Introduction to Academic Reading and Writing: Thesis Statements

- Concept Map

- Select a Topic

- Develop a Research Question

- Identify Sources

Thesis Statements

- Effective Paragraphs

- Introductions and Conclusions

- Quote, Paraphrase, Summarize

- Synthesize Sources

- MLA and APA

- Transitions

- Eliminate Wordiness

- Grammar and Style

- Resource Videos

Use your research question to create a thesis statement that is focused and contains a debatable claim.

After narrowing your topic with your research question, craft an answer that states a position regarding that question.

Use words such as “should” or “ought to” indicating a claim is being made.

Keep your thesis as concise as possible.

Conduct further research to determine the best points of support to include in your thesis statement, if required.

If you include points of support as part of your thesis statement, make sure that they maintain parallel grammatical structure.

If a reader’s first response to your thesis statement could be “How?” or “Why?” your thesis statement may not be sufficiently narrow or specific.

- << Previous: Draft

- Next: Outline >>

- Last Updated: Aug 21, 2023 12:23 PM

- URL: https://libguides.lbc.edu/Introtoacademicreadingandwriting

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

167 What’s the Point: Finding Thesis Statements

What is a thesis statement.

In academic writing, thesis statements help readers understand the topic and purpose of the composition you’re sharing with them. Thesis statements put up a signpost that identifies your destination and the direction you’ll take. Thesis statements also help you, the writer, focus your work; as you write, you can return to this statement periodically and consider how well you’re sticking to the topic and how well you’re proving your thesis.

By the way, thesis statements may be present in other types of writing, from news articles to memoirs, as well as the focused academic, professional, and scholarly works you’ll use for research and to compose your own essays, reports, and more.

For example, consider these thesis statements:

- Healthcare reform in America is long overdue, and there is no other policy proposition more unequivocally prepared to provide substantial and affordable healthcare, mental health and substance abuse treatment than a single-payer, national health insurance program — better known as Medicare for All. (Cantu 2021)

- I am going to write an essay describing my experiences with fat oppression and the ways in which feminism and punk have affected my work. (Lamm 1975/2001).

- The concept of infinity has different applications in mathematical, philosophical, and cosmological studies.

- We argue that as we are talking about what we “know,” we also need to pivot and think about what we (as composition scholars) don’t know, as well as what novices (such as graduate students) need to know to be effective teachers of writing. (Brewer & di Gennaro 2022)

These examples all fulfill the definition provided in the textbook First-Year Composition: Writing as Inquiry and Argumentation : “A solid thesis statement notifies readers of the writer’s topic and prepares readers for the argument to come.” In other words, a thesis is both a signpost (“notifies readers”) and a roadmap (“prepares readers”).

Let’s consider thesis statements in another way:

- Watch Martha Ann Kennedy’s short YouTube video, “ How to Identify the Thesis Statement .”

- What are thesis statements?

- What clues help you find them?

How Do I Find the Thesis Statement?

Thesis statements can be difficult to find, even for experienced readers. Sometimes, they’re located at the start of the first paragraph of the essay or article. Sometimes, they’re located at the end of that first paragraph. Sometimes — especially in longer articles and in academic books — they’re located several paragraphs or pages into the piece.

What’s a reader to do?

Tips for Finding Thesis Statements

- First, read the title. Scholarly articles, essays, books, and studies usually provide very descriptive and detailed titles that identify the topic. Titles often provide a clue to the author’s point of view, position on the topic, direction of the piece, and key argument.

- Second, read the abstract, if there is one. These entries usually give a somewhat detailed overview. Good abstracts clearly identify the topic, outline the study methods used (if any), and clearly state the author’s argument, conclusions, or findings. Quite often, the thesis statement is the last full sentence of the abstract.

- Third, read the first paragraph or — for longer articles and books — the first page or so. The idea is to get the sense of the piece. But, as with the abstract, pay close attention to the first and last sentences. Quite often, the thesis statement is the last full sentence of the first paragraph.

- As you read, look for sentences that use words like “argue,” “claim,” “conclude,” “contend,” “will,” “in this …,” “should.” There are a few other key words that are common, but these will get you started.

- Finally, ask yourself if the steps above have helped you identify what the essay or article is about, what the author’s position is, and what argument they’re making (or what conclusions they are presenting). Is there one sentence that sums up these details? If so, that’s a candidate for the thesis statement.

- If you’re not sure, repeat or revisit one of the steps above.

Want to learn more?

- “ What is a Thesis Statement and Why is it Important? ”

- “ What is a Thesis Statement? I Need Some Examples, Too .”

- “ How to Find Thesis Statements ”

Reading and Writing in College Copyright © 2021 by Jackie Hoermann-Elliott and TWU FYC Team is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Please log in to save materials. Log in

- Thesis Statement

Thesis Statements: How to Identify and Write Them

Students read about and watch videos about how to identify and write thesis statements.

Then, students complete two exercises where they identify and write thesis statements.

*Conditions of Use: While the content on each page is licensed under an Attribution Non-Commercial Share Alike license, some pages contain content and/or references with other types of licenses or copyrights. Please look at the bottom of each page to view this information.

Learning Objectives

By the end of these readings and exercises, students will be able to:

- define the term thesis statement

- read about two recommended thesis statement models

- practice identifying thesis statements in other texts

- write your own effective thesis statements

Attributions:

- The banner image is licensed under Adobe Stock .

- The untitled image of a detective by Peggy_Marco is licensed under Pixabay .

