Soldiers of my Old Guard: I bid you farewell. For twenty years I have constantly accompanied you on the road to honor and glory. In these latter times, as in the days of our prosperity, you have invariably been models of courage and fidelity. With men such as you our cause could not be lost; but the war would have been interminable; it would have been civil war, and that would have entailed deeper misfortunes on France. I have sacrificed all of my interests to those of the country. I go, but you, my friends, will continue to serve France. Her happiness was my only thought. It will still be the object of my wishes. Do not regret my fate; if I have consented to survive, it is to serve your glory. I intend to write the history of the great achievements we have performed together. Adieu, my friends. Would I could press you all to my heart.

Napoleon Bonaparte - April 20, 1814

Post-note: Following this, Napoleon was sent into exile on the little island of Elba off the coast of Italy. But ten months later, in March of 1815, he escaped back into France. Accompanied by a thousand men from his Old Guard he marched toward Paris and gathered an army of supporters along the way.

Once again, Napoleon assumed the position of Emperor, but it lasted only a 100 days until the battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815, where he was finally defeated by the combined English and Prussian armies.

A month later he was sent into exile on the island of St. Helena off the coast of Africa. On May 5, 1821, the former vain-glorious Emperor died alone on the tiny island abandoned by everyone. In 1840 his body was taken back to France and buried in Paris.

The History Place - Great Speeches Collection

The History Place - YouTube Channel

It follows the French full text transcript of Napoleon's Farewell to the Imperial Guard, his bodyguards, delivered in the Cour du Cheval Blanc , the courtyard of Cheval-Blanc, at the Chateau de Fontainebleau, which is located about 40 miles or 65 km south-southeast of Paris. The speech was given on April 20, 1814.

Je vous fais mes adieux.

Depuis vingt ans, je vous ai trouvés constamment sur le chemin de l’honneur et de la gloire. Dans ces derniers temps, comme dans ceux de notre prospérité, vous n’avez cessé d’être des modèles de bravoure et de fidélité.

Avec des hommes tels que vous, notre cause n’était pas perdue. Mais la guerre était interminable ; c’eut été la guerre civile, et la France n’en serait devenue que plus malheureuse. J’ai donc sacrifié tous nos intérêts à ceux de la patrie ; je pars. Vous, mes amis, continuez de servir la France.

Son bonheur était mon unique pensée ; il sera toujours l’objet de mes voeux ! Ne plaignez pas mon sort ; si j’ai consenti à me survivre, c’est pour servir encore à notre gloire ; je veux écrire les grandes choses que nous avons faites ensemble !

Adieu, mes enfants ! je voudrais vous presser tous sur mon coeur ; que j’embrasse au moins votre drapeau ! [Après avoir serré dans ses bras le général Petit, et embrassé le drapeau, Napoléon reprend :] Adieu encore une fois, mes vieux compagnons !

Que ce dernier baiser passe dans vos coeurs !

More History

We will keep fighting for all libraries - stand with us!

Internet Archive Audio

- This Just In

- Grateful Dead

- Old Time Radio

- 78 RPMs and Cylinder Recordings

- Audio Books & Poetry

- Computers, Technology and Science

- Music, Arts & Culture

- News & Public Affairs

- Spirituality & Religion

- Radio News Archive

- Flickr Commons

- Occupy Wall Street Flickr

- NASA Images

- Solar System Collection

- Ames Research Center

- All Software

- Old School Emulation

- MS-DOS Games

- Historical Software

- Classic PC Games

- Software Library

- Kodi Archive and Support File

- Vintage Software

- CD-ROM Software

- CD-ROM Software Library

- Software Sites

- Tucows Software Library

- Shareware CD-ROMs

- Software Capsules Compilation

- CD-ROM Images

- ZX Spectrum

- DOOM Level CD

- Smithsonian Libraries

- FEDLINK (US)

- Lincoln Collection

- American Libraries

- Canadian Libraries

- Universal Library

- Project Gutenberg

- Children's Library

- Biodiversity Heritage Library

- Books by Language

- Additional Collections

- Prelinger Archives

- Democracy Now!

- Occupy Wall Street

- TV NSA Clip Library

- Animation & Cartoons

- Arts & Music

- Computers & Technology

- Cultural & Academic Films

- Ephemeral Films

- Sports Videos

- Videogame Videos

- Youth Media

Search the history of over 866 billion web pages on the Internet.

Mobile Apps

- Wayback Machine (iOS)

- Wayback Machine (Android)

Browser Extensions

Archive-it subscription.

- Explore the Collections

- Build Collections

Save Page Now

Capture a web page as it appears now for use as a trusted citation in the future.

Please enter a valid web address

- Donate Donate icon An illustration of a heart shape

Napoleon's addresses; selections from the proclamations, speeches and correspondance of Napoleon Bonaparte;

Bookreader item preview, share or embed this item, flag this item for.

