23 Advantages and Disadvantages of Qualitative Research

Investigating methodologies. Taking a closer look at ethnographic, anthropological, or naturalistic techniques. Data mining through observer recordings. This is what the world of qualitative research is all about. It is the comprehensive and complete data that is collected by having the courage to ask an open-ended question.

Print media has used the principles of qualitative research for generations. Now more industries are seeing the advantages that come from the extra data that is received by asking more than a “yes” or “no” question.

The advantages and disadvantages of qualitative research are quite unique. On one hand, you have the perspective of the data that is being collected. On the other hand, you have the techniques of the data collector and their own unique observations that can alter the information in subtle ways.

That’s why these key points are so important to consider.

What Are the Advantages of Qualitative Research?

1. Subject materials can be evaluated with greater detail. There are many time restrictions that are placed on research methods. The goal of a time restriction is to create a measurable outcome so that metrics can be in place. Qualitative research focuses less on the metrics of the data that is being collected and more on the subtleties of what can be found in that information. This allows for the data to have an enhanced level of detail to it, which can provide more opportunities to glean insights from it during examination.

2. Research frameworks can be fluid and based on incoming or available data. Many research opportunities must follow a specific pattern of questioning, data collection, and information reporting. Qualitative research offers a different approach. It can adapt to the quality of information that is being gathered. If the available data does not seem to be providing any results, the research can immediately shift gears and seek to gather data in a new direction. This offers more opportunities to gather important clues about any subject instead of being confined to a limited and often self-fulfilling perspective.

3. Qualitative research data is based on human experiences and observations. Humans have two very different operating systems. One is a subconscious method of operation, which is the fast and instinctual observations that are made when data is present. The other operating system is slower and more methodical, wanting to evaluate all sources of data before deciding. Many forms of research rely on the second operating system while ignoring the instinctual nature of the human mind. Qualitative research doesn’t ignore the gut instinct. It embraces it and the data that can be collected is often better for it.

4. Gathered data has a predictive quality to it. One of the common mistakes that occurs with qualitative research is an assumption that a personal perspective can be extrapolated into a group perspective. This is only possible when individuals grow up in similar circumstances, have similar perspectives about the world, and operate with similar goals. When these groups can be identified, however, the gathered individualistic data can have a predictive quality for those who are in a like-minded group. At the very least, the data has a predictive quality for the individual from whom it was gathered.

5. Qualitative research operates within structures that are fluid. Because the data being gathered through this type of research is based on observations and experiences, an experienced researcher can follow-up interesting answers with additional questions. Unlike other forms of research that require a specific framework with zero deviation, researchers can follow any data tangent which makes itself known and enhance the overall database of information that is being collected.

6. Data complexities can be incorporated into generated conclusions. Although our modern world tends to prefer statistics and verifiable facts, we cannot simply remove the human experience from the equation. Different people will have remarkably different perceptions about any statistic, fact, or event. This is because our unique experiences generate a different perspective of the data that we see. These complexities, when gathered into a singular database, can generate conclusions with more depth and accuracy, which benefits everyone.

7. Qualitative research is an open-ended process. When a researcher is properly prepared, the open-ended structures of qualitative research make it possible to get underneath superficial responses and rational thoughts to gather information from an individual’s emotional response. This is critically important to this form of researcher because it is an emotional response which often drives a person’s decisions or influences their behavior.

8. Creativity becomes a desirable quality within qualitative research. It can be difficult to analyze data that is obtained from individual sources because many people subconsciously answer in a way that they think someone wants. This desire to “please” another reduces the accuracy of the data and suppresses individual creativity. By embracing the qualitative research method, it becomes possible to encourage respondent creativity, allowing people to express themselves with authenticity. In return, the data collected becomes more accurate and can lead to predictable outcomes.

9. Qualitative research can create industry-specific insights. Brands and businesses today need to build relationships with their core demographics to survive. The terminology, vocabulary, and jargon that consumers use when looking at products or services is just as important as the reputation of the brand that is offering them. If consumers are receiving one context, but the intention of the brand is a different context, then the miscommunication can artificially restrict sales opportunities. Qualitative research gives brands access to these insights so they can accurately communicate their value propositions.

10. Smaller sample sizes are used in qualitative research, which can save on costs. Many qualitative research projects can be completed quickly and on a limited budget because they typically use smaller sample sizes that other research methods. This allows for faster results to be obtained so that projects can move forward with confidence that only good data is able to provide.

11. Qualitative research provides more content for creatives and marketing teams. When your job involves marketing, or creating new campaigns that target a specific demographic, then knowing what makes those people can be quite challenging. By going through the qualitative research approach, it becomes possible to congregate authentic ideas that can be used for marketing and other creative purposes. This makes communication between the two parties to be handled with more accuracy, leading to greater level of happiness for all parties involved.

12. Attitude explanations become possible with qualitative research. Consumer patterns can change on a dime sometimes, leaving a brand out in the cold as to what just happened. Qualitative research allows for a greater understanding of consumer attitudes, providing an explanation for events that occur outside of the predictive matrix that was developed through previous research. This allows the optimal brand/consumer relationship to be maintained.

What Are the Disadvantages of Qualitative Research?

1. The quality of the data gathered in qualitative research is highly subjective. This is where the personal nature of data gathering in qualitative research can also be a negative component of the process. What one researcher might feel is important and necessary to gather can be data that another researcher feels is pointless and won’t spend time pursuing it. Having individual perspectives and including instinctual decisions can lead to incredibly detailed data. It can also lead to data that is generalized or even inaccurate because of its reliance on researcher subjectivisms.

2. Data rigidity is more difficult to assess and demonstrate. Because individual perspectives are often the foundation of the data that is gathered in qualitative research, it is more difficult to prove that there is rigidity in the information that is collective. The human mind tends to remember things in the way it wants to remember them. That is why memories are often looked at fondly, even if the actual events that occurred may have been somewhat disturbing at the time. This innate desire to look at the good in things makes it difficult for researchers to demonstrate data validity.

3. Mining data gathered by qualitative research can be time consuming. The number of details that are often collected while performing qualitative research are often overwhelming. Sorting through that data to pull out the key points can be a time-consuming effort. It is also a subjective effort because what one researcher feels is important may not be pulled out by another researcher. Unless there are some standards in place that cannot be overridden, data mining through a massive number of details can almost be more trouble than it is worth in some instances.

4. Qualitative research creates findings that are valuable, but difficult to present. Presenting the findings which come out of qualitative research is a bit like listening to an interview on CNN. The interviewer will ask a question to the interviewee, but the goal is to receive an answer that will help present a database which presents a specific outcome to the viewer. The goal might be to have a viewer watch an interview and think, “That’s terrible. We need to pass a law to change that.” The subjective nature of the information, however, can cause the viewer to think, “That’s wonderful. Let’s keep things the way they are right now.” That is why findings from qualitative research are difficult to present. What a research gleans from the data can be very different from what an outside observer gleans from the data.

5. Data created through qualitative research is not always accepted. Because of the subjective nature of the data that is collected in qualitative research, findings are not always accepted by the scientific community. A second independent qualitative research effort which can produce similar findings is often necessary to begin the process of community acceptance.

