Today's Paper | April 13, 2024

Non-fiction: translating 'feminism' in urdu.

I was extremely excited when I heard that a book on feminism and feminist studies has finally been published in Urdu. Since the last five years, the word ‘feminism’ has very much become part of the everyday conversation and dialogue in Pakistan. This is basically because of the much-discussed, much-talked-about and much-criticised event known as ‘Aurat March’, which was initiated by a group of feminists in Karachi in 2018.

However, when I held the book in my hands and read the title — Aurat, Justujoo Aur Nisai Andaaz-i-Fikr [Woman, Struggle and the Female Style of Thinking] — I was, to be honest, taken aback. Was the book going to be about feminism, or about femininity? How does the word ‘feminism’ translate into the Urdu language? Will the book be able to explain feminist ideology to the reader and how the two concepts and ideas differ?

Even though many women — especially young women — are coming towards feminist ideas, not many are clear about what feminism actually stands for. There is much false propaganda against feminism and this is reinforced by fundamentalist groups and certain elements of the media that see women’s liberation and emancipation as a threat.

There is not enough awareness about feminism in Pakistan; the little that people do know about it is very biased and seen from the lens of a patriarchal society, therefore it is very essential and creditable that a book on feminism in Urdu is now available. This makes this book very welcome and one must congratulate the publishers, the printer and the editor. Readers owe a great debt to the book’s publishers — the Centre of Excellence for Women’s Studies (CEWS) at the University of Karachi (UoK) and the Anjuman Tarraqqee-i-Niswan — and Karachi Studies Society, which has served as consultant. It is wonderful that they have deemed it fit to publish a book in Urdu on feminism.

From the point of view of the contents, the book is interesting. Nasreen Aslam Shah, head of the department at CEWS, has compiled 10 papers written by herself, her faculty and her former students. There is much to inform readers about the history of the women’s movement in these essays.

A compilation of essays on feminism in Urdu is a welcome development, but could have been better thought through

There is no doubt that critical assumptions, historical circumstances and ideologies generally have been hostile towards women’s movements and there are not enough works to read about women’s contribution towards the development of societies. Shah’s book is an attempt to make available for Urdu-language readers a group of works that together bring various thoughts and approaches to feminist ideology and create a narrative on patriarchy and its contested margins.

The debates, on what constitutes ‘women’s work’ and what are women’s roles, have had to change over the years. As feminists, we do need to question words such as “izzat” [honour] and “zyadti” [excess] when it is used for the English word ‘rape’. Detailed feminist scholarship will offer new interpretations, new words, new vocabulary, new narratives, new norms and practices.

These are the kind of questions that must be raised in books on feminism. The women’s texts in this book document the many-faceted and often-challenged arguments within the women’s movement as crucial to an understanding of the feminist movement and the resistances it encounters and engenders.

In the preface, written by Shah, we are informed that, in 1989, Women’s Studies Centres were set up in five public universities of Pakistan, in the cities of Karachi, Lahore, Islamabad, Quetta and Peshawar. The library of the CEWS at the UoK holds many books on women’s studies, but since almost all of these are in English, it became imperative that a book on feminism in Urdu should be considered. Thus, the present volume emerged.

During the reading of the preface, the Urdu word “hawala” [reference] occurs repeatedly and I was dismayed to find that it has been used at least 15 times in the three-and-half pages of the preface. It is certainly not a word of literary value, and the constant repetition smacks of poor proofreading.

March 8 is the International Women’s Day and it gets mentioned as a rallying point for activities on women’s issues, but its significance, history or background is not explained. Since the book has been written keeping students and academic scholarship in mind, one feels more consideration should have been given to explaining how and why this particular day is celebrated around the world.

The first paper is by Dr Seema Manzoor, assistant professor at CEWS, UoK, and titled ‘Nisai Tehreek Ki Taareef-o-Adabi Tajziya’ [History of the Women’s Movement and Literary Analysis]. She chooses to begin with what I consider a cliché couplet by Allama Muhammad Iqbal:

“Vajood-i-zan se hai tasveer-i-kainaat main rang Issi ke saaz se hai zindagi ka soaz-i-daroon”

I would roughly translate this into English as: The image that this world presents derives its colours from woman/ She is the lyre that imparts pathos and warmth to the human heart.

One can question how appropriate this couplet is to begin a book on feminism. One would argue that the concept of woman as decorative goes against the very basis of feminism. Surely, the attributes of womanhood are more than softness, sweetness and love. However, Manzoor does give references and quotes from early feminists such as Mary Wollstonecraft as well as contemporary feminists such as Judith Evans. She argues that feminism helps women develop self-confidence, assert their independence and end discrimination. She concludes that, for women to become self-reliant and independent, it is essential that all subjects need to be rectified and gender and class discrimination must end; only then can an equal society be formed.

Dua Rehma, lecturer at CEWS, writes on the different phases of the women’s movement internationally and the ‘four waves’ of feminism. It is an informative essay and gives the reader data and names of international feminists who struggled as suffragettes for the vote, Black women who fought against slavery, the equal rights movements, Simone de Beauvoir, Betty Friedan and Germaine Greer. There is also mention of the #MeToo movement.

Dr Shagufta Nasreen, assistant professor at CEWS, takes on a slightly more analytical approach as the title of her paper itself conveys — ‘Nisaiyat: Makaatib-i-Fikr’ [Feminism: Schools of Thought] — and describes the different approaches towards feminism as well as explaining the differing ideologies of liberal feminists, Marxist feminists and radical feminists.

An attempt to explain the difference between sex and gender and how to resolve this confusion is taken up in the essay by teaching associate Dr Shazia Sharafat. This is followed by assistant professor Dr Asma Manzoor’s paper on the history of the women’s movement in the Subcontinent. Other contributors include teaching associates Dr Shagufta Jahangir and Dr Rukhsana Siddiqui and assistant professor Dr Alia Ali. In the final essay, Shah concludes with the need and importance of feminism and for feminist research with a holistic approach.

A problematic aspect of the book is that it seems the papers have simply been compiled, rather than planned as a collection, and this leads to a lot of repetition of the same material or information, which is irksome.

I was also saddened to find that the Aurat March — a turning point and one of the most important landmarks for the women’s movement in Pakistan — is not mentioned in any of the papers, even though the book was published in May 2021, while the Aurat March began in Karachi in 2018. This event has shaken up the very structures of patriarchy in Pakistan and brought issues of the women’s movement into mainstream public debate, redefining sexual mores in a changing contemporary society.

In patriarchal ideology throughout the years, women have been depicted as stereotyped — they have not been accepted as researchers and it has mostly been men who have undertaken research studies. Male sexism has judged and decided women’s roles as researchers or writers. Therefore, a ‘feminist culture’ has not been allowed to develop. Tasks have to be assigned, themes located, areas of debate defined and feminist criticism and ideology has to be authoritatively established.

Once we have a better understanding of feminism, we can develop a theoretical and political critique of our patriarchal society, unpack the oppression of women and ensure their full citizenship in society.

Although there are far too many typing errors and proofreading faults running throughout the book — a sad situation, because one certainly expects a level of quality from a university publication — one hopes Aurat, Justujoo Aur Nisai Andaaz-i-Fikr will be the seed for further books on feminism in Urdu in the near future, so that feminist scholarship in Pakistan can develop further into an institution of humanistic discipline.

The reviewer is a performing artist and cultural activist. She tweets @tehrikeniswan

Aurat, Justujoo Aur Nisai Andaaz-i-Fikr Compiled and edited by Nasreen Aslam Shah Centre of Excellence for Women’s Studies, University of Karachi ISBN: 978-9699453113 252pp.

Published in Dawn, Books & Authors, November 28th, 2021

FICTION: WOMEN ON THE VERGE

FICTION: ROOTS AND BRANCHES

NON-FICTION: A WOMAN WITH GUTS

اسرائیلی وزیراعظم غزہ میں ‘غلطی’ کا ارتکاب کررہے ہیں، امریکی صدر کا غیر متوقع بیان

آج کل کے نوجوان عید کا پہلا دن سو کر کیوں گزارتے ہیں؟

عید کے موقع پر فلسطینیوں سے اظہار یکجہتی کیسے کیا جا سکتا ہے؟

Recap: Six Months Of Israel’s Siege Of Gaza

Garbage is Not Just Garbage But an Invitation to Diseases

Ismail Haniyeh Repeats Ceasefire Call After Sons Killed

What Mood Swings?

Overthinking? What Overthinking!

Explained: Palestine At United Nations

Why Did Mexico Suspend Ties With Ecuador?

TOP NEWS STORIES: “Gaza Is Not Gaza Anymore”

Dear visitor, the comments section is undergoing an overhaul and will return soon.

Latest Stories

AI providing new tools to threat actors for attacks, says security firm

Sania Mirza says sports taught her that bad days don’t last in life

Two soldiers martyred during intelligence-based operation in KP’s Buner district: ISPR

Sydney knife attacker shot dead after killing 6 in Bondi mall

Gunmen abduct and kill 9 passengers from Punjab after ID check on bus near Balochistan’s Noshki

Spain, Ireland and Norway ready to recognise Palestinian statehood

Inside cricket star Aliya Riaz and commentator Ali Younis’s grand wedding

K-Pop singer Park Bo-Ram dies at 30

Most popular.

