- Neurology Specialists

- Pediatricians

Education & Research

MaineHealth is advancing the practice of medicine and training the next generation of clinicians through high-quality research and education programs.

Maine Medical Center Department of Medical Education

Maine Medical Center (MMC) is Maine’s only academic medical center conducting cutting edge biomedical research that provides the most advanced treatment options for our patients. Since 1874, MMC has maintained a proud tradition of high-quality medical education and training. We are committed to providing medical students , residents and fellows with the knowledge and skills needed to become future leaders in medicine. MMC also partners with Tufts University School of Medicine (TUSM) to offer the Maine Track Program , an innovative curriculum that includes the unique aspects of rural clinical practice as well as training at major tertiary medical center. Learn more about medical education.

MaineHealth Institute for Research (MHIR)

MaineHealth Institute for Research supports and encourages a broad spectrum of research at MaineHealth ranging from basic laboratory-based research through translational research, which works to apply basic discoveries to medical problems, to clinical research, which studies the direct application of new drugs, devices and treatment protocols to patients, to health services research which seeks to use research methods to help improve and evaluate health care delivery programs and new technologies. View our annual report or visit the MHIR website .

MaineHealth Innovation

MaineHealth drives a culture of innovation by nurturing and funding innovative ideas across our system. Together we are solving health care challenges through new care team models, products, technology and services. Learn more about our innovation program.

MHIR supports and encourages a broad spectrum of research at, ranging from basic laboratory-based research to translational research, clinical research and health services research.

Students, Residents & Fellows

We support over 240 residents and fellows in over 20 ACGME approved programs.

Hannaford Simulation Center

The Hannaford Center for Safety, Innovation and Simulation offers high-tech and realistic simulation.

Continuing Medical Education

Our mission is to promote excellence in medical education in Maine.

- History, Facts & Figures

- YSM Dean & Deputy Deans

- YSM Administration

- Department Chairs

- YSM Executive Group

- YSM Board of Permanent Officers

- FAC Documents

- Current FAC Members

- Appointments & Promotions Committees

- Ad Hoc Committees and Working Groups

- Chair Searches

- Leadership Searches

- Organization Charts

- Faculty Demographic Data

- Professionalism Reporting Data

- 2022 Diversity Engagement Survey

- State of the School Archive

- Faculty Climate Survey: YSM Results

- Strategic Planning

- Mission Statement & Process

- Beyond Sterling Hall

- COVID-19 Series Workshops

- Previous Workshops

- Departments & Centers

- Find People

- Biomedical Data Science

- Health Equity

- Inflammation

- Neuroscience

- Global Health

- Diabetes and Metabolism

- Policies & Procedures

- Media Relations

- A to Z YSM Lab Websites

- A-Z Faculty List

- A-Z Staff List

- A to Z Abbreviations

- Dept. Diversity Vice Chairs & Champions

- Dean’s Advisory Council on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, Queer and Intersex Affairs Website

- Minority Organization for Retention and Expansion Website

- Office for Women in Medicine and Science

- Committee on the Status of Women in Medicine Website

- Director of Scientist Diversity and Inclusion

- Diversity Supplements

- Frequently Asked Questions

- Recruitment

- By Department & Program

- News & Events

- Executive Committee

- Aperture: Women in Medicine

- Self-Reflection

- Portraits of Strength

- Mindful: Mental Health Through Art

- Event Photo Galleries

- Additional Support

- MD-PhD Program

- PA Online Program

- Joint MD Programs

How to Apply

- Advanced Health Sciences Research

- Clinical Informatics & Data Science

- Clinical Investigation

- Medical Education

- Visiting Student Programs

- Special Programs & Student Opportunities

- Residency & Fellowship Programs

- Center for Med Ed

- Organizational Chart

- Committee Procedural Info (Login Required)

- Faculty Affairs Department Teams

- Recent Appointments & Promotions

- Academic Clinician Track

- Clinician Educator-Scholar Track

- Clinican-Scientist Track

- Investigator Track

- Traditional Track

- Research Ranks

- Instructor/Lecturer

- Social Work Ranks

- Voluntary Ranks

- Adjunct Ranks

- Other Appt Types

- Appointments

- Reappointments

- Transfer of Track

- Term Extensions

- Timeline for A&P Processes

- Interfolio Faculty Search

- Interfolio A&P Processes

- Yale CV Part 1 (CV1)

- Yale CV Part 2 (CV2)

- Samples of Scholarship

- Teaching Evaluations

- Letters of Evaluation

- Dept A&P Narrative

- A&P Voting

- Faculty Affairs Staff Pages

- OAPD Faculty Workshops

- Leadership & Development Seminars

- List of Faculty Mentors

- Incoming Faculty Orientation

- Faculty Onboarding

- Past YSM Award Recipients

- Past PA Award Recipients

- Past YM Award Recipients

- International Award Recipients

- Nominations Calendar

- OAPD Newsletter

- Fostering a Shared Vision of Professionalism

- Academic Integrity

- Addressing Professionalism Concerns

- Consultation Support for Chairs & Section Chiefs

- Policies & Codes of Conduct

- Health & Well-being

- First Fridays

- Fund for Physician-Scientist Mentorship

- Grant Library

- Grant Writing Course

- Mock Study Section

- Research Paper Writing

- Funding Opportunities

- Join Our Voluntary Faculty

- Faculty Resources

- Research by Keyword

- Research by Department

- Research by Global Location

- Translational Research

- Research Cores & Services

- Program for the Promotion of Interdisciplinary Team Science (POINTS)

- CEnR Steering Committee

- Experiential Learning Subcommittee

- Goals & Objectives

- Issues List

- Print Magazine PDFs

- Print Newsletter PDFs

- YSM Events Newsletter

- Social Media

- Patient Care

INFORMATION FOR

- Residents & Fellows

- Researchers

Medical Education (MHS-MedEd) Track

This two-year degree program in the Medical Education track features an education research project and includes a comprehensive curriculum for individuals interested in developing a career in the field of medical health.

The degree course work includes a research project, core curriculum and elective courses. Students work within an individualized learning plan that is designed to facilitate their development as educators, scholars, and leaders in medical education.

Graduates of the program will be prepared to contribute to the education community at Yale School of Medicine and the broader field of medical education, both nationally and internationally.

On this Page

Program objectives, course & graduation requirements, time allowance & department commitment.

- Current Students & Alumni

Contact Us & Track Leadership

- Design, implement, and disseminate an education research project.

- Gain practical educational experience though active involvement in graduate and undergraduate medical education activities.

- Develop proficiency to serve as a leader in medical education and medical education research.

MHS Required Courses

- IMED 625 – Principles of Clinical Research – Summer Semester (July)

- IMED 630– Ethical Issues in Biomedical Research, which is offered during the fall semester on Tuesdays 3:30-5:00 pm, and conflicts with MD506.

- Med Ed Track Students take: SecEd 511 – Responsible Conduct of Research (RCR) offered on various dates beginning in the fall semester through the spring semester. Six total sessions, each two hours long.

- IMED 645 – Introduction to Biostatistics in Clinical Investigation – offered during summer semester July-August

Medical Education Track Required Courses

First-year student requirements:.

MD506 – Medical Education: Theory Research and Practice – primarily Tuesdays 4-7:00 pm

- Summer Semester, including seven classes in July and August

- Fall Semester, including 13 classes with 5 Research in Progress Sessions

- Spring Semester, including 13 classes with 3 Research in Progress Sessions

Second-year Student Requirements:

- Fall semester: 5 Research in Progress Sessions

- Spring semester: 3 Research in Progress Sessions

- Leadership development: There is also a leadership development course shared across MHS tracks.

Additional Graduation Requirements:

Tracked by the Center for Medical Education on the Individual Learning Plan form:

- Write and defend a thesis

- Graduate research presentation attended by all current students

- Manuscript ready for publication

- Scheduled meetings with mentors and Center for Medical Education faculty, as specified

- Submission of information on research products that stem from the MHS-Medical Education work (e.g., manuscript, publication, presentations, grants)

- Submission of updated Yale CV Parts 1 and 2 with any products (e.g., presentations, talks, workshops, and publications) resulting from the research highlighted

This is a two-year program requiring a 35% time commitment, which must be approved by your department chair or division chief in writing. This program is intended for those who plan to pursue a career at Yale. While this is not a strict requirement, because of Yale’s investment in the participant, it will be an important consideration.

