10 min read

How to write strong essay body paragraphs (with examples)

In this blog post, we'll discuss how to write clear, convincing essay body paragraphs using many examples. We'll also be writing paragraphs together. By the end, you'll have a good understanding of how to write a strong essay body for any topic.

Table of Contents

Introduction, how to structure a body paragraph, creating an outline for our essay body, 1. a strong thesis statment takes a stand, 2. a strong thesis statement allows for debate, 3. a strong thesis statement is specific, writing the first essay body paragraph, how not to write a body paragraph, writing the second essay body paragraph.

After writing a great introduction to our essay, let's make our case in the body paragraphs. These are where we will present our arguments, back them up with evidence, and, in most cases, refute counterarguments. Introductions are very similar across the various types of essays. For example, an argumentative essay's introduction will be near identical to an introduction written for an expository essay. In contrast, the body paragraphs are structured differently depending on the type of essay.

In an expository essay, we are investigating an idea or analyzing the circumstances of a case. In contrast, we want to make compelling points with an argumentative essay to convince readers to agree with us.

The most straightforward technique to make an argument is to provide context first, then make a general point, and lastly back that point up in the following sentences. Not starting with your idea directly but giving context first is crucial in constructing a clear and easy-to-follow paragraph.

How to ideally structure a body paragraph:

- Provide context

- Make your thesis statement

- Support that argument

Now that we have the ideal structure for an argumentative essay, the best step to proceed is to outline the subsequent paragraphs. For the outline, we'll be writing one sentence that is simple in wording and describes the argument that we'll make in that paragraph concisely. Why are we doing that? An outline does more than give you a structure to work off of in the following essay body, thereby saving you time. It also helps you not to repeat yourself or, even worse, to accidentally contradict yourself later on.

While working on the outline, remember that revising your initial topic sentences is completely normal. They do not need to be flawless. Starting the outline with those thoughts can help accelerate writing the entire essay and can be very beneficial in avoiding writer's block.

For the essay body, we'll be proceeding with the topic we've written an introduction for in the previous article - the dangers of social media on society.

These are the main points I would like to make in the essay body regarding the dangers of social media:

Amplification of one's existing beliefs

Skewed comparisons

What makes a polished thesis statement?

Now that we've got our main points, let's create our outline for the body by writing one clear and straightforward topic sentence (which is the same as a thesis statement) for each idea. How do we write a great topic sentence? First, take a look at the three characteristics of a strong thesis statement.

Consider this thesis statement:

'While social media can have some negative effects, it can also be used positively.'

What stand does it take? Which negative and positive aspects does the author mean? While this one:

'Because social media is linked to a rise in mental health problems, it poses a danger to users.'

takes a clear stand and is very precise about the object of discussion.

If your thesis statement is not arguable, then your paper will not likely be enjoyable to read. Consider this thesis statement:

'Lots of people around the globe use social media.'

It does not allow for much discussion at all. Even if you were to argue that more or fewer people are using it on this planet, that wouldn't make for a very compelling argument.

'Although social media has numerous benefits, its various risks, including cyberbullying and possible addiction, mostly outweigh its benefits.'

Whether or not you consider this statement true, it allows for much more discussion than the previous one. It provides a basis for an engaging, thought-provoking paper by taking a position that you can discuss.

A thesis statement is one sentence that clearly states what you will discuss in that paragraph. It should give an overview of the main points you will discuss and show how these relate to your topic. For example, if you were to examine the rapid growth of social media, consider this thesis statement:

'There are many reasons for the rise in social media usage.'

That thesis statement is weak for two reasons. First, depending on the length of your essay, you might need to narrow your focus because the "rise in social media usage" can be a large and broad topic you cannot address adequately in a few pages. Secondly, the term "many reasons" is vague and does not give the reader an idea of what you will discuss in your paper.

In contrast, consider this thesis statement:

'The rise in social media usage is due to the increasing popularity of platforms like Facebook and Twitter, allowing users to connect with friends and share information effortlessly.'

Why is this better? Not only does it abide by the first two rules by allowing for debate and taking a stand, but this statement also narrows the subject down and identifies significant reasons for the increasing popularity of social media.

In conclusion : A strong thesis statement takes a clear stand, allows for discussion, and is specific.

Let's make use of how to write a good thopic sentence and put it into practise for our two main points from before. This is what good topic sentences could look like:

Echo chambers facilitated by social media promote political segregation in society.

Applied to the second argument:

Viewing other people's lives online through a distorted lens can lead to feelings of envy and inadequacy, as well as unrealistic expectations about one's life.

These topic sentences will be a very convenient structure for the whole body of our essay. Let's build out the first body paragraph, then closely examine how we did it so you can apply it to your essay.

Example: First body paragraph

If social media users mostly see content that reaffirms their existing beliefs, it can create an "echo chamber" effect. The echo chamber effect describes the user's limited exposure to diverse perspectives, making it challenging to examine those beliefs critically, thereby contributing to society's political polarization. This polarization emerges from social media becoming increasingly based on algorithms, which cater content to users based on their past interactions on the site. Further contributing to this shared narrative is the very nature of social media, allowing politically like-minded individuals to connect (Sunstein, 2018). Consequently, exposure to only one side of the argument can make it very difficult to see the other side's perspective, marginalizing opposing viewpoints. The entrenchment of one's beliefs by constant reaffirmation and amplification of political ideas results in segregation along partisan lines.

Sunstein, C. R (2018). #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

In the first sentence, we provide context for the argument that we are about to make. Then, in the second sentence, we clearly state the topic we are addressing (social media contributing to political polarization).

Our topic sentence tells readers that a detailed discussion of the echo chamber effect and its consequences is coming next. All the following sentences, which make up most of the paragraph, either a) explain or b) support this point.

Finally, we answer the questions about how social media facilitates the echo chamber effect and the consequences. Try implementing the same structure in your essay body paragraph to allow for a logical and cohesive argument.

These paragraphs should be focused, so don't incorporate multiple arguments into one. Squeezing ideas into a single paragraph makes it challenging for readers to follow your reasoning. Instead, reserve each body paragraph for a single statement to be discussed and only switch to the next section once you feel that you thoroughly explained and supported your topic sentence.

Let's look at an example that might seem appropriate initially but should be modified.

Negative example: Try identifying the main argument

Over the past decade, social media platforms have become increasingly popular methods of communication and networking. However, these platforms' algorithmic nature fosters echo chambers or online spaces where users only encounter information that reinforces their existing beliefs. This echo chamber effect can lead to a lack of understanding or empathy for those with different perspectives and can even amplify the effects of confirmation bias. The same principle of one-sided exposure to opinions can be abstracted and applied to the biased subjection to lifestyles we see on social media. The constant exposure to these highly-curated and often unrealistic portrayals of other people's lives can lead us to believe that our own lives are inadequate in comparison. These feelings of inadequacy can be especially harmful to young people, who are still developing their sense of self.

Let's analyze this essay paragraph. Introducing the topic sentence by stating the social functions of social media is very useful because it provides context for the following argument. Naming those functions in the first sentence also allows for a smooth transition by contrasting the initial sentence ("However, ...") with the topic sentence. Also, the topic sentence abides by our three rules for creating a strong thesis statement:

- Taking a clear stand: algorithms are substantial contributors to the echo chamber effect

- Allowing for debate: there is literature rejecting this claim

- Being specific: analyzing a specific cause of the effect (algorithms).

So, where's the problem with this body paragraph?

It begins with what seems like a single argument (social media algorithms contributing to the echo chamber effect). Yet after addressing the consequences of the echo-chamber effect right after the thesis sentence, the author applies the same principle to a whole different topic. At the end of the paragraph, the reader is probably feeling confused. What was the paragraph trying to achieve in the first place?

We should place the second idea of being exposed to curated lifestyles in a separate section instead of shoehorning it into the end of the first one. All sentences following the thesis statement should either explain it or provide evidence (refuting counterarguments falls into this category, too).

With our first body paragraph done and having seen an example of what to avoid, let's take the topic of being exposed to curated lifestyles through social media and construct a separate body paragraph for it. We have already provided sufficient context for the reader to follow our argument, so it is unnecessary for this particular paragraph.

Body paragraph 2

Another cause for social media's destructiveness is the users' inclination to only share the highlights of their lives on social media, consequently distorting our perceptions of reality. A highly filtered view of their life leads to feelings of envy and inadequacy, as well as a distorted understanding of what is considered ordinary (Liu et al., 2018). In addition, frequent social media use is linked to decreased self-esteem and body satisfaction (Perloff, 2014). One way social media can provide a curated view of people's lives is through filters, making photos look more radiant, shadier, more or less saturated, and similar. Further, editing tools allow people to fundamentally change how their photos and videos look before sharing them, allowing for inserting or removing certain parts of the image. Editing tools give people considerable control over how their photos and videos look before sharing them, thereby facilitating the curation of one's online persona.

