How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal

- Open access

- Published: 30 April 2020

- Volume 36 , pages 909–913, ( 2021 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Clara Busse ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0178-1000 1 &

- Ella August ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-5151-1036 1 , 2

269k Accesses

15 Citations

719 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

Communicating research findings is an essential step in the research process. Often, peer-reviewed journals are the forum for such communication, yet many researchers are never taught how to write a publishable scientific paper. In this article, we explain the basic structure of a scientific paper and describe the information that should be included in each section. We also identify common pitfalls for each section and recommend strategies to avoid them. Further, we give advice about target journal selection and authorship. In the online resource 1 , we provide an example of a high-quality scientific paper, with annotations identifying the elements we describe in this article.

Similar content being viewed by others

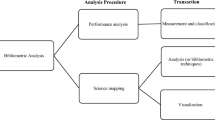

How to design bibliometric research: an overview and a framework proposal

Literature reviews as independent studies: guidelines for academic practice

Why, When, Who, What, How, and Where for Trainees Writing Literature Review Articles

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Writing a scientific paper is an important component of the research process, yet researchers often receive little formal training in scientific writing. This is especially true in low-resource settings. In this article, we explain why choosing a target journal is important, give advice about authorship, provide a basic structure for writing each section of a scientific paper, and describe common pitfalls and recommendations for each section. In the online resource 1 , we also include an annotated journal article that identifies the key elements and writing approaches that we detail here. Before you begin your research, make sure you have ethical clearance from all relevant ethical review boards.

Select a Target Journal Early in the Writing Process

We recommend that you select a “target journal” early in the writing process; a “target journal” is the journal to which you plan to submit your paper. Each journal has a set of core readers and you should tailor your writing to this readership. For example, if you plan to submit a manuscript about vaping during pregnancy to a pregnancy-focused journal, you will need to explain what vaping is because readers of this journal may not have a background in this topic. However, if you were to submit that same article to a tobacco journal, you would not need to provide as much background information about vaping.

Information about a journal’s core readership can be found on its website, usually in a section called “About this journal” or something similar. For example, the Journal of Cancer Education presents such information on the “Aims and Scope” page of its website, which can be found here: https://www.springer.com/journal/13187/aims-and-scope .

Peer reviewer guidelines from your target journal are an additional resource that can help you tailor your writing to the journal and provide additional advice about crafting an effective article [ 1 ]. These are not always available, but it is worth a quick web search to find out.

Identify Author Roles Early in the Process

Early in the writing process, identify authors, determine the order of authors, and discuss the responsibilities of each author. Standard author responsibilities have been identified by The International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) [ 2 ]. To set clear expectations about each team member’s responsibilities and prevent errors in communication, we also suggest outlining more detailed roles, such as who will draft each section of the manuscript, write the abstract, submit the paper electronically, serve as corresponding author, and write the cover letter. It is best to formalize this agreement in writing after discussing it, circulating the document to the author team for approval. We suggest creating a title page on which all authors are listed in the agreed-upon order. It may be necessary to adjust authorship roles and order during the development of the paper. If a new author order is agreed upon, be sure to update the title page in the manuscript draft.

In the case where multiple papers will result from a single study, authors should discuss who will author each paper. Additionally, authors should agree on a deadline for each paper and the lead author should take responsibility for producing an initial draft by this deadline.

Structure of the Introduction Section

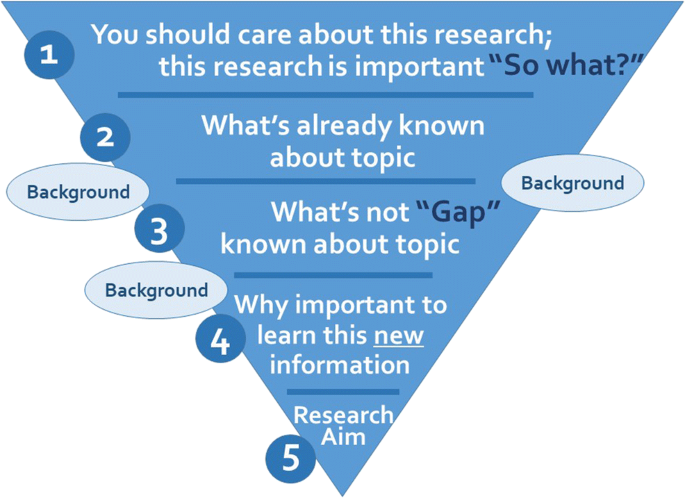

The introduction section should be approximately three to five paragraphs in length. Look at examples from your target journal to decide the appropriate length. This section should include the elements shown in Fig. 1 . Begin with a general context, narrowing to the specific focus of the paper. Include five main elements: why your research is important, what is already known about the topic, the “gap” or what is not yet known about the topic, why it is important to learn the new information that your research adds, and the specific research aim(s) that your paper addresses. Your research aim should address the gap you identified. Be sure to add enough background information to enable readers to understand your study. Table 1 provides common introduction section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

The main elements of the introduction section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Methods Section

The purpose of the methods section is twofold: to explain how the study was done in enough detail to enable its replication and to provide enough contextual detail to enable readers to understand and interpret the results. In general, the essential elements of a methods section are the following: a description of the setting and participants, the study design and timing, the recruitment and sampling, the data collection process, the dataset, the dependent and independent variables, the covariates, the analytic approach for each research objective, and the ethical approval. The hallmark of an exemplary methods section is the justification of why each method was used. Table 2 provides common methods section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Results Section

The focus of the results section should be associations, or lack thereof, rather than statistical tests. Two considerations should guide your writing here. First, the results should present answers to each part of the research aim. Second, return to the methods section to ensure that the analysis and variables for each result have been explained.

Begin the results section by describing the number of participants in the final sample and details such as the number who were approached to participate, the proportion who were eligible and who enrolled, and the number of participants who dropped out. The next part of the results should describe the participant characteristics. After that, you may organize your results by the aim or by putting the most exciting results first. Do not forget to report your non-significant associations. These are still findings.

Tables and figures capture the reader’s attention and efficiently communicate your main findings [ 3 ]. Each table and figure should have a clear message and should complement, rather than repeat, the text. Tables and figures should communicate all salient details necessary for a reader to understand the findings without consulting the text. Include information on comparisons and tests, as well as information about the sample and timing of the study in the title, legend, or in a footnote. Note that figures are often more visually interesting than tables, so if it is feasible to make a figure, make a figure. To avoid confusing the reader, either avoid abbreviations in tables and figures, or define them in a footnote. Note that there should not be citations in the results section and you should not interpret results here. Table 3 provides common results section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Discussion Section

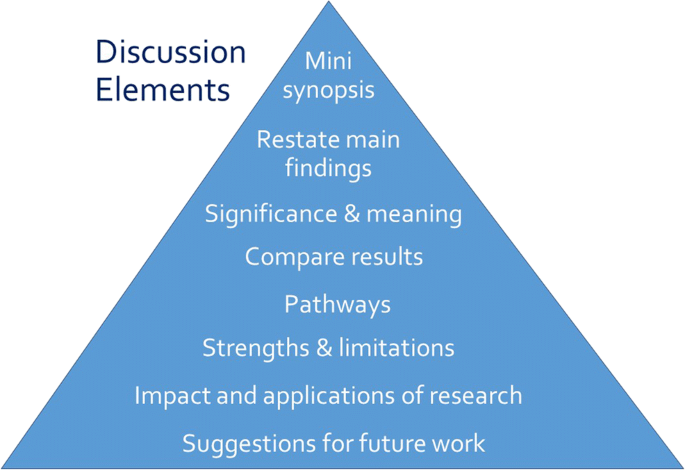

Opposite the introduction section, the discussion should take the form of a right-side-up triangle beginning with interpretation of your results and moving to general implications (Fig. 2 ). This section typically begins with a restatement of the main findings, which can usually be accomplished with a few carefully-crafted sentences.

Major elements of the discussion section of an original research article. Often, the elements overlap

Next, interpret the meaning or explain the significance of your results, lifting the reader’s gaze from the study’s specific findings to more general applications. Then, compare these study findings with other research. Are these findings in agreement or disagreement with those from other studies? Does this study impart additional nuance to well-accepted theories? Situate your findings within the broader context of scientific literature, then explain the pathways or mechanisms that might give rise to, or explain, the results.

Journals vary in their approach to strengths and limitations sections: some are embedded paragraphs within the discussion section, while some mandate separate section headings. Keep in mind that every study has strengths and limitations. Candidly reporting yours helps readers to correctly interpret your research findings.

The next element of the discussion is a summary of the potential impacts and applications of the research. Should these results be used to optimally design an intervention? Does the work have implications for clinical protocols or public policy? These considerations will help the reader to further grasp the possible impacts of the presented work.

Finally, the discussion should conclude with specific suggestions for future work. Here, you have an opportunity to illuminate specific gaps in the literature that compel further study. Avoid the phrase “future research is necessary” because the recommendation is too general to be helpful to readers. Instead, provide substantive and specific recommendations for future studies. Table 4 provides common discussion section pitfalls and recommendations for addressing them.

Follow the Journal’s Author Guidelines

After you select a target journal, identify the journal’s author guidelines to guide the formatting of your manuscript and references. Author guidelines will often (but not always) include instructions for titles, cover letters, and other components of a manuscript submission. Read the guidelines carefully. If you do not follow the guidelines, your article will be sent back to you.

Finally, do not submit your paper to more than one journal at a time. Even if this is not explicitly stated in the author guidelines of your target journal, it is considered inappropriate and unprofessional.

Your title should invite readers to continue reading beyond the first page [ 4 , 5 ]. It should be informative and interesting. Consider describing the independent and dependent variables, the population and setting, the study design, the timing, and even the main result in your title. Because the focus of the paper can change as you write and revise, we recommend you wait until you have finished writing your paper before composing the title.

Be sure that the title is useful for potential readers searching for your topic. The keywords you select should complement those in your title to maximize the likelihood that a researcher will find your paper through a database search. Avoid using abbreviations in your title unless they are very well known, such as SNP, because it is more likely that someone will use a complete word rather than an abbreviation as a search term to help readers find your paper.

