About . Click to expand section.

- Our History

- Team & Board

- Transparency and Accountability

What We Do . Click to expand section.

- Cycle of Poverty

- Climate & Environment

- Emergencies & Refugees

- Health & Nutrition

- Livelihoods

- Gender Equality

- Where We Work

Take Action . Click to expand section.

- Attend an Event

- Partner With Us

- Fundraise for Concern

- Work With Us

- Leadership Giving

- Humanitarian Training

- Newsletter Sign-Up

Donate . Click to expand section.

- Give Monthly

- Donate in Honor or Memory

- Leave a Legacy

- DAFs, IRAs, Trusts, & Stocks

- Employee Giving

How does education affect poverty?

For starters, it can help end it.

Aug 10, 2023

Access to high-quality primary education and supporting child well-being is a globally-recognized solution to the cycle of poverty. This is, in part, because it also addresses many of the other issues that keep communities vulnerable.

Education is often referred to as the great equalizer: It can open the door to jobs, resources, and skills that help a person not only survive, but thrive. In fact, according to UNESCO, if all students in low-income countries had just basic reading skills (nothing else), an estimated 171 million people could escape extreme poverty. If all adults completed secondary education, we could cut the global poverty rate by more than half.

At its core, a quality education supports a child’s developing social, emotional, cognitive, and communication skills. Children who attend school also gain knowledge and skills, often at a higher level than those who aren’t in the classroom. They can then use these skills to earn higher incomes and build successful lives.

Here’s more on seven of the key ways that education affects poverty.

Go to the head of the class

Get more information on Concern's education programs — and the other ways we're ending poverty — delivered to your inbox.

1. Education is linked to economic growth

Education is the best way out of poverty in part because it is strongly linked to economic growth. A 2021 study co-published by Stanford University and Munich’s Ludwig Maximilian University shows us that, between 1960 and 2000, 75% of the growth in gross domestic product around the world was linked to increased math and science skills.

“The relationship between…the knowledge capital of a nation, and the long-run [economic] rowth rate is extraordinarily strong,” the study’s authors conclude. This is just one of the most recent studies linking education and economic growth that have been published since 1990.

“The relationship between…the knowledge capital of a nation, and the long-run [economic] growth rate is extraordinarily strong.” — Education and Economic Growth (2021 study by Stanford University and the University of Munich)

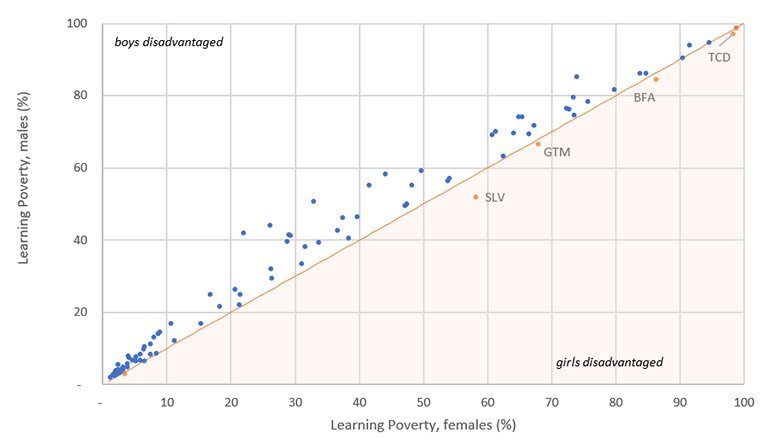

2. Universal education can fight inequality

A 2019 Oxfam report says it best: “Good-quality education can be liberating for individuals, and it can act as a leveler and equalizer within society.”

Poverty thrives in part on inequality. All types of systemic barriers (including physical ability, religion, race, and caste) serve as compound interest against a marginalization that already accrues most for those living in extreme poverty. Education is a basic human right for all, and — when tailored to the unique needs of marginalized communities — can be used as a lever against some of the systemic barriers that keep certain groups of people furthest behind.

For example, one of the biggest inequalities that fuels the cycle of poverty is gender. When gender inequality in the classroom is addressed, this has a ripple effect on the way women are treated in their communities. We saw this at work in Afghanistan , where Concern developed a Community-Based Education program that allowed students in rural areas to attend classes closer to home, which is especially helpful for girls.

Four ways that girls’ education can change the world

Gender discrimination is one of the many barriers to education around the world. That’s a situation we need to change.

3. Education is linked to lower maternal and infant mortality rates

Speaking of women, education also means healthier mothers and children. Examining 15 countries in sub-Saharan Africa, researchers from the World Bank and International Center for Research on Women found that educated women tend to have fewer children and have them later in life. This generally leads to better outcomes for both the mother and her kids, with safer pregnancies and healthier newborns.

A 2017 report shows that the country’s maternal mortality rate had declined by more than 70% in the last 25 years, approximately the same amount of time that an amendment to compulsory schooling laws took place in 1993. Ensuring that girls had more education reduced the likelihood of maternal health complications, in some cases by as much as 29%.

4. Education also lowers stunting rates

Children also benefit from more educated mothers. Several reports have linked education to lowered stunting , one of the side effects of malnutrition. Preventing stunting in childhood can limit the risks of many developmental issues for children whose height — and potential — are cut short by not having enough nutrients in their first few years.

In Bangladesh , one study showed a 50.7% prevalence for stunting among families. However, greater maternal education rates led to a 4.6% decrease in the odds of stunting; greater paternal education reduced those rates by 2.9%-5.4%. A similar study in Nairobi, Kenya confirmed this relationship: Children born to mothers with some secondary education are 29% less likely to be stunted.

What is stunting?

Stunting is a form of impaired growth and development due to malnutrition that threatens almost 25% of children around the world.

5. Education reduces vulnerability to HIV and AIDS…

In 2008, researchers from Harvard University, Imperial College London, and the World Bank wrote : “There is a growing body of evidence that keeping girls in school reduces their risk of contracting HIV. The relationship between educational attainment and HIV has changed over time, with educational attainment now more likely to be associated with a lower risk of HIV infection than earlier in the epidemic.”

Since then, that correlation has only grown stronger. The right programs in schools not only reduce the likelihood of young people contracting HIV or AIDS, but also reduce the stigmas held against people living with HIV and AIDS.

6. …and vulnerability to natural disasters and climate change

As the number of extreme weather events increases due to climate change, education plays a critical role in reducing vulnerability and risk to these events. A 2014 issue of the journal Ecology and Society states: “It is found that highly educated individuals are better aware of the earthquake risk … and are more likely to undertake disaster preparedness.… High risk awareness associated with education thus could contribute to vulnerability reduction behaviors.”

The authors of the article went on to add that educated people living through a natural disaster often have more of a financial safety net to offset losses, access to more sources of information to prepare for a disaster, and have a wider social network for mutual support.

Climate change is one of the biggest threats to education — and growing

Last August, UNICEF reported that half of the world’s 2.2 billion children are at “extremely high risk” for climate change, including its impact on education. Here’s why.

7. Education reduces violence at home and in communities

The same World Bank and ICRW report that showed the connection between education and maternal health also reveals that each additional year of secondary education reduced the chances of child marriage — defined as being married before the age of 18. Because educated women tend to marry later and have fewer children later in life, they’re also less likely to suffer gender-based violence , especially from their intimate partner.

Girls who receive a full education are also more likely to understand the harmful aspects of traditional practices like FGM , as well as their rights and how to stand up for them, at home and within their community.

Fighting FGM in Kenya: A daughter's bravery and a mother's love

Marsabit is one of those areas of northern Kenya where FGM has been the rule rather than the exception. But 12-year-old student Boti Ali had other plans.