- Graphic Violence

- Explicit Sexual Content

- Hate Speech

- Misinformation/Disinformation

- Marketing/Phishing/Advertising

- Misleading/Inaccurate/Missing Metadata

![[WorldCat (this item)] [WorldCat (this item)]](https://archive.org/images/worldcat-small.png)

plus-circle Add Review comment Reviews

2,259 Views

4 Favorites

DOWNLOAD OPTIONS

For users with print-disabilities

IN COLLECTIONS

Uploaded by Melissa.D on June 25, 2010

SIMILAR ITEMS (based on metadata)

April 22, 1796 (to the army.) Soldiers! In fifteen days you have won six victories, captured twenty-one flags, fifty-five guns, several fortresses, conquered the richest part of Piedmont; you have made 15,000 prisoners; you have killed or wounded nearly 10,000 men. Until now you have fought for barren rocks. Lacking everything, you have accomplished everything. You have won battles without cannon, crossed rivers without bridges, made forced marches without boots, bivouacked without brandy, and often without bread. Only the phalanx of the Republic, only the soldiers of Liberty, could endure the things that you have suffered. But, soldiers, you have really done nothing, if there still lies a task before you. As yet, neither Milan nor Turin is yours. Our country has the right to expect great things of you; will you be worthy of that trust? There are more battles before you, more cities to capture, more rivers to cross. You all burn to carry forward the glory of the French people; to dictate a glorious peace; and to be able, when you return to your villages, to exclaim with pride: "I belonged to the conquering army of Italy!" Friends, that conquest, I promise, shall be yours; but there is a condition you must swear to observe: to respect the people you are liberating; to repress horrible pillage. All plunderers will be shot without mercy. People of Italy, the French army is here to break your chains; you may greet it with confidence. June 17, 1800 (on observing prisoners of war who recognized him) Many began to shout, with apparent enthusiasm: "Vive Bonaparte!" What a thing is imagination! Here are men who don't know me, who have never seen me, but who only knew of me, and they are moved by my presence, they would do anything for me! And this same incident arises in all centuries and in all countries! Such is fanaticism! Yes, imagination rules the world. The defect of our modern institutions is that they do not speak to the imagination. By that alone can man be governed; without it he is but a brute. July 4, 1800 I! a royal maggot! I am a soldier, I come from the people, I have made myself! Am I to be compared with Louis XVI? I listen to everybody, but my own mind is my only counsellor. There are some men who have done France more harm than the wildest revolutionaries, - - the talkers, and the rationalists. Vague and false thinkers, a few lessons of geometry would do them good! My policy is to govern men as the great number wish to be governed. That, I think, is the way to recognise the sovereignty of the people. March 21, 1804 (on the execution of the Duke d'Enghien for treason) I will respect the judgment of public opinion when it is well founded; but when capricious it must be met with contempt. I have behind me the will of the nation and an army of 500,000 men. With that I can command respect for the Republic. I could have had the Duke d'Enghien shot publicly; and if I have not done so, I held back not from fear, but to prevent the secret adherents of his House from breaking out and ruining themselves. They have kept quiet; it is all I ask of them. March 22, 1804 These people wanted an upheaval in France, and by killing me to kill the Revolution; it has been for me to defend and to avenge it. I have shown what it can do. The Duke d'Enghien was a conspirator just like any other, and it was necessary to treat him as any other might be treated. May 14, 1804 (a month before he made himself Emperor) The General Councils of Departments, the Electoral Colleges, and all the great Bodies of the State, demand that an end should be made of the hopes of the Bourbons by securing the Republic from the upheavals of elections and the uncertainty attending the life of an individual. May 15, 1804 It is not as a general that I rule, but because the nation believes I have the civilian qualifications for governing. My system is quite simple. It has seemed to me that under the circumstances the thing to do was to centralize power and increase the authority of the Government, so as to constitute the Nation. I am the constituent power. I can best compare a constitution to a ship; if you allow the wind to fill your sails, you go you know not whither, according to the wind that drives you; but if you make use of the rudder, you can go to Martinique with a wind that is driving you to San Domingo. No constitution has remained fixed. Change is governed by men and by circumstances. If an overstrong government is undesirable, a weak one is much worse. November 4, 1804 To reign in France, one must be born great, have been seen in childhood in a palace, surrounded with guards, or else be a man capable of raising himself above all others. My mistress is power; I have done too much to conquer her to let her be snatched away from me. Although it may be said that power came to me of its own accord, yet I know what labour, what sleepless nights, what scheming, it has involved. December 27, 1804 Deputies of the Departments to the Legislative Body, Tribunes, and Members of the Council of State, I have come among you to preside over your opening session. I have sought to lend a more imposing dignity to your labours. Prince, magistrates, soldiers, citizens, each in his own sphere, will have but one aim, the interests of the country. If this throne, to which Providence and the will of the people have called me, is precious in my eyes, it is for the sole reason that by it alone can the most precious rights of the French nation be preserved. Without a strong and paternal government, France would have to fear a return of the evils from which she once suffered. Weakness in the executive power is the greatest calamity of nations. As soldier, or First Consul, I had but one purpose; as Emperor, I have none other: the prosperity of France. May 22, 1805 (to Count Fouché, Minister of Police) Have some articles written against Princess Dolgorouki, who is spreading scandalous and ridiculous reports in Rome. You probably know that she long lived with an actor, and that the diamonds she displays so ostentatiously were given her by Potemkin and are the price of her dishonour. You can get information about her, and make her a laughingstock. She poses for a clever woman; she is on friendly terms with the Queen of Naples, and, which is equally surprising, with Mme. de Sta�l. May 30, 1805 (to Count Fouché, Minister of Police) Have some caricatures made: an Englishman, his purse in his hand, begging the various Powers to accept his money, etc. That is the note to strike. Have printed in Holland that advices from Madeira state that Villeneuve met a convoy of 100 English merchantmen bound for India, and captured it. June 1, 1805 (to Count Fouché, Minister of Police) I read in a paper that a tragedy on Henry IV is to be played. The epoch is recent enough to excite political passions. The theatre must dip more into antiquity. Why not commission Raynouard to write a tragedy on the transition from primitive to less primitive man? A tyrant would be followed by the saviour of his country. The oratorio "Saul" is on precisely that text, - - a great man succeeding a degenerate king. March 3, 1817 (during his final years as an exile on the island of St. Helena) In spite of all the libels, I have no fear whatever about my fame. Posterity will do me justice. The truth will be known; and the good I have done will be compared with the faults I have committed. I am not uneasy as to the result. Had I succeeded, I would have died with the reputation of the greatest man that ever existed. As it is, although I have failed, I shall be considered as an extraordinary man: my elevation was unparalleled, because unaccompanied by crime. I have fought fifty pitched battles, almost all of which I have won. I have framed and carried into effect a code of laws that will bear my name to the most distant posterity. I raised myself from nothing to be the most powerful monarch in the world. Europe was at my feet. I have always been of opinion that the sovereignty lay in the people. In fact, the imperial government was a kind of republic. Called to the head of it by the voice of the nation, my maxim was, la carrière est ouverte aux talens without distinction of birth or fortune.

