- Daily Weather Forecast

- Weather Outlook Selected Philippine Cities

- Philippine Cities Weather Forecast

- Asian Cities Weather Forecast

- Weather Outlook Selected Tourist Areas

- Weekly Weather Outlook

- Weather Advisory

- Airways and Terminal Forecast

- Terminal Aerodome Forecast

- High Seas Forecast

- Gale Warning

- Daily Temperature

- Flood Information

- Dam Information

- Tropical Cyclone Advisory --> Tropical Cyclone Advisory Active -->

- Tropical Cyclone Bulletin Tropical Cyclone Bulletin -->

- Tropical Cyclone Warning for Shipping Tropical Cyclone Warning for Shipping -->

- Forecast Storm Surge

- Tropical Cyclone Warning for Agriculture

- TC-Threat Potential Forecast

- Tropical Cyclone Associated Rainfall

- Annual Report on Philippine Tropical Cyclones

- Tropical Cyclone Preliminary Report

- About Tropical Cyclone

- Daily Rainfall and Temperature

- Monthly Monitoring Products

- Southeast Asia Climate Monitoring

- Climate Forum

- 10 Day Climate Forecast

- Sub Seasonal

- Seasonal Forecast

- Specialized Forecast

- Climate Advisories

- CliMap v2.0

- Statistical Downscaling

- Climate Data

- Farm Weather Forecast

- Weekend/Special Farm Weather Forecast

- Ten-Day Regional Agri-Weather Information

- Monthly Philippine Agro-Climatic Review and Outlook

- Impact Assessment for Agriculture

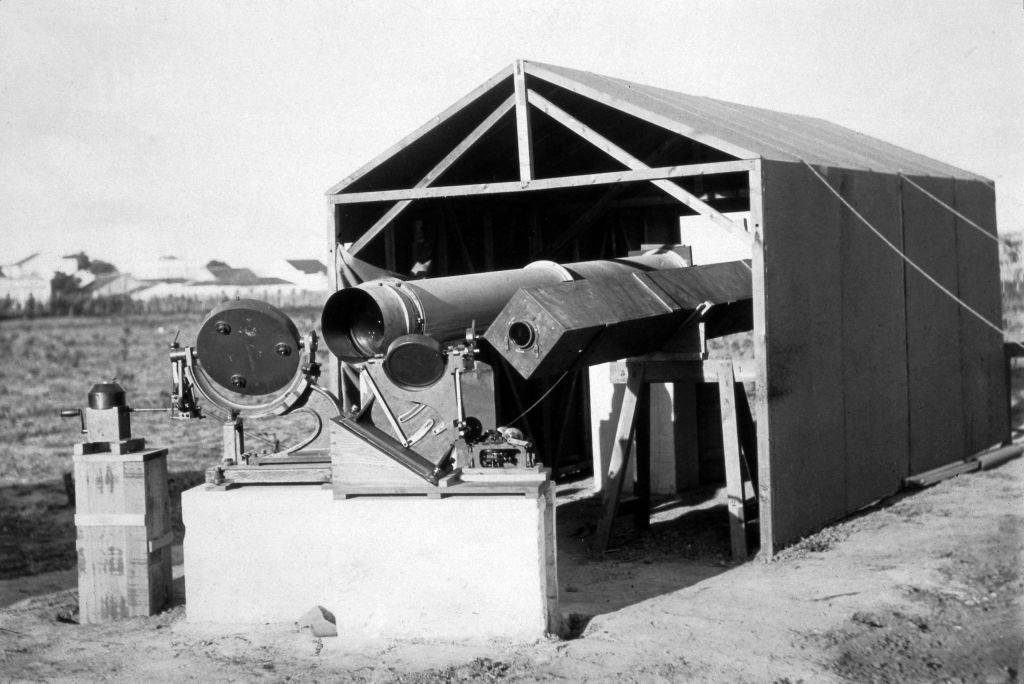

- Telescoping and Stargazing

- Astronomy in the Philippines

- Planetarium

- Astronomical Observatory

- Time Service

- Philippine Standard Time

- Astronomical Diary

- Northern Luzon

- National Capital Region

- Southern Luzon

Introduction

Climate change is happening now. Evidences being seen support the fact that the change cannot simply be explained by natural variation. The most recent scientific assessments have confirmed that this warming of the climate system since the mid-20th century is most likely to be due to human activities; and thus, is due to the observed increase in greenhouse gas concentrations from human activities, such as the burning of fossil fuels and land use change. Current warming has increasingly posed quite considerable challenges to man and the environment, and will continue to do so in the future. Presently, some autonomous adaptation is taking place, but we need to consider a more pro-active adaptation planning in order to ensure sustainable development.

What does it take to ensure that adaptation planning has a scientific basis? Firstly, we need to be able to investigate the potential consequences of anthropogenic or human induced climate change and to do this, a plausible future climate based on a reliable and accurate baseline (or present) climate must be constructed. This is what climate scientists call a climate change scenario. It is a projection of the response of the climate system to future emissions or concentrations of greenhouse gases and aerosols, and is simulated using climate models. Essentially, it describes possible future changes in climate variables (such as temperatures, rainfall, storminess, winds, etc.) based on baseline climatic conditions.

The climate change scenarios outputs (projections) are an important step forward in improving our understanding of our complex climate, particularly in the future. These show how our local climate could change dramatically should the global community fail to act towards effectively reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Climate Change Scenarios

As has been previously stated, climate change scenarios are developed using climate models (UNFCCC). These models use mathematical representations of the climate system, simulating the physical and dynamical processes that determine global/regional climate. They range from simple, one-dimensional models to more complex ones such as global climate models (known as GCMs), which model the atmosphere and oceans, and their interactions with land surfaces. They also model change on a regional scale (referred to as regional climate models), typically estimating change in areas in grid boxes that are approximately several hundred kilometers wide. It should be noted that GCMs/RCMs provide only an average change in climate for each grid box, although realistically climates can vary considerably within each grid. Climate models used to develop climate change scenarios are run using different forcings such as the changing greenhouse gas concentrations. These emission scenarios known as the SRES (Special Report on Emission Scenarios) developed by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) to give the range of plausible future climate. These emission scenarios cover a range of demographic, societal, economic and technological storylines. They are also sometimes referred to as emission pathways. Table 1 presents the four different storylines (A1, A2, B1 and B2) as defined in the IPCC SRES.

Climate change is driven by factors such as changes in the atmospheric concentration of greenhouse gases and aerosols, land cover and radiation, and their combinations, which then result in what is called radiative forcing (positive or warming and negative or cooling effect). We do not know how these different drivers will specifically affect the future climate, but the model simulation will provide estimates of its plausible ranges.

A number of climate models have been used in developing climate scenarios. The capacity to do climate modeling usually resides in advanced meteorological agencies and in international research laboratories for climate modeling such as the Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research of the UK Met Office (in the United kingdom), the National Center for Atmospheric Research and the Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory (in the United States), the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology (in Germany), the Canadian Centre for Climate Modeling and Analysis (in Canada), the Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization (in Australia), the Meteorological Research Institute of the Japan Meteorological Agency (in Japan), and numerous others. These centers have been developing their climate models and continuously generate new versions of these models in order address the limitations and uncertainties inherent in models.

