the mu-opioid receptor. When taken under the tongue, it provides pain relief and prevents withdrawal. Naloxone is added as a safeguard to keep abusers from injecting the drug. When taken sublingually, naloxone has no effect. When injected, it blocks the mu receptor and causes acute withdrawal, a physiological inducement to use Suboxone in the prescribed manner.

At a dollar a day, Suboxone is affordable. In combination with intensive psychosocial therapy, it is a safe and highly efficacious treatment for opioid use disorders. And, as Andrew attested, it actually controls pain better than heroin. Instead of being strung out on heroin, Suboxone allowed Andrew to meaningfully interact with our medical team. He undertook a program of proved therapies for chronic pain that included physical therapy, mindfulness training and psychosocial therapy. Andrew left the hospital after nearly three weeks with a clear plan: weekly check-ins at Becker's Suboxone clinic and continued physical and psychosocial therapy tailored for pain. The last time I saw him in his hospital room, he was excited at the prospects: “The plan is to continue with Suboxone and to stay with it. And hopefully I won't have any more surgeries. It's been a rough decade, a long haul, but I'm making slow progress.”

Andrew will be managing pain and addiction for the rest of his life, but now he has a variety of tools for doing so that are safe, legal and effective.

Daniel Barron is director of the Pain Intervention and Digital Research Program, a National Institutes of Health–funded research clinic devoted to developing better tools to define chronic pain and psychiatric conditions, at Brigham and Women's Hospital and Spaulding Rehabilitation Hospital. He completed his medical training and psychiatry residency at Yale University, his graduate work at the University of Texas and his fellowship in interventional pain medicine at the University of Washington. He is author of Reading Our Minds: The Rise of Big Data Psychiatry . Follow him on X (formerly Twitter) @daniel__barron or visit his website at danielsbarron.com

- Open Access

- By Publication (A-Z)

- Case Reports

- Publication Ethics

- Publishing Policies

- Editorial Policies

- Submit Manuscript

- About Graphy

New to Graphy Publications? Create an account to get started today.

Registered Users

Have an account? Sign in now.

- Full-Text HTML

- Full-Text PDF

- About This Journal

- Aims & Scope

- Editorial Board

- Editorial Process

- Author Guidelines

- Special Issues

- Articles in Press

Jo-Hanna Ivers 1* and Kevin Ducray 2

In October 2012, 83 front-line Irish service providers working in the addiction treatment field received accreditation as trained practitioners in the delivery of a number of evidence-based positive reinforcement approaches that address substance use: 52 received accreditation in the Community Reinforcement Approach (CRA), 19 in the Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (ACRA) and 12 in Community Reinforcement and Family Training (CRAFT). This case study presents the treatment of a 17-year-old white male engaging in high-risk substance use. He presented for treatment as part of a court order. Treatment of the substance use involved 20 treatment sessions and was conducted per Adolescent Community Reinforcement Approach (A-CRA). This was a pilot of A-CRA a promising treatment approach adapted from the United States that had never been tried in an Irish context. A post-treatment assessment at 12-week follow-up revealed significant improvements. At both assessment and following treatment, clinician severity ratings on the Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP) and the Alcohol Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) found decreased score for substance use was the most clinically relevant and suggests that he had made significant changes. Also his MAP scores for parental conflict and drug dealing suggest that he had made significant changes in the relevant domains of personal and social functioning as well as in diminished engagement in criminal behaviour. Results from this case study were quite promising and suggested that A-CRA was culturally sensitive and applicable in an Irish context.

1. Theoretical and Research Basis for Treatment

Substance use disorders (SUDs) are distinct conditions characterized by recurrent maladaptive use of psychoactive substances associated with significant distress. These disorders are highly common with lifetime rates of substance use or dependence estimated at over 30% for alcohol and over 10% for other substances [1 , 2] . Changing substance use patterns and evolving psychosocial and pharmacologic treatments modalities have necessitated the need to substantiate both the efficacy and cost effectiveness of these interventions.

Evidence for the clinical application of cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) for substance use disorders has grown significantly [3 - 8] . Moreover, CBT for substance use disorders has demonstrated efficacy both as a monotherapy and as part of combination treatment [7] . CBT is a time-limited, problem-focused, intervention that seeks to reduce emotional distress through the modification of maladaptive beliefs, assumptions, attitudes, and behaviours [9] . The underlying assumption of CBT is that learning processes play an imperative function in the development and maintenance of substance misuse. These same learning processes can be used to help patients modify and reduce their drug use [3] .

