- Healthy Relationships

- Signs of a healthy relationship

- Warning signs of an unhealthy relationship

- Domestic, family and sexual violence

- Sexual violence

- Domestic and family violence

- Children and young people

- Financial abuse

- Image-based abuse

- Legal abuse

- Physical abuse

- Psychological abuse

- Reproductive abuse

- Social abuse

- Spiritual abuse

- Stalking and monitoring

- Support and resources

- Mental health

- Paid family and domestic violence leave

- Promoting 1800RESPECT

- Safety apps for your digital devices

- Safety planning

- Supporting someone

- Technology and safety

- Using violence

- Violence and the law

- For professionals

- All past webinars

- Case studies and articles

- Inclusive practice

- Introduction to responding

- Leadership and management

- Resources and tools

- Training and professional development

- Work-induced stress and trauma

- Find Services

- About the 1800RESPECT Service Directory

- Services overview

- Contacting 1800RESPECT - what to expect

- Request for Information

- General and media enquiries

- Complaints, compliments and general feedback

Ano ang seksuwal na panghahalay (sexual assault)?

Ang pag-unawa sa seksuwal na panghahalay ay makakatulong sa aming tumugon.

Ang iyong mga karapatan at opsiyon makalipas ang isang pag-atakeng sekswal

1800RESPECT

Ang seksuwal na panghahalay ay anumang seksuwal o ginawang seksuwal (sexualized) na kilos na magreresulta upang ang isang tao ay makaramdam na hindi siya komportable, nasisindak o natatakot siya. Ito ay isang kilos na hindi inakit o pinili ng isang tao.

Ang seksuwal na panghahalay ay isang pagkakanulo ng tiwala at pagkakaila sa karapatan na mayroon ang bawat tao upang magpasiya tungkol sa kung ano ang mangyayari sa kanyang katawan. Ang seksuwal na panghahalay ay isang pang-aabuso ng karapatan at kapangyarihan.

Ang seksuwal na panghahalay ay maaaring isagawa sa mga taong nasa wastong gulang at mga bata, babae, at lalaki, at mga taong iba't iba ang pinaggagalingan.

Ang seksuwal na panghahalay ay maaari ring tawagin bilang seksuwal na pang-aabuso o seksuwal na karahasan. Ang mga salitang ginagamit upang ilarawan ang seksuwal na panghahalay, kagaya ng panggagahasa at seksuwal na pang-aabuso, ay parehong may pangkalahatang kahulugan kapag ginagamit sa pang-araw-araw na pag-uusap at isang partikular na kahulugan kapag ginagamit upang ilarawan ang partikular na mga kriminal na seksuwal na pagkakasala (criminal sexual offense). Sa website na ito, ginagamit namin ang mga salita sa pangkalahatang paraan at upang magbigay ng pangkalahatang impormasyon lamang.

Kung sa tingin mo na ginawa ang isang kriminal na seksuwal na pagkakasala at gusto mong magreklamo, maaaring naisin mong humiling ng karagdagang payo. Magagawa mo ito sa pamamagitan ng pagkontak sa serbisyo para sa seksuwal na panghahalay sa iyong lugar [sa Ingles] , sa pulis, iyong doktor o isang pribadong abogado. Maaaring isang salik (factor) ang oras at ang mga serbisyong ito ay makakapagbigay ng impormasyon tungkol sa mga karapatan at mga opsiyon.

Nangyayari ang seksuwal na panghahalay sa maraming anyo

Ang pag-unawa kung ano ang seksuwal na panghahalay ay tumutulong sa amin upang tumugon kapag binunyag ng isang kaibigan, miyembro ng pamilya o kliyente na sila ay hinalay. Ang sumusunod na listahan ay ilang mga halimbawa ng seksuwal na panghahalay:

Seksuwal na panliligalig.

Hindi gustong paghipo o paghalik.

Pinuwersa o pinilit na mga seksuwal na aktibidad o mga aktibidad na kaugnay sa pagtatalik, kabilang ang mga aktibidad na nagsasangkot ng karahasan o pananakit.

Paglalantad ng mga ari katulad ng 'flashing'.

Paniniktik (stalking)

Pinapanood ng isang tao na wala ang iyong pahintulot kapag ikaw ay nakahubad o nagsasagawa ng mga seksuwal na aktibidad.

Ang pagpapaskil ng mga seksuwal na imahe sa Internet nang wala ang iyong pagsang-ayon.

Pinuwersa o pinilit ng isang tao na manood o sumali sa pornograpiya.

Pag-spike ng mga inumin, o paggamit ng mga droga o alkohol, upang mabawasan o pahinain ang kakayahan ng isang tao na gumawa ng mga pagpipilian tungkol sa pakikipagtalik o seksuwal na aktibidad.

Pakikipagtalik sa isang taong tulog, o labis na apektado ng alkohol at/o iba pang mga gamot.

Malaswa o nagpapahiwatig ng kahalayang mga biro, kuwento o pagpapakita ng mga ginawang seksuwal na mga litrato, bilang bahagi ng isang pattern ng namimilit, nananakot o mapagsamantalang pag-uugali.

Panggagahasa (ang pagtagos ng anumang butas gamit ang anumang bagay)

Ang 'pag-groom" ng isang bata o taong mahina upang makisali sa mga seksuwal na aktibidad ng anumang uri.

Anumang seksuwal na kilos kasama ng isang bata.

Ang seksuwal na panghahalay ay hindi pareho ng seksuwal na pagpapahayag. Ang seksuwal na panghahalay ay isang hindi gustong mga seksuwal na pag-uugali o kilos na gumagamit ng pananakot, pamimilit, o puwersa upang gamitin ang kapangyarihan o ipagkaila ang karapatan ng isang tao upang pumili. Ang seksuwal na panghahalay o pang-aabuso ay maaaring isang beses na pangyayari, o bahagi ng isang pattern ng karahasan. Ito ay may isang hanay ng mga epekto, kabilang ang pisikal, emosyonal at sikolohikal na mga epekto.

Mga katotohanan tungkol sa seksuwal na panghahalay

Naririto ang ilang mahalagang bagay na dapat malaman tungkol sa seksuwal na panghahalay:

Karamihan sa mga seksuwal na panghahalay ay isinasagawa ng mga lalaki laban sa mga babae at mga bata.

Nakakaranas rin ang mga lalaki ng seksuwal na panghahalay; na karamihang isinasagawa ng iba pang mga lalaki.

Karamihan sa mga taong nakakaranas ng seksuwal na panghahalay ay kilala, o nakilala kamakailan lang, ang tagagawa ng panghahalay.

Ang ilang mga kilos ng seksuwal na panghahalay ay mga kriminal na pagkakasala (criminal offense) rin.

Ang pag-ulat sa pulis ay maaaring isang mahirap na desisyon. Ang mga limitasyon ng ating sistema ng hustisya, at ang paraan kung paano kinokolekta ang ebidensiya ay maaaring nakakatakot harapin.

Ang reaksiyon ng mga taong nakakaranas ng seksuwal na panghahalay ay maaaring iba-iba, paminsan-minsan mayroon silang matinding emosyon, paminsan-minsan umuurong sila. Ang pag-unawa sa trauma ng karahasan sa pagitan ng mga tao ay makakatulong sa ating tumugon sa angkop sa paraan.

Ang seksuwal na panghahalay ay isang pang-aabuso ng mga kawalan ng balanse ng kapangyarihan na umiiral sa lipunan.

- Karamihan sa mga seksuwal na panghahalay ay hindi iniuulat sa pulis.

Ang mga epekto ng seksuwal na panghahalay

Ang karahasan sa pagitan ng mga tao, katulad ng seksuwal na panghahalay, ay kabilang sa pinakatraumatikong pangyayari na mararanasan ng isang tao. Ang pagtugon sa mga agarang pangangailangan ng biktima/nakaligtas sa pamamagitan ng paniniwala sa kanila at pagtrato nito nang seryoso, ay makakatulong upang mabawasan ang karagdagang pinsala. Ang pagpapatuloy sa pagsuporta sa mga tao habang gumagaling sila ay napakamahalaga rin, at mahalagang gawin ito sa sarili nilang paraan at sa sarili nilang panahon.

Kung gusto mo ng karagdagang impormasyon sa pagsuporta sa biktima/nakaligtas, tingnan ang pahina ng Paano susuportahan ang isang taong nakaranas ng seksuwal na panghahalay .

Paano ko susuportahan ang isang taong nakakaranas ng seksuwal na panghahalay?

