- Place order

How to write a First Person Essay and Get a Good Grade

First-person essays are fun essays to write. The reason is that they are usually written in the first-person perspective. In this article, you will discover everything crucial you need to know about first-person essay writing.

By reading this article, you should be able to write any first-person essay confidently. However, if you need assistance writing any first-person essay, you should order it from us. We have competent writers who can write any first-person essay and deliver ASAP.

What is a first-person Essay?

A first-person essay is an academic writing task written from the first-person perspective. A typical first-person essay will involve the author describing a personal experience. This is the reason why first-person essays are also known as personal essays .

Since first-person essays are personal, they are usually written in a casual tone and from the first-person point of view. However, there are occasions when such essays must be written in a formal tone (calling for using citations and references). Nevertheless, as stated, they are often written in a casual tone.

The best first-person essays are those with a casual tone and a solid first-person point of view (POV). A casual tone is a conversational tone or a non-formal tone.

And a solid first-person POV writing is writing that is characterized by the generous use of first-person pronouns, including “I,” “me,” and “we.” It differs from the academic third-person POV writing that is characterized by the use of third-person pronouns such as “her,” “he,” and “them.”

Types of First-person Essays

There are several types of first-person essays in the academic world. The most popular ones include admission essays, reflective essays, scholarship essays, statement of purpose essays, personal narrative essays, and memoirs.

1. Admission essays

An admission essay, a personal statement, is a first-person essay that potential students write when applying for admission at various universities and colleges. Most universities and colleges across the US require potential students to write an admission essay as part of their college application.

They do this better to understand students beyond their academic and extracurricular achievements. As a result, the best college admission essays are often descriptive, honest, introspective, meaningful, engaging, and well-edited.

2. Reflective essays

A reflective essay is a first-person essay in which the author recalls and evaluates an experience. The objective of the evaluation is usually to determine whether an experience yielded any positive or negative change. Professors typically ask students to write reflective essays to encourage critical thinking and promote learning.

Reflective essays can be written in various styles. The most popular style is the conventional introduction-body-conclusion essay writing style. The best reflective essays follow this style. In addition, they are introspective, precise, well-structured, and well-edited.

3. Scholarship essays

A scholarship essay is a first-person essay you write to get a scholarship. Most competitive scholarships require students to submit an essay as part of their application. The scholarship essay submitted is one of the things they use to determine the scholarship winner.

Usually, when scholarship committees ask applicants to write a scholarship essay, they expect the applicants to explain what makes them the most suitable candidates/applicants for the scholarship. Therefore, when you are asked to write one, you should do your best to explain what makes you deserve the scholarship more than anyone else.

The best scholarship essays are those that are honest, direct, useful, and precise. They also happen to be well-edited and well-structured.

4. Statement of purpose essays

A statement of purpose essay is a first-person essay that graduate schools require applicants to write to assess their suitability for the programs they are applying to. A statement of purpose is also known as a statement of intent. The typical statement of purpose is like a summary of an applicant’s profile, including who they are, what they have done so far, what they hope to achieve, and so on.

When you are asked to write a statement of purpose essay, you should take your time to assess what makes you a good candidate for the program you want to join. You should focus on your relevant academic achievements and what you intend to achieve in the future. The best statement of purpose essays is those that are well-structured, well-edited, and precise.

5. Personal narrative essays

A personal narrative essay is a first-person essay in which the author shares their unique experience. The most successful personal narrative essays are those that have an emotional appeal to the readers. You can create emotional appeal in your personal narrative essay by using vivid descriptions that will help your readers strongly relate to what you are talking about. You can also create emotional appeal in your personal narrative essay by generously using imageries.

The typical personal narrative essay will have three parts: introduction-body-conclusion. In addition, the best ones usually have good descriptions of various settings, events, individuals, etc. Therefore, to write an excellent personal narrative essay, you should focus on providing a detailed and engaging description of whatever you are talking about.

A memoir is a first-person essay written to provide a detailed historical account. Memoirs are usually written to share confidential or private knowledge. Retired leaders often write memoirs to give a historical account of their leadership era from their perspective.

You may not be worried about the prospect of being asked to write a memoir as a college student, but it is good to know about this type of first-person essay. It may be helpful to you in the future. Moreover, you can always write a memoir to be strictly read by your family or friends.

Structure and Format of a First-Person Essay

You are not required to follow any specific format when penning a first-person essay. Instead, you need to write it just like a standard format essay . In other words, ensure your essay has an introduction, a body, and a conclusion.

1. Introduction

Your essay must have a proper introduction paragraph. An introduction paragraph is a paragraph that introduces the readers to what the essay is all about. It is what readers will first read and decide whether to continue reading the rest of your essay. Thus, if you want your essay to be read, you must get the introduction right.

The recommended way to start an essay introduction is to begin with an attention-grabbing sentence. This could be a fact related to the topic or a statistic. By starting your essay with an attention-grabbing sentence, you significantly increase the chances of readers deciding to read more.

After the attention-grabbing sentence, you must include background information on what you will discuss. This information will help your readers know what your essay is about early on.

The typical essay has a body. It is in the body that all the important details are shared. Therefore, do not overshare in the introduction when writing a first-person essay. Instead, share your important points or descriptions in the body of your essay.

The best way to write the body of your first-person essay is first to choose the most important points to talk about in your essay. After doing this, you are supposed to write about each point in a different paragraph. Doing this will make your work structured and easier to understand.

The best way to write body paragraphs is, to begin with, a topic sentence that sort of declares what the writer is about to write. You should then follow this with supporting evidence to prove your point. Lastly, you should finish your body paragraph with a closing sentence that summarizes the main point in the paragraph and provides a smooth transition to the next paragraph.

3. Conclusion

At the end of your first-person essay, you must offer a conclusion for the first-person essay to be complete. The conclusion should restate the thesis of your essay and its main points. And it should end with a closing sentence that wraps up your entire essay.

Steps for Writing a First-Person Essay

If you have been asked to write a first-person essay, you should simply follow the steps below to write an excellent first-person essay of any type.

1. Choose a topic

The first thing you need to do before you start writing a first-person essay is to choose a topic. Selecting a topic sounds like an easy thing to do, but it can be a bit difficult. This is because of two things. One, it is difficult for most people to decide what to write about quickly. Two, there is usually much pressure to choose a topic that will interest the readers.

While it is somewhat challenging to choose a topic, it can be done. You simply need to brainstorm and write down as many topics as possible and then eliminate the dull ones until you settle on a topic that you know will interest your readers.

2. Choose and stick to an essay tone

Once you choose a topic for your essay, you must choose a tone and maintain that tone throughout your essay. For example, if you choose a friendly or casual tone, you should stick to it throughout your essay.

Choosing a tone and sticking to it will make your essay sound consistent and connected. You will also give your essay a nice flow.

3. Create an outline

Once you have chosen a topic and chosen a tone for your essay, you should create an outline. The good news about creating an outline for a first-person essay is that you do not have to spend much time doing research online or in a library. The bad news is that you will have to brainstorm to create a rough sketch for your essay.

