Read our research on: Abortion | Podcasts | Election 2024

Regions & Countries

On the Intersection of Science and Religion

Over the centuries, the relationship between science and religion has ranged from conflict and hostility to harmony and collaboration, while various thinkers have argued that the two concepts are inherently at odds and entirely separate .

But much recent research and discussion on these issues has taken place in a Western context, primarily through a Christian lens. To better understand the ways in which science relates to religion around the world, Pew Research Center engaged a small group of Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists to talk about their perspectives. These one-on-one, in-depth interviews took place in Malaysia and Singapore – two Southeast Asian nations that have made sizable investments in scientific research and development in recent years and that are home to religiously diverse populations.

The discussions reinforced the conclusion that there is no single, universally held view of the relationship between science and religion, but they also identified some common patterns and themes within each of the three religious groups. For example, many Muslims expressed the view that Islam and science are basically compatible, while, at the same time, acknowledging some areas of friction – such as the theory of evolution conflicting with religious beliefs about the origins and development of human life on Earth. Evolution also has been a point of discord between religion and science in the West .

Hindu interviewees generally took a different tack, describing science and religion as overlapping spheres. As was the case with Muslim interviewees, many Hindus maintained that their religion contains elements of science, and that Hinduism long ago identified concepts that were later illuminated by science – mentioning, for example, the antimicrobial properties of copper or the health benefits of turmeric. In contrast with Muslims, many Hindus said the theory of evolution is encompassed in their religious teachings.

Buddhist interviewees generally described religion and science as two separate and unrelated spheres. Several of the Buddhists talked about their religion as offering guidance on how to live a moral life, while describing science as observable phenomena. Often, they could not name any areas of scientific research that concerned them for religious reasons. Nor did Buddhist interviewees see the theory of evolution as a point of conflict with their religion. Some said they didn’t think their religion addressed the origins of life on Earth.

Some members of all three religious groups, however, did express religious concerns when asked to consider specific kinds of biotechnology research, such as gene editing to change a baby’s genetic characteristics and efforts to clone animals. For example, Muslim interviewees said cloning would tamper with the power of God, and God should be the only one to create living things. When Hindus and Buddhists discussed gene editing and cloning, some, though not all, voiced concern that these scientific developments might interfere with karma or reincarnation.

But religion was not always the foremost topic that came to mind when people thought about science. In response to questions about government investment in scientific research, interviewees generally spoke of the role of scientific achievements in national prestige and economic development; religious differences faded into the background.

These are some of the key findings from a qualitative analysis of 72 individual interviews with Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists conducted in Malaysia and Singapore between June 17 and Aug. 8, 2019.

The study included 24 people in each of three religious groups (Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists), with an equal number in each country. All interviewees said their religion was “very” or “somewhat” important to their lives, but they otherwise varied in terms of age, gender, profession and education level.

A majority of Malaysians are Muslim, and the country has experienced natural migration patterns over the years. As a result, Buddhist interviewees in Malaysia were typically of Chinese descent, Hindus were of Indian descent and Muslim interviewees were Malay. Singapore is known for its religious diversity; a 2014 Pew Research Center analysis found the city-state to have the highest level of religious diversity in the world.

Insights from these qualitative interviews are inherently limited in that they are based on small convenience samples of individuals and are not representative of religious groups either in their country or globally. Instead, in-depth interviews provide insight into how individuals describe their beliefs, in their own words, and the connections they see (or don’t see) with science. To help guard against putting too much weight on any single individual’s comments, all interviews were coded into themes, following a systematic procedure. Where possible throughout the rest of this report, these findings are shown in comparison with quantitative surveys conducted with representative samples of adults in global publics to help address questions about the extent to which certain viewpoints are widely held among members of each religious group. This also shows how Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists as well as Christians around the world compare with each other.

The goal of this project was to better understand how people think about science in connection with their religious beliefs. Past research on this topic has often focused on the views of Christians living in the U.S. or other economically advanced nations. This study sought to fill that gap by talking, one-on-one, with Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists living in two growing economies in Southeast Asia: Malaysia and Singapore. Pew Research Center conducted qualitative interviews with 72 people, including 24 in each of the three religious groups (12 in each country).

To be eligible for the study, interviewees had to identify their religious affiliation as Muslim, Hindu or Buddhist, and describe religion as either “very” or “somewhat” important in their lives. They varied in other demographic characteristics, including age, gender, ethnicity, profession, employment status and educational attainment.

Interviews were conducted by Ipsos Qualitative with a local, professional interviewer, using a guide developed by Pew Research Center. Interviews lasted about one hour and were conducted in English in Singapore, and in English or Malay in Malaysia. The Singaporean interviews were conducted June 17 to July 26, 2019, and the Malaysian interviews were done July 31 to Aug. 8, 2019.

Center researchers listened to audio recordings of the interviews and systematically coded transcripts for thematic responses, using qualitative data analysis software. Themes were revised and integrated throughout the coding process, until researchers agreed upon a consistent set of categories. The qualitative interviews are based on small, convenience samples of individuals and are not representative of religious groups in either country. Whenever possible, these findings are shown in comparison with quantitative data from global surveys using representative samples of adults who identify as Muslim, Hindu, Buddhist or Christian. You can find the interview guide here .

Interviewees paint three distinct portraits of the science-religion relationship

One of the most striking takeaways from interviews conducted with Muslims, Hindus and Buddhists stems from the different ways that people in each group described their perspectives on the relationship between science and religion. The Muslims interviewed tended to speak of an overlap between their religion and science, and some raised areas of tension between the two. Hindu interviewees, by and large, described science and religion as overlapping but compatible spheres. By contrast, Buddhist interviewees described science and religion as parallel concepts, with no particular touchpoints between the two.

A similar pattern emerged when interviewees were asked about possible topics that should be off limits to scientific research for religious reasons. Many Muslim interviewees readily named research areas that concerned them, such as studies using non-halal substances or some applications of assisted reproductive technology (for example, in vitro fertilization using genetic material from someone other than a married couple). By contrast, the Hindus and Buddhists in the study did not regularly name any research topics that they felt should be off limits to scientists.

Muslim interviewees say science and religion are related, but they vary in how they see the nature of that relationship

On the relationship between science and islam.

“I don’t see any conflicts [between science and religion]. From what I know in the Quran, they say that there is science in Islam. They talk about the sun, the moon, the stars. They talk about how the water can go up to the sky and become the clouds. When it’s heavy, it goes down to the Earth where it’s taken by the plants when it evaporates up again. It’s part of science.” – Muslim man, age 35, Singapore

“I know that sometimes science and religion don’t tally. … As a person of religion, we tend to believe what our book says. Yeah, I believe what the Quran says, [rather] than scientific proof.” – Muslim woman, age 40, Singapore

Muslims frequently described science and their religion as related, rather than separate, concepts. They often said that their holy text, the Quran, contains many elements of science. The Muslims interviewed also said that Islam and science are often trying to describe similar things. “The research in science are related to the Quran. There are similarities between religion and what is explained by science,” said one Muslim woman (age 25, Malaysia).

The Muslims interviewed offered a wide variety of opinions about the nature of the relationship between science and religion, and whether the two are harmonious or conflicting. Some described science and Islam as compatible overall. For example, one Muslim man said that both science and his religion explain the same things, just from different perspectives: “I think there is not any conflict between them. … In my opinion, I still believe that it happens because of God, just that the science will help to explain the details about why it is happening” (age 24, Malaysia). Others qualified their statement by saying that science is compatible with religion, but the actions of individual scientists can be problematic. “Actually, science and religion don’t conflict with each other – it’s humans’ opinions that conflict,” said one interviewee (Muslim man, age 36, Malaysia).

Still others described the relationship as conflictual. “I feel like, sometimes, or most of the time, they are against each other. … Science is about experimenting, researching, finding new things, or exploring different possibilities. But then, religion is very fixed, to me,” said one Muslim woman (age 20, Singapore). Another interviewee said scientists typically do not consider the views of religious people when conducting their research. “Scientists, whatever they do, they don’t ask for opinions from people well-versed in religious matters,” said another Muslim woman (age 39, Malaysia).

When asked, many of the Muslims interviewed identified specific areas of scientific research that bothered them on religious grounds. Some of the areas mentioned by multiple interviewees included research that uses non-halal substances (such as marijuana, alcohol or pigs), some pregnancy technologies that they considered unnatural (for example, “test tube babies” or procedures that use genetic material not taken from a husband and wife) or cloning.

