- Free Study Planner

- Residency Consulting

- Free Resources

- Med School Blog

- 1-888-427-7737

The Ultimate Patient Case Presentation Template for Med Students

- by Neelesh Bagrodia

- Apr 06, 2024

- Reviewed by: Amy Rontal, MD

Knowing how to deliver a patient presentation is one of the most important skills to learn on your journey to becoming a physician. After all, when you’re on a medical team, you’ll need to convey all the critical information about a patient in an organized manner without any gaps in knowledge transfer.

One big caveat: opinions about the correct way to present a patient are highly personal and everyone is slightly different. Additionally, there’s a lot of variation in presentations across specialties, and even for ICU vs floor patients.

My goal with this blog is to give you the most complete version of a patient presentation, so you can tailor your presentations to the preferences of your attending and team. So, think of what follows as a model for presenting any general patient.

Here’s a breakdown of what goes into the typical patient presentation.

7 Ingredients for a Patient Case Presentation Template

1. the one-liner.

The one-liner is a succinct sentence that primes your listeners to the patient.

A typical format is: “[Patient name] is a [age] year-old [gender] with past medical history of [X] presenting with [Y].

2. The Chief Complaint

This is a very brief statement of the patient’s complaint in their own words. A common pitfall is when medical students say that the patient had a chief complaint of some medical condition (like cholecystitis) and the attending asks if the patient really used that word!

An example might be, “Patient has chief complaint of difficulty breathing while walking.”

3. History of Present Illness (HPI)

The goal of the HPI is to illustrate the story of the patient’s complaint.

I remember when I first began medical school, I had a lot of trouble determining what was relevant and ended up giving a lot of extra details. Don’t worry if you have the same issue. With time, you’ll learn which details are important.

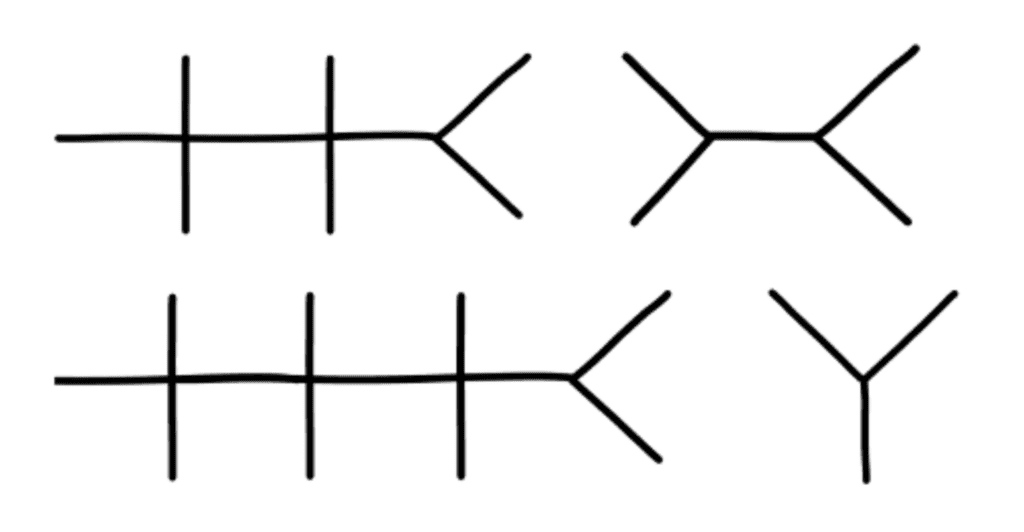

The OPQRST Framework

In the beginning of your clinical experience, a helpful framework to use is OPQRST:

Describe when the issue started, and if it occurs during certain environmental or personal exposures.

P rovocative

Report if there are any factors that make the pain better or worse. These can be broad, like noting their shortness of breath worsened when lying flat, or their symptoms resolved during rest.

Relay how the patient describes their pain or associated symptoms. For example, does the patient have a burning versus a pressure sensation? Are they feeling weakness, stiffness, or pain?

R egion/Location

Indicate where the pain is located and if it radiates anywhere.

Talk about how bad the pain is for the patient. Typically, a 0-10 pain scale is useful to provide some objective measure.

Discuss how long the pain lasts and how often it occurs.

A Case Study

While the OPQRST framework is great when starting out, it can be limiting.

Let’s take an example where the patient is not experiencing pain and comes in with altered mental status along with diffuse jaundice of the skin and a history of chronic liver disease. You will find that certain sections of OPQRST do not apply.

In this event, the HPI is still a story, but with a different framework. Try to go in chronological order. Include relevant details like if there have been any changes in medications, diet, or bowel movements.

Pertinent Positive and Negative Symptoms

Regardless of the framework you use, the name of the game is pertinent positive and negative symptoms the patient is experiencing.

I’d like to highlight the word “pertinent.” It’s less likely the patient’s chronic osteoarthritis and its management is related to their new onset shortness of breath, but it’s still important for knowing the patient’s complete medical picture. A better place to mention these details would be in the “Past Medical History” section, and reserve the HPI portion for more pertinent history.

As you become exposed to more illness scripts, experience will teach you which parts of the history are most helpful to state. Also, as you spend more time on the wards, you will pick up on which questions are relevant and important to ask during the patient interview.

By painting a clear picture with pertinent positives and negatives during your presentation, the history will guide what may be higher or lower on the differential diagnosis.

Some other important components to add are the patient’s additional past medical/surgical history, family history, social history, medications, allergies, and immunizations.

The HEADSSS Method

Particularly, the social history is an important time to describe the patient as a complete person and understand how their life story may affect their present condition.

One way of organizing the social history is the HEADSSS method:

– H ome living situation and relationships – E ducation and employment – A ctivities and hobbies – D rug use (alcohol, tobacco, cocaine, etc.) Note frequency of use, and if applicable, be sure to add which types of alcohol consumption (like beer versus hard liquor) and forms of drug use. – S exual history (partners, STI history, pregnancy plans) – S uicidality and depression – S piritual and religious history

Again, there’s a lot of variation in presenting social history, so just follow the lead of your team. For example, it’s not always necessary/relevant to obtain a sexual history, so use your judgment of the situation.

4. Review of Symptoms

Oftentimes, most elements of this section are embedded within the HPI. If there are any additional symptoms not mentioned in the HPI, it’s appropriate to state them here.

5. Objective

Vital signs.

Some attendings love to hear all five vital signs: temperature, blood pressure (mean arterial pressure if applicable), heart rate, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation. Others are happy with “afebrile and vital signs stable.” Just find out their preference and stick to that.

Physical Exam

This is one of the most important parts of the patient presentation for any specialty. It paints a picture of how the patient looks and can guide acute management like in the case of a rigid abdomen. As discussed in the HPI section, typically you should report pertinent positives and negatives. When you’re starting out, your attending and team may prefer for you to report all findings as part of your learning.

For example, pulmonary exam findings can be reported as: “Regular chest appearance. No abnormalities on palpation. Lungs resonant to percussion. Clear to auscultation bilaterally without crackles, rhonchi, or wheezing.”

Typically, you want to report the physical exams in a head to toe format: General Appearance, Mental Status, Neurologic, Eyes/Ears/Nose/Mouth/Neck, Cardiovascular, Pulmonary, Breast, Abdominal, Genitourinary, Musculoskeletal, and Skin. Depending on the situation, additional exams can be incorporated as applicable.

Now comes reporting pertinent positive and negative labs. Several labs are often drawn upon admission. It’s easy to fall into the trap of reading off all the labs and losing everyone’s attention. Here are some pieces of advice:

You normally can’t go wrong sticking to abnormal lab values.

One qualification is that for a patient with concern for acute coronary syndrome, reporting a normal troponin is essential. Also, stating the normalization of previously abnormal lab values like liver enzymes is important.

Demonstrate trends in lab values.

A lab value is just a single point in time and does not paint the full picture. For example, a hemoglobin of 10g/dL in a patient at 15g/dL the previous day is a lot more concerning than a patient who has been stable at 10g/dL for a week.

Try to avoid editorializing in this section.

Save your analysis of the labs for the assessment section. Again, this can be a point of personal preference. In my experience, the team typically wants the raw objective data in this section.

This is also a good place to state the ins and outs of your patient (if applicable). In some patients, these metrics are strictly recorded and are typically reported as total fluid in and out over the past day followed by the net fluid balance. For example, “1L in, 2L out, net -1L over the past 24 hours.”

6. Diagnostics/Imaging

Next, you’ll want to review any important diagnostic tests and imaging. For example, describe how the EKG and echo look in a patient presenting with chest pain or the abdominal CT scan in a patient with right lower quadrant abdominal pain.

Try to provide your own interpretation to develop your skills and then include the final impression. Also, report if a diagnostic test is still pending.

7. Assessment/Plan

This is the fun part where you get to use your critical thinking (aka doctor) skills! For the scope of this blog, we’ll review a problem-based plan.

It’s helpful to begin with a summary statement that incorporates the one-liner, presenting issue(s)/diagnosis(es), and patient stability.

Then, go through all the problems relevant to the admission. You can impress your audience by casting a wide differential diagnosis and going through the elements of your patient presentation that support one diagnosis over another.

Following your assessment, try to suggest a management plan. In a patient with congestive heart failure exacerbation, initiating a diuresis regimen and measuring strict ins/outs are good starting points.

You may even suggest a follow-up on their latest ejection fraction with an echo and check if they’re on guideline-directed medical therapy. Again, with more time on the clinical wards you’ll start to pick up on what management plan to suggest.

One pointer is to talk about all relevant problems, not just the presenting issue. For example, a patient with diabetes may need to be put on a sliding scale insulin regimen or another patient may require physical/occupational therapy. Just try to stay organized and be comprehensive.

A Note About Patient Presentation Skills

When you’re doing your first patient presentations, it’s common to feel nervous. There may be a lot of “uhs” and “ums.”

Here’s the good news: you don’t have to be perfect! You just need to make a good faith attempt and keep on going with the presentation.

With time, your confidence will build. Practice your fluency in the mirror when you have a chance. No one was born knowing medicine and everyone has gone through the same stages of learning you are!

Practice your presentation a couple times before you present to the team if you have time. Pull a resident aside if they have the bandwidth to make sure you have all the information you need.

One big piece of advice: NEVER LIE. If you don’t know a specific detail, it’s okay to say, “I’m not sure, but I can look that up.” Someone on your team can usually retrieve the information while you continue on with your presentation.

Example Patient Case Presentation Template

Here’s a blank patient case presentation template that may come in handy. You can adapt it to best fit your needs.

Chief Complaint:

History of Present Illness:

Past Medical History:

Past Surgical History:

Family History:

Social History:

Medications:

Immunizations:

Vital Signs : Temp ___ BP ___ /___ HR ___ RR ___ O2 sat ___

Physical Exam:

General Appearance:

Mental Status:

Neurological:

Eyes, Ears, Nose, Mouth, and Neck:

Cardiovascular:

Genitourinary:

Musculoskeletal:

Most Recent Labs:

Previous Labs:

Diagnostics/Imaging:

Impression/Interpretation:

Assessment/Plan:

One-line summary:

#Problem 1:

Assessment:

#Problem 2:

Final Thoughts on Patient Presentations

I hope this post demystified the patient presentation for you. Be sure to stay organized in your delivery and be flexible with the specifications your team may provide.