For the climate change scenarios in the Philippines presented in this Report, the PRECIS (Providing Regional Climates for Impact Studies) model was used. It is a PC-based regional climate model developed at the UK Met Office Hadley Centre for Climate Prediction and Research to facilitate impact, vulnerability and adaptation assessments in developing countries where capacities to do modeling are limited. Two time slices centered on 2020 (2006-2035) and 2050 (2036-2065) were used in the climate simulations using three emission scenarios; namely, the A2 (high-range emission scenario), the A1B (medium- range emission scenario) and the B2 (low-range emission scenario).

The high-range emission scenario connotes that society is based on self-reliance, with continuously growing population, a regionally-oriented economic development but with fragmented per capita economic growth and technological change. On the other hand, the mid-range emission scenario indicates a future world of very rapid economic growth, with the global population peaking in mid-century and declining thereafter and there is rapid introduction of new and more efficient technologies with energy generation balanced across all sources. The low-range emission scenario, in contrast, indicates a world with local solutions to economic, social, and environmental sustainability, with continuously increasing global population, but at a rate lower than of the high-range, intermediate levels of economic development, less rapid and more diverse technological change but oriented towards environment protection and social equity.

To start the climate simulations or model runs, outputs (climate information) from the relatively coarse resolution GCMs are used to provide high resolution (using finer grid boxes, normally 10km-100km) climate details, through the use of downscaling techniques. Downscaling is a method that derives local to regional scale (10km-100km x 10km-100km grids) information from larger-scale models (150km-300km x 150km-300km grids) as shown in Fig.1. The smaller the grid, the finer is the resolution giving more detailed climate information.

The climate simulations presented in this report used boundary data that were from the ECHAM4 and HadCM3Q0 (the regional climate models used in the PRECIS model software).

How were the downscaling techniques applied using the PRECIS model?

To run regional climate models, boundary conditions are needed in order to produce local climate scenarios. These boundary conditions are outputs of the GCMs. For the PRECIS model, the following boundary data and control runs were used:

For the high-range scenario, the GCM boundary data used was from ECHAM4. This is the 4th generation coupled ocean-atmosphere general circulation model, which uses a comprehensive parameterization package developed at the Max Planck Institute for Meteorology in Hamburg, Germany. Downscaling was to a grid resolution of 25km x 25km; thus, allowing more detailed regional information of the projected climate. Simulated baseline climate used for evaluation of the models capacity of reproducing present climate was the 1971-2000 model run. Its outputs were compared with the 1971-2000 observed values.

For the mid-range scenario, the GCM boundary data was from the HadCM3Q0 version 3 of the coupled model developed at the Hadley Centre. Downscaling was also to a grid resolution of 25km x 25km and the same validation process was undertaken.

For running the low-range scenario, the same ECHAM4 model was used. However, the validation process was only for the period of 1989 to 2000 because the available GCM boundary data in the model was limited to this period.

The simulations for all 3 scenarios were for three periods; 1971 to 2000, 2020 and 2050. The period 1971 to 2000 simulation is referred to as the baseline climate, outputs of which are used to evaluate the models capacity of reproducing present climate (in other words, the control run). By comparing the outputs (i.e., temperature and rainfall) with the observed values for the 1971 to 2000 period, the models ability to realistically represent the regional climatological features within the country is verified. The differences between the outputs and the observed values are called the biases of the model. The 2020 and 2050 outputs are then mathematically corrected, based on the comparison of the models performance.

The main outputs of the simulations for the three SRES scenarios (high-range, mid-range and low-range) are the following:

- projected changes in seasonal and annual mean temperature

- projected changes in minimum and maximum temperatures

- projected changes in seasonal rainfall and

- projected frequency of extreme events

The seasonal variations are as follows:

- the DJF (December, January, February or northeast monsoon locally known as amihan) season

- the MAM (March, April, May or summer) season

- the JJA (June, July, August or southwest monsoon season, or habagat) season and

- the SON (September, October, November or transition from southwest to northeast monsoon) season

On the other hand, extreme events are defined as follows:

- extreme temperature (assessed as number of days with maximum temperature greater than 35°C, following the threshold values used in other countries in the Asia Pacific region)

- dry days (assessed as number of dry days or day with rainfall equal or less than 2.5mm/day, following the World Meteorological Organization standard definition of dry days used in a number of countries) and

- extreme rainfall (assessed as number of days with daily rainfall greater than 300mm, which for wet tropical areas, like the Philippines, is considerably intense that could trigger disastrous events).

How were the uncertainties in the modeling simulations dealt with?

Modeling of our future climate always entails uncertainties. These are inherent in each step in the simulations/modeling done because of a number of reasons. Firstly, emissions scenarios are uncertain. Predicting emissions is largely dependent on how we can predict human behavior, such as changes in population, economic growth, technology, energy availability and national and international policies (which include predicting results of the international negotiations on reducing greenhouse gas emissions). Secondly, current understanding of the carbon cycle and of sources and sinks of non-carbon greenhouse gases are still incomplete. Thirdly, consideration of very complex feedback processes in the climate system in the climate models used can also contribute to the uncertainties in the outputs generated as these could not be adequately represented in the models.

But while it is difficult to predict global greenhouse gas emission rates far into the future, it is stressed that projections for up to 2050 show little variation between different emission scenarios, as these near-term changes in climate are strongly affected by greenhouse gases that have already been emitted and will stay in the atmosphere for the next 50 years. Hence, for projections for the near-term until 2065, outputs of the mid-range emission scenario are presented in detail in this Report.

Ideally, numerous climate models and a number of the emission scenarios provided in the SRES should be used in developing the climate change scenarios in order to account for the limitations in each of the models used, and the numerous ways global greenhouse gas emissions would go. The different model outputs should then be analyzed to calculate the median of the future climate projections in the selected time slices. By running more climate models for each emission scenarios, the higher is the statistical confidence in the resulting projections as these constitute the ensemble representing the median values of the model outputs.

The climate projections for the three emission scenarios were obtained using the PRECIS model only due to several constraints and limitations. These constraints and limitations are:

Access to climate models: at the start, PAGASA had not accessed climate models due to computing and technical capacity requirements needed to run them;

Time constraints: the use of currently available computers required substantial computing time to run the models (measured in weeks and months). This had been partly addressed under the capacity upgrading initiatives being implemented by the MDGF Joint Programme which include procurement of more powerful computers and acquiring new downscaling techniques. Improved equipment and new techniques have reduced the computing time requirements to run the models. However, additional time is still needed to run the models using newly acquired downscaling techniques; and

The PAGASA strives to improve confidence in the climate projections and is continuously exerting efforts to upgrade its technical capacities and capabilities. Models are run as soon as these are acquired with the end-goal of producing an ensemble of the projections. Updates on the projections, including comparisons with the current results, will be provided as soon as these are available.

What is the level of confidence in the climate projections?

The IPCC stresses that there is a large degree of uncertainty in predicting what the future world will be despite taking into account all reasonable future developments. Nevertheless, there is high confidence in the occurrence of global warming due to emissions of greenhouse gases caused by humans, as affirmed in the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (AR4). Global climate simulations done to project climate scenarios until the end of the 21st century indicate that, although there are vast differences between the various scenarios, the values of temperature increase begin to diverge only after the middle of this century (shown in Fig.3). The long lifetimes of the greenhouse gases (in particular, that of carbon dioxide) already in the atmosphere is the reason for this behavior of this climate response to largely varying emission scenarios.