Drug misuse is viewed by CBT practitioners as learned behaviours acquired through experience [10] . If an individual uses alcohol or a substance to elicit (positively or negatively reinforced) desired states (e.g. euphorigenic, soothing, calming, tension reducing) on a recurrent basis, it may become the preferred way of achieving those effects, particularly in the absence of alternative ways of attaining those desired results. A primary task of treatment for problem substance users is to (1) identify the specific needs that alcohol and substances are being used to meet and (2) develop and reinforce skills that provide alternative ways of meeting those needs [10 , 11] .

CRA is a broad-spectrum cognitive behavioural programme for treating substance use and related problems by identifying the specific needs that alcohol and or other substances are satisfying or meeting. The goal is then to develop and reinforce skills that provide alternative ways of meeting those needs. Consistent with traditional CBT, CRA through exploration, allows the patient to identify negative thoughts, behaviours and beliefs that maintain addiction. By getting the patient to identify, positive non-drug using behaviours, interests, and activities, CRA attempts to provide alternatives to drug use. As therapy progresses the objective is to prevent relapse, increase wellness, and develop skills to promote and sustain well-being. The ultimate aim of CRA, as with CBT is to assist the patient to master a specific set of skills necessary to achieve their goals. Treatment is not complete until those skills are mastered and a reasonable degree of progress has been made toward attaining identified therapy goals. CRA sessions are highly collaborative, requiring the patient to engage in ‘between session tasks’ or homework designed reinforce learning, improve coping skills and enhance self efficacy in relevant domains.

The use of the Community Reinforcement Approach is empirically supported with inpatients [12 , 13] , outpatients [14 - 16] and homeless populations (Smith et al., 1998). In addition, three recent metaanalytic reviews cited CRA as one of the most cost-effective treatment programmes currently available [17 , 18] .

A-CRA is a evidenced based behavioural intervention that is an adapted version of the adult CRA programme [19] . Garner et al [19] modified several of the CRA procedures and accompanying treatment resources to make them more developmentally appropriate for adolescents. The main distinguishing aspect of A-CRA is that it involves caregivers—namely parents or guardians who are ultimately responsible for the adolescent and with whom the adolescent is living.

A-CRA has been tested and found effective in the context of outpatient continuing care following residential treatment [20 - 22] and without the caregiver components as an intervention for drug using, homeless adolescents [23] . More recently, Garner et al [19] collected data from 399 adolescents who participated in one of four randomly controlled trials of the A-CRA intervention, the purpose of which was to examine the extent to which exposure to A-CRA procedures mediated the relationship between treatment retention and outcomes. The authors found adolescents who were exposed to 12 or more A-CRA procedures were significantly more likely to be in recovery at follow-up.

Combining A-CRA with relapse prevention strategies receives strong support as an evidence based, best practice model and is widely employed in addiction treatment programmes. Providing a CBT-ACRA therapeutic approach is imperative as it develops alternative ways of meeting needs and thus altering dependence.

2. Case Introduction

Alan is a 17 year-old male currently living in County Dublin. Alan presented to the agency involuntarily and as a requisite of his Juvenile Liaison Officer who was seeing him on foot of prior drugs arrest for ‘possession with intent to supply’; a more serious charge than a simple ‘drugs possession’ charge. As Alan had no previous charges he was placed on probation for one year. This was Alan’s first contact with the treatment services. A diagnostic assessment was completed upon entry to treatment and included completion of a battery of instruments comprising the Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP), The World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST) and the Beck Youth Inventory (BYI) (see appendices for full description of outcome measures) (Table 1).

3. Diagnostic Criteria

The apparent symptoms of substance dependency were: (1) Loss of Control - Alan had made several attempts at controlling the amounts of cannabis he consumed, but those times when he was able to abstain from cannabis use were when he substituted alcohol and/or other drugs. (2) Family History of Alcohol/Drug Usage - Alan’s eldest sister who is now 23 years old is in recovery from opiate abuse. She was a chronic heroin user during her early adult years [17 - 21] . During this period, which corresponds to Alan’s early adolescent years [12 - 15] she lived in the family home (3) Changes in Tolerance - Alan began per day. At presentation he was smoking six to eight cannabis joints daily through the week, and eight to twelve joints daily on weekends.