If a participant is unable to complete the degree in two years, approval of an extension is required by the Yale MHS Degree Program and the Track Academic Director.

Graduation Candidates - May 2025

Clinical Fellow

Associate Professor of Medicine (General Medicine); Director of Diversity, Equity and Inclusivity, GME, VA; Associate Program Director, Internal Medicine Residency Program, Department of Medicine; Vice-Chair of DEI at VACHS, Veterans Affairs Healthcare System of CT

Jennifer Rockfeld, MD View Full Profile

Graduation Candidates - May 2024

Assistant Professor of Psychiatry; Director of Social Justice and Health Equity (SJHE) Education, Adult Psychiatry

Hospital Resident

Clinical Associate

Assistant Professor of Anesthesiology; Co-Director Yale Adult ECMO Program, Cardiac Anesthesiology Leadership; Associate Director Adult Cardiothoracic Anesthesiology Fellowship, Cardiac Anesthesiology Leadership

Assistant Professor of Medicine (Medical Oncology)

Assistant Professor of Surgery (Plastic); Plastic Surgery Residency, Associate Program Director, Plastic & Reconstructive Surgery; Plastic Surgery Clerkship Director, Department of Surgery

Instructor of Medicine (General Medicine)

Please contact Center for Medical Education Director of Programs, Dorothy DeBernardo , with questions.

Professor of Pediatrics (General Pediatrics); Associate Dean for Teaching and Learning, General Pediatrics; Director of the Center for Medical Education, Pediatrics

Coronavirus (COVID-19): Latest Updates | Visitation Policies Visitation Policies Visitation Policies Visitation Policies Visitation Policies | COVID-19 Testing | Vaccine Information Vaccine Information Vaccine Information

Department of Medicine

Medical education research and scholarship.

Advancing the process of educating the people who care for our community

The University of Rochester Department of Medicine is a leader in medical education innovation. We’re here to support scholars to develop, investigate, and disseminate this work. Our goal is to move the field of medical education forward at the undergraduate, graduate, and continuing professional education level, incorporating our interprofessional learners, and supporting an environment where diverse learners and faculty can thrive.

Request a Consult

Request a consult on your medical education research or scholarly project.

Request a consult

Resource Center

Developing your research question, methods, writing, dissemination

- Our curated collection of resources in Miner Library to support medical education scholars (coming soon!)

- Research Subjects Review Board

Upcoming Events

Department of medicine medical education works-in-progress.

Presenter: Alec O'Connor, MD, MPH

Friday, March 29, 2024 Noon-12:50pm

Contact [email protected] or [email protected] for zoom info

Annual Faculty Development Colloquium

Wedmesday, June 5, 2024 8am-1:00pm More information

Learn more about the Ritchie Fellowships

Scholar Highlight

Meet christopher mooney, phd, mph, ma.

Chris’ education scholarship focuses on evaluating and improving the quality of narrative assessments of learners, and education research methods. In response to the limited reliability and meaningfulness of numerical (e.g. Likert scale) evaluations, there has been a shift in medical education toward improving the quality and usefulness of narrative (free text) evaluations. Chris worked with a team to develop an instrument to evaluate the quality of narrative evaluations, then led studies revealing important factors that correlate with the quality of narrative evaluations. In addition to his own research program, Chris has long been a sought-after collaborator on medical education research. He has chaired the NEGEA Medical Education Scholarship, Research, and Evaluation Committee and directed the AAMC’s Medical Education Research Certificate program, where he teaches quantitative methods. Currently serving as the President-elect of the Society of Directors of Research in Medical Education (SDRME), Chris holds several roles at the University of Rochester School of Medicine including Director of Assessment and Director of the students' Medical Education Pathway. Outside of these pursuits, he is a husband and father of four children—the bulk of which are growing tired of his corny puns and dad jokes. The Mooney family motto is “Well, that escalated quickly.”

Medical Education

Make the AAMC your medical education home. Explore what we have to offer, from learning events, trainings, and professional development conferences to programs, initiatives, and scholarship on key and emerging topics. Get involved, advance your career, and help move the field of medical education forward.

Areas of Focus

'Qualitative' and 'quantitative' methods and approaches across subject fields: implications for research values, assumptions, and practices

Nick Pilcher & Martin Cortazzi

Carrying out research in Nepal: perceptions of scholars about research environment and challenges

Prakash Kumar Paudel & Basant Giri

A Medical Science Educator’s Guide to Selecting a Research Paradigm: Building a Basis for Better Research

Megan E.L. Brown & Angelique N. Dueñas

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

Is the field of medical education (Med Ed) research an interdisciplinary field? This question may sound odd to members of the field as it is generally presumed that Med Ed research draws on the insights, methods, and knowledge from multiple disciplines and research domains (e.g. Sociology, Anthropology, Education, Humanities, Psychology) (Albert et al. 2020 ). This common view of Med Ed research is echoed and reinforced by the narrative used by leading Med Ed departments and research centres to describe their activities. Words and expressions such as “interdisciplinarity,” “multidisciplinary perspective,” and “opportunities for interdisciplinary collaboration” are frequently used to depict their mission, goals, and the academic training they provide to their students. Footnote 1 Researchers in Med Ed also often characterise the field as being a hybrid domain, building on various methodologies and disciplines (Gruppen 2014 ; Gwee et al. 2013 ; O’Sullivan et al. 2010 ; Teodorczuk et al. 2017 ).

In this article, we examine the assumption that Med Ed research is an interdisciplinary field. This wide-spread assumption has not yet been investigated. To date, there is no empirical evidence that either supports or calls into question that the field is interdisciplinary. Answering this question may impact the development of Med Ed research as members of the field will be able to make an informed decision about how they would like to see the field develop. In this article, we define interdisciplinarity, following the National Academy of Science’s definition ( 2005 ), as communication and collaboration between researchers across academic disciplines and research domains.

One effective method to investigate whether Med Ed research is interdisciplinary is to conduct a bibliometric analysis (Larivière and Gingras 2014 ) of articles and journals cited by Med Ed researchers. Bibliometrics offer a “set of methods and measures for studying the structure and process of scholarly communication” (Borgman and Furner 2002 , p. 2). Bibliometric data can shed light on the knowledge that informs Med Ed academics in their published work and, concurrently, trace the contour of the intellectual landscape of the Med Ed research field. By using bibliometric data, we are studying cross-disciplinary communication. We are not attempting to make any claims about the collaborative dimension of interdisciplinarity, as that is beyond the scope of this methodology and this paper. We examined one facet of cross-disciplinary communication, which is the flow of ideas, concepts, and knowledge from other disciplines into the Med Ed field.

A growing body of research shows that cross-disciplinary exchange is a common feature of academic life. Rob Moore coined the term “routine interdisciplinary” to capture this practice ( 2009 ). Jacobs and Frickel ( 2009 ), Jacobs ( 2014 ), Larivieres and Gingras ( 2014 ), and Van Noorden ( 2015 ) used bibliometrics to show that it is a customary practice for scientists to cite the work from colleagues outside their discipline. We build on this body of work in this study by examining Med Ed researchers’ distinct citation practice. We use these citation practices as a way to trace which disciplines and domains of knowledge are drawn upon by Med Ed researchers to inform their work.