Question : What are the duties of Christians toward those who govern them, and what in particular are our duties towards Napoleon I, our emperor? Answer: Christians owe to the princes who govern them, and we in particular owe to Napoleon I, our emperor, love, respect, obedience, fidelity, military service, and the taxes levied for the preservation and defense of the empire and of his throne. We also owe him fervent prayers for his safety and for the spiritual and temporal prosperity of the state. Question: Why are we subject to all these duties toward our emperor? Answer: First, because God, who has created empires and distributes them according to his will, has, by loading our emperor with gifts both in peace and in war, established him as our sovereign and made him the agent of his power and his image upon earth. To honor and serve our emperor is therefore to honor and serve God himself. Secondly, because our Lord Jesus Christ himself, both by his teaching and his example, has taught us what we owe to our sovereign. Even at his very birth he obeyed the edict of Caesar Augustus; he paid the established tax; and while he commanded us to render to God those things which belong to God, he also commanded us to render unto Caesar those things which are Caesar's. Question: Are there not special motives which should attach us more closely to Napoleon I, our emperor? Answer: Yes, for it is he whom God has raised up in trying times to re-establish the public worship of the holy religion of our fathers and to be its protector; he has re-established and preserved public order by his profound and active wisdom; he defends the state by his mighty arm; he has become the anointed of the Lord by the consecration which he has received from the sovereign pontiff, head of the Church universal. Question: What must we think of those who are wanting in their duties toward our emperor? Answer: According to the apostle Paul, they are resisting the order established by God himself and render themselves worthy of eternal damnation.

Napoleon I's speech upon returning from exile

This translation appeared in William Jennings Bryan's 1906 book The World’s Famous Orations , Volume VII "Continental Europe", page 177. The speech was made on 21 March 1815 by Napoleon Bonaparte when reviewing his troops the day after his return to Paris during the Hundred Days.

SOLDIERS, behold the officers of battalion who have accompanied me in my misfortune: they are all my friends; they are dear to my heart. Every time I saw them, they represented to me the several regiments of the army. Among these six hundred brave men, there are soldiers of every regiment; all brought me back those great days whose memory is so dear to me, for all were covered with honorable scars received in those memorable battles. In loving them, it is you all, soldiers of the French army, that I loved.

They bring you back these eagles; let them be your rallying-point. In giving them to the Guard, I give them to the whole army. Treachery and untoward circumstances had wrapped them in a shroud; but, thanks to the French people and to you, they reappear resplendent in all their glory. Swear that they shall always be found when and wherever the interest of the country may call them! Let the traitors and those who would invade our territory, be never able to endure their gaze.

- French speeches

- Hundred Days

- Undated works

Navigation menu

- Go to content

- Go to search

- External websites

- Itineraries

- Napoleonic Pleasures

- Places, museums, monuments

- Press reviews

- Special Dossiers

- What’s On

- Bibliographies

- Biographies

- In pictures

- Napo FactFiles

- Quizzes up to 15

- Fondation Napoléon Digital Collection

- Libraries and Archives

- M. Lapeyre Library

- Napoleonica – Archives Online

- Napoleonic Digital Library

- Napoleonica. La Revue

- Thematic Bibliographies

- Newsletters

- Fondation Napoléon

- Support us: my Gift

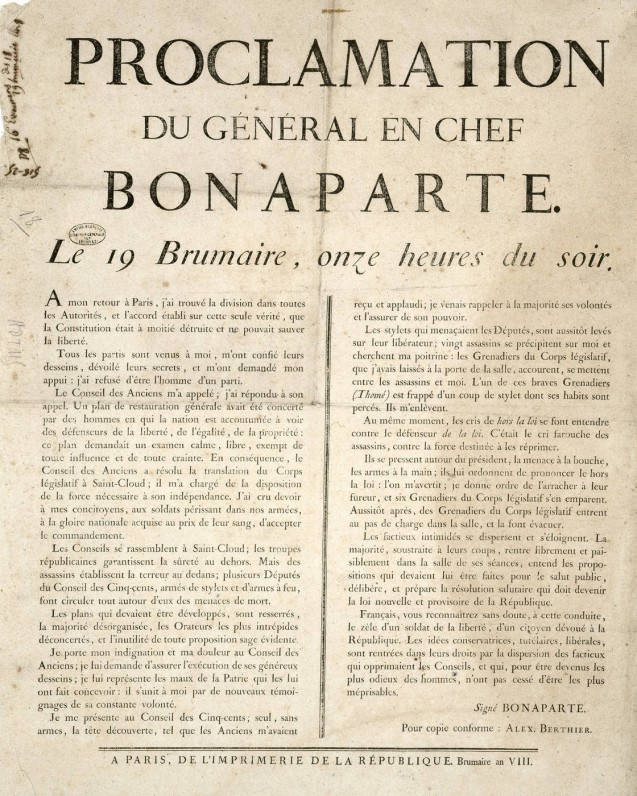

Bonaparte’s Proclamation to the French people on 19 Brumaire

On 19 brumaire an viii (10th november 1799), bonaparte made a proclamation to the french people. this translation of his speech featured in the annual register for the year 1799, published in london in 1801..