Model outputs that represent the plausible local climate scenarios in this Report are indicative to the extent that they reflect the large-scale changes (in the regional climate model used) modified by the projected local conditions in the country.

It also should be stressed further that confidence in the climate change information depends on the variable being considered (e.g., temperature increase, rainfall change, extreme event indices, etc.). In all the model runs regardless of emission scenarios used, there is greater confidence in the projections of mean temperature than that of the others. On the other hand, projections of rainfall and extreme events entail consideration of convective processes which are inherently complex, and thus, limiting the degree of confidence in the outputs.

What are the possible applications of these model-generated climate scenarios?

Climate scenarios are commonly required in climate change impact, vulnerability and adaptation assessments to provide alternative views of future conditions considered likely to affect society, systems and sectors, including a quantification of climate risks, challenges and opportunities. climate scenario outputs could be used in any of the following:.

- to illustrate projected climate change in a given administrative region/province

- to provide data for impact/adaptation assessment studies

- to communicate potential consequences of climate change (e.g., specifying a future changed climate to estimate potential shifts in say, vegetation, species threatened or at risk of extinction, etc.) and

- for strategic planning (e.g., quantifying projected sea level rise and other climate changes for the design of coastal infrastructure/defenses such as sea walls, etc.)

Current Climate and Observed Trends

Current climate change in the philippines.

The world has increasingly been concerned with the changes in our climate due largely to adverse impacts being seen not just globally, but also in regional, national and even, local scales. In 1988, the United Nations established the IPCC to evaluate the risks of climate change and provide objective information to governments and various communities such as the academe, research organizations, private sector, etc. The IPCC has successively done and published its scientific assessment reports on climate change, the first of which was released in 1990. These reports constitute consensus documents produced by numerous lead authors, contributing authors and review experts representing Country Parties of the UNFCCC, including invited eminent scientists in the field from all over the globe.

In 2007, the IPCC made its strongest statement yet on climate change in its Fourth Assessment Report (AR4), when it concluded that the warming of the climate system is unequivocal, and that most of the warming during the last 50 years or so (e.g., since the mid-20th century) is due to the observed increase in greenhouse gas concentrations from human activities. It is also very likely that changes in the global climate system will continue into the future, and that these will be larger than those seen in our recent past (IPCC, 2007a).

Fig.4 shows the 0.74 C increase in global mean temperature during the last 150 years compared with the 1961-1990 global average. It is the steep increase in temperature since the mid-20th century that is causing worldwide concern, particularly in terms of increasing vulnerability of poor developing countries, like the Philippines, to adverse impacts of even incremental changes in temperatures.

The IPCC AR4 further states that the substantial body of evidence that support this most recent warming includes rising surface temperature, sea level rise and decrease in snow cover in the Northern Hemisphere (shown in Fig.5).

Additionally, there have been changes in extreme events globally and these include;

- widespread changes in extreme temperatures observed;

- cold days, cold nights and frost becoming less frequent;

- hot days, hot nights and heat waves becoming more frequent; and

- observational evidence for an increase of intense tropical cyclone activity in the North Atlantic since about 1970, correlated with increases of tropical sea surface temperatures (SSTs).

However, there are differences between and within regions. For instance, in the Southeast Asia region which includes Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Vietnam, among others, temperature increases have been observed; although magnitude varies from one country to another. Changes in rainfall patterns, characteristically defined by changes in monsoon performance, have also been noted. Analysis of trends of extreme daily events (temperatures and rainfall) in the Asia Pacific region (including Australia and New Zealand, and parts of China and Japan) also indicate spatial coherence in the increase of hot days, warm nights and heat waves, and the decrease of cold days, cold nights and frost; although, there is no definite direction of rainfall change across the entire region (Manton et. al., 2001).

Current Climate Trends in the Philippines

The Philippines, like most parts of the globe, has also exhibited increasing temperatures as shown in Fig.6 below. The graph of observed mean temperature anomalies (or departures from the 1971-2000 normal values) during the period 1951 to 2010 indicate an increase of 0.648 C or an average of 0.0108 C per year-increase.

The increase in maximum (or daytime) temperatures and minimum (or night time) temperatures are shown in Fig.7 and Fig.8. During the last 60 years, maximum and minimum temperatures are seen to have increased by 0.36 ºC and 1.0°C, respectively.

Analysis of trends of tropical cyclone occurrence or passage within the so-called Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) show that an average of 20 tropical cyclones form and/or cross the PAR per year. The trend shows a high variability over the decades but there is no indication of increase in the frequency. However, there is a very slight increase in the number of tropical cyclones with maximum sustained winds of greater than 150kph and above (typhoon category) being exhibited during El NiÑo event (See Fig.10).

Moreover, the analysis on tropical cyclone passage over the three main islands (Luzon, Visayas and Mindanao), the 30-year running means show that there has been a slight increase in the Visayas during the 1971 to 2000 as compared with the 1951 to 1980 and 1960-1990 periods (See Fig.11).

To detect trends in extreme daily events, indices had been developed and used. Analysis of extreme daily maximum and minimum temperatures (hot-days index and cold-nights index, respectively) show there are statistically significant increasing number of hot days but decreasing number of cool nights (as shown in Fig.12 and Fig.13).

However, the trends of increases or decreases in extreme daily rainfall are not statistically significant; although, there have been changes in extreme rain events in certain areas in the Philippines. For instance, intensity of extreme daily rainfall is already being experienced in most parts of the country, but not statistically significant (see in Fig.14). Likewise, the frequency has exhibited an increasing trend, also, not statistically significant (as shown in Fig.15).

The rates of increases or decreases in the trends are point values (i.e., specific values in the synoptic weather stations only) and are available at PAGASA, if needed.

Climate Projections

Projections on seasonal temperature increase and rainfall change, and total frequency of extreme events nationally and in the provinces using the mid-range scenario outputs are presented in this chapter. A comparison of these values with the high- and low- range scenarios in 2020 and 2050 is provided in the technical annexes.

It is to be noted that all the projected changes are relative to the baseline (1971-2000) climate. For example, a projected 1.0 C-increase in 2020 in a province means that 1.0 C is added to the baseline mean temperature value of the province as indicated in the table to arrive at the value of projected mean temperature. Therefore, if the baseline mean temperature is 27.8 C, then the projected mean temperature in the future is (27.8 C + 1.0 C) or 28.8 C.

In a similar manner, for say, a +25%-rainfall change in a province, it means that 25% of the seasonal mean rainfall value in the said province (from table of baseline climate) is added to the mean value. Thus, if the baseline seasonal rainfall is 900mm, then projected rainfall in the future is 900mm + 225mm or 1125mm.

This means that we are already experiencing some of the climate change shown in the findings under the mid-range scenario, as we are now into the second decade of the century. Classification of climate used the Corona's four climate types (Types I to IV), based on monthly rainfall received during the year. A province is considered to have Type I climate if there is a distinct dry and a wet season; wet from June to November and dry, the rest of the year. Type II climate is when there is no dry period at all throughout the year, with a pronounced wet season from November to February. On the other hand, Type III climate is when there is a short dry season, usually from February to April, and Type IV climate is when the rainfall is almost evenly distributed during the whole year. The climate classification in the Philippines is shown in Fig.16.