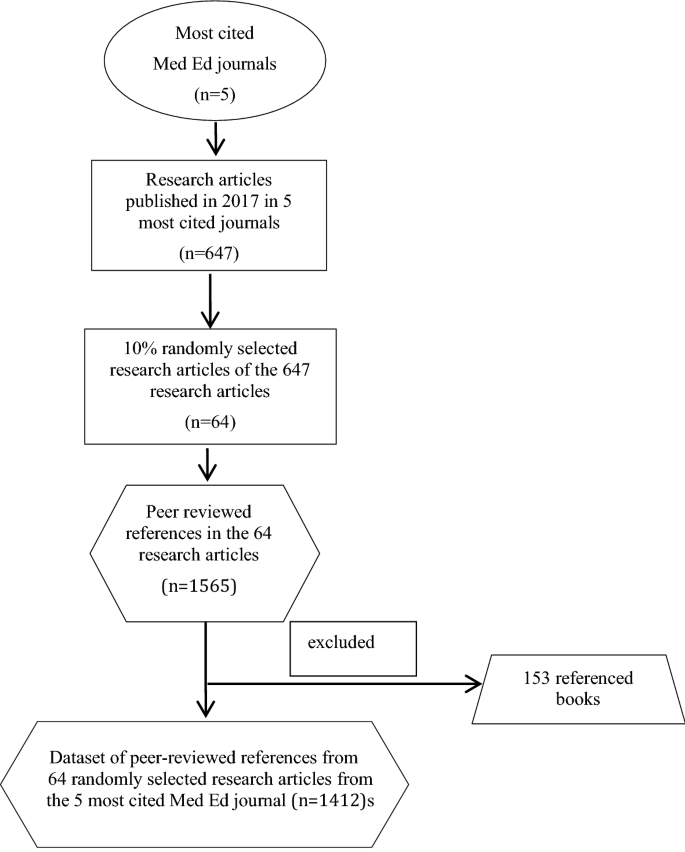

Journals and research articles sampling rationale and procedure

The first step in our bibliometric analysis was identifying the five Med Ed journals with the highest impact factor by using the 2017 Journal Citation Reports (JCR) (2018 was not available at the time of data collection). The JCR category used was “Education, Scientific Disciplines,” which is where Med Ed journals are classified by Clarivate Analytics. The five journals with the highest impact factor in Med Ed (at the time we conducted our research) were: Academic Medicine , Medical Education , Advances in Health Sciences Education , Medical Teacher , and BMC Medical Education (see Table 1 ). Our goal was not to create a sample of journals representative of the whole range of publications in the Med Ed research field, but to select the most cited journals, i.e., those that are the most influential in the field.

The second step was selecting a sample of articles published within these five journals. Since the goal of our project was to study the patterns of knowledge circulation within Med Ed research, we included research articles published in 2017 in the five journals. The research articles from 2017 from each journal were exported from Web of Science and cross-checked manually with each journal’s Table of Contents. For feasibility, we included only a subset of the total research articles published in 2017. Using a random number generator (random.org), we selected 10% of the research articles published in each journal (see Table 1 ). The procedure we followed for each journal is exemplified by the steps we took to select articles from the journal Academic Medicine which published 134 research articles in 2017. First, we numbered 1–134 all the research articles published in the journal in 2017. Second, we set the number generator minimum as 1 and maximum as 134, and then we generated 13 random numbers (i.e., 10% of the 134 research articles). For our study dataset, we used the 13 articles that matched the randomly generated numbers. We repeated this procedure for all selected journals. In total, 64 articles were selected to be included in our sample across the five journals. Table 1 outlines the number of research articles published in each of the five targeted journals in 2017 and the number of articles randomly selected per journal based on the 10% ratio. Reviews, commentaries, letters, editorials, and other non-primary research formats were excluded from our sample as they are not research (e.g. Academic Medicine Last Page, Medical Teacher Twelve Tips, Advances in Health Sciences Education Reflection articles, Medical Education When I Say).

We decided to sample 10% of the research articles published in each journal for feasibility reasons. Our goal was not to be exhaustive but to ensure a reasonable representation of the work without skewing the selection in favour of any one research area or discipline. We have no reason to believe that the articles included in our sample are meaningfully different in terms of reference patterns from those not included.

References sampling

The third methodological step was constructing our references dataset from the 64 randomly selected research articles. We exported the references for each of the 64 articles from Web of Science and cross-checked manually with the article PDFs to ensure all references were captured. We included references (n = 1412) from peer-reviewed journals as our unit of analysis.

In total, 153 references cited books across the 64 articles included in our sample, in comparison with 1412 references which cited peer-reviewed journal articles. The ratio of book references to journal references is therefore: 1412:153 which is just over nine. Proportionally, this means that there are nearly nine times more references from journals than from books. We did, however, review the titles of these books as part of our initial analysis. There was no particular trend arising from the book references that significantly alter the patterns observed across the articles. For the remainder of this paper, we will focus on the analysis of the 1412 journal articles referenced, which was our dataset. Figure 1 outlines the steps we took constructing our references dataset.

Procedure used to construct the dataset of peer-reviewed cited references from the five most cited Med Ed journals

Data analysis

To analyse the references and examine which disciplines Med Ed researchers draw from, we inductively developed a typology of six knowledge orientations, which we labelled knowledge clusters (see Table 2 ). These knowledge clusters were developed by examining the “Aims and Scope” of the journals cited by the 1412 references. All journals have a web page dedicated to their “Aims and Scope” where they describe their mandate and the type(s) of research they consider in alignment with their editorial orientation. The details provided typically list what discipline(s), topic(s), research area(s), and method(s) fall within their scope. The categorisation procedure we followed is similar to the one followed by qualitative researchers when conducting thematic analysis: in both types of research, categories, or clusters, are gradually developed through an iterative process of inclusion, exclusion, expansion, and division. Clusters take their final shape only when the analysis of new data (quotes in qualitative research, journals in our study) is completed. This inductive procedure should not be confused with the statistical cluster analysis method used in quantitative studies.

The six inductively developed knowledge clusters served as our conceptual map to categorise the 1412 references. For example, a reference from the journals Journal of the American Medical Association (JAMA) or the New England Journal of Medicine ( NEJM ) was classified within the Applied Health Research knowledge cluster because JAMA and NEJM , based on their aims and scope, are two journals whose primary research orientation is applied health research (in contrast, for example, to basic or disciplinary health research). Another example is the journal Simulation in Healthcare . We categorised this journal within the Interdisciplinary Health knowledge cluster because its main focus is healthcare simulation technology (which is a research topic, not a discipline) and it defines itself as a multidisciplinary publication. In cases where the information posted on the aims and scope web page was insufficiently detailed or unclear, members of the research team (MA and SL) read articles published in the recent issues of the referenced journals before categorising. In order to provide as much detail as possible on the journal categorisation, we list in Table 2 the six journals with the highest number of references for each cluster. The detailed list will help elucidate the groupings made therein and the knowledge orientation of each cluster.

We chose to design our groupings of journals as inductively developed “clusters” instead of “categories” since the type of data we are working with (i.e., references, journals, and ultimately areas of knowledge production) is inherently porous. The notion of cluster, more than category, better reflects this porosity. All journals within a cluster share a key characteristic (for example, being topic-centered, disciplinary, or education-focused); however, a number of journals may also share aspects with, or overlap onto, a neighboring cluster. For example, the journal Educational and Psychological Measurement was included in the Topic-Centered knowledge cluster because its primary focus is measurement; however, articles in this journal may tangentially address educational or psychological issues. The assignment of any journal to a knowledge cluster was based on its predominant characteristics. The clustering was performed by MA and SL.

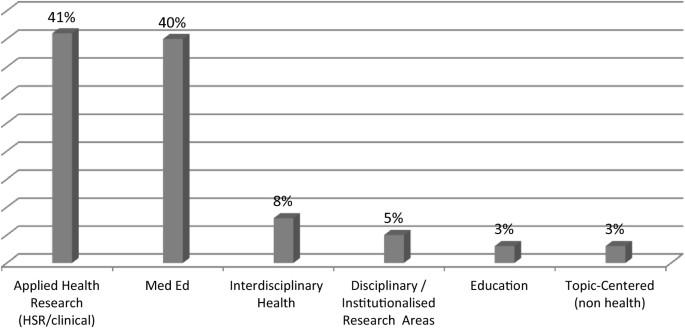

Citation patterns in medical education journals

The most striking finding is the steep discrepancy between, on the one hand, the Applied Health Research and Med Ed knowledge clusters and, on the other hand, the other four clusters (see Fig. 2 ). The Applied Health and Med Ed clusters cover 81% of all references, leaving 19% distributed among the other knowledge clusters. This pattern suggests that the field of Med Ed research stands predominantly on two knowledge pillars. These pillars are health services research and clinical research (which represent 41% of the references) and Med Ed (which represents 40% of the references). The quasi-hegemonic position held by these two knowledge clusters confines the other sources of knowledge to a peripheral role within the Med Ed research field.