The easiest way to brainstorm to create a rough sketch for your essay is to write down the topic on a piece of paper and create a list of all the important points relevant to the topic. Make sure your list is as exhaustive as it can be. After doing this, you should identify the most relevant points to the topic and then arrange them chronologically.

Remember, a first-person essay is almost always about you telling a story. Therefore, make sure your points tell a story. And not just any story but an interesting one. Thus, after identifying the relevant points and arranging them chronologically, brainstorm and note down all the interesting details you could use to support them. It is these details that will help to make your story as enjoyable as possible.

3. Write your first draft

After creating your outline, the next thing to do is to write your first draft. Writing the first draft after creating a comprehensive outline is much easier. Consequently, simply follow the outline you created in the previous step to writing your first draft. You already arranged the most relevant points chronologically, so you shouldn’t find it challenging to write your first draft.

When writing this first draft, remember that it should be a good story. In other words, ensure your first draft is as chronological as possible. This will give it a nice flow and make it look consistent. When writing the first draft, you will surely remember new points or details about your story. Feel free to add the most useful and interesting ones.

4. Edit your essay

After writing your first draft, you should embark on editing it. The first thing you need to edit is the flow. Make sure your first draft has a nice flow. To do this, you will need to read it. Do this slowly and carefully to find any gaps or points of confusion in your draft. If you find them, edit them to give your story a nice flow.

The second thing you need to edit is the tone. Make sure the draft has a consistent tone throughout. Of course, ensure it is also in first-person narrative from the first paragraph to the last. The third thing you need to edit is the structure. Ensure your essay has a good structure with three parts: introduction, body, and conclusion.

5. Proofread your essay

After ensuring your essay has a nice flow, a consistent tone, and a good structure, you should proofread it. The purpose of doing this is to eliminate all the grammar errors, typos, and other writing mistakes. And the best way to do it is to read your essay aloud.

Reading your essay aloud will help you catch writing errors and mistakes. However, you should also proofread your essay using an online editor such as Grammarly.com to catch all the writing errors you may have missed.

After proofreading your essay, it will be crisp and ready for submission.

Topic ideas for a first-person essay

Below are some topic ideas for first-person essays. Since there are several distinct types of first-person essays, the ideas below may not be relevant to some types of first-person essays. However, the list below should give you a good idea of common first-person essay topics.

- A story about losing a friend

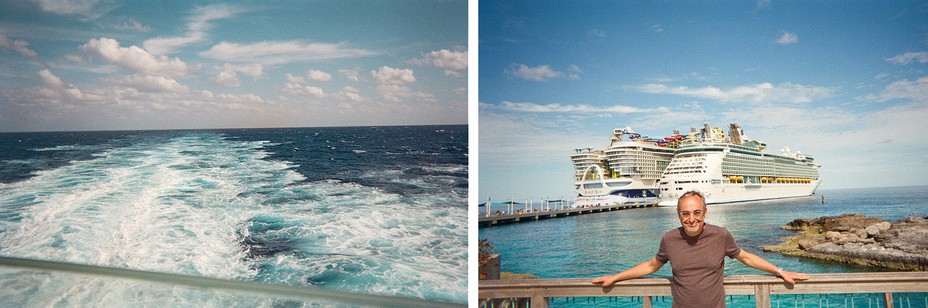

- A story about your first foreign trip

- A story about the best thing that happened to you

- A dangerous experience that happened to you

- A high school friend you will never forget

- A story about how you learned a new skill

- The most embarrassing thing that happened to you

- The first time you cooked your own meal

- The first time you did something heroic

- The first time you helped someone in need

- Your first job

- The most fun you’ve ever had

- The scariest thing that ever happened to you

- A day you will never forget

- The biggest life lesson you have learned

- How you met your best friend

- Your first time driving a car

- Your first time, feel depressed and lost

- A story from a vacation trip

- Your cultural identity

Sample Outline of a First-person Essay

Below is a sample outline of a first-person essay. Use it to create your first-person essay outline when you need to write a first-person essay.

- Attention-grabbing sentence

- Background info

- Thesis statement

- Body Paragraph 1

- First major point

- Closing sentence

2. Body Paragraph 2

- Second major point

3. Body Paragraph 3

- Third major point

4. Conclusion

- Thesis restatement

- Summary of major points

- Concluding statement

Example of a first-person essay

My First Job Your first job is like your first kiss; you never really forget it, no matter how many more you get in the future. My first job will always be remarkable because of the money it gave me and how useful it made me feel. About two weeks after my 17 th birthday, my mother asked me if I could consider taking a job at a small family restaurant as a cleaner. I agreed. I could say no if I wanted to, but I didn’t. My mother was a single mother working two jobs to care for my three younger siblings and me. She always came back home tired and exhausted every single day. I had always wanted to help her, and as soon as the opportunity presented itself, I grabbed it with my two hands. My mother had heard about the cleaner job from a close friend; hence she hoped I could do it to earn money for our family. Once I agreed, I went to the restaurant the next day. I took the train and arrived at about seven in the morning. The restaurant was already packed at this time, with the workers running around serving breakfast. I asked to speak to someone about the cleaning job, and I was soon at the back office getting instructions about the job. Apparently, I was the first to show genuine interest in taking the job. For the first three days, the other staff showed me around, and after that, I started cleaning the restaurant daily at $8 an hour. Now $8 an hour may seem like little money to most people, but to me, it meant the world! It was money I didn’t have. And within the first week, I had made a little over $400. I felt very proud about this when I got my first check. It made me forget how tired I was becoming from working every day. It also made me happy because it meant my mom didn’t have to work as hard as she did before. Moreover, within a month of working at the restaurant, I had accumulated over $250 in savings, which I was very proud of. The little savings I had accumulated somehow made me feel more financially secure. Every weekend after work was like a victory parade for me. The moment I handed over half my pay to my mother made me feel so helpful around the house. I could do anything I wanted with the remaining half of the pay. I used quite a fraction of this weekly to buy snacks for my siblings. This made me feel nice and even more useful around the house. After about three months of work, my mom got a promotion at one of her places of work. It meant I no longer needed to work at the restaurant. But I still went to work there anyway. I did it because of the money and how useful it made me feel. I continued working at the restaurant for about five more months before joining college.

Final Thoughts!

First-person essays are essays written from the first-person perspective. There are several first-person perspective essays, including personal narrative essays, scholarship essays, admission essays, memoirs, etc.

In this post, you learned everything crucial about first-person essays. If you need help writing any first-person essay, you should contact us. We’ve got writers ready to write any type of first-person essay for you.

Any of our writers can ensure your first-person essay is excellent, original, error-free, and ready for submission.

Need a Discount to Order?

15% off first order, what you get from us.

Plagiarism-free papers

Our papers are 100% original and unique to pass online plagiarism checkers.

Well-researched academic papers

Even when we say essays for sale, they meet academic writing conventions.

24/7 online support

Hit us up on live chat or Messenger for continuous help with your essays.

Easy communication with writers

Order essays and begin communicating with your writer directly and anonymously.

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

First-Person Point of View: Definition and Examples

4-minute read

- 13th August 2023

The first-person point of view is a grammatical person narrative technique that immerses the reader into the intimate perspective of a single character or individual.