What is a thesis statement?

The thesis statement is the key to most academic writing. The purpose of academic writing is to offer your own insights, analyses, and ideas—to show not only that you understand the concepts you’re studying, but also that you have thought about those concepts in your own way and agreed or disagreed, or developed your own unique ideas as a result of your analysis. The thesis statement is the one sentence that encapsulates the result of your thinking, as it offers your main insight or argument in condensed form.

We often use the word “argument” in English courses, but we do not mean it in the traditional sense of a verbal fight with someone else. Instead, you “argue” by taking a position on an issue and supporting it with evidence. Because you’ve taken a position about your topic, someone else may be in a position to disagree (or argue) with the stance you have taken. Think about how a lawyer presents an argument or states their case in a courtroom—similarly, you want to build a case around the main idea of your essay. For example, in 1848, when Elizabeth Cady Stanton drafted “The Declaration of Sentiments,” she was thinking about how to convince New York State policymakers to change the laws to allow women to vote. Stanton was making an argument.

Some consider all writing a form of argument—or at least of persuasion. After all, even if you’re writing a letter or an informative essay, you’re implicitly trying to persuade your audience to care about what you’re saying. Your thesis statement represents the main idea—or point—about a topic or issue that you make in an argument. For example, let’s say that your topic is social media. A thesis statement about social media could look like one of the following sentences:

- Social media harms the self-esteem of American pre-teen girls.

- Social media can help connect researchers when they use hashtags to curate their work.

- Social media tools are not tools for social movements, they are marketing tools.

Please take a look at this video which explains the basic definition of a thesis statement further (we will be building upon these ideas through the rest of the readings and exercises):

Attributions:

- The content about thesis statements has been modified from English Composition 1 by Lumen Learning and Audrey Fisch et al. and appears under an Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

- The video "Purdue OWL: Thesis Statements" by the Purdue University Online Writing Lab appears under a YouTube license .

The Two-Story Model (basic)

First, we will cover the two-story thesis statement model. This is the most basic model, but that doesn't mean it's bad or that you shouldn't use it. If you have a hard time with thesis statements or if you just want to keep things simple, this model is perfect for you. Think of it like a two-story building with two layers.

A basic thesis sentence has two main parts:

- Topic: What you’re writing about

- Angle: What your main idea is about that topic, or your claim

Examples:

When you read all of the thesis statement examples, can you see areas where the writer could be more specific with their angle? The more specific you are with your topic and your claims, the more focused your essay will be for your reader.

Thesis: A regular exercise regime leads to multiple benefits, both physical and emotional.

- Topic: Regular exercise regime

- Angle: Leads to multiple benefits

Thesis: Adult college students have different experiences than typical, younger college students.

- Topic: Adult college students

- Angle: Have different experiences

Thesis: The economics of television have made the viewing experience challenging for many viewers because shows are not offered regularly, similar programming occurs at the same time, and commercials are rampant.

- Topic: Television viewing

- Angle: Challenging because shows shifted, similar programming, and commercials

Please watch how Dr. Cielle Amundson demonstrates the two-story thesis statement model in this video:

- The video "Thesis Statement Definition" by Dr. Cielle Amundson appears under a YouTube license .

The Three-Story Model (advanced)

Now, it's time to challenge yourself. The three-story model is like a building with three stories. Adding multiple levels to your thesis statement makes it more specific and sophisticated. Though you'll be trying your hand with this model in the activity later on, throughout our course, you are free to choose either the two-story or three-story thesis statement model. Still, it's good to know what the three-story model entails.

A thesis statement can have three parts:

- Relevance : Why your argument is meaningful

Conceptualizing the Three-Story Model:

A helpful metaphor based on this passage by Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr.:

There are one-story intellects, two-story intellects, and three-story intellects with skylights. All fact collectors who have no aim beyond their facts are one-story men. Two-story men compare, reason, generalize using the labor of fact collectors as their own. Three-story men idealize, imagine, predict—their best illumination comes from above the skylight.

One-story theses state inarguable facts. Two-story theses bring in an arguable (interpretive or analytical) point. Three-story theses nest that point within its larger, compelling implications.

The biggest benefit of the three-story metaphor is that it describes a process for building a thesis. To build the first story, you first have to get familiar with the complex, relevant facts surrounding the problem or question. You have to be able to describe the situation thoroughly and accurately. Then, with that first story built, you can layer on the second story by formulating the insightful, arguable point that animates the analysis. That’s often the most effortful part: brainstorming, elaborating and comparing alternative ideas, finalizing your point. With that specified, you can frame up the third story by articulating why the point you make matters beyond its particular topic or case.

Though the three-story thesis statement model appears a little bit differently in this video, you can still see how it follows the patterns mentioned within this section:

- The content about thesis statements has been modified from Writing in College by Amy Guptill from Milne Publishing and appears under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

- The video "How to Write a STRONG Thesis Statement" by Scribbr appears under a YouTube license .

Identifying Thesis Statements

You’ll remember that the first step of the reading process, previewing , allows you to get a big-picture view of the document you’re reading. This way, you can begin to understand the structure of the overall text. The most important step of understanding an essay or a book is to find the thesis statement.

Pinpointing a Thesis Statement

A thesis consists of a specific topic and an angle on the topic. All of the other ideas in the text support and develop the thesis. The thesis statement is often found in the introduction, sometimes after an initial “hook” or interesting story; sometimes, however, the thesis is not explicitly stated until the end of an essay. Sometimes it is not stated at all. In those instances, there is an implied thesis statement. You can generally extract the thesis statement by looking for a few key sentences and ideas.