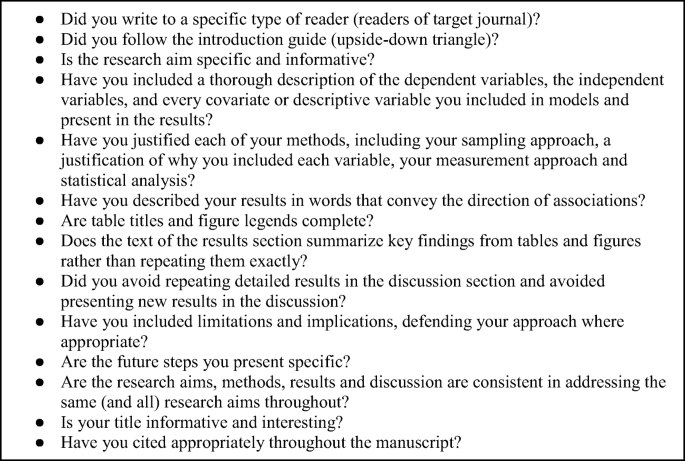

After you have written a complete draft, use the checklist (Fig. 3 ) below to guide your revisions and editing. Additional resources are available on writing the abstract and citing references [ 5 ]. When you feel that your work is ready, ask a trusted colleague or two to read the work and provide informal feedback. The box below provides a checklist that summarizes the key points offered in this article.

Checklist for manuscript quality

Data Availability

Michalek AM (2014) Down the rabbit hole…advice to reviewers. J Cancer Educ 29:4–5

Article Google Scholar

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Defining the role of authors and contributors: who is an author? http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/defining-the-role-of-authosrs-and-contributors.html . Accessed 15 January, 2020

Vetto JT (2014) Short and sweet: a short course on concise medical writing. J Cancer Educ 29(1):194–195

Brett M, Kording K (2017) Ten simple rules for structuring papers. PLoS ComputBiol. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pcbi.1005619

Lang TA (2017) Writing a better research article. J Public Health Emerg. https://doi.org/10.21037/jphe.2017.11.06

Download references

Acknowledgments

Ella August is grateful to the Sustainable Sciences Institute for mentoring her in training researchers on writing and publishing their research.

Code Availability

Not applicable.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Maternal and Child Health, University of North Carolina Gillings School of Global Public Health, 135 Dauer Dr, 27599, Chapel Hill, NC, USA

Clara Busse & Ella August

Department of Epidemiology, University of Michigan School of Public Health, 1415 Washington Heights, Ann Arbor, MI, 48109-2029, USA

Ella August

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Ella August .

Ethics declarations

Conflicts of interests.

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Electronic supplementary material

(PDF 362 kb)

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Busse, C., August, E. How to Write and Publish a Research Paper for a Peer-Reviewed Journal. J Canc Educ 36 , 909–913 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Download citation

Published : 30 April 2020

Issue Date : October 2021

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-020-01751-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Manuscripts

- Scientific writing

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

13.1 Formatting a Research Paper

Learning objectives.

- Identify the major components of a research paper written using American Psychological Association (APA) style.

- Apply general APA style and formatting conventions in a research paper.

In this chapter, you will learn how to use APA style , the documentation and formatting style followed by the American Psychological Association, as well as MLA style , from the Modern Language Association. There are a few major formatting styles used in academic texts, including AMA, Chicago, and Turabian:

- AMA (American Medical Association) for medicine, health, and biological sciences

- APA (American Psychological Association) for education, psychology, and the social sciences

- Chicago—a common style used in everyday publications like magazines, newspapers, and books

- MLA (Modern Language Association) for English, literature, arts, and humanities

- Turabian—another common style designed for its universal application across all subjects and disciplines

While all the formatting and citation styles have their own use and applications, in this chapter we focus our attention on the two styles you are most likely to use in your academic studies: APA and MLA.

If you find that the rules of proper source documentation are difficult to keep straight, you are not alone. Writing a good research paper is, in and of itself, a major intellectual challenge. Having to follow detailed citation and formatting guidelines as well may seem like just one more task to add to an already-too-long list of requirements.

Following these guidelines, however, serves several important purposes. First, it signals to your readers that your paper should be taken seriously as a student’s contribution to a given academic or professional field; it is the literary equivalent of wearing a tailored suit to a job interview. Second, it shows that you respect other people’s work enough to give them proper credit for it. Finally, it helps your reader find additional materials if he or she wishes to learn more about your topic.

Furthermore, producing a letter-perfect APA-style paper need not be burdensome. Yes, it requires careful attention to detail. However, you can simplify the process if you keep these broad guidelines in mind:

- Work ahead whenever you can. Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” includes tips for keeping track of your sources early in the research process, which will save time later on.

- Get it right the first time. Apply APA guidelines as you write, so you will not have much to correct during the editing stage. Again, putting in a little extra time early on can save time later.

- Use the resources available to you. In addition to the guidelines provided in this chapter, you may wish to consult the APA website at http://www.apa.org or the Purdue University Online Writing lab at http://owl.english.purdue.edu , which regularly updates its online style guidelines.

General Formatting Guidelines

This chapter provides detailed guidelines for using the citation and formatting conventions developed by the American Psychological Association, or APA. Writers in disciplines as diverse as astrophysics, biology, psychology, and education follow APA style. The major components of a paper written in APA style are listed in the following box.

These are the major components of an APA-style paper:

Body, which includes the following:

- Headings and, if necessary, subheadings to organize the content

- In-text citations of research sources

- References page

All these components must be saved in one document, not as separate documents.

The title page of your paper includes the following information:

- Title of the paper

- Author’s name

- Name of the institution with which the author is affiliated

- Header at the top of the page with the paper title (in capital letters) and the page number (If the title is lengthy, you may use a shortened form of it in the header.)

List the first three elements in the order given in the previous list, centered about one third of the way down from the top of the page. Use the headers and footers tool of your word-processing program to add the header, with the title text at the left and the page number in the upper-right corner. Your title page should look like the following example.

The next page of your paper provides an abstract , or brief summary of your findings. An abstract does not need to be provided in every paper, but an abstract should be used in papers that include a hypothesis. A good abstract is concise—about one hundred fifty to two hundred fifty words—and is written in an objective, impersonal style. Your writing voice will not be as apparent here as in the body of your paper. When writing the abstract, take a just-the-facts approach, and summarize your research question and your findings in a few sentences.

In Chapter 12 “Writing a Research Paper” , you read a paper written by a student named Jorge, who researched the effectiveness of low-carbohydrate diets. Read Jorge’s abstract. Note how it sums up the major ideas in his paper without going into excessive detail.

Write an abstract summarizing your paper. Briefly introduce the topic, state your findings, and sum up what conclusions you can draw from your research. Use the word count feature of your word-processing program to make sure your abstract does not exceed one hundred fifty words.

Depending on your field of study, you may sometimes write research papers that present extensive primary research, such as your own experiment or survey. In your abstract, summarize your research question and your findings, and briefly indicate how your study relates to prior research in the field.

Margins, Pagination, and Headings

APA style requirements also address specific formatting concerns, such as margins, pagination, and heading styles, within the body of the paper. Review the following APA guidelines.

Use these general guidelines to format the paper:

- Set the top, bottom, and side margins of your paper at 1 inch.

- Use double-spaced text throughout your paper.

- Use a standard font, such as Times New Roman or Arial, in a legible size (10- to 12-point).

- Use continuous pagination throughout the paper, including the title page and the references section. Page numbers appear flush right within your header.

- Section headings and subsection headings within the body of your paper use different types of formatting depending on the level of information you are presenting. Additional details from Jorge’s paper are provided.

Begin formatting the final draft of your paper according to APA guidelines. You may work with an existing document or set up a new document if you choose. Include the following:

- Your title page

- The abstract you created in Note 13.8 “Exercise 1”

- Correct headers and page numbers for your title page and abstract

APA style uses section headings to organize information, making it easy for the reader to follow the writer’s train of thought and to know immediately what major topics are covered. Depending on the length and complexity of the paper, its major sections may also be divided into subsections, sub-subsections, and so on. These smaller sections, in turn, use different heading styles to indicate different levels of information. In essence, you are using headings to create a hierarchy of information.

The following heading styles used in APA formatting are listed in order of greatest to least importance:

- Section headings use centered, boldface type. Headings use title case, with important words in the heading capitalized.

- Subsection headings use left-aligned, boldface type. Headings use title case.

- The third level uses left-aligned, indented, boldface type. Headings use a capital letter only for the first word, and they end in a period.

- The fourth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are boldfaced and italicized.

- The fifth level follows the same style used for the previous level, but the headings are italicized and not boldfaced.

Visually, the hierarchy of information is organized as indicated in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” .

Table 13.1 Section Headings

A college research paper may not use all the heading levels shown in Table 13.1 “Section Headings” , but you are likely to encounter them in academic journal articles that use APA style. For a brief paper, you may find that level 1 headings suffice. Longer or more complex papers may need level 2 headings or other lower-level headings to organize information clearly. Use your outline to craft your major section headings and determine whether any subtopics are substantial enough to require additional levels of headings.

Working with the document you developed in Note 13.11 “Exercise 2” , begin setting up the heading structure of the final draft of your research paper according to APA guidelines. Include your title and at least two to three major section headings, and follow the formatting guidelines provided above. If your major sections should be broken into subsections, add those headings as well. Use your outline to help you.

Because Jorge used only level 1 headings, his Exercise 3 would look like the following:

Citation Guidelines

In-text citations.

Throughout the body of your paper, include a citation whenever you quote or paraphrase material from your research sources. As you learned in Chapter 11 “Writing from Research: What Will I Learn?” , the purpose of citations is twofold: to give credit to others for their ideas and to allow your reader to follow up and learn more about the topic if desired. Your in-text citations provide basic information about your source; each source you cite will have a longer entry in the references section that provides more detailed information.

In-text citations must provide the name of the author or authors and the year the source was published. (When a given source does not list an individual author, you may provide the source title or the name of the organization that published the material instead.) When directly quoting a source, it is also required that you include the page number where the quote appears in your citation.