Education for all: Concern’s approach

Concern’s work is grounded in the belief that all children have a right to a quality education. Last year, our work to promote education for all reached over 676,000 children. Over half of those students were female.

We integrate our education programs into both our development and emergency work to give children living in extreme poverty more opportunities in life and supporting their overall well-being. Concern has brought quality education to villages that are off the grid, engaged local community leaders to find solutions to keep girls in school, and provided mentorship and training for teachers.

More on how education affects poverty

6 Benefits of literacy in the fight against poverty

Child marriage and education: The blackboard wins over the bridal altar

Project Profile

Right to Learn

Sign up for our newsletter.

Get emails with stories from around the world.

You can change your preferences at any time. By subscribing, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

ESSAY SAUCE

FOR STUDENTS : ALL THE INGREDIENTS OF A GOOD ESSAY

Essay: Poverty in education

Essay details and download:.

- Subject area(s): Education essays

- Reading time: 5 minutes

- Price: Free download

- Published: 15 November 2018*

- File format: Text

- Words: 1,443 (approx)

- Number of pages: 6 (approx)

Text preview of this essay:

This page of the essay has 1,443 words. Download the full version above.

Poverty in Education

Poverty remains to be the source of hardships financially, academically, and socially. The way that poverty levels affect the children of the world is a troubling concern. 43 percent of children are currently living in low-income homes while 21% of them are living below the financial poverty threshold set by the federal government (“NCCP | Child Poverty”, 2016). Families with no financial resources do not have access to educational supplies. Without educational resources, these families are constrained to their lives in poverty.

Concept of Poverty

Poverty is the result of not having proper resources to sustain effectively in the community (Sen,2009). This concept of poverty expands the notion that poverty is merely the lack of financial freedom. Although poverty does have direct correlations to finances, it is important to recognize the different facets of poverty and their effects. An aspect of financial income is educational output. Absolute poverty is the lack of financial necessities. This is more common in developing countries, however, it can be found often here in the United States. Absolute poverty will affect children and families as they are not able to provide themselves with materials to further their learning. These materials include a lack of books, pens/pencils or often times children will have no place to do their homework. Poor nutrition has also been found to prevent students from learning effectively. Relative poverty is pre-determined by where a family resides. Where you live typically determines the school your child will attend. Parents often choose their living arrangements based upon cost of living. Schools located in areas meant for these families typically receive little to no funding in comparison. These children will also lack the motivation to do well in school since the perception around them is that school is not important. Poverty lowers educational enrollment and restricts learning environments. To move poverty-stricken school districts in the right direction, they must develop personalized intervention strategies opposed to generalized conclusions.

Poverty in School Readiness

A child’s educational journey starts not from the first day they enter primary school, but from the moment they learn to observe their surroundings, form sentences, and make conclusions from the world around them. Their readiness for school is a clear demonstration of their likelihood to succeed emotionally, socially and academically in school. As determined by the National Education Goals Panel, a child deemed “school ready” is expected to be able to demonstrate five different dimensions of development/knowledge:

physical well-being/motor development

social/emotional development

language development

cognition knowledge

approaches to learning

Children living in poverty are less likely to have these school readiness skills at the same level as a child living in a middle or upper-class family. Research shows that children living in poverty-stricken environments are more likely to suffer from psychiatric disorders, physical health problems and less than average functioning both academically and socially. (Ferguson, 2007). Reversing the effects of children not being classified “school ready” as suggested by Ferguson, is to focus on early childhood intervention as this can help single out health problems, parenting issues, behavioral and social responsiveness.

Academic Achievement

Holistically, poverty is all about a lack of resources. As stated by Misty Lacour & Laura Tissington, these resources are financial, emotional, mental, spiritual, and physical. All of these resources combined lead to the issues faced by children in poverty inside of the classroom. Their studies have also shown that the factors that are a direct result of poverty can cause children to not perform at a high completion rate, academically. Higher incomes have been contributed to better student performance. These findings determined that children from low-income families suffered cognitively, reading/math scores, socially, and emotionally. Children from these households almost always scored below average in comparison to their wealthy peers.

Lacour & Tissington place emphasis on the lack of family systems/subsystems, emotional/mental support and role models as a contribution to low academic achievement. Race and gender were not found to be determining factors– only to show trends/data separated by race. These students in these communities are not receiving funding/experienced teachers to help bridge the gap.

To help boost academic achievement rates from an average of 19% (standardized test percentiles), there should be changes implemented in instructional techniques and strategies provided in the classroom. The three major areas of reform are school environment, home/community environment and policies of the district/state (Lacour & Tissington, 2011).

Change in Schools

Education at any level is a need in society today. The woes of poverty can place a large amount of burden on the shoulders of the educators that teach those students. Standardized testing has been put in place so that school administration can see the overall learning success and failure of their students. Due to this, it can be easy for teachers to place more emphasis on scores and remediation for better numbers. According to Theresa Capra (2009), the constant cycle of new teachers in minority areas negatively impacts the education that is being received. The lack of income obtained by students’ parents is highly associated with their lack of education. “History and evolution have shown that inequality is a reality. As the human race advances, however, it is plausible to think that civilization can prevent the decay of its social constructs through quality, accessible education. Embracing this perspective may help us to completely rethink education, leading to a more progressive system for our future” (Capra, 2009).

Through the research of the great scholars before me, I have realized that poverty is not a two nor three-dimensional issue. I was ignorant to this and now have a better understanding of what it means to be in poverty. Poverty is much more than the lack of financial means. Amartya Sen did a wonderful job of explaining the different aspects of poverty and how it affects the life of the families suffering. Poverty affects the families from functioning properly in their community — they have trouble paying their bills, yet can’t find a decent paying job without a good education. A good education costs money that they don’t have, therefore, the cycle continues. The absolute and relative view is extremely relevant to this detrimental cycle because they categorize the deficiencies caused by poverty.

Children that are from poverty-stricken areas are forced to go into schools that receive very little or no support from their communities. This is saddening — most times when parents request for students to go to a better school (provided they have reliable transportation of their own), they are denied due to the importance of scores. Districts place so much emphasis on scoring on standardized tests rather than the foundation of knowledge needed to succeed. This foundation starts with school readiness skills, which Ferguson & Mueller illustrated wonderfully. When students are not able to establish these skills effectively it sets them up for long-term failures not only academically but mentally and socially as well.

Scarce resources due to poverty such as family systems/subsystems, emotional/mental support, role models and monetary support directly correlate to the low academic achievement levels in students. I n The effects of poverty on academic achieve ment, the authors offered various solutions to close the academic gap such as assessing students through holistic assessments and using voluntary data. While this article provided a lot of important insight on the issues for students living in poverty, it did not give real solutions. In low-income households, children are often disassociated from the resources that middle or high-income students have. Changing the way these students are evaluated through assessments, does not change the education these students are receiving. It only helps them look better statistically.

In contrast, Captra touches on the importance of higher education and the difficulties students face in economically challenged schools.

...(download the rest of the essay above)

About this essay:

If you use part of this page in your own work, you need to provide a citation, as follows:

Essay Sauce, Poverty in education . Available from:<https://www.essaysauce.com/education-essays/poverty-in-education/> [Accessed 07-04-24].

These Education essays have been submitted to us by students in order to help you with your studies.

* This essay may have been previously published on Essay.uk.com at an earlier date.