Something I’d like to highlight is that you may need to tailor the presentation to the specialty you’re on. For example, on OB/GYN, it’s important to include a pregnancy history. Nonetheless, the aforementioned template should set you up for success from a broad overview perspective.

Stay tuned for my next post on how to give an ICU patient presentation. And if you’d like me to address any other topics in a blog, write to me at [email protected] !

Looking for more (free!) content to help you through clinical rotations? Check out these other posts from Blueprint tutors on the Med School blog:

- How I Balanced My Clinical Rotations with Shelf Exam Studying

- How (and Why) to Use a Qbank to Prepare for USMLE Step 2

- How to Study For Shelf Exams: A Tutor’s Guide

About the Author

Hailing from Phoenix, AZ, Neelesh is an enthusiastic, cheerful, and patient tutor. He is a fourth year medical student at the Keck School of Medicine of the University of Southern California and serves as president for the Class of 2024. He is applying to surgery programs for residency. He also graduated as valedictorian of his high school and the USC Viterbi School of Engineering, obtaining a B.S. in Biomedical Engineering in 2020. He discovered his penchant for teaching when he began tutoring his friends for the SAT and ACT in the summer of 2015 out of his living room. Outside of the academic sphere, Neelesh enjoys surfing at San Onofre Beach and hiking in the Santa Monica Mountains. Twitter: @NeeleshBagrodia LinkedIn: http://www.linkedin.com/in/neelesh-bagrodia

Related Posts

The Ultimate ICU Patient Presentation Template for Med Students

How Long Does It Take to Become a Surgeon?

Navigating the ERAS Residency Application Timeline: The Ultimate Guide

Search the blog, try blueprint med school study planner.

Create a personalized study schedule in minutes for your upcoming USMLE, COMLEX, or Shelf exam. Try it out for FREE, forever!

Could You Benefit from Tutoring?

Sign up for a free consultation to get matched with an expert tutor who fits your board prep needs

Find Your Path in Medicine

A side by side comparison of specialties created by practicing physicians, for you!

Popular Posts

Need a personalized USMLE/COMLEX study plan?

We use essential cookies to make Venngage work. By clicking “Accept All Cookies”, you agree to the storing of cookies on your device to enhance site navigation, analyze site usage, and assist in our marketing efforts.

Manage Cookies

Cookies and similar technologies collect certain information about how you’re using our website. Some of them are essential, and without them you wouldn’t be able to use Venngage. But others are optional, and you get to choose whether we use them or not.

Strictly Necessary Cookies

These cookies are always on, as they’re essential for making Venngage work, and making it safe. Without these cookies, services you’ve asked for can’t be provided.

Show cookie providers

- Google Login

Functionality Cookies

These cookies help us provide enhanced functionality and personalisation, and remember your settings. They may be set by us or by third party providers.

Performance Cookies

These cookies help us analyze how many people are using Venngage, where they come from and how they're using it. If you opt out of these cookies, we can’t get feedback to make Venngage better for you and all our users.

- Google Analytics

Targeting Cookies

These cookies are set by our advertising partners to track your activity and show you relevant Venngage ads on other sites as you browse the internet.

- Google Tag Manager

- Infographics

- Daily Infographics

- Template Lists

- Graphic Design

- Graphs and Charts

- Data Visualization

- Human Resources

- Beginner Guides

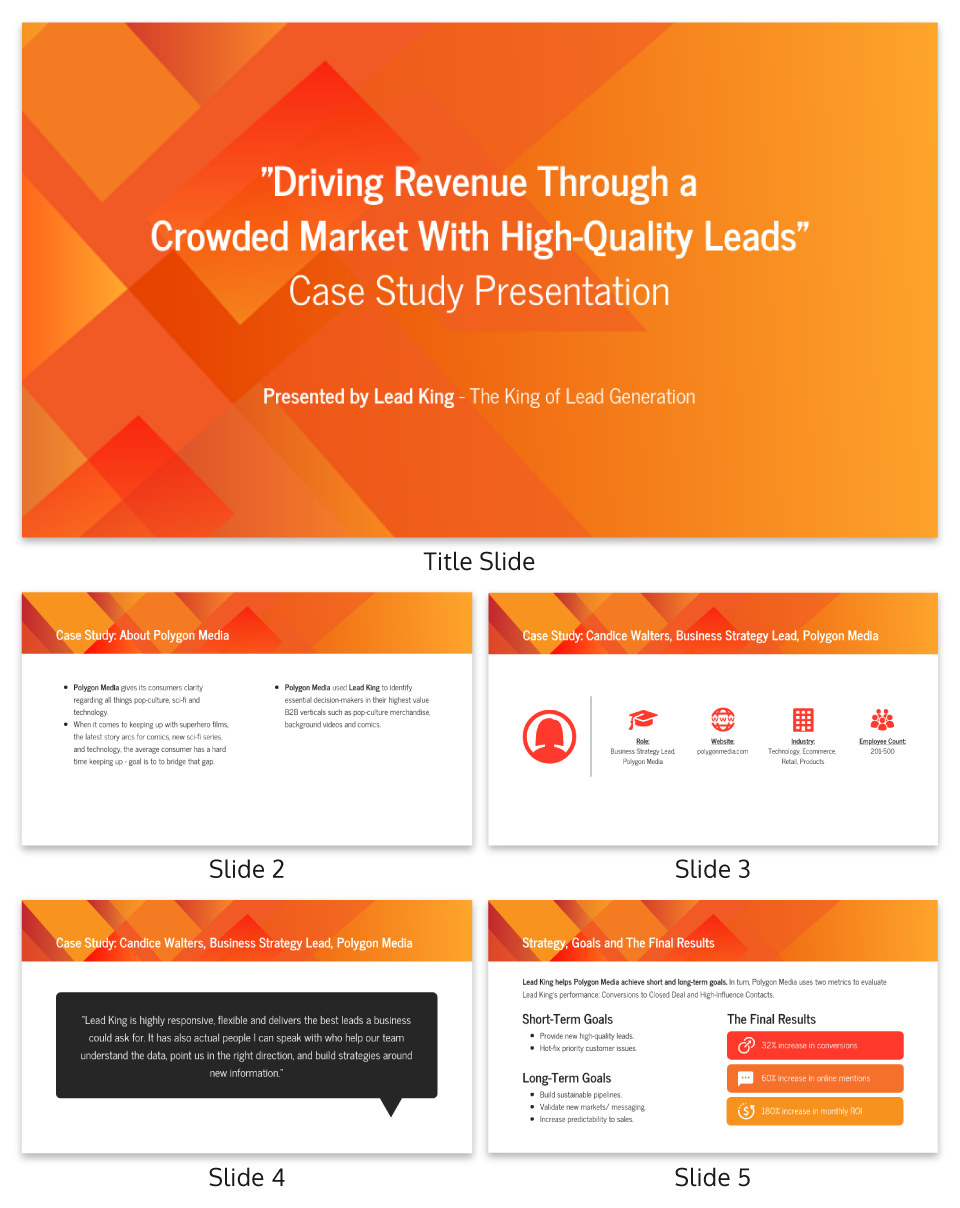

Blog Business How to Present a Case Study like a Pro (With Examples)

How to Present a Case Study like a Pro (With Examples)

Written by: Danesh Ramuthi Sep 07, 2023

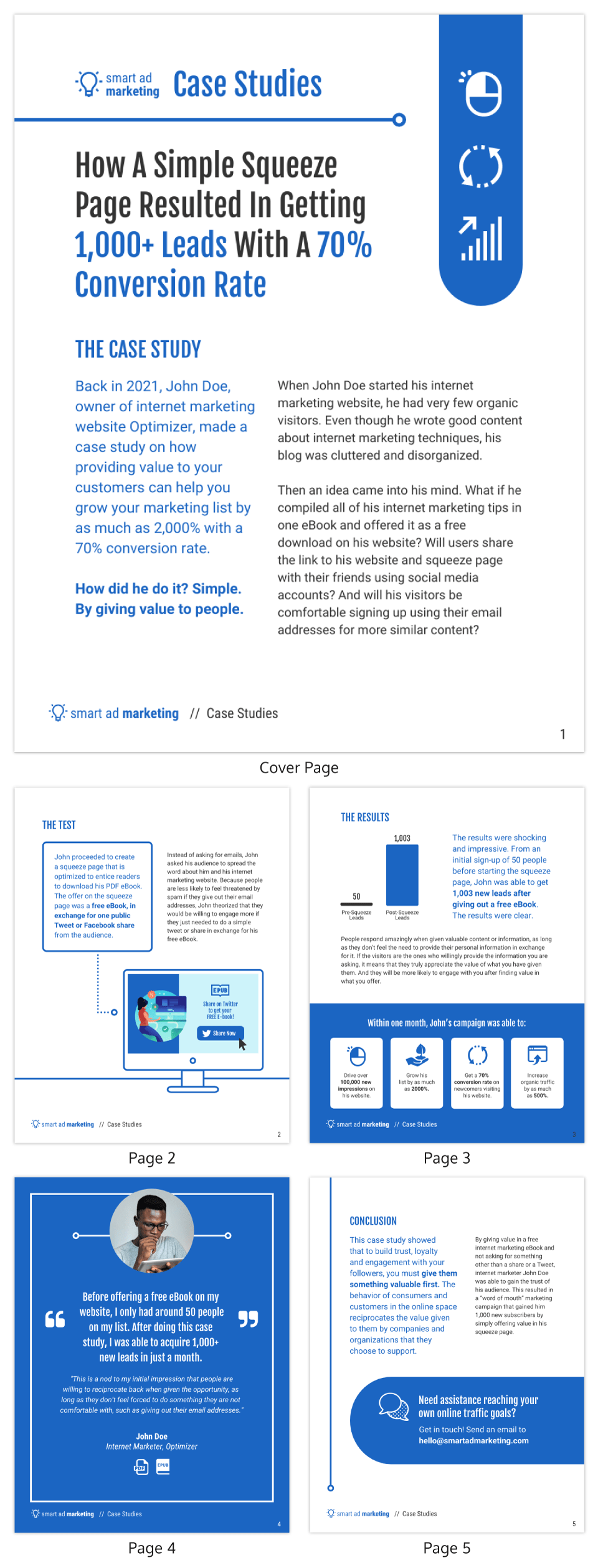

Okay, let’s get real: case studies can be kinda snooze-worthy. But guess what? They don’t have to be!

In this article, I will cover every element that transforms a mere report into a compelling case study, from selecting the right metrics to using persuasive narrative techniques.

And if you’re feeling a little lost, don’t worry! There are cool tools like Venngage’s Case Study Creator to help you whip up something awesome, even if you’re short on time. Plus, the pre-designed case study templates are like instant polish because let’s be honest, everyone loves a shortcut.

Click to jump ahead:

What is a case study presentation?

What is the purpose of presenting a case study, how to structure a case study presentation, how long should a case study presentation be, 5 case study presentation examples with templates, 6 tips for delivering an effective case study presentation, 5 common mistakes to avoid in a case study presentation, how to present a case study faqs.