Seasonal Temperature Change

All areas of the Philippines will get warmer, more so in the relatively warmer summer months. Mean temperatures in all areas in the Philippines are expected to rise by 0.9 C to 1.1 C in 2020 and by 1.8 C to 2.2 C in 2050. Likewise, all seasonal mean temperatures will also have increases in these time slices; and these increases during the four seasons are quite consistent in all parts of the country. Largest temperature increase is projected during the summer (MAM) season.

Seasonal Rainfall Change

Generally, there is reduction in rainfall in most parts of the country during the summer (MAM) season. However, rainfall increase is likely during the southwest monsoon (JJA) season until the transition (SON) season in most areas of Luzon and Visayas, and also, during the northeast monsoon (DJF) season, particularly, in provinces/areas characterized as Type II climate in 2020 and 2050. There is however, generally decreasing trend in rainfall in Mindanao, especially by 2050.

There are varied trends in the magnitude and direction of the rainfall changes, both in 2020 and 2050. What the projections clearly indicate are the likely increase in the performance of the southwest and the northeast monsoons in the provinces exposed to these climate controls when they prevail over the country. Moreover, the usually wet seasons become wetter with the usually dry seasons becoming also drier; and these could lead to more occurrences of floods and dry spells/droughts, respectively.

Extreme Temperature Events

Hot temperatures will continue to become more frequent in the future. Fig.19 shows that the number of days with maximum temperature exceeding 35 C (following value used by other countries in the Asia Pacific region in extreme events analysis) is increasing in 2020 and 2050.

Extreme Rainfall Events

Heavy daily rainfall will continue to become more frequent, extreme rainfall is projected to increase in Luzon and Visayas only, but number of dry days is expected to increase in all parts of the country in 2020 and 2050. Figures 20 and 21 show the projected increase in number of dry days (with dry day defined as that with rainfall less than 2.5mm) and the increase in number of days with extreme rainfall (defined as daily rainfall exceeding 300 mm) compared with the observed (baseline) values, respectively.

Climate Projections for Provinces

Impacts of climate change.

Climate change is one of the most fundamental challenges ever to confront humanity. Its adverse impacts are already being seen and may intensify exponentially over time if nothing is done to reduce further emissions of greenhouse gases. Decisively dealing NOW with climate change is key to ensuring sustainable development, poverty eradication and safeguarding economic growth. Scientific assessments indicate that the cost of inaction now will be more costly in the future. Thus, economic development needs to be shifted to a low-carbon emission path.

In 1992, the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) was adopted as the basis for a global response to the problem. The Philippines signed the UNFCCC on 12 June 1992 and ratified the international treaty on 2 August 1994. Presently, the Convention enjoys near-universal membership, with 194 Country Parties.

Recognizing that the climate system is a shared resource which is greatly affected by anthropogenic emissions of greenhouse gases, the UNFCCC has set out an overall framework for intergovernmental efforts to consider what can be done to reduce global warming and to cope with whatever temperature increases are inevitable. Its ultimate objective is to stabilize greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere at a level that will prevent dangerous human interference with the climate system.

Countries are actively discussing and negotiating ways to deal with the climate change problem within the UNFCCC using two central approaches. The first task is to address the root cause by reducing greenhouse gas emissions from human activity. The means to achieve this are very contentious, as it will require radical changes in the way many societies are organized, especially in respect to fossil fuel use, industry operations, land use, and development. Within the climate change arena, the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions is called mitigation.

The second task in responding to climate change is to manage its impacts. Future impacts on the environment and society are now inevitable, owing to the amount of greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere from past decades of industrial and other human activities, and to the added amounts from continued emissions over the next few decades until such time as mitigation policies and actions become effective. We are therefore committed to changes in the climate. Taking steps to cope with the changed climate conditions both in terms of reducing adverse impacts and taking advantage of potential benefits is called adaptation.

What if the emissions are less or greater?

Responses of the local climate to the mid-range compared to the high- and low-range scenarios are as shown in Fig. 22 below. Although there are vast differences in the projections, the so-called temperature anomalies or difference in surface temperature increase begin to diverge only in the middle of the 21st century. As has already been stated, the climate in the next 30 to 40 years is greatly influenced by past greenhouse gas emissions. The long lifetimes of the greenhouse gases already in the atmosphere, with the exception of methane (with a lifetime of only 13 years), will mean that it will take at least 30 to 40 years for the atmosphere to stabilize even if mitigation measures are put in place, not withstanding that in the near future, there could be some off-setting between sulfate aerosols (cooling effect) and the greenhouse gas concentrations (warming effect).

Likely impacts of Climate Change

A warmer world is certain to impact on systems and sectors; although, magnitude of impacts will depend on factors such as sensitivity, exposure and adaptive capacity to climate risks. In most cases, likely impacts will be adverse. However, there could be instances when likely impacts present opportunities for potential benefits as in the case of the so-called carbon fertilization effect in which increased carbon dioxide could lead to increased yield provided temperatures do not exceed threshold values for a given crop/cultivar.

Water Resources

In areas/regions where rainfall is projected to decrease, there will be water stress (both in quantity and quality), which in turn, will most likely cascade into more adverse impacts, particularly on forestry, agriculture and livelihood, health, and human settlement. Large decreases in rainfall and longer drier periods will affect the amount of water in watersheds and dams which provide irrigation services to farmers, especially those in rain fed areas, thereby, limiting agricultural production. Likewise, energy production from dams could also be rendered insufficient in those areas where rainfall is projected to decrease, and thus, could largely affect the energy sufficiency program of the country. Design of infrastructure, particularly of dams, will need to be re-visited to ensure that these will not be severely affected by the projected longer drier periods.

In areas where rainfall could be intense during wet periods, flooding events would follow and may pose danger to human settlements and infrastructure, in terms of landslides and mudslides, most especially, in geologically weak areas. Additionally, these flooding events could impact severely on public infrastructure, such as roads and bridges, including classrooms, evacuation centers, and hospitals.

Adaptive capacity is enhanced when impact and vulnerability assessments are used as the basis of strategic and long-term planning for adaptation. Assessments would indicate areas where critical water shortages can be expected leading to possible reduction of water available for domestic consumption, less irrigation service delivery, and possibly, decreased energy generation in dams. Note that the adverse impacts would cascade, so that long-term pro-active planning for these possible impacts is imperative in order to be able to respond effectively, and avoid maladaptations. A number of adaptation strategies should be considered. Among the wide array of cost effective options are rational water management, planning to avoid mismatch between water supply and demand through policies, upgrading/rehabilitation of dams where these are cost-effective, changes in cropping patterns in agricultural areas, establishing rain water collection facilities, where possible, and early warning systems.

Changes in rainfall regimes and patterns resulting to increase/decrease in water use and temperature increases could lead to a change in the forests ecosystem, particularly in areas where the rains are severely limited, and can no longer provide favorable conditions for certain highly sensitive species. Some of our forests could face die-backs. Additionally, drier periods and warmer temperatures, especially during the warm phase of El Nino events, could cause forest fires. A very likely threat to communities that largely depend on the ecological services provided by forests is that they may face the need to alter their traditions and livelihoods. This change in practices and behavior can lead to further degradation of the environment as they resort to more extensive agricultural production in already degraded areas.