This information may be included within the sentence or in a parenthetical reference at the end of the sentence, as in these examples.

Epstein (2010) points out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Here, the writer names the source author when introducing the quote and provides the publication date in parentheses after the author’s name. The page number appears in parentheses after the closing quotation marks and before the period that ends the sentence.

Addiction researchers caution that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (Epstein, 2010, p. 137).

Here, the writer provides a parenthetical citation at the end of the sentence that includes the author’s name, the year of publication, and the page number separated by commas. Again, the parenthetical citation is placed after the closing quotation marks and before the period at the end of the sentence.

As noted in the book Junk Food, Junk Science (Epstein, 2010, p. 137), “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive.”

Here, the writer chose to mention the source title in the sentence (an optional piece of information to include) and followed the title with a parenthetical citation. Note that the parenthetical citation is placed before the comma that signals the end of the introductory phrase.

David Epstein’s book Junk Food, Junk Science (2010) pointed out that “junk food cannot be considered addictive in the same way that we think of psychoactive drugs as addictive” (p. 137).

Another variation is to introduce the author and the source title in your sentence and include the publication date and page number in parentheses within the sentence or at the end of the sentence. As long as you have included the essential information, you can choose the option that works best for that particular sentence and source.

Citing a book with a single author is usually a straightforward task. Of course, your research may require that you cite many other types of sources, such as books or articles with more than one author or sources with no individual author listed. You may also need to cite sources available in both print and online and nonprint sources, such as websites and personal interviews. Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.2 “Citing and Referencing Techniques” and Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provide extensive guidelines for citing a variety of source types.

Writing at Work

APA is just one of several different styles with its own guidelines for documentation, formatting, and language usage. Depending on your field of interest, you may be exposed to additional styles, such as the following:

- MLA style. Determined by the Modern Languages Association and used for papers in literature, languages, and other disciplines in the humanities.

- Chicago style. Outlined in the Chicago Manual of Style and sometimes used for papers in the humanities and the sciences; many professional organizations use this style for publications as well.

- Associated Press (AP) style. Used by professional journalists.

References List

The brief citations included in the body of your paper correspond to the more detailed citations provided at the end of the paper in the references section. In-text citations provide basic information—the author’s name, the publication date, and the page number if necessary—while the references section provides more extensive bibliographical information. Again, this information allows your reader to follow up on the sources you cited and do additional reading about the topic if desired.

The specific format of entries in the list of references varies slightly for different source types, but the entries generally include the following information:

- The name(s) of the author(s) or institution that wrote the source

- The year of publication and, where applicable, the exact date of publication

- The full title of the source

- For books, the city of publication

- For articles or essays, the name of the periodical or book in which the article or essay appears

- For magazine and journal articles, the volume number, issue number, and pages where the article appears

- For sources on the web, the URL where the source is located

The references page is double spaced and lists entries in alphabetical order by the author’s last name. If an entry continues for more than one line, the second line and each subsequent line are indented five spaces. Review the following example. ( Chapter 13 “APA and MLA Documentation and Formatting” , Section 13.3 “Creating a References Section” provides extensive guidelines for formatting reference entries for different types of sources.)

In APA style, book and article titles are formatted in sentence case, not title case. Sentence case means that only the first word is capitalized, along with any proper nouns.

Key Takeaways

- Following proper citation and formatting guidelines helps writers ensure that their work will be taken seriously, give proper credit to other authors for their work, and provide valuable information to readers.

- Working ahead and taking care to cite sources correctly the first time are ways writers can save time during the editing stage of writing a research paper.

- APA papers usually include an abstract that concisely summarizes the paper.

- APA papers use a specific headings structure to provide a clear hierarchy of information.

- In APA papers, in-text citations usually include the name(s) of the author(s) and the year of publication.

- In-text citations correspond to entries in the references section, which provide detailed bibliographical information about a source.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Help | Advanced Search

arXiv is a free distribution service and an open-access archive for nearly 2.4 million scholarly articles in the fields of physics, mathematics, computer science, quantitative biology, quantitative finance, statistics, electrical engineering and systems science, and economics. Materials on this site are not peer-reviewed by arXiv.

arXiv is a free distribution service and an open-access archive for scholarly articles in the fields of physics, mathematics, computer science, quantitative biology, quantitative finance, statistics, electrical engineering and systems science, and economics. Materials on this site are not peer-reviewed by arXiv.

Stay up to date with what is happening at arXiv on our blog.

Latest news

- Astrophysics ( astro-ph new , recent , search ) Astrophysics of Galaxies ; Cosmology and Nongalactic Astrophysics ; Earth and Planetary Astrophysics ; High Energy Astrophysical Phenomena ; Instrumentation and Methods for Astrophysics ; Solar and Stellar Astrophysics

- Condensed Matter ( cond-mat new , recent , search ) Disordered Systems and Neural Networks ; Materials Science ; Mesoscale and Nanoscale Physics ; Other Condensed Matter ; Quantum Gases ; Soft Condensed Matter ; Statistical Mechanics ; Strongly Correlated Electrons ; Superconductivity

- General Relativity and Quantum Cosmology ( gr-qc new , recent , search )

- High Energy Physics - Experiment ( hep-ex new , recent , search )

- High Energy Physics - Lattice ( hep-lat new , recent , search )

- High Energy Physics - Phenomenology ( hep-ph new , recent , search )

- High Energy Physics - Theory ( hep-th new , recent , search )

- Mathematical Physics ( math-ph new , recent , search )

- Nonlinear Sciences ( nlin new , recent , search ) includes: Adaptation and Self-Organizing Systems ; Cellular Automata and Lattice Gases ; Chaotic Dynamics ; Exactly Solvable and Integrable Systems ; Pattern Formation and Solitons

- Nuclear Experiment ( nucl-ex new , recent , search )

- Nuclear Theory ( nucl-th new , recent , search )

- Physics ( physics new , recent , search ) includes: Accelerator Physics ; Applied Physics ; Atmospheric and Oceanic Physics ; Atomic and Molecular Clusters ; Atomic Physics ; Biological Physics ; Chemical Physics ; Classical Physics ; Computational Physics ; Data Analysis, Statistics and Probability ; Fluid Dynamics ; General Physics ; Geophysics ; History and Philosophy of Physics ; Instrumentation and Detectors ; Medical Physics ; Optics ; Physics and Society ; Physics Education ; Plasma Physics ; Popular Physics ; Space Physics

- Quantum Physics ( quant-ph new , recent , search )

Mathematics

- Mathematics ( math new , recent , search ) includes: (see detailed description ): Algebraic Geometry ; Algebraic Topology ; Analysis of PDEs ; Category Theory ; Classical Analysis and ODEs ; Combinatorics ; Commutative Algebra ; Complex Variables ; Differential Geometry ; Dynamical Systems ; Functional Analysis ; General Mathematics ; General Topology ; Geometric Topology ; Group Theory ; History and Overview ; Information Theory ; K-Theory and Homology ; Logic ; Mathematical Physics ; Metric Geometry ; Number Theory ; Numerical Analysis ; Operator Algebras ; Optimization and Control ; Probability ; Quantum Algebra ; Representation Theory ; Rings and Algebras ; Spectral Theory ; Statistics Theory ; Symplectic Geometry

Computer Science

- Computing Research Repository ( CoRR new , recent , search ) includes: (see detailed description ): Artificial Intelligence ; Computation and Language ; Computational Complexity ; Computational Engineering, Finance, and Science ; Computational Geometry ; Computer Science and Game Theory ; Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition ; Computers and Society ; Cryptography and Security ; Data Structures and Algorithms ; Databases ; Digital Libraries ; Discrete Mathematics ; Distributed, Parallel, and Cluster Computing ; Emerging Technologies ; Formal Languages and Automata Theory ; General Literature ; Graphics ; Hardware Architecture ; Human-Computer Interaction ; Information Retrieval ; Information Theory ; Logic in Computer Science ; Machine Learning ; Mathematical Software ; Multiagent Systems ; Multimedia ; Networking and Internet Architecture ; Neural and Evolutionary Computing ; Numerical Analysis ; Operating Systems ; Other Computer Science ; Performance ; Programming Languages ; Robotics ; Social and Information Networks ; Software Engineering ; Sound ; Symbolic Computation ; Systems and Control

Quantitative Biology

- Quantitative Biology ( q-bio new , recent , search ) includes: (see detailed description ): Biomolecules ; Cell Behavior ; Genomics ; Molecular Networks ; Neurons and Cognition ; Other Quantitative Biology ; Populations and Evolution ; Quantitative Methods ; Subcellular Processes ; Tissues and Organs

Quantitative Finance

- Quantitative Finance ( q-fin new , recent , search ) includes: (see detailed description ): Computational Finance ; Economics ; General Finance ; Mathematical Finance ; Portfolio Management ; Pricing of Securities ; Risk Management ; Statistical Finance ; Trading and Market Microstructure

- Statistics ( stat new , recent , search ) includes: (see detailed description ): Applications ; Computation ; Machine Learning ; Methodology ; Other Statistics ; Statistics Theory

Electrical Engineering and Systems Science

- Electrical Engineering and Systems Science ( eess new , recent , search ) includes: (see detailed description ): Audio and Speech Processing ; Image and Video Processing ; Signal Processing ; Systems and Control

- Economics ( econ new , recent , search ) includes: (see detailed description ): Econometrics ; General Economics ; Theoretical Economics

About arXiv

- General information

- How to Submit to arXiv

- Membership & Giving

- Open access

- Published: 24 April 2024

Quantum mechanical analysis of yttrium-stabilized zirconia and alumina: implications for mechanical performance of esthetic crowns

- Ravinder S. Saini 1 ,

- Abdulkhaliq Ali F. Alshadidi 1 ,

- Vishwanath Gurumurthy 1 ,

- Abdulmajeed Okshah 1 ,

- Sunil Kumar Vaddamanu 1 ,

- Rayan Ibrahim H. Binduhayyim 1 ,

- Saurabh Chaturvedi 2 ,

- Shashit Shetty Bavabeedu 3 &

- Artak Heboyan 4 , 5 , 6

European Journal of Medical Research volume 29 , Article number: 254 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

127 Accesses

Metrics details

Yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) and alumina are the most commonly used dental esthetic crown materials. This study aimed to provide detailed information on the comparison between yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) and alumina, the two materials most often used for esthetic crowns in dentistry.