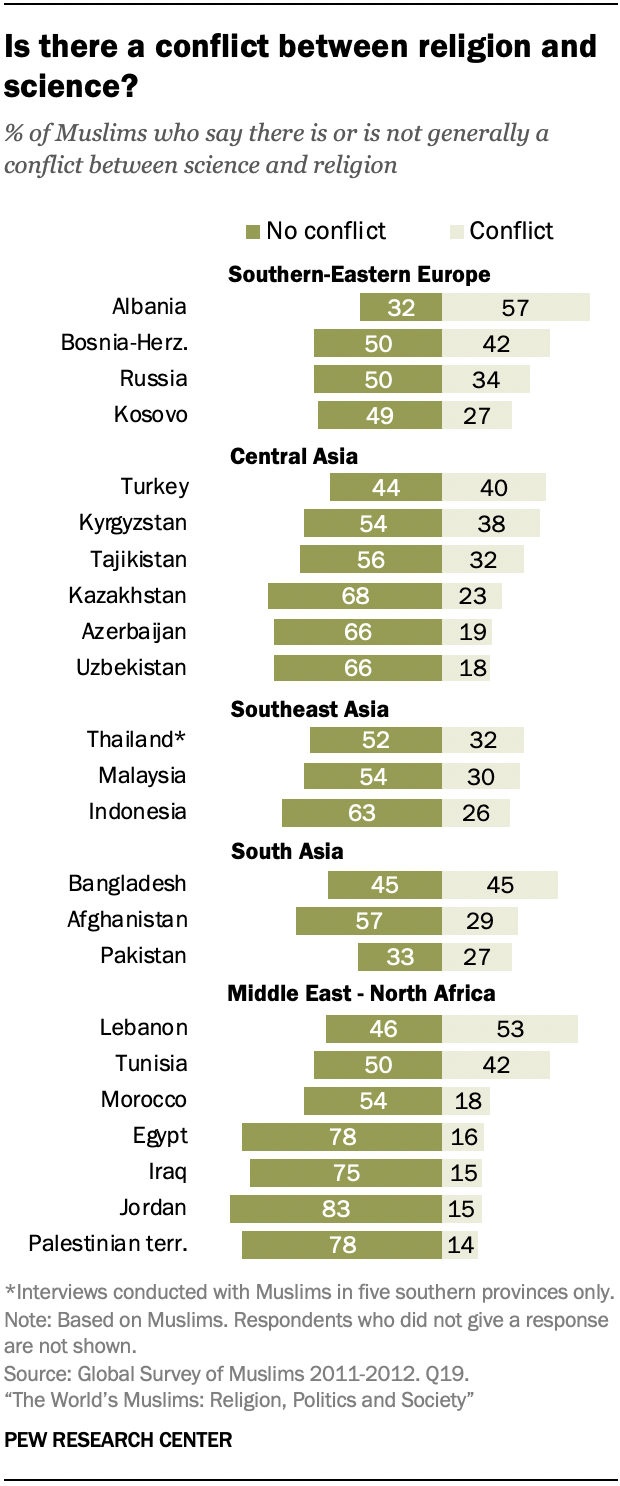

Similarly, a Pew Research Center survey conducted in 2011 and 2012 that examined the views of Muslims found that, in most regions, half or more said there was no conflict between religion and science, including 54% in Malaysia (Muslims in Singapore were not surveyed). Three-in-ten Malaysian Muslims said there is a conflict between science and religion; the share of Muslims around the world who took this position ranged from a high of 57% in Albania to a low of 14% in the Palestinian territories.

Hindu interviewees generally see science and religion as compatibly overlapping spheres

The predominant view among Hindus interviewed in Malaysia and Singapore is that science and Hinduism are related and compatible. Many of the Hindu interviewees offered – without prompting– the assertion that their religion contains many ancient insights that have been upheld by modern science. For instance, multiple interviewees described the use of turmeric in cleansing solutions, or the use of copper in drinking mugs. They said Hindus have known for thousands of years that these materials provide health benefits, but that scientists have only confirmed relatively recently that it’s because turmeric and copper have antimicrobial properties. “When you question certain rituals or rites in Hinduism, there’s also a relatively scientific explanation to it,” said a Hindu woman (age 29, Singapore).

On the relationship between science and Hinduism

“I believe that whatever science says, the purpose has already been told in my religion. For example, it is said that drinking water from a copper container is very good. This has been proven by the ancestors many years ago. But now only these scientific people come out and say that it is good to use it.” – Hindu woman, age 29, Malaysia

“No, feel free to go ahead and [research] everything. Why would you need to restrict yourself from information or knowledge? Because Hinduism is based on knowledge. It’s called ‘Nyaya.’ That’s ‘knowledge,’ literally translated.” – Hindu man, age 38, Singapore

While many of the Hindu interviewees said science and religion overlap, others described the two as separate realms. “Religion doesn’t really govern science, and it shouldn’t. Science should just be science. … Today, the researchers, even if they are religious, the research is your duty. The duty and religion are different,” said one Hindu man (age 42, Singapore).

Asked to think about areas of scientific research that might raise concerns or that should not be pursued for religious reasons, Hindu interviewees generally came up blank, saying they couldn’t think of any such areas. A few mentioned areas of research that concerned them, but no topic area came up consistently.

Buddhist interviewees see science and religion as operating in parallel domains

Buddhist interviewees described science and religion in distinctly different ways than either Muslims or Hindus. For the most part, Buddhists said that science and religion are two unrelated domains. Some have long held that Buddhism and its practice are aligned with the empirically driven observations in the scientific method ; connections between Buddhism and science have been bolstered by neuroscience research into the effects of Buddhist meditation at the core of the mindfulness movement.

On the relationship between science and Buddhism

“Science is something more modern, but Buddhism is something like a mindset. And science is more practical, but Buddhism is theoretical. It is not conflicting.” – Buddhist man, age 40, Malaysia

“I would say that the two [science and religion] are running parallel. It’s difficult to merge the two.” – Buddhist man, age 64, Singapore

One Buddhist woman (age 39, Malaysia) said science is something that relates to “facts and figures,” while religion helps her live a good and moral life. Another Singaporean Buddhist woman (age 26) explained that, “Science to me is statistics, numbers, texts – something you can see, you can touch, you can hear. Religion is more of something you cannot see, you cannot touch, you cannot hear. I feel like they are different faculties.”

To many of the Buddhist interviewees, science and religion cannot be in conflict, because they are different or parallel realms. Therefore, the Malaysian and Singaporean Buddhists largely described the relationship between science and religion as one of compatibility.

Indeed, even when prompted to think about potential areas of scientific research that raised concerns for religious reasons, relatively few of the Buddhists mentioned any. Among those who did cite a concern, a common response involved animal testing. Buddhist interviewees talked about the importance of not killing living things in the practice of their religion, so some felt that research that causes harm or death to animals is worrisome.

