- Patient Care & Health Information

- Tests & Procedures

- Feminizing surgery

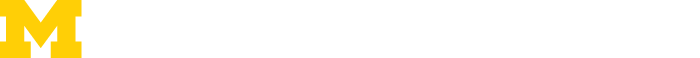

Feminizing surgery, also called gender-affirming surgery or gender-confirmation surgery, involves procedures that help better align the body with a person's gender identity. Feminizing surgery includes several options, such as top surgery to increase the size of the breasts. That procedure also is called breast augmentation. Bottom surgery can involve removal of the testicles, or removal of the testicles and penis and the creation of a vagina, labia and clitoris. Facial procedures or body-contouring procedures can be used as well.

Not everybody chooses to have feminizing surgery. These surgeries can be expensive, carry risks and complications, and involve follow-up medical care and procedures. Certain surgeries change fertility and sexual sensations. They also may change how you feel about your body.

Your health care team can talk with you about your options and help you weigh the risks and benefits.

Products & Services

- A Book: Mayo Clinic Family Health Book, 5th Edition

- Available Sexual Health Solutions at Mayo Clinic Store

- Newsletter: Mayo Clinic Health Letter — Digital Edition

Why it's done

Many people seek feminizing surgery as a step in the process of treating discomfort or distress because their gender identity differs from their sex assigned at birth. The medical term for this is gender dysphoria.

For some people, having feminizing surgery feels like a natural step. It's important to their sense of self. Others choose not to have surgery. All people relate to their bodies differently and should make individual choices that best suit their needs.

Feminizing surgery may include:

- Removal of the testicles alone. This is called orchiectomy.

- Removal of the penis, called penectomy.

- Removal of the testicles.

- Creation of a vagina, called vaginoplasty.

- Creation of a clitoris, called clitoroplasty.

- Creation of labia, called labioplasty.

- Breast surgery. Surgery to increase breast size is called top surgery or breast augmentation. It can be done through implants, the placement of tissue expanders under breast tissue, or the transplantation of fat from other parts of the body into the breast.

- Plastic surgery on the face. This is called facial feminization surgery. It involves plastic surgery techniques in which the jaw, chin, cheeks, forehead, nose, and areas surrounding the eyes, ears or lips are changed to create a more feminine appearance.

- Tummy tuck, called abdominoplasty.

- Buttock lift, called gluteal augmentation.

- Liposuction, a surgical procedure that uses a suction technique to remove fat from specific areas of the body.

- Voice feminizing therapy and surgery. These are techniques used to raise voice pitch.

- Tracheal shave. This surgery reduces the thyroid cartilage, also called the Adam's apple.

- Scalp hair transplant. This procedure removes hair follicles from the back and side of the head and transplants them to balding areas.

- Hair removal. A laser can be used to remove unwanted hair. Another option is electrolysis, a procedure that involves inserting a tiny needle into each hair follicle. The needle emits a pulse of electric current that damages and eventually destroys the follicle.

Your health care provider might advise against these surgeries if you have:

- Significant medical conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Behavioral health conditions that haven't been addressed.

- Any condition that limits your ability to give your informed consent.

Like any other type of major surgery, many types of feminizing surgery pose a risk of bleeding, infection and a reaction to anesthesia. Other complications might include:

- Delayed wound healing

- Fluid buildup beneath the skin, called seroma

- Bruising, also called hematoma

- Changes in skin sensation such as pain that doesn't go away, tingling, reduced sensation or numbness

- Damaged or dead body tissue — a condition known as tissue necrosis — such as in the vagina or labia

- A blood clot in a deep vein, called deep vein thrombosis, or a blood clot in the lung, called pulmonary embolism

- Development of an irregular connection between two body parts, called a fistula, such as between the bladder or bowel into the vagina

- Urinary problems, such as incontinence

- Pelvic floor problems

- Permanent scarring

- Loss of sexual pleasure or function

- Worsening of a behavioral health problem

Certain types of feminizing surgery may limit or end fertility. If you want to have biological children and you're having surgery that involves your reproductive organs, talk to your health care provider before surgery. You may be able to freeze sperm with a technique called sperm cryopreservation.

How you prepare

Before surgery, you meet with your surgeon. Work with a surgeon who is board certified and experienced in the procedures you want. Your surgeon talks with you about your options and the potential results. The surgeon also may provide information on details such as the type of anesthesia that will be used during surgery and the kind of follow-up care that you may need.

Follow your health care team's directions on preparing for your procedures. This may include guidelines on eating and drinking. You may need to make changes in the medicine you take and stop using nicotine, including vaping, smoking and chewing tobacco.

Because feminizing surgery might cause physical changes that cannot be reversed, you must give informed consent after thoroughly discussing:

- Risks and benefits

- Alternatives to surgery

- Expectations and goals

- Social and legal implications

- Potential complications

- Impact on sexual function and fertility

Evaluation for surgery

Before surgery, a health care provider evaluates your health to address any medical conditions that might prevent you from having surgery or that could affect the procedure. This evaluation may be done by a provider with expertise in transgender medicine. The evaluation might include:

- A review of your personal and family medical history

- A physical exam

- A review of your vaccinations

- Screening tests for some conditions and diseases

- Identification and management, if needed, of tobacco use, drug use, alcohol use disorder, HIV or other sexually transmitted infections

- Discussion about birth control, fertility and sexual function

You also may have a behavioral health evaluation by a health care provider with expertise in transgender health. That evaluation might assess:

- Gender identity

- Gender dysphoria

- Mental health concerns

- Sexual health concerns

- The impact of gender identity at work, at school, at home and in social settings

- The role of social transitioning and hormone therapy before surgery

- Risky behaviors, such as substance use or use of unapproved hormone therapy or supplements

- Support from family, friends and caregivers

- Your goals and expectations of treatment

- Care planning and follow-up after surgery

Other considerations

Health insurance coverage for feminizing surgery varies widely. Before you have surgery, check with your insurance provider to see what will be covered.

Before surgery, you might consider talking to others who have had feminizing surgery. If you don't know someone, ask your health care provider about support groups in your area or online resources you can trust. People who have gone through the process may be able to help you set your expectations and offer a point of comparison for your own goals of the surgery.

What you can expect

Facial feminization surgery.

Facial feminization surgery may involve a range of procedures to change facial features, including:

- Moving the hairline to create a smaller forehead

- Enlarging the lips and cheekbones with implants

- Reshaping the jaw and chin

- Undergoing skin-tightening surgery after bone reduction

These surgeries are typically done on an outpatient basis, requiring no hospital stay. Recovery time for most of them is several weeks. Recovering from jaw procedures takes longer.

Tracheal shave

A tracheal shave minimizes the thyroid cartilage, also called the Adam's apple. During this procedure, a small cut is made under the chin, in the shadow of the neck or in a skin fold to conceal the scar. The surgeon then reduces and reshapes the cartilage. This is typically an outpatient procedure, requiring no hospital stay.

Top surgery

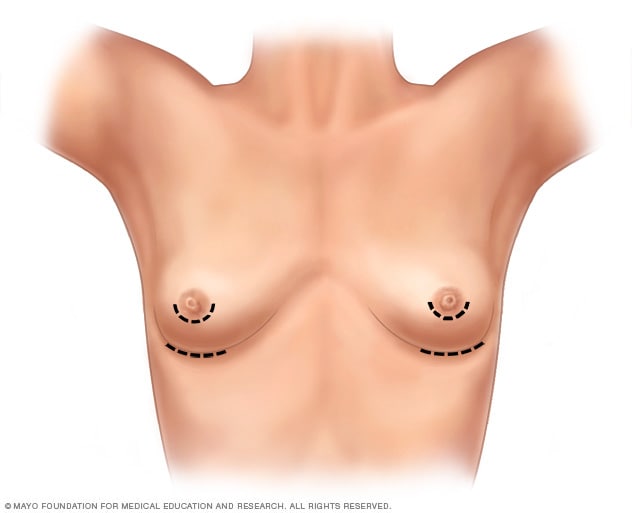

- Breast augmentation incisions

As part of top surgery, the surgeon makes cuts around the areola, near the armpit or in the crease under the breast.

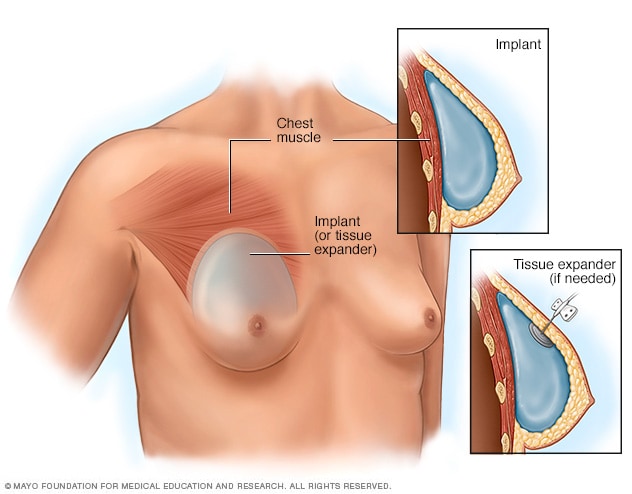

- Placement of breast implants or tissue expanders

During top surgery, the surgeon places the implants under the breast tissue. If feminizing hormones haven't made the breasts large enough, an initial surgery might be needed to have devices called tissue expanders placed in front of the chest muscles.

Hormone therapy with estrogen stimulates breast growth, but many people aren't satisfied with that growth alone. Top surgery is a surgical procedure to increase breast size that may involve implants, fat grafting or both.

