Opinion and Informational Text Sets: Reading and Writing from One Text Set (+ a Freebie)

This past year I have been wrapping up a project that has been quite the labor of love: Monthly Text Sets. The monthly text sets solve a list of problems I consistently ran into when teaching 4th Grade ELA. But first, what are the monthly text sets? The monthly text sets are a set of nonfiction passages based around one topic. Students use the passages/articles to write in response to reading. The text set includes an opinion or informational writing prompt and reading comprehension questions. This means that you can use ONE set of texts to teach both reading and writing.

What does each monthly text set include?

- 2 – 3 Nonfiction Passages based around one topic

- Comprehension Questions aligned to standards

- Writing Prompt for Opinion or Informational Text-based writing in response to reading

- Graphic Organizer for Students

- Teacher Model Graphic Organizer

- Teacher Model Essay

- Differentiated for Grades 3-5

Reading Comprehension

Each text set includes 2 – 3 passages/articles (texts). They are nonfiction topics and the texts are differentiated for grades 3-5. The 4th and 5th grade articles sometimes remain the same, but the questions are different for each grade level. The questions follow the type of questions students might see on a state test such as the Florida State Assessment, and are aligned to the Common Core State Standards. Even if your state doesn’t exactly follow common core standards and they have their own, the questions are based on skills as well such as main idea, text structure, cause and effect, etc.

You can see examples of the question types below. Each grade level is included. I kept it this way so that even if you teach another grade level, you can differentiate for your students if needed. Don’t forget to grab this free shark text set before you go! Click here or on any of the images.

3rd Grade Reading Comprehension

4th Grade Reading Comprehension

5th Grade Reading Comprehension

You will also get a link that gives you access to the Standards Alignment Google Sheet. This way you can keep track of which standards each text set is covering. If you wanted to cover a specific skill, you have an easy way to track and access which standards are covered in which text set.

The writing portion includes a prompt in which students will write using both texts to respond. The prompt for this text set is an informational writing prompt:

Write an essay in which you explain the importance of sharks in the ocean ecosystem.

If you are familiar with my writing units, then you know that boxes and bullets are the standard around here. I have a lot of thoughts about that, but the gist is that they are so simple and provide a consistent structure for your students. Each text set includes a boxes and bullets graphic organizer for students and a teacher example to model or guide your students. Depending on where you are in your writing instruction, you can also have students do this in their notebook.

Writing paper is also included for a final published piece. Depending on how long you have and/or if you are in test-prep mode, you may choose to have students write a rough draft on notebook paper or in their writing notebook and then write a final copy on the publishing paper. Then, display in your classroom or hallway for the world to see all of your students’ amazing writing!

The plan and example essay includes 2-3 body paragraphs. So your students will be writing 4 – 5 paragraph essays. Depending on which you prefer to have your students write, you’ll just add/remove a body paragraph.

- Paragraph 1: Introduction

- Paragraph 2: Body Paragraph 1

- Paragraph 3: Body Paragraph 2

- Paragraph 4: Conclusion

There is also an editable teacher plan and essay available as a PowerPoint and Google doc so that you can edit and adapt the essay to your needs.

You might also use a Google Doc/PowerPoint to write the essay with your students and use the example as a guide.

What are the topics for each month?

One of my favorite parts about these text sets is that they have a monthly theme. HOWEVER, most topics can be used at any point in the year. Some topics are month-specific such as “Martin Luther King, Jr. Day” in January and “The Benefits of Bees” in April (it mentions Earth Day), but you can definitely fit these into to your current curriculum. And I have to tell you that even though all 12 months have been released, we’re still creating these each month.

- January: MLK Day (Opinion Writing Prompt) → Read the blog post here.

- February: Equality in Education: Mary McLeod Bethune and Thurgood Marshall (Informational Writing Prompt)

- March: Ants: Perk or Pest? (Opinion Writing Prompt)

- April: The Benefits of Bees (Informational Writing Prompt)

- May: Save the Sea Turtles (Informational Writing Prompt)

- June: Shark Shenanigans (Informational Writing Prompt) Grab this one for FREE here or at the end of this post.

- July: Hurricanes (Informational Writing Prompt)

- August: Video Games: Helpful or Harmful? (Opinion Writing Prompt)

- September: Homework: Helpful or Harmful? (Opinion Writing Prompt)

- October: Bats: Benefit or Bother? (Opinion Writing Prompt)

- November: Paid to Play: Should College Athletes be Paid? (Opinion Writing Prompt)

- December: Polar Bear Problems (Informational Writing Prompt)

WHY use monthly text sets?

Let’s talk about WHY you might want to use text sets in your classroom. While teaching 4th grade in a self-contained classroom, I consistently felt like we were giving our students too many texts to grapple with. At any point in time, we juggled some (and sometimes ALL ) of the following texts:

- Read Aloud (chapter book)

- Read Aloud (picture book)

- Writing Mentor Text (picture book)

- Reading Text Sets (passages as part of a center or independent practice)

- Guided Reading Text (small groups)

- Shared Reading Text (textbook used in whole groups or small groups)

(This is JUST for Reading)

- Writing Text Sets for test prep or writing in response to reading (In 4th and 5th Grade, this was ALLLLL the time.)

- Science Textbook

- Social Studies Text

When you list it out like that, it’s a LOT of texts. And they all serve a purpose. And they’re all important. But we continuously ran into problems.

❌We couldn’t fit them all in. (Shocking, right?)

❌We felt behind or overwhelmed because we were trying to do too much and unable to get in #allthethings.

❌Science and social studies were not getting the time they deserved. And honestly, I don’t think the future of our world can afford to not make science and social studies a priority.

The bottom line is we were trying to use TOO. MANY. TEXTS. One big issue that I began to see is that we treated the texts that we were using for writing as if we didn’t have to actually read them. As if we didn’t have to read them closely, dissect, analyze, and synthesize to produce a clear and concise essay with a controlling idea, supporting details, voice, etc. And, of course, in a way that did not copy the text. You and I both know that’s a lot to ask of a 4th grader (or 3rd grader or 5th grader or quite frankly – an adult.)

There had to be a better way. So I decided to ELIMINATE or INTEGRATE.

✅Eliminate the texts that we didn’t need to use, that didn’t support other content area standards or that didn’t offer high-engaging content or just weren’t the best quality of texts in the first place. If my students weren’t interested in it and it didn’t align to other content area standards – I needed to find better texts.

✅ Integrate Science and Social Studies into our ELA curriculum.

How do the monthly text sets fit into this?

Each monthly text set can be used for both Reading and Writing. The topic of each text set is either high-engaging or supports Social Studies/Science standards. It may not directly align with science or social studies standards, but topics support those areas. For example, many of the animal topics discuss life cycles and roles in the ecosystem.

HOW do I teach writing using the text sets?

If you’re looking for more support in teaching writing, then you may be interested in the complete writing units . Both the informational and opinion writing unit include daily lesson plans, PowerPoints that help you navigate writing workshop.

Are you ready to try the monthly text sets?

If you’re ready to give the monthly text sets a try in your classroom, you can grab the Sharks Text Set freebie by clicking on the button below.

Just click here or on the image below to snag them.

Trending Post : 12 Powerful Discussion Strategies to Engage Students

How to Use Text Sets to Build Background Knowledge

Searching for engaging ways to build students’ background knowledge? Perhaps you need an activity to help students prepare to read a complex text, to write an essay, or to engage intelligently in a class discussion. Maybe you just want them to know a little bit about a topic before attending a presentation or lecture. Text sets might just be your new best friend. Here’s why.

What are text sets?

A text set is simply a collection of resources about a given topic. They typically include a range of media types. To make them engaging, students should have a variety of options to choose from. You may consider including…

- excerpts from books

- infographics

- political cartoons

- picture books

Teachers can compile text sets for topics students will be exploring. It may save time to collaborate with others who teach the same course. Plus, more perspectives can add depth to the text set.