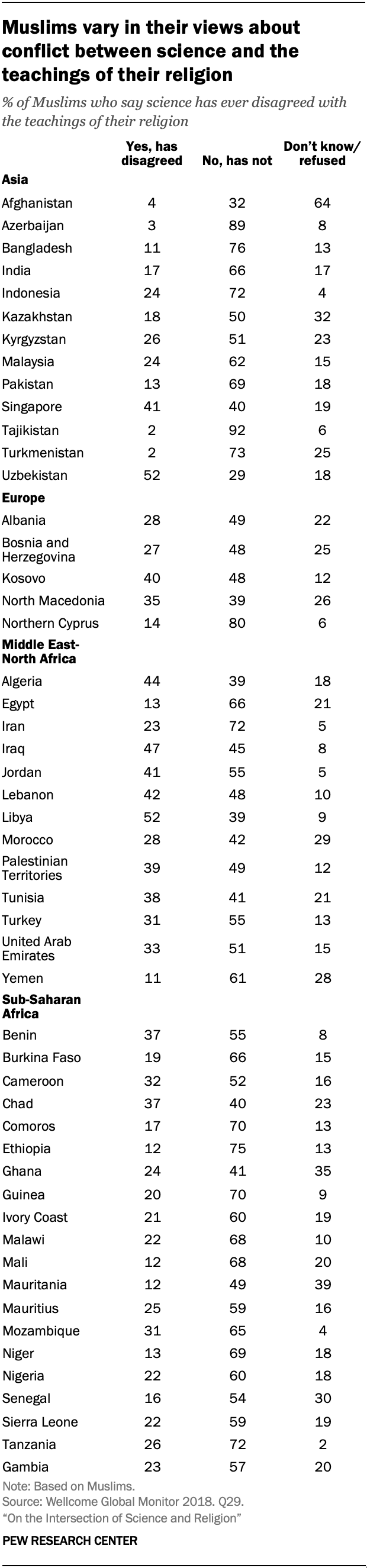

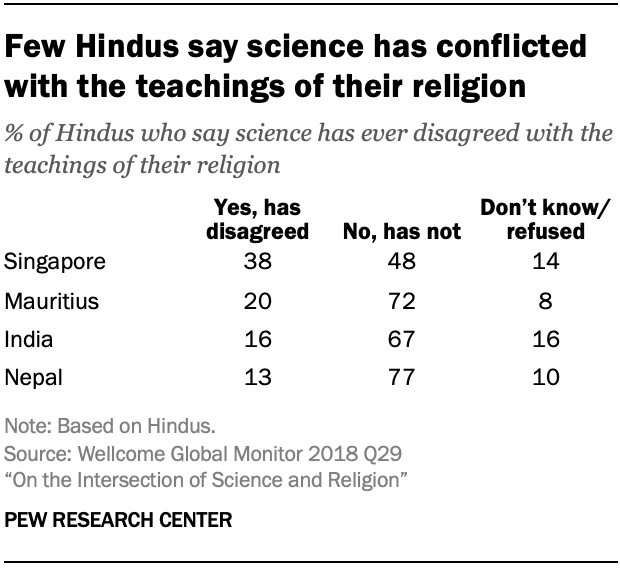

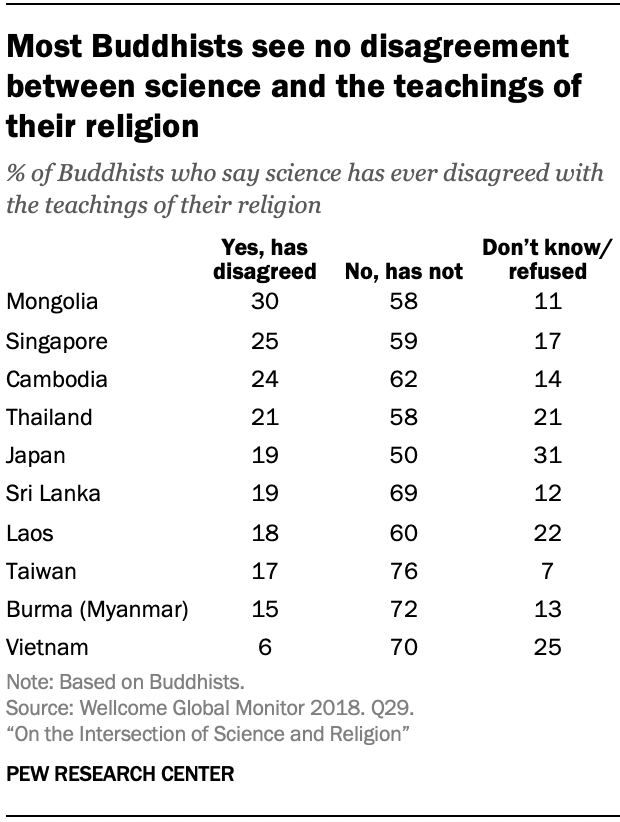

The tenor of these comments is consistent with survey findings from the 2018 Wellcome Global Monitor. Majorities of Buddhists in all 10 countries with large enough samples for analysis said that science has “never disagreed” with the teachings of their religion. 3 This includes 59% of Buddhists in Singapore. (In Malaysia, 55% of Buddhists said the same. However, these results should be interpreted with extra caution because there were just 129 Malaysian Buddhists in the survey sample.) Far smaller shares of Buddhists in these countries see a conflict between science and their religion’s teachings.

Surveys among Christians find wide variation in perceptions of conflict between religion and science though more see at least some conflict than do not

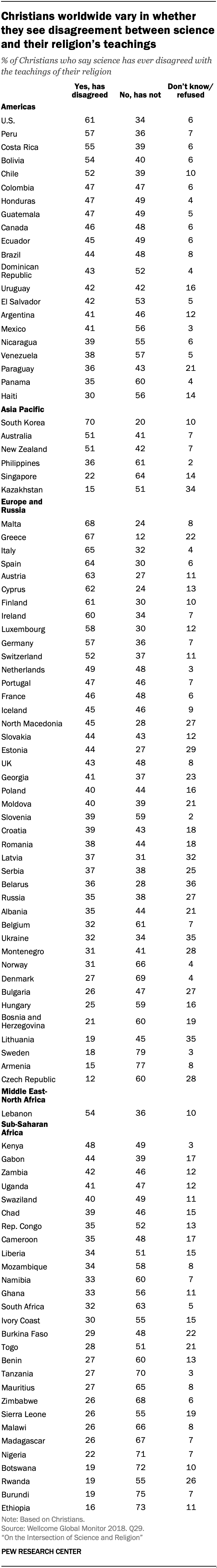

For comparison, representative surveys of Christians around the world also find widely ranging views about whether religion and science have ever disagreed or are generally in conflict. The 2018 Wellcome Global Monitor survey finds wide variation in Christians’ views on this issue. 4 The U.S. stands out, along with several southern European nations, for its relatively high share of Christians reporting that science has disagreed with the teachings of their religion (61%). By contrast, 22% in Singapore, 18% in Sweden and 12% in the Czech Republic say the same.

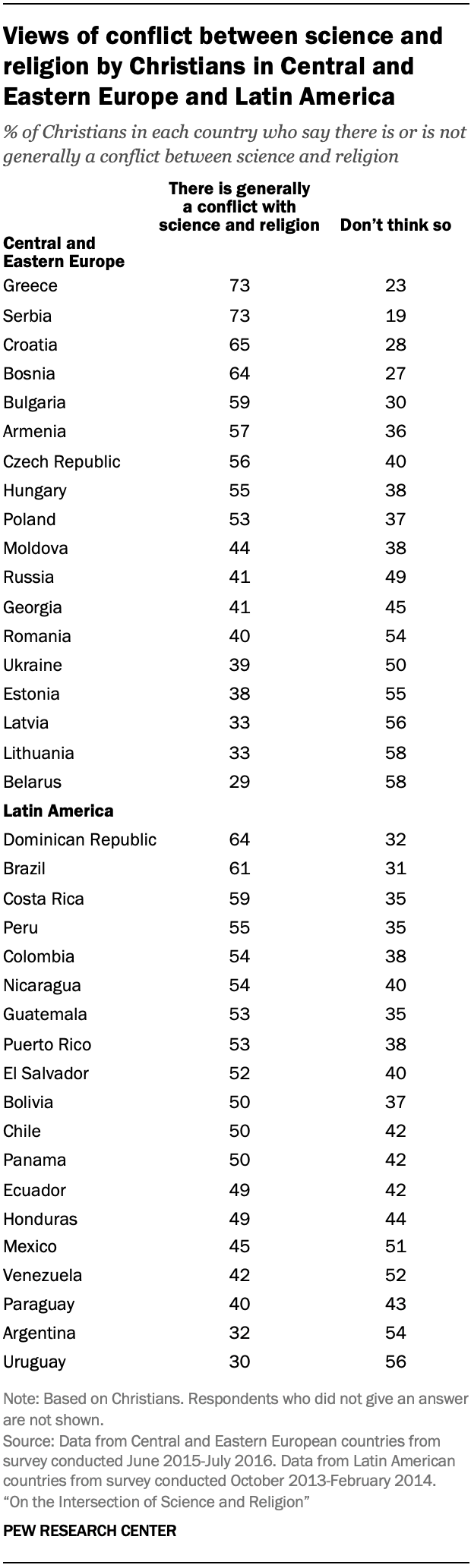

Pew Research Center surveys asked a similar question in Central and Eastern Europe as well as in Latin America . Christians in these regions tilt toward saying that “there is generally a conflict between science and religion.” A median of 49% of Christians in Central and Eastern Europe say there is generally a conflict, and a median of 39% say there is not. The median view on this question in Latin American was similar (50% to 40%).

In a U.S.-based Pew Research Center survey , a majority of Christians (55%) said that science and religion are “often in conflict” when thinking in general terms about religion. When thinking about their own religious beliefs, however, fewer Christians (35%) said their personal religious beliefs sometimes conflict with science; a majority of U.S. Christians (63%) said the two do not conflict.

Such findings broadly align with Elaine Howard Ecklund and Christopher P. Scheitle’s analysis in “Religion vs. Science: What Religious People Really Think,” which finds that many U.S. Christians see little conflict between science and their faith.

This survey also provides a window into the kinds of things that Christians see as a conflict between science and religion. In an open-ended question included on the Center’s survey, respondents who said science conflicted with their personal religious beliefs were asked to identify up to three areas of conflict. Christians most commonly mentioned the creation of the universe, including evolution and the “Big Bang” (cited by 38% of U.S. Christians who saw a conflict between science and their religious beliefs). Respondents also mentioned broad tensions including the idea that man (rather than God) is “in charge,” beliefs in miracles, or a belief in the events of the Bible (26%). Others cited conflict over the beginning of life, abortion, and scientific technologies involving human embryos (12%) or other medical practices (7%).

Evolution is a more frequent point of conflict for those in Abrahamic faiths such as Islam and Christianity

Evolution raised areas of disagreement for many Muslim interviewees, who often said the theory of evolution is incompatible with the Islamic tenet that humans were created by Allah. Evolution is also a common, though by no means universal, friction point for Christians. By contrast, neither Buddhist interviewees, followers of a religion with no creator figure, nor Hindu interviewees, followers of a polytheistic faith, described discord with evolution either in their personal beliefs or in their views of how evolution comports with their religion.

Some Muslims interviewees see origination of humans from the prophet Nabi Adam as at odds with evolution

When asked about the theory of evolution, Muslim interviewees generally talked about conflict between the theory of evolution and their religious beliefs about the origins of human life – specifically, the belief that God created humans in their present form, and that all humans are descended from Adam and Eve. “This is one of the conflicts between religion and Western theory. Based on Western theory, they said we came from monkeys. For me, if we evolved from monkeys, where could we get the stories of [the prophet] Nabi? Was Nabi Muhammad like a monkey in the past? For me, he was human. Allah had created perfect humans, not from monkey to human,” said one Muslim man (age 21, Malaysia).

Islamic views on evolution

“Nonsense. I believe that Nabi Adam is the first human in the world. Before Nabi Adam was created, other living things such as dinosaurs and so on were also created. The theory of human evolution from apes to human is very different from the teaching in Islam.” – Muslim man, age 24, Malaysia

“That theory to me is absurd. People might be saying that during time of Mesopotamia, the people there hunch and bow, with appearance looking like an ape. Maybe that is why one says we come from apes. But, for me, I believe that we come from Adam and Adam came from heaven.” – Muslim woman, age 36, Malaysia

“Our ancestors are not monkeys. Maybe there’s similarity in the DNA, but in Islam the first human is Adam. He’s not a monkey.” – Muslim man, age 35, Singapore

Others emphasized that evolution is only a theory and has not been proven true. “It’s just a theory, because there is no specific evidence or justification. … Just because the DNA [of humans and primates] has a difference of a few percent, that doesn’t mean we are similar,” said a 29-year-old Singaporean Muslim man. Still others said that Charles Darwin developed this theory in order to get famous and did not put adequate thought or research into his theory.

However, a handful of Muslims said they personally believed that humans were descended from primates via the evolutionary process, even though they believed that this deviated from Islamic teaching. “Monkeys can crawl. After that, stand, stand, stand, then become human, right? Yes, I think so. I think, yeah, that one I believe. … [But] religion says all humans in the world come from God. A bit of conflict,” said a 44-year-old Muslim woman from Singapore. Another Muslim woman (age 39, Singapore) said she was open to the concept of evolution, even though her religion tells a different story. “According to religion, we don’t originate from monkeys. But being that we may be related, the possibility is there,” she said.

