Kalyenderia: Childhope’s Advocacy to Address Food Insecurity and Hunger Amid COVID-19

- September 9, 2021

This pandemic has hit each one of us. Our everyday lives have changed, and unfortunately, most of us have experienced difficulty breezing through this pandemic. Even before this pandemic, having food on the table has been one of the struggles of some Filipino families. In fact, a United Nations report reveals that even before COVID-19, 59 million Filipinos had already been experiencing food insecurity . This, along with the unavailability of nutritious food for Filipino families (especially children), have been two of the many persistent problems here in our country.

This is why Childhope Philippines, in staying true to our commitment to create a positive impact in street children’s lives , has launched a feeding program in efforts to combat this ever-persistent challenge in our society.

What is a Feeding Program: What You Need to Know

Before anything else, let us discuss the general and most common term used — feeding program — to get to know more about our initiative. Feeding programs basically involve delivering or providing a meal or snack to beneficiaries, most of the time children, and are often done in a specified time. Most non-government organizations or even institutions hold feeding programs to better address the scarcity of nutritious food available to children. This has been one of the efforts being done by organizations, individuals, and communities alike to address the problem of malnutrition and food insecurity.

Why Hold Feeding Programs

The objectives of feeding program include the following:

- Improve the nutrition of certain individuals, for instance, children;

- Provide effective and sustainable source of nutritional meals to improve the health and welfare of these individuals;

- Reduce and prevent malnutrition or undernutrition;

- Educate about health and nutrition; and

- Combat of food insecurity and hunger.

In line with these, we also spearhead feeding programs to address our goal of promoting the rights and welfare of the children by providing one of their basic needs: adequate and nutritional meals.

Why Feeding Program is Important

Feeding programs are deemed important because these are among the efforts done to address the prominent problem of malnutrition, hunger, and food insecurity here in our country. Also, these programs mostly aim to serve underprivileged individuals, especially children. Thus, feeding programs are important to provide care and basic necessity to those who need them the most.

Benefits of Feeding Programs

So, why do we do this and why do we aspire to keep doing this effort? The Center for International Voluntary Service in Kenya listed the benefits of feeding programs below. Although this was written specifically for school initiatives, the list also applies to those programs in communities.

1. They promote the health and development of children.

Proper nutrition and a healthy lifestyle are two of an individual’s basic needs. Through feeding programs that provide meals with high nutritional value, the beneficiaries in the long run will have become healthy and well-developed individuals.

2. It improves concentration and educational performance in school.

Proper diet and health are linked to better concentration and performance in schools. No one can study or attend classes effectively on an empty stomach. Hence, healthy and nutritional meals will lead to better performance in schools.

3. It provides support to the children’s parents and guardians.

Oftentimes, the beneficiaries of feeding programs are children and young students. Through these programs, we are supporting and easing the burden of their parents and guardians. Most of the time, our beneficiaries belong to the underprivileged sectors of our community.

4. The programs also promote farmers and local vendors.

Feeding programs also help and support the local community that acts as suppliers for these initiatives.

5. It helps the community rise above poverty.

Eventually, our beneficiaries and the communities they belong to would end and alleviate the poverty they are in. Feeding programs empower them and give them proper nutrition to go on with their everyday lives and be more responsible students; eventually helping them aspire to a brighter future.

Ultimately, the benefits of feeding programs go beyond providing nutritious meals to children. It also entails creating an impact on their lives and empowering them to have a better future. These programs are just small guaranteed steps to empower these street children and make them hopeful that even though they are struggling now, their future is still in their hands.

Kalyenderia Mobile Soup Kitchen: Childhope’s Community Feeding Program

We at Childhope Philippines recently launched our newest program, Kalyenderia Mobile Soup Kitchen, with the main goal of sharing nutritious food with less-fortunate beneficiaries, especially street children. It has been hard for the street children to have access to nutritious meals or to even eat regularly, especially now with the added burden of COVID-19. Kalyenderia aims to address and alleviate hunger by providing hot meals and hot soups to street families in Manila.

We also have other initiatives other than Kalyenderia. Our mobile health clinic, or KliniKalye , provides primary preventive medical care, consultations, and treatments to children and youth on the street. KalyEskwela , on the other hand, is our “school on the streets” initiative that provides alternative education sessions for street children. With these initiatives, alongside with our other efforts, we yearn to provide holistic development for the Filipino street children and to eventually give them the better life that they deserve.

How You Can Help Us Improve Street Children’s Lives

The pandemic has greatly struck the poorest of the poor. The children that we see roaming around in the streets not only face the risks of the deadly virus , but also the struggle to have food on the table. But we can be the hope of these children in poverty. Therefore, we encourage everyone to create meaningful impact. If you are interested to initiate outreach programs for your community, we have prepared a little guide for you to get you started. Your time, efforts, and resources will help create a positive impact and empower them to have a better future.

Other than donating, we are also on the lookout for selfless volunteers to help us realize and further advance our efforts. If you are the one we are looking for or you are someone who would like to impact and empower these underprivileged children, you may volunteer today .

Subscribe to our Mailing List

©1989-2024 All Rights Reserved.

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

FEEDING PROGRAM REFLECTION

People say when you give sacrifice your time for others, you are also sacrificing a part of your life for them. With that, I agree because that was how I felt joining in the feeding program. It is more than just feeding people, but it is feeding a whole community willing to go this far to praise and thank the Lord. It was a heart-touching experience to become a part of something simple yet significant. Seeing them passing by to get food is more than just charity for me, but it is giving without having to expect anything in return. I would wonder if I were in their shoes, I would wonder the exact same thing as they finally get their fill for the day. The feeling of not only having to feed yourself, but also feeding your children is a real struggle even the rich people experience because you are feeding more than just one mouth. The good Lord spoke to me through these people because it was right there and then that He was teaching us that we could only know the value of life once we have nothing. The staff, including the nuns of the Sta. Catalina Ladies' Dormitory showed the image of what Christ would do when we run to him for help. Whenever we are hungry, lost, even sinned to the very last moment, this teaches us that no food can ever satisfy our hunger because those are only temporary material things. Eventually, they will reach a certain expiry date and is disposed from its healthy purpose, though it is also a harsh reality that some people had no choice but to eat them because of having to live in poverty. With the Center for Campus Ministry (CCM) and my fellow Student Religious Organization (SRO) companions, we got to experience and have a glimpse of what life really is outside of the four walls of the university alone. It is indeed true that life begins when we get out of our comfort zones because even those people who join the feeding program have never even experienced being in one for a very long time. It is said in one of the corporal works of mercy to " feed the hungry " , and with that weekly feeding program, I only needed to sacrifice one half day in a week to participate in something worthwhile and significantly fulfilling. Seeing people smile by giving what you have is the best feeling anyone could ever have. As for me, that is where I also learned how to appreciate life even more because I have the drive to help people more even to those that surround the university. In the end, God will never judge for what we have or what status we obtain, but what He will be looking at is what and how much we give to others who need it more than we do. This feeding program needs to spread out in different organizations and institutions all around so that we, as instruments of God's mercy, can not only bless more people but we will feel all the more blessed as well. Indeed, true love is defined here. It is not only a two-way communication that both the giver and the given are satisfied and fulfilled, but it is when Jesus died on the cross for the sins he never committed. True love is giving without taking, without having to receive anything in return. This experience is something I will definitely go back to over and over again. Being a servant is more than just having to bring the Word of God, but it is also having to be Jesus to others through our deeds and actions.

Related Papers

Servants of Jesus Christ

Don Schwager

At the height of the Renaissance, Niccolò Machiavelli wrote "The Prince", a book regarded by many as the political masterpiece for achieving power, wealth, and success. It remains a bestseller today. Machiavelli wrote that people are motivated by fear and envy, and desire for wealth and power. His worldly perspective contrasts sharply with the gospel paradox: "many that are first will be last, and the last first" (Matthew 19:30), and "blessed are the poor in spirit...the meek...those who mourn...and those who hunger and thirst for righteousness, for they shall be satisfied" (Matthew 5:3-6). Jesus’ message turns the world’s values of power and fulfillment upside down. "Whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be your slave – just as the Son of man did not come to be served but to serve" (Matthew 20:26-28). The New Testament Gospels show us the way to true freedom and success. I doubt that the topic of Christian servanthood will ever make the world’s bestseller list. But if we want to achieve true happiness and fulfillment, Jesus Christ offers us the surest way. The New Testament Scriptures and the testimony of the early church fathers bear witness to the transforming power of Christ’s love and his way of servanthood. The heart of a servant is the heart of Jesus Christ himself who said, "I came not to be served but to serve and to give my life as a ransom for the many" (Matthew 20:28). There is great joy, freedom, and strength of character for those who live this way of love and servanthood. Paul the Apostle tells us that "God’s love has been poured into our hearts through the Holy Spirit who has been given to us" (Romans 5:5). It is the transforming power of God’s love that can change not only individuals, but families and communities, old people and young, into servants of Jesus Christ who seek to live and serve together as disciples on mission. This book is not an exhaustive treatment of Christian servanthood, but it does seek to give an overview of what the New Testament says about servanthood and about the disciple’s relationship to Jesus Christ.