Distribution of peer-reviewed references (n = 1412) per knowledge cluster. Data presented in %

When Med Ed researchers seek knowledge from outside their field and the applied health research field, they primarily turn to interdisciplinary health research (see Interdisciplinary Health in Fig. 2 ). The journals included in this cluster cover a wide spectrum of topics, from drugs and alcohol dependence to women’s health, health policy, simulation, and religion and health. One key characteristic of the journals in this cluster is that some of the articles draw on the knowledge developed in the core disciplines and institutionalised research areas (organisation studies, cognitive sciences, sociology, etc.). While their mandate is usually not to expand theory (but rather to report on empirical research), it is not uncommon for a number of these journals, such as Social Science & Medicine , to publish articles offering a conceptual understanding of phenomena. Therefore, through the journals included in the Interdisciplinary Health knowledge cluster, Med Ed researchers have a connection with a more comprehensive source of knowledge that is both basic and applied.

As shown in Fig. 2 , the Interdisciplinary Health knowledge cluster stands in third position in terms of its overall volume of references. Yet, this volume represents only 8% (n = 115 references) of the 1412 references in our sample used by Med Ed researchers. It follows that the capacity of this body of knowledge to influence the Med Ed academic culture is likely to be relatively marginal.

The bodies of literature cited by Med Ed researchers decreases substantially when these references come from journals outside health research. The next three clusters in Fig. 2 (the Disciplinary and Institutionalised Research Areas cluster, the Education cluster, and the Topic-Centered (non-health) cluster) respectively represent only 5%, 3%, and 3% of all references. One would expect that Med Ed researchers draw upon these research areas more—especially education, as it is a cognate field. Our data suggest that, to the contrary, Med Ed researchers tend to marginally engage with this literature.

In order to paint a more detailed picture of the disciplinary knowledge entering the Med Ed intellectual space, we examine the Disciplinary and Institutionalised Research Areas knowledge cluster more closely. We noticed that one discipline (psychology) largely exceeded the others, which has the effect of further narrowing down the range of disciplinary knowledge entering the Med Ed field. Among the 77 references contained in this cluster, 55 (71%) are from psychology journals (including seven from psychology journals applied to education). The remaining references are distributed across nine disciplines and research areas: sociology (n = 6), business, management and organisations studies (n = 5), social psychology (n = 3), biology (n = 2), the humanities (n = 2), neuropsychology (n = 1), physiology (n = 1), statistics (n = 1), and cognitive science (n = 1).

One of the common goals of the journals included in the Disciplinary and Institutionalised Research Areas knowledge cluster is to advance both basic and applied disciplinary and interdisciplinary knowledge through cross-communication between empirical research and theory. Based on the citation patterns revealed by our data, it seems that this mix of disciplinary, basic/applied, and theoretical knowledge does not easily find its way into the Med Ed research field. While psychology may be utilized by Med Ed researchers, the other disciplines are essentially absent.

Our findings suggest that when Med Ed researchers seek knowledge from outside their field, they predominantly draw from one research area (i.e., applied health). This practice seems to show some discrepancy in regard to the commonly accepted definition of interdisciplinarity, which emphasizes knowledge flow between various research communities (National Academy of Science 2005 ). The high percentage of citations from just one knowledge cluster outside Med Ed suggests that the knowledge landscape of the field could be portrayed as being only tangentially interdisciplinary. With 41% of the references coming from health services research and clinical journals, the academic group with whom Med Ed researchers have the closest connection is the applied health research community. This privileged connection risks excluding other research communities and these other robust bodies of knowledge. These other research communities are the social scientists, the natural scientists, and the humanities scholars. It seems, therefore, that interdisciplinarity for Med Ed researchers means, first and foremost, drawing on and being inspired by clinical and health services research and by the medical epistemic culture underpinning these knowledge domains. Basic, (inter)-disciplinary, and theory-based knowledge seems to be infrequently used by Med Ed researchers and therefore is unlikely to influence the field in a meaningful way. In light of this, one wonders how the Med Ed research field may best be characterised: as an interdisciplinary sub-field of education or as a sub-field of health research? The difference is potentially subtle, but reflecting on this positioning draws attention to how we might think about the dynamics of knowledge production and the future of Med Ed.

If Med Ed researchers predominantly use knowledge developed in health services research and the clinical sciences, it is legitimate to ask whether there could be a misalignment between the body of knowledge drawn from and their research object—education—which is primarily a social science object. If education is a multifaceted phenomenon, how can it be comprehensively studied if researchers draw on a relatively narrow range of knowledge sources, methods, and approaches? Specifically, how can the sociological, psychological, political, cultural, and historical dimensions embedded in the practice of education be studied and understood, without substantive inputs from the academic disciplines focusing on understanding these aspects (Bridges 2017 ; Furlong 2013 )?

Further, the lack of engagement with wider developments in disciplinary knowledge may raise a number of challenges: Med Ed researchers may not have an in-depth understanding of the literature coming from these fields and have difficulty teaching disciplinary knowledge to their students, further hindering knowledge communication with scholars outside Med Ed. Because of the health orientation and relative insularity of the field (as our data suggest), Med Ed researchers could also find themselves asking questions that researchers and practitioners within the Med Ed field may find interesting and novel, but that might have already been investigated by researchers in the social and natural sciences. This would be a lost opportunity to build Med Ed knowledge upon existing foundations, and could potentially undermine the status of the Med Ed field in the broader academic market where it is common practice to borrow ideas, concepts, and methods from other disciplines (Albert et al. 2020 ; Jacobs 2014 , Larivière and Gingras 2014 ; Moore 2011 ). Research fields with a low participation in knowledge exchange across the university may potentially be at risk of being left behind when new theoretical and methodological developments occur (Jacobs 2014 ). Being “out of the loop” may also result in Med Ed researchers potentially applying a theoretical framing or methodological approach that has already been debated, dismissed, or evolved in other disciplines.

The goal of this study was to examine the widespread assumption that Med Ed research is an interdisciplinary field. Our findings show that this belief is not convincingly supported by empirical data and that the knowledge entering, circulating, and informing Med Ed research comes mostly from the health research domain. It behooves members of the Med Ed field to reflect on the current knowledge flow: is the health orientation of the field appropriate and sufficient to pursue education research in health care or is a diversification of knowledge needed? We see this as a contribution to the understanding of what the Med Ed field is, and what could be done to further its development.

Our study is not without limitations. A larger sample may have offered a more refined picture of the citation practices of Med Ed researchers. Also, since we have not used a comparative design, we cannot interpret our findings in comparison with the knowledge flow occurring in other research communities. This is something worth studying in future projects.

Further research should also explore the reasons why Med Ed researchers tend to predominantly cite literature from health rather than from non-health disciplines. Perhaps Med Ed researchers build their rationale for education research from the observation of clinical problems (i.e. the needs of a particular patient population indicate a need for further clinical education), but do not go far beyond the clinical rationale in their literature searches. Another reason could be that clinical and health services research journals are the most familiar to Med Ed researchers, perhaps the most easily accessible and discussed in their academic environment. It could also be that researchers in the Med Ed field view Education and the social sciences as having little to contribute to education in health care settings. Investigating these questions will help develop a better understanding of the factors influencing knowledge production in Med Ed research and situate the field among other education research fields. The types of knowledge drawn upon have implications for how education interventions are designed and how we train future generations of Med Ed researchers.

