Architecture of Cities

Romanesque Architecture and the Top 15 Romanesque Buildings

Of all the great architectural movements that swept across Europe since antiquity, Romanesque Architecture was the first to emerge after the fall of the Romans. When the Western Roman Empire fell in the 5th century , there was a huge decline in significant building projects for hundreds of years. But at the end of this period now known as the Dark Ages, a new style of architecture emerged. Borrowing heavily from older forms of Roman Buildings, Romanesque Architecture emerged to be the dominant building style in Western Europe, long before the arrival of the Gothic Age .

Definition of Romanesque Architecture

Romanesque architecture and art was a form of design that borrowed extensively from Ancient Roman art and architecture and was used throughout Europe from 500-1200 CE .

Timeline of Romanesque Architecture

Romanesque architecture was the dominant building style in Europe from roughly the point after the fall of the Roman Empire in the 5th century to the beginning of the Gothic Era in the 13 th century .

Developing from religious structures such as churches, monasteries, and abbeys, the Romanesque Style eventually spread into almost all types of buildings. The Dark Ages and Early Middle ages were the major periods that heavily utilized this style.

Romanesque Architecture Characteristics

Rounded Arches or “Roman Arches”

Photo by W. Bulach from Wikimedia Commons

By far, the most dominant feature in Romanesque Architecture is the round arch. Also referred to as the Roman Arch, the round arch predates the pointed Gothic arch. It had already been used in architecture for hundreds of years at the start of the middle ages, most notably in Ancient Roman Architecture. In the photo above you can see the entire west facade of Maria Laach Abbey in Germany is decorated with different forms of the same round arch,

Thick Walls with Small Windows

Photo by Nuno Cardoso from flickr

Overall Romanesque Architecture is full of stout, bulky, heavy, and sturdy-looking buildings. Walls had to be thick with small windows, to take the full weight of the roof above. The entire exterior of Pisa Cathedral shows how even the most monumental and impressive Romanesque buildings were built this way. Later on in architectural history, Flying Buttress allowed architects to build taller buildings with walls full of huge windows – which became the foundation for the Gothic Style .

Barrel Vaults

Photo by Benh Lieu Song from flickr

Earlier in the Romanesque age, the Naves of most churches were capped with wooden roofs. This was a format that dated all the way back to the ancient Roman Basilica. Eventually, the cathedrals of Europe started to get more sophisticated, constructing archways over their naves. Builders would essentially compress multiple stone arches together, to create a barrel vault. Stone barrel vaults also made churches sturdier and helped out with fire protection too, since there were no exposed wooden timbers in the roof to burn. The barrel vault within the Basilica of Saint-Sernin was one of the largest ever constructed in the Romanesque Age.

Lack of Ornamentation and Detail

Photo by Anna & Michal from flickr

Many Romanesque Churches share a distinct lack of ornamentation when compared to churches built in the Gothic Age. Although there are a few exceptions, most Romanesque buildings are stark and bare, and they only have intricate stonework in a few isolated spots. This lack of detail is especially apparent early on in the Romanesque age, before the year 1000 CE . Vézelay Abbey in France was built mostly in the early 1100s , but here you can see some sculptural elements start to appear, particularly in the column capitals.

Romanesque vs. Gothic

Romanesque architecture came before Gothic architecture. The Romanesque period lasted from the 6 th -12 th century , while the Gothic Period lasted from the 13 th -16 th century .

- (left) Rounded arches at Speyer Cathedral in Germany

- (right) Pointed arches at Milan Cathedral in Italy

- Right Photo by © J osé Luiz Bernardes Ribeiro / CC BY-SA 4.0

There are many differences between the two styles. A lot of these differences have to do with European history during the middle ages. Technology was advancing, and people were able to build larger more graceful buildings during the Gothic Period.

New building techniques like the pointed arch and the flying buttress allowed architects to build taller and larger churches. The buttresses allowed the weight of the roof to be spread outward with the help of the pointed arches.

- (left) Side of Pisa Cathedral, with flat walls that have small windows with round arches

- (right) Side of Reims Cathedral, with flying buttresses which allow for huge windows with gothic arches

- Left Photo by Jordiferrer from Wikimedia Commons

So now, instead of having thick stone walls with tiny windows to support your roof, like in a Romanesque building, you could use the buttresses to take the weight of the roof. This allowed architects to use these beautiful massive stained glass windows that would let incredible amounts of light into the interior space.

- (left) The interior of Vézelay Abbey in Vézelay, France. Notice the vaulted ceiling, rounded arches, heavy windows with a lack of natural light, and the lack of excessive detail and artwork.

- (right) The interior of Sainte Chappelle in Paris, France. Notice the ribbed ceiling, the pointed arches, and the massive stained glass windows filled with intricate artwork.

- Left Photo by Jörb Bittner Unna from Wikimedia Commons

- Right Photo by Artmch from Wikimedia Commons

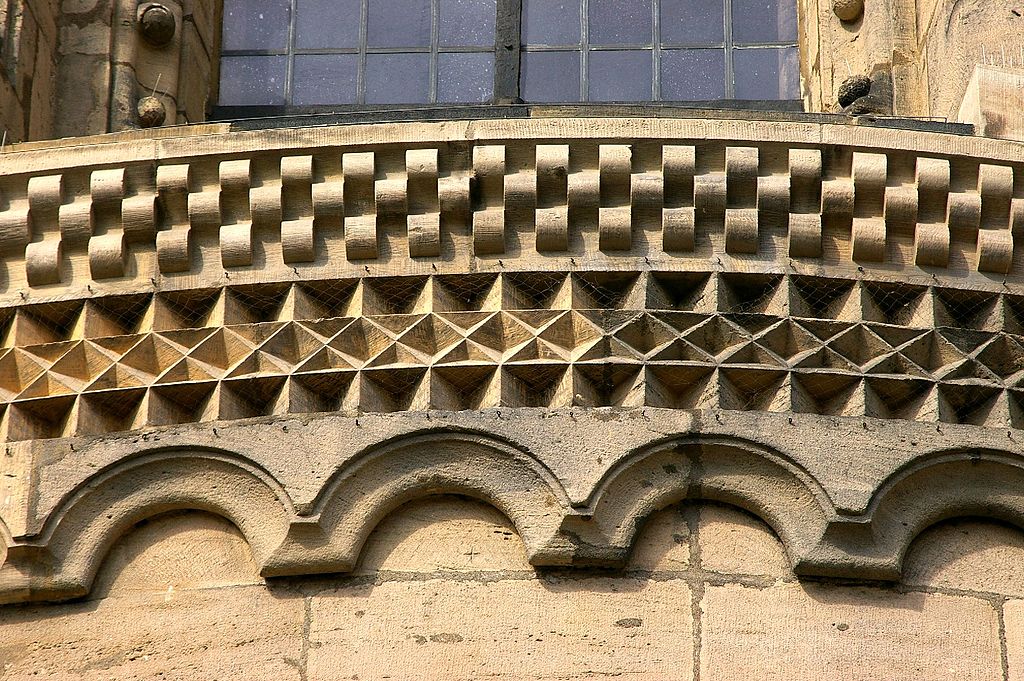

Romanesque architecture also does not include the copious amount of detail that you find in Gothic architecture. Below you will see some simple geometric stonework in a Romanesque church, compared to the elaborate carvings in a Gothic building.

- (left) Romanesque detailing at Bamberg Cathedral in Bramber, Germany

- (right) Late Gothic detailing at the Colegio de San Gregoria in Valladolid, Spain

- Left Photo by Reinhard Kirchner from Wikimedia Commons

- Right Photo by Rafael Tello from Wikimedia Commons

Again, the discrepancies in the detailing had a lot to do with European history. Religious authorities in the middle ages were often opposed to excessive art and details, as they were thought to distract from the services of the church. But eventually, these practices were slowly abandoned, and art was made more openly, so long as it told the message of the church and the bible.

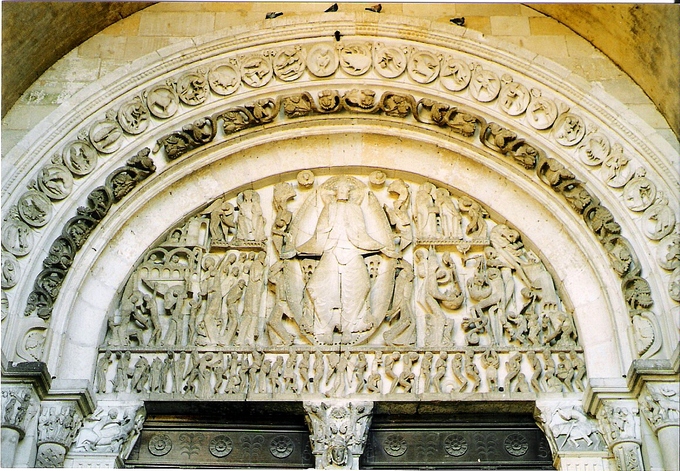

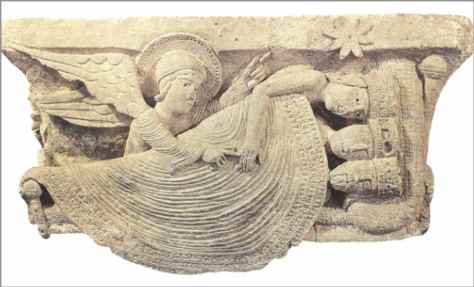

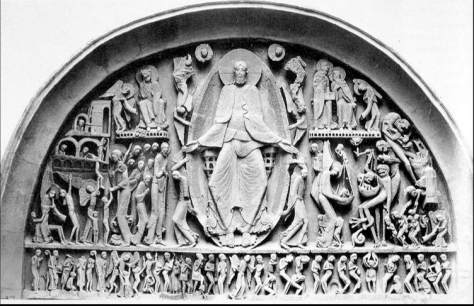

It’s scaled back, but in Romanesque architecture, you can see fine details and carved stonework. You will find stories from the bible, depicted mostly around column capitals and within the Tympanum, the main archway above the entrance to a church. Gothic architecture took this a step further and showed even more intricate depictions of various religious motifs.