Adverse impacts on forestry areas and resources could be expected to multiply in a future warmer world. The value of impact and vulnerability assessments could not be underscored. These assessments would help decision makers and stakeholders identify the best option to address the different impacts on forest areas, watersheds and agroforestry. Indigenous communities have to plan for climate-resilient alternative livelihoods. Thus, it is highly important to plan for rational forest management, particularly, in protected areas and in ancestral domains. One of the more important issues to consider is how to safeguard livelihoods in affected communities so as not to further exacerbate land degradation. Early warning systems in this sector will play a very important role in forest protection through avoidance and control/containment of forest fires.

Agriculture

Agriculture in the country could be severely affected by temperature changes coupled with changes in rain regimes and patterns. Crops have been shown to suffer decreases in yields whenever temperatures have exceeded threshold values and possibly result to spikelet sterility, as in the case of rice. The reduction in crop yield would remain unmitigated or even aggravated if management technologies are not put in place. Additionally, in areas where rain patterns change or when extreme events such as floods or droughts happen more often, grain and other agricultural produce could suffer shortfalls in the absence of effective and timely interventions. Tropical cyclones, particularly if there will be an increase in numbers and/or strength will continue to exert pressure on agricultural production.

Moreover, temperature increases coupled with rainfall changes could affect the incidence/outbreaks of pests and diseases, both in plants and animals. The pathways through which diseases and pests could be triggered and rendered most favorable to spread are still largely unknown. It is therefore important that research focus on these issues.

In the fisheries sub-sector, migration of fish to cooler and deeper waters would force the fisher folks to travel further from the coasts in order to increase their catch. Seaweed production, already being practiced as an adaptation to climate change in a number of poor and depressed coastal communities could also be impacted adversely.

Decreased yields and inadequate job opportunities in the agricultural sector could lead to migration and shifts in population, resulting to more pressure in already depressed urban areas, particularly in mega cities. Food security will largely be affected, especially if timely, effective and efficient interventions are not put in place. Insufficient food supply could further lead to more malnutrition, higher poverty levels, and possibly, heightened social unrest and conflict in certain areas in the country, and even among the indigenous tribes.

A careful assessment of primary and secondary impacts in this sector, particularly, in production systems and livelihoods will go a long way in avoiding food security and livelihood issues. Proactive planning (short- and long-term adaptation measures) will help in attaining poverty eradication, sufficient nutrition and secure livelihoods goals. There is a wide cross-section of adaptation strategies that could be put in place, such as horizontal and vertical diversification of crops, farmer field schools which incorporate use of weather/climate information in agricultural operations, including policy environment for subsidies and climate-friendly agricultural technologies, weather-based insurance, and others. To date, there has not been much R&D that has been done on inland and marine fisheries technologies, a research agenda on resilient marine sector could form part of long-term planning for this subsector.

Coastal Resources

The countrys coastal resources are highly vulnerable due to its extensive coastlines. Sea level rise is highly likely in a changing climate, and low-lying islands will face permanent inundation in the future. The combined effects of continued temperature increases, changes in rainfall and accelerated sea level rise, and tropical cyclone occurrences including the associated storm surges would expose coastal communities to higher levels of threat to life and property. The livelihood of these communities would also be threatened in terms of further stress to their fishing opportunities, loss of productive agricultural lands and saltwater intrusion, among others.

Impact and vulnerability assessment as well as adaptation planning for these coastal areas are of high priority. Adaptation measures range from physical structures such as sea walls where they still are cost-effective, to development/revision of land use plans using risk maps as the basis, to early warning systems for severe weather, including advisories on storm surge probabilities, as well as planning for and developing resilient livelihoods where traditional fishing/ agriculture are no longer viable.

Human health is one of the most vital sectors which will be severely affected by climate change. Incremental increases in temperatures and rain regimes could trigger a number of adverse impacts; in particular, the outbreak and spread of water-based and vector-borne diseases leading to higher morbidity and mortality; increased incidence of pulmonary illnesses among young children and cardiovascular diseases among the elderly. In addition, there could also be increased health risk from poor air quality especially in urbanized areas.

Surveillance systems and infrastructure for monitoring and prevention of epidemics could also be under severe stress when there is a confluence of circumstances. Hospitals and clinics, and evacuation centers and resettlement areas could also be severely affected under increased frequency and intensity of severe weather events.

Moreover, malnutrition is expected to become more severe with more frequent occurrences of extreme events that disrupt food supply and provision of health services. The services of the Department of Health will be severely tested unless early and periodic assessments of plausible impacts of climate change are undertaken.

Scientific assessments have indicated that the Earth is now committed to continued and faster warming unless drastic global mitigation action is put in place the soonest. The likely impacts of climate change are numerous and most could seriously hinder the realization of targets set under the Millennium Development Goals; and thus, sustainable development. Under the UNFCCC, Country Parties have common but differentiated responsibilities. All Country Parties share the common responsibility of protecting the climate system but must shoulder different responsibilities. This means that the developed countries including those whose economies are in transition (or the so-called Annex 1 Parties) have an obligation to reduce their greenhouse gas emissions based on their emissions at 1990 levels and provide assistance to developing countries (or the so-called non-Annex 1 Parties) to adapt to impacts of climate change.

In addition, the commitment to mitigate or reduce anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions by countries which share the responsibility of having historically caused this global problem, as agreed upon in the Kyoto Protocol, is dictated by the imperative to avoid what climate scientists refer to as the climate change tipping point. Tipping point is defined as the maximum temperature increase that could happen within the century, which could lead to sudden and dramatic changes to some of the major geophysical elements of the Earth. The effects of these changes could be varied from a dramatic rise in sea levels that could flood coastal regions to widespread crop failures. But, it still is possible to avoid them with cuts in anthropogenic greenhouse gases, both in the developed and developing countries, in particular, those which are now fast approaching the emission levels seen in rich countries.

In the Philippines, there are now a number of assisted climate change adaptation programmes and projects that are being implemented. Among these are the Millennium Development Goals Fund 1656: Strengthening the Philippines Institutional Capacity to Adapt to Climate Change funded by the Government of Spain, the Philippine Climate Change Adaptation Project (which aims to develop the resiliency and test adaptation strategies that will develop the resiliency of farms and natural resource management to the effects of climate change) funded by the Global Environmental Facility(GEF) through the World Bank, the Adaptation to Climate Change and Conservation of Biodiversity Project and the National Framework Strategy on Climate Change (envisioned to develop the adaptation capacity of communities), both funded by the GTZ, Germany.

- JOIN A TRAINING

The Philippines: Leading the Way In the Climate Fight

The Philippines is one of the world's most vulnerable countries to climate disasters. With more than 7,100 islands and an estimated 36,298 kilometers of coastline, more than 60 percent of the Filipino population resides within the coastal zone and are acutely impacted by climate change . Dangers include food and fresh water scarcity, damage to infrastructure and devastating sea-level rise. However, with an innate understanding of the acute impacts of climate change, the Philippines is one of the world's strongest voices leading the global movement, combatting the problem and ultimately setting an example in adapting to climate change. The nation is acting with urency and commitment — passing legislation, promoting the use of renewable energy and focusing on country-wide conservation.

That is why former US Vice President Al Gore and The Climate Reality Project hosted the 31st Climate Reality Leadership Corps Training in Manila. The Climate Reality Leadership Corps is a global network of activists committed to taking on the climate crisis and working to solve the greatest challenge of our time. The decade-long program has worked with thousands of individuals, providing training in climate science, communications, and organizing to tell the story of climate change and inspire leaders to be agents of change in their local communities.