During this surgery, a surgeon makes cuts around the areola, near the armpit or in the crease under the breast. Next, silicone or saline implants are placed under the breast tissue. Another option is to transplant fat, muscles or tissue from other parts of the body into the breasts.

If feminizing hormones haven't made the breasts large enough for top surgery, an initial surgery may be needed to place devices called tissue expanders in front of the chest muscles. After that surgery, visits to a health care provider are needed every few weeks to have a small amount of saline injected into the tissue expanders. This slowly stretches the chest skin and other tissues to make room for the implants. When the skin has been stretched enough, another surgery is done to remove the expanders and place the implants.

Genital surgery

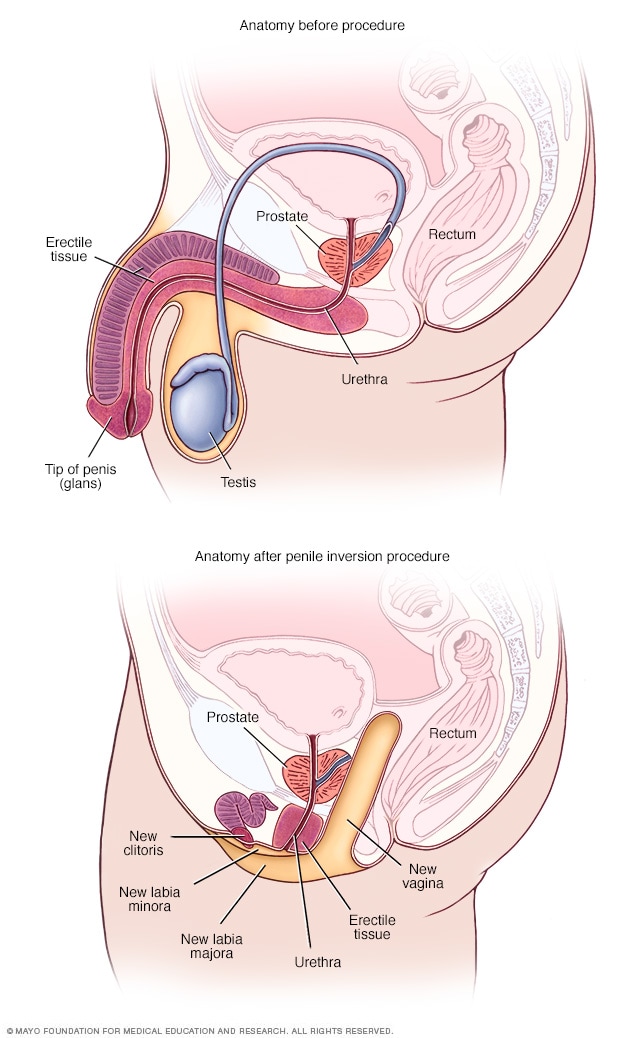

- Anatomy before and after penile inversion

During penile inversion, the surgeon makes a cut in the area between the rectum and the urethra and prostate. This forms a tunnel that becomes the new vagina. The surgeon lines the inside of the tunnel with skin from the scrotum, the penis or both. If there's not enough penile or scrotal skin, the surgeon might take skin from another area of the body and use it for the new vagina as well.

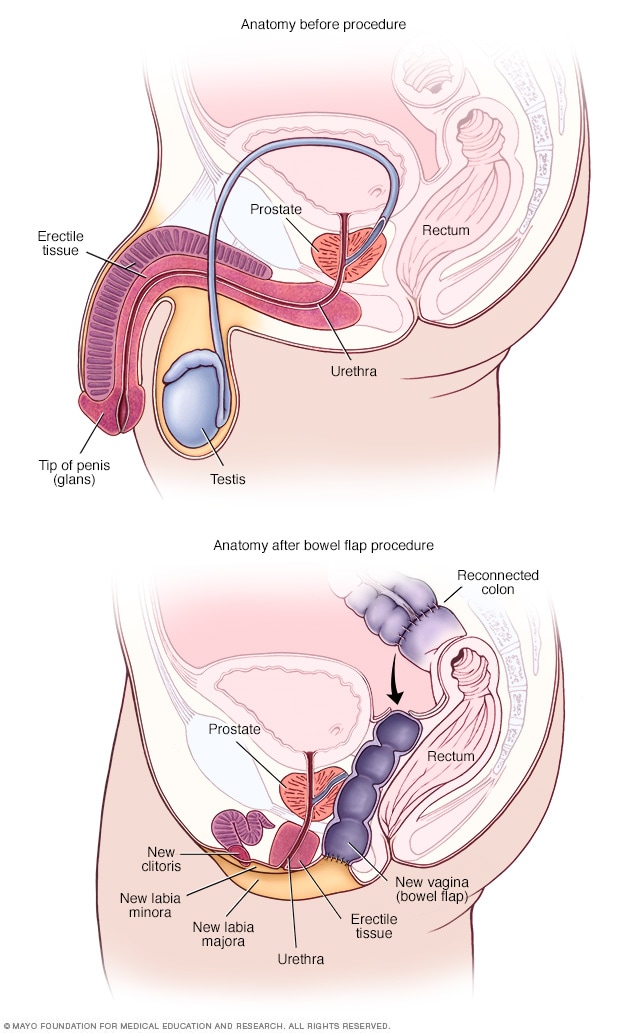

- Anatomy before and after bowel flap procedure

A bowel flap procedure might be done if there's not enough tissue or skin in the penis or scrotum. The surgeon moves a segment of the colon or small bowel to form a new vagina. That segment is called a bowel flap or conduit. The surgeon reconnects the remaining parts of the colon.

Orchiectomy

Orchiectomy is a surgery to remove the testicles. Because testicles produce sperm and the hormone testosterone, an orchiectomy might eliminate the need to use testosterone blockers. It also may lower the amount of estrogen needed to achieve and maintain the appearance you want.

This type of surgery is typically done on an outpatient basis. A local anesthetic may be used, so only the testicular area is numbed. Or the surgery may be done using general anesthesia. This means you are in a sleep-like state during the procedure.

To remove the testicles, a surgeon makes a cut in the scrotum and removes the testicles through the opening. Orchiectomy is typically done as part of the surgery for vaginoplasty. But some people prefer to have it done alone without other genital surgery.

Vaginoplasty

Vaginoplasty is the surgical creation of a vagina. During vaginoplasty, skin from the shaft of the penis and the scrotum is used to create a vaginal canal. This surgical approach is called penile inversion. In some techniques, the skin also is used to create the labia. That procedure is called labiaplasty. To surgically create a clitoris, the tip of the penis and the nerves that supply it are used. This procedure is called a clitoroplasty. In some cases, skin can be taken from another area of the body or tissue from the colon may be used to create the vagina. This approach is called a bowel flap procedure. During vaginoplasty, the testicles are removed if that has not been done previously.

Some surgeons use a technique that requires laser hair removal in the area of the penis and scrotum to provide hair-free tissue for the procedure. That process can take several months. Other techniques don't require hair removal prior to surgery because the hair follicles are destroyed during the procedure.

After vaginoplasty, a tube called a catheter is placed in the urethra to collect urine for several days. You need to be closely watched for about a week after surgery. Recovery can take up to two months. Your health care provider gives you instructions about when you may begin sexual activity with your new vagina.

After surgery, you're given a set of vaginal dilators of increasing sizes. You insert the dilators in your vagina to maintain, lengthen and stretch it. Follow your health care provider's directions on how often to use the dilators. To keep the vagina open, dilation needs to continue long term.

Because the prostate gland isn't removed during surgery, you need to follow age-appropriate recommendations for prostate cancer screening. Following surgery, it is possible to develop urinary symptoms from enlargement of the prostate.

Dilation after gender-affirming surgery

This material is for your education and information only. This content does not replace medical advice, diagnosis and treatment. If you have questions about a medical condition, always talk with your health care provider.

Narrator: Vaginal dilation is important to your recovery and ongoing care. You have to dilate to maintain the size and shape of your vaginal canal and to keep it open.

Jessi: I think for many trans women, including myself, but especially myself, I looked forward to one day having surgery for a long time. So that meant looking up on the internet what the routines would be, what the surgery entailed. So I knew going into it that dilation was going to be a very big part of my routine post-op, but just going forward, permanently.

Narrator: Vaginal dilation is part of your self-care. You will need to do vaginal dilation for the rest of your life.

Alissa (nurse): If you do not do dilation, your vagina may shrink or close. If that happens, these changes might not be able to be reversed.

Narrator: For the first year after surgery, you will dilate many times a day. After the first year, you may only need to dilate once a week. Most people dilate for the rest of their life.

Jessi: The dilation became easier mostly because I healed the scars, the stitches held up a little bit better, and I knew how to do it better. Each transgender woman's vagina is going to be a little bit different based on anatomy, and I grew to learn mine. I understand, you know, what position I needed to put the dilator in, how much force I needed to use, and once I learned how far I needed to put it in and I didn't force it and I didn't worry so much on oh, did I put it in too far, am I not putting it in far enough, and I have all these worries and then I stress out and then my body tenses up. Once I stopped having those thoughts, I relaxed more and it was a lot easier.

Narrator: You will have dilators of different sizes. Your health care provider will determine which sizes are best for you. Dilation will most likely be painful at first. It's important to dilate even if you have pain.

Alissa (nurse): Learning how to relax the muscles and breathe as you dilate will help. If you wish, you can take the pain medication recommended by your health care team before you dilate.