Perloff, R.M. Social Media Effects on Young Women's Body Image Concerns: Theoretical Perspectives and an Agenda for Research. Sex Roles 71, 363–377 (2014).

Liu, Hongbo & Wu, Laurie & Li, Xiang. (2018). Social Media Envy: How Experience Sharing on Social Networking Sites Drives Millennials' Aspirational Tourism Consumption. Journal of Travel Research. 58. 10.1177/0047287518761615.

Dr. Jacob Neumann put it this way in his book A professors guide to writing essays: 'If you've written strong and clear topic sentences, you're well on your way to creating focused paragraphs.'

They provide the basis for each paragraph's development and content, allowing you not to get caught up in the details and lose sight of the overall objective. It's crucial not to neglect that step. Apply these principles to your essay body, whatever the topic, and you'll set yourself up for the best possible results.

Sources used for creating this article

- Writing a solid thesis statement : https://www.vwu.edu/academics/academic-support/learning-center/pdfs/Thesis-Statement.pdf

- Neumann, Jacob. A professor's guide to writing essays. 2016.

Follow the Journey

Hello! I'm Josh, the founder of Wordful. We aim to make a product that makes writing amazing content easy and fun. Sign up to gain access first when Wordful goes public!

How to write an essay: Body

- What's in this guide

- Introduction

- Essay structure

- Additional resources

Body paragraphs

The essay body itself is organised into paragraphs, according to your plan. Remember that each paragraph focuses on one idea, or aspect of your topic, and should contain at least 4-5 sentences so you can deal with that idea properly.

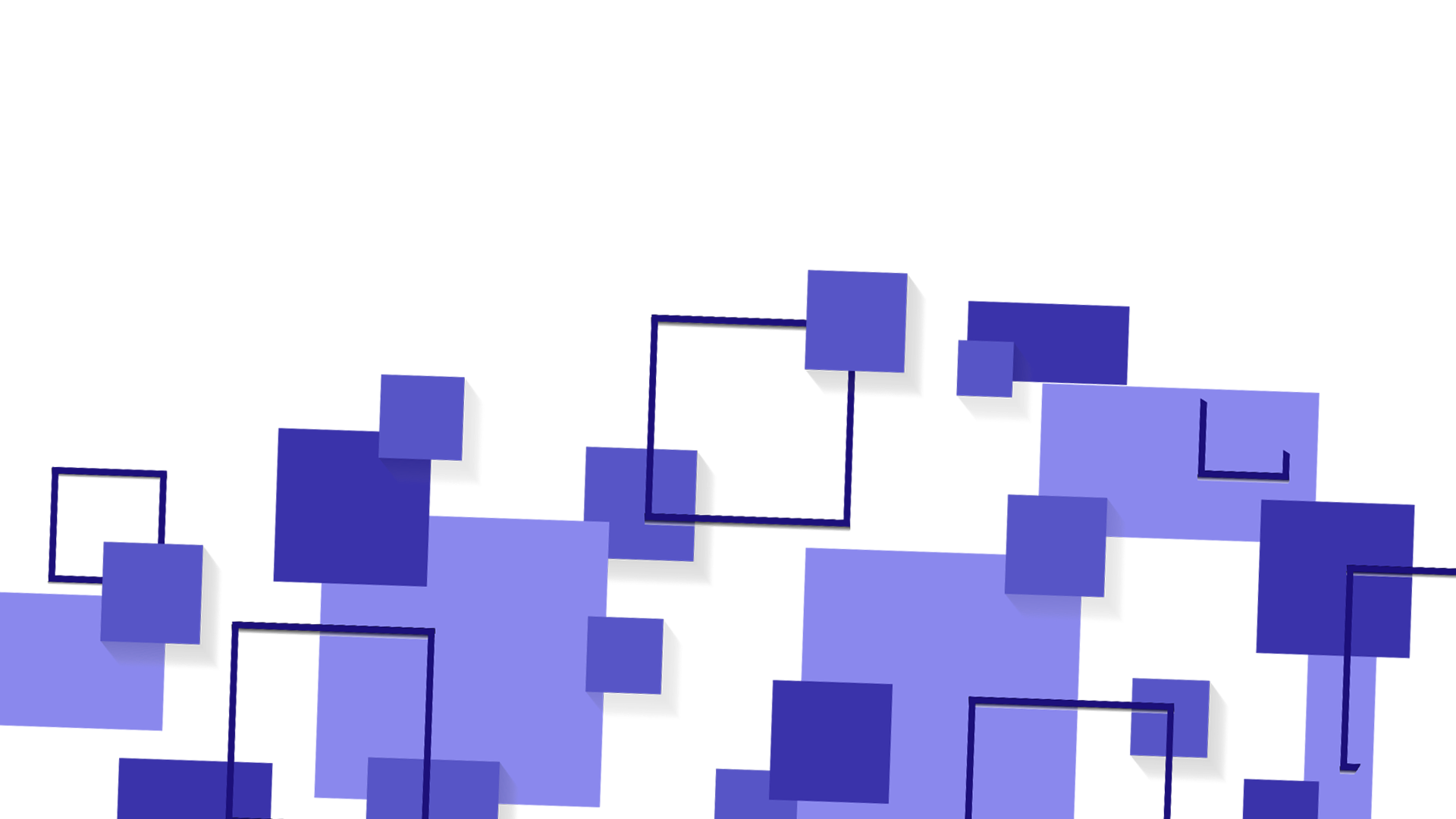

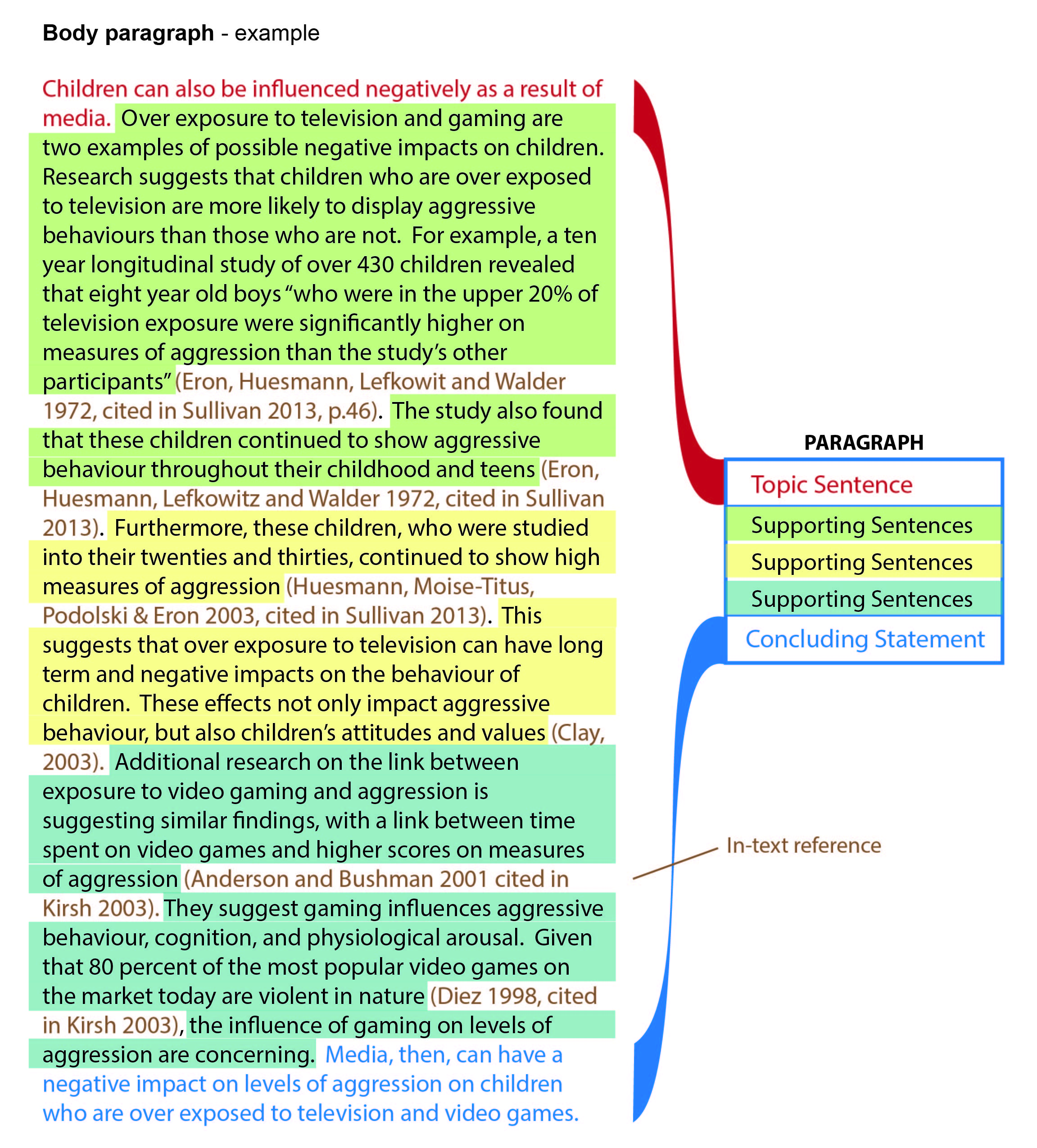

Each body paragraph has three sections. First is the topic sentence . This lets the reader know what the paragraph is going to be about and the main point it will make. It gives the paragraph’s point straight away. Next – and largest – is the supporting sentences . These expand on the central idea, explaining it in more detail, exploring what it means, and of course giving the evidence and argument that back it up. This is where you use your research to support your argument. Then there is a concluding sentence . This restates the idea in the topic sentence, to remind the reader of your main point. It also shows how that point helps answer the question.