Methodology

The ground-state energy of the materials was calculated using the Cambridge Serial Total Energy Package (CASTEP) code, which employs a first-principles method based on density functional theory (DFT). The electronic exchange–correlation energy was evaluated using the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) within the Perdew (Burke) Ernzerhof scheme.

Optimization of the geometries and investigation of the optical properties, dynamic stability, band structures, refractive indices, and mechanical properties of these materials contribute to a holistic understanding of these materials. Geometric optimization of YSZ provides important insights into its dynamic stability based on observations of its crystal structure and polyhedral geometry, which show stable configurations. Alumina exhibits a distinctive charge, kinetic, and potential (CKP) geometry, which contributes to its interesting structural framework and molecular-level stability. The optical properties of alumina were evaluated using pseudo-atomic computations, demonstrating its responsiveness to external stimuli. The refractive indices, reflectance, and dielectric functions indicate that the transmission of light by alumina depends on numerous factors that are essential for the optical performance of alumina as a material for esthetic crowns. The band structures of both the materials were explored, and the band gap of alumina was determined to be 5.853 eV. In addition, the band structure describes electronic transitions that influence the conductivity and optical properties of a material. The stability of alumina can be deduced from its bandgap, an essential property that determines its use as a dental material. Refractive indices are vital optical properties of esthetic crown materials. Therefore, the ability to understand their refractive-index graphs explains their transparency and color distortion through how the material responds to light..The regulated absorption characteristics exhibited by YSZ render it a highly attractive option for the development of esthetic crowns, as it guarantees minimal color distortion.

The acceptability of materials for esthetic crowns is strongly determined by mechanical properties such as elastic stiffness constants, Young's modulus, and shear modulus. YSZ is a highly durable material for dental applications, owing to its superior mechanical strength.

Introduction

An esthetic dental crown is an esthetic restoration used to replace the original shape, color, size, and thickness of teeth that are damaged or weakened [ 1 ]. This dental procedure is routinely used when a tooth has extensive decay coupled with structural damage, or when the tooth lacks a cosmetically acceptable appearance [ 2 ]. The principal aim of an esthetic crown is to safeguard the damaged tooth while simultaneously improving its function and esthetics [ 3 ].

The materials used to make esthetic crowns are different, and the choice depends on the location of the tooth, chewing needs, and patient preference [ 4 , 5 ]. Porcelain or ceramic crowns are natural-looking teeth that are especially suitable for the front teeth or areas of the mouth where the teeth are visible [ 6 ]. Porcelain-fused-to-metal crowns combine the esthetic appeal of porcelain with the added strength derived from a metal substructure. Zirconia crowns have become increasingly popular because of their strength and appearance. Zirconia ceramics can withstand chipping and cracking. It can be used in anterior and posterior crowns [ 7 , 8 ]. For cases in which both esthetics and strength are important, the solution is porcelain-fused-to-zirconia crowns, which combine the esthetics of porcelain with the strength of zirconia and can also be used for posterior teeth [ 9 ].

The advantages of metal crowns (made from gold or metal alloys) are their strength and durability [ 10 ]. However, because of their metallic appearance, these crowns are less commonly used in visible areas of the mouth. Composite resin crowns are made of tooth-colored filling materials that can be used to create temporary crowns [ 11 ]. Although less durable compared to some materials, composite resin crowns offer an esthetically pleasing alternative [ 12 , 13 ].

The choice of crown material is based on a concerted decision between the dentist and patient, considering oral health, specific tooth requirements, and personal esthetic preferences [ 14 ]. This approach allows the operator to customize the treatment for each individual patient so that the selected crown material is tailored to their own individual requirements and contributes to the functional and esthetic requirements [ 4 ]. Yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) and alumina are two types of ceramics that are frequently used to make ceramic dental crowns, with their own advantages for application in dentistry [ 15 , 16 ].

The main component of YSZ is zirconium oxide (ZrO2), which is used with yttrium oxide (Y2O3) as the stabilizing agent [ 17 ]. Yttrium is added to prevent the transformation from a tetragonal to monoclinic crystal structure, thus improving its mechanical properties [ 18 ]. YSZ has excellent strength, toughness, and hardness and is a viable material for dental crowns. Its high fracture resistance protects the crown from chipping or cracking and is biocompatible with the oral environment [ 19 ]. In terms of esthetics, YSZ can be matched in color to more natural teeth, and additional translucency adds to the more natural appearance of restorations. It is suitable for both anterior and posterior teeth [ 20 ].

Alumina crowns, in contrast, are largely made of aluminum oxide (aluminum trioxide or Al 6 2O 3 ), which is a ceramic that is well known for its hardness and resistance to wear [ 21 ]. Alumina exhibits notable hardness and wear resistance that contribute to its durability [ 22 , 23 ]. It has excellent biocompatibility with oral tissues and can be made to match the color of natural teeth; while it is less translucent than YSZ, the esthetics of alumina crowns are continuously improved through material processing [ 24 ]. Alumina crowns are commonly used for anterior teeth where esthetics are a primary concern, and they may be chosen for cases where wear resistance is a key consideration [ 25 , 26 ]. Yttrium-stabilized zirconia and alumina are suitable options for the production of esthetic dental crowns. The choice between the two materials depends on the location of the tooth, type of clinical requirement, and patient’s choice [ 27 ]. These ceramics continue to evolve as new advancements in material science become available to the dental profession, which ultimately allows dentists to provide optimized functional and esthetic outcomes in restorative dentistry [ 28 , 29 ].

In this study, we comprehensively analyzed the mechanical properties, Density of states (DOS), integrated DOS, band structures, optical properties, and stress properties of yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) and alumina, specifically in the context of their application in esthetic dental crowns. The calculations were based on the computational approach of the CASTEP (Cambridge Serial Total Energy Package) code. The results were verified to provide ideas regarding the structural, electronic, and optical parameters of these materials and to identify their potential usefulness in esthetic crown applications.

Material and methodology

The Cambridge Serial Total Energy Package (CASTEP) code [ 30 , 31 ], utilizing a first-principles approach grounded in density functional theory (DFT), was employed to calculate the ground-state energy of the materials. The generalized gradient approximation (GGA) within the Perdew (Burke) Ernzerhof scheme was used to evaluate the electronic exchange–correlation energy. Vanderbilt-type norm-conserving pseudopotentials, along with a Koelling–Harmon relativistic treatment, were applied to represent the interaction between the valence electrons and ion cores. This pseudopotential selection balances the computational efficiency with the accuracy [ 32 , 33 ]. The valence electron configurations considered were 1s 2 2s 2 2p 4 for 0, 1s 2 2s 2 2p 6 3s 2 3p 1 for Al in alumina, and 1s 2 2s 2 2p 6 3s 2 3p 6 3d 10 4s 2 4p 6 4d 1 5s 2 for Y and 1s 2 2s 2 2p 6 3s 2 3p 6 3d 10 4s 2 4p 6 4d 2 5s 2 for zirconia in YSZ.

Geometry optimization for yttrium-stabilized zirconia and alumina was performed using the limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno (LBFGS) minimization scheme to achieve the lowest energy structure. A plane-wave cutoff energy of 500 eV for alumina and 625 eV for YSZ was used for the expansion. Brillouin zone (BZ) integration was conducted using the Monkhorst–Pack method, employing the k-point for alumina (3 × 3 × 1) and YSZ (2 × 2 × 2). The geometry optimization employed convergence tolerances of 10 -4 eV/atom for total energy, 10 -2 Å for maximum lattice point displacement, 0.03 eV Å -1 for maximum ionic Hellmann–Feynman force, and 0.05 GPa for maximum stress tolerance. To guarantee accurate structural, elastic, and electronic band structure property estimates while preserving the computational efficiency, finite basis set modifications were used.

Results and discussion

Structural properties.

The structural properties of alumina were determined through a geometry optimization process employing the LBFGS (limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno) minimization scheme [ 34 ]. The optimization involved an unbounded number of LBFGS updates with a preconditioned LBFGS activated using an exponential (EXP) stabilization constant of 0.1000 and a parameter A value of 3.0000. The real lattice parameters were a = 4.759 Å, b = 4.759 Å, and c = 12.991 Å, with corresponding cell angles of α = 90.000°, β = 90.000°, and γ = 120.000°. The current volume of the unit cell was calculated as 254.803051 A 3 , resulting in a density of 2.400943 AMU/A 3 or 3.986860 g/cm 3 . The crystal system was identified as trigonal with a hexagonal geometry. The rhombohedral centers were determined to be at coordinates (0, 0, 0), (2/3, 1/3, 1/3), and (1/3, 2/3, 2/3), corresponding to crystal class – 3 m. Additionally, the LBFGS optimization results indicated a final enthalpy of − 9.29467617 × 10 3 eV, a final frequency of 543.62876 cm -1 , and a final bulk modulus of 220.64766 GPa. These optimization parameters, including the estimated bulk modulus and frequency, are crucial for obtaining the lowest-energy structure of alumina, providing insights into its stable geometric configuration and overall structural characteristics.