Most readers expect to see the point of your argument (the thesis statement) within the first few paragraphs. This does not mean that it has to be placed there every time. Some writers place it at the very end, slowly building up to it throughout their work, to explain a point after the fact. Others don’t bother with one at all but feel that their thesis is “implied” anyway. Beginning writers, however, should avoid the implied thesis unless certain of the audience. Almost every professor will expect to see a clearly discernible thesis sentence in the introduction.

Shared Characteristics of Thesis Statements:

- present the main idea

- are one sentence

- tell the reader what to expect

- summarize the essay topic

- present an argument

- are written in the third person (does not include the “I” pronoun)

The following “How to Identify a Thesis Statement” video offers advice for locating a text’s thesis statement. It asks you to write one or two sentences that summarize the text. When you write that summary, without looking at the text itself, you’ve most likely paraphrased the thesis statement.

You can view the transcript for “How to Identify the Thesis Statement” here (download).

Try it!

Try to check your thesis statement identification skills with this interactive exercise from the Excelsior University Online Writing Lab.

- The video "How to Identidy the Thesis Statement" by Martha Ann Kennedy appears under a YouTube license .

- The "Judging Thesis Statements" exercise from the Purdue University Online Writing Lab appears under an Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

Writing Your Own Thesis Statements

A thesis statement is a single sentence (or sometimes two) that provides the answers to these questions clearly and concisely. Ask yourself, “What is my paper about, exactly?” Answering this question will help you develop a precise and directed thesis, not only for your reader, but for you as well.

Key Elements of an Effective Thesis Statement:

- A good thesis is non-obvious. High school teachers needed to make sure that you and all your classmates mastered the basic form of the academic essay. Thus, they were mostly concerned that you had a clear and consistent thesis, even if it was something obvious like “sustainability is important.” A thesis statement like that has a wide-enough scope to incorporate several supporting points and concurring evidence, enabling the writer to demonstrate his or her mastery of the five-paragraph form. Good enough! When they can, high school teachers nudge students to develop arguments that are less obvious and more engaging. College instructors, though, fully expect you to produce something more developed.

- A good thesis is arguable . In everyday life, “arguable” is often used as a synonym for “doubtful.” For a thesis, though, “arguable” means that it’s worth arguing: it’s something with which a reasonable person might disagree. This arguability criterion dovetails with the non-obvious one: it shows that the author has deeply explored a problem and arrived at an argument that legitimately needs 3, 5, 10, or 20 pages to explain and justify. In that way, a good thesis sets an ambitious agenda for a paper. A thesis like “sustainability is important” isn’t at all difficult to argue for, and the reader would have little intrinsic motivation to read the rest of the paper. However, an arguable thesis like “sustainability policies will inevitably fail if they do not incorporate social justice,” brings up some healthy skepticism. Thus, the arguable thesis makes the reader want to keep reading.

- A good thesis is well specified. Some student writers fear that they’re giving away the game if they specify their thesis up front; they think that a purposefully vague thesis might be more intriguing to the reader. However, consider movie trailers: they always include the most exciting and poignant moments from the film to attract an audience. In academic papers, too, a well specified thesis indicates that the author has thought rigorously about an issue and done thorough research, which makes the reader want to keep reading. Don’t just say that a particular policy is effective or fair; say what makes it is so. If you want to argue that a particular claim is dubious or incomplete, say why in your thesis.

- A good thesis includes implications. Suppose your assignment is to write a paper about some aspect of the history of linen production and trade, a topic that may seem exceedingly arcane. And suppose you have constructed a well supported and creative argument that linen was so widely traded in the ancient Mediterranean that it actually served as a kind of currency. 2 That’s a strong, insightful, arguable, well specified thesis. But which of these thesis statements do you find more engaging?

How Can You Write Your Thesis Statements?

A good basic structure for a thesis statement is “they say, I say.” What is the prevailing view, and how does your position differ from it? However, avoid limiting the scope of your writing with an either/or thesis under the assumption that your view must be strictly contrary to their view.

- focus on one, interesting idea

- choose the two-story or three-story model

- be as specific as possible

- write clearly

- have evidence to support it (for later on)

Thesis Statement Examples:

- Although many readers believe Romeo and Juliet to be a tale about the ill fate of two star-crossed lovers, it can also be read as an allegory concerning a playwright and his audience.

- The “War on Drugs” has not only failed to reduce the frequency of drug-related crimes in America but actually enhanced the popular image of dope peddlers by romanticizing them as desperate rebels fighting for a cause.

- The bulk of modern copyright law was conceived in the age of commercial printing, long before the Internet made it so easy for the public to compose and distribute its own texts. Therefore, these laws should be reviewed and revised to better accommodate modern readers and writers.

- The usual moral justification for capital punishment is that it deters crime by frightening would-be criminals. However, the statistics tell a different story.

- If students really want to improve their writing, they must read often, practice writing, and receive quality feedback from their peers.

- Plato’s dialectical method has much to offer those engaged in online writing, which is far more conversational in nature than print.

You can gather more thesis statement tips and tricks from this video titled "How to Create a Thesis Statement" from the Florida SouthWestern State College Academic Support Centers:

- The video "How to Create a Thesis Statement" by the Florida SouthWestern State College Academic Support Centers appears under a YouTube license .