6. Researcher influence can have a negative effect on the collected data. The quality of the data that is collected through qualitative research is highly dependent on the skills and observation of the researcher. If a researcher has a biased point of view, then their perspective will be included with the data collected and influence the outcome. There must be controls in place to help remove the potential for bias so the data collected can be reviewed with integrity. Otherwise, it would be possible for a researcher to make any claim and then use their bias through qualitative research to prove their point.

7. Replicating results can be very difficult with qualitative research. The scientific community wants to see results that can be verified and duplicated to accept research as factual. In the world of qualitative research, this can be very difficult to accomplish. Not only do you have the variability of researcher bias for which to account within the data, but there is also the informational bias that is built into the data itself from the provider. This means the scope of data gathering can be extremely limited, even if the structure of gathering information is fluid, because of each unique perspective.

8. Difficult decisions may require repetitive qualitative research periods. The smaller sample sizes of qualitative research may be an advantage, but they can also be a disadvantage for brands and businesses which are facing a difficult or potentially controversial decision. A small sample is not always representative of a larger population demographic, even if there are deep similarities with the individuals involve. This means a follow-up with a larger quantitative sample may be necessary so that data points can be tracked with more accuracy, allowing for a better overall decision to be made.

9. Unseen data can disappear during the qualitative research process. The amount of trust that is placed on the researcher to gather, and then draw together, the unseen data that is offered by a provider is enormous. The research is dependent upon the skill of the researcher being able to connect all the dots. If the researcher can do this, then the data can be meaningful and help brands and progress forward with their mission. If not, there is no way to alter course until after the first results are received. Then a new qualitative process must begin.

10. Researchers must have industry-related expertise. You can have an excellent researcher on-board for a project, but if they are not familiar with the subject matter, they will have a difficult time gathering accurate data. For qualitative research to be accurate, the interviewer involved must have specific skills, experiences, and expertise in the subject matter being studied. They must also be familiar with the material being evaluated and have the knowledge to interpret responses that are received. If any piece of this skill set is missing, the quality of the data being gathered can be open to interpretation.

11. Qualitative research is not statistically representative. The one disadvantage of qualitative research which is always present is its lack of statistical representation. It is a perspective-based method of research only, which means the responses given are not measured. Comparisons can be made and this can lead toward the duplication which may be required, but for the most part, quantitative data is required for circumstances which need statistical representation and that is not part of the qualitative research process.

The advantages and disadvantages of qualitative research make it possible to gather and analyze individualistic data on deeper levels. This makes it possible to gain new insights into consumer thoughts, demographic behavioral patterns, and emotional reasoning processes. When a research can connect the dots of each information point that is gathered, the information can lead to personalized experiences, better value in products and services, and ongoing brand development.

- Business Intelligence Reporting

- Data Driven

- Data Analysis Method

- Business Model

- Business Analysis

- Quantitative Research

- Business Analytics

- Marketing Analytics

- Data Integration

- Digital Transformation Strategy

- Online Training

- Local Training Events

5 Strengths and 5 Limitations of Qualitative Research

Lauren Christiansen

Insight into qualitative research.

Anyone who reviews a bunch of numbers knows how impersonal that feels. What do numbers really reveal about a person's beliefs, motives, and thoughts? While it's critical to collect statistical information to identify business trends and inefficiencies, stats don't always tell the full story. Why does the customer like this product more than the other one? What motivates them to post this particular hashtag on social media? How do employees actually feel about the new supply chain process? To answer more personal questions that delve into the human experience, businesses often employ a qualitative research process.

10 Key Strengths and Limitations of Qualitative Research

Qualitative research helps entrepreneurs and established companies understand the many factors that drive consumer behavior. Because most organizations collect and analyze quantitative data, they don't always know exactly how a target market feels and what it wants. It helps researchers when they can observe a small sample size of consumers in a comfortable environment, ask questions, and let them speak. Research methodology varies depending on the industry and type of business needs. Many companies employ mixed methods to extract the insights they require to improve decision-making. While both quantitative research and qualitative methods are effective, there are limitations to both. Quantitative research is expensive, time-consuming, and presents a limited understanding of consumer needs. However, qualitative research methods generate less verifiable information as all qualitative data is based on experience. Businesses should use a combination of both methods to overcome any associated limitations.

Strengths of Qualitative Research

- Captures New Beliefs - Qualitative research methods extrapolate any evolving beliefs within a market. This may include who buys a product/service, or how employees feel about their employers.

- Fewer Limitations - Qualitative studies are less stringent than quantitative ones. Outside the box answers to questions, opinions, and beliefs are included in data collection and data analysis.

- More Versatile - Qualitative research is much easier at times for researchers. They can adjust questions, adapt to circumstances that change or change the environment to optimize results.

- Greater Speculation - Researchers can speculate more on what answers to drill down into and how to approach them. They can use instinct and subjective experience to identify and extract good data.

- More Targeted - This research process can target any area of the business or concern it may have. Researchers can concentrate on specific target markets to collect valuable information. This takes less time and requires fewer resources than quantitative studies.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Sample Sizes - Businesses need to find a big enough group of participants to ensure results are accurate. A sample size of 15 people is not enough to show a reliable picture of how consumers view a product. If it is not possible to find a large enough sample size, the data collected may be insufficient.

- Bias - For internal qualitative studies, employees may be biased. For example, workers may give a popular answer that colleagues agree with rather than a true opinion. This can negatively influence the outcome of the study.

- Self-Selection Bias - Businesses that call on volunteers to answer questions worry that the people who respond are not reflective of the greater group. It is better if the company selects individuals at random for research studies, particularly if they are employees. However, this changes the process from qualitative to quantitative methods.

- Artificial - It isn't typical to observe consumers in stores, gather a focus group together, or ask employees about their experiences at work. This artificiality may impact the findings, as it is outside the norm of regular behavior and interactions.

- Quality - Questions It's hard to know whether researcher questions are quality or not because they are all subjective. Researchers need to ask how and why individuals feel the way they do to receive the most accurate answers.

Key Takeaways on Strengths and Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Qualitative research helps entrepreneurs and small businesses understand what drives human behavior. It is also used to see how employees feel about workflows and tasks.

- Companies can extract insights from qualitative research to optimize decision-making and improve products or services.

- Qualitative research captures new beliefs, has fewer limitations, is more versatile, and is more targeted. It also allows researchers to speculate and insert themselves more into the research study.

- Qualitative research has many limitations which include possible small sample sizes, potential bias in answers, self-selection bias, and potentially poor questions from researchers. It also can be artificial because it isn't typical to observe participants in focus groups, ask them questions at work, or invite them to partake in this type of research method.

Must-Read Content

The Top Qualitative Research Methods for Business Success

5 Qualitative Research Examples in Action

7 Types of Qualitative Research to Look Out For

What is Qualitative Research, Really?

ReviseSociology

A level sociology revision – education, families, research methods, crime and deviance and more!