Myrna Colon

This paper explores a Biblical foundation for service learning. It provides a framework for educational institutions at all levels to integrate service in educational experiences that help students learn through active participation and reflection in an organized community activity. The paper addresses key biblical passages that serve as building-blocks for a Christian service learning model. It also includes some enlightening passages from the Spirit of Prophecy describing the significant role of service in Christian education and the seriousness with which Christian educators should emphasize its inclusion. In addition, reference is made to Southern Adventist University’s efforts to ensure that its graduates have the knowledge and experience in serving different communities. The paper includes ideas for practical applications of service learning in the curriculum.

Wayne Schock

Salmoon Shamaun

Joy truly comes in helping others. I have found when times are rough or you are hurting or lonely, true healing and peace can begin when you reach out to others who are in need. =================================================== Special Appeal for Poor Little Orphan Children for the Year 2015 From: - Changing Lives and Shaping Saints (Community Working) Greetings in the Name of our Lord Jesus Christ. Since, 2012 to 2014, we helped over 350 underprivileged Orphan Street boys and girls through our Volunteer’s workers local raised support by well off Christian here in my city. Our Street Children have been a chance to learn about Jesus Christ, Basic Education through our Trained Volunteers Teachers, Learn to swim, learn basic survival and first-aid skills and learn how to work with other children. More importantly, they were given the chance to develop Christian spiritual confidence, to feel wanted and to develop dreams for their future, dreams that have included becoming Pastors, Evangelists, Church Lay leaders and engineers, accountants, doctors and politicians. Thanks to generous local sponsors, we are well on our way to reaching our goal, but we still need help supporting .Will you help us meet our goal to provide these wonderful Orphan Street Children with worthwhile activities by supporting through our Ministry (Changing Lives and Shaping Saints). Your donation will have a dramatic impact on the life of these poor angels suffering poverty, diseases and lack of Education, Spiritual Development and basic body Nutrition. Needs and Requirements for 2015: Here is now detail what we are needed this year: • $100 – Per Every Child needed for clothes 100x50=5000 US$ for 2015 • $150 – Every Child will have need a spot at a week long summer camp with activities such as horseback riding, crafts, swimming, fishing and archery. 150x50=7500 US$ for 2015 • $2500 – Needed for 10 Computers, Sports Equipments, Multimedia and Food + Nutrition for 2015 Total Money needed this year to continue help these Helpless and Disadvantaged Christian Street Children are: 15000 US $ for the year 2015. Send your gift directly to us using the mailing address or the way which convenient to you. If you wish, you may use Western Union/ Money Gram and our Official Mailing Address below. All donations to Number One Non-Profit go directly to the Orphan Street Children and Vulnerable Community Youth of the area. We have been helping since 2012. Your gift will have tremendous impact on the life on Poor Helpless and Disadvantaged children and help them to have the skills, vision and motivation to change their lives. Thank you for partnering with us to help our Children and Youth to make them shaping saints. Please read the attached proposal document of our ministry that further describes our ministry’s its goals and details about our working in communities. Please bear us a hand in placing this trunk of compassion and love on our head. Because Changing Lives and Shaping Saints really brought up these Children by our Humanitarian Initiative. Then determine how much you will pledge to help sponsor us to serve Humanity. Thank you for taking the time to read attached document which signed by you will bring home to you the fact. And our pictures of the previous activities about community work here and my efforts to end it, something I wish for so that others do not have to go through the experiences and joy to work for the poor and suffering starved humanity. . Sincerely Evangelist Salmoon Shamaun (Consultant Director) Tel: +92-336-5493550/ +92-314-5369025 email. [email protected]. Skype salmoonjz Face Book Page of the Ministry: Changing Lives and Shaping Saints https://www.facebook.com/pages/Changing-Lives-and-Shaping-Saints/739611266118363 Postal Address: Salmoon Shamaun. P.O.Box Number 762, G.P.O. Rawalpindi Cantt, Pakistan (Diploma in Advance Business Management) from London Reading College. UK. Project Proposal Writer, Peer Educator, Community worker, Biblical Counselor

RERUM: Journal of Biblical Practice

Janes Sinaga , Naek Sijabat

One of the main problems faced by every country in the world today is problem of poverty, the problem seems to be continuous and endless. Poverty is still the biggest problem in the world today because this problem involves life and death. Poor people cannot get out of their problems without the help of others. The problem is that the poor don't know who to turn to to help them. If God's people were faithful in doing good to the poor and needy people, then their lives would be the same as what Jesus exemplified in His life while living on earth, and people like that would receive salvation. The act of helping those in need, especially the poor, on the other hand, is a natural fruit of salvation and is based on what Christ did for His people at Calvary. This article qualitatively uses analytical, comparative, and argumentative methods. Comparatively, the ladder model which is too rigid and normative while taking into account other examples will be compared with the garden mod...

The Review of Faith & International Affairs

Kristen Leslie

Paul Bradshaw

David Shepherd

Chris Hackett

RELATED PAPERS

Rania Farikha Rahmah

Marília Bettencourt Silva

Transplantation Journal

Cüneyt Aytekin

Journal of Economic Surveys

Stephen Jenkins

Ciriec Espana Revista De Economia Publica Social Y Cooperativa

Michel Capron

KEMYLLI FARINON

American Journal of Alzheimer's Disease & Other Dementiasr

International Journal of Radiation Oncology*Biology*Physics

DES RAJ BHAGAT

The Computer Journal

Linda Pagli

Kênya Moraes

Karl Aribeb

María Cecilia Paredes

Nemus: revista de l'Ateneu de Natura

Josep Quintana Cardona

International Journal of Higher Education Pedagogies

sharon tonner-saunders

Cornell University - arXiv

Piotr Kulpa

International Journal of Electronics

Muhammed Ali

Tiago Pires Marques

Ukuran Tali Kur Untuk Membuat Gelang

lutfi tututusong

Journal of Medical Imaging and Radiation Sciences

Bhaveet Radia

Virology Journal

Anne Laudisoit

Jurnal Informatika Ekonomi Bisnis

refni sulastri

Applied Sciences

Raul Fernandez-Garcia

Circulation

Mariella Catalano

See More Documents Like This

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

Village Hope International

(213) 335-3083

- Dec 14, 2020

Why Is Feeding Programs Important To The Community?

Updated: Jan 23, 2021

4 Ways School Feeding Programs Have Made An Impact To The Community

An estimate of 821.6 million people around the world does not have enough food. Economic crisis, political conflicts, natural disasters, and food price fluctuations contribute to hunger, especially in some of the world's most impoverished regions.

Sadly, children have been the most affected by world hunger. Hunger and poverty have kept children out of school, preventing them from having a promising future. It's for this reason that Village Hope International has stepped in to offer school feeding programs to malnourished children around the world.

The impact of these efforts has been simply incredible. The last few years have sealed the fact that school feeding programs generate a lasting impact that has shaped many nations' futures.

Here are some of the notable benefits of school feeding programs.

It promotes the health and development of children

The inadequate and improper diet causes malnutrition in growing children. This, in turn, hinders their development and activity. School feeding programs provide a simple and yet effective diet for children, which enhances their healthy development. It keeps nutrition diseases at bay, and children can reach adulthood.

It reduces poverty

As mentioned above, hungry children from low-income families do not have the luxury of going to school. They do not stand a chance of having a better future than their parents have. Hence, an unfortunate cycle of family poverty is almost unavoidable.

Feeding programs guarantee that such children have something to eat and look forward to going to school. What's more, every child, regardless of gender, has access to education . With education, they are better placed to complete education and have a better life in the future.

In addition, an increase in the number of children completing education in a community enhances the chances of that community experiencing a better economy and rising above poverty.

This is the power of well-fed children, thanks to the feeding programs.

It supports the children's guardians

It is the responsibility of parents/ guardians to cater to the needs of their children. However, poverty often renders these guardians helpless. The feeding programs benefit the children and their guardians since it takes the burden of feeding their children off their shoulders.

Without this responsibility, the guardians can concentrate on other tasks to enhance their way of life. This also means a lot of peace for them, knowing their children are fed in school.

It promotes local economies

Feeding programs are increasingly recognized as a huge investment in local businesses and human capital. The programs will often buy local produce to feed all the children in school, hence playing a huge role in promoting local economies, social stability, peace-building and national development.

School feeding programs have become a blessing to families, the community and the nation at large. It goes beyond the plate of food, delivering high areas in vital sectors such as education, health and nutrition, economies, agriculture, gender equality and social stability. Thanks to these programs, many children around the world have a reason to smile and look forward to the future.

- 4 Ways School Feeding Programs Have

What we can learn from school feeding programs from around the world

Andy chi tembon.

Senior Health Specialist

Join the Conversation

- Share on mail

- comments added

POLICY AND PRACTICE REVIEWS article

Establishing global school feeding program targets: how many poor children globally should be prioritized, and what would be the cost of implementation.