Karaniwan ang seksuwal na panghahalay – humigit-kumulang isa sa limang babae ay makakaranas ng seksuwal na panghahalay. May mga praktikal na bagay na magagawa mo upang makatulong.

Developed with: Victorian Centres Against Sexual Assault

- News and media

Funded by the Australian Government Department of Social Services (DSS). © 2024 Australian Government or Telstra Health Pty Ltd

- Edukasyon's Guide To

- Extracurriculars

- Career Conversations

- Productivity Hacks

- Generation Zen

- Junior High School

- Senior High School

- Post-Graduate

- Study Abroad

- Online Events

- Explore Courses

- Search school

- Get Funding

Sexual Harassment and Violence Against Women and Girls: Bakit may ganito?

Sep 01, 2021

By : Created in Partnership with Tiffany Jalalon Sprague

“Sa Pilipinas, 1 sa 20 kababaihan edad 15-49 years old ang nakakaranas ng pang-aabusong sexual.” (2017 National Demographics and Health survey)

Ano ang sexual harassment at violence?

Ito ang hindi kanais-nais na pagkilos o pananalita sa isang sexual at malaswang paraan. Sa ganitong mga kaso, palaging may harasser na pinipilit o kino-coerce ang kanyang mga biktima upang makuha ang sariling sexual needs. Tinatanggal ng harasser ang karapatan ng biktima na magdesisyon para sa sarili niyang katawan.

Ilan sa mga halimbawa nito ang verbal harassment (tulad ng catcalling at wolf-whistling na madalas nangyayari sa mga kalye), rape o ang pag-penetrate sa sex organ ng isang tao nang walang consent o pahintulot, panghihipo o paghawak sa katawan ng ibang tao, at ang pagpapakita ng private parts sa ibang tao kahit na labag ito sa kanilang kagustuhan.

Sa bawat kwento ng sexual harassment at violence, hindi ginusto o hiningi ng biktima ang pang-aabusong nangyari sa kanya. Kahit na sino ay pwedeng makaranas nito, ngunit makikita sa mga datos na ang mga kababaihan at kabataan ang pinakananganganib na maging biktima.

Malaki ang epekto ng sexual harassment at violence sa mga taong nakakaranas nito.

Palagi nating naririnig na puno ng pasa at sugat ang katawan ng mga biktima, lalo na sa kanilang private parts. Ngunit hindi natin masyadong napapansin ang mga psychological na epekto nito, tulad ng pagkakaroon ng depression at pagpapakamatay. Mas malaki rin ang posibilidad na maadik sa droga, alak, at sigarilyo ang mga biktima dahil sa bigat ng trauma na kanilang nararanasan.

Pwede ring makita ang epekto nito sa pang-araw-araw na buhay at pagkilos ng mga biktima. Marami ang nahihirapang bumalik sa trabaho o paaralan upang mamuhay nang normal. Meron ding mga romantic at platonic relationships na nasisira dahil nawawalan ng tiwala ang mga biktima sa mga taong nasa paligid nila. At dahil na rin sa trauma na dala ng karanasang ito, marami ang nahihirapang bumuo ng magandang kinabukasan para sa kanilang sarili.

Madalas, kung sino pa ang malapit sa mga biktima , sila pa ang nang-ha-harass o nang-aabuso .

Pwedeng sila ay kaibigan, boyfriend/girlfriend, katrabaho, kapit-bahay, o kamag-anak ng biktima. Madalas ay hindi na-re-report ang ganitong klase ng harassment dahil sa takot at kahihiyan, o dahil hindi sila pinapaniwalaan ng ibang tao. Ito ang isang dahilan kung bakit hanggang ngayon maraming harasser pa rin ang malaya at maganda ang buhay.

Talagang matindi ang pangangailangan na mawala ang mga harasser at matigil ang krimen na ito, upang hindi na tayo mabuhay sa isang mundo na puno ng takot. Pero para mangyari ito, dapat alamin muna natin kung bakit nagiging harasser ang isang tao.

Bakit nga ba may mga sexual harasser ?

May tinatawag na “ risk factors ” o ang mga dahilan kung bakit lumalaki ang posibilidad na maging harasser ang isang tao. Ang halimbawa ng mga dahilang ito ay:

- Ang paggamit ng alak at droga;

- ang pagkilos sa agresibong paraan na nakakasakit sa ibang tao;

- ang exposure sa mga sexual na mensahe o media;

- ang hypermasculinity, o ang pagtanggap sa mga tradisyonal at toxic na paniniwala pagdating sa pagiging “tunay na lalaki”;

- pagkakaroon ng hindi magandang relasyon sa pamilya (lalo na sa ama);

- pag-te-take advantage o pagiging mapang-abusong kaibigan o kasintahan;

- pagiging apektado ng kahirapan at kawalan ng trabaho

- ang pagmamaliit ng mga lalaki sa kababaihan.

Kung mabibigyan ng solusyon ang risk factors na ito, pwede nating maiwasan ang pagkakaroon ng mga harasser at mabawasan ang mga biktima ng sexual harassment at violence.

Dapat nating tandaan na mawawala ang karahasan kung…

Mawawala ang karahasan kung habang maliit pa lamang, tinuturo na sa mga kabataan ang respeto, malasakit, permiso o consent mula sa ibang tao, at pagkakapantay-pantay . Kausapin natin ang mga bata habang maaga pa lamang para maintindihan na nila ang toxic na sistema sa lipunan at hindi na nila madala ito sa paglaki.

Mawawala ang karahasan kung walang gagamit ng sariling kapangyarihan upang manakit ng ibang tao. Hindi dapat ginagamit ang sariling estado o antas sa buhay upang maliitin at abusuhin ang ibang tao.

Mawawala ang karahasan kung pakikinggan natin ang boses ng mga nabiktima ng sexual violence, upang hindi na ito maulit muli. Kung patuloy na isasawalang-bahala ang kwento ng mga biktima, patuloy ring lalakas ang loob ng mga harasser.

Mawawala ang karahasan kung gagawa tayo ng mga safe space para sa mga kababaihan at kabataan . Sa physical o online man na espasyo, dapat mabigyan sila ng kapangyarihan na ibahagi ang kanilang mga iniisip o nararamdaman.

Mawawala ang karahasan kung epektibo at patas ang mga batas laban sa sexual violence. Sikapin dapat ng gobyerno at lawmakers na mailabas ang katotohanan at mabigyang hustisya at lunas ang mga biktima.

Mawawala ang karahasan kung magiging mabuting halimbawa tayo sa isa’t isa . Sa anumang sitwasyon, responsibilidad natin ang maging magandang impluwensya sa ating pamilya, kaibigan, at kapwa.

At higit sa lahat: mawawala ang karahasan kung walang mang-ha-harass, mananamantala, at manggagahasa.

Makikita natin na pagdating sa problema ng sexual violence, hindi lamang iisa ang solusyon o paraan upang mapigilan ang krimeng ito. Kinakailangan ng patuloy na pagtutulungan at pananagutan sa pagitan ng bawat tao, ng kanyang pamilya at komunidad, ng mga paaralan at opisina, at ng gobyerno para tuluyan nang maging ligtas ang ating kapaligiran.

Share this article

- #sexual-harrassment

- #sexual-violence

- #violence-against-women

Written By:

Related Stuff

How you’re using the internet vs. the positive alternative you could be doing.

Feb 13, 2024

Vax and Myths: The Truths and Misconceptions about Vaccination

Jan 30, 2024

TV and Me: How our changing bodies are portrayed in the media

Dec 07, 2023

The 6 Rules of Being Body Curious

Nov 30, 2023

Caring For Yourself as a Parenteen

Oct 06, 2023

Take care of your mental health

Students’ guide to flying with singapore airlines, how to ditch the mindless scroll and have fun on the internet instead, 5 things you can still do online even in your f2f learning, how to channel confidence this back-to-school season, which wellness reminder do you need today, 5 ways to deal with face-to-face classes anxiety, 3 ways you can do a wellness check-in, 5 ways to manifest wellness in your life, dear besties, why am i not feeling well today, 3 ways online learning has made us better students, 5 ways to positively use the internet in 2022.

No need to cram! This is the fun kind.

Learn and earn rewards along the way!

Planning for college? Don’t worry, we gotchu!

Let us help you achieve your dream job by matching you with the right schools.

Need more info?

- Pagkilala Sa Katawan

- Relationships

- Sekswalidad

- Contraception

- HIV at STIs

PAD-Ibig Diaries

- Educational Services

Ano Ang Sexual Harassment?