Essay Categories:

- Accounting essays

- Architecture essays

- Business essays

- Computer science essays

- Criminology essays

- Economics essays

- Education essays

- Engineering essays

- English language essays

- Environmental studies essays

- Essay examples

- Finance essays

- Geography essays

- Health essays

- History essays

- Hospitality and tourism essays

- Human rights essays

- Information technology essays

- International relations

- Leadership essays

- Linguistics essays

- Literature essays

- Management essays

- Marketing essays

- Mathematics essays

- Media essays

- Medicine essays

- Military essays

- Miscellaneous essays

- Music Essays

- Nursing essays

- Philosophy essays

- Photography and arts essays

- Politics essays

- Project management essays

- Psychology essays

- Religious studies and theology essays

- Sample essays

- Science essays

- Social work essays

- Sociology essays

- Sports essays

- Types of essay

- Zoology essays

- Share full article

Advertisement

Supported by

Guest Essay

Is Education No Longer the ‘Great Equalizer’?

By Thomas B. Edsall

Mr. Edsall contributes a weekly column from Washington, D.C., on politics, demographics and inequality.

There is an ongoing debate over what kinds of investment in human capital — roughly the knowledge, skills, habits, abilities, experience, intelligence, training, judgment, creativity and wisdom possessed by an individual — contribute most to productivity and life satisfaction.

Is education no longer “a great equalizer of the conditions of men,” as Horace Mann declared in 1848, but instead a great divider? Can the Biden administration’s efforts to distribute cash benefits to the working class and the poor produce sustained improvements in the lives of those on the bottom tiers of income and wealth — or would a substantial investment in children’s training and enrichment programs at a very early age produce more consistent and permanent results?

Take the case of education. On this score — if the assumption is “the more education, the better” — then the United States looks pretty good.

From 1976 to 2016 the white high school completion rate rose from 86.4 percent to 94.5 percent, the Black completion rate from 73.5 percent to 92.2 percent, and the Hispanic completion rate rose from 60.3 percent to 89.1 percent. The graduation rate of whites entering four-year colleges from 1996 to 2012 rose from 33.7 to 43.7 percent, for African Americans it rose from 19.5 to 23.8 percent and for Hispanics it rose from 22.8 to 34.1 percent.

But these very gains appear to have also contributed to the widening disparity in income between those with different levels of academic attainment, in part because of the very different rates of income growth for men and women with high school degrees, college degrees and graduate or professional degrees.

Education lifts all boats, but not by equal amounts.

David Autor , an economist at M.I.T., together with the Harvard economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz , tackled this issue in a paper last year, “ Extending the Race Between Education and Technology ,” asking: “How much of the overall rise in wage inequality since 1980 can be attributed to the large increase in educational wage differentials?”

Their answer:

Returns to a year of K-12 schooling show little change since 1980. But returns to a year of college rose by 6.5 log points, from 0.076 in 1980 to 0.126 in 2000 to 0.141 in 2017. The returns to a year of post-college (graduate and professional) rose by a whopping 10.9 log points, from 0.067 in 1980 to 0.131 in 2000 and to 0.176 in 2017.

I asked Autor to translate that data into language understandable to the layperson, and he wrote back:

There has been almost no increase in the increment to individual earnings for each year of schooling between K and 12 since 1980. It was roughly 6 percentage points per year in 1980, and it still is. The earnings increment for a B.A. has risen from 30.4 percent in 1980 to 50.4 percent in 2000 to 56.4 percent in 2017. The gain to a four-year graduate degree (a Ph.D., for example, but an M.D., J.D., or perhaps even an M.B.A.) relative to high school was approximately 57 percent in 1980, rising to 127 percent in 2017.

These differences result in large part because ever greater levels of skill — critical thinking, problem-solving, originality, strategizing — are needed in a knowledge-based society.

“The idea of a race between education and technology goes back to the Nobel Laureate Jan Tinbergen , who posited that technological change is continually raising skill requirements while education’s job is to supply those rising skill levels,” Autor wrote in explaining the gains for those with higher levels of income. “If technology ‘gets ahead’ of education, the skill premium will tend to rise.”

But something more homely may also be relevant. Several researchers argue that parenting style contributes to where a child ends up in life.

As the skill premium and the economic cost of failing to ascend the education ladder rise in tandem, scholars find that adults are adopting differing parental styles — a crucial form of investment in the human capital of their children — and these differing styles appear to be further entrenching inequality.

Such key factors as the level of inequality, the degree to which higher education is rewarded and the strength of the welfare state are shaping parental strategies in raising children.

In their paper “ The Economics of Parenting ,” three economists, Matthias Doepke at Northwestern, Giuseppe Sorrenti at University of Zurich and Fabrizio Zilibotti at Yale, describe three basic forms of child rearing:

The permissive parenting style is the scenario where the parent lets the child have her way and refrains from interfering in the choices. The authoritarian style is one where the parent imposes her will through coercion. In the model above, coercion is captured through the notion of restricting the choice set. An authoritarian parent chooses a small set that leaves little or no leeway to the child. The third parenting style, authoritative parenting , is also one where the parent aims to affect the child’s choice. However, rather than using coercion, an authoritative parent uses persuasion: she shapes the child’s preferences through investments in the first period of life. For example, such a parent may preach the virtues of patience or the dangers of risk during when the child is little, so that the child ends up with more adultlike preferences when the child’s own decisions matter during adolescence.

There is an “interaction between economic conditions and parenting styles,” Doepke and his colleagues write, resulting in the following patterns:

Consider, first, a low inequality society, where the gap between the top and the bottom is small. In such a society, there is limited incentive for children to put effort into education. Parents are also less concerned about children’s effort, and thus there is little scope for disagreement between parents and children. Therefore, most parents adopt a permissive parenting style, namely, they keep young children happy and foster their sense of independence so that they can discover what they are good at in their adult life.

The authors cite the Scandinavian countries as key examples of this approach.

Authoritarian parenting, in turn, is most common in less-developed, traditional societies where there is little social mobility and children have the same jobs as their parents:

Parents have little incentive to be permissive in order to let children discover what they are good at. Nor do they need to spend effort in socializing children into adultlike values (i.e., to be authoritative) since they can achieve the same result by simply monitoring them.

Finally, they continue, consider “a high-inequality society”:

There, the disagreement between parents and children is more salient, because parents would like to see their children work hard in school and choose professions with a high return to human capital. In this society, a larger share of parents will be authoritative, and fewer will be permissive.

This model, the authors write, fits the United States and China.

There are some clear downsides to this approach:

Because of the comparative advantage of rich and educated parents in authoritative parenting, there will be a stronger socioeconomic sorting into parenting styles. Since an authoritative parenting style is conducive to more economic success, this sorting will hamper social mobility.

Sorrenti elaborated in an email:

In neighborhoods with higher inequality and with less affluent families, parents tend to be, on average, more authoritarian. Our models and additional analyses show that parents tend to be more authoritarian in response to a social environment perceived as more risky or less inspiring for children. On the other hand, the authoritative parenting styles, aimed at molding child preferences, is a typical parenting style gaining more and more consensus in the U.S., also in more affluent families.

What do these analyses suggest for policies designed to raise those on the lowest tiers of income and educational attainment? Doepke, Sorrenti and Zilibotti agree that major investments in training, socialization and preparation for schooling of very young (4 and under) poor children along the lines of proposals by Nobel Laureate James Heckman , an economist at the University of Chicago, and Roland Fryer , a Harvard economist, can prove effective.

In an October 2020 paper , Fryer and three colleagues described

a novel early childhood intervention in which disadvantaged 3-4-year-old children were randomized to receive a new preschool and parent education program focused on cognitive and noncognitive skills or to a control group that did not receive preschool education. In addition to a typical academic year program, we also evaluated a shortened summer version of the program in which children were treated immediately prior to the start of kindergarten. Both programs, including the shortened version, significantly improved cognitive test scores by about one quarter of a standard deviation relative to the control group at the end of the year.

