College of Arts and Sciences

History and American Studies

- What courses will I take as an History major?

- What can I do with my History degree?

- History 485

- History Resources

- What will I learn from my American Studies major?

- What courses will I take as an American Studies major?

- What can I do with my American Studies degree?

- American Studies 485

- For Prospective Students

- Student Research Grants

- Honors and Award Recipients

- Phi Alpha Theta

Alumni Intros

- Internships

Literature Review Guidelines

Literature review (historiographic essay): making sense of what has been written on your topic., goals of a literature review:.

Before doing work in primary sources, historians must know what has been written on their topic. They must be familiar with theories and arguments–as well as facts–that appear in secondary sources.

Before you proceed with your research project, you too must be familiar with the literature: you do not want to waste time on theories that others have disproved and you want to take full advantage of what others have argued. You want to be able to discuss and analyze your topic.

Your literature review will demonstrate your familiarity with your topic’s secondary literature.

GUIDELINES FOR A LITERATURE REVIEW:

1) LENGTH: 8-10 pages of text for Senior Theses (485) (consult with your professor for other classes), with either footnotes or endnotes and with a works-consulted bibliography. [See also the citation guide on this site.]

2) NUMBER OF WORKS REVIEWED: Depends on the assignment, but for Senior Theses (485), at least ten is typical.

3) CHOOSING WORKS:

Your literature review must include enough works to provide evidence of both the breadth and the depth of the research on your topic or, at least, one important angle of it. The number of works necessary to do this will depend on your topic. For most topics, AT LEAST TEN works (mostly books but also significant scholarly articles) are necessary, although you will not necessarily give all of them equal treatment in your paper (e.g., some might appear in notes rather than the essay). 4) ORGANIZING/ARRANGING THE LITERATURE:

As you uncover the literature (i.e., secondary writing) on your topic, you should determine how the various pieces relate to each other. Your ability to do so will demonstrate your understanding of the evolution of literature.

You might determine that the literature makes sense when divided by time period, by methodology, by sources, by discipline, by thematic focus, by race, ethnicity, and/or gender of author, or by political ideology. This list is not exhaustive. You might also decide to subdivide categories based on other criteria. There is no “rule” on divisions—historians wrote the literature without consulting each other and without regard to the goal of fitting into a neat, obvious organization useful to students.

The key step is to FIGURE OUT the most logical, clarifying angle. Do not arbitrarily choose a categorization; use the one that the literature seems to fall into. How do you do that? For every source, you should note its thesis, date, author background, methodology, and sources. Does a pattern appear when you consider such information from each of your sources? If so, you have a possible thesis about the literature. If not, you might still have a thesis.

Consider: Are there missing elements in the literature? For example, no works published during a particular (usually fairly lengthy) time period? Or do studies appear after long neglect of a topic? Do interpretations change at some point? Does the major methodology being used change? Do interpretations vary based on sources used?

Follow these links for more help on analyzing historiography and historical perspective .

5) CONTENTS OF LITERATURE REVIEW:

The literature review is a research paper with three ingredients:

a) A brief discussion of the issue (the person, event, idea). [While this section should be brief, it needs to set up the thesis and literature that follow.] b) Your thesis about the literature c) A clear argument, using the works on topic as evidence, i.e., you discuss the sources in relation to your thesis, not as a separate topic.

These ingredients must be presented in an essay with an introduction, body, and conclusion.

6) ARGUING YOUR THESIS:

The thesis of a literature review should not only describe how the literature has evolved, but also provide a clear evaluation of that literature. You should assess the literature in terms of the quality of either individual works or categories of works. For instance, you might argue that a certain approach (e.g. social history, cultural history, or another) is better because it deals with a more complex view of the issue or because they use a wider array of source materials more effectively. You should also ensure that you integrate that evaluation throughout your argument. Doing so might include negative assessments of some works in order to reinforce your argument regarding the positive qualities of other works and approaches to the topic.

Within each group, you should provide essential information about each work: the author’s thesis, the work’s title and date, the author’s supporting arguments and major evidence.

In most cases, arranging the sources chronologically by publication date within each section makes the most sense because earlier works influenced later ones in one way or another. Reference to publication date also indicates that you are aware of this significant historiographical element.

As you discuss each work, DO NOT FORGET WHY YOU ARE DISCUSSING IT. YOU ARE PRESENTING AND SUPPORTING A THESIS ABOUT THE LITERATURE.

When discussing a particular work for the first time, you should refer to it by the author’s full name, the work’s title, and year of publication (either in parentheses after the title or worked into the sentence).

For example, “The field of slavery studies has recently been transformed by Ben Johnson’s The New Slave (2001)” and “Joe Doe argues in his 1997 study, Slavery in America, that . . . .”

Your paper should always note secondary sources’ relationship to each other, particularly in terms of your thesis about the literature (e.g., “Unlike Smith’s work, Mary Brown’s analysis reaches the conclusion that . . . .” and “Because of Anderson’s reliance on the president’s personal papers, his interpretation differs from Barry’s”). The various pieces of the literature are “related” to each other, so you need to indicate to the reader some of that relationship. (It helps the reader follow your thesis, and it convinces the reader that you know what you are talking about.)

7) DOCUMENTATION:

Each source you discuss in your paper must be documented using footnotes/endnotes and a bibliography. Providing author and title and date in the paper is not sufficient. Use correct Turabian/Chicago Manual of Style form. [See Bibliography and Footnotes/Endnotes pages.]