May maraming anyo ang sexual harassment at pwedeng mangyari ito sa maski anong lugar o sitwasyon, sa babae man o lalaki. Hindi lang panghihipo ang maituturing na sexual harassment. Kabilang din dito ang bullying na nakakasakit ng tao sa pamamagitan ng mga sekswal o malisyosong mga biro, komento, chismis, o kilos na tungkol o nakadirekta sa ibang tao.

Kung biktima ng sexual harassment, tandaan na hindi mo ito kasalanan. Ano pa man ang kilos o suot ng isang tao, hindi ‘yon imbitasyon para bastusin sa kahit anong paraan.

Kung nakakaranas ng sexual harassment, magsabi sa pinagkakatiwalaang kaibigan o pamilya, o kaya i-report sa awtoridad.

Narito ang isang video na hinanda namin para pag-usapan ang topic na ito.

Sa tulong ng the Australian and New Zealand Association (ANZA), mayroon na tayo ngayong mga libre at tamang impormasyon tungkol sa sexual at reproductive health — sa wikang mas pamilyar sa atin– sa pamamagitan ng mga Amaze.org videos na isinalin sa Tagalog!

——————

I-like, i-share, at mag-subscribe sa Ugat ng Kalusugan Youtube Channel para updated ka sa mga bagong videos: https://bit.ly/3ELvEcw

Share This Post

Related articles.

Ano ang Sexual Orientation?

Pakikipagkaibigan habang nasa teenage years

TULI: Nakakalaki, nakakalalaki, at iba pang sabi-sabi

Mga dapat mong malaman sa tuli

Pagkakakilanlan Sa Kasarian: Cis, Trans, O Fluid

Hindi sakit maging LGBTQIA+

Bullying: Paano Tumulong Sa Biktima Nito

Chismis o Check: Naipapasa ba ang HIV sa halik?

© 2021 Ugat ng Kalusugan - All Rights Reserved

- Subscribe To Our Listserv

- News and Events

Domestic and Sexual Violence in Filipino Communities, 2018

- Census data on demographics and English proficiency

- Statistics on domestic violence and other forms of abuse

- Resources such as links to translated materials and national/international service directories

- Lifetime Spiral of Gender Violence , in English and Tagalog

Related Resources

- Building AAPI Collective Power to End GBV

March 7, 8am HST/11am PST/1pm CST/2pm ESTAsians, Asian Americans, and Pacific Islanders (AAPIs) are often left out of conversations around diversity, equity, inclusion, and belonging (DEIB) in the U.S. Often lumped together as a “model minority,” certain AAPI groups...

- 2024 APi-GBV National Summit: Growing From Our Roots

Latest Update: Request for Proposal now available!See all available API-GBV National Summit information below:This page will continue to be updated as more information is released. For any technical issues or additional questions, please contact our team at...

- Connected and concerned: Online sexual harassment of teenagers of Asian descent on dating platforms

February 29, 8am HST/11am PST/1pm CST/2pm ESTGenerative AI, with its ability to create morphed photos and deepfakes, is negatively impacting teenagers, especially female teenagers of Asian descent, online and influencing their identity in digital spaces. This...

Impact Report FY22: Growing Stronger Together to Build Collective Power

The Asian Pacific Institute on Gender-Based Violence (API-GBV) is a culturally specific national resource center on domestic violence, sexual violence, trafficking, and other forms of gender-based violence in Asian/Asian-American and Pacific Islander (AAPI)...

Culture, Trauma, and Healing: A Conversation with Texas Muslim Women’s Foundation

November 7, 9am HST/12pm PST/2pm CST/3pm ESTIn our work, we recognize that cultural-responsiveness and trauma-informedness are not end goals, but a continuous process of learning and adapting our advocacy to best meet the layered and changing needs of survivors. We...

Queer and Trans Asians and Pacific Islanders: Strengths, Resources, and Barriers for Preventing Domestic Violence-Related Homicides

This report presents a groundbreaking qualitative research project focusing on the prevention of domestic violence-related homicides among queer and trans Asians and Pacific Islanders (QTAPI). It uncovers the complex web of risk factors, including isolation and...

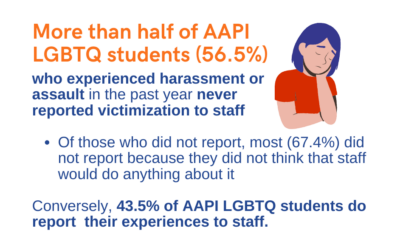

AAPI LGBTQ+ Experiences of GBV

This factsheet summarizes the layered needs and experiences of lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and more (LGBTQ+) Asian, Asian American, and Pacific Islander (AAPI) survivors and communities in the U.S., based on the current literature available. Although...

Directory of Domestic & Gender Violence Programs Serving Asians, Native Hawaiians and Pacific Islanders, 2023

Lists roughly 150 agencies in the U.S. that have culturally-specific programs designed for survivors from Asian and Pacific Islander communities.

Other Ethnic-Specific Factsheets

- Pacific Islander

- South Asian

Share this:

Search resource library, resource categories, resource tags, resource types, recent resources.

- Safeguard Asylum for Survivors – Tell Your Senator to Reject the Emergency National Security Supplemental Appropriations

- API-GBV’S CALL FOR A CEASEFIRE AND AN END TO THE LOSS OF INNOCENT LIVES

Plan International's websites

Find the Plan International website you are looking for in this list

bawal bastos: pilipino ay magalang

Join the movement to end gender-based sexual harassment and violence..

Browse through the campaign resources below and advocate for #SafeSpacesNow.

Recognising the role of media in the promotion of Safe Spaces for all, the ‘Bawal Bastos: Pilipino ay Magalang’ initiative by Plan International Philippines makes available various information, education and communication materials for organisations to promote and use on digital and traditional media platforms.

ABOUT THE CAMPAIGN

In 2019, the Philippines passed the Safe Spaces Act (SSA), a law that protects girls and young women from getting harassed in public spaces, in the workplace, in educational and training institutions, and online. Dubbed the “Bawal Bastos Law”, SSA defines gender-based sexual harassment (GBSH) in streets, public spaces, online, workplaces, and educational or training institutions.

Plan International Philippines aims to support and work with various partners to promote and protect the rights of women and children through an awareness campaign.

The ‘Bawal Bastos: Pilipino ay Magalang’ initiative aims to contribute to the localisation of the law through campaign materials designed for digital and traditional media. Organisations and individuals are encouraged to use these materials for dissemination in their respective channels to strengthen visibility and raise awareness for the Safe Spaces Act.

What is the Safe Spaces Act?

The Safe Spaces Act or the Bawal Bastos Law penalises all forms of gender-based sexual harassment in streets and public spaces, including workplaces and schools, as well as in online spaces.

The crimes of gender-based sexual harassment (GBSH) are committed through any unwanted and uninvited sexual actions or remarks against any person regardless of the motive.

Take action.

You can take a stand by:

- Empowering everyone against gender-based violence and sexual harassment,

- Campaigning for solidarity in making spaces safe for all people,

- Report incidents of gender-based violence and sexual harassment that you witness.

Everyone has the responsibility to respect the rights of other people. Everyone has a role to play in ending GBSH. Dahil lahat may magagawa, lahat makikinabang.

Downloadables.

Anyone can use the ‘Bawal Bastos: Pilipino ay Magalang’ materials. These materials should work to help raise awareness on what constitutes gender-based violence and sexual harassment and how to report or respond accordingly, by providing clear information on the available reporting mechanisms and support pathways. They can be used:

- On social media

- On visible spaces (i.e., public transport vehicles, communal areas, hallways, etc.)

- As handouts to employees, students, commuters, mall-goers, etc.

- As resources for webinars, trainings, and other capacity-building activities

partner with us

For inquiries on collaboration and other concerns about this program, you may reach out to:

Kassandra Barnes Communications Specialist, Plan International Philippines [email protected]

IF YOU ARE IN IMMEDIATE DANGER, CALL 911 OR CONTACT PNP HOTLINE AND WCPC: (632)8532 66 90 | ALENG PULIS HOTLINE: 0919 777 7377

Cookie preferences updated. Close

This popup will be triggered by a user clicking something on the page.

- Subscribe Now

The many faces of sexual harassment in PH

Already have Rappler+? Sign in to listen to groundbreaking journalism.

This is AI generated summarization, which may have errors. For context, always refer to the full article.

MANILA, Philippines – President-elect Rodrigo Duterte is under fire after wolf whistling at a reporter in a press conference on Tuesday, May 31, and defending it days after by saying that it was “not a sexual thing.”