4. Psychosocial, Medical and Family History

At time of intake Alan was living with both of his parents and a sister, two years his senior, in the family home. Alan was the youngest and the only boy in his family. He had two other older sisters, 5 and 7 years his senior. He was enrolled in his 5th year of secondary school but at the time of assessment was expelled from all classes. Alan had superior sporting abilities. He played for the junior team of a first division football team and had the prospect of a professional career in football. He reported a family history positive for substance use disorders. An older sister was in recovery for opiate dependence. Apart from his substance use Alan reported no significant psychological difficulties or medical problems. His motives for substance use were cited as boredom, curiosity, peer pressure, and pleasure seeking. His triggers for use were relationship difficulties at home, boredom and peer pressure. Pre-morbid personality traits included thrill seeking and impulsivity (Table 2).

5. Case Conceptualisation

A CBT case formulation is based on the cognitive model, which hypothesizes that "a person’s feelings and emotions are influenced by their perception of events" . It is not the actual event that determines how the person feels, but rather how they construe the event (Beck, 1995 p14). Moreover, cognitive theory posits that the “child learns to construe reality through his or her early experiences with the environment, especially with significant others” and that “sometimes these early experiences lead children to accept attitudes and beliefs that will later prove maladaptive” [24] . A CBT formulation (or case conceptualisation) is one of the key underpinnings of Cognitive Behavioural Therapy (CBT). It is the ‘blueprint’ which aids the therapist to understand and explain the patient’s’ problems.

Formulation driven CBT enables the therapist to develop an individualised understanding of the patient and can help to predict the difficulties that a patient may encounter during therapy. In Alan’s case, exploring his existing negative automatic thoughts about regarding school and his academic competences highlighted the difficulties he could experience with CBT homework completion. Whilst Alan was good at between session therapy assignments, an exploration of what is meant by ‘homework’ in a CBT context was crucial.

A collaborative CBT formulation was done diagrammatically together with Alan (Figure 1). This formulation aimed to describe his presenting problems and using CBT theory, to explore explanatory inferences about the initiating and maintaining factors of his drug use which could practically inform meaningful interventions.

Simmons and Griffiths et al. make the insightful observation that particular group differences need to be specifically considered and suggest that the therapist should be cognizant of the role of both society and culture when developing a formulation. They firstly suggest that the impact played by gender, sexuality and socio-cultural roles in the genesis of a psychological disorder, namely the contribution that being a member of a group may have on predisposing and precipitating factors, be carefully considered. An example they offer is the role of poverty on the development of psychological problems, such as the link evidenced between socio economic group and onset of schizophrenia. This was clearly evident in the case of Alan, who being a member of a deprived socioeconomic group, growing up and living in an area with a high level of economic deprivation, perceived that his choices for success were limited. His thinking, as an adolescent boy, was dichotomous in that he saw himself as having only two fixed and limited choices (a) being good at sport he either pursue a career as a professional sportsman or alternatively (b) he engage in crime and work his way up through the ranks as a ‘career criminal’. Simmons & Griffiths secondly suggest that being a member of a particular group can heavily influence a person’s understanding of the causality of their psychological disorder. A third consideration when developing a formulation is the degree to which being a member of a particular group may influence the acceptance or rejection of a member experiencing a psychological illness. Again this is pertinent in Alan’s case as he was part of a sub-group, a gang engaged in crime. For this cohort, crime and drug use were synonymous. Using drugs was viewed as a rite of passage for Alan.

Drug use, according to CBT models, are socially learned behaviours initiated, maintained and altered through the dynamic interaction of triggers, cues, reinforcers, cognitions and environmental factors. The application of a such a formulation, sensitive to Simmons and Griffiths (2009) aforementioned observations, proved useful in affording insights into the contextual and maintaining factors of Alan’s drug use which was heavily influenced by the availability of drugs ,his peer group (with whom he spent long periods of time) and their petty drug dealing and criminality. Similarly, engaging with his football team mates during the lead up to an important match significantly reduced his drug use and at certain times of the year even lead to abstinence. Sharing this formulation allowed him to note how his drug use patterns were driven, as per the CBT paradigm, by modifiable external, transient, and specific factors (e.g. cues, reinforcements, social networks and related expectations and social pressures).

Employing the A-CRA model allowed for this tailored fit as A-CRA specifically encourages the patient to identify their own need and desire for change. Alan identified the specific needs that were met by using substances and he developed and reinforced skills that provided him with alternative ways of meeting those needs. This model worked extremely well for Alan as he had identified and had ready access to a pro- social ‘alternative group’ or community. As he had had access to an alternative positive peer group and another activity (sport) which he was ‘really good at’, he simply needed to see the evidence of how his context could radically affect his substance use; more specifically how his beliefs, thinking and actions in certain circumstances produced very different drug use consequences and outcomes.