Proclamation of General Buonaparte.

Nov. 10, eleven oclock at night.

On my return to Paris, I found a division reigning amongst all the constituted authorities. There was no agreement but on this single point — that the constitution was half destroyed, and could by no means effect the salvation of our liberties. All the parties came to me, confided to me their designs, unveiled their secrets, and demanded my support. I refused to be a man of any party. The council of elders invited me, and I answered to their call. A plan of general restoration had been concerted by men, in whom the nation is accustomed to see the defender of its freedom and equality, and of property. This plan demanded a calm and liberal examination, free from every influence and every fear. The council of elders resolved, in consequence, that the sittings of the legislative body should be removed to St. Cloud, and charged me with the disposition of the force necessary to secure its independence. I owed it, my fellow-citizens, to the soldiers who are perishing in our armies, and to the national glory, acquired at the price of their blood, to accept of this command.

The councils being assembled at St. Cloud, the republican troops guaranteed their safety from without; but within, assassins had established the reign of terror. Several members of the council of five hundred, armed with poniards and fire-arms, circulated around them nothing but menaces of death. The plans which were about to be develloped [sic] were laid aside, the majority was disorganized, the most intrepid orators were disconcerted, and the inutility of every wise proposition was made evident. I bore my indignation and my grief to the council of elders, I demanded of them to ensure the execution of their generous designs. I represented to them the maladies of their country, from which those designs originated. They joined themselves with me, by giving new testimonies of their uniform wishes. I then repaired to the council of five hundred without arms, and my head uncovered, such as I had been received and applauded by the elders. I wished to recall to the majority their wishes, and to assure them of their power.

The poniards, which threatened the deputies, were instantly raised against their deliverer. Twenty assassins threw themselves upon me, and sought my breast. The grenadiers of the legislative body, whom I had left at the door of the hall, came up and placed themselves between me and my assassins. One of these brave grenadiers, named Thome, had his clothes struck through with a dagger. They succeeded in bearing me away. At this time the cry of “Outlaw!” was raised against the defender of the law. It was the ferocious cry of assassins against the force which was destined to restrain them. They pressed around the president, threatened him to his face, and, with arms in their hands, ordered him to decree me out of the protection of the law. Being informed of this circumstance, I gave orders to rescue him from their power, and six grenadiers of the legislative body brought him out of the hall. Immediately after the grenadiers of the legislative body entered at the pas de charge into the hall, and caused it to be evacuated. The factious were intimidated, and dispersed themselves.

The majority, released from their blows, entered freely and peaceably into the hall of sitting, heard the propositions which were made to them for the public safety deliberated, and prepared the salutary resolution which is to become the new and provisional law of the republic.

Frenchmen! you will recognize, without doubt, in this conduct, the zeal of a soldier of liberty, and of a citizen devoted to the republic. The ideas of preservation, protection, and freedom, immediately resumed their places on the dispersion of the faction who wished to oppress the councils, and who, in making themselves the most odious of men, never cease to be the most contemptible.

(Signed) BUONAPARTE. (Countersigned) BERTHIER.

Description and analysis of the proclamation:

Bonaparte produced his proclamation on the evening of 19 Brumaire An VIII (10 November 1799), and it marked a major first in political communication. The inclusion of the precise time and date on the document demonstrate the urgency felt at the time of its drafting as well as the sense of the historical significance of the events that had unfolded that day. Furthermore, that Bonaparte’s name features boldly in the letter head shows a return to a sort of official personalisation that had not been seen since the fall of the monarchy. While Bonaparte had not been Sieyès’s first choice of general to provide military support to his coup (Sieyès would have preferred Barthélémy Joubert, who had been killed at Novi on 15 August 1799), General Bonaparte now confirmed himself as a vital figure to the new regime. He took a revisionist approach when writing his proclamation and altered the truth in order to present himself as the saviour of the Republic. According to his version of events, it was he who saved his brother Lucien (the president of the assembly), when in fact he had almost caused the coup to fail by losing his temper in front of the outraged deputies. The proclamation also indicated the principles the Consulate intended to adhere to. Emphasis of the values of liberty and equality, and on respect for the Republic, suggested direct continuity from the Revolution. However, the allusion to ‘preservation, protection, and freedom,’ was a subtle way of announcing the type of personal power that he now expected to wield. These elements of the proclamation would be consecrated by the Constitution of 22 Frimaire An VIII barely a month later.

- Return to top

- < Previous

Home > LAS > LAS Departments and Programs > French Program > Napoleon Translations > 6

Napoleon Translations

Title of translation.

Proclomations, Speeches and Letters of Napoleon Buonaparte During His Campaign of Egypt 1-8

Title of Original Work

Proclamations de Napoléon en Egypte

Author(s) of Translation

Trent Dailey-Chwalibog Brittany Gignac

Document Type

Translation

Date of Translation Publication

Original work publication date, translator's note.