Heckman, in turn, recently wrote on his website:

A critical time to shape productivity is from birth to age five, when the brain develops rapidly to build the foundation of cognitive and character skills necessary for success in school, health, career and life. Early childhood education fosters cognitive skills along with attentiveness, motivation, self-control and sociability — the character skills that turn knowledge into know-how and people into productive citizens.

Doepke agreed:

In the U.S., the big achievement gaps across lines of race or social class open up very early, before kindergarten, rather than during college. So for reducing overall human capital inequality, building high quality early child care and preschool would be the first place to start.

Zilibotti, in turn, wrote in an email:

We view our work as complementary to Heckman’s work. First, one of the tenets of his analysis is that preferences and attitudes are “malleable,” especially so at an early age. This is against the view that people’s success or failure is largely determined by genes. A fundamental part of these early age investments is parental investment. Our work adds the dimension of “how?” to the traditional perspective of “how much?” That said, what we call “authoritative parenting style” is relative to Heckman’s emphasis on noncognitive skills.

The expansion of the Heckman $13,500-per-child test pilot program to a universal national program received strong support in an economic analysis of its costs and benefits by Diego Daruich , an economist at the University of Southern California. He argues in his 2019 paper “ The Macroeconomic Consequences of Early Childhood Development Policies ” that such an enormous government expenditure would produce substantial gains in social welfare, “an income inequality reduction of 7 percent and an increase in intergenerational mobility of 34 percent.”

As the debate over the effectiveness of education in reducing class and racial income differences continues, the Moving to Opportunity project stresses how children under the age of 13 benefit when they and their families move out of neighborhoods of high poverty concentration into more middle-class communities.

In a widely discussed 2015 paper, “The Effects of Exposure to Better Neighborhoods on Children,” three Harvard economists, Raj Chetty , Nathaniel Hendren and Katz, wrote:

Moving to a lower-poverty neighborhood significantly improves college attendance rates and earnings for children who were young (below age 13) when their families moved. These children also live in better neighborhoods themselves as adults and are less likely to become single parents. The treatment effects are substantial: children whose families take up an experimental voucher to move to a lower-poverty area when they are less than 13 years old have an annual income that is $3,477 (31 percent) higher on average relative to a mean of $11,270 in the control group in their mid-twenties.

There is a long and daunting history of enduring gaps in scholastic achievement correlated with socioeconomic status in the United States that should temper optimism.

In a February 2020 paper — “ Long-Run Trends in the U.S. SES-Achievement Gap ” — Eric A. Hanushek of the Hoover Institution at Stanford, Paul E. Peterson of Harvard’s Kennedy School, Laura M. Talpey of Stanford’s Institute for Economic Policy Research and Ludger Woessmann of the University of Munich report that over nearly 50 years:

The SES-achievement gap between the top and bottom SES quartiles (75-25 SES gap) has remained essentially flat at roughly 0.9 standard deviations, a gap roughly equivalent to a difference of three years of learning between the average student in the top and bottom quartiles of the distribution.

The virtually unchanging SES-achievement gap, the authors continue, “is confirmed in analyses of the achievement gap by subsidized lunch eligibility and in separate estimations by ethnicity that consider changes in the ethnic composition.”

Their conclusion:

The bottom line of our analysis is simply that — despite all the policy efforts — the gap in achievement between children from high- and low-SES backgrounds has not changed. If the goal is to reduce the dependence of students’ achievement on the socio-economic status of their families, re-evaluating the design and focus of existing policy programs seems appropriate. As long as cognitive skills remain critical for the income and economic well-being of U.S. citizens, the unwavering achievement gaps across the SES spectrum do not bode well for future improvements in intergenerational mobility.

The pessimistic implications of this paper have not deterred those devoted to seeking ways to break embedded patterns of inequality and stagnant mobility.

In a November 2019 essay, “ We Have the Tools to Reverse the Rise in Inequality ,” Olivier Blanchard of the Peterson Institute for International Economics and Dani Rodrik , an economist at Harvard, cited the ready availability of a host of policies with strong support among many economists, political scientists and Democrats:

Many areas have low-hanging fruit: expansion of EITC-type programs, increased public funding of both pre-K and tertiary education; redirection of subsidies to employment-friendly innovation, greater overall progressivity in taxation, and policies to help workers reorganize in the face of new production modes.

Adoption of policies calling for aggressive government intervention raises a crucial question, Autor acknowledged in his email: “whether such interventions would kill the golden goose of U.S. innovation and entrepreneurship.” Autor’s answer:

At this point, I’d say the graver threat is from inaction rather than action. If the citizens of a democracy think that “progress” simply means more inequality and stratification, and rising economic insecurity stemming from technology and globalization, they’re eventually going to “cancel” that plan and demand something else — though those demands may not ultimately lead somewhere constructive (e.g., closing U.S. borders, slapping tariffs on numerous friendly trading partners, and starving the government of tax revenue needed to invest in citizens was never going to lead anywhere good).

A promising approach to the augmentation of human capital lies in the exploration of noncognitive skills — perseverance, punctuality, self-restraint, politeness, thoroughness, postponement of gratification, grit — all of which are increasingly valuable in a service-based economy. Noncognitive skills have proved to be teachable, especially among very young children.

Shelly Lundberg , an economics professor at the University of California-Santa Barbara, cites a range of projects and studies, including the Perry Preschool Project, an intensive program for 3-to-4-year-old low-income children “that had long-term impacts on test scores, adult crime and male income.” The potential gains from raising noncognitive skills are wide-ranging, she writes in a chapter of the December 2018 book “ Education, Skills, and Technical Change: Implications for Future US GDP Growth ”:

Noncognitive skills such as attention and self-control can increase the productivity of educational investments. Disruptive behavior and crime impose negative externalities in schools and communities that increased levels of some noncognitive skills could ameliorate.

But, she cautions,

the state of our knowledge about the production of and returns to noncognitive skills is rather rudimentary. We lack a conceptual framework that would enable us to consistently define multidimensional noncognitive skills, and our reliance on observed or reported behavior as measures of skill make it impossible to reliably compare skills across groups that face different environments.

Education, training in cognitive and noncognitive skills, nutrition, health care and parenting are all among the building blocks of human capital, and evidence suggests that continuing investments that combat economic hardship among whites and minorities — and which help defuse debilitating conflicts over values, culture and race — stand the best chance of reversing the disarray and inequality that plague our political system and our social order.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips . And here's our email: [email protected] .

Follow The New York Times Opinion section on Facebook , Twitter (@NYTopinion) and Instagram .

Thomas B. Edsall has been a contributor to the Times Opinion section since 2011. His column on strategic and demographic trends in American politics appears every Wednesday. He previously covered politics for The Washington Post. @ edsall

- Chronicle Conversations

- Article archives

- Issue archives

Reducing Poverty Through Education - and How

About the author, idrissa b. mshoro.

There is no strict consensus on a standard definition of poverty that applies to all countries. Some define poverty through the inequality of income distribution, and some through the miserable human conditions associated with it. Irrespective of such differences, poverty is widespread and acute by all standards in sub-Saharan Africa, where gross domestic product (GDP) is below $1,500 per capita purchasing power parity, where more than 40 per cent of their people live on less than $1 a day, and poor health and schooling hold back productivity. According to the 2009 Human Development Report, sub-Saharan Africa's Human Development Index, which measures development by combining indicators of life expectancy, educational attainment, and income lies in the range of 0.45-0.55, compared to 0.7 and above in other regions of the world. Poverty in sub-Saharan Africa will continue to rise unless the benefits of economic development reach the people. Some sub-Saharan countries have therefore formulated development visions and strategies, identifying respective sources of growth.