Qualitative Data – Strengths and Limitations

Table of Contents

Last Updated on September 1, 2021 by Karl Thompson

A summary of the theoretical, practical and ethical strengths and weaknesses of qualitative data sources such as unstructured interviews, participant observation and documents.

Examples of Qualitative Data

- Open question questionnaires

- Unstructured interviews

- Participant observation

- Public and private documents such as newspapers and letters.

Theoretical strengths

- Better validity than for quantitative data

- More insight (Verstehen)

- More in-depth data

- More respondent-led, avoids the imposition problem.

- Good for exploring issues the researcher knows little about.

- Preferred by Interpretivists

Practical strengths

- A useful way of accessing groups who don’t like formal methods/ authority

Ethical strengths

- Useful for sensitive topics

- Allows respondents to ‘speak for themselves’

- Treats respondents as equals

Theoretical limitations

- Difficult to make comparisons

- No useful for finding trends, finding correlations.

- Typically small samples, low representativeness

- Low reliability as difficult to repeat the exact context of research.

- Subjective bias of researcher may influence data (interviewer bias)

- Disliked by Positivists

Practical limitations

- Time consuming

- Expensive per person researched compared to qualitative data

- Difficult to gain access (PO)

- Analyzing data can be difficult

Ethical limitations

- Close contact means more potential for harm

- Close contact means more difficult to guarantee anonymity and confidentiality

- Informed consent can be an issue with PO.

Nature of Topic – When would you use it, when would you avoid using it?

- Useful for complex topics you know little about

- Not necessary for simple topics.

Signposting

This post has been written as a revision summary for students revising the research methods aspect of A-level sociology.

More in-depth versions of qualitative data topics can be found below…

Covert and Covert Participant Observation

The strengths and limitations of covert participant observation

Interviews in Social Research

Secondary Qualitative Data Analysis in Sociology

Please click here to return to the homepage – ReviseSociology.com

Share this:

- Share on Tumblr

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Discover more from ReviseSociology

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Continue reading

Qualitative Study

Affiliations.

- 1 University of Nebraska Medical Center

- 2 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting

- 3 GDB Research and Statistical Consulting/McLaren Macomb Hospital

- PMID: 29262162

- Bookshelf ID: NBK470395

Qualitative research is a type of research that explores and provides deeper insights into real-world problems. Instead of collecting numerical data points or intervene or introduce treatments just like in quantitative research, qualitative research helps generate hypotheses as well as further investigate and understand quantitative data. Qualitative research gathers participants' experiences, perceptions, and behavior. It answers the hows and whys instead of how many or how much. It could be structured as a stand-alone study, purely relying on qualitative data or it could be part of mixed-methods research that combines qualitative and quantitative data. This review introduces the readers to some basic concepts, definitions, terminology, and application of qualitative research.

Qualitative research at its core, ask open-ended questions whose answers are not easily put into numbers such as ‘how’ and ‘why’. Due to the open-ended nature of the research questions at hand, qualitative research design is often not linear in the same way quantitative design is. One of the strengths of qualitative research is its ability to explain processes and patterns of human behavior that can be difficult to quantify. Phenomena such as experiences, attitudes, and behaviors can be difficult to accurately capture quantitatively, whereas a qualitative approach allows participants themselves to explain how, why, or what they were thinking, feeling, and experiencing at a certain time or during an event of interest. Quantifying qualitative data certainly is possible, but at its core, qualitative data is looking for themes and patterns that can be difficult to quantify and it is important to ensure that the context and narrative of qualitative work are not lost by trying to quantify something that is not meant to be quantified.

However, while qualitative research is sometimes placed in opposition to quantitative research, where they are necessarily opposites and therefore ‘compete’ against each other and the philosophical paradigms associated with each, qualitative and quantitative work are not necessarily opposites nor are they incompatible. While qualitative and quantitative approaches are different, they are not necessarily opposites, and they are certainly not mutually exclusive. For instance, qualitative research can help expand and deepen understanding of data or results obtained from quantitative analysis. For example, say a quantitative analysis has determined that there is a correlation between length of stay and level of patient satisfaction, but why does this correlation exist? This dual-focus scenario shows one way in which qualitative and quantitative research could be integrated together.

Examples of Qualitative Research Approaches

Ethnography

Ethnography as a research design has its origins in social and cultural anthropology, and involves the researcher being directly immersed in the participant’s environment. Through this immersion, the ethnographer can use a variety of data collection techniques with the aim of being able to produce a comprehensive account of the social phenomena that occurred during the research period. That is to say, the researcher’s aim with ethnography is to immerse themselves into the research population and come out of it with accounts of actions, behaviors, events, etc. through the eyes of someone involved in the population. Direct involvement of the researcher with the target population is one benefit of ethnographic research because it can then be possible to find data that is otherwise very difficult to extract and record.

Grounded Theory

Grounded Theory is the “generation of a theoretical model through the experience of observing a study population and developing a comparative analysis of their speech and behavior.” As opposed to quantitative research which is deductive and tests or verifies an existing theory, grounded theory research is inductive and therefore lends itself to research that is aiming to study social interactions or experiences. In essence, Grounded Theory’s goal is to explain for example how and why an event occurs or how and why people might behave a certain way. Through observing the population, a researcher using the Grounded Theory approach can then develop a theory to explain the phenomena of interest.

Phenomenology

Phenomenology is defined as the “study of the meaning of phenomena or the study of the particular”. At first glance, it might seem that Grounded Theory and Phenomenology are quite similar, but upon careful examination, the differences can be seen. At its core, phenomenology looks to investigate experiences from the perspective of the individual. Phenomenology is essentially looking into the ‘lived experiences’ of the participants and aims to examine how and why participants behaved a certain way, from their perspective . Herein lies one of the main differences between Grounded Theory and Phenomenology. Grounded Theory aims to develop a theory for social phenomena through an examination of various data sources whereas Phenomenology focuses on describing and explaining an event or phenomena from the perspective of those who have experienced it.

Narrative Research

One of qualitative research’s strengths lies in its ability to tell a story, often from the perspective of those directly involved in it. Reporting on qualitative research involves including details and descriptions of the setting involved and quotes from participants. This detail is called ‘thick’ or ‘rich’ description and is a strength of qualitative research. Narrative research is rife with the possibilities of ‘thick’ description as this approach weaves together a sequence of events, usually from just one or two individuals, in the hopes of creating a cohesive story, or narrative. While it might seem like a waste of time to focus on such a specific, individual level, understanding one or two people’s narratives for an event or phenomenon can help to inform researchers about the influences that helped shape that narrative. The tension or conflict of differing narratives can be “opportunities for innovation”.

Research Paradigm

Research paradigms are the assumptions, norms, and standards that underpin different approaches to research. Essentially, research paradigms are the ‘worldview’ that inform research. It is valuable for researchers, both qualitative and quantitative, to understand what paradigm they are working within because understanding the theoretical basis of research paradigms allows researchers to understand the strengths and weaknesses of the approach being used and adjust accordingly. Different paradigms have different ontology and epistemologies . Ontology is defined as the "assumptions about the nature of reality” whereas epistemology is defined as the “assumptions about the nature of knowledge” that inform the work researchers do. It is important to understand the ontological and epistemological foundations of the research paradigm researchers are working within to allow for a full understanding of the approach being used and the assumptions that underpin the approach as a whole. Further, it is crucial that researchers understand their own ontological and epistemological assumptions about the world in general because their assumptions about the world will necessarily impact how they interact with research. A discussion of the research paradigm is not complete without describing positivist, postpositivist, and constructivist philosophies.