- (left) Tympanum at Vézelay Abbey in Vézelay, France

- (right) Tympanum at Notre Dame in Paris, France

- Both carvings depict the scene of the last judgment, however, the Gothic version is much more intricate and detailed, with significant improvement in the realism of the sculpture. The carvings also leave the area of the Tympanum and cascade down and around the doorway and into the rest of the building.

- Left Photo by Gerd Eichmann from Wikimedia Commons

- Right Photo by Guilhem Vellut from Wikimedia Commons

Interested in Romanesque Architecture? Check out some of our other related articles!

What are the Best Romanesque Buildings?

Below is a list of buildings that are often regarded as the best examples of Romanesque architecture. These buildings show all of the key features of the Romanesque style.

Rather than just focusing on churches, this list will also incorporate secular buildings as well to give a cohesive look at Romanesque Architecture. This list will focus on size, innovation, and overall beauty to determine what are the best Romanesque buildings that can still be found in Europe today.

1. Pisa Cathedral – Pisa, Tuscany, Italy

Pisa Cathedral may be known for its leaning tower, but it’s also one of the greatest examples of Romanesque Architecture on earth. The cathedral, baptistery , and bell tower are all built with white marble. The front elevation shows many of the standard elements of Romanesque architecture, with dozens of round arches surrounded by geometric stonework. Although the church’s exterior has a lot of windows, all of them are small and they don’t provide a lot of natural light. The walls of Pisa Cathedral are the only thing supporting the roof above, and that’s why they had to be built thick and sturdy, with just small openings for windows.

The interior of Pisa Cathedral shows a blend of a few different styles. The arches and columns you see are all romanesque, and they date from the original construction of the cathedral which took place from 1063-1092 . But the golden-detailing you see in the coffered ceiling was added later on, during the 17th century . Today the leaning tower of Pisa and Pisa Cathedral bring in millions of visitors every year, and they are listed as UNESCO World Heritage Sites .

2. Cathedral of Monreale – Monreale, Sicily, Italy

Much like other churches in Sicily, the Cathedral of Monreale was constructed by the Normans . Its located just outside of the Sicilian capital Palermo and is regarded as one of the greatest churches on the island. Construction began in 1172 and most of the architecture is Norman, although various additions were added in other styles. The church is famous for its Byzantine Mosaics . The church is part of a large grouping of UNESCO Listed sites found throughout the area around Palermo.

The church is famous for its Byzantine Mosaics . These mosaics cost the Normans vast amounts of wealth to build. Not only were the tiles made with fragments of real gold, but the mosaics themselves were also painstakingly assembled by Byzantine Craftsmen, some of whom traveled all the way from the Eastern Mediterranean lands of the Byzantine Empire.

3. San Miniato al Monte – Florenc e , Tuscany, Italy

Just like Pisa Cathedral, San Miniato al Monte is an incredible Romanesque Church, located in the Italian Region of Tuscany. Work started in the church back in 1013 , and today it looks largely the same way it did back in the 11th century . The exterior is richly decorated with white and green marble, in a color scheme similar to that of Florence Cathedral, although the cathedral was built centuries later.

The interior of the church features more intricate stonework, with colored marble to match the exterior. The church also features a wooden roof, which was the main material used for the roofs of early Romanesque buildings. The beams and joists are all richly decorated with painted geometric designs. Although San Miniato al Monte is one of the smaller churches in Florence , it’s still an incredible work of Romanesque Architecture in a city mostly known for its Renaissance buildings.

4. Speyer Cathedral – Speyer, Rhinlenad-Palatinate, Germany

Speyer Cathedral is a Romanesque Cathedral located in southwestern Germany. Construction on the cathedral began in 1030 , and the exterior is built with a distinct red sandstone. Most of the church is from the later stages of the Romanesque age, but the Narthex and the front facade of the were both added in the 19th century . The work was done in a Neo-Romanesque fashion, which gives the church a pretty cohesive appearance.

The interior of the Speyer Cathedral features one of the tallest naves from the Romanesque Age. The church also features a Barrel Vault, which was an important innovation in Romanesque Architecture, which evolved into the Gothic Ribbed Vault. Speyer Cathedral and the city of Speyer itself were both repeatedly involved in the conflict of the 30 Years’ War , but despite these turbulent times, the church is still remarkably preserved considering its incredible age.

Like Architecture of Cities? Sign up for our mailing list to get updates on our latest articles and other information related to Architectural History.

5. Basilica of Saint-Sernin – Toulouse, Occitanie, France

While Speyer Cathedral in Germany may be the largest Romanesque cathedral in the world, the title of the largest Romanesque building in the world goes to the Basilica of Saint-Sernin in France. The church was constructed from 1080-1120 and was originally part of a much larger abbey. The interior features a vaulted roof made of stone, which was a huge technological achievement over the flat wooden ceilings you will find on many other Romanesque buildings. Additionally, the stone vault was a huge leap forward in fire protection.

6. Trier Cathedral – Trier, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

Trier Cathedral stands on the foundation of several Roman buildings that were built in the 4 th century CE . The majority of the church that is seen today dates from the 11 th century from 1016-1041 . The church is famous for its several towers which were often replicated in other Romanesque buildings throughout Europe.

7. Maria Laach Abbey – Andernach, Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany

Abbeys and Monasteries were some of the wealthiest and most powerful establishments of the middle ages. All of that wealth and power often resulted in fantastic architecture. Maria Laach Abbey in Germany is one of the most cohesive examples of Romanesque Architecture in Europe. The exterior is particularly void of other building styles, unlike other churches on this list.

8. Ca’ Loredan and Ca’ Farsetti – Venice , Veneto, Italy

During the chaos and instability that followed the collapse of the Roman Empire, a group of refugees began a small settlement in the Venetian Lagoon. By the early middle ages, their settlement grew into one of the most powerful cities in all of Europe, Venice . Venice was the capital of the mighty Republic of Venice , a maritime republic that controlled most of the trade in the Adriatic and Mediterranean Seas. The Ca’ Loredan and Ca’ Farsetti, are two incredible works of Romanesque architecture that were financed by this impressive trade network. They are located right next to one another overlooking the Grand Canal in Venice.

9. Church of the Holy Sepulchre – Jerusalem, Jerusalem, Israel

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre has a long and complicated history, stretching from the time of the Roman Empire all the way until today. Much of the church is built in a distinct Romanesque Style and dates from the 12 th -13 th century . The Crusaders , who took the city of Jerusalem in the year 1099 , renovated and added to the church giving it its distinct Romanesque appearance.

10. Lund Cathedral – Lund, Scania, Sweden

Lund Cathedral is the only Romanesque building on this list located in Scandinavia. The church was built in the early 12 th century and remains one of the oldest stone buildings in all of Sweden. At the time it was built, Lund was ruled by Denmark so it can technically be seen as a work of Danish Romanesque Architecture.

Interested in the Romanesque Architectural Style? Check out some of our related articles!

11. Cefalù Cathedral – Cefalù, Sicily, Italy

The Normans, which also controlled parts of modern-day France and England, conquered Sicily and southern Italy in the early middle ages. They created important works of Norman architecture there, which is a subcategory within Romanesque architecture. Not only was the church built as a place of worship, but the architects also designed it as a fortification to help defend the town from invaders. Today, Cefalù Cathedral is the most notable landmark in the city of Cefalù and is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site .

12. Parma Cathedral – Parma, Emilia-Romagna, Italy

Another incredible Romanesque church is Parma Cathedral in Italy. Begun in 1059 , the cathedral contains a separate baptistery, church, and bell tower. This was a similar design to many other churches in Italy. The baptisteries, in particular, were kept separate because no one was allowed to enter the church until after their baptism.

13. Vézelay Abbey – Vézelay, Burgundy, France

The Vézelay Abbey was constructed over a 30 year period from 1120 to 1150 . One of the more ornamental churches on this list, the front elevation features multiple stone statues and sculptures. Traditionally, Romanesque buildings only had sculptures in the portal of the church. (the part directly over the main entrance, also known as the Tympanum) But Vézelay Abbey is known for having additional details throughout.

1 4. Aachen Cathedral – Aachen, North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany

Aachen Cathedral is one of the greatest Romanesque Cathedrals on this list. The building was built by the great Charlemagne. Charlemagne is regarded as the most influential ruler of the early middle ages. He was able to create a massive empire that stretched through modern-day France, Germany, and Italy. Charlemagne often ruled from Aachen and was responsible for a large portion of Aachen Cathedral.