A case study presentation involves a comprehensive examination of a specific subject, which could range from an individual, group, location, event, organization or phenomenon.

They’re like puzzles you get to solve with the audience, all while making you think outside the box.

Unlike a basic report or whitepaper, the purpose of a case study presentation is to stimulate critical thinking among the viewers.

The primary objective of a case study is to provide an extensive and profound comprehension of the chosen topic. You don’t just throw numbers at your audience. You use examples and real-life cases to make you think and see things from different angles.

The primary purpose of presenting a case study is to offer a comprehensive, evidence-based argument that informs, persuades and engages your audience.

Here’s the juicy part: presenting that case study can be your secret weapon. Whether you’re pitching a groundbreaking idea to a room full of suits or trying to impress your professor with your A-game, a well-crafted case study can be the magic dust that sprinkles brilliance over your words.

Think of it like digging into a puzzle you can’t quite crack . A case study lets you explore every piece, turn it over and see how it fits together. This close-up look helps you understand the whole picture, not just a blurry snapshot.

It’s also your chance to showcase how you analyze things, step by step, until you reach a conclusion. It’s all about being open and honest about how you got there.

Besides, presenting a case study gives you an opportunity to connect data and real-world scenarios in a compelling narrative. It helps to make your argument more relatable and accessible, increasing its impact on your audience.

One of the contexts where case studies can be very helpful is during the job interview. In some job interviews, you as candidates may be asked to present a case study as part of the selection process.

Having a case study presentation prepared allows the candidate to demonstrate their ability to understand complex issues, formulate strategies and communicate their ideas effectively.

The way you present a case study can make all the difference in how it’s received. A well-structured presentation not only holds the attention of your audience but also ensures that your key points are communicated clearly and effectively.

In this section, let’s go through the key steps that’ll help you structure your case study presentation for maximum impact.

Let’s get into it.

Open with an introductory overview

Start by introducing the subject of your case study and its relevance. Explain why this case study is important and who would benefit from the insights gained. This is your opportunity to grab your audience’s attention.

Explain the problem in question

Dive into the problem or challenge that the case study focuses on. Provide enough background information for the audience to understand the issue. If possible, quantify the problem using data or metrics to show the magnitude or severity.

Detail the solutions to solve the problem

After outlining the problem, describe the steps taken to find a solution. This could include the methodology, any experiments or tests performed and the options that were considered. Make sure to elaborate on why the final solution was chosen over the others.

Key stakeholders Involved

Talk about the individuals, groups or organizations that were directly impacted by or involved in the problem and its solution.

Stakeholders may experience a range of outcomes—some may benefit, while others could face setbacks.

For example, in a business transformation case study, employees could face job relocations or changes in work culture, while shareholders might be looking at potential gains or losses.

Discuss the key results & outcomes

Discuss the results of implementing the solution. Use data and metrics to back up your statements. Did the solution meet its objectives? What impact did it have on the stakeholders? Be honest about any setbacks or areas for improvement as well.

Include visuals to support your analysis

Visual aids can be incredibly effective in helping your audience grasp complex issues. Utilize charts, graphs, images or video clips to supplement your points. Make sure to explain each visual and how it contributes to your overall argument.

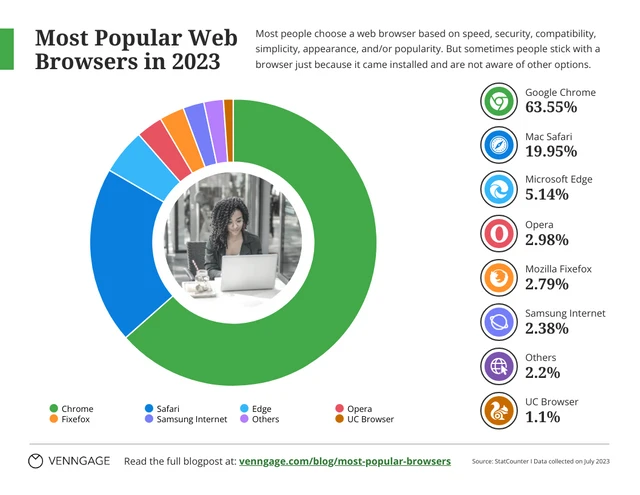

Pie charts illustrate the proportion of different components within a whole, useful for visualizing market share, budget allocation or user demographics.

This is particularly useful especially if you’re displaying survey results in your case study presentation.

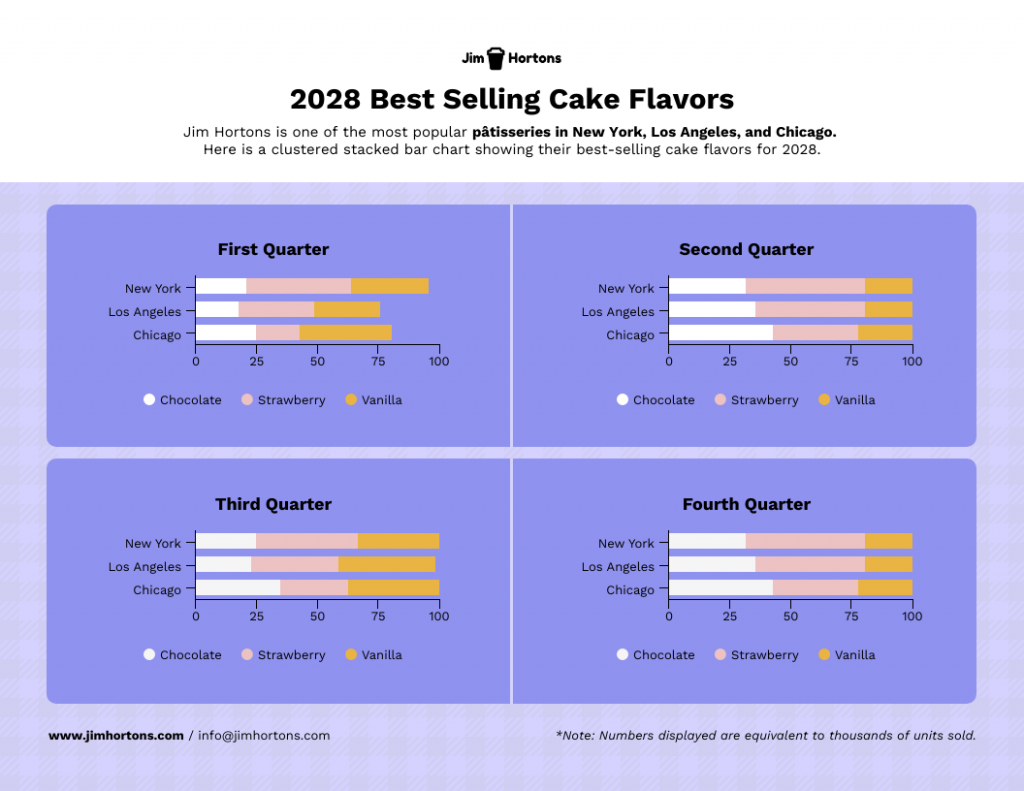

Stacked charts on the other hand are perfect for visualizing composition and trends. This is great for analyzing things like customer demographics, product breakdowns or budget allocation in your case study.

Consider this example of a stacked bar chart template. It provides a straightforward summary of the top-selling cake flavors across various locations, offering a quick and comprehensive view of the data.

Not the chart you’re looking for? Browse Venngage’s gallery of chart templates to find the perfect one that’ll captivate your audience and level up your data storytelling.

Recommendations and next steps

Wrap up by providing recommendations based on the case study findings. Outline the next steps that stakeholders should take to either expand on the success of the project or address any remaining challenges.

Acknowledgments and references

Thank the people who contributed to the case study and helped in the problem-solving process. Cite any external resources, reports or data sets that contributed to your analysis.

Feedback & Q&A session

Open the floor for questions and feedback from your audience. This allows for further discussion and can provide additional insights that may not have been considered previously.

Closing remarks

Conclude the presentation by summarizing the key points and emphasizing the takeaways. Thank your audience for their time and participation and express your willingness to engage in further discussions or collaborations on the subject.

Well, the length of a case study presentation can vary depending on the complexity of the topic and the needs of your audience. However, a typical business or academic presentation often lasts between 15 to 30 minutes.

This time frame usually allows for a thorough explanation of the case while maintaining audience engagement. However, always consider leaving a few minutes at the end for a Q&A session to address any questions or clarify points made during the presentation.

When it comes to presenting a compelling case study, having a well-structured template can be a game-changer.

It helps you organize your thoughts, data and findings in a coherent and visually pleasing manner.

Not all case studies are created equal and different scenarios require distinct approaches for maximum impact.

To save you time and effort, I have curated a list of 5 versatile case study presentation templates, each designed for specific needs and audiences.

Here are some best case study presentation examples that showcase effective strategies for engaging your audience and conveying complex information clearly.

1 . Lab report case study template

Ever feel like your research gets lost in a world of endless numbers and jargon? Lab case studies are your way out!

Think of it as building a bridge between your cool experiment and everyone else. It’s more than just reporting results – it’s explaining the “why” and “how” in a way that grabs attention and makes sense.

This lap report template acts as a blueprint for your report, guiding you through each essential section (introduction, methods, results, etc.) in a logical order.

Want to present your research like a pro? Browse our research presentation template gallery for creative inspiration!

2. Product case study template

It’s time you ditch those boring slideshows and bullet points because I’ve got a better way to win over clients: product case study templates.

Instead of just listing features and benefits, you get to create a clear and concise story that shows potential clients exactly what your product can do for them. It’s like painting a picture they can easily visualize, helping them understand the value your product brings to the table.

Grab the template below, fill in the details, and watch as your product’s impact comes to life!

3. Content marketing case study template

In digital marketing, showcasing your accomplishments is as vital as achieving them.

A well-crafted case study not only acts as a testament to your successes but can also serve as an instructional tool for others.

With this coral content marketing case study template—a perfect blend of vibrant design and structured documentation, you can narrate your marketing triumphs effectively.

4. Case study psychology template

Understanding how people tick is one of psychology’s biggest quests and case studies are like magnifying glasses for the mind. They offer in-depth looks at real-life behaviors, emotions and thought processes, revealing fascinating insights into what makes us human.

Writing a top-notch case study, though, can be a challenge. It requires careful organization, clear presentation and meticulous attention to detail. That’s where a good case study psychology template comes in handy.

Think of it as a helpful guide, taking care of formatting and structure while you focus on the juicy content. No more wrestling with layouts or margins – just pour your research magic into crafting a compelling narrative.

5. Lead generation case study template

Lead generation can be a real head-scratcher. But here’s a little help: a lead generation case study.

Think of it like a friendly handshake and a confident resume all rolled into one. It’s your chance to showcase your expertise, share real-world successes and offer valuable insights. Potential clients get to see your track record, understand your approach and decide if you’re the right fit.

No need to start from scratch, though. This lead generation case study template guides you step-by-step through crafting a clear, compelling narrative that highlights your wins and offers actionable tips for others. Fill in the gaps with your specific data and strategies, and voilà! You’ve got a powerful tool to attract new customers.