- 1 Partnership for Child Development, Imperial College, London, United Kingdom

- 2 World Food Programme, Rome, Italy

- 3 London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine, London, United Kingdom

The creation of Human Capital is dependent upon good health and education throughout the first 8,000 days of life, but there is currently under-investment in health and nutrition after the first 1,000 days. Working with governments and partners, the UN World Food Program is leading a global scale up of investment in school health, and has undertaken a strategic analysis to explore the scale and cost of meeting the needs of the most disadvantaged school age children and adolescents in low and middle-income countries globally. Of the 663 million school children enrolled in school, 328 million live where the current coverage of school meals is inadequate (<80%), of these, 251 million live in countries where there are significant nutrition deficits (>20% anemia and stunting), and of these an estimated 73 million children in 60 countries are also living in extreme poverty (<USD 1.97 per day). 62.7 million of these children are in Africa, and more than 66% live in low income countries, with a substantial minority in pockets of poverty in middle-income countries. The estimated overall financial requirement for school feeding is USD 4.7 billion, increasing to USD 5.8 billion annually if other essential school health interventions are included in the package. The DCP3 (Vol 8) school feeding edition and the global coverage numbers were launched in Tunis, 2018 by the WFP Executive Director, David Beasley. These estimates continue to inform the development of WFP's global strategy for school feeding.

Introduction

The World Food Program (WFP) is the United Nations lead organization on school feeding. Recent analyses indicate that the world has underinvested in the health and nutrition of school age children and adolescents, especially in low and middle-income countries, with negative consequences for the creation of human capital. WFP is therefore aiming to increase global investment in school feeding and school health, and has undertaken, with partners, a high-level analysis of the scale of need, to enhance the precision of strategic planning.

A Paradigm Shift in Thinking About Human Development

It is now recognized that a major constraint on global development is the current under-investment in school age children and adolescents. A series of analyses published since 2017 have emphasized that there is a need to invest in child health, nutrition, and education throughout the first 8,000 days of life if children are to grow up to fulfill their potential as adults ( 1 – 3 ). Schools are the key to delivering these school health, school feeding, and education interventions, and thus serve as critical enabling platforms for the creation of human capital. The UN World Food Program is reimagining its role in this new vision of development ( 4 ), and in this publication sets out the way it is estimating the scale and scope of the interventions that it should provide to support the children most in need.

Investing in human capital—the sum of a population's health, skills, knowledge, and experience—can strengthen a country's competitiveness in a rapidly changing world ( 3 ). Child health and learning are critical to human capital development. A well-nourished, healthy, and educated population is the foundational pre-requisite for growth and economic development. A key contributor to the ranking in the Human Capital Index published by the World Bank is the quality of learning in a country, as measured by the new metric Learning Adjusted Years of Schooling (LAYS), which measures not only the amount of schooling, but also the quality of learning ( 5 ). School feeding can have a positive impact on LAYS through increasing attendance, particularly of girls, and by improving learning. Low-income countries in Africa have potentially the most to gain from school feeding since they represent 25 out of the 30 countries with the lowest Human Capital Index rankings. For many of these countries, underinvestment in human capital leads to a loss of economic potential, ranging from 50 to 70 percent in the long-term. Africa's Human Capital Index score puts the region at 40% of its potential, which implies that Africa's GDP could be 2.5 times higher if the benchmarks for health and education were achieved.

The 2017 3rd edition of the World Bank Disease Control Priorities (DCP3) , supported by the Gates Foundation, provides a new perspective on investing in child development ( 1 ). In particular, Volume 8, entitled Child and Adolescent Health and Development , confirms the importance of investing in the first 1,000 days of life, and also highlights the need to continue investment during key periods for development during the next 7,000 days, or until the early twenties. These findings have led to a move toward a new 8,000 days paradigm. Just as babies are not merely small people, they need special and different types of care from the rest of us, so growing children and adolescents are not merely short adults. They too have critical phases of development that need specific interventions, especially in the phases of pre-puberty, puberty, and during late adolescence.

The important role of schools in investing in children was emphasized by the UN Standing Committee on Nutrition in 2017, in a statement entitled Schools as a System to Improve Nutrition , which emphasizes the importance of school health and school feeding ( 2 ). Similarly, a publication prepared by the World Bank and the Global Partnership for Education entitled Optimizing Education Outcomes: High-Return Investments in School Health for Increased Participation and Learning ( 6 ), took this a step further, emphasizing the need to fix the almost complete mismatch between investments in the health of children, currently almost all focused on children under 5 years of age, and investment in education, mostly between 5 and 20 years of age.

Crucial Investments in Children and in Human Capital

Disease Control Priorities Volume 8 ( 1 ) lists several elements of an essential package, including simple and cheap health interventions that promote education outcomes, such as deworming, correcting refractive errors (e.g., myopia, astigmatism, and hypermetropia), and malaria prevention. Within this essential package, school feeding is the most costly component, on an annual basis, essentially due to the fact that meals are delivered to children more frequently than any other intervention of the package, but is never-the-less cost-effective due to the multiple benefits it delivers. A recent Benefit-Cost Analysis ( 7 ) shows that school feeding programs could have substantial benefits for the costs invested, with about $20 of returns for $1 invested in school feeding programs, a return on investment comparable to several of the best-buy interventions analyzed by the Copenhagen Consensus exercise 1 . The large scale of benefits reflects the additive returns on investment from multiple sectors ( 8 ). For example, the analysis examined the returns in 14 low- and middle-income countries, and showed average Benefit-Cost Ratios of 13.5 to education (through human capital), 6.7 to the local economy (through local procurement and local employment), and 0.8 to social protection (the externality effect of the social safety net) and to health ( 7 ). Other potentially substantial and additional returns, for example to gender and peace-building, have yet to be quantified ( 4 ).

The World Bank's State of Social Safety Nets 2018 and the underlying ASPIRE database show that whilst school feeding is not the largest safety net worldwide (in terms of beneficiary numbers), it is the most widespread (in terms of number of countries). This highlights that not only has school feeding emerged as the main intervention for children in school, but also as the most widespread safety net worldwide regardless of the beneficiaries' category or age group.

Number of beneficiaries by category of safety net * (sorted by decreasing order):

- Fee waivers: 382 M people

- School feeding: 357 M people

- Food and in-kind aid: 282 M people

- Unconditional cash transfers: 278 M people

- Conditional cash transfers: 185 M people

- Public works: 103 M people

- Social pensions: 83 M people

* The categories of social safety nets listed here are based on the World Bank's State of Social Safety Nets 2018 . Fee waivers encompass health insurance exemptions and reduced medical fees, education fee waivers, food subsidies, housing subsidies and allowances, utility and electricity subsidies and allowances, agricultural inputs subsidies, and transportation benefits.

Number of countries which have a safety net, by category (sorted by decreasing order):

- School feeding: 116 countries

- Unconditional cash transfers: 90 countries

- Public works: 81 countries

- Food and in-kind aid: 77 countries

- Fee waivers: 65 countries

- Social pensions: 64 countries

- Conditional cash transfers: 60 countries

In real-world practice, school feeding has emerged as the main intervention for children in schools around which other elements, such as deworming or supplementation are delivered. Almost every country in the world provides food to its school children in some scale, in 2013 reaching about 368 million children worldwide ( 9 ).

When linked to good nutrition and education, well-designed equitable school feeding programs contribute to child development through increased years of schooling, better learning, and improved nutritional status ( 10 , 11 ). School feeding provides consistent positive effects on energy intake, micronutrient status, school enrolment, and attendance of children ( 12 – 14 ). The effects are particularly strong for girls. In its influential 2016 report, The International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity , chaired by Gordon Brown, identified 13 nonteaching interventions as “highly effective practices to increase access and learning outcomes,” these included three health-related programs: school feeding, malaria prevention, and micronutrient intervention. A recent UN agency review of evidence finds that school feeding is one of the two interventions with the strongest evidence of impact on equity and inclusion (the other one being conditional cash transfers) ( 11 ).

School feeding is one of the most common safety nets ( 15 , 16 ), providing the daily support and stability that vulnerable families and children need, and was shown to be one of the first social protection solutions that poor countries turned to during the social shocks of the 2008 financial crisis ( 13 , 17 ). Finally, well-designed school feeding programs that procure food locally may offer major additional benefits, including an increased dietary diversity, new employment opportunities for women and/or smallholder farmers, and improved livelihoods for the local communities. Well-designed school feeding programs can specifically contribute to women's economic empowerment and decision-making by deliberately engaging women farmers and traders, and providing job opportunities to women in school canteens ( 4 , 14 ).

This “new-generation” vision of school feeding has led the World Food Program to ask not only whether more can be done to support school feeding in low and middle-income countries, but also to try and determine which groups should be prioritized as most in need, and what would be the scale of need and the cost implications. These are real-world questions about the world today, which will shape the new global school feeding strategy of WFP. This paper shares the approach that WFP has used in answering these questions, in order to encourage understanding and to stimulate debate.

Methods and Results

This section explains the methodology used by addressing a series of questions which indicate the sequential methodological steps used to estimate the scale of need and the cost of addressing the need. The first step was to estimate the number of children enrolled in school, and the number of children in schools currently covered by school feeding programs. The next step was to estimate the scale and location of the population of school children that are not covered by a school feeding program. This was followed by applying a sequence of indicators as filters to identify those most in need of school health and school feeding programs. Finally, published benchmarks were used to estimate the cost of reaching the population as identified most in need based on the previous step.