The two following quotes illustrate the interdisciplinary narrative used by Med Ed departments and research centres to describe the nature of their core activities: “The Centre for Education Research and Innovation is an interdisciplinary, collaborative research group exploring health professions education research” (Centre for Education Research and Innovation, Western University 2019 ). “Health sciences education research draws on theories and methodologies from across myriad research traditions.” (Centre for Medical Education, McGill University 2019 ). Other examples of interdisciplinary narratives can be found on the web site of the School of Health Profession Education, Maastricht University ( 2019 ), the Centre for Health Education Scholarship, University of British Columbia ( 2019 ), the Health Professions Education Research PhD Program, University of Toronto ( 2019 ), the Department of Innovation in Medical Education, University of Ottawa ( 2019 ) and Chang Gung Medical Education Research Center, Chang Gung University ( 2019 ).

Albert, M., Friesen, F., Rowland, P., & Laberge, S. (2020). Problematizing assumptions about interdisciplinary research: Implications for health professions education research. Advances in Health Sciences Education .

Borgman, C. L., & Furner, J. (2002). Scholarly communication and bibliometrics. Annual Review of Information Science and Technology, 36 (1), 3–72.

Google Scholar

Bridges, D. (2017). Philosophy in educational research. Epistemology, ethics, politics and quality . Cham: Springer.

Centre for Health Education Scholarship, University of British Columbia. Retrieved August 26, 2019, from https://ches.med.ubc.ca/about-ches/strategic-plan/ .

Centre for Medical Education, McGill University. Retrieved August 26, 2019, from https://www.mcgill.ca/centreformeded/research-activities/cross-cutting-goals-and-strategies .

Centre of Education Research & Innovation, W. University. Retrieved August 26, 2019, from https://www.schulich.uwo.ca/ceri/research/index.html .

Chang Gung Medical Education Research Center, Chang Gung University. Retrieved August 26, 2019, from https://www1.cgmh.org.tw/cgmerc/view/about.aspx?tMenuNameId=9 .

Department of Innovation in Medical Education, University of Ottawa. Retrieved August 26, 2019, from https://med.uottawa.ca/department-innovation/research/support-your-research .

Furlong, J. (2013). Education. An anatomy of the discipline . New York: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Health Professions Education Research PhD Program, University of Toronto. Retrieved August 26, 2019, from https://ihpme.utoronto.ca/academics/rd/hper-phd/ .

Gruppen, L. D. (2014). Humility and respect: Core values in medical education. Medical Education, 48 (1), 53–58.

Article Google Scholar

Gwee, M. C. E., Samarasekera, D. D., & Chong, Y. (2013). APMEC 2014: Optimising collaboration in medical education: Building bridges connecting minds. Medical Education, 47 (s2), iii–iv.

Jacobs, J. A. (2014). In defense of disciplines interdisciplinarity and specialization in the research university . Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jacobs, J. A., & Frickel, S. (2009). Interdisciplinarity: A critical assessment. Annual Review of Sociology , 35 , 43–65.

Larivière, V., & Gingras, Y. (2014). Measuring interdisciplinarity. In B.Cronin, & C. Sugimoto (Eds.), Beyond bibliometrics: Harnessing multidimensional indicators of scholarly impact (pp. 187–200). Cambridge: MIT Press.

Moore, R. (2011). Making the break: Disciplines and interdisciplinarity. In F. Christie & K. Maton (Eds.), Disciplinarity: Functional linguistic and sociological perspectives (pp. 87–105). London: Continuum.

National Academy of Sciences. (2005). Facilitating Interdisciplinary research . Washinton: The National Academies Press.

O’Sullivan, P. S., Stoddard, H. A., & Kalishman, S. (2010). Collaborative research in medical education: A discussion of theory and practice. Medical Education, 44 (12), 1175–1184.

School of Health Profession Education, Maastricht University. Retrieved August 26, 2019, from https://she.mumc.maastrichtuniversity.nl/mission-vision-societal-impact-0 .

Teodorczuk, A., Yardley, S., Patel, R., Rogers, G. D., Billett, S., Worley, P., Hirsh, D., & Illing, J. (2017). Medical education research should extend further into clinical practice. Medical Education, 51 (11), 1092–1100.

Van Noorden, R. (2015). Interdisciplinary research by the numbers. Nature, 525 , 306–307.

Download references

Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (Grant Nos. 435-2016-0111 and 611-2017-0493).

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Wilson Centre, Department of Psychiatry, University of Toronto, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada

Mathieu Albert

Wilson Centre, Department of Occupational Science and Occupational Therapy, University of Toronto, University Health Network, Toronto, Canada

Paula Rowland

Centre for Faculty Development, Faculty of Medicine, University of Toronto at St. Michael’s Hospital, Unity Health Toronto, Toronto, Canada

Farah Friesen

School of kinesiology and physical activity sciences, Université de Montréal, Montreal, Canada

Suzanne Laberge

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Mathieu Albert .

Additional information

Publisher's note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Albert, M., Rowland, P., Friesen, F. et al. Interdisciplinarity in medical education research: myth and reality. Adv in Health Sci Educ 25 , 1243–1253 (2020). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-09977-8

Download citation

Received : 23 September 2019

Accepted : 15 June 2020

Published : 24 June 2020

Issue Date : December 2020

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s10459-020-09977-8

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Interdisciplinarity

- Disciplines

- Medical education research

- Citation analysis

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- ACGME Accredited Programs

- CPME Accredited Programs

- AEGD Dental Accredited Program

- Medical Clerkships

- Postgraduate Sub-Internships

- Department of Research

- Faculty-Scholar

- Resident-Scholar

- Team 11 Volunteers

- Research Rotation – Fellows

- Research Partner Organizations

- Continuing Medical Education

- Institutional Review Board (IRB)

- Miami Lifestyle

- Department of Research and Academic Affairs

- About the Department of Research and Academic Affairs

- Department Achievements

- Program Spotlight

- Residents & Fellows

- Templates for Research and Scholarly Work

- Global Research Collaboration Network

- Research Internship Opportunity

- Faculty Development

- Department Newsletters

ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT

Our department’s mission is to foster programs that shall promote the interest of clinicians to conduct research, generate knowledge, and advance healthcare. We assist medical Residents and Fellows in:

- Developing skills for the formulation of scholarly work such as posters, presentations, review of literature, and quality improvement.

- Developing foundation skills for research inclusive of formulation of a research question, access and analyze data, review pertinent literature as well as prepare a well-organized research presentation.

- Promote the research and scholarly work of residents, fellows and faculty of Larkin Community Hospital.

- Work on a Research Project from conception through publication.

- Preparing research presentations for Annual Scientific Conferences.

- Promote understanding of Institutional Review Board and relates processes.

- Providing learning experiences and resources for residents and fellows to help them complete their own research projects.

MEET OUR TEAM MEMBERS

Martha Echols, PhD Vice President Department of Research and Academic Affairs

Sultan S. Ahmed, MD Associate Vice President & Ombudsman for GME Department of Research and Academic Affairs

Joseph Hasselbach Coordinator Department of Research and Academic Affairs

Sujan Poudel, M.D Coordinator Department of Research and Academic Affairs

Reach Out To Us Email: [email protected] Phone: 305-284-7567 Office: Room 601, 7000 SW 62nd St. Miami FL

REACH OUT TO THE OMBUDSMAN

The position of Ombudsman for Graduate Medical Education was created to promote a positive climate for residency and fellowship education by providing an independent, impartial, informal, and confidential resource for residents, fellows, and faculty with training-related concerns. You can confidentially call Dr. Sultan S. Ahmed at 786-253-8741 as well as email him at [email protected] . All anonymous concerns and complaints can also be addressed through correspondence at the following e-mail: [email protected] .

Ombudsman Policy

JOIN THE TEAM

This fellowship opportunity is for post-grad and under-grad applicants to develop hands-on research project development and implementation. The term of this fellowship shall be for (3) Months , (6) Months , or (1) Year .

Essential Requirements:

- Must have interpersonal skills needed to develop relationships with clinical departments, international research volunteers, and research liaisons in the Larkin Health System.

- Must be familiar with basics of research and methods application to work with reliable clinical evidence and data, having previous research collaborations that was resulted in publications would be preferred.

- In-person work at DRAA office at least three days a week is preferred.