In addition, further supporting, but less significant, sources should be included in content foot or endnotes . (e.g., “For a similar argument to Ben Johnson’s, see John Terry, The Slave Who Was New (New York: W. W. Norton, 1985), 3-45.”)

8 ) CONCLUSION OF LITERATURE REVIEW:

Your conclusion should not only reiterate your argument (thesis), but also discuss questions that remain unanswered by the literature. What has the literature accomplished? What has not been studied? What debates need to be settled?

Additional writing guidelines

How have History & American Studies majors built careers after earning their degrees? Learn more by clicking the image above.

Recent Posts

- History and American Studies Symposium–April 26, 2024

- Fall 2024 Courses

- Fall 2023 Symposium – 12/8 – All Welcome!

- Spring ’24 Course Flyers

- Internship Opportunity – Chesapeake Gateways Ambassador

- Congratulations to our Graduates!

- History and American Studies Symposium–April 21, 2023

- View umwhistory’s profile on Facebook

- View umwhistory’s profile on Twitter

A Brief History of the Systematic Review

- First Online: 05 August 2020

Cite this chapter

- Edward Purssell ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-3748-0864 3 &

- Niall McCrae ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-9776-7694 4

7044 Accesses

2 Citations

History is important, because it takes a longer-term view of any human enterprise. The way that we do things today might seem quaint or perhaps ethically dubious in years to come. Knowledge of the past is not merely a retrospect, but shows a direction of travel: How can we see where we are going if we don’t know where we are coming from? So let us begin by exploring how the systematic literature review evolved. What is literature, what is the purpose of reviewing such literature, and what is distinct about a systematic review?

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Shah HM, Chung KC (2009) Archie Cochrane and his vision for evidence-based medicine. Plast Reconstr Surg 124:982–988. https://doi.org/10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181b03928

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Cochrane AL (1972) Effectiveness and efficiency: random reflections on health services. Nuffield Provincial Hospitals Trust, London

Google Scholar

Cochrane A (1979) 1931–1971: a critical review, with particular reference to the medical profession. In: Medicines for the year 2000. Office of Health Economics, London

Djulbegovic B, Guyatt GH (2017) Progress in evidence-based medicine: a quarter century on. Lancet 390:415–423. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31592-6

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Le Fanu J (2011) The rise & fall of modern medicine. Abacus, London

Fisher RA (1935) Design of experiments. Oliver and Boyd, Oxford

Begg C (1996) Improving the quality of reporting of randomized controlled trials. The CONSORT statement. JAMA 276:637–639. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.276.8.637

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Moher D, Jones A, Lepage L, for the CONSORT Group (2001) Use of the CONSORT statement and quality of reports of randomized trials: a comparative before-and-after evaluation. JAMA 285:1992. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.285.15.1992

Sackett DL (1989) Rules of evidence and clinical recommendations on the use of antithrombotic agents. Chest 95:2S–4S

Guyatt GH, Sackett DL, Sinclair JC et al (1995) Users’ guides to the medical literature. IX. A method for grading health care recommendations. Evidence-Based Medicine Working Group. JAMA 274:1800–1804. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.274.22.1800

Greenhalgh T (1997) How to read a paper : getting your bearings (deciding what the paper is about). BMJ 315:243–246. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.315.7102.243

Mulrow CD (1987) The medical review article: state of the science. Ann Intern Med 106:485–488. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-106-3-485

Sacks HS, Berrier J, Reitman D et al (1987) Meta-analyses of randomized controlled trials. N Engl J Med 316:450–455. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198702193160806

Oxman AD, Guyatt GH (1993) The science of reviewing research. Ann N Y Acad Sci 703:125–133; discussion 133–134. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26342.x

Chalmers I (1993) The Cochrane collaboration: preparing, maintaining, and disseminating systematic reviews of the effects of health care. Ann N Y Acad Sci 703:156–163; discussion 163–165. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb26345.x

McKenzie JE, Brennan SE, Ryan RE , Thomson HJ, Johnston RV, Thomas J (2019) Chapter 3: Defining the criteria for including studies and how they will be grouped for the synthesis. In: Higgins JPT, Thomas J, Chandler J, Cumpston M, Li T, Page MJ, Welch VA (eds). Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions version 6.0. (updated July 2019). Cochrane. https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook

Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (ed) (2009) CRD’s guidance for undertaking reviews in healthcare, 3rd edn. York Publishing Services, York

Glass GV (1976) Primary, secondary, and meta-analysis of research. Educ Res 5:3–8. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X005010003

Article Google Scholar

Antiplatelet Trialists’ Collaboration (1988) Secondary prevention of vascular disease by prolonged antiplatelet treatment. BMJ 296:320–331. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.296.6618.320

Article PubMed Central Google Scholar

Olsson C, Ringnér A, Borglin G (2014) Including systematic reviews in PhD programmes and candidatures in nursing—“Hobson’s choice”? Nurse Educ Pract 14:102–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nepr.2014.01.005

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (2009) Overview—Depression in adults: recognition and management—Guidance—NICE. https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg90 . Accessed 17 Apr 2020

Canadian Nurses Association (2010) Evidence-informed decision making and nursing practice. In: Evidence-informed decision making and nursing practice. https://www.cna-aiic.ca/en/nursing-practice/evidence-based-practice

Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J et al (2009) Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med 6:e1000097. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Sehon SR, Stanley DE (2003) A philosophical analysis of the evidence-based medicine debate. BMC Health Serv Res 3:14. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6963-3-14

Sackett DL, Rosenberg WMC, Gray JAM et al (1996) Evidence based medicine: what it is and what it isn’t. BMJ 312:71–72. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.312.7023.71