Punjab police decry ‘fake propaganda’ after video of cops being assaulted in Bahawalnagar goes viral

Russia, Germany urge restraint as Iranian threat of strike on Israel puts Middle East on edge

Shahpurkandi Dam: India-Pakistan experts advocate cooperation for water security

Important issues remain to be solved as Pakistan seeks potential follow-up programme: IMF chief

OJ Simpson, American football star turned celebrity murder defendant, dead at 76

UN experts alarmed by lack of protection for minority girls from forced marriages, conversions

Cartoon: 10 April, 2024

Amid schools’ expansion, govt to declare education emergency

Chand raat brings up win-win situation for Karachi’s henna artists and their clients

Editorial: A re-evaluation of how security is conceptualised and implemented in Pakistan is long overdue

Why climate governance needs to be revisited

GB’s grievances must be addressed lest they spark extensive unrest

Feeding smiles: As Gaza starves, Palestinians rise to the occasion to feed thousands of hungry mouths

An endless wait for rights

Climate governance revisited

Roots of barbarism

His first ‘fudget’

Complicit in genocide

Security lapses

An eventful season, living rough.

Saudi investment

Charity for change, walton land allegations, gazans live on memories of past eid festivals as israeli offensive ruins special day.

"> img('logo-tagline', [ 'class'=>'full', 'alt'=>'Words Without Borders Logo' ]); ?> -->

- Get Started

- About WWB Campus

- Translationship: Examining the Creative Process Between Authors & Translators

- Ottaway Award

- In the News

- Submissions

Outdated Browser

For the best experience using our website, we recommend upgrading your browser to a newer version or switching to a supported browser.

More Information

A New Year for Everyone

“With the advent of the new year / Old desires come back to life / The soul, worshipper of the Imagination, retires into solitude” —Omar Khayyam

Today, the afternoon—today, the afternoon of the first of January, I opened the door of my house and stepped outside, intending to go to the cemetery, when in front of me, amid the bellowing of the bells of St. Andrews, I saw a very well-dressed man. His face was an ocean of limitless waves—spontaneous joy and unfettered wishes for the New Year.

It was when I spotted the delicate violet flower placed in his buttonhole that I knew. This person had taken all of life’s despair and all the failures of the world and had bid farewell to them and to the stale, old year, and was now returning from the thundering bells.

I continued to stare wretchedly at his cheerful face—a long, cold breath reminded me, yes, this was the new year of one with no anxieties.

Shortly afterward, I found myself in front of the tall and terrifying black gate with which our temporary lives have an eternal bond and which a person who chooses to forget would not want to see on the first day of the new year.

The gate that holds within it my dear companion—ah, that same dearest one with whom speaking all so briefly was my raison d’être—today, completely lost to the eternal silence, weighed down by heavy stones, hapless he lies. The flood of memories of days gone by created a restlessness in me. Grief stole my sense of time, so I stayed awhile, having conversations with those who have been torn from me forever—but—

But today was not my lucky day. It seemed each and every one of them was rapt in an all-consuming raga. It seemed to me that this earth full of emotion that had hidden within it thousands of poets, world-renowned and courageous warriors, famous critics, selfless doctors, robbers and highwaymen, was softly singing a song woven of their benevolent and base deeds alike. The ears of my being were not, however, keen enough to ascertain the true meaning of the song.

Projections of memories played on my mind, showing the faces of those who had been present in my life many a day and night, whom Fate had decided that the dark curtain of Death be drawn over, obscured from vision forever.

Just once, I longed to lay eyes on them, just once—this longing has weakened my heart, beating itself toward stillness and yet in becoming silent, still beating too. My whole being was restless to hear their voices just once, and thus desirous my being was sulking like a child crying and crying like a child sulking.

The time came for my spirit’s exertions to cease. I heard not a voice, nor saw a face. I remained transfixed by the sight of the weighty gravestones defeated by the forceful hands of time.

Against the wide open blue of the sky, a kind of large, hot sun specific to the Eastern climes, the sun of Asia, was glittering fiercely. On the sorrowful old stones, the petals of a yellow rose were withering.

The words of Longfellow came to mind:

Life is real! Life is earnest! And the grave is not its goal; Dust thou art, to dust returnest, Was not spoken of the soul. (“A Psalm of Life,” 1839)

I walked off that part of the land, so triggering, and left the graveyard. Yes, this was the new year for the inhabitants of the world of Spirits.

At the Farber’s roundabout I could only see motorcars, trams, taxis, and vehicles of different widths and girths coming and going, making their journeys. They were like the fish in the oceans, restlessly seeking their food with each crashing wave.

In their cars people were going to the Farber’s horse tracks. They were getting in and getting out of the cars, pushing and shoving each other, seeing heaping golden piles of wealth dancing like sails in the wind. A lust for wealth creation—the ears of their souls familiar only with the clinking of coin.

Some of them were returning from Farber’s grounds. Others headed there. The fortunate ones kept their bags close—Fate had decided that their once-empty bags would be made heavy. But there were others who wept into their bags, which were initially weighty before Fate decided to lighten them.

I stood to one side, lost in a rapture of my own. Completely silent. Yes, I appeared completely mad observing this activity of the human race for a while. So this is what the new year of those who worship this life looks like!

I was able to extricate myself from the rushing waves of the ocean of people and arrive safely at Hashkal-O-Langton. There I was disturbed by the sounds of the military bugles both harmonious and depressing. A cavalcade of black horses pulled a black hearse carrying the body of a hopeful young soldier toward the cemetery. Mourners in funereal garb walked solemnly alongside the hearse, speaking of religious matters. It appeared they were all patiently trying to understand the ways of the Divine. Who is this object of such great jealousy, forced on the first new day of the new year to seek out a new world? I inquire of the vast skies: What soul would want such a thing?

Yes, this is what the new year of a brave warrior looks like.

Farther on, in a dark, tight passageway flanked by the street in front of the Harrison Hotel, I saw a fakir affected by leprosy, wrapped in dust and dirt. I observed how hundreds of cars, fine women and men, went by him. Not one person felt moved. Not one person thought to hold the hand of this wretched human.

Engrossed in the new delights of the first evening of a new year—was it not possible to pause for a few breaths and contemplate this human life rendered helpless, undeserving of such a fate—the moment they did give him was to nurse their own revulsion and express their scorn—this cursed world, treacherous world—what if it was me—what if I was to go to a friend in the same state as the fakir and my friend refused to hold my hand, moved away from me—

This, then, is the new year for a leper.

I walked on, finding again the ocean of people with its breaking waves near the Rapan Buildings—I saw young men and women on this evening of the new year, dressed in frocks and shawls, expensive coats, garish neckties, full of good cheer and worldly wishes. I questioned the Creator. Is this world of Adam and Eve really, truly brimming with delights and wonder? And if so, then what a grand thing this is.

I continued my observations. Some of their faces were radiant like the moon, blush and white like roses and sugar. But I could see their cores were hardened like the ground and blackened as the darkness of night. I sensed there was no compassion for their fellow humans in anyone’s heart. They sat in the grandest shops on the most expensive chairs with their friends—friends of great stature and untold wealth whose teacups and finest bottles of alcohol they were taking advantage of.

This, then, was their new year.

Thackeray came to mind:

“Such people do live and thrive in this world . . . those who are disloyal and treacherous and of whom you can have no expectation of goodness. . . . Come friend, let’s go on the offensive with all our strength, against these people.”

Evening had fallen and I returned to my house. In my library, on the table, an oil lamp was lit in a sky-blue magic lantern, flickering like the life of an ailing person. My emotions were unreliable and the events of the day had left me disturbed and restless.

This evening, Keats’s “Ode to a Nightingale,” Milton’s Paradise Lost , and the philosophies of Aristotle alike filled me with ennui. Even the fine wine of Omar Khayyam was not compelling.

I moved away from the pile of books on the table. I felt repelled by these thick, fleshy stacks in which the waves of knowledge and application crashed—because there was nothing written in any of them that would teach humankind, hapless humankind, how to be compassionate. There were novels of romance and beauty, the latest innovations in the sciences, slender volumes of philosophy, all useless, meaningless—there was no prescription or way to make one person a true ally of another—

I dragged a chair over to the window and sat down. In the distance, behind the branches of the henna shrubs, the first sun of the new year was taking its last breath. I heard the spirit of Omar Khayyam speaking to me on the winds:

“The New Year brings memories of the past back to life and our spirit cannot help but fly toward those bygone days.”

This was my new year.

The translator acknowledges the vast contribution made to the Urdu language by the resource Rekhta. The manuscript Khalwat Ki Anjuman (The company of silence), one of the few copies available, is a rare text from 1936, digitized by Rekhta and published by Dar-al-Sha’at, Punjab, Lahore.

From Khalwat Ki Anjuman. By arrangement with the estate of Hijab Imtiaz. Translation © 2020 by Sascha Akhtar. All rights reserved.

Hijab Imtiaz

Hijab Imtiaz was born into a family passionate about…

Sascha Akhtar

Sascha Akhtar is a native Urdu speaker and an English-language…

Time-Travelers, Fisherwomen, and Sleuths: Arabic Young Adult Literature

Multi-multi-culti: writing between the lines, 12 translators recommend women in translation.

HUM BHI DARIYA HAIN HUMEIN APNA HUNAR MAALUUM HAI

Five prominent feminist writers in urdu.