The structural properties of yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) were also investigated through geometry optimization using the LBFGS (limited-memory Broyden–Fletcher–Goldfarb–Shanno) minimization scheme. The optimization process utilized an unbounded number of LBFGS updates with an activated preconditioned LBFGS, employing an exponential (EXP) stabilization constant of 0.1000 and a parameter A value of 3.0000. The nearest-neighbor distance, cutoff distance, and parameter mu were determined automatically, whereas the variable cell method with a fixed basis quality was employed. The optimization comprised a maximum of 2 steps, with an estimated bulk modulus of 500.0 GPa and frequency of 1668 cm -1 . The real lattice parameters for the unit cell were identified as a = 5.154630 Å, b = 5.154630 Å, and c = 5.154630 Å, resulting in a cubic geometry with cell angles of α = 90.000°, β = 90.000°, and γ = 90.000°. The current cell volume was calculated as 136.959604 A 3 , resulting in a density of 30.452467 AMU/A 3 or 50.567510 g/cm 3 . The crystal system was characterized as cubic, the geometry was cubic, and the rhombohedral centers were specified at the coordinates (0,0,0). The crystal class was identified as 1, and the space group as P 1 with space number 1. The LBFGS optimization results indicated a final enthalpy of 4.89620241 × 10 5 eV, an unchanged final frequency value from the initial value, and a final bulk modulus of 117.20470 GPa. These findings offer insight into the stable geometric configuration, crystal structure, and overall structural properties of yttrium-stabilized zirconia.

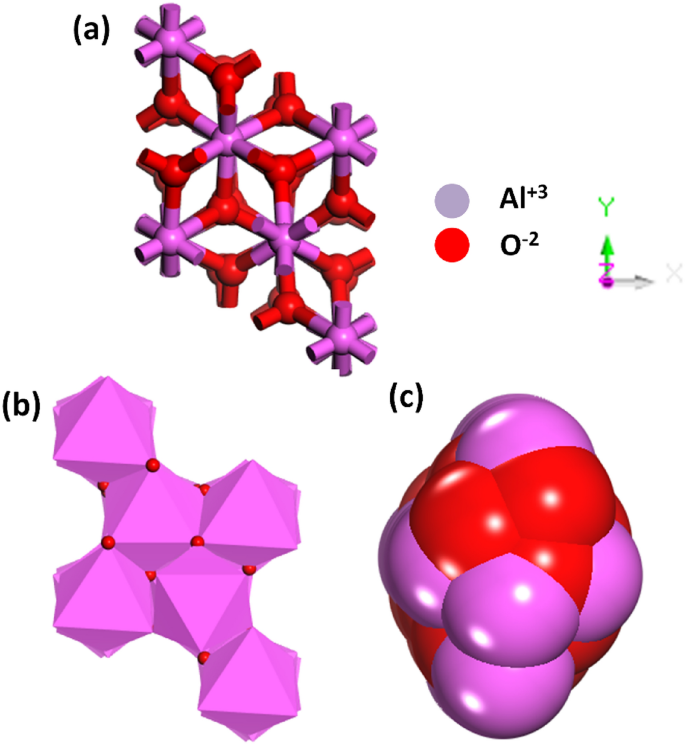

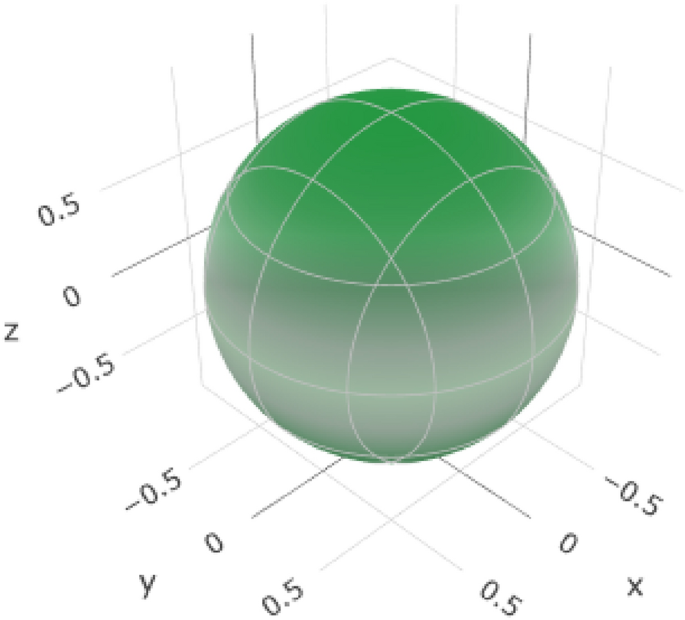

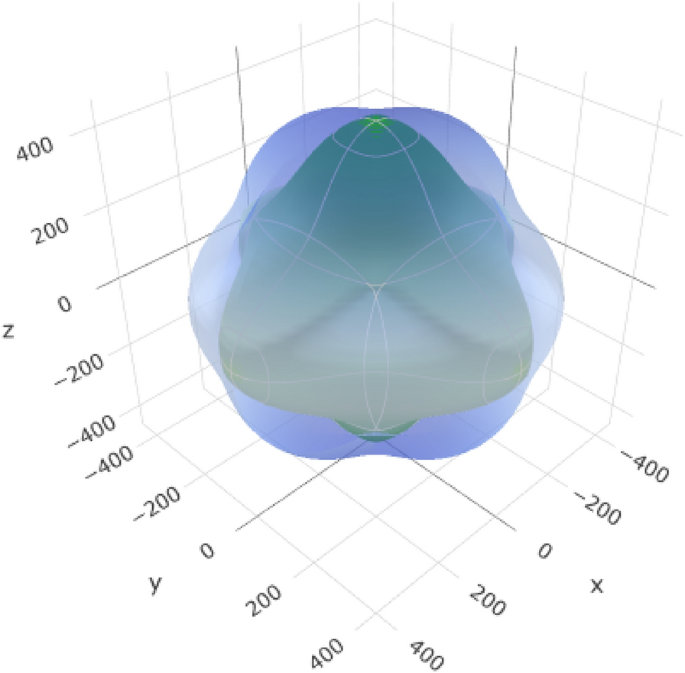

Figure 1 data offer insights into the geometry (Fig. 1 (a)), polyhedron (Fig. 1 (b)), and charge, kinetic, and potential (CKP) (Fig. 1 (c)) energy of alumina (Al 6 2O 3 ) having aluminum (Al) in the + 3 oxidation state and oxygen (O) in the − 2 oxidation state. In Fig. 1 (a), the unit cell of alumina exhibits the following lattice parameters: a = 4.759 Å, b = 4.759 Å, c = 12.991 Å, with angles α = β = 90° and γ = 120°. The current cell volume was 254.803051 Å 3 and the density was 2.400943 AMU/A 3 or 3.986860 g/cm 3 . The crystal structure was characterized as a supercell containing three primitive cells.

a Coordination environment, b polyhedron, and c charge, kinetics, and potential (CKP) of alumina

In crystallography, a polyhedron is a three-dimensional geometric shape formed by connecting neighboring atoms around a central atom. As shown in Fig. 1 (b), the crystal structures of alumina and aluminum atoms are typically surrounded by oxygen atoms, forming a coordination polyhedron around each aluminum center. In the polyhedron (Fig. 1 (b)), alumina comprises 30 ions distributed between two species, oxygen (O) and aluminum (Al). The highest number of species was 18. The fractional coordinates of the atoms were specified by detailing their positions within a unit cell. As shown in Fig. 1 (c), the potential energy density is influenced by the arrangement of the charged particles (nuclei and electrons). In alumina, the potential energy density is shaped by electrostatic interactions between the positively charged aluminum ions and negatively charged oxygen ions. The ionic character of Al–O bonds contributes to the potential energy landscape.

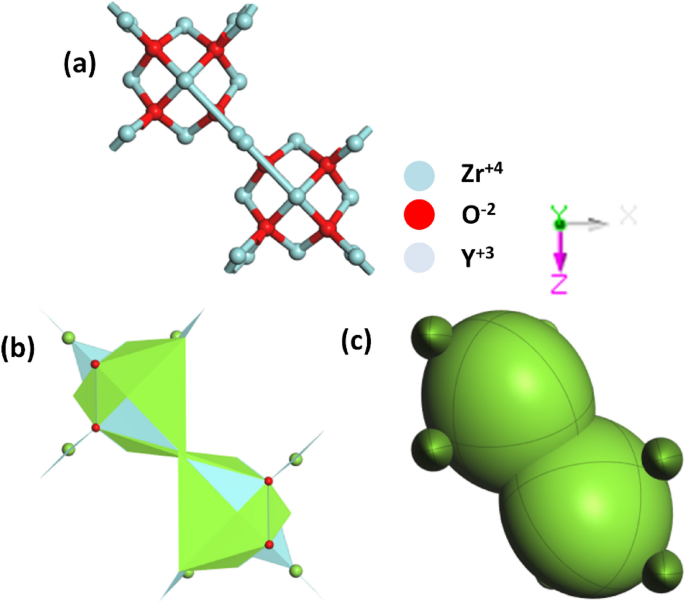

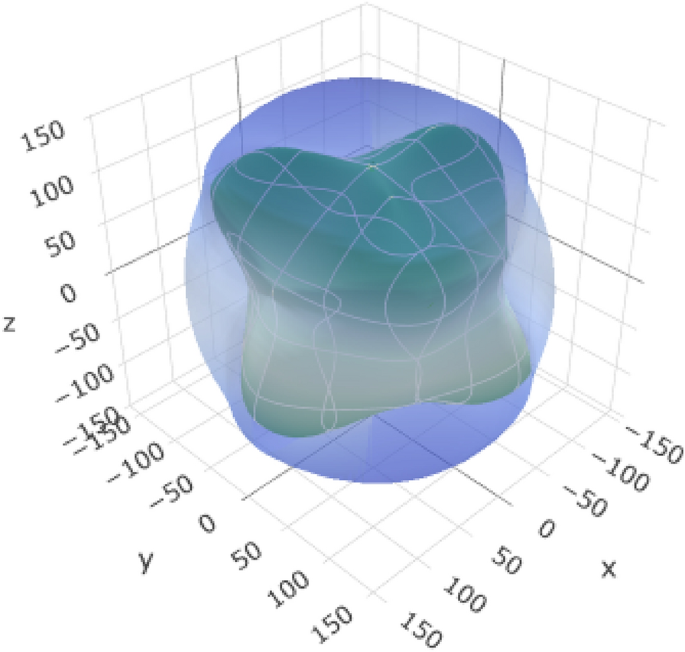

The crystal structure of yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) is described in terms of its unit cell parameters ( a = 5.154630 Å, b = 5.154630 Å, c = 5.154630 Å), as shown in Fig. 2 (a). The angles between the lattice vectors were all 90°( α = β = γ = 90°) with the same cubic crystal system geometry. The unit cells contained oxygen (O), yttrium (Y), and zirconium (Zr). In Fig. 2 (b), the polyhedron, in the context of crystallography, typically refers to a coordination polyhedron around a specific atom. In YSZ, the coordination polyhedra around Y, Zr, and O atoms depend on the crystal structure. For YSZ, the central atoms could be zirconium (Zr), yttrium (Y), or oxygen (O). The zirconium and yttrium atoms may exhibit polyhedral coordination with the surrounding oxygen atoms. Oxygen atoms typically form polyhedra around cationic species, such as Zr and Y. Ellipsoids are often associated with the electron density distribution around an atom. In the context of electronic structure calculations, an ellipsoidal representation of the charge density or electron cloud is used to describe the spatial distribution of the electrons. In Fig. 2 (c), the zirconium and yttrium atoms in yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) have associated ellipsoids that describe their thermal vibrations. These ellipsoids were centered at the average positions of the Zr and Y atoms.

a coordination environment, b polyhedron, and c ellipsoid geometry of Yttrium-Stabilized Zirconia (YSZ)

Optical properties and dynamic stability of alumina and yttrium-stabilized zirconia

Band structure.