How do text sets help students?

Text sets benefit students in ALL content areas. Students develop a wider understanding of a topic when they read many texts about it. And, research shows that background knowledge aids reading comprehension, critical thinking, and retention of information learned . In short, prior knowledge is a game changer!

Reading: When students are preparing to read a complex piece, text sets can help to build their background knowledge on vocabulary, historical context, allusions, and more. Imagine students are preparing to read Romeo and Juliet. Dipping their toes in an article about mythology, information about social issues, and the poem Pyramus and Thisbe can provide them with background knowledge to recognize the allusions (like to Cupid, Echo, and Aurora), understand the relational tensions, and make connections with earlier texts on a similar theme.

Writing: If you want students to write something, text sets help build them develop a more knowledgable voice. For instance, consider an editorial. Students will need to know about the role of the president and the issues surrounding compulsory voting in Australia (among other perspectives) before crafting their response. Text sets can be the springboard for credible research that will give them the confidence they need to write with an authoritative voice.

Discussions: Then, there’s always speaking and listening. Often, students don’t participate in class discussions because they haven’t had time to formulate their opinions in a safe space. Text sets can help. By providing the essential question and sub-questions students will discuss, they can think through their ideas as they explore the texts. Text sets, coupled with turn and talk and informal, small group discussions, can be energizing and informative. In short, they can give students the confidence they need to speak up in a whole-class setting.

What does it look like?

Truly, text sets can be as basic or as simple as you’d like. Format them in a bulleted list, a choice board, or a virtual classroom graphic. I like to make text sets visually appealing for the added engagement benefit.

See an example below. Click here to make a copy for your Drive.

How do I create a text set?

When creating a text set, try to include texts that represent different angles of the topic. Texts sets can have one anchor text supported by a variety of sub-texts, or they could build in complexity. If you want an interest-based approach in which students choose which texts they’d like to explore, text sets can be more informally organized.

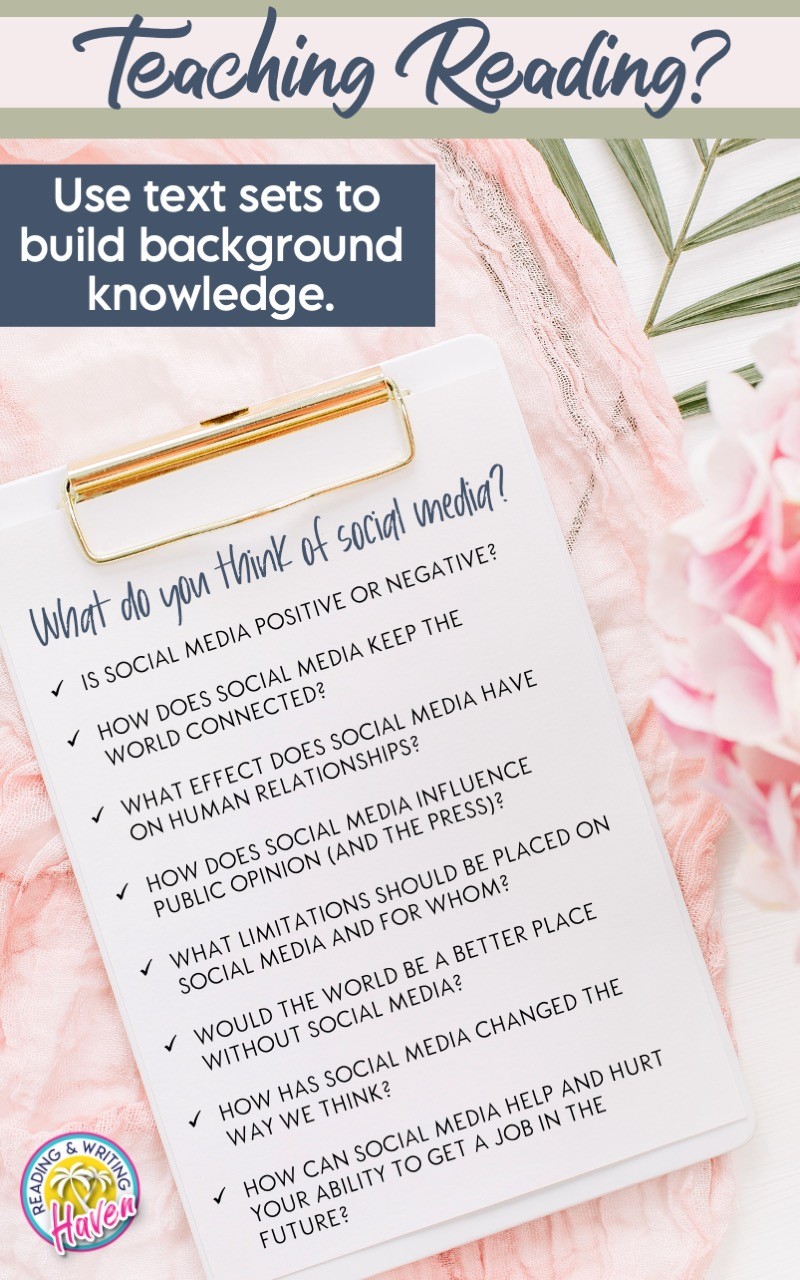

Begin by identifying the essential question you want students to explore or answer. For example, when I collaborated with another instructional coach in my district to create the above text set for social media, we debated what question would be the best for creating an open, interesting class discussion. After considering many options, we kept it simple and went with What do you think about social media?

This general, high-interest question allowed us to build in a variety of sub-questions students could research and discuss to prepare for a larger, summative speaking and listening discussion. Some of the sub-questions we created include:

- Is social media positive or negative?

- How does social media keep the world connected?

- What effect does social media have on human relationships?

- How does social media influence public opinion (and the press)?

- What limitations should be placed on social media and for whom?

- Would the world be a better place without social media?

- How has social media changed the way we think?

- How can social media help and hurt your ability to get a job in the future?

High-interest text sets provide multiple perspectives , sub-topics , and genre types to engage students. If you can build in options that cover a variety of text complexities , it will help to engage readers at many readiness levels.

Where do I find the texts?

Finding quality texts can be time consuming. So, it’s always helpful if you can work with others. To save you time, here are some of my starting points:

- Scholastic magazines (subscription needed)

- Library of Congress

- New York Times Text to Text

- Artwork by topic

- Political Cartoons

Should I include students?

Should you include students in the text set creation process? Absolutely! As with anything else, students love having agency in their learning. Use text sets to provide avenues for choice and voice. After students have experienced a text set you have created, invite them into the process! Tell them you need their help. It’s a great hook for promoting student-driven extension research. And, they can focus on filtering for credible sources.

How do I assign them?

If your students are used to working productively in a self-paced environment, text sets probably won’t present many issues! One of the keys to assigning text sets is making sure students know what the classroom environment should look, sound, and feel like as they work. Do you want students to take notes? record new vocabulary? work collaboratively? And, those norms are up to you…the teacher! So, define how you want students to work, talk about those expectations with your classes, and then practice until they get it.

As middle and high school teachers, one of the hardest parts about teaching is when students have huge gaps in background knowledge. No doubt, background knowledge prepares students to read complex texts, write with authority, and speak confidently. Even though they take a bit of time to compile, text sets allow for differentiation and small group teaching opportunities. Work them into learning stations, center activities, and more.

If you need a strategy to support students where they are, provide high-interest choices, and teach flexibly, text sets may be just the thing you need.

RELATED ARTICLES:

- Reading Strategies for Secondary

- Re-Reading with Color: A Comprehension Strategy

Get the latest in your inbox!

Writing based on Texts

Developing support.

Note the phrase “working thesis.” As you start developing support for your thesis, you may find that the support yields information that the thesis does not plan for. So you may need to edit your thesis or else decide not to pursue that line of support. You review and finalize your thesis once you fully develop your support.