Greenhalgh T, Toon P, Russell J et al (2003) Transferability of principles of evidence based medicine to improve educational quality: systematic review and case study of an online course in primary health care. BMJ 326:142–145. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.326.7381.142

Campbell DT, Stanley JC (1966) Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for research, 2. Reprinted from “Handbook of research on teaching”. Houghton Mifflin Comp., Boston, MA. Reprint. ISBN: 978-0-395-30787-2

McCrae N (2012) Evidence-based practice: for better or worse. Int J Nurs Stud 49:1051–1053. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2012.08.010

French P (1999) The development of evidence-based nursing. J Adv Nurs 29:72–78. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.1999.00865.x

Carper B (1978) Fundamental patterns of knowing in nursing. ANS Adv Nurs Sci 1:13–23. https://doi.org/10.1097/00012272-197810000-00004

Mackey A, Bassendowski S (2017) The history of evidence-based practice in nursing education and practice. J Prof Nurs 33:51–55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2016.05.009

McDonald L (2001) Florence Nightingale and the early origins of evidence-based nursing. Evid Based Nurs 4:68–69. https://doi.org/10.1136/ebn.4.3.68

BMJ (2016) Is The BMJ the right journal for my research article?—The BMJ. https://www.bmj.com/about-bmj/resources-authors/bmj-right-journal-my-research-article . Accessed 17 Apr 2020

Greenhalgh T, Annandale E, Ashcroft R et al (2016) An open letter to The BMJ editors on qualitative research. BMJ 352:i563. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.i563

Norman I, Griffiths P (2014) The rise and rise of the systematic review. Int J Nurs Stud 51:1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2013.10.014

Hart C (1998) Doing a literature review: releasing the social science research imagination. Sage Publications, London

Ridley D (2008) The literature review: a step-by-step guide for students. SAGE, London

Griffiths P, Norman I (2005) Science and art in reviewing literature. Int J Nurs Stud 42:373–376. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2005.02.001

Polit DF, Beck CT (2012) Nursing research: generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice, 9th edn. Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, PA

Greenhalgh T (2018) How to implement evidence-based healthcare. Wiley, Hoboken, NJ

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

School of Health Sciences, City, University of London, London, UK

Edward Purssell

Florence Nightingale Faculty of Nursing, Midwifery & Palliative Care, King’s College London, London, UK

Niall McCrae

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Edward Purssell .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2020 The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s), under exclusive license to Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Purssell, E., McCrae, N. (2020). A Brief History of the Systematic Review. In: How to Perform a Systematic Literature Review. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49672-2_2

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-49672-2_2

Published : 05 August 2020

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-49671-5

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-49672-2

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 07 March 2022

The cultural evolution of love in literary history

- Nicolas Baumard ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-1439-9150 1 ,

- Elise Huillery 2 ,

- Alexandre Hyafil ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0566-651X 3 &

- Lou Safra ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-7618-6735 1 , 4

Nature Human Behaviour volume 6 , pages 506–522 ( 2022 ) Cite this article

4731 Accesses

13 Citations

324 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Human behaviour

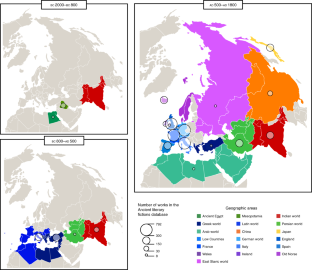

Since the late nineteenth century, cultural historians have noted that the importance of love increased during the Medieval and Early Modern European period (a phenomenon that was once referred to as the emergence of ‘courtly love’). However, more recent works have shown a similar increase in Chinese, Arabic, Persian, Indian and Japanese cultures. Why such a convergent evolution in very different cultures? Using qualitative and quantitative approaches, we leverage literary history and build a database of ancient literary fiction for 19 geographical areas and 77 historical periods covering 3,800 years, from the Middle Bronze Age to the Early Modern period. We first confirm that romantic elements have increased in Eurasian literary fiction over the past millennium, and that similar increases also occurred earlier, in Ancient Greece, Rome and Classical India. We then explore the ecological determinants of this increase. Consistent with hypotheses from cultural history and behavioural ecology, we show that a higher level of economic development is strongly associated with a greater incidence of love in narrative fiction (our proxy for the importance of love in a culture). To further test the causal role of economic development, we used a difference-in-difference method that exploits exogenous regional variations in economic development resulting from the adoption of the heavy plough in medieval Europe. Finally, we used probabilistic generative models to reconstruct the latent evolution of love and to assess the respective role of cultural diffusion and economic development.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

Improving microbial phylogeny with citizen science within a mass-market video game

Worldwide divergence of values

Song lyrics have become simpler and more repetitive over the last five decades

Data availability.

The data, as well as the the Ancient Literary Fictions Values Survey and the Ancient World Values Survey ( Romantic Love and Attitudes toward Children ), are available on OSF ( https://osf.io/ud35x ).

Code availability

The code that supports the findings of this study is available on OSF ( https://osf.io/ud35x ). A detailed description of the model for study 4 as well as MATLAB code to fit and run such models can be found on https://github.com/ahyafil/Evoked_Transmitted_Culture .

Macfarlane, A. Marriage and Love in England: Modes of Reproduction 1300–1840 (B. Blackwell, 1986).

Giddens, A. The Transformation of Intimacy: Sexuality, Love and Eroticism in Modern Societies (Wiley, 2013).

Coontz, S. Marriage, A History: How Love Conquered Marriage (Penguin, 2006).