1 5. Tower of London – London, England, United Kingdom

William the conqueror was the Duke of Normandy during the early 11 th century . He gained his nickname after he crossed the English Channel and defeated the previous ruler of England to become the first Norman King of England. To help maintain control of his new kingdom, William began construction on the Tower of London. Overlooking the Thames River in London, the building is a great example of a Romanesque style fortification.

Romanesque Architecture Today

Although not as popular as it was at the end of the 19th century , Romanesque Architecture still lives on today in the form of the Romanesque Revival Style . A great example of a Neo Romanesque building is the Fisherman’s Bastion located in Budapest, Hungary .

During the early 19th century , the Neo-Classical style became extremely popular. It was utilized by several world powers to construct important government buildings that recalled the power and strength of the Ancient Roman government system.

Ironically, just as Romanesque architecture evolved from the architecture of the Roman Empire, Neo-Romanesque became quite popular in the aftermath of the golden age of Neo-Classical architecture .

Richardsonian Romanesque

Richardsonian Romanesque is a term coined to describe the distinct Romanesque Revival buildings of H.H. Richardson and other American Architects in the late 19th century . Some of the most notable works are Trinity Church in Boston as well as the Winn Memorial Library in Woburn Massachusetts.

Although much different thanks to new technologies in masonry construction, Richardsonian Romanesque utilizes many of the distinct principles of Romanesque architecture. The heavy and bulky forms, paired with the rounded arches greatly resemble the Romanesque buildings that were popular in Europe during the middle ages.

Romanesque Architecture’s Legacy

Architecture as a whole was greatly influenced by the Romanesque style. Romanesque architecture represents a clear link to the architecture of the Roman Empire and Gothic Architecture.

So many of Europe’s greatest cathedrals were built in the Gothic style , and all of the innovations that made those buildings possible were learned during the Romanesque period.

- About the Author

- Rob Carney, the founder and lead writer for Architecture of Cities has been studying the history of architecture for over 15 years.

- He is an avid traveler and photographer, and he is passionate about buildings and building history.

- Rob has a B.S. and a Master’s degree in Architecture and has worked as an architect and engineer in the Boston area for 10 years.

Related Posts:

A beginner’s guide to Romanesque architecture

The name gives it away—Romanesque architecture is based on Roman architectural elements. It is the rounded Roman arch that is the literal basis for structures built in this style.

Ancient Roman ruins (with arches)

All through the regions that were part of the ancient Roman Empire are ruins of Roman aqueducts and buildings, most of them exhibiting arches as part of the architecture (you may make the etymological leap that the two words—arch and architecture—are related, but the Oxford English Dictionary shows arch as coming from Latin arcus , which defines the shape, while arch—as in architect, archbishop, and archenemy—comes from Greek arkhos , meaning chief and ekton means builder).

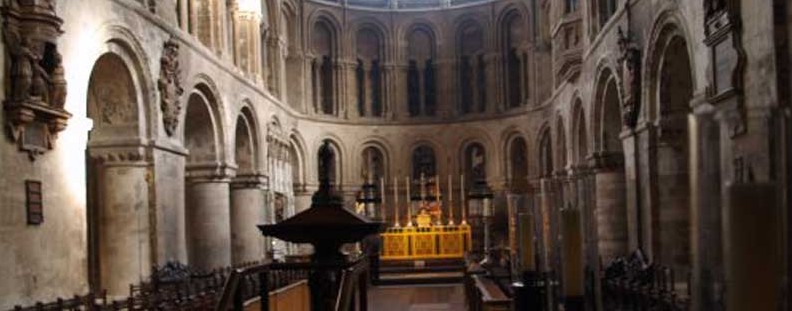

Interior of the Palatine Chapel of Charlemagne, Aachen, Germany, 792–805 (photo: Velvet , CC BY-SA 3.0)

When Charlemagne was crowned Holy Roman Emperor in 800 C.E., the remains of Roman civilization were seen all over the continent, and legends of the great empire would have been passed down through generations after the fall of Rome in the fifth century. So when Charlemagne wanted to unite his empire and validate his reign, he began building churches in the Roman style—particularly the style of Christian Rome in the days of Constantine, the first Christian Roman emperor.

After a gap of around two hundred years with no large building projects, the architects of Charlemagne’s day looked to the arched, or arcaded, system seen in Christian Roman edifices as a model. It is a logical system of stresses and buttressing, which was fairly easily engineered for large structures, and it began to be used in gatehouses, chapels, and churches in Europe.

Gloucester Cathedral, begun 1089 (photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

These early examples may be referred to as pre-Romanesque because, after a brief spurt of growth, the development of architecture again lapsed. As a body of knowledge was eventually re-developed, buildings became larger and more imposing. Examples of Romanesque cathedrals from the early Middle Ages (roughly 1000–1200) are solid, massive, impressive churches that are often still the largest structure in many towns.

In Britain, the Romanesque style became known as “Norman” because the major building scheme in the 11th and 12th centuries was instigated by William the Conqueror, who invaded Britain in 1066 from Normandy in northern France. (The Normans were the descendants of Norse, or north men (“Vikings”) who had invaded this area over a century earlier.) Durham and Gloucester Cathedrals and Southwell Minster are excellent examples of churches in the Norman, or Romanesque style.

Gloucester Cathedral, nave, begun 1089 (ceiling later) (photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The arches that define the naves of these churches are well modulated and geometrically logical—with one look you can see the repeating shapes, and proportions that make sense for an immense and weighty structure. There is a large arcade on the ground level made up of bulky piers or columns. The piers may have been filled with rubble rather than being solid, carved stone. Above this arcade is a second level of smaller arches, often in pairs with a column between the two. The next higher level was again proportionately smaller, creating a rational diminution of structural elements as the mass of the building is reduced.

Gloucester Cathedral, decorative carving on the nave arcade and triforium (photo: Steven Zucker , CC BY-NC-SA 2.0)

The decoration is often quite simple, using geometric shapes rather than floral or curvilinear patterns. Common shapes used include diapers—squares or lozenges—and chevrons, which were zigzag patterns and shapes. Plain circles were also used, which echoed the half-circle shape of the ubiquitous arches.

Early Romanesque ceilings and roofs were often made of wood, as if the architects had not quite understood how to span the two sides of the building using stone, which created outward thrust and stresses on the side walls. This development, of course, didn’t take long to manifest, and led from barrel vaulting (simple, semicircular roof vaults) to cross vaulting, which became ever more adventurous and ornate in the Gothic .

Additional resources

Romanesque architecture from the Durham World Heritage site.

Corpus of Romanesque sculpture in Britain and Ireland.

Smarthistory images for teaching and learning:

[flickr_tags user_id=”82032880@N00″ tags=”romanesque,”]

More Smarthistory images…

Cite this page

Your donations help make art history free and accessible to everyone!

Romanesque Architecture and Art

Summary of Romanesque Architecture and Art

Capturing the aspirations of a new age, Romanesque art and architecture started a revolution in building, architectural decoration, and visual storytelling. Starting in the latter part of the 10 th century through the 12 th , Europe experienced relative political stability, economic growth, and more prosperity during this time and coupled with the increasing number of monastic centers as well as the rise of universities, a new environment for art and architecture that was not commissioned solely by emperors and nobles was born. With the use of rounded arches, massive walls, piers, and barrel and rib vaults, the Romanesque period saw a revival of large-scale architecture that was almost fortress-like in appearance in addition to a new interest in expressive human forms. With the Roman Church as the main patron, Romanesque metalwork, stonework, and illuminated manuscripts spread across Europe, from the Mediterranean to Scandinavia, creating an international style that was adapted to regional needs and influences. 19 th -century art historians who coined the term Romanesque thought the weighty stone architecture and the stylized depiction of the human form did not live up to the standards of the classical ideas of humanism (manifested later and powerfully in Renaissance Humanism ), but we now recognize that Romanesque art and architecture innovatively combined Classical influences, seen in the Roman ruins scattered throughout the European countryside and in Byzantine illuminated manuscripts and mosaics, with the decorative and more abstract styles of earlier Northern tribes to create the foundation of Western Christian architecture for centuries to come. While an immediate precursor to the Gothic style, the Romanesque would see revivals in the 17 th and 19 th centuries, as architects (masons) came to appreciate the clarity and formidable nature of the Romanesque façade when applied across a range of buildings, from department stores to university buildings.

Key Ideas & Accomplishments

- Along with the new political and economic security, the spread of the Roman Church and the codification of rituals and liturgy encouraged the faithful to undertake pilgrimages, traveling from church to church, honoring martyrs and relics at each stop. The economic boon of such travel to cities led to rapid architectural developments, in which cities vied for grander and grander churches. Lofty stone vaulting replaced wooden roofs, main church entrances became more monumental, and decorative architectural sculpture flourished on the façades of the churches.

- While many churches continued to use barrel vaulting, during the Romanesque period, architects developed the ribbed vault, which allowed vaults to be lighter and higher, thus allowing for more windows on the upper level of the structure. The ribbed vault would be more fully developed and utilized during the subsequent Gothic period, but important early examples in the 11 th century set the precedent.