The following video, while focused on writing a single paragraph, offers solid information to explain the concept of support and how support relates to a main idea.

Here’s one process to follow in order to develop support for your working thesis:

- Analyze your working thesis to see what type of insights and information you’ve promised your reader in the angle.

- Create working topic sentences to address the promise in the thesis’ angle. Extract ideas one by one from the thesis’ angle, and write a topic sentence for each idea, with its own topic and angle. Remember that topic sentences offer general ideas that your support will then specify.

- Fill in with examples and details under each topic sentence, to fully explain each topic sentence’s angle. Start with the topic sentence about which you have the most to say, even though you may not end up placing that topic sentence first in the finished essay. Just start in the place that’s easiest for you, to get started writing.

- Understand that writing is an iterative process. As you start to develop your support, you may decide to circle back to your thesis and topic sentences as well as move forward with developing details, examples, and insights. For example, while developing support, you may decide that you need to add another topic sentence that did not occur to you initially.

Working Thesis: Because images in advertising art reflect their social context, you can infer what’s important to the general public at different eras through analyzing ads.

If you’re using this as your working thesis, you’ll need to determine how many and which eras you want to include. You know that you can’t write about all eras, because you’re only writing a 3-5 page essay. And you know that you want to write about advertising in the U.S. as opposed to other cultures, because as a U.S. resident, that’s the one you know the most about. You decide that you want to focus on latter 20th century ads, and decide to write about particular decades instead of eras as a way of narrowing your scope, which will enable you to delve more deeply into the support. You end up choosing the 1960s, 70s, 80s, and 90s. You develop a topic sentence for each decade:

- Ads in the 1960s tended to use bright colors and highlight conventional values; their glossy look essentially glossed over the social upheaval and changing value systems that were considered “anti-establishment” at the time.

- Ads in the 1970s tended to use a more subdued palette and less conventional images, as fuller infusion and popularization of skepticism and counter-culture, as well as emerging new technologies, were highlighted.

- Ads in the 1980s were bright, eye-popping, highly stylized productions, in sync with the swing back to big business and power of certain groups.

- Ads in the 1990s remained colorful, but started to push previously accepted limits of “appropriateness” with newly provocative images, as well as focus more fully on celebrities. Both of these developments may have occurred because of the safer economic and social climate of the time, which provided a stable base for experimentation.

After developing these working topic sentences, you have an additional insight—that ads during these four decades started to define two contentious strains in contemporary society. You decide to circle back to revise your working thesis, and then add another topic sentence to deal with this insight as a way of putting your thoughts into broader context toward the end of the essay. You also realize that you focused on color palette, style, and content of ads, so you revise your working thesis to specify it further. You end up with the following working thesis.

Revised Working Thesis: Images in advertising art reflect their social context. From analyzing the color palette, style, and content of ads in the 1960s through the 1990s, you can both infer what was important to society during those decades as well as see how those decades laid the groundwork for the more divisive rifts between tradition and experimentation in contemporary society.

As you can see from this example, it can be helpful to lay out the conceptual structure—the structure of ideas—of an essay, before you flesh out that structure with support. However, if this process does not resonate with you, there are other methods of approach.

Here’s another process to follow to develop support for your working thesis:

- Just start writing based on your working thesis to see what topic sentences and supporting examples evolve.

- Or you may want to use lists or mind maps to develop topic sentences and supporting details.

- Once you have developed a substantial amount of information, categorize it and name the categories. Any method is o.k. You’ll eventually end up with a thesis, topic sentences and paragraphs of support, in order to have an essay whose ideas a reader can follow.

- enough support (if there are categories with very little information)

- slanted support (categories overloaded with information)

- inappropriate support (categories that are too general), or

- support only marginally related to your thesis (category names that don’t quite relate to the angle in the thesis)

Here’s the start of a mind map to develop support for the working thesis that advertising art reflects its social context.

mind mapping software courtesy of bubbl.us

From the start of this mind map, you can see a few things. One is that categories are starting to emerge. The writer has identified two decades, so it makes sense to categorize by decade. Another is that the writer was able to think of some detailed examples, but may need to add more general examples that show how ads reflect their cultural contexts (e.g., the writer needs more than just “risque” for the 1990s). You can also see that a mind map is a good way to differentiate levels of detail.

As you do more writing, you’ll create and refine your own process for developing support. Just make sure that you’re developing support for topic sentences that relate to your overall thesis.

Types of Support

There are many types of support that specify ideas in topic sentences. You’ll use some or all types of support, depending on the purpose of your essay. Commonly-used types of support consist of the following:

- Personal Observations

The type of support you include in an essay will depend on your writing purpose and audience. For example, if you’re attempting to analyze an issue in order to persuade your audience to take a particular position on that issue, you might rely on facts, statistics, and concrete examples, rather than personal opinions, to provide logical evidence. If you’re writing an essay to offer a personal reaction to something you observed, you might rely on observations, examples, and details. If you are writing a research essay which synthesizes information from many texts, you’ll include more summaries, paraphrases, and quotations from sources, along with reasons and facts. If you’re writing any of these essays for an audience that is not familiar with your topic, you’ll include more concrete details and examples to make sure they understand your points. Realize that all types of support are usable in all types of essays, and that it’s typical to blend many or all of these types of support when supporting a topic sentence. Also understand that although it’s useful to recognize different types of support, writers don’t necessarily think in terms of “I need a fact here” or “I need an observation there.” Writers just write. Conscious consideration of different types of support occurs as you continue to work with and review your support, in terms of your thesis, topic sentences, purpose, and audience.

The two videos that follow explain different types of support.

Two key, inter-related skills in developing support are 1) the ability to distinguish between more general and more specific information, as units of support usually move from general –> specific, and 2) the ability to figure out a logical sequence of information.

Practice these skills by ranking the sentences below from most general (topic sentence) to most specific, a ranking which should also move logically from more basic to more specialized information.

- One 12-gram serving of Crisco contains 3g of saturated fat, 0g of trans fat, 6g of polyunsaturated fat, and 2.5g of monounsaturated fat.

- There are different types of unsaturated fats: monounsaturated, polyunsaturated, and omega-3 fatty acids.

- According to its label, Crisco contains a higher percentage of unsaturated than saturated fat.

- Mono and polyunsaturated fats can lower your risk of Type II diabetes.

- Unsaturated fats provide a number of benefits to the body.

- All three types of unsaturated fats can help lower your risk of heart disease.

- One 12-gram serving of Crisco contains 3g of saturated fat, 0g of trans fat, 6g of polyunsaturated fat, and 2.5g of monounsaturated fat.

Units of Support

When you’re developing support, think in terms of “units of support” as opposed to paragraphs. A unit of support develops the ideas in topic sentence, and that unit of support may include more than one paragraph.

As you develop units of support, keep in mind that those units usually move from more general (the unit’s topic sentence) to more specific (details and examples that explain and support the angle in the topic sentence) and optionally back to more general (re-statement of the topic sentence, as a lead-in to the next topic sentence and unit of support, if it makes sense within the flow of the essay). Also remember to paragraph when needed within each unit of support.

Paragraphing within the Draft/Units of Support

Like sentence length, paragraph length varies. There is no single ideal length for “the perfect paragraph.” Know, though, that if you have lengthy units of support and don’t paragraph within them, your readers might wonder if the paragraph is ever going to end, and they might lose interest.

The most important thing to keep in mind is that the amount of space needed to develop one idea will likely be different than the amount of space needed to develop another. In general, start a new paragraph when:

- You’re ready to begin developing a new idea.

- You want to emphasize a point by setting it apart.

- You’re getting ready to continue discussing the same idea but in a different way (e.g., shifting from comparison to contrast).

- You notice that your current paragraph is getting too long (more than three-fourths of a page or so), and you think your writers will need a visual break.