Additional, Optional Resources

If you feel like you might need more support with thesis statements, please check out these helpful resources for some extra, optional instruction:

- "Checklist for a Thesis Statement" from the Excelsior University Online Writing Lab which appears under an Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

- "Developing Your Thesis" from Hamiliton College which appears under a copyright.

- "Parts of a Thesis Sentence and Common Problems" from the Excelsior University Online Writing Lab which appears under an Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

- "Tips and Examples for Writing Thesis Statements" from the Purdue University Writing Lab which appears under a copyright.

- "Writing Thesis Statements & Hypotheses" by Hope Matis from Clarkson University which appears under a copyright.

- The content about these resources has been modified from English Composition 1 by Lumen Learning and Audrey Fisch et al. and appears under an Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0) license.

- The content about these resources has been modified from Writing in College by Amy Guptill from Milne Publishing and appears under an Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) license.

- The untitled image of the books by OpenClipart-Vectors is licensed under Pixabay .

Exercise #1: Identify Thesis Statements

Throughout the readings, we have been learning what an effective thesis statement is and what it is not. Before we even get to writing our own thesis statements, let's look for real-world examples. It's your turn to locate and identify thesis statements!

Objectives/Goals

By completeting this exercise students will be able to:

- identify the main ideas within a text

- summarize the main ideas within a text

- choose one sentence from the text which you believe is the thesis statement

- argue why you believe that's the true thesis statement of the text

Instructions

- Any print or online text (probably something around a page in length) will be fine for this exercise.

- If you have trouble finding a text, I recommend looking at this collection from 88 Open Essays – A Reader for Students of Composition & Rhetoric by Sarah Wangler and Tina Ulrich.

- Write the title of the text that you selected and the full name(s) of the author (this is called the full citation).

- Provide a hyperlink for that text.

- Write one paragraph (5+ sentences) summarizing the main points of the text.

- Write one more argumentative paragraph (5+ sentences) where you discuss which sentence (make sure it appears within quotation marks, but don't worry about in-text citations for now) you think is the author's thesis statement and why.

Submitting the Assignment

You will be submitting Exercise #1: Identify Thesis Statements within Canvas in our weekly module.

Please check the assignment page for deadlines and Canvas Guides to help you in case you have trouble submitting your document.

- "88 Open Essays - A Reader for Students of Composition & Rhetoric" by Sarah Wangler and Tina Ulrich from LibreTexts appears under an Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International (CC BY-SA 4.0) license.

Exercise #2: Write Your Own Thesis Statements

Now that you've had some practice with locating and identifying thesis statements, you are ready to write some practice thesis statements yourself.

- write a two-story thesis statement

- write a three-story thesis statement

- reflect on your thesis statement skills

- Using the same text from Exercise #1, write a two-story thesis statement in response to that text.

- Using the same text from Exercise #1, write a three-story thesis statement in response to that text.

- Is it easy for you to identify thesis statements in other texts? Why or why not?

- What methods do you use to identify/locate thesis statements?

- In the past, how have you felt when you needed to write a thesis statement?

- How did you feel about writing your own thesis statements in Exercise #2?

- Which thesis statement writing strategies were the most beneficial to you? Why?

- What challenges did you face when you were writing you thesis statement for Exercise #2?

You will be submitting Exercise #2: Write Your Own Thesis Statements within Canvas in our weekly module.

- The untitled image of the writing supplies by ptra is licensed under Pixabay .

Version History

Writing based on Texts

Thesis sentence.

Any text written to inform, react, apply, analyze or persuade has a main idea. In the article about “ How Crisco Toppled Lard ,” for example, the main idea is that Crisco was one of the first food products to introduce and popularize marketing by brand, which allowed them to focus on concepts such as reliability and purity instead of ingredients. The main idea is not stated directly in one sentence, but is presented clearly in the article nonetheless.

On the other hand, if you look at the article “ Everyday Life as a Text ,” you’ll find a direct statement of the author’s main idea in the sentence that comes right after the introduction: “the data-intensive monitoring of everyday life offers some measure of soft control over audiences in a digital media landscape.”

In both cases, the “Crisco” article written to inform, and the “Everyday Life as Text” article written to persuade, a main idea is clear. If you thought consciously about your experience reading these articles, you might have identified their clarity as a good characteristic, as it helped you, as a reader, understand the message the author wanted to convey.

As a writer, you owe that same clarity to your reader. You do that through key sentences in your essay:

- thesis sentence

- topic sentences (explained on the next page)

Thesis – A Writer’s and Reader’s Map

In the days before Google Maps, when you went on a road trip, you needed to know the route. Say you’re in Utah, going to Moab from Salt Lake. You’d need to know to travel through Provo, then Spanish Fork, and – this is important – take the Highway 6 exit from I-15 at Spanish Fork. Highway 6 will lead to Helper and Price, where it merges with Highway 191 and leads to Green River and then on to Moab. You’d get the general idea in your head and mentally check off each town as you pass. If you miss the exit for Hwy 6 that leads to Price, you’ll find yourself 70 miles down I-15 in Scipio and, if you stop at one of the two gas stations for instructions, you’ll realize you’ve added 74 miles and an hour to your drive. It would be an adventure.

Your audience, often your instructor and peers, aren’t likely to be as adventurous. In fact, if you tell them you’re going one place and then go somewhere else, they may feel mistreated and annoyed. Academic writing is usually not a whimsical road trip. It’s more like your audience needs a ride to their job interview and they need to get there on time. Your thesis is your roadmap.