The following texts form a series of letters, speeches, and official proclamations of Napoleon Bonaparte during his campaign in Egypt at the turn of the 19th century. Bonaparte, with the title of commander-in chief, joined together both the French army and navy in 1798 to carry out this complex conquest. His intention was to seize Egypt, which was part of the Ottoman Empire, in order to create a French presence in the Middle East, and to protect French trade which was at the time being hurt by British relations with trade authorities in Egypt, the Mamluk Beys. One of the prime reasons for France agreeing to this near-impossible expedition was certainly to gain cultural enrichment from learning more about Middle Eastern life, but more so it was out of the fear that Napoleon's growing power was invoking in the French government. It was their hope that with the commander gone for several years, he would not only end in defeat, but would lose some of his credibility as an authority figure in France. After 3 years of countless defeats and exposure to the Bubonic Plague, the campaign did indeed prove to be unsuccessful. France gained no control over Egypt, nor of the British, yet Napoleon's reputation as a great military leader remained strong, due to the fact that during his campaign he formed his own newspaper that praised his efforts and was periodically sent back to France to inform the people of his so-called brilliant progress. Therefore, despite his failure in Egypt, he was still seen as admirable and was crowned Emperor only a few short years after. These 8 separate documents are all from the beginning of this legendary campaign, from an inspirational speech to his soldiers before leaving France, to the official statement issued to the Egyptian people after his first attacks against the Mamluk forces, the Battle of the Pyramids. The tone in each text never fails to be optimistic, compassionate, or encouraging, even in his proclamations warning Egyptian officials of his impending actions. This series of statements allows us to see the type of commanding officer that Napoleon Bonaparte truly was, where despite the fact that his personal greed for power was his driving force, he was capable of encouraging his troops and even the people he conquered to all be passionate for a common cause and to trust wholeheartedly in their leader.

Recommended Citation

Dailey-Chwalibog, Trent and Gignac, Brittany. (2009) Proclomations, Speeches and Letters of Napoleon Buonaparte During His Campaign of Egypt 1-8. https://via.library.depaul.edu/napoleon/6

Since April 11, 2013

Advanced Search Search Tips

- Notify me via email or RSS

Login and Notify

- Register/Login

About The Commons

- General Information/Policies

- University Library Homepage

- Collections

- Disciplines

Author Corner

At a glance.

- Top 10 Downloads of All Time

- 20 most recent additions

- Activity by year

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Napoleon Speeches

Farewell to the old guard.

Napoleon Speeches: Farewell to the Old Guard is the short address by Napoleon after his defeat in Russia. Eventually, because there was no support from Paris, he had to disband the last few loyal and elite soldiers.

Background of Napoleon Speeches: Farewell to the Old Guard

This address given in April 20, 1814 was a significant event in the reign of Napoleon. The Old Guard was his personal loyal and elite guard, intimidating soldiers that struck fear in the hearts of his enemies and inspired friendly troops.

After a defeat in Russia, there were only a few soldiers left in the Old Guard. Without the support from the Paris headquarters, Napoleon was forced to disband his personal guard.

Eventually, the Old guard was routed and defeated at the battle of Waterloo. This signified the end of the Guard and the fall of Napoleon.

Transcript of the Address to the Old Guard

Soldiers of my Old Guard: I bid you farewell. For twenty years I have constantly accompanied you on the road to honour and glory. In these latter times, as in the days of our prosperity, you have invariably been models of courage and fidelity. With men such as you our cause could not be lost; but the war would have been interminable; it would have been civil war, and that would have entailed deeper misfortunes on France.

I have sacrificed all of my interests to those of the country.

I go, but you, my friends, will continue to serve France. Her happiness was my only thought. It will still be the object of my wishes. Do not regret my fate; if I have consented to survive, it is to serve your glory. I intend to write the history of the great achievements we have performed together. Adieu, my friends. Would I could press you all to my heart.

If you would like more information on the leadership of Napoleon Bonaparte in my website, please visit Napoleon Leadership .

Return from Napoleon Speeches to Home Page

- History Classics

- Your Profile

- Find History on Facebook (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Twitter (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on YouTube (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on Instagram (Opens in a new window)

- Find History on TikTok (Opens in a new window)

- This Day In History

- History Podcasts

- History Vault

Napoleon Bonaparte

By: History.com Editors

Updated: April 24, 2023 | Original: November 9, 2009

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), also known as Napoleon I, was a French military leader and emperor who conquered much of Europe in the early 19th century. Born on the island of Corsica, Napoleon rapidly rose through the ranks of the military during the French Revolution (1789-1799). After seizing political power in France in a 1799 coup d’état, he crowned himself emperor in 1804. Shrewd, ambitious and a skilled military strategist, Napoleon successfully waged war against various coalitions of European nations and expanded his empire. However, after a disastrous French invasion of Russia in 1812, Napoleon abdicated the throne two years later and was exiled to the island of Elba. In 1815, he briefly returned to power in his Hundred Days campaign. After a crushing defeat at the Battle of Waterloo, he abdicated once again and was exiled to the remote island of Saint Helena, where he died at 51.

Napoleon’s Education and Early Military Career

Napoleon Bonaparte was born on August 15, 1769, in Ajaccio, on the Mediterranean island of Corsica. He was the second of eight surviving children born to Carlo Buonaparte (1746-1785), a lawyer, and Letizia Romalino Buonaparte (1750-1836). Although his parents were members of the minor Corsican nobility, the family was not wealthy. The year before Napoleon’s birth, France acquired Corsica from the city-state of Genoa, Italy. Napoleon later adopted a French spelling of his last name.