What You Will Do:

- Participate in DRAA activities as a team member.

- Complete Citi Certificate.

- Complete the Research Training Lab and receive a “Certificate of Completion”.

- Complete and publish a Clinical Case Report.

- Work directly with residents and fellows to complete required research work, such as manuscripts, and quality improvement projects.

- Participate in the development of the Research Department newsletter and Research Symposium.

- Complete a presentation at a continuing medical education conference.

For Application and Requirements click here

Larkin team 11.

Sponsored by Larkin Community Hospital Research Services South Miami, Florida

TEAM 11 OVERVIEW

As background, Team 11 was originally formed during the COVID pandemic and provided invaluable research opportunities during these unprecedented times when sharing of information was critical. As a result of the purpose and connection, the members wanted to stay together and formed the Global Research Collaboration Network.

Recognizing the value of the program, Global Research Collaboration Network, also known as Team 11, Larkin Community Hospital sponsors the program and has integrated it into the Department of Research and Academic Affairs. The platform is open for everyone to bring any research and global health-related issues upfront to make a difference in the world and is free of cost. Team 11 creates opportunities to carry out research projects at both the local and international levels. From its inception, we have had more than 1400 plus researchers worldwide, including medical students, medical graduates, residents, and fellows with multiple successful publications who represent over 100 countries from every continent.

Department of Research & Academic Affairs

7000 SW 62 nd Ave | Suite #601 | Miami, FL 33143

Phone: 305-284-7567 | Email: [email protected]

Most Visited

- AEGD Accredited Program

Let's Get Connected

- Open access

- Published: 19 June 2020

Development and maintenance of a medical education research registry

- Jeffrey A. Wilhite ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-4096-8473 1 ,

- Lisa Altshuler 1 ,

- Sondra Zabar 1 ,

- Colleen Gillespie 1 , 2 &

- Adina Kalet 1 , 3

BMC Medical Education volume 20 , Article number: 199 ( 2020 ) Cite this article

6524 Accesses

7 Citations

1 Altmetric

Metrics details

Medical Education research suffers from several methodological limitations including too many single institution, small sample-sized studies, limited access to quality data, and insufficient institutional support. Increasing calls for medical education outcome data and quality improvement research have highlighted a critical need for uniformly clean and easily accessible data. Research registries may fill this gap. In 2006, the Research on Medical Education Outcomes (ROMEO) unit of the Program for Medical Innovations and Research (PrMEIR) at New York University’s (NYU) Robert I. Grossman School of Medicine established the Database for Research on Academic Medicine (DREAM). DREAM is a database of routinely collected, de-identified undergraduate (UME, medical school leading up to the Medical Doctor degree) and graduate medical education (GME, residency also known as post graduate education leading to eligibility for specialty board certification) outcomes data available, through application, to researchers. Learners are added to our database through annual consent sessions conducted at the start of educational training. Based on experience, we describe our methods in creating and maintaining DREAM to serve as a guide for institutions looking to build a new or scale up their medical education registry.

At present, our UME and GME registries have consent rates of 90% ( n = 1438/1598) and 76% ( n = 1988/2627), respectively, with a combined rate of 81% ( n = 3426/4225). 7% ( n = 250/3426) of these learners completed both medical school and residency at our institution. DREAM has yielded a total of 61 individual studies conducted by medical education researchers and a total of 45 academic journal publications.

We have built a community of practice through the building of DREAM and hope, by persisting in this work the full potential of this tool and the community will be realized. While researchers with access to the registry have focused primarily on curricular/ program evaluation, learner competency assessment, and measure validation, we hope to expand the output of the registry to include patient outcomes by linking learner educational and clinical performance across the UME-GME continuum and into independent practice. Future publications will reflect our efforts in reaching this goal and will highlight the long-term impact of our collaborative work.

Peer Review reports

Medical education research (MER) should and could improve the health of the public by informing policy and practice but it suffers from many methodological limitations including small sample sizes, cross sectional designs, and lack of attention to important context variables. There are increasing calls for medical education research, a poorly funded field, to go beyond the proximate outcomes of training to study more distal clinical outcomes using “big data” strategies [ 1 , 2 ]. And yet, even within the same institution, data is collected using different systems and a wide range of formats, without a shared ontology or structured language and therefore is not organized to enable longitudinal tracking of learners, learning, or linking with outcomes.

While medical trainees must be afforded the same ethical and legal protections as any research subjects and U.S. federal regulations allow the use of educational data collected in the routine conduct of a required curriculum for research without written consent from learners, medical school research ethics review boards are not consistent in their approach to trainees as study subjects, complicating the ethical conduct of this type of research [ 3 ]. Establishing research registries can help overcome some of these barriers and facilitate higher impact, ethically rigorous programs of medical education research [ 4 ].

Research registries compile and maintain multiple-source, standardized information on potential study participants longitudinally for many purposes [ 5 ]. The National Leprosy Registry in Norway established in 1856, was the earliest disease specific registry, and the number of disease specific registries has increased steadily since [ 6 ]. More recently, research registries have focused on data integrity and quality improvement, following in the footprints of the Framingham Heart Study-style that began in 1970 [ 5 , 7 ]. In 2006, the Research on Education Outcomes (ROMEO) unit of the Program for Medical Innovations and Research (PrMEIR) at New York University’s (NYU) School of Medicine established the Database for Research on Academic Medicine (DREAM) with funding from the Bureau of Health Professions (BHPr) of the department of Human Resource Services Administration (HRSA # D54HP05446). Borrowing from the constructs underlying disease registries, the goal of DREAM is to enable ethical, longitudinal study of outcomes in medical education through the collection of routine trainee and educational context data [ 8 ]. DREAM, a potential database assembled as needed to ask and answer specific research questions, is structured as two research registries - one for Medical Students (established in 2008, with 1438 current individuals enrolled) and the second, a Graduate Medical Education Registry (established 2006, with 1988 current individuals enrolled), for trainees in the twenty participating residency and fellowship programs in our institution.

With approval from NYU’s Institutional Review Board (IRB) for our medical student and resident/fellow registries, we have been collecting written informed consent from medical trainees (students, residents, and fellows) using highly structured, transparent procedures. We request permission to compile data collected as a routine, required part of the trainee’s education for use in medical education research. Consenting subjects are informed both verbally and in writing that only data that has been de-identified by DREAM’s Honest Broker- a specific individual is responsible for serving as the data steward for the registries and who has absolutely no involvement in the selection, recruitment, employment, evaluation or education of the potential subjects- will be made available for the purposes of research. The consenting process is conducted by core members of the research team serving as Honest Brokers to ensure that the students’ and residents’ decision to consent is private and will not have repercussions (perceived or actual) for their standing in medical school.

DREAM is a collection of routinely gathered educational data spanning the undergraduate medical education (UME, medical school leading up to the Medical Doctor degree)-graduate medical education (GME, residency training also known as post graduate education leading to eligibility for specialty board certification) continuum. Available data at the UME level includes admissions data (e.g., Medical College Admission Test (MCAT) scores, Bachelor’s Degree Grade Point Average (GPA) and field of study (also referred to as major), medical school admissions multiple-mini interview scores), academic performance data (e.g., medical knowledge exam scores, clinical clerkship grades, clinical and workplace-based assessments), performance-based assessments (e.g., Objective Structured Clinical Examinations (OSCEs) and simulations), national licensing exams (Specialty Shelf, Step 1 and Step 2 Exams), and assessments of professional development. Available data at the GME level depends on the participating residency program but generally includes admissions data (medical school, Step 1 and Step 2 Clinical Knowledge (CK) exam scores), attitude and clinical experience/training surveys, milestone assessments, performance-based assessments (OSCEs and simulations), national exams (specialty certification board scores) and clinical assessments (e.g., workplace-based assessments, clinical and procedural skill assessments, and Unannounced Standardized Patient visits). We are currently engaged in several initiatives to incorporate clinical process and outcome data, at least partly attributable to residents, including primary care panel process and outcome variables, laboratory test ordering, and relevant practice quality metrics. As part of the GME Registry, we ask permission to join UME and GME data of learners who graduated from both levels at NYU School of Medicine, and currently maintain a database of 250 continuum learners.