Narrator: Dilation requires time and privacy. Plan ahead so you have a private area at home or at work. Be sure to have your dilators, a mirror, water-based lubricant and towels available. Wash your hands and the dilators with warm soapy water, rinse well and dry on a clean towel. Use a water-based lubricant to moisten the rounded end of the dilators. Water-based lubricants are available over-the-counter. Do not use oil-based lubricants, such as petroleum jelly or baby oil. These can irritate the vagina. Find a comfortable position in bed or elsewhere. Use pillows to support your back and thighs as you lean back to a 45-degree angle. Start your dilation session with the smallest dilator. Hold a mirror in one hand. Use the other hand to find the opening of your vagina. Separate the skin. Relax through your hips, abdomen and pelvic floor. Take slow, deep breaths. Position the rounded end of the dilator with the lubricant at the opening to your vaginal canal. The rounded end should point toward your back. Insert the dilator. Go slowly and gently. Think of its path as a gentle curving swoop. The dilator doesn't go straight in. It follows the natural curve of the vaginal canal. Keep gentle down and inward pressure on the dilator as you insert it. Stop when the dilator's rounded end reaches the end of your vaginal canal. The dilators have dots or markers that measure depth. Hold the dilator in place in your vaginal canal. Use gentle but constant inward pressure for the correct amount of time at the right depth for you. If you're feeling pain, breathe and relax the muscles. When time is up, slowly remove the dilator, then repeat with the other dilators you need to use. Wash the dilators and your hands. If you have increased discharge following dilation, you may want to wear a pad to protect your clothing.

Jessi: I mean, it's such a strange, unfamiliar feeling to dilate and to have a dilator, you know to insert a dilator into your own vagina. Because it's not a pleasurable experience, and it's quite painful at first when you start to dilate. It feels much like a foreign body entering and it doesn't feel familiar and your body kind of wants to get it out of there. It's really tough at the beginning, but if you can get through the first month, couple months, it's going to be a lot easier and it's not going to be so much of an emotional and uncomfortable experience.

Narrator: You need to stay on schedule even when traveling. Bring your dilators with you. If your schedule at work creates challenges, ask your health care team if some of your dilation sessions can be done overnight.

Alissa (nurse): You can't skip days now and do more dilation later. You must do dilation on schedule to keep vaginal depth and width. It is important to dilate even if you have pain. Dilation should cause less pain over time.

Jessi: I hear that from a lot of other women that it's an overwhelming experience. There's lots of emotions that are coming through all at once. But at the end of the day for me, it was a very happy experience. I was glad to have the opportunity because that meant that while I have a vagina now, at the end of the day I had a vagina. Yes, it hurts, and it's not pleasant to dilate, but I have the vagina and it's worth it. It's a long process and it's not going to be easy. But you can do it.

Narrator: If you feel dilation may not be working or you have any questions about dilation, please talk with a member of your health care team.

Research has found that that gender-affirming surgery can have a positive impact on well-being and sexual function. It's important to follow your health care provider's advice for long-term care and follow-up after surgery. Continued care after surgery is associated with good outcomes for long-term health.

Before you have surgery, talk to members of your health care team about what to expect after surgery and the ongoing care you may need.

Clinical trials

Explore Mayo Clinic studies of tests and procedures to help prevent, detect, treat or manage conditions.

Feminizing surgery care at Mayo Clinic

- Tangpricha V, et al. Transgender women: Evaluation and management. https://www.uptodate.com/ contents/search. Accessed Aug. 16, 2022.

- Erickson-Schroth L, ed. Surgical transition. In: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd ed. Kindle edition. Oxford University Press; 2022. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Coleman E, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8. International Journal of Transgender Health. 2022; doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644.

- AskMayoExpert. Gender-affirming procedures (adult). Mayo Clinic; 2022.

- Nahabedian, M. Implant-based breast reconstruction and augmentation. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Erickson-Schroth L, ed. Medical transition. In: Trans Bodies, Trans Selves: A Resource by and for Transgender Communities. 2nd ed. Kindle edition. Oxford University Press; 2022. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Ferrando C, et al. Gender-affirming surgery: Male to female. https://www.uptodate.com/contents/search. Accessed Aug. 17, 2022.

- Doctors & Departments

- Care at Mayo Clinic

Mayo Clinic does not endorse companies or products. Advertising revenue supports our not-for-profit mission.

- Opportunities

Mayo Clinic Press

Check out these best-sellers and special offers on books and newsletters from Mayo Clinic Press .

- Mayo Clinic on Incontinence - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Incontinence

- The Essential Diabetes Book - Mayo Clinic Press The Essential Diabetes Book

- Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic on Hearing and Balance

- FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment - Mayo Clinic Press FREE Mayo Clinic Diet Assessment

- Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book - Mayo Clinic Press Mayo Clinic Health Letter - FREE book

Your gift holds great power – donate today!

Make your tax-deductible gift and be a part of the cutting-edge research and care that's changing medicine.

- Type 2 Diabetes

- Heart Disease

- Digestive Health

- Multiple Sclerosis

- COVID-19 Vaccines

- Occupational Therapy

- Healthy Aging

- Health Insurance

- Public Health

- Patient Rights

- Caregivers & Loved Ones

- End of Life Concerns

- Health News

- Thyroid Test Analyzer

- Doctor Discussion Guides

- Hemoglobin A1c Test Analyzer

- Lipid Test Analyzer

- Complete Blood Count (CBC) Analyzer

- What to Buy

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Medical Expert Board

Gender Confirmation Surgery (GCS)

What is Gender Confirmation Surgery?

- Transfeminine Tr

Transmasculine Transition

- Traveling Abroad

Choosing a Surgeon

Gender confirmation surgery (GCS), known clinically as genitoplasty, are procedures that surgically confirm a person's gender by altering the genitalia and other physical features to align with their desired physical characteristics. Gender confirmation surgeries are also called gender affirmation procedures. These are both respectful terms.

Gender dysphoria , an experience of misalignment between gender and sex, is becoming more widely diagnosed. People diagnosed with gender dysphoria are often referred to as "transgender," though one does not necessarily need to experience gender dysphoria to be a member of the transgender community. It is important to note there is controversy around the gender dysphoria diagnosis. Many disapprove of it, noting that the diagnosis suggests that being transgender is an illness.

Ellen Lindner / Verywell

Transfeminine Transition

Transfeminine is a term inclusive of trans women and non-binary trans people assigned male at birth.

Gender confirmation procedures that a transfeminine person may undergo include:

- Penectomy is the surgical removal of external male genitalia.

- Orchiectomy is the surgical removal of the testes.

- Vaginoplasty is the surgical creation of a vagina.

- Feminizing genitoplasty creates internal female genitalia.

- Breast implants create breasts.

- Gluteoplasty increases buttock volume.

- Chondrolaryngoplasty is a procedure on the throat that can minimize the appearance of Adam's apple .

Feminizing hormones are commonly used for at least 12 months prior to breast augmentation to maximize breast growth and achieve a better surgical outcome. They are also often used for approximately 12 months prior to feminizing genital surgeries.

Facial feminization surgery (FFS) is often done to soften the lines of the face. FFS can include softening the brow line, rhinoplasty (nose job), smoothing the jaw and forehead, and altering the cheekbones. Each person is unique and the procedures that are done are based on the individual's need and budget,

Transmasculine is a term inclusive of trans men and non-binary trans people assigned female at birth.

Gender confirmation procedures that a transmasculine person may undergo include:

- Masculinizing genitoplasty is the surgical creation of external genitalia. This procedure uses the tissue of the labia to create a penis.

- Phalloplasty is the surgical construction of a penis using a skin graft from the forearm, thigh, or upper back.

- Metoidioplasty is the creation of a penis from the hormonally enlarged clitoris.

- Scrotoplasty is the creation of a scrotum.

Procedures that change the genitalia are performed with other procedures, which may be extensive.

The change to a masculine appearance may also include hormone therapy with testosterone, a mastectomy (surgical removal of the breasts), hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus), and perhaps additional cosmetic procedures intended to masculinize the appearance.

Paying For Gender Confirmation Surgery

Medicare and some health insurance providers in the United States may cover a portion of the cost of gender confirmation surgery.

It is unlawful to discriminate or withhold healthcare based on sex or gender. However, many plans do have exclusions.

For most transgender individuals, the burden of financing the procedure(s) is the main difficulty in obtaining treatment. The cost of transitioning can often exceed $100,000 in the United States, depending upon the procedures needed.

A typical genitoplasty alone averages about $18,000. Rhinoplasty, or a nose job, averaged $5,409 in 2019.

Traveling Abroad for GCS

Some patients seek gender confirmation surgery overseas, as the procedures can be less expensive in some other countries. It is important to remember that traveling to a foreign country for surgery, also known as surgery tourism, can be very risky.

Regardless of where the surgery will be performed, it is essential that your surgeon is skilled in the procedure being performed and that your surgery will be performed in a reputable facility that offers high-quality care.

When choosing a surgeon , it is important to do your research, whether the surgery is performed in the U.S. or elsewhere. Talk to people who have already had the procedure and ask about their experience and their surgeon.

Before and after photos don't tell the whole story, and can easily be altered, so consider asking for a patient reference with whom you can speak.

It is important to remember that surgeons have specialties and to stick with your surgeon's specialty. For example, you may choose to have one surgeon perform a genitoplasty, but another to perform facial surgeries. This may result in more expenses, but it can result in a better outcome.

A Word From Verywell

Gender confirmation surgery is very complex, and the procedures that one person needs to achieve their desired result can be very different from what another person wants.

Each individual's goals for their appearance will be different. For example, one individual may feel strongly that breast implants are essential to having a desirable and feminine appearance, while a different person may not feel that breast size is a concern. A personalized approach is essential to satisfaction because personal appearance is so highly individualized.