On the other hand, you don’t want your essay to include too many short paragraphs in a series. In general, combine paragraphs when:

- You notice that some of your paragraphs appear to be short and choppy.

- You have multiple paragraphs on the same topic.

- You have undeveloped material that needs to be united under a clear topic.

Enough Support

How much support is “enough?” That’s a question that only you as a writer can answer. Know that the number of paragraphs in an essay as well as the number of topic sentences and units of support depend on what’s needed to fully support the angle in the thesis sentence. There’s really no way to know that until you start writing.

However, one good method to gauge “enough” is to put yourself into a reader’s role. Draft your essay, set the draft aside, and then re-read the draft. Ask if a reader can easily relate your concepts to real life, based on the support you have provided. If you’re analyzing an issue, ask if you’ve provided different viewpoints and shown how yours is the most valid, through your evidence and explanations. You may circle back to develop fuller support, or to hone your existing support, once you write and then consider your essay draft. So, just start developing your support using a process that makes sense to you, and see how your draft develops. There will be plenty of time to add, delete, and re-organize paragraphs and units of support in the revision process.

- Developing Support/Drafting the essay, includes material adapted from College Writing and The Word on College Reading and Writing; attributions below. Authored by : Susan Oaks. Project : Introduction to College Reading & Writing. License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- College writing, pages on Types of Support, Working with Support. Authored by : Susan Oaks. Located at : https://courses.lumenlearning.com/suny-esc-wm-englishcomposition1/ . License : CC BY-NC-SA: Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike

- The Paragraph Body: Supporting Your Ideas. Authored by : Carol Burnell, Jaime Wood, Monique Babin, Susan Pesznecker, and Nicole Rosevear. Provided by : OpenOregon. Located at : https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/wrd/chapter/the-paragraph-body-supporting-your-ideas/ . License : CC BY-NC: Attribution-NonCommercial

- image of woman typing at computer. Authored by : StockSnap. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/girl-woman-working-office-business-2618562/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- image of a person's hands typing on a laptop. Authored by : Pexels. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/business-computer-connection-2178566/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- image of man typing on computer. Authored by : Gerd Altmann. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/entrepreneur-start-start-up-career-696976/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

- video Supporting Sentences. Authored by : Jonathan Newsome. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nWKMLadQbrc . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- video Essay Writing - Body Paragraphs - Supporting Details. Provided by : GoReadWriteNow. Located at : https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Y0hM5Ck4T0&feature=youtu.be&t=148 . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- video Essay Writing - Body Paragraphs - Insightful Analysis. Provided by : GoReadWriteNow. Located at : https://youtu.be/_Mr6n9ZgQMI?t=177 . License : Other . License Terms : YouTube video

- image of hand coming out of laptop screen, holding a question mark. Authored by : Gerd Altmann. Provided by : Pixabay. Located at : https://pixabay.com/photos/question-mark-laptop-hand-keep-3717894/ . License : CC0: No Rights Reserved

Privacy Policy

How Arguments Work - A Guide to Writing and Analyzing Texts in College

(3 reviews)

Anna Mills, Academic Senate of the California Community Colleges OER Initiative

Copyright Year: 2021

Publisher: LibreTexts

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Carl Smeller, Associate Professor, Texas Wesleyan University on 7/31/23

The text covers all the important concepts relevant to argumentation. In fact, it goes more in--depth than any one instructor might want. The advantage of the text is that each chapter is subdivided so that an instructor can assign just the... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

The text covers all the important concepts relevant to argumentation. In fact, it goes more in--depth than any one instructor might want. The advantage of the text is that each chapter is subdivided so that an instructor can assign just the sections that s/he thinks are most relevant or useful to the assignments in a given course.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

I didn't notice any glaring inaccuracies in the book's content.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

I like that most of the examples offered in the text concern issues that are of current concern. Unlike another text I reviewed, which contained several references to the 2008 Presidential election (when this year's freshmen were three years old), How Arguments Work has links to articles about immigration, Covid, transgender experience--issues that are still front of mind.

Clarity rating: 5

One of the most helpful facets of the text is the way it demonstrates the process of analyzing arguments. The author recommends that students take notes on arguments as they read; then the text provides examples of just this kind of note taking. If a concept might be unclear for a reader, an object lesson in how it works in practice is a great aid for clarity.

Consistency rating: 5

The book seems consistent in its terminology and in its address to the reader.

Modularity rating: 5

I think this text is more modular than most. Each chapter is divided into subsections, so students unaccustomed to long reading assignments are not likely to become overwhelmed. Another nice feature is the availability of an audio version of each page, which would be especially helpful for second-language students or those with dyslexia.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

Each chapter starts with a concise statement of learning outcomes, then an outline of the chapter that aligns with those outcomes. The organization of the book as a whole is logically scaffolded from understanding and responding to others' arguments to formulating, researching, and writing one's own. Pretty standard stuff for a comp textbook, so this one is following long-established convention.

Interface rating: 5

The interface is very convenient in that it offers multiple ways to move through the text. A reader can easily access the overall table of contents, the outline of each chapter, and the next and previous subsections of each chapter. Everything displays as it should, as least when presented on a full-sized screen (not sure what happens on a phone).

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

Editing seems sound.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

Although the book does allude to contentious socio-political issues, it does not do so in ways that are biased or culturally insensitive. Illustrations in the text portray people from a variety of backgrounds and ages.

One of things I like most about this book is how scrupulous it is with attribution and citation within the text, especially for photographs. It gives student readers a fantastic model of the attributive moves they will have to make within their own writing. And since most of these attributions are hyperlinked, they show students writing in a multi-modal classroom how to give credit where it is due in our contemporary world. I also like the large number of linked examples of argument in the real world, which this text seems to provide in greater abundance than other OER comp texts that I have reviewed.

Reviewed by Liz Onufer, English Instructor, College of Eastern Idaho on 5/4/22

The textbook covers a great breadth of content with the appropriate depth for 100-level writing courses. The chapters provide an introductory understanding of a wide range of composition content including argument, academic research, the writing... read more

The textbook covers a great breadth of content with the appropriate depth for 100-level writing courses. The chapters provide an introductory understanding of a wide range of composition content including argument, academic research, the writing process, and writing conventions.

The content is accurate, unbiased, and error-free.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 3

The textbook provides a variety of examples of claims on relevant topics today. Some of the sample arguments and articles, though, may be too timely for the textbook to stand up well in the long term, such as the Coronavirus article. Updating this will not be easy as the articles and student response examples are threaded throughout the text in multiple chapters. The border argument is another example that would be difficult to update as it is referenced throughout the text and would require substantial revisions throughout the textbook if revised.

The brief introductions to evidence and logical fallacies are the right fit for 100-level composition students who are new to the rhetorical terminology. The definitions and examples are explained in simple terms. The overview of the research process, source evaluation, and MLA format is also simple and straightforward.

The textbook’s framework for template phrases is used consistently. Each chapter ends with a reference sheet of phrases. The argument examples are also referenced consistently throughout, with chapters referencing the example text from the chapter before. This is great for consistency but can negatively impact longevity and modularity.

Modularity rating: 3

The textbook is organized in smaller reading sections. Chapters, though, are primarily set up for sequential reading as references are made to the examples and concepts covered in the previous chapter. Not only does this impact reading sequence, it also impacts being able to pull chapters/sections for reading independent of the textbook. Some chapter sections reference example texts or concepts from the previous chapter and would not make sense as an independent lesson. The common phrases at the end of each chapter are an excellent standalone resources for pulling out or quick reference. If the entire textbook is not used, these sections at the end of chapters would still be useful for teaching students how to read, analyze, and incorporate common phrases in academic argument.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

The textbook is organized with clear scaffolding and building of concepts. I do find it unusual that the pathos and ethos chapters are placed after evaluating an argument rather than with the logos chapter.