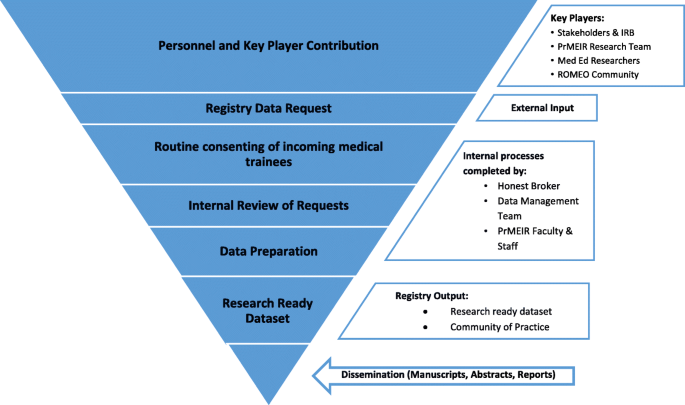

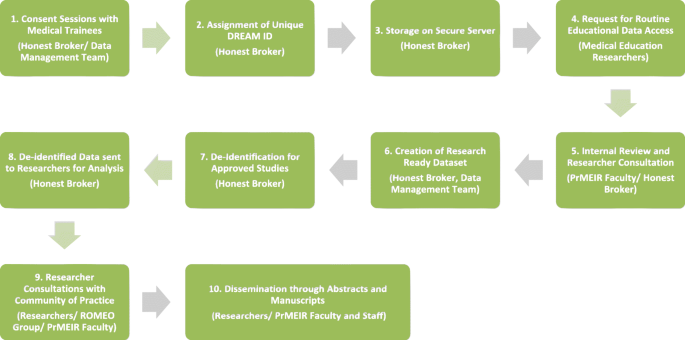

As far as we know the DREAM registries are the longest standing comprehensive medical education registries globally. To date 61 studies have been approved that utilize DREAM data (Table 1 ). Of these studies, there have been 45 publications, answering research questions focused on evaluation of trainings or curriculum, assessment of learner core competencies, and/ or validation of measures (Table 1 , Table 2 ). Routine Registry processes and flow have developed longitudinally through continual internal review and improvement (Fig. 1 , Fig. 2 ). Based on this accumulated experience and scholarly productivity, we propose 3 overarching principles and related practical advice to the larger medical education community on how to develop, implement, maintain and maximize the productivity of a MER registry. While our registries, and the data privacy issue examples provided are specific to the United States context, we suspect that the underlying goals, objectives, principles and guidance provided can be applied in general to the international MER community.

Registry Component Funnel

The Research Registry Roadmap (Responsible Party)

Principle 1: ensure the MER registry is addressing an important research mission

Invite broad input from stakeholders.

Assembling a broadly representative team of key stakeholders early in the project ensures long-term buy-in and maximizes resource support and registry productivity [ 9 ]. During initial planning phases, our discussions with community members, including medical education researchers, trainees, information technology (IT) experts, and course, clerkship and residency program directors honed registry objectives and built a case for a medical education research registry at the School of Medicine. A major objective of the registry, developed in collaboration with stakeholders, is to provide clean, easily accessible, de-identified data to the medical education community at NYU while maintaining strict confidentiality and data security. These types of data sets are exceedingly rare in medical education compared to other fields [ 10 , 11 ].

Stakeholder relationships continue to deepen because projects using DREAM data are regularly discussed at weekly, multi-disciplinary sessions where work in progress is shared and collaborations are nurtured. In addition, our review and approval processes include consultations and advising on available data resources, research design and methods, analytic approaches and opportunities for collaboration and therefore there is a great deal of informal MER faculty development that has helped build and sustain a community of Medical Education Researchers (Fig. 2 ).

Identify the scope and purpose of the registry

It is critical to define the scope and purpose of the MER registry [ 5 ]. Given our funding and particular areas of interest, the long term goal of DREAM is to establish the evidence base to guide medical education policy, innovation and practice by directly linking medical education with care quality and safety outcomes for patients. Our registries incorporate selective demographic and descriptive data about learners (e.g. Admissions), all routinely collected assessment and performance data, and selected education-focused survey data. For residents and fellows, we collect de-identified patient data directly attributable to those clinicians (e.g. ambulatory care-based patient panel data), and research utilizing this data is in progress [ 8 ].

Our registry was developed in close collaboration with NYU’s Human Subjects Institutional Review Board (IRB), the Office of Medical Education responsible for running the medical school, and individual residency and fellowship program directors [ 8 ]. Carefully articulating the purpose of a medical education registry helps to maximize stake-holder involvement and buy-in (e.g. trainees, faculty, administrators, patients, the community, the IRB), and to avoid potential misunderstandings of the registry process [ 12 ]. While building the argument for the need for the registry, creators should identify, become conversant with and address critical issues relevant to implementation including the privacy rights and concerns of trainees and legal concerns of the educational and training programs. In the U.S. this means being familiar with both the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) and The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA) federal laws addressing relevant privacy rights. Data for the registry is maintained by institutional entities and housed on highly secure Medical Center Information Technology (MCIT) servers. The DREAM registries protocols describe how researchers can obtain research-ready curated sets of data (fully de-identified data for only those learners that have provided consent).

Ultimately, the DREAM registries not only serve to advance medical education research globally, they also have contributed substantially to educational scholarship locally, supported promotion and career advancement for our education faculty, and helped faculty and education leaderships answer important – and almost always generalizable – questions about our local curriculum.

Establish a vision and set goals related to future data needs

Registry creators should remain aspirational and regularly brainstorm new research questions and protocols. Our initial plans, which included a focus on collecting performance-based assessment data (e.g. mostly from OSCEs), has grown to include additional assessment data (e.g. knowledge tests, peer assessments, mid-clerkship formative feedback). We also document the nature and timing of significant admissions and curriculum changes. Through regular registry data requests, the PrMEIR team has identified and addressed barriers to filling these requests. These barriers include technical issues such as a variety of data naming, storage, format and complexity concerns, as well as differing views on data use from course and curriculum leadership, registrar, human resources and clinical administrators despite consent from trainees (e.g. “who’s data is it?”). With increasing awareness of the registry and clarification of its purpose we are seeing an increase in the number and complexity of data requests. This has pushed us to continuously improve our communication with stakeholders, clarify our written materials, and enhance our capacity for data wrangling and management [ 13 ]. For instance, we have identified a goal of creating and implementing a standardized education research data warehouse with complete sets of data by student cohort [ 8 , 11 ]. Ideally this warehouse, or mart, will become a one-stop-shop for commonly requested data elements [ 8 ] that would permit aggregate data queries for planning studies and extraction of de-identified data sets for research. The Honest Broker, in more of a Data Steward role (see Principle 2 below) would help maintain the warehouse and routinely adjust its contents, structure, and data definitions to meet demands of an enlarging MER community. In our case, because financial support for DREAM staff has been provided through a combination of research and data infrastructure grants updating to a more robust and comprehensive data architecture is not yet possible. We are optimistic that as institutional data/ information technology resources become steadily more sophisticated more support will become available.

Principle 2: utilize best practice policies and procedures in establishing a MER

Assign a honest broker.

A registry should be managed by a data steward, or an individual positioned as the Honest Broker of research data. In clinical research, Honest Brokers are HIPAA compliant data preparers with a detailed understanding of the role of privacy, confidentiality and data security as regulated by legal requirement and sound moral judgement [ 14 ]. A steward should be capable of carrying out routine data management practices and able to maintain IRB and collaborator communication [ 14 ]. Ideally, Honest Brokers serve as a neutral intermediary between researchers and research participants and in the context of medical education, are responsible for safeguarding a participant’s protected education and training data [ 15 , 16 ]

PrMEIR’s Honest Broker is usually an individual with master’s level education and training specific to adhering to the rules of medical trainee privacy protection. The Broker conducts informed consent procedures with potential participants, prepares clean, de-identified data, communicates with interested collaborators, maintains a relationship with the IRB, is present during all registry related discussions, disseminates appropriate pieces of information to stakeholders, and most importantly, holds, privately and securely, the information on trainees’ decision to consent. Salary support for this function (e.g. calculated as % of a full-time equivalent (FTE)) is provided by a combination of external grants and institutional operating budget.