Illouz, E. Consuming the Romantic Utopia: Love and the Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism (Univ. California Press, 1997).

Stone, L. The Family, Sex and Marriage: In England 1500–1800 (Penguin, 1977).

Rougemont, D. L. L’Amour et l’Occident (Plon, 1939).

Zink, M. Medieval French Literature: An Introduction Vol. 110 (MRTS, 1995).

Vadet, J.-C. L’esprit courtois en Orient dans les cinq premiers siècles de l’Hégire (Éditions G. P Maisonneuve Larose, 1968).

Behl, A. Love’s Subtle Magic: An Indian Islamic Literary Tradition, 1379–1545 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2016).

Meisami, J. S. Medieval Persian Court Poetry (Princeton Univ. Press, 2014).

Hsieh, D. Love and Women in Early Chinese Fiction (Chinese Univ. Press, 2008).

Walter, A. Érotique du Japon classique (Gallimard, 1994).

Duby, G. Love and Marriage in the Middle Ages (Univ. Chicago Press, 1994).

Salmon, C. The pop culture of sex: an evolutionary window on the worlds of pornography and romance. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 16 , 152 (2012).

Article Google Scholar

Kruger, D. J., Fisher, M. & Jobling, I. Proper and dark heroes as dads and cads. Hum. Nat. 14 , 305–317. (2003).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Cox, A. & Fisher, M. The Texas billionaire’s pregnant bride: an evolutionary interpretation of romance fiction titles. J. Soc. Evol. Cult. Psychol. 3 , 386 (2009).

Gottschall, J. The Rape of Troy: Evolution, Violence, and the World of Homer (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

Diamond, J. M. & Robinson J. A. Natural Experiments of History (Belknap Press, 2010).

Nunn, N. The historical roots of economic development. Science 367 , (2020).

Daumas, M. Le mariage amoureux: histoire du lien conjugal sous l’Ancien Régime (Armand Colin, 2004).

Dixon, S. The Roman Family (JHU Press, 1992).

Rawson, B. & Weaver, P. The Roman Family in Italy: Status, Sentiment, Space (Oxford Univ. Press, 1999).

Nettle, D. The wheel of fire and the mating game: explaining the origins of tragedy and comedy. J. Cult. Evol. Psychol. 3 , 39–56 (2005).

Nave, G., Rentfrow, J. & Bhatia, S. We are what we watch: movie plots predict the personalities of their fans. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/wsdu8 (2020).

van Monsjou, E. & Mar, R. A. Interest and investment in fictional romances. Psychol. Aesthet. Creat. Arts 13 , 431 (2019).

Dubourg, E., Thouzeau, V., de Dampierre, C. & Baumard, N. Exploratory preferences explain the cultural success of imaginary worlds in modern societies. Preprint at PsyArXiv https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/d9uqs (2021).

Rikhardsdottir, S. Medieval Translations and Cultural Discourse: The Movement of Texts in England, France and Scandinavia (DS Brewer, 2012).

Fletcher, G. J., Simpson, J. A., Campbell, L. & Overall, N. C. Pair-bonding, romantic love, and evolution: the curious case of Homo sapiens . Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 10 , 20–36 (2015).

Buss, D. M. in The New Psychology of Love (eds Sternberg, R. J. & Weis, K.) 65–86 (Yale Univ. Press, 2006).

Baumard, N. From Chariclea and Theagen to Cui Yingying and Zhang Sheng: How romantic fictions inform us about the cultural evolution of pair-bonding in Eurasia OSF https://osf.io/sx45k/ (2021).

Pinker, S. Toward a consilient study of literature. Phil. Lit. 31 , 162–178 (2007).

Google Scholar

Dubourg, E. & Baumard, N. Why imaginary worlds?: the psychological foundations and cultural evolution of fictions with imaginary worlds. Behav. Brain Sci . 1–52 (2021).

Stark, I. in Antike Roman. Untersuchungen zur literarischen Kommunikation und Gattungsgeschichte (ed. Kuch, H.) (Akademie, 1989).

Konstan, D. Sexual Symmetry: Love in the Ancient Novel and Related Genres (Princeton Univ. Press, 2014).

Song, G. The Fragile Scholar: Power and Masculinity in Chinese Culture Vol. 1 (Hong Kong Univ. Press, 2004).

McEvedy, C. & Jones, R. Atlas of World Population History (Penguin Books, 1978).

Fantuzzi, M. Achilles in Love: Intertextual Studies (OUP Oxford, 2012).

Symes, C. in A Handbook to the Reception of Greek Drama (ed. van Zyl Smit, B.) Chap. 6 (Wiley, 2016).

Mesoudi, A. & Whiten, A. The multiple roles of cultural transmission experiments in understanding human cultural evolution. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 363 , 3489–3501 (2008).

Ravignani, A., Delgado, T. & Kirby, S. Musical evolution in the lab exhibits rhythmic universals. Nat. Hum. Behav. 1 , 0007 (2017).

Fessler, D. M., Pisor, A. C. & Navarrete, C. D. Negatively-biased credulity and the cultural evolution of beliefs. PLoS ONE 9 , e95167 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Miton, H., Claidière, N. & Mercier, H. Universal cognitive mechanisms explain the cultural success of bloodletting. Evol. Hum. Behav. 36 , 303–312 (2015).

Shifu, W. The Story of the Western Wing (Univ. California Press, 1995).

Cooper, H. The English Romance in Time: Transforming Motifs from Geoffrey of Monmouth to the Death of Shakespeare (Oxford Univ. Press, 2004).