Pathways and Academic Learning Support

- << Previous: Introduction

- Next: Conclusion >>

- Last Updated: Nov 29, 2023 1:55 PM

- URL: https://libguides.newcastle.edu.au/how-to-write-an-essay

Essay writing: Main body

- Introductions

- Conclusions

- Analysing questions

- Planning & drafting

- Revising & editing

- Proofreading

- Essay writing videos

Jump to content on this page:

“An appropriate use of paragraphs is an essential part of writing coherent and well-structured essays.” Don Shiach, How to write essays

The main body of your essay is where you deliver your argument . Its building blocks are well structured, academic paragraphs. Each paragraph is in itself an individual argument and when put together they should form a clear narrative that leads the reader to the inevitability of your conclusion.

The importance of the paragraph

A good academic paragraph is a special thing. It makes a clear point, backed up by good quality academic evidence, with a clear explanation of how the evidence supports the point and why the point is relevant to your overall argument which supports your position . When these paragraphs are put together with appropriate links, there is a logical flow that takes the reader naturally to your essay's conclusion.

As a general rule there should be one clear key point per paragraph , otherwise your reader could become overwhelmed with evidence that supports different points and makes your argument harder to follow. If you follow the basic structure below, you will be able to build effective paragraphs and so make the main body of your essay deliver on what you say it will do in your introduction.

Paragraph structure

- A topic sentence – what is the overall point that the paragraph is making?

- Evidence that supports your point – this is usually your cited material.

- Explanation of why the point is important and how it helps with your overall argument.

- A link (if necessary) to the next paragraph (or to the previous one if coming at the beginning of the paragraph) or back to the essay question.

This is a good order to use when you are new to writing academic essays - but as you get more accomplished you can adapt it as necessary. The important thing is to make sure all of these elements are present within the paragraph.

The sections below explain more about each of these elements.

The topic sentence (Point)

This should appear early in the paragraph and is often, but not always, the first sentence. It should clearly state the main point that you are making in the paragraph. When you are planning essays, writing down a list of your topic sentences is an excellent way to check that your argument flows well from one point to the next.

This is the evidence that backs up your topic sentence. Why do you believe what you have written in your topic sentence? The evidence is usually paraphrased or quoted material from your reading . Depending on the nature of the assignment, it could also include:

- Your own data (in a research project for example).

- Personal experiences from practice (especially for Social Care, Health Sciences and Education).

- Personal experiences from learning (in a reflective essay for example).

Any evidence from external sources should, of course, be referenced.

Explanation (analysis)

This is the part of your paragraph where you explain to your reader why the evidence supports the point and why that point is relevant to your overall argument. It is where you answer the question 'So what?'. Tell the reader how the information in the paragraph helps you answer the question and how it leads to your conclusion. Your analysis should attempt to persuade the reader that your conclusion is the correct one.

These are the parts of your paragraphs that will get you the higher marks in any marking scheme.

Links are optional but it will help your argument flow if you include them. They are sentences that help the reader understand how the parts of your argument are connected . Most commonly they come at the end of the paragraph but they can be equally effective at the beginning of the next one. Sometimes a link is split between the end of one paragraph and the beginning of the next (see the example paragraph below).

Paragraph structure video

Length of a paragraph

Academic paragraphs are usually between 200 and 300 words long (they vary more than this but it is a useful guide). The important thing is that they should be long enough to contain all the above material. Only move onto a new paragraph if you are making a new point.

Many students make their paragraphs too short (because they are not including enough or any analysis) or too long (they are made up of several different points).

Example of an academic paragraph

Using storytelling in educational settings can enable educators to connect with their students because of inborn tendencies for humans to listen to stories. Written languages have only existed for between 6,000 and 7,000 years (Daniels & Bright, 1995) before then, and continually ever since in many cultures, important lessons for life were passed on using the oral tradition of storytelling. These varied from simple informative tales, to help us learn how to find food or avoid danger, to more magical and miraculous stories designed to help us see how we can resolve conflict and find our place in society (Zipes, 2012). Oral storytelling traditions are still fundamental to native American culture and Rebecca Bishop, a native American public relations officer (quoted in Sorensen, 2012) believes that the physical act of storytelling is a special thing; children will automatically stop what they are doing and listen when a story is told. Professional communicators report that this continues to adulthood (Simmons, 2006; Stevenson, 2008). This means that storytelling can be a powerful tool for connecting with students of all ages in a way that a list of bullet points in a PowerPoint presentation cannot. The emotional connection and innate, almost hardwired, need to listen when someone tells a story means that educators can teach memorable lessons in a uniquely engaging manner that is common to all cultures.

This cross-cultural element of storytelling can be seen when reading or listening to wisdom tales from around the world...

Key: Topic sentence Evidence (includes some analysis) Analysis Link (crosses into next paragraph)

- << Previous: Introductions

- Next: Conclusions >>

- Last Updated: Nov 3, 2023 3:17 PM

- URL: https://libguides.hull.ac.uk/essays

- Login to LibApps

- Library websites Privacy Policy

- University of Hull privacy policy & cookies

- Website terms and conditions

- Accessibility

- Report a problem

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

9.2 Writing Body Paragraphs

Learning objectives.

- Select primary support related to your thesis.

- Support your topic sentences.

If your thesis gives the reader a roadmap to your essay, then body paragraphs should closely follow that map. The reader should be able to predict what follows your introductory paragraph by simply reading the thesis statement.

The body paragraphs present the evidence you have gathered to confirm your thesis. Before you begin to support your thesis in the body, you must find information from a variety of sources that support and give credit to what you are trying to prove.

Select Primary Support for Your Thesis

Without primary support, your argument is not likely to be convincing. Primary support can be described as the major points you choose to expand on your thesis. It is the most important information you select to argue for your point of view. Each point you choose will be incorporated into the topic sentence for each body paragraph you write. Your primary supporting points are further supported by supporting details within the paragraphs.

Remember that a worthy argument is backed by examples. In order to construct a valid argument, good writers conduct lots of background research and take careful notes. They also talk to people knowledgeable about a topic in order to understand its implications before writing about it.

Identify the Characteristics of Good Primary Support

In order to fulfill the requirements of good primary support, the information you choose must meet the following standards:

- Be specific. The main points you make about your thesis and the examples you use to expand on those points need to be specific. Use specific examples to provide the evidence and to build upon your general ideas. These types of examples give your reader something narrow to focus on, and if used properly, they leave little doubt about your claim. General examples, while they convey the necessary information, are not nearly as compelling or useful in writing because they are too obvious and typical.

- Be relevant to the thesis. Primary support is considered strong when it relates directly to the thesis. Primary support should show, explain, or prove your main argument without delving into irrelevant details. When faced with lots of information that could be used to prove your thesis, you may think you need to include it all in your body paragraphs. But effective writers resist the temptation to lose focus. Choose your examples wisely by making sure they directly connect to your thesis.

- Be detailed. Remember that your thesis, while specific, should not be very detailed. The body paragraphs are where you develop the discussion that a thorough essay requires. Using detailed support shows readers that you have considered all the facts and chosen only the most precise details to enhance your point of view.

Prewrite to Identify Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

Recall that when you prewrite you essentially make a list of examples or reasons why you support your stance. Stemming from each point, you further provide details to support those reasons. After prewriting, you are then able to look back at the information and choose the most compelling pieces you will use in your body paragraphs.

Choose one of the following working thesis statements. On a separate sheet of paper, write for at least five minutes using one of the prewriting techniques you learned in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

- Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

- Students cheat for many different reasons.

- Drug use among teens and young adults is a problem.

- The most important change that should occur at my college or university is ____________________________________________.