Establish appropriate funding channels and designate faculty and staff time

Creation of the DREAM registries was funded primarily through three successive Academic Administrative Unit grants from the US Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) running from 2011 to 2017. The aim of these grants was, among other things, to build the evidence base for medical education by supporting the data infrastructure necessary for linking educational efforts to patient outcomes in primary care. During the initial days of the registry, several core faculty members spent about a year designing the UME and GME registries and working with the NYU Robert I. Grossman School of Medicine’s IRB to finalize the protocol, consent materials and standard operating procedures. During this period, a small portion of funding was used to obtain the input of a data scientist, with the remainder going toward salary support of PrMEIR staff and faculty. Data storage was, and remains supported through NYU’s MCIT. Since then, grant funding has gone directly to PrMEIR faculty and staff (Honest Broker, Data Management Team) support in the realms of consenting, data cleaning, and upkeep of the registry.

Maintaining the two registries involves annual IRB continuation applications, consenting new learners each year, logging those consents, processing requests to participate in the registry, and overseeing data management. PrMEIR’s Honest Broker (author JW) spends approximately .40 FTE on registry upkeep. Data management, including data cleaning, rationalization (variable labeling, building and maintaining data dictionaries), merging/linking of data sets, and secure data storage, requires the greatest share of resources and currently includes .50 FTE of a Data Manager and .25 FTE of a Data Analyst. When grant-funded studies use core data from the Registries, small amounts of funding have been allocated to supporting Registry Data Management. The Principal Investigator (PI), or lead PrMEIR faculty for each Registry’s IRB protocol (authors CG and SZ), ensures that protocol is followed and participates as part of a small advisory committee that reviews and approves Registry requests, advises on data management practices, and makes use of the data for education research locally. This represents an estimated .05 FTE effort for each of the PIs and for each of the three advisory committee faculty members. A PrMEIR Program Administrator provides supervision to the Honest Broker and Data Management Team (.10 FTE). Therefore, the full team represents about 1.5 total FTE annually. Upkeep of the registry has since been supported in small ways through philanthropy-based funds and portions of other grants from external sources including AHRQ and foundation funding. There was little buy-in from the institution during early development phases, but this has shifted due to the meaningful output of research from those who utilize registry data.

Create rigorous, regulatory-compliant consent materials and processes

IRB approved consent forms (stamped with the approval date) describe the project, anticipated benefits and potential risks as well as processes for consenting, withdrawal of consent and reporting of coercion and breaches of privacy [ 17 ]. The Honest Broker (or delegated research team member) obtains trainee consents by attending new medical trainee program orientations to conduct a brief (< 30 min) information session. He or she briefly describes the project, allows time for trainees to read the consent form, answers questions, and collects signed, written consents from incoming learners. Trainees place their consent forms, whether they provided consent or not, in an envelope and all are asked to return the envelope in order to preserve the privacy and confidentiality of their decision to consent. Beforehand, the Honest Broker coordinates attendance with departmental leadership, collects rosters of incoming students for registry record keeping and prepares materials (printed consent forms, rosters, and attendance tracking materials).

The names of all trainees who consent to a registry are entered into the secure database (REDCap) within 24 h of collection from learners [ 18 ]. Each consenting learner is assigned a unique DREAM Identification number (DREAM ID). The Honest Broker maintains this “cross walk” database connecting subject names and DREAM IDs which is kept on a secure, firewall-protected server to which only a very limited set of research team members have access (currently, n = 2). Signed consent forms are organized consecutively and kept in a locked file cabinet. No one but the Honest Broker and core research team has access to information on the consent status of any individual trainee. Institutional collaborators are then able to request, from the PrMEIR team, curated sets of this data for research studies [ 8 ]. Collaborators must meet strict guidelines for usage. Namely, their study cannot be experimental, must be for education evaluation, assessment, or improvement purposes, and must identify each individual (Table 4 ).

Approximately 90% of medical students (UME) and 76% of residents and fellows (GME) consent to the DREAM registries annually (Table 3 ). Registry personnel complete and maintain all required research staff training. At our institution this includes the Collaborative Institutional Training Initiative (CITI Program) training on biomedical and social/ behavioral research, and good clinical practice. The PrMEIR faculty must maintain Principal Investigator Development and Resources (PINDAR) training completion certificates. These are research ethics trainings that are required for faculty doing research in the United States and are certified by the US Health and Human Services, Office of Science and Research.

Store data in a protected location, with limited access

A high level of protection for this type of data is mandated by these regulations. Establishing data protection protocols that are in-line with appropriate regulatory authorities is essential. Storage of protected information on an appropriately secure server is crucial for privacy protection [ 19 , 20 ]. The MER registry includes educational data protected under The Family Educational Rights and Privacy Act of 1974 (FERPA) [ 21 , 22 , 23 , 24 ].

Develop a standardized processes for registry data requests

Registry leadership needs to establish a process for making decisions about requests for data. A simple, well designed data request form that assess the degree of fit to the goals and regulations of the registry serves as an efficient way to begin the approval process and also serves to communicate those goals and regulations to potentially interested researchers. The registry consent applies only to routinely collected educational information as part of the required curriculum. This can cause confusion since researchers are often seeking to evaluate the impact of a curricular intervention. We often need to clarify that an intervention that is not a routine part of the curriculum - not available to all learners - would not meet registry criteria. In the case of an experimental design where only some students have access to the intervention, investigators need to approach the IRB directly for review. Once it is established that a request is appropriate, there needs to be a transparent, documented decision-making process, and timely feedback given to requestors.

The DREAM data request process is standardized (Table 4 , Fig. 2 ). Interested collaborators speak with registry representatives informally to review the scope of covered data and approval requirements. They then complete a data request survey, which is housed in REDCap, an IRB approved data program that collects essential study information (Table 4 ) [ 18 ]. PrMEIR’s internal team (authors SZ, LA, CG, JW, AK) reviews and discusses each proposal, follows-up to request required additional information, and provides a final decision. A registry data request is often an iterative, conversation, consultation and negotiation between the researcher and registry leadership. During the approval process, registry officials and applicants discuss study design, assessment strategy, and research questions. As noted earlier, this process helps develop applicants as education researchers, helps share information and knowledge about data, and serves to build collaboration among education researchers and synergies in education research projects. The decision of all registry requests is recorded in a request log available for audit by the IRB.

Maintain transparency around data usage & research

There are many concerns around use of education data for research. Some believe that learners are becoming more reluctant to allow their educational data to be used for research [ 13 ]. In our experience, curricular leaders often argue that they have ownership over the data produced during the conduct of formal curriculum they direct. In the era of “big data”, the public has had reason to become increasingly concerned about data use and sharing happening without their knowledge or consent. Public surveys show large variation in trust over use of personal data. Concerns have heightened in the wake of recent privacy breaches on social media platforms and in workplace information systems [ 25 , 26 ]. Medical Education researchers along with partners in the research regulation community must consciously and constantly monitor the protection of rights of research subjects. Pragmatically, this means that data usage plans should be outlined in detail, both verbally and in writing, throughout the research process and researchers must plan to communicate timely results to collaborators and stakeholders.

DREAM documentation outlines data use terms during consenting periods and shares updates with the PrMEIR/ ROMEO community regularly through annual email reminders. Registry personnel provide documentation of the terms of DREAM data usage as part of research training workshops and master’s programs for our community. The registry adheres to FERPA mandates by seeking explicit, plain-language consent to use learner data and by maintaining a record of all uses of those data. This process routinely evolves with the changing needs of registry users and within the context of the global data community. We continue to uphold that each learner’s data belongs to them as individuals and therefore they must give explicit consent for the collection, pooling, and analysis of their data.

Engage in continuous quality improvement