- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

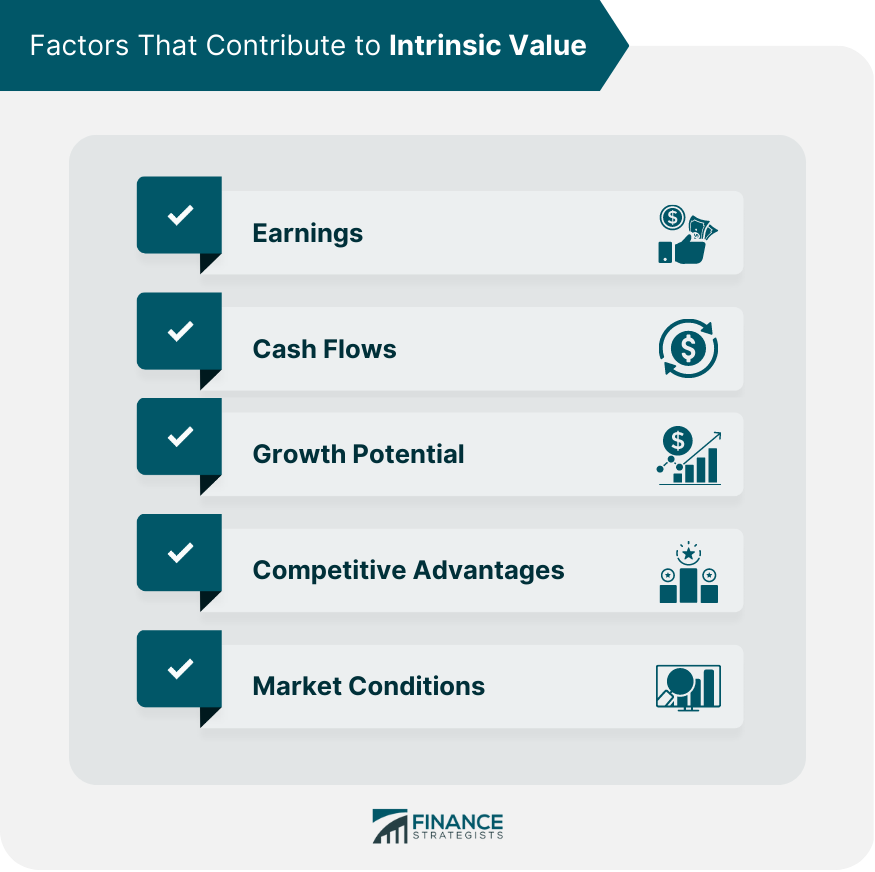

Intrinsic vs. Extrinsic Value

Intrinsic value has traditionally been thought to lie at the heart of ethics. Philosophers use a number of terms to refer to such value. The intrinsic value of something is said to be the value that that thing has “in itself,” or “for its own sake,” or “as such,” or “in its own right.” Extrinsic value is value that is not intrinsic.

Many philosophers take intrinsic value to be crucial to a variety of moral judgments. For example, according to a fundamental form of consequentialism, whether an action is morally right or wrong has exclusively to do with whether its consequences are intrinsically better than those of any other action one can perform under the circumstances. Many other theories also hold that what it is right or wrong to do has at least in part to do with the intrinsic value of the consequences of the actions one can perform. Moreover, if, as is commonly believed, what one is morally responsible for doing is some function of the rightness or wrongness of what one does, then intrinsic value would seem relevant to judgments about responsibility, too. Intrinsic value is also often taken to be pertinent to judgments about moral justice (whether having to do with moral rights or moral desert), insofar as it is good that justice is done and bad that justice is denied, in ways that appear intimately tied to intrinsic value. Finally, it is typically thought that judgments about moral virtue and vice also turn on questions of intrinsic value, inasmuch as virtues are good, and vices bad, again in ways that appear closely connected to such value.

All four types of moral judgments have been the subject of discussion since the dawn of western philosophy in ancient Greece. The Greeks themselves were especially concerned with questions about virtue and vice, and the concept of intrinsic value may be found at work in their writings and in the writings of moral philosophers ever since. Despite this fact, and rather surprisingly, it is only within the last one hundred years or so that this concept has itself been the subject of sustained scrutiny, and even within this relatively brief period the scrutiny has waxed and waned.

1. What Has Intrinsic Value?

2. what is intrinsic value, 3. is there such a thing as intrinsic value at all, 4. what sort of thing can have intrinsic value, 5. how is intrinsic value to be computed, 6. what is extrinsic value, cited works, other works, other internet resources, related entries.

The question “What is intrinsic value?” is more fundamental than the question “What has intrinsic value?,” but historically these have been treated in reverse order. For a long time, philosophers appear to have thought that the notion of intrinsic value is itself sufficiently clear to allow them to go straight to the question of what should be said to have intrinsic value. Not even a potted history of what has been said on this matter can be attempted here, since the record is so rich. Rather, a few representative illustrations must suffice.

In his dialogue Protagoras , Plato [428–347 B.C.E.] maintains (through the character of Socrates, modeled after the real Socrates [470–399 B.C.E.], who was Plato’s teacher) that, when people condemn pleasure, they do so, not because they take pleasure to be bad as such, but because of the bad consequences they find pleasure often to have. For example, at one point Socrates says that the only reason why the pleasures of food and drink and sex seem to be evil is that they result in pain and deprive us of future pleasures (Plato, Protagoras , 353e). He concludes that pleasure is in fact good as such and pain bad, regardless of what their consequences may on occasion be. In the Timaeus , Plato seems quite pessimistic about these consequences, for he has Timaeus declare pleasure to be “the greatest incitement to evil” and pain to be something that “deters from good” (Plato, Timaeus , 69d). Plato does not think of pleasure as the “highest” good, however. In the Republic , Socrates states that there can be no “communion” between “extravagant” pleasure and virtue (Plato, Republic , 402e) and in the Philebus , where Philebus argues that pleasure is the highest good, Socrates argues against this, claiming that pleasure is better when accompanied by intelligence (Plato, Philebus , 60e).

Many philosophers have followed Plato’s lead in declaring pleasure intrinsically good and pain intrinsically bad. Aristotle [384–322 B.C.E.], for example, himself a student of Plato’s, says at one point that all are agreed that pain is bad and to be avoided, either because it is bad “without qualification” or because it is in some way an “impediment” to us; he adds that pleasure, being the “contrary” of that which is to be avoided, is therefore necessarily a good (Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics , 1153b). Over the course of the more than two thousand years since this was written, this view has been frequently endorsed. Like Plato, Aristotle does not take pleasure and pain to be the only things that are intrinsically good and bad, although some have maintained that this is indeed the case. This more restrictive view, often called hedonism, has had proponents since the time of Epicurus [341–271 B.C.E.]. [ 1 ] Perhaps the most thorough renditions of it are to be found in the works of Jeremy Bentham [1748–1832] and Henry Sidgwick [1838–1900] (see Bentham 1789, Sidgwick 1907); perhaps its most famous proponent is John Stuart Mill [1806–1873] (see Mill 1863).

Most philosophers who have written on the question of what has intrinsic value have not been hedonists; like Plato and Aristotle, they have thought that something besides pleasure and pain has intrinsic value. One of the most comprehensive lists of intrinsic goods that anyone has suggested is that given by William Frankena (Frankena 1973, pp. 87–88): life, consciousness, and activity; health and strength; pleasures and satisfactions of all or certain kinds; happiness, beatitude, contentment, etc.; truth; knowledge and true opinions of various kinds, understanding, wisdom; beauty, harmony, proportion in objects contemplated; aesthetic experience; morally good dispositions or virtues; mutual affection, love, friendship, cooperation; just distribution of goods and evils; harmony and proportion in one’s own life; power and experiences of achievement; self-expression; freedom; peace, security; adventure and novelty; and good reputation, honor, esteem, etc. (Presumably a corresponding list of intrinsic evils could be provided.) Almost any philosopher who has ever addressed the question of what has intrinsic value will find his or her answer represented in some way by one or more items on Frankena’s list. (Frankena himself notes that he does not explicitly include in his list the communion with and love and knowledge of God that certain philosophers believe to be the highest good, since he takes them to fall under the headings of “knowledge” and “love.”) One conspicuous omission from the list, however, is the increasingly popular view that certain environmental entities or qualities have intrinsic value (although Frankena may again assert that these are implicitly represented by one or more items already on the list). Some find intrinsic value, for example, in certain “natural” environments (wildernesses untouched by human hand); some find it in certain animal species; and so on.