Select the Most Effective Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

After you have prewritten about your working thesis statement, you may have generated a lot of information, which may be edited out later. Remember that your primary support must be relevant to your thesis. Remind yourself of your main argument, and delete any ideas that do not directly relate to it. Omitting unrelated ideas ensures that you will use only the most convincing information in your body paragraphs. Choose at least three of only the most compelling points. These will serve as the topic sentences for your body paragraphs.

Refer to the previous exercise and select three of your most compelling reasons to support the thesis statement. Remember that the points you choose must be specific and relevant to the thesis. The statements you choose will be your primary support points, and you will later incorporate them into the topic sentences for the body paragraphs.

Collaboration

Please share with a classmate and compare your answers.

When you support your thesis, you are revealing evidence. Evidence includes anything that can help support your stance. The following are the kinds of evidence you will encounter as you conduct your research:

- Facts. Facts are the best kind of evidence to use because they often cannot be disputed. They can support your stance by providing background information on or a solid foundation for your point of view. However, some facts may still need explanation. For example, the sentence “The most populated state in the United States is California” is a pure fact, but it may require some explanation to make it relevant to your specific argument.

- Judgments. Judgments are conclusions drawn from the given facts. Judgments are more credible than opinions because they are founded upon careful reasoning and examination of a topic.

- Testimony. Testimony consists of direct quotations from either an eyewitness or an expert witness. An eyewitness is someone who has direct experience with a subject; he adds authenticity to an argument based on facts. An expert witness is a person who has extensive experience with a topic. This person studies the facts and provides commentary based on either facts or judgments, or both. An expert witness adds authority and credibility to an argument.

- Personal observation. Personal observation is similar to testimony, but personal observation consists of your testimony. It reflects what you know to be true because you have experiences and have formed either opinions or judgments about them. For instance, if you are one of five children and your thesis states that being part of a large family is beneficial to a child’s social development, you could use your own experience to support your thesis.

Writing at Work

In any job where you devise a plan, you will need to support the steps that you lay out. This is an area in which you would incorporate primary support into your writing. Choosing only the most specific and relevant information to expand upon the steps will ensure that your plan appears well-thought-out and precise.

You can consult a vast pool of resources to gather support for your stance. Citing relevant information from reliable sources ensures that your reader will take you seriously and consider your assertions. Use any of the following sources for your essay: newspapers or news organization websites, magazines, encyclopedias, and scholarly journals, which are periodicals that address topics in a specialized field.

Choose Supporting Topic Sentences

Each body paragraph contains a topic sentence that states one aspect of your thesis and then expands upon it. Like the thesis statement, each topic sentence should be specific and supported by concrete details, facts, or explanations.

Each body paragraph should comprise the following elements.

topic sentence + supporting details (examples, reasons, or arguments)

As you read in Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” , topic sentences indicate the location and main points of the basic arguments of your essay. These sentences are vital to writing your body paragraphs because they always refer back to and support your thesis statement. Topic sentences are linked to the ideas you have introduced in your thesis, thus reminding readers what your essay is about. A paragraph without a clearly identified topic sentence may be unclear and scattered, just like an essay without a thesis statement.

Unless your teacher instructs otherwise, you should include at least three body paragraphs in your essay. A five-paragraph essay, including the introduction and conclusion, is commonly the standard for exams and essay assignments.

Consider the following the thesis statement:

Author J.D. Salinger relied primarily on his personal life and belief system as the foundation for the themes in the majority of his works.

The following topic sentence is a primary support point for the thesis. The topic sentence states exactly what the controlling idea of the paragraph is. Later, you will see the writer immediately provide support for the sentence.

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced themes in many of his works.

In Note 9.19 “Exercise 2” , you chose three of your most convincing points to support the thesis statement you selected from the list. Take each point and incorporate it into a topic sentence for each body paragraph.

Supporting point 1: ____________________________________________

Topic sentence: ____________________________________________

Supporting point 2: ____________________________________________

Supporting point 3: ____________________________________________

Draft Supporting Detail Sentences for Each Primary Support Sentence

After deciding which primary support points you will use as your topic sentences, you must add details to clarify and demonstrate each of those points. These supporting details provide examples, facts, or evidence that support the topic sentence.

The writer drafts possible supporting detail sentences for each primary support sentence based on the thesis statement:

Thesis statement: Unleashed dogs on city streets are a dangerous nuisance.

Supporting point 1: Dogs can scare cyclists and pedestrians.

Supporting details:

- Cyclists are forced to zigzag on the road.

- School children panic and turn wildly on their bikes.

- People who are walking at night freeze in fear.

Supporting point 2:

Loose dogs are traffic hazards.

- Dogs in the street make people swerve their cars.

- To avoid dogs, drivers run into other cars or pedestrians.

- Children coaxing dogs across busy streets create danger.

Supporting point 3: Unleashed dogs damage gardens.

- They step on flowers and vegetables.

- They destroy hedges by urinating on them.

- They mess up lawns by digging holes.

The following paragraph contains supporting detail sentences for the primary support sentence (the topic sentence), which is underlined.

Salinger, a World War II veteran, suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder, a disorder that influenced the themes in many of his works. He did not hide his mental anguish over the horrors of war and once told his daughter, “You never really get the smell of burning flesh out of your nose, no matter how long you live.” His short story “A Perfect Day for a Bananafish” details a day in the life of a WWII veteran who was recently released from an army hospital for psychiatric problems. The man acts questionably with a little girl he meets on the beach before he returns to his hotel room and commits suicide. Another short story, “For Esmé – with Love and Squalor,” is narrated by a traumatized soldier who sparks an unusual relationship with a young girl he meets before he departs to partake in D-Day. Finally, in Salinger’s only novel, The Catcher in the Rye , he continues with the theme of posttraumatic stress, though not directly related to war. From a rest home for the mentally ill, sixteen-year-old Holden Caulfield narrates the story of his nervous breakdown following the death of his younger brother.

Using the three topic sentences you composed for the thesis statement in Note 9.18 “Exercise 1” , draft at least three supporting details for each point.

Thesis statement: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 1: ____________________________________________

Supporting details: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 2: ____________________________________________

Primary supporting point 3: ____________________________________________

You have the option of writing your topic sentences in one of three ways. You can state it at the beginning of the body paragraph, or at the end of the paragraph, or you do not have to write it at all. This is called an implied topic sentence. An implied topic sentence lets readers form the main idea for themselves. For beginning writers, it is best to not use implied topic sentences because it makes it harder to focus your writing. Your instructor may also want to clearly identify the sentences that support your thesis. For more information on the placement of thesis statements and implied topic statements, see Chapter 8 “The Writing Process: How Do I Begin?” .

Print out the first draft of your essay and use a highlighter to mark your topic sentences in the body paragraphs. Make sure they are clearly stated and accurately present your paragraphs, as well as accurately reflect your thesis. If your topic sentence contains information that does not exist in the rest of the paragraph, rewrite it to more accurately match the rest of the paragraph.

Key Takeaways

- Your body paragraphs should closely follow the path set forth by your thesis statement.

- Strong body paragraphs contain evidence that supports your thesis.

- Primary support comprises the most important points you use to support your thesis.

- Strong primary support is specific, detailed, and relevant to the thesis.

- Prewriting helps you determine your most compelling primary support.

- Evidence includes facts, judgments, testimony, and personal observation.

- Reliable sources may include newspapers, magazines, academic journals, books, encyclopedias, and firsthand testimony.

- A topic sentence presents one point of your thesis statement while the information in the rest of the paragraph supports that point.

- A body paragraph comprises a topic sentence plus supporting details.

Writing for Success Copyright © 2015 by University of Minnesota is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

- Departments and Units

- Majors and Minors

- LSA Course Guide

- LSA Gateway

Search: {{$root.lsaSearchQuery.q}}, Page {{$root.page}}

- Accessibility

- Undergraduates

- Instructors

- Alums & Friends

- ★ Writing Support

- Minor in Writing

- First-Year Writing Requirement

- Transfer Students

- Writing Guides

- Peer Writing Consultant Program

- Upper-Level Writing Requirement

- Writing Prizes

- International Students

- ★ The Writing Workshop

- Dissertation ECoach

- Fellows Seminar

- Dissertation Writing Groups

- Rackham / Sweetland Workshops

- Dissertation Writing Institute

- Guides to Teaching Writing

- Teaching Support and Services

- Support for FYWR Courses

- Support for ULWR Courses

- Writing Prize Nominating

- Alums Gallery

- Commencement Archive

- Giving Opportunities

- How Do I Write an Intro, Conclusion, & Body Paragraph?

- How Do I Make Sure I Understand an Assignment?

- How Do I Decide What I Should Argue?

- How Can I Create Stronger Analysis?

- How Do I Effectively Integrate Textual Evidence?

- How Do I Write a Great Title?

- What Exactly is an Abstract?

- How Do I Present Findings From My Experiment in a Report?

- What is a Run-on Sentence & How Do I Fix It?

- How Do I Check the Structure of My Argument?