Positivist vs Postpositivist

To further understand qualitative research, we need to discuss positivist and postpositivist frameworks. Positivism is a philosophy that the scientific method can and should be applied to social as well as natural sciences. Essentially, positivist thinking insists that the social sciences should use natural science methods in its research which stems from positivist ontology that there is an objective reality that exists that is fully independent of our perception of the world as individuals. Quantitative research is rooted in positivist philosophy, which can be seen in the value it places on concepts such as causality, generalizability, and replicability.

Conversely, postpositivists argue that social reality can never be one hundred percent explained but it could be approximated. Indeed, qualitative researchers have been insisting that there are “fundamental limits to the extent to which the methods and procedures of the natural sciences could be applied to the social world” and therefore postpositivist philosophy is often associated with qualitative research. An example of positivist versus postpositivist values in research might be that positivist philosophies value hypothesis-testing, whereas postpositivist philosophies value the ability to formulate a substantive theory.

Constructivist

Constructivism is a subcategory of postpositivism. Most researchers invested in postpositivist research are constructivist as well, meaning they think there is no objective external reality that exists but rather that reality is constructed. Constructivism is a theoretical lens that emphasizes the dynamic nature of our world. “Constructivism contends that individuals’ views are directly influenced by their experiences, and it is these individual experiences and views that shape their perspective of reality”. Essentially, Constructivist thought focuses on how ‘reality’ is not a fixed certainty and experiences, interactions, and backgrounds give people a unique view of the world. Constructivism contends, unlike in positivist views, that there is not necessarily an ‘objective’ reality we all experience. This is the ‘relativist’ ontological view that reality and the world we live in are dynamic and socially constructed. Therefore, qualitative scientific knowledge can be inductive as well as deductive.”

So why is it important to understand the differences in assumptions that different philosophies and approaches to research have? Fundamentally, the assumptions underpinning the research tools a researcher selects provide an overall base for the assumptions the rest of the research will have and can even change the role of the researcher themselves. For example, is the researcher an ‘objective’ observer such as in positivist quantitative work? Or is the researcher an active participant in the research itself, as in postpositivist qualitative work? Understanding the philosophical base of the research undertaken allows researchers to fully understand the implications of their work and their role within the research, as well as reflect on their own positionality and bias as it pertains to the research they are conducting.

Data Sampling

The better the sample represents the intended study population, the more likely the researcher is to encompass the varying factors at play. The following are examples of participant sampling and selection:

Purposive sampling- selection based on the researcher’s rationale in terms of being the most informative.

Criterion sampling-selection based on pre-identified factors.

Convenience sampling- selection based on availability.

Snowball sampling- the selection is by referral from other participants or people who know potential participants.

Extreme case sampling- targeted selection of rare cases.

Typical case sampling-selection based on regular or average participants.

Data Collection and Analysis

Qualitative research uses several techniques including interviews, focus groups, and observation. [1] [2] [3] Interviews may be unstructured, with open-ended questions on a topic and the interviewer adapts to the responses. Structured interviews have a predetermined number of questions that every participant is asked. It is usually one on one and is appropriate for sensitive topics or topics needing an in-depth exploration. Focus groups are often held with 8-12 target participants and are used when group dynamics and collective views on a topic are desired. Researchers can be a participant-observer to share the experiences of the subject or a non-participant or detached observer.

While quantitative research design prescribes a controlled environment for data collection, qualitative data collection may be in a central location or in the environment of the participants, depending on the study goals and design. Qualitative research could amount to a large amount of data. Data is transcribed which may then be coded manually or with the use of Computer Assisted Qualitative Data Analysis Software or CAQDAS such as ATLAS.ti or NVivo.

After the coding process, qualitative research results could be in various formats. It could be a synthesis and interpretation presented with excerpts from the data. Results also could be in the form of themes and theory or model development.

Dissemination

To standardize and facilitate the dissemination of qualitative research outcomes, the healthcare team can use two reporting standards. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research or COREQ is a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. The Standards for Reporting Qualitative Research (SRQR) is a checklist covering a wider range of qualitative research.

Examples of Application

Many times a research question will start with qualitative research. The qualitative research will help generate the research hypothesis which can be tested with quantitative methods. After the data is collected and analyzed with quantitative methods, a set of qualitative methods can be used to dive deeper into the data for a better understanding of what the numbers truly mean and their implications. The qualitative methods can then help clarify the quantitative data and also help refine the hypothesis for future research. Furthermore, with qualitative research researchers can explore subjects that are poorly studied with quantitative methods. These include opinions, individual's actions, and social science research.

A good qualitative study design starts with a goal or objective. This should be clearly defined or stated. The target population needs to be specified. A method for obtaining information from the study population must be carefully detailed to ensure there are no omissions of part of the target population. A proper collection method should be selected which will help obtain the desired information without overly limiting the collected data because many times, the information sought is not well compartmentalized or obtained. Finally, the design should ensure adequate methods for analyzing the data. An example may help better clarify some of the various aspects of qualitative research.

A researcher wants to decrease the number of teenagers who smoke in their community. The researcher could begin by asking current teen smokers why they started smoking through structured or unstructured interviews (qualitative research). The researcher can also get together a group of current teenage smokers and conduct a focus group to help brainstorm factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke (qualitative research).

In this example, the researcher has used qualitative research methods (interviews and focus groups) to generate a list of ideas of both why teens start to smoke as well as factors that may have prevented them from starting to smoke. Next, the researcher compiles this data. The research found that, hypothetically, peer pressure, health issues, cost, being considered “cool,” and rebellious behavior all might increase or decrease the likelihood of teens starting to smoke.

The researcher creates a survey asking teen participants to rank how important each of the above factors is in either starting smoking (for current smokers) or not smoking (for current non-smokers). This survey provides specific numbers (ranked importance of each factor) and is thus a quantitative research tool.

The researcher can use the results of the survey to focus efforts on the one or two highest-ranked factors. Let us say the researcher found that health was the major factor that keeps teens from starting to smoke, and peer pressure was the major factor that contributed to teens to start smoking. The researcher can go back to qualitative research methods to dive deeper into each of these for more information. The researcher wants to focus on how to keep teens from starting to smoke, so they focus on the peer pressure aspect.

The researcher can conduct interviews and/or focus groups (qualitative research) about what types and forms of peer pressure are commonly encountered, where the peer pressure comes from, and where smoking first starts. The researcher hypothetically finds that peer pressure often occurs after school at the local teen hangouts, mostly the local park. The researcher also hypothetically finds that peer pressure comes from older, current smokers who provide the cigarettes.