In this literary approach, the story unfolds through the eyes, thoughts, and emotions of the narrator, granting the reader direct access to their inner world. Through the narrator’s use of pronouns such as I and me , readers gain a personal and subjective understanding of the narrator’s experiences, motivations, and conflicts. For example:

If the author uses the third-person point of view , the sentence would read like this:

Why Write From the First-Person Point of View?

This point of view often creates a strong sense of immediacy, enabling readers to form a deep connection with the narrator while limiting the reader’s knowledge to what this character or narrator knows. It’s a dynamic viewpoint that allows the rich exploration of a character’s or narrator’s growth and provides the opportunity to delve into their personal struggles.

First-person narration shouldn’t be used or should be considered carefully in some situations. Familiarize yourself with genre style and tone before making this decision.

Using the First-Person Point of View in Fiction

The first-person point of view is a powerful tool in fiction because it can create an intimate and engaging connection between the reader and the narrator. It is particularly effective for the following purposes.

Developing a Character’s Voice and Personality

First-person narration facilitates a deep exploration of a character’s or narrator’s unique voice, thoughts, and personality. It enables readers to experience the story through the lens of the narrator or a specific character, giving the reader direct insight into their emotions, motivations, and growth.

Portraying Subjective Experiences

When the story relies heavily on the narrator’s or a character’s subjective experience, emotions, and perceptions, the first-person point of view can help the reader connect on a personal level. This bond is especially beneficial in stories that explore complex internal conflicts and psychological themes.

Enhancing Reader Empathy

First-person narratives can foster empathy by enabling readers to see the world through the eyes of the narrator. This perspective can lead to a more emotional and immersive reading experience, allowing readers to relate to and invest in the narrator’s or a character’s journey.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

Conveying Unreliable Narrators

First-person narration is excellent for stories featuring unreliable narrators . Readers can uncover discrepancies between what the narrator says and what they actually do, revealing layers of intrigue and mystery.

Delivering Engaging Storytelling

When the narrative requires a strong and engaging storyteller, the first-person point of view can make the story feel more like a conversation or confession, drawing the reader in.

It’s also important to note that using the first-person point of view comes with limitations. The narrator’s perspective is confined to what they personally experience, possibly limiting the scope of the story’s atmosphere and the portrayal of events that occur outside the narrator’s awareness. Consider how authors of classic novels have utilized point of view in their writing.

The First-Person Point of View in Research Essays

Generally, it’s preferable to avoid the first person in academic and formal writing. Research papers are expected to maintain an objective, unbiased, and impartial tone, focusing on presenting information, data, and analyses clearly. The use of I or we may introduce subjectivity and personal opinions, which can undermine the credibility and professionalism of the research.

Instead, the third-person point of view is preferred because it allows a more neutral and detached presentation of the material. Follow the guidelines and style requirements of the specific field or publication you’re writing for: some disciplines may have different conventions regarding the use of first-person language.

The first person can lend itself to some types of research description when the researcher is discussing why they made a particular decision in their approach or how and why they interpret their findings.

But be aware that when writers attempt to write without reverting to the first person, they often overuse the passive voice . In nonfiction or academic writing, staying in the first person may sometimes be better than using the passive voice.

Ultimately, the decision to use the first person in fiction or nonfiction depends on the specific goals of the author. Fiction authors should consider how this narrative choice aligns with the story’s themes, characters, and intended emotional impact. Research writers should carefully consider whether the use of the first person is necessary to convey their findings and decisions or whether that information could be described as or more effectively without it.

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Table of Contents

Collaboration, information literacy, writing process, the first person.

- CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 by Frederik DeBoer

The first person—“I,” “me,” “my,” etc.—can be a useful and stylish choice in academic writing, but inexperienced writers need to take care when using it.

There are some genres and assignments for which the first person is natural. For example, personal narratives require frequent use of the first person (see, for example, “ Employing Narrative in an Essay ). Profiles, or brief and entertaining looks at prominent people and events, frequently employ the first person. Reviews, such as for movies or restaurants, often utilize the first person as well. Any writing genre that involves the writer’s taste, recollections, or feelings can potentially utilize the first person.

But what about more formal academic essays? In this case, you may have heard from instructors and teachers that the first person is never appropriate. The reality is a little more complicated. The first person can be a natural fit for expository, critical, and researched writing, and can help develop style and voice in what can often be dry or impersonal genres. But you need to take care when using the personal voice, and watch out for a few traps.

First, as always, listen to your teacher, instructor, or professor. Follow the guidelines given to you; if you’re not supposed to use the first person in a particular class or assignment, don’t! Also, recognize that, while it is not universally valid or helpful, the common advice to avoid the first person in academic writing comes from legitimate concerns about its misuse. Many instructors advise their students in this way due to experience with students misusing the first person.

Why do teachers often counsel against using the first person in an academic paper? Used too frequently or without care, it can make a writer seem self-centered, even self-obsessed. A paper filled with “I,” “me,” and “mine” can be distracting to a reader, as it creates the impression that the writer is more interested in him- or herself than the subject matter. Additionally, the first person is often a more casual mode, and if used carelessly, it can make a writer seem insufficiently serious for an academic project. Particularly troublesome can be constructions like “I think” or “in my opinion;” overused, they can make a writer appear unsure or noncommittal. On issues of personal taste and opinion, statements like “I believe” are usually inferred, and thus repeatedly stating that a statement is only your opinion is redundant. (Of course, if a statement is someone else’s opinion, it must be responsibly cited.)

Given those issues, why is the first person still sometimes an effective strategy? For one, using the first person in an academic essay reminds the audience (and the author) of a simple fact: that someone is writing the essay, a particular person in a particular context. A writer is in a position of power; he or she is the master of the text. It’s easy, given that mastery, for writers and readers alike to forget that the writer is composing from a limited and contingent perspective. By using the first person, writers remind audiences and themselves that all writing, no matter how well supported by facts and evidence, comes from a necessarily subjective point of view. Used properly, this kind of reminder can make a writer appear more thoughtful and modest, and in doing so become more credible and persuasive.

The first person is also well-suited to the development of style and personal voice. The personal voice is, well, personal; to use the first person effectively is to invite readers into the individual world of the writer. This can make a long essay seem shorter, an essay about a dry subject seem more engaging, and a complicated argument seem less intimidating. The first person is also a great way to introduce variety into a paper. Academic papers, particularly longer ones, can often become monotonous. After all, detailed analysis of a long piece of literature or a large amount of data requires many lines of text. If such an analysis is not effectively varied in method or tone, a reader can find the text uninteresting or discouraging. The first person can help dilute that monotony, precisely because its use is rare in academic writing.

The key to all of this, of course, is using the first person well and judiciously. Any stylistic device, no matter its potential, can be misused. The first person is no exception. So how to use the first person well in an academic essay?

- First, by paying attention to the building blocks of effective writing. Good writing requires consistency in reference. Don’t mix between first, second, and third person. Although referring to yourself in the third person in an academic essay is rare (I hope!), sometimes references to “the author” or “this writer” can pop up and cause confusion. “This author feels it is to my advantage…” is a good example of mixing third person references (this author) with first person reference (my advantage). If you must use the third person, keep it consistent throughout your essay: “This author feels it is to his advantage…” Be aware, however, that such references can often sound pretentious or inflated. In most cases it will be better to keep to the simpler first person voice: “I feel it is to my advantage.”