- During the Romanesque period, the use of visual iconography for didactic purposes became prevalent. As most people outside of the monastic orders were illiterate, complex religious scenes were used to guide and teach the faithful of Christian doctrine. Architects developed the use of the tympanum, the arched area above the doors of the church, to show scenes such as the Last Judgment to set the mood upon entering the church, and other biblical stories, saints, and prophets decorated interior and exterior doors, walls, and, capitals to shepherd the worshippers' prayers.

Artworks and Artists of Romanesque Architecture and Art

Church of Sainte-Foy

This pilgrimage church, the center of a thriving monastery, exemplifies the Romanesque style. Two symmetrical towers frame the west façade, their stone walls supported by protruding piers that heighten the vertical effect. A rounded arch with a triangular tablature frames the portal, where a large tympanum of the Last Judgment of Christ is placed, thus greeting the pilgrim with an admonition and warning. The grandeur of the portal is heightened by the two round, blind arches on either side and by the upper level arch with its oculus above two windows. The façade conveys a feeling of strength and solidity, its power heightened by the simplicity of decorative elements. It should be noted that this apparent simplicity is the consequence of time, as originally the tympanum scene was richly painted and would have created a vivid effect drawing the eye toward the entrance. The interior of the church was similarly painted, the capitals of the interior columns carved with various Biblical symbols and scenes from Saint Foy's life, creating both an otherworldly effect and fulfilling a didactic purpose. Saint Foy, or Saint Faith, was a girl from Aquitaine who was martyred around 287-303, and the church held a gold and jeweled reliquary, containing her remains. The monks from the Abbey stole the reliquary from a nearby abbey to ensure their church's place on the pilgrimage route. Over time, other relics were added, including the arm of St. George the Dragon Slayer, and a gold "A" believed to have been created for Charlemagne. The construction of the church was undertaken around 1050 to accommodate the crowds, drawn by reports of various miracles. The church was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1998 for its importance on the pilgrim route and also as a noted example of early Romanesque architecture.

Stone, wood - Conques, France

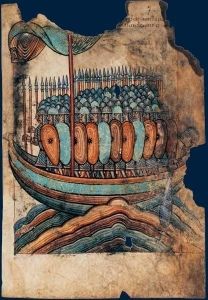

A scene from the Bayeux Tapestry

This scene from the famous tapestry shows Odo, Bishop of Bayeux, carrying an oak club while riding on a black horse, as he rallies the Norman forces of Duke William, his half-brother, against the English at the Battle of Hastings in 1066. Careful attention is given to the tack of the horses, the details of the men's helmets and uniforms, while the overlay of plunging horses, their curving haunches and legs, creates a momentum that carries the narrative onward into the next scene. In the lower border, a horse is falling, while its rider, pierced with a long spear collapses on the right. At both corners, other fallen soldiers are partially visible, and convey the terrible effects of battle, while the charge to victory gallops on above them. As art critic Jonathan Jones noted, "The Bayeux tapestry is not just a fascinating document of a decisive battle in British history. It is one of the richest, strangest, most immediate and unexpectedly subtle depictions of war that was ever created." The tapestry, about 230 feet long and 21 inches tall, is a sustained narrative of the historical events that, beginning in 1064 lead up to the battle, which ended in the Norman conquest of England and the rule of William the Conqueror, as he came to be known. The upper and lower borders, each 2-¾ inches wide, shown in this sample, continue throughout the tapestry, as does the use of a Latin inscription identifying each scene. The images in the borders change, echoing the narrative, as during the battle the pairs of fantastical animals in the lower border is replaced by the images seen here of fallen soldiers and horses. Similarly when the invasion fleet sets sail, the borders disappear altogether to create the effect of the vast horizon. The borders also include occasional depictions of fables, such as "The Wolf and a Crane" in which a wolf that has a bone caught in its throat is saved by a crane that extracts it with its long beak, which may be a subversive or admonitory comment upon the contemporary events. Though called a tapestry, the work is actually embroidered, employing ten different colors of dyed crewel, or wool yarn and is believed to have been made by English women, whose needlework, known as Opus Anglicanum , or English work, was esteemed throughout Europe by the elite. The Bayeux Tapestry was a unique work of the Romanesque period, as it depicted a secular, historical event, but also did so in the medium that allowed for an extended narrative that shaped both the British and French sense of national identity. As art historian Simon Schama wrote, "It's a fantastic example of the making of history." The work, held in France, was influential later in the development of tapestry workshops in Belgium and Northern France around 1500 and the Gobelin Tapestry of the Baroque era.

Linen, crewel - Bayeux Museum, Bayeux, France

Duomo di Pisa

The entrance to Pisa Cathedral, made of light-colored local stone, has three symmetrically arranged portals, the center portal being the largest, with four blind arcades echoing their effect. The round arches above the portal and the arcades create a unifying effect, as do the columns that frame each entrance. The building is an example of what has been called Pisa Romanesque, as it synthesizes elements of Lombard Romanesque, Byzantine, and Islamic architecture. Lombard bands of colored stone frame the columns and arches and extend horizontally. Above the doors, paintings depicting the Virgin Mary draw upon Byzantine art, and at the top of the seven round arches, diamond and circular shapes in geometric patterns of colored stone echo Islamic motifs. The upper levels of the building are symmetrically arranged in bands of blind arcades and innovatively employ small columns that convey an effect of refinement. The name of two architects, Buscheto, and Rainaldo, were inscribed in the church, though little is known of them, except for this project. Buscheto was the initial designer of the square that, along with the Cathedral, included the famous leaning Tower of Pisa, done in the same Romanesque style, visible here in the background, and the Baptistery. Following his death, Rainaldo expanded the cathedral in the 1100's, of whom his inscription read, "Rainaldo, the skilful workman and master builder, executed this wonderful, costly work, and did so with amazing skill and ingenuity." Dedicated to the Assumption of the Virgin Mary, the church was consecrated in 1118 by Pope Gelasius II. The church's construction was informed by the political and cultural era, as it was meant to rival St. Mark's Basilica then being reconstructed in Venice, a competing maritime city-state. The building was financed by the spoils of war, from Pisa's defeat of Muslim forces in Sicily, and it was built outside of the walls to show that the city had nothing to fear. The Pisa plaza became a symbol of the city itself, as shown by the famous Italian writer Gabriele D'Annunzio calling the square, "prato dei Miracoli," or "meadow of miracles" in 1910, so the plaza has been known since as the "Field of Miracles."

Masonry, marble - Pisa, Italy

The Temptation of Eve

Artist: Giselbertus

This relief sculpture shows an almost life-sized nude Eve, presumably reclining toward Adam (now lost) as if whispering to him seductively, while her left hand reaches back to grasp an apple from the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil. The composition emphasizes sinuous line and serpentine form. The tree intersects vertically with her body, covering her pubic area, and the serpent in the foliage at the right echoes both the tree and the depiction of Eve herself. The work is famously the only large-scale nude of the medieval period, an era when Christian values discouraged the study of the naked human body. With this depiction, Giselbertus pioneered the rendering of Adam and Eve in the nude, a treatment that became a tradition in Christian art, as their nakedness was connected to their fall into sin. Originally Eve was paired with a nude Adam reclining on her left, and both figures were placed on the lintel over the portal. Above the lintel, Giselbertus also created the tympanum that depicted the Last Judgment, with Christ enthroned presiding over the saved and the damned and with attendant angels and devils. The viewers, who were largely illiterate, would have understood the didactic visualization that connected the Temptation, by which sin entered the world, and the scene of ultimate redemption. Giselbertus was trained by the master of Cluny around 1115 and was influenced by the cathedral reliefs that emphasized Christ's compassion. He worked at Autun from about 1125-1135, sculpting most of church's decorative elements. Unusually for the time, Giselbertus included in the tympanum, under Christ's feet, a Latin inscription reading, "Gislebertus made this." Most scholars have taken this for the sculptor's name, though some have suggested it may refer to the patron who commissioned the work. His work was innovative for the feeling conveyed by his stylized human figures and influenced contemporaneous Romanesque, and later Gothic, sculptors. However, by the late 1700s, due to a rising conservatism in religious and artistic thought, his work was thought to be both too primitive and licentious. Eve disappeared in 1769 when it was used as building material for a local house, and his Last Judgment tympanum was completely filled with plaster, which by a stroke of luck saved it from destruction during the French Revolution. Both Eve and the tympanum were rediscovered and restored only in the 1830s when the Romantic movement revived an appreciation of medieval art.