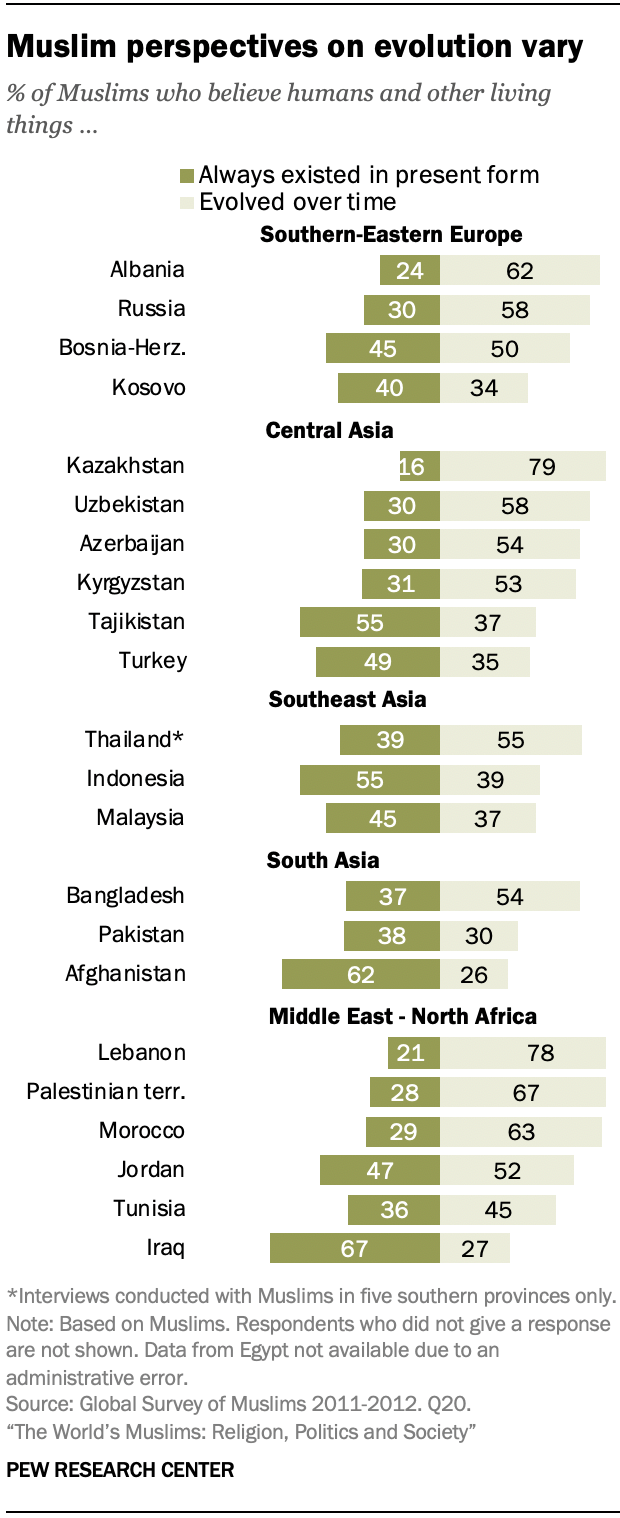

A Pew Research Center survey of Muslims worldwide conducted in 2011 and 2012 found a 22-public median of 53% said they believed humans and other living things evolved over time. However, levels of acceptance of evolution varied by region and country, with Muslims in South and Southeast Asian countries reporting lower levels of belief in evolution by this measure than Muslims in other regions. In Malaysia, for instance, 37% of Muslim adults said they believed humans and other living things evolved over time.

In the U.S. context, a 2011 Pew Research Center survey found that views of evolution among American Muslims were roughly split: 45% said they believed humans and other living things have evolved over time, while 44% said they have existed in their present form since the beginning of time.

Hindu and Buddhist interviewees emphasize the absence of conflict with the theory of evolution

Evolution posed no conflict to the Hindus interviewed. In keeping with thematic comments that Hinduism contains elements of science, many interviewees said the concept of evolution was encompassed in their religious teachings. “In Hinduism we have something like this as well, that tells us we originated from different species, which is why we also believe in reincarnation, and how certain deities take different forms. This is why certain animals are seen as sacred animals, because it’s one of the forms that this particular deity had taken,” said a 29-year-old Hindu woman in Singapore. When asked about the origins of human life, many Hindu interviewees just quickly replied that humans came from primates.

The Buddhists interviewed also tended to say there was no conflict between their religion and evolution, and that they personally believed in the theory. Some added that they didn’t think their religion addressed humans’ origins at all. “I don’t think Buddhism has any theory on the first human being or anything. For Buddhism, we don’t really have a strong sense of how the first human came along,” said a Buddhist man in Singapore (age 22).

Hindu views on evolution

“I don’t think evolution has anything to do with religion, nothing to do with Hinduism. That was just adaptation. For example, apes to men. It was just adaptation that people eventually changed over time.” – Hindu man, age 26, Singapore

“The concept (of evolution) is the same. The Hindus say it in a different way, and modern science says it in a scientific way.” – Hindu woman, age 27, Malaysia

Buddhist views on evolution

“[Buddhism says] we are all made out of the atoms and molecules, not that we are created by God. Like Christians believe that we are created by God, but no, I as a practicing Buddhist do not believe in that.” – Buddhist woman, age 60, Malaysia

There is limited global survey data on this issue. However, Pew Research Center’s 2014 Religious Landscape Study found that 86% of Buddhists and 80% of Hindus in the U.S. said that humans and other living things have evolved over time, with majorities also saying this was due to natural processes.

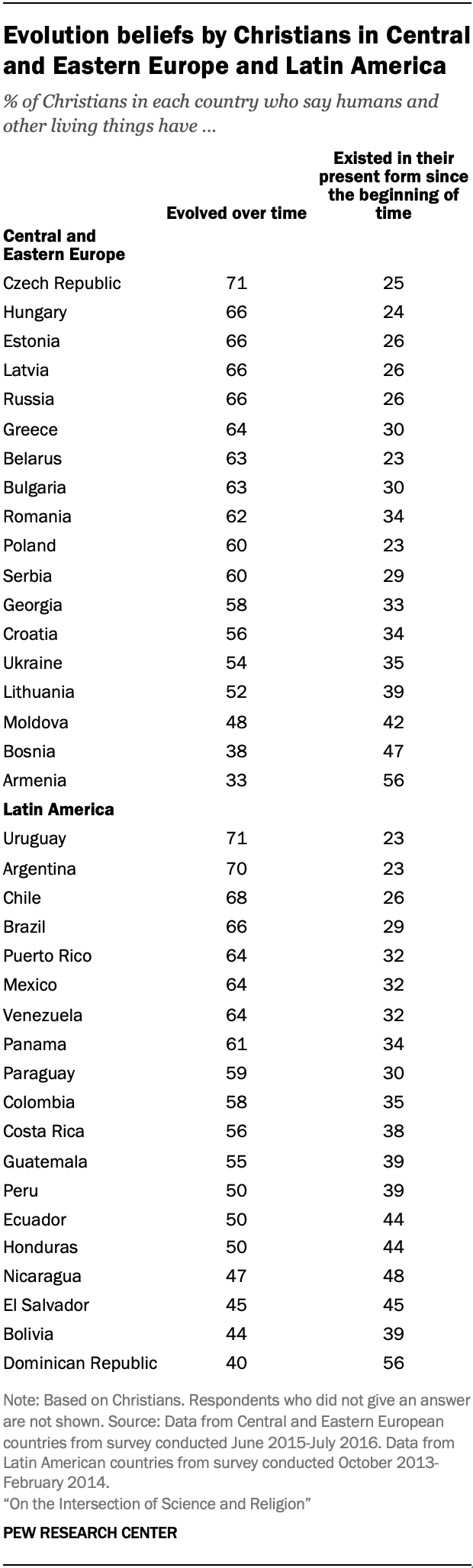

Surveys of Christians globally find that majorities in most publics surveyed accept the idea that humans and other living things have evolved over time

Pew Research Center surveys conducted in Central and Eastern Europe and Latin America find that a majority of Christians in most countries in these regions say humans and other living things have evolved over time. An 18-country median of 61% of Christians say this in Central and Eastern Europe, while a median of 30% say instead that humans and other living things have existed in their present form since the beginning of time. The median views on this issue are similar in Latin America (59% and 35%, respectively).

Views of American Christians are about the same as those global medians: 58% in a 2018 Pew Research Center survey said that humans and other living things have evolved over time, while 42% said they have always existed in their current form.

People’s responses to questions about evolution can vary depending on how the question is asked , however. Specifically, a 2018 Pew Research Center survey focusing on beliefs about the origins of humans found more white evangelical Protestants, Black Protestants and Catholics expressed a belief in evolution when given the option to say that humans evolved with guidance from God or a higher power .

Such differences in how Christians see the issue of evolution are broadly consistent with an analysis by Fern Elsdon-Baker and her research completed with colleagues in the UK and Canada, which suggest that people’s views on evolution can be nuanced, depending on the exact questions asked.

Interviewees across Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist groups cite tension with research that “goes against nature” or involves harm to animals

Two areas of potential conflict with science cut across religious groups. Interviewees from all three groups raised concerns about scientific research that interferes with nature in some way or that causes harm to animals.