Lauriola, R. & Demetriou, K. N. Brill’s Companion to the Reception of Sophocles (Brill, 2017).

Kalinke, M. E. The Arthur of the North: The Arthurian Legend in the Norse and Rus’ Realms (Univ. Wales Press, 2011).

Lindahl, C. Yvain’s return to Wales. Arthuriana 10 , 44–56 (2000).

Yiavis, K. in Fictional Storytelling in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean and Beyond (eds Cupane, C., & Krönung, B.) 127–156 (Brill, 2016).

Elias, N. The Civilizing Process 1st American Edition (Urizen Books, 1978).

Veyne, P. La famille et l’amour sous le Haut-Empire romain. Annales. Histoire, Sciences Sociales 33 35–63 (1978).

Bloch, M. L. B. La société féodale: les classes et le gouvernement des hommes Vol. 4 (Albrin Michel, 1940).

White, L. T. Medieval Technology and Social Change (Oxford Univ. Press, 1962).

Andersen, T. B., Jensen, P. S. & Skovsgaard, C. V. The heavy plow and the agricultural revolution in Medieval Europe. J. Dev. Econ 118 , 133–149 (2016).

Boase, R. The Origin and Meaning of Courtly Love: A Critical Study of European Scholarship (Manchester Univ. Press, 1977).

Gallais, P. Genèse du roman occidental: essais sur Tristan et Iseut et son modèle persan Vol. 1 (Tête de feuilles-Sirac, 1974).

Cormier, R. J. Open contrast: Tristan and Diarmaid. Speculum. 51 , 589–601 (1976).

Tooby, J. & Cosmides, L. in The Adapted Mind: Evolutionary Psychology and the Generation of Culture (eds Barkow, J. H, Cosmides, L. & Tooby, J.) Ch. 12 (Oxford Univ. Press, 1992).

Nettle, D. Beyond nature versus culture: cultural variation as an evolved characteristic. J. R. Anthropol. Inst. 15 , 223–240 (2009).

Bishop, C. M. Pattern Recognition and Machine Learning (Springer, 2006).

Reynier, G. Le roman sentimental avant l’Astrée (A. Colin, 1908).

Pan, L. When True Love Came to China (Hong Kong Univ. Press, 2015).

Goody, J., Goody, J. R. Food and Love: A Cultural History of East and West (Verso, 1998).

Gregor, T. Anxious Pleasures (Univ. Chicago Press, 2008).

Hanan, P. Falling in Love: Stories from Ming China (Univ. Hawaii Press, 2017).

Kaplan, H. S., Hooper, P. L. & Gurven, M. The evolutionary and ecological roots of human social organization. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. B 364 , 3289–3299 (2009).

Quinlan, R. J. & Quinlan, M. B. Parenting and cultures of risk: a comparative analysis of infidelity, aggression, and witchcraft. Am. Anthropol. 109 , 164–179 (2007).

Li, H. & Zheng, L. Associations between early life harshness, parents’ parenting style, and relationship quality in China. Pers. Relatsh 28 , 998–1016 (2021).

Quinlan, R. J. Human parental effort and environmental risk. Proc. R. Soc. B 274 , 121–125 (2007).

Ariès, P. Centuries of Childhood (Penguin Harmondsworth, 1962).

Stearns, P. N. Childhood in World History (Routledge, 2016).

Harper, K. The sentimental family: a biohistorical perspective. Am. Hist. Rev. 119 , 1547–1562 (2014).

Goody, J. The Development of the Family and Marriage in Europe (Cambridge Univ. Press, 1983).

Reddy, W. M. The Making of Romantic Love: Longing and Sexuality in Europe, South Asia, and Japan, 900–1200 CE (Univ. Chicago Press, 2012).

Brooke, C. N. L. The Medieval Idea of Marriage (Oxford Univ. Press, 1991).

McDougall, S. The making of marriage in medieval France. J. Fam. Hist. 38 , 103–121 (2013).

Baumard, N., Hyafil, A., Morris, I. & Boyer, P. Increased affluence explains the emergence of ascetic wisdoms and moralizing religions. Curr. Biol. 25 , 10–15 (2015).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Inglehart, R. Cultural Evolution: People’s Motivations are Changing, and Reshaping the World (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2018).

Baumard, N. Psychological origins of the industrial revolution. Behav. Brain Sci. 42 , 1–47 (2018).

Pepper, G. V., & Nettle, D. The behavioural constellation of deprivation: causes and consequences. Behav. Brain Sci. 40 , E314 (2017).

Haushofer, J. & Fehr, E. On the psychology of poverty. Science 344 , 862–867 (2014).

Postel, P. The novel and sentimentalism in seventeenth and eighteenth-century Europe and China: a modest proposal for comparing early modern literatures. J. Early Mod. Cult. Stud. 17 , 6–37 (2017).

Duby, G. Dames du XIIe siècle (Tome 1)-Héloïse, Aliénor, Iseut et quelques autres 1st Edition (Gallimard, 2013).

Boyer, P. Minds Make Societies (Yale Univ. Press, 2018).

Sperber, D. Explaining Culture: A Naturalistic Approach (Wiley-Blackwell, 1996).

Bossler, B. in Beyond Exemplar Tales: Women’s Biography in Chinese History (eds Judge, J. & Hu, Y.) 158–174 (Univ. California Press, 2011).

Chisholm, J. S., Quinlivan, J. A., Petersen, R. W. & Coall, D. A. Early stress predicts age at menarche and first birth, adult attachment, and expected lifespan. Hum. Nat. 16 , 233–265 (2005).