A good number of netizens accept Duterte’s explanation that whistling at a woman is covered by freedom of expression. Others are certain that Duterte violated Davao City’s ordinance prohibiting catcalling women .

What constitutes sexual harassment? Where do you draw the line?

What is sexual harassment?

In Section 3, Republic Act 7877, or the Anti-Sexual Harassment Act of 1995, classifies sexual harassment as:

Work-related or in employment environment

This is committed when a person demands, requests, or requires sexual favors from another person in exchange for another thing such as hiring for employment, re-employment, or continued employment, granting favorable compensation, terms of conditions, promotions, or privileges.

Refusal to accept sexual favors would mean discrimination or deprivation of employment opportunities.

It is also sexual harassment if the sexual favors would result to abuse of rights under the labor law and and an environment that is intimidating, hostile, or offensive for the victim.

This may be committed by an “employer, employee, manager, supervisor, agent of the employer, any other person who, having authority, influence or moral ascendancy over another in a work environment, demands, requests or otherwise requires any sexual favor from the other.”

In education or training environment

This is committed when a person demands, requests, or requires sexual favors from a student in exchange for “giving a passing grade, or the granting of honors and scholarships, or the payment of a stipend, allowance or other benefits, privileges and considerations.”

Just the same, if the sexual favors would result to an “intimidating, hostile or offensive environment for the student, trainee, or apprentice,” they are also considered sexual harassment.

This may be committed by a “teacher, instructor, professor, coach, trainor, or any other person who, having authority, influence, or moral ascendancy over another…demands, requests, or otherwise requires any sexual favor from the other.”

Under the Civil Service Commission Resolution Number 01-0940 , a set of administrative rules for government employees, forms of sexual harassment include:

- malicious touching

- overt sexual advances

- gestures with lewd insinuation

- requests or demands for sexual favors, and lurid remarks

- use of objects, pictures or graphics, letters or writing notes with sexual underpinnings

- other forms analogous to the ones mentioned

Meanwhile, the Women’s Development Code of Davao City, which Duterte himself signed as mayor, aims to protect the rights of women by punishing those who committ sexual harassment, among other things.

Under Section 3 of the ordinance, “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, or other verbal or physical behavior of a sexual nature, made directly, indirectly or impliedly” can be considered sexual harassment.

The following are considered forms of sexual harassment:

- persistent telling of offensive jokes, such as green jokes or other analogous statements to someone who finds them offensive or humiliating

- taunting a person with constant talk about sex and sexual innuendos

- displaying offensive or lewd pictures and publications in the workplace

- interrogating someone about sexual activities or private life during interviews for employment, scholarship grant, or any lawful activity applied for

- making offensive hand or body gestures at someone

- repeatedly asking for dates despite verbal rejection

- staring or leering maliciously

- touching, pinching, or brushing up against someone’s body unnecessarily or deliberately

- kissing or embracing someone against her will

- requesting sexual favors in exchange for a good grade, obtaining a good job or promotion, etc

- cursing, whistling, or calling a woman in public with words having dirty connotations or implications which tend to ridicule, humiliate or embarrass the woman such as “puta” (prostitute), “boring,” “peste” (pest), etc

- any other unnecessary acts during physical examinations

- requiring women to wear suggestive or provocative attire during interviews for job hiring, promotion, and admission

Street harassment is among the most common forms of sexual harassment. (READ: The streets that haunt Filipino women )

Sexual harassment in public spaces: “Unwanted comments, gestures, and actions forced on a stranger in a public place without their consent and is directed at them because of their actual or perceived sex, gender, gender expression, or sexual orientation.” – Stop Street Harassment Organization

Street harassment can happen in public places, such as in and around public transportation, public washrooms, church, internet shops, parks, stores and malls, school grounds, terminals, and waiting sheds.

According to the Philippine Statistics Authority , sexual harassment may happen in the following:

- premises of the workplace or office or of the school or training institution

- any place where the parties are found, as a result of work or education or training responsibilities or relations

- work- or education- or training-related social functions

- while on official business outside the office or school or training institution or during work- or school- or training-related travel

- at official conferences, fora, symposia, or training sessions

- by telephone, cellular phone, fax machine, or electronic mail

Women are most vulnerable

The Anti-Violence Against Women and Their Children Act , also known as Republic Act 9262, also considers sexual harassment as a form of violence against women.

Section 3 of the law says that sexual violence refers to “rape, sexual harassment, acts of lasciviousness, treating a woman or her child as a sex object, making demeaning and sexually suggestive remarks.”

A 2016 study conducted by the Social Weather Stations found that women are most vulnerable to sexual harassment.

In Quezon City, Metro Manila’s biggest city with a population of over 3 million, 3 in 5 women were sexually harassed at least once in their lifetime, according to the report. In barangays Payatas and Bagong Silangan, 88% of respondents ages 18 to 24 experienced street harassment at least once.

Across all ages, 12 to 55 and above, wolf whistling and catcalling are the most experienced cases. (READ: ‘Hi, sexy!’ is not a compliment )

Quezon City is the first city in Metro Manila to impose penalties on street harassment.

In the Philippines, 58% of incidents of sexual harassment happen on the streets, major roads, and eskinitas (alleys). Physical forms of sexual harassment occur mostly in public transport.

Sexual harassment can be punished under Republic Act 7877, or the Anti-Sexual Harassment Act of 1995, and the provisions of the Revised Penal Code on Acts of Lasciviousness.

RA 7877 penalizes sexual harassment with imprisonment of 1 to 6 months, a fine of P10,000 to P20,000, or both. Acts of lasciviousness, on the other hand, would mean imprisonment under the Revised Penal Code. – Rappler.com

Add a comment

Please abide by Rappler's commenting guidelines .

There are no comments yet. Add your comment to start the conversation.

How does this make you feel?

Related Topics

Recommended stories, {{ item.sitename }}, {{ item.title }}.

Checking your Rappler+ subscription...

Upgrade to Rappler+ for exclusive content and unlimited access.

Why is it important to subscribe? Learn more

You are subscribed to Rappler+

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Victim Blaming Culture in the Philippines: A Hindering Factor to the Unresolved Battles of Sexual Abused Individuals

Sexual Abused victim-survivors are often met with a barrage of questions after coming forward. Famously, “what were you wearing?” is one of them (Ramos, 2021). Many of the Sexual Abused Victims were afraid of coming forward as they fear of being re-victimized by the Victim Blaming Culture. Through this study, the researchers explore the experiences and struggles of sexually abused individuals towards the victim blaming culture to determine the assumption of the researchers that the victim blaming culture is one factor in the unresolved battles of Sexual Abused Individuals. The researchers used qualitative research with open-ended questions through Google Form as the main instrument to gather data from five chosen informants around the Philippines. Within the study, there were three research questions formed. The first problem is to determine how the Victim Blaming Culture manifests in the lives of Filipino people. The second problem was how Victim Blaming Culture hampers the progress of the Sexual Abuse cases in the Philippines. The last problem aimed to know the deep emotions and mental struggles the Victims of Sexual Abuse have encountered after becoming a victim of Victim Blaming. The researchers have made use of coding to interpret the statements of the informants. Results show that victim blaming culture is a hindering factor to the unresolved battles of Sexual Abuse Victims. It made them build a social barrier to distance themselves from society and undergo mental struggles. With this said, it was recommended for the Government to exert efforts to solve this issue to prevent victims from encountering victim blaming culture. Keywords: Victim Blaming Culture, Sexual Abuse, Social Barrier, Mental Struggles

Related Papers

Karen Quing

Correspondence *Corresponding Author. Email: [email protected] Abstract Sexual violence is a catastrophic phenomenon that most women encounter worldwide. However, the stigma surrounding the victims of sexual violence often leads to a culture of silence, causing the number of such cases to be underreported, leading to limited sexual violence-related studies. With this, the goal of this study is to contribute additional information on the experiences of Filipino victims with sexual violence, its impacts, and their coping mechanisms. Ten Filipino women, who were victims of sexual violence, were interviewed in this study. Thematic analysis was used to analyze the gathered data. Themes on their experiences, the effects of sexual violence, and their coping mechanisms were formulated and presented in this study. The study showed that the most common type of sexual violence experienced by the participants was rape. They also reported feelings of fear during and after the abuse. Feelings of...