In the latter half of twentieth century, the world was hit by a Feminist storm; and rightly so. The female voices rose to break free of the four-walls behind which they had always remained unheard in a strongly patriarchal society. We mention here some names and their works that championed the cause of Feminism in Urdu literature.

FEHMIDA RIAZ (1946-2018)

The author and activist who wrote extensively and strongly over gender inequality, men and women struggling against the imposed morality of the bourgeois class and class conflict. She strongly believed in freedom of expression. Her works express female sentiments without any reluctance or discomfort. She had to face several social challenges for using erotica and sensuality in ‘Badan Dareeda’, a collection of her verse. Her magazine ‘Awaaz’ was banned for projecting a revolutionary vision which brought her an exile of seven years. Fahmida Riaz authored several books like Pathar ki Zaban, Godaavari, Khatt-e Marmuz, Khana e Aab O Gil, Dhoop, Badan Darida, Karachi, Adhoora Aadmi etc.

Ek zan-e-KHana-ba-dosh tum ne dekhi hai kabhi ek zan-e-khana-ba-dosh jis ke kheme se pare raat ki taareki mein gursana bhediye ghurrate hain duur se aati hai jab us ki lahu ki ḳhushbu sansanati hain darindon ki hansi aur danton men kasak hoti hai ki karen us ka badan sad-para apne ḳheme men simaT kar aurat raat aankhon mein bita deti hai kabhi karti hai alaao raushan bhediye duur bhagane ke liye kabhi karti hai khayal tez nukila jo auzar kahin mil jaae to bana le hathiyaar us ke kheme mein bhala kya hoga toote phoote hue bartan do-chaar dil ke bahlane ko shayad ye khayal aate hain us ko maaloom hai shayad na sahar ho paae sote bachchon pe jamae nazren kaan aahat pe dhare baithi hai haan dhyaan us ka jo bat jaae kabhi gungunati hai koi bisra giit kisi banjare ka

PARVEEN SHAKIR (1952-1994)

Starting at a very early age, Parveen Shakir managed to establish herself in Urdu literature like almost no other female ghazal poet. In her poetry, love and feminism are the most prominent amongst the various subjects she wrote on. Maintaining the classical fervor of Urdu Ghazal, she was the first poet who started using ‘feminine syntax’ in her poetry. Her free verses/nazms are very sharp in targeting at the ills of society and bold in thrashing the patriarchal structure. While the classicism in her ghazals is a luminous display of her excellent craftsmanship, the thunderous quietude in her nazms is the roar of her identity as a woman. Let’s hear:

Nick-name tum mujh ko gudiya kahte ho theek hi kahte ho! khelne vaale sab hathon ko main gudiya hi lagti huun jo pahna do mujh pe sajega mera koi rang nahin jis bachche ke haath thama do meri kisi se jang nahin sochti jagti aanhken meri jab chaahe binaai le lo kuuk bharo aur baaten sun lo ya meri goyaai le lo maang bharo sindoor lagao pyaar karo aankhon men basaao aur phir jab dil bhar jaae to dil se uthaa ke taaq pe rakh do tum mujh ko gudiya kahte ho theek hi kahte ho!

Poet and fiction writer, Azra Abbas is one of the most prominent women poets writing in Urdu. She was born in Karachi and obtained a master’s degree in Urdu from Karachi University itself. She wrote a long, feminist, stream-of-consciousness prose poem- ‘Neend ki Masaafaten’ which was published in 1981. She is one of the contemporary champions of the gender-inequality cause apparent in the five published volumes of her poetry and a memoir.

Hath khol diye jaen mere haath khol diye jaaen to main is duniya ki divaaron ko apne khwaabon ki lakiron se siyah kar duun aur qahr ki baarish barsaaun aur is duniya ko apni hatheli par rakh kar masal duun mera daaman Khwabon ke andhere men phailaa hua hai mere Khwab phaansi par chadhaa diye gae mera bachcha mere pet se chiin liya gaya mera ghar qahr-khanon ke astabal ke liye khol diya gaya mujhe be-zin ghode par andhere maidanon men utaar diya gaya hai meri zanjir ka sira kis ke paas hai? qayamat ke shor se pahle main apni dhajjiyon ko samet luun apne bachchon ko aakhiri baar ghiza faraham kar duun aur zahr ka piyala pi luun meri zanjir khol di jaae is ka sira kis ke haath men hai?

KISHWAR NAHEED

Kishwar Naheed is widely acclaimed for her fierce and uncompromising poetic expression against extremism, violence and atrocities faced by women in the male-dominated society. In her compositions, she celebrates the universal human struggle for equality, justice and freedom. She is also a proponent of peace and advocates global political order. Her voice has gained in gravity and determination over the period of time.

Hum gunah-gaar aurate.n hain ye ham gunahgar aurten hain jo ahl-e-jubba ki tamkanat se na raub khaen na jaan bechen na sar jhukaaen na haath joden ye ham gunahgar aurten hain ki jin ke jismon ki fasl bechen jo log vo sarfaraz thahren niyabat-e-imtiyaz thahren vo davar-e-ahl-e-saz thahren ye ham gunahgar aurten hain ki sach ka parcham utha ke niklen to jhuuT se shahrahen ati mile hain har ek dahliz pe sazaon ki dastanen rakhi mile hain jo bol sakti thiin vo zabanen kaTi mile hain ye ham gunahgar aurten hain ki ab taaqub men raat bhi aae to ye aankhen nahin bujhengi ki ab jo deewar gir chuki hai use uthane ki zid na karna! ye ham gunahgar aurten hain jo ahl-e-jubba ki tamkanat se na raub khaaen na jaan bechen na sar jhukaaen na haath joden!

ISMAT CHUGHTAI (1915-1991)

Famously known as the ‘Great Dame’ of Urdu literature, Ismat Chughtai was an Indian Urdu novelist, short story writer and filmmaker. She wrote extensively, exploring the themes of female sexuality and femininity, and became one of the grandest names in Urdu prose. Many of her works including Lihaaf were banned in South Asia due to resistance by conservatives. Here is an extract from her short story ‘Lihaaf’ depicting the life of ‘ Begum Jaan’, a neglected wife in ‘feudal Indian society’.

Tags: Ghazal , Poets , Urdu

Enter your email address to follow this blog and receive notification of new posts.

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- February 2018

By Abbas Qamar

Essay on Women’s Rights in Urdu

Back to: Urdu Essays List 3

خواتین کے حقوق پر مضمون

- اللہ تعالی نے ہمیں ایسے کامل اور اکمل دین سے نوازا ہے جس میں زندگی گزارنے کے ہر شعبہ سے متعلق پوری رہنمائی اور ہدایت موجود ہے۔اگر ہم اللہ تعالی کے بتائے ہوئے احکامات پر چلیں جس طرح اللہ اور اللہ کے رسولﷺ نے بتایا ہے تو انسان کی دنیا بھی اچھی رہے گی اور آخرت میں بھی اسے کسی طرح کی دشواری کا سامنا نہیں کرنا پڑے گا۔

- سورہ نساء آیت نمبر 19 میں اللہ تعالی نے فرمایا ہے کہ اپنی بیویوں کے ساتھ اچھا سلوک کرو۔ آپ صلی اللہ علیہ وسلم فرماتے ہیں کہ تم میں سے بہترین انسان وہ ہے جو اپنے گھر والوں کے ساتھ حسن سلوک کرے اور میں بھی اپنے گھر والوں کے ساتھ بہترین سلوک کرنے والا ہوں۔

- حضور صلی اللہ علیہ وسلم کے اس دنیا میں آنے سے پہلے عورتوں کے ساتھ بہت زیادہ ظلم ہوتا تھا۔ جب بیٹیاں پیدا ہوتی تھیں تو انہیں زندہ دفنا دینے کا رواج تھا۔ لیکن جب حضور اس دنیا میں تشریف لائے تو اس رواج کو ختم کردیا اور عورتوں کو اسلام میں اعلی درجہ دیا۔ اور لوگوں کو بھی ان کے حقوق کے بارے میں سمجھایا کہ بیٹی اللہ کی دی ہوئی وہ نعمت ہے جو اللہ اسی کے گھر میں دیتا ہے جس کا گھر اللہ کو پسند آتا ہے۔

- حضور اکرم صلی اللہ علیہ وسلم فرماتے ہیں کہ جب اللہ کسی کے گھر میں بیٹے کو بھیجتا ہے تو اس بیٹے سے کہتا ہے کہ جاؤ اپنے ماں باپ کا سہارا بنو۔ لیکن اس کے برعکس جب اللہ ایک بیٹی کو بھیجتا ہے تو اس سے کہتا ہے کہ جاؤ تمہارے ماں باپ اور تمہارا سہارا میں خود بنوں گا۔ “سبحان اللہ” اگر اللہ خود کسی کا سہارا بن جائے اور اس کی ہر چیز اپنے ذمے لے لے تو پھر کس بات کی فکر ہے۔ یہ حقیقت ہے کہ بیٹی اپنے ساتھ اللہ کی رحمت لے کر آتی ہے اور بیٹیوں کی پرورش انسان کو جنت میں لے جائے گی۔