As the president and CEO of The Climate Reality Project, I am thrilled to contribute to the training of more than 700 new Climate Reality Leaders . These individuals from all over the world are leaders in their own communities, local governments, and businesses, who each care deeply about combatting climate change. At the training, they had the opportunity to learn from some of the best and brightest in their respective fields including Vice President Gore, Senator Loren Legarda, and Mayor of Tacloban Alfred Romualdez as well as world-class scientists, policy-makers, faith leaders, communicators, and technical specialists. These leaders offered specific guidance to trainees on the science of climate change, the cost of climate impacts, and the Paris Agreement that established the framework to transition to a global clean energy economy. After the training, trainees emerged as energized and skilled communicators with the knowledge, tools, and drive to take action, educating diverse global communities on the costs of carbon pollution and what can be done to solve the climate crisis.

Unsurprisingly, a large percentage of the trainees who attended the event are Filipino. This means that after the training, the great work on climate solutions already happening in the Philippines will accelerate.

Post-COP 21 this could not be more important.

The agreement reached in Paris was a monumental step in the effort to combat climate change with 195 nations agreeing upon an international plan to reduce greenhouse gas emissions worldwide. However, now we have to turn words into action . Success is 100 percent dependent on its provisions being strengthened and implemented over time. Here in the Philippines, that means transitioning the energy economy from coal to renewable energy resources and working to adapt to the realities of climate change .

The Philippines has long relied on dirty coal for energy. In fact, a 300-megawatt coal-fired power plan came online only a few weeks after the Philippines signed the Paris agreement — and this is the first of dozens of coal-fired power plants currently planned. Instead of supporting an energy resource we know is damaging, we must encourage banks and investors to embrace the revolution in renewable energy and encourage the growth and development of the clean energy economy here in the Philippines. The islands have with abundant renewable energy resources such as sun, wind, and ocean tides — now we need to prioritize investing in the infrastructure that turns these existing power sources into reality.

Furthermore, a significant part of the agreement signed by the Philippines in Paris requires conserving, enhancing, and restoring forests country-wide. Over half of the country's commitment to reducing greenhouse gasses is based on plans to avoid deforestation and promote reforestation. Strong support for programs such as the Department of Environment and Natural Resources efforts to restore the country's mangroves, including those running from eastern Samar to Southern Leyte, can make a significant difference in both the reduction of greenhouse gases and mitigating the potential risk and destruction from future storms.

The Philippines is one of the best-positioned countries to make a difference in the climate fight. My hope for the Manila training is that the trainees leave inspired to lead change in their own communities, including supporting and advocating for the crucial policies and changes needed as laid out by the Paris Agreement. If so, I am confident that the Philippines can play a key role in leading the world in halting the progressive destruction of climate change and ensure a sustainable future for us all.

Click here to learn more about how you can make a difference in fighting climate change by becoming a Climate Reality Leader.

Stronger Climate Action Will Support Sustainable Recovery and Accelerate Poverty Reduction in the Philippines

MANILA, November 09, 2022 – Climate change is exacting a heavy toll on Filipinos’ lives, properties, and livelihoods, and left unaddressed, could hamper the country’s ambition of becoming an upper middle-income country by 2040. However, the Philippines has many of the tools and instruments required to reduce damages substantially, according to the World Bank Group’s Country Climate and Development Report (CCDR) for the Philippines, released today.

With 50 percent of its 111 million population living in urban areas, and many cities in coastal areas, the Philippines is vulnerable to sea level rise. Changes due to the variability and intensity of rainfall in the country and increased temperatures will affect food security and the safety of the population.

Multiple indices rank the Philippines as one of the countries most affected by extreme climate events. The country has experienced highly destructive typhoons almost annually for the past 10 years. Annual losses from typhoons have been estimated at 1.2 percent of GDP.

Climate action in the Philippines must address both extreme and slow-onset events. Adaptation and mitigation actions, some of which are already underway in the country, would reduce vulnerability and future losses if fully implemented.

“Climate impacts threaten to significantly lower the country’s GDP and the well-being of Filipinos by 2040. However, policy actions and investments – principally to protect valuable infrastructure from typhoons and to make agriculture more resilient through climate-smart measures -- could reduce these negative climate impacts by two-thirds,” said World Bank Vice President for East Asia and Pacific, Manuela V. Ferro.

The private sector has a crucial role to play in accelerating the adoption of green technologies and ramping up climate finance by working with local financial institutions and regulators.

“ The investments needed to undertake these actions are substantial, but not out of reach, ” said IFC Acting Vice President for Asia and the Pacific, John Gandolfo . “ The business leaders and bankers who embrace climate as a business opportunity and offer these low-carbon technologies, goods and services will be the front runners of our future. ”

The report also undertakes an in-depth analysis of challenges and opportunities for climate-related actions in agriculture, water, energy, and transport. Among the recommendations are:

- Avoiding new construction in flood-prone areas.

- Improving water storage to reduce the risk of damaging floods and droughts. This will also increase water availability.

- Extending irrigation in rainfed areas and promoting climate-smart agriculture practices such as Alternate Wetting and Drying (AWD).

- Making social protection programs adaptive and scalable to respond to climate shocks.

- Removing obstacles that private actors face in scaling investments in renewable energy.

- Ensuring new buildings are energy efficient and climate resilient.

Many climate actions will make the Philippines more resilient while also contributing to mitigating climate change.

“The Philippines would benefit from an energy transition towards more renewable energy. Accelerated decarbonization would reduce electricity costs by about 20 percent below current levels which is good for the country’s competitiveness and would also dramatically reduce air pollution,” said Ferro.

Even with vigorous adaptation efforts, climate change will affect many people. Some climate actions may also have adverse effects on particular groups, such as workers displaced by the move away from high-emission activities. The report recommends that the existing social protection system in the country be strengthened and scaled up to provide support to affected sectors and groups.

World Bank Group Country Climate and Development Reports : The World Bank Group’s Country Climate and Development Reports (CCDRs) are new core diagnostic reports that integrate climate change and development considerations. They will help countries prioritize the most impactful actions to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and boost adaptation while delivering on broader development goals. CCDRs build on data and rigorous research and identify main pathways to reduce GHG emissions and climate vulnerabilities, including the costs and challenges as well as benefits and opportunities from doing so. The reports suggest concrete, priority actions to support the low-carbon, resilient transition. As public documents, CCDRs aim to inform governments, citizens, the private sector, and development partners and enable engagements with the development and climate agenda. CCDRs will feed into other core Bank Group diagnostics, country engagements, and operations to help attract funding and direct financing for high-impact climate action.

- 10 Things You Should Know About the World Bank Group’s First Batch of Country Climate and Development Reports

- CCDR Video link

Download the full report

Watch the video

Key findings

Watch the launch event

The World Bank in the Philippines

The World Bank in East Asia and Pacific

Follow the World Bank on Facebook

Follow the World Bank on Twitter

This site uses cookies to optimize functionality and give you the best possible experience. If you continue to navigate this website beyond this page, cookies will be placed on your browser. To learn more about cookies, click here .