Interface rating: 4

The online version of the text is easy to read and navigate. When downloading and accessing as a PDF, the navigable table of contents and index hyperlink to the online text rather than within the PDF. This is problematic for students accessing the text offline and wishing to navigate with the TOC or index. Also, in the PDF version, sections 5.8 and 6.7 are blank.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

The text offers a diverse representation of students in images. One article and argument that is referenced multiple times is focused on border crossings and immigration. Because of the frequency of use of this argument, this may appear to single out immigrants.

The textbook has many assets for the 100-level composition course, specifically those focused on argument evaluation and development. The language is approachable, the breadth is comprehensive, and the depth is appropriate. The Teacher's Guide at the end offers excellent resources, including quizzes, assignments, course maps, and lesson plans.

In the model of They Say/ I Say: The Moves that Matter in Academic Writing by Gerald Graff and Cathy Birkenstein, the textbook leans heavily on teaching students how to read, analyze, and use the common phrases of academic writing. Having taught with They Say/I Say, this textbook develops many more concepts than Graff and Birkenstein, making it possible to use as the single text in the composition class. If one does not agree with the pedagogy of teaching template phrases, this textbook would not be a good fit.

The articles and arguments threaded throughout the text as recurring examples do pose a few problems for longevity, modularity, and cultural relevance. Another concern with these texts are that they are from popular sources (The New York Times and The Atlantic) rather than academic sources. The section that addresses academic sources refers to types of sources at tiers 1 – 4 rather than academic/scholarly sources and popular sources. While the explanation of the types of sources is accurate, the terminology of tiers is not common academic language.

Reviewed by Tim Marmack, Assistant Professor of English, University of Hawai’i Maui College on 12/12/21

The text covers all areas and ideas of the subject appropriately and provides an effective index and/or glossary. read more

The text covers all areas and ideas of the subject appropriately and provides an effective index and/or glossary.

Content is accurate, error-free and unbiased.

Content is up-to-date, but not in a way that will quickly make the text obsolete within a short period of time. The text is written and/or arranged in such a way that necessary updates will be relatively easy and straightforward to implement.

The text is written in lucid, accessible prose, and provides adequate context for any jargon/technical terminology used.

The text is internally consistent in terms of terminology and framework.

The text is easily and readily divisible into smaller reading sections that can be assigned at different points within the course (i.e., enormous blocks of text without subheadings should be avoided). The text should not be overly self-referential, and should be easily reorganized and realigned with various subunits of a course without presenting much disruption to the reader.

The topics in the text are presented in a logical, clear fashion.

The text is free of significant interface issues, including navigation problems, distortion of images/charts, and any other display features that may distract or confuse the reader.

The text contains no grammatical errors.

The text is not culturally insensitive or offensive in any way. It should make use of examples that are inclusive of a variety of races, ethnicities, and backgrounds.

In the past, I have used, for my argumentative and research writing courses, several different 400-600-page textbooks whose primary focus was on the argumentative writing process approach. In every single instance, I felt guilty by the middle of the semester - first, for knowing that there would be no way that, as a class, we could or would cover all content within a 16-week time frame; as well, I felt guilty because my students spent a considerable amount of money on the textbook, even for a used copy. And, while probably 75% of the information in any given text would overlap with information from another text, each text, in itself, contained information that was unique to that particular text.

However, I have found that the How Arguments Work text covers most everything under the sun - a clearing house of sorts, content-wise, in the area of written/approach to argumentation. Yes, chapters do exist such as (#1) “Why Study Argument,” (#4) “Assessing the Strength of an Argument (Logos),” and (#8) “How Arguments Appeal to Emotion,” - but chapters also exist on the research process, (#6) “The Research Process,” and (#7) “Forming a Research-Based Argument) - and on (#11) “The Writing Process,” (#12) “Essay Organization,” and (#13) “Correcting Grammar and Punctuation.”

As well, each chapter has a number of sub-sections (easily delineated both on the Contents page and throughout the text), e.g., 1:1, 1:2, etc.; timed audio versions of each sub-section, e.g., 2.3, 2.4, etc.; and practice exercises for each sub-section, e.g., 3.2., 3.3., etc.

For sure, this OER text is a blessing. I can pull information to use not only in my argumentative and research writing courses, but in both my composition and business writing courses!

Table of Contents

- 1: Introduction

- 2: Reading to Figure out the Argument

- 3: Writing a Summary of Another Writer’s Argument

- 4: Assessing the Strength of an Argument (Logos)

- 5: Responding to an Argument

- 6: The Research Process

- 7: Forming a Research-Based Argument

- 8: How Arguments Appeal to Emotion (Pathos)

- 9: How Arguments Establish Trust and Connection (Ethos)

- 10: Writing an Analysis of an Argument’s Strategies

- 11: The Writing Process

- 12: Essay Organization

- 13: Correcting Grammar and Punctuation

- 14: Style: Shaping Our Sentences

- 15: Teacher's Guide

Ancillary Material

About the book.

How Arguments Work takes students through the techniques they will need to respond to readings and make sophisticated arguments in any college class. This is a practical guide to argumentation with strategies and templates for the kinds of assignments students will commonly encounter. It covers rhetorical concepts in everyday language and explores how arguments can build trust and move readers.

About the Contributors

Anna Mills currently serves as the English Discipline Lead for the Academic Senate of the California Community Colleges OER Initiative. She has taught English at City College of San Francisco since 2005 and has specialized in teaching Argumentative Writing and Critical Thinking since 2008. She earned a master’s degree from Bennington College in Writing and Literature with a focus on nonfiction writing. Her collection of book reviews, “Anna Mills on Nature Writing,” can be found at onnaturewriting.blogspot.com. Her essays have appeared in The Writer's Chronicle, The Sun , Salmagundi , Cimarron Review , Isotope: A Journal of Literary Nature and Science Writing , North Dakota Quarterly , Under the Sun , Banyan Review , and various anthologies. She interned as a technical writer at Sun Microsystems and spent two years as a writer and web developer for the nonprofit CompuMentor, where she published a collection of articles for the portal TechSoup.org.

Contribute to this Page

Developing Evidence-Based Arguments from Texts

About this Strategy Guide

This guide provides teachers with strategies for helping students understand the differences between persuasive writing and evidence-based argumentation. Students become familiar with the basic components of an argument and then develop their understanding by analyzing evidence-based arguments about texts. Students then generate evidence-based arguments of texts using a variety of resources. Links to related resources and additional classroom strategies are also provided.

Research Basis

Strategy in practice, related resources.

Hillocks (2010) contends that argument is “at the heart of critical thinking and academic discourse, the kind of writing students need to know for success in college” (p. 25). He points out that “many teachers begin to teach some version of argument with the writing of a thesis statement, [but] in reality, good argument begins with looking at the data that are likely to become the evidence in an argument and that give rise to a thesis statement or major claim” (p. 26). Students need an understanding of the components of argument and the process through which careful examination of textual evidence becomes the beginnings of a claim about text.

- Begin by helping students understand the differences between persuasive writing and evidence-based argumentation: persuasion and argument share the goal of asserting a claim and trying to convince a reader or audience of its validity, but persuasion relies on a broader range of possible support. While argumentation tends to focus on logic supported by verifiable examples and facts, persuasion can use unverifiable personal anecdotes and a more apparent emotional appeal to make its case. Additionally, in persuasion, the claim usually comes first; then the persuader builds a case to convince a particular audience to think or feel the same way. Evidence-based argument builds the case for its claim out of available evidence. Solid understanding of the material at hand, therefore, is necessary in order to argue effectively. This printable resource provides further examples of the differences between persuasive and argumentative writing.