- اللہ پاک نے بیٹیوں کو ایسا رتبہ اور ایسا مرتبہ دیا ہے کہ جو شخص اپنی بیٹی کی پرورش دل سے کرے گا اور اس کی شادی میں خرچ کرے گا تو اس کو اللہ تعالی ایک حج کا ثواب دے گا۔ ایک بیٹی کی شادی پر ایک حج کا ثواب اور اسی طرح دو بیٹیاں ہیں تو دو حج کا ثواب ملے گا۔ ماشاء اللہ۔

- اللہ تبارک و تعالی نے عورتوں کا مقام اعلی درجہ پر رکھا ہے۔ لیکن آج کی اس دنیا میں انسان خواتین کو اہمیت نہیں دیتا اور ان کے حق کو ادا نہیں کرتا۔ پھر چاہے وہ ماں کا حق ہو٬ بیوی کا ہو یا پھر بہن کا ہو۔ انسان صرف اپنے فائدے کے بارے میں سوچ رہا ہے لیکن عورت کے حق کو مارنے والا آخرت میں اللہ تعالیٰ کو حساب دے گا۔

- باپ کے دنیا سے رخصت ہوتے ہی اس کی ساری اولادوں میں سے جو بیٹے ہیں وہ پوری طرح سے جائیداد کے مالک بن جاتے ہیں اور عورت کو وراثت سے محروم رکھتے ہیں۔ جب کہ اللہ تبارک وتعالی سورہ نساء میں صاف صاف فرما رہا ہے کہ :”تمہاری اولادوں میں بیٹوں کا حصہ دو مردوں کے برابر ہے۔” اسی طرح اللہ نے بیٹیوں کا بھی حصہ مقرر کر دیا۔ بیٹے کا حق زیادہ اس لیے رکھا کیونکہ اسے حق محر کے ساتھ ساتھ اور بھی ذمہ داریاں پوری کرنی ہوتی ہیں۔

- بخاری شریف میں آیا ہے کہ ایک شخص اپنی ماں کا فرمابردار اپنی کمزور ماں کو حج کروانے کے لیے یمن سے اپنے کندھے پر لے کر آیا اور اپنی ماں سے کہتا ہے کہ تجھے اس سے بہتر سواری نہیں مل سکتی تھی۔ یہ دیکھ کر حضرت عبداللہ بن عمر نے اس شخص کو بلایا اور پوچھا کہ تو یہ کیا کر رہا ہے؟ تو اس شخص نے کہا کہ میں اپنی بوڑھی ماں کو حج کرانے لایا ہوں۔ وہ اتنی کمزور ہے کہ کسی سواری پر نہیں بیٹھ سکتی۔ اس لیے میں اسے اپنے کندھے پر لے کر آیا ہوں۔ کیا میں نے اس کا حق ادا کر دیا؟ تو حضرت عبداللہ بن عمر رضی اللہ تعالیٰ عنہ نے فرمایا کہ جب تو پیدا ہوا اور تیری ماں کو جو اس وقت درد ہوا اس تکلیف کا تو نے ایک حصہ بھی نہیں ادا کیا۔

- ماں کے کردار میں تو خدا نے عورت کا مقام اور بھی زیادہ اونچا رکھا کہ بیٹا اپنی پوری زندگی بھی اسکی خدمت میں لگا دے تو بھی ماں کا حق ادا نہیں کر سکتا۔

- حضور صلی اللہ علیہ وسلم سے کسی شخص نے پوچھا کہ سب سے بہتر اخلاق کا حق دار سب سے پہلے کون ہے؟ حضور بولے تیری ماں۔ انہوں نے پوچھا کہ اس کے بعد؟ حضور نے کہا تیری ماں۔ اس نے تیسری بار پوچھا، اس کے بعدحضور نے پھر کہا تیری ماں ہے۔ اور اس کے بعد تیرا باپ ہے۔ گویا ماں کا درجہ اعلی مقام پر رکھا گیا ہے۔

- خاوند اور بیوی کے برابر کے حقوق ہیں۔ صرف ایک حق ہے جو مرد کا ہے وہ ہے طلاق دینے کا۔ وہ اس لئے ہے کیونکہ مرد عورت کو حق مہر ادا کرتا ہے۔ اس لیے طلاق کا حق بھی مرد کو ہی دیا گیا۔ اگر عورت کو یہ حق دے دیا جاتا تو وہ حق مہر لینے کے بعد خاوند سے طلاق لے لیتی اور اسی کو اپنا پیشہ بنا لیتی۔

- اسلام میں جو مرتبہ عورت کو دیا گیا ہے وہ شاید ہی کسی اور مذہب میں عورت کو دیا گیا ہو۔ اللہ نے عورت کو بہت ہی اونچا درجہ دیا ہے۔ اس لئے جو شخص اللہ سے محبت کرتا ہے وہ کبھی کسی عورت کو گری ہوئی نظروں سے نہیں دیکھے گا اور نہ ہی کسی بیٹی کو بوجھ سمجھے گا۔

- Issue 10: Borders/Boundaries

- Issue 9: Enduring Imperialisms

- Issue 8: Language & Politics

- Issue 7: Beyond Tremors & Terror

- Issue 6: Mobs and Movements

- Issue 5: Space

- Issue 4: Onwards Pakistan

- Issue 3: Solidarity Politics

- Issue 2: After the Floods

- Issue 1: Room for Debate

- Conversation: Queerness & The Post-Colony

- Conversation: Infrastructures & Politics

- Conversation: Difference & the State

- Invisible Cities

- Feministaniat

- Media Watch

- Butcher’s Block

سلو کا بلاگ

صوفی کا بلاگ

شمارہ ١٠: لکیریں

شمارہ ٩: ثابت قدم سامراجیت

شمارہ ۸: زبان و سیاست

شمارہ ٧: ماوارئے حادثات و دہشت

شمارہ ۶ : ہجوم اور تحریک

شمارہ ۵: فضا و مکان

شمارہ ۴: ۲۰۱۳پاکستانی انتخابات

- Purchase TQ

- Current Issue

Women in Urdu Literature

Issue 8 | شمارہ ۸

Summer Winds| Artist: Murad Khan Mumtaz

All of the stories that exist, in our knowledge, were written after the fall of the matriarchy. This is why tales found in the epic of Gilgamesh—or on scrolls of papyrus excavated in Egypt—are about men’s power, their sovereignty and the accomplishments of great princes. Meanwhile, women appear weak and submissive, unable to make decisions.

In these stories, while men are busy holding off enemies on the battle field, women stand by awaiting the outcome, perhaps in prison, or bickering with one another in the market. If it’s a love story, we can expect the man to be loyal while the woman is unfaithful.

Take, for instance, the first chapter of the Old Testament, “Creation,” in which we learn the story of Adam and Eve. In it, Eve is inferior to Adam, from the moment she is born from his rib. Adam’s complaint to God is the justification for Eve’s birth—he was unhappy in the solitude of Eden. In other words, Eve was made as an appendage to Adam.

Adam remained resilient against Satan’s temptation, whereas Eve not only fell but got Adam banished from heaven as well.

A cursory glance at world literature brings us to the Thousand and One Nights. The heroine, Sheharazad’s life is in King Shariyar’s hands. This king believes that it is his duty to murder his bride each night. For her part, Sheharezad uses her wit to invent a new but incomplete story each night, thus saving herself.

The stories that Sheharazad recounts in the Thousand and One Nights portray men wielding their power, while women use their cunning to overcome difficult patches. This is similar to the ideas about male and female gender roles found in Boccacio’s Decameron.

In our society, we can get an idea of male and female gender roles by considering two stories that most of us heard as children, from our mothers or maybe our grandmothers. One of these is the story of the Sparrow and his Wife, in which “the sparrow’s wife finds a grain of daal and the sparrow a grain of rice, and together they cook kichiri.” The female sparrow is punished by her husband, who drowns her in a well. The man’s authority is volatile.

Meanwhile, in another story, “The Pygmie and his Wife,” the king kidnaps the pygmie’s wife, challenging him in a fight to the death. For the sake of his honour and his sanctity, the pygmy doesn’t simply go to the king’s palace alone, but employs the power of all his community’s resources: from its insects to its river, the fire, and even the rains. After storming the kingdom, he reaches the palace, lays waste the king’s soldiers, and smashes the place to pieces.

These stories send children the signal that, in their seminary society, male and female roles are fixed, existing even in the world of birds. If a sparrow’s wife tells a lie, then he has the right to punish her by killing her. If a pygmy’s wife is kidnapped, then the pygmy, because he is a man, is responsible for her unquestionable purity, and so must not only personally attack the King’s palace, but must call his whole community to help him in the battle to bring back his wife.

If we want to discuss these issues in the context of modern Urdu literature, we begin in 1801, with Meer Aman’s Bhaag o Bahar. In 2002, Urdu literature was 200 years old. As we see these two centuries mirrored back at us in literature, it is clear that men remained dominant. Men make life decisions and women are compliant. Men satisfy themselves with foreign women and women silently endure the injustice, reflecting traditional gender roles in Urdu literature.

The Story of Amir Hamza is a notable deviation from this tradition. At 46 thousand pages, it is the longest story in Urdu literature or the world. The countless female characters in this story have made a new taste familiar in Urdu literature. These female characters make the kinds of decisions that men make. They fight wars and even kill men. In this tale, women have all kinds of authority. In the battlefield they race horses, and they control men with swords, arrows, magic and witchcraft. Men are their prisoners; they throw them on the backs of horses before making off with them. They gather to celebrate their triumphs with feasting and splendour, congratulating one another. In these pages, breathing men and women abdicate their gender roles.