University of Birmingham

Dr Jessica Taylor

Victim blaming and self-blame are common experiences for women who have been subjected to sexual violence (Gravelin, Beirnat & Bucher, 2019). This thesis employs a comprehensive mixed-methods approach from a critical realist feminist epistemology. Chapter one introduces victim blaming and self-blame of women, including rationale for the language and terminology used in this thesis. Chapter two presents a review of the literature of victim blaming of women and chapter three sets out the methodology of the thesis. Chapter four presents the exploration and initial development of a new measure of victim Blaming of Women Subjected to Sexual Violence and Abuse (BOWSVA Scale). Chapter five and six present two qualitative studies exploring the language used to construct the victim blaming and self-blame of women, the first study from the perspective of women subjected to sexual violence and the second from the perspective of professionals who work in sexual violence support. The three studies result in a final discussion proposing a new integrated model of victim blaming of women and further findings about the victim blaming of women in society, self-blame of women after sexual violence and the way language constructs the blame of women.

Proceedings of the Asia-Pacific Research in Social Sciences and Humanities Universitas Indonesia Conference (APRISH 2019)

Prof. Billy Sarwono

MD GOLAM AZAM

Rape is being alarming condition in Bangladesh day by day. It is the most common and vicious form of violence against woman in Bangladesh. Rape culture and the practice of victim blaming are inherently linked phenomena, the existence of a rape culture which normalizes sexual violence and blames rape victims for the attacks against them create cultural violence in Bangladesh. Along with the trauma experienced by rape victims due to their assault, many victims also suffer secondary victimization due to the negative reactions of those around them. Among these negative reactions, perhaps the most damaging is the tendency to blame victims for their assault, particularly in cases of acquaintance rape. The current research explores the role of rape culture coverage in promoting a victim blaming culture in the Bangladesh. In Study, I review the literature related to rape and rape culture in order to identify factors and influences contributing to rape-supportive beliefs and behaviors in society at large, including the ways in which women’s lives are impacted by the constant threat of rape and how male socialization contributes to and normalizes this threat. Then I try to explore about factors of rape culture in Bangladesh society based on discourse and content analyses of online comments on report related to rape and rape cultures. The study also emphasis on victim of the rape, blaming the victims, denial of gender aspects violence, denial of rape culture, anti- feminism etc. In Study, I demonstrated that people’s victim blaming tendencies by analysis of comments on social media. Specifically, following exposure to rape related news, participants were more likely to blame the victim of an unrelated case of sexual assault, and to endorse rape myths. The findings of this research demonstrate public perception of rape victims, particularly victims of acquaintance rape. In this study, I also demonstrated about the relation between rape culture and cultural violence. I try to prove here existing rape culture contribute in cultural violence by the increase of sexual assaults, victim blaming, dehumanization of women.

Rajagiri Journal of Social Sciences

Simply because she is a female the average Indian woman is likely to be variously a victim of feticide, infanticide, malnourishment, dowry, child marriage, maternal mortality, domestic servitude, prostitution, rape, honor killings and/or domestic violence. The stereo types of perception for the rape victims which are highly prevalent in a society like India prevent the rehabilitation of the victim back into society. Social workers are a part of the multidisciplinary team which works in a scenario both to prevent instances of rape and at the same time is responsible for the effective rehabilitation of the victims back into society. However, the prejudiced mindset of the social worker will affect the rehab services which are being provided to the victims and also to the perpetrators. It hence becomes mandatory to analyse social life to understand the prevalence of rape myth acceptance and victim blaming attitudes which are prevalent among social workers. This study compares the prevalence of rape myth acceptance and victim-blaming attitudes among male and female social work trainees. It was revealed that the female respondents have a slightly more negative attitude towards the victims as compared to the male respondents. The fact however remains that both male and female respondents were victim blaming and had rape myth acceptance attitudes. This in turn points to the prevalence of poor quality professional social services which adversely affect the rehabilitation of the rape victims.

Anuradha Parasar

Millennium Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN: 2708-8022 (ONLINE) 2708-8014 (PRINT)

Gender discrimination against women is a prevalent issue in Bangladesh, but sometimes it is concealed. Rape cases, also known as-sexual abuse‖ in many cultures, are a special insidious type of sexual harassment. In other contexts, when you are familiarizing with the lifestyle of women, as a social worker it is likely to see victims of sexual abuse due to a large number of abusive offenders. Global WHO figures suggest that about 1 in 3 (35%) of women around the world endure physical and sexually intimate relationships or non-partner sexual abuse during their lives. Domestic abuse is the most heinous form of violence. Approximately one third (30%) of all women who have a relationship comment on physical and sexual harassment witnessed by their intimate partner nationwide. This review investigates several peer-reviewed journals and articles that have been developed for the comprehensive understanding of domestic abuse as rape. Still, this issue of rape must be addressed within and outside the scope of domestic violence. More experiments are conducted with a focus for future studies. The major argument of this review is that while raped women are suffering from the permanent effects of psychological and emotional damage, the issue of rape is not the problem of women. It is squarely a man's problem. As a society, victim allegation is preached as a flame, but the issue is with ancestors and older generations' minds and opinions. On a conclusive note, strategies for rape prevention have been discussed. It is crucial to recognize and increasingly teach young children about the effects of sexual harassment and how traditions can be changed to avoid social stigma.

Istanbul University - DergiPark

Tutut Chusniyah

Natti Ronel , Prof. Jaishankar Karupannan , Moshe Bensimon

The following chapters are grouped in three sections: Justice for victims, issues of sexual victimization, and illustrated examples of victimization. The first section targets perception and the process of change in perception as they affect victimology and justice for victims. In Chapter One, Noach Milgram postulated that ideology is inherent in perception and critical in understanding the mind set of victims. Ideology, whether manifest or below awareness, contributes to the construction of perceptions and proactive and reactive behavior. Noach provides innovative and provocative illustrations of the power of ideology in his studies on battered women and victims of Palestinian terrorism. Uri Timor proposes in Chapter Two a different view by challenging the perceptions that underlie etributive punishment. Uri presents an alternative solution to the conflict between offender and victim that is based on Jewish theoretical formulations and restorative approaches. He advocates transferring at least partial responsibility for the offender-victim conflict to the prevailing social order; this recommendation is consistent with Jewish tradition attributing to the community some degree of responsibility for the transgressions that take place within its confines. Esther Shachaf-Friedman and Uri Timor present in Chapter Three, findings from a study of victims’ perceptions in family–group conferences with juvenile delinquents. Based on the analysis of these perceptions, Esthi and Uri suggest practical guidelines to prepare and implement restorative justice processes in victim-focused intervention. The same pragmatic victim-needs and rights approach was presented by Sharon Aharoni-Goldenberg and Yael Wilchek-Aviad in Chapter Four on restitution to victims of property offences. Victim-focused restitution is contrasted with the prevalent legal procedures applied to property offenders that do not help the direct victims, according to Sharon and Yael. In the fifth and final chapter in this section, K. Jaishankar, P. Madhava Soma Sundaram and Debarati Halder describe and discuss the position of the victim in ancient, medieval, British and modern India; the authors analyze the role of Malimath Committee in restoring the forgotten voices of crime victims in the Indian criminal justice system. Jai, Madhavan and Debarati illustrate the process of change that a developing society goes through when attempting to adopt the thought of modern victimology, and at the same time, to integrate it with ancient Indian wisdom. Sexual harm and offences usually leave distinctive mark on individuals who were sexually victimized. The sexual violation of intrapersonal intimacy calls for particular understanding and intervention. The second section addresses this issue specifically. Yifat Bitton offers in Chapter Six a feminist perception of the treatment of women victims of sexual violence in the justice system that is needed to prevent further victimization and to overcome the consequences of the initial victimization. Yifat calls for reorientation of tort litigation to enable women victims of sexual violence to reclaim the power that was brutally taken from them. Hadar Dancig-Rosenberg highlights the gap between therapeutic dialogue and legal dialogue in Chapter Seven and calls for accommodating existing judicial processes to the unique needs of sexual assault victims. Hadar suggests that while the adversarial system of judicial procedures is likely to remain, it must undergo reforms that will advance therapeutic goals in behalf of the victims. Inna Levy and Sarah Ben-David broadens in Chapter Eight the discussion on sexual victimization by focusing on a neglected group, the “innocent” bystanders. Reviewing theoretical and empirical literature, Inna and Sarah address the way bystanders are perceived and offer models of bystander blaming. In Chapter Nine, P. Madhava Soma Sundaram, K. Jaishankar and Megha Desai address sexual harassment in the modern work places in India. In their empirical pilot research, Madhavan, Jai and Megha describe the prevalence and characteristics of sexual harassment in a major Indian city, Mumbai. In the final chapter of this section, Chapter Ten, Sarah Ben-David and Ili Goldberg present the results of a study of male prisoners. Their study establishes the relationship of past traumatizing experiences in sexual offenders, their PTSD symptoms and drug dependency, and their own perpetration of sexual crimes. Sarah and Ili found that prisoners who were sexually abused in the past and who developed a cognitive avoidance style tended to become sexual offenders as adults, while those who developed drug dependency tend to exhibit non-specific criminal behavior. The third section of the book illustrates and analyses several examples of victimization. In an empirical research design, Avital Laufer and Mally Shechory investigated in Chapter Eleven distress levels in Israeli youth, 18 months after they were forced to leave their homes during the Israeli government mandated disengagement from the Gaza Strip. Avital and Mally found direct relationships between perception of the traumatic experience, feelings of alienation, and distress level. In Chapter Twelve, Nandini Rai presents a novel focus on known phenomena. She offers a socio-geographical analysis of the distribution of criminal victimization from the perspective of places with specific identities. Nandini asserts that reduced social interaction and a decline in mutual trust in the society make the places of interaction unsafe. In Chapter Thirteen, Ehud Bodner reviews the major factors in the etiology of suicide among soldiers and in the failure of professional authorities to provide help to soldiers at risk. Soldiers who attempt suicide may be perceived and consequently treated as disturbed youth who are trying to manipulate others rather than as victims of their own suffering. Ehud presents some practical suggestions for the prevention of suicidal behaviors in soldiers. K. Jaishankar, Megha Desai and P. Madhava Soma Sundaram target in Chapter Fourteen the stalking phenomenon in India and relate this form of victimization to a transformation in social-cultural perception of this phenomenon. Jai, Megha and Madhavan present results from a survey of college students that indicate patterns of repeated intrusions and harassment techniques. They document victim reluctance to report this behavior, and effects of stalking on the victims. In the closing chapter in this section, Chapter Fifteen, Brenda Geiger presents a qualitative research of domestically abused Druze women, a group whose voice is rarely heard. These women have to struggle on two fronts: (a) to content with their abusive spouses; and (b) to contend with the context-relevant ideology, norms and perceptions of their extended families. Their family attempts to force them to reconcile with the abusive spouse and to reconcile themselves to continued abuse. As Noach Milgram indicated in the opening chapter of this book, ideology may deny the natural human rights of victims. Brenda presents, however, an optimistic picture of the struggle of abused Druze women and their successful claim for rights and power.