As a boy, Napoleon attended school in mainland France, where he learned the French language, and went on to graduate from a French military academy in 1785. He then became a second lieutenant in an artillery regiment of the French army. The French Revolution began in 1789, and within three years revolutionaries had overthrown the monarchy and proclaimed a French republic. During the early years of the revolution, Napoleon was largely on leave from the military and home in Corsica, where he became affiliated with the Jacobins, a pro-democracy political group. In 1793, following a clash with the nationalist Corsican governor, Pasquale Paoli (1725-1807), the Bonaparte family fled their native island for mainland France, where Napoleon returned to military duty.

In France, Napoleon became associated with Augustin Robespierre (1763-1794), the brother of revolutionary leader Maximilien Robespierre (1758-1794), a Jacobin who was a key force behind the Reign of Terror (1793-1794), a period of violence against enemies of the revolution. During this time, Napoleon was promoted to the rank of brigadier general in the army. However, after Robespierre fell from power and was guillotined (along with Augustin) in July 1794, Napoleon was briefly put under house arrest for his ties to the brothers.

In 1795, Napoleon helped suppress a royalist insurrection against the revolutionary government in Paris and was promoted to major general.

Did you know? In 1799, during Napoleon’s military campaign in Egypt, a French soldier named Pierre Francois Bouchard (1772-1832) discovered the Rosetta Stone. This artifact provided the key to cracking the code of Egyptian hieroglyphics, a written language that had been dead for almost 2,000 years.

Napoleon’s Rise to Power

Since 1792, France’s revolutionary government had been engaged in military conflicts with various European nations. In 1796, Napoleon commanded a French army that defeated the larger armies of Austria, one of his country’s primary rivals, in a series of battles in Italy. In 1797, France and Austria signed the Treaty of Campo Formio, resulting in territorial gains for the French.

The following year, the Directory, the five-person group that had governed France since 1795, offered to let Napoleon lead an invasion of England. Napoleon determined that France’s naval forces were not yet ready to go up against the superior British Royal Navy. Instead, he proposed an invasion of Egypt in an effort to wipe out British trade routes with India. Napoleon’s troops scored a victory against Egypt’s military rulers, the Mamluks, at the Battle of the Pyramids in July 1798; soon, however, his forces were stranded after his naval fleet was nearly decimated by the British at the Battle of the Nile in August 1798. In early 1799, Napoleon’s army launched an invasion of Ottoman Empire -ruled Syria , which ended with a failed siege of Acre, located in modern-day Israel . That summer, with the political situation in France marked by uncertainty, the ever-ambitious and cunning Napoleon opted to abandon his army in Egypt and return to France.

The Coup of 18 Brumaire

In November 1799, in an event known as the coup of 18 Brumaire, Napoleon was part of a group that successfully overthrew the French Directory.

The Directory was replaced with a three-member Consulate, and 5'7" Napoleon became first consul, making him France’s leading political figure. In June 1800, at the Battle of Marengo, Napoleon’s forces defeated one of France’s perennial enemies, the Austrians, and drove them out of Italy. The victory helped cement Napoleon’s power as first consul. Additionally, with the Treaty of Amiens in 1802, the war-weary British agreed to peace with the French (although the peace would only last for a year).

Napoleon worked to restore stability to post-revolutionary France. He centralized the government; instituted reforms in such areas as banking and education; supported science and the arts; and sought to improve relations between his regime and the pope (who represented France’s main religion, Catholicism), which had suffered during the revolution. One of his most significant accomplishments was the Napoleonic Code , which streamlined the French legal system and continues to form the foundation of French civil law to this day.

In 1802, a constitutional amendment made Napoleon first consul for life. Two years later, in 1804, he crowned himself emperor of France in a lavish ceremony at the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Paris.

Napoleon’s Marriages and Children

In 1796, Napoleon married Josephine de Beauharnais (1763-1814), a stylish widow six years his senior who had two teenage children. More than a decade later, in 1809, after Napoleon had no offspring of his own with Empress Josephine, he had their marriage annulled so he could find a new wife and produce an heir. In 1810, he wed Marie Louise (1791-1847), the daughter of the emperor of Austria. The following year, she gave birth to their son, Napoleon François Joseph Charles Bonaparte (1811-1832), who became known as Napoleon II and was given the title king of Rome. In addition to his son with Marie Louise, Napoleon had several illegitimate children.

The Reign of Napoleon I

From 1803 to 1815, France was engaged in the Napoleonic Wars, a series of major conflicts with various coalitions of European nations. In 1803, partly as a means to raise funds for future wars, Napoleon sold France’s Louisiana Territory in North America to the newly independent United States for $15 million, a transaction that later became known as the Louisiana Purchase .

In October 1805, the British wiped out Napoleon’s fleet at the Battle of Trafalgar . However, in December of that same year, Napoleon achieved what is considered to be one of his greatest victories at the Battle of Austerlitz, in which his army defeated the Austrians and Russians. The victory resulted in the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire and the creation of the Confederation of the Rhine.

Beginning in 1806, Napoleon sought to wage large-scale economic warfare against Britain with the establishment of the so-called Continental System of European port blockades against British trade. In 1807, following Napoleon’s defeat of the Russians at Friedland in Prussia, Alexander I (1777-1825) was forced to sign a peace settlement, the Treaty of Tilsit. In 1809, the French defeated the Austrians at the Battle of Wagram, resulting in further gains for Napoleon.