- How Do I Incorporate Quotes?

- How Can I Create a More Successful Powerpoint?

- How Can I Create a Strong Thesis?

- How Can I Write More Descriptively?

- How Do I Incorporate a Counterargument?

- How Do I Check My Citations?

See the bottom of the main Writing Guides page for licensing information.

Traditional Academic Essays In Three Parts

Part i: the introduction.

An introduction is usually the first paragraph of your academic essay. If you’re writing a long essay, you might need 2 or 3 paragraphs to introduce your topic to your reader. A good introduction does 2 things:

- Gets the reader’s attention. You can get a reader’s attention by telling a story, providing a statistic, pointing out something strange or interesting, providing and discussing an interesting quote, etc. Be interesting and find some original angle via which to engage others in your topic.

- Provides a specific and debatable thesis statement. The thesis statement is usually just one sentence long, but it might be longer—even a whole paragraph—if the essay you’re writing is long. A good thesis statement makes a debatable point, meaning a point someone might disagree with and argue against. It also serves as a roadmap for what you argue in your paper.

Part II: The Body Paragraphs

Body paragraphs help you prove your thesis and move you along a compelling trajectory from your introduction to your conclusion. If your thesis is a simple one, you might not need a lot of body paragraphs to prove it. If it’s more complicated, you’ll need more body paragraphs. An easy way to remember the parts of a body paragraph is to think of them as the MEAT of your essay:

Main Idea. The part of a topic sentence that states the main idea of the body paragraph. All of the sentences in the paragraph connect to it. Keep in mind that main ideas are…

- like labels. They appear in the first sentence of the paragraph and tell your reader what’s inside the paragraph.

- arguable. They’re not statements of fact; they’re debatable points that you prove with evidence.

- focused. Make a specific point in each paragraph and then prove that point.

Evidence. The parts of a paragraph that prove the main idea. You might include different types of evidence in different sentences. Keep in mind that different disciplines have different ideas about what counts as evidence and they adhere to different citation styles. Examples of evidence include…

- quotations and/or paraphrases from sources.

- facts , e.g. statistics or findings from studies you’ve conducted.

- narratives and/or descriptions , e.g. of your own experiences.

Analysis. The parts of a paragraph that explain the evidence. Make sure you tie the evidence you provide back to the paragraph’s main idea. In other words, discuss the evidence.

Transition. The part of a paragraph that helps you move fluidly from the last paragraph. Transitions appear in topic sentences along with main ideas, and they look both backward and forward in order to help you connect your ideas for your reader. Don’t end paragraphs with transitions; start with them.

Keep in mind that MEAT does not occur in that order. The “ T ransition” and the “ M ain Idea” often combine to form the first sentence—the topic sentence—and then paragraphs contain multiple sentences of evidence and analysis. For example, a paragraph might look like this: TM. E. E. A. E. E. A. A.

Part III: The Conclusion

A conclusion is the last paragraph of your essay, or, if you’re writing a really long essay, you might need 2 or 3 paragraphs to conclude. A conclusion typically does one of two things—or, of course, it can do both:

- Summarizes the argument. Some instructors expect you not to say anything new in your conclusion. They just want you to restate your main points. Especially if you’ve made a long and complicated argument, it’s useful to restate your main points for your reader by the time you’ve gotten to your conclusion. If you opt to do so, keep in mind that you should use different language than you used in your introduction and your body paragraphs. The introduction and conclusion shouldn’t be the same.

- For example, your argument might be significant to studies of a certain time period .

- Alternately, it might be significant to a certain geographical region .

- Alternately still, it might influence how your readers think about the future . You might even opt to speculate about the future and/or call your readers to action in your conclusion.

Handout by Dr. Liliana Naydan. Do not reproduce without permission.

- Information For

- Prospective Students

- Current Students

- Faculty and Staff

- Alumni and Friends

- More about LSA

- How Do I Apply?

- LSA Opportunity Hub

- LSA Magazine

- Student Resources

- Academic Advising

- Global Studies

- Social Media

- Update Contact Info

- Privacy Statement

- Report Feedback

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

3.3: Body Paragraphs

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 20298

- Ann Inoshita, Karyl Garland, Kate Sims, Jeanne K. Tsutsui Keuma, and Tasha Williams

- University of Hawaii via University of Hawaiʻi OER

If the thesis is the roadmap for the essay, then body paragraphs should closely follow that map. The reader should be able to predict what follows an introductory paragraph by simply reading the thesis statement. The body paragraphs present the evidence the reader has gathered to support the overall thesis. Before writers begin to support the thesis within the body paragraphs, they should find information from a variety of sources that support the topic.

Select Primary Support for the Thesis

Without primary support, the argument is not likely to be convincing. Primary support can be described as the major points writers choose to expand on the thesis. It is the most important information they select to argue their chosen points of view. Each point they choose will be incorporated into the topic sentence for each body paragraph they write. The primary foundational points are further supported by evidentiary details within the paragraphs.

Identify the Characteristics of Good Primary Support

In order to fulfill the requirements of good primary support, the information writers choose must meet the following standards:

Be Specific

The main points they make about the thesis and the examples they use to expand on those points need to be specific. Writers use specific examples to provide the evidence and to build upon the general ideas. These types of examples give the reader something narrow to focus on, and, if used properly, they leave little doubt about their claim. General examples, while they convey the necessary information, are not nearly as compelling or useful in writing because they are too obvious and typical.

Be Relevant to the Thesis

Primary support is considered strong when it relates directly to the thesis. Primary support should show, explain, or prove their main argument without delving into irrelevant details. When faced with a great deal of information that could be used to prove the thesis, writers may think all the information should be included in the body paragraphs. However, effective writers resist the temptation to lose focus. Good writers choose examples wisely by making sure they directly connect to the thesis.

Add Details

The thesis, while specific, should not be very detailed. Discussion develops in the body paragraphs. Using detailed support shows readers that the writer has considered all the facts and chosen only the most precise details to enhance the point of view.

Prewrite to Identify Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

When writers brainstorm on a topic, they essentially make a list of examples or reasons they support the stance. Stemming from each point, the writer should provide details to support those reasons. After prewriting, the writer is then able to look back at the information and choose the most compelling pieces to use in writing body paragraphs.

Select the Most Effective Primary Supporting Points for a Thesis Statement

After writers have engaged in prewriting to formulate working thesis statements, they may have generated a large amount of information, which may be edited later. It is helpful to remember that primary support must be relevant to the thesis. Focusing on the main argument, any ideas that do not directly relate to it can be deleted. Omitting unrelated ideas ensures that writers will use only the most convincing information in their body paragraphs. For many first-year writing assignments, students would do well to choose at least three of the most compelling points. These will serve as the content for the topic sentences that will usually begin each of the body paragraphs.

Body Paragraph Structure

One wat to think about a body paragraph is that it, essentially, consists of three main parts: the main point or topic sentence, information and evidence that supports the main point, and an example of how the information gives foundation to the main point and the essay’s overall thesis. The three parts of a paragraph can be referred to as the following:

I = Information

E = Explanation

An Example of Abbreviated Version of P.I.E.

As a pedestrian in Hawai‘i, it is important to be aware of one’s surroundings. In 2018, 43 pedestrians died in car accidents (Gordon 3). Hawai‘i’s roadways can be dangerous, and being vigilant is necessary in order to increase pedestrian safety.

Point: As a pedestrian in Hawai‘i, it is important to be aware of your surroundings.

Information: In 2018, 43 pedestrians died in car accident.

Explanation: Hawai‘i’s roadways can be dangerous, and being vigilant is necessary to increase pedestrian safety.

Use Transitions

Transitional words and phrases help to organize an essay and improve clarity for the reader. Some examples of transitions can be found at “ Transitional Devices ,” The Purdue Purdue Online Writing Lab (OWL).

- Write a paragraph that contains a main point, follow-up and substantial information, and an explanation about how that information relates to the main point of the paragraph or to the overall thesis of the essay. The topic of your paragraph is up to you. What topic would you like to write about?

P: What is the main point of your paragraph?

I: What information backs up your point?

E: Explain how this information proves that your main point is correct.

Combine these three parts to form a paragraph.

Further Resources

Ashford University Writing Center: “ Essay Development: Good paragraph development: as easy as P.I.E. ” Writing resources .

Works Cited

“ 43 pedestrians died on Hawaii roadways in 2018. That’s more than the number killed in vehicles. ” HawaiiNewsNow , 3 January 2019.

Parts of this section are adapted from OER material from “ Writing Body Paragraphs “ in Writing for Success v. 1.0 (2012). Writing for Success was adapted by Saylor Academy under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License without attribution as requested by the work’s original creator or licensor.