Tanzania case study

The Tanzania Development Vision 2025, for example, aims at transforming a low productivity agricultural economy into a semi-industrialized one through medium-term frameworks, the latest being the National Strategy for Growth and Reduction of Poverty (NSGRP). A review of NSGRP implementation, documented in Tanzania's Poverty and Human Development Report 2009, attributed the falling GDP -- from 7.8 per cent in 2004 to 6.7 per cent in 2006 -- to the prolonged drought during 2005/06. A further fall to 5 per cent was projected by 2009 due to the global financial crisis. While the proportion of households living below the poverty line reduced slightly from 35.7 per cent in 2000 to 33.6 per cent in 2007, the actual number of poor Tanzanians is increasing because the population is growing at a faster rate. The 2009 HDR showed a similar trend whereby the Human Development Index in Tanzania shot up from 0.436 to 0.53 between 1990 and 2007, and in the same year the GDP reached $1,208 per capita purchasing power parity. Again, the improvements, though commendable, are still modest when compared with the goal of NSGRP and Millennium Development Goal 1 to reduce by 50 per cent the number of people whose income is less than $1 a day by 2010 and 2015.

More deliberate efforts are therefore required to redress the situation, with more emphasis placed particularly on education, as most poverty-reduction interventions depend on the availability of human capital for spearheading them. The envisaged economic growth depends on the quantity and quality of inputs, including land, natural resources, labour, and technology. Quality of inputs to a great extent relies on embodied knowledge and skills, which are the basis for innovation, technology development and transfer, and increased productivity and competitiveness.

A quick assessment in June 2010 of education statistics in Tanzania indicated that primary school enrolment increased by 5.8 per cent, from 7,959,884 pupils in 2006 to 8,419,305 in 2010. The Gross Enrolment Ratio (GER) was 106.4 per cent. The transition rate from primary to secondary schools, however, decreased by 6.6 per cent from 49.3 per cent in 2005 to 43.9 per cent in 2009. On an annual average, out of 789,739 pupils who completed primary education, only 418,864 continued on to secondary education, notwithstanding the expansion of secondary school enrolment, from 675,672 students in 2006 to 1,638,699 in 2010, a GER increase from 14.8 to 34.0 percent. Moreover, the observed expansion in secondary school education mainly took place from grades one through four, where the number increased from 630,245 in 2006 to 1,566,685 students in 2010. As such, out of 141,527 students who on an annual average completed ordinary secondary education, only 36,014 proceeded to advanced secondary education. Some improvements have also been recorded at the tertiary level. While enrolment in universities was 37,667 students in 2004/05, there were 118,951 in 2009/10.

Adding to this number the students in non-university tertiary institutions totalled 50,173 in 2009/10 and the overall tertiary enrolment reached 169,124 students, providing a GER of 5.3 percent, which is very low.

The observed transition rates imply that, on average, 370,875 primary school children terminate their education journey every year at 13 to 14 years of age in Tanzania. The 17- to 19-year-old secondary school graduates, unable to obtain opportunities for further education, worsen the situation and the overall negative impact on economic growth is very apparent, unless there are other opportunities to develop and empower the secondary school graduates. Vocational education and training could be one such opportunity, but the total current enrolment in vocational education in Tanzania is about 117,000 trainees, which is still far from actual needs. A long-term strategy is therefore critical to expand the capacity for vocational education and training so as to increase the employability of the rising numbers of out-of-school youths. This fact was also apparent in the 2006 Tanzania Integrated Labour Force Survey, which indicated that youth between 15 and 24 years were more likely to be unemployed compared to other age groups because they were entering the labour market for the first time without any skills or work experience. The NSGRP target was to reduce unemployment from 12.9 per cent in 2000/01 to 6.9 per cent by 2010; hence the unemployment rate of 11 per cent in 2006 was disheartening.

One can easily notice that while enrolment in basic education is promising, the situation at other levels remains bleak in meeting poverty reduction targets. Moreover, apart from the noticeably low university enrolment in Tanzania, only 29 per cent of students are taking science and technology courses, probably due to the small catchment pool at lower levels. While this is so, sustainable and broad-based growth requires strengthening of the link between agriculture and industry. Agriculture needs to be modernized for increased productivity and profitability; small and medium enterprises, promoted, with particular emphasis on agro-processing, technology innovation, and upgrading the use of technologies for value addition; and all, with no or minimum negative impact on the environment. Increased investments in human and physical capital are also highly advocated, focusing on efficient and cost-effective provision of infrastructure for energy, information and communication technologies, and transport with special attention to opening up rural and other areas with economic potential. All these point to the promotion of education in science and technology. Special incentives for attracting investments towards accelerating growth are also emphasized. Experience from elsewhere indicates that foreign direct investment contributes effectively to economic growth when the country has a highly-educated workforce. Domestic firms also need to be supported and encouraged to pay attention to product development and innovation for ensuring quality and appropriate marketing strategies that make them competitive and capable of responding to global market conditions.

It is therefore very apparent from the Tanzania example that most of the required interventions for growth and the reduction of poverty require a critical mass of high-quality educated people at different levels to effectively respond to the sustainable development challenges of nations.

The UN Chronicle is not an official record. It is privileged to host senior United Nations officials as well as distinguished contributors from outside the United Nations system whose views are not necessarily those of the United Nations. Similarly, the boundaries and names shown, and the designations used, in maps or articles do not necessarily imply endorsement or acceptance by the United Nations.

From Local Moments to Global Movement: Reparation Mechanisms and a Development Framework

World Down Syndrome Day: A Chance to End the Stereotypes

The international community, led by the United Nations, can continue to improve the lives of people with Down syndrome by addressing stereotypes and misconceptions.

Population and Climate Change: Decent Living for All without Compromising Climate Mitigation

A rise in the demand for energy linked to increasing incomes should not be justification for keeping people in poverty solely to avoid an escalation in emissions and its effects on climate change.

Documents and publications

- Yearbook of the United Nations

- Basic Facts About the United Nations

- Journal of the United Nations

- Meetings Coverage and Press Releases

- United Nations Official Document System (ODS)

- Africa Renewal

Libraries and Archives

- Dag Hammarskjöld Library

- UN Audiovisual Library

- UN Archives and Records Management

- Audiovisual Library of International Law

- UN iLibrary

News and media

- UN News Centre

- UN Chronicle on Twitter

- UN Chronicle on Facebook

The UN at Work

- 17 Goals to Transform Our World

- Official observances

- United Nations Academic Impact (UNAI)

- Protecting Human Rights

- Maintaining International Peace and Security

- The Office of the Secretary-General’s Envoy on Youth

- United Nations Careers

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Springer Nature - PMC COVID-19 Collection

- PMC10265551

The Impact of Education and Culture on Poverty Reduction: Evidence from Panel Data of European Countries

1 Department of Economics, University of Foggia, 71121 Foggia, Italy

2 Department of Agricultural, Food and Forest Sciences, University of Palermo, Viale Delle Scienze, 90128 Palermo, Italy

The 2030 Agenda has among its key objectives the poverty eradication through increasing the level of education. A good level of education and investment in culture of a country is in fact necessary to guarantee a sustainable economy, in which coexists satisfactory levels of quality of life and an equitable distribution of income. There is a lack of studies in particular on the relations between some significant dimensions, such as education, culture and poverty, considering time lags for the measurement of impacts. Therefore, this study aims to fill this gap by focusing on the relationship between education, culture and poverty based on a panel of data from 34 European countries, over a 5-year period, 2015–2019. For this purpose, after applying principal component analysis to avoid multicollinearity problems, the authors applied three different approaches: pooled-ordinary least squares model, fixed effect model and random effect model. Fixed-effects estimator was selected as the optimal and most appropriate model. The results highlight that increasing education and culture levels in these countries reduce poverty. This opens space to new research paths and policy strategies that can start from this connection to implement concrete actions aimed at widening and improving educational and cultural offer.