During these years, Napoleon reestablished a French aristocracy (eliminated in the French Revolution) and began handing out titles of nobility to his loyal friends and family as his empire continued to expand across much of western and central continental Europe.

Napoleon’s Downfall and First Abdication

In 1810, Russia withdrew from the Continental System. In retaliation, Napoleon led a massive army into Russia in the summer of 1812. Rather than engaging the French in a full-scale battle, the Russians adopted a strategy of retreating whenever Napoleon’s forces attempted to attack. As a result, Napoleon’s troops trekked deeper into Russia despite being ill-prepared for an extended campaign.

In September, both sides suffered heavy casualties in the indecisive Battle of Borodino. Napoleon’s forces marched on to Moscow, only to discover almost the entire population evacuated. Retreating Russians set fires across the city in an effort to deprive enemy troops of supplies. After waiting a month for a surrender that never came, Napoleon, faced with the onset of the Russian winter, was forced to order his starving, exhausted army out of Moscow. During the disastrous retreat, his army suffered continual harassment from a suddenly aggressive and merciless Russian army. Of Napoleon’s 600,000 troops who began the campaign, only an estimated 100,000 made it out of Russia.

At the same time as the catastrophic Russian invasion, French forces were engaged in the Peninsular War (1808-1814), which resulted in the Spanish and Portuguese, with assistance from the British, driving the French from the Iberian Peninsula. This loss was followed in 1813 by the Battle of Leipzig , also known as the Battle of Nations, in which Napoleon’s forces were defeated by a coalition that included Austrian, Prussian, Russian and Swedish troops. Napoleon then retreated to France, and in March 1814 coalition forces captured Paris.

On April 6, 1814, Napoleon, then in his mid-40s, was forced to abdicate the throne. With the Treaty of Fontainebleau, he was exiled to Elba, a Mediterranean island off the coast of Italy. He was given sovereignty over the small island, while his wife and son went to Austria.

HISTORY Vault: Napoleon Bonaparte: The Glory of France

Explore the extraordinary life and times of Napoleon Bonaparte, the great military genius who took France to unprecedented heights of power, and then brought it to its knees when his ego spun out of control.

Hundred Days Campaign and Battle of Waterloo

On February 26, 1815, after less than a year in exile, Napoleon escaped Elba and sailed to the French mainland with a group of more than 1,000 supporters. On March 20, he returned to Paris, where he was welcomed by cheering crowds. The new king, Louis XVIII (1755-1824), fled, and Napoleon began what came to be known as his Hundred Days campaign.

Upon Napoleon’s return to France, a coalition of allies–the Austrians, British, Prussians and Russians–who considered the French emperor an enemy began to prepare for war. Napoleon raised a new army and planned to strike preemptively, defeating the allied forces one by one before they could launch a united attack against him.

In June 1815, his forces invaded Belgium, where British and Prussian troops were stationed. On June 16, Napoleon’s troops defeated the Prussians at the Battle of Ligny. However, two days later, on June 18, at the Battle of Waterloo near Brussels, the French were crushed by the British, with assistance from the Prussians.

On June 22, 1815, Napoleon was once again forced to abdicate.

Napoleon’s Final Years

In October 1815, Napoleon was exiled to the remote, British-held island of Saint Helena, in the South Atlantic Ocean. He died there on May 5, 1821, at age 51, most likely from stomach cancer. (During his time in power, Napoleon often posed for paintings with his hand in his vest, leading to some speculation after his death that he had been plagued by stomach pain for years.) Napoleon was buried on the island despite his request to be laid to rest “on the banks of the Seine, among the French people I have loved so much.” In 1840, his remains were returned to France and entombed in a crypt at Les Invalides in Paris, where other French military leaders are interred.

Napoleon Bonaparte Quotes

- “The only way to lead people is to show them a future: a leader is a dealer in hope.”

- “Never interrupt your enemy when he is making a mistake.”

- “Envy is a declaration of inferiority.”

- “The reason most people fail instead of succeed is they trade what they want most for what they want at the moment.”

- “If you wish to be a success in the world, promise everything, deliver nothing.”

Sign up for Inside History

Get HISTORY’s most fascinating stories delivered to your inbox three times a week.

By submitting your information, you agree to receive emails from HISTORY and A+E Networks. You can opt out at any time. You must be 16 years or older and a resident of the United States.

More details : Privacy Notice | Terms of Use | Contact Us

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

A speech by Napoleon Bonaparte, the former Emperor of France and ruler of Europe, on April 20, 1814, as he bid farewell to the Old Guard after his failed invasion of Russia and defeat by the Allies. He expressed his gratitude and loyalty to the soldiers who had served him for twenty years and his wish for their glory. The speech was part of his farewell tour at Fontainebleau before he was exiled to Elba and then St. Helena.

Napoleon's Address to the Army at the Beginning of the Italian Campaign, March, 1796. "Soldiers, you are naked and ill-fed! Government owes you much and can give you nothing. The patience and courage you have shown in the midst of these rocks are admirable; but they gain you no renown; no glory results to you from your endurance.

A historical account of Napoleon's last words to his soldiers before leaving the Château de Fontainebleau on 20 April 1814, when he bid them farewell and kissed their flag. The speech was written by a French officer and published in a book in 1830.

It follows the French full text transcript of Napoleon's Farewell to the Imperial Guard, his bodyguards, delivered in the Cour du Cheval Blanc, the courtyard of Cheval-Blanc, at the Chateau de Fontainebleau, which is located about 40 miles or 65 km south-southeast of Paris. The speech was given on April 20, 1814.