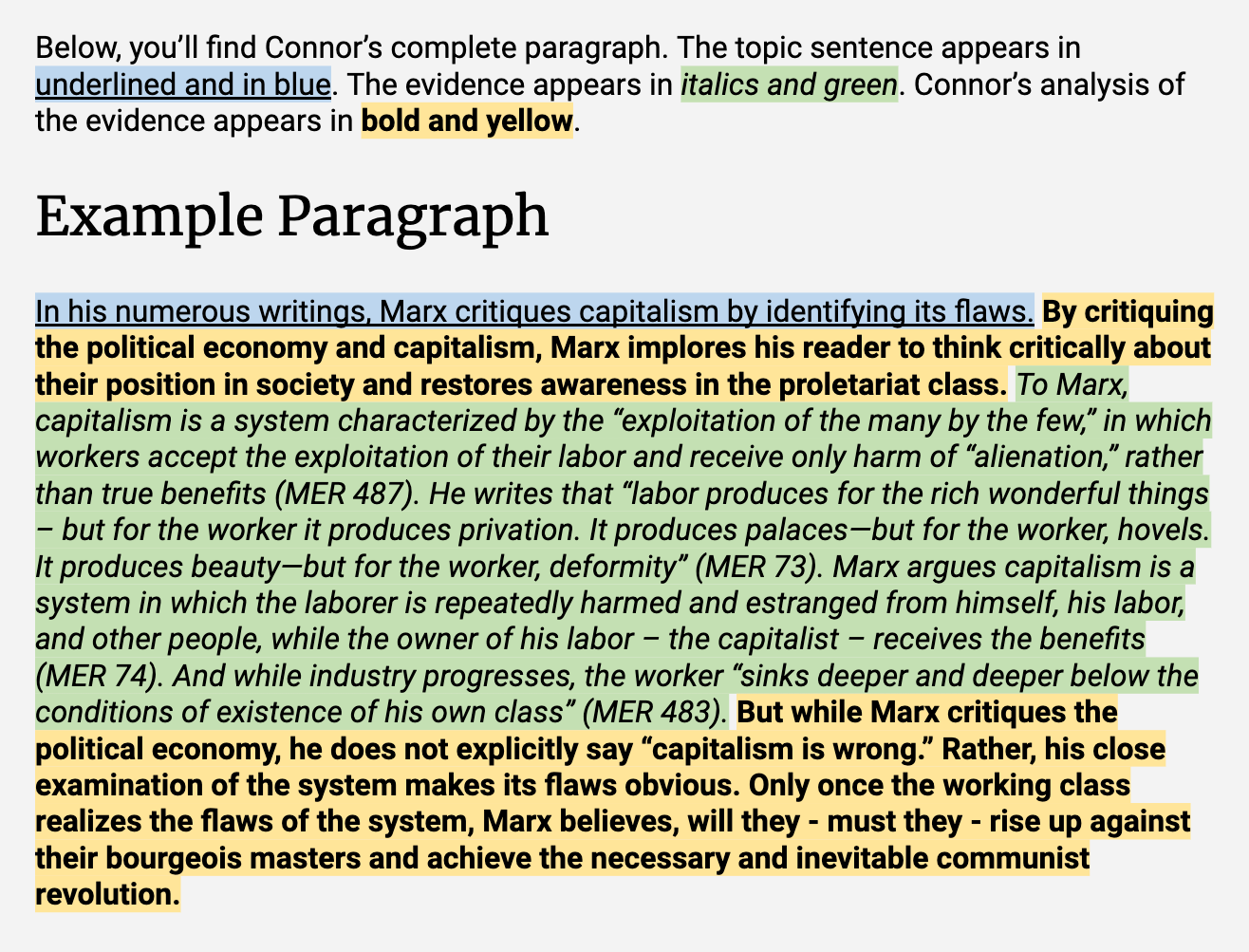

TOPIC SENTENCE/ In his numerous writings, Marx critiques capitalism by identifying its flaws. ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ By critiquing the political economy and capitalism, Marx implores his reader to think critically about their position in society and restores awareness in the proletariat class. EVIDENCE/ To Marx, capitalism is a system characterized by the “exploitation of the many by the few,” in which workers accept the exploitation of their labor and receive only harm of “alienation,” rather than true benefits ( MER 487). He writes that “labour produces for the rich wonderful things – but for the worker it produces privation. It produces palaces—but for the worker, hovels. It produces beauty—but for the worker, deformity” (MER 73). Marx argues capitalism is a system in which the laborer is repeatedly harmed and estranged from himself, his labor, and other people, while the owner of his labor – the capitalist – receives the benefits ( MER 74). And while industry progresses, the worker “sinks deeper and deeper below the conditions of existence of his own class” ( MER 483). ANALYSIS OF EVIDENCE/ But while Marx critiques the political economy, he does not explicitly say “capitalism is wrong.” Rather, his close examination of the system makes its flaws obvious. Only once the working class realizes the flaws of the system, Marx believes, will they - must they - rise up against their bourgeois masters and achieve the necessary and inevitable communist revolution.

Not every paragraph will be structured exactly like this one, of course. But as you draft your own paragraphs, look for all three of these elements: topic sentence, evidence, and analysis.

- picture_as_pdf Anatomy Of a Body Paragraph

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.3: Body Paragraphs

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 6613

In a persuasive essay the body paragraphs are where the writer has the opportunity to argue his or her viewpoint. By the conclusion paragraph, the writer should convince the reader to agree with the argument of the essay. Regardless of a strong thesis, papers with weak body paragraphs fail to explain why the argument of the essay is both true and important. Body paragraphs of a persuasive essay are weak when no quotes or facts are used to support the thesis or when those used are not adequately explained. Occasionally, body paragraphs are also weak because the quotes used detract from rather than support the essay. Thus, it is essential to use appropriate support and to adequately explain your support within your body paragraphs.

In order to create a body paragraph that is properly supported and explained, it is important to understand the components that make up a strong body paragraph. The bullet points below indicate the essential components of a well-written, well-argued body paragraph.

Body Paragraph:

- Begin with a topic sentence that reflects the argument of the thesis statement.

- Support the argument with useful and informative quotes from sources such as books, journal articles, expert opinions, etc.

- Provide 1-2 sentences explaining each quote.

- Provide 1-3 sentences that indicate the significance of each quote.

- Ensure that the information provided is relevant to the thesis statement.

- End with a transition sentence which leads into the next body paragraph.

Just as your introduction must introduce the topic of your essay, the first sentence of a body paragraph must introduce the argument for that paragraph. For instance, if you were writing a body paragraph for a paper arguing that Avatar is innovative in its use of special effects, one body paragraph may begin with a topic sentence that states, “ Avatar has produced the most life-like animated characters of any movie ever created.” Following this sentence, you would go on to indicate how the movie does this by supporting this one statement. When you place this statement as the opening of your paragraph, not only does your audience know what the paragraph is going to argue, but you can also keep track of your ideas.

Following the topic sentence, you must provide some sort of fact that supports your claim. In the example of the Avatar essay, maybe you would provide a quote from a movie critic or from a prominent special effects person. After your quote or fact, you must always explain what the quote or fact is saying, stressing what you believe is most important about your fact. It is important to remember that your audience may read a quote and decide it is arguing something entirely different than what you think it is arguing. Or, maybe some or your readers think another aspect of your quote is important. If you do not explain the quote and indicate what portion of it is relevant to your argument, then your reader may become confused or may be unconvinced of your point. Consider the possible interpretations for the statement below.

Example: While I did not like the acting in the movie, I enjoyed how life-like the special effects made the animated characters in the film. Without the special effects, the acting would have been boring and the plot would have been unoriginal.

Interestingly, this statement seems to be saying two things at once - that the movie is bad and that the movie is good. On the one hand, the person seems to say that the acting and plot of the movie were both bad. However, on the other hand, the person also says that the special effects more than make up for the bad acting and unoriginal plot. Because of this tension in the quotation, if you used this quote in your Avatar paper, you would need to explain that the special effects in the movie are so good that they make boring movie exciting.

In addition to explaining what this quote is saying, you would also need to indicate why this is important to your argument. When trying to indicate the significance of a fact, it is essential to try to answer the “so what.” Image you have just finished explaining your quote to someone, and he or she has asked you “so what?” The person does not understand why you have explained this quote, not because you have not explained the quote well but because you have not told him or her why he or she needs to know what the quote means. This, the answer to the “so what,” is the significance of your paper and is essentially your argument within the body paragraphs. However, it is important to remember that generally a body paragraph will contain more than one quotation or piece of support. Thus, you must repeat the Quotation-Explanation-Significance formula several times within your body paragraph to argue the one sub-point indicated in your topic sentence. Below is an example of a properly written body paragraph.