6. Course of Treatment and Assessment of Progress

One focus of CBT treatment is on teaching and practising specific helpful behaviours, whilst trying to limit cognitive demands on clients. Repetition is central to the learning process in order to develop proficiency and to ensure that newly acquired behaviours will be available when needed. Therefore, behavioural using rehearsal will emphasize varied, realistic case examples to enhance generalization to real life settings. During practice periods and exercises, patients are asked to identify signals that indicate high-risk situations, demonstrating their understanding of when to use newly acquired coping skills. CBT is designed to remedy possible deficits in coping skills by better managing those identified antecedents to substance use. Individuals who rely primarily on substances to cope have little choice but to resort to substance use when the need to cope arises. Understanding, anticipating and avoiding high risk drug use scenarios or the “early warning signals” of imminent drug use is a key CBT clinical activity.

A major goal of a CBT/A-CRA therapeutic approach is to provide a range of basic alternative skills to cope with situations that might otherwise lead to substance use. As ‘skill deficits’ are viewed as fundamental to the drug use trajectory or relapse process, an emphasis is placed on the development and practice of coping skills. A-CRA was manualised in 2001 as part of the Cannabis Youth Treatment Series (CYT) and was tested in that study [21] and more recently with homeless youth [23] . It was also adapted for use in a manual for Assertive Continuing Care following residential treatment [20] .

There are twelve standard and three optional procedures proposed in the A-CRA model. The delivery of the intervention is flexible and based on individual adolescent needs, though the manual provides some general guidelines regarding the general order of procedures. Optional procedures are ‘Dealing with Failure to Attend’, ‘Job-Seeking Skills’, and ‘Anger Management’. Standard procedures are included in table 3 below. For a more detailed description of sessions and procedures please see appendices.

Smith and Myers describe the theoretical underpinnings of CRA as a comprehensive behavioural program for treating substance-abuse problems. It is based on the belief that environmental contingencies can play a powerful role in encouraging or discouraging drinking or drug use. Consequently, it utilizes social, recreational, familial, and vocational reinforcers to assist consumers in the recovery process. Its goal is to essentially make a sober lifestyle more rewarding than the use of substances. Interestingly the authors note: ‘Oddly enough, however, while virtually every review of alcohol and drug treatment outcome research lists CRA among approaches with the strongest scientific evidence of efficacy, very few clinicians who treat consumers with addictions are familiar with it’. ‘The overall philosophy is to promote community based rewarding of non drug-using behaviour so that the patient makes healthy lifestyle changes’ p.3 [25] .

A-CRA procedures use ‘operant techniques and skills training activities’ to educate patients and present alternative ways of dealing with challenges without substances. Traditionally, CRA is provided in an individual, context-specific approach that focuses on the interaction between individuals and those in their environments. A-CRA therapists teach adolescents when and where to use the techniques, given the reality of each individual’s social environment. This tailored approach is facilitated by conducting a ‘functional analysis’ of the adolescent’s behaviour at the beginning of therapy so they can better understand and interrupt the links in the behavioural chain typically leading to episodes of drug use. A-CRA therapists then teach individuals how to improve communication and other skills, build on their reinforcers for abstinence and use existing community resources that will support positive change and constructive support systems.

A-CRA emphasises lapse and relapse prevention. Relapseprevention cognitive behavioural therapy (RP-CBT) is derived from a cognitive model of drug misuse. The emphasis is on identifying and modifying irrational thoughts, managing negative mood and intervening after a lapse to prevent a full-blown relapse [26] . The emphasis is on development of skills to (a) recognize High Risk Situations (HRS) or states where clients are most vulnerable to drug use, (b) avoidance of HRS, and (C) to use a variety of cognitive and behavioural strategies to cope effectively with these situations. RPCBT differs from typical CBT in that the accent is on training people who misuse drugs to develop skills to identify and anticipate situations or states where they are most vulnerable to drug use and to use a range of cognitive and behavioural strategies to cope effectively with these situations [26] .

7. Access and Barriers to Care

Alan engaged with the service for eight months. During this time he received twenty sessions, three of which were assessment focused, the remaining seventeen sessions were A-CRA focused; two of the seventeen involved his mother, the remaining fifteen were individual. As Alan was referred by the probation services, he was initially somewhat ambivalent about drug use focussed interventions. His early motivation for engagement was primarily to avoid the possibility of a custodial sentence.