Davy Z, Toze M. What is gender dysphoria? A critical systematic narrative review . Transgend Health . 2018;3(1):159-169. doi:10.1089/trgh.2018.0014

Morrison SD, Vyas KS, Motakef S, et al. Facial Feminization: Systematic Review of the Literature . Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(6):1759-70. doi:10.1097/PRS.0000000000002171

Hadj-moussa M, Agarwal S, Ohl DA, Kuzon WM. Masculinizing Genital Gender Confirmation Surgery . Sex Med Rev . 2019;7(1):141-155. doi:10.1016/j.sxmr.2018.06.004

Dowshen NL, Christensen J, Gruschow SM. Health Insurance Coverage of Recommended Gender-Affirming Health Care Services for Transgender Youth: Shopping Online for Coverage Information . Transgend Health . 2019;4(1):131-135. doi:10.1089/trgh.2018.0055

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Rhinoplasty nose surgery .

Rights Group: More U.S. Companies Covering Cost of Gender Reassignment Surgery. CNS News. http://cnsnews.com/news/article/rights-group-more-us-companies-covering-cost-gender-reassignment-surgery

The Sex Change Capital of the US. CBS News. http://www.cbsnews.com/2100-3445_162-4423154.html

By Jennifer Whitlock, RN, MSN, FN Jennifer Whitlock, RN, MSN, FNP-C, is a board-certified family nurse practitioner. She has experience in primary care and hospital medicine.

- Search the site GO Please fill out this field.

- Newsletters

- Mental Health

- Social and Public Health

What Is Gender Affirmation Surgery?

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/KP-Headshot-IMG_1661-0d48c6ea46f14ab19a91e7b121b49f59.jpg)

A gender affirmation surgery allows individuals, such as those who identify as transgender or nonbinary, to change one or more of their sex characteristics. This type of procedure offers a person the opportunity to have features that align with their gender identity.

For example, this type of surgery may be a transgender surgery like a male-to-female or female-to-male surgery. Read on to learn more about what masculinizing, feminizing, and gender-nullification surgeries may involve, including potential risks and complications.

Why Is Gender Affirmation Surgery Performed?

A person may have gender affirmation surgery for different reasons. They may choose to have the surgery so their physical features and functional ability align more closely with their gender identity.

For example, one study found that 48,019 people underwent gender affirmation surgeries between 2016 and 2020. Most procedures were breast- and chest-related, while the remaining procedures concerned genital reconstruction or facial and cosmetic procedures.

In some cases, surgery may be medically necessary to treat dysphoria. Dysphoria refers to the distress that transgender people may experience when their gender identity doesn't match their sex assigned at birth. One study found that people with gender dysphoria who had gender affirmation surgeries experienced:

- Decreased antidepressant use

- Decreased anxiety, depression, and suicidal ideation

- Decreased alcohol and drug abuse

However, these surgeries are only performed if appropriate for a person's case. The appropriateness comes about as a result of consultations with mental health professionals and healthcare providers.

Transgender vs Nonbinary

Transgender and nonbinary people can get gender affirmation surgeries. However, there are some key ways that these gender identities differ.

Transgender is a term that refers to people who have gender identities that aren't the same as their assigned sex at birth. Identifying as nonbinary means that a person doesn't identify only as a man or a woman. A nonbinary individual may consider themselves to be:

- Both a man and a woman

- Neither a man nor a woman

- An identity between or beyond a man or a woman

Hormone Therapy

Gender-affirming hormone therapy uses sex hormones and hormone blockers to help align the person's physical appearance with their gender identity. For example, some people may take masculinizing hormones.

"They start growing hair, their voice deepens, they get more muscle mass," Heidi Wittenberg, MD , medical director of the Gender Institute at Saint Francis Memorial Hospital in San Francisco and director of MoZaic Care Inc., which specializes in gender-related genital, urinary, and pelvic surgeries, told Health .

Types of hormone therapy include:

- Masculinizing hormone therapy uses testosterone. This helps to suppress the menstrual cycle, grow facial and body hair, increase muscle mass, and promote other male secondary sex characteristics.

- Feminizing hormone therapy includes estrogens and testosterone blockers. These medications promote breast growth, slow the growth of body and facial hair, increase body fat, shrink the testicles, and decrease erectile function.

- Non-binary hormone therapy is typically tailored to the individual and may include female or male sex hormones and/or hormone blockers.

It can include oral or topical medications, injections, a patch you wear on your skin, or a drug implant. The therapy is also typically recommended before gender affirmation surgery unless hormone therapy is medically contraindicated or not desired by the individual.

Masculinizing Surgeries

Masculinizing surgeries can include top surgery, bottom surgery, or both. Common trans male surgeries include:

- Chest masculinization (breast tissue removal and areola and nipple repositioning/reshaping)

- Hysterectomy (uterus removal)

- Metoidioplasty (lengthening the clitoris and possibly extending the urethra)

- Oophorectomy (ovary removal)

- Phalloplasty (surgery to create a penis)

- Scrotoplasty (surgery to create a scrotum)

Top Surgery

Chest masculinization surgery, or top surgery, often involves removing breast tissue and reshaping the areola and nipple. There are two main types of chest masculinization surgeries:

- Double-incision approach : Used to remove moderate to large amounts of breast tissue, this surgery involves two horizontal incisions below the breast to remove breast tissue and accentuate the contours of pectoral muscles. The nipples and areolas are removed and, in many cases, resized, reshaped, and replaced.

- Short scar top surgery : For people with smaller breasts and firm skin, the procedure involves a small incision along the lower half of the areola to remove breast tissue. The nipple and areola may be resized before closing the incision.

Metoidioplasty

Some trans men elect to do metoidioplasty, also called a meta, which involves lengthening the clitoris to create a small penis. Both a penis and a clitoris are made of the same type of tissue and experience similar sensations.

Before metoidioplasty, testosterone therapy may be used to enlarge the clitoris. The procedure can be completed in one surgery, which may also include:

- Constructing a glans (head) to look more like a penis

- Extending the urethra (the tube urine passes through), which allows the person to urinate while standing

- Creating a scrotum (scrotoplasty) from labia majora tissue

Phalloplasty

Other trans men opt for phalloplasty to give them a phallic structure (penis) with sensation. Phalloplasty typically requires several procedures but results in a larger penis than metoidioplasty.

The first and most challenging step is to harvest tissue from another part of the body, often the forearm or back, along with an artery and vein or two, to create the phallus, Nicholas Kim, MD, assistant professor in the division of plastic and reconstructive surgery in the department of surgery at the University of Minnesota Medical School in Minneapolis, told Health .

Those structures are reconnected under an operative microscope using very fine sutures—"thinner than our hair," said Dr. Kim. That surgery alone can take six to eight hours, he added.

In a separate operation, called urethral reconstruction, the surgeons connect the urinary system to the new structure so that urine can pass through it, said Dr. Kim. Urethral reconstruction, however, has a high rate of complications, which include fistulas or strictures.

According to Dr. Kim, some trans men prefer to skip that step, especially if standing to urinate is not a priority. People who want to have penetrative sex will also need prosthesis implant surgery.

Hysterectomy and Oophorectomy

Masculinizing surgery often includes the removal of the uterus (hysterectomy) and ovaries (oophorectomy). People may want a hysterectomy to address their dysphoria, said Dr. Wittenberg, and it may be necessary if their gender-affirming surgery involves removing the vagina.

Many also opt for an oophorectomy to remove the ovaries, almond-shaped organs on either side of the uterus that contain eggs and produce female sex hormones. In this case, oocytes (eggs) can be extracted and stored for a future surrogate pregnancy, if desired. However, this is a highly personal decision, and some trans men choose to keep their uterus to preserve fertility.

Feminizing Surgeries

Surgeries are often used to feminize facial features, enhance breast size and shape, reduce the size of an Adam’s apple , and reconstruct genitals. Feminizing surgeries can include:

- Breast augmentation

- Facial feminization surgery

- Penis removal (penectomy)

- Scrotum removal (scrotectomy)

- Testicle removal (orchiectomy)

- Tracheal shave (chondrolaryngoplasty) to reduce an Adam's apple

- Vaginoplasty

- Voice feminization

Breast Augmentation

Top surgery, also known as breast augmentation or breast mammoplasty, is often used to increase breast size for a more feminine appearance. The procedure can involve placing breast implants, tissue expanders, or fat from other parts of the body under the chest tissue.

Breast augmentation can significantly improve gender dysphoria. Studies show most people who undergo top surgery are happier, more satisfied with their chest, and would undergo the surgery again.

Most surgeons recommend 12 months of feminizing hormone therapy before breast augmentation. Since hormone therapy itself can lead to breast tissue development, transgender women may or may not decide to have surgical breast augmentation.

Facial Feminization and Adam's Apple Removal

Facial feminization surgery (FFS) is a series of plastic surgery procedures that reshape the forehead, hairline, eyebrows, nose, cheeks, and jawline. Nonsurgical treatments like cosmetic fillers, botox, fat grafting, and liposuction may also be used to create a more feminine appearance.

Some trans women opt for chondrolaryngoplasty, also known as a tracheal shave. The procedure reduces the size of the Adam's apple, an area of cartilage around the larynx (voice box) that tends to be larger in people assigned male at birth.

Vulvoplasty and Vaginoplasty

As for bottom surgery, there are various feminizing procedures from which to choose. Vulvoplasty (to create external genitalia without a vagina) or vaginoplasty (to create a vulva and vaginal canal) are two of the most common procedures.

Dr. Wittenberg noted that people might undergo six to 12 months of electrolysis or laser hair removal before surgery to remove pubic hair from the skin that will be used for the vaginal lining.