- Top Stories

- Stock Market

- BUYING RATES

- FOREIGN INTEREST RATES

- Philippine Mutual Funds

- Leaders and Laggards

- Stock Quotes

- Stock Markets Summary

- Non-BSP Convertible Currencies

- BSP Convertible Currencies

- US Commodity futures

- Infographics

- B-Side Podcasts

- Agribusiness

- Arts & Leisure

- Special Features

- Special Reports

- BW Launchpad

- Editors' Picks

Global Warming: Frontline Philippines

Vantage Point

By Luis V. Teodoro

A s this piece was being written, the number of dead, missing, and injured and the toll on agriculture and infrastructure were still rising in Oriental Mindoro, Camarines Norte, Samar, Romblon, and other provinces where almost every barangay had been devastated by days of torrential rain.

No super typhoon was responsible, and neither is it the rainy season. Low pressure areas (LPAs) and the clash between hot and cold air have nevertheless been bringing floods to parts of southern Luzon, the Visayas, and Mindanao.

No country can long endure the human and material costs of the unpredictability and intensifying violence of the weather disturbances that climate change is generating across the planet — and in the Philippines they have made even more problematic the poverty and destruction that bureaucratic bungling and corruption has inflicted on millions of Filipinos.

The increasing number of the super typhoons that have been smashing into the Philippines, the unseasonal weather, the tornados, cyclones, droughts, floods, and exceptionally cold winters in other countries are among the many indications that time is running out and the hour of what could be the end of the human race approaching.

Among the most vulnerable countries to global warming is the Philippines: it is a frontliner in the seemingly global rush to extinction. Not only is it in the path of typhoons; it also sits on the Pacific “ring of fire” that powers earthquakes and volcanic eruptions. The deaths, the injuries, and the billions in property losses and livelihood from these disasters contribute to the poverty and want that already define the lives of millions of Filipinos.

Even without global warming, crafting and implementing a national disaster mitigation program has always been among the responsibilities of any Philippine administration. To the need for such a program has been added the necessity of incorporating in it provisions that will give the Philippines a fighting chance in surviving the onslaught of the weather anomalies climate change is generating.

But the National Government has been remiss in the making of such a program. Local government units (LGUs) complain not only of the lack of funds for the dredging of creeks and rivers and for resident relocation, but also of the erratic and even non-existent reach of the food and other aid communities need during the current weather crisis.

No sense of urgency drove the previous administration to remedy the situation. Then President Rodrigo Duterte even had an excuse for his limited response to the victims of the super typhoons that ravaged the country, despite the billions of pesos budgeted for that purpose. Instead, he promised in 2021 to look for the funds needed to rehabilitate devastated communities. Hence it was mostly from foreign sources — the UN, Japan, the US and other countries — that those affected obtained some relief.

Unfortunately, neither has there been any sign that the Marcos II regime is seriously thinking of addressing the problems that climate change is aggravating, such as the decline in agricultural productivity and the losses in lives and property in the affected communities. Mr. Marcos is instead focused on regaling the rest of the world with his administration’s supposedly great economic achievements, the vast investment opportunities in the Philippines, and his sudden mastery of the complex realities of the country’s foreign relations.

Not all the 20 or so weather disturbances that enter the Philippine Area of Responsibility (PAR) annually make landfall. But even those that do not can still bring rains, flash floods, and landslides. Depending on the power of their winds, the rain they bring, and the number of places they ravage, those that do make landfall can be even more devastating. And as recent events are demonstrating, the rains from LPAs alone can bring unprecedented disasters to the most vulnerable communities.

These phenomena are likely to intensify, and they affect the entire country and the lives of everyone in it. Social and natural scientists have described the climate crisis as a threat worse than nuclear war to the future of organized human life. But little is being done in the Philippines by either local governments or their national counterpart to protect the most vulnerable communities from flooding and storm surges. Rather than pro-active risk-reduction, which global warming has made more urgent, government response to disasters has been mostly reactive and limited to moving those affected to improvised evacuation centers, distributing instant noodles and sardines, and urging them to relocate.

But neither the incentives, the means, nor the opportunity to relocate have been provided the residents of coastal communities, who are in perennial danger from storm surges, and those who live in places below average flood levels. Some do manage to evacuate when typhoons batter their communities. But they return to the same sites to repair or rebuild damaged or destroyed homes, and hence are in constant danger of losing their lives and property when the next typhoon comes.

Relocating can prevent the repetition of the same woes. But without access to livelihood sources, water supplies, and electric power in places they are unfamiliar with, few families are willing to risk it. And yet the millions still being spent on maintaining such frivolities as the Department of Environment and Natural Resources’ (DENR) Dolomite Folly could be better spent on, among others, providing endangered communities the incentives that could help reduce the annual human and material costs of weather disturbances.

Together with such a program, a national plan could include the construction of a system of levees along the country’s most vulnerable coastal areas. A network of permanent evacuation centers could also be constructed, and stricter engineering standards implemented in the construction of roads, bridges, buildings, homes, and other infrastructure.

Global warming has been attributed to, among others, the carbon dioxide and methane gasses that are released into the atmosphere by industries and the burning of fossil fuels of such countries as the United States, the European countries, Japan, and China. Reducing such emissions to stop the rise in global temperatures is therefore mostly those countries’ responsibility. They have to forge and implement working protocols to regulate their environmentally destructive industries and reduce the amount of pollutants from other sources discharged into the atmosphere. Among the existing conventions for that purpose are the Paris Climate Agreement and the Kyoto Protocol, but their implementation is hampered by the industrialized countries’ resistance to regulating the industries responsible.

Although not among those countries, the Philippines could make the use of alternative sources of power generation mandatory, together with the strict implementation of the Clean Air Act (RA 8749). It can also contribute to the global imperative of halting the threat by adopting a national plan devised by scientists, environmentalists, and other experts to ease the impact of disasters on the most endangered sectors of the population.

Ecologists and environmental activists have long been alerting the planet on the perils of climate change, but the governments of most countries, among them that of the Philippines, have not paid much attention to them. The “inconvenient truth,” as former US Vice-President Al Gore noted over two decades ago, is that not only national plans are needed but also a truly global program to address climate change.

Mr. Marcos could use his new-found skills in international relations to convince the rest of the world of that need. But rather than just globe-trotting, he could also craft and implement the policies that can combat the ravages of global warming here, in frontline Philippines.

Luis V. Teodoro is on Facebook and Twitter (@luisteodoro).

www.luisteodoro.com

RELATED ARTICLES MORE FROM AUTHOR

Jobless rate slips to 2-month low

ADB cuts Philippine growth outlook to 6%

Trade deficit narrows to $3.65B in Feb.

House OK’s on 2nd reading Charter change through hybrid con-con

Comelec assures it will be ready for the polls despite hitches, upskilling needed as pandemic changes operating environment.

Climate Change Impacts on Philippine Communities: An Overview of the Current Literature and Policies

Introduction

The Philippines is one of the countries most vulnerable to climate change in the world. An island nation which is heavily exposed to extreme weather events, the Philippines has little adaptive capacity. This article will begin by exploring the current and anticipated climatic changes as based on the most recent report released by the International Panel for Climate Change in 2014. After this, the economy of the Philippines is discussed; the main industries of which are agriculture, mining, and services (including tourism, business process outsourcing, and remittances from overseas Filipino workers). The primary industries of the Philippines, namely agriculture and mining, have varying yet significant detrimental impacts on the environment, these are explored, as are the risks of both these industries and macro scale anticipated climate change impacts to society. After this, current or proposed policies to improve the status quo of the mining and agriculture sectors are explored and critiqued. Following this, there is a discussion of the groups in the Philippine society who are most vulnerable to climate change and adverse industry impacts. A larger exploration of lower economic groups, particularly agriculture-based households is undertaken. The impacts on these marginalized groups are contextualized as forms of violence and reviewed in line with the themes of sustainable development and positive peace.