Suppose that you were confronted with some proposed list of intrinsic goods. It would be natural to ask how you might assess the accuracy of the list. How can you tell whether something has intrinsic value or not? On one level, this is an epistemological question about which this article will not be concerned. (See the entry in this encyclopedia on moral epistemology.) On another level, however, this is a conceptual question, for we cannot be sure that something has intrinsic value unless we understand what it is for something to have intrinsic value.

The concept of intrinsic value has been characterized above in terms of the value that something has “in itself,” or “for its own sake,” or “as such,” or “in its own right.” The custom has been not to distinguish between the meanings of these terms, but we will see that there is reason to think that there may in fact be more than one concept at issue here. For the moment, though, let us ignore this complication and focus on what it means to say that something is valuable for its own sake as opposed to being valuable for the sake of something else to which it is related in some way. Perhaps it is easiest to grasp this distinction by way of illustration.

Suppose that someone were to ask you whether it is good to help others in time of need. Unless you suspected some sort of trick, you would answer, “Yes, of course.” If this person were to go on to ask you why acting in this way is good, you might say that it is good to help others in time of need simply because it is good that their needs be satisfied. If you were then asked why it is good that people’s needs be satisfied, you might be puzzled. You might be inclined to say, “It just is.” Or you might accept the legitimacy of the question and say that it is good that people’s needs be satisfied because this brings them pleasure. But then, of course, your interlocutor could ask once again, “What’s good about that?” Perhaps at this point you would answer, “It just is good that people be pleased,” and thus put an end to this line of questioning. Or perhaps you would again seek to explain the fact that it is good that people be pleased in terms of something else that you take to be good. At some point, though, you would have to put an end to the questions, not because you would have grown tired of them (though that is a distinct possibility), but because you would be forced to recognize that, if one thing derives its goodness from some other thing, which derives its goodness from yet a third thing, and so on, there must come a point at which you reach something whose goodness is not derivative in this way, something that “just is” good in its own right, something whose goodness is the source of, and thus explains, the goodness to be found in all the other things that precede it on the list. It is at this point that you will have arrived at intrinsic goodness (cf. Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics , 1094a). That which is intrinsically good is nonderivatively good; it is good for its own sake. That which is not intrinsically good but extrinsically good is derivatively good; it is good, not (insofar as its extrinsic value is concerned) for its own sake, but for the sake of something else that is good and to which it is related in some way. Intrinsic value thus has a certain priority over extrinsic value. The latter is derivative from or reflective of the former and is to be explained in terms of the former. It is for this reason that philosophers have tended to focus on intrinsic value in particular.

The account just given of the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic value is rough, but it should do as a start. Certain complications must be immediately acknowledged, though. First, there is the possibility, mentioned above, that the terms traditionally used to refer to intrinsic value in fact refer to more than one concept; again, this will be addressed later (in this section and the next). Another complication is that it may not in fact be accurate to say that whatever is intrinsically good is nonderivatively good; some intrinsic value may be derivative. This issue will be taken up (in Section 5) when the computation of intrinsic value is discussed; it may be safely ignored for now. Still another complication is this. It is almost universally acknowledged among philosophers that all value is “supervenient” or “grounded in” on certain nonevaluative features of the thing that has value. Roughly, what this means is that, if something has value, it will have this value in virtue of certain nonevaluative features that it has; its value can be attributed to these features. For example, the value of helping others in time of need might be attributed to the fact that such behavior has the feature of being causally related to certain pleasant experiences induced in those who receive the help. Suppose we accept this and accept also that the experiences in question are intrinsically good. In saying this, we are (barring the complication to be discussed in Section 5) taking the value of the experiences to be nonderivative. Nonetheless, we may well take this value, like all value, to be supervenient on, or grounded in, something. In this case, we would probably simply attribute the value of the experiences to their having the feature of being pleasant. This brings out the subtle but important point that the question whether some value is derivative is distinct from the question whether it is supervenient. Even nonderivative value (value that something has in its own right; value that is, in some way, not attributable to the value of anything else) is usually understood to be supervenient on certain nonevaluative features of the thing that has value (and thus to be attributable, in a different way, to these features ).

To repeat: whatever is intrinsically good is (barring the complication to be discussed in Section 5) nonderivatively good. It would be a mistake, however, to affirm the converse of this and say that whatever is nonderivatively good is intrinsically good. As “intrinsic value” is traditionally understood, it refers to a particular way of being nonderivatively good; there are other ways in which something might be nonderivatively good. For example, suppose that your interlocutor were to ask you whether it is good to eat and drink in moderation and to exercise regularly. Again, you would say, “Yes, of course.” If asked why, you would say that this is because such behavior promotes health. If asked what is good about being healthy, you might cite something else whose goodness would explain the value of health, or you might simply say, “Being healthy just is a good way to be.” If the latter were your response, you would be indicating that you took health to be nonderivatively good in some way. In what way, though? Well, perhaps you would be thinking of health as intrinsically good. But perhaps not. Suppose that what you meant was that being healthy just is “good for” the person who is healthy (in the sense that it is in each person’s interest to be healthy), so that John’s being healthy is good for John, Jane’s being healthy is good for Jane, and so on. You would thereby be attributing a type of nonderivative interest-value to John’s being healthy, and yet it would be perfectly consistent for you to deny that John’s being healthy is intrinsically good. If John were a villain, you might well deny this. Indeed, you might want to insist that, in light of his villainy, his being healthy is intrinsically bad , even though you recognize that his being healthy is good for him . If you did say this, you would be indicating that you subscribe to the common view that intrinsic value is nonderivative value of some peculiarly moral sort. [ 2 ]

Let us now see whether this still rough account of intrinsic value can be made more precise. One of the first writers to concern himself with the question of what exactly is at issue when we ascribe intrinsic value to something was G. E. Moore [1873–1958]. In his book Principia Ethica , Moore asks whether the concept of intrinsic value (or, more particularly, the concept of intrinsic goodness, upon which he tended to focus) is analyzable. In raising this question, he has a particular type of analysis in mind, one which consists in “breaking down” a concept into simpler component concepts. (One example of an analysis of this sort is the analysis of the concept of being a vixen in terms of the concepts of being a fox and being female.) His own answer to the question is that the concept of intrinsic goodness is not amenable to such analysis (Moore 1903, ch. 1). In place of analysis, Moore proposes a certain kind of thought-experiment in order both to come to understand the concept better and to reach a decision about what is intrinsically good. He advises us to consider what things are such that, if they existed by themselves “in absolute isolation,” we would judge their existence to be good; in this way, we will be better able to see what really accounts for the value that there is in our world. For example, if such a thought-experiment led you to conclude that all and only pleasure would be good in isolation, and all and only pain bad, you would be a hedonist. [ 3 ] Moore himself deems it incredible that anyone, thinking clearly, would reach this conclusion. He says that it involves our saying that a world in which only pleasure existed—a world without any knowledge, love, enjoyment of beauty, or moral qualities—is better than a world that contained all these things but in which there existed slightly less pleasure (Moore 1912, p. 102). Such a view he finds absurd.

Regardless of the merits of this isolation test, it remains unclear exactly why Moore finds the concept of intrinsic goodness to be unanalyzable. At one point he attacks the view that it can be analyzed wholly in terms of “natural” concepts—the view, that is, that we can break down the concept of being intrinsically good into the simpler concepts of being A , being B , being C …, where these component concepts are all purely descriptive rather than evaluative. (One candidate that Moore discusses is this: for something to be intrinsically good is for it to be something that we desire to desire.) He argues that any such analysis is to be rejected, since it will always be intelligible to ask whether (and, presumably, to deny that) it is good that something be A , B , C ,…, which would not be the case if the analysis were accurate (Moore 1903, pp. 15–16). Even if this argument is successful (a complicated matter about which there is considerable disagreement), it of course does not establish the more general claim that the concept of intrinsic goodness is not analyzable at all, since it leaves open the possibility that this concept is analyzable in terms of other concepts, some or all of which are not “natural” but evaluative. Moore apparently thinks that his objection works just as well where one or more of the component concepts A , B , C ,…, is evaluative; but, again, many dispute the cogency of his argument. Indeed, several philosophers have proposed analyses of just this sort. For example, Roderick Chisholm [1916–1999] has argued that Moore’s own isolation test in fact provides the basis for an analysis of the concept of intrinsic value. He formulates a view according to which (to put matters roughly) to say that a state of affairs is intrinsically good or bad is to say that it is possible that its goodness or badness constitutes all the goodness or badness that there is in the world (Chisholm 1978).