8. Treatment

My sessions with Alan were guided by the principles of A-CRA [27] which focuses on coping skills training and relapse prevention approaches to the treatment of addictive disorders. Prior to engaging with Alan, I had completed the training course and commenced the A-CRA accreditation process, both under the stewardship of Dr Bob Meyers, whose training and publication offers detailed guidelines on skills training and relapse prevention with young people in a similar context [27] .

During the early part of each session I focused on getting a clear understanding of Alan’s current concerns, his general level of functioning, his substance abuse and pattern of craving during the past week. His experiences with therapy homework, the primary focus being on what insight he gained by completing such exercises was also explored. I spent considerable time engaged in a detailed review of Alan’s experience with the implementation of homework tasks during which the following themes were reviewed:

-Gauging whether drug use cessation was easier or harder than he anticipated? -Which, if any, of the coping strategies worked best? -Which strategies did not work as well as expected. Did he develop any new strategies? -Conveying the importance of skills practice, emphasising how we both gained greater insights into how cognitions influenced his behaviour. After developing a clear sense of Alan’s general functioning, current concerns and progress with homework implementation, I initiated the session topic for that week. I linked the relevance of the session topic to Alan’s current cannabis-related concerns and introduced the topic by using concrete examples from Alan’s recent experience. While reviewing the material, I repeatedly ensured that Alan understood the topic by asking for concrete examples, while also eliciting Alan’s views on how he might use these particular skills in the future.

Godley & Meyers [21] propose a homework exercise to accompany each session. An advantage of using these homework sheets is that they also summarise key points about each topic and therefore serve as a useful reminder to the patient of the material discussed each week. Meyers, et al. (2011) suggests that rather than being bound by the suggested exercises in the manualised approach, they may be used as a starting point for discussing the best way to implement the required skill and to develop individualised variations for new assignments [27] . The final part of each session focused on Alan’s plan for the week ahead and any anticipated high-risk situations. I endeavoured to model the idea that patients can literally ‘plan themselves out of using’ cannabis or other drugs. For each anticipated high-risk situation, we identified appropriate and viable coping skills. Better understanding, anticipating and planning for high-risk situations was difficult in the beginning of treatment as Alan was not particularly used to planning or thinking through his activities. For a patient like Alan, whose home life is often chaotic, this helped promote a growing sense of self efficacy. Similarly, as Alan had been heavily involved with drug use for a long time, he discovered through this process that he had few meaningful activities to fill his time or serve as alternatives to drug use. This provided me with an opportunity to discuss strategies to rebuild an activity schedule and a social network.

During our sessions, several skill topics were covered. I carefully selected skills to match Alan’s needs. I selected coping skills that he has used in the past and introduced one or two more that were consistent with his cognitive style. Alan’s cognitive score indicated a cognitive approach reflecting poor problem solving or planning. Sessions focused on generic skills including interpersonal skills, goal setting, coping with criticism or anger, problem solving and planning. The goal was to teach Alan how to build on his pro- social reinforcers, how to use existing community resources supportive of positive change and how to develop a positive support system.

The sequence in which these topics were presented was based on (a) patient needs and (b) clinician judgment (a full description of individual sessions may be found in appendices).

A-CRA procedures use ‘operant techniques and skills training activities’ to educate patients and present alternative ways of dealing with challenges without substances. Traditionally, CRA is provided in an individual, context-specific approach that focuses on the interaction between individuals and those in their environments. A-CRA therapists teach adolescents when and where to use the techniques, given the reality of each individual’s social environment.

9. Assessment of Treatment Outcome

A baseline diagnostic assessment of outcomes was completed upon treatment entry. This assessment consisted of a battery of psychological instruments including (see appendices for full a description of assessment measures):

-The Maudsley Addiction Profile (MAP). -The Beck Youth Inventories. -The World Health Organization Alcohol, Smoking and Substance Involvement Screening Test (ASSIST).

In addition to the above, objective feedback on Alan’s clinical and drug use status through urine toxicology screens was an important part of his drug treatment. Urine specimens were collected before each session and available for the following session. The use of toxicology reports throughout treatment are considered a valuable clinical tool. This part of the session presents a good opportunity to review the results of the most recent urine toxicology screen and promote meaningful therapeutic activities in the context of the patient’s treatment goals [28] .