- One way to help students see this distinction is to offer a topic and two stances on it: one persuasive and one argumentative. Trying to convince your friend to see a particular movie with you is likely persuasion. Sure, you may use some evidence from the movie to back up your claim, but you may also threaten to get upset with him or her if he or she refuses—or you may offer to buy the popcorn if he or she agrees to go. Making the argument for why a movie is better (or worse) than the book it’s based on would be more argumentative, relying on analysis of examples from both works to build a case. Consider using resources from the ReadWriteThink lesson plan Argument, Persuasion, or Propaganda: Analyzing World War II Posters

- The claim (that typically answers the question: “What do I think?”)

- The reasons (that typically answer the question: “Why do I think this?”)

- The evidence (that typically answers the question: “How do I know this is the case?”).

- Deepen students’ understanding of the components of argument by analyzing evidence-based arguments about texts. Project, for example, this essay on Gertrude in Hamlet and ask students to identify the claim, reasons, and evidence. Ask students to clarify what makes this kind of text an argument as opposed to persuasion. What might a persuasive take on the character of Gertrude sound like? (You may also wish to point out the absence of a counterargument in this example. Challenge students to offer one.)

- Point out that even though the claim comes first in the sample essay, the writer of the essay likely did not start there. Rather, he or she arrived at the claim as a result of careful reading of and thinking about the text. Share with students that evidence-based writing about texts always begins with close reading. See Close Reading of Literary Texts strategy guide for additional information.

- Guide students through the process of generating an evidence-based argument of a text by using the Designing an Evidence-based Argument Handout. Decide on an area of focus (such as the development of a particular character) and using a short text, jot down details or phrases related to that focus in the first space on the chart. After reading and some time for discussion of the character, have students look at the evidence and notice any patterns. Record these in the second space. Work with the students to narrow the patterns to a manageable list and re-read the text, this time looking for more instances of the pattern that you may have missed before you were looking for it. Add these references to the list.

- Use the evidence and patterns to formulate a claim in the last box. Point out to students that most texts can support multiple (sometimes even competing) claims, so they are not looking for the “one right thing” to say about the text, but they should strive to say something that has plenty of evidence to support it, but is not immediately self-evident. Claims can also be more or less complex, such as an outright claim (The character is X trait) as opposed to a complex claim (Although the character is X trait, he is also Y trait). For examples of development of a claim (a thesis is a type of claim), see the Developing a Thesis Handout for additional guidance on this point.

- Modeling Academic Writing Through Scholarly Article Presentations

- And I Quote

- Have students use the Evidence-Based Argument Checklist to revise and strengthen their writing.

More Ideas to Try

- This Strategy Guide focuses on making claims about text, with a focus on literary interpretation. The basic tenets of the guide, however, can apply to argumentation in multiple disciplines—e.g., a response to a Document-Based Question in social science, a lab report in science.

- For every argumentative claim that students develop for a text, have them try writing a persuasive claim about the text to continue building an understanding of their difference.

- After students have drafted an evidence-based argument, ask them to choose an alternative claim or a counterclaim to be sure their original claim is argumentative.

- Have students use the Evidence-Based Argument checklist to offer feedback to one another.

- Lesson Plans

- Professional Library

- Student Interactives

- Strategy Guides

Students prepare an already published scholarly article for presentation, with an emphasis on identification of the author's thesis and argument structure.

While drafting a literary analysis essay (or another type of argument) of their own, students work in pairs to investigate advice for writing conclusions and to analyze conclusions of sample essays. They then draft two conclusions for their essay, select one, and reflect on what they have learned through the process.

The Essay Map is an interactive graphic organizer that enables students to organize and outline their ideas for an informational, definitional, or descriptive essay.

- Print this resource

Explore Resources by Grade

- Kindergarten K

Creating Text Sets for Your Classroom: A Guide to Getting Started

As teachers, our goal is to prepare our students for the world beyond our classroom doors.

Cognitive scientists have long recognized that to effectively solve real-world problems, we need to integrate multiple perspectives and types of reading tasks .

Their research underscores the importance of giving students opportunities to engage critically with information across multiple types of text—enter text sets.

- What is a Text Set?

A text set is a carefully curated collection of texts, usually centered around a common theme, topic, or concept. These texts can encompass a wide range of formats, including articles, essays, poems , short stories, videos, podcasts , infographics, and more.

The primary purpose of a text set is to provide readers with a multifaceted exploration of a concept, allowing them to gain a deeper and more comprehensive understanding.

Our blog will discuss the benefits of teaching with text sets, how to create text sets, and ideas for how to use text sets in your classroom.

Benefits of Teaching with Text Sets

Research has demonstrated that the use of text sets improves learning outcomes . Results show that students have more knowledge of the concepts in the texts, increased understanding of vocabulary, and better recall skills compared to students who read unrelated texts.

Text sets offer benefits for all students in all content areas. They increase the following:

- Background Knowledge

Strong background knowledge makes learning easier . It helps students to better comprehend what they’re reading, aids critical thinking, and improves their retention of what they’ve learned. When teaching vocabulary, background knowledge can help students understand and remember new words more effectively.

An effective text set builds students’ background knowledge about a specific topic or concept.

- Critical Thinking Skills

By comparing and contrasting texts within a set, students can develop their critical thinking skills. You can use text sets with current events to help students analyze different perspectives and create their own well-informed opinions.

Text sets can be designed to accommodate different learning styles and interests. Some students may prefer to read articles, while others may prefer visual content like infographics or videos. By incorporating a variety of formats, you can differentiate for your students’ learning needs and ensure that all students are engaged in learning.

- Language Skills

Not only do students develop content knowledge through the use of text sets, but they also build important language and literacy skills.

Text sets help students develop background and contextual knowledge as well as increase text-to-text connections—all of which strengthen their reading comprehension skills . As students increase their breadth of knowledge of a topic, they develop a more authoritative voice in their writing. As they become more knowledgeable, their confidence to participate in discussions can also grow.

How to Create Text Sets

Creating effective text sets for your classroom requires thorough planning, as well as a bit of research.

- Planning Your Text Set

Consider the following steps as you begin to create a text set.

- Start with your objective. Think about what your students need to know and use that to determine the common theme for your text set.

- Find an anchor text. It’s often helpful to select an “anchor text” to serve as the cornerstone for your text set. Anchor texts are grade-level, rich, and complex.

- Consider your students. While it’s great to have text sets that can be used from year to year, it’s also important to tailor some text sets to your students. Consider their interests—are there any specific topics that students are interested in this year? Think about their needs—do you have English learners or students who need accommodations? Make sure you include texts that will engage all of your students.

- Gather diverse texts. Effective text sets include a variety of sources that will support your learning objectives. Your texts must be authentic, credible, and accurate.

- Plan for interaction. Plan activities and discussion questions that will encourage students to interact meaningfully with the texts as well as their peers.

- Text Set Resources

Finding quality texts for your text set is important—and time-consuming.

Consider reaching out to your colleagues for ideas and resources as you build your text sets. Find teachers who teach the same grade or class and ask them for their favorite texts. Your school librarian is an excellent resource as well.

We’ve compiled a list of some of our top picks for building text sets below. As always, be sure to preview any resources before sharing them with students.

Books and Poems

American Library Association: ALSC

- Age level: Birth through age 14

- Why we love it: The Associations for Library Service to Children’s annual list of notable children’s books, digital media, and recordings includes books of information, poetry, and pictures to make searching for quality text a breeze.

The American Library Association: Teen Bookfinder

- Age level: Ages 12-18

- Why we love it: Find award-winning books for your teens in this database compiled by librarians and educators.

- Age level: Grades K–12

- Why we love it: This free platform contains stories and poems in audiobook format. Download any title as a PDF so that students can follow along with the text.

Academy of American Poets

- Age level: Grades 3–12

- Why we love it: Search over 10,000 poems by occasion, theme, form, or author on this extensive poetry site.

Articles and Magazines

Smithsonian Magazine

- Age level: Grades 6–12

- Why we love it: Find articles for nearly any topic, ranging from science to the arts to current events on the Smithsonian Magazine site.

- Why we love it: Create an account to search for text sets created by other teachers or build your own using Newsela’s text set feature.