- Similarly, be cautious about mixing the second and first person. Second person reference (“You feel,” “you find,” “it strikes you,”) can be a useful tool, particularly when trying to build a confessional or conversational tone. But as with the third person, mixing second and first person is an easy trap to fall into, and confuses your prose: “I often feel as if you have no choice….” While such constructions can potentially be grammatically correct, they are unnecessarily confusing. When in doubt, use only one form of reference for yourself or your audience, and be clear in distinguishing them. Again, use caution: as the second person essentially speaks for your readers, it can seem presumptuous. In most cases, the first person is a better choice.

- Finally, consistency is important when employing either the singular or plural first person (“we,” “us,” “our”). The first person plural is often employed in literary analysis: “we have to balance Gatsby’s story with Nick’s skepticism.” Here, I would recommend maintaining consistency not just within a sentence or paragraph, but within the entire text. Shifting from speaking about what I feel or think to what we feel or think invites the question of what, exactly, has changed. If a writer has made observations of the type “we know,” and then later of the type “I believe,” it suggests that the writer has lost some perspective or authority.

Once you’ve assured that you’re using the first person in a consistent, grammatically correct fashion, your most important tools are restraint and caution. As I indicated above, part of the power of the first person in an academic essay is that it is a rarely used alternative to the typical third person mode. This power only persists if you use the first person in moderation. Constantly peppering your academic essays with the first person dilutes its ability to provoke a reader. You should use the first person rarely enough to ensure that, when you do, the reader notices; it should immediately contrast with the convention you’ve built in your essay.

Given this need for restraint, student writers would do best to use the first person only when they have a deliberate purpose for using it. Is there something different about the particular passage, paragraph, or moment into which you want to introduce the first person? Do you want to call attention to a particular issue or idea in your paper, particularly if you feel less certain about that idea, or more personally connected to it? Finally, have you established a consistent use of the third person, so that using the first person here represents a meaningful change? After a long, formal argument, the first person can feel like an invitation for the reader to get a little closer.

Think of the first person as a powerful spice. Just enough can make a bland but serviceable dish memorable and tasty. Too much can render it inedible. Use the first person carefully, when you have a good reason to do so, and it can enliven your academic papers.

Use the First Person

Using first person in an academic essay: when is it okay.

Brevity – Say More with Less

Clarity (in Speech and Writing)

Coherence – How to Achieve Coherence in Writing

Flow – How to Create Flow in Writing

Inclusivity – Inclusive Language

The Elements of Style – The DNA of Powerful Writing

Suggested Edits

- Please select the purpose of your message. * - Corrections, Typos, or Edits Technical Support/Problems using the site Advertising with Writing Commons Copyright Issues I am contacting you about something else

- Your full name

- Your email address *

- Page URL needing edits *

- Comments This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

Featured Articles

Academic Writing – How to Write for the Academic Community

Professional Writing – How to Write for the Professional World

Authority – How to Establish Credibility in Speech & Writing

Improve your writing in one of the largest and most successful writing groups online

Join our writing community!

Writing First Person Point of View: Definition & Examples

by Alex Cabal

The first-person point of view (or PoV) tells a story directly from the narrator’s perspective, and using it can help the reader connect with your work. This is because first-person point of view uses language that mirrors how individual people naturally speak. It’s a way for a writer to share thoughts, ideas, or to tell a story in a close and relatable way, and brings the reader directly into the perspective of the narrator.

What is first-person PoV?

First-person perspective is when the protagonist tells a story from their own point of view using the pronoun “I.” This storytelling technique focuses on the internal thoughts and feelings of the “I” narrator, offering a deep immersion into the protagonist’s perspective. This creates the sensation that the character is speaking directly to the reader.

In conversation, first-person language would sound like “I went to the store earlier,” or “I saw a great movie on TV last night!” Internal thoughts may sound like “I wish he would just say how he feels,” or “Why can’t I be brave and just do it!”

Writing a first-person narrator provides the opportunity for both the writer and the reader to directly step into the “shoes” of the protagonist—if done well, it can deeply connect the reader to the work and allow them to experience the story directly from the perspective of the first-person narrator.

First-person narration can also be a great tool to use in non-fiction work, such as autobiographical and memoir pieces where the author is telling a true first-person account of their lived experience. For example, “I was there in Berkeley in 1969, and bore witness to rioting youth and the roots of the revolution.”

Writing in first-person narration brings the reader intimately—and at times empathetically—into the story, as they experience the world of the story directly from the character’s mind.

A writer can also use multiple first-person perspectives told through different characters in a story. Doing this can immerse the reader in each person’s unique perspective of what’s occurring in the plot.

A writer can also use first-person point of view to tell a story in both the past and present tense to offer direct opinions on the narrator’s personal experience through both reflection on the past and action in the present.

First-person point of view words and language

The words most often used in the first-person narrative include both singular and plural first-person pronouns.

Singular first-person point of view words list:

Plural first-person point of view words list:.

The language used follows the perspective of the narrator: “I did this,” or “he held my hand,” or “we went to the store together.”

What’s the difference between first, second, and third-person point of view?

You’ll often hear writers talking about first-person point of view, second-person point of view, and third-person point of view. But what’s the difference?

First-person PoV , as we looked at above, tells a story from just one character’s perspective (or, from one character at one time) using the pronoun “I.”

Second-person PoV is similar to first-person in that it follows just one character. In this case, however, second-person point of view uses the pronoun “you.” This perspective treats the reader as if they were part of the story.

Second-person point of view is challenging, and is generally best suited to the short story form. However, some authors have taken on the second-person PoV in novels, such as Italo Calvino’s If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler . You might also recognize second-person narration from “Choose Your Own Adventure” books.

Third-person PoV is a perspective in which the reader is kept at a distance from the story. These stories use the third-person pronouns “He,” “She,” and “They.” Reading about a third-person narrator is like watching a film; you can see everything that’s happening, but you’re not part of it.

There are two common types of third-person perspective: third-person limited narration and the third-person omniscient narrator. The limited third-person narrative voice uses the he, she, they pronouns but follows only one character at a time.

The third-person omniscient point of view can see into all the characters, all the time. This type of third-person narration allows the reader to know more than any one character knows at any given time. An omniscient narrator mimics the experience of watching a stage play; the reader can see everything happening on the stage, even if the characters can’t.

Third-person point of view is popular and timeless because it’s the classic storytelling voice. It’s what we hear when someone says, “ Once upon a time… ” You’ll find that the majority of classic literary fiction, and much of contemporary fiction, uses this narrative point of view.

To learn more about using each of these point of view styles in your writing, why not visit the lesson series in our writing academy ?

What’s the difference between first-person and fourth-person point of view?

Writers often confuse first-person point of view and fourth-person point of view because they both tell a story from the perspective of the protagonist. The difference is that first-person PoV uses a singular voice, while fourth-person PoV uses a collective voice.

This isn’t quite the same thing as first-person plural. When plural first-person pronouns are used in first-person PoV—that would be words like “we” and “us”—it’s describing a shared experience between the narrator and another person.