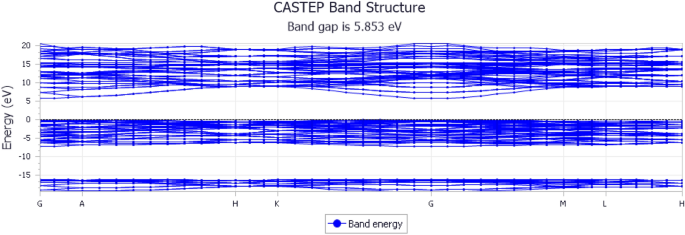

Figure 3 shows the band structure of alumina, which provides details of its electronic properties. The X-axis of the graph shows the high-symmetry points in the Brillouin zone. In this case, they are labeled as G, A, H, K, M, and L. These points correspond to definite crystallographic directions in the reciprocal lattice of the material. The broadening at the G and A points on the axis shown in Fig. 3 suggests the fanning out (dispersion) of the electronic states at the high-symmetry points. Therefore, this can indicate electronic transitions or electronic interactions occurring at G and A. The Y-axis gives the energy in electron volt (eV) units, which encompasses—− 20 to 20 eV, the energy level associated with the electronic states of the material.

Band structure of alumina

The band gap of alumina was 5.853 eV. The bandgap represents the energy difference between the top of the valence band and bottom of the conduction band. The band structure of alumina is crucial for understanding its electronic behavior. The wide bandgap of 5.853 eV [ 35 ] indicates that alumina is an insulating material, implying that it does not conduct electricity well. This property is desirable for applications such as esthetic crowns in dentistry. The insulating nature of alumina ensures that it does not interfere with electrical signals in the surrounding biological environment, making it suitable for use in dental crowns where electrical conductivity could be problematic. Overall, the band structure of alumina, with a significant band gap and specific broadening at high-symmetry points, supports its feasibility as a material for esthetic crowns, ensuring both electrical insulation and potentially favorable optical characteristics.

Moreover, the bandgap of alumina is a key factor in determining its stability. In general, materials with larger bandgaps are more stable. The bandgap represents the energy required to transition electrons from the valence to the conduction band. Alumina, which has a bandgap of 5.853 eV, is considered to have a relatively wide bandgap. A wide band gap indicates a large energy difference between the filled valence band and the empty conduction band. This large energy separation suggests that alumina is less prone to electron excitation and conductivity, making it an insulator. As an insulator, alumina is less likely to undergo spontaneous electron transitions, which contribute to its overall stability.

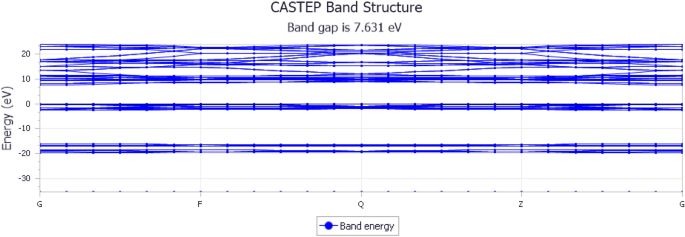

In contrast, in Fig. 4 , the Y-axis represents the energy values of the electronic bands in electron volts (eV). The range was—-15 to 15 eV. In any case, the x-axis is almost the same as the previous one. The bandgap of yttrium-stabilized zirconia was 7.631 eV [ 36 ]. The bandgap represents the energy difference between the valence and conduction bands. A larger bandgap indicates a better insulation. Moreover, materials with larger bandgaps are more stable. Yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) is known for its high strength and resistance to fracture, making it a popular choice for dental ceramics, especially for esthetic crowns.

Band structure graph of Yttrium-Stabilized Zirconia

Refractive index

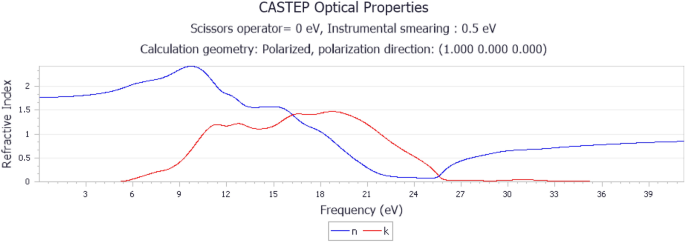

The refractive index ( n ) of a material is a dimensionless quantity that provides a quantitative description of the bending or refraction of light as it enters a material from a different medium. The refractive index is often represented as (n + i k), where ( n ) is the real part and ( k ) is the imaginary part. The real part of the refractive index (n) describes how much the speed of light in the material is lowered with respect to the speed of light in vacuum. The positive values of ( n ) imply that the material is one in which the speed of light is attenuated. The imaginary part of the refractive index ( k ) is part of the optical index, which is directly related to the absorption or attenuation of light in the material.

The real part of the refractive index, the upward trend at 9 eV in Fig. 5 , suggests an increase in the refractive index, indicating increased slowing of light at this point. The downward trend at 24 Hz indicated a decrease in the refractive index, suggesting a reduction in the slowing of light. The imaginary part of the refractive index, the broadening from to the 6–24 frequency in the ( k ) values, indicates increased absorption or attenuation of light in this frequency range.

Refractive index of alumina

The refractive index is an important parameter in optical materials used for esthetic crown applications [ 37 ]. The positive values of ( n ) suggest that alumina can influence the speed of light, which is relevant for optical applications. The absorption indicated by ( k ) values may need to be considered, especially in esthetic applications where light transmission and appearance are crucial. Controlling the absorption properties is vital in esthetic crowns to prevent unwanted color distortions and to ensure that the crown appears natural.

The refractive index is directly associated with the dispersion of light. Achieving a harmonious color match with natural teeth requires careful control of the refractive index, particularly in the context of the broadening observed in the given frequency range. Figure 5 presents an overview of the optical behavior of alumina. The consistency of the refractive index and its response to light is critical for ensuring the optical clarity and esthetically pleasing appearance of an esthetic crown.

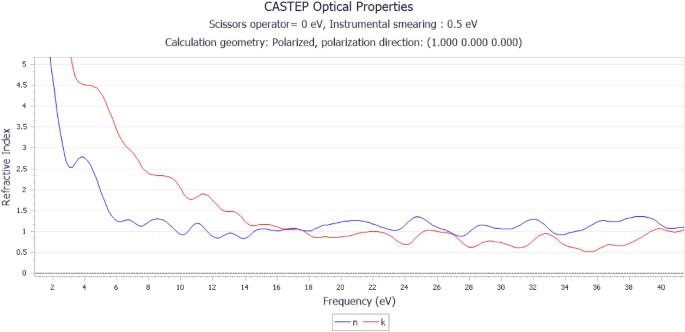

On the other hand, the refractive-index graph in Fig. 6 for yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) provides essential information about its optical properties, shedding light on its suitability for esthetic crown. The constant value of the refractive index ( n ) in the range of 6–18 frequency indicates that YSZ maintains a consistent optical behavior within this frequency range. This consistency is beneficial for achieving uniform optical properties in esthetic crowns. The sharp decrease from 5 to 1 on the y-axis suggests a substantial change in the refractive index, which may have implications for light transmission and color perception. The subsequent upward trend to 1.5 indicates a recovery in the refractive index. The sharp downward trend in the imaginary part of the refractive index ( k ) up to 10 eV indicates low light absorption within this frequency range. This is advantageous for esthetic crowns, as it suggests minimal color distortion due to absorption. The subsequent stabilization and slight upward trend of ( k ) beyond 10 eV indicate controlled absorption properties, contributing to the stability and color accuracy of the material. A constant refractive index within certain frequency ranges is desirable for achieving optical clarity and maintaining a natural appearance in esthetic crowns. The controlled absorption properties indicated by ( k ) contribute to the prevention of unwanted color distortions, ensuring that the crown closely matches natural teeth. The consistent refractive index values and controlled absorption properties suggest the stability of the optical performance of the YSZ. This is crucial for long-term durability and esthetic success of crown restorations.

Refractive index graph of Yttrium-Stabilized Zirconia

In comparison, alumina exhibits varying refractive index trends with absorption ( k ) in the observed frequency range. YSZ maintains a constant refractive index, indicating consistent optical behavior. YSZ exhibits better-controlled absorption, suggesting improved stability and color accuracy. The optical characteristics of YSZ make it a promising material for esthetic crown applications. In conclusion, yttrium-stabilized zirconia exhibits more desirable optical characteristics than alumina, making it a potentially superior material for esthetic crown applications, owing to its stable refractive index and controlled absorption properties.

- Mechanical properties

Stiffness matrix of alumina and yttrium-stabilized zirconia

The elastic stiffness constants (Cij) [ 38 ] of alumina, represented in GPa, provide crucial information regarding the response of the material to the applied stress and deformation, as shown in Table 1 . The data in Table 1 for the elastic stiffness constants of alumina are presented for a 6 × 6 matrix.