How Many School Children Are There in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Globally, and How Many Receive School Meals?

UNESCO, the United Nations lead on Education is a ready source for regularly updated estimates of the numbers of school children in low and middle-income countries ( 18 ). Remarkably, there is no single global source that records how many of them receive school meals, or benefit from school health programs. The World Bank SABER (Systems Approach for Better Education Results) tool ( 19 ) potentially could provide an answer, and the World Bank is currently updating and revising its SABER tools to better fulfill this function.

In 2013, WFP led the first coherent attempt to address this question ( 9 ) and is establishing a continuous monitoring process, but for now, we have to rely on multiple different sources, from various dates, to build up a picture. There are four main sources:

• the WFP publication State of School Feeding Worldwide, which has been published once, in 2013, and which reports data from national statistics and the WFP country offices ( 9 );

• the WFP publication Smart School Meals: Nutrition-Sensitive National Programs in Latin America and the Caribbean ; published in 2017, this reports data on national programs in the LAC region ( 20 );

• the World Bank publication: The State of Social Safety Nets , 2018 edition ( 16 );

• the African Union publication: Sustainable School Feeding , published in 2018 ( 21 ).

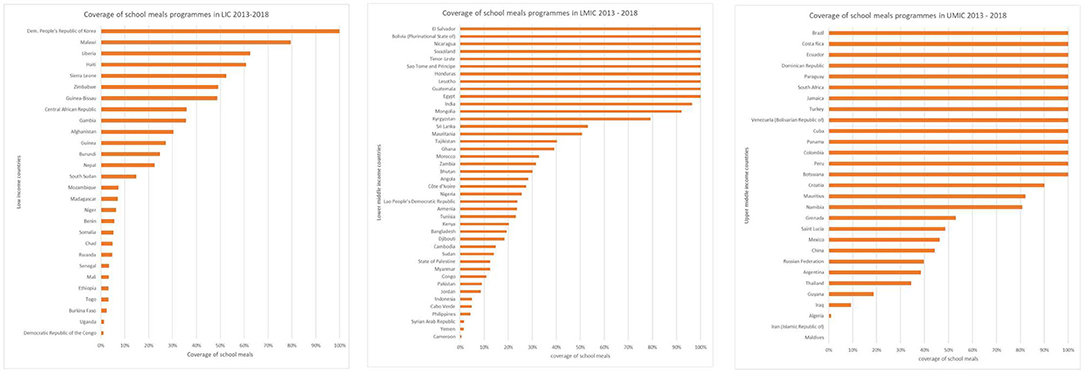

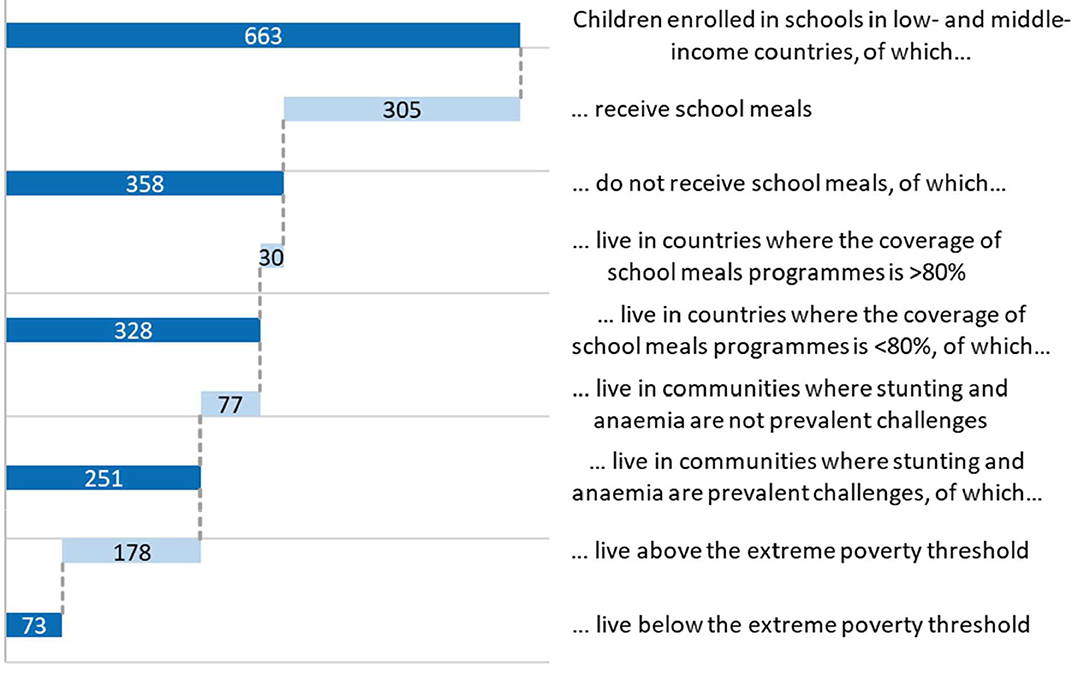

The data suggest that there are 663 million school children enrolled in low- and middle-income countries globally. The countries vary in the number and proportion of these children who receive school meals (see Figure 1 ).

Figure 1 . Proportion of children who receive school meals by country and income level.

At least 305 million children are estimated to be fed at school every day of the school year. This suggests that 54% of the 663 million children enrolled in school in low- and middle-income countries do not currently receive meals at school. The key question going forward is what proportion of these children would benefit most from making these meals available.

A Scoping Exercise: What Is the Likely Scale of Need, and What Indicators Are Available to Identify Populations in Need?

In order to refine the filters for identifying targets, we first explored which indicators might best be used to define population in need. The purpose of this preliminary step was to provide an order of magnitude estimate of the need for school feeding globally, before proceeding to more refined analysis. This order of magnitude is comprised of several estimates, calculated by applying various indicators to the same numerator: the number of children enrolled in schools in low- and middle-income countries (663 million children). Some of these indicators aimed to capture the scale of need for school feeding (metrics of extreme poverty, acute food insecurity, and chronic hunger), while others reflected the capacity of national governments and the international community to respond to that need (ranking against the published DCP3 benchmarks, which are described further below, and formal declaration of a national emergency).

These estimates were first calculated at the country level: for example, by using the published poverty rates, which vary between countries. The poverty rate of each country (expressed as the percentage of the population living in poverty for that country) is first applied to the school-going population of that country (expressed as the number of children going to school) to estimate the number of poor schoolchildren in that country. Country-level estimates are then summed across income groups to generate an estimate of poor schoolchildren in low- and middle-income countries.

The “DCP3 benchmarks” correspond to a hypothetical scenario proposed by the World Bank DCP3 publication as a realistic target for governments in the medium term ( 1 ). This target would be to provide coverage to 20% of school-going children in low-income countries and 40% of schoolchildren in middle-income countries. The DCP3 publication suggests that these percentages represent the minimum proportion of school-going children that would need health and nutrition support to successfully complete their education ( 1 ). If the current levels of coverage were found to be lower than these percentages then they were deemed insufficient to meet the needs of that population.

The analysis explored six indicators:

1. The benchmark in Disease Control Priorities ( 1 ): 20% of all school children in LICs and 40% in MICs.

2. The World Bank extreme poverty threshold ($1.90/day) ( 22 ).

3. The FAO estimates of chronic hunger (percentage of undernutrition) ( 23 ).

4. A combination of both the poverty and hunger metrics above.

5. The International Phase Classification and estimates of people living in acute food insecurity (IPC 3 and above)” ( 24 ).