Frontiers in Psychology

Juan M Rodríguez-díaz

Several studies have examined victim blaming in rape scenarios. However, there is limited research on the analysis of the perception of blame when two or more perpetrators are involved. The present article explores the perception of blame in cases involving rape based on the level of resistance shown by the victim and the presence of one or more perpetrators. A study was carried out involving 351 university students who responded to a survey after reading a hypothetical assault scenario. Six situations were established where the victim showed either low or high resistance, depending on whether the resistance was verbal or physical and verbal, and in the presence of one or two male perpetrators. It is expected that perpetrators are more culpable when acting in groups and that less resistance from the victim leads to greater attribution of blame. The results confirm that more blame is attributed to the perpetrators when they act in groups than when they act alone. Likewise, women cons...

RELATED PAPERS

Lotta Persson

JUAL OBAT BURUNG

Supplier Hewan

Current Science

HARDEV SINGH Virk

Gabriel Yagnycz

Universitas PGRI Ronggolawe

Luhur M O E K T I Prayogo, S.Si., M.Eng

Fauzi Ahmad

FEMS Microbiology Letters

H. Van Vuuren

International Journal of Plant …

Mritunjay Kumar

Journal of Cardiac Critical Care TSS

Dr.Arvind Prakash

Inorganic Chemistry

Rosie Walker

Itinera Spiritualia. Commentarii Periodici Instituti Carmelitani Spiritualitatis Cracoviae

Joseph Gardella

Pollarise GROUPS

Mesail: Üç Aylık Düşünce Dergisi

Cemal Atabaş

Journal of High Energy Physics

Sanjaye Ramgoolam

Australian Educational Computing

Yavuz Akbulut

Indian Journal of Fibre & Textile Research

Tina Navaei

Gretchen Mann

2012 International Conference on Wireless Communications in Underground and Confined Areas

Nadir Hakem

The American Journal of Human Genetics

Victoria Cortessis

Psychiatry and behavioral sciences

Ibrahim Yagci

Angelo Lauria

Tom Petersen

Ioachim Romanovich Chabibullin

See More Documents Like This

RELATED TOPICS

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- J Child Adolesc Trauma

- v.14(2); 2021 Jun

Filipino Children and Adolescents’ Stories of Sexual Abuse: Narrative Types and Consequences

Nora maria elena t. osmeña.

1 Psychology Department, Negros Oriental State University, Dumaguete City, Philippines

Dan Jerome S. Barrera

2 College of Criminal Justice Education, Negros Oriental State University, Dumaguete City, Philippines

There is a paucity of qualitative research on children’s and adolescents’ perceptions of their sexual abuse experiences. This paper aims to describe the narrative types and consequences of sexual abuse stories among ten female Filipino children and adolescents. Data were collected through semi-structured interviews and analyzed using dialogical narrative analysis. Results show that three narrative types appear in the stories of the survivors. These are the tragic resistance narrative, rescued slave narrative, and heroic saga narrative, and each of these narratives has idiosyncratic effects on the identities, affiliations, disclosure, and adjustment processes of the participants. The results show how symbolic cultural structures can have far-reaching consequences on sexually abused children and adolescents.

Introduction

Sexual abuse in childhood and adolescence remains a prevalent social problem. A worldwide estimate shows that 13% of girls and 6% of boys experience sexual abuse in childhood and adolescence (Barth et al. 2013 ). As a result, they experience debilitating adverse mental, psychological, physical, and health effects (Amado et al. 2015 ; Hillberg et al. 2011 ; Maniglio 2009 ; Norman et al. 2012 ; Teicher and Samson 2016 ). In the Philippines, a national survey shows that the lifetime prevalence of child and youth sexual abuse is 21.5% - 24.7% for boys and 18.2% for girls (CWC and UNICEF 2016 ). These reported abuses are a bit higher than some worldwide estimates, and they even lead to early smoking, sex, and pregnancy, having multiple partners, substance use, and suicide among the victims (Ramiro et al. 2010 ). Despite this information, research on children’s and adolescents’ narratives on sexual abuse in the Philippines gathered through qualitative approaches t is limited (Roche 2017 ). This gap is not surprising because systematic reviews show that only a handful of extant studies have analyzed children’s and adolescents’ perceptions of their sexual abuse experiences (Morrison et al. 2018 ; Watkins-Kagebein et al. 2019 ). The bulk of the literature on children and adolescents’ sexual abuse experiences comes from retrospective accounts of adult survivors (Alaggia et al. 2019 ; Tener and Murphy 2015 ), which may differ from children’s and adolescents’ themselves due to recall bias, participants’ advanced developmental phase, and other factors (Foster and Hagedorn 2014 ; Morrison et al. 2018 ; Watkins-Kagebein et al. 2019 ).

Nevertheless, there has been a recent surge of interest in studying young victims’/survivors’ sexual abuse accounts. These studies documented the emotional experiences of children and adolescents, including their fear, anger, pain, worry, and coping strategies (Foster and Hagedorn 2014 ; McElvaney et al. 2014 ; San Diego 2011 ; Schönbucher et al. 2012 ); the disclosure processes and their barriers and facilitators (Foster and Hagedorn 2014 ; Jackson et al. 2015 ; Jensen et al. 2005 ; McElvaney et al. 2014 ; Schaeffer et al. 2011 ; Schönbucher et al. 2012 ); and the subjects’ healing journey through therapeutic processes (Capella et al. 2016 ; Foster and Hagedorn 2014 ; San Diego 2011 ). Besides the emotional aspects, secondary victimization in the justice system (Foster and Hagedorn 2014 ; Capella et al. 2016 ) also manifested in the reports.

However, what remains underexplored in these studies and adult retrospections are the meso-level factors that affect post-sexual abuse emotions, reactions (e.g., disclosures), coping and adjustment, and identity work. One example at the meso-level is culture (Sanjeevi et al. 2018 ). In their review, Sanjeevi et al. ( 2018 , p. 631) note that studying culture is essential to “provide culturally competent and culturally valid services” to children and adolescents who have experienced sexual abuse. However, this inquiry line is underdeveloped as most culturally-oriented studies have either studied culture as practices (e.g., ways of raising a child, sleeping arrangements, child marriage) or beliefs (e.g., beliefs on what constitutes sexual abuse). A treatment of culture as a system of symbols is absent in child sexual abuse literature, especially in studies of children and adolescents’ accounts of their sexual abuse experiences. In this study, we treat culture as “a structure of symbolic sets” that “provide[s] a nonmaterial structure” of actions by “creating patterned order, lines of consistency in human actions” (Alexander and Smith 1993 , p. 156). Furthermore, a narrative is an example of a symbol. Narratives are culturally available resources and structures (e.g., tragedy, romance, comedy) with which people construct their personal stories (Frank 2010 ). Furthermore, narrative analysis makes these narrative types visible (Wong and Breheny 2018 ).