Eva Bodanszky and Earl Conee have attacked Chisholm’s proposal, showing that it is, in its details, unacceptable (Bodanszky and Conee 1981). However, the general idea that an intrinsically valuable state is one that could somehow account for all the value in the world is suggestive and promising; if it could be adequately formulated, it would reveal an important feature of intrinsic value that would help us better understand the concept. We will return to this point in Section 5. Rather than pursue such a line of thought, Chisholm himself responded (Chisholm 1981) in a different way to Bodanszky and Conee. He shifted from what may be called an ontological version of Moore’s isolation test—the attempt to understand the intrinsic value of a state in terms of the value that there would be if it were the only valuable state in existence —to an intentional version of that test—the attempt to understand the intrinsic value of a state in terms of the kind of attitude it would be fitting to have if one were to contemplate the valuable state as such, without reference to circumstances or consequences.

This new analysis in fact reflects a general idea that has a rich history. Franz Brentano [1838–1917], C. D. Broad [1887–1971], W. D. Ross [1877–1971], and A. C. Ewing [1899–1973], among others, have claimed, in a more or less qualified way, that the concept of intrinsic goodness is analyzable in terms of the fittingness of some “pro” (i.e., positive) attitude (Brentano 1969, p. 18; Broad 1930, p. 283; Ross 1939, pp. 275–76; Ewing 1948, p. 152). Such an analysis, which has come to be called “the fitting attitude analysis” of value, is supported by the mundane observation that, instead of saying that something is good, we often say that it is valuable , which itself just means that it is fitting to value the thing in question. It would thus seem very natural to suppose that for something to be intrinsically good is simply for it to be such that it is fitting to value it for its own sake. (“Fitting” here is often understood to signify a particular kind of moral fittingness, in keeping with the idea that intrinsic value is a particular kind of moral value. The underlying point is that those who value for its own sake that which is intrinsically good thereby evince a kind of moral sensitivity.)

Though undoubtedly attractive, this analysis can be and has been challenged. Brand Blanshard [1892–1987], for example, argues that the analysis is to be rejected because, if we ask why something is such that it is fitting to value it for its own sake, the answer is that this is the case precisely because the thing in question is intrinsically good; this answer indicates that the concept of intrinsic goodness is more fundamental than that of the fittingness of some pro attitude, which is inconsistent with analyzing the former in terms of the latter (Blanshard 1961, pp. 284–86). Ewing and others have resisted Blanshard’s argument, maintaining that what grounds and explains something’s being valuable is not its being good but rather its having whatever non-value property it is upon which its goodness supervenes; they claim that it is because of this underlying property that the thing in question is “both” good and valuable (Ewing 1948, pp. 157 and 172. Cf. Lemos 1994, p. 19). Thomas Scanlon calls such an account of the relation between valuableness, goodness, and underlying properties a buck-passing account, since it “passes the buck” of explaining why something is such that it is fitting to value it from its goodness to some property that underlies its goodness (Scanlon 1998, pp. 95 ff.). Whether such an account is acceptable has recently been the subject of intense debate. Many, like Scanlon, endorse passing the buck; some, like Blanshard, object to doing so. If such an account is acceptable, then Ewing’s analysis survives Blanshard’s challenge; but otherwise not. (Note that one might endorse passing the buck and yet reject Ewing’s analysis for some other reason. Hence a buck-passer may, but need not, accept the analysis. Indeed, there is reason to think that Moore himself is a buck-passer, even though he takes the concept of intrinsic goodness to be unanalyzable; cf. Olson 2006).

Even if Blanshard’s argument succeeds and intrinsic goodness is not to be analyzed in terms of the fittingness of some pro attitude, it could still be that there is a strict correlation between something’s being intrinsically good and its being such that it is fitting to value it for its own sake; that is, it could still be both that (a) it is necessarily true that whatever is intrinsically good is such that it is fitting to value it for its own sake, and that (b) it is necessarily true that whatever it is fitting to value for its own sake is intrinsically good. If this were the case, it would reveal an important feature of intrinsic value, recognition of which would help us to improve our understanding of the concept. However, this thesis has also been challenged.

Krister Bykvist has argued that what he calls solitary goods may constitute a counterexample to part (a) of the thesis (Bykvist 2009, pp. 4 ff.). Such (alleged) goods consist in states of affairs that entail that there is no one in a position to value them. Suppose, for example, that happiness is intrinsically good, and good in such a way that it is fitting to welcome it. Then, more particularly, the state of affairs of there being happy egrets is intrinsically good; so too, presumably, is the more complex state of affairs of there being happy egrets but no welcomers. The simpler state of affairs would appear to pose no problem for part (a) of the thesis, but the more complex state of affairs, which is an example of a solitary good, may pose a problem. For if to welcome a state of affairs entails that that state of affairs obtains, then welcoming the more complex state of affairs is logically impossible. Furthermore, if to welcome a state of affairs entails that one believes that that state of affairs obtains, then the pertinent belief regarding the more complex state of affairs would be necessarily false. In neither case would it seem plausible to say that welcoming the state of affairs is nonetheless fitting. Thus, unless this challenge can somehow be met, a proponent of the thesis must restrict the thesis to pro attitudes that are neither truth- nor belief-entailing, a restriction that might itself prove unwelcome, since it excludes a number of favorable responses to what is good (such as promoting what is good, or taking pleasure in what is good) to which proponents of the thesis have often appealed.

As to part (b) of the thesis: some philosophers have argued that it can be fitting to value something for its own sake even if that thing is not intrinsically good. A relatively early version of this argument was again provided by Blanshard (1961, pp. 287 ff. Cf. Lemos 1994, p. 18). Recently the issue has been brought into stark relief by the following sort of thought-experiment. Imagine that an evil demon wants you to value him for his own sake and threatens to cause you severe suffering unless you do. It seems that you have good reason to do what he wants—it is appropriate or fitting to comply with his demand and value him for his own sake—even though he is clearly not intrinsically good (Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen 2004, pp. 402 ff.). This issue, which has come to be known as “the wrong kind of reason problem,” has attracted a great deal of attention. Some have been persuaded that the challenge succeeds, while others have sought to undermine it.

One final cautionary note. It is apparent that some philosophers use the term “intrinsic value” and similar terms to express some concept other than the one just discussed. In particular, Immanuel Kant [1724–1804] is famous for saying that the only thing that is “good without qualification” is a good will, which is good not because of what it effects or accomplishes but “in itself” (Kant 1785, Ak. 1–3). This may seem to suggest that Kant ascribes (positive) intrinsic value only to a good will, declaring the value that anything else may possess merely extrinsic, in the senses of “intrinsic value” and “extrinsic value” discussed above. This suggestion is, if anything, reinforced when Kant immediately adds that a good will “is to be esteemed beyond comparison as far higher than anything it could ever bring about,” that it “shine[s] like a jewel for its own sake,” and that its “usefulness…can neither add to, nor subtract from, [its] value.” For here Kant may seem not only to be invoking the distinction between intrinsic and extrinsic value but also to be in agreement with Brentano et al. regarding the characterization of the former in terms of the fittingness of some attitude, namely, esteem. (The term “respect” is often used in place of “esteem” in such contexts.) Nonetheless, it becomes clear on further inspection that Kant is in fact discussing a concept quite different from that with which this article is concerned. A little later on he says that all rational beings, even those that lack a good will, have “absolute value”; such beings are “ends in themselves” that have a “dignity” or “intrinsic value” that is “above all price” (Kant 1785, Ak. 64 and 77). Such talk indicates that Kant believes that the sort of value that he ascribes to rational beings is one that they possess to an infinite degree. But then, if this were understood as a thesis about intrinsic value as we have been understanding this concept, the implication would seem to be that, since it contains rational beings, ours is the best of all possible worlds. [ 4 ] Yet this is a thesis that Kant, along with many others, explicitly rejects elsewhere (Kant, Lectures in Ethics ). It seems best to understand Kant, and other philosophers who have since written in the same vein (cf. Anderson 1993), as being concerned not with the question of what intrinsic value rational beings have—in the sense of “intrinsic value” discussed above—but with the quite different question of how we ought to behave toward such creatures (cf. Bradley 2006).