When composing your thesis, think, “What do I want my audience to know or think when they are done reading my essay?” Answer this question, and you’re on your way to a good thesis. Your thesis will probably change many times as you are composing and drafting, but in your final draft, the destination should be clear.

Your thesis outlines the essay

Consider this thesis for an essay whose purpose is to analyze the writing style of a document rather than the subject of that document:

Notice a few things in this thesis:

- It makes a debatable assertion about a topic – the destination it intends to go to.

- It’s longer than one sentence, which is o.k.

- It uses guiding words to show what the essay will talk about, and in what order. Just as map will show you to drive through Provo, Spanish Fork, Helper, Price, and Green River to get to Moab, the thesis tells your audience they will read about ethos, pathos, and logos, which are writing devices. Your reader will expect to read about them in that order.

Your thesis will help you set up a map or idea outline of an essay. The points in your thesis will be the sections of your outline.

Don’t confuse major points for paragraphs. According to the outline above, the essay will have three major points: ethos, pathos, and logos. To properly cover the subject, you’ll want to have a few paragraphs for each of the points.

More About Thesis Sentences

A thesis sentence offers your main idea. In essays, a thesis sentence usually comes toward or at the end of the introductory paragraph, after you acclimate your reader to your topic. A thesis sentence is more than just a topic, though. It’s made up of a topic and an angle, which is an insight into, assertion, or claim about the topic. Together, the topic and angle make up the main idea. To put it another way, a thesis sentence makes a promise to your reader of 1) what you will be writing about (your topic), and 2) what your main assertion is about your topic (your angle). For college essays, make sure you always include a thesis sentence to keep yourself on track supporting your main idea, and to make that main idea absolutely clear for your reader.

Remember that a thesis is not a simple statement of what you will be writing about (topic). You always need to include that angle – your insight, assertion, or claim – about your topic in order to have an actual thesis sentence.

Not a Thesis: In this paper, I’m writing about current scientific research on cancer.

- topic = current scientific research on cancer

- angle = ? what’s the claim about this research?

Thesis: Current scientific research on cancer suggests that there are specific environmental factors that trigger specific types of cancer.

- angle = specific environmental factors trigger specific types

- promise = the essay will offer evidence on specific environmental triggers for specific cancers

Not a Thesis: My husband and I decided that we are both “messy” people.

- topic = messiness

- angle = ? so what? what’s the debatable point?

Thesis: Although my husband defines “messy” differently than I do, we both agree that “messiness” resides in four qualities of mind, which we both–unfortunately–seem to share.

- angle = four qualities constitute messiness

- promise = explanation and examples of the four qualities

In addition to having a topic and an angle, a good thesis sentence needs to be:

- debatable – otherwise, you simply have a topic and not an angle or claim

- supportable with reasons, examples, and evidence – otherwise, you may information that’s not logical

- appropriate in scope – otherwise, you may be making a claim that’s too broad to support logically within a short essay, or a claim that’s too narrow to be supported with more than a few sentences or paragraphs

An excellent thesis sentence also:

- includes an arguable issue or concept that can be analyzed with some complexity

- sets that issue or concept in an interesting context

Thesis sentence examples

- Basic Thesis : Online learning is becoming more prevalent and takes many different forms. ( has a topic and angle, and is supportable, but the angle is broad. The angle would be more interesting if it offered an argument about an issue related to online learning.)

- Good Thesis : Strong thesis: While most observers see it as a transformation of higher education, online learning is better thought of an extension of higher education in that it reaches learners who aren’t disposed to participate in traditional campus-based education.( has a topic and angle, angle is arguable, supportable, and well-specified )

- Excellent Thesis : Online learning appears to be a promising way to better integrate higher education with other institutions in society, as online learners integrate their educational experiences with the other realms of their life, promoting the freer flow of ideas between the academy and the rest of society. ( has a topic and angle, angle is arguable, supportable, and well-specified, angle contains implications that set the argument within a broader context )

- Basic Thesis : Scientists disagree about the likely impact in the U.S. of the Light Brown A pple Moth (LBAM) , an agricultural pest native to Australia. ( has a topic and an angle, and the angle is supportable, but the angle is broad. The angle would be more interesting if it offered an argument about an issue related to the light brown apple moth.)

- Good Thesis : Research findings to date suggest that the decision to spray pheromones over the skies of several southern Californian counties to combat the light brown apple moth was poorly thought out. ( has a topic and angle, angle is arguable, supportable, and well-specified )

- Excellent Thesis : Together, the scientific ambiguities and the controversial response strengthen the claim that industrial-style approaches to pest management are inherently unsustainable. ( has a topic and angle, angle is arguable, supportable, and well-specified, angle contains implications that set the argument within a broader context )

How to Write a Thesis Sentence

After you prewrite for an essay, a usual next step is to create a working thesis sentence in order to start writing a draft. Know that you don’t have to create a perfect thesis sentence as you start writing; that’s why it’s called a “working thesis.” You just have to make sure you have a working topic and angle. You may edit and refine your working thesis sentence as you write, as long as you retain a topic and an angle.

The following video explains how to write a thesis sentence.

Regardless of how complicated the subject is, almost any thesis can be constructed by asking and then answering a question—this is one method of creating a thesis that works for many writers.

- Thesis: Computers provide second graders an early advantage in simple searching techniques.

- Thesis: The Mississippi River symbolizes both division and progress in Huckleberry Finn , as it separates Huck and Jim while still providing the best chance for them to get to know one another.