Introduction

Poverty eradication has been the key objective for spans in many countries since that has been recognized as the greatest hostile issues ‘jeopardising balanced society socio-economic development’ (Balvociute, 2020 ). Poverty can be considered one of the core features of unsustainable socio-economic development and as a persistent phenomenon that can have upsetting effect on peoples’ lives (Bossert et al., 2022 ). For this reason, the extreme poverty removal, as well as the fight against inequalities and injustices, have been placed at the center, with climate change, of the 2030 Sustainable Development Goals. The nature of poverty is multidimensional and inequalities within and among countries is an obstinate origin for concern (Fund, 2015 ; Alvaredo et al., 2017 ; Alkire & Seth, 2015 ; Kwadzo, 2015 ). For its interpretation and measurement, the literature has added to the monetary approach of material deprivation, the social and subjective dimension of the human being (Bellani & D’Ambrosio, 2014 ; Maggino, 2015 ). As stated by Kwadzo ( 2015 ), it is possible to define three poverty measurements: monetary poverty, social exclusion, and capability poverty. Similarly, there are a lot of indicators measuring well-being and quality of life: Index of Happiness, Human Poverty Index and Human Development Index (Senasu et al., 2019 ; Spada et al., 2020 ; UNDP, 1990 ; Veenhoven, 2012 ; Watkins, 2007 ). All these indicators focus and start from education. For example, the Human Poverty Index (HPI) was introduced by the United Nations to complement the Human Development Index (HDI) and used, for the first time, in the 1997 Human Development Report. In 2010, it was replaced by the Multidimensional Poverty Index. The HPI focuses on the deprivation of three essential parameters of human life, already taken into account by the Human Development Index: life expectancy, education and standard of living (Alkire et al., 2015 ; UNDP, 1990 ).

Previous studies shown that education indicators have a large impact on a country’s poverty (Bakhtiari & Meisami, 2010 ; UNDP, 1990 ; Watkins, 2007 ) and that investing in health and education is a way to reduce income inequality and poverty. In addition, studies highlight that increasing equality and the quality of education is essential to combat economic and gender inequality within society (Walker et al., 2019 ). However, few studies provide empirical evidence on how education impacts on income inequality (Liu et al., 2021 ; Santos, 2011 ; Walker et al., 2019 ) and most of these studies analyses the poverty phenomenon neglecting the combined effect of various variables. Different dimensions of poverty have also empirically demonstrated a high degree of correlation (Kwadzo, 2015 ). In addition, the literature review analysis highlighted a gap in quantitative studies, especially on the paths between some relevant dimensions, such as education, culture and poverty, considering time lags for the measurement of impacts. In light of this, the main objectives of this study are: (i) To identify over the five-year period considered (2015–2019), with what delay and with what magnitude and sign, the poverty is influenced by some indicators representative of the educational and cultural dimension; and (ii) Consequently, better calibrate education policies in European countries, in order to achieve a reduction in the poverty rate in the short term, in compliance with the objectives of the 2030 Agenda.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. A literature review regarding the relation between poverty, education and inequalities is presented in Sect. 2 . The Sect. 3 enlightens research gaps linked to the aims of this study and hypothesis to corroborate. Section 4 defines data and summarizes the methodological approach used to reach the work’s aims. Results are presented and discussed in Sect. 5 . Finally, the last section sets out our main conclusions by highlighting limitations of the study and future directions.

Theoretical Framework

The core role of education.

Over the last decades it is possible to individuate in the EU-28 a quickly growing portion of the population having income below 60% of the median disposable income. In addition, there is a share of the population has been becoming more impoverished (Balvociute, 2020 ; EUROSTAT Statistic Explained, 2019 ). In same way, it is possible to speak about “poverty trap”, a mechanisms whereby countries are poor and persist poor: existing poverty appears a straight cause of poverty in the future (Knight et al., 2009 ; Kraay & McKenzie, 2014 ). Aspects such as accommodation, education, medical and material services are considered essential. In particular, an increasing number of empirical studies have supported the positive effects of education on the creation of wealth by individuals and on promoting economic effective and fair development (UNESCO & Global Education Monitoring Report, 2017 ; Walker et al., 2019 ; Xu, 2016 ; Zhang, 2020 ). A research note by European Commission ( 2015 ) shows that individuals with primary education remain the most vulnerable in all EU countries (with a risk of poverty ranging from 13%—Netherlands—to 56% Romania). Even the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the Poverty Reduction Strategy Papers (PRSP) endorsed by the World Bank and ‘Education for All’ program (UNESCO, 2007 ) emphases the significant role of education (Awan et al., 2011 ). A diverse balance can be possible and policy efforts to interrupt the poverty trap might have long-term effects. In this framework, the model proposed by Santos ( 2011 ) shows that a policy oriented towards aligning the quality of education would reduce initial inequalities. In light of this, Shi & Qamruzzaman, ( 2022 ) in a recent work, study, by means of numerous econometrical methods, the tie between investments in education, financial inclusion, and poverty decrease for the period 1995–2018 in 68 nations, underlining the role of education-backed poverty mitigation public policies that need to be more targeted. Several studies demonstrate that level of poverty and education are strictly related. For instance, Bossert et al. ( 2022 ) by focusing on Atkinson-Kolm-Sen index, that measures the percentage income gap of the poor that can be attributed to inequality among the poor (Sen, 1973 , 1976 ), emphasized the close relation between poverty and inequality. Consistent with previous studies, Lenzi and Perruca ( 2022 ) demonstrate that tertiary educated people report higher ranks of life satisfaction. This link is even more marked in rural territories where education is recognised as an important tool for reducing poverty as it allows the acquisition of skills and productive knowledges which increase people’s productivity and their earnings (Tilak, 2002 ). A recent report of the United Nations ( 2021 ) underlines how the reduced access to educational and health services in rural areas becomes a barrier, determining the difficulty of people living in these areas to found employment in well-paid professions contributing to economic growth (Chmelewska and Zegar, 2018 ). However, as Liu and colleagues ( 2021 ) find, different levels of education have distinct effects on poverty in rural areas of China and that the latter is driven not only by factors within the region but also by the level of poverty in the surrounding regions. In addition, numerous empirical evidences reveal a link between educational level and income inequalities in several geopolitical contexts. Bakhtiari and Meisami ( 2010 ), in a work of over 10 years ago, makes use of a panel data set of 37 Islamic countries (eight time periods) to study income inequality along with a model of poverty, with the main variables as income level, health status, education and savings. Findings show that enhancing the health and education can reduce income inequality and poverty. Likewise, as Arafat and Khan ( 2022 ) underline the high level of education not only contributes to reducing the degree of poverty but improves the conditions of mental, social and emotional well-being compared to poorly educated families. After about 10 years, similar works by Wani and Dhami ( 2021 ) and Sabir and Aziz ( 2018 ) reach the same results investigating the SAARC (South Asian Association for Regional Cooperation) countries and 31 developing countries (by employing the System Generalized Method of Moments). In several cases, and especially in rural areas, poverty is linked to the lower level of household income compared to urban areas, resulting in differences in access to basic goods and services to meet personal needs (Chmelewska and Zegar, 2018 ). In this territories household income level is directly associated with food security, in fact, an increase in the level of income reduces food insecurity (Chegini et al., 2021 ). However, as evidenced by other authors (Kirkpatrick et al., 2020 ; Kusio & Fiore, 2022 ), access to education can help to overcome the migration of young people and geographical isolation and inaccessibility that characterize the poor areas (Kvedaraite et al., 2011 ). In turn, young, educated people affect entrepreneurial attitudes. Walker et al. ( 2019 ) in the recent report ‘ The Power of Education to Fight Inequality. How increasing educational equality and quality is crucial to fighting economic and gender inequality ’ show how education can be emancipating for individuals, and it can play the role of a ‘leveler and equalizer within society’. Education interrupts obstinate and rising inequality by promoting the development of more decent work, rising incomes for the poorest people: it can aid to endorse long-lasting, wide-ranging economic growth and social cohesion.