6. Countries with a declared L2 or L3 emergency * ( 25 ).

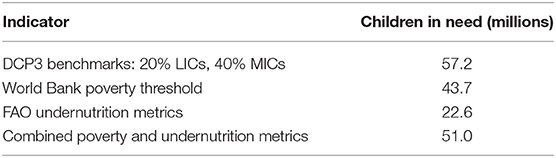

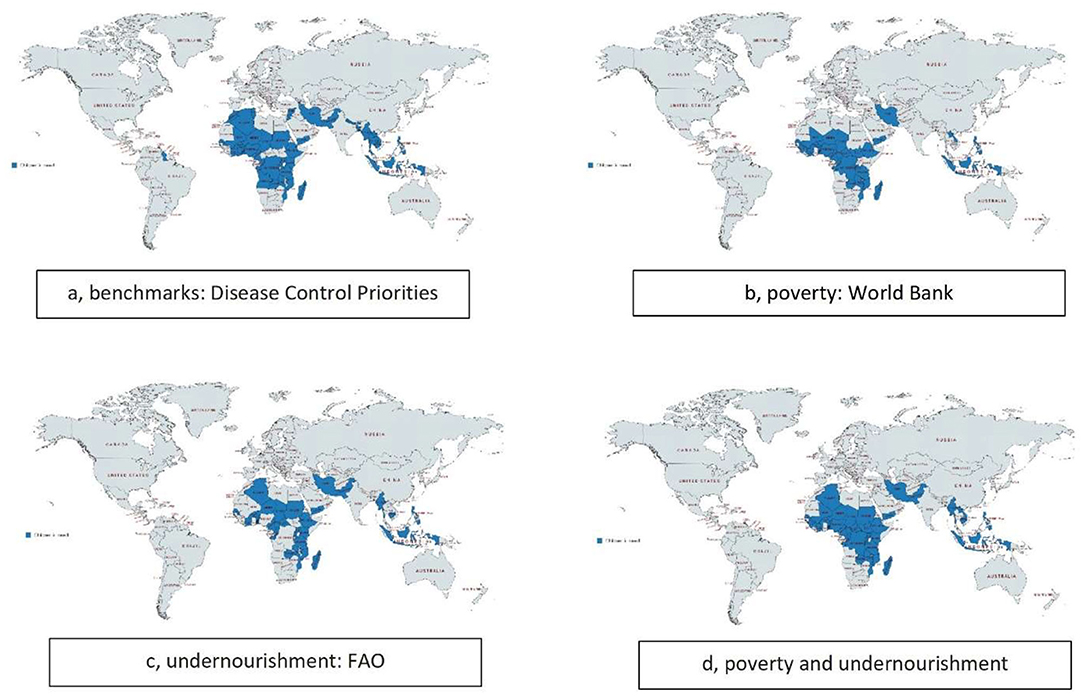

The results of these analyses for the first 4 indices are shown in Table 1 , which indicates that the scale of all these estimates is remarkably similar at around 40–50 million children.

Table 1 . Number of children in need of school feeding, and number of countries; based on different indicators of need [sources ( 1 , 22 , 23 )].

* L2 and L3 refer to the two superior levels of emergency classification in a three-level scale defined by WFP as per WFP Emergency Response Classifications, 2014 .

Mapping the countries in which these children are found, Figure 2 , also suggests broad similarities, with most of the at risk populations clustered in Africa, with some in South and South East Asia, but few elsewhere. The poverty and hunger indicators unsurprisingly suggest considerable overlap of these two conditions, and also demonstrates that combining the two indicators helps broaden the safety net, and includes more children at risk.

Figure 2 . Distribution of children in need of school feeding in low- and middle-income countries globally.

The final two indices which were considered, IPC and L2/3, are intended as real-time measures of emergency need. Unsurprisingly, these turn out to be highly geographically focused measures that, in the years examined, suggested the in-need populations of school age children were of the order of 1–6 million (data not shown). While these are large populations in terms of mobilizing emergency care, they are clearly underestimates of the scale of the populations of children with long-term developmental needs. IPC and L2/3 are appropriate indicators for identifying operational targets at the country level, but too narrow for the present purpose, and were accordingly not pursued.

Which Current National School Feeding Programs Have Sub-optimal Coverage?

The analyses above indicate that there are 663 million children enrolled in schools in low- and middle-income countries, and that 305 million of these children receive school meals. Note that this figure excludes the ~13 million children who currently receive meals from WFP operations in these countries, as a key purpose of this exercise is to identify the role of other partners. The data does not show which children are targeted, and it is at least probable that many programs are regressive and a majority of these children are from the most affluent segments of the population. To develop a benchmark for addressing this question, the analysis considered the targets used by actual programs. For example, the long-standing and successful national program in South Africa, CSTL ( Care and support for teaching and learning) targets the lower three quintiles of the school population, that is, 60% of the total population ( 26 ).

Taking a conservative view, it is assumed here that a school-feeding program which covers the lower four quintiles (that is, 80%) will likely ensure that all children in need are fed. Hence a target was set at 80% coverage (total number of children in school/number fed), a level which is taken to indicate confidence that coverage is already reaching most children in need, while populations below this threshold should be explored further. The reported coverage by country is shown in Figure 1 . Using that cut-off, the population in need is reduced to the 328 million school children living in countries with sub-optimal access (<80% coverage) to school meals programs.

Where Is School Feeding Most Likely to Make a Difference?

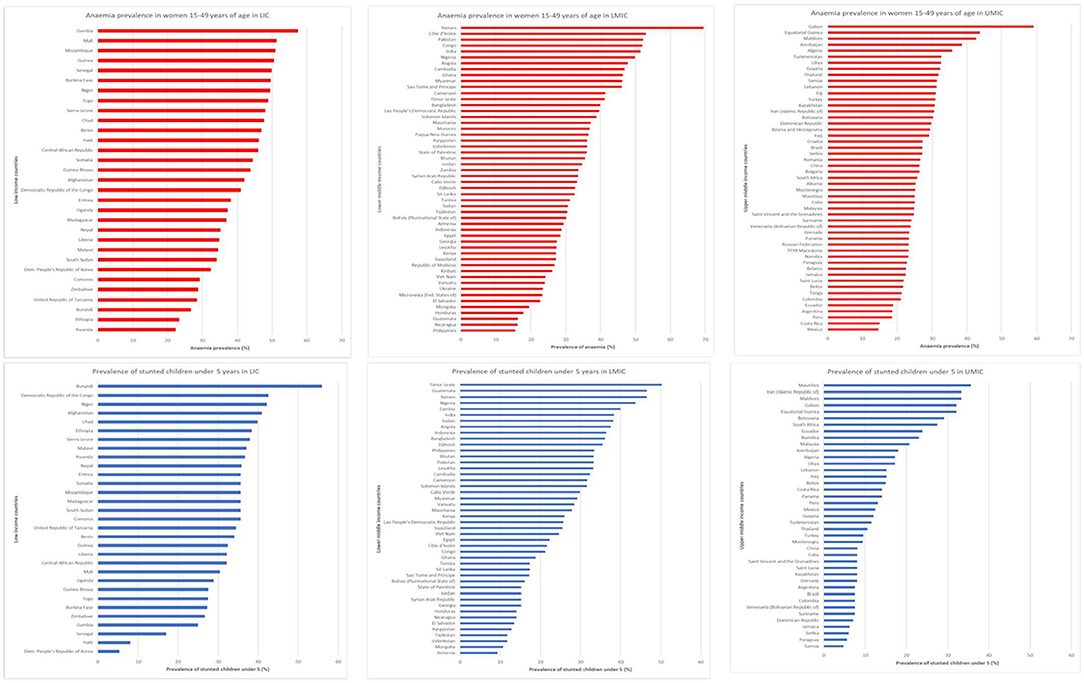

Providing food and nutrition sensitive interventions is likely to be most effective where undernutrition is prevalent. The scoping exercise has also shown, using the FAO undernutrition measure ( 23 , 27 ), that nutrition indicators could add a useful dimension to the targeting. In order to enhance the precision of this approach, and to use nutrition metrics which are generally available in countries, the two commonly available metrics of prevalence of anemia and stunting were adopted. No health indicator is collected regularly from the target school-age children or from adolescents, so the analysis used the standard reported metrics of prevalence of anemia in women of reproductive age, which is routinely collected at antenatal clinics, and prevalence of stunting in children <5, which is routinely collected as part of child health surveillance ( 27 ). The former is an indicator of current dietary lack, and the latter integrates undernutrition over time. These data are shown in Figure 3 .

Figure 3 . Prevalence of anemia (in women of reproductive age) and stunting (in children <5 years), by country, and income level [data from ( 23 )].

Using these filters, the target population was further refined to the 251 million who live in communities where anemia and stunting were existing challenges.

Community Resilience and Journey to Self Reliance

Development investments are most effective in the long-term if they help countries to develop sustainable programs, as has been widely acknowledged by the humanitarian and development community, following the 2016 World Humanitarian Summit, and WFP is committed to this objective. But the target children of most immediate and greatest need are those least able to progress to self-reliance, or those for whom that journey has just begun.

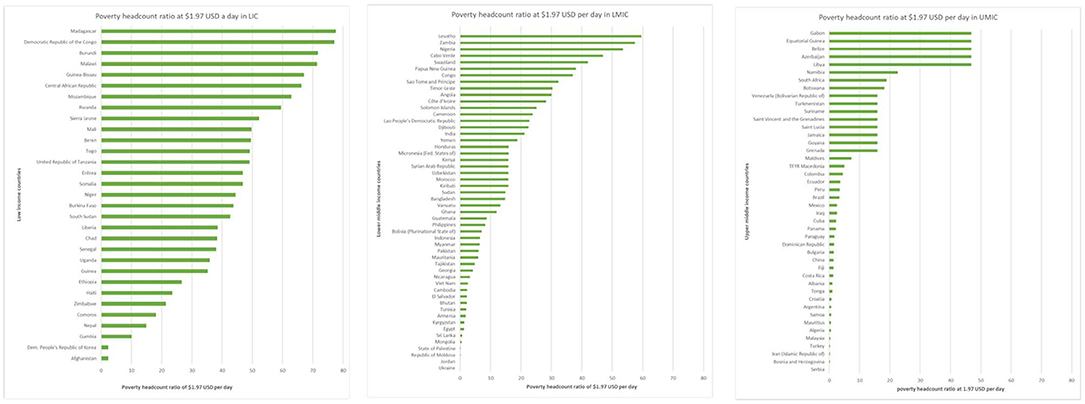

WFP advocates for the universal adoption of school feeding programs and is committed to supporting all governments develop their national school feeding programs. However, a line must be drawn between communities which, despite their limited resources, have reached a certain level of resilience to support their own needs for school feeding, and those in which immediate needs exceed their current capacity and require public institutions, such as their governments and/or international agencies, to provide them with social assistance and school feeding. For this reason, it appeared that extreme poverty was the most relevant indicator to draw this line, and the World Bank International Poverty Line (living on <$1.90 per day ( 22 ), as shown in Figure 4 was used as the final filter to identify the target population. Using this filter, the target population was finally refined to 73 million children in 60 countries.