Scholastic Magazines

- Age level: Grades PreK–12, subscription required

- Why we love it: Magazines feature a variety of topics from health and life skills to math with engaging images and educational articles.

Infographics

Kids Discover

- Why we love it: Find free downloadable infographics on a range of nonfiction topics—beautifully designed and written by subject experts.

Videos and Websites

- Age level: Grades PreK–12

- Why we love it: Search for pre-made, timely video collections centered on your learning objectives. Videos cover a wide range of content areas and topics.

- Why we love it: Discover informative videos that engage students with a variety of concepts.

- Why we love it: Explore biographical accounts of famous historical figures—from Ponce de Leon to Maya Angelou.

History at Home

- Why we love it: Investigate core history topics with infographics, articles, and videos from the History Channel.

3 Ideas for Teaching with Text Sets

There are many different ways that you can use text sets in the classroom—whether you’re teaching kindergarteners or high schoolers (or anyone in between).

Below are a few fresh ideas on how you can incorporate text sets in your classroom.

- Student-Created Text Sets

This project is ideal for the end of the school year and can be adapted for elementary students as well as high school.

Using books that they’ve read through the year, have students create their own text sets based on the theme or concept of their choice. This is a great way to give students more agency over their learning.

By creating thoughtful prompts, you can help students develop their critical thinking skills as they compare and contrast, analyze, determine, and cite pieces of text evidence to explain their rationale.

As a bonus, you’ll have a collection of recommendations for next year from your target audience—the students!

Jillian Heise outlines how she uses student-created text sets with her middle school students in this article from Choice Literacy .

- Rolling Text Sets

The concept of rolling text sets is simple—throughout a unit, provide students with your selection of texts gradually. Over time, the texts should increase in length and complexity.

Essentially, a rolling text set is a way to scaffold text sets for your students. By introducing students to the concepts in an incremental, sequential method, you can help them build their knowledge in a more manageable way.

Christine Boatman explains how she uses rolling text sets in her middle school classroom in this article from Edutopia .

- Cross-Curricular Text Sets

Text sets are a natural component of language arts, but how can they be used in other content areas like science or math? Here’s where collaborating with your co-teachers and colleagues will come in handy.

After you’ve determined your common theme, talk to language arts teachers and librarians to see if they have any suggestions. In an example from Middle Web , a preservice science teacher used the novel Wonder by R.J. Palacio as an anchor text for a collection about genetics. By working with teachers in other content areas, you can help students see the connections in what they’re learning.

If you’re new to creating text sets, book pairings are a great place to start. Jill Richardson writes, “ Pairing fiction and nonfiction texts is an authentic way to integrate Language Arts, Science, and Social Studies…It is a great way to build vocabulary and show children the same words in different genres.”

Amanda Wall provides other text set examples for content areas in this blog from Middle Web .

- What Does the Science of Reading Say About Comprehension?

Science of Reading research has identified text comprehension as one of the five pillars of literacy.

While there are many factors that contribute to a student’s ability to comprehend what they read, evidence supports that explicit instruction in comprehension strategies is effective in improving comprehension skills.

A 2021 study by the International Literacy Association underscores the role of vocabulary and background knowledge in reading comprehension. According to the study, “Many effective approaches to comprehension strategy instruction are set in the context of content knowledge building, suggesting the efficacy, and perhaps synergy, of simultaneously building content knowledge and improving students’ metacognition.”

Using text sets with comprehension instruction is an effective way to build contextual content knowledge and strong comprehension skills .

Want to expand your students’ perspectives, grow their vocabulary, and build their background knowledge? Text sets might be just the tool you need.

These project-based reading and writing tools are designed for students in the primary grades as each set pairs a Seedling reader and a Sprouts booklet based on theme, vocabulary, and level.

520 East Bainbridge Street Elizabethtown, PA 17022 Phone: 800.233.0759 Fax: 888.834.1303

- Privacy Policy

©2024 Continental. All Rights Reserved.

Found the perfect materials for your classroom? Email your shopping cart to your school/district contacts to request purchasing approval. Step #1: Save My Cart Step #2: Personalize My Email

Sample Praxis Core Writing Source-Based Essay, With Commentary

Questions about text types, purposes, and production make up 60% of your Praxis Core Writing score. This includes the Praxis Core Writing Source-Based Essay. And it includes the Praxis Core Writing Argumentative Essay . ( Praxis Core Writing revision-in-context questions also fall under the category of text types, purposes, and production.)

Today, we’ll look at a practice Source-Based essay question for Praxis Core Writing. This practice essay will include a full prompt — directions and two source passages. The passages will both cover the same topic from different perspectives. This prompt will be followed by a model Praxis Core Writing source-based essay that earns the full 6 points. (Both the Praxis Core Writing Source-Based essay and the Praxis Core Writing Argumentative essay are scored on a scale of 1-6.)

Example Praxis Core Writing Source-Based Essay Prompt

Directions: The following assignment requires you to use information from two sources to discuss concerns that relate to a specific issue. When paraphrasing or quoting from the two sources, cite each source used by referring to the author’s last name, the title, or any other clear identifier.

Assignment: Automatic teller machines (sometimes called ATMs or ATM machines) allow people to withdraw cash from their bank accounts remotely. ATM users insert their bank cards into the machine and request cash. The ATM then dispenses the cash and makes an electronic withdrawal from the user’s bank account. In this transaction, additional money is also drawn from the ATM user’s bank account in the form of ATM service fees. Both of the following sources address the relationship that ATM use has with bank accounting, and particularly whether ATM fees place an unfair financial burden on the people who use them.

Read the two passages carefully and then write an essay in which you identify the most important concerns regarding the issue and explain why they are important. Your essay must draw on information from BOTH of the sources. In addition, you may draw on your own experiences, observations, or readings. Be sure to CITE the sources whether you are paraphrasing or directly quoting.

Adapted from: Nym, Alex. Legal Theft: How Financial Service Fees Inhibit Capitalism. Madison, Wisconsin: Vanity Press. 2015. 81-82. Web. 13 Jun. 2016.

It seems incredibly unfair to have to pay money just to access your own money. Unfortunately, this form of highway robbery happens millions of times every day at ATMs across the nation. What makes ATM fees the most frustrating is their unpredictable costs. The costs themselves can vary widely. One ATM may have charge cardholders three or four times as much as another ATM. While these variations might theoretically create healthy competition among different privately owned ATM stations, in reality, consumers don’t have the time to explore every ATM in an area and find the best deal.

It seems that the ATM’s particular brand of legal theft is on the rise. Since ATM owners first began charging the bank account holders who use their machines, prices for ATM use have risen astronomically. To make matters worse, the actual bank that issues the bank card will often charge an additional fee to its hapless cardholders. This means that when someone uses an ATM to withdraw money from their bank account, they are not just charged a fee by the owner of the ATM. They pay a fee to the bank where they have their account. With this double charge, a small twenty dollar ATM withdrawal can have an additional cost of ten dollars, and sometimes more.

Aside from being unethical, ATM user fees are also financially harmful to consumers and to businesses. High ATM fees discourage people from spending money, and this means lower sales volumes at stores, restaurants, and other establishments.

Adapted from: Eincer, Brenda. Un-Nickeled and Un-Dimed: Financial Health for Individuals and Industry . Boston: Nosredna Publishing. 2014. 81-82. Web. 31 Mar. 2015.

People are quick to complain about the fees they pay at the ATM. But these fees are a small price to pay for the benefits of ATMs. These machines are helpful to both consumers and businesses.