Gradstein and Justman ( 2002 ) underlined the role of education in shaping the social cohesion that can assure equality between individuals. Universal free education enhances people’s earning power, and can bring them out of poverty. Low levels of education hamper economic growth, which in turn slows down poverty reduction (UNESCO, 2017 ; Global Education Monitoring Report, 2019 ) estimates that each year of schooling raises earnings by around 10%;53 this figure is even higher for women. In Tanzania, having a secondary education reduces the chances of being poor as a working adult by almost 60%. According to a study by UNESCO and the Global Education Monitoring Report ( 2019 ), if all adults finished secondary school, 420 million individuals would be lifted out of poverty. The convergence of crises deriving first from COVID-19 then from climate change, and conflicts, are generating extra impacts above all on poverty, nutrition, health and education affecting all the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Equilience, a synchratic neologism composed of Equity + Resilience, that is resilient systems in respect of equity as a balancing of the different interests of the parties. Recent research (Berbés-Blázquez et al., 2021 ; Williams et al., 2020 ; Contò and Fiore, 2020 ) highlight the crucial importance to promote the ‘marriage’ between equity and resilience.

Aims of Study and Hypothesis

This research is potentially the first study to investigate the relationship between educational, cultural factors and poverty in European countries.

The main research directions are as follows: (i) To assess the impact of education and culture (expressed by the following indicators: Cultural employment, Total educational expenditure, Graduates in tertiary education, Number of enterprises in the cultural sectors, Tertiary educational attainment ) upon poverty (indicated by Persons at risk of poverty or social ); (ii) To compare the strength and direction of the relationships between the variables considered in two temporal situations, i.e. with zero lag, and with lag equal to one year. The data cover the period 2015–2019 and were extracted from the Eurostat database.

In the light of the above discussion, of the literature review analysis, and of the theoretical frameworks examined this study explores the following research hypotheses with regard to the European context:

Education and culture have an inverse impact on the levels of poverty.

Our second hypothesis states:

The association between cultural, educational variables and poverty, in the short term is more intense if we consider a delay of one-year.

The dataset is a balanced panel of annual observations for 34 European countries and covers the period from 2015 to 2019. On the basis of literature findings, our analysis focused on the following dimensions: education, income inequality and poverty.

Thereby, the variables considered for our investigation are as follows:

- Poverty indicator: Persons at risk of poverty or social exclusion (% of population, thousand persons; hereinafter labelled with PRP);

- Education and cultural indicators: Cultural employment (thousand persons); Total educational expenditure (million euros); Graduates in tertiary education (‰ of population;); Number of enterprises in the cultural sectors (number) Tertiary educational attainment (‰ of population). Respectively, hereinafter they will be labelled with CE, TEE, GTE, NEC and TEA.

The indicators have been extracted from the Eurostat database. The summary statistics are reported in Table Table1. 1 . In the selected time period, Iceland is the country that shows the lowest values with respect PRP (12.08%). Instead, the country showing the worst performance is Romania (PRP = 41.60%). With regard to the education indicators, Germany holds the highest values for both CE (81,661.48 thousand persons) and TEE (30.588.86 million euros), highlighting great attention to education issues. Instead, in Eastern Europe (Montenegro, Romania, and Hungary) the indicators pertaining to the education area take on more penalized values. Italy is the country that boasts the largest number of enterprises in the cultural sector (NEC = 179,136.8), thanks also to the artistic beauties of which this country is rich. As far as the tertiary education level is concerned, the highest value of is held by Cyprus while the lowest by Romania (respectively TEA = 57.34 and TEA = 25.26). For subsequent processing, since the variables considered are both in the form of ratios and counts, all data were converted to natural logarithms.

Summary statistics for the Eurostat datasets, 2015–2019

Methodology

The methodological approach used is based on linear panel data models including the simple Pooled Ordinary Least Square (pooled OLS) model, the Fixed Effects (FE) model and the Random Effects (RE) model. Before proceeding with the application of the linear models, the correlation matrix between the variables taken into consideration was performed and subsequently, to avoid multicollinearity problems and distorted estimates, the study, based on the principal component analysis (PCA), used two indicators related to education and culture. According to Jolliffe and Cadima ( 2016 ), through PCA starting from a set of correlated variables, a set of uncorrelated variables is obtained, known as Principal Components (PC). In PCA, only common factors that have an eigenvalue greater than one or greater than the mean should be kept (Jolliffe, 2002 ; Kaiser, 1974 ). In this study PCA allowed to obtain the following indicators: EDU1, which includes CE, NEC, TEE, and EDU2, composed of TEA and GTE. These indicators have been incorporated into the panel data models, replacing the original variables.

The first linear panel data model adopted is the pooled OLS, which assumes no heterogeneity between countries, whose equation is as follows:

where ln PRP is the natural logarithm of the poverty indicator, α is the intercept, EDU is composed of the principal components extracted, ε is the error term, i denotes statistical units, in this case countries, and t denotes the time index.

The second model adopted is FE which controls for cross-country heterogeneity and is expressed as:

where α i is the regional specific parameter denoting the fixed effect. The basic intuition of the FE model is that α i does not change over time.

Finally, the third model is RE denoted as;

In the RE model, variations between units are assumed to be random and uncorrelated with the independent variables in the model.

To verify the two research hypotheses, for each of the three models (pooled OLS, FE and RE) two versions were calculated, with lag 0 and lag 1 year. In the model at lag 0 the variables are synchronous, while in the model at lag 1 principal components enter the equation with a one-year lag compared to PRP. The choice of the reference model between pooled OLS, FE and RE is based on several tests. In choosing between FE and pooled OLS, the study applies the F-test. A p-value of less than 5% indicates that there are important country effects that OLS fails to detect, and that thus neglecting unobserved heterogeneity in the model can lead to estimation errors and inconsistencies. The study also tests which is better between the OLS and RE model using the Breusch-Pagan (BP)-Langragian Multiplier (LM) test. The null hypothesis of the BP-LM test is that there is no substantial variance between regions. A probability value of less than 5% for the BP-LM test indicates that the RE model is appropriate and the OLS pool is not. Finally, the Hausman test χ 2 is also performed to compare the FE model and the RE model. According to Algieri and Mannarino ( 2013 ), the Hausman test χ 2 aims to identify a violation of the RE modelling hypothesis. In this test, the alternative hypothesis is that the FE model is preferable to the RE model, while the null hypothesis is that both models produce similar coefficients. A p-value greater than 5% denotes that both FE and RE are reliable, but the RE model is more efficient because it uses a lower degree of freedom. We also test for heteroskedasticity in the FE model using the modified Wald test developed by Lasker and King ( 1997 ). The null hypothesis of this test is that the variance of the error is similar for all countries (Amaz et al., 2012 ). All statistical analyses were conducted in Stata 17.0 (Stata Corp LP, College Station, Texas, USA). A critical value of p < 0.05 was specified a priori as the threshold of statistical significance for all analyses.

The relationships between the variables, measured by Pearson’s linear correlation coefficient, is shown in Table Table2. 2 . It is noted that the PRP variable is negatively correlated with all the other panel variables, albeit with modest correlations. Instead, TEE shows a high positive correlation with NEC ( r = 0.963 and r = 0.903, respectively). There is also a high correlation between NEC and TEE ( r = 0.857). Therefore, in the light of the results, to exclude the problem of multicollinearity between the covariates, we proceeded to analyse the principal components.