In Urdu literature, The Story of Amir Hamaz retains an exceptional status. But it is also true that in the second half of the nineteenth century, the British Raj’s newly expanded administration, which preceded the introduction of Western education and of modern industry, had a huge influence.

This inspired Urdu writers to discuss women’s rights, education, and freedom from the veil. These writers rejected men and women’s prescribed gender roles.

Among these, two important names are Sajjad Haider Yaldram and Mirza Azeem Baig Chughtai. Sajjad Haider Yaldram was among the first Urdu writers whose goal was to bring equality to women. In his stories, women defy their prescribed gender roles and are seen shirking the veil, receiving modern education and participating in mixed gatherings. Perhaps he got these ideas from his wife, Nazar Sajjad Haider, who wrote novels with female characters who rejected their prescribed gender roles.

When it comes to rebelling against gender expectations, no name is more important than Azeem Baig Chughtai’s. He personified women in a new way. His women lived in a beautiful world based on gender equality, who were educated and had brilliant minds, who took in air side by side with men, as companions.

In his famous novel, Shahazoori, there is a female who is illiterate and lower class, but who is nonetheless fully conscious of her rights. The heroine of Shazhazoori defies ancestry, class status and male dominance with such vehemence that there is none like her in Urdu literature. Such characters—who disrupt the traditions of male and female gender roles and turn them on their heads—had never been created before, and this too from a man’s pen.

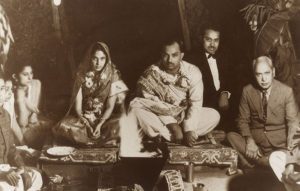

At the end of the nineteenth century, Rashida Alnasa’s novel showed men and women with slightly distorted gender roles, but from the beginning of the twentieth century, Saghara Humayun Mirza, Nazar Sajjad Haider, Walda Afzal Ali, Mrs. Hijaab Imtiaz Ali, and many other female writers came to the fore. Many of them defied prescribed gender roles in their creations and shocked readers.

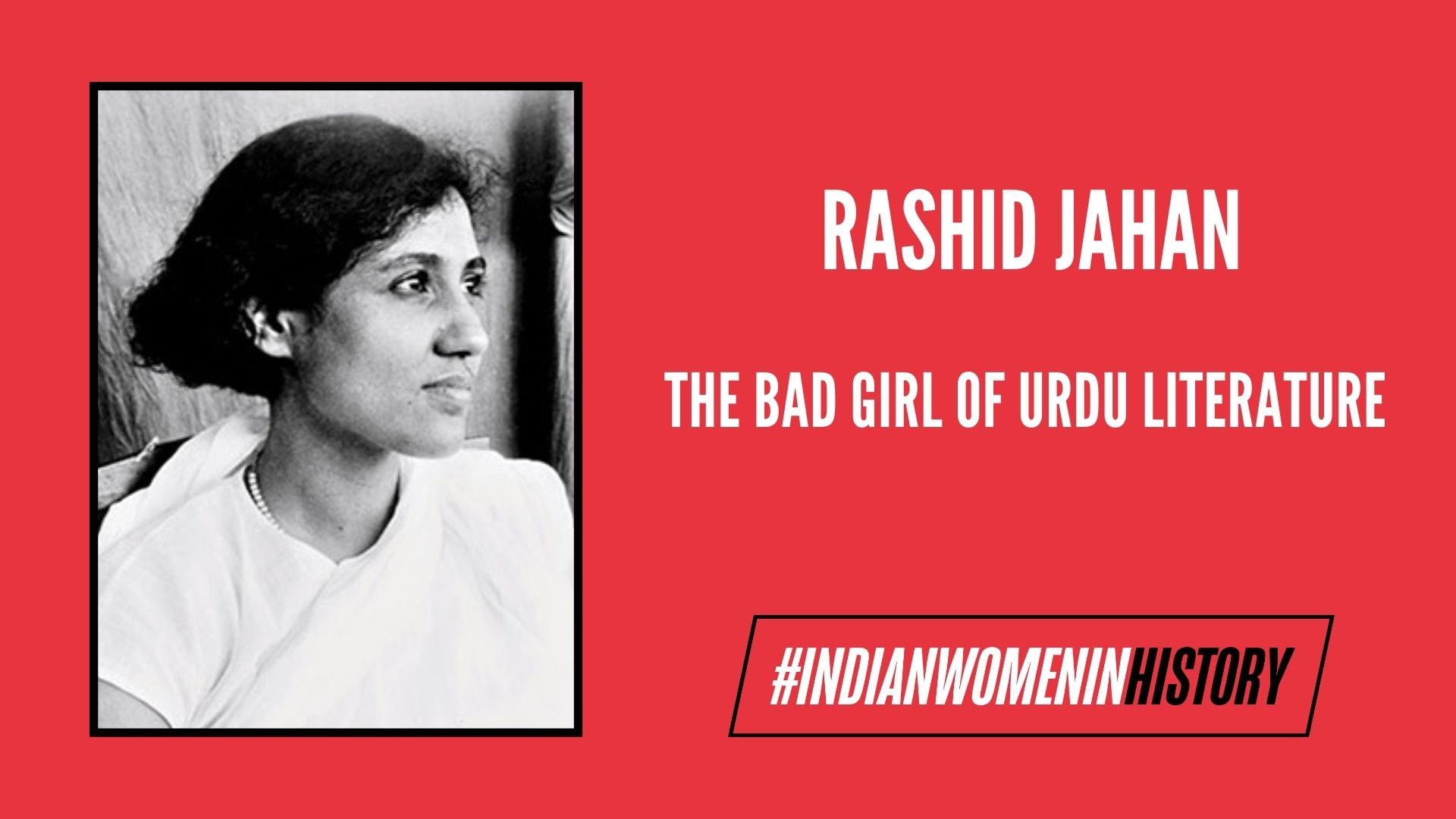

With publication of Angare (embers) began the Urdu Progressive Writers movement, which gave us the work of Premchand, Krishan Chander, Doctor Rasheed Jahaan, Ismat Chughtai, Azeez Ahmed Baidi, Manto, Qara Alaiin Haider, Ahmed Nadeem Qasmi, Khadija Mastoor, Hajrah Maroor, Shaukat Siddiqui and other very important names.

While these writers portrayed traditional gender roles, they would also write rebellious male and female characters who deviated somehow or another from norms and traditions.

Among these writers, Sadaat Hasan Manto and Ismat Chughtai’s names are key. Both wrote stories that defied gender roles exposing society’s hypocrisy.

Ismat Chughtai’s stories, on one hand, include female characters who are financially independent, such as those in her novels Crooked Line and Innocence. These women move within the labyrinth of the film world, where old gender traditions are forgotten. Jeelani Bano and Wajida Tabussum also tore down gender roles in their work.

If Quratulain Hyder included some traditional gender roles in her stories, she also wrote modern, educated and independent women, like Sita Marchandaani in Sita Haran and Chumcha Ahmed in River of Fire, as well as the heroine of Autumn’s Voice. Rejecting tradition, she determines her own new gender roles.

In the last fifty years, new names have come to the fore in Urdu literature. In the wake of India’s partition, hundreds of thousands were uprooted, murdered and massacred, impoverished and without livelihood.. Women were violated. Western civilization had space to invade, and in its wake came sexual aggression. In cities there was sectarian violence, political repression and stringent ideological and religious prejudices. All this gave Urdu writers a wide variety of topics, which they each took on in their own style.

There were both men and women among these writers. Many have written stories about men and women that reflect traditional gender roles, but some of the stories and novels have examples of men and women deviating partially or entirely from tradition.

Literature illustrates the temporal and physical realities of its context: it is not possible that society’s traditional gender roles would change and literature would go on as though nothing had happened. In Urdu literature, a clear change is occurring, reflecting the changing relationships between men and women in our society.

Zaheda Hina is an Urdu writer, columnist, essayist, short story writer, novelist and dramatist. She is the recipient of numerous literary prizes. In 2006, she was nominated for Pakistan’s highest award, the Presidential Award for Pride of Performance. She turned it down in protest against Pakistan’s military government.

Tags: issue 8 , urdu , urdu issue , women , women literature , zaheda hina

This entry was posted on Feb 2015 at 11:00 PM and is filed under Essays , Essays & Criticism , Gender , Issue 8: Language and Politics , main bar . You can follow any responses to this entry through the RSS 2.0 feed.