The narrative approach has not been extensively used in sexual abuse studies. Although few studies employ this methodology (e.g., Capella et al. 2016 ; Foster and Hagedorn 2014 ; Harvey et al. 2000 ; Hunter 2010 ), these studies were more thematic. They focused more on the ‘what”s’ of storytelling and neglected the ‘how’s’ (Gubrium and Holstein 2009 ). Thus, there is a need for other narrative approaches like dialogical and structural (Riessman 2008 ). We argue that Arthur Frank’s ( 2010 , 2012 ) socio-narratology and dialogical narrative analysis can fill this void.

Socio-narratology views stories not just as retrospective devices of representing the past but also prospective ones that interpellate people to assume identities, affiliate/disaffiliate from others and do things (Frank 2010 , 2012 ). As Alameddine ( 2009 : 450) notes: “Events matter little, only stories of those events affect us.” This view tends to find support in some narrative psychologists’ (e.g., Bruner 1987 ; Polkinghorne 1988 ) and philosophers’ (Carr 1986 ; MacIntyre 1981 ; Ricoeur 1984 ) stand on the power of stories in people’s lives. As Polkinghorne ( 1988 , p. 145) posited, life/action is the “living narrative expression of a personal and social life. The competence to understand a series of episodes as part of our story informs our own decisions to engage in actions that move us toward a desired ending.” Polkinghorne added that stories and narratives provide us with models for the self, action, and life, and we use these models to plan our actions and assume identities.

This paper aims to describe the narrative types and consequences of sexual abuse stories among ten female Filipino children and adolescents. We argue that cultural symbols in the form of narratives describe phenomena through personal stories, and they also tend to influence emotions and actions. This perspective, we believe, is also applicable to children’s and adolescents’ stories and experiences of sexual abuse. Narrative types can be visible from these stories of sexual abuse, which have material effects on disclosure processes, emotions, coping, identity work, and behavioral and social adjustment of children and adolescents who have had the experience.

Methodology

The researchers sought to capture data by profiling the Filipino children’s and adolescents’ lives before, during, and after experiencing sexual abuse through semi-structured interviews. The participants were contacted and recruited through a temporary government-controlled crisis center in the province of Negros Oriental, Philippines, where they were housed. Of the twelve participant interviews, only ten were analyzed because two participants did not answer some questions critical to the analysis.

Table Table1 1 shows the socio-demographic characteristics of the participants. As shown, most of the participants were sexually abused in their adolescence (10–19) by family members with whom they lived at the time of the abuse. At the time of the interview, all of them had studied for at least 3 years when the abuse started.

Socio-demographic charateristics of the participants

Data Gathering Procedures

After having been granted the ethics board approval, consent from the government agency that controlled the center, the caregivers, and the participants was obtained. Contacts with the target participants were developed through the said government agency, which had personal information in the center. The target participants were then informed about the nature of the study and its purpose and were also asked about their willingness to participate. They were briefed on the confidentiality of the information gathered from them and the anonymity of their identity. Those who opted to participate were requested to sign informed consent forms and to indicate their preferred schedule and place of interview, which could be any place conducive.

The study utilized face-to-face semi-structured interviews, which were conducted by the lead author and employing narrative interviewing techniques (Jovchelovitch and Bauer 2000 ). A debriefing to prevent the recurrence of trauma was given to the participant right after every interview, which could last for 30 min to one-and-a-half hours. All audio-recorded interviews were password-secured and were only transcribed and translated by language-proficient staff and verified by the researchers for accuracy and consistency. For ethical reasons, participants’ names and other information were kept anonymous and replaced with pseudonyms.

Dialogical Narrative Analysis

Frank ( 2010 , 2012 ) coupled socio-narratology with his methodological technique – dialogical narrative analysis (DNA). DNA is a heuristic guide in analyzing stories. It is a combination of thematic, structural, and dialogical analyses (Smith 2016 ). DNA “studies the mirroring between what is told in the story – the story’s content – and what happens as a result of telling that story – its effects” (Frank 2010 , pp. 71–72). In other words, DNA is concerned with the content of stories and their effects on selves, affiliations, and actions. Although Frank ( 2010 , 2012 ) intended DNA to be heuristic in nature, there are phases of the analysis that can be implemented (see also Caddick 2016 ; Smith 2016 ). However, these phases are not necessarily linearly followed: even in a later phase, one can always return to the initial ones.

The present analysis started with getting the story phase done by the first researcher. Here, the stories in each interview were identified using Labov and Waletzky’s ( 1967 ) structural model of narratives. Then, the getting to grips with the stories phase was implemented by the two researchers. Indwelling with the data by listening to the audios and reading the transcripts several times was done at this phase. Also, narrative themes, relationships among themes, and the structure of the stories were identified. The opening up analytical dialogue phase followed by asking dialogical questions by the two authors directed towards the narratives identified (Frank 2012 ). This makes DNA unique from other analyses. Dialogical questions include resource questions, affiliation questions, and identity questions. Finally, pulling the analysis together phase was done by choosing among the five forms of DNA, the best way to structure the results. We chose to build a narrative typology as our approach. Narrative types are ‘the most general storyline[s] that can be recognized underlying the plot and tensions of particular stories’ (Frank 1995 : 75). After weeks of analysis, the data revealed three narrative types and their consequences, which are discussed in the next section.

The Narrative Types

This section shows that there are three significant narratives to which the participants of this study subscribe. These narratives are tragic resistance narrative, rescued slave narrative, and heroic saga narrative . The most common among these are the tragic resistance and the rescued slave narratives. The heroic saga narrative serves as a contesting narrative against the dominant ones. We will also show that these narratives interpellate the participants to assume particular identities (selves), connect or disconnect from alliances, and do things for and on them.

Tragic Resistance Narrative

Its structure.

A common narrative emplotted by some of the participants is the tragic resistance narrative. This narrative starts with some favorable situations, followed by a disruption in the form of sexual abuse. Due to fear of negative consequences, the participants subscribing to this narrative tended not to disclose their victimization. Moreover, if they disclosed, they did it covertly with those outside the family. This does not mean, however, that they did not do anything against the offender. They tended to make subtle but covert resistance against the abusers. This narrative has this structure: “Girls live a normal life. It is made horrible when they are raped. However, they could not disclose it because they fear that their resistance might fail as the abuser might retaliate.” This narrative appears to be a derivative of the culturally available rape myths such as “No woman can do much about rape” (Gordon and Riger 1989 ; Plummer 2003 ). Also, fear of retaliation among the sexual abuse victims in the Philippines circulates culturally (Hunt and Gatbonton 2000 ). Previous research also documents fears experienced by children and adolescents due to their abusive experiences (Foster and Hagedorn 2014 ; McElvaney et al. 2014 ; Schönbucher et al. 2012 ).

One example of this kind of narrative is a story told by Mary, who was raped by her father. She said,

That night, he came home very drunk. My brother and I only slept side by side in the sala of our house. Then my father laid down in between my brother and me and started to undress me. I said, “No, Pa,” but he held a knife and said that he would kill me if I refused. So, he succeeded in undressing me and finally raped me. When he inserted his penis into my vagina, it was very painful. It happened when I have not even had my first menstruation yet. When I tried to move, he would threaten me with the knife.

Mary did not continue to resist because of the threat made by her father to kill her if she would fight. She emplotted her experience in a tragic resistance narrative yet did not offer more resistance. Other participants’ stories unfolded through this type of narrative. Ana, for instance, shared this story:

One time when my Mama left, my father and my siblings were left at home. Then he [stepfather] attempted to rape me, but I shouted, and it was on time that my Mama came back. So Mama had the incident blottered. My stepfather was so mad. Eventually, he was put behind bars because my godmother, who was a policewoman, helped us. We went home to Zamboanguita because we were in Bayawan during that time. We did not know that he was temporarily freed but he was able to post bail. He came back and planned to kill us all. He murdered Mama, who was pregnant. I was almost killed too. He almost killed Lolo. If Lolo was not able to kill him, all of us could have been killed. Lolo killed him at that time.