Follow Polygon online:

- Follow Polygon on Facebook

- Follow Polygon on Youtube

- Follow Polygon on Instagram

Site search

- What to Watch

- What to Play

- PlayStation

- All Entertainment

- Dragon’s Dogma 2

- FF7 Rebirth

- Zelda: Tears of the Kingdom

- Baldur’s Gate 3

- Buyer’s Guides

- Galaxy Brains

- All Podcasts

Filed under:

- Entertainment

What you need to know about The Three-Body Problem before watching 3 Body Problem

Look. I know.

Share this story

- Share this on Facebook

- Share this on Reddit

- Share All sharing options

Share All sharing options for: What you need to know about The Three-Body Problem before watching 3 Body Problem

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/73209679/3_body_problem.0.jpg)

With Netflix’s 3 Body Problem imminent, you might naturally be intrigued by The Three-Body Problem , the science fiction novel by Cixin Liu.

First of all: I cannot explain why the show is 3 Body Problem and the book is The Three-Body Problem . Frankly, this decision drives me bananas. But it does make distinguishing the two in articles like this one easier, and as you’ll soon see, things are going to get complicated enough as is.

What is The Three-Body Problem about?

The simple version is that it’s a story about humanity’s first contact with an alien species. What makes it special is that it’s a very odd first contact story, centering on a wildly immersive VR video game and how it may be connected to the mysterious deaths of the world’s leading scientists. First contact is the light at the end of the story’s tunnel: read the back of the book and you know it’s coming, but how it happens is something you discover by reading.

Why is it such a big deal?

First serialized in China in 2006, The Three-Body Problem quickly racked up accolades upon its 2014 English debut, becoming the first Asian novel to win the Hugo Award for Best Novel. But unusually for such a hard sci-fi novel, The Three-Body Problem quickly escaped the orbit of speculative fiction circles and received glowing write-ups in mainstream press outlets like The New York Times , NPR , and, famously, a shoutout from President Barack Obama . Bob’s Burgers even did a Three-Body Problem episode . It was a big thing!

It’s also a work that some would call unadaptable: The Three-Body Problem has some weird shit going on in its VR game and eventually sets up a conflict that may or may not span centuries.

Remind me what you mean by ‘hard’ sci-fi.

The Three-Body Problem is a brainy book that is very committed to elaborating on the work of a lot of smart characters solving very opaque mysteries. This does not mean it’s impenetrable to people uninterested in becoming conversant in astrophysics, but it does mean there’s quite a bit of what I call “process porn,” focused primarily (but not exclusively) on existing and/or plausible technology. For the most satisfying version of that, consider films like Arrival or even Spotlight (a great movie for making spreadsheets thrilling). How well The Three-Body Problem ’s take on it works for you will depend on how much you connect with translator (and very good novelist in his own right ) Ken Liu’s interpretation of Cixin Liu’s prose.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25336428/3_Body_Problem_n_S1_E1_00_29_51_06RC.jpg_3_Body_Problem_n_S1_E1_00_29_51_06RC.jpg)

It helps that the book begins vividly in the past, during China’s Cultural Revolution in the 1960s — telling a small, personal tragedy that reverberates throughout the first novel as it reaches into the present day and beyond. With that human core in place, it’s easier to get lost in The Three-Body Problem ’s trippy mysteries, and grasp their shocking consequences.

I’m looking up characters from the book and can’t find many in the show. What’s up with that?

Part of what the Netflix adaptation does is relocate a big chunk of the action from China to London, which means lots of changes that ripple outward. Characters are race- and genderbent or reworked and given different names, which makes finding one-to-one analogues for some characters very difficult. But there are very practical concerns that also needed to be addressed, according to the showrunners, and these changes account for that.

“The characters in the book are all spread out in a way, but they don’t know each other, and they don’t connect with each other. Which works really well in a novel, [where] you get inside someone’s head,” co-creator D.B. Weiss told Polygon at a recent press event. “And in television — it’s hard to think of a television show about people who don’t know each other and never meet. Television is about people who know each other, who have strong feelings about each other, interacting with other people about whom they have strong feelings. So we kind of needed to make that happen.”

How much of The Three-Body Problem will 3 Body Problem season 1 adapt?

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/25331011/3_Body_Problem_n_S1_E3_00_14_55_07RC.jpg_3_Body_Problem_n_S1_E3_00_14_55_07RC.jpg)

Pardon? But what if there’s another season?

Oh, there are more books. The Three-Body Problem is the first in a trilogy, known as Remembrance of Earth’s Past. Netflix’s 3 Body Problem is actually an adaptation of the entire trilogy, folding in the novel’s two sequels — The Dark Forest and Death’s End — into its narrative. The first season of the show will cover The Three-Body Problem but will also introduce threads from later books. It’s a comprehensive adaptation, not a piecemeal one.

So you mean it’s done? There’s an end?

Yes, I do mean that. Don’t worry; while David Benioff and D.B. Weiss are most notorious for what happened when the former Game of Thrones showrunners ran out of track laid by their source material, that problem is not present here. They’re also not the only ones in charge, thanks to co-creator Alexander Woo, who has previously worked on excellent series like Manhattan and Wonderfalls . 3 Body Problem will live or die by the adaptation choices made, not for lack of material.

3 Body Problem will premiere on Netflix on March 22.

The next level of puzzles.

Take a break from your day by playing a puzzle or two! We’ve got SpellTower, Typeshift, crosswords, and more.

Sign up for the newsletter Patch Notes

A weekly roundup of the best things from Polygon

Just one more thing!

Please check your email to find a confirmation email, and follow the steps to confirm your humanity.

Oops. Something went wrong. Please enter a valid email and try again.

Loading comments...

Imaginary, Lisa Frankenstein, Netflix’s The Beautiful Game, and every new movie to watch at home this weekend

- Dragon’s Dogma 2 guides, walkthroughs, and explainers

Should you give the grimoires to Myrddin or Trysha in Dragon’s Dogma 2?

All maister skills in Dragon’s Dogma 2 and how to get them

How to get a house in FFXIV

The best recipes in Dragon’s Dogma 2

Suicide Squad: Kill the Justice League’s new Joker is here, and players aren’t laughing

What is '3 Body Problem'? Explaining Netflix's trippy new sci-fi and the three-body problem

The series is the first big post-"game of thrones" project from d.b. weiss and david benioff, but don't expect swords and dragons this time around. here are answers to some burning questions..

In Netflix's new series " 3 Body Problem ," science is broken.

Or so the group of physicists think when things in the world start to go ... haywire. Turns out, in this trippy, visually-stunning mindbender from the creators of " Game of Thrones ," things may not be as they seem.

The series, which serves as " the next big thing " from "Thrones" veterans D.B. Weiss and David Benioff, kicked off a bit of a commotion when it debuted Thursday on the streaming platform. You may have noticed that Netflix was a little extra with its promotion of the series on its homepage when you opened the service on Thursday.

If you weren't prepared for it, the hype may have caused some confusion. Or maybe you watched that series premiere and it's just the show itself that has you confused.

Regardless, we're hoping to answer some of your burning questions about the eight-part sci-fi epic streaming now.

Review: '3 Body Problem' is way more than 'Game of Thrones' with aliens

'House of the Dragon' Season 2: HBO releases 'dueling' trailers; premiere date announced

What is the '3 Body Problem' on Netflix?

Based on science fiction series "Remembrances of Earth's Past" by Chinese author Liu Cixin, "3 Body Problem" tells the story of a humanity confronting a terrifying cosmic threat kicked off by a fateful experiment in 1960s China.

Four years in the making, the series is the first big post-"Thrones" project from Weiss and Benioff, who inked a massive deal with Netflix and teamed up with "True Blood" and "The Terror" writer Alexander Woo to executive produce it. The series is named for the first novel in the trilogy by Cixin, who served as a consultant along with Ken Liu, who wrote the English translation of the books.

"We had in mind that we wanted to do a science fiction show, but we weren't sure which one," Benioff said in a roundtable discussion with Weiss and Woo in an inside look at episode 1 on Netflix. Cixin "created these books that are terrifying for anyone foolish enough to try to adapt them and also just made us very hungry to the possibilities."

In a review , USA TODAY critic Kelly Lawler wrote the first season "stands on its own as a huge achievement" and gave it three out of four stars.

The story begins in 1966 during Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution in China, where Ye Wenjie (Zine Tseng) witnesses the execution of her scientist father before she is forced into labor and imprisonment. As the series debut progresses, Wenjie escapes imprisonment when the Revolution sees a use for her scientific know-how in a little search they're conducting for extraterrestrial life at a mysterious station.

Flash forward to present day, and the group of brilliant scientists and former classmates known as the Oxford 5 are confronted with the consequences of that experiment – primarily, the murder and apparent suicides of scientists around the world. The group isn't part of that original series, but are introduced by showrunners as a means to keep the story grounded amid otherwise weighty philosophical concepts.

"Rather than dryly presenting the nuts and bolts of the physics, we show what it's doing to the people who were confronted by it," Woo said in the Netflix roundtable.