Lovén, L. L. in Oxford Handbook of Childhood Education in the Classical World (eds Evans Grubbs, J. & Parkin, T.)Ch. 15 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2013).

Rawson, B. Children and Childhood in Roman Italy (OUP Oxford, 2003).

Wu, P. in Chinese Views of Childhood (ed. Behnke Kinney, A.) 129–156 (Univ. Hawaii Press, 1995).

Gaffney, P. Constructions of Childhood and Youth in Old French Narrative (Routledge, 2016).

Gibert, J. Falling in love with Euripides (« Andromeda »). Ill Class Stud. 24 , 75–91 (1999).

Walcot, P. Romantic love and true love: Greek attitudes to marriage. Anc. Soc. 18 , 5–33 (1987).

Segal, C. The two worlds of Euripides’ Helen. Trans. Proc. Am. Phil. Assoc. 102 , 553–614 (1971).

Rudd, N. Romantic love in classical times? Ramus 10 , 140–158 (1981).

Dickemann, M. in Natural Selection and Social Behavior (eds Alexander, R. & Tinkle D.) 417–438 (Chiron Press, 1981).

Betzig, L. Roman polygyny. Ethol. Sociobiol. 13 , 309–349 (1992).

Betzig, L. Medieval monogamy. J. Fam. Hist. 20 , 181–216 (1995).

Hanan, P. Falling in Love: Stories from Ming China (Univ. Hawaii Press, 2006).

Leung, A. K. L’Amour en Chine. Relations et pratiques sociales aux XIIIe et XIVe siècles. Arch. Sci. Soc. Relig. 56 , 59–76 (1983).

Sommer, M. H. Sex, Law, and Society in Late Imperial China (Stanford Univ. Press, 2000).

Martins, M., de, J. D. & Baumard, N. The rise of prosociality in fiction preceded democratic revolutions in Early Modern Europe. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 117 , 28684–28691 (2020).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Bowman, A. & Wilson, A. Settlement, Urbanization, and Population Vol. 2 (Oxford Univ. Press, 2011).

de Ligt, L. Peasants, Citizens and Soldiers: Studies in the Demographic History of Roman Italy 225 bc–ad 100 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012).

Aurell, M. La légende du roi Arthur: 550 – 1250 (Perrin, 2006).

Michalopoulos, S. & Xue, M. M. Folklore. Q. J. Econ . 1–54 (2021).

Whitmarsh, T. The Cambridge Companion to the Greek and Roman Novel (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

Hunter, R. in The Cambridge Companion to the Greek and Roman Novel (ed. Whitmarsh, T.) Ch. 15 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

Darnton, R. The Great Cat Massacre: And Other Episodes in French Cultural History (Basic Books, 2009).

Biraud, M. L’Eroticos de Plutarque et les romans d’amour: échos et écarts (Rursus-Spicae Transm Récept Réécriture Textes L’Antiquité Au Moyen Âge, 2009).

Schama, S. Citizens: A Chronicle of the French Revolution (Penguin, 2004).

Whitmarsh, T. Prose fiction. Companion Hell Lit . 395–411 (2010).

Willinsky, J. in Emerging Digital Spaces in Contemporary Society (eds Kalantzis-Cope, P. & Gherab-Martín, K.) Part VII, Chap. 7 (Springer, 2010).

Mesgari, M., Okoli, C., Mehdi, M., Nielsen, F. Å. & Lanamäki, A. “The sum of all human knowledge”: a systematic review of scholarly research on the content of Wikipedia. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 66 , 219–245 (2015).

Nielsen, F. AArup. Scientific citations in Wikipedia. Preprint at https://arxiv.org/abs/0705.2106v1 (2007).

Gies, D. T. The Cambridge History of Spanish Literature (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2004).

Bowman, A., Wilson, A. Settlement, Urbanization, and Population (Oxford Univ. Press on Demand, 2011).

Maddison, A. The World Economy Volume 1: A Millennial Perspective Volume 2: Historical Statistics (Academic Foundation, 2007).

Bowman, A. K., Garnsey P. & Rathbone D. The Cambridge Ancient History (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2008).

Ober, J. The Rise and Fall of Classical Greece (Princeton Univ. Press, 2015).

Bassino, J.-P., Broadberry, S. N., Fukao, K., Gupta, B. & Takashima, M. Japan and the Great Divergence, 730–1874 . Explor. Econ. Hist. 72 . 1–22 (2019).

Songdi, W. & Jianxiong, G. The History of Chinese Population Vol. 3 (Fudan Univ. Press, 2000).

Xu, Y., van Leeuwen, B. & van Zanden, J. L. Urbanization in China, ca. 1100–1900 (CGEH Work Pap Ser, 2015).

Deng, K. G. Unveiling China’s true population statistics for the Pre-Modern Era with official census data. Popul. Rev. 43 , 32–69 (2004).

Bosker, M., Buringh, E. & van Zanden, J. L. From Baghdad to London: unraveling urban development in Europe, the Middle East, and North Africa, 800–1800. Rev. Econ. Stat. 95 , 1418–1437 (2013).

Bairoch, P., Batou, J. & Chevre, P. The Population of European Cities from 800 to 1850 (Droz, 1988).

Chandler, T. Four Thousand Years of Urban Growth: An Historical Census (Mellen, 1987).

Campbell, B. M. Benchmarking medieval economic development: England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland, c. 1290 1. Econ. Hist. Rev. 61 , 896–945 (2008).