In the history of philosophy, relatively few seem to have entertained doubts about the concept of intrinsic value. Much of the debate about intrinsic value has tended to be about what things actually do have such value. However, once questions about the concept itself were raised, doubts about its metaphysical implications, its moral significance, and even its very coherence began to appear.

Consider, first, the metaphysics underlying ascriptions of intrinsic value. It seems safe to say that, before the twentieth century, most moral philosophers presupposed that the intrinsic goodness of something is a genuine property of that thing, one that is no less real than the properties (of being pleasant, of satisfying a need, or whatever) in virtue of which the thing in question is good. (Several dissented from this view, however. Especially well known for their dissent are Thomas Hobbes [1588–1679], who believed the goodness or badness of something to be constituted by the desire or aversion that one may have regarding it, and David Hume [1711–1776], who similarly took all ascriptions of value to involve projections of one’s own sentiments onto whatever is said to have value. See Hobbes 1651, Hume 1739.) It was not until Moore argued that this view implies that intrinsic goodness, as a supervening property, is a very different sort of property (one that he called “nonnatural”) from those (which he called “natural”) upon which it supervenes, that doubts about the view proliferated.

One of the first to raise such doubts and to press for a view quite different from the prevailing view was Axel Hägerström [1868–1939], who developed an account according to which ascriptions of value are neither true nor false (Hägerström 1953). This view has come to be called “noncognitivism.” The particular brand of noncognitivism proposed by Hägerström is usually called “emotivism,” since it holds (in a manner reminiscent of Hume) that ascriptions of value are in essence expressions of emotion. (For example, an emotivist of a particularly simple kind might claim that to say “ A is good” is not to make a statement about A but to say something like “Hooray for A !”) This view was taken up by several philosophers, including most notably A. J. Ayer [1910–1989] and Charles L. Stevenson [1908–1979] (see Ayer 1946, Stevenson 1944). Other philosophers have since embraced other forms of noncognitivism. R. M. Hare [1919–2002], for example, advocated the theory of “prescriptivism” (according to which moral judgments, including judgments about goodness and badness, are not descriptive statements about the world but rather constitute a kind of command as to how we are to act; see Hare 1952) and Simon Blackburn and Allan Gibbard have since proposed yet other versions of noncognitivism (Blackburn 1984, Gibbard 1990).

Hägerström characterized his own view as a type of “value-nihilism,” and many have followed suit in taking noncognitivism of all kinds to constitute a rejection of the very idea of intrinsic value. But this seems to be a mistake. We should distinguish questions about value from questions about evaluation . Questions about value fall into two main groups, conceptual (of the sort discussed in the last section) and substantive (of the sort discussed in the first section). Questions about evaluation have to do with what precisely is going on when we ascribe value to something. Cognitivists claim that our ascriptions of value constitute statements that are either true or false; noncognitivists deny this. But even noncognitivists must recognize that our ascriptions of value fall into two fundamental classes—ascriptions of intrinsic value and ascriptions of extrinsic value—and so they too must concern themselves with the very same conceptual and substantive questions about value as cognitivists address. It may be that noncognitivism dictates or rules out certain answers to these questions that cognitivism does not, but that is of course quite a different matter from rejecting the very idea of intrinsic value on metaphysical grounds.

Another type of metaphysical challenge to intrinsic value stems from the theory of “pragmatism,” especially in the form advanced by John Dewey [1859–1952] (see Dewey 1922). According to the pragmatist, the world is constantly changing in such a way that the solution to one problem becomes the source of another, what is an end in one context is a means in another, and thus it is a mistake to seek or offer a timeless list of intrinsic goods and evils, of ends to be achieved or avoided for their own sakes. This theme has been elaborated by Monroe Beardsley, who attacks the very notion of intrinsic value (Beardsley 1965; cf. Conee 1982). Denying that the existence of something with extrinsic value presupposes the existence of something else with intrinsic value, Beardsley argues that all value is extrinsic. (In the course of his argument, Beardsley rejects the sort of “dialectical demonstration” of intrinsic value that was attempted in the last section, when an explanation of the derivative value of helping others was given in terms of some nonderivative value.) A quick response to Beardsley’s misgivings about intrinsic value would be to admit that it may well be that, the world being as complex as it is, nothing is such that its value is wholly intrinsic; perhaps whatever has intrinsic value also has extrinsic value, and of course many things that have extrinsic value will have no (or, at least, neutral) intrinsic value. Far from repudiating the notion of intrinsic value, though, this admission would confirm its legitimacy. But Beardsley would insist that this quick response misses the point of his attack, and that it really is the case, not just that whatever has value has extrinsic value, but also that nothing has intrinsic value. His argument for this view is based on the claim that the concept of intrinsic value is “inapplicable,” in that, even if something had such value, we could not know this and hence its having such value could play no role in our reasoning about value. But here Beardsley seems to be overreaching. Even if it were the case that we cannot know whether something has intrinsic value, this of course leaves open the question whether anything does have such value. And even if it could somehow be shown that nothing does have such value, this would still leave open the question whether something could have such value. If the answer to this last question is “yes,” then the legitimacy of the concept of intrinsic value is in fact confirmed rather than refuted.

As has been noted, some philosophers do indeed doubt the legitimacy, the very coherence, of the concept of intrinsic value. Before we turn to a discussion of this issue, however, let us for the moment presume that the concept is coherent and address a different sort of doubt: the doubt that the concept has any great moral significance. Recall the suggestion, mentioned in the last section, that discussions of intrinsic value may have been compromised by a failure to distinguish certain concepts. This suggestion is at the heart of Christine Korsgaard’s “Two Distinctions in Goodness” (Korsgaard 1983). Korsgaard notes that “intrinsic value” has traditionally been contrasted with “instrumental value” (the value that something has in virtue of being a means to an end) and claims that this approach is misleading. She contends that “instrumental value” is to be contrasted with “final value,” that is, the value that something has as an end or for its own sake; however, “intrinsic value” (the value that something has in itself, that is, in virtue of its intrinsic, nonrelational properties) is to be contrasted with “extrinsic value” (the value that something has in virtue of its extrinsic, relational properties). (An example of a nonrelational property is the property of being round; an example of a relational property is the property of being loved.) As an illustration of final value, Korsgaard suggests that gorgeously enameled frying pans are, in virtue of the role they play in our lives, good for their own sakes. In like fashion, Beardsley wonders whether a rare stamp may be good for its own sake (Beardsley 1965); Shelly Kagan says that the pen that Abraham Lincoln used to sign the Emancipation Proclamation may well be good for its own sake (Kagan 1998); and others have offered similar examples (cf. Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen 1999 and 2003). Notice that in each case the value being attributed to the object in question is (allegedly) had in virtue of some extrinsic property of the object. This puts the moral significance of intrinsic value into question, since (as is apparent from our discussion so far) it is with the notion of something’s being valuable for its own sake that philosophers have traditionally been, and continue to be, primarily concerned.

There is an important corollary to drawing a distinction between intrinsic value and final value (and between extrinsic value and nonfinal value), and that is that, contrary to what Korsgaard herself initially says, it may be a mistake to contrast final value with instrumental value. If it is possible, as Korsgaard claims, that final value sometimes supervenes on extrinsic properties, then it might be possible that it sometimes supervenes in particular on the property of being a means to some other end. Indeed, Korsgaard herself suggests this when she says that “certain kinds of things, such as luxurious instruments, … are valued for their own sakes under the condition of their usefulness” (Korsgaard 1983, p. 185). Kagan also tentatively endorses this idea. If the idea is coherent, then we should in principle distinguish two kinds of instrumental value, one final and the other nonfinal. [ 5 ] If something A is a means to something else B and has instrumental value in virtue of this fact, such value will be nonfinal if it is merely derivative from or reflective of B ’s value, whereas it will be final if it is nonderivative, that is, if it is a value that A has in its own right (due to the fact that it is a means to B ), irrespective of any value that B may or may not have in its own right.