A speech by from April 20, 1814, by Napoleon Bonaparte, after his failed invasion of Russia and defeat by the Allies.Napoleon Bonaparte's Farewell to the Old...

Speech of Abdication, April 2, 1814. Farewell to the Old Guard, April 20, 1814. Proclamation to the French People on His Return from Elba, March 5, 1815. Napoleon's Proclamation to the Army on His Return from Elba, March 5, 1815. Proclamation on the Anniversary of the Battles of Marengo and Friedland, June 14, 1815.

On March 30, 1814, Paris was captured by the Allies. Napoleon lost the support of most of his generals and was forced to abdicate on April 6, 1814. In the courtyard at Fontainebleau, Napoleon bid ...

125164 Napoleon I's speech following his abdication, to his soldiers at Fontainebleau Napoleon Bonaparte. SOLDIERS, I bid you farewell. For twenty years that we have been together your conduct has left me nothing to desire. I have always found you on the road to glory. All the powers of Europe have combined in arms against me.

A speech by from April 20, 1814, by Napoleon Bonaparte, after his failed invasion of Russia and defeat by the Allies. Soldiers of my Old Guard: I bid you farewell. For twenty years I have constantly accompanied you on the road to honor and glory. ... Napoleon Bonaparte - April 20, 1814 . This text is part of the Internet Modern History ...

Napoleon's addresses; selections from the proclamations, speeches and correspondance of Napoleon Bonaparte; ... Napoleon's addresses; selections from the proclamations, speeches and correspondance of Napoleon Bonaparte; by Napoleon I, Emperor of the French, 1769-1821; Tarbell, Ida M. (Ida Minerva), 1857-1944, ed. Publication date 1897

Napoleon's Proclamation to the French People on His Second Abdication, June 22, 1815 "Frenchmen: In commencing war for the national independence, I relied on the union of all efforts, of all wills, and the concurrence of all national authorities. ... Speeches and Correspondence of Napoleon Bonaparte. Edited by Ida M. Tarbell. (Boston: Joseph ...

Napoleon's Addresses. "The flash of Napoleon Bonaparte's sword so blinded men in his lifetime, and indeed, long after, that they were unable to distinguish a second weapon in his hand. The clearer vision which time and study bring have shown that he used words almost as effectively as the sword, and that throughout his career the address ably ...

Napoleon Bonaparte Writings (1796-1817) The excerpts below come from a compilation of Napoleon Bonaparte's writings compiled by R.M. Johnston (in The Corsican: A Diary of Napoleon's Life in His Own Words, 1910). April 22, 1796 (to the army.) Soldiers! In fifteen days you have won six victories, captured twenty-one flags, fifty-five guns ...

The speech was made on 21 March 1815 by Napoleon Bonaparte when reviewing his troops the day after his return to Paris during the Hundred Days. SOLDIERS, behold the officers of battalion who have accompanied me in my misfortune: they are all my friends; they are dear to my heart. Every time I saw them, they represented to me the several ...

On 19 Brumaire An VIII (10th November 1799), Bonaparte made a proclamation to the French people. This translation of his speech featured in the Annual Register for the year 1799, published in London in 1801. Proclamation of General Buonaparte. Nov. 10, eleven oclock at night. On my return to Paris, I found a division reigning amongst all the ...

The following texts form a series of letters, speeches, and official proclamations of Napoleon Bonaparte during his campaign in Egypt at the turn of the 19th century. Bonaparte, with the title of commander-in chief, joined together both the French army and navy in 1798 to carry out this complex conquest. His intention was to seize Egypt, which was part of the Ottoman Empire, in order to create ...

Napoleon's Addresses: The Egyptian Campaign. "Soldiers: You are one of the wings of the Army of England. You have made war in the mountains, plains, and cities. It remains to make it on the ocean. The Roman legions, whom you have often imitated, but never yet equaled, combated Carthage, by turns, n the seas and on the plains of Zama.

Learn about the short address by Napoleon after his defeat in Russia, where he bid farewell to his personal loyal and elite guard, the Old Guard. Find out the background, the transcript and the significance of this speech that marked the end of his military career.

Indeed, in 1789, 20-year-old Napoleon was in something of an identity crisis, looking to reconcile his ambitions of literary fame with his education as a soldier, his devotion to French revolutionary ideals with his Corsican nationalism. The early Revolution was undoubtedly a time of personal development for the young artillery lieutenant, the ...

Napoleon Bonaparte (1769-1821), also known as Napoleon I, was a French military leader and emperor who conquered much of Europe in the early 19th century. After seizing political power in France ...

Napoleon's Addresses: The Austerlitz Campaign 1805. Compiled By Tom Holmberg. Proclamation to the Troops on the Commencement of the War of the Third Coalition: September, 1805. "Soldiers: The war of the third coalition is commenced. The Austrian army has passed the Inn, violated treaties, attacked and driven our ally from his capital.

Napoleon, French Napoléon Bonaparte orig. Italian Napoleone Buonaparte, (born Aug. 15, 1769, Ajaccio, Corsica—died May 5, 1821, St. Helena Island), French general and emperor (1804-15).. Born to parents of Italian ancestry, he was educated in France and became an army officer in 1785. He fought in the French Revolutionary Wars and was promoted to brigadier general in 1793.

Napoleon's Addresses: 1812 Russian Campaign. Compiled By Tom Holmberg. Address to the Troops at the Beginning of the Russian Campaign, May 1812. "Soldiers: The second war of Poland has commenced. The first war terminated at Friedland and Tilsit. At Tilsit, Russia swore eternal alliance with France, and war with England.