Related: 15+ Professional Case Study Examples [Design Tips + Templates]

So, you’ve spent hours crafting the perfect case study and are now tasked with presenting it. Crafting the case study is only half the battle; delivering it effectively is equally important.

Whether you’re facing a room of executives, academics or potential clients, how you present your findings can make a significant difference in how your work is received.

Forget boring reports and snooze-inducing presentations! Let’s make your case study sing. Here are some key pointers to turn information into an engaging and persuasive performance:

- Know your audience : Tailor your presentation to the knowledge level and interests of your audience. Remember to use language and examples that resonate with them.

- Rehearse : Rehearsing your case study presentation is the key to a smooth delivery and for ensuring that you stay within the allotted time. Practice helps you fine-tune your pacing, hone your speaking skills with good word pronunciations and become comfortable with the material, leading to a more confident, conversational and effective presentation.

- Start strong : Open with a compelling introduction that grabs your audience’s attention. You might want to use an interesting statistic, a provocative question or a brief story that sets the stage for your case study.

- Be clear and concise : Avoid jargon and overly complex sentences. Get to the point quickly and stay focused on your objectives.

- Use visual aids : Incorporate slides with graphics, charts or videos to supplement your verbal presentation. Make sure they are easy to read and understand.

- Tell a story : Use storytelling techniques to make the case study more engaging. A well-told narrative can help you make complex data more relatable and easier to digest.

Ditching the dry reports and slide decks? Venngage’s case study templates let you wow customers with your solutions and gain insights to improve your business plan. Pre-built templates, visual magic and customer captivation – all just a click away. Go tell your story and watch them say “wow!”

Nailed your case study, but want to make your presentation even stronger? Avoid these common mistakes to ensure your audience gets the most out of it:

Overloading with information

A case study is not an encyclopedia. Overloading your presentation with excessive data, text or jargon can make it cumbersome and difficult for the audience to digest the key points. Stick to what’s essential and impactful. Need help making your data clear and impactful? Our data presentation templates can help! Find clear and engaging visuals to showcase your findings.

Lack of structure

Jumping haphazardly between points or topics can confuse your audience. A well-structured presentation, with a logical flow from introduction to conclusion, is crucial for effective communication.

Ignoring the audience

Different audiences have different needs and levels of understanding. Failing to adapt your presentation to your audience can result in a disconnect and a less impactful presentation.

Poor visual elements

While content is king, poor design or lack of visual elements can make your case study dull or hard to follow. Make sure you use high-quality images, graphs and other visual aids to support your narrative.

Not focusing on results

A case study aims to showcase a problem and its solution, but what most people care about are the results. Failing to highlight or adequately explain the outcomes can make your presentation fall flat.

How to start a case study presentation?

Starting a case study presentation effectively involves a few key steps:

- Grab attention : Open with a hook—an intriguing statistic, a provocative question or a compelling visual—to engage your audience from the get-go.

- Set the stage : Briefly introduce the subject, context and relevance of the case study to give your audience an idea of what to expect.

- Outline objectives : Clearly state what the case study aims to achieve. Are you solving a problem, proving a point or showcasing a success?

- Agenda : Give a quick outline of the key sections or topics you’ll cover to help the audience follow along.

- Set expectations : Let your audience know what you want them to take away from the presentation, whether it’s knowledge, inspiration or a call to action.

How to present a case study on PowerPoint and on Google Slides?

Presenting a case study on PowerPoint and Google Slides involves a structured approach for clarity and impact using presentation slides :

- Title slide : Start with a title slide that includes the name of the case study, your name and any relevant institutional affiliations.

- Introduction : Follow with a slide that outlines the problem or situation your case study addresses. Include a hook to engage the audience.

- Objectives : Clearly state the goals of the case study in a dedicated slide.

- Findings : Use charts, graphs and bullet points to present your findings succinctly.

- Analysis : Discuss what the findings mean, drawing on supporting data or secondary research as necessary.

- Conclusion : Summarize key takeaways and results.

- Q&A : End with a slide inviting questions from the audience.

What’s the role of analysis in a case study presentation?

The role of analysis in a case study presentation is to interpret the data and findings, providing context and meaning to them.

It helps your audience understand the implications of the case study, connects the dots between the problem and the solution and may offer recommendations for future action.

Is it important to include real data and results in the presentation?

Yes, including real data and results in a case study presentation is crucial to show experience, credibility and impact. Authentic data lends weight to your findings and conclusions, enabling the audience to trust your analysis and take your recommendations more seriously

How do I conclude a case study presentation effectively?

To conclude a case study presentation effectively, summarize the key findings, insights and recommendations in a clear and concise manner.

End with a strong call-to-action or a thought-provoking question to leave a lasting impression on your audience.

What’s the best way to showcase data in a case study presentation ?

The best way to showcase data in a case study presentation is through visual aids like charts, graphs and infographics which make complex information easily digestible, engaging and creative.

Don’t just report results, visualize them! This template for example lets you transform your social media case study into a captivating infographic that sparks conversation.

Choose the type of visual that best represents the data you’re showing; for example, use bar charts for comparisons or pie charts for parts of a whole.

Ensure that the visuals are high-quality and clearly labeled, so the audience can quickly grasp the key points.

Keep the design consistent and simple, avoiding clutter or overly complex visuals that could distract from the message.

Choose a template that perfectly suits your case study where you can utilize different visual aids for maximum impact.

Need more inspiration on how to turn numbers into impact with the help of infographics? Our ready-to-use infographic templates take the guesswork out of creating visual impact for your case studies with just a few clicks.

Related: 10+ Case Study Infographic Templates That Convert

Congrats on mastering the art of compelling case study presentations! This guide has equipped you with all the essentials, from structure and nuances to avoiding common pitfalls. You’re ready to impress any audience, whether in the boardroom, the classroom or beyond.

And remember, you’re not alone in this journey. Venngage’s Case Study Creator is your trusty companion, ready to elevate your presentations from ordinary to extraordinary. So, let your confidence shine, leverage your newly acquired skills and prepare to deliver presentations that truly resonate.

Go forth and make a lasting impact!

Discover popular designs

Brochure maker

White paper online

Newsletter creator

Flyer maker

Timeline maker

Letterhead maker

Mind map maker

Ebook maker

Home Blog Business How to Present a Case Study: Examples and Best Practices

How to Present a Case Study: Examples and Best Practices

Marketers, consultants, salespeople, and all other types of business managers often use case study analysis to highlight a success story, showing how an exciting problem can be or was addressed. But how do you create a compelling case study and then turn it into a memorable presentation? Get a lowdown from this post!

Table of Content s

- Why Case Studies are a Popular Marketing Technique

Popular Case Study Format Types

How to write a case study: a 4-step framework, how to do a case study presentation: 3 proven tips, how long should a case study be, final tip: use compelling presentation visuals, business case study examples, what is a case study .

Let’s start with this great case study definition by the University of South Caroline:

In the social sciences, the term case study refers to both a method of analysis and a specific research design for examining a problem, both of which can generalize findings across populations.

In simpler terms — a case study is investigative research into a problem aimed at presenting or highlighting solution(s) to the analyzed issues.

A standard business case study provides insights into:

- General business/market conditions

- The main problem faced

- Methods applied

- The outcomes gained using a specific tool or approach

Case studies (also called case reports) are also used in clinical settings to analyze patient outcomes outside of the business realm.

But this is a topic for another time. In this post, we’ll focus on teaching you how to write and present a business case, plus share several case study PowerPoint templates and design tips!

Why Case Studies are a Popular Marketing Technique

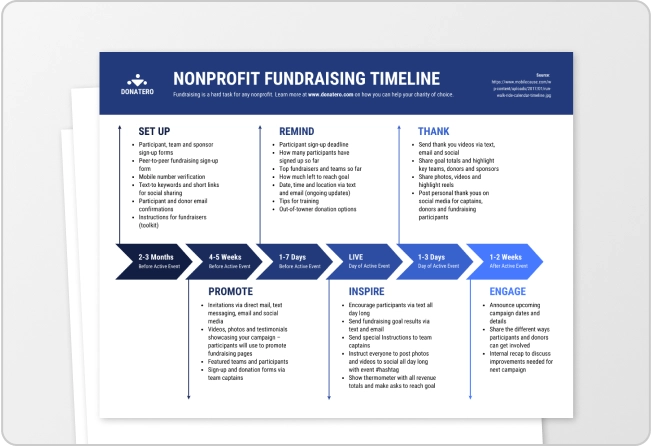

Besides presenting a solution to an internal issue, case studies are often used as a content marketing technique . According to a 2020 Content Marketing Institute report, 69% of B2B marketers use case studies as part of their marketing mix.

A case study informs the reader about a possible solution and soft-sells the results, which can be achieved with your help (e.g., by using your software or by partnering with your specialist).

For the above purpose, case studies work like a charm. Per the same report:

- For 9% of marketers, case studies are also the best method for nurturing leads.

- 23% admit that case studies are beneficial for improving conversions.

Moreover, case studies also help improve your brand’s credibility, especially in the current fake news landscape and dubious claims made without proper credit.

Ultimately, case studies naturally help build up more compelling, relatable stories and showcase your product benefits through the prism of extra social proof, courtesy of the case study subject.

Most case studies come either as a slide deck or as a downloadable PDF document.

Typically, you have several options to distribute your case study for maximum reach:

- Case study presentations — in-person, virtual, or pre-recorded, there are many times when a case study presentation comes in handy. For example, during client workshops, sales pitches, networking events, conferences, trade shows, etc.

- Dedicated website page — highlighting case study examples on your website is a great way to convert middle-on-the-funnel prospects. Google’s Think With Google case study section is a great example of a web case study design done right.

- Blog case studies — data-driven storytelling is a staunch way to stand apart from your competition by providing unique insights, no other brand can tell.

- Video case studies — video is a great medium for showcasing more complex business cases and celebrating customer success stories.

Once you decide on your case study format, the next step is collecting data and then translating it into a storyline. There are different case study methods and research approaches you can use to procure data.

But let’s say you already have all your facts straight and need to organize them in a clean copy for your presentation deck. Here’s how you should do it.

1. Identify the Problem

Every compelling case study research starts with a problem statement definition. While in business settings, there’s no need to explain your methodology in-depth; you should still open your presentation with a quick problem recap slide.

Be sure to mention:

- What’s the purpose of the case study? What will the audience learn?

- Set the scene. Explain the before, aka the problems someone was facing.

- Advertise the main issues and findings without highlighting specific details.

The above information should nicely fit in several paragraphs or 2-3 case study template slides

2. Explain the Solution

The bulk of your case study copy and presentation slides should focus on the provided solution(s). This is the time to speak at length about how the subject went from before to the glorious after.

Here are some writing prompts to help you articulate this better:

- State the subject’s main objective and goals. What outcomes were they after?

- Explain the main solution(s) provided. What was done? Why this, but not that?

- Mention if they tried any alternatives. Why did those work? Why were you better?

This part may take the longest to write. Don’t rush it and reiterate several times. Sprinkle in some powerful words and catchphrases to make your copy more compelling.

3. Collect Testimonials

Persuasive case studies feature the voice of customer (VoC) data — first-party testimonials and assessments of how well the solution works. These provide extra social proof and credibility to all the claims you are making.