Surgeons have different techniques for creating a vaginal canal. A common one is a penile inversion, where the masculine structures are emptied and inverted into a created cavity, explained Dr. Kim. Vaginoplasty may be done in one or two stages, said Dr. Wittenberg, and the initial recovery is three months—but it will be a full year until people see results.

Surgical removal of the penis or penectomy is sometimes used in feminization treatment. This can be performed along with an orchiectomy and scrotectomy.

However, a total penectomy is not commonly used in feminizing surgeries . Instead, many people opt for penile-inversion surgery, a technique that hollows out the penis and repurposes the tissue to create a vagina during vaginoplasty.

Orchiectomy and Scrotectomy

An orchiectomy is a surgery to remove the testicles —male reproductive organs that produce sperm. Scrotectomy is surgery to remove the scrotum, that sac just below the penis that holds the testicles.

However, some people opt to retain the scrotum. Scrotum skin can be used in vulvoplasty or vaginoplasty, surgeries to construct a vulva or vagina.

Other Surgical Options

Some gender non-conforming people opt for other types of surgeries. This can include:

- Gender nullification procedures

- Penile preservation vaginoplasty

- Vaginal preservation phalloplasty

Gender Nullification

People who are agender or asexual may opt for gender nullification, sometimes called nullo. This involves the removal of all sex organs. The external genitalia is removed, leaving an opening for urine to pass and creating a smooth transition from the abdomen to the groin.

Depending on the person's sex assigned at birth, nullification surgeries can include:

- Breast tissue removal

- Nipple and areola augmentation or removal

Penile Preservation Vaginoplasty

Some gender non-conforming people assigned male at birth want a vagina but also want to preserve their penis, said Dr. Wittenberg. Often, that involves taking skin from the lining of the abdomen to create a vagina with full depth.

Vaginal Preservation Phalloplasty

Alternatively, a patient assigned female at birth can undergo phalloplasty (surgery to create a penis) and retain the vaginal opening. Known as vaginal preservation phalloplasty, it is often used as a way to resolve gender dysphoria while retaining fertility.

The recovery time for a gender affirmation surgery will depend on the type of surgery performed. For example, healing for facial surgeries may last for weeks, while transmasculine bottom surgery healing may take months.

Your recovery process may also include additional treatments or therapies. Mental health support and pelvic floor physiotherapy are a few options that may be needed or desired during recovery.

Risks and Complications

The risk and complications of gender affirmation surgeries will vary depending on which surgeries you have. Common risks across procedures could include:

- Anesthesia risks

- Hematoma, which is bad bruising

- Poor incision healing

Complications from these procedures may be:

- Acute kidney injury

- Blood transfusion

- Deep vein thrombosis, which is blood clot formation

- Pulmonary embolism, blood vessel blockage for vessels going to the lung

- Rectovaginal fistula, which is a connection between two body parts—in this case, the rectum and vagina

- Surgical site infection

- Urethral stricture or stenosis, which is when the urethra narrows

- Urinary tract infection (UTI)

- Wound disruption

What To Consider

It's important to note that an individual does not need surgery to transition. If the person has surgery, it is usually only one part of the transition process.

There's also psychotherapy . People may find it helpful to work through the negative mental health effects of dysphoria. Typically, people seeking gender affirmation surgery must be evaluated by a qualified mental health professional to obtain a referral.

Some people may find that living in their preferred gender is all that's needed to ease their dysphoria. Doing so for one full year prior is a prerequisite for many surgeries.

All in all, the entire transition process—living as your identified gender, obtaining mental health referrals, getting insurance approvals, taking hormones, going through hair removal, and having various surgeries—can take years, healthcare providers explained.

A Quick Review

Whether you're in the process of transitioning or supporting someone who is, it's important to be informed about gender affirmation surgeries. Gender affirmation procedures often involve multiple surgeries, which can be masculinizing, feminizing, or gender-nullifying in nature.

It is a highly personalized process that looks different for each person and can often take several months or years. The procedures also vary regarding risks and complications, so consultations with healthcare providers and mental health professionals are essential before having these procedures.

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. Gender affirmation surgeries .

Wright JD, Chen L, Suzuki Y, Matsuo K, Hershman DL. National estimates of gender-affirming surgery in the US . JAMA Netw Open . 2023;6(8):e2330348-e2330348. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.30348

Coleman E, Radix AE, Bouman WP, et al. Standards of care for the health of transgender and gender diverse people, version 8 . Int J Transgend Health . 2022;23(S1):S1-S260. doi:10.1080/26895269.2022.2100644

Chou J, Kilmer LH, Campbell CA, DeGeorge BR, Stranix JY. Gender-affirming surgery improves mental health outcomes and decreases anti-depressant use in patients with gender dysphoria . Plast Reconstr Surg Glob Open . 2023;11(6 Suppl):1. doi:10.1097/01.GOX.0000944280.62632.8c

Human Rights Campaign. Get the facts on gender-affirming care .

Human Rights Campaign. Transgender and non-binary people FAQ .

Unger CA. Hormone therapy for transgender patients . Transl Androl Urol . 2016;5(6):877–84. doi:10.21037/tau.2016.09.04

Richards JE, Hawley RS. Chapter 8: Sex Determination: How Genes Determine a Developmental Choice . In: Richards JE, Hawley RS, eds. The Human Genome . 3rd ed. Academic Press; 2011: 273-298.

Randolph JF Jr. Gender-affirming hormone therapy for transgender females . Clin Obstet Gynecol . 2018;61(4):705-721. doi:10.1097/GRF.0000000000000396

Cocchetti C, Ristori J, Romani A, Maggi M, Fisher AD. Hormonal treatment strategies tailored to non-binary transgender individuals . J Clin Med . 2020;9(6):1609. doi:10.3390/jcm9061609

Van Boerum MS, Salibian AA, Bluebond-Langner R, Agarwal C. Chest and facial surgery for the transgender patient . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):219-227. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.18

Djordjevic ML, Stojanovic B, Bizic M. Metoidioplasty: techniques and outcomes . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):248–53. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.12

Bordas N, Stojanovic B, Bizic M, Szanto A, Djordjevic ML. Metoidioplasty: surgical options and outcomes in 813 cases . Front Endocrinol . 2021;12:760284. doi:10.3389/fendo.2021.760284

Al-Tamimi M, Pigot GL, van der Sluis WB, et al. The surgical techniques and outcomes of secondary phalloplasty after metoidioplasty in transgender men: an international, multi-center case series . The Journal of Sexual Medicine . 2019;16(11):1849-1859. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2019.07.027

Waterschoot M, Hoebeke P, Verla W, et al. Urethral complications after metoidioplasty for genital gender affirming surgery . J Sex Med . 2021;18(7):1271–9. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2020.06.023

Nikolavsky D, Hughes M, Zhao LC. Urologic complications after phalloplasty or metoidioplasty . Clin Plast Surg . 2018;45(3):425–35. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.013

Nota NM, den Heijer M, Gooren LJ. Evaluation and treatment of gender-dysphoric/gender incongruent adults . In: Feingold KR, Anawalt B, Boyce A, et al., eds. Endotext . MDText.com, Inc.; 2000.

Carbonnel M, Karpel L, Cordier B, Pirtea P, Ayoubi JM. The uterus in transgender men . Fertil Steril . 2021;116(4):931–5. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2021.07.005

Miller TJ, Wilson SC, Massie JP, Morrison SD, Satterwhite T. Breast augmentation in male-to-female transgender patients: Technical considerations and outcomes . JPRAS Open . 2019;21:63-74. doi:10.1016/j.jpra.2019.03.003

Claes KEY, D'Arpa S, Monstrey SJ. Chest surgery for transgender and gender nonconforming individuals . Clin Plast Surg . 2018;45(3):369–80. doi:10.1016/j.cps.2018.03.010

De Boulle K, Furuyama N, Heydenrych I, et al. Considerations for the use of minimally invasive aesthetic procedures for facial remodeling in transgender individuals . Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol . 2021;14:513-525. doi:10.2147/CCID.S304032

Asokan A, Sudheendran MK. Gender affirming body contouring and physical transformation in transgender individuals . Indian J Plast Surg . 2022;55(2):179-187. doi:10.1055/s-0042-1749099

Sturm A, Chaiet SR. Chondrolaryngoplasty-thyroid cartilage reduction . Facial Plast Surg Clin North Am . 2019;27(2):267–72. doi:10.1016/j.fsc.2019.01.005

Chen ML, Reyblat P, Poh MM, Chi AC. Overview of surgical techniques in gender-affirming genital surgery . Transl Androl Urol . 2019;8(3):191-208. doi:10.21037/tau.2019.06.19

Wangjiraniran B, Selvaggi G, Chokrungvaranont P, Jindarak S, Khobunsongserm S, Tiewtranon P. Male-to-female vaginoplasty: Preecha's surgical technique . J Plast Surg Hand Surg . 2015;49(3):153-9. doi:10.3109/2000656X.2014.967253

Okoye E, Saikali SW. Orchiectomy . In: StatPearls [Internet] . Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

Salgado CJ, Yu K, Lalama MJ. Vaginal and reproductive organ preservation in trans men undergoing gender-affirming phalloplasty: technical considerations . J Surg Case Rep . 2021;2021(12):rjab553. doi:10.1093/jscr/rjab553

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What should I expect during my recovery after facial feminization surgery?

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What should I expect during my recovery after transmasculine bottom surgery?

de Brouwer IJ, Elaut E, Becker-Hebly I, et al. Aftercare needs following gender-affirming surgeries: findings from the ENIGI multicenter European follow-up study . The Journal of Sexual Medicine . 2021;18(11):1921-1932. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2021.08.005

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What are the risks of transfeminine bottom surgery?