- Thesis: Through careful sociological study, we’ve found that people naturally assume that “morally righteous” people look down on them as “inferior,” causing anger and conflict where there generally is none.

Then tailor your thesis to the type of paper you’re writing; the purpose of your essay will help you write a strong thesis.

- Thesis: The dynamic between different generations sparks much of the tension in King Lear , as age becomes a motive for the violence and unrest that rocks the king.

- Thesis: Without the steady hand and specific decisions of Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the U.S. would never have recovered from the great depression of 1929-1939.

- Thesis: The explosion of 1800’s philosophies such as Positivism, Marxism, and Darwinism undermined and refuted established religions’ focus on other-worldliness to instead focus on the real, tangible world.

Most thesis sentences for college essays will be analytical, or a combination of analytical and argumentative. If a writing assignment calls for an “essay” without any other explanation, assume that you’ll need to create and support an analytical or analytical/argumentative thesis sentence.

The following video offers an excellent explanation of how to write an analytical thesis sentence . As you view, make sure to pause the video at the points indicated, and try working on sample thesis sentences. (The video will open in a new window when you click on the image.)

USEFUL RESOURCE:

To help develop thesis sentences, you can use SUNY Empire State College’s Thesis Generator . For a general, non-research thesis, use the Persuasive Thesis option.

- Attending college as an adult student is difficult.

- Reading – both reading to a child and teaching a child to read – helps that child develop.

try it again…

Which of the samples below is a good thesis—with a clear topic and an angle that provides an assertion—for an essay based on ideas a reader develops from reading the article “How Crisco Toppled Lard?” Choose all sample thesis sentences that could be used for an essay intended to react to, apply concepts from, or analyze a concept developed from reading the text.

- When compared to Crisco, lard actually may be a healthier alternative to use for baking.

- Successful brand marketing relies on a number of factors, including a clear purpose, a focused customer base, creative messaging and, most of all, a public willing to accept the message, which needs to address current public sentiment.

- Because images in advertising art reflect their historic context, you can infer what’s important to the general public at different eras through analyzing ads.

- Crisco has a long and varied history.

- The use of fat has fallen out of favor in a health-conscious society; however, there are scientific reasons to use fat in baking as well as to include fats in a human diet, reasons we should be teaching in school so that students can make informed food choices.

All of the sample thesis sentences are appropriate for an essay intended to react, apply, or analyze, except sentence 4. Sentence 4 contains an angle that has a very weak assertion that’s quite broad in scope. It’s also somewhat obvious—if you investigated most food products that have been in existence for some time, you could most likely say that they all have a long and varied history. This statement would be usable only for an essay intended to inform others about the history of Crisco.

While all of the other statements are usable, some are better than others in terms of specificity and setting the assertion within a broader context.

- Thesis Sentence, includes material adapted from College Writing, Basic Reading and Writing, and Open English @ SLCC; attributions below. Authored by : Susan Oaks. Project : Introduction to College Reading & Writing. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- College writing, pages on Thesis Sentence Definition, Characteristics of a Strong Thesis, Thesis Sentence Topic & Angle Examples, Thesis Sentence Self-Check. Authored by : Susan Oaks. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-esc-wm-englishcomposition1/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- image of hand drawing a lightbulb with the word Idea. Authored by : Pete Linforth. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/idea-innovation-inspiration-3908619/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- video The Elements of an Effective Thesis Statement. Authored by : GC Writing Center. Provided by : Gaston College. Located at : https://youtu.be/g-0o5bnmRYs . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- Organizing, adaptation of multiple sources. Provided by : Lumen Learning. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-basicreadingwriting/chapter/outcome-organizing/ . Project : Basic Reading and Writing. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- 27 Follow a Map and Grab a Sandwich. Authored by : Stacie Draper Weatbrook. Provided by : Salt Lake Community College. Located at : https://openenglishatslcc.pressbooks.com/chapter/follow-a-map-and-grab-a-sandwich-help-your-reader-navigate-your-writing/ . Project : Open English @ SLCC. License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

Privacy Policy

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Prewriting: Organizing and Outlining