What is the three-body problem in physics?

As for the name of the show itself, it comes from the term for when three celestial objects (planets, stars, or suns that are in close proximity to each other) exert force onto each other, making the objects’ rotation chaotic and unpredictable, according to Netflix .

“As soon as you have three bodies or more that are all exerting a force on each other at the same time, then that system breaks down,” University of Cambridge associate physics professor Matt Kenzie told Netflix. “If you have three bodies or more, then the orbit becomes chaotic.”

It's a problem with no known general solution .

In the series, Netflix notes, the three-body problem comes into play via the three-sun solar system that San-Ti's planet inhabits, which contributes to stable and chaotic eras.

"When the planet revolves around one sun, it’s a stable era. When another sun snatches the planet away, it wanders in the gravitational field between the three suns, causing a chaotic era. In a chaotic era, the living conditions can become too extreme for life to exist," Netflix writes.

Other concepts in '3 Body Problem'

The show introduces plenty of seemingly outlandish concepts in just its first episode that span the metaphysical and even extraterrestrial.

Early on, it's made clear that amid the mysterious deaths of scientists, experiments in particle accelerators have been producing what should be impossible results. Hence, why viewers are reminded several times by investigator Da Shi (Benedict Wong): "Science is broken."

But it's not that simple, as the Oxford 5 start to learn. When one of them, Auggie Salazar (Eiza González) starts seeing a menacing countdown in her vision, it doesn't take long until she's confronted with a startlingly reality: The numbers aren't a neurological disorder or hallucination, but are very, very real.

And she better hope, for her sake, that they don't reach zero.

"3 Body Problem" also introduced in its first episode a metallic headset resembling a futuristic VR set that will become integral as the series progresses. When physicist Jin Cheng (Jess Wong) dons the contraption, the last thing she sees are her own eyes looking back at her before the scene opens onto a virtual environment that looks straight out of a VR game.

But as everything with this show, there's something vaguely threatening about what is unfolding within that virtual world.

As Woo said, all of this is "emblematic of the inexplicable problems that are confronting the scientists."

"They are not people to believe in the supernatural so whatever is happening ... is scary," Woo said in the roundtable.

When the first episode comes to a close, some of the characters stare up at the sky as stars begin to blink in what may be Morse Code. The development "ups the ante" and makes it clear particularly to Auggie that her countdown isn't just in her mind.

"But its arguably a lot worse if there's something else that's being witnessed by everyone else on the globe," Weiss said.

Interviews: With Netflix series '3 Body Problem,' 'Game Of Thrones' creators try their hand at sci-fi

Cast of '3 Body Problem'

"Game of Thrones" fans will recognize a couple of familiar faces in "3 Body Problem": Liam Cunningham, who portrayed everyone's favorite former smuggler and loyal "onion knight" Davos Seaworth; and John Bradley, best known as the tenderhearted and seemingly meek Samwell Tarly.

Benioff and Weiss even brought over "Thrones" composer Ramin Djawadi for the series' score.

Here's the rest of the cast:

- Jess Hong as Jin Cheng

- John Bradley as Jack Rooney

- Zine Tseng as young Ye Wenjie

- Rosalind Chao as older Ye Wenjie

- Eiza González as Auggie Salazar

- Jovan Adepo as Saul Durand

- Alex Sharp as Will Downing

- Benedict Wong as Da Shi

- Liam Cunningham as Thomas Wade

- Marlo Kelly as Tatiana

Eric Lagatta covers breaking and trending news for USA TODAY. Reach him at [email protected]

Advertisement

Supported by

‘Game of Thrones’ Creators Look Skyward for Their New Series

In an interview, David Benioff, D.B. Weiss and Alexander Woo discuss their latest fantastical epic, the alien space saga “3 Body Problem” for Netflix.

- Share full article

By Chris Vognar

Reporting from Austin

The “Game of Thrones” creators David Benioff and D.B. Weiss were finishing off their hit HBO series after an eight-season run and wondering what was next. That was when the Netflix executive Peter Friedlander approached them with a trilogy of science-fiction books by the Chinese novelist Liu Cixin called “Remembrance of Earth’s Past.”

“We knew that it won the Hugo Award, which is a big deal for us since we grew up as nerds,” Benioff said of the literary prize for science fiction. Barack Obama was also on record as a fan.

Benioff and Weiss dipped in and were intrigued by what they found: a sweeping space invasion saga that begins in 1960s China, amid the turmoil of the Cultural Revolution, and involves a superior alien race that has built a rabid cultlike following on Earth. A heady mix of science and skulduggery, featuring investigations both scientific and criminal, it felt utterly unique. “So much content right now feels like, ‘Oh, here’s another forensic show, here’s another legal thriller,’ it just feels like it’s a version of something you’ve seen,” Benioff said. “This universe is a different one.”

Or, as Weiss added, “This is the universe.”

Those novels are now the core of “3 Body Problem,” a new series that Benioff and Weiss created with Alexander Woo (“True Blood”). It premiered on opening night at the South by Southwest Film Festival and arrives Thursday on Netflix. The setting has changed along the way, with most of the action unfolding in London rather than China (although the Cultural Revolution is still a key element), and the characters, most of them young and pretty, now represent several countries. But the central themes remain the same: belief, fear, discovery and an Earth imperiled by superior beings. Among the heroes are the gruff intelligence chief Thomas Wade, played by the “Thrones” veteran Liam Cunningham, and a team of five young, reluctant, Oxford-trained physicists played by John Bradley — another “Thrones” star — Jovan Adepo, Eiza González, Jess Hong and Alex Sharp. Can they save the world for their descendants?

In an interview in Austin the day of the SXSW premiere, the series creators discussed life after “Thrones,” their personal ties to “3 Body Problem” and the trick to making physics sexy. These are edited excerpts from the conversation.

The series is quite different from the books, particularly the settings and characters, both of which are a lot less Chinese. How did this come about?

D.B. WEISS Once the long process of acquiring the rights to the books was finished, we ended up with the rights for an English-language adaptation. So if we had kept all the characters Chinese in China, then we would’ve had a whole show set in China in English. We also thought it was really important to the nature of the story that the group of people working together to solve this problem look like the world. Obviously, there’s going to be an American involved. There’s a Chinese person who was born in China, but also the Chinese diaspora. There are people from Southwest Asia. There are people from Latin South America. It just made fundamental sense to us to broaden the scope of it, because if this happened to the world, it feels like that’s what would happen in the process of dealing with it.

“Game of Thrones” was a cultural behemoth. How did that experience inform how you approached this show?

WEISS I thought we were making a show for a lot of Dungeons and Dragons players. Of which I am one.

DAVID BENIOFF And it wasn’t a behemoth out of the gate. In case anyone from Netflix is listening: It took years for that show to become big, and they had faith in it and stuck with it. But one of the things I think we learned on “Thrones” was to hire really good people who know what they’re doing, and then make sure they understand what you’re looking for.

We’ve been talking a lot about Ramin Djawadi, our composer from “Thrones,” who’s also the composer on this show and hopefully the composer on everything we ever do. Nine times out of 10, when he delivers a cue to us, we’re like, “That’s great, Ramin.” And then the 10th time — sometimes we don’t even know exactly what’s wrong with it, it’s like, “I don’t know.” And he’ll think about it for a second and say, “Let me just take another shot at it. I get it.” And that’s rare, I think, to find someone who’s such a high-level artist who’s also that open and doesn’t get easily offended. We have a number of people like that we worked with on “Thrones” that we brought with us to this show.

How about having such a fervent fan base that wasn’t shy about what they wanted, especially down the stretch of the series?

BENIOFF It was interesting. We live in interesting times.

WEISS You want people to watch what you make, but you don’t get to control people’s reactions to what you make.

BENIOFF Not yet.

WEISS We’re working on a device. I’m sure somebody’s working on it, anyway. But until they make the device, you make the story that you want to make, if you’re lucky enough to have the backing necessary to do that, then let what happens happen.

You don’t see a lot of series that look at Mao’s Cultural Revolution. The opening struggle session sequence is terrifying.

ALEXANDER WOO It’s a part of history that is not written about in fiction very much, let alone filmed. And my family lived through it, as did the family of Derek Tsang, who directed the first two episodes. We give a lot of credit to him for bringing that to life, because he knew that it had not been filmed with this clinical eye maybe ever. He took enormous pains to have every detail of it depicted as real as it could be. I showed it to my mother, and you could see a chill coming over her, and she said, “That’s real. This is what really happened.” And she added, “Why would you show something like that? Why do you make people experience something so terrible?” But that’s how we knew we’d done our job.

“Thrones” rolled out week by week and consequently received intense, sustained attention throughout most of its seasons. What has it been like working in the binge model, with the entire first season of “3 Body Problem” dropping all at once?