Figure 4 . Proportion of populations living in extreme poverty, by country and income level ( 22 ).

What Is the Cost of Reaching Those Most in Need?

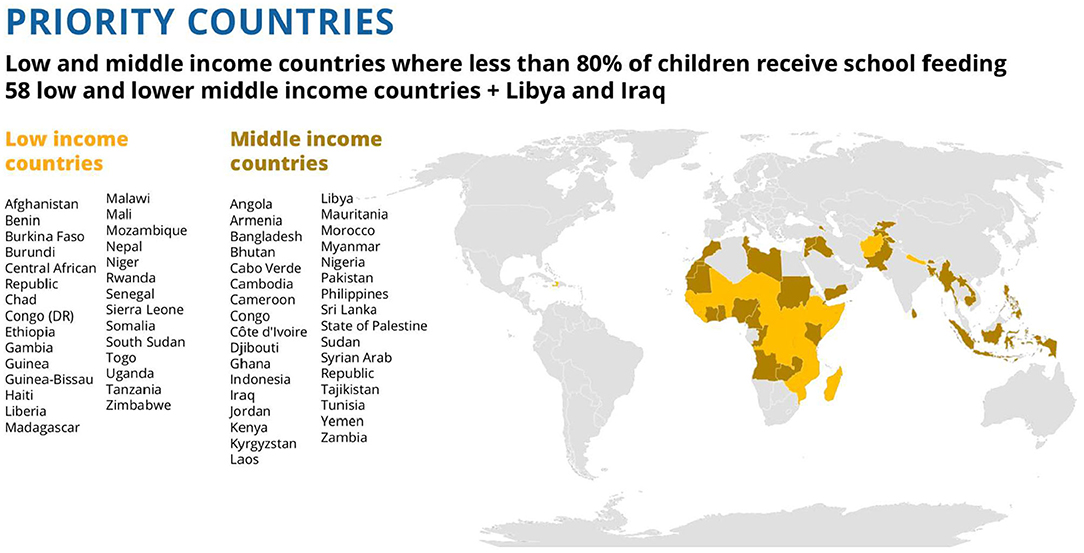

The sequential analyses illustrated in Figure 5 below have reduced the target population to 73 million who are most in need, living in 60 countries. The list of countries and their geographical distribution is shown in Figure 6 .

Figure 5 . Sequential analysis for determining target population most in need.

Figure 6 . List of 60 priority countries and their geographical location.

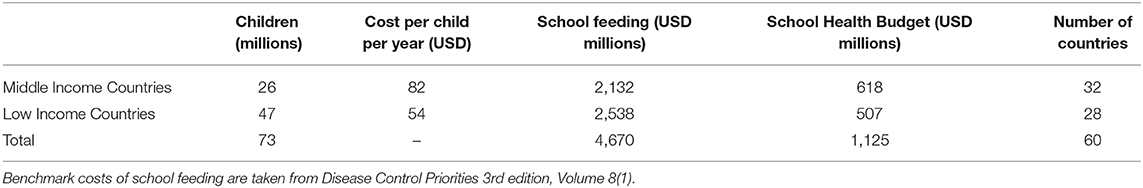

The cost of school feeding for the 73 million children was calculated based on published benchmark costs of providing school meals for low- and middle-income countries (see Table 2 ).

Table 2 . The cost of covering 73 million children in need of school feeding is 4.7 billion USD, an average of $64 per child per year.

The WFP strategy recognizes that the outcome of the interventions will be optimized by the synergistic effects of a combination of school feeding and school health interventions ( 27 , 28 ). The additional cost of including school health interventions was explored using the essential school health package for children from 5 to 14 years suggested in Disease Control Priorities ( 1 , 27 ). These analyses are shown in Table 2 , indicating an additional cost of about 20% more for the low-income package and 29% for the middle-income package, or an annual cost of USD 507 and 618 million, respectively. The total cost of the combined school feeding and school health package for the 73 million children would therefore be USD 5.8 billion annually, with around half that amount for the low income countries alone.

Conclusions

The analysis described in this paper is the first of a sequence of studies by WFP to refine its targets for a global effort to make school feeding available to all children in need. To encourage debate and improve the quality of programs, WFP intends to share these studies in a sequence of publications.

The analysis suggests that in low- and middle-income countries globally there are some 73 million children most in need of school feeding programs, based on: not covered by national government programs; the inadequacy of current provision, the prevalence of indicators of poor nutrition, and the relative lack of financing for the countries to implement the programs themselves. Most of these children (62.7 million) are in Africa. The majority, more than 66%, live in low-income countries, but there is also a substantial minority who live in pockets of poverty in middle-income and high-middle income countries.

Addressing these needs in all 60 countries would require an extra USD 5.8 billion annually. Of this total, some USD 3 billion annually would be required to provide and resource school feeding and school health in the low-income countries alone. The additional annual amount required for middle-income countries would be some USD 2.7 billion. For these countries, it would seem probable that a substantial proportion of these resources could be made available from domestic funds. Indeed, in all cases, the logic of investing in human capital creation is that these investments in its young people today would set the country on the road to self-reliance, such that an increasing proportion of costs could be met from domestic resources. Further analyses are underway to optimize transition arrangements, including studies of successes, such as the announcement by Kenya in 2018 that the national program, established in 2006 with co-financing from WFP, was now wholly supported through domestic sources ( 29 ).

The main conclusion for now, however, is that there is currently a significant unmet need for support to school children and adolescents in low and middle-income countries, and that meeting this need is an important first step in helping a nation's young people achieve their full potential in life, and in helping these countries to increase their rank on the Human Capital Index and create economic growth ( 30 – 32 ). To achieve this, there is a clear need for better health and nutrition data, research, and evidence-based advocacy.

WFP is embarking on a 10 year program of support to countries, leading up to the SDG goals in 2030. The analyses described here are being used by WFP to estimate the overall scale of the response required, and so to increase the precision of planning the future allocation and procurement of new resources. These are high-level estimates, for strategic purposes. Programming at the national level continues to be based on country-level or sub-national level data, and led by the countries themselves. The DCP3 (Vol 8) school feeding edition and the global coverage numbers were launched in Tunis, 2018 by the WFP Executive Director, David Beasley. These estimates continue to inform the development of WFP's global strategy for school feeding.

WFP plans to publish further analyses, and invites comments and contributions that can help improve the quality of these analyses and the programs that result from them.

Author Contributions

CB is the Director of the School Feeding Service of WFP, and conceived the need for this analysis to support strategic planning. LD is the Executive Director of the Partnership for Child Development (PCD) and planned and led the work. MF, NL, and KC executed the analysis. DB is a Senior Advisor to WFP and provided policy guidance. All other authors are staff or affiliates of WFP or PCD, and contributed to the execution of the analysis. The paper was drafted by DB, LD, and CB, with contributions from all authors.

The study was funded by a World Food Programme grant to Imperial College London, Grant No. P76324.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the World Food Program (WFP).

1. ^ Available online at: https://www.copenhagenconsensus.com

1. Bundy DAP, de Silva N, Horton S, Jamison DT, Patton DC. Child and Adolescent Health and Development (with a Foreword by Gordon Brown). In: Jamison DT, Nugent R, Gelband H, Horton S, Jha P, Laxminarayan R, Mock C, editors. Disease Control Priorities, 3rd edn. Vol. 8 . Washington, DC: The World Bank. Available online at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/bitstream/handle/10986/28876/9781464804236.pdf?sequence=3&isAllowed=y

2. United Nations System Standing Committee on Nutrition (UNSCN). Schools as a System to Improve Nutrition. Oenema S, editor. Rome: the UNSCN Secretariat (2017). Available online at: https://www.unscn.org/uploads/web/news/document/School-Paper-EN-WEB.pdf

3. World Bank. The Human Capital Project. In: Gatti R, Kraay A, editors. Washington, DC: The World Bank (2018). 50 p. Available online at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/363661540826242921/pdf/131462-PublicHCPReportCompleteBooklet.pdf

Google Scholar

4. Bundy DAP, de Silva N, Horton S, Jamison DT, Patton GC, editors. Re-Imagining School Feeding: A High Return Investment in Human Capital and Local Economies (with a Foreword by Gordon Brown, a Preface by David Beasley and Jim Yong Kim, and a Prologue by Carmen Burbano, David Ryckembusch, Meena Fernandes, Arlene Mitchell and Lesley Drake). A special edition with the Global Partnership for Education. In: Jamison DT, Nugent R, Gelband H, Horton S, Jha P, Laxminarayan R, et al., editors. Disease Control Priorities , 3rd edn. Washington, DC: The World Bank (2018). Available online at: http://dcp-3.org/sites/default/files/resources/CAHD_eBook.pdf