The researcher could further explore this observation made at the local teen hangouts (qualitative research) and take notes regarding who is smoking, who is not, and what observable factors are at play for peer pressure of smoking. The researcher finds a local park where many local teenagers hang out and see that a shady, overgrown area of the park is where the smokers tend to hang out. The researcher notes the smoking teenagers buy their cigarettes from a local convenience store adjacent to the park where the clerk does not check identification before selling cigarettes. These observations fall under qualitative research.

If the researcher returns to the park and counts how many individuals smoke in each region of the park, this numerical data would be quantitative research. Based on the researcher's efforts thus far, they conclude that local teen smoking and teenagers who start to smoke may decrease if there are fewer overgrown areas of the park and the local convenience store does not sell cigarettes to underage individuals.

The researcher could try to have the parks department reassess the shady areas to make them less conducive to the smokers or identify how to limit the sales of cigarettes to underage individuals by the convenience store. The researcher would then cycle back to qualitative methods of asking at-risk population their perceptions of the changes, what factors are still at play, as well as quantitative research that includes teen smoking rates in the community, the incidence of new teen smokers, among others.

Copyright © 2024, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

- Introduction

- Issues of Concern

- Clinical Significance

- Enhancing Healthcare Team Outcomes

- Review Questions

Publication types

- Study Guide

The UK Faculty of Public Health has recently taken ownership of the Health Knowledge resource. This new, advert-free website is still under development and there may be some issues accessing content. Additionally, the content has not been audited or verified by the Faculty of Public Health as part of an ongoing quality assurance process and as such certain material included maybe out of date. If you have any concerns regarding content you should seek to independently verify this.

Strengths and weaknesses

Strengths of qualitative research.

- Qualitative methods tend to collect very rich data in an efficient manner: rather than being limited to the responders to a set of pre-defined questions, it is possible to explore interesting concepts that can lead to novel theory by analysing the entirety of a participant’s interview/story/interaction.

- Qualitative methods can lead to the generation of new theory from unexpected findings that go against “conventional” public health understanding

- When combined with quantitative methods, qualitative research can provide a much more complete picture. For example, a well-designed process evaluation of a trial may provide important insights into participant attitudes, beliefs, and thoughts about the intervention and its acceptability, which may not be evident from the quantitative outcome evaluation.

Weaknesses of qualitative research

- It is important that qualitative researchers adhere to robust methodology in order to ensure high quality research. Poor quality qualitative work can lead to misleading findings.

- Qualitative research alone is often insufficient to make population-level summaries. The research is not designed for this purpose, as the aim is not to generate summaries generalisable to the wider population.

- Policy makers may not understand or value the interpretive position and therefore may not recognize the importance of qualitative research.

- Qualitative research can be time and labour-intensive. Conducting multiple interviews and focus groups can be logistically difficult to arrange and time consuming. Furthermore, tranalysanscription and analysis of the data (comparing, coding, and inducting) requires intense concentration and full immersion in the data – a process that can be far more time-consuming than a descriptive statistical analysis.

© I Crinson & M Leontowitsch 2006, G Morgan 2016

Qualitative vs Quantitative Research Methods & Data Analysis

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

What is the difference between quantitative and qualitative?

The main difference between quantitative and qualitative research is the type of data they collect and analyze.

Quantitative research collects numerical data and analyzes it using statistical methods. The aim is to produce objective, empirical data that can be measured and expressed in numerical terms. Quantitative research is often used to test hypotheses, identify patterns, and make predictions.

Qualitative research, on the other hand, collects non-numerical data such as words, images, and sounds. The focus is on exploring subjective experiences, opinions, and attitudes, often through observation and interviews.

Qualitative research aims to produce rich and detailed descriptions of the phenomenon being studied, and to uncover new insights and meanings.

Quantitative data is information about quantities, and therefore numbers, and qualitative data is descriptive, and regards phenomenon which can be observed but not measured, such as language.

What Is Qualitative Research?

Qualitative research is the process of collecting, analyzing, and interpreting non-numerical data, such as language. Qualitative research can be used to understand how an individual subjectively perceives and gives meaning to their social reality.

Qualitative data is non-numerical data, such as text, video, photographs, or audio recordings. This type of data can be collected using diary accounts or in-depth interviews and analyzed using grounded theory or thematic analysis.

Qualitative research is multimethod in focus, involving an interpretive, naturalistic approach to its subject matter. This means that qualitative researchers study things in their natural settings, attempting to make sense of, or interpret, phenomena in terms of the meanings people bring to them. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 2)

Interest in qualitative data came about as the result of the dissatisfaction of some psychologists (e.g., Carl Rogers) with the scientific study of psychologists such as behaviorists (e.g., Skinner ).

Since psychologists study people, the traditional approach to science is not seen as an appropriate way of carrying out research since it fails to capture the totality of human experience and the essence of being human. Exploring participants’ experiences is known as a phenomenological approach (re: Humanism ).

Qualitative research is primarily concerned with meaning, subjectivity, and lived experience. The goal is to understand the quality and texture of people’s experiences, how they make sense of them, and the implications for their lives.

Qualitative research aims to understand the social reality of individuals, groups, and cultures as nearly as possible as participants feel or live it. Thus, people and groups are studied in their natural setting.

Some examples of qualitative research questions are provided, such as what an experience feels like, how people talk about something, how they make sense of an experience, and how events unfold for people.

Research following a qualitative approach is exploratory and seeks to explain ‘how’ and ‘why’ a particular phenomenon, or behavior, operates as it does in a particular context. It can be used to generate hypotheses and theories from the data.

Qualitative Methods

There are different types of qualitative research methods, including diary accounts, in-depth interviews , documents, focus groups , case study research , and ethnography.

The results of qualitative methods provide a deep understanding of how people perceive their social realities and in consequence, how they act within the social world.

The researcher has several methods for collecting empirical materials, ranging from the interview to direct observation, to the analysis of artifacts, documents, and cultural records, to the use of visual materials or personal experience. Denzin and Lincoln (1994, p. 14)

Here are some examples of qualitative data:

Interview transcripts : Verbatim records of what participants said during an interview or focus group. They allow researchers to identify common themes and patterns, and draw conclusions based on the data. Interview transcripts can also be useful in providing direct quotes and examples to support research findings.

Observations : The researcher typically takes detailed notes on what they observe, including any contextual information, nonverbal cues, or other relevant details. The resulting observational data can be analyzed to gain insights into social phenomena, such as human behavior, social interactions, and cultural practices.

Unstructured interviews : generate qualitative data through the use of open questions. This allows the respondent to talk in some depth, choosing their own words. This helps the researcher develop a real sense of a person’s understanding of a situation.

Diaries or journals : Written accounts of personal experiences or reflections.

Notice that qualitative data could be much more than just words or text. Photographs, videos, sound recordings, and so on, can be considered qualitative data. Visual data can be used to understand behaviors, environments, and social interactions.

Qualitative Data Analysis

Qualitative research is endlessly creative and interpretive. The researcher does not just leave the field with mountains of empirical data and then easily write up his or her findings.