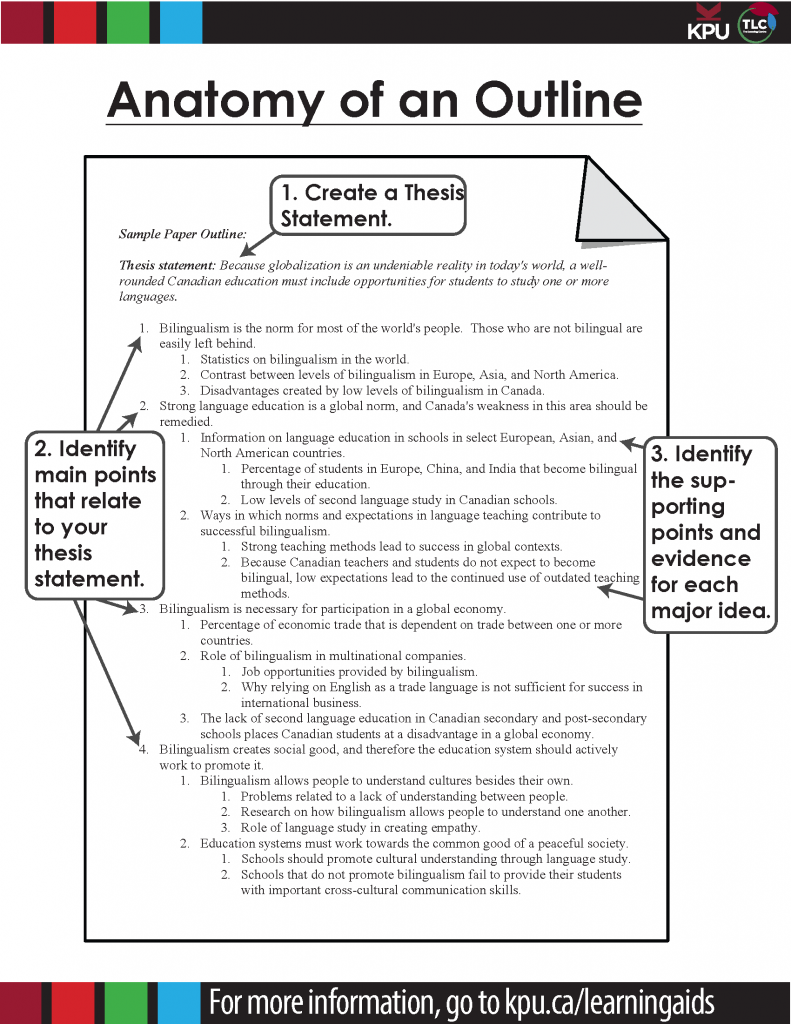

29 Outlining

Outlining is a useful pre-writing tool when you know your topic well or at least know the areas you want to explore.

An outline can be written before you begin to write, and it can range from formal to informal. Many writers work best from a list of ideas or from freewriting, but you may have an assignment that is purely to create an outline.

(Note: A reverse outline can be useful once you have written a draft, during the revision process. For more on reverse outlining , see the “Revising” section.)

Traditional Outline

A traditional outline uses a numbering and indentation scheme to help organize your thoughts. Generally, you begin with your main point, stated as a topic sentence or thesis (see “Finding the Thesis” in the “Drafting Section”), and place the subtopics—the main supports for your topic sentence/thesis—and finally fill out the details underneath each subtopic. Each subtopic is numbered and has the same level of indentation. Details under each subtopic are given a different style of number or letter and are indented further to the right. It’s expected that each subtopic will merit at least two details.

Most word-processing applications include outlining capabilities. Try to create an outline with yours.

Here’s an example:

- Detail/Evidence/Support

- Support/Example/Detail

- Evidence/Support/Example

- Example/Support/Evidence

Outlining an Essay

Step 1: create a thesis statement.

If you are writing an essay or research paper, you will begin by writing a draft thesis statement . A thesis statement is a concise presentation of the main argument you will develop in your paper. Write the thesis statement at the top of your paper. You can revise this later if needed.

The rest of your outline will include the main point and sub-points you will develop in each paragraph.

Step 2: Identify the main ideas that relate to your thesis statement

Based on the reading and research you have already done, list the main points that you plan to discuss in your essay. Consider carefully the most logical order, and how each point supports your thesis. These main ideas will become the topic sentences for each body paragraph.

Step 3: Identify the supporting points and evidence for each major idea

Each main point will be supported by supporting points and evidence that you have compiled from other sources. Each piece of information from another source must be cited, whether you have quoted directly, paraphrased, or summarized the information.

Step 4: Create your outline

Outlines are usually created using a structure that clearly indicates main ideas and supporting points. In the example below, main ideas are numbered, while the supporting ideas are indented one level and labelled with letters. Each level of supporting detail is indented further.

Create an outline for a paper or report for one of your courses.

- Write a thesis statement that clearly presents the argument that you will make.

- Use a multi-level outline, similar to the one in the example above, to create an outline before you begin writing.

Text Attributions

- This chapter was adapted from “ Strategies for Getting Started ” in The Word on College Reading and Writing by Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear, which is licensed under a CC BY-NC 4.0 Licence . Adapted by Allison Kilgannon.

- Text under “Outlining an Essay” was adapted from “ Create an Outline ” in University 101: Study, Strategize and Succeed by Kwantlen Polytechnic University Learning Centres, which is licensed under a CC BY-SA 4.0 Licence . Adapted by Allison Kilgannon.

Media Attributions

- “Anatomy of an Outline” by Graeme Robinson-Clogg is under a CC BY-SA 4.0 Licence .

Outlining Copyright © 2021 by Allison Kilgannon is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

4.48: Text- Paraphrasing a Thesis Statement

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 59073

We’ve discussed the fact that every piece of writing has a thesis statement , a sentence that captures the main idea of the text. Some are explicit –stated directly in the text itself. Others are implicit –implied by the content but not written in one distinct sentence.

You’ll remember that the “How to Identify a Thesis Statement” video offered advice for locating a text’s thesis statement. Remember when it asks you to write 1 or 2 sentences that summarize the text? When you write that summary, without looking at the text itself, you’ve actually paraphrased the thesis statement.

Review this process by re-watching the video here.

An interactive or media element has been excluded from this version of the text. You can view it online here: http://pb.libretexts.org/braw/?p=218

Click here to download a transcript for this video

Paraphrasing is a skill that asks you to capture the idea of a text, without using any of the same words. This is harder to do than it might first appear. Like advanced reading skills, it takes practice to do well.

As you paraphrase, keep the following tips in mind:

- Paraphrases are roughly the same length as the original text . If the thesis sentence is a medium-length sentence, your paraphrase will also be a medium-length sentence (though it doesn’t have to have exactly the same number of words).