For example, “We went to the movies, and Jim bought me some popcorn” is told in first person, even though it uses “we” to describe two people.

Fourth-person point of view treats a group of beings as one narrator. This is an experimental narrative form that’s become more popular in recent years and is effective in communicating large social issues. Your fourth-person narrator might be a group of suppressed office workers, a generation of young people facing a broken housing market, or a multilayered collective consciousness from outer space.

If you want to experiment with writing a fourth-person story, you’ll want to take a look at our detailed lesson here .

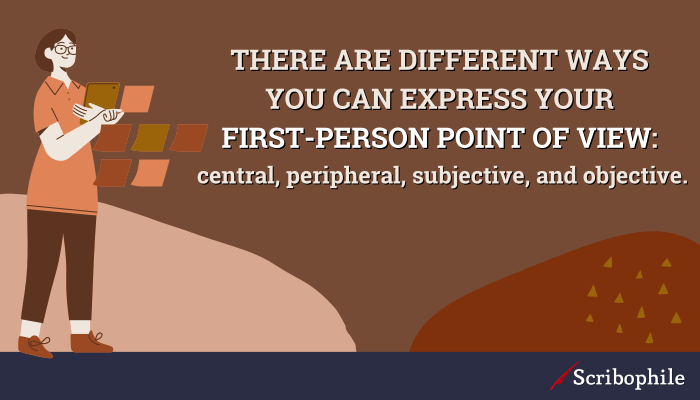

Types of first-person point of view

When we talk about first-person point of view, there are several types that we might be referring to. Let’s take a look at the different ways you might use the first-person voice in your story.

First-person central

In first-person central, the story is told from the protagonist’s point of view—the main character who is driving the plot. Using a first-person central PoV immerses the reader directly into the main character’s thoughts, feelings, and actions, as if the reader is the central character.

A classic example of first-person central PoV is Catcher in the Rye . Holden Caulfield, the novel’s protagonist, tells the story directly from his point of view. This provides the author the opportunity to address complex social issues from the perspective of a teenager.

First-person peripheral

In first person peripheral, the narrator tells the story as a witness, but is not the main character. Using the first-person peripheral perspective in storytelling allows the writer to keep the focus on the protagonist, yet keep the reader removed from the thoughts and feelings of the main character.

This type of distance puts the reader in the shoes of the narrator while the narrator relates their thoughts, opinions, and perception of the main character.

One example of first-person peripheral point of view is the Sherlock Holmes canon. In these stories, the narrator is John Watson, who tells the story from the perspective of witnessing his best friend solve mysteries. Writing from a peripheral perspective allowed the author to create intrigue, mystery, and suspense.

First-person subjective

In addition to the central and peripheral narrative point of view, your first-person PoV character will also use the subjective or objective voice.

Most first-person protagonists in literature are subjective. This means they tell the story through the lens of their own thoughts, feelings, cultural biases, and ambitions. This narrative choice adds richness to your story world, but also narrows the reader’s understanding to the way your protagonist sees the world around them.

First-person objective

The objective first-person point of view is less common, but can be very effective—particularly in genres like speculative fiction and horror. In this narrative style, the PoV character doesn’t interject their own preconceptions and ideas; it’s simply the narrator telling the reader what happens.

This makes the story sound a bit like a witness statement, and allows the impact of the events to come through the actions of the characters rather than through their emotions.

What is first-person limited and first-person omniscient point of view?

Choosing to write from a first-person limited or first-person omniscient point of view allows the author to decide what insight is shared with the reader, and how much the narrator knows about what’s occurring within the plot.

First-person limited point of view

First-person perspective typically takes on a limited perspective—the story is told directly, and only, from the narrator’s internal thoughts, feelings, and personal experiences. This means the entire story has a limited view of how the character sees and experiences the world.

An example of first-person limited point of view is the novel To Kill a Mockingbird . The story is told through the main character, a child named Scout, and the reader is only offered limited information from a child’s point of view. Writing from first-person limited offered Harper Lee the opportunity to approach complex topics from the eyes of a child.

First-person omniscient point of view

First-person omniscient is a more uncommon use of first person, as omniscient narration takes on a god-like understanding of what’s happening within the plot. Sometimes, this type of narration can be unnerving for a reader and cause them to disengage from a story. However, that doesn’t mean it can’t be done successfully.

An example of first-person omniscient narration is Saving Fish From Drowning , by Amy Tan. The story is written from the perspective of a ghost, Bibi Chen, a central yet peripheral character.

Having the story recounted by the spirit of the narrator allows the reader a vast amount of insight into all the characters’ thoughts and feelings without breaking the cadence of the story—at times offering comedic relief for experiences that might be deeply uncomfortable for the reader to experience first-hand.

Why do authors love first-person PoV?

First-person narrators allow the reader to get rooted in their character’s head and thereby achieve a tighter emotional connection with the reader. To make the connection even stronger, the character lets the audience in on secrets or insights that no one else knows.

First-person point of view is often used in autobiography and memoir writing, where the story must be told from one central perspective. Using first-person narrative in memoirs and autobiographies makes the story feel more genuine, authentic, and authoritative because the story is told directly as a first-hand account from the person who experienced the events themselves.

First-person novels are also popular with fiction writers, because they offer deep insight into the theme, story, and plot directly from the “I” narrator. This helps the writer connect with their demographics, their age, sex or gender, social status, and so forth.

First-person point of view in fiction writing can instill a sense of a narrator’s authority or credibility in the story, yet also offers the writer the opportunity to play with having the story told from an unreliable narrator or an unusual perspective.

Consider the earlier example of To Kill a Mockingbird and the way Lee used a child’s perspective to illuminate a theme of justice and complex social issues—a theme that might otherwise alienate a reader from the story, rather than create a sense of empathy.

While it may seem that writing in the first-person voice may be limiting in storytelling power—as the story focuses solely on the internal thoughts and feelings of the narrator—the role of the narrator can assist in weaving complexity and intricacy into the story.

Advantages of first-person point of view

First-person point of view can create a compelling, emotional story—sometimes even stronger than a story written in third-person PoV—because the character and reader are connected through intimate, one-on-one communication.

Advantages of first-person narrative include:

Creating a sense of mystery and intrigue; the first-person PoV shields the reader from certain information until a major moment unfolds in the plot, when both reader and narrator learn something new.

Lending a story credibility by building rapport with the reader, and thus making the narrator seem more reliable. This sense of connection can make the narrator and reader feel as if they’re sharing a private conversation.

Positioning the narrator as an unreliable narrator part way through the story can be used to subvert the reader’s expectations.

First-person PoV prose is highly character driven, leaning into who the character is as a person, their motivations, world views, the strengths and weaknesses of their personality. This perspective can evoke a deep sense of empathy and compassion that connects the reader to the story.

Disadvantages of first-person point of view

While first-person PoV can create an empathetic connection between the character and the reader, the reader is also limited to that one perspective—which can become very insular.

Disadvantages of first-person point of view include:

Given that first-person PoV is generally used as a limited perspective, it tends to the personal biases of the narrator. While bias from the narrator’s perspective may not fully be negative, it can turn away readers that don’t or can’t align with the inclinations, preferences, and perspectives of the narrator.