The high elastic stiffness constants, particularly those of the diagonal elements (C11, C22, C33, C44, C55, and C66), suggest that alumina is mechanically stable and can withstand stress and deformation. Stability is a crucial factor in dental restorations because it ensures that the crown material can endure forces exerted during mastication without undergoing significant deformation. The off-diagonal terms (C12, C13, C23, C14, C15, C16, C24, C25, and C26) indicate the anisotropic nature of alumina. Anisotropy implies that the mechanical properties of a material vary with the direction. Anisotropic behavior is important in esthetic crowns, as it allows for tailored mechanical properties depending on the orientation of the crown and its interaction with surrounding teeth.

The elastic stiffness constants allow the material to resist wear and deformation, thereby enhancing the long-term durability of the dental restorations. The values in the matrix that contribute to the mechanical integrity of the alumina crown would permit its use for esthetic crowns that need to withstand a variety of mechanical stresses, and knowing the elastic stiffness constants becomes important when we consider the proper design and fabrication of an esthetic crown because these values will need to be able to predict how the material under study will deform to the ideal loading conditions in such a way that its performance will be optimized; on the other hand, the elastic stiffness constants (Cij) of yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ), also represented in GPa, are given in a 6 × 6 matrix in Table 2 .

The high values of the elastic stiffness constants, particularly those of the diagonal elements (C11, C22, C33, C44, C55, and C66), indicate that YSZ is mechanically stiff and exhibits excellent resistance to deformation under stress. High stiffness is advantageous in dental restorations because it contributes to the ability of the material to withstand forces exerted during biting and chewing. The diagonal terms of the matrix are identical, indicating isotropic behavior. Isotropy implies that the mechanical properties of the material are consistent in all the directions. Isotropic behavior simplifies the design and fabrication process for esthetic crowns, as the material responds uniformly to applied stress, ensuring predictable and reliable performance. The elastic stiffness constants influence the durability and resistance of the material to wear. YSZ’s stiffness of YSZ contributes to its ability to maintain its structural integrity over time, ensuring its long-term success as a dental restoration material. Understanding the elastic stiffness constants is crucial for designing esthetic crowns with precise mechanical properties. This enables dental professionals to tailor the material response to specific loading conditions and optimize the crown performance. While elastic stiffness is critical for mechanical performance, other factors, such as biocompatibility and esthetics, also play a role in the feasibility of YSZ for esthetic crowns. YSZ is known for its biocompatibility, and its natural color can contribute to visually appealing esthetic outcomes.

Comparing these values, YSZ has relatively higher values in its matrix than alumina, which means that YSZ is stiffer. In terms of the isotropic properties, the diagonal terms are the same for both values, indicating that they are isotropic. YSZ, which is stiffer, is more likely to have higher durability and resistance to deformation than alumina. Both materials offer precision in crown design owing to their isotropic behavior. The choice between them may depend on specific design requirements. This comparison indicates that YSZ generally has higher stiffness values, which may be advantageous in certain applications.

Average properties of alumina and yttrium-stabilized zirconia

The feasibility of alumina for esthetic crown applications is supported by its mechanical and optical properties derived from the average properties obtained through the Voigt, Reuss, and Hill averaging schemes listed in Table 3 .

The mechanical strength of a material is often characterized by parameters such as Young’s modulus ( E ), bulk modulus ( K ), and shear modulus ( G ). The Young’s modulus measures a material's stiffness, indicating how much it will deform under a given load. High values of the Young’s modulus imply that the material is stiff and resistant to deformation. A high Young’s modulus indicates that alumina can maintain its shape and resist bending or flexing, which is crucial for dental crowns subjected to biting and chewing forces. The bulk modulus is a measure of the resistance of a material to volume change under pressure. The high bulk modulus values indicate that the material was resistant to compression. In dental crowns that experience pressure from biting forces, a high bulk modulus is essential for maintaining the structural integrity of the crown and preventing undesirable changes in volume. The shear modulus measures the resistance of a material to deformation caused by shear stress. This represents the ability of a material to withstand the forces that act parallel to its surface. High shear modulus values imply that the material can resist shear forces, making it mechanically robust. In dental applications, resistance to shear force is crucial for the longevity and stability of crowns during mastication. The combination of the high Young's modulus and shear modulus values indicates that alumina can provide precise and stable crown fabrication. This is important for achieving an accurate fit and long-term durability of the dental crowns.

On the other hand, the average properties of yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) provide insights into its mechanical behavior in Table 4 , and these properties play a significant role in determining its feasibility as a material for esthetic crowns.

This averaging scheme provides an upper bound for the material properties. The high values of the bulk modulus (KV = 360.61 GPa), Young’s modulus (EV = 850.86 GPa), and shear modulus (GV = 384.39 GPa) indicate that YSZ is a stiff material with excellent resistance to deformation. This is advantageous for dental crowns because it suggests that YSZ can withstand forces associated with biting and chewing. This scheme provides a lower bound for the material properties. The values of the bulk modulus (KR = 360.61 GPa), Young's modulus (ER = 832.4 GPa), and shear modulus (GR = 373.18 GPa) obtained through Reuss averaging confirmed the stiffness and mechanical robustness of YSZ. The values of bulk modulus (KH = 360.61 GPa), Young’s modulus (EH = 841.66 GPa), and shear modulus (GH = 378.79 GPa) suggest that YSZ maintains a consistently high level of stiffness across the different averaging schemes.

The values of Poisson’s ratio obtained through different averaging schemes (νV = 0.10675, νR = 0.11528, νH = 0.111) suggest that YSZ has a relatively low Poisson’s ratio. A lower Poisson’s ratio is favorable for dental crowns because it indicates a lower susceptibility to deformation and better ability to maintain shape under stress. In general, the high stiffness, resistance to deformation, and low Poisson's ratio of YSZ, as indicated by its averaged properties, make it a feasible material for esthetic crowns.

In comparison, yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) exhibits a higher bulk modulus, Young's modulus, and shear modulus, along with a lower Poisson's ratio than alumina. These mechanical properties collectively suggest that YSZ is a stiffer and more resistant material, making it potentially more suitable for applications such as esthetic crowns, where mechanical strength and durability are crucial.

The eigenvalues of the stiffness matrix represent the natural frequencies at which a material vibrates when it is subjected to mechanical stimuli. In the context of alumina in Table 5 , the eigenvalues of its stiffness matrix (represented by λ1 to λ6) correspond to different modes of vibration and provide insights into its mechanical behavior.

The eigenvalues represent the stiffness or rigidity of alumina in different directions. Higher eigenvalues suggest higher stiffness in these specific directions, contributing to the overall stability of the material. The eigenvalues are associated with the natural frequencies of vibrations. Understanding these frequencies is crucial in applications where the material may be subjected to mechanical vibrations, ensuring that the material does not resonate or deform undesirably under specific loads.

In the context of esthetic crowns, the eigenvalues provide insights into how alumina responds to forces and stresses. Higher eigenvalues indicate a greater resistance to deformation, which is essential for maintaining the structural integrity of dental restorations.

On the other hand, in the context of yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ), the eigenvalues (λ1 to λ6) provide insights into its mechanical behavior and structural characteristics in Table 6 . Equal values of the first three eigenvalues (λ1, λ2, and λ3) indicate isotropic or uniform stiffness in those directions. This property is beneficial in dental applications where consistent material behavior is desired. The last three eigenvalues (λ4, λ5, and λ6) were higher, indicating an increased stiffness in specific directions. This anisotropic stiffness provides YSZ with tailored mechanical properties, making it suitable for applications in which strength and resistance to deformation are crucial.

Moreover, the higher eigenvalues in certain directions suggest that YSZ can effectively resist deformations and stresses. This durability is essential for esthetic crowns to ensure long-term performance without mechanical failure.

In contrast, the eigenvalues of the stiffness matrix highlight the mechanical differences between yttrium-stabilized zirconia and alumina. YSZ exhibits a more isotropic stiffness profile with a higher overall stiffness, making it suitable for applications that require enhanced mechanical properties, such as esthetic crowns in dentistry.