So plan and schedule interviews with your subjects to collect their input and testimonials. Also, design your case study interview questions in a way that lets you obtain quantifiable results.

4. Package The Information in a Slide Deck

Once you have a rough first draft, try different business case templates and designs to see how these help structure all the available information.

As a rule of thumb, try to keep one big idea per slide. If you are talking about a solution, first present the general bullet points. Then give each solution a separate slide where you’ll provide more context and perhaps share some quantifiable results.

For example, if you look at case study presentation examples from AWS like this one about Stripe , you’ll notice that the slide deck has few texts and really focuses on the big picture, while the speaker provides extra context.

Need some extra case study presentation design help? Download our Business Case Study PowerPoint template with 100% editable slides.

Your spoken presentation (and public speaking skills ) are equally if not more important than the case study copy and slide deck. To make a strong business case, follow these quick techniques.

Focus on Telling a Great Story

A case study is a story of overcoming a challenge, and achieving something grand. Your delivery should reflect that. Step away from the standard “features => benefits” sales formula. Instead, make your customer the hero of the study. Describe the road they went through and how you’ve helped them succeed.

The premises of your story can be as simple as:

- Help with overcoming a hurdle

- Gaining major impact

- Reaching a new milestone

- Solving a persisting issue no one else code

Based on the above, create a clear story arc. Show where your hero started. Then explain what type of journey they went through. Inject some emotions into the mix to make your narrative more relatable and memorable.

Experiment with Copywriting Formulas

Copywriting is the art and science of organizing words into compelling and persuasive combinations that help readers retain the right ideas.

To ensure that the audience retains the right takeaways from your case study presentation, you can try using some of the classic copywriting formulas to structure your delivery. These include:

- AIDCA — short for A ttention, I nterest, D esire, C onviction, and A ction. First, grab the audience’s attention by addressing the major problem. Next, pique their interest with some teaser facts. Spark their desire by showing that you know the right way out. Then, show a conviction that you know how to solve the issue—finally, prompt follow-up action such as contacting you to learn more.

- PADS — is short for Problem, Agitation, Discredit, or Solution. This is more of a sales approach to case study narration. Again, you start with a problem, agitate about its importance, discredit why other solutions won’t cut it, and then present your option.

- 4Ps — short for P roblem, P romise, P roof, P roposal. This is a middle-ground option that prioritizes storytelling over hard pitches. Set the scene first with a problem. Then make a promise of how you can solve it. Show proof in the form of numbers, testimonials, and different scenarios. Round it up with a proposal for getting the same outcomes.

Take an Emotion-Inducing Perspective

The key to building a strong rapport with an audience is showing that you are one of them and fully understand what they are going through.

One of the ways to build this connection is by speaking from an emotion-inducing perspective. This is best illustrated with an example:

- A business owner went to the bank

- A business owner came into a bank branch

In the second case, the wording prompts listeners to paint a mental picture from the perspective of the bank employees — a role you’d like them to relate to. By placing your audience in the right visual perspective, you can make them more receptive to your pitches.

One common question that arises when creating a case study is determining its length. The length of a case study can vary depending on the complexity of the problem and the level of detail you want to provide. Here are some general guidelines to help you decide how long your case study should be:

- Concise and Informative: A good case study should be concise and to the point. Avoid unnecessary fluff and filler content. Focus on providing valuable information and insights.

- Tailor to Your Audience: Consider your target audience when deciding the length. If you’re presenting to a technical audience, you might include more in-depth technical details. For a non-technical audience, keep it more high-level and accessible.

- Cover Key Points: Ensure that your case study covers the key points effectively. These include the problem statement, the solution, and the outcomes. Provide enough information for the reader to understand the context and the significance of your case.

- Visuals: Visual elements such as charts, graphs, images, and diagrams can help convey information more effectively. Use visuals to supplement your written content and make complex information easier to understand.

- Engagement: Keep your audience engaged. A case study that is too long may lose the reader’s interest. Make sure the content is engaging and holds the reader’s attention throughout.

- Consider the Format: Depending on the format you choose (e.g., written document, presentation, video), the ideal length may vary. For written case studies, aim for a length that can be easily read in one sitting.

In general, a written case study for business purposes often falls in the range of 1,000 to 2,000 words. However, this is not a strict rule, and the length can be shorter or longer based on the factors mentioned above.

Our brain is wired to process images much faster than text. So when you are presenting a case study, always look for an opportunity to tie in some illustrations such as:

- A product demo/preview

- Processes chart

- Call-out quotes or numbers

- Custom illustrations or graphics

- Customer or team headshots

Use icons to minimize the volume of text. Also, opt for readable fonts that can look good in a smaller size too.

To better understand how to create an effective business case study, let’s explore some examples of successful case studies:

Apple Inc.: Apple’s case study on the launch of the iPhone is a classic example. It covers the problem of a changing mobile phone market, the innovative solution (the iPhone), and the outstanding outcomes, such as market dominance and increased revenue.

Tesla, Inc.: Tesla’s case study on electric vehicles and sustainable transportation is another compelling example. It addresses the problem of environmental concerns and the need for sustainable transportation solutions. The case study highlights Tesla’s electric cars as the solution and showcases the positive impact on reducing carbon emissions.

Amazon.com: Amazon’s case study on customer-centricity is a great illustration of how the company transformed the e-commerce industry. It discusses the problem of customer dissatisfaction with traditional retail, Amazon’s customer-focused approach as the solution, and the remarkable outcomes in terms of customer loyalty and market growth.

Coca-Cola: Coca-Cola’s case study on brand evolution is a valuable example. It outlines the challenge of adapting to changing consumer preferences and demographics. The case study demonstrates how Coca-Cola continually reinvented its brand to stay relevant and succeed in the global market.

Airbnb: Airbnb’s case study on the sharing economy is an intriguing example. It addresses the problem of travelers seeking unique and affordable accommodations. The case study presents Airbnb’s platform as the solution and highlights its impact on the hospitality industry and the sharing economy.

These examples showcase the diversity of case studies in the business world and how they effectively communicate problems, solutions, and outcomes. When creating your own business case study, use these examples as inspiration and tailor your approach to your specific industry and target audience.

Finally, practice your case study presentation several times — solo and together with your team — to collect feedback and make last-minute refinements!

1. Business Case Study PowerPoint Template

To efficiently create a Business Case Study it’s important to ask all the right questions and document everything necessary, therefore this PowerPoint Template will provide all the sections you need.

Use This Template

2. Medical Case Study PowerPoint Template

3. Medical Infographics PowerPoint Templates

4. Success Story PowerPoint Template

5. Detective Research PowerPoint Template

6. Animated Clinical Study PowerPoint Templates

Like this article? Please share

Business Intelligence, Business Planning, Business PowerPoint Templates, Content Marketing, Feasibility Study, Marketing, Marketing Strategy Filed under Business

Related Articles

Filed under Business • April 22nd, 2024

Setting SMART Goals – A Complete Guide (with Examples + Free Templates)

This guide on SMART goals introduces the concept, explains the definition and its meaning, along the main benefits of using the criteria for a business.

Filed under Business • February 2nd, 2024

Business Plan Presentations: A Guide

Learn all that’s required to produce a high-quality business plan presentation in this guide. Suggested templates and examples are included.

Filed under Business • January 16th, 2024

The OODA Loop Decision-Making Model and How to Use it for Presentations

OODA Loop is a model that supports people and companies when defining important decisions in teams or individuals. See here how to apply it in presentation slide design.

Leave a Reply

How to make an oral case presentation to healthcare colleagues

The content and delivery of a patient case for education and evidence-based care discussions in clinical practice.

BSIP SA / Alamy Stock Photo

A case presentation is a detailed narrative describing a specific problem experienced by one or more patients. Pharmacists usually focus on the medicines aspect , for example, where there is potential harm to a patient or proven benefit to the patient from medication, or where a medication error has occurred. Case presentations can be used as a pedagogical tool, as a method of appraising the presenter’s knowledge and as an opportunity for presenters to reflect on their clinical practice [1] .

The aim of an oral presentation is to disseminate information about a patient for the purpose of education, to update other members of the healthcare team on a patient’s progress, and to ensure the best, evidence-based care is being considered for their management.

Within a hospital, pharmacists are likely to present patients on a teaching or daily ward round or to a senior pharmacist or colleague for the purpose of asking advice on, for example, treatment options or complex drug-drug interactions, or for referral.

Content of a case presentation

As a general structure, an oral case presentation may be divided into three phases [2] :

- Reporting important patient information and clinical data;

- Analysing and synthesising identified issues (this is likely to include producing a list of these issues, generally termed a problem list);

- Managing the case by developing a therapeutic plan.

Specifically, the following information should be included [3] :

Patient and complaint details

Patient details: name, sex, age, ethnicity.

Presenting complaint: the reason the patient presented to the hospital (symptom/event).

History of presenting complaint: highlighting relevant events in chronological order, often presented as how many days ago they occurred. This should include prior admission to hospital for the same complaint.

Review of organ systems: listing positive or negative findings found from the doctor’s assessment that are relevant to the presenting complaint.

Past medical and surgical history

Social history: including occupation, exposures, smoking and alcohol history, and any recreational drug use.

Medication history, including any drug allergies: this should include any prescribed medicines, medicines purchased over-the-counter, any topical preparations used (including eye drops, nose drops, inhalers and nasal sprays) and any herbal or traditional remedies taken.

Sexual history: if this is relevant to the presenting complaint.

Details from a physical examination: this includes any relevant findings to the presenting complaint and should include relevant observations.

Laboratory investigation and imaging results: abnormal findings are presented.

Assessment: including differential diagnosis.

Plan: including any pharmaceutical care issues raised and how these should be resolved, ongoing management and discharge planning.

Any discrepancies between the current management of the patient’s conditions and evidence-based recommendations should be highlighted and reasons given for not adhering to evidence-based medicine ( see ‘Locating the evidence’ ).

Locating the evidence

The evidence base for the therapeutic options available should always be considered. There may be local guidance available within the hospital trust directing the management of the patient’s presenting condition. Pharmacists often contribute to the development of such guidelines, especially if medication is involved. If no local guidelines are available, the next step is to refer to national guidance. This is developed by a steering group of experts, for example, the British HIV Association or the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . If the presenting condition is unusual or rare, for example, acute porphyria, and there are no local or national guidelines available, a literature search may help locate articles or case studies similar to the case.

Giving a case presentation

Currently, there are no available acknowledged guidelines or systematic descriptions of the structure, language and function of the oral case presentation [4] and therefore there is no standard on how the skills required to prepare or present a case are taught. Most individuals are introduced to this concept at undergraduate level and then build on their skills through practice-based learning.

A case presentation is a narrative of a patient’s care, so it is vital the presenter has familiarity with the patient, the case and its progression. The preparation for the presentation will depend on what information is to be included.

Generally, oral case presentations are brief and should be limited to 5–10 minutes. This may be extended if the case is being presented as part of an assessment compared with routine everyday working ( see ‘Case-based discussion’ ). The audience should be interested in what is being said so the presenter should maintain this engagement through eye contact, clear speech and enthusiasm for the case.