14 Responses to Women in Urdu Literature

JUST PUBLISHED! Read Zaheda Hina, one of the foremost Urdu writers today, on the transformation of female… http://t.co/VcJRpNmiav

Zaheda Hina on the changing and increasingly “deviant” women in Urdu lit! TQ translates leading Urdu writers! http://t.co/1qiCxHiNfW

RT @TanqeedOrg: Zaheda Hina on the changing and increasingly “deviant” women in Urdu lit! TQ translates leading Urdu writers! http://t.co/1…

Zaheda Hina on the changing and increasingly “deviant” roles of women in Urdu lit http://t.co/1qiCxHiNfW Translation by @write_noise

Women in Urdu Literature http://t.co/8bh9RHH71U

RT @TanqeedOrg: Zaheda Hina on the changing and increasingly “deviant” roles of women in Urdu lit http://t.co/1qiCxHiNfW Translation by @wr…

read Zahida Hina’s fantastic essay Women in Urdu Literature now in English! (the original Urdu is here:… http://t.co/fmJbub17Hb

Better find and read some of these writers! Women in Urdu Literature http://t.co/rahCWnBG78

#AuratJagi RT @TanqeedOrg: Zaheda Hina on the changing and increasingly “deviant” women in Urdu lit! http://t.co/EV9ZdwEqQn

RT @AwamiWorkers: #AuratJagi RT @TanqeedOrg: Zaheda Hina on the changing and increasingly “deviant” women in Urdu lit! http://t.co/EV9ZdwEq…

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

JavaScript seems to be disabled in your browser. You must have JavaScript enabled in your browser to utilize the functionality of this website.

- View Full Catalogue

- WHY PUBLISH WITH US

- SUBMIT A PROPOSAL

- THE PUBLISHING PROCESS

- PERMISSIONS AND COPYRIGHT

- SALES AND MARKETING

- PARTNERSHIPS

- Anthem EnviroExperts Review

- Anthem Companions to Sociology

- Anthem Impact

- Anthem Critical Introductions

- Anthem World Scientific

- Economic Ideas that Built America / Europe

- First Hill Books

- Humanities, Literature and Arts

Anthem Studies in South Asian Literature, Aesthetics and Culture

Gender, Sexuality and Feminism in Pakistani Urdu Writing

By Amina Yaqin

PDF, 294 Pages

- ISBN: 9781785277566

£25.00, $40.00

More Retailers >

Google Play

Barnes & Noble

EPUB, 294 Pages

ISBN: 9781785277573

Other Formats Available:

- Title: Gender, Sexuality and Feminism in Pakistani Urdu Writing

Your Information

- First Name Please enter a valid first name Last Name Please enter a valid last name

- Institution Please enter a valid Institution

- Email Address Please enter a valid email

Librarian Information

- Name Please enter a librarian name Library Please enter a library name

- Email Address Please enter a librarian email

About This Book

Author information, table of contents.

- Chapter Sales

Recently Viewed Titles

As the first study of its kind, this book offers a new understanding of progressive women’s poetry in Urdu and the legacy of postcolonial politics. It underlines Urdu’s linguistic hybridities, the context of the zenana , reform, and rekhti to illustrate how the modernising impulse under colonial rule impacted women as subjects in textual form. It argues that canonical texts for sharif women from Mirat-ul Arus to Umrao Jan Ada need to be looked at alongside women’s diaries and autobiographies so that we have an overall picture of gendered lives from imaginative fiction, memoirs and biographies.

In the late nineteenth century, ideas of the cosmopolitan and local were in conversation with the secular and sacred across different Indian literatures. Emerging poets from the zenana can be traced back to Zahida Khatun Sherwania from Aligarh and Haya Lakhnavi from Lucknow who had very unique trajectories as sharif women. With the rise of anti-colonial nationalism, the Indian women’s movement gathered force and those who had previously been confined to the private sphere took their place in public as speaking subjects. The influence of the Left, Marxist thought and resistance against colonial rule fired the Progressive Writers Movement in the 1930s. The pioneering writer and activist Rashid Jahan was at the helm of the movement mediating women’s voices through a scientific and rational lens. She was succeeded by Ismat Chughtai, who like her contemporary Saadat Hasan Manto courted controversy by writing openly about sexualities and class. With the onset of partition, as the progressive writers were split across two nations, they carried with them the vision of a secular borderless world. In Pakistan, Urdu became an ideological ground for state formation, and Urdu writers came under state surveillance in the Cold War era. The study picks up the story of progressive women poets in Pakistan to try and understand their response to emerging dominant narratives of nation, community and gender. How did national politics and an ideological Islamisation that was at odds with a secular separation of church and state affect their writing?

Despite the disintegration of the Progressive Writers Movement and the official closure of the Left in Pakistan, the author argues that an exceptional legacy can be found in the voices of distinctive women poets including Ada Jafri, Zehra Nigah, Sara Shagufta, Parvin Shakir, Fahmida Riaz and Kishwar Naheed. Their poems offer new metaphors and symbols borrowing from feminist thought and a hybrid Islamicate culture. Riaz and Naheed joined forces with the women’s movement in Pakistan in the 1980s and caused some discomfort amongst Urdu literary circles with their writing. Celebrated across both sides of the border, their poetry and politics is less well known than the verse of the progressive poet par excellence Faiz Ahmed Faiz or the hard hitting lyrics of Habib Jalib. The book demonstrates how they manipulate and appropriate a national language as mother tongue speakers to enunciate a middle ground between the sacred and secular. In doing so they offer a new aesthetic that is inspired by activism and influenced by feminist philosophy.

‘This is an important, incisive book with great depth and range, which provides new insights into equality, gender and self in the pioneering work of Pakistani women poets including Ada Jafri, Zehra Nigah, Fahmida Riaz, Kishwar Naheed and Sara Shagufta, also placing them within the history of Urdu women's poetry and progressive literature.’— Muneeza Shamsie, Independent scholar

Amina Yaqin is Associate Professor of World Literatures and Publishing at the University of Exeter. Prior to joining Exeter, she was Reader in Urdu and Postcolonial Studies at SOAS, University of London. Her research interests are interdisciplinary, engaging with contemporary contexts of Muslim life as well as the politics of culture in Pakistan. She is co-editor of the international journal Critical Pakistan Studies published by Cambridge University Press.

Acknowledgements; A Note on Transliteration; 1. Introduction: Poetry, Politics, Women; 2. Form, Education and Women: Rekhti, Reform and the Zenana; 3. Progressive Aspirations: Sexual Politics and Women’s Writing; 4. Fahmida Riaz: A Woman Impure; 5. Kishwar Naheed: Dreamer, Storyteller, Changemaker; Conclusion; Bibliography; Index.

https://newbooksnetwork.com/gender-sexuality-and-feminism-in-pakistani-urdu-writing

Stay Updated

Information

- For Authors >

- For Booksellers >

- For Librarians >

- For Reviewers >

- For Instructors >

- Rights and Permissions >

- Open Access >

Latest Tweets

Opt for a professional courier service instead of "Post By Air" if you are looking for quick and trackable delivery

- Search Terms

- Advanced Search

- Orders and Returns

- Privacy & Cookies

- Terms & Conditions

Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

FEMALE POETS’ SELF-REPRESENTATIONS IN URDU AUTOBIOGRAPHY: A COMPARISON OF ADA JAFRI AND KISHWAR NAHEED

This paper compares the feminist trends in Pakistan with reference to two eminent Pakistani Urdu women poets’ autobiographies: Jo Rahee So Bekhabari Rahee (What Lingered Was a Trance) by Ada Jafri and Buri Aurat Ki Katha (The Tale of a Bad Woman) by Kishwar Naheed. The two women have been participating in mushairas (mixed poetry-recitation gatherings) for several decades now, but their sharing of public space with men has had different social and psychological impacts on the two writers. Ada Jafri’s narrative is devoid of negativity, criticism, protest, or reference to sexuality. Kishwar Naheed focuses on these very things. Ada Jafri has no claim of being a feminist and is rather apologetic about her weak voice of protest against the denial of human status to women in Pakistan. Kishwar Naheed identifies her voice as an extension of the female voices all over the world and throughout history, blurring the boundaries of time and space in asserting her womanhood. However, some commonalities oblige us to re-examine their differences at a deeper level only to find out that in spite of the mental distance between them, at some level they are very similar. This also leads us to conjecture that the Pakistani feminism is probably a different kind of construct from what it can be perceived in the perspective of western feminism.

Related Papers

SMART M O V E S J O U R N A L IJELLH

The patriarchal structures of Pakistani society and its self-proclaimed identity as an Islamic state have necessarily and inevitably exercised a strong influence on Pakistani women poets. This paper examines how these poets negotiate with their religion and how this interface finds expression in their poetry. In order to engage with these issues, it would be pertinent to make a reference to Kishwar Naheed who, in her prose work Aurat Khwab aur Khaaq ke Darmiyan points out how traditional opinions concerning the role and position of women in Pakistani society have been conditioned by the injunctions of the Koran as interpreted and enforced by men:

Asma Mansoor

This paper explores the notions of " articulation, " " agency " and " embodiment " in Urdu poetry composed by Pakistani women. Although these terms have been taken from the First world feminist discourses, we aim to highlight how these three terms were not merely reflected in the contemporary poetry of Pakistani women, but rather were used to express their own modalities and associations as they countered the patriarchal system within which they were embedded. Our study does not simply apply these terms on selected poems by Kishwar Naheed (1940-), Fehmeeda Riaz (1946-) and Azra Abbas (1948-), but it also explores how these terms undergo a discursive diffraction as the Pakistani woman is no longer seen as a subaltern entity with a silenced subjectivity. We have taken on board the synonymic idea of writing as an agentive act of embodiment, as theorised by Luce Irigaray and Hélène Cixous. This is to show that while these terms were theorised by Western feminists, contemporary Pakistani women writers have, over the last few decades, been enacting these terms in ways which deny the stereotypical projection of the Third world woman in the Western gender discourses. For these women writers, writing enacts embodiment through articulation and thus agentively counters the objectifying gaze of the patriarchal order.