Stone - Musée Rolin, Autun, France

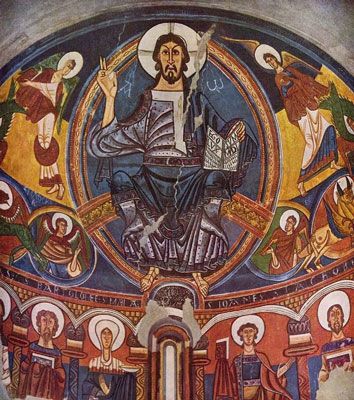

Christ Pantocrator

Artist: Master of Taüll

This vivid fresco shows Christ the Pantocrator (ruler of the universe), framed by a mandorla, or body halo, bordered in red, gold, and blue. Sitting on a throne, he faces the viewer with an intense gaze, while holding a book that reads in Latin "I am the light of the world," as his uplifted right hand makes the traditional symbol of blessing and teaching. Alpha and Omega symbols float above his shoulders, while two angels flank him, their long curved forms echoing the lines of the mandorla and drawing the focus to his haloed head. The greater scale of his figure, reflecting a Byzantine influence, is meant to emphasize his importance. The four Evangelists, Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John, are depicted in a band of circles at his feet and turn to face him, gesturing. The work's innovative sense of composition, with its curving bands of blue, gold, and carmine, emphasize the semi-circular apse and focus on Christ in the center. The use of varying shades of blue to depict him, along with highlights of white and carmine dots, create a sense of movement as if he were emerging toward the faithful. Below him a number of other sacred figures are partially visible, including the Virgin Mary left of center, as she holds a chalice containing Christ's blood, a pioneering representation of the Holy Grail and indication of the cult of Mary that was developing at the time. Originally, the fresco covered the apse of the church of Sant Climent de Taüll in Vall de Boi in Catalonia. Consecrated in 1123, the basilica, with three naves and a Byzantine influenced seven-story bell tower, was known for its exceptional interior murals, all considered to be the work of the Master of Taüll, about whom little else is known. Over time, many of the murals were damaged but those remaining, including this one, were transferred to canvas for exhibition at the National Art Museum of Catalonia. This fresco influenced a number of 20 th century Spanish artists, including Francis Picabia and Pablo Picasso, who kept a poster of it in his studio.

Fresco - Museu Nacional d'Art de Catalunya, Barcelona, Spain

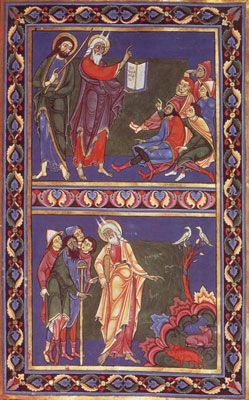

Moses Expounding the Law

Artist: Master Hugo

This page from an illuminated manuscript shows two scenes in which Moses, depicted with a halo and horns, explains the law to the Israelites. In the upper scene, Moses stands, left of center, explaining the Ten Commandments, as he lifts his hand in a gesture of teaching and blessing toward the small group, seated on the ground and listening attentively. In the lower scene, he addresses a group of four men as he explains the dietary laws of the Jewish faith by pointing to a sheep which can be eaten and a pig which cannot. Two doves, representing the peace obtained from following God's law, face one another at the top of a tree on the right. Overall, the work has a calm but vital stylistic flow, derived from the curving lines and the blue, red, green, and gold palette that is echoed in the patterned borders. Master Hugo pioneered this style, which came to be called "damp fold," as clothing was painted as if damp to create both a sense of movement and a more realistic human form. Master Hugo was the first named artist in England, and he worked at Bury St. Edmund's Abbey, where he made this Bible for the Abbey around 1135. The Bible contains various paintings on full and half pages and decorative initials, which as art historian Thomas Arnold wrote, "have led to a general acknowledgement of Master Hugo as the gifted innovator of the main line of English Romanesque art." He is also credited with making the bronze doors of the Abbey church's western façade and two carved crucifixes, including the famous Cloisters Cross (c. 1150-1160).

Ink and tempera on vellum - Parker Library, Corpus Christi College, Cambridge

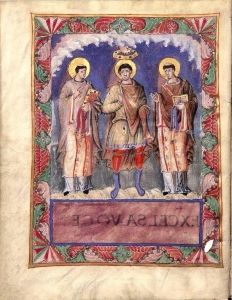

The Shrine of the Magi

Artist: Nicholas of Verdun

Nicholas of Verdun deliberately designed reliquary, believed to contain relics of the Magi who journeyed to the Nativity of Christ, to resemble the façade of a basilica. Christ in Majesty is depicted enthroned in the upper section, his right hand raised in blessing, his left holding the Gospel, as two apostles flank him. On the lower level, the Three Kings bearing gifts, kneel on the left, facing toward the Madonna and Child enthroned in the center. On the lower right, Christ's baptism is depicted.The figurative treatment is both realistic, as shown in the different poses of the Kings conveying movement, and refined, with its fine details and flowing draperies. This three level reliquary, also known as The Shrine of the Three Kings, is a masterpiece of Mosan metalworking, with its silver and gold overlay, filigree, and enamel work. The apostles are depicted on the horizontal sides of the shrine, not visible here, and overall the work contains 74 figures in vermeil, or silver relief. Viewed from the side, the shrine resembles a basilica, with small pairs of lapis lazuli columns standing at the corners and between each of apostles. Following the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick Barbarossa's gift of the relics to Rainald of Dassel, the Archbishop of Cologne, the archbishop commissioned the shrine from Nicholas of Verdun and his workshop around 1180. The relics were of such religious importance, and the shrine considered such a masterpiece, that in 1248 construction of a new Cologne Cathedral was undertaken to suitably house the reliquary. The shrine was placed in the crossing, marking the high point of the church. As art historian Dr. Rolf Lauer wrote, "The Shrine of the Magi is the largest, most artistically significant, and, in terms of its content, most ambitious reliquary of the Middle Ages."

Gold, silver, filigree, precious stones, wood - Cologne Cathedral, Cologne Germany

Beginnings of Romanesque Architecture and Art

Vikings and insular art.

The many Viking invasions of Europe and the British Isles marked the era before the Romanesque period. Beginning in 790 with raids on Irish coastal monasteries, the raids became full-scale military excursions within a century as shown by the Sack of Paris in 845 and the Sack of Constantinople in 860. For the next two hundred years, the Vikings raided and sometimes conquered surrounding areas. With the conversion of the Vikings to Christianity, the era ended around 1066 when the Normans, themselves descended from Vikings, conquered England.

With the conversion to Christianity of the British Isles and Ireland, following from the mission of St. Augustine in 597, monasteries in Hibernia (present-day Ireland) and present-day Britain played a primary role in cultural continuity throughout Europe, developing the Insular, or Hiberno-Saxon, style that incorporated the curvilinear and interlocking ornamentation of Viking and Anglo-Saxon cultures with the painting and manuscript examples sent from the Roman church.

Stone crosses and portable artifacts such as metalwork and elaborate gospel manuscripts dominated the period. Masterpieces like the British Book of Durrow (c. 650) and the Irish Book of Kells (c. 800), created by monks, included extensive illustrations of Biblical passages, portraits of saints, and elaborately decorative carpet pages that preceded the beginning of each gospel. Insular art influenced both Romanesque manuscript illumination and the richly colored interiors and architectural decorative elements of Romanesque churches.

The Carolingian Renaissance

King of the Franks in 768 and King of the Lombards in 774, Charlemagne became Holy Roman Emperor in 800, effectively consolidating his rule of Europe. He strove to position his kingdom as a revival of the, now Christian, Roman Empire. Charlemagne was an active patron of the arts and launched a building campaign to emulate the artistic grandeur of Rome. Drawing from the Latin version of his name (Carolus), the era is known as the "Carolingian Renaissance." As art historian John Contreni wrote, his reign "saw the construction of 27 new cathedrals, 417 monasteries, and 100 royal residences." His palace complex in Aachen (c. 800) that included his Palatine Chapel modeled on the Byzantine St. Vitale (6 th century) became a model for subsequent architecture.

While Carolingian architecture drew on earlier Roman and Byzantine styles, it also transformed church façades that would have consequential effects throughout the Middle Ages. Emphasizing the western entrance to the basilica, the westwork was a monumental addition to the church, with two towers and multiple stories, that served as a royal chapel and viewing room for the emperor when he visited.

Carolingian murals and illuminated manuscripts continued to look to earlier Roman models and depicted the human figure more realistically than the earlier Hiberno-Saxon illuminators. This (early) naturalism had a lasting influence on Romanesque and Gothic art.

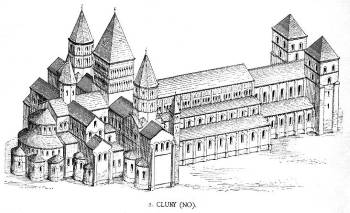

Cluny Abbey

In the early 900s, concern began to grow about the economic and political control that nobles and the emperor exercised over monasteries. With rising taxes imposed by nobles and the installation of relatives as abbots, the Cluny Abbey sought monastic reform, based upon the Rule of St. Benedict (c. 480-550), written by the 5 th -century St. Benedict of Nursia, that emphasized peace, work, prayer, study, and the autonomy of religious communities.

In 910, William of Aquitaine donated his hunting lodge and surrounding lands to found Cluny Abbey and nominated Berno as its first Abbott. William stipulated the independence of the Abbey from all secular and local authority, including his own. As a result, the Abbey was answerable only to the authority of the Pope and quickly became the leader of the Benedictine order, establishing dozens of monasteries throughout France. As part of its emphasis on prayer and study, the Abbey also created a rich liturgy, in which art played an important role.