It is important to stick to the facts by presenting the case as a factual timeline and not describing how things should have happened instead. Importantly, the case should always be concluded and should include an outcome of the patient’s care [5] .

An example of an oral case presentation, given by a pharmacist to a doctor, is available here .

A successful oral case presentation allows the audience to garner the right amount of patient information in the most efficient way, enabling a clinically appropriate plan to be developed. The challenge lies with the fact that the content and delivery of this will vary depending on the service, and clinical and audience setting [3] . A practitioner with less experience may find understanding the balance between sufficient information and efficiency of communication difficult, but regular use of the oral case presentation tool will improve this skill.

Tailoring case presentations to your audience

Most case presentations are not tailored to a specific audience because the same type of information will usually need to be conveyed in each case.

However, case presentations can be adapted to meet the identified learning needs of the target audience, if required for training purposes. This method involves varying the content of the presentation or choosing specific cases to present that will help achieve a set of objectives [6] . For example, if a requirement to learn about the management of acute myocardial infarction has been identified by the target audience, then the presenter may identify a case from the cardiology ward to present to the group, as opposed to presenting a patient reviewed by that person during their normal working practice.

Alternatively, a presenter could focus on a particular condition within a case, which will dictate what information is included. For example, if a case on asthma is being presented, the focus may be on recent use of bronchodilator therapy, respiratory function tests (including peak expiratory flow rate), symptoms related to exacerbation of airways disease, anxiety levels, ability to talk in full sentences, triggers to worsening of symptoms, and recent exposure to allergens. These may not be considered relevant if presenting the case on an unrelated condition that the same patient has, for example, if this patient was admitted with a hip fracture and their asthma was well controlled.

Case-based discussion

The oral case presentation may also act as the basis of workplace-based assessment in the form of a case-based discussion. In the UK, this forms part of many healthcare professional bodies’ assessment of clinical practice, for example, medical professional colleges.

For pharmacists, a case-based discussion forms part of the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) Foundation and Advanced Practice assessments . Mastery of the oral case presentation skill could provide useful preparation for this assessment process.

A case-based discussion would include a pharmaceutical needs assessment, which involves identifying and prioritising pharmaceutical problems for a particular patient. Evidence-based guidelines relevant to the specific medical condition should be used to make treatment recommendations, and a plan to monitor the patient once therapy has started should be developed. Professionalism is an important aspect of case-based discussion — issues must be prioritised appropriately and ethical and legal frameworks must be referred to [7] . A case-based discussion would include broadly similar content to the oral case presentation, but would involve further questioning of the presenter by the assessor to determine the extent of the presenter’s knowledge of the specific case, condition and therapeutic strategies. The criteria used for assessment would depend on the level of practice of the presenter but, for pharmacists, this may include assessment against the RPS Foundation or Pharmacy Frameworks .

Acknowledgement

With thanks to Aamer Safdar for providing the script for the audio case presentation.

Reading this article counts towards your CPD

You can use the following forms to record your learning and action points from this article from Pharmaceutical Journal Publications.

Your CPD module results are stored against your account here at The Pharmaceutical Journal . You must be registered and logged into the site to do this. To review your module results, go to the ‘My Account’ tab and then ‘My CPD’.

Any training, learning or development activities that you undertake for CPD can also be recorded as evidence as part of your RPS Faculty practice-based portfolio when preparing for Faculty membership. To start your RPS Faculty journey today, access the portfolio and tools at www.rpharms.com/Faculty

If your learning was planned in advance, please click:

If your learning was spontaneous, please click:

[1] Onishi H. The role of case presentation for teaching and learning activities. Kaohsiung J Med Sci 2008;24:356–360. doi: 10.1016/s1607-551x(08)70132–3

[2] Edwards JC, Brannan JR, Burgess L et al . Case presentation format and clinical reasoning: a strategy for teaching medical students. Medical Teacher 1987;9:285–292. doi: 10.3109/01421598709034790

[3] Goldberg C. A practical guide to clinical medicine: overview and general information about oral presentation. 2009. University of California, San Diego. Available from: https://meded.ecsd.edu/clinicalmed.oral.htm (accessed 5 December 2015)

[4] Chan MY. The oral case presentation: toward a performance-based rhetorical model for teaching and learning. Medical Education Online 2015;20. doi: 10.3402/meo.v20.28565

[5] McGee S. Medicine student programs: oral presentation guidelines. Learning & Scholarly Technologies, University of Washington. Available from: https://catalyst.uw.edu/workspace/medsp/30311/202905 (accessed 7 December 2015)

[6] Hays R. Teaching and Learning in Clinical Settings. 2006;425. Oxford: Radcliffe Publishing Ltd.

[7] Royal Pharmaceutical Society. Tips for assessors for completing case-based discussions. 2015. Available from: http://www.rpharms.com/help/case_based_discussion.htm (accessed 30 December 2015)

You might also be interested in…

How to demonstrate empathy and compassion in a pharmacy setting

Be more proactive to convince medics, pharmacists urged

How pharmacists can encourage patient adherence to medicines

- - Google Chrome

Intended for healthcare professionals

- Access provided by Google Indexer

- My email alerts

- BMA member login

- Username * Password * Forgot your log in details? Need to activate BMA Member Log In Log in via OpenAthens Log in via your institution

Search form

- Advanced search

- Search responses

- Search blogs

- Writing a case report...

Writing a case report in 10 steps

- Related content

- Peer review

- Victoria Stokes , foundation year 2 doctor, trauma and orthopaedics, Basildon Hospital ,

- Caroline Fertleman , paediatrics consultant, The Whittington Hospital NHS Trust

- victoria.stokes1{at}nhs.net

Victoria Stokes and Caroline Fertleman explain how to turn an interesting case or unusual presentation into an educational report

It is common practice in medicine that when we come across an interesting case with an unusual presentation or a surprise twist, we must tell the rest of the medical world. This is how we continue our lifelong learning and aid faster diagnosis and treatment for patients.

It usually falls to the junior to write up the case, so here are a few simple tips to get you started.

First steps

Begin by sitting down with your medical team to discuss the interesting aspects of the case and the learning points to highlight. Ideally, a registrar or middle grade will mentor you and give you guidance. Another junior doctor or medical student may also be keen to be involved. Allocate jobs to split the workload, set a deadline and work timeframe, and discuss the order in which the authors will be listed. All listed authors should contribute substantially, with the person doing most of the work put first and the guarantor (usually the most senior team member) at the end.

Getting consent

Gain permission and written consent to write up the case from the patient or parents, if your patient is a child, and keep a copy because you will need it later for submission to journals.

Information gathering

Gather all the information from the medical notes and the hospital’s electronic systems, including copies of blood results and imaging, as medical notes often disappear when the patient is discharged and are notoriously difficult to find again. Remember to anonymise the data according to your local hospital policy.

Write up the case emphasising the interesting points of the presentation, investigations leading to diagnosis, and management of the disease/pathology. Get input on the case from all members of the team, highlighting their involvement. Also include the prognosis of the patient, if known, as the reader will want to know the outcome.

Coming up with a title

Discuss a title with your supervisor and other members of the team, as this provides the focus for your article. The title should be concise and interesting but should also enable people to find it in medical literature search engines. Also think about how you will present your case study—for example, a poster presentation or scientific paper—and consider potential journals or conferences, as you may need to write in a particular style or format.

Background research

Research the disease/pathology that is the focus of your article and write a background paragraph or two, highlighting the relevance of your case report in relation to this. If you are struggling, seek the opinion of a specialist who may know of relevant articles or texts. Another good resource is your hospital library, where staff are often more than happy to help with literature searches.

How your case is different

Move on to explore how the case presented differently to the admitting team. Alternatively, if your report is focused on management, explore the difficulties the team came across and alternative options for treatment.

Finish by explaining why your case report adds to the medical literature and highlight any learning points.

Writing an abstract

The abstract should be no longer than 100-200 words and should highlight all your key points concisely. This can be harder than writing the full article and needs special care as it will be used to judge whether your case is accepted for presentation or publication.

Discuss with your supervisor or team about options for presenting or publishing your case report. At the very least, you should present your article locally within a departmental or team meeting or at a hospital grand round. Well done!

Competing interests: We have read and understood BMJ’s policy on declaration of interests and declare that we have no competing interests.

Researched by Consultants from Top-Tier Management Companies

Powerpoint Templates

Icon Bundle

Kpi Dashboard

Professional

Business Plans

Swot Analysis

Gantt Chart

Business Proposal

Marketing Plan

Project Management

Business Case

Business Model

Cyber Security

Business PPT

Digital Marketing

Digital Transformation

Human Resources

Product Management

Artificial Intelligence

Company Profile

Acknowledgement PPT

PPT Presentation

Reports Brochures

One Page Pitch

Interview PPT

All Categories

Top 7 Medical Case Presentation Templates with Samples and Examples

Sarojit Hazra

How does information expand beyond essential recollection? Facts alone can diminish in value over time. Context and implementation are crucial to form deep connections and roots. Here comes the role of case studies for clinical personnel in the medical field.

In the always-growing healthcare industry, medical case presentation is essential as it is a suggestion for new researchers. A medical case study is a report where a medical practitioner shares a patient's case. It comprises every detail related to patients. It is beneficial for describing a new medical condition, management options, or treatment for diseases.

Medical case presentations contribute significantly to the evolution of medical knowledge and research.

Case study analysis is essential for every business or industry, like the medical industry. It helps in managing the twists and turns of the industry. Want to take some ideas? Have a look at SlideTeam’s blog Case Analysis Templates .

Let us highlight some significant benefits of medical case presentation:

- Case study presentations are extremely good at depicting realistic clinical frameworks.

- It helps to enhance student participation alongside the joy of learning.

- These are ideal for sharing the latest information on the clinical landscape.

- It promotes critical thinking.

- It can also make better clinical outcomes.

If you are in the healthcare sector, another important tool is the medical dashboard. For a deeper insight, quickly take a look at Medical dashboard Templates .

Each of the slides is 100% editable and customizable. The 100% customizable nature of the templates allows you to edit your presentations. The content-ready slides give you the much-needed structure. Below, let’s explore a wide array of ready to use, content ready medical case presentation templates fit for your organization.