Ana related that she screamed when her stepfather attempted to rape her and her mother reported it to the police. Then, the offender was arrested and detained. However, such resistance was tragic. When the offender was able to post bail, he retaliated and killed her pregnant mother and almost killed her, but her grandfather eventually killed him. This tragic resistance created extreme fear in her as she relayed, “.. . that is what I fear. Because of me, my family would kill each other.”

Jess took the same narrative to describe her initial resistance against her stepfather. It was not her stepfather, however, who foiled her resistance. It was her mother. Her mother prevented Jess’s attempt to resist. She said: “He abused me every night, and if I said no, he would go wild. I was angry with my Mama because she did not believe me.”

Tragic Resistance Narrative’s Effects on the Self, Relationships, and Actions

With the tragic resistance narrative, the participants experienced what Freeman ( 2010 ) calls narrative foreclosure , wherein one believes that he or she has no or little prospect for the future. This is detrimental to the self. Some participants experienced hopelessness and even considered committing suicide. This kind of narrative led them to offer little (covert) or no resistance against subsequent abuses. They even became emotionally attached to their abusers.

Dirty and Foreclosed Self

When asked what she felt immediately after the abuse, Jess described herself as

“Filthy. I considered myself filthy because my being had been devastated by a person who was good for nothing .”

She also felt that her future was foreclosed as she lamented,

“I felt hopeless. I felt like I was already totally hopeless. I can’t think of any solution to the problem during that time. I thought there was nobody who could help me because I was hesitant to tell anybody.”

Ana and Mary had the same thought about themselves immediately after the repeated sexual abuse. And after a considerable number of years, they still felt marred by such molestations, although not as intense as immediately after the incidents. For instance, Mary still felt her womanhood tarnished:

“Sometimes, I feel I am the filthiest person. My father sexually abused me.”

Ana had a similar struggle with herself even long after the event. She continued to experience confusion about herself.

Interviewer: Let me ask you this, “How is Ana?” Ana: Tired. Interviewer: What makes Ana tired? Ana: It’s like I do not understand myself.

“Yes, we see each other because her peers are also our classmates, but we feel nothing more than friends. She would just tell me to take care, then we go our separate ways. She asked me why I get attracted to girls. I said I am not attracted to girls; I get attracted to boyish girls. I used to get attracted to boys, but now I hate them. I never had feelings towards lesbians before. When a cousin of mine got into a relationship with a lesbian, I even admonished her from getting involved with the same sex. I wonder why I have changed. Ate Lyn even asked me why I got into a relationship with a girl.”

Emotional Attachment with the Abuser

The tragic resistance narrative invites the participants to build an emotional attachment with the abusers. This is in line with some qualitative research that documented children’s conflicted feelings toward their abusers (Morrison et al. 2018 ). Probably, this is to prevent any harmful retaliatory acts from the abuser towards the abused or to their significant others or to make the abusers believe that they were not resisting.

For instance, after she was abused for the first time, Ana lived with her uncle; she was again raped by her cousin. This time, she did not resist her cousin overtly after the death of her mother and her unborn child, which resulted from her previous overt resistance against her stepfather. Instead, she built a close relationship with her cousin and his family with which she was living. When asked about the frequentness of being abused by her cousin, Ana said:

“He did it to me, maybe two or three times in a month. Sometimes I got insulted because he would bring his girlfriend, and still continued to abuse me. (But) I had high respect for him as an older brother.”

Ana may have been “insulted” or probably jealous that her cousin had a girlfriend whom he brought latter to their house. This indicates her attachment with the abuser, which is also manifested in the last sentence, where she expressed her respect towards him as her elder brother. Ana treated him as part of her family and considered his family her own; in fact, she even participated in their family drinking sessions and became drunk at times. And just like Ana, Mary also became attached to her father, who raped her repeatedly. This was because she was concerned with what could happen to him if she would leave him. She said:

“He even told me that he wanted me for his wife because women avoid him. After all, he bathes only once a week. He smells foul and dirty. I was the one who did his laundry. Our neighbors kept on telling me to finish my studies so that I could get away from him. But it is difficult to leave him. I am concerned about him because every time he got drunk, he would wake up everybody and put a fight.”

Subtle Resistance and Disclosure

A tragic narrative calls one for inaction because of fear (Smith 2005 ). It curtails any hope for the future and halts one from advancing towards it. Similar things occurred among some of the participants. Despite the abuses, they stayed with their abusers. That is why they experienced repeated sexual abuse. Their actions were enactions dictated by the emplotted narrative of their experiences of abuse (Frank 2010 ). Their actions became dialogical copies of their narrative. Nevertheless, instead of not doing anything, they made subtle resistance and disclosure. They expressed their agency strategically in a covert way, possibly, to avoid retaliation from the offender.

Ana, for instance, feigned a pregnancy after experiencing repeated abuses. This was a very strategic ploy. It was effective and, at the same time, did not require her to create a disorder in the family; although, there were still risks associated with it. She shared:

“At the end of December, I pretentiously told him I was pregnant to stop him from raping me. He was terrified, and he did stop raping me. He even gave me some pills, but I did not take them.”

On the other hand, Kay employed playful covert resistance. She used jokes against her abuser, although it had no similar effect as that of Ana’s. For example, she said,

“Mama’s brother used to carry a gun and has abused me several times - five times already. At times, I would jokingly tell him: “You know, I will report what happened; I will report you, Uncle, to the police station.” But, he wasn’t thinking that I was joking. I asked him, “Uncle, how many times have you done it to me already? Do you remember you stripped me naked, you removed my panty and my skirt and then kissed me in the mouth, my breasts, and licked my bottom?” After that, he warned me: “Do not to tell your father, mother, and my older brother -- because if you do, I will shoot them.” I said, “Yes, Uncle, I understand.” I was crying at that time.”

In this case, the participants made subtle disclosures – although not within their immediate family. They disclosed to their friends, neighbors, and the police. Mary opened to her neighbors (boarders), who were also caught in a tragic resistance narrative. This time, it is the neighbor’s daughter who was almost raped by her drunk father. But they did not report it to the authorities. She shared this:

“They asked me what my father did to me, but I did not answer them; I only cried. They said it would be New Year so I should have a new life and should not be staying at home always. That prompted me to tell them what happened to me. They asked me how I should deal with the situation. That was it; they were also afraid to report to the police because my father warned that whoever will help me, will be killed. He also warned of killing my brother and me if I would tell anybody about the incident.”

Ana made a similar kind of disclosure to the mother of her best friend. She did not disclose it to her uncle, who supported her, because she feared that a similar tragic event in her family would occur again. Ana said:

Interviewer: Did you tell anybody? Ana: I didn’t tell anyone except the mother of my best friend whom I trusted most. Interviewer: What prompted you to tell? Ana: Because I could no longer bear the thought that even his father can do the same to me when we were supposed to be kins. So I told the mother of my classmate, and she even cried.

Rescued Slave Narrative

Another common narrative invoked by the participants is the rescued slave narrative. This is a progressive type of narrative (Gergen and Gergen 1988 ). Emancipation was the key theme in this narrative: emancipation from the bondage of sex slavery and other forms of oppression. However, this emancipation was not the participants’ initiative but of other people and a Higher Being. The agency on the part of the participants was minimal, especially in terms of disclosure and resistance. This narrative’s typical structure is: “Women are subjected to slavery and other forms of oppression. They become martyr slaves and break down inside. Somebody rescues them, and they are freed from the bondage of their abusers.”

Joy had employed this kind of narrative. She was repeatedly raped by her grandfather as if she were a sex slave. She broke down and cried. She was asked why and then she disclosed. Then, some people helped her get her grandfather arrested and incarcerated.

“The first time I got raped was when I was eight years old. Since then, I was raped by my Lolo several times. I never told anyone about it because he warned me not to. Every time he gets drunk, he would rape me. One time, my Lola's sibling was in the house, and my nephews and nieces, Lolo started to rape me. However, I cried, so they asked me why I was crying. It was then that I told them about it. They helped me get my abuser jailed.”

This rescued slave narrative tends to be a mimetic copy of her slave narrative before the sexual abuses occurred. The same is also true with the other participants who employed this kind of narrative. Their narrative of the abuses was dialogical (Frank 2010 ) because it cohered with the narratives of their lives before the abuses. We can see that Joy’s slave narrative during the abuses formed a dialogue with her narrative of her experiences before the abuses. Both narratives cohered. Joy shared that before the abuses happened,