Dimmock, S. Reassessing the towns of southern Wales in the later middle ages. Urban Hist. 32 , 33–45 (2005).

Morris, I. The Measure of Civilization: How Social Development Decides the Fate of Nations (Princeton Univ. Press, 2013).

De Ligt, L. Peasants, Citizens and Soldiers: Studies in the Demographic History of Roman Italy 225 bc – ad 100 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2012).

Broadberry, S., Guan, H. & Li, D. D. China, Europe and the Great Divergence: A Study in Historical National Accounting, 980–1850 (Cambridge Univ. Press, 2014).

Ridolfi, L. The French economy in the longue durée: a study on real wages, working days and economic performance from Louis IX to the Revolution (1250–1789). Eur. Rev. Econ. Hist. 21 , 437–438 (2017).

Pamuk, Ş. & Shatzmiller, M. Plagues, wages, and economic change in the Islamic Middle East, 700–1500. J. Econ. Hist. 74 , 196–229 (2014).

Amemiya, T. Economy and Economics of Ancient Greece (Routledge, 2007).

Milanovic, B. Income level and income inequality in the Euro-Mediterranean region: from the Principate to the Islamic conquest. Preprint at SRRN https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=2265877 (2013).

van Leeuwen, B., Izdebski, A., Liu, G., Yi, X. & Foldvari, P. Bridging the gap: agrarian roots of economic divergence in Eurasia up to the late middle ages. In Proc. World Economic History Congress 2012; https://www.cgeh.nl/sites/default/files/bridgegap%20%281%29.pdf

Goldsmith, R. W. An estimate of the size ANL structure of the national product of the early Roman empire. Rev. Income Wealth 30 , 263–288 (1984).

Temin, P. Estimating GDP in the early Roman Empire. Innov Tec E Prog Econ Nel Mondo Romano. 2006;31–54.

Maddison, A. Contours of the World Economy 1–2030 AD: Essays in Macro-Economic History. (Oxford Univ. Press, 2007).

Milanovic, B., Lindert, P. H. & Williamson, J. G. Measuring ancient inequality. Preprint at NBER http://www.nber.org/papers/w13550 (2007).

Scheidel, W. & Friesen, S. J. The size of the economy and the distribution of income in the Roman Empire. J. Roman Stud. 99 , 61–91 (2009).

Cascio, E. L. & Malanima, P. GDP in pre-modern agrarian economies (1–1820 ad ). A revision of the estimates. Riv. Storia Econ. 25 , 391 (2009).

Kay, P. Rome’s Economic Revolution (OUP Oxford, 2014).

Holt, R. What if the Sea were different? Urbanization in medieval Norway. Past Present 195 , 132–147 (2007).

Taagepera, R. Size and duration of empires growth-decline curves, 3000 to 600 bc . Soc. Sci. Res. 7 , 180–196 (1978).

Taagepera, R. Size and duration of empires: systematics of size. Soc. Sci. Res. 7 , 108–127 (1978).

Gergaud, O., Laouenan, M. & Wasmer, E. A Brief History of Human Time. Exploring a database of ” notable people”. LIEPP Working Paper, Laboratoire interdisciplinaire d’évaluationdes politiques publiques (LIEPP, Sciences Po, 2016); https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01440325/

Rebele, T., Nekoei, A. & Suchanek, F. M. Using YAGO for the Humanities. In Proc. Second Workshop Humanit. Semant. Web Conf. (eds Adamou, A., Daga, E. & Ikasen, L.) 99–110 (CEUR-WS, 2017).

Schich, M. et al. A network framework of cultural history. Science 345 , 558–562 (2014).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank P. Boyer, C. Chevallier, L. Cronk, H. Mercier, O. Morin and M. Singh for their comments and feedback on the draft. We thank S. Joye, M. White-Le Goff, M. Daumas, W. Reddy, K. Zakharia, E. Feuillebois-Pierunek, D. Struve and C. Svatek for their feedback on the design of the project, and S. Joye for her help in kickstarting the project. We thank T. Ansart for his help and advice in designing the figures. For their expertise in history of literature and their reading the Ancient Literary Fictions Values Survey, we thank M. Balda-Tillier, G. Barnes, B. Brosser, S. Brocquet, J.-B. Camps, N. Cattoni, M. Childs, C. Cleary, B. Cook, H. Cooper, M. Eggertsdóttir, W. Farris, E. Francis, H. Frangoulis, H. Fulton, G. Fussman, D. Goodall, I. Hassan, L. Haiyan, D. Hsieh, A. Inglis, C. Jouanno, R. Keller Kimbrough, J. D. Konstan, R. Lanselle, R. Luzi, M. Luo, R. Martin, D. Matringue, K. McMahon, G. Nagy, P. Nagy, H. Navratilova, D. Negers, P. Orsatti, F. Orsini, S. Ríkharðsdóttir, F. Schironi, S. Valeria, C. Starr, R. Torrella and S. Torres Pietro. Funding: This study was supported by the Institut d’Études Cognitives (ANR-17-EURE-0017 FrontCog and ANR-10-IDEX-0001-02 PSL) for N.B. and L.S., and by the Spanish Ministry of Economy and Competitiveness (RYC-2017-2323) for A.H.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Institut Jean Nicod, Département d’études cognitives, ENS, EHESS, PSL Research University, CNRS, Paris, France

Nicolas Baumard & Lou Safra

Laboratoire d’Economie de Dauphine, Université Paris Dauphine, PSL Research University, Paris, France

Elise Huillery

Centre de Recerca Matemàtica, Bellaterra, Spain

Alexandre Hyafil

Sciences Po, CEVIPOF, CNRS, Paris, France

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

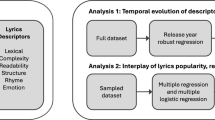

N.B. conceived the project, supervised the creation of the Ancient Literary Fictions Database and wrote the Ancient Literary Fictions Values Survey. L.S. and A.H. designed the analyses for study 1. L.S. designed the analyses for study 2. E.H. designed the difference-in-difference for study 3. A.H. designed the latent probabilistic generative models for study 4. All authors wrote the paper.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Nicolas Baumard .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Trine Bille, Peter Sandholt Jensen and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplementary Figs. 1–10 and Tables 1–26.