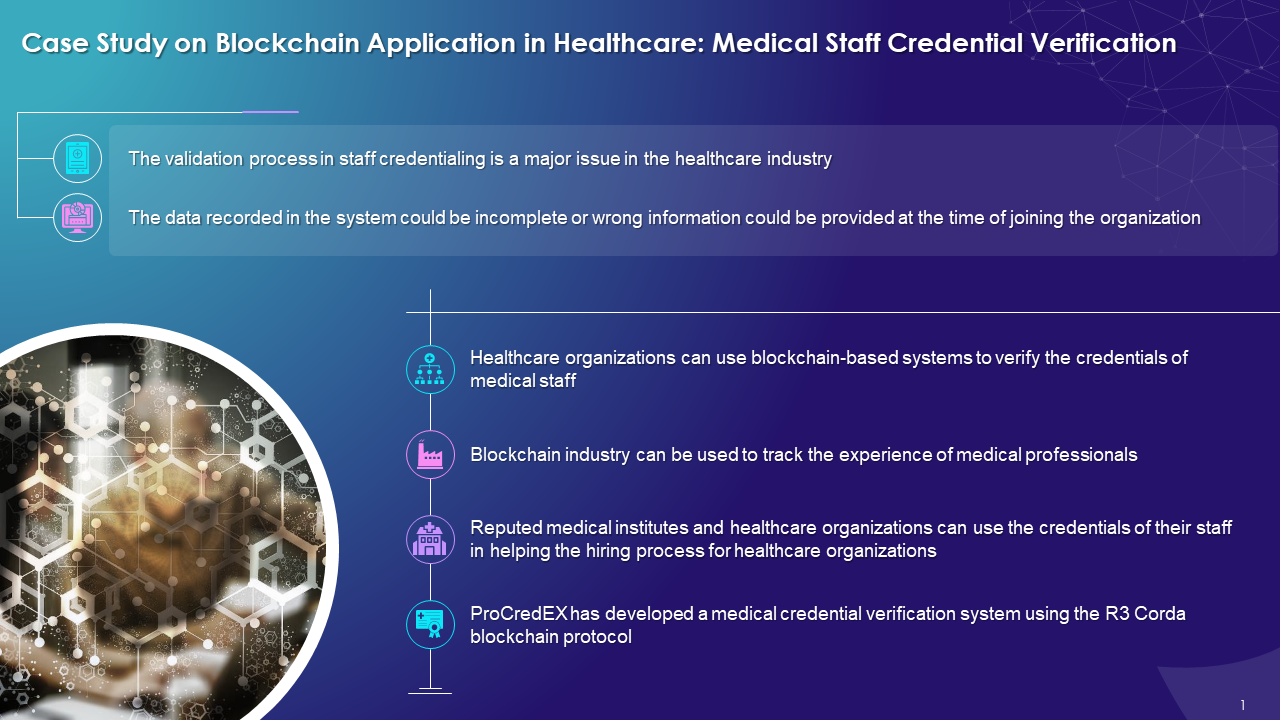

Template 1: Case Study on Blockchain Application in Healthcare: Medical Staff Credential Verification

Blockchain is becoming a potential solution to verify medical credentials. Though these are open to the public, they can be restricted through permissions. Are you finding it difficult to understand and implement? SlideTeam introduces this PPT Template that highlights how to operationalize medical staff verification process using blockchain technology. It explains that healthcare-based systems can also be used to verify the credentials of medical staff. Solutions-based blockchain to track the experiences of medical professionals. The PPT slides are designed with suitable icons, designs, graphs and other relevant material. Grab it quickly and draft your case study as per the client’s requirements.

Click to Download

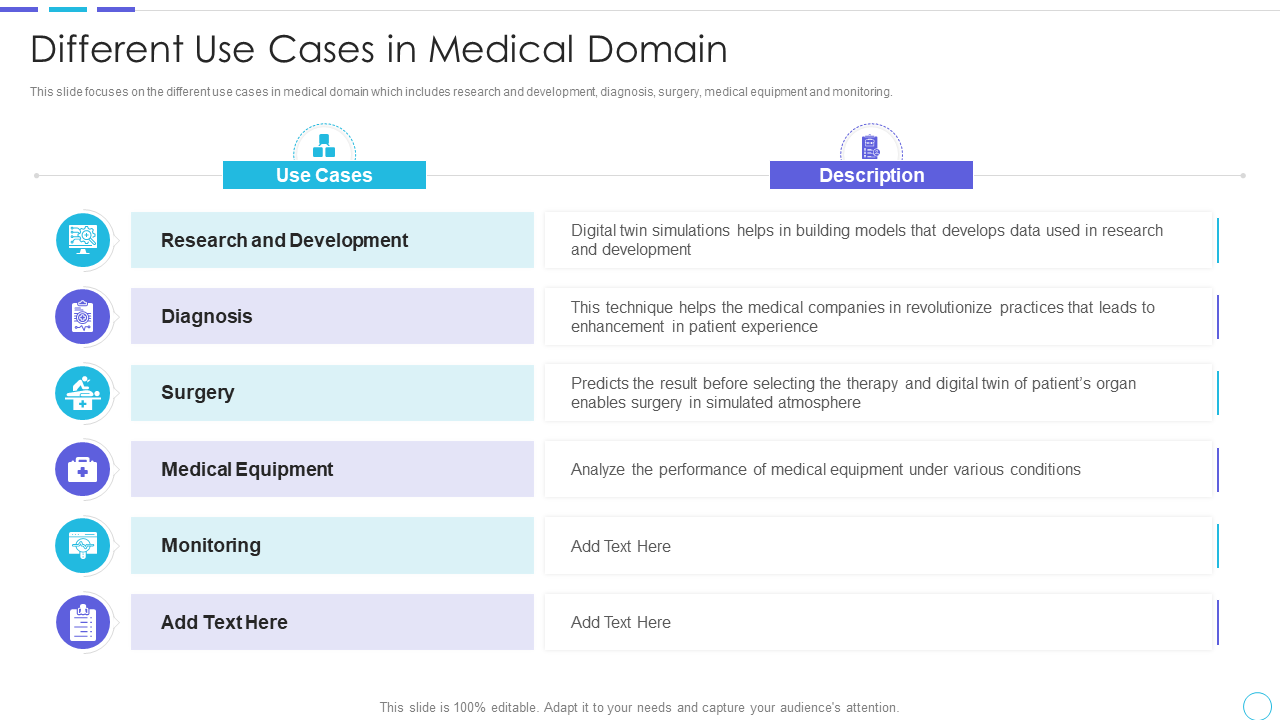

Template 2: Cost Benefits IOT Digital Twins Implementation Use Cases in the Medical Domain

This PPT template is designed to focus on the use cases in the medical domain, including research and development, diagnosis, surgery, medical equipment, etc. The slide offers a brief description of the mentioned use cases to understand the scenario better. Use it as an essential tool and captivate your audience. Get it Now!

Template 3: Major Use Cases for Tracking Medical Assets Asset Tracking and Management IoT

Want to simplify medical complexities? The asset tracking solution is here to accompany you. It enables the medical sector to locate patients, clinicians, and medications more accurately and quickly. IoT development has made this task much more accessible by guiding you through every significant aspect of a medical asset-tracking solution. Introducing our slide exhibiting use cases of medical tools that can be tracked with IoT technology . Medical assets, including medical tools, medical equipment tracking, medications , etc., are shown in the layout with their use cases and impacts. Each topic is depicted in separate tables with appropriate icons.

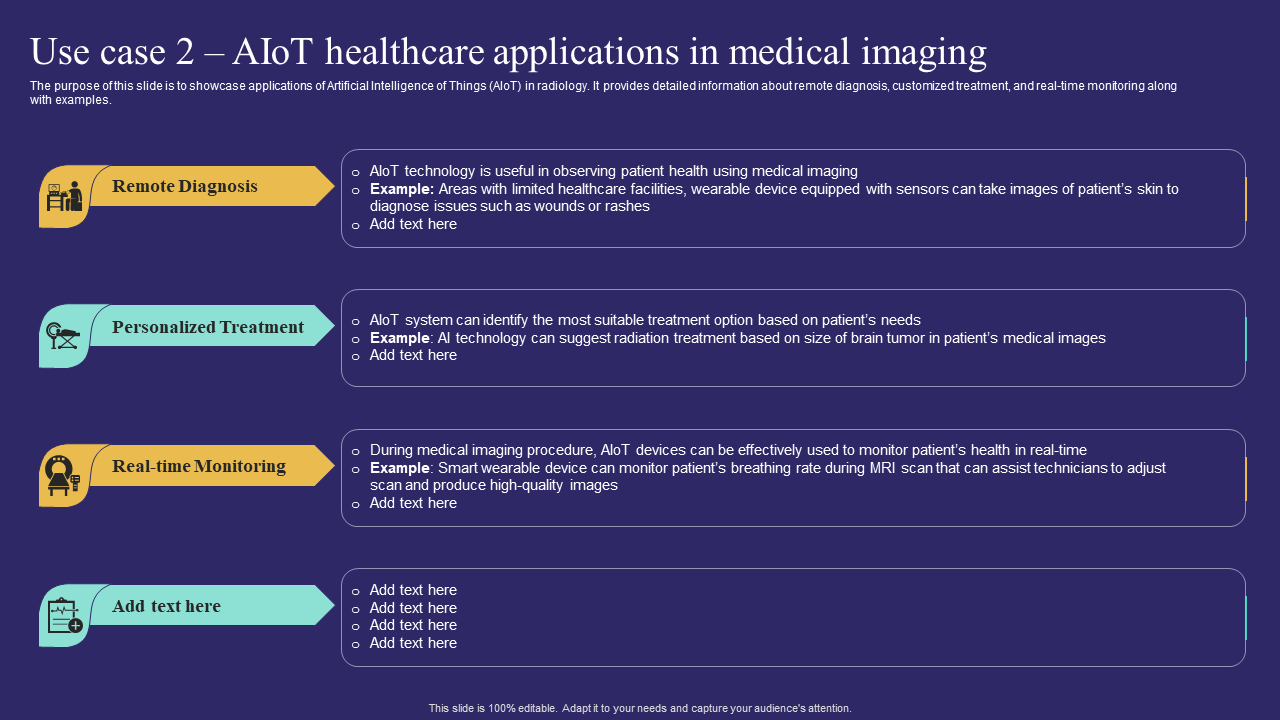

Template 4: AIoT Healthcare Applications in Medical Imaging

AIoT is making the medical sector smarter and wiser to improve data management and human-machine interaction. When AIoT is applied to healthcare, enables virtual monitoring and accurate diagnosis of patients to develop a personalized patient experience. Here, we introduce our premium PPT Templates showcasing applications of Artificial Intelligence of Things (AIoT) in radiology. You can provide detailed information about remote diagnosis , personalized treatment , and real-time monitoring. Adapt it now to increase your presentation threshold and educate your audience.