American Society of Plastic Surgeons. What are the risks of transmasculine top surgery?

Khusid E, Sturgis MR, Dorafshar AH, et al. Association between mental health conditions and postoperative complications after gender-affirming surgery . JAMA Surg . 2022;157(12):1159-1162. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2022.3917

Related Articles

- Reference Manager

- Simple TEXT file

People also looked at

Original research article, male-to-female gender-affirming surgery: 20-year review of technique and surgical results.

- 1 Serviço de Urologia, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil

- 2 Serviço de Psiquiatria, Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil

- 3 Serviço de Psiquiatria, Pontifical Catholic University of Rio Grande do Sul, Porto Alegre, Brazil

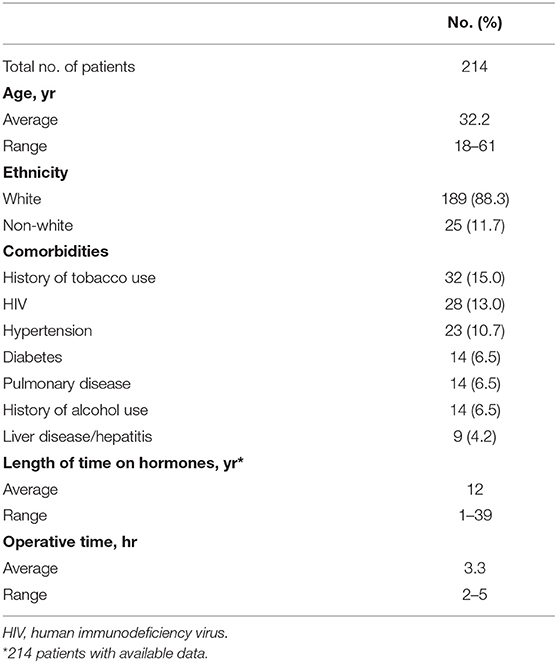

Purpose: Gender dysphoria (GD) is an incompatibility between biological sex and personal gender identity; individuals harbor an unalterable conviction that they were born in the wrong body, which causes personal suffering. In this context, surgery is imperative to achieve a successful gender transition and plays a key role in alleviating the associated psychological discomfort. In the current study, a retrospective cohort, we report the 20-years outcomes of the gender-affirming surgery performed at a single Brazilian university center, examining demographic data, intra and postoperative complications. During this period, 214 patients underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty.

Results: Results demonstrate that the average age at the time of surgery was 32.2 years (range, 18–61 years); the average of operative time was 3.3 h (range 2–5 h); the average duration of hormone therapy before surgery was 12 years (range 1–39). The most commons minor postoperative complications were granulation tissue (20.5 percent) and introital stricture of the neovagina (15.4 percent) and the major complications included urethral meatus stenosis (20.5 percent) and hematoma/excessive bleeding (8.9 percent). A total of 36 patients (16.8 percent) underwent some form of reoperation. One hundred eighty-one (85 percent) patients in our series were able to have regular sexual intercourse, and no individual regretted having undergone GAS.

Conclusions: Findings confirm that it is a safety procedure, with a low incidence of serious complications. Otherwise, in our series, there were a high level of functionality of the neovagina, as well as subjective personal satisfaction.

Introduction

Transsexualism (ICD-10) or Gender Dysphoria (GD) (DSM-5) is characterized by intense and persistent cross-gender identification which influences several aspects of behavior ( 1 ). The terms describe a situation where an individual's gender identity differs from external sexual anatomy at birth ( 1 ). Gender identity-affirming care, for those who desire, can include hormone therapy and affirming surgeries, as well as other procedures such as hair removal or speech therapy ( 1 ).

Since 1998, the Gender Identity Program (PROTIG) of the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre (HCPA), Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil has provided public assistance to transsexual people, is the first one in Brazil and one of the pioneers in South America. Our program offers psychosocial support, health care, and guidance to families, and refers individuals for gender-affirming surgery (GAS) when indicated. To be eligible for this surgery, transsexual individuals must have been adherent to multidisciplinary follow-up for at least 2 years, have a minimum age of 21 years (required for surgical procedures of this nature), have a positive psychiatric or psychological report, and have a diagnosis of GD.

Gender-affirming surgery (GAS) is increasingly recognized as a therapeutic intervention and a medical necessity, with growing societal acceptance ( 2 ). At our institution, we perform the classic penile inversion vaginoplasty (PIV), with an inverted penis skin flap used as the lining for the neovagina. Studies have demonstrated that GAS for the management of GD can promote improvements in mental health and social relationships for these patients ( 2 – 5 ). It is therefore imperative to understand and establish best practice techniques for this patient population ( 2 ). Although there are several studies reporting the safety and efficacy of gender-affirming surgery by penile inversion vaginoplasty, we present the largest South-American cohort to date, examining demographic data, intra and postoperative complications.

Patients and Methods

Subjects and study setup.

This is a retrospective cohort study of Brazilian transgender women who underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty between January of 2000 and March of 2020 at the Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre, Porto Alegre, Brazil. The study was approved by our institutional medical and research ethics committee.

At our institution, gender-affirming surgery is indicated for transgender women who are under assistance by our program for transsexual individuals. All transsexual women included in this study had at least 2 years of experience as a woman and met WPATH standards for GAS ( 1 ). Patients were submitted to biweekly group meetings and monthly individual therapy.

Between January of 2000 and March of 2020, a total of 214 patients underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty. The surgical procedures were performed by two separate staff members, mostly assisted by residents. A retrospective chart review was conducted recording patient demographics, intraoperative and postoperative complications, reoperations, and secondary surgical procedures. Informed consent was obtained from all individual participants included in the study.

Hormonal Therapy

The goal of feminizing hormone therapy is the development of female secondary sex characteristics, and suppression/minimization of male secondary sex characteristics.

Our general therapy approach is to combine an estrogen with an androgen blocker. The usual estrogen is the oral preparation of estradiol (17-beta estradiol), starting at a dose of 2 mg/day until the maximum dosage of 8 mg/day. The preferred androgen blocker is spironolactone at a dose of 200 mg twice a day.

Operative Technique

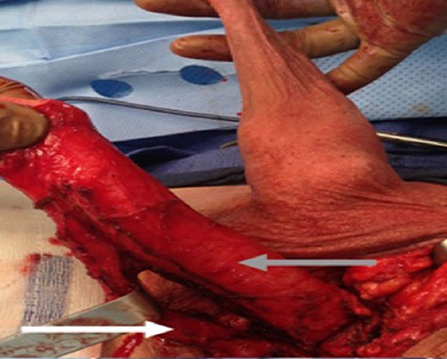

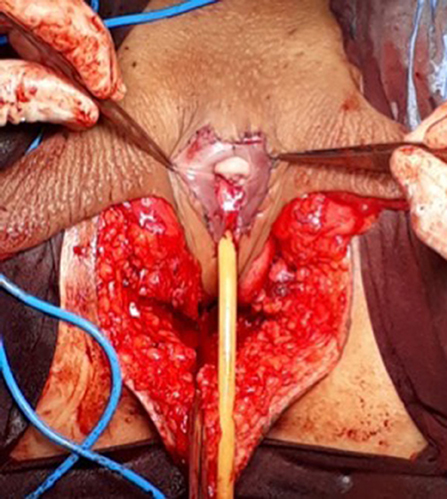

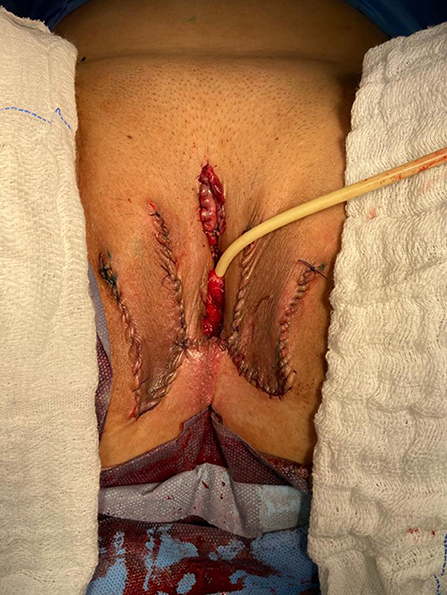

At our institution, we perform the classic penile inversion vaginoplasty, with an inverted penis skin flap used as the lining for the neovagina. For more details, we have previously published our technique with a step-by-step procedure video ( 6 ). All individuals underwent intestinal cleansing the evening before the surgery. A first-generation cephalosporin was used as preoperative prophylaxis. The procedure was performed with the patient in a dorsal lithotomy position. A Foley catheter was placed for bladder catheterization. A inverted-V incision was made 4 cm above the anus and a flap was created. A neovaginal cavity was created between the prostate and the rectum with blunt dissection, in the Denonvilliers space, until the peritoneal fold, usually measuring 12 cm in extension and 6 cm in width. The incision was then extended vertically to expose the testicles and the spermatic cords, which were removed at the level of the external inguinal rings. A circumferential subcoronal incision was made ( Figure 1 ), the penis was de-gloved and a skin flap was created, with the de-gloved penis being passed through the scrotal opening ( Figure 2 ). The dorsal part of the glans and its neurovascular bundle were bluntly dissected away from the penile shaft ( Figure 3 ) as well as the urethra, which included a portion of the bulbospongious muscle ( Figure 4 ). The corpora cavernosa was excised up to their attachments at the symphysis pubis and ligated. The neoclitoris was shaped and positioned in the midline at the level of the symphysis pubis and sutured using interrupted 5-0 absorbable suture. The corpus spongiosum was reduced and the urethra was shortened, spatulated, and placed 1 cm below the neoclitoris in the midline and sutured using interrupted 4-0 absorbable suture. The penile skin flap was inverted and pulled into the neovaginal cavity to become its walls ( Figure 5 ). The excess of skin was then removed, and the subcutaneous tissue and the skin were closed using continuous 3-0 non-absorbable suture ( Figure 6 ). A neo mons pubis was created using a 0 absorbable suture between the skin and the pubic bone. The skin flap was fixed to the pubic bone using a 0 absorbable suture. A gauze impregnated with Vaseline and antibiotic ointment was left inside the neovagina, and a customized compressive bandage was applied ( Figure 7 —shows the final appearance after the completion of the procedures).