First-person PoV limits a story to the singular perspective of the narrator, which can make additional subplots more challenging since the reader can’t see into the mind of alternative characters.

Using a first-person perspective can also make it difficult for the narrator to describe themselves and their physical characteristics to give further context and details of the story.

Tips for writing in first-person PoV

The following tips for writing in the first-person point of view will lay out some best practices and give you some insight into how to avoid common mistakes.

1. Quickly establish who the narrator is

Open your story by establishing a strong character voice that demonstrates who this person is and why their voice is unique. Consider this example of an introductory paragraph to a story:

I’ll never understand why hospitals don’t use better lighting. No one wants ugly blue light shining into their eyes while as they look for the soft light everyone says calls to you from the end of the tunnel. I don’t see a tunnel, all I see is the burning glare of this light, reflecting at me from all of these too shiny metallic surfaces.

In this example, the character’s tone is immediately established as critical, unhappy, and bitter. Additionally, the reader is given clear details about the character—that they’re in a hospital, possibly dying, and that the story is told directly from their perspective.

2. Stay in character

Think about the demographics of your character, their background, culture, education, and influences, and remain true to who the character is.

This is especially true when it comes to writing dialogue, and if you’re using any kind of vernacular. For example, if a story is told from the perspective of an exhausted waitress who grew up in a big city on the east coast, it would be unlikely that she would approach a table and say:

“Hi y’all, you feelin’ hungry? What looks good today?”

She would probably use terse and maybe even sharp language that gets straight to the point, and wouldn’t use southern vernacular or phrases such as “y’all” or “feelin’.” Instead, she might say: “Did you look at the menu? Are you ready to order?” Make sure your PoV character uses their own voice.

3. Follow your narrator

Don’t lose scope of what the narrator knows within the story—not only pertaining to the thoughts and emotions of other characters, but also to what’s occurring in the plot and world around them.

For example, if your main character is sitting in a jail cell waiting to hear back from their lawyer about the verdict of the trial, there’s no way for them to know the events that are unfolding in the courtroom until a scene takes place where the character is told what happened.

4. Avoid head hopping

Avoid head hopping and don’t change characters’ perspectives within a single paragraph or chapter. If you choose to use more than one first-person narrator within a story, ensure that the transitions between the other characters and perspectives are easily identifiable within the text.

For example, a story about a relationship between two people could be told from each person’s first-person PoV, but the author would need to make it clear which character is telling each part of the story. To avoid slipping into another character’s head, consider this example:

She looked at me, thinking about how I had eaten the last piece of her chocolate birthday cake.

The narrator can’t know what “she” is thinking. Instead, consider the following example that strictly stays in the thoughts and perspective of the narrator:

She looked at the empty plate, and then at me. I felt the accusation in her glare. How dare she think I would eat the last of her chocolate birthday cake?

You can find out more about this cardinal sin of fiction writing through our lesson on head hopping here.

5. Limit the use of “I” and repetitive language

Overuse of “I” language within a story can be monotonous and repetitive for a reader, especially if “I” is used heavily at the beginning of sentences. To avoid the overuse and repetition of “I,” consider the following example:

“I love that particular flavor of ice cream…” vs. “That particular flavor of ice cream is a favorite of mine.”

Or, “I know this room…” could also be written in the passive voice as: “This room feels familiar.”

Playing with both active and passive voice and seeking creative ways to share information about a narrator can keep the text from becoming overwhelmingly repetitive with the use of “I.”

In addition, when writing dialogue in the first person, avoid repetition of “he said” and “she said.” In these instances using character names and descriptive language can assist in alleviating overly repetitive text.

For example:

“Angela, I want out of this wedding.” “You can’t,” she sighed. “My mother already bought the dress and my father put a downpayment on the venue.” “Do you think I care about a dress or a downpayment? I want out.” A single tear rolled down her cheek. “Fine. Leave, and don’t ever come back.” “I won’t.”

To dive deeper, you can check out our lesson on active and passive voice , and our detailed article on mastering dialogue tags !

First-person PoV examples from literature

One of the best ways to learn how to write in the first person is to read books and novels that have been written in first-person point of view. Here are a few novels written in this narrative style:

The Hunger Games , by Suzanne Collins.

The Fault in Our Stars , by John Green.

Elmet , by Fiona Mozley.

Into the Jungle , by Erica Ferencik.

The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn , by Mark Twain.

Moby-Dick , by Herman Melville.

Never Let Me Go , by Kazuo Ishiguro.

Goodbye, Vitamin , by Rachel Khong.

The Time Traveler’s Wife , By Audrey Niffenegger.

First-person point of view opens new worlds

First-person point of view has a lot to offer the writer, no matter what genre you’re writing in. Unlike third-person point of view, which puts some distance between the reader and the story, using first-person pronouns effectively brings the reader right into the heart of your story.

Get feedback on your writing today!

Scribophile is a community of hundreds of thousands of writers from all over the world. Meet beta readers, get feedback on your writing, and become a better writer!

Join now for free

Related articles

Third Person Omniscient Point of View: The All-Knowing Narrator

What is 4th Person Point of View?

Memoir vs. Autobiography: What Are the Differences?

How to Write a Sex Scene

How to Write in the Second Person Point of View + Examples

How to Write in Third Person Multiple Point of View + Examples

How to write a first person essay

- November 18, 2023

A first person essay is a type of academic essay written in the first person point of view that presents a significant lesson learned from a writer’s personal experience.

The aim of a first person essay is to establish a bond with the reader. You encourage the reader to accompany you on your personal journey when writing this type of essay .

Step 1: First person essay example

Before we go further into the steps, analyze the following first person essay example This will give you an overall idea of what a first person essay is.

First person essay example

When I think of my past life, one of the memories I remember the most vividly is my first day at school. Hook: Engaging first sentence that helps the reader grasp the importance of the event. I have always been a student that loved school and studying; I am what you might consider a nerd. Therefore, I don’t think it’s necessary for me to say how excited I was to start school. Personal information: Information that connects the reader with the writer.

In the weeks leading up to the first school day, I remember checking my stationary my parents had bought me for school every day and admiring them, thinking how excited I was to finally start using them. Opening sentence: Vivid explanation of the past events, creating a more appealing story. I had already learned to read and write before starting elementary school, and I could not wait to see the look on my teacher’s face when I told them, “I already know this stuff!”. Yes, I was an annoying kid. Insights: Insight into the writer’s personality, which creates a more sincere tone. You can ask my childhood friends if you would like to hear someone else’s thoughts on this; I am sure they will tell you the same thing. Concluding sentence: Casual and humorous tone that eases the reader.

You probably expect a happy first day of school story from me right now. Emotional connection: Addressing the reader, therefore strengthening the emotional connection. The truth is far from that. As much as I was a nerd, I was a mamma’s kid. Insights: Further insight into the writer’s personality. So, when my parents dropped me off at school, I started crying my eyes out. Event: Vivid description of the event. I did not want them to leave, but I also wanted to begin my first school day. So, my mother set eyes on a blonde girl that she thought looked like a good kid and made me sit next to her. After starting to chat with my new friend, I slowly eased off and was ready to put on a show. Needless to say, that blonde girl became one of my best friends in elementary school. Feelings: Description of feelings felt by the writer. This helps strengthen the bond between the writer and the reader. Even though it did not go quite according to my plans, I still cherish the memory of my first day at school. Concluding sentence: Concluding sentence of your paragraph which should be memorable and descriptive.