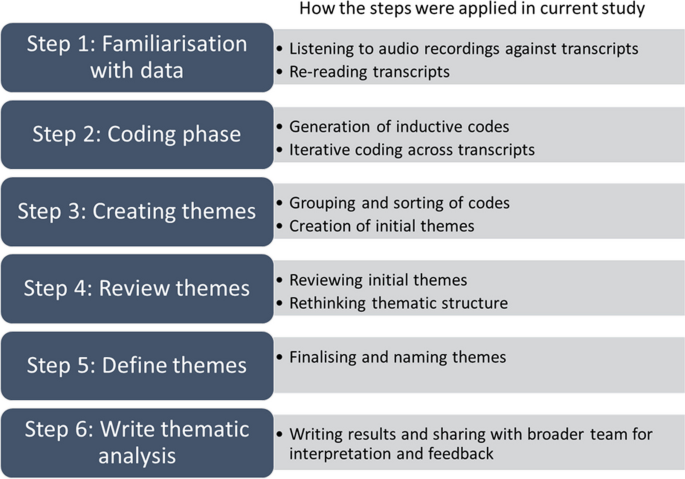

Qualitative interpretations are constructed, and various techniques can be used to make sense of the data, such as content analysis, grounded theory (Glaser & Strauss, 1967), thematic analysis (Braun & Clarke, 2006), or discourse analysis.

For example, thematic analysis is a qualitative approach that involves identifying implicit or explicit ideas within the data. Themes will often emerge once the data has been coded.

Key Features

- Events can be understood adequately only if they are seen in context. Therefore, a qualitative researcher immerses her/himself in the field, in natural surroundings. The contexts of inquiry are not contrived; they are natural. Nothing is predefined or taken for granted.

- Qualitative researchers want those who are studied to speak for themselves, to provide their perspectives in words and other actions. Therefore, qualitative research is an interactive process in which the persons studied teach the researcher about their lives.

- The qualitative researcher is an integral part of the data; without the active participation of the researcher, no data exists.

- The study’s design evolves during the research and can be adjusted or changed as it progresses. For the qualitative researcher, there is no single reality. It is subjective and exists only in reference to the observer.

- The theory is data-driven and emerges as part of the research process, evolving from the data as they are collected.

Limitations of Qualitative Research

- Because of the time and costs involved, qualitative designs do not generally draw samples from large-scale data sets.

- The problem of adequate validity or reliability is a major criticism. Because of the subjective nature of qualitative data and its origin in single contexts, it is difficult to apply conventional standards of reliability and validity. For example, because of the central role played by the researcher in the generation of data, it is not possible to replicate qualitative studies.

- Also, contexts, situations, events, conditions, and interactions cannot be replicated to any extent, nor can generalizations be made to a wider context than the one studied with confidence.

- The time required for data collection, analysis, and interpretation is lengthy. Analysis of qualitative data is difficult, and expert knowledge of an area is necessary to interpret qualitative data. Great care must be taken when doing so, for example, looking for mental illness symptoms.

Advantages of Qualitative Research

- Because of close researcher involvement, the researcher gains an insider’s view of the field. This allows the researcher to find issues that are often missed (such as subtleties and complexities) by the scientific, more positivistic inquiries.

- Qualitative descriptions can be important in suggesting possible relationships, causes, effects, and dynamic processes.

- Qualitative analysis allows for ambiguities/contradictions in the data, which reflect social reality (Denscombe, 2010).

- Qualitative research uses a descriptive, narrative style; this research might be of particular benefit to the practitioner as she or he could turn to qualitative reports to examine forms of knowledge that might otherwise be unavailable, thereby gaining new insight.

What Is Quantitative Research?

Quantitative research involves the process of objectively collecting and analyzing numerical data to describe, predict, or control variables of interest.

The goals of quantitative research are to test causal relationships between variables , make predictions, and generalize results to wider populations.

Quantitative researchers aim to establish general laws of behavior and phenomenon across different settings/contexts. Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Quantitative Methods

Experiments typically yield quantitative data, as they are concerned with measuring things. However, other research methods, such as controlled observations and questionnaires , can produce both quantitative information.

For example, a rating scale or closed questions on a questionnaire would generate quantitative data as these produce either numerical data or data that can be put into categories (e.g., “yes,” “no” answers).

Experimental methods limit how research participants react to and express appropriate social behavior.

Findings are, therefore, likely to be context-bound and simply a reflection of the assumptions that the researcher brings to the investigation.

There are numerous examples of quantitative data in psychological research, including mental health. Here are a few examples:

Another example is the Experience in Close Relationships Scale (ECR), a self-report questionnaire widely used to assess adult attachment styles .

The ECR provides quantitative data that can be used to assess attachment styles and predict relationship outcomes.

Neuroimaging data : Neuroimaging techniques, such as MRI and fMRI, provide quantitative data on brain structure and function.

This data can be analyzed to identify brain regions involved in specific mental processes or disorders.

For example, the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) is a clinician-administered questionnaire widely used to assess the severity of depressive symptoms in individuals.

The BDI consists of 21 questions, each scored on a scale of 0 to 3, with higher scores indicating more severe depressive symptoms.

Quantitative Data Analysis

Statistics help us turn quantitative data into useful information to help with decision-making. We can use statistics to summarize our data, describing patterns, relationships, and connections. Statistics can be descriptive or inferential.

Descriptive statistics help us to summarize our data. In contrast, inferential statistics are used to identify statistically significant differences between groups of data (such as intervention and control groups in a randomized control study).

- Quantitative researchers try to control extraneous variables by conducting their studies in the lab.

- The research aims for objectivity (i.e., without bias) and is separated from the data.

- The design of the study is determined before it begins.

- For the quantitative researcher, the reality is objective, exists separately from the researcher, and can be seen by anyone.

- Research is used to test a theory and ultimately support or reject it.

Limitations of Quantitative Research

- Context: Quantitative experiments do not take place in natural settings. In addition, they do not allow participants to explain their choices or the meaning of the questions they may have for those participants (Carr, 1994).

- Researcher expertise: Poor knowledge of the application of statistical analysis may negatively affect analysis and subsequent interpretation (Black, 1999).

- Variability of data quantity: Large sample sizes are needed for more accurate analysis. Small-scale quantitative studies may be less reliable because of the low quantity of data (Denscombe, 2010). This also affects the ability to generalize study findings to wider populations.

- Confirmation bias: The researcher might miss observing phenomena because of focus on theory or hypothesis testing rather than on the theory of hypothesis generation.

Advantages of Quantitative Research

- Scientific objectivity: Quantitative data can be interpreted with statistical analysis, and since statistics are based on the principles of mathematics, the quantitative approach is viewed as scientifically objective and rational (Carr, 1994; Denscombe, 2010).

- Useful for testing and validating already constructed theories.

- Rapid analysis: Sophisticated software removes much of the need for prolonged data analysis, especially with large volumes of data involved (Antonius, 2003).

- Replication: Quantitative data is based on measured values and can be checked by others because numerical data is less open to ambiguities of interpretation.

- Hypotheses can also be tested because of statistical analysis (Antonius, 2003).

Antonius, R. (2003). Interpreting quantitative data with SPSS . Sage.

Black, T. R. (1999). Doing quantitative research in the social sciences: An integrated approach to research design, measurement and statistics . Sage.