Figure 1 . The initial circumferential subcoronal incision.

Figure 2 . The de-gloved penis being passed through the scrotal opening.

Figure 3 . The dorsal part of the glans and its neurovascular bundle dissected away from the penile shaft.

Figure 4 . The urethra dissected including a portion of the bulbospongious muscle. The grey arrow shows the penile shaft and the white arrow shows the dissected urethra.

Figure 5 . The inverted penile skin flap.

Figure 6 . The neoclitoris and the urethra sutured in the midline and the neovaginal cavity.

Figure 7 . The final appearance after the completion of the procedures.

Postoperative Care and Follow-Up

The patients were usually discharged within 2 days after surgery with the Foley catheter and vaginal gauze packing in place, which were removed after 7 days in an ambulatorial attendance.

Our vaginal dilation protocol starts seven days after surgery: a kit of 6 silicone dilators with progressive diameter (1.1–4 cm) and length (6.5–14.5 cm) is used; dilation is done progressively from the smallest dilator; each size should be kept in place for 5 min until the largest possible size, which is kept for 3 h during the day and during the night (sleep), if possible. The process is performed daily for the first 3 months and continued until the patient has regular sexual intercourse.

The follow-up visits were performed 7 days, 1, 2, 3, 6, and 12 months after surgery ( Figure 8 ), and included physical examination and a quality-of-life questionnaire.

Figure 8 . Appearance after 1 month of the procedure.

Statistical Analysis

The statistical analysis was conducted using Statistical Product and Service Solutions Version 18.0 (SPSS). Outcome measures were intra-operative and postoperative complications, re-operations. Descriptive statistics were used to evaluate the study outcomes. Mean values and standard deviations or median values and ranges are presented as continuous variables. Frequencies and percentages are reported for dichotomous and ordinal variables.

Patient Demographics

During the period of the study, 214 patients underwent penile inversion vaginoplasty, performed by two staff surgeons, mostly assisted by residents ( Table 1 ). The average age at the time of surgery was 32.2 years (range 18–61 years). There was no significant increase or decrease in the ages of patients who underwent SRS over the study period (Fisher's exact test: P = 0.065; chi-square test: X 2 = 5.15; GL = 6; P = 0.525). The average of operative time was 3.3 h (range 2–5 h). The average duration of hormone therapy before surgery was 12 years (range 1–39). The majority of patients were white (88.3 percent). The most prevalent patient comorbidities were history of tobacco use (15 percent), human immunodeficiency virus infection (13 percent) and hypertension (10.7 percent). Other comorbidities are listed in Table 1 .

Table 1 . Patient demographics.

Multidisciplinary follow-up was comprised of 93.45% of patients following up with a urologist and 59.06% of patients continuing psychiatric follow-up, median follow-up time of 16 and 9.3 months after surgery, respectively.

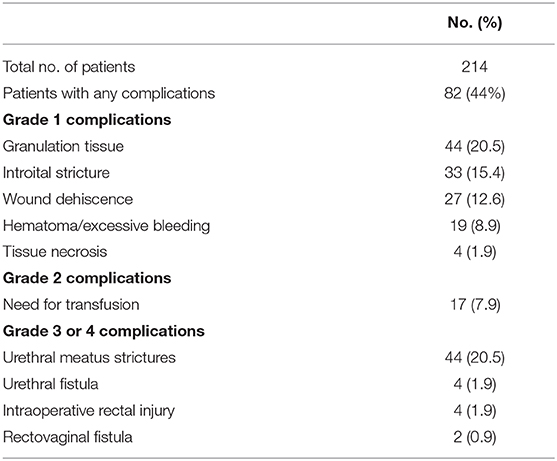

Postoperative Results

The complications were classified according to the Clavien-Dindo score ( Table 2 ). The most common minor postoperative complications (Grade I) were granulation tissue (20.5 percent), introital stricture of the neovagina (15.4 percent) and wound dehiscence (12.6 percent). The major complications (Grade III-IV) included urethral stenosis (20.5 percent), urethral fistula (1.9 percent), intraoperative rectal injury (1.9 percent), necrosis (primarily along the wound edges) (1.4 percent), and rectovaginal fistula (0.9 percent). A total of 17 patients required blood transfusion (7.9 percent).

Table 2 . Complications after penile inversion vaginoplasty.

A total of 36 patients (16.8 percent) underwent some form of reoperation.

One hundred eighty-one (85 percent) patients in our series were able to have regular sexual vaginal intercourse, and no individual regretted having undergone GAS.

Penile inversion vaginoplasty is the gold-standard in gender-affirming surgery. It has good functional outcomes, and studies have demonstrated adequate vaginal depths ( 3 ). It is recognized not only as a cosmetic procedure, but as a therapeutic intervention and a medical necessity ( 2 ). We present the largest South-American cohort to date, examining demographic data, intra and postoperative complications.

The mean age of transsexual women who underwent GAS in our study was 32.2 years (range 18–61 years), which is lower than the mean age of patients in studies found in the literature. Two studies indicated that the mean ages of patients at time of GAS were 36.7 years and 41 years, respectively ( 4 , 5 ). Another study reported a mean age at time of GAS of 36 years and found there was a significant decrease in age at the time of GAS from 41 years in 1994 to 35 years in 2015 ( 7 ). According to the authors, this decrease in age is associated with greater tolerance and societal approval regarding individuals with GD ( 7 ).

There was no grade IV or grade V complications. Excessive bleeding noticed postoperatively occurred in 19 patients (8.9 percent) and blood transfusion was required in 17 cases (7.9 percent); all patients who required blood transfusions were operated until July 2011, and the reason for this rate of blood transfusion was not identified.

The most common intraoperative complication was rectal injury, occurring in 4 patients (1.9 percent); in all patients the lesion was promptly identified and corrected in 2 layers absorbable sutures. In 2 of these patients, a rectovaginal fistula became evident, requiring fistulectomy and colonic transit deviation. This is consistent with current literature, in which rectal injury is reported in 0.4–4.5 percent of patients ( 4 , 5 , 8 – 13 ). Goddard et al. suggested carefully checking for enterotomy after prostate and bladder mobilization by digital rectal examination ( 4 ). Gaither et al. ( 14 ) commented that careful dissection that closely follows the urethra along its track from the central tendon of the perineum up through the lower pole of the prostate is critical and only blunt dissection is encouraged after Denonvilliers' fascia is reached. Alternatively, a robotic-assisted approach to penile inversion vaginoplasty may aid in minimizing these complications. The proposed advantages of a robotic-assisted vaginoplasty include safer dissection to minimize the risk of rectal injury and better proximal vaginal fixation. Dy et al. ( 15 ) has had no rectal injuries or fistulae to date in his series of 15 patients, with a mean follow-up of 12 months.

In our series, we observed 44 cases (20.5 percent) of urethral meatus strictures. We credit this complication to the technique used in the initial 5 years of our experience, in which the urethra was shortened and sutured in a circular fashion without spatulation. All cases were treated with meatal dilatation and 11 patients required surgical correction, being performed a Y-V plastic reconstruction of the urethral meatus. In the literature, meatal strictures are relatively rare in male-to-female (MtF) GAS due to the spatulation of the urethra and a simple anastomosis to the external genitalia. Recent systematic reviews show an incidence of five percent in this complication ( 16 , 17 ). Other studies report a wide incidence of meatal stenosis ranging from 1.1 to 39.8 percent ( 4 , 8 , 11 ).

Neovagina introital stricture was observed in 33 patients (15.4 percent) in our study and impedes the possibility of neovaginal penetration and/or adversely affects sexual life quality. In the literature, the reported incidence of introital stenosis range from 6.7 to 14.5 percent ( 4 , 5 , 8 , 9 , 11 – 13 ). According to Hadj-Moussa et al. ( 18 ) a regimen of postoperative prophylactic dilation is crucial to minimize the development of this outcome. At our institution, our protocol for vaginal dilation started seven days after surgery and was performed three to four times a day during the first 3 months and was continued until the individual had regular sexual intercourse. We treated stenosis initially with dilation. In case of no response, we propose a surgical revision with diamond-shaped introitoplasty with relaxing incisions. In recalcitrant cases, we proposed to the patient a secondary vaginoplasty using a full-thickness skin graft of the lower abdomen.

One hundred eighty-one (85 percent) patients were classified as having a “functional vagina,” characterized as the capacity to maintain satisfactory sexual vaginal intercourse, since the mean neovaginal depth was not measured. In a review article, the mean neovaginal depth ranged from 10 to 13.5 cm, with the shallowest neovagina depth at 2.5 cm and the deepest at 18 cm ( 17 ). According to Salim et al. ( 19 ), in terms of postoperative functional outcomes after penile inversion vaginoplasty, a mean percentage of 75 percent (range from 33 to 87 percent) patients were having vaginal intercourse. Hess et al. found that 91.4% of patients who responded to a questionnaire were very satisfied (34.4%), satisfied (37.6%), or mostly satisfied (19.4%) with their sexual function after penile inversion vaginoplasty ( 20 ).