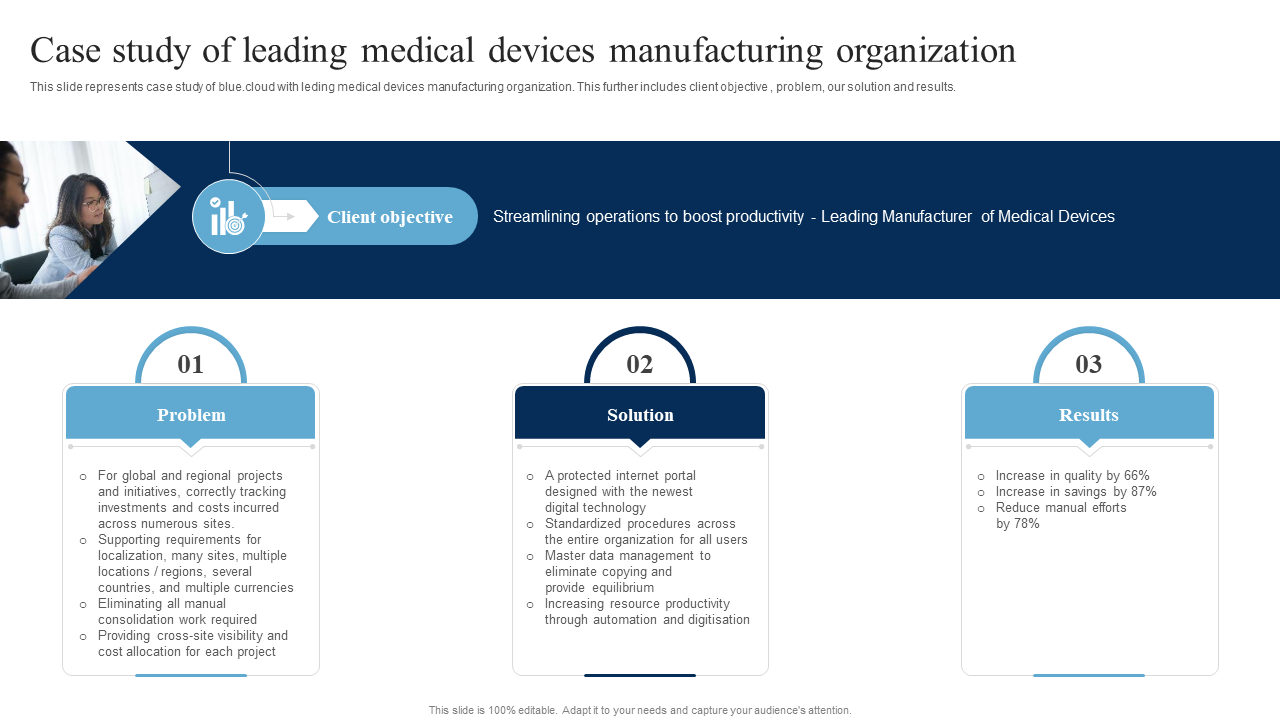

Template 5: Case Study of Leading Medical Devices Manufacturing Organization

An array of disruptive themes is shaping the medical device industry, and cloud computing is one of them. Soon, cloud computing will have a more significant impact on this industry. So, for your convenience, we are presenting our slide covering a case study of blue cloud with lending medical devices manufacturing organization. It covers significant topics like client objective, problem, our solution, and results chronologically. Consisting of three essential stages, this template is excellent for educating and enticing your audience.

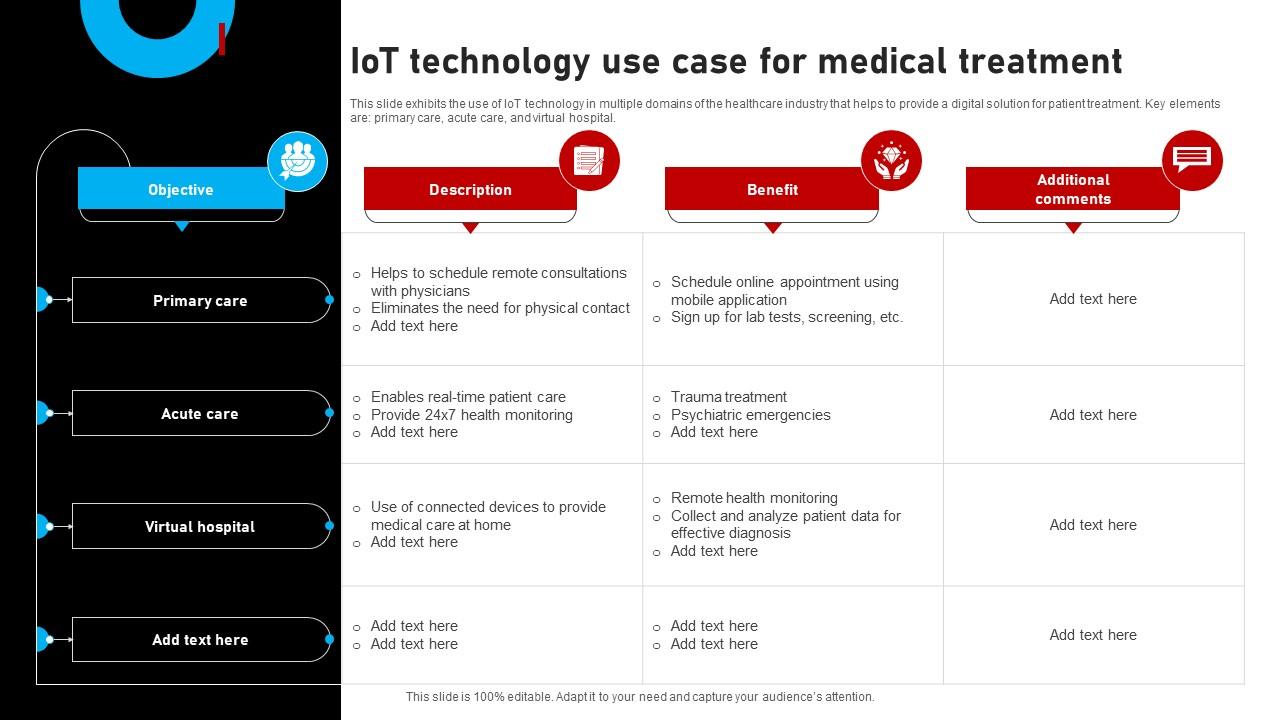

Template 6: IoT Technology Use Case for Medical Treatment

IoT, or the Internet of Things, is gaining significance across industries, and the medical sector is no exception. It has taken medical treatment to a new level. This custom-built PowerPoint Template exhibits the use of IoT technology in domains of the healthcare industry. It provides a digital solution for patient treatment. The key elements are primary care, acute care, virtual hospital, etc., which are depicted along with descriptions, benefits, and additional comments. Each illustration is highlighted, colored and has a relevant icon for instantaneous identification.

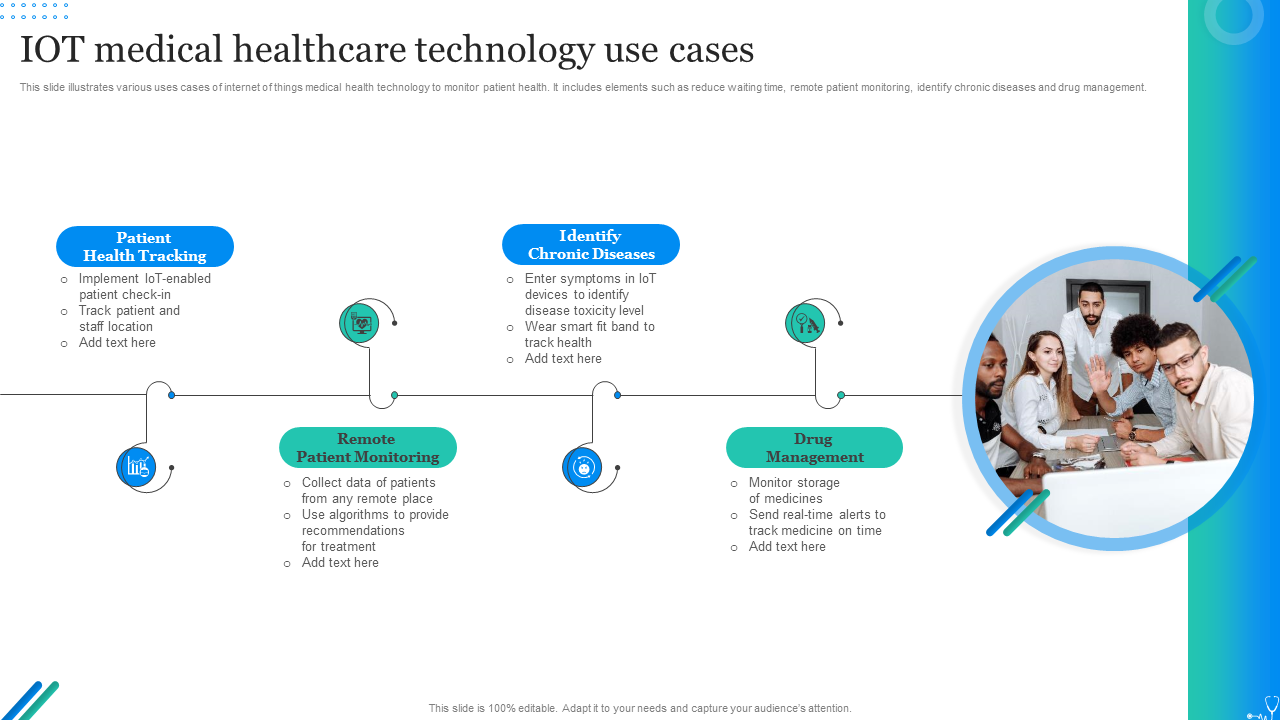

Template 7: IoT Medical Healthcare Technology Use Cases

The transformation of healthcare into digital healthcare has resulted in the rise of IoMT, or medical IoT . It refers to connected devices in medical healthcare and has become one of the fastest-growing industries in the IoT market. It would help if you dived deeper to manage, monitor, and preserve IoT devices in medical healthcare. This PPT presentation demonstrates uses of IoT Medical Healthcare Technology in monitoring patient health. Moreover, the slide includes remote patient monitoring, reduced waiting time, identifying chronic diseases, and drug management. Download this template design and present your case study with ultimate professionalism.

HEALTH CONSULTATION WILL BE QUICKER, SAFER AND SECURE

Case studies have a great history as an educational tool for clinicians. These are highly beneficial for nurturing deeper insights and learning. Access to such visually appealing and comprehensively presented Top 7 Medical Case Presentation Templates enables medical professionals to quickly present their patients' case studies. Be it tracking of medical assets, application of IoT in the clinical field, IoT medical healthcare technology uses, and so on, these templates serve as essential equipment in implementing all.

P.S. For perfection and success, you should dig into SlideTeam's fantastic blog, Medical Report Templates .

Related posts:

- How to Design the Perfect Service Launch Presentation [Custom Launch Deck Included]

- Quarterly Business Review Presentation: All the Essential Slides You Need in Your Deck

- [Updated 2023] How to Design The Perfect Product Launch Presentation [Best Templates Included]

- 99% of the Pitches Fail! Find Out What Makes Any Startup a Success

Liked this blog? Please recommend us

Top 10 Training Framework Templates with Examples and Samples

Top 5 Product Strategy Framework Templates with Samples and Examples

This form is protected by reCAPTCHA - the Google Privacy Policy and Terms of Service apply.

Digital revolution powerpoint presentation slides

Sales funnel results presentation layouts

3d men joinning circular jigsaw puzzles ppt graphics icons

Business Strategic Planning Template For Organizations Powerpoint Presentation Slides

Future plan powerpoint template slide

Project Management Team Powerpoint Presentation Slides

Brand marketing powerpoint presentation slides

Launching a new service powerpoint presentation with slides go to market

Agenda powerpoint slide show

Four key metrics donut chart with percentage

Engineering and technology ppt inspiration example introduction continuous process improvement

Meet our team representing in circular format

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it's official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you're on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

- Browse Titles

NCBI Bookshelf. A service of the National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health.

StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan-.

StatPearls [Internet].

Case study: 24-year-old male presenting with polyarthralgias.

Anusha Vakiti ; Saad Javed ; Kevin C. King .

Affiliations

Last Update: February 20, 2023 .

- Case Presentation