Braun, V. & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology . Qualitative Research in Psychology , 3, 77–101.

Carr, L. T. (1994). The strengths and weaknesses of quantitative and qualitative research : what method for nursing? Journal of advanced nursing, 20(4) , 716-721.

Denscombe, M. (2010). The Good Research Guide: for small-scale social research. McGraw Hill.

Denzin, N., & Lincoln. Y. (1994). Handbook of Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks, CA, US: Sage Publications Inc.

Glaser, B. G., Strauss, A. L., & Strutzel, E. (1968). The discovery of grounded theory; strategies for qualitative research. Nursing research, 17(4) , 364.

Minichiello, V. (1990). In-Depth Interviewing: Researching People. Longman Cheshire.

Punch, K. (1998). Introduction to Social Research: Quantitative and Qualitative Approaches. London: Sage

Further Information

- Designing qualitative research

- Methods of data collection and analysis

- Introduction to quantitative and qualitative research

- Checklists for improving rigour in qualitative research: a case of the tail wagging the dog?

- Qualitative research in health care: Analysing qualitative data

- Qualitative data analysis: the framework approach

- Using the framework method for the analysis of

- Qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research

- Content Analysis

- Grounded Theory

- Thematic Analysis

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Qualitative Data Collection & Analysis Methods

59 Strengths and Weaknesses of Qualitative Interviews

As the preceding sections have suggested, qualitative interviews are an excellent way to gather detailed information. Whatever topic is of interest to the researcher employing this method can be explored in much more depth than with almost any other method. Not only are participants given the opportunity to elaborate in a way that is not possible with other methods such as survey research, but they also are able share information with researchers in their own words and from their own perspectives rather than being asked to fit those perspectives into the perhaps limited response options provided by the researcher. And because qualitative interviews are designed to elicit detailed information, they are especially useful when a researcher’s aim is to study social processes, or the “how” of various phenomena. Yet another, and sometimes overlooked, benefit of qualitative interviews that occurs in person is that researchers can make observations beyond those that a respondent is orally reporting. A respondent’s body language, and even her or his choice of time and location for the interview, might provide a researcher with useful data.

Of course, all these benefits do not come without some drawbacks. As with quantitative survey research, qualitative interviews rely on respondents’ ability to accurately and honestly recall whatever details about their lives, circumstances, thoughts, opinions, or behaviours are being asked about. Further, as you may have already guessed, qualitative interviewing is time intensive and can be quite expensive. Creating an interview guide, identifying a sample, and conducting interviews are just the beginning. Transcribing interviews is labour intensive—and that is before coding even begins. It is also not uncommon to offer respondents some monetary incentive or thank-you for participating. Keep in mind that you are asking for more of the participants’ time than if you would have simply mailed them a questionnaire containing closed-ended questions. Conducting qualitative interviews is not only labour intensive but also emotionally taxing. Researchers embarking on a qualitative interview project, with a subject that is sensitive in nature, should keep in mind their own abilities to listen to stories that may be difficult to hear.

Text Attributions

- This chapter is an adaptation of Chapter 9.2 in Principles of Sociological Inquiry , which was adapted by the Saylor Academy without attribution to the original authors or publisher, as requested by the licensor. © Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 License .

An Introduction to Research Methods in Sociology Copyright © 2019 by Valerie A. Sheppard is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Qualitative Research: Strengths and Weakness Coursework

Biggest ethical dilemma faced by qualitative researchers.

The biggest ethical dilemma in qualitative research is the researchers’ responsibility for disclosure of information. The decision on whether to disclose information to any interested party to research or even to conceal information from concerned individuals and groups forms the basis of the dilemma. Every research activity is aimed at finding solutions and researchers’ interest will be to find the necessary information. As a result, there may be a need to conceal some information to ensure a smooth research process. Similarly, the results of the research might be of public interest and prompt for disclosure, to the compromise of a group’s interest.

Concealing information or even the researcher’s identity has in the past been a tool for the success of major research activities. Similarly, participants in research are supposed to be informed of the nature of the research before they can consent to be part of such activities. Further, the guarantee of privacy should be offered to the participants before the research. Full disclosure of the extent of confidentiality should also be made before the commencement of the research. A researcher is therefore expected either to consider the success of the research at the expense of ethics of disclosure or to prioritize ethics (Berg and Lune, 2011).

Primary reasons for using qualitative research and questions addressed by qualitative research

Qualitative research is aimed at investigations on existing relationships. Every research initiative will, therefore, be based on goals and reasons for making conclusions and recommendations. As Flick and Steinke explain, the major reasons for qualitative research are “description, a test of hypothesis and theory development” (2004, p. 150). This is because qualitative research activities are explorative. They, as a result, seek to describe relationships, investigate the significance of such relationships, and develop a basis for explaining the identified or existing relationships.

A research initiative to investigate trends in the prevalence of AIDS rates across age groups may, for example, be undertaken with the objective of exploring descriptive statistics such as mean, mode, and median across the considered age groups. Similarly, investigating trends among or within the groups may call for a test of hypothesis for establishing confidence through tests of significance on investigated trends. Qualitative research, through validating hypothesis, is also used as a basis for establishing theories (Flick and Steinke, 2004).

Since research questions offer directions to exploring research objectives, they are supposed to be aligned to the objectives and reasons for the particular research. Qualitative research, therefore, addresses questions on descriptive statistics, tests of significance and theory development (Flick and Steinke, 2004)

Triangulation of methods and their benefits

Triangulation of methods refers to the application of many approaches towards establishing findings of the research. The method is based on the concept that the application of many methods yields more accurate conclusions. The triangulation concept is derived from surveying methods in which many lines are used in the estimation of points. The concept is therefore mapped onto statistical qualitative research to use different approaches such as sampling techniques, analytical approaches, and diversification of samples in research. Triangulation of methods may also be understood in its literal meaning as the use of a variety of methods in research activity (Berg and Lune, 2011).

There exist a variety of classes of triangulation. Data triangulation, for instance, refers to the use of approaches such as “time, space, and person” (Berg and Lune, 2011, p. 7). While time triangulation refers to the consideration of data from different time frames, space triangulation refers to physical or geographical consideration and person triangulations consider the nature and type of sample used in research. Other classes include “investigator, theory, and methodological triangulation” (Berg and Lune, 2011, p. 7). The benefits of triangulations are therefore its broader scope of research and a resultant accuracy in results and conclusions (Berg and Lune, 2011).

Sampling strategies for qualitative research

Sampling strategies form one of the distinctions between qualitative and quantitative research approaches. The most commonly used sampling strategies in qualitative research are “criterion-based” sampling and “theoretical sampling” (Ritchie and Lewis, 2003, p. 78, 80). Criterion, as a basis for sampling, is used in cases where the participants in the research posses defined properties that are relevant to the research.

The main objective of this strategy is to obtain adequate representation through the selected sample. An element will, for example, be selected to represent a particular geographical area, group, or a behavioral characteristic. Criterion based sampling is further divided into several classes which include “homogeneous sampling, heterogeneous sampling, extreme case sampling, intensive sampling, typical case sampling, stratified purposive sampling, and critical case sampling” (Ritchie and Lewis, 2003, p. 79, 80).