In reporting on substance use since the last session, patients are likely to reveal a great deal about their general level of functioning and the types of issues and problems of most current concern. This allows the clinician to gauge if the patient has made progress in reducing drug use, his current level of motivation, whether there is a reasonable level of support available in efforts to remain abstinent and what is currently bothering him. Functional analyses are opportunistically used throughout treatment as needed. For example, if cannabis use occurs, patients are encouraged to analyse antecedent events so as to determine how to avoid using in similar situations in the future. The purpose is to help the patient understand the trajectory and modifiable contextual factors associated with drug use, challenge unhelpful positive drug use expectancies, identify possible skills deficiencies as well as seeking functionally equivalent non- drug using behaviours so as to reduce the probability of future drug use. The approach I used is based on the work of [28] .

The Functional Analysis was used to identify a number of factors occurring within a relatively brief time frame that influenced the occurrence of problem behaviours. It was used as an initial screening tool as part of a comprehensive functional assessment or analysis of problem behaviour. The results of the functional analysis then served as a basis for conducting direct observations in a number of different contexts to attest to likely behavioural functions, clarify ambiguous functions, and identify other relevant factors that are maintaining the behaviour.

The Happiness Scale rates the adolescent’s feelings about several critical areas of life. It helps therapists and adolescents identify areas of life that adolescents feel happy about and alternatively areas in which they have problems or challenges. Most importantly it identifies potential treatment goals subjectively meaningful to the patient, facilitates positive behaviour change in a range of life domains as well as help clients track their progress during treatment.

Alan’s BYI score (Table 4) indicates that at the time of assessment he was within the average scoring range on ‘self-concept’, and moderately elevated in the areas of ‘depression’, ‘anxiety’, and ‘disruptive behaviour’. His score for ‘anger’ suggested that his anger fell within the extremely elevated range. When this was discussed with Alan he agreed that this was quite accurate. Anger, and in particular controlling his anger, was subjectively identified as a treatment goal.

10. Follow-up

Given that follow-up occurred by telephone it was not feasible to administer the full battery of tests. With Alan’s treatment goals in mind it was decided to administer the MAP and ASSIST. Table 5 below illustrates Alan’s score at baseline and follow-up for the MAP and ASSIST. For summary purposes I have taken areas for concern at baseline for both instruments.

Alan’s score for cannabis was the most clinically relevant as it placed him in the 'high risk’ domain while his alcohol score indicated that he had engaged in binge drinking (6+ drinks) at T1. However, at T2 Alan’s score suggests that he had made considerable reductions in the use of both substances. Also his MAP scores for parental conflict and drug dealing suggest that he had also made major positive changes in the relevant domains of personal and social functioning as well as ceasing criminal behaviour.

At 3 months post-discharge I contacted Alan by phone. He had maintained and continued to further his progress. His drug use was at a minimal level (1 or 2 shared joints per month). He was no longer engaged in crime and his probationary period with the judicial system had passed. He had received a caution for his earlier drugs charge. At the time of follow-up he was enjoying participating in a Sports Coaching course and was excelling with his study assignments. Relationships had improved considerably with his mother and sister and he had re-engaged with a previous, positive, peer group linked to his involvement with the GAA . Overall he felt he was doing extremely well.

11. Complicating Factors with A-CRA Model

There are many challenges that may arise in the treatment of substance use disorders that can serve as barriers to successful treatment. These include acute or chronic cognitive deficits, health problems, social stressors and a lack of social resources [7] . Among individuals presenting with substance use there are often other significant life challenges including early school leaving, family conflicts, legal issues, poor or deviant social networks, etc. A particular challenge with Alan’s case was the social and environmental milieu which he shared with his drug using peers. For Alan, who initially had few skills and resources, engaging in treatment meant not only being asked to change his overall way of life but also to renounce some of those components in which he enjoyed a sense of belonging, particularly as he had invested significantly in these friendships. A sense of ‘belonging to the substance use culture’ can increase ambivalence for change [7] . Alan’s mother strongly disapproved of his drug using peer group and failed to acknowledge Alan’s perceived loss. This resulted in mother- son conflict. The use of the caregiver session allowed an exploration of perceived ‘losses’ relative to the ‘gains’ associated with Alan’s abstinence. It was moreover seen to be critical to establish alternatives for achieving a sense of belonging, including both his social connection and his social effectiveness. Alan’s sports ability allowed for this to be fostered. He is a talented sportsman which often meant his acceptance within a team or group is a given.