5. Filmer D, Rogers H, Angrist N, Sabarwal S. Learning-Adjusted Years of Schooling (LAYS). Defining a New Macro Measure of Education Policy Research Working Paper 859. September 2018. Washington DC: World Bank Group (2017). Available online at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/243261538075151093/pdf/WPS8591.pdf

6. Bundy DAP, de Silva N, Horton S, Jamison DT, Patton GC. Optimizing education outcomes: high-return investments in school health for increased participation and learning. In: Jamison DT, Nugent R, Gelband H, Horton S, Jha P, Laxminarayan R, et al., editors. Disease Control Priorities. 3rd edn. Washington, DC: The World Bank (2018). Available online at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/781571521530863121/pdf/124419-PUB-PUBLIC-pubdate-3-20-18.pdf

7. Verguet S, Limasalle P, Chakrabarti A, Husain A, Burbano C, Drake L, et al. The broader economic value of school feeding programs in low- and middle-income countries: estimating the multi-sectoral returns to public health, human capital, social protection, and the local economy. Front Public Health . (2020) 8:587046. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.587046

CrossRef Full Text

8. Alderman H, Bundy DAP. School feeding programs and development: are we framing the question correctly?. World Bank Res Observ. (2011) 27:204–21. doi: 10.1093/wbro/lkr005

CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

9. WFP (World Food Programme). The State of School Feeding Worldwide . Rome: WFP (2013). Available online at: https://documents.wfp.org/stellent/groups/public/documents/communications/wfp257481.pdf?_ga=2.84605977.1491961294.1564494036-1398024210.1564494036

10. Jomaa LH, McDonnell E, Probart C. School feeding programs in developing countries: impacts on children's health and educational outcomes. Nutr Rev. (2011) 69:83–98. doi: 10.1111/j.1753-4887.2010.00369.x

PubMed Abstract | CrossRef Full Text | Google Scholar

11. UNESCO. Making Evaluation work for the achievement of SDG4 Target 5: Equity and Inclusion in Education . IOS Evaluation Office. Mundy K, Proulx K, Manion C, editors. Norad, World Bank, UNICEF; UNESCO: Paris (2019). 56 p.

12. Adelman S, Gilligan DO, Konde-Lule J, Alderman H. School Feeding Reduces Anemia Prevalence in Adolescent Girls and Other Vulnerable Household Members in a Cluster Randomized Controlled Trial in Uganda. J Nutr. (2019) 149:659–66. doi: 10.1093/jn/nxy305

13. Bundy DAP, Burbano C, Grosh M, Gelli A, Jukes M, Drake L. Rethinking School Feeding: Social Safety Nets, Child Development, the Education Sector . From Directions in Development. The World Bank (2009). Available online at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/EDUCATION/Resources/278200-1099079877269/547664-1099080042112/DID_School_Feeding.pdf

14. WFP, FAO, IFAD, NEPAD, GCNF, PCD. Home-Grown School Feeding. Resource Framework. Technical Document, Rome (2018). Available online at: https://www.wfp.org/content/home-grown-school-feeding-resource-framework

15. International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity. The Learning Generation: Investing in Education for a Changing World . International Commission on Financing Global Education Opportunity, New York (2016). Available online at: http://report.educationcommission.org ; https://report.educationcommission.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/Learning_Generation_Full_Report.pdf

16. Gentilini U, Honorati M, Yemtsov R. The State of Social Safety Nets 2014. Working Paper 87984, World Bank, Washington, DC (2014). Available online at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/302571468320707386/pdf/879840WP0FINAL00Box385208B00PUBLIC0.pdf

17. Grosh M, del Ninno C, Tesliuc ED. Guidance for Responses from the Human Development Sector to Rising Food Fuel Prices . Working Paper 45652, World Bank, Washington, DC (2008). Available online at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/SAFETYNETSANDTRANSFERS/Resources/HDNFoodandFuel_Final.pdf

18. UNESCO Institute for Statistics (UIS). Enrolment in primary education, both sexes (number). Available online at: http://data.uis.unesco.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=EDULIT_DS (Data extracted 30 August 30, 2018)

19. World Bank. SABER: School Health and School Feeding: Smarter Education Systems for Brighter Futures: Education Global Practice Brief: 2016 . Washington, DC: World Bank Group (2016). Available online at: www.worldbank/education/saber/schoolhealth

20. WFP. Smart School Meals: Nutrition-Sensitive National Programmes in Latin America the Caribbean: A Review of 16 Countries . Rome: WFP (2017). 39 p. Available online at: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/WFP-0000019946/download/?_ga=2.88863771.1491961294.1564494036-1398024210.1564494036

21. The African Union. Sustainable School Feeding across the African Union . Addis Ababa: African Union (2018). p. 16–29. Available online at: https://au.int/sites/default/files/documents/36100-doc-sustainable_school_feeding_1.pdf

22. World Bank, World Development Indicators. Poverty Headcount Ratio at $1.90 a Day (2011 PPP) (% of Population) [Data file] . Washington DC: The World Bank (2018). Available online at: http://api.worldbank.org/v2/en/indicator/SI.POV.DDAY?downloadformat=excel (Data extracted August 30, 2018).

23. FAO IFAD UNICEF WFP and WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World 2018 . FAO: Rome (2018). p. 116–27. Available online at: http://www.fao.org/3/i9553en/i9553en.pdf

24. Food Security Information Network (FSIN). Global Report on Food Crises 2018 . (2018). Available online at: http://www.fsincop.net/fileadmin/user_upload/fsin/docs/global_report/2018/GRFC_2018_Full_report_EN.pdf

PubMed Abstract

25. WFP. WFP Emergency Response Classification . (2014). Available online at: https://docs.wfp.org/api/documents/278134b5c2d74f55bfe340764b3ab561/download/

26. Department of Basic Education and MIET Africa. The CSTL Programme: Care and Support for Teaching and Learning. National Support Pack, Conceptual Framework . MIET Africa: Durban, Republic of South Africa (2010).

27. Bundy DAP, de Silva N, Horton S, Patton GC, Schultz L, Jamison DT. Investment in child and adolescent health and development: key messages from Disease Control Priorities, 3rd Edition. Lancet . (2017) 85–92. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32417-0

28. Albright A, Bundy DAP. The Global Partnership for Education: forging a stronger partnership between health and education sectors to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals. Lancet Child Adolesc. (2018). 2:473–4. doi: 10.1016/S2352-4642(18)30146-9

29. World Food Programme Insight. A Major Milestone in Kenya's School Meals Programme. (2018). Available online at: https://insight.wfp.org/a-major-milestone-in-kenyas-school-meals-programme-b7fea5928b34 (accessed July 28, 2019).

30. Burbano C, Ryckembusch D, Fernandes M, Mitchell A, Drake L. Re-imagining school feeding: a high return investment in human capital and local economies . In: Bundy DAP, de Silva N, Horton S, Jamison DT, Patton G, editors. Disease Control Priorities, 3rd ed., Vol. 8, Child and Adolescent Health and Development. Washington, DC: World Bank (2018), xiii–xxiii.

31. Drake L, Fernandes M, Aurino E, Kiamba J, Giyose B, Burbano C, et al. School feeding programs in middle childhood and adolescence. In: Bundy DAP, de Silva N, Horton S, Jamison DT, Patton GC, editors. Disease Control Priorities, 3rd ed., Vol. 8, Child and Adolescent Health and Development . Washington, DC: World Bank (2018). p. 135–52.

PubMed Abstract | Google Scholar

32. UNICEF. The Innocenti Framework on Food Systems for Children and Adolescents. Food systems for children and adolescents. Available online at: https://www.unicef.org/nutrition/food-systems_103432.html (accessed July 28, 2019).

Keywords: schoolchildren, adolescents, school health, school feeding, poverty, child development, human capital, nutrition

Citation: Drake LJ, Lazrak N, Fernandes M, Chu K, Singh S, Ryckembusch D, Nourozi S, Bundy DAP and Burbano C (2020) Establishing Global School Feeding Program Targets: How Many Poor Children Globally Should Be Prioritized, and What Would Be the Cost of Implementation? Front. Public Health 8:530176. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2020.530176

Received: 10 February 2020; Accepted: 26 October 2020; Published: 02 December 2020.