Views on animal welfare and scientific research

“When we do scientific research, we just have to ensure we did not endanger other living things, including animals and humans. We don’t bring harm to any of the people, that is the basic moral value.” – Hindu man, age 22, Malaysia

“In Islam, for example, you shouldn’t subject any human or animals to cruelty. So, I believe if you want to do any testing on rats, you need to ask yourself: “Will the rats suffer?’” – Muslim man, age 59, Singapore

In discussing scientific research using gene editing, cloning and reproductive technologies such as in vitro fertilization, Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist interviewees raised the idea that such practices may go against the natural order or interfere with nature. As one Buddhist man simply put it: “If you have anything that interferes with the law of nature, you will have conflict. If you leave nature alone, you will have no conflict” (age 64, Singapore). Similarly, a Muslim woman said “anything that disrupts or changes the natural state” goes against religious beliefs (age 20, Singapore).

When probed about potential areas of scientific research that should be “off limits” from a religious perspective, individuals from all three religious groups talked about the need to consider animal welfare (and sometimes human welfare) in scientific research. This idea occasionally came up when interviewees were asked for their thoughts about cloning and gene editing; others mentioned animal welfare concerns at other points of the interview, along with the need for ethical treatment of living things in general. Buddhists and Hindus in particular emphasized the need to “do no harm” when probed about characteristics that make someone a good follower of their religions.

A few interviewees thought one other topic should be off limits to scientific exploration: research aimed at core beliefs such as the existence of God, the heavens or holy scripture.

Touchpoints between religion and biotechnology research areas

Interviewees were asked to talk about their awareness of and views about each of three specific research areas in biotechnology – new technologies to help women get pregnant, gene editing for babies, and animal cloning. People had generally positive views of pregnancy technology such as in vitro fertilization, although Muslim interviewees pointed out potential objections depending on how these techniques are used. Views of gene editing and cloning were more wide-ranging, with no particular patterns associated with the religious affiliation of the interviewees.

Individuals from all three religions generally approved of pregnancy technology and in vitro fertilization

The first scientific development raised for discussion involved technologies to help women get pregnant. Interviewees often volunteered that they were familiar with in vitro fertilization, commonly referred to as IVF, which is an assisted reproductive technology. Individuals who expressed positive views about IVF mentioned things pertaining to the help it brings to people trying to conceive in modern times. Some even surmised that IVF itself or the knowledge to develop it was a gift from God.

Buddhists and Hindus on IVF

“I don’t think my religion would have any comments on [IVF and surrogacy]. I think Christians would have more comments on it. Like the very staunch Christians, they think that they can’t do this and that. They are very specific.” – Buddhist woman, age 26, Singapore

“It’s a good thing. Some couples don’t have the chance to get babies. With these technologies, people are finding happiness.” – Hindu man, age 24, Malaysia

Muslims accept pregnancy technologies, with conditions

“You cannot use another person to carry your baby, but people want their own flesh-and-blood baby. So, [IVF] is a really good opportunity. Because otherwise people usually just adopt, and it’s not their flesh and blood. They don’t want that.” – Muslim woman, age 24, Singapore

“In my opinion, IVF does not have any conflict with the religion because it helps to continue the descendants and it involves the correct and qualified person. … The man should be the person who is qualified and marry the woman, and the wife should be the person who is qualified to receive the fetus from the man.” – Muslim man, age 24, Malaysia

“For that particular woman to perform this scientific procedure, the company that executes this procedure must make sure that the woman has a certificate of marriage, meaning legitimately married. I think it is that simple. If she is not married, but she wants (to perform this procedure), I don’t think the company should do it. It is immoral.” – Muslim man, age 36, Malaysia

Even among supporters of these technologies, one common sentiment was that people were either unsure of where their religion stood on this issue or thought that other people – those who were older, more conservative or more religious – might be against it. “I think the old-timers are having a bit of a difficult time with being OK with [IVF]. The young generation, my generation, and the ones younger are OK with this,” said one Hindu man (age 26, Singapore).

Some Hindus and Buddhists noted that they were comfortable with pregnancy technologies themselves, but said that there is pushback from other religions, particularly Islam and Christianity. For instance, when asked about IVF, one Buddhist man said, “Oh, wow, that’s a very good question. Controversy, right? I heard about such before, I think, especially coming from Christianity. But, my personal take, I feel it is fine. It’s still trying to get the balance of being a believer of a religion vs. overly superstitious or believing too much in that religion that you forgo the reality of life going on” (Singapore, age 37). Another noted that Buddhism and Hinduism don’t have the same staunch views on IVF as Muslims. “In Buddhism, we don’t have this type of restriction. It’s totally different from other [religions], if I’m not wrong. If you talk about Muslims, there is. If you talk about Hindus, I think also they don’t,” he said (age 43, Singapore).

Muslim interviewees tended to accept technologies to facilitate pregnancy. However, some Muslims emphasized that they would only be OK with these technologies if certain criteria were met – specifically, if the technologies were used by married couples, and with the couples’ own genetic material. “IVF is fine with me because it uses the couple’s egg and sperm and the mother’s body. You need help inseminating the egg, that’s all,” said one Muslim man (age 59, Singapore). Some Muslims also expressed concern about surrogacy in particular; they said Islam prohibits bringing outside parties into a marriage, and that surrogacy is effectively having a third person enter the marriage. A few other Muslims in the study mentioned the need to consult edicts or talk with leaders in the religious community before they would be able to be fully supportive, a common practice for many controversial issues in Islam.

Opinions varied widely on gene editing and animal cloning

Interviewees, regardless of their religion, said the idea of curing a baby of disease before birth or preventing a disease that a child could develop later in life would be a helpful, acceptable use of gene editing. But they often viewed gene editing for cosmetic reasons much more negatively.

Views on gene editing vary depending on how it is used

“I think science and technology aims to help the people. If you modify the baby, it is not good for them. The baby might also not want what the parents edited. In terms of the treatment of diseases, I think is good, as you can cure the baby.” – Buddhist man, age 23, Malaysia

“I like one half of it, the other half I don’t like. The half that I like was eliminating the diseases. The part where you can make the eye color and all that? I wouldn’t say I’m against it, but I’m definitely not up for it.” – Hindu woman, age 40, Singapore

Muslims’ concerns with “playing God”

“Cloning, to put it simply, you’re delving into an area where you’re playing God. It is concerning because if it’s taken as something that’s normal, it means that humans can do things that previously no one could do. That means we could create ourselves. That goes against the beliefs that I have, because as a Muslim, while we have the ability to do certain things, it does not mean that we should do those things.” – Muslim man, age 29, Singapore

Several interviewees brought up the idea of not agreeing with gene editing out of fear that people might want to Westernize their children. For example, some repeated the concern that gene editing would be used to create babies with blond hair and blue eyes. “In terms of the diseases, I think it is acceptable. If they want to change the hair or eyes color? We are not European people,” said one Muslim woman (age 47, Malaysia).

Views of cloning were similarly conditional. Individuals from all three religions remarked on their disapproval of cloning for humans. But interviewees generally found animal cloning to be a much more acceptable practice. Many people interviewed envisioned useful outcomes for society from animal cloning, such as providing meat to feed more people, or to help preserve nearly extinct animals. For example, a Hindu woman said, cloning “is a good idea because some of the animals, like tigers, are on the brink of extinction, so I think it is good to clone before they are extinct” (age 27, Malaysia).

Many of the issues raised about gene editing and cloning mirrored each other. Some of the concerns were based on religious traditions and values. For example, primarily Muslim interviewees mentioned that cloning could interfere with the power of God, who should be the only one who can create.

To the extent Hindus and Buddhists in the study expressed religious concerns pertaining to gene editing and cloning, they generally brought up the idea that these scientific methods might interfere with karma or reincarnation. (Some interviewees also mentioned the potential of IVF to interfere with karma, but they were generally less concerned about this.) One Buddhist woman, talking about gene editing, said: “Sometimes the person is born with sufferings, and it is because maybe previously he had been doing some evil things” (age 45, Singapore). When asked about cloning, a Hindu man expressed similar views. “For Hinduism, we believe that how we look like, how we are, our hands and our legs, it’s because of our past life. So, for example, they will always say that if I am handsome and I’m smart, it’s because in my past life I actually was a nicer person to people. Because of karma, because of reincarnation, I was born back into the better person” (Hindu man, age 25, Singapore).

Religious differences fade as interviewees think about the value of government investments in scientific research

Not all aspects of science are seen through a religious lens. Regardless of their religion, the people we spoke with overwhelmingly described investment in scientific research, including medicine, engineering and technology, as worthwhile. Malaysians and Singaporeans alike broadly shared this feeling.

Support for investment in scientific research

“I think it is very, very worth investing because the research is not just gathering information and data, but indirectly it creates job opportunities for the future. These would be very useful for the future and it can directly help a country to develop.” – Muslim man, age 33, Malaysia

“For me, engineering and technology investment is worthwhile because we want to be comparable to other advanced countries.” – Muslim man, age 21, Malaysia

“It’s never enough [investment], because the more we do, the better results we’ll get. … Maybe one day there would be a cure for cancer in a very easy way. Maybe they will be able to detect mental illnesses through scans. If that is possible through research, it will be a breakthrough for a lot of people.” – Hindu man, age 38, Singapore

On scientific research and national prestige

“If we do something that no other countries have been doing, we can make good money out of it and we can be a pioneer in that field. A lot of Malaysians have been contributing their ideas to other countries, but not to their own country. … So why not we do it for our own country, and get a name for Malaysia, and get famous.” – Hindu woman, age 29, Malaysia

In both countries, interviewees described government investment in science as a way to encourage economic development while also improving the lives of everyday people. People often were particularly enthusiastic about government investment in medicine and spoke of its potential to improve their country’s medical infrastructure and care for an aging population.

But others expressed some hesitation about government investment because they felt their government wasn’t doing a good job of ensuring that the research produced meaningful results, or because they thought the research didn’t benefit the public directly. “If there’s results, then it will be worthwhile. … I don’t think [there are results] because I’ve never heard anybody say ‘Wow, Singapore has discovered a new drug,’” said one Buddhist woman (Singapore, 26). Some interviewees also said they supported government investment in medical research, but that they thought the private sector could take care of investment in engineering or technology.

Malaysians also mentioned that a sense of national pride or prestige could come from government investment in science and the subsequent achievements. For example, one Buddhist woman (age 29) said research on medicine and technology could help Malaysia “become famous compared with other countries.” A Hindu man, 24, said he hoped the government would increase its spending on engineering and technology, because it would provide more jobs and show that Malaysia is a high-achieving country. He said more investment would “[help] a lot of people to achieve their dreams. You are putting Malaysia in the top table.” Another Malaysian man expressed a similar sentiment, saying: “For me, engineering and technology investment is worthwhile because we want to be comparable to other advanced countries” (Muslim, age 21).

We appreciate the thoughtful comments and guidance from Sharon Suh, Ajay Verghese and Pew Research Center religion experts including Besheer Mohamed, Neha Sahgal and Director of Religion Research Alan Cooperman on an earlier draft of this essay.

We greatly benefited from Mike Lipka’s editorial guidance, graphic design from Bill Webster, and copy editing from Aleksandra Sandstrom.

- Based on Pew Research Center analysis of the 2018 Wellcome Global Monitor for all countries with at least 150 Muslim respondents in the survey sample. ↩

- Based on Pew Research Center analysis of the 2018 Wellcome Global Monitor for all countries with at least 150 Hindu respondents in the survey sample. ↩

- Based on Pew Research Center analysis of the 2018 Wellcome Global Monitor for all countries with at least 150 Buddhist respondents in the survey sample. ↩

- Based on Pew Research Center analysis of the 2018 Wellcome Global Monitor for all countries with at least 150 Christian respondents in the survey sample. ↩

- A similar perspective emerged from interviews with religious leaders in a 2016 Pew Research Center study about the possibility of using biotechnological interventions to augment human capabilities. To take one example, Lutheran theologian Ted Peters expected many mainline Protestant churches to see such developments positively because “I think they will see much of this for what it is: an effort to take advantage of these new technologies to help improve human life,” he said. ↩

Sign up for our Religion newsletter

Sent weekly on Wednesday

About Pew Research Center Pew Research Center is a nonpartisan fact tank that informs the public about the issues, attitudes and trends shaping the world. It conducts public opinion polling, demographic research, media content analysis and other empirical social science research. Pew Research Center does not take policy positions. It is a subsidiary of The Pew Charitable Trusts .

- Table of Contents

- Random Entry

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Advanced Tools

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

Religion and Science

The relationship between religion and science is the subject of continued debate in philosophy and theology. To what extent are religion and science compatible? Are religious beliefs sometimes conducive to science, or do they inevitably pose obstacles to scientific inquiry? The interdisciplinary field of “science and religion”, also called “theology and science”, aims to answer these and other questions. It studies historical and contemporary interactions between these fields, and provides philosophical analyses of how they interrelate.

This entry provides an overview of the topics and discussions in science and religion. Section 1 outlines the scope of both fields, and how they are related. Section 2 looks at the relationship between science and religion in five religious traditions, Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism. Section 3 discusses contemporary topics of scientific inquiry in which science and religion intersect, focusing on divine action, creation, and human origins.

1.1 A brief history

1.2 what is science, and what is religion, 1.3 taxonomies of the interaction between science and religion, 1.4 the scientific study of religion, 2.1 christianity, 2.3 hinduism, 2.4 buddhism, 2.5 judaism, 3.1 divine action and creation, 3.2 human origins, works cited, other important works, other internet resources, related entries, 1. science, religion, and how they interrelate.

Since the 1960s, scholars in theology, philosophy, history, and the sciences have studied the relationship between science and religion. Science and religion is a recognized field of study with dedicated journals (e.g., Zygon: Journal of Religion and Science ), academic chairs (e.g., the Andreas Idreos Professor of Science and Religion at Oxford University), scholarly societies (e.g., the Science and Religion Forum), and recurring conferences (e.g., the European Society for the Study of Science and Theology’s biennial meetings). Most of its authors are theologians (e.g., John Haught, Sarah Coakley), philosophers with an interest in science (e.g., Nancey Murphy), or (former) scientists with long-standing interests in religion, some of whom are also ordained clergy (e.g., the physicist John Polkinghorne, the molecular biophysicist Alister McGrath, and the atmospheric scientist Katharine Hayhoe). Recently, authors in science and religion also have degrees in that interdisciplinary field (e.g., Sarah Lane Ritchie).

The systematic study of science and religion started in the 1960s, with authors such as Ian Barbour (1966) and Thomas F. Torrance (1969) who challenged the prevailing view that science and religion were either at war or indifferent to each other. Barbour’s Issues in Science and Religion (1966) set out several enduring themes of the field, including a comparison of methodology and theory in both fields. Zygon, the first specialist journal on science and religion, was also founded in 1966. While the early study of science and religion focused on methodological issues, authors from the late 1980s to the 2000s developed contextual approaches, including detailed historical examinations of the relationship between science and religion (e.g., Brooke 1991). Peter Harrison (1998) challenged the warfare model by arguing that Protestant theological conceptions of nature and humanity helped to give rise to science in the seventeenth century. Peter Bowler (2001, 2009) drew attention to a broad movement of liberal Christians and evolutionists in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries who aimed to reconcile evolutionary theory with religious belief. In the 1990s, the Vatican Observatory (Castel Gandolfo, Italy) and the Center for Theology and the Natural Sciences (Berkeley, California) co-sponsored a series of conferences on divine action and how it can be understood in the light of various contemporary sciences. This resulted in six edited volumes (see Russell, Murphy, & Stoeger 2008 for a book-length summary of the findings of this project).

The field has presently diversified so much that contemporary discussions on religion and science tend to focus on specific disciplines and questions. Rather than ask if religion and science (broadly speaking) are compatible, productive questions focus on specific topics. For example, Buddhist modernists (see section 2.4 ) have argued that Buddhist theories about the self (the no-self) and Buddhist practices, such as mindfulness meditation, are compatible and are corroborated by neuroscience.

In the contemporary public sphere, a prominent interaction between science and religion concerns evolutionary theory and creationism/Intelligent Design. The legal battles (e.g., the Kitzmiller versus Dover trial in 2005) and lobbying surrounding the teaching of evolution and creationism in American schools suggest there’s a conflict between religion and science. However, even if one were to focus on the reception of evolutionary theory, the relationship between religion and science is complex. For instance, in the United Kingdom, scientists, clergy, and popular writers (the so-called Modernists), sought to reconcile science and religion during the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, whereas the US saw the rise of a fundamentalist opposition to evolutionary thinking, exemplified by the Scopes trial in 1925 (Bowler 2001, 2009).

Another prominent offshoot of the discussion on science and religion is the New Atheist movement, with authors such as Richard Dawkins, Sam Harris, Daniel Dennett, and Christopher Hitchens. They argue that public life, including government, education, and policy should be guided by rational argument and scientific evidence, and that any form of supernaturalism (especially religion, but also, e.g., astrology) has no place in public life. They treat religious claims, such as the existence of God, as testable scientific hypotheses (see, e.g., Dawkins 2006).

In recent decades, the leaders of some Christian churches have issued conciliatory public statements on evolutionary theory. Pope John Paul II (1996) affirmed evolutionary theory in his message to the Pontifical Academy of Sciences, but rejected it for the human soul, which he saw as the result of a separate, special creation. The Church of England publicly endorsed evolutionary theory (e.g., C. M. Brown 2008), including an apology to Charles Darwin for its initial rejection of his theory.

This entry will focus on the relationship between religious and scientific ideas as rather abstract philosophical positions, rather than as practices. However, this relationship has a large practical impact on the lives of religious people and scientists (including those who are both scientists and religious believers). A rich sociological literature indicates the complexity of these interactions, among others, how religious scientists conceive of this relationship (for recent reviews, see Ecklund 2010, 2021; Ecklund & Scheitle 2007; Gross & Simmons 2009).

For the past fifty years, the discussion on science and religion has de facto been on Western science and Christianity: to what extent can the findings of Western sciences be reconciled with Christian beliefs? The field of science and religion has only recently turned to an examination of non-Christian traditions, providing a richer picture of interaction.

In order to understand the scope of science and religion and their interactions, we must at least get a rough sense of what science and religion are. After all, “science” and “religion” are not eternally unchanging terms with unambiguous meanings. Indeed, they are terms that were coined recently, with meanings that vary across contexts. Before the nineteenth century, the term “religion” was rarely used. For a medieval author such as Aquinas, the term religio meant piety or worship, and was not applied to religious systems outside of what he considered orthodoxy (Harrison 2015). The term “religion” obtained its considerably broader current meaning through the works of early anthropologists, such as E.B. Tylor (1871), who systematically used the term for religions across the world. As a result, “religion” became a comparative concept, referring to traits that could be compared and scientifically studied, such as rituals, dietary restrictions, and belief systems (Jonathan Smith 1998).

The term “science” as it is currently used also became common in the nineteenth century. Prior to this, what we call “science” fell under the terminology of “natural philosophy” or, if the experimental part was emphasized, “experimental philosophy”. William Whewell (1834) standardized the term “scientist” to refer to practitioners of diverse natural philosophies. Philosophers of science have attempted to demarcate science from other knowledge-seeking endeavors, in particular religion. For instance, Karl Popper (1959) claimed that scientific hypotheses (unlike religious and philosophical ones) are in principle falsifiable. Many authors (e.g., Taylor 1996) affirm a disparity between science and religion, even if the meanings of both terms are historically contingent. They disagree, however, on how to precisely (and across times and cultures) demarcate the two domains.

One way to distinguish between science and religion is the claim that science concerns the natural world, whereas religion concerns the supernatural world and its relationship to the natural. Scientific explanations do not appeal to supernatural entities such as gods or angels (fallen or not), or to non-natural forces (such as miracles, karma, or qi ). For example, neuroscientists typically explain our thoughts in terms of brain states, not by reference to an immaterial soul or spirit, and legal scholars do not invoke karmic load when discussing why people commit crimes.

Naturalists draw a distinction between methodological naturalism , an epistemological principle that limits scientific inquiry to natural entities and laws, and ontological or philosophical naturalism , a metaphysical principle that rejects the supernatural (Forrest 2000). Since methodological naturalism is concerned with the practice of science (in particular, with the kinds of entities and processes that are invoked), it does not make any statements about whether or not supernatural entities exist. They might exist, but lie outside of the scope of scientific investigation. Some authors (e.g., Rosenberg 2014) hold that taking the results of science seriously entails negative answers to such persistent questions into the existence of free will or moral knowledge. However, these stronger conclusions are controversial.

The view that science can be demarcated from religion in its methodological naturalism is more commonly accepted. For instance, in the Kitzmiller versus Dover trial, the philosopher of science Robert Pennock was called to testify by the plaintiffs on whether Intelligent Design was a form of creationism, and therefore religion. If it were, the Dover school board policy would violate the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Building on earlier work (e.g., Pennock 1998), Pennock argued that Intelligent Design, in its appeal to supernatural mechanisms, was not methodologically naturalistic, and that methodological naturalism is an essential component of science.

Methodological naturalism is a recent development in the history of science, though we can see precursors of it in medieval authors such as Aquinas who attempted to draw a theological distinction between miracles, such as the working of relics, and unusual natural phenomena, such as magnetism and the tides (see Perry & Ritchie 2018). Natural and experimental philosophers such as Isaac Newton, Johannes Kepler, Robert Hooke, and Robert Boyle regularly appealed to supernatural agents in their natural philosophy (which we now call “science”). Still, overall there was a tendency to favor naturalistic explanations in natural philosophy. The X-club was a lobby group for the professionalization of science founded in 1864 by Thomas Huxley and friends. While the X-club may have been in part motivated by the desire to remove competition by amateur-clergymen scientists in the field of science, and thus to open up the field to full-time professionals, its explicit aim was to promote a science that would be free from religious dogma (Garwood 2008, Barton 2018). This preference for naturalistic causes may have been encouraged by past successes of naturalistic explanations, leading authors such as Paul Draper (2005) to argue that the success of methodological naturalism could be evidence for ontological naturalism.

Several typologies probe the interaction between science and religion. For example, Mikael Stenmark (2004) distinguishes between three views: the independence view (no overlap between science and religion), the contact view (some overlap between the fields), and a union of the domains of science and religion; within these views he recognizes further subdivisions, e.g., contact can be in the form of conflict or harmony. The most influential taxonomy of the relationship between science and religion remains Barbour’s (2000): conflict, independence, dialogue, and integration. Subsequent authors, as well as Barbour himself, have refined and amended this taxonomy. However, others (e.g., Cantor & Kenny 2001) have argued that this taxonomy is not useful to understand past interactions between both fields. Nevertheless, because of its enduring influence, it is still worthwhile to discuss it in detail.

The conflict model holds that science and religion are in perpetual and principal conflict. It relies heavily on two historical narratives: the trial of Galileo (see Dawes 2016) and the reception of Darwinism (see Bowler 2001). Contrary to common conception, the conflict model did not originate in two seminal publications, namely John Draper’s (1874) History of the Conflict between Religion and Science and Andrew Dickson White’s (1896) two-volume opus A History of the Warfare of Science with Theology in Christendom . Rather, as James Ungureanu (2019) argues, the project of these early architects of the conflict thesis needs to be contextualized in a liberal Protestant tradition of attempting to separate religion from theology, and thus salvage religion. Their work was later appropriated by skeptics and atheists who used their arguments about the incompatibility of traditional theological views with science to argue for secularization, something Draper and White did not envisage.

The vast majority of authors in the science and religion field is critical of the conflict model and believes it is based on a shallow and partisan reading of the historical record. While the conflict model is at present a minority position, some have used philosophical argumentation (e.g., Philipse 2012) or have carefully re-examined historical evidence such as the Galileo trial (e.g., Dawes 2016) to argue for this model. Alvin Plantinga (2011) has argued that the conflict is not between science and religion, but between science and naturalism. In his Evolutionary Argument Against Naturalism (first formulated in 1993), Plantinga argues that naturalism is epistemically self-defeating: if both naturalism and evolution are true, then it’s unlikely we would have reliable cognitive faculties.

The independence model holds that science and religion explore separate domains that ask distinct questions. Stephen Jay Gould developed an influential independence model with his NOMA principle (“Non-Overlapping Magisteria”):

The lack of conflict between science and religion arises from a lack of overlap between their respective domains of professional expertise. (2001: 739)

He identified science’s areas of expertise as empirical questions about the constitution of the universe, and religion’s domain of expertise as ethical values and spiritual meaning. NOMA is both descriptive and normative: religious leaders should refrain from making factual claims about, for instance, evolutionary theory, just as scientists should not claim insight on moral matters. Gould held that there might be interactions at the borders of each magisterium, such as our responsibility toward other living things. One obvious problem with the independence model is that if religion were barred from making any statement of fact, it would be difficult to justify its claims of value and ethics. For example, one could not argue that one should love one’s neighbor because it pleases the creator (Worrall 2004). Moreover, religions do seem to make empirical claims, for example, that Jesus appeared after his death or that the early Hebrews passed through the parted waters of the Red Sea.

The dialogue model proposes a mutualistic relationship between religion and science. Unlike independence, it assumes a common ground between both fields, perhaps in their presuppositions, methods, and concepts. For example, the Christian doctrine of creation may have encouraged science by assuming that creation (being the product of a designer) is both intelligible and orderly, so one can expect there are laws that can be discovered. Creation, as a product of God’s free actions, is also contingent, so the laws of nature cannot be learned through a priori thinking which prompts the need for empirical investigation. According to Barbour (2000), both scientific and theological inquiry are theory-dependent, or at least model-dependent. For example, the doctrine of the Trinity colors how Christian theologians interpret the first chapters of Genesis. Next to this, both rely on metaphors and models. Both fields remain separate but they talk to each other, using common methods, concepts, and presuppositions. Wentzel van Huyssteen (1998) has argued for a dialogue position, proposing that science and religion can be in a graceful duet, based on their epistemological overlaps. The Partially Overlapping Magisteria (POMA) model defended by Alister McGrath (e.g., McGrath and Collicutt McGrath 2007) is also worth mentioning. According to McGrath, science and religion each draw on several different methodologies and approaches. These methods and approaches are different ways of knowing that have been shaped through historical factors. It is beneficial for scientists and theologians to be in dialogue with each other.

The integration model is more extensive in its unification of science and theology. Barbour (2000) identifies three forms of integration. First, natural theology, which formulates arguments for the existence and attributes of God. It uses interpretations of results from the natural sciences as premises in its arguments. For instance, the supposition that the universe has a temporal origin features in contemporary cosmological arguments for the existence of God. Likewise, the fact that the cosmological constants and laws of nature are life-permitting (whereas many other combinations of constants and laws would not permit life) is used in contemporary fine-tuning arguments (see the entry to fine-tuning arguments ). Second, theology of nature starts not from science but from a religious framework, and examines how this can enrich or even revise findings of the sciences. For example, McGrath (2016) developed a Christian theology of nature, examining how nature and scientific findings can be interpreted through a Christian lens. Thirdly, Barbour believed that Whitehead’s process philosophy was a promising way to integrate science and religion.

While integration seems attractive (especially to theologians), it is difficult to do justice to both the scientific and religious aspects of a given domain, especially given their complexities. For example, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin (1971), who was both knowledgeable in paleoanthropology and theology, ended up with an unconventional view of evolution as teleological (which put him at odds with the scientific establishment) and with an unorthodox theology (which denied original sin and led to a series of condemnations by the Roman Catholic Church). Theological heterodoxy, by itself, is no reason to doubt a model. However, it shows obstacles for the integration model to become a live option in the broader community of theologians and philosophers who want to remain affiliate to a specific religious community without transgressing its boundaries. Moreover, integration seems skewed towards theism: Barbour described arguments based on scientific results that support (but do not demonstrate) theism, but failed to discuss arguments based on scientific results that support (but do not demonstrate) the denial of theism. Hybrid positions like McGrath’s POMA indicate some difficulty for Barbour’s taxonomy: the scope of conflict, independence, dialogue, and integration is not clearly defined and they are not mutually exclusive. For example, if conflict is defined broadly then it is compatible with integration. Take the case of Frederick Tennant (1902), who sought to explain sin as the result of evolutionary pressures on human ancestors. This view led him to reject the Fall as a historical event, as it was not compatible with evolutionary biology. His view has conflict (as he saw Christian doctrine in conflict with evolutionary biology) but also integration (he sought to integrate the theological concept of sin in an evolutionary picture). It is clear that many positions defined by authors in the religion and science literature do not clearly fall within one of Barbour’s four domains.

Science and religion are closely interconnected in the scientific study of religion, which can be traced back to seventeenth-century natural histories of religion. Natural historians attempted to provide naturalistic explanations for human behavior and culture, including religion and morality. For example, Bernard Le Bovier de Fontenelle’s De l’Origine des Fables (1724) offered a causal account of belief in the supernatural. People often assert supernatural explanations when they lack an understanding of the natural causes underlying extraordinary events: “To the extent that one is more ignorant, or one has less experience, one sees more miracles” (1724 [1824: 295], my translation). Hume’s Natural History of Religion (1757) is perhaps the best-known philosophical example of a natural historical explanation of religious belief. It traces the origins of polytheism—which Hume thought was the earliest form of religious belief—to ignorance about natural causes combined with fear and apprehension about the environment. By deifying aspects of the environment, early humans tried to persuade or bribe the gods, thereby gaining a sense of control.

In the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, authors from newly emerging scientific disciplines, such as anthropology, sociology, and psychology examined the purported naturalistic roots of religious beliefs. They did so with a broad brush, trying to explain what unifies diverse religious beliefs across cultures. Auguste Comte (1841) proposed that all societies, in their attempts to make sense of the world, go through the same stages of development: the theological (religious) stage is the earliest phase, where religious explanations predominate, followed by the metaphysical stage (a non-intervening God), and culminating in the positive or scientific stage, marked by scientific explanations and empirical observations.

In anthropology, this positivist idea influenced cultural evolutionism, a theoretical framework that sought to explain cultural change using universal patterns. The underlying supposition was that all cultures evolve and progress along the same trajectory. Cultures with differing religious views were explained as being in different stages of their development. For example, Tylor (1871) regarded animism as the earliest form of religious belief. James Frazer’s Golden Bough (1890) is somewhat unusual within this literature, as he saw commonalities between magic, religion, and science. Though he proposed a linear progression, he also argued that a proto-scientific mindset gave rise to magical practices, including the discovery of regularities in nature. Cultural evolutionist models dealt poorly with religious diversity and with the complex relationships between science and religion across cultures. Many authors proposed that religion was just a stage in human development, which would eventually be superseded. For example, social theorists such as Karl Marx and Max Weber proposed versions of the secularization thesis, the view that religion would decline in the face of modern technology, science, and culture.

Functionalism was another theoretical framework that sought to explain religion. Functionalists did not consider religion to be a stage in human cultural development that would eventually be overcome. They saw it as a set of social institutions that served important functions in the societies they were part of. For example, the sociologist Émile Durkheim (1912 [1915]) argued that religious beliefs are social glue that helps to keep societies together.

Sigmund Freud and other early psychologists aimed to explain religion as the result of cognitive dispositions. For example, Freud (1927) saw religious belief as an illusion, a childlike yearning for a fatherly figure. He also considered “oceanic feeling” (a feeling of limitlessness and of being connected with the world, a concept he derived from the French author Romain Rolland) as one of the origins of religious belief. He thought this feeling was a remnant of an infant’s experience of the self, prior to being weaned off the breast. William James (1902) was interested in the psychological roots and the phenomenology of religious experiences, which he believed were the ultimate source of all institutional religions.

From the 1920s onward, the scientific study of religion became less concerned with grand unifying narratives, and focused more on particular religious traditions and beliefs. Anthropologists such as Edward Evans-Pritchard (1937) and Bronisław Malinowski (1925) no longer relied exclusively on second-hand reports (usually of poor quality and from distorted sources), but engaged in serious fieldwork. Their ethnographies indicated that cultural evolutionism was a defective theoretical framework and that religious beliefs were more diverse than was previously assumed. They argued that religious beliefs were not the result of ignorance of naturalistic mechanisms. For instance, Evans-Pritchard (1937) noted that the Azande were well aware that houses could collapse because termites ate away at their foundations, but they still appealed to witchcraft to explain why a particular house collapsed at a particular time. More recently, Cristine Legare et al. (2012) found that people in various cultures straightforwardly combine supernatural and natural explanations, for instance, South Africans are aware AIDS is caused by the HIV virus, but some also believe that the viral infection is ultimately caused by a witch.

Psychologists and sociologists of religion also began to doubt that religious beliefs were rooted in irrationality, psychopathology, and other atypical psychological states, as James (1902) and other early psychologists had assumed. In the US, in the late 1930s through the 1960s, psychologists developed a renewed interest for religion, fueled by the observation that religion refused to decline and seemed to undergo a substantial revival, thus casting doubt on the secularization thesis (see Stark 1999 for an overview). Psychologists of religion have made increasingly fine-grained distinctions between types of religiosity, including extrinsic religiosity (being religious as means to an end, for instance, getting the benefits of being a member of a social group) and intrinsic religiosity (people who adhere to religions for the sake of their teachings) (Allport & Ross 1967). Psychologists and sociologists now commonly study religiosity as an independent variable, with an impact on, for instance, health, criminality, sexuality, socio-economic profile, and social networks.

A recent development in the scientific study of religion is the cognitive science of religion (CSR). This is a multidisciplinary field, with authors from, among others, developmental psychology, anthropology, philosophy, and cognitive psychology (see C. White 2021 for a comprehensive overview). It differs from other scientific approaches to religion in its presupposition that religion is not a purely cultural phenomenon. Rather, authors in CSR hold that religion is the result of ordinary, early developed, and universal human cognitive processes (e.g., Barrett 2004, Boyer 2002). Some authors regard religion as the byproduct of cognitive processes that are not evolved for religion. For example, according to Paul Bloom (2007), religion emerges as a byproduct of our intuitive distinction between minds and bodies: we can think of minds as continuing, even after the body dies (e.g., by attributing desires to a dead family member), which makes belief in an afterlife and in disembodied spirits natural and spontaneous. Another family of hypotheses regards religion as a biological or cultural adaptive response that helps humans solve cooperative problems (e.g., Bering 2011; Purzycki & Sosis 2022): through their belief in big, powerful gods that can punish, humans behave more cooperatively, which allowed human group sizes to expand beyond small hunter-gatherer communities. Groups with belief in big gods thus out-competed groups without such beliefs for resources during the Neolithic, which would explain the current success of belief in such gods (Norenzayan 2013). However, the question of which came first—big god beliefs or large-scale societies—is a continued matter of debate.

2. Science and religion in various religions

As noted, most studies on the relationship between science and religion have focused on science and Christianity, with only a small number of publications devoted to other religious traditions (e.g., Brooke & Numbers 2011; Lopez 2008). Since science makes universal claims, it is easy to assume that its encounter with other religious traditions would be similar to its interactions with Christianity. However, given different creedal tenets (e.g., in Hindu traditions God is usually not entirely distinct from creation, unlike in Christianity and Judaism), and because science has had distinct historical trajectories in other cultures, one can expect disanalogies in the relationship between science and religion in different religious traditions. To give a sense of this diversity, this section provides a bird’s eye view of science and religion in five major world religions: Christianity, Islam, Hinduism, Buddhism, and Judaism.

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion, currently the religion with the most adherents. It developed in the first century CE out of Judaism. Christians adhere to asserted revelations described in a series of canonical texts, which include the Old Testament, which comprises texts inherited from Judaism, and the New Testament, which contains the Gospels of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John (narratives on the life and teachings of Jesus), as well as events and teachings of the early Christian churches (e.g., Acts of the Apostles, letters by Paul), and Revelation, a prophetic book on the end times.

Given the prominence of revealed texts in Christianity, a useful starting point to examine the relationship between Christianity and science is the two books metaphor (see Tanzella-Nitti 2005 for an overview): God revealed Godself through the “Book of Nature”, with its orderly laws, and the “Book of Scripture”, with its historical narratives and accounts of miracles. Augustine (354–430) argued that the book of nature was the more accessible of the two, since scripture requires literacy whereas illiterates and literates alike could read the book of nature. Maximus Confessor (c. 580–662), in his Ambigua (see Louth 1996 for a collection of and critical introduction to these texts) compared scripture and natural law to two clothes that envelop the Incarnated Logos: Jesus’ humanity is revealed by nature, whereas his divinity is revealed by the scriptures. During the Middle Ages, authors such as Hugh of St. Victor (ca. 1096–1141) and Bonaventure (1221–1274) began to realize that the book of nature was not at all straightforward to read. Given that original sin marred our reason and perception, what conclusions could humans legitimately draw about ultimate reality? Bonaventure used the metaphor of the books to the extent that “ liber naturae ” was a synonym for creation, the natural world. He argued that sin has clouded human reason so much that the book of nature has become unreadable, and that scripture is needed as an aid as it contains teachings about the world.

Christian authors in the field of science and religion continue to debate how these two books interrelate. Concordism is the attempt to interpret scripture in the light of modern science. It is a hermeneutical approach to Bible interpretation, where one expects that the Bible foretells scientific theories, such as the Big Bang theory or evolutionary theory. However, as Denis Lamoureux (2008: chapter 5) argues, many scientific-sounding statements in the Bible are false: the mustard seed is not the smallest seed, male reproductive seeds do not contain miniature persons, there is no firmament, and the earth is neither flat nor immovable. Thus, any plausible form of integrating the book of nature and scripture will require more nuance and sophistication. Theologians such as John Wesley (1703–1791) have proposed the addition of other sources of knowledge to scripture and science: the Wesleyan quadrilateral (a term not coined by Wesley himself) is the dynamic interaction of scripture, experience (including the empirical findings of the sciences), tradition, and reason (Outler 1985).