- Paraphrases use entirely distinct wording from the original text . Common small words like “the” and “and” are perfectly acceptable, of course, but try to use completely different nouns and verbs. If needed, you can quote short snippets, 1-2 words, if you feel the precise words are necessary.

- Paraphrases keep the same meaning and tone as the original text . Make sure that anyone reading your paraphrase would understand the same thing, as if they had read the original text you paraphrased.

- Text: Paraphrasing a Thesis Statement. Provided by : Lumen Learning. License : CC BY: Attribution

- How to Identify the Thesis Statement. Authored by : Martha Ann Kennedy. Located at : https://youtu.be/di1cQgc1akg . License : All Rights Reserved . License Terms : Standard YouTube License

COMMENTS

identify strategies for using thesis statements to predict content of texts. Being able to identify the purpose and thesis of a text, as you're reading it, takes practice. This section will offer you that practice. One fun strategy for developing a deeper understanding the material you're reading is to make a visual "map" of the ideas.

Adaptions: Reformatted, some content removed to fit a broader audience. 5.2: Identifying Thesis Statements and Topic Sentences is shared under a CC BY-NC-ND license and was authored, remixed, and/or curated by LibreTexts. Topic sentences and thesis statements are similar to main ideas. This section discusses those similarities and the ...

Keep your thesis as concise as possible. Conduct further research to determine the best points of support to include in your thesis statement, if required. If you include points of support as part of your thesis statement, make sure that they maintain parallel grammatical structure.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like thesis statement, Elements of a thesis statement, Topic and more. Try Magic Notes and save time. Try it free

There is only one thesis statement in a text. Topic sentences, in this relationship, serve as captains: they organize and sub-divide the overall goals of a writing into individual components. Each paragraph will have a topic sentence. Figure 2.5.2 2.5. 2. It might be helpful to think of a topic sentence as working in two directions ...

In academic writing, thesis statements help readers understand the topic and purpose of the composition you're sharing with them. Thesis statements put up a signpost that identifies your destination and the direction you'll take. Thesis statements also help you, the writer, focus your work; as you write, you can return to this statement ...

5. A troublesome thesis is a fragment; a good thesis statement is expressed in a complete sentence. Example: How life is in New York after September 11th. Better: After September 11th, the city of New York tends to have more cases of post-traumatic disorder than other areas of the United States and rightfully so.

Placement of the thesis statement. Step 1: Start with a question. Step 2: Write your initial answer. Step 3: Develop your answer. Step 4: Refine your thesis statement. Types of thesis statements. Other interesting articles. Frequently asked questions about thesis statements.

identify strategies for using thesis statements to predict content of texts. Being able to identify the purpose and thesis of a text, as you're reading it, takes practice. This section will offer you that practice. One fun strategy for developing a deeper understanding the material you're reading is to make a visual "map" of the ideas.

Write one paragraph (5+ sentences) summarizing the main points of the text. Write one more argumentative paragraph (5+ sentences) where you discuss which sentence (make sure it appears within quotation marks, but don't worry about in-text citations for now) you think is the author's thesis statement and why.

A thesis sentence offers your main idea. In essays, a thesis sentence usually comes toward or at the end of the introductory paragraph, after you acclimate your reader to your topic. A thesis sentence is more than just a topic, though. It's made up of a topic and an angle, which is an insight into, assertion, or claim about the topic.

What is thesis statement? Click the card to flip 👆 Central idea of the text, summarize the topic and the arguments of the writer about the topic, can be in one or two sentences long

Figure 2.5. 2. It might be helpful to think of a topic sentence as working in two directions simultaneously. It relates the paragraph to the essay's thesis, and thereby acts as a signpost for the argument of the paper as a whole, but it also defines the scope of the paragraph itself. For example, consider the following topic sentence:

Write the thesis statement at the top of your paper. You can revise this later if needed. The rest of your outline will include the main point and sub-points you will develop in each paragraph. Step 2: Identify the main ideas that relate to your thesis statement. Based on the reading and research you have already done, list the main points that ...

Lesson 1 - Thesis Statement and Outline Reading Text; To accomplish the desired performance stated, please be guided with the following learning competencies as anchor: ... Direction: Identify the thesis statement in each of the following text. Write you answers on a separate sheet. Psychologists have argued for decades about how a person's ...

No headers. We've discussed the fact that every piece of writing has a thesis statement, a sentence that captures the main idea of the text.Some are explicit-stated directly in the text itself.Others are implicit-implied by the content but not written in one distinct sentence.. You'll remember that the "How to Identify a Thesis Statement" video offered advice for locating a text ...

Steps in creating a reading outline 1. Read the entire text first. Skim the text afterward. Having an overview of the reading's content will help you follow its structure better. 2. Locate the thesis statement. 3. Look for the key ideas in each paragraph of the essay. 4. Look at the topic sentence and group related ideas together. 5.

• States the thesis statement of an academic text (CS_EN11/12A-EAPP-Ia-c-6) • Outlines reading texts in various disciplines (CS_EN11/12A-EAPP-Ia-c-8) Learning Objectives: At the end of the lessons, you will be able to: 1. State the thesis statements of an academic text. 2. Create an outline reading texts in various disciplines.

About Press Copyright Contact us Creators Advertise Developers Terms Privacy Policy & Safety How YouTube works Test new features NFL Sunday Ticket Press Copyright ...

Lesson 4 - Identifying Thesis Statement and Outline Reading Text - Free download as Word Doc (.doc / .docx), PDF File (.pdf), Text File (.txt) or read online for free. yrety