Reporting Summary.

Rights and permissions.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Baumard, N., Huillery, E., Hyafil, A. et al. The cultural evolution of love in literary history. Nat Hum Behav 6 , 506–522 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01292-z

Download citation

Received : 11 February 2021

Accepted : 06 January 2022

Published : 07 March 2022

Issue Date : April 2022

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-022-01292-z

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Scene clusters, causes, spatial patterns and strategies in the cultural landscape heritage of tang poetry road in eastern zhejiang based on text mining.

Heritage Science (2023)

Exploratory preferences explain the human fascination for imaginary worlds in fictional stories

- Edgar Dubourg

- Valentin Thouzeau

- Nicolas Baumard

Scientific Reports (2023)

Money’s mutation of the modern moral mind: The Simmel hypothesis and the cultural evolution of WEIRDness

- Cameron Harwick

Journal of Evolutionary Economics (2023)

Reproductive Strategies and Romantic Love in Early Modern Europe

- Mauricio de Jesus Dias Martins

Archives of Sexual Behavior (2023)

Modernization, collectivism, and gender equality predict love experiences in 45 countries

- Piotr Sorokowski

- Marta Kowal

- Agnieszka Sorokowska

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Applying Critical Thinking

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: Apr 29, 2024 1:49 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

Purdue Online Writing Lab Purdue OWL® College of Liberal Arts

Writing a Literature Review

Welcome to the Purdue OWL

This page is brought to you by the OWL at Purdue University. When printing this page, you must include the entire legal notice.

Copyright ©1995-2018 by The Writing Lab & The OWL at Purdue and Purdue University. All rights reserved. This material may not be published, reproduced, broadcast, rewritten, or redistributed without permission. Use of this site constitutes acceptance of our terms and conditions of fair use.

A literature review is a document or section of a document that collects key sources on a topic and discusses those sources in conversation with each other (also called synthesis ). The lit review is an important genre in many disciplines, not just literature (i.e., the study of works of literature such as novels and plays). When we say “literature review” or refer to “the literature,” we are talking about the research ( scholarship ) in a given field. You will often see the terms “the research,” “the scholarship,” and “the literature” used mostly interchangeably.

Where, when, and why would I write a lit review?

There are a number of different situations where you might write a literature review, each with slightly different expectations; different disciplines, too, have field-specific expectations for what a literature review is and does. For instance, in the humanities, authors might include more overt argumentation and interpretation of source material in their literature reviews, whereas in the sciences, authors are more likely to report study designs and results in their literature reviews; these differences reflect these disciplines’ purposes and conventions in scholarship. You should always look at examples from your own discipline and talk to professors or mentors in your field to be sure you understand your discipline’s conventions, for literature reviews as well as for any other genre.

A literature review can be a part of a research paper or scholarly article, usually falling after the introduction and before the research methods sections. In these cases, the lit review just needs to cover scholarship that is important to the issue you are writing about; sometimes it will also cover key sources that informed your research methodology.

Lit reviews can also be standalone pieces, either as assignments in a class or as publications. In a class, a lit review may be assigned to help students familiarize themselves with a topic and with scholarship in their field, get an idea of the other researchers working on the topic they’re interested in, find gaps in existing research in order to propose new projects, and/or develop a theoretical framework and methodology for later research. As a publication, a lit review usually is meant to help make other scholars’ lives easier by collecting and summarizing, synthesizing, and analyzing existing research on a topic. This can be especially helpful for students or scholars getting into a new research area, or for directing an entire community of scholars toward questions that have not yet been answered.

What are the parts of a lit review?

Most lit reviews use a basic introduction-body-conclusion structure; if your lit review is part of a larger paper, the introduction and conclusion pieces may be just a few sentences while you focus most of your attention on the body. If your lit review is a standalone piece, the introduction and conclusion take up more space and give you a place to discuss your goals, research methods, and conclusions separately from where you discuss the literature itself.

Introduction:

- An introductory paragraph that explains what your working topic and thesis is

- A forecast of key topics or texts that will appear in the review

- Potentially, a description of how you found sources and how you analyzed them for inclusion and discussion in the review (more often found in published, standalone literature reviews than in lit review sections in an article or research paper)

- Summarize and synthesize: Give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: Don’t just paraphrase other researchers – add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically Evaluate: Mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: Use transition words and topic sentence to draw connections, comparisons, and contrasts.

Conclusion:

- Summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance

- Connect it back to your primary research question

How should I organize my lit review?

Lit reviews can take many different organizational patterns depending on what you are trying to accomplish with the review. Here are some examples:

- Chronological : The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time, which helps familiarize the audience with the topic (for instance if you are introducing something that is not commonly known in your field). If you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order. Try to analyze the patterns, turning points, and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred (as mentioned previously, this may not be appropriate in your discipline — check with a teacher or mentor if you’re unsure).