Withdrawing money from an ATM has many advantages in spite of the potential fees. It’s easy to forget that any use of money from a bank account comes at a cost. Alternatives to ATM cash withdrawal also cost money, in the form of fees for payments made with cards, interest paid on credit card purchases, fees for writing checks, and so on. And bear in mind, those bank fees only are just the ones that impose costs on individual consumers. When people pay with a card, merchants themselves pay additional costs, in the form of “merchant service fees.” Merchant service fees are fees that sellers have to pay to the bank in order to process bank card transactions. These fees for receiving non-cash payments can be a real burden to business owners, but are avoidable when the customer pays in cash. Ultimately, ATMs may actually help customers and businesses save money.

Some claim that ATM fees have greatly increased in the last few decades, but this statement is only partly accurate. Yes, average fees have risen at ATMs that charge fees. However, there is a growing trend of no-fee ATMs. Increasingly, restaurants, stores, and other retail businesses are purchasing their own ATMs and offering cash withdrawals without fees to their customers. This practice allows businesses to reduce the merchant service fees they pay because their customers pay in cash. This is a win for consumers as well, as they are able to minimize ATM fees by patronizing certain establishments.

Sample Praxis Core Writing Source-Based Essay

ATM fees, the fees people pay to access cash from their bank accounts via automated teller machine, raise a number of socioeconomic issues due to their increasingly high costs. In his essay, Alex Nym complains of the “unfair” nature and “unpredictable costs” that people face when they want to access their personal funds through an ATM (“Legal Theft: How Financial Services Inhibit Capitalism”). Nym claims that average fees for ATM use have risen a great deal in the last 30 years. He also notes that many customers get double-charged when they use an ATM; first, the owner of the ATM charges a fee for ATM use. Then, the bank where the money is withdrawn from charges an additional fee for removing the cash from the account. Nym suggests that ATM fees are bad for the economy as a whole because they discourage people from taking out money and spending it.

Brenda Eincer, author of the book “Un-Nickeled and Un-Dimed: Financial Health for Individuals and Industry,” has a perspective that runs counter to Nym’s. Eincer feels that ATM fees are not unreasonable, and the people get many benefits in exchange for the cost of ATM use. Challenging Nym’s assumption that ATM use raises costs, Eincer points out that that there are also service fees for alternatives to ATM cash withdrawal. She asserts that using a debit or credit card or writing a check also have costs. This author also brings up the issue of the “merchant service” fees that businesses need to pay when they receive payments by card instead of by cash from an ATM. In Eincer’s opinion, ATM fees may be the better deal for both ATM users and the businesses where they shop. Finally, Eincer offers a different perspective than Nym’s with regards to rising ATM fees. She notes that while some ATMs charge more than before, many businesses now host no-fee ATMs to encourage onsite shopping.

Both authors agree that ATM use certainly has noticeable costs and that the highest ATM fees are higher than ever. The real debate is whether these costs are worth it. Nym and others who share his views would argue that the costs of ATM use have risen too high and ultimately discourage economic activity. On Eincer’s side of the debate, it seems possible that ATM costs are potentially cheaper than those associated with card and checkbook purchases. If that proves to be the case, then ATM use may actually benefit both shoppers and businesses.

Commentary on Sample Praxis Core Writing Source-Based Essay

This essay meets the top standards of the official score guide for the Praxis Core Writing Source-based essay. (See pages 35 and 36 of the official Praxis Core Writing Study Companion. )

The organization of this essay shows logic and sophistication. The essay frames the importance of the issue in the very first sentence. From there, the test-taker looks first at the perspective in Passage 1, and then at the views expressed in Passage 2. The person who wrote this essay organized the summary of the passages in a logical “point-counterpoint” arrangement. Eincer’s favorable views of ATM fees in Passage 2 are treated as a possible counterpoint to Nym’s negative verdict on ATM costs in the previous passage. At the end, the essay-writer pulls it all together by stating each author’s core thesis and comparing the rationale and implications for both perspectives.

This sample essay also meets the technical standards required for the full 6 points. The test-taker uses a variety of sentence structures as needed, and demonstrates a good range of vocabulary. Sources are also cited in a clear, consistent fashion.

David is a Test Prep Expert for Magoosh TOEFL and IELTS. Additionally, he’s helped students with TOEIC, PET, FCE, BULATS, Eiken, SAT, ACT, GRE, and GMAT. David has a BS from the University of Wisconsin-Eau Claire and an MA from the University of Wisconsin-River Falls. His work at Magoosh has been cited in many scholarly articles , his Master’s Thesis is featured on the Reading with Pictures website, and he’s presented at the WITESOL (link to PDF) and NAFSA conferences. David has taught K-12 ESL in South Korea as well as undergraduate English and MBA-level business English at American universities. He has also trained English teachers in America, Italy, and Peru. Come join David and the Magoosh team on Youtube , Facebook , and Instagram , or connect with him via LinkedIn !

View all posts

More from Magoosh

17 responses to “Sample Praxis Core Writing Source-Based Essay, With Commentary”

On one of my essays I ran out of time. I was finishing my last sentence in my conclusion when I was cut off. Will this hurt my score by a lot, or will they take into consideration that I just ran out of time, and look at what I completed? I was hoping for a 4 on this essay

It is not uncommon for essays to get cut off, and as long as the rest of your essay was written well, you should still be able to pull through this! Obviously you have to wait until the score report comes out officially, but you should be in decent shape. 🙂

Does the source based essay need to be 5 paragraphs

There is no requirement that the essay needs to be 5 paragraphs, as you can see on pages 24025 of the Test Companion , which provides scoring rubric for the source-based essay. In fact, the high-scoring sample essays in this PDF are not 5 paragraphs. The scorers are looking for whether your essay is well-written, logically organized, and insightful. They aren’t counting paragraphs 🙂

What score did you end up with, if you don’t mind me asking? I am getting ready to take the test and wondering how to plan for it myself.

I need help passing the praxis writing portion, is there anyplace to get tutored?

Hi Frankie,

Are you asking about the Praxis Core Writing test? We have a Premium Program which covers all three Praxis tests, including the Writing Test. Our video lessons cover everything you need to know for the Praxis, and we have plenty of practice questions to help you prepare. Give us a try with a free trial 🙂

Hello I am a bit confused, do I have to include a works cited page in addition to the in text citations? Thanks in advance!

You won’t need a works-cited page for this kind of Praxis Core Writing essay, Lauren. 🙂

Hi, For the Source Based essay, could I have a total of 4 paragraph? The first paragraph would be about the introduction for the essay, the 2 body paragraph would be about the summaries about the 2 articles and the the final paragraph would be about the conclusion of the whole entire essay? Do you think I need to add anything to the introduction paragraph(Like a thesis)?

A four or even five paragraph essay could also work, MT. And yes, you could include an introduction with a thesis. However, an extra introductory passage is not strictly necessary. If you are write a good 4 paragraph essay in the time limit, that’s not a bad thing. However, I still advise going for three paragraphs as seen in the sample essay. A more complex essay, if you can do it right, certainly won’t hurt your score. But on a timed exam, it’s simply safer to go for a simpler structure

Hey, does anyone know in what format you are required to cite (such as APA or MLA)? Do you cite the date of publication when you mention the author’s name and name of article, or do you cite the name of the article if you mention the author’s name? Or neither! I’m confused about how to cite or paraphrase…

Citing criteria are not strict for the essay, but you should make the source clearly identifiable. If you don’t mention the full title of an article in your essay, mention it in the citation. If you do mention the full article title in the regular text of your essay and you mention the author, then you can simply put the author’s name in parenthesis for subsequent references. What’s important is consistency of referencing format. Make sure the reader will have a clear idea of what you’re referencing. (If you’re worried about this, you can also avoid in-text citations all together and just directly reference the sources in your answer.)

I scored a 158 on praxis core writing. I plan to retake the test in a week. My weakness is grammar usage. What tips do you offer or suggest for me getting a passing score?

Sorry–this might not get to you in time! These blog post might help you: Grammar Rules for the Praxis Core How to study for Praxis Writing

I’ll be tested tomorrow!! I am nervous, English isn’t my first language. It was good reading some samples.