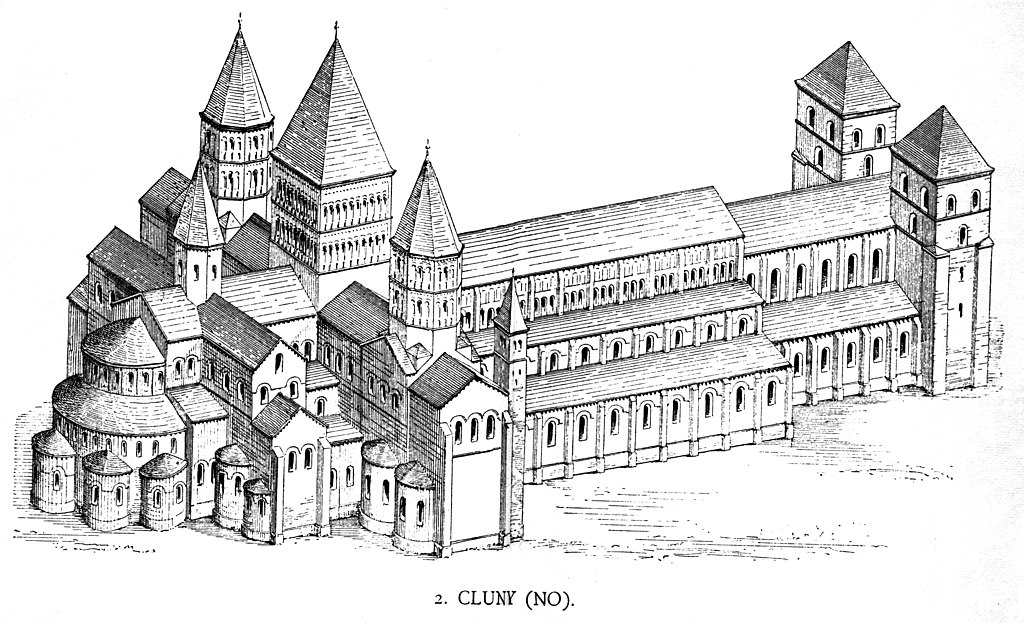

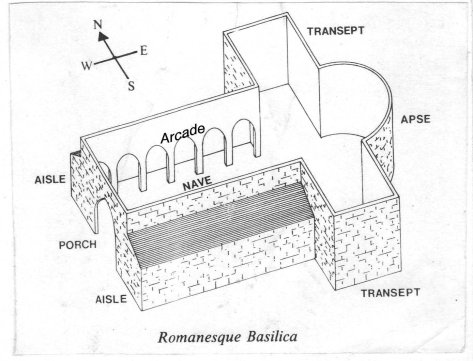

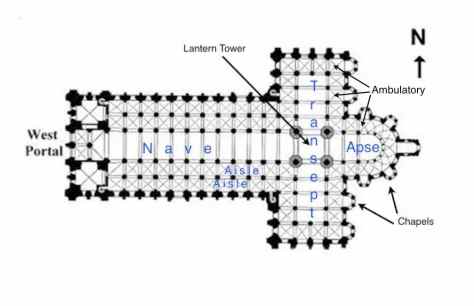

Between the 10 th and the early 12 th centuries, three churches were built at Cluny, each larger than the last, and influencing architectural design throughout Europe. Not much is known of Cluny I, but it was a small, barnlike structure. After a few decades, the monastery outgrew the small church, and Cluny II (c.955-981) was erected. Based on the old basilica model, Cluny II employed round arches and barrel vaults and used small upper level windows for illumination. Designed with a cruciform plan, the church emphasized the west façade with two towers, a larger crossing tower (where the transepts and nave intersected), a narthex (an enclosed entrance area), a choir between the altar and the nave of the church, and chapels at the east end. All of these elements became characteristic of Romanesque architecture. With the building of Cluny III, completed in 1130, the church became the largest in Europe, rivaling St. Peter's in Rome, and a model for similarly ambitious projects.

First Romanesque or Lombard Romanesque

In the 10 th century, First, or Lombard, Romanesque was an early development in Lombardy region (now northern Italy), southern France, and reaching into Catalonia. Started by the Lombard Comacine Guild, or stonemasons, the style was distinctive for its solid stone construction, elaborate arching that advanced Roman models, bands of blind arches, or arches that had no openings, and vertical strips for exterior decorative effects. Particularly dominant in Catalonia, some of the best surviving examples are found in the Vall de Boí, a designated World Heritage Site in Catalonia.

Monastic Centers and Pilgrimages

During the Romanesque era, no longer under constant threat from Viking raids, monastic centers, which had provided cultural continuity and spiritual consolation through desperate times, became political, economic, religious, and artistic powerhouses that played a role in unifying Europe and in creating relative stability. Monastic centers that housed religious relics became stops on pilgrimage routes that extended for hundreds of miles throughout Europe to the very edge of Spain at Santiago de Compostela. Christians revered Santiago de Compostela as the burial site of Saint James, a disciple of Christ who brought Christianity to Spain, and thus deeply symbolic to Catholic Europe.

The faithful believed that by venerating relics, or remains of saints, in pilgrim churches they could obtain saintly intercession on their behalf for the forgiveness of their sins. Fierce competition for relics sometimes developed between churches and even resulted in the monks stealing relics from other churches, as was the case with the reliquary of St. Foy, in order to attract more pilgrims and, therefore, more money. As ever-larger crowds began to flock to sites, monastic centers expanded, providing lodging and food and farrier services to the pilgrims. As a result of this growth, various craft guilds were employed to meet the demand for Romanesque construction.

Romanesque Architecture and Art: Concepts, Styles, and Trends

Found throughout Europe and the British Isles, the Romanesque style took on regional variations, sometimes specific to a particular valley or town. The most noted sub styles were Mosan Art, Norman Romanesque, and Italian Romanesque.

Mosan Art, 1050-1232

Mosan art is named for the River Meuse valley in Belgium, where the style was centered around the town of Liege and the Benedictine monastery at Stavelot. Because of the region's location, it had many political and economic links to Aachen and was greatly influenced by the Carolingian Renaissance. The style became famous for its lavish and highly accomplished metalwork, employing gold and enameling in both the cloisonné technique, where metal is used to create raised partitions on the surface that are then filled with colored inlays, and the champlevé technique, where depressions are created in the surface and then filled. Noted metalworkers were Godefroid de Claire (de Huy), Nicholas of Verdun, and Hugo of Oignies. De Claire is credited with the creation of the Stavelot Triptych (1156-1158), both a portable altar and a reliquary containing fragments of True Cross, and Nicholas of Verdun's most noted work was his reliquary Shrine of the Magi (1180-1225). Mosan goldsmiths and metalworkers were employed throughout Europe by notable patrons and spread the style's influence.

Norman Romanesque (11 th -12 th centuries)

Norman Romanesque is primarily an English style named for the Normans who developed it after conquering England in 1066. Normandy, its name derived from the Latin Nortmanni, meaning "men of the north," became a Viking territory in 911, and the abstract decorative motifs of Norman architecture reflected the Viking love of such elements. Thomas Rickman in his An Attempt to Discriminate the Styles of English Architecture from the Conquest to the Reformation (1817) first used the term Norman Romanesque to refer to the style. Used for cathedrals and churches but also castles and keeps, Norman Romanesque was distinctive for its massive walls, its cylindrical and compound piers, and the Norman arch, employed to make grand archways. A wider and higher ceiling became possible, replacing the narrow limitations of the preceding barrel vault.

The style developed in Normandy, France, and England simultaneously, but in England it evolved into a distinctive sub-style that combined the austerity of the Norman style with a tendency toward decoration. A noted masterwork was Durham Cathedral (1093-1140) built under the leadership of William of St. Carilef. Though the cathedral was later redesigned in the Gothic style, some Norman elements, particularly the nave of the church, remain.

Italian Romanesque

Italian Romanesque is characterized by a distinctive use of gallery façades, projecting porches, and campaniles, or bell towers. Regional variations occurred; for instance, the Northern Italian style had wide and severe looking stone façades, as seen in San Ambrogio in Milan (1140). However, the most important regional style was the Pisan style, sometimes called the Tuscan, or Central, style, favoring classical and refined decorative effects and using gallery facades and projected porches with horizontal bands of colored marble. Decorative elements included scenes of daily life, hunting scenes, and classical subjects, and bronze doors were frequently employed. The Piazza del Duomo, or Cathedral Square, in Pisa, which included the Baptistery (1153) the Cathedral (1063-1092) and the Campanile (1172) is the most famous example.

Later Developments - After Romanesque Architecture and Art

The Romanesque style continued to be employed through most of the 12 th century, except in the area around Paris where the Gothic style began in 1120. Subsequently as the Gothic style spread, the Romanesque style was superseded and existent churches were often expanded and redesigned with new Gothic elements, retaining only a few traces of the earlier style. In more rural regions, however, the Romanesque style continued into the 13 th century. Romanesque design was foundational to the Gothic which continued using a cruciform plan, a western façade with two towers, and carved tympanums above the portals. Similarly, Gothic art was informed by the same movement toward a more realistic treatment of the human form that can be seen in the Romanesque Mosan style. Romanesque tapestries, like the Bayeux Tapestry, influenced the formation of tapestry workshops throughout Europe in the Gothic period and beyond.

Romanesque Revival styles first developed in England with Inigo Jones' redesign of the White Tower (1637-1638). In the following century Norman Revival castles were built for estates throughout the British Isles, and in the early 1800s, Thomas Pesnon developed a revival style for churches. Romanesque manuscript illumination, with its jewel-like colors and stylized motifs, also influenced and informed the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood and the Arts and Crafts movement in the middle and later 19 th century.