The rest of the school year was much more eventful because, being a crybaby, I started crying even at the slightest of inconvenience. Emotional connection: More insight into the writer’s personality. Adding these details creates an emotional bond with the reader. Naturally, this created a problem for my teacher and classmates, in so much that the deputy headteacher was telling kids to keep quiet, not because it disrupted the class, but because it made me cry. Emphasizing memories: Recounting of more memories in a casual tone. Thinking back to my first school day and generally, my elementary school experience always makes me happy. Therefore, I always have so much fun talking about my school experiences. Final sentence: Your finishing sentences, make sure to make it memorable for your reader.

Step 2: Structure of a first person essay

When it comes to first person essays, both structured academic writing or casual personal narratives can be used.

But remember that the style of first person essays is typically conversational . You need to combine a mixture of personal anecdotes, an emotional connection, and a clear point of view. So personal pronouns are highly common in first person essays.

First person pronouns

First person pronouns example.

Pronouns such as “ I ,” “ me ,” and “ we ” First person pronouns must be used when writing first person essays. This contrasts with the third person point of view, which uses third person pronouns such as “ he ,” “ she ,” and “ they ”. Third person pronouns

Second person pronouns

Second-person pronouns example.

First person essays also contrast with the second-person point of view, which uses second-person pronouns such as “ you ,” and “ yours ”. Second-person pronouns

Now that we have learned the essentials of first person essays, we can continue with the steps to write an excellent one.

Step 3: Choosing a first person essay topic

Almost any topic can be written in a first person essay. But this should not scare you, as we have some tactics for you to easily choose your topic .

- It doesn’t matter what you write as long as it’s something you’re enthusiastic about.

- Ask yourself this question: “What have I experienced in the past that has had an emotional appeal on me?”

- Choose a topic that is amusing, compelling or moving.

- If you’re having trouble choosing what to talk about, think about what makes you happy or sad.

First person essay topic examples

- Your first day at school

- Your new life in a new city

- The funniest day of your life

- A sad event you have gone through

- A memory from your childhood

For this guide, we’ve chosen the topic of “ your first day at school .” Above, you’ll see the example essay . When you’ve worked out what you want to say, move on to the next step: figure out your tone.

Step 4: Define your tone

Before starting your first draft, think about your essay’s tone and language (see UK and US English ).

Your writing style will need to change depending on the purpose of your essay. For instance, i f you’re writing an argumentative or persuasive essay, you may want to use a calculated and rational first person viewpoint .

This will persuade the reader to agree with your key argument. But when you’re writing a reflective essay , you may want to use satire to keep the reader entertained.

So for first person essays, ask yourself these questions to see if your tone is appropriate:

- Is my tone clear?

- Is my writing intimate and appealing?

- Can my first person storytelling connect with the reader?

If your answers to these questions are “ yes ,” you are probably doing a good job.

Step 5: Create an outline

It’s time to make a brief outline now that you’ve selected your topic and decided on the right tone. The outline will help you get your thoughts organized. It will also help you with the order of your headings in the writing process .

Your first person essay should follow the traditional introduction , body paragraphs , and conclusion essay structure, unless stated otherwise.

Example of a first person essay outline

- Personal information

- Concluding sentence

- Final sentence

Ask yourself these questions while creating your outline:

- What are your story’s or argument’s key points?

- What are the places, people, and events that are important for my essay?

- What do you want people to understand from your first person essay?

- What feelings do you want to inspire or trigger?

- What do you want your readers to think about you?

Step 6: Write your first draft

Now, let’s get to writing. The first draft of your essay is an important step toward creating a well-thought-out and concentrated academic essay .

First person essay introduction first draft example

Introduction (Hook, Personal information) I was always attracted by the stars in the night sky as a youngster. They appeared to be tiny pinpricks of light, far away and enigmatic. My passion in astronomy only grew as I grew older, and I began to spend countless hours studying the stars and planets. I didn't realize the enormous power of a telescope until I was in college. I could see aspects of the world that I had never dreamed conceivable with such a little tool. I've been studying the stars as an amateur astronomer for almost a decade. I've always been captivated by the universe's beauty and complexity, and I feel is no greater thrill than learning something new about our surroundings.

Things to consider

- Don’t be too harsh on your first draft. You’ll have plenty of time to revise it later.

- All you have to do now is identify your story's basic elements: characters, locations, and incidents.

- It’s fine to stop, gather your thoughts, and remind yourself of your main idea when writing your first draft.

- If you can, give yourself a few days to rest after writing the draft, then come back and revise it.

More on first draft

Step 7: revise your draft and finish writing, first person essay introduction final draft example.

Introduction (Hook, Personal information) I was always attracted by the stars The stars always attracted me in the night sky as a youngster. They appeared to be tiny pinpricks of light, far away and enigmatic. My passion in astronomy only for astronomy grew as I grew older, and I began to spend spent countless hours studying the stars and planets. I didn't realize only realized the enormous power of a telescope until once I was in college. I could see aspects of the world that I had never dreamed of conceivable with such a little tool. I've been studying studied the stars as an amateur astronomer for almost a decade. I've always been captivated by the universe's beauty and complexity, and I feel and there is no greater incredible thrill than learning something new about our surroundings.

Important things to consider while revising

- Don’t just tell the reader what’s going on; use vivid common words, phrasal words , transition words , and transition sentences to describe the situation and depict the storyline.

- Avoid excessive emotions. It’s perfectly appropriate to convey happiness, frustration, or sadness, but you must strike a balance.

- Proofread the essay for common mistakes , spelling and grammar mistakes ( active and passive etc.), capitalization rules , punctuation, and repetitions.

- Examine the writing and see if it’s straightforward and to-the-point and whether you’re sharing your ideas in an understandable way.

- Is there consistency in the essay, both structurally and contextually?

- Are there any passive voice sentences that I can rewrite in active voice?

- Is there enough sensory information in my essay to touch the reader and make them feel like they’re a part of my experience?

Key takeaways

- A first-person essay is a type of essay that is written from the perspective of the author, using "I" statements and personal experiences.

- To write a first-person essay, you must be willing to share personal details and experiences with your reader.

- Begin your essay with a clear introduction that provides context for your topic and establishes your voice as the author.

- Use personal anecdotes, sensory details, and other techniques to bring your experiences to life and engage the reader.

- End your essay with a conclusion that reflects on your experiences and provides a final thought or message for the reader.

Recently on Tamara Blog

How to write a discussion essay (with steps & examples), writing a great poetry essay (steps & examples), how to write a process essay (steps & examples), writing a common app essay (steps & examples), how to write a synthesis essay (steps & examples), how to write a horror story.

Writing Help

Essay writing: first-person and third-person points of view, introduction.

People approach essay writing in so many different ways. Some spend a long time worrying about how to set about writing an informative piece, which will educate, or even entertain, the readers. But it is not just the content that's the issue; it is also the way the content is - or ought to be - written. More may have asked the question: what should I use, the first-person point of view (POV) or the third-person?