Baran Farooqi

Urdu literature prides itself on the presence of many significant female voices, both in fiction and poetry. I would like to investigate whether women’s writing in Urdu is merely one homogenous category, or are the women in the Urdu literary scene creative writers first and women writers afterwards? The case of Bilqees Zafirul Hasan would be an interesting one to explore, as she blossomed into a full-fledged writer only about the time when she was in her fifties, and had mothered six children. She gave up writing after marriage and devoted herself to the care of her husband and family. What were her possible concerns in turning to poetry? Bilqees Zafirul Hasan (b. 1938) has published two collections of poems in Urdu, Geela Eendhan (“Damp Fuel”), 1996, and Sholon Ke Darmiyan (“Amidst the Flames”) in 2004. A volume of short stories, Weerane Aabad Gharon Ke (“The Wildernesses of Flourishing Homes”), came out in 2008. She also writes plays. Very little of her work is available in translation, although her entire body of work deserves to be translated into English, and into Hindi and other Indian languages. This interview (conducted over several sessions in 2008) aims to present an introduction to the poetry of Bilqees Zafirul Hasan, who has not received the attention she deserves. It includes many excerpts from her beautiful poetry which may not necessarily dwell on a woman’s identity.

Huzaifa Pandit

The essay is an attempt to place the poetry of Kishwar Naheed within the modern feminist discourse by examining how it corresponds to various feminist theoretical constructs and displaces traditional phallocentric modes of writing and versification in her inimitable style of poetry. The essay will try to analyze the ideological moorings of the feminist poet and explore whether or not she borrows from the popular discourse of another transgressive school: The Progressive Writers Association. The objective is to read the selected poems closely and by an investigation of their syntactic and semantic transgressions observe the pragmatic shift in her poetry and analyze whether she is able to bring in a fresh perspective of the collective experience of the women in Post-Colonial Pakistan in specific and the sub continental women in general.

Orientalistica

Zayana Nasir

This essay aims at understanding the development and struggles of a ‘female voice’ within Urdu poetic tradition through the writings of women poets of the Nineteenth century in contrast to the women poets of the twentieth-century feminist movement. The women in traditional Urdu poetry have remained a silent cruel beloved, the image offered is that of a ‘feckless beloved, endowed with heavenly beauty, reigned: fair to face, doe-eyed, dark hair, tall and willowy, a woman who vacillated from indifference, shyness and modesty to wanton cruelty. The essay is an attempt to understand the level of autonomy of the female voice in the poems of women poets through the years. To portray the development of a feminine expression in Urdu poetry the paper will be ranging from the poems of tawaifs (courtesan) of the eighteenth century like Mah Laqa Chanda, their attempts to acquire a place within the patrilineal Urdu literary tradition; the rekhti tradition where men wrote poems in a female voice, ...

Muhammad Iqbal Chawla

This article attempts to explores, investigate and analyzes the postcolonial Urdu writings on the Pakistani women‟s participation in the socio-economic, religious and political arena. Urdu literature is spread all over the subcontinent and there are no borders in literature that can split it into two. This article would like to discuss literature mainly produced by Pakistani writers. However, while arguing that most literature has been written from a patriarchal viewpoint throughout the history, two main themes dominated the postcolonial literature firstly, role of women in the patriarchal society and other, the trauma of migration and its impact on the Muslim women in Pakistan. Islamic influence enforced purdah on Muslim women and purdahless women were regarded as infidel and shameless in literature. Nineteenth century Muslim writers advocated modern education for women not with the idea of emancipation but with a view to creating the modern wife, sister and mother. In this context...

Nukhbah Taj Langah

This paper applies textual analysis and ethnographic approach to explore the role of women within Siraiki cultural and literary domain. We contend that due to social taboos and patriarchal pressures, these women are experiencing suppression that results in their limited visibility within the mainstream literary circles. The lack of both, appreciation and mentorship for their creative outputs has resulted in the dearth of literature produced by Siraiki women writers. The objective of this study is to indicate how this oppression turns gender roles into enactment of power through creative writing. In order to substantiate our argument we rely on selected works by Iqbal Bano, Shabnam Awan and Mussarat Kalanchvi. In the process, we also attempt to theorize indigenous manifestation of feminist intent of these Siraiki writers as Trimti

Asian Journal of Multidisciplinary Studied

Arshad M Hashmi

Journal of Nusantara Studies (JONUS)

Zainab Basra

Background and Purpose: Fahmida Riaz was able to articulate precise feminist politics through her voice because she was audible to many women in the Pakistani context. The current study investigates how her writings about the female body were not merely a tool to celebrate or raise the sexual distance, but also influenced a political intervention and shifted the dominant patriarchal structures present in literary as well as other social and political levels. The purpose of the research is to shed light on how a specific poet's voice was able to reach a large audience of women and articulate explicitly feminist politics in Pakistan. Methodology: The Feminist Discourse Analysis (FCDA), another dimension of CDA, is employed in the analysis. The application of the FCDA model is adapted to examine how textual representations of gendered practices produce and sustain one gender power and dominance over the other. For the study, an operational method based on four models has been...

shazrah salam

RELATED PAPERS

Luis Carlos Martínez

BioEnergy Research

Venkatesh Mandari

ISPRS - International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences

Refleksi Pembelajaran Inovatif

andriyastuti suratman

Human Reproduction

Nicolas Gillain

Applied Physics Letters

F. Montaigne

cristina telles

Yen Revista

Nicolas Valenzuela Quintupil

João Vítor Torres

selen korad birkiye

Francesco Quatrini

CERN European Organization for Nuclear Research - Zenodo

Daniela Orani

José Mangalu Mobhe

European Scientific Journal ESJ

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET)

Revati Nalawade

Iranian Journal of Veterinary Medicine

Berkala penelitian agronomi

Samharinto Soedijo

Neuromarketing world

Pasindu Karunamuni

A LOOK AT DEVELOPMENT

Iracema Cusati

Coda a un centenario. Galdós, miradas y perspectivas.

Jurnal ekuivalensi

Muhammad andika Okky saputra

International Journal of Legal Medicine

Fukumi Furukawa

Annamarie de Villiers

Revista Brasileira de Otorrinolaringologia

Tânia Mary Cestari

Muhammad Asef Abrar

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

‘Gender, Region, Orientalist Bias Marginalised Hyderabad’s Women Urdu Writers’

Hyderabad has had a 150-year-long history of women writing prose in Urdu, a longer one of poetry and other oral and creative expressions. But we know very little of these writers and the flourishing literary scene where they carved a prominent space despite varied challenges (read more about this here and here ). Urdu writing emerged more prolifically in the second half of the 19th century with social reform, greater push for girls’ education and later on, the growth of the Progressive Writers Movement in 1936. Women writers such as Tayyaba Bilgrami, Sughra Humayun Mirza, Wajida Tabassum, Jahanbano Naqvi , Zeenath Sajida, Rafia Sultana, Azeezunnisa Habibi, Brij Rani, Jamalunnisa Baji, Oudh Rani Bawa among others were writers, poets, journalists, travellers and founders of literary magazines.

Bibi’s Room: Hyderabadi Women and Twentieth-Century Urdu Prose documents a literary tradition that has not got the recognition it richly deserves. The book profiles three prolific writers from Hyderabad. Zeenat Sajida (1924-2009) whose fascinating essays in the tanz-o-mizah (humour and satire) genre and khaake (pen-portraits) depicted gendered perspectives on the society and a glimpse into the everyday lives of women in Hyderabad; Najma Nikhat who wrote about feudalism, class struggle and patriarchy; and Jeelani Bano who, during the Jadeediyat (modernism) phase in Urdu literature in 1960s, wrote on contemporary themes of state and society. In an interview with Behanbox , its author Nazia Akhtar , Assistant Professor (Human Sciences Research Group) at the International Institute of Information Technology (IIIT), tells us why we need to not only recognise but also delve deeper into the Urdu writings of Hyderabad’s women writers.

Given how rich this literature is, why do most of us know so little about Hyderabad’s women writers and their work in Urdu?

There is triple marginalisation at work here which I also talk about in the book. The first is gender. The second is region: Urdu isn’t associated with the Deccan, which is ironic, because it was patronised and nourished here between the 15th and 17th centuries before it moved to the north, as a full-fledged literary language in its own right to be taken seriously by northern poets and audiences. There is a north Indian bias in Urdu literature as well as its translation.

There is a third problem. There is very little research on the princely states in India. This stems from the Orientalist scholarship, a major issue in the scholarship on South Asia in general, which wanted to project an image of British India as a progressive place. It was in the interests of the British to promote the idea that women fared better in British India, as opposed to the princely states, and where society and culture thrived. The princely states were presented as this Orientalist fantasy, a timeless and changeless world, a perception that was accepted at face value.

But scholars who are working on different princely states have pointed out that they were not immune to social and political events taking place elsewhere. It is only now after Siobhan Lambert Hurley’s writing on Bhopal or Razak Khan on Rampur, Kavita S Datla on Hyderabad, Janaki Nair on Mysore or Tarana Hussain Khan on Rampur that we have begun to think differently about society and culture in the princely states.