Reviewed by:

Copyright © 2020 Drake, Lazrak, Fernandes, Chu, Singh, Ryckembusch, Nourozi, Bundy and Burbano. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY) . The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Lesley J. Drake, Lesley.drake@imperial.ac.uk

† These authors share co-first authorship

‡ These authors share co-senior authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Undergraduate

- High School

- Architecture

- American History

- Asian History

- Antique Literature

- American Literature

- Asian Literature

- Classic English Literature

- World Literature

- Creative Writing

- Linguistics

- Criminal Justice

- Legal Issues

- Anthropology

- Archaeology

- Political Science

- World Affairs

- African-American Studies

- East European Studies

- Latin-American Studies

- Native-American Studies

- West European Studies

- Family and Consumer Science

- Social Issues

- Women and Gender Studies

- Social Work

- Natural Sciences

- Pharmacology

- Earth science

- Agriculture

- Agricultural Studies

- Computer Science

- IT Management

- Mathematics

- Investments

- Engineering and Technology

- Engineering

- Aeronautics

- Medicine and Health

- Alternative Medicine

- Communications and Media

- Advertising

- Communication Strategies

- Public Relations

- Educational Theories

- Teacher's Career

- Chicago/Turabian

- Company Analysis

- Education Theories

- Shakespeare

- Canadian Studies

- Food Safety

- Relation of Global Warming and Extreme Weather Condition

- Movie Review

- Admission Essay

- Annotated Bibliography

- Application Essay

- Article Critique

- Article Review

- Article Writing

- Book Review

- Business Plan

- Business Proposal

- Capstone Project

- Cover Letter

- Creative Essay

- Dissertation

- Dissertation - Abstract

- Dissertation - Conclusion

- Dissertation - Discussion

- Dissertation - Hypothesis

- Dissertation - Introduction

- Dissertation - Literature

- Dissertation - Methodology

- Dissertation - Results

- GCSE Coursework

- Grant Proposal

- Marketing Plan

- Multiple Choice Quiz

- Personal Statement

- Power Point Presentation

- Power Point Presentation With Speaker Notes

- Questionnaire

- Reaction Paper

Research Paper

- Research Proposal

SWOT analysis

- Thesis Paper

- Online Quiz

- Literature Review

- Movie Analysis

- Statistics problem

- Math Problem

- All papers examples

- How It Works

- Money Back Policy

- Terms of Use

- Privacy Policy

- We Are Hiring

School Feeding Project, SWOT Analysis Example

Pages: 6

Words: 1698

Hire a Writer for Custom SWOT analysis

Use 10% Off Discount: "custom10" in 1 Click 👇

You are free to use it as an inspiration or a source for your own work.

The causes of hunger often include: lack of economic opportunity; political disempowerment; income inequality; inadequate public social spending; discrimination based on age, race, and gender; as well as environmental degradation. The solutions often include: sustainable development, including expanded income-earning opportunities for poor people; democratic participation and community empowerment; government programs to assure that everyone meets their basic needs; environmental protection; demilitarization; and policies that promote gender equality, cultural pluralism and social inclusion. It can be argued that international trade and investment can help expand income-earning opportunities for hungry and poor people, but that in order to overcome hunger, governments and civil society need to work actively on other strategies too. Political empowerment of poor people is especially important. The issue of hunger and malnutrition is greatly extended to students in the school systems. (USDA, 2014)

The problem with schools in regards to hunger is that malnutrition has been on the rise in Our School Lunch Program in primary students, while at the same time addressing the issues of declines in school attendance by providing an additional incentive for children to attend school. It should also be noted that feeding children in school will increase their ability to focus and to gain the most out of all other educational programs; therefore, this particular program has the power to render others more effective (Miller Del Rosso, 1999).

The project proposal will focus on how to prevent malnutrition in local communities as well as state school districts, by developing new techniques to farmers, and by helping them to produce more crops in the local communities to stop malnutrition, and support their local schools lunch programs. This project’s long term measures include fostering nutritionally dense agriculture by increasing yields, also ensuring aid to farmers by controlling time and cost in support of helping our local schools.

According to the World Food Program, the accountability and quality of school lunch programs fluctuate in correlations with national levels of income. In countries with low income levels, where the need for school feeding is the highest in regard of hunger and malnourishment, the coverage is the least. In some countries, the cost of feeding a student is greater than the cost of the education itself. (WFP, 2013)

Governments establish the framework within which national economies develop. It is up to governments to establish a stable political, legal and monetary context. Governments shape private sector development through regulations, taxes and subsidies. They provide physical infrastructure such as roads. Governments play a major role in education, health and social welfare. Governments also affect the level of national engagement in globalization. They influence the competitiveness of exports and the relative cost of imports by setting exchange rates. Governments decide how much to protect domestic industries from import com-petition. A government’s fiscal and monetary policies and the provision of physical infrastructure can help attract foreign investment. This project will greatly require Government reform in the school lunch programs due to state and federal policies regarding how students are provided with food. New farming strategies will be put in place that allows a certain amount of farmed foods to be allocated to school lunch programs. (Neuberger, 2013)

Globalization also means that domestic policy decisions can have major international implications and vice versa. The U.S. government’s decision to end the Farmer Owned Reserve — a farm program aimed at stabilizing domestic grain supply and prices — has exacerbated global food price volatility. Liberalized agricultural trade under the North American Free Trade Agreement has undermined livelihood security for both small grain farmers in Mexico and tomato growers in Florida who face competition from cheap imports. (WFP, 2013)

Despite rapid urbanization, agricultural activities still employ 60 percent of the work force in the developing world. Continued investment in agriculture is essential, not only to assure adequate food production for a growing population, but to provide adequate incomes for the majority of the populace. Globalization and commercialization have had mixed results for farmers and farm workers, as for others. The United States is the world’s leading grain exporter, with family-run farms accounting for most of the crops. But family farmers increasingly produce on contract to large agribusiness companies, with the crop, seed variety and input package specified in advance. (USDA, 2014)

Agriculture is the sector of international trade that has the most direct effect on food security. It is the source of both food and livelihood for most poor people. It is essential to sustainable development. Agriculture accounts for a significant part of employment in developing countries and is the largest part of the economy in most poor countries. It is an important source of savings for investment throughout the economy. Developing country agriculture is heavily affected by global trade and agricultural trade rules.

Export zones are common in developing countries, and offer a mixed blessing. The jobs almost always represent gains for workers’ households and the factories can stimulate additional economic activity in such areas as supplies, services and marketing. But the zones encroach on land that could support more traditional sources of livelihood such as fishing and farming. They may force older manufacturing enterprises out of business, although they sometimes provide new business for local enterprises. The zones frequently harm the surrounding environment. Workers in export zones typically work long hours for modest pay under poor or even dangerous conditions. Governments often declare these zones off-limits to labor unions in order to attract investors. (Neuberger, 2013)

Hundreds of millions of children are part of the global work force, some of them as young as 5 or 6. Many work in the informal sector, in domestic service, at home, in the fields. Poverty is a key factor driving children into employment. Many child workers have unemployed or underemployed parents. They often do not have the chance to go to school.

Even when students get all the required calories and protein, they may still suffer from life-threatening conditions because they do not get enough vitamins and minerals. Iodine deficiency disorders, lack of vitamin A and iron-deficiency anemia, often referred to as “hidden hunger,” seriously undermine the health and productivity of poor people. Such “micronutrient” mal-nutrition claims up to 5 percent of national income in some developing countries due to disability and lost lives and productivity. (USDA, 2014)

International trade can be rough on poor people. They can least afford price fluctuations and cannot predict — or sometimes even understand — price changes in global markets. Poor farmers with labor intensive operations may be particularly vulnerable to lower income when more efficient production from developed countries or new technologies drives prices down. (Neuberger, 2013)

In this setting, one option is for developing countries to attempt to become self-sufficient in agricultural production, limiting their imports and setting up food reserves. Self-sufficiency means that farmers produce first and, if necessary, solely for local consumption. Advocates of a self-sufficient strategy, who emphasize the dangers of globalization for weaker states, often fail to recognize the benefits of a global economy. But at the other extreme, a strategy of producing almost solely for export is risky as well. Poor food-importing countries face fluctuating international market prices which they cannot affect or control. A better strategy is food self-reliance, in which countries boost yields, employing sustainable and efficient farming practices, and diversify their agricultural production, some for export and some for domestic consumption. Earnings from exports can help with increased imports when domestic production falls short. India, for example, has moved from a “basket case” dependent on massive external food aid in the 1960s to a net exporter of grain some years during the 1980s and 1990s. It has the potential to become a major rice exporter in the next decade. Expanded grain output in irrigated areas has boosted incomes enormously.

If developing country leaders fail to address inequities or corruption in their own societies, then no trade policy could possibly achieve food security for the students attending school. Developing country leaders must remove any vestiges of practices, such as state-run marketing boards or taxing agricultural exports that shortchange farmers. They must develop agricultural development programs that help farmers adjust to price and production fluctuations. For the long run, agricultural development must be sustainable. Producers must pay attention to soil and water conservation. Sustainable fishing practices are likewise essential. Finally, war obviously and dramatically impinges on food security. In Burundi and Rwanda, as cruel ethnic violence has eased, food production remains below pre-conflict levels, with a third of the respective populations needing food assistance. (WFP, 2013)

People in industrial countries can make trade more responsible by lobbying against laws, policies and practices that discriminate against developing-country exports and for aid programs that encourage sustainable development and food security that feeds the kids in our schools:

- Basic research to improve productivity, especially for peasant and dryland farmers;

- Development assistance to support dissemination of research results, especially that which enhances the role of women in marketing and profiting from their products and encourages sustainable agricultural practices; and

- Technical assistance to developing countries to train local people to process agricultural products in ways to make them acceptable and safe for consumers, thereby encouraging higher value exports.

Grassroots support for responsible trade and sustainable agricultural development can encourage the world’s political leaders to act. People who raise their voices on behalf of those who are hungry can help increase food security within the school systems.