Pearson correlation coefficient

* p < 0.05, ** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

Table Table3 3 shows the results of principal component analysis. On the basis of these results, the need to maintain the first two principal components is highlighted, since their eigenvalues are greater or very close to 1 and cumulatively represent the 84% of the information. They will be labelled as EDU1 and EDU2 respectively. EDU1 refers to TEE, CE and NEC, i.e. it refers to a cultural dimension of the country and therefore, even if not strictly connected to the school environment, with an important educational role, while the EDU2 component referring to GTE and TEA, is more closely related to the school.

Principal component analysis: factor loading, eigen value and variance explained

Table Table4 4 shows the results of the three econometric models (pooled OLS, FE, RE) on the link between education, culture and poverty. It is observed that all models converge in showing that poverty decreases with increasing education and culture. In particular, the EDU1 indicator always shows a negative coefficient, and this relationship is statistically significant in the model fixed at lag 0 and lag 1 (respectively b = − 0.3804, p < 0.001; b = − 0.3925, p < 0.001). Furthermore, for EDU1, in all three econometric models it can be noted that the coefficients are higher in absolute value passing from lag 0 to lag 1, highlighting that the impact between cultural and educational tools and poverty reduction occurs with a delay, perhaps necessary to have positive results. Also, the EDU2 indicator always shows a negative coefficient and this relationship is statistically significant in all three models, both at lag 0 and at lag 1 (for all p < 0.001). To discern the econometric model that best fits the data, as a first step the F-test allows you to choose between the OLS and FE models. The value F = 80.09 for lag 0 and F = 109.61for lag = 1, (for all p -value < 0.001), indicates in both cases that the FE model is more suitable than the pooled OLS. This demonstrates that in the relationships examined time plays an important role, which a simple OLS model may fail to capture, i.e. EDU1 and EDU2 have an effect on poverty decrease that changes over time. The choice between the RE model and the pooled OLS was instead based on the BP LM test, which suggests that the RE model is more suitable than the pooled OLS. Finally, the Hausman test χ 2 allows to identify which between FE and RE is more suitable: The value χ 2 = 15.95 at lag 0 and χ 2 = 13.40 at lag = 1, (for all p -value < 0.001) suggests that the FE model is more suitable than the RE model, indicating the presence of non-random differences between countries or over time. The model that best fits the examined panel of data is therefore the FE model.

Pooled OLS, Fixed Model, Random Model, at lag 0 and at lag 1

** p < 0.01, *** p < 0.001

In light of these results, as supposed in hypothesis H 1 , it is evident that education and culture play a significant role in poverty reduction. Furthermore, as supposed by hypothesis H 2 and based on the FE model which was found to be the most suitable, this impact is more intense if one considers a year of delay, above all for cultural and educational variables relating to a dimension that is not strictly scholastic.

Discussions and Conclusions

The present study analysed the relationship between education, culture and poverty for 34 countries, over the period 2015–2019. The findings indicate that rising education and culture levels in these nations reduce poverty. The model also highlighted that this relationship is weaker if we consider a contemporaneity of the values of the variables (at lag 0), while it is strengthened if we consider a time interval of one year.

As policy-makers regularly disclose the consequences of unfair development by identifying problems requiring solutions built on evidence-based guidelines, these results can have interesting and fruitful implications. By concluding, education appears, in line with other studies (Sabir & Aziz, 2018 ; Xu, 2016 ), one of the best effective methods to eradicate poverty. In line with the work by Walker et al., ( 2019 ), investing in universal-free-public education for all the persons can close different circles: the gap between rich and poor people, between women and men, between poor and rich areas within a country and among countries. In addition, education appears crucial to fight inequalities across the world. The results appear also consistent with the UN report ( 2021 ) that emphasizes the importance of the access to educational and health services in marginal poor areas to improve and contribute equal economic growth and reduce poverty (Chmelewska and Zegar, 2018 ; Bakhtiari & Meisami, 2010 ; Wani & Dhami, 2021 ). The same findings come from the work by Peng ( 2019 ) based on data from poor Chinese provinces showing that education has steady and positive impacts on farmers’ income, and the outcome of growing income in poor zones is higher than in other areas.

All in all, as evidenced by the European Commission ( 2015 ), the means to diminish the risk of poverty appears ‘straight-forward: go to school, get a job’. Clearly, these implications have to consider conditions and country environment. In line with previous research (Noper Ardi & Isnayanti, 2020 ; Walker et al., 2019 ), these results highlight that education can have an immediate impact on income inequalities and poverty; on the other hand, education (and public spending on it) has a longer-term impact on inequality through its effects in enhancing future salaries and chances. Indeed, as stated by some notable researchers (Kraay & McKenzie, 2014 ), the ‘more-likely poverty traps’ need action in less-traditional policy areas. The scholars have to further perfect the theoretical concepts and policy standards of poverty alleviation through education (Shi & Qamruzzaman, 2022 ).

This paper reinforces the conclusions deriving from other research (Mou and Xu, 2020 ; Assari et al., 2018 ; Batool and Batool, 2018 ) that are to give evidence of how education can forecast coming ‘Emotional Well-Being’ thus decreasing the inequalities by means of more generous policies and strategies. The latter can support international experience-based education (Xu, 2016 ).

In the following research phases, other variables can be inserted to improve the specifications of the model and also verify the existence of homogeneous groups of countries. In addition, a distinction between urban and rural areas to highlight the link between income, education and poverty and differences could enrich the literature and provide useful information to guide national policies in a targeted way. Regarding possible limitations of the paper, it is possible to notice a time period limited for missing data and health variables are missing.

The ‘dark’ side of this conclusions is considering the effects of the COVID19 pandemic that has increased on one hand the online teaching and training: on the other hand, education has become more difficult in remote, rural and/or marginal areas due to connections and hardware limitations.

Therefore, nowadays strategies, models and polices focusing on equi-lience (equity and resilience) processes can promote the creation of a different balance between the needs of sustainable growth and those of social, fair and environmental development (Fiore, 2022 ). Therefore, developing a strategy to convey a trained, skilled and well-supported workforce, investing in relevant and fair teaching resources, ensuring funds and building better liability mechanisms from national to local levels can be significant and fair paths to reduce poverty and inequalities. These strategies have to be aimed at developing national education plans that try to identify pre-education existing inequalities in order to arrange actions in poorer rural and marginalized districts or regions.

Open access funding provided by Università di Foggia within the CRUI-CARE Agreement.

Declarations

Authors disclose financial or non-financial interests directly or indirectly related to the work submitted for publication.

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

- Alkire S, Foster JE, Seth S, Santos ME, Roche JM, Ballon P. Multidimensional poverty measurement and analysis. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2015. [ Google Scholar ]

- Alkire S, Seth S. Multidimensional poverty reduction in india between 1999 and 2006: Where and how? World Development. 2015; 72 (C):93–108. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2015.02.009. [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Algieri, B., & Mannarino, L. (2013). The role of credit conditions and local financial development on export performances: A focus on the Italian Regions, Universita della Calabria, Dipartimento di Economia e Statistica. Retrieved from http://www.ecostat.unical.it/WP2/WP/10_A%20panel%20analysis%20for%20the%20sectoral%20manufacturing%20exports.pdf

- Alvaredo, F., Chancel, L. Piketty, T., Saez E. and G. Zucman. (2017). The world inequality Report 2018. World Inequality Lab. http://wir2018.wid.world/

- Amaz, C., Gaume, V., & Lefevre, M. (2012). The impact of training on firm scrap rate: A study of panel data. Retrieved from http://www-perso.gate.cnrs.fr/polome/Pages2012_13/Panel/LEFEVRE_GAUME_AMAZ_rapport.pdf