Since criterion-based sampling relies on the purpose of the research, the particular sampling approach for used is identified before the commencement of the research, and the decision is usually based on the objectives of the research. The theoretical sampling strategy is on the other hand based on the capacity of the participants to make significant contributions to the results of the research (Ritchie and Lewis, 2003)

Strengths and weakness of qualitative research

Qualitative research has both strengths and weaknesses. One of the strengths is its extensive understanding that it offers to the subject of research. The explorative nature of qualitative research that involves extensive analysis of background information as well as collected data offers a basis for understanding. Further, a summary of the research results through descriptive statistics facilitates a deeper understanding.

The nature of the research that induces confidence through the reliable test of hypothesis also draws interest for closer attention and understanding. Another advantage of qualitative research is its flexible nature. The numerous strategies and techniques at different stages of research are easily interchangeable. As a result, approaches and methods can be substituted at any stage of the research (Rubbin and Babbie, 2009).

Weaknesses that have been associated with qualitative research include generalization in presentation and biasness due to formed opinion or conflict of interest on the part of a researcher. Generalization of reports, for instance, leads to loss of precision especially in cases where varying opinions exist across samples. Similarly, a researcher may be biased at any point in the research to influence an outcome. Biasness can be induced during sample selection or data collection stages (Rubbin and Babbie, 2009).

Possible problems faced in qualitative research

There are several problems faced in qualitative research. These problems range from the research process to the research environment. One of the already identified problems is the researcher’s ability to “adopt and adapt” to different research strategies and methods (Barbour, 2007). The main reason why the availability of many options is a challenge to many researchers is the intersection of concepts in research strategies. This particularly makes it difficult for a researcher to identify the most suitable approach to use.

Another significant challenge in qualitative research is a conflict of interest in which a researcher’s motive shifts to exalting himself instead of paying attention to the subject of research. When attention is shifted, the chances of biasness become higher. The financial interest of researchers has also developed to be a major challenge in qualitative research. This is particularly encountered in sponsored research activities where a researcher is dependent on and is subjected to forces from other interested parties. As a result, a researcher may be influenced by compromising and being biased to favor the parties. Researchers are therefore expected to be strong enough and independent to shun down such forces leading to biasness (Barbour, 2007).

Barbour, R. (2007). Introducing Qualitative Research: A Student’s Guide to the Craft of Doing Qualitative Research. London, UK: SAGE.

Berg, B., and Lune, H. (2011). Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences . New York, NY: Allyn & Bacon.

Flick, U., Kardorff, E. and Steinke, I. (2004). A companion to qualitative research. London, UK: SAGE.

Ritchie, J. and Lewis, J. (2003). Qualitative research practice: a guide for social science students and researchers. London, UK: SAGE.

Rubbin, A. and Babbie, E. (2009). Essential Research Methods for Social Work. Belmont, CA: Cengage Learning.

- Chicago (A-D)

- Chicago (N-B)

IvyPanda. (2020, July 14). Qualitative Research: Strengths and Weakness. https://ivypanda.com/essays/qualitative-research-strengths-and-weakness/

"Qualitative Research: Strengths and Weakness." IvyPanda , 14 July 2020, ivypanda.com/essays/qualitative-research-strengths-and-weakness/.

IvyPanda . (2020) 'Qualitative Research: Strengths and Weakness'. 14 July.

IvyPanda . 2020. "Qualitative Research: Strengths and Weakness." July 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/qualitative-research-strengths-and-weakness/.

1. IvyPanda . "Qualitative Research: Strengths and Weakness." July 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/qualitative-research-strengths-and-weakness/.

Bibliography

IvyPanda . "Qualitative Research: Strengths and Weakness." July 14, 2020. https://ivypanda.com/essays/qualitative-research-strengths-and-weakness/.

- Triangulation, Member Check, Structural Coherence

- "The Methodological Triangulation…" by Andoy et al.

- Mixed Method in Motivation and Video Gaming Study

- Autism: Qualitative Research Design

- Elimination of Gender Biasness in the Workplace

- Biasness: American Society vs. Saudi Society

- Research Procedure and Strategies for Validity and Reliability

- Multi-Method Research Design

- Data Collection and Analysis

- White Privilege and Racism in American Society

- Objectivist and Subjectivist View of Research

- Academic Research and Practice Relationship

- Quantitative Research Methods' Types

- Tobit Model in Econometrics

- Applied Research Project: Meta-Analysis

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- v.7(5); 2020 Sep

Qualitative evaluation in nursing interventions—A review of the literature

Kristine rørtveit.

1 Department of Research, Nursing and Healthcare Research Group, Stavanger University Hospital, Stavanger Norway

Britt Saetre Hansen

Kirsten lode, elisabeth severinsson, associated data.

To identify and synthesize qualitative evaluation methods used in nursing interventions.

A systematic qualitative review with a content analysis. Four databases were used: MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Embase and CINAHL using pre‐defined terms. The included papers were published from 2014–2018.

We followed the guidelines of Dixon‐Woods et al., Sandelowski and Barroso, the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme qualitative checklist and The Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research Approach.

Of 103 papers, 15 were eligible for inclusion. The main theme Challenging complexity by evaluating qualitatively described processes and characteristics of qualitative evaluation. Two analytic themes emerged: Evaluating the implementation process and Evaluating improvements brought about by the programme.

Different qualitative evaluation methods in nursing are a way of documenting knowledge that is difficult to illuminate in natural settings and make an important contribution when determining the pros and cons of an intervention.

1. INTRODUCTION

During the last decade, there has been an ongoing discussion on the topic of developing and evaluating complex nursing interventions. Nursing interventions can be evaluated qualitatively, as this method enhances the significance of clinical trials and emphasizes the distinctive work and outcomes of nursing care (Sandelowski, 1996 ). However, there are few examples of detailed methodological strategies for doing so (Schumacher et al., 2005 ). Evaluation is a positive pursuit as it provides an organization with knowledge of how to improve or verify the value of services and how to determine which elements are strong and which are in need of improvement (Stufflebeam & Shinkfield, 2007 ). Nurses should therefore develop and implement strategies aimed at creating professional practice, and furthermore, such strategies should include designing and implementing performance measurement systems (McDavid & Huse, 2006 ). Morse, Penrod, and Hupcey ( 2000 ) describes Qualitative Outcome Analysis (QOA) as a method for qualitatively identifying intervention strategies and evaluating the implementation outcomes of patient‐oriented interventions.

1.1. Background

Clinical nursing is complex, and nurses need to understand the complexity of evaluation to improve their practice. The term “complex intervention” is widely used in the academic health literature to describe both health service and public health interventions. Complex interventions are defined as consisting of several components, which can act either independently or interdependently (Campbell et al., 2007 ; Mohler, Bartoszek, Kopke, & Meyer, 2012 , p. 455). A complex intervention is characterized by several interacting components in several dimensions such as the behaviour required by the persons involved, the number of groups or levels in the organization, variability of outcomes and/or the degree of intervention flexibility (Craig et al., 2008 ).