Even if it is agreed that it is final value that is central to the concerns of moral philosophers, we should be careful in drawing the conclusion that intrinsic value is not central to their concerns. First, there is no necessity that the term “intrinsic value” be reserved for the value that something has in virtue of its intrinsic properties; presumably it has been used by many writers simply to refer to what Korsgaard calls final value, in which case the moral significance of (what is thus called) intrinsic value has of course not been thrown into doubt. Nonetheless, it should probably be conceded that “final value” is a more suitable term than “intrinsic value” to refer to the sort of value in question, since the latter term certainly does suggest value that supervenes on intrinsic properties. But here a second point can be made, and that is that, even if use of the term “intrinsic value” is restricted accordingly, it is arguable that, contrary to Korsgaard’s contention, all final value does after all supervene on intrinsic properties alone; if that were the case, there would seem to be no reason not to continue to use the term “intrinsic value” to refer to final value. Whether this is in fact the case depends in part on just what sort of thing can be valuable for its own sake—an issue to be taken up in the next section.

In light of the matter just discussed, we must now decide what terminology to adopt. It is clear that moral philosophers since ancient times have been concerned with the distinction between the value that something has for its own sake (the sort of nonderivative value that Korsgaard calls “final value”) and the value that something has for the sake of something else to which it is related in some way. However, given the weight of tradition, it seems justifiable, perhaps even advisable, to continue, despite Korsgaard’s misgivings, to use the terms “intrinsic value” and “extrinsic value” to refer to these two types of value; if we do so, however, we should explicitly note that this practice is not itself intended to endorse, or reject, the view that intrinsic value supervenes on intrinsic properties alone.

Let us now turn to doubts about the very coherence of the concept of intrinsic value, so understood. In Principia Ethica and elsewhere, Moore embraces the consequentialist view, mentioned above, that whether an action is morally right or wrong turns exclusively on whether its consequences are intrinsically better than those of its alternatives. Some philosophers have recently argued that ascribing intrinsic value to consequences in this way is fundamentally misconceived. Peter Geach, for example, argues that Moore makes a serious mistake when comparing “good” with “yellow.” [ 6 ] Moore says that both terms express unanalyzable concepts but are to be distinguished in that, whereas the latter refers to a natural property, the former refers to a nonnatural one. Geach contends that there is a mistaken assimilation underlying Moore’s remarks, since “good” in fact operates in a way quite unlike that of “yellow”—something that Moore wholly overlooks. This contention would appear to be confirmed by the observation that the phrase “ x is a yellow bird” splits up logically (as Geach puts it) into the phrase “ x is a bird and x is yellow,” whereas the phrase “ x is a good singer” does not split up in the same way. Also, from “ x is a yellow bird” and “a bird is an animal” we do not hesitate to infer “ x is a yellow animal,” whereas no similar inference seems warranted in the case of “ x is a good singer” and “a singer is a person.” On the basis of these observations Geach concludes that nothing can be good in the free-standing way that Moore alleges; rather, whatever is good is good relative to a certain kind.

Judith Thomson has recently elaborated on Geach’s thesis (Thomson 1997). Although she does not unqualifiedly agree that whatever is good is good relative to a certain kind, she does claim that whatever is good is good in some way; nothing can be “just plain good,” as she believes Moore would have it. Philippa Foot, among others, has made a similar charge (Foot 1985). It is a charge that has been rebutted by Michael Zimmerman, who argues that Geach’s tests are less straightforward than they may seem and fail after all to reveal a significant distinction between the ways in which “good” and “yellow” operate (Zimmerman 2001, ch. 2). He argues further that Thomson mischaracterizes Moore’s conception of intrinsic value. According to Moore, he claims, what is intrinsically good is not “just plain good”; rather, it is good in a particular way, in keeping with Thomson’s thesis that all goodness is goodness in a way. He maintains that, for Moore and other proponents of intrinsic value, such value is a particular kind of moral value. Mahrad Almotahari and Adam Hosein have revived Geach’s challenge (Almotahari and Hosein 2015). They argue that if, contrary to Geach, “good” could be used predicatively, we would be able to use the term predicatively in sentences of the form ‘ a is a good K ’ but, they argue, the linguistic evidence indicates that we cannot do so (Almotahari and Hosein 2015, 1493–4).

Among those who do not doubt the coherence of the concept of intrinsic value there is considerable difference of opinion about what sort or sorts of entity can have such value. Moore does not explicitly address this issue, but his writings show him to have a liberal view on the matter. There are times when he talks of individual objects (e.g., books) as having intrinsic value, others when he talks of the consciousness of individual objects (or of their qualities) as having intrinsic value, others when he talks of the existence of individual objects as having intrinsic value, others when he talks of types of individual objects as having intrinsic value, and still others when he talks of states of individual objects as having intrinsic value.

Moore would thus appear to be a “pluralist” concerning the bearers of intrinsic value. Others take a more conservative, “monistic” approach, according to which there is just one kind of bearer of intrinsic value. Consider, for example, Frankena’s long list of intrinsic goods, presented in Section 1 above: life, consciousness, etc. To what kind(s) of entity do such terms refer? Various answers have been given. Some (such as Panayot Butchvarov) claim that it is properties that are the bearers of intrinsic value (Butchvarov 1989, pp. 14–15). On this view, Frankena’s list implies that it is the properties of being alive, being conscious, and so on, that are intrinsically good. Others (such as Chisholm) claim that it is states of affairs that are the bearers of intrinsic value (Chisholm 1968–69, 1972, 1975). On this view, Frankena’s list implies that it is the states of affairs of someone (or something) being alive, someone being conscious, and so on, that are intrinsically good. Still others (such as Ross) claim that it is facts that are the bearers of intrinsic value (Ross 1930, pp. 112–13; cf. Lemos 1994, ch. 2). On this view, Frankena’s list implies that it is the facts that someone (or something) is alive, that someone is conscious, and so on, that are intrinsically good. (The difference between Chisholm’s and Ross’s views would seem to be this: whereas Chisholm would ascribe intrinsic value even to states of affairs, such as that of everyone being happy, that do not obtain, Ross would ascribe such value only to states of affairs that do obtain.)

Ontologists often divide entities into two fundamental classes, those that are abstract and those that are concrete. Unfortunately, there is no consensus on just how this distinction is to be drawn. Most philosophers would classify the sorts of entities just mentioned (properties, states of affairs, and facts) as abstract. So understood, the claim that intrinsic value is borne by such entities is to be distinguished from the claim that it is borne by certain other closely related entities that are often classified as concrete. For example, it has recently been suggested that it is tropes that have intrinsic value. [ 7 ] Tropes are supposed to be a sort of particularized property, a kind of property-instance (rather than simply a property). (Thus the particular whiteness of a particular piece of paper is to be distinguished, on this view, from the property of whiteness.) It has also been suggested that it is states, understood as a kind of instance of states of affairs, that have intrinsic value (cf. Zimmerman 2001, ch. 3).

Those who make monistic proposals of the sort just mentioned are aware that intrinsic value is sometimes ascribed to kinds of entities different from those favored by their proposals. They claim that all such ascriptions can be reduced to, or translated into, ascriptions of intrinsic value of the sort they deem proper. Consider, for example, Korsgaard’s suggestion that a gorgeously enameled frying pan is good for its own sake. Ross would say that this cannot be the case. If there is any intrinsic value to be found here, it will, according to Ross, not reside in the pan itself but in the fact that it plays a certain role in our lives, or perhaps in the fact that something plays this role, or in the fact that something that plays this role exists. (Others would make other translations in the terms that they deem appropriate.) On the basis of this ascription of intrinsic value to some fact, Ross could go on to ascribe a kind of extrinsic value to the pan itself, in virtue of its relation to the fact in question.

Whether reduction of this sort is acceptable has been a matter of considerable debate. Proponents of monism maintain that it introduces some much-needed order into the discussion of intrinsic value, clarifying just what is involved in the ascription of such value and simplifying the computation of such value—on which point, see the next section. (A corollary of some monistic approaches is that the value that something has for its own sake supervenes on the intrinsic properties of that thing, so that there is a perfect convergence of the two sorts of values that Korsgaard calls “final” and “intrinsic”. On this point, see the last section; Zimmerman 2001, ch. 3; Tucker 2016; and Tucker (forthcoming).) Opponents argue that reduction results in distortion and oversimplification; they maintain that, even if there is intrinsic value to be found in such a fact as that a gorgeously enameled frying pan plays a certain role in our lives, there may yet be intrinsic , and not merely extrinsic, value to be found in the pan itself and perhaps also in its existence (cf. Rabinowicz and Rønnow-Rasmussen 1999 and 2003). Some propose a compromise according to which the kind of intrinsic value that can sensibly be ascribed to individual objects like frying pans is not the same kind of intrinsic value that is the topic of this article and can sensibly be ascribed to items of the sort on Frankena’s list (cf. Bradley 2006). (See again the cautionary note in the final paragraph of Section 2 above.)