Poor cosmetic appearance of the vulva is common. Amend et al. reported that the most common reason for reoperation was cosmetic correction in the form of mons pubis and mucosa reduction in 50% of patients ( 16 ). We had no patient regrets about performing GAS, although 36 patients (16.8 percent) were reoperated due to cosmetic issues. Gaither et al. propose in order to minimize scarring to use a one-stage surgical approach and the lateralization of surgical scars to the groin ( 14 ). Frequently, cosmetic issues outcomes are often patient driven and preoperative patient education is necessary ( 14 ).

Analyzing the quality of life, in 2016, our health care group (PROTIG) published a study assessing quality of life before and after gender-affirming surgery in 47 patients using the diagnostic tool 100-item WHO Quality of Life Assessment (WHOQOL-100) ( 21 ). The authors found that GAS promotes the improvement of psychological aspects and social relations. However, even 1 year after GAS, MtF persons continue to report problems in physical and difficulty in recovering their independence. In a systematic review and meta-analysis of QOL and psychosocial outcomes in transsexual people, researchers verified that sex reassignment with hormonal interventions more likely corrects gender dysphoria, psychological functioning and comorbidities, sexual function, and overall QOL compared with sex reassignment without hormonal interventions, although there is a low level of evidence for this ( 22 ). Recently, Castellano et al. assessed QOL in 60 Italian transsexuals (46 transwomen and 14 transmen) at least 2 years after SRS using the WHOQOL-100 (general QOL score and quality of sexual life and quality of body image scores) to focus on the effects of hormonal therapy. Overall satisfaction improved after SRS, and QOL was similar to the controls ( 23 ). Bartolucci et al. evaluated the perception of quality of sexual life using four questions evaluating the sexual facet in individuals with gender dysphoria before SRS and the possible factors associated with this perception. The study showed that approximately half the subjects with gender dysphoria perceived their sexual life as “poor/dissatisfied” or “very poor/very dissatisfied” before SRS ( 24 ).

Our study has some limitations. The total number of operated patients is restricted within the long follow-up period. This is due to a limitation in our health system, which allows only 1 sexual reassignment surgery to be performed per month at our institution. Neovagin depth measurement was not performed routinely in the follow-up of operated patients.

Conclusions

The definitive treatment for patients with gender dysphoria is gender-affirming surgery. Our series demonstrates that GAS is a feasible surgery with low rates of serious complications. We emphasize the high level of functionality of the vagina after the procedure, as well as subjective personal satisfaction. Complications, especially minor ones, are probably underestimated due to the nature of the study, and since this is a surgical population, the results may not be generalizable for all transgender MTF individuals.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre. The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

GM: conception and design, data acquisition, data analysis, interpretation, drafting the manuscript, review of the literature, critical revision of the manuscript and factual content, and statistical analysis. ML and TR: conception and design, data interpretation, drafting the manuscript, critical revision of the manuscript and factual content, and statistical analysis. DS, KS, AF, AC, PT, AG, and RC: conception and design, data acquisition and data analysis, interpretation, drafting the manuscript, and review of the literature. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This study was supported by the Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa e Eventos (FIPE - Fundo de Incentivo à Pesquisa e Eventos) of Hospital de Clínicas de Porto Alegre.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

1. Coleman E, Bockting W, Botzer M, Cohen-Kettenis P, DeCuypere G, Feldman J, et al. Standards of care for the health of transsexual, transgender, and gender-non-conforming people, version 7. Int J Transgend. (2012) 13:165–232. doi: 10.1080/15532739.2011.700873

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

2. Massie JP, Morrison SD, Maasdam JV, Satterwhite T. Predictors of patient satisfaction and postoperative complications in penile inversion vaginoplasty. Plast Reconstruct Surg. (2018) 141:911–921. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0000000000004427

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

3. Pan S, Honig SC. Gender-affirming surgery: current concepts. Curr Urol Rep . (2018) 19:62. doi: 10.1007/s11934-018-0809-9

4. Goddard JC, Vickery RM, Qureshi A, Summerton DJ, Khoosal D, Terry TR. Feminizing genitoplasty in adult transsexuals: early and long-term surgical results. BJU Int . (2007) 100:607–13. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2007.07017.x

5. Rossi NR, Hintz F, Krege S, Rübben H, Vom DF, Hess J. Gender reassignment surgery – a 13 year review of surgical outcomes. Eur Urol Suppl . (2013) 12:e559. doi: 10.1016/S1569-9056(13)61042-8

6. Silva RUM, Abreu FJS, Silva GMV, Santos JVQV, Batezini NSS, Silva Neto B, et al. Step by step male to female transsexual surgery. Int Braz J Urol. (2018) 44:407–8. doi: 10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2017.0044

7. Aydin D, Buk LJ, Partoft S, Bonde C, Thomsen MV, Tos T. Transgender surgery in Denmark from 1994 to 2015: 20-year follow-up study. J Sex Med. (2016) 13:720–5. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.01.012

8. Perovic SV, Stanojevic DS, Djordjevic MLJ. Vaginoplasty in male transsexuals using penile skin and a urethral flap. BJU Int. (2001) 86:843–50. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.2000.00934.x

9. Krege S, Bex A, Lümmen G, Rübben H. Male-to-female transsexualism: a technique, results and long-term follow-up in 66 patients. BJU Int. (2001) 88:396–402. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410X.2001.02323.x

10. Wagner S, Greco F, Hoda MR, Inferrera A, Lupo A, Hamza A, et al. Male-to-female transsexualism: technique, results and 3-year follow-up in 50 patients. Urol International. (2010) 84:330–3. doi: 10.1159/000288238

11. Reed H. Aesthetic and functional male to female genital and perineal surgery: feminizing vaginoplasty. Semin PlasticSurg. (2011) 25:163–74. doi: 10.1055/s-0031-1281486

12. Raigosa M, Avvedimento S, Yoon TS, Cruz-Gimeno J, Rodriguez G, Fontdevila J. Male-to-female genital reassignment surgery: a retrospective review of surgical technique and complications in 60 patients. J Sex Med. (2015) 12:1837–45. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12936

13. Sigurjonsson H, Rinder J, Möllermark C, Farnebo F, Lundgren TK. Male to female gender reassignment surgery: surgical outcomes of consecutive patients during 14 years. JPRAS Open. (2015) 6:69–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jpra.2015.09.003

14. Gaither TW, Awad MA, Osterberg EC, Murphy GP, Romero A, Bowers ML, et al. Postoperative complications following primary penile inversion vaginoplasty among 330 male-to-female transgender patients. J Urol. (2018) 199:760–5. doi: 10.1016/j.juro.2017.10.013

15. Dy GW, Sun J, Granieri MA, Zhao LC. Reconstructive management pearls for the transgender patient. Curr. Urol. Rep. (2018) 19:36. doi: 10.1007/s11934-018-0795-y

16. Amend B, Seibold J, Toomey P, Stenzl A, Sievert KD. Surgical reconstruction for male-to-female sex reassignment. Eur Urol. (2013) 64:141–9. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2012.12.030

17. Horbach SER, Bouman MB, Smit JM, Özer M, Buncamper ME, Mullender MG. Outcome of vaginoplasty in male-to-female transgenders: a systematic review of surgical techniques. J Sex Med . (2015) 12:1499–512. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12868

18. Hadj-Moussa M, Ohl DA, Kuzon WM. Feminizing genital gender-confirmation surgery. Sex Med Rev. (2018) 6:457–68.e2. doi: 10.1016/j.sxmr.2017.11.005

19. Salim A, Poh M. Gender-affirming penile inversion vaginoplasty. Clin Plast Surg. (2018) 45:343–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cps.2018.04.001

20. Hess J, Rossi NR, Panic L, Rubben H, Senf W. Satisfaction with male-to-female gender reassignment surgery. DtschArztebl Int. (2014) 111:795–801. doi: 10.3238/arztebl.2014.0795

21. Silva DC, Schwarz K, Fontanari AMV, Costa AB, Massuda R, Henriques AA, et al. WHOQOL-100 before and after sex reassignment surgery in brazilian male-to-female transsexual individuals. J Sex Med. (2016) 13:988–93. doi: 10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.03.370

22. Murad MH, Elamin MB, Garcia MZ, Mullan RJ, Murad A, Erwin PJ, et al. Hormonal therapy and sex reassignment: a systematic review and meta-analysis of quality of life and psychosocial outcomes. Clin Endocrinol . (2010) 72:214–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2265.2009.03625.x

23. Castellano E, Crespi C, Dell'Aquila C, Rosato R, Catalano C, Mineccia V, et al. Quality of life and hormones after sex reassignment surgery. J Endocrinol Invest . (2015) 38:1373–81. doi: 10.1007/s40618-015-0398-0

24. Bartolucci C, Gómez-Gil E, Salamero M, Esteva I, Guillamón A, Zubiaurre L, et al. Sexual quality of life in gender-dysphoric adults before genital sex reassignment surgery. J Sex Med . (2015) 12:180–8. doi: 10.1111/jsm.12758

Keywords: transsexualism, gender dysphoria, gender-affirming genital surgery, penile inversion vaginoplasty, surgical outcome

Citation: Moisés da Silva GV, Lobato MIR, Silva DC, Schwarz K, Fontanari AMV, Costa AB, Tavares PM, Gorgen ARH, Cabral RD and Rosito TE (2021) Male-to-Female Gender-Affirming Surgery: 20-Year Review of Technique and Surgical Results. Front. Surg. 8:639430. doi: 10.3389/fsurg.2021.639430

Received: 17 December 2020; Accepted: 22 March 2021; Published: 05 May 2021.

Reviewed by: