Clinical psychology

- Anxiety disorders

- Feeding and eating disorders

- Mood disorders

- Neuro-developmental disorders

- Personality disorders

- Affirmations

- Cover Letters

- Relationships

- Resignation & Leave letters

Psychotherapy

Personality.

Table of Contents

7 Narrative Therapy Worksheets (+ A complete guide)

As a BetterHelp affiliate, we may receive compensation from BetterHelp if you purchase products or services through the links provided.

The Optimistminds editorial team is made up of psychologists, psychiatrists and mental health professionals. Each article is written by a team member with exposure to and experience in the subject matter. The article then gets reviewed by a more senior editorial member. This is someone with extensive knowledge of the subject matter and highly cited published material.

This page presents narrative therapy worksheets.

These narrative therapy worksheets aim to help individuals identify their values and resolve their issues while considering those values.

Some of these narrative therapy worksheets are created by us while some of them have been curated from reputable third-party websites after reviewing relevant content in bulk.

Narrative Therapy Worksheet- Identifying Values

Narrative therapy is a kind of psychotherapy in which individuals identify their skills and abilities to help them resolve their conflicts.

It enables individuals to solve their problems by themselves, using their own abilities. Narrative therapy aid individuals in finding out their values and exploring skills that are associated with those values.

This helps individuals to apply knowledge of their abilities to live these values to enable them to confront their present and future issues.

In addition to helping people recognize their inner voice, narrative therapy allows individuals to use their values for their good.

It enables them to acquire these values to become experts in their lives and live their life according to their goals and values.

When individuals are able to listen to their inner voice, they can efficiently recognize their values and work on achieving them.

This makes their life worth living.

Narrative Therapy Worksheet – Writing My Life Story

Narrative therapy is a non-blaming, interactive and playful approach.

This kind of psychotherapy is helpful for clients who feel their counselors are unable to recognize their needs and help them deal with their issues.

Narrative therapy is helpful for children as well. It is helpful for individuals who are facing difficulties in their lives.

Narrative therapy can aid people with psychological disturbances such as depression or bipolar disorder.

Empirical evidence has shown that narrative therapy has significant impacts on the mental well-being and distress level of an individual.

In addition to it, the effects of narrative therapy are durable.

Narrative therapy aims to disclose the hidden aspects of an individual’s past in the form of life narrative, aid individuals in learning emotion regulation and help them construct new meaning with respect to the stories that may emerge in the therapy.

Narrative Therapy Worksheet- Resolving Conflicts

Narrative therapy is a kind of psychotherapy in which individuals are enabled to identify their values and skills related to those values.

Identifying values gives individuals a direction to move whereas the abilities associated with those values help individuals deal with their present and future issues.

Narrative therapists are found to be similar to solution-focused peers on the basis of their similar assumption that people are resourceful and have strengths.

The people do not see people as having conflicts but they see issues as being imposed on people by the nonbeneficial or detrimental societal cultural practices.

Narrative Therapy Worksheet- My Life Story-A Narrative Exercise

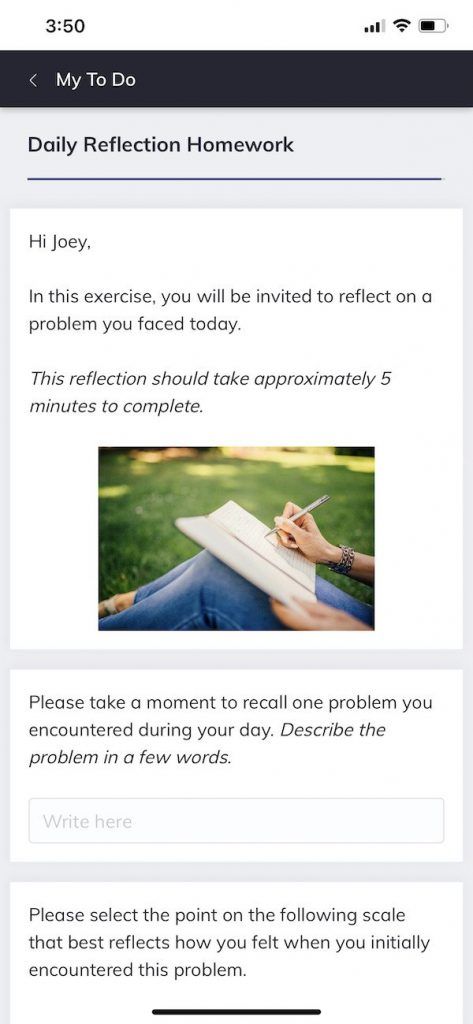

My life story- a narrative exercise, is a great worksheet to help an individual write his life story, mentioning all the important events of his life.

This worksheet aims to help an individual review his life events closely and work on them to prevent the effects of past events on his present and future.

It enables an individual to create emotional distance fro his past so he can become more reflective to understand the true meaning of his life, his values, goals, and ambitions.

The worksheets aid an individual to organize his events by writing his events and develop self-compassion without indulging too deep into his memories.

The worksheet allows an individual to write his life story very briefly, mentioning only the important events of his life.

Then the individual is directed to write something about his future and the important events he wants to ad hin this story.

This is a very simple yet effective worksheet.

You can download it in the form of pdf from here .

Narrative Therapy Worksheet- Life Story

Focusing on the past events of life and determining the effects of those events on the present life of an individual can help him understand the intensity of those events and help him get rid of those memories to improve his present and the future.

The worksheet, life story, by therapistaid.com, is based on narrative therapy.

This worksheet allows the individual to write his life story in three different parts; the past, the present, and the future.

This enables an individual to pay attention to the important events of all three phases of his life and helps him find his true meaning of life, his goals, aims, and values.

It also enables the individual to identify their personal strengths in each of the three sections.

This worksheet aims to aid individuals to find their meaning of life, work on them by recognizing their strengths and develop a sense of fulfillment that leads to happiness and contentment.

This worksheet can be accessed from here .

Narrative Therapy Worksheet- Narrative Therapy Exercises

Narrative therapy exercises consist of ten effective exercises based on narrative therapy, that can help an individual find the true meaning of their lives and work on them.

The first exercise directs the individual to write about the struggling event of his life for four consecutive days.

This exercise enables the individual to identify the small edits in his writings that can have a lasting effect on his life.

The second exercise directs an individual to write about a painful event of his life once but as a 3rd person. This exercise leaves positive impacts on the individual’s life.

Tye third exercises aim to enable the individual to focus on why a certain painful or distressing event occurred in his life.

The fifth exercise increases awareness about oneself and allows the individual to identify his ideal future.

The sixth exercise allows the individual to write a letter about his unresolved or conflictual relationships but with the opposite hand.

The seventh exercise allows the individual to write a letter about the chapter of his life to a close partner.

The eighth exercise directs an individual to write a letter about his life events, past, present, and future to himself.

Ninth exercises aim to increase self-awareness of the individual and enable him to analyze himself.

The last exercise directs the individual to narrate his story to a close partner while considering specific experiences.

This worksheet is easily accessible on the internet. You can download it from here .

Narrative Therapy Worksheet- Problem Solving CYP

Problem-solving CYP worksheet is a great resource for allowing the individual to resolve their conflicts.

This brief, simple but effective worksheet that enables individuals to find out solutions for their problems skillfully.

The worksheet enables individuals to identify their problem and directs them to think of at least three solutions to the problem.

Then it allows the individual to focus on the advantages and disadvantages of using each solution for resolving the conflict.

Next, the individuals are asked to select the best solution ad use it to resolve their conflicts.

This worksheet enhances the problem-solving abilities of an individual and enables him to view one thing from more than one perspective.

It also improves his analyzing skills.

This worksheet can be accessed on the internet easily.

You can download this worksheet for this page.

This page provides you with some of the best and most effective narrative therapy worksheets that are helpful for you in identifying your values, strengths and enhancing your problem-solving abilities.

Some of these worksheets were created by us while some of them were curated from reputable third-party websites.

If you have any questions or queries regarding these worksheets, let us know through your comments.

We will be glad to assist you.

Enjoyed this article? Then Repin to your own inspiration board so others can too!

Was this helpful?

Related posts, the healing power of empathy: how a conversation with an empath psychic can help you feel better, choosing the right nicotine pouch for your daily needs, building resilience: psychological strategies for helping children cope with challenges.

Narrative Therapy: Definition, Techniques & Interventions

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

On This Page:

Narrative therapy, is a powerful psychotherapeutic approach that empowers clients to explore and reshape their life stories, particularly those overwhelmed by challenges and emotional distress.

During sessions, clients engage in open dialogues with their therapists, delving into their narratives and actively challenging the ones that contribute to their struggles.

By separating problems from personal identity, narrative therapy emphasizes the belief that individuals are the ultimate authorities in their own lives.

Through this collaborative process, clients gain a deep understanding of their values and skills, enabling them to effectively confront present and future issues and pave the way for transformative change.

When was narrative therapy developed?

Narrative therapy was developed in the 1980s by therapists Michael White and David Epston. It is still a relatively novel approach to therapy that seeks to have an empowering effect and offer therapy that is non-blaming and non-pathological in nature.

What is a narrative?

A narrative is a story. As humans, we have many stories about ourselves, others, our abilities, our self-esteem , and our work, among many others.

How we have developed these stories is determined by how we have linked certain events together in a sequence and by the meaning attributed to them.

We like to interpret daily experiences in life, seeking to make them meaningful. The stories we have about our lives are created through linking certain events together in a particular sequence across a period of time and finding ways of making sense of them – this meaning forms the plot of the story.

As more and more events are selected and gathered into the dominant plot, the story gains richness and thickness.

The idea is that identity is formed by an individual’s life narrative, and several narratives are at work at once. The interpretation of a narrative can influence thinking, feelings, and behavior.

Many narratives are useful and healthy, whereas others can result in mental distress. Mental health symptoms can come about when there is an unhealthy or negative narrative or if there is a misunderstanding or misinterpretation of a narrative.

What is the aim of narrative therapy?

Narrative therapy seeks to change a problematic narrative into a more productive or healthier one. This is often done by assigning the person the role of narrator in their own story.

Narrative therapy helps to separate the person from the problem and empowers the person to rely on their own skills to minimize problems that exist in their lives.

This therapy aims to teach the person to view alternative stories and address their issues in a more productive way.

Narrative therapy can be used with individuals but can also prove useful for couples or families.

Narrative therapists are also not interested in diagnosing individuals – there is no use of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) during any point of the therapy.

What is the role of the therapist?

The role of the narrative therapist is to search for an alternative way of understanding a client’s narrative or an alternative way to describe it.

The belief is that telling a story is a form of action toward change. Therefore, the therapist will help clients to objectify their problems, frame these problems within a larger sociocultural context, and teach the person how to make room for other stories.

During therapy, the therapist acts as a non-directive collaborator. They treat the client as the expert on their own problems and do not impose judgments.

Instead, the therapist is purely curious and investigative. They are not particularly interested in the cause of a problem but are open to a client’s perception of the cause.

Narrative Therapy Techniques

Putting together the narrative

The therapists help their clients to put together their narratives. This will usually involve listening to the client explain their stories and any issues that they want to bring up.

This allows the person to express their thoughts and explore events in their lives and the meanings they have placed on these experiences.

The therapist may find what is known as a ‘problem-saturated narrative’ comes up, which will be what is causing the client the most distress.

As the story comes together, the client becomes an observer of their story and can then review this with the therapist.

When the therapist communicates to the client during this stage, they will make sure to utilize the client’s use of language since the client is treated as the expert in their narrative.

Externalizing the problem

Once the story is put together, the idea is that it allows the client to observe themselves. The therapist encourages the client to create distance between the individual and their problems, called externalization.

The externalization techniques lead clients towards viewing their problems or behaviors as external instead of an unchangeable part of themselves.

The therapist may ask the client to give a name to the problem so it is seen as a separate entity, such as ‘anger’ or ‘worry.’ The client will then be encouraged to use the given name of the problem when talking about it. Likewise, the therapist will ask questions referring to the problem by the given name.

The distance given to the problem allows people to focus on changing unwanted behaviors.

As people practice externalization, they will see that they can change. The general idea is that it is easier to change a behavior that they do than to change a core personality characteristic.

They will realize that they themselves are not the problem; instead, the problem is the problem.

Deconstruction

Often, when a client has a problematic story, especially when it has been prevalent for a long time, the problem can feel overwhelming, confusing, or unsolvable.

Because of these feelings, people can use overgeneralized statements which can make the problematic stories worse.

The narrative therapist would work with the individual to break down or deconstruct their stories into smaller, more manageable parts to clarify the problem.

Deconstructing makes the problems more specific and reduces overgeneralizing; it also clarifies what the core issue or issues may be. Through deconstructing, the whole picture becomes easier to understand.

The therapist and client may also seek to deconstruct identity and have an awareness of larger societal issues, e.g., sociocultural and political effects which may be acting on the client.

They may find that the context of gender, class, race, culture, and sexual identity also play a part in the interpretations and meanings given to events.

Unique outcomes

When someone’s problematic stories are well established, people can become stuck in them, unable to view alternative versions of the story. A narrative therapist will help people challenge their stories and encourage them to consider alternative stories.

Unique outcomes refer to the exceptions to the dominant story. It may also be known as ‘re-authoring’ or ‘re-storying,’ as clients go through their experiences to find alterations to their story or make a whole new one.

There are hundreds of different stories since everyone interprets experiences differently and finds their own meaning from them. The therapist will help the client to build upon an alternative or preferred story.

These unique outcomes contrast a problem, reflect a person’s true nature, and allow someone to rewrite their story.

Building upon stories from another perspective can help to overcome problems and build the confidence the person needs to heal from them.

Benefits of narrative therapy

Empowers the individual.

As this therapy stresses that people do not label themselves negatively (e.g., as the problem), this can help them feel less powerless in distressing situations.

They find that they have more control over the stories they have in their lives and how they approach difficult events.

Narrative therapy treats individuals with respect and supports the bravery it has taken for them to choose to work through their personal challenges.

Non-confrontational

This is a non-judgmental approach to therapy, meaning that the clients are not blamed for anything described in their stories.

Likewise, the clients are encouraged not to blame others or themselves. The focus is instead placed on noticing and changing unhelpful stories about themselves and others.

The client is treated as an expert

Narrative therapy does not aim to change a person; rather, it allows them to become an expert in their own lives.

The therapist holds that the clients know themselves well and work as collaborative partners with the client.

This therapy allows people to not only find their voice but to use this voice for good, enabling them to become experts and live in a way that reflects their goals and values.

Context is considered

This therapy may also help the client view their problems differently. These can be social, political, and cultural, among others.

The clients recognize that these contexts matter and can influence how they view themselves and their stories.

What can narrative therapy help with?

Narrative therapy may help treat the symptoms of a variety of conditions, including:

Anxiety disorders

Depressive disorders

Eating disorders

Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder ( ADHD )

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

As well as mental health conditions, narrative therapy may also be useful for the following:

Those who feel like they are overwhelmed by negative experiences, thoughts, or emotions.

Those with attachment issues .

Those who are suffering from grief.

Those who have issues with low self-esteem.

Those who often feel powerless in many situations.

How is narrative therapy used?

For individuals, narrative therapy challenges the dominant problematic stories that prevent people from living their best lives.

Through the externalizing technique, people can learn to separate themselves from the problem.

They learn to identify alternative stories, widen their views of themselves, challenge old and unhealthy beliefs, and be open to new ways of living that reflect a more accurate and healthier story.

For couples or families, externalizing problems can facilitate positive interaction.

It can also make negative communication more accepting and meaningful. Seeing problems objectively can help couples and families reconnect and strengthen their relationships.

Once problems have been identified, this can be used to address how the problem has challenged the core strength of their bond.

How effective is narrative therapy?

Below are some of the studies which have investigated the effectiveness of narrative therapy:

A research study looked at evaluating the effectiveness of narrative therapy in increasing couples’ intimacy and its dimensions.

The results showed that this therapy significantly increased intimacy and on three dimensions of emotional, communication, and general intimacy, concluding that narrative therapy can provide valuable implications for the mental health of couples (Khodabakhsh et al., 2015).

Research has found that married women experienced increased levels of marital satisfaction after being treated with narrative therapy (Ghavibazou et al., 2020).

A study of adults with depression and anxiety looked at the effects of narrative therapy and found improvements in their self-reports of quality of life, and they had decreased symptoms of anxiety and depression (Shakeri et al., 2020).

A small sample pilot study aimed to determine whether narrative therapy was effective in helping young people with Autism who present with emotional and behavioral difficulties.

It was found that there were significant improvements in psychological distress and emotional symptoms (Cashin et al., 2013).

A study looked at the effectiveness of narrative therapy in boosting 8-10-year old’s social and emotional skills. The results showed that the children showed significant improvements in self-awareness, self-management, empathy, and responsible decision-making (Beaudoin et al., 2016).

A study explored group narrative therapy for improving the school behavior of a small sample of girls with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD).

Posttreatment ratings by teachers showed that there was a significant effect on reducing ADHD symptoms one week after completing the therapy sessions, and this was sustained after 30 days (Looyeh et al., 2012).

Limitations

One of the major limitations of narrative therapy is that research into its effectiveness is still lacking.

Further research is also needed to determine what mental health conditions narrative therapy might treat most effectively.

A reason for the lack of research is that it is still a relatively new approach to therapy. Another reason could be due to it being difficult to quantify.

The view that narrative therapists have is that knowledge is subjective and constructed by each person.

They accept there is no universal truth, so some narrative therapists make the argument that this therapy should be studied qualitatively rather than quantitatively.

How to get started

Narrative therapy is a specialized approach to counseling with training opportunities for therapists to learn how to use this approach with clients.

Finding the right therapist can involve looking online through therapist directories. Alternatively, you may consider asking your doctor to refer you to a professional in your area with the right training and experience.

It is important to choose the right therapist for you. Consider whether you feel comfortable discussing personal information with them. Don’t be afraid to seek a different therapist if the one you have does not quite suit your needs.

When choosing a therapist, consider thinking about what your deal breakers are, important qualities, and any other characteristics you value.

What questions can you ask yourself when considering therapy?

When you are ready to select a therapist, think about the following:

1. What type of therapy do you want? – Do you want individual, couples, family therapy, or another type?

2. What are your main goals for therapy?

3. Whether you can commit the time each week – what days and times are most convenient for you?

What can be expected during the first therapy session?

During the first narrative therapy session, the therapist may ask you to begin sharing your story, and they may ask questions about why you are seeking treatment.

The therapist may also want to know about how your problems are affecting your life and what your goals for the future are.

Furthermore, they are likely to discuss aspects of treatment, such as how often you will meet and how your treatment may change from one session to the next.

What are some considerations for narrative therapy?

This therapy can be very in-depth, exploring a wide range of factors that can influence the development of your stories.

It also involves talking about problems as well as strengths which may be difficult for some people.

The therapist will help you to explore your dominant story in-depth and discover how it may be contributing to emotional distress, as well as uncover strengths that can help you to approach your problems differently.

You should expect to re-evaluate your judgments about yourself since narrative therapy encourages you to challenge and reassess these thoughts and replace them with more realistic or positive ones.

It also challenges you to separate yourself from your problems which can be difficult, but this process helps you learn to give yourself credit for making the right decisions for you.

Do you need mental health help?

Contact the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for support and assistance from a trained counselor. If you or a loved one are in immediate danger: https://suicidepreventionlifeline.org/

1-800-273-8255

Contact the Samaritans for support and assistance from a trained counselor: https://www.samaritans.org/; email [email protected] .

Available 24 hours a day, 365 days a year (this number is FREE to call):

Rethink Mental Illness: rethink.org

0300 5000 927

Further Information

Wallis, J., Burns, J., & Capdevila, R. (2011). What is narrative therapy and what is it not? The usefulness of Q methodology to explore accounts of White and Epston’s (1990) approach to narrative therapy. Clinical Psychology & Psychotherapy, 18(6), 486-497.

Hutto, D. D., & Gallagher, S. (2017). Re-Authoring narrative therapy: Improving our selfmanagement tools. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology, 24(2), 157-167.

Morgan, A. (2000). What is narrative therapy? (p. 116). Adelaide: Dulwich Centre Publications.

Beaudoin, M. N., Moersch, M., & Evare, B. S. (2016). The effectiveness of narrative therapy with children’s social and emotional skill development: an empirical study of 813 problem-solving stories. Journal of Systemic Therapies, 35(3), 42-59.

Cashin, A., Browne, G., Bradbury, J., & Mulder, A. (2013). The effectiveness of narrative therapy with young people with autism. Journal of Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Nursing, 26(1), 32-41.

Ghavibazou, E., Hosseinian, S., & Abdollahi, A. (2020). Effectiveness of narrative therapy on communication patterns for women experiencing low marital satisfaction. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy, 41(2), 195-207.

Khodabakhsh, M. R., Kiani, F., Noori Tirtashi, E., & Khastwo Hashjin, H. (2015). The effectiveness of narrative therapy on increasing couples intimacy and its dimensions: Implication for treatment. Family Counseling and Psychotherapy, 4(4), 607-632.

Looyeh, M. Y., Kamali, K., & Shafieian, R. (2012). An exploratory study of the effectiveness of group narrative therapy on the school behavior of girls with attention-deficit/hyperactivity symptoms. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 26(5), 404-410.

Shakeri, J., Ahmadi, S. M., Maleki, F., Hesami, M. R., Moghadam, A. P., Ahmadzade, A., Shirzadi, M. & Elahi, A. (2020). Effectiveness of group narrative therapy on depression, quality of life, and anxiety in people with amphetamine addiction: a randomized clinical trial. Iranian Journal of Medical Sciences, 45(2), 91.

- Bipolar Disorder

- Therapy Center

- When To See a Therapist

- Types of Therapy

- Best Online Therapy

- Best Couples Therapy

- Best Family Therapy

- Managing Stress

- Sleep and Dreaming

- Understanding Emotions

- Self-Improvement

- Healthy Relationships

- Student Resources

- Personality Types

- Guided Meditations

- Verywell Mind Insights

- 2023 Verywell Mind 25

- Mental Health in the Classroom

- Editorial Process

- Meet Our Review Board

- Crisis Support

How Narrative Therapy Works

Jodi Clarke, LPC/MHSP is a Licensed Professional Counselor in private practice. She specializes in relationships, anxiety, trauma and grief.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/WIN_20200624_14_59_57_Pro-01f186878e18427b84df787004c95807.jpg)

Steven Gans, MD is board-certified in psychiatry and is an active supervisor, teacher, and mentor at Massachusetts General Hospital.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/steven-gans-1000-51582b7f23b6462f8713961deb74959f.jpg)

Verywell / Marina Li

What Is the Goal of Narrative Therapy?

Effectiveness, things to consider, how to get started.

Narrative therapy is a style of therapy that helps people become—and embrace being—an expert in their own lives. In narrative therapy, there is an emphasis on the stories that you develop and carry with you through your life.

As you experience events and interactions, you give meaning to those experiences and they, in turn, influence how you see yourself and the world. You can carry multiple stories at once, such as those related to your self-esteem , abilities, relationships, and work.

Developed in the 1980s by New Zealand-based therapists Michael White and David Epston, narrative therapy seeks to have an empowering effect and offer counseling that is non-blaming and non-pathological in nature.

There are a variety of techniques and exercises used in narrative therapy to help people heal and move past a problematic story. Some of the most commonly used techniques include the following.

Putting Together Your Narrative

Narrative therapists help their clients put together their narrative. This process allows the individual to find their voice and explore events in their lives and the meanings they have placed on these experiences. As their story is put together, the person becomes an observer to their story and looks at it with the therapist, working to identify the dominant and problematic story.

Externalization

Putting together the story of their lives also allows people to observe themselves. This helps create distance between the individual and their problems, which is called externalization . This distance allows people to better focus on changing unwanted behaviors. For example, a client might name anxiety “the Goblin” and explain to their therapist how they feel when "the Goblin" is around and how they cope with it.

As people practice externalization, they get a chance to see that they are capable and empowered to change.

Deconstruction

Deconstruction is used to help people gain clarity in their stories. When a problematic story feels like it has been around for a long time, people might use generalized statements and become confused in their own stories. A narrative therapist would work with the individual to break down their story into smaller parts, clarifying the problem and making it more approachable.

Unique Outcomes

When a story feels concrete, as if it could never change, any idea of alternative stories goes out the window. People can become very stuck in their story and allow it to influence several areas of their lives, impacting decision-making, behaviors, experiences, and relationships.

A narrative therapist works to help people not only challenge their problems but widen their view by considering alternative stories.

What Can Narrative Therapy Help With

While narrative therapy is a relatively new treatment approach, there is some evidence that it may be helpful for a variety of conditions. Mental health conditions it might help include:

- Attachment issues

- Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD)

- Eating disorders

- Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD)

This approach can also be useful for anyone who feels like they are overwhelmed by negative experiences, thoughts, or emotions. This type of therapy stresses the importance of people not labeling themselves or seeing themselves as "broken" or "the problem," or for them to feel powerless in their circumstances and behavior patterns.

Narrative therapy allows people to not only find their voice but to use their voice for good, helping them to become experts in their own lives and to live in a way that reflects their goals and values. It can be beneficial for individuals, couples, and families.

Benefits of Narrative Therapy

Narrative therapy holds a number of key principles including:

- Respect : People participating in narrative therapy are treated with respect and supported for the bravery it takes to come forward and work through personal challenges.

- Non-blaming : There is no blame placed on the client as they work through their stories and they are also encouraged to not place blame on others. Focus is instead placed on recognizing and changing unwanted and unhelpful stories about themselves and others.

- Client as the expert : Narrative therapists are not viewed as an advice-giving authority but rather a collaborative partner in helping clients grow and heal. Narrative therapy holds that clients know themselves well and exploring this information will allow for a change in their narratives.

Narrative therapy challenges dominant problematic stories that prevent people from living their best lives. Through narrative therapy, people can identify alternative stories, widen people's views of self, challenge old and unhealthy beliefs, and open their minds to new ways of living that reflect a more accurate and healthy story.

Narrative therapy does not aim to change a person but to allow them to become an expert in their own life.

Narrative therapy appears to offer benefits in the treatment of a number of different conditions and in a variety of settings. Some evidence supporting the effectiveness of this approach:

- One study found that adults with depression and anxiety who were treated with narrative therapy experienced improvements in self-reported quality of life and decreased symptoms of anxiety and depression.

- One study found that narrative therapy was effective at helping children improve empathy, decision-making, and social skills.

- Other research has found that married women experienced increased levels of marital satisfaction after being treated with narrative therapy.

Further research is needed to determine what mental health conditions narrative therapy might treat most effectively.

Narrative therapy may present some challenges that you should consider before you begin treatment. Some things to be aware of before you begin:

- This type of therapy can be very in-depth . It explores a wide range of factors that can influence the development of a person's story. This includes factors such as age, socioeconomic status, race, ethnicity, gender, and sexual identity.

- It involves talking about your problems as well as your strengths . A therapist will help you explore your dominant story in-depth, discover ways it might be contributing to emotional pain, and uncover strengths that can help you approach problems in different ways.

- You'll reevaluate your judgments about yourself . Sometimes people carry stories about themselves that have been placed on them by others. Narrative therapy encourages you to reassess these thoughts and replace them with more realistic, positive ones.

- It challenges you to separate yourself from your problems . While this can be difficult, the process helps you learn to give yourself credit for making good decisions or behaving in positive ways.

This process can take time, but can eventually help people find their own voice and develop a healthier, more positive narrative.

Narrative therapy is a unique, specialized approach to counseling. There are training opportunities for therapists to learn more about narrative therapy and how to use this approach with clients.

Trained narrative therapists are located throughout the world and can be found through online resources and therapist directories. You might also consider asking your doctor to refer you to a professional in your area with training and experience in narrative therapy.

During your first session, your therapist may ask you to begin sharing your story and ask questions about the reasons you are seeking treatment. Your therapist may also want to know about how your problems are affecting your life and what your goals for the future are. You will also likely discuss aspects of treatment such as how often you will meet and how your treatment may change from one session to the next.

Wallis J, Burns J, Capdevila R. What is narrative therapy and what is it not?: The usefulness of Q methodology to explore accounts of White and Epston's (1990) approach to narrative therapy . Clin Psychol Psychother . 2011;18(6):486-97. doi:10.1002/cpp.723

Hutto DD, Gallagher S. Re-authoring narrative therapy: improving our self-management tools . Philosophy, Psychiatry and Psychology . 2017.24(2):157-167. doi:10.1353/ppp.2017.0020

Rice, Robert H. (2015). "Narrative Therapy." The SAGE Encyclopedia of Theory in Counseling and Psychology 2 , 695-700.

Shakeri J, Ahmadi SM, Maleki F, Hesami MR, Parsa Moghadam A, Ahmadzade A, Shirzadi M, Elahi A. Effectiveness of group narrative therapy on depression, quality of life, and anxiety in people with amphetamine addiction: A randomized clinical trial . Iran J Med Sci . 2020;45(2):91-99. doi:10.30476/IJMS.2019.45829

Beaudoin M, Moersch M, Evare BS. The effectiveness of narrative therapy with children’s social and emotional skill development: An empirical study of 813 problem-solving stories . Journal of Systemic Therapies. 2016;(35)3: 42-59. doi:10.1521/jsyt.2016.35.3.42

Ghavibazou E, Hosseinian S, Abdollahi A. Effectiveness of narrative therapy on communication patterns for women experiencing low marital satisfaction . Australian & New Zealand Journal of Family Therapy . 2020;41(2):195-207.doi:10.1002/anzf.1405

Muruthi B, McCoy M, Chou J, Farnham A. Sexual scripts and narrative therapy with older couples . The American Journal of Family Therapy . 2018;46(1):81-95. doi:10.1080/01926187.2018.1428129

Dulwich Centre Publications. What Is Narrative Therapy?

Goodtherapy.org. Narrative Therapy .

Positive Psychology Program. 19 Narrative Therapy Techniques, Interventions and Worksheets .

By Jodi Clarke, MA, LPC/MHSP Jodi Clarke, LPC/MHSP is a Licensed Professional Counselor in private practice. She specializes in relationships, anxiety, trauma and grief.

Narrative Therapy

Reviewed by Psychology Today Staff

Narrative therapy is a form of counseling that views people as separate from their problems and destructive behaviors. This allows clients to get some distance from the difficulty they face; this helps them to see how it might actually be helping or protecting them, more than it is hurting them. With this perspective, individuals feel more empowered to make changes in their thought patterns and behavior and “rewrite” their life story for a future that reflects who they really are, what they are capable of, and what their purpose is, separate from their problems.

Michael White and David Epston developed this therapy type in the 1980s. They thought that an individual should see themselves as making a mistake, rather than seeing themselves as bad, per se. The individual is respectful of the self and does not point blame or judgment inward. A good narrative helps a person to process and clarify what they experience. In a paper that appeared in The Sage Encyclopedia of Theory in Counseling and Psychology, this modality can be useful for individuals.

There are core aspects of narrative therapy:

- The deconstruction of problematic and dominant storylines or narratives

- Breaking the narrative into smaller and more manageable chunks

- Rewriting the script of the problematic and dominant storylines

- Broadening your view and moving toward healthier storylines (this is also called the unique outcomes technique, which may help us better understand our experiences and emotions)

- What is true for one person may not be true for another person

- Externalizing the problem because you are not your problem

- A healthy narrative will also help us make meaning and see purpose

- When It's Used

- What to Expect

- How It Works

- What to Look for in a Narrative Therapist

Individuals, couples, and families can all benefit from narrative therapy . Those who define themselves by their problems, whose lives are dominated by such feelings as “I am a depressed person” or “I am an anxious person” can learn to see their problem as something they have but not something that identifies who they are.

This form of therapy can be helpful for people who suffer from these conditions, among others:

- Eating problems

- General difficulties with emotion regulation

Your therapist will encourage you to direct the conversation by asking what you prefer to talk about and, on an ongoing schedule, checking to see if the topic, which is most likely a problem, is still something you are interested in discussing. After some time, your therapist will lead you to tell other, more positive stories from your life to help you discover inherent traits and skills that can be used to address your problems. The goal is for you to see how there are positive and productive ways to approach your life and your future when you stop identifying yourself by your problems.

In narrative therapy, the events that occur over time in a person’s life are viewed as stories, some of which stand out as more significant or more fateful than others. These significant stories, usually stemming from negative events, can ultimately shape one’s identity . Beyond this identity, the narrative therapist views a client’s life as multitiered and full of possibilities that are just waiting to be discovered. The therapist does not act as the expert, but rather helps clients see how they are the experts regarding their own life and how they can uncover the dreams , values, goals , and skills that define who they are, separate from their problems. These are the buried stories that can be rewritten and woven into the ongoing and future stories of their lives.

A narrative therapist is a licensed mental health professional, social worker, or therapist who has additional training in narrative therapy through academic programs, intensive workshops, or online continuing education . In addition to checking credentials and experience, you should feel safe and comfortable working with any narrative therapist you choose.

Screen your potential therapist either in person or over video or phone. During this initial introduction, ask the therapist:

- How they may help with your particular concerns

- Have they dealt with this type of problem before

- What is their process

- What is the treatment timeline

- Find a Therapist

- Find a Treatment Center

- Find a Psychiatrist

- Find a Support Group

- Find Online Therapy

- United States

- Brooklyn, NY

- Chicago, IL

- Houston, TX

- Los Angeles, CA

- New York, NY

- Portland, OR

- San Diego, CA

- San Francisco, CA

- Seattle, WA

- Washington, DC

- Asperger's

- Bipolar Disorder

- Chronic Pain

- Eating Disorders

- Passive Aggression

- Personality

- Goal Setting

- Positive Psychology

- Stopping Smoking

- Low Sexual Desire

- Relationships

- Child Development

- Therapy Center NEW

- Diagnosis Dictionary

- Types of Therapy

Understanding what emotional intelligence looks like and the steps needed to improve it could light a path to a more emotionally adept world.

- Emotional Intelligence

- Gaslighting

- Affective Forecasting

- Neuroscience

Narrative Therapy Techniques (4 Examples)

Have you ever seen TikToks or memes that talk about “being the main character?” Sometimes they poke fun at different genres of movies, and sometimes they poke fun at ourselves. Other types of content encourage people to treat themselves as the main character of their own story.

These ideas aren’t just jokes or memes. They are found in a specific type of therapy that can help people process trauma, understand their feelings, and approach difficult situations in a more objective and realistic manner: narrative therapy.

What Is Narrative Therapy?

Narrative therapy is an approach that aims to empower people. In this approach, patients tell their story as if they were the protagonist in a book or a movie. Through this retelling, the patient goes through the typical "hero's journey" and personal development that is found in narratives.

Who Created Narrative Therapy?

Narrative therapy was developed in the 1980s by two therapists based in New Zealand, Michael White and David Epston.

Who Is Narrative Therapy Good For?

Although anyone can use narrative therapy as their main form of treatment, certain therapists may recommend it for some clients over others. Reddit user CurveoftheUniverse said, "While I was in grad school, I had a professor whose main schtick was narrative therapy. It didn't really grab me then, but now I find myself wishing I could have taken advantage of his knowledge. I find it really useful for adolescents since we start developing autobiographical memory around age 12."

Conscious-Section-55 said "Hi, my clinical supervisor used it as her go-to jam. I've used it a little but, more important, I often incorporate narrative interventions (most notably externalizing the problem) into my own integrative approach."

You can read the whole conversation about the benefits of narrative therapy here .

How Narrative Therapy Works

What feels more empowering than being a protagonist? Protagonists in movies, books, and television shows face obstacles and trauma, but always manage to rise up to the occasion and win in the end. If you can see yourself on that journey, you may find yourself seeing setbacks and trauma in a new light.

It’s not enough to just tell yourself that you are the main character of your story. You might already feel like the main character, but have just been telling yourself a story that isn’t helping you achieve your goals. There are an infinite amount of ways to tell a story. The “truth” of what happened to Goldilocks and the Three Bears probably looks different when you consider the story from the perspective of Goldilocks, Mama Bear, Papa Bear, Baby Bear, the bear’s neighbors, etc. By using the following techniques, you and your therapist can find the story that helps you feel the most empowered.

Techniques Used in Narrative Therapy

Writing the narrative.

The first piece of narrative therapy is writing your narrative. This is not something that everyone consciously does. When you first meet with a narrative therapist, you may find yourself collecting events, judgements, and behaviors that form this story. Your therapist will pick up on common themes. This is the base material for the upcoming techniques.

Often, people find themselves telling one story based on a “thin description.” Thin descriptions may have no basis in objective reality, but have made their way into being the dominant story of our lives.

Example of Narrative Therapy

Here’s an example. A patient experienced their father walking out on their family as a young child. They were left to take care of their mother, who blamed the child for their father’s actions. This one incident told the child to things: they had to take care of others, and they were unlovable.

As a child or young adult, a “thin” description like this can control your entire life. Whenever the child experiences rejection, they tell themselves they are unlovable. As they grow up and seek out romantic relationships , they tell themselves that the only way to keep their partner around is to take care of all of their needs. If they try to ask for any support or do anything from themselves, the partner will leave. The patient will see this as further evidence that they are unlovable.

Thin descriptions are the key to understanding why a person may make certain decisions or display certain behaviors. Once these descriptions are unlocked and the current narrative is created, the therapist and patient will move on to view the narrative from a more objective standpoint.

Externalization

If you grow up telling yourself that you are unlovable, you are going to unconsciously stick to that story. But think about this. What if your best friend were to tell you that they were unlovable? How might things change if your parent told you that? What if a random person in a Starbucks told you that? You’d probably think they were being ridiculous!

Now put yourself in your best friend, parent, or random person in Starbucks’ shoes. If you came up to them and said you were unlovable, despite the story you have been telling yourself for decades, they would also think that you were being ridiculous.

Therapists help patients create narratives so they can step out of their story and view it from an outsider’s perspective. This technique is called externalising.

When you see a friend, stranger, or main character in a book struggling, you are more likely to cheer them on. Why can’t you do the same with yourself? As you externalize and see your problems from an outsider’s perspective, you will be able to see other solutions and have confidence that you can overcome anything that is thrown at you.

Deconstruction

This journey that we are each on can feel overwhelming. Your story is your entire life. The feelings that someone may have of being unlovable, or being required to sacrifice themselves for others, that is their whole life. In order to put someone’s personal story into perspective, a therapist may ask their patient to deconstruct the story. Looking at individual incidents show just how “thin” some descriptions are.

Example of Deconstruction

A therapist may, for example, look at the incident that appeared to “start it all.” They may talk to their patient specifically about the moment when their dad left them. A child may not have the capacity to understand why a parent may leave their family. They turn the blame on themselves, because a child is at the center of their entire world. The child grows up to believe the story that they told themself as a child because they know no other story.

We are not given many opportunities to revisit these moments and deconstruct them. In therapy, patients may find themselves talking about incidents for the first time in years, or ever. During the deconstruction process, they see the incident in a new light. They might come to the realization that their father leaving them was not about them at all. Their father’s actions may have been caused by the father’s immaturity, their mother’s inability to be a good partner for their father, or a larger reason that has nothing to do with the mother and father at all. The “real” reason” doesn’t matter because in narrative therapy, patients and therapists must acknowledge that there is no “objective reality” or absolute truth. Our reality is created by the stories that we tell ourselves.

This process is easier said than done, but it creates a path for people to see their problems and tell their story in a new light.

Unique Outcomes

When you meet a character in a movie or book who is just unlovable and does nothing to change their ways throughout the story, you don’t have high hopes for them, do you? The same thing happens when we let one dominant story take over our life. If you were to only tell yourself that you were unlovable, you are not going to have hope that everything will turn around for you one day. You have no “proof” that you will reach that outcome.

Why Is Narrative Therapy Effective?

The beautiful thing about narrative therapy is that through writing the narrative, externalization, and destruction, you will start to see different outcomes for yourself. You will see that you are capable of growth and change. Breaking down a “thin” description prevents it from steering you onto one path. The end goal of this approach is to show you the many possibilities that you have for your future.

Did Sansa Stark let the woman she was in the past, and the beliefs she had, hold her back? No. Did Steve Harrington let his previous jock persona prevent him from becoming a protector to the kids in Stranger Things? No. Are you going to let the person you were in the past, or the incidents that happened outside of your control, right your story? No. Through narrative therapy, you can learn to write your own unique outcomes based on the person that you want to be and the goals you want to achieve.

How to Implement Narrative Therapy Into Your Life

Narrative therapy is a respectful approach that allows patients to look at their life without carrying blame or guilt for setbacks that they have faced. Through this practice, many patients have found a sense of self-compassion that they did not have before. If this approach to therapy interests you, I recommend looking for a therapist that has been trained in narrative therapy. You do not just have to be the main character of your life, going through setbacks and obstacles without any control over the ending to your story. Narrative therapy shows you that you can be the main character and the narrator and the author. The resolution to conflict is up to you. Your “happily ever after” is within your reach. Using this form of therapy, you can finally enjoy the story that you want to live.

How to Find a Therapist That Specializes in Narrative Therapy

You do not have to go on this journey alone. Narrative therapy was developed by therapists, and therapists use this technique on their clients. If you are interested in trying narrative therapy, reach out to a mental health counselor who can guide you.

Research therapists in your area who use narrative therapy. A lot of therapy websites categorize local therapists by the approach they use. All you have to do is search "narrative therapy [your city here]" and start combing through the results!

Do a consultation. Narrative therapy isn't for everyone, and therapists know that. To "screen" clients, therapists offer a free consultation. Often, these consultations are 15 to 20 minutes long. Before you get on the phone with a therapist, have questions ready. A few questions can be about narrative therapy:

- Do you offer narrative therapy?

- How do you approach narrative therapy?

- Do you think I'm a candidate for narrative therapy; why or why not?

In this conversation, you'll get a better sense if you feel comfortable with this therapist.

Be patient. It takes a long time to write a novel. Similarly, it takes a long time to write the story of your life. Be patient and enjoy the "wins" as they happen.

Related posts:

- The Psychology of Long Distance Relationships

- Beck’s Depression Inventory (BDI Test)

- Flooding Therapy (Psychology Definition + Explanation)

- Operant Conditioning (Examples + Research)

- Variable Interval Reinforcement Schedule (Examples)

Reference this article:

About The Author

Free Personality Test

Free Memory Test

Free IQ Test

PracticalPie.com is a participant in the Amazon Associates Program. As an Amazon Associate we earn from qualifying purchases.

Follow Us On:

Youtube Facebook Instagram X/Twitter

Psychology Resources

Developmental

Personality

Relationships

Psychologists

Serial Killers

Psychology Tests

Personality Quiz

Memory Test

Depression test

Type A/B Personality Test

© PracticalPsychology. All rights reserved

Privacy Policy | Terms of Use

Nathan B. Weller

The Tree of Life: A Simple Exercise for Reclaiming Your Identity and Direction in Life Through Story

In my last post I shared a book that has made a profound impact on me. It’s called Retelling the Stories of Our Lives: Everyday Narrative Therapy to Draw Inspiration and Transform Experience by David Denborough.

As I read this book so many things about the nature of stories and their role in human life came into sharp focus. Things that I have been working out for years on my own but could only vaguely express in comparison to the clarity I found in this book.

Just having the idea of using story to work through trauma or a crisis of identity validated was a big deal for me. I knew it was possible (because I had done it in my own life) but I was completely unaware that there was a whole subset of psychologists and therapists dedicated to using stories (in a non-religious context) to heal and empower people all over the world.

Advertisement

To discover this has filled me with a new wellspring of passion for learning all that I can about the power, utility, and essential nature of stories. And of course, sharing those lessons with anyone who cares to read this blog.

That’s why I’m excited to share an exercise from Denborough’s book called The Tree of Life. It’s something literally anyone can do in under an hour and yet the results can positively shape the rest of your life.

Table of Contents

The Tree of Life Concept

The tree of life concept is pretty simple and straightforward. It is a visual metaphor in which a tree represents your life and the various elements that make it up–past, present, and future.

By labeling these parts, you not only begin to discover (or perhaps rediscover) aspects of yourself shaped by the past, but you can then begin to actively cultivate your tree to reflect the kind of person you want to be moving forward.

Just as we learned in my last post that the stories of our lives are the events we choose to highlight and contextualize, in this post we will learn how to discover and highlight alternate paths through our past–which in turn create new horizons in our future.

Follow the instructions below to give it a try for yourself.

The Tree of Life Exercise

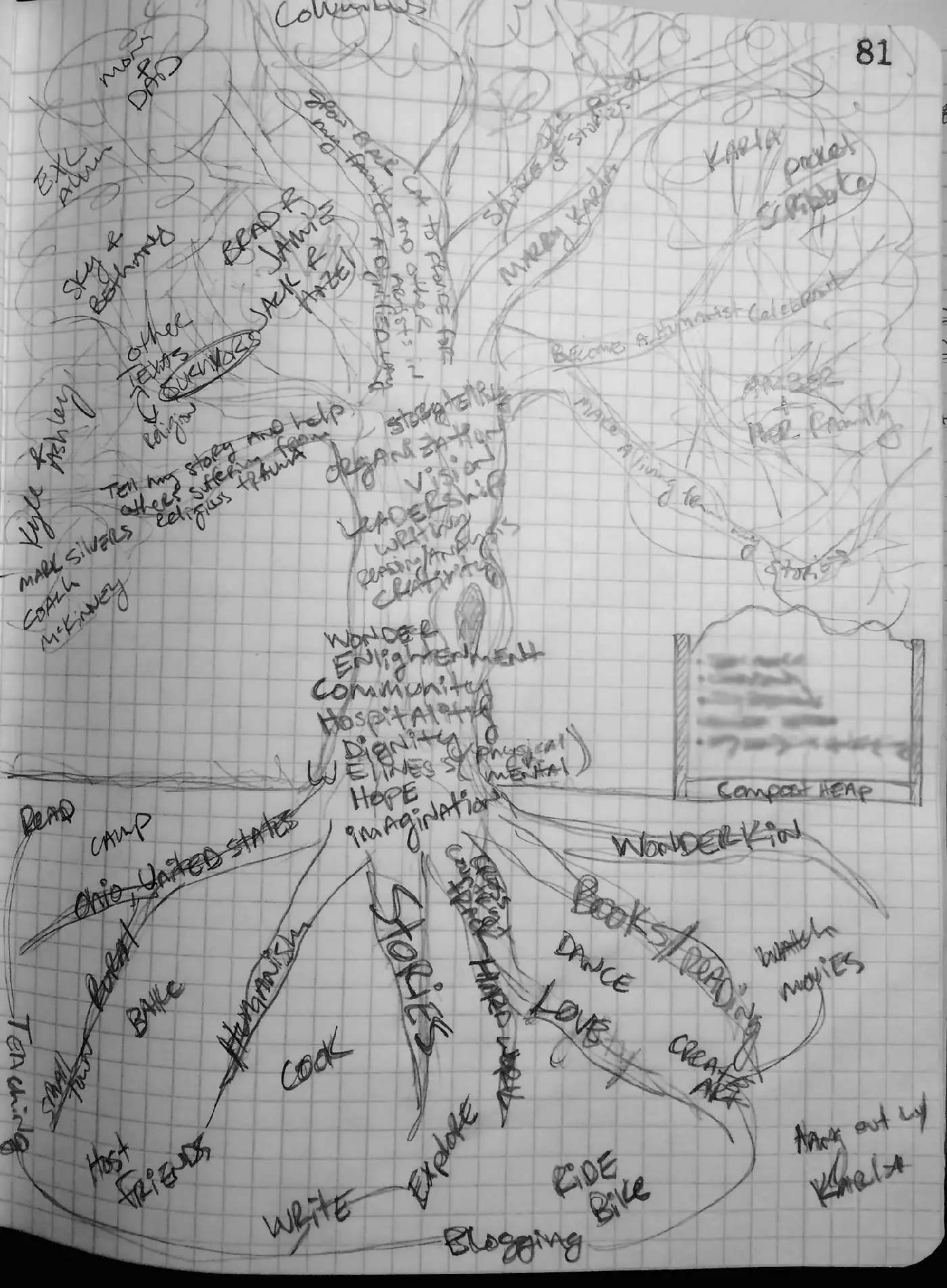

The image below is an example of what the tree of life exercise will look like once complete. I was able to complete this rough draft in about an hour. The instructions below will describe how you can create your own.

The first step of course is to draw a tree. I’ve included a video below that should help if you feel lost. However, I should note that–at least for your first draft–it might be helpful to keep it rough. You can always go back later and redraw or touch-up your existing drawing for aesthetics. This round is all about getting the information down.

Next, follow the labeling instructions below. If you can only think of one or two things per section at a time, don’t worry about it. The nature of this exercise is that as you complete each step, it unlocks more memories and ideas for other parts. You can skip around and fill things in at any time. The most helpful thing in the beginning is to just write stuff down and see where it takes you. You might be surprised!

The Compost Heap ( Optional–But Highly Recommended! )

Write down anything in your compost heap that would normally go in the other sections described below but which are now things you no longer want to be defined by.

These are often sources of trauma, abuse, cultural standards of normality/beauty/etc. or anything else that shapes negative thoughts about yourself in your mind. You can write down places, people, problems, experiences. Whatever you need to.

I blurred mine out above, but you can see it has several items. Generally they all have to do with past trauma and damaging relationships I’m trying to let go of. I’ve found that the idea of a compost heap is an extremely helpful way to think about these things. Especially since many of them are not neatly categorized as “all bad”.

There are in fact quite a few life defining lessons I learned through the things that ended up in my compost heap. And like a compost heap is supposed to do, I will eventually break those things down and re-sow the rich parts back into my life.

You can do the same with yours.

Write down where you come from on the roots. This can be your home town, state, country, etc. You could also write down the culture you grew up in, a club or organization that shaped your youth, or a parent/guardian.

Write down the things you choose to do on a weekly basis on the ground. These should not be things you are forced to do, but rather things you have chosen to do for yourself.

Write your skills and values on the trunk. I chose to write my values starting at the base of the trunk going up. I then transitioned into listing my skills. For me this felt like a natural progression from roots to values to skills.

The Branches

Write down your hopes, dreams, and wishes on the branches. These can be personal, communal, or general to all of mankind. Think both long and short term. Spread them around the various branches.

Write down the names of those who are significant to you in a positive way. Your friends, family, pets, heroes, etc.

Write down the legacies that have been passed on to you. You can begin by looking at the names you just wrote on leaves and thinking about the impact they’ve had on you and what they’ve given to you over the years. This can be material, such as an inheritance, but most often this will be attributes such as courage, generosity, kindness, etc.

(Tip: if your tree is pretty crowded by this point, perhaps try drawing some baskets of fruit at the base of your tree and label them accordingly there.)

The Flowers & Seeds

Write down the legacies you wish to leave to others on the flowers and seeds.

(Tip: again, you may wish to de-clutter your drawing by visualizing saplings, baskets of flowers, etc. on which to write these items down.)

Going Further

After completing this exercise you are no doubt swimming with ideas and possibilities. My best advice is that if an idea has occurred to you that will help you process the things you have uncovered in a positive way, do it!

Here are three things that I have chosen to do as a follow up to my initial experience.

I’ve decided to journal about the various elements on my tree. I want to explore the connections between my roots, values, skills, people, etc. in a safe way before sharing it with others in any organized manner. But I do intend to share it with others. And I already know two of the ways in which I plan to.

Writing Letters

Some of the connections are pretty easy for me to determine. I know that I wrote certain values or lessons on my tree and immediately followed them up with the name of a person or group of people. These are the people who have instilled something special in me and I intend to tell them how much that means to me by writing some letters.

Meditation Through Art

I found that the drawing part of this exercise was particularly satisfying and therapeutic in and of itself. I’ve decided to follow this initial exercise up with some more study sketches of trees followed by a series of paintings and collages that express more than mere labels can. I hope to be able to share these with my friends, family, and community in the future too.

Final Thoughts

Even though I’ve spent this whole post talking about how great of an exercise this can be, I know how scary it can feel to take the first steps in claiming the storytelling rights over your life. It usually means confronting aspects of our past that we might feel are better left unchallenged. And that’s a valid concern.

If you are worried that an exercise like this might stir up a lot of raw emotion or trigger traumatic flashbacks, I would encourage you to complete this exercise with a therapist. Or, at the very least, with a friend or family member who will be there to talk to you and support you through the process.

Regardless of how you choose to complete this exercise, or what personal spins you put on it (which is half the fun!), I’d love to hear how it goes. Feel free to reach out to me about it via any of my social channels, my contact page, or the comments section below.

Want more Storytelling content?

If you liked this post and would like to get more of my blog posts about Storytelling as they come out, join my Storytelling Newsletter!

Thanks for subscribing!

57 comments.

I’m a trauma psychologist who is redoing her website and want to included referrals to sites I think might be helpful to people recovering from childhood trauma.

I really like your site and would like to recommend it to my readers. Would you be interested that? If so, I’ll send you the site when it’s presentable.

My license and ethics do not allow me to ask for an affiliate kickback, so I expect nothing from you in return.

All the best,

Victoria Bentley, PsyD

Sure I think that would be great. Reference away :)

Greetings Nathan. I’m about to draw my tree of life! At 58, soon to be 59, I moved from West Africa to work in Bahraini. I’m excited and anxious and on my own. I really want to write a book of my life journey and get it published. Would be good to talk to you about help with getting started….

Hey Donna, so happy for you! I’m a big believer in understanding and recording one’s personal story. Whether that takes the form of a journal, vlog, or something more formal like a book. I wish you the best of luck on that journey. If you would like my help I do do story consulting. I can help you walk through this exercise and several more that will help you structure your life story and plot the events of your life into a coherent narrative. To be clear up-front though, most of my consulting is with big brands and my rates reflect that. I charge between $500 and $1500 per session depending on session length and the amount of prep work that needs to take place beforehand. If that still sounds like something you’re interested in please feel free to get in touch via my contact page :)

If you’re more interested in a DIY approach then I would recommend the following resources:

Watch The Power of Myth on Netflix. It’s an extended interview of Joseph Campbell by Bill Moyers.

Joseph Campbell is THE pioneer of mythic story structure. I’d also recommend his most popular and influential book, The Hero with a Thousand Faces , but for many it’s a bit too academic.

Another great read is The Writer’s Journey by Christopher Vogler . This book is a much more accessible take on Joseph Campbell’s work written specifically for writers.

Finally, if you’re really serious, I’d recommend you read The Seven Basic Plots: Why We Tell Stories by Christopher Booker . I found that the hero’s journey tends to focus on the “quest” plot in most case studies. However, this book is excellent in helping you recognize and create your own variations represented by the other six basic plots.