In our assessments of intrinsic value, we are often and understandably concerned not only with whether something is good or bad but with how good or bad it is. Arriving at an answer to the latter question is not straightforward. At least three problems threaten to undermine the computation of intrinsic value.

First, there is the possibility that the relation of intrinsic betterness is not transitive (that is, the possibility that something A is intrinsically better than something else B , which is itself intrinsically better than some third thing C , and yet A is not intrinsically better than C ). Despite the very natural assumption that this relation is transitive, it has been argued that it is not (Rachels 1998; Temkin 1987, 1997, 2012). Should this in fact be the case, it would seriously complicate comparisons, and hence assessments, of intrinsic value.

Second, there is the possibility that certain values are incommensurate. For example, Ross at one point contends that it is impossible to compare the goodness of pleasure with that of virtue. Whereas he had suggested in The Right and the Good that pleasure and virtue could be measured on the same scale of goodness, in Foundations of Ethics he declares this to be impossible, since (he claims) it would imply that pleasure of a certain intensity, enjoyed by a sufficient number of people or for a sufficient time, would counterbalance virtue possessed or manifested only by a small number of people or only for a short time; and this he professes to be incredible (Ross 1939, p. 275). But there is some confusion here. In claiming that virtue and pleasure are incommensurate for the reason given, Ross presumably means that they cannot be measured on the same ratio scale. (A ratio scale is one with an arbitrary unit but a fixed zero point. Mass and length are standardly measured on ratio scales.) But incommensurability on a ratio scale does not imply incommensurability on every scale—an ordinal scale, for instance. (An ordinal scale is simply one that supplies an ordering for the quantity in question, such as the measurement of arm-strength that is provided by an arm-wrestling competition.) Ross’s remarks indicate that he in fact believes that virtue and pleasure are commensurate on an ordinal scale, since he appears to subscribe to the arch-puritanical view that any amount of virtue is intrinsically better than any amount of pleasure. This view is just one example of the thesis that some goods are “higher” than others, in the sense that any amount of the former is better than any amount of the latter. This thesis can be traced to the ancient Greeks (Plato, Philebus , 21a-e; Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics , 1174a), and it has been endorsed by many philosophers since, perhaps most famously by Mill (Mill 1863, paras. 4 ff). Interest in the thesis has recently been revived by a set of intricate and intriguing puzzles, posed by Derek Parfit, concerning the relative values of low-quantity/high-quality goods and high-quantity/low-quality goods (Parfit 1984, Part IV). One response to these puzzles (eschewed by Parfit himself) is to adopt the thesis of the nontransitivity of intrinsic betterness. Another is to insist on the thesis that some goods are higher than others. Such a response does not by itself solve the puzzles that Parfit raises, but, to the extent that it helps, it does so at the cost of once again complicating the computation of intrinsic value.

To repeat: contrary to what Ross says, the thesis that some goods are higher than others implies that such goods are commensurate, and not that they are incommensurate. Some people do hold, however, that certain values really are incommensurate and thus cannot be compared on any meaningful scale. (Isaiah Berlin [1909–1997], for example, is often thought to have said this about the values of liberty and equality. Whether he is best interpreted in this way is debatable. See Berlin 1969.) This view constitutes a more radical threat to the computation of intrinsic value than does the view that intrinsic betterness is not transitive. The latter view presupposes at least some measure of commensurability. If A is better than B and B is better than C , then A is commensurate with B and B is commensurate with C ; and even if it should turn out that A is not better than C , it may still be that A is commensurate with C , either because it is as good as C or because it is worse than C . But if A is incommensurate with B , then A is neither better than nor as good as nor worse than B . (Some claim, however, that the reverse does not hold and that, even if A is neither better than nor as good as nor worse than B , still A may be “on a par” with B and thus be roughly comparable with it. Cf. Chang 1997, 2002.) If such a case can arise, there is an obvious limit to the extent to which we can meaningfully say how good a certain complex whole is (here, “whole” is used to refer to whatever kind of entity may have intrinsic value); for, if such a whole comprises incommensurate goods A and B , then there will be no way of establishing just how good it is overall, even if there is a way of establishing how good it is with respect to each of A and B .

There is a third, still more radical threat to the computation of intrinsic value. Quite apart from any concern with the commensurability of values, Moore famously claims that there is no easy formula for the determination of the intrinsic value of complex wholes because of the truth of what he calls the “principle of organic unities” (Moore 1903, p. 96). According to this principle, the intrinsic value of a whole must not be assumed to be the same as the sum of the intrinsic values of its parts (Moore 1903, p. 28) As an example of an organic unity, Moore gives the case of the consciousness of a beautiful object; he says that this has great intrinsic value, even though the consciousness as such and the beautiful object as such each have comparatively little, if any, intrinsic value. If the principle of organic unities is true, then there is scant hope of a systematic approach to the computation of intrinsic value. Although the principle explicitly rules out only summation as a method of computation, Moore’s remarks strongly suggest that there is no relation between the parts of a whole and the whole itself that holds in general and in terms of which the value of the latter can be computed by aggregating (whether by summation or by some other means) the values of the former. Moore’s position has been endorsed by many other philosophers. For example, Ross says that it is better that one person be good and happy and another bad and unhappy than that the former be good and unhappy and the latter bad and happy, and he takes this to be confirmation of Moore’s principle (Ross 1930, p. 72). Broad takes organic unities of the sort that Moore discusses to be just one instance of a more general phenomenon that he believes to be at work in many other situations, as when, for example, two tunes, each pleasing in its own right, make for a cacophonous combination (Broad 1985, p. 256). Others have furnished still further examples of organic unities (Chisholm 1986, ch. 7; Lemos 1994, chs. 3 and 4, and 1998; Hurka 1998).

Was Moore the first to call attention to the phenomenon of organic unities in the context of intrinsic value? This is debatable. Despite the fact that he explicitly invoked what he called a “principle of summation” that would appear to be inconsistent with the principle of organic unities, Brentano appears nonetheless to have anticipated Moore’s principle in his discussion of Schadenfreude , that is, of malicious pleasure; he condemns such an attitude, even though he claims that pleasure as such is intrinsically good (Brentano 1969, p. 23 n). Certainly Chisholm takes Brentano to be an advocate of organic unities (Chisholm 1986, ch. 5), ascribing to him the view that there are many kinds of organic unity and building on what he takes to be Brentano’s insights (and, going further back in the history of philosophy, the insights of St. Thomas Aquinas [1225–1274] and others).

Recently, a special spin has been put on the principle of organic unities by so-called “particularists.” Jonathan Dancy, for example, has claimed (in keeping with Korsgaard and others mentioned in Section 3 above), that something’s intrinsic value need not supervene on its intrinsic properties alone; in fact, the supervenience-base may be so open-ended that it resists generalization. The upshot, according to Dancy, is that the intrinsic value of something may vary from context to context; indeed, the variation may be so great that the thing’s value changes “polarity” from good to bad, or vice versa (Dancy 2000). This approach to value constitutes an endorsement of the principle of organic unities that is even more subversive of the computation of intrinsic value than Moore’s; for Moore holds that the intrinsic value of something is and must be constant, even if its contribution to the value of wholes of which it forms a part is not, whereas Dancy holds that variation can occur at both levels.

Not everyone has accepted the principle of organic unities; some have held out hope for a more systematic approach to the computation of intrinsic value. However, even someone who is inclined to measure intrinsic value in terms of summation must acknowledge that there is a sense in which the principle of organic unities is obviously true. Consider some complex whole, W , that is composed of three goods, X , Y , and Z , which are wholly independent of one another. Suppose that we had a ratio scale on which to measure these goods, and that their values on this scale were 10, 20, and 30, respectively. We would expect someone who takes intrinsic value to be summative to declare the value of W to be (10 + 20 + 30 =) 60. But notice that, if X , Y , and Z are parts of W , then so too, presumably, are the combinations X -and- Y , X -and- Z , and Y -and- Z ; the values of these combinations, computed in terms of summation, will be 30, 40, and 50, respectively. If the values of these parts of W were also taken into consideration when evaluating W , the value of W would balloon to 180. Clearly, this would be a distortion. Someone who wishes to maintain that intrinsic value is summative must thus show not only how the various alleged examples of organic unities provided by Moore and others are to be reinterpreted, but also how, in the sort of case just sketched, it is only the values of X , Y , and Z , and not the values either of any combinations of these components or of any parts of these components, that are to be taken into account when evaluating W itself. In order to bring some semblance of manageability to the computation of intrinsic value, this is precisely what some writers, by appealing to the idea of “basic” intrinsic value, have tried to do. The general idea is this. In the sort of example just given, each of X , Y , and Z is to be construed as having basic intrinsic value; if any combinations or parts of X , Y , and Z have intrinsic value, this value is not basic; and the value of W is to be computed by appealing only to those parts of W that have basic intrinsic value.

Gilbert Harman was one of the first explicitly to discuss basic intrinsic value when he pointed out the apparent need to invoke such value if we are to avoid distortions in our evaluations (Harman 1967). However, he offers no precise account of the concept of basic intrinsic value and ends his paper by saying that he can think of no way to show that nonbasic intrinsic value is to be computed in terms of the summation of basic intrinsic value. Several philosophers have since tried to do better. Many have argued that nonbasic intrinsic value cannot always be computed by summing basic intrinsic value. Suppose that states of affairs can bear intrinsic value. Let X be the state of affairs of John being pleased to a certain degree x , and Y be the state of affairs of Jane being displeased to a certain degree y , and suppose that X has a basic intrinsic value of 10 and Y a basic intrinsic value of −20. It seems reasonable to sum these values and attribute an intrinsic value of −10 to the conjunctive state of affairs X&Y . But what of the disjunctive state of affairs XvY or the negative state of affairs ~X ? How are their intrinsic values to be computed? Summation seems to be a nonstarter in these cases. Nonetheless, attempts have been made even in such cases to show how the intrinsic value of a complex whole is to be computed in a nonsummative way in terms of the basic intrinsic values of simpler states, thus preserving the idea that basic intrinsic value is the key to the computation of all intrinsic value (Quinn 1974, Chisholm 1975, Oldfield 1977, Carlson 1997). (These attempts have generally been based on the assumption that states of affairs are the sole bearers of intrinsic value. Matters would be considerably more complicated if it turned out that entities of several different ontological categories could all have intrinsic value.)

Suggestions as to how to compute nonbasic intrinsic value in terms of basic intrinsic value of course presuppose that there is such a thing as basic intrinsic value, but few have attempted to provide an account of what basic intrinsic value itself consists in. Fred Feldman is one of the few (Feldman 2000; cf. Feldman 1997, pp. 116–18). Subscribing to the view that only states of affairs bear intrinsic value, Feldman identifies several features that any state of affairs that has basic intrinsic value in particular must possess. He maintains, for example, that whatever has basic intrinsic value must have it to a determinate degree and that this value cannot be “defeated” by any Moorean organic unity. In this way, Feldman seeks to preserve the idea that intrinsic value is summative after all. He does not claim that all intrinsic value is to be computed by summing basic intrinsic value, but he does insist that the value of entire worlds is to be computed in this way.

Despite the detail in which Feldman characterizes the concept of basic intrinsic value, he offers no strict analysis of it. Others have tried to supply such an analysis. For example, by noting that, even if it is true that only states have intrinsic value, it may yet be that not all states have intrinsic value, Zimmerman suggests (to put matters somewhat roughly) that basic intrinsic value is the intrinsic value had by states none of whose proper parts have intrinsic value (Zimmerman 2001, ch. 5). On this basis he argues that disjunctive and negative states in fact have no intrinsic value at all, and thereby seeks to show how all intrinsic value is to be computed in terms of summation after all.

Two final points. First, we are now in a position to see why it was said above (in Section 2) that perhaps not all intrinsic value is nonderivative. If it is correct to distinguish between basic and nonbasic intrinsic value and also to compute the latter in terms of the former, then there is clearly a respectable sense in which nonbasic intrinsic value is derivative. Second, if states with basic intrinsic value account for all the value that there is in the world, support is found for Chisholm’s view (reported in Section 2) that some ontological version of Moore’s isolation test is acceptable.

At the beginning of this article, extrinsic value was said simply—too simply—to be value that is not intrinsic. Later, once intrinsic value had been characterized as nonderivative value of a certain, perhaps moral kind, extrinsic value was said more particularly to be derivative value of that same kind . That which is extrinsically good is good, not (insofar as its extrinsic value is concerned) for its own sake, but for the sake of something else to which it is related in some way. For example, the goodness of helping others in time of need is plausibly thought to be extrinsic (at least in part), being derivative (at least in part) from the goodness of something else, such as these people’s needs being satisfied, or their experiencing pleasure, to which helping them is related in some causal way.

Two questions arise. The first is whether so-called extrinsic value is really a type of value at all. There would seem to be a sense in which it is not, for it does not add to or detract from the value in the world. Consider some long chain of derivation. Suppose that the extrinsic value of A can be traced to the intrinsic value of Z by way of B , C , D … Thus A is good (for example) because of B , which is good because of C , and so on, until we get to Y ’s being good because of Z ; when it comes to Z , however, we have something that is good, not because of something else, but “because of itself,” i.e., for its own sake. In this sort of case, the values of A , B , …, Y are all parasitic on the value of Z . It is Z ’s value that contributes to the value there is in the world; A , B , …, Y contribute no value of their own. (As long as the value of Z is the only intrinsic value at stake, no change of value would be effected in or imparted to the world if a shorter route from A to Z were discovered, one that bypassed some letters in the middle of the alphabet.)

Why talk of “extrinsic value” at all, then? The answer can only be that we just do say that certain things are good, and others bad, not for their own sake but for the sake of something else to which they are related in some way. To say that these things are good and bad only in a derivative sense, that their value is merely parasitic on or reflective of the value of something else, is one thing; to deny that they are good or bad in any respectable sense is quite another. The former claim is accurate; hence the latter would appear unwarranted.

If we accept that talk of “extrinsic value” can be appropriate, however, a second question then arises: what sort of relation must obtain between A and Z if A is to be said to be good “because of” Z ? It is not clear just what the answer to this question is. Philosophers have tended to focus on just one particular causal relation, the means-end relation. This is the relation at issue in the example given earlier: helping others is a means to their needs being satisfied, which is itself a means to their experiencing pleasure. The term most often used to refer to this type of extrinsic value is “instrumental value,” although there is some dispute as to just how this term is to be employed. (Remember also, from Section 3 above, that on some views “instrumental value” may refer to a type of intrinsic , or final, value.) Suppose that A is a means to Z , and that Z is intrinsically good. Should we therefore say that A is instrumentally good? What if A has another consequence, Y , and this consequence is intrinsically bad? What, especially, if the intrinsic badness of Y is greater than the intrinsic goodness of Z ? Some would say that in such a case A is both instrumentally good (because of Z ) and instrumentally bad (because of Y ). Others would say that it is correct to say that A is instrumentally good only if all of A ’s causal consequences that have intrinsic value are, taken as a whole, intrinsically good. Still others would say that whether something is instrumentally good depends not only on what it causes to happen but also on what it prevents from happening (cf. Bradley 1998). For example, if pain is intrinsically bad, and taking an aspirin puts a stop to your pain but causes nothing of any positive intrinsic value, some would say that taking the aspirin is instrumentally good despite its having no intrinsically good consequences.

Many philosophers write as if instrumental value is the only type of extrinsic value, but that is a mistake. Suppose, for instance, that the results of a certain medical test indicate that the patient is in good health, and suppose that this patient’s having good health is intrinsically good. Then we may well want to say that the results are themselves (extrinsically) good. But notice that the results are of course not a means to good health; they are simply indicative of it. Or suppose that making your home available to a struggling artist while you spend a year abroad provides him with an opportunity he would otherwise not have to create some masterpieces, and suppose that either the process or the product of this creation would be intrinsically good. Then we may well want to say that your making your home available to him is (extrinsically) good because of the opportunity it provides him, even if he goes on to squander the opportunity and nothing good comes of it. Or suppose that someone’s appreciating the beauty of the Mona Lisa would be intrinsically good. Then we may well want to say that the painting itself has value in light of this fact, a kind of value that some have called “inherent value” (Lewis 1946, p. 391; cf. Frankena 1973, p. 82). (“ Inherent value” may not be the most suitable term to use here, since it may well suggest intrinsic value, whereas the sort of value at issue is supposed to be a type of extrinsic value. The value attributed to the painting is one that it is said to have in virtue of its relation to something else that would supposedly be intrinsically good if it occurred, namely, the appreciation of its beauty.) Many other instances could be given of cases in which we are inclined to call something good in virtue of its relation to something else that is or would be intrinsically good, even though the relation in question is not a means-end relation.

One final point. It is sometimes said that there can be no extrinsic value without intrinsic value. This thesis admits of several interpretations. First, it might mean that nothing can occur that is extrinsically good unless something else occurs that is intrinsically good, and that nothing can occur that is extrinsically bad unless something else occurs that is intrinsically bad. Second, it might mean that nothing can occur that is either extrinsically good or extrinsically bad unless something else occurs that is either intrinsically good or intrinsically bad. On both these interpretations, the thesis is dubious. Suppose that no one ever appreciates the beauty of Leonardo’s masterpiece, and that nothing else that is intrinsically either good or bad ever occurs; still his painting may be said to be inherently good. Or suppose that the aspirin prevents your pain from even starting, and hence inhibits the occurrence of something intrinsically bad, but nothing else that is intrinsically either good or bad ever occurs; still your taking the aspirin may be said to be instrumentally good. On a third interpretation, however, the thesis might be true. That interpretation is this: nothing can occur that is either extrinsically good or extrinsically neutral or extrinsically bad unless something else occurs that is either intrinsically good or intrinsically neutral or intrinsically bad. This would be trivially true if, as some maintain, the nonoccurrence of something intrinsically either good or bad entails the occurrence of something intrinsically neutral. But even if the thesis should turn out to be false on this third interpretation, too, it would nonetheless seem to be true on a fourth interpretation, according to which the concept of extrinsic value, in all its varieties, is to be understood in terms of the concept of intrinsic value.

Note: Numbers in square brackets indicate to which of the above sections the following works are especially relevant.

- Almotahari, Mahrad and Hosein, Adam, 2015, “Is Anything Just Plain Good?”, Philosophical Studies , 172: 1485–1508. [3]

- Anderson, Elizabeth, 1993, Value in Ethics and Economics , Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. [2, 3, 4]

- Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics (several editions). [1]

- Ayer, A. J., 1946, Language, Truth, and Logic , second edition, London: Victor Gollancz. [3]

- Beardsley, Monroe C., 1965, “Intrinsic Value”, Philosophy and Phenomenological Research , 26: 1–17. [3, 4]

- Bentham, Jeremy, 1789, An Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation (several editions). [1]

- Berlin, Isaiah, 1969, Four Essays on Liberty , Oxford: Oxford University Press. [1, 5]

- Blackburn, Simon, 1984, Spreading the Word , Oxford: Oxford University Press. [3]

- Blanshard, Brand, 1961, Reason and Goodness , London: Allen and Unwin. [2]

- Bodanszky, Eva and Conee, Earl, 1981, “Isolating Intrinsic Value”, Analysis , 41: 51–53. [2]

- Bradley, Ben, 1998, “Extrinsic Value”, Philosophical Studies , 91: 109–26. [6]

- –––, 2006, “Two Concepts of Intrinsic Value”, Ethical Theory and Moral Practice , 9: 111–30. [2]

- Brentano, Franz, 1969 (originally published in 1889), The Origin of Our Knowledge of Right and Wrong , London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. [1, 2, 5]

- Broad, C. D., 1930, Five Types of Ethical Theory , London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner. [2, 5]

- –––, 1985 (originally presented as lectures in 1952–53), Ethics , Dordrecht: Martinus Nijhoff. [2, 5]

- Butchvarov, Panayot, 1989, Skepticism in Ethics , Indianapolis: Indiana University Press. [1, 3, 4]

- Bykvist, Krister, 2009, “No Good Fit: Why the Fitting Attitude Analysis of Value Fails”, Mind , 118: 1–30. [2]

- Carlson, Erik, 1997, “The Intrinsic Value of Non-Basic States of Affairs” Philosophical Studies , 85: 95–107. [5]

- Chang, Ruth, 1997, “Introduction”, in Incommensurability, Incomparability, and Practical Reason , Ruth Chang (ed.), Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press. [5]

- –––, 2002, “The Possibility of Parity”, Ethics , 112: 659–88. [5]

- Chisholm, Roderick, 1968–69, “The Defeat of Good and Evil”, Proceedings and Addresses of the American Philosophical Association , 42: 21–38. [5]

- –––, 1972, “Objectives and Intrinsic Value”, in Jenseits von Sein und Nichtsein , R. Haller (ed.), Graz: Akademische Druck- und Verlagsanstalt. [4]

- –––, 1975, “The Intrinsic Value in Disjunctive States of Affairs”, Noûs , 9: 295–308. [4, 5]

- –––, 1978, “Intrinsic Value”, in Values and Morals , A. I. Goldman and J. Kim (ed.), Dordrecht: D. Reidel. [2, 4]

- –––, 1981, “Defining Intrinsic Value”, Analysis , 41: 99–100. [2, 4]

- –––, 1986, Brentano and Intrinsic Value , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [1, 2, 4, 5]

- Conee, Earl, 1982, “Instrumental Value without Intrinsic Value?”, Philosophia , 11: 345–59. [3, 6]

- Dancy, Jonathan, 2000, “The Particularist’s Progress”, in Moral Particularism , Brad Hooker and Margaret Little (ed.), Oxford: Clarendon Press. [5]

- Dewey, John, 1922, Human Nature and Conduct , New York: H. Holt. [3]

- Epicurus, 1926, Letter to Menoeceus , in Epicurus: The Extant Remains , Oxford: Oxford University Press. [1]

- Ewing, A. C., 1948, The Definition of Good , New York: Macmillan. [2]

- Feldman, Fred, 1997, Utilitarianism, Hedonism, and Desert , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [1, 4, 5, 6]

- –––, 2000, “Basic Intrinsic Value”, Philosophical Studies , 99: 319–46. [4, 5]

- Foot, Philippa, 1985, “Utilitarianism and the Virtues”, Mind , 94: 196–209. [3]

- Frankena, William K., 1973, Ethics , second edition, Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. [1, 6]

- Geach, Peter, 1956, “Good and Evil”, Analysis , 17: 33–42. [3]

- Gibbard, Allan, 1990, Wise Choices, Apt Feelings , Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press. [3]

- Hägerström, Axel, 1953, Inquiries into the Nature of Law and Morals , Uppsala: Uppsala University Press. [3]

- Hare, Richard M., 1952, The Language of Morals , Oxford: Oxford University Press. [3]

- Harman, Gilbert, 1967, “Toward a Theory of Intrinsic Value”, Journal of Philosophy , 64: 792–804. [5]

- Hobbes, Thomas, 1651, Leviathan (several editions). [3]

- Hume, David, 1739, A Treatise of Human Nature (several editions). [3]

- Hurka, Thomas, 1998, “Two Kinds of Organic Unity”, Journal of Ethics , 2: 299–320. [5]

- Kagan, Shelly, 1998, “Rethinking Intrinsic Value”, Journal of Ethics , 2: 277–97. [3, 4]

- Kant, Immanuel, 1785, Groundwork of the Metaphysic of Morals (several editions). [2]

- –––, Lectures in Ethics (notes taken by some of Kant’s students in the latter half of the eighteenth century; several editions). [2]

- Korsgaard, Christine, 1983, “Two Distinctions in Goodness”, Philosophical Review , 92: 169–95. [3, 4]

- Lemos, Noah, 1994, Intrinsic Value , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [1, 2, 4, 5]

- –––, 1998, “Organic Unities”, Journal of Ethics , 2: 321–37. [5]

- Lewis, Clarence I., 1946, An Analysis of Knowledge and Valuation , La Salle: Open Court. [2, 6]