In Germany Rundbogenstil , or round-arch style, became popular around 1830, and the style was influential in America, as seen in the Paul Robeson Theater, formerly the Fourth Universalist Church in Fort Greene, Brooklyn (1833-34) and the former Astor Library, now the Public Theatre (1849-1881), in Lower Manhattan.

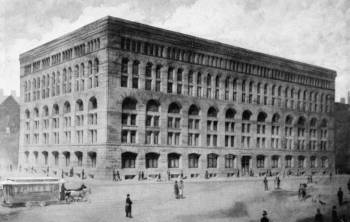

In America the first work of Romanesque Revival architecture was Richard Upjohn's Maaronite Cathedral of Our Lady of Lebanon (1844-1846) in Brooklyn. The American architect James Renwick's design for the Smithsonian Institute (1847-1851) was a prominent example. The style became known as Richardsonian Romanesque, as Henry Hobson Richardson actively promoted the style and designed notable buildings including the Marshall Field Wholesale Store (1885-1887) in Chicago and Trinity Church (1872-1877) in Boston. Harvard University commissioned Richardson to design several campus buildings, including Sever Hall (1878-1880), considered one of his masterpieces and designated a National Historic Landmark. As a result the style was adopted by other American universities in the following decades.

Useful Resources on Romanesque Architecture and Art

- Romanesque: Architecture, Sculpture, Painting Our Pick By Rolf Toman

- Romanesque Art: Perspectives Our Pick By Andreas Petzold

- The Stavelot Triptych , Mosan Art, and the Legend of the True Cross By Pierpont Morgan Library and Charles Ryskamp

- The Bayeux Tapestry Our Pick By Lucien Musset and Richard Rex

- Bayeux Museum Our Pick

- Immersive experience in a World Heritage Site Our Pick #Taull1123 is an immersive on-site experience that brings visitors of the Romanesque church of Sant Climent de Taüll

- Winchester BibleExhibition Blog Our Pick

- Super Art Gems of New York City By Thomas Hoving / ArtNet.com

- Ireland's Exquisite Insular Art Our Pick By James Wiener / Ancient History et cetera / October 30, 2014

- Bayeux tapestry: a brag, a lament, an embodiment of history's complexity Our Pick By Jonathan Jones / The Guardian / January 19, 2018

- The Bayeux tapestry: is it any good? By Jonathan Jones / The Guardian / January 17, 2018

Similar Art

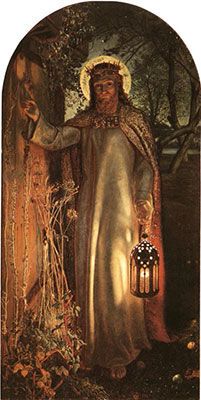

Light of the World (1853-54)

Related artists.

Related Movements & Topics

Content compiled and written by Rebecca Seiferle

Edited and revised, with Summary and Accomplishments added by Valerie Hellstein

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

17.2: Romanesque Architecture

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 53047

First Romanesque Architecture

The First Romanesque style developed in the Catalan territory and demonstrated a lower level of expertise than the later Romanesque style.

Learning Objectives

Differentiate between First Romanesque and Romanesque styles of architecture

Key Takeaways

- The First Romanesque style developed in the north of Italy, parts of France, and the Iberian Peninsula during the 10th and 11th centuries.

- Abott Oliba of the Monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll served as an important supporter of the First Romanesque style.

- The term “First Romanesque” was coined by architect Josep Puig i Cadafalch.

- First Romanesque, also known as Lombard Romanesque, is characterized by thick walls, lack of sculpture, and the presence of rhythmic ornamental arches known as Lombard bands .

- In contrast to the refinement of the later Romanesque style, First Romanesque architecture employed rubble walls, smaller windows, and unvaulted roofs.

- Romanesque : The art of Europe from approximately 1000 CE to the rise of the Gothic style in the 13th century or later, depending on region.

- First Romanesque : The name given by Josep Puig i Cadafalch to refer to the Romanesque art developed in Catalonia since the late 10th century.

- Lombard band : A decorative blind arcade, usually exterior, often used during the Romanesque and Gothic periods of architecture.

Development of First Romanesque Architecture

Romanesque architecture is divided into two periods: the “First Romanesque” style and the “Romanesque” style. The First Romanesque style developed in the north of Italy, parts of France, and the Iberian Peninsula in the 10 th century prior to the later influence of the Abbey of Cluny. The style is attributed to architectural activity by groups of Lombard teachers and stonemasons working in the Catalan territory during the first quarter of the 11th century. Abott Oliba of the Monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll served as a particularly influential impeller, diffuser, and sponsor of the First Romanesque style.

To avoid the term Pre-Romanesque, which is often used with a much broader meaning to refer to early Medieval and early Christian art (and in Spain may also refer to the Visigothic, Asturias, Mozarabic, and Repoblación art forms) Puig i Cadafalch preferred to use the term “First Romanesque.”

Characteristics

The First Romanesque style, also known as Lombard Romanesque style, is characterized by thick walls, lack of sculpture, and the presence of rhythmic ornamental arches known as Lombard bands. The difference between the First Romanesque and later Romanesque styles is a matter of the expertise with which the buildings were constructed. First Romanesque employed rubble walls, smaller windows, and unvaulted roofs, while the Romanesque style is distinguished by a more refined style and increased use of the vault and dressed stone. For example, Abott Oliba ordered an extension to the Monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll in 1032 mirroring the First Romanesque characteristics of two frontal towers, a cruise with seven apses , and Lombard ornamentation of blind arches and vertical strips.

Ripoll Monastery : The Monastery of Santa Maria de Ripoll is a Benedictine monastery built in the First Romanesque style, located in the town of Ripoll in Catalonia, Spain. Although much of the present church includes 19th century rebuilding, the sculptured portico is a renowned work of Romanesque art.

Cistercian Architecture

The Cistercians are a Roman Catholic order whose monasteries and churches reflect one of the most beautiful styles of medieval architecture.

Relate Cistercian architecture to the rational principles upon which it is based

- Architecturally speaking, the Cistercian monasteries and churches are counted among the most beautiful relics of the Middle Ages due to their pure style .

- Cistercian architecture embodied the ideals of the order and in theory was utilitarian and without superfluous ornament .

- The Cisterian order, however, was receptive to the technical improvements of Gothic principles of construction and played an important role in the spread of these techniques across Europe.

- Cistercian construction involved vast amounts of quarried stone and employed the best stone cutters.

- Gothic : Of or relating to the architectural style favored in western Europe in the 12th to 16th centuries.

- Romanesque : Refers to the art of Europe from approximately 1000 CE to the rise of the Gothic style in the 13th century or later, depending on region.

- Cistercian : A member of a monastic order related to the Benedictines, who hold a vow of silence.

The Cistercians are a Roman Catholic religious order of enclosed monks and nuns. This order was founded by a group of Benedictine monks from the Molesme monastery in 1098, with the goal of more closely following the Rule of Saint Benedict.

Characteristics of Cistercian Architecture

Cistercian architecture is considered one of the most beautiful styles of medieval architecture and has made an important contribution to European civilization . Because of the pure style of the Cistercian monasteries and churches, they are counted among the most beautiful relics of the Middle Ages. Cistercian institutions were primarily constructed in Romanesque and Gothic architectural styles during the Middle Ages, although later abbeys were also constructed in Renaissance and Baroque styles. The Cistercian abbeys of Fontenay in France, Fountains in England, Alcobaça in Portugal, Poblet in Spain, and Maulbronn in Germany are today recognized as UNESCO World Heritage Sites.

Fountains Abbey : The abbeys of 12th century England were stark and undecorated – a dramatic contrast with the elaborate churches of the wealthier Benedictine houses – yet to quote Warren Hollister, “even now the simple beauty of Cistercian ruins such as Fountains and Rievaulx, set in the wilderness of Yorkshire, is deeply moving”.

Theological Principles

Cistercian architecture was based on rational principles. In the mid-12 th century, the prominent Benedictine Abbot Suger of Saint-Denis united elements of Norman architecture with elements of Burgundinian architecture (including rib vaults and pointed arches , respectively), creating the new style of Gothic architecture . This new “architecture of light” was intended to raise the observer “from the material to the immaterial;”it was, according to the 20 th century French historian Georges Duby, a “monument of app lied theology.” Cistercian architecture expressed a different aesthetic and theology while learning from the Benedictine’s advances. St. Bernard saw church decoration as a distraction from piety and favored austerity in the construction of monasteries, the order itself was receptive to the technical improvements of Gothic principles of construction and played an important role in its spread across Europe.

This new Cistercian architecture embodied the ideals of the order, and in theory it was utilitarian and without superfluous ornament. The same rational, integrated scheme was used across Europe to meet the largely homogeneous needs of the order. Various buildings, including the chapter-house to the east and the dormitories above, were grouped around a cloister and sometimes linked to the transept of the church itself by a night stair. Cistercian churches were typically built on a cruciform layout, with a short presbytery to meet the liturgical needs of the brethren, small chapels in the transepts for private prayer , and an aisle-edged nave divided roughly in the middle by a screen to separate the monks from the lay brothers.

Santa Maria Arabona : Abbey church of Santa Maria Arabona, Italy.