Elastic moduli of yttrium-stabilized zirconia and alumina

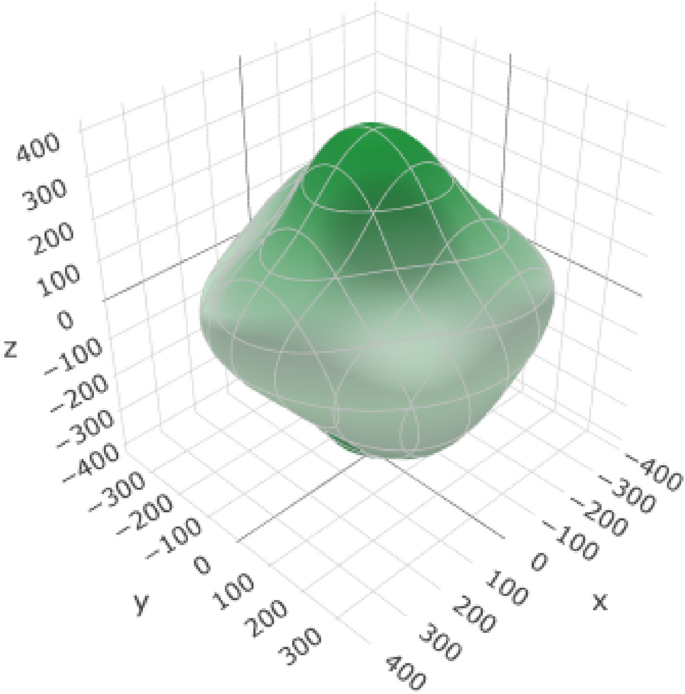

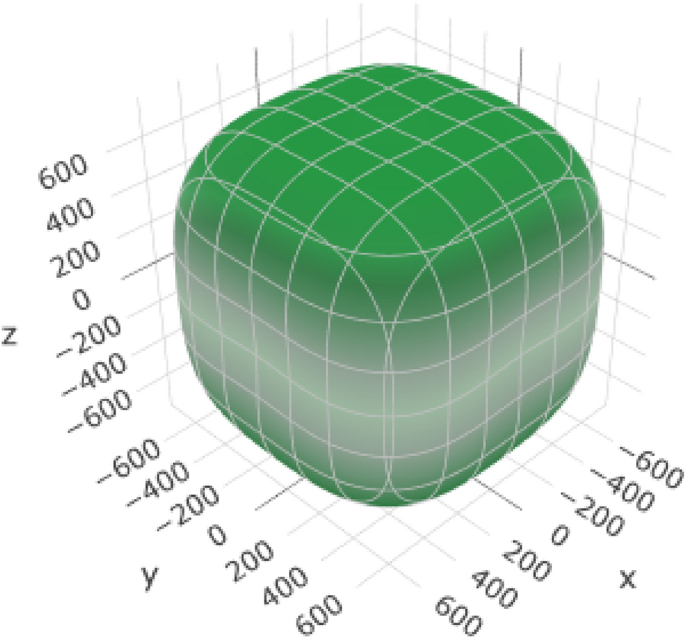

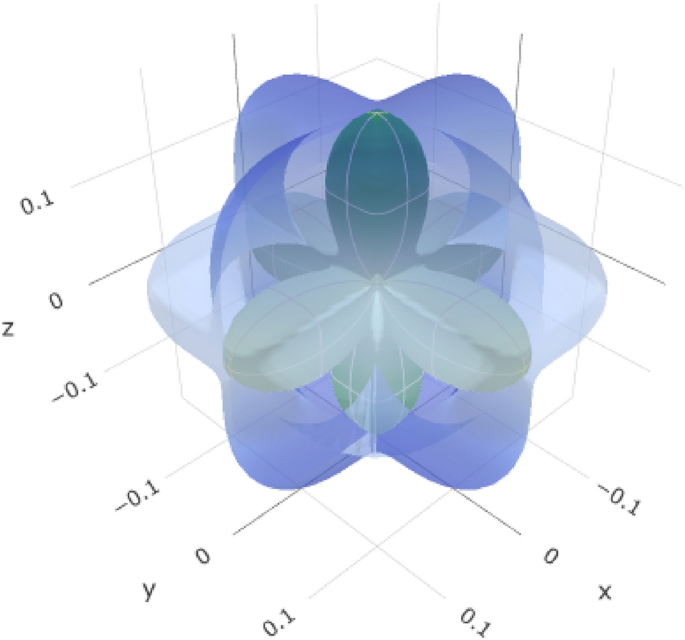

Table 7 provides information about the variations in the elastic moduli of alumina, including the Young's modulus (Fig. 7 and (Additional file 1 : Figure S1 for 2D representation), linear compressibility, shear modulus, and Poisson's ratio. These variations are crucial for understanding the response of the material to mechanical stress and play a significant role in the suitability of alumina for esthetic crown applications.

3D representation of Young’s modulus of alumina

The range from E min (266.16 GPa) to E max (399.71 GPa) represents the variation in Young's modulus. This variation describes the stiffness of the material and its ability to withstand deformation under an applied stress. An anisotropy value of 1.502 indicates that the stiffness of the material varied in different crystallographic directions.

The variation from β min (1.5841 TPa^–1) to β max (1.8125 TPa^–1) represents the linear compressibility of alumina (Fig. 8 and (Additional file 1 : Figure S2 for 2D representation). This property indicates that the material responds to compressive stress. Furthermore, the range from G min (103.75 GPa) to G max (173.38 GPa) represents the variation in the shear modulus (Fig. 9 and (Additional file 1 : Figure S3 for 2D representation). The shear modulus reflects the resistance of a material to deformation under shear stress. Moreover, the range from ν min (0.053073) to ν max (0.3787) represents the variation in Poisson’s ratio (Fig. 10 and (Additional file 1 : Figure S4 for 2D representation). This ratio describes the tendency of the material to contract laterally when longitudinally compressed.

3D representation of linear alumina compressibility

3D representation of the shear modulus of alumina

3D representation of Poisson’s ratio of alumina

The anisotropy values for each property indicate the extent to which the material varies in different crystallographic directions, and the axis values indicate the orientation of the crystallographic axes with respect to the measurement axes. Nonetheless, this anisotropy allows the stiffness of alumina to be tailored in different directions. For dental applications, crown materials must closely resemble the mechanical properties of the natural teeth. The anisotropy values and axis information are helpful during fabrication to orient the crown with respect to the optimized mechanical properties of the material for the given directions.

In conclusion, variations in the elastic moduli of alumina are vital for tailoring the mechanical properties of materials to meet the specific requirements of esthetic crown applications. These properties ensure that the crown exhibits appropriate stiffness, deformation response, and dimensional stability, thereby contributing to the overall success of the dental restorations.

However, variations in the elastic moduli of yttrium-stabilized zirconia (YSZ) are important for esthetic crown applications for several reasons.

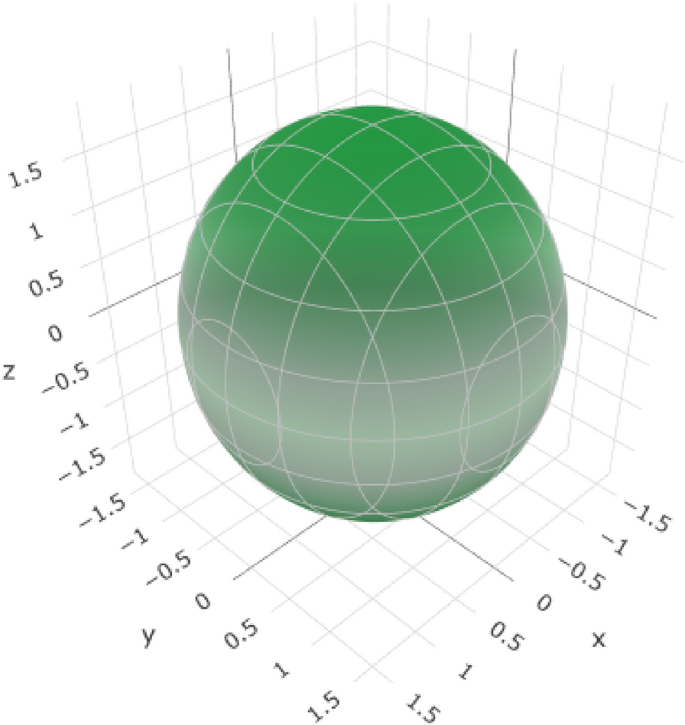

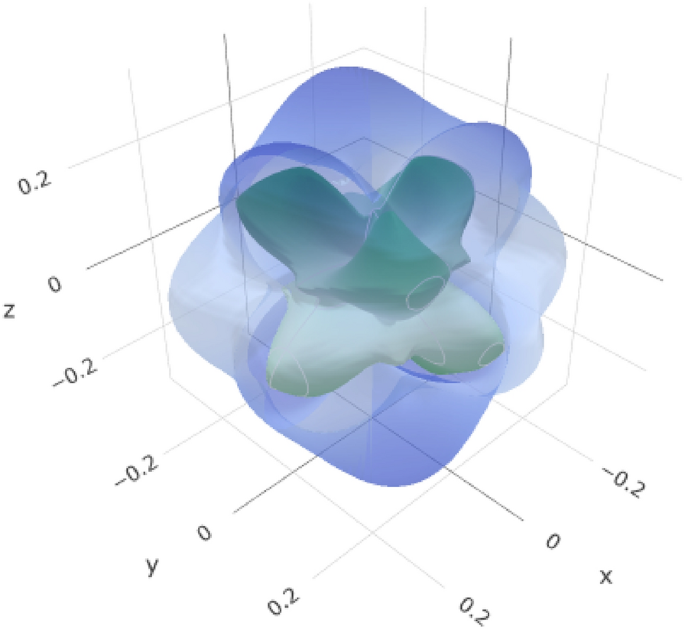

Young’s modulus ( E ) represents the stiffness of the material (Table 8 , Fig. 11 , and (Figure S5 for the 2D representation). The variation from E min (716.92 GPa) to E max (932.53 GPa) allows for controlled stiffness in different directions. This is crucial for mimicking the mechanical behavior of natural teeth and ensuring that the esthetic crown exhibits an appropriate level of rigidity.

3D representation of Young’s modulus of Yttrium-Stabilized Zirconia

The constant values of linear compressibility ( β min and β max at 0.92437 TPa^–1) indicate a consistent response to compressive stress (Fig. 12 and (Additional file 1 : Figure S6 for 2D representation). In esthetic crown applications, where the material may experience compressive forces during biting and chewing, predictable linear compressibility is essential for stability and reliability.

3D representation of the linear compressibility of Yttrium-Stabilized Zirconia

The variation in shear modulus ( G min to G max from 306.73 GPa to 436.17 GPa) reflects YSZ's ability to resist deformation under shear stress (Fig. 13 and (Additional file 1 : Figure S7 for 2D representation). This property is critical for ensuring that the esthetic crown maintains its structural integrity, especially in areas where shear forces are applied during mastication.

3D representation of the shear modulus of Yttrium-Stabilized Zirconia

The range of Poisson's ratio values ( ν min to ν max from − 0.0057521 to 0.20403) provides insights into the response of YSZ to longitudinal compression (Fig. 14 and (Additional file 1 : Figure S8 for 2D representation). Understanding the lateral contraction behavior is vital for preventing dimensional changes and maintaining the stability of the esthetic crown. The anisotropy values and axis information help align the crown orientation with the optimal mechanical properties of YSZ in specific directions. This enables manufacturers to customize crown structures based on the anisotropic nature of materials.

3D representation of Poisson’s ratio of Yttrium-Stabilized Zirconia

Overall, these variations in elastic moduli allow tailoring of the mechanical properties of YSZ to meet the specific demands of esthetic crown applications. This material can be designed to provide the right balance between stiffness, compressibility, shear resistance, and dimensional stability, thereby ensuring the long-term success and functionality of dental restorations. YSZ generally exhibits higher Young’s modulus, shear modulus, and anisotropy values than alumina.