On translation, we know about North Indian writers but there again, we only know of north Indian women writers in Urdu, such as Ismat Chughtai, Rasheed Jahan, and Qurratulain Hyder, who have been translated into English. Now Khadija Mastur has joined these three or four names because she has been translated by Daisy Rockwell. People will also know about the most radical poets from north India and Pakistan like Fahmida Riaz and Kishwar Naheed. But apart from them, we don’t really know anyone else. I think there are different invisibilities and marginalisations.

We shouldn’t underestimate the role of English language translations in all this given the hegemony of the language. This is also something that is bitter-sweet, for it is the hegemony of English that is pushing our literary traditions and languages into the margins. And yet, for the women writers I document, I want to harness that power of English, in order to give them the same kind of visibility and new readership, who will appreciate their contributions and perspectives.

Why did you pick these particular writers for the book?

I chose these three writers because, first, I liked them. I could have written about Rafia Manzurul Ameen , who’s also a great novelist and she’s written for television and has a profile similar to that of Jeelani Bano. Between them, they have enough similarities to merit being put together. And at the same time, there is enough diversity and divergence between them to showcase a range of writings, concerns, themes, manipulation of genres. For instance, motherhood runs as a strong, continuous thread through all three women’s writings. But unlike Nikhat or Bano, Zeenath Sajida does not respond as enthusiastically to motherhood as the others. At heart she is a committed but somewhat troubled mother, mulling over the unfairness of motherwork and the status of mothers in the world in a manner that is more radical than that of the others. These similarities and differences offer a good first glimpse into a range of Hyderabadi women’s writings around the mid-20th century.

How did you develop an interest to research into the history of women’s writing and creative expressions of Hyderabad?

I had over a number of years accumulated texts written by these women writers. I’m not from Hyderabad, but I’ve been coming here since I was a child. Over the years Hyderabadis – knowing my interest in the literature and the history of this region – have been giving me books. Someone would call up and say, ‘Oh, I’ve heard that this scholar is releasing a book on Hyderabadi women’s writings.’ Or, ‘Have you met that writer who used to write pen-portraits and essays in the 1950s and 1960s?’ So I just began to collect books, stories and context. And over a period of time, I realised that there is a whole tradition of prose here that we don’t know anything about, which goes back 150 years, except for those whose works have been translated into English.This includes two novels by Jeelani Bano, Baarish-e-Sang and Aiwan-e-Ghazal. The translation of the first is not very readable but her first novel, Aiwan-e-Ghazal, was translated brilliantly by Urdu writer Zakia Mashhadi and yet, we don’t know about it because it wasn’t promoted very well by the publisher. The same goes for Mashhadi’s translations of Jeelani Bano’s short stories, which languish unsung. Wajida Tabassum , an intrepid writer who wrote on caste patriarchy, sexual violence in feudal homes had only two short stories translated until Reema Abbasi’s book of translations which came out in 2022.

How little is translated into English, and how little most of us today – irrespective of language or location – know about these women! There were women who were journalists and travellers, who journeyed through Asia and Europe, who worked energetically on social reform and questions of national and political unity, who developed the discourse of education for girls and women, and so on and so forth. I was just blown away by the fact that we knew so little about it all.

What were some of the surprising and interesting insights from your research into the rich landscape of women’s writing in Hyderabad?

I was struck by the sheer depth of some of the texts, which I wasn’t expecting. For instance, in 1946 essay Agar Allah Miyan Aurat Hote (If Allah Miyan were a woman) Zeenath Sajida asks fundamental questions about God, Prophet and the believer in a way that, I think, represents generations and centuries of voices of Muslim women. She expands on this theme in her other work as well. In another essay Hum Hain Toh Abhi Raah Mein Hai Sang-e-Giraan Aur , she takes Virginia Woolf’s idea from A Room of One’s Own and extends it. Why is it that you cannot have a woman Prophet? Why cannot women have full writing careers along with everything else that they have to do? These are such fundamental questions.

The other interesting insight is the range of themes that these writers dealt with despite having little formal education. Jeelani Bano and Najma Nikhat were schooled entirely at home, only Zeenat Sajida had formal education. Bano’s education was very eclectic and she was criticised by a few male progressive writers who, when she began writing about the labourers and tillers of Telangana, said ‘What does this girl who has lived in semi-pardah know about the realities of the working class?’ But women in the domestic space interact with the working class, with people from different classes, they work with them. Her novel Barish-e-Sang, I think, is the finest novel written on the lives of Telangana’s tillers and agricultural labourers, which displays her depth of understanding of class and patriarchy in a way that very few texts I’ve read in any language have.It’s not as if someone who has not studied Marx or, indeed in a classroom, doesn’t know how class works.

A lot of this material comes from the lived experiences of the women. They explore all sorts of worlds in their work, including their own personal lives, the institution of marriage, what is called mother work, the running of the household, their professional and social lives, their relationships etc.

You talk about the family magazines run by these writers as teens and young adults. Tell us more about what prompted them to start their own magazines?

They were very enthusiastic about books and learning and frequently had parents who were supportive of their efforts. But they could either not afford to or were not allowed to go to the new women’s associations and their meetings. So these young girls and sometimes even their brothers and male cousins would get together and say, ‘Okay, so we can’t get a subscription to this magazine, or this newspaper, because they’re too expensive, or they’re simply not there. So, let’s make our own magazines.’ And so they produced these painstakingly handwritten monthly magazines, which would be circulated within their families.

Jeelani Bano came from an intellectually rich but financially poor family that had a lot of talented and creative children. The family couldn’t afford a lot of paper, and whatever paper was available was used for the boys’ school work. So she and her siblings used discarded office files and old papers that had one side filled and the other side plain for their magazine.

You write about institutions that encouraged humour writing among women. That seems to be a very unique situation. Tell us more about how they fostered this unique genre of writing.

Yes, these institutions include publications such as Shagoofa , Siasat , Munsif , Rehnuma-e-Dakkan , and Andhra Pradesh . There were also initiatives by organisations such as Zinda Dilaan-e-Hyderabad, which was formed in 1973 with the specific intention of promoting humour and satire, and the Mehfil-e-Khawateen, which is a monthly literary gathering of, by, and for women. The Mehfil-e-Khawateen was founded in 1971 and has been a fertile ground for women to get together and discuss their work and for new women writers to emerge. The women’s department of the Idara-e-Adabiyat-e-Urdu also played an important role in promoting women’s humour.

Progressive writing also provided a platform [for humour writing] because laughter is a great way to expose the hypocrisy of society and also to speak truth to power. But the Progressive Writers’ Association also became hegemonic and exerted restrictions on member and non-member writers on what and how to write. Manto was almost shunned by them after he wrote stories probing the issue of masculinity and violence. Similarly, Hyderabadis were very uncomfortable with Wajida Tabassum because she talks about female sexuality and caste, which is not something that the card-carrying faction of the progressive writers was very familiar with. At the same time, writers such as Zeenath Sajida, for instance, and many other women found a great platform in progressive writing.

What you see in women’s writing is also a very clever use of the humour genre. So, Zeenath Sajida in her irrepressibly cheeky way, uses the genre of the inshaiya , or “light sketch,” to say all kinds of things which have serious implications and which are radical and subversive and completely destructive of old norms. She also uses the pen portrait ( khaake ), a very popular form in Hyderabad. Another proponent of this particular genre is Fatima Alam Ali , who writes intimate and vulnerable portraits of all of the great male progressive writers, and we see them in a way that we’ve never seen in any of their biographies, where they are eulogised by their followers.

The final network that’s important to remember is that of students and teachers because so many of the women writers of Hyderabad have been teachers and professors. And they have trained and nurtured each other. Zeenath Sajida, for instance, had for a teacher Jahanbano Naqvi, who was a writer herself and encouraged Sajida and her other students to write. There was a bonding and a sisterhood between them which outlived courses and degrees.

There’s an anthology of humour writing by Habib Zia where so many of the women humorists represented in it are her friends, students, teachers or colleagues.

You maintain that in the context of contemporary feminist discourse the writings of these women may seem outdated, but they still deserve to be recognised and researched.

This writing merits investigation from the perspective of a history we have to restore. Of course, it’s going to be different from the kind of writing that you have today because it belongs to another period. I frequently come across this problem with my students: when they read [19 th century feminist activist] Tarabai Shinde’s essay ‘Stree Purush Tulana’, for example, they say, why is she saying that though marriage is unfair to women, it is still important for women to remain married? Why isn’t she speaking out against marriage? But it was too early in the day for that kind of radical intent to happen. Tarabai may have thought about it, but it was not the time to articulate the total rejection of marriage. Similarly, you cannot expect someone like Najma Nikhat to make an argument such as ‘Why is raising a daughter a bigger deal than raising a son? Why isn’t a father held responsible for raising a child, daughter or son?’ Najma Nikhat lived in a different world. We frequently forget that we have been able to reach this stage where our politics is so much more radical — and we can articulate positions that are so much more empowering — on the shoulders of these women. We can actually talk about how marriage and motherhood no longer define a woman.

Let’s take Jeelani Bano as another case in point. Bano is very critical of women working outside the home; they are always portrayed as somehow morally compromised in her writing. But you also have to remember that this is a home-schooled woman, who faced the snobbery of the intellectuals and those who were formally educated. It’s easy to understand why she would think of people in workspaces as somehow hostile to her and her world.

Najma Nikhat’s The Last Haveli is an incredibly evocative story of the place of working women in feudal establishments or deodi s.