Choosing between the two has confused more than a few essay-writing people. Sure, it can be easy to fill the piece up with healthy chunks of information and content, but it takes a deeper understanding of both points of view to be able to avoid slipping in and out one or the other - or at least realize it when it happens. Sure, a Jekyll and Hyde way of writing may be clever, but it can be very confusing in non-fiction forms, like the essay.

Why is all this important?

Continually swapping from the first-person to the third-person POV may leave the reader confused. Who exactly is talking here? Why does one part of the essay sound so detached and unaffected, while the next suddenly appears to be intimate and personal?

Indeed, making the mistake of using both points of view - without realizing it - leaves readers with the impression of the essay being haphazardly written.

Using first-person: advantages and disadvantages

The use of the first-person narration in an essay means that the author is writing exclusively from his or her point of view - no one else's. The story or the information will thus be told from the perspective of "I," and "We," with words like "me," "us," "my," "mine," "our," and "ours" often found throughout the essay.

Example: "I first heard about this coastal island two years ago, when the newspapers reported the worst oil spill in recent history. To me, the story had the impact of a footnote - evidence of my urban snobbishness. Luckily, the mess of that has since been cleaned up; its last ugly ripple has ebbed."

You will see from the above example that the writer, while not exactly talking about himself or herself, uses the first-person point of view to share information about a certain coastal island, and a certain oil spill. The decision to do so enables the essay to have a more personal, subjective, and even intimate tone of voice; it also allows the author to refer to events, experiences, and people while giving (or withholding) information as he or she pleases.

The first-person view also provides an opportunity to convey the viewpoint character or author's personal thoughts, emotions, opinion, feelings, judgments, understandings, and other internal information (or information that only the author possesses) - as in "the story had the impact of a footnote". This then allows readers to be part of the narrator's world and identify with the viewpoint character.

This is why the first-person point of view is a natural choice for memoirs, autobiographical pieces, personal experience essays, and other forms of non-fiction in which the author serves also as a character in the story.

The first-person POV does have certain limitations. First and most obvious is the fact that the author is limited to a single point of view, which can be narrow, restrictive, and awkward. Less careful or inexperienced writers using first-person may also fall to the temptation of making themselves the focal subject - even the sole subject - of the essay, even in cases that demand focus and information on other subjects, characters, or events.

Using third-person: advantages and disadvantages

The third-person point of view, meanwhile, is another flexible narrative device used in essays and other forms of non-fiction wherein the author is not a character within the story, serving only as an unspecified, uninvolved, and unnamed narrator conveying information throughout the essay. In third-person writing, people and characters are referred to as "he," "she," "it," and "they"; "I" and "we" are never used (unless, of course, in a direct quote).

Example: "Local residents of the coastal island province suffered an ecological disaster in 2006, in the form of an oil spill that was reported by national newspapers to be worst in the country's history. Cleaning up took two years, after which they were finally able to go back to advertising their island's beach sands as 'pure' and its soil, 'fertile.'"

Obviously, the use of the third-person point of view here makes the essay sound more factual - and not just a personal collection of the author's own ideas, opinions, and thoughts. It also lends the piece a more professional and less casual tone. Moreover, writing in third-person can help establish the greatest possible distance between reader and author - and the kind of distance necessary to present the essay's rhetorical situations.

The essay being non-fiction, it is important to keep in mind that the primary purpose of the form is to convey information about a particular subject to the reader. The reader has the right to believe that the essay is factually correct, or is at least given context by factual events, people, and places.

The third-person point of view is more common in reports, research papers, critiques, biography, history, and traditional journalistic essays. This again relates to the fact that the author can, with the third-person POV, create a formal distance, a kind of objectivity, appropriate in putting up arguments or presenting a case.

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Scholarly Voice: First-Person Point of View

First-person point of view.

Since 2007, Walden academic leadership has endorsed the APA manual guidance on appropriate use of the first-person singular pronoun "I," allowing the use of this pronoun in all Walden academic writing except doctoral capstone abstracts, which should not contain first person pronouns.

In addition to the pointers below, APA 7, Section 4.16 provides information on the appropriate use of first person in scholarly writing.

Inappropriate Uses: I feel that eating white bread causes cancer. The author feels that eating white bread causes cancer. I found several sources (Marks, 2011; Isaac, 2006; Stuart, in press) that showed a link between white bread consumption and cancer. Appropriate Use: I surveyed 2,900 adults who consumed white bread regularly. In this chapter, I present a literature review on research about how seasonal light changes affect depression.

Confusing Sentence: The researcher found that the authors had been accurate in their study of helium, which the researcher had hypothesized from the beginning of their project. Revision: I found that Johnson et al. (2011) had been accurate in their study of helium, which I had hypothesized since I began my project.

Passive voice: The surveys were distributed and the results were compiled after they were collected. Revision: I distributed the surveys, and then I collected and compiled the results.

Appropriate use of first person we and our : Two other nurses and I worked together to create a qualitative survey to measure patient satisfaction. Upon completion, we presented the results to our supervisor.

Make assumptions about your readers by putting them in a group to which they may not belong by using first person plural pronouns. Inappropriate use of first person "we" and "our":

- We can stop obesity in our society by changing our lifestyles.

- We need to help our patients recover faster.

In the first sentence above, the readers would not necessarily know who "we" are, and using a phrase such as "our society " can immediately exclude readers from outside your social group. In the second sentence, the author assumes that the reader is a nurse or medical professional, which may not be the case, and the sentence expresses the opinion of the author.

To write with more precision and clarity, hallmarks of scholarly writing, revise these sentences without the use of "we" and "our."

- Moderate activity can reduce the risk of obesity (Hu et al., 2003).

- Staff members in the health care industry can help improve the recovery rate for patients (Matthews, 2013).

Pronouns Video

- APA Formatting & Style: Pronouns (video transcript)

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Point of View

- Next Page: Second-Person Point of View

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

First Person Guidelines

Chalkbeat publishes personal essays in a series we call First Person . Our goal is to elevate the voices of students, educators, parents, advocates, and others on the front lines of trying to improve public education.

We’re not looking for traditional opinion pieces. We’re seeking essays centered around the writer’s personal experience or observation. Our pieces are usually around 800 words.

Strong First Person essays have a conversational tone, presenting specific examples from the author’s life and connecting those examples to larger issues.

We’re always looking for pieces that...

Consider a news event’s real-life impact on students, educators, and schools.

- I’m a college access counselor. Here’s how the affirmative action decision could upend the application process.

- After Uvalde, I dread going to school. When will our leaders act?

- When students ask why they haven’t seen cicadas, we need to talk about environmental racism

Provide a unique personal perspective about an issue people are talking about.

- As we embrace the ‘science of reading,’ we can’t leave out older students

- I was hired to write a Black history curriculum. Then I was asked to walk back key concepts.

- I voted for masks in school. I worried for my safety after.

Are vulnerable in acknowledging uncomfortable emotions and experiences, and the lessons that emerged as a result.

- I never thought my child would need a school social worker, but I’m so glad she’s in our lives

- Losing my Spanish feels like losing part of myself ( Leer en español )