Engineering and Construction

Cistercian buildings were made of smooth, pale stone where possible. Columns , pillars , and windows fell at the same base level, and plastering was extremely simple or nonexistent. The sanctuary kept to a proportion of 1:2 at both elevation and floor levels. To maintain the appearance of ecclesiastical buildings, Cistercian sites were constructed in a pure, rational style, lending to their beauty and simplicity. The building projects of the Church in the High Middle Ages showed an ambition for the colossal , requiring vast amounts of quarried stone. This was also true of the Cistercian projects. Foigny Abbey was 98 meters (322 ft) long; Vaucelles Abbey was 132 metres (433 ft) long. Even the most humble monastic buildings were constructed entirely of stone. In the 12 th and 13 th centuries, Cistercian barns consisted of a stone exterior divided into nave and aisles either by wooden posts or by stone piers .

The Cistercians recruited the best stone cutters. As early as 1133, St. Bernard hired workers to help the monks erect new buildings at Clairvaux. The oldest recorded example of architectural tracing, Byland Abbey in Yorkshire, dates to the 12 th century. Tracings were architectural drawings incised and painted in stone to a depth of 2–3 mm, showing architectural detail to scale.

Acey Abbey, France : The “architecture of light” of Acey Abbey represents the pure style of Cistercian architecture, intended for the utilitarian purposes of liturgical celebration.

Characteristics of Romanesque Architecture

While Romanesque architecture tends to possess certain key features, these often vary in appearance and building material from region to region.

Identify the defining characteristics and variations of Romanesque architecture found throughout Europe

- Variations in Romanesque architecture can be noted in earlier styles compared later styles; differences in building materials and local inspirations also led to variations across regions.

- Romanesque architecture varies in appearance of walls, piers , arches and openings, arcades , columns , vaults , and roofs and in the materials used to create these features.

- A characteristic feature of Romanesque architecture, both ecclesiastic and domestic, is the pairing of two arched windows or arcade openings separated by a pillar or colonette and often set within a larger arch.

- Columns were often used in Romanesque architecture, but varied in building material and decorative style. The alternation of piers and columns was found in both churches and castles.

- The majority of buildings have wooden roofs consisting of a simple truss , tie beam, or king post form . Vaults of stone or brick took on several different forms and showed marked development during the period, evolving into the pointed, ribbed arch characteristic of Gothic architecture .

- capital : The uppermost part of a column.

- blind arcade : A series of arches often used in Romanesque and Gothic buildings with no actual openings and no load-bearing function, simply serving as a decorative element.

- ocular window : A circular opening without tracery, found in many Italian churches.

- vault : An arched structure of masonry forming a ceiling or canopy.

- Piers : In architecture, an upright support for a structure or superstructure such as an arch or bridge.

Variations in Romanesque Architecture

The general impression given by both ecclesiastical and secular Romanesque architecture is that of massive solidity and strength. Romanesque architecture relies upon its walls, or sections of walls called piers , to bear the load of the structure, rather than using arches, columns, vaults, and other systems to manage the weight. As a result, the walls are massive, giving the impression of sturdy solidity. Romanesque design is also characterized by the presence of arches and openings, arcades, columns, vaults, and roofs. In spite of the general existence of these items, Romanesque architecture varies in how these characteristics are presented. For example, walls may be made of different materials or arches and openings may vary in shape. Later examples of Romanesque architecture may also possess features that earlier forms do not.

The building material used in Romanesque architecture varies across Europe depending on local stone and building traditions. In Italy, Poland, much of Germany, and parts of the Netherlands, brick was customary. Other areas saw extensive use of limestone , granite, and flint . The building stone was often used in small, irregular pieces bedded in thick mortar. Smooth ashlar masonry was not a distinguishing feature of the style in the earlier part of the period, but occurred where easily worked limestone was available.

Arches and Openings

A characteristic feature of Romanesque architecture, both ecclesiastic and domestic, is the pairing of two arched windows or arcade openings separated by a pillar or colonette and often set within a larger arch. Ocular windows are common in Italy, particularly in the facade gable , and are also seen in Germany. Later Romanesque churches may have wheel windows or rose windows with plate tracery . In a few Romanesque buildings , such as Autun Cathedral in France and Monreale Cathedral in Sicily, pointed arches have been used extensively.

Abbey Church of St. James, Lebeny, Hungary (1208) : Characteristics of Romanesque architecture include the ocular window and the pairing of two arched windows or arcade openings within a larger arch, both open here at the Abbey Church of St. James.

The arcade of a cloister typically consists of a single stage (story), while the arcade that divides the nave and aisles in a church typically has two stages, with a third stage of window openings known as the clerestory rising above. Arcades on a large scale generally fulfills a structural purpose, but they are also used decoratively on a smaller scale both internally and externally. External arcades are frequently called “blind arcades,” with only a wall or a narrow passage behind them.

Collegiate Church of Nivelles : The Collegiate Church of Nivelles, Belgium uses fine shafts of Belgian marble to define alternating blind openings and windows. Upper windows are similarly separated into two openings by colonettes.

Notre Dame du Puy : The facade of Notre Dame du Puy, le Puy en Velay, France, has a more complex arrangement of diversified arches: doors of varying widths, blind arcading, windows, and open arcades.

Although basically rectangular, piers can often be highly complex, with half-segments of large hollow-core columns on the inner surface supporting the arch and a clustered group of smaller shafts leading into the moldings of the arch. Piers that occur at the intersection of two large arches, such as those under the crossing of the nave and transept , are commonly cruciform in shape, each with its own supporting rectangular pier perpendicular to the other.

Columns were often used in Romanesque architecture, but varied in building material and decorative style. In Italy, a great number of antique Roman columns were salvaged and reused in the interiors and on the porticos of churches. In most parts of Europe, Romanesque columns were massive, supporting thick upper walls with small windows and sometimes heavy vaults. Where massive columns were called for, such as those at Durham Cathedral, they were constructed of ashlar masonry with a hollow core was filled with rubble. These huge untapered columns were sometimes ornamented with incised decorations.

Durham Cathedral, England : Durham Cathedral has decorated masonry columns alternating with piers of clustered shafts supporting the earliest example of pointed high ribs.

A common characteristic of Romanesque buildings, found in both churches and in the arcades that separate large interior spaces of castles, is the alternation of piers and columns. The most simple form is a column between each adjoining pier. Sometimes the columns are in multiples of two or three. Often the arrangement is made more complex by the complexity of the piers themselves, so that the alternation was not of piers and columns but rather of piers of entirely different forms.

The foliate Corinthian style provided the inspiration for many Romanesque capitals , and the accuracy with which they were carved depended on the availability of original models. Capitals in Italian churches, such as Pisa Cathedral or church of Sant’Alessandro in Lucca and southern France, are much closer to the Classical form and style than those in England.

Corinthian style capitals : Capital of Corinthian form with anthropomorphised details, Pisa Campanile

Vaults and Roofs

The majority of buildings have wooden roofs in a simple truss, tie beam, or king post form. Trussed rafter roofs are sometimes lined with wooden ceilings in three sections like those that survive at Ely and Peterborough cathedrals in England. In churches, typically the aisles are vaulted but the nave is roofed with timber , as is the case at both Peterborough and Ely. In Italy, open wooden roofs were common, tie beams frequently occurred in conjunction with vaults, and the timbers were often decorated, as at San Miniato al Monte, Florence.

Vaults of stone or brick took on several different forms and showed marked development during the period, evolving into the pointed, ribbed arch characteristic of Gothic architecture.

Architecture of the Holy Roman Empire

Architecture from the Holy Roman Empire spans from the Romanesque to the Classic eras.

Compare the characteristics of Romanesque architecture to pre-Romanesque and later styles

- The Holy Roman Empire existed from 962 to 1806 and at its peak included territories of the Kingdoms of Germany, Bohemia, Italy, and Burgundy.

- Pre- Romanesque architecture is thought to have originated with the Carolingian Renaissance in the late 8th century.

- The Romanesque period (10th – early 13th century) is characterized by semi-circular arches , robust appearance, small paired windows, and groin vaults .

- Gothic architecture such as the Cologne Cathedral flourished during the high and late medieval periods.

- Renaissance architecture (early 15th – early 17th centuries) flourished in parts of Europe with a conscious revival and development of ancient Greek and Roman thought and culture .

- Baroque architecture began in the early 17th century in Italy and arrived in Germany after the Thirty Years War. The interaction of architecture, painting, and sculpture is an essential feature of Baroque architecture.

- Classicism arrived in Germany in the second half of the 18th century, just prior to the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire.

- Ottonian Renaissance : A minor renaissance that accompanied the reigns of the first three emperors of the Saxon Dynasty, all named Otto: Otto I (936–973), Otto II (973–983), and Otto III (983–1002).

- Rococo : An 18th-century artistic movement and style which affected several aspects of the arts, including painting, sculpture, architecture, interior design, decoration, literature, music, and theater; also referred to as Late Baroque.

Background: The Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a varying complex of lands that existed from 962 to 1806 in Central Europe. The empire’s territory lay predominantly in Central Europe and at its peak included territories of the Kingdoms of Germany, Bohemia, Italy, and Burgundy. For much of its history, the Empire consisted of hundreds of smaller sub-units, principalities, duchies, counties, Free Imperial Cities, and other domains.

Pre-Romanesque