At the end of my dream this morning an Asian woman I was staring at (bc I thought she was someone else) caught my glance, became excited, and whispered to her companions, “maybe she’s the identity tree”and proceeded to move toward me. I woke up with those words ringing in my ears, and, bc I’ve had enough dreams with final messages that proved to be meaningful, I jumped on google and typed the words “identity tree. Above article was the first (and last) thing I read, and everything about it rings true and right for doing right now. And I’m also beginning work with a new therapist in two hours. 🙏

Hi Nathan. I just came across this today after painting my tree of life. I love the idea & am going to do the exercise. I come from a past of negativity & dysfunction & the l lengthy traumatic (abusive!) marriage. When I looked at my finished tree of life (painted), it spoke to mr about my life. My first thought was, your not completely healed yet. It was as if I were looking at a tangled web. I would love to share it with you. It too was a great exercise. I believe we use colour, like words as a form of expression. My tree, though quite bright, is just not bright enough yet…

Hey Diane, I’m glad that you’ve found some level of healing with this exercise. It’s totally an ongoing process. I’ve done this exercise several times over the years and each time things change a bit, some things come into clearer focus, while others fade further into my past. Hope your self work continues with great results!

Hi Victoria,

my wife, Suzanne would be interested in your childhood trauma work. Her contact info is below – thank you!

What a lovely idea! I’m excited to use this activity in a women’s retreat I’m hosting this weekend. Many thanks for sharing this!

My pleasure! I’d love to hear how it goes for you. Feel free to message me via my contact page: https://nathanbweller.com/contact/

Thank you, I am glad I found your site. It was easy to read and understand. I will be sitting down to draw my own tree and use this technique in my practice. I am definitely adding The Tree of Life to my must read list and subscribing to your blog. I am a clinical social worker and would like to link and or reference your site.

Thanks Jacqueline!

Hey! Thank you for sharing this magical life tree experience, I really enjoyed doing this task, the drawing, the writing, focusing on the people who affect me the most in life. It was a great opportunity to do a zoom in for myself and focus on me especially in today world which is full of distractions. Great page and topic. Thank you for sharing! I really enjoyed it.

Thanks for sharing !!! I’m organizing an event for women and would love to use this for the event.

Hi Nathan, Thanks for much for this post! I’ve offered a Tree of Life workshop to colleagues at my workplace as a team building exercise. I’m getting ready to offer another and always like to google for more inspiration. I’m so glad to find you and your Tree of Life. I’m going to add the idea of a compost heap to my workshop. Thanks so much for your inspiration!!!

That’s awesome! I’m glad you found value here :)

I am looking forward to really delving into this website and it’s resources. The Tree of Life will be a useful tool for rebuilding identity after continuing to move through a lot of recent trauma. Funny, I thought I would’ve been through with trauma after having overcome so much. But it seems right when I get to the top of the mountain, I start to unravel again. I take responsibility for my mistakes. I just hope that I can keep my faith and channel my anger and pain in healthy ways and not toward others be a cause that’s most important to me not to do.

Thanks for sharing that Julie. I’m glad you’ve found this resource helpful. Good luck on your journey!

Loved your article and drawing the tree. I would like to utilize your ideas in a class I will teach. I would like permission to use your article in the class with reference and credit to you and your site.

Hi Marcia, yes please do. Permission granted. Thanks!

Hellos!! Such a lovely and powerful technique. Even I wanted to ask, with your permission may I too use your link and help people discover such a lovely way. I am into sound healing and a reiki master

Yep, share away :)

I am a graduate student. I would like to know if I could use your picture for a class assignment.

Sure, no problem. You can use my sketch above.

Sorry, I meant the picture at the top of the page. It is beautiful. I would love to use the sketch also. Thanks for sharing your exercise; it would be perfect for groups sessions with my students.

Oh ok, well I can’t give permission for you to use my featured image since it’s not mine to begin with. Notice I have a link giving the source credit at the bottom of my own post. However, Unsplash images are free to use in almost every single case. So I’m sure it’s fine. You’ll just need to read the terms for this image and give credit if they require it.

Hi, just saw your tree of life. Found it very useful and interesting. Kindly allow me to use it for a workshop of school leaders. I would start working upon my tree of life.

Sure no problem. You can use it :)

(It’s not mine, but I’ve used it here out of a book–as I’ve stated in the post–so I’d recommend crediting the creator of the exercise and his book.)

I love this book too! Recognising and reframing our stories is so powerful. And this is such a client-centred and gentle approach too. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks Lynne!

Hello, I hope this text finds you doing well. I am a keen learner and as a facilitator to young youths. I found this piece (exercise) very helpful and interesting. It would help all range of people understand themselves to navigate challenges in life, planning way forward and acknowledge for what they receive.

looking forward to learning more from you.

Thanks for stopping by Yeshi!

Thanks for sharing this. It’s an excellent exercise. I celebrated God’s work in my life through the tree.

Glad you liked it Paul!

Hello Nathan, My name is Paul. I love this tree exercise. It is lifegiving! I work for the Canadian Baptists. I would like to share your exercise with our pastors in our spiritual practices guide. Would it be okay if I did that? I can include a link to your webpage in our email as well. Please let me know. Thanks, Paul

Hi Paul! Yes, please feel free to share this exercise with your group. I myself borrowed this from the narrative therapy book Retelling the Stories of our Lives . That might also be a good resource for your group.

You may also wish to acknowledge Ncazelo Ncube-Mlilo, the African women who originated the Tree of Life in support of sufferers of HIV. I believe David Denborough was inspired by her idea. Also David is now the Director of the Dulwich Centre in Adelaide, South Australia. They do some wonderful work with narrative therapy. You might like to add their link your site: (I have no other association with Dulwich other than being a follower.)

Thank you for putting Ncazelo Ncube-Mlilo on my radar. I will have to learn more about her and her work.

Apologies in my previous post, I should have referred to Ncazelo Ncube-Mlilo as South African (not African).

Hi! I find this article and the tree of life exercise very useful. May I also request permission to use this in the book I am writing, of course with the required recognition of the source, should this request be approved. Thank you and may you be given more opportunities to bless others through your works.

I don’t mind if you reference my blog, however I cannot give permission for the tree of life concept as I don’t have that authority.

Hi Nathan, I am a mental health therapist and have added your ideal of the compost heap to the original tree of life exercise, may I copy your directions and site your website?

Yes, feel free to share and link back. However, please give credit for the idea to David Denborough and his book.

Thank you so much, I plan on using this for my patients and I have also cited your name.

Thank you! Please also be sure to credit the original source–the book linked above.

This concept of the TREE OF LIFE is wonderful. I have always been looking at a concept like this one – now I found it. Will translate it into the German language, as I am living in Germany, running an Institute for Humanistic Psychology since 1972, the first one in Germany. Will include this concept in my Orientation Analysis programme of training. It is meant for the counseling situation, not for psychotherapy. I also make use of the East London University papers, which give detailled information on what should be asked to fill into the Tree of Life. Thank you very much.

Glad you found this exercise so helpful! As a Humanist Celebrant I’m interested in learning more about your Institute for Humanistic Psychology.

hello Dr Kluma, can you share what the East London Unv papers are? I also want to use Tree of Life in counseling. thanks,

Hello, Nathan.

Thank you so much for your writing. Very inspiring and informative. I would like to lead an “the Tree of Life” activity in a mentoring session with young adult in South Korea. I am happy to introduce your blog and the book by David Denborough. I found out that the original book was translated into Korean but no longer available unfortunately. I hope this activity ignites deeper discussion between mentees and mentors. Thank you again for your great work.

That is incredible. Good luck!

Hi Nathan my name is Latasha Thomas from Marshall Texas. Been going through things. Find my self going bk in time been through truma. This tree of life do it work. Well I will try it once I get settled in. Some where there Peace.

I’m sorry to hear you’re going through tough times. Hope you find that peace.

Thank you for this exercise. Love it. I´m a MHP in Sweden just finnished my education in Art in therapy. Im so interested in storytelling aswell. Will follow your page.

Thank you! And good luck in your new career!