Overview of the Philippines

Geography and climate.

The Philippines is an archipelago with over 7500 islands comprising approximately 30 million hectares, nestled between the Philippines Sea, the South China Sea, and the Celebes Sea. The islands of the Philippines are grouped into three regions: Mindanao (10.2 million hectares), Visayas (5.7 million hectares), and Luzon (14.1 million hectares) where the capital, Manila, is located. The Philippines is a collection of half-submerged mountains, which were pushed up as a result of the subduction zone of the collision of the Eurasian and the Philippine plates. This subduction zone makes the Philippines prone to earthquakes and volcanic activity. The climate is tropical, with an average humidity of 80% and an annual rainfall of 80-450cm. 1 Two of the regions, Luzon and Visayas, are affected by typhoons each year, which account for half of their annual rainfall.

Demographics

Of the 102.8 million people who live in the Philippines, 44.2% live in urban centers, while the remaining 55.8% live in rural areas. 2 According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the current per capita GDP is 12,430 Philippine Pesos, an increase of 6.7% over the previous year. 3 Poverty has also dropped to 21.6% over the past year with unemployment dropping to a historic low of 4.7%. However, underemployment is still steady and significant at 18%. Underemployment reflects the number of workers who are working but would like to work more hours than they receive. This high value reflects the prevalence of informality, workplace corruption, and other job-related concerns. 4 Poverty and underemployment are directly related to undernourishment, at a rate of 13.8% of the population. 5 These are projected to worsen with the increased income inequality. 6

Review of Climate Change and Projected Impacts

According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) climate change is defined as the change in the usual weather found in a place; specifically, it refers to the levels of precipitation or expected temperature of a month or season. This is a long-term alteration in the expected climate which usually takes hundreds or even millions of years. 7 The basis for the review of climate change impacts is taken from the International Panel of Climate Change (IPCC) fifth assessment report (AR5) which was released in 2014. The IPCC was established in 1988 by the United Nations Environmental Programme (UNEP) and the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) to provide unbiased and clear scientific research on the current state of knowledge in climate change and its potential environmental and socio-economic impacts. 8

This review acknowledges climate change is a global phenomenon and one which affects all regions and sub-regions differently, however, it is outside the capacity of this paper to review the global impacts of climate change, the scope of this paper is limited to South-East Asia, most particularly to the Philippines. This section aims to discuss only the changes in climate resulting from global increases of atmospheric carbon. Climate change is anticipated to have many impacts on the status quo of the Philippines.

Temperature rise

As it stands, an increase of more than 3°C is expected throughout Southeast Asia. 9 This temperature increase will be reflected in ocean temperatures, particularly at the surface. 10 Not only will the temperature increase affect the oceans, but it will also affect terrestrial ecosystems in several ways. Temperature is quantitatively the most important driver of changes in fire frequency in terrestrial ecosystems. 11 It is not fully understood how this relationship works, however analysis of the past 21,000 years shows there is a positive relationship between temperature and fire frequency, more so than any other parameter. In addition to increased fire frequency risks, precipitation patterns will continue to be heavily impacted by the increased temperatures.

Precipitation

Overall, rainfall has only increased by 22mm per decade over Southeast Asia, which is not a significant increase; however the regularity of the rainfall has altered with 10mm of the measured increase being attributed to extreme rain days. This increase is predicted to continue over the coming decades. 12 The decreased regularity of precipitation has a two-fold consequence; firstly, longer and more intensive drought periods, and secondly, heavier rainfall once the droughts end. One part of the altered precipitation pattern is the increased level of precipitation occurring with tropical cyclones. Aside from the increased rainfall with each cyclone, there is less confidence in the knowledge surrounding the increase in frequency or intensity of these cyclones. Another weather pattern where precipitation will play a role is the monsoon season. Eighty-five percent of future projections show an increase in mean precipitation during monsoons, while more than 95% show an increase in heavy precipitation events. 13

Fresh Water

Although the parameters to measure fresh water quality and quantity are heavily influenced by human activities, there is evidence to believe that climate change impacts not only the quantity of freshwater but also the quality. Delpla et al 14 showed that warming and extreme events were likely to modify the physical-chemical parameters, micropollutants and biological parameters of the water. 15 The physico-chemical parameters include measurements such as temperature, pH, dissolved oxygen, and total dissolved solids. Micropollutants are bioactive, non-biodegradable substances such as radioactive or biologically harmful metals (including mercury, lead, and arsenic), pesticides, or pharmaceuticals, and biological parameters include the presence and volume of species such as algae and phytoplankton as well other microorganisms. Higher air temperatures increase evapotranspiration; when this occurs in tandem with increased frequency and intensity of droughts, then surface water quantity will be decreased. This can then increase the concentration of many of the physico-chemical parameters, micropollutants, and biological parameters listed above.

As previously mentioned, the ocean is anticipated to increase in temperature, particularly at the surface. 16 The current state of warming has been implicated in the northward expansion of tropical and subtropical macroalgae and toxic phytoplankton. 17 This northward shift of species is anticipated to alter the marine ecosystems and provide new challenges for the species which have historically been present in and around the Philippines. With current predictions, the increased temperature combined with ocean acidification is expected to result in significant declines in coral-dominated reefs and other calcified marine species, such as algae, molluscs, and larval echinoderms. 18 Current trends in sea level rise are expected to be exceeded by the future predictions. 19 This, in combination with cyclone intensification, will likely increase coastal flooding, erosion, and saltwater intrusion into surface and groundwaters. 20 Unless they are provided with enough fresh sediment or are allowed to move inland, beaches, mangroves, saltmarshes and seagrass beds will decline also, and these declines will exacerbate wave damage. 21 , 22 , 23 , 24

Philippine Industries: Agriculture

Agriculture – including forestry, fishing, and hunting – is one of the biggest sectors of the Philippine economy, accounting for 9.7% of the GDP 25 and employing 28% of the total workforce. The sizes of the agricultural ventures vary drastically, including a significant number of subsistence farmers as represented by the large proportion of the population who live rurally, and commercial ventures from multinational corporations. The large commercial agriculture ventures hold significant swathes of land and grow vast quantities of produce. In the Philippines the main crops are sugar, rice, and coconuts, each year producing hundreds of thousands of tons of each for export. 26 There is a drastic difference between the commercial ventures and the subsistence farmers in terms of yield, intensity of farming practice, and exports. It should be noted that fishing and farming are the two sectors with the highest incidences of poverty, 27 which I will discuss in more depth below.

Services are a highly profitable and diverse sector for the Philippines, and one which has expanded greatly over the past few years. Tourism is included in the services sector and provided 8.6% of the nation’s GDP in 2016, up 0.4% from the previous year. 28 Another major part of the services sector is the rapidly growing business process outsourcing, where call centers and other such infrastructure are exported to places like the Philippines to exploit their lower labor costs. In the Philippines, this employs over 1.3 million people. A last significant part of the services industry –which isn’t always accounted for but is nevertheless a crucial source of income for many families – are the remittances sent home from overseas Filipino workers (OFW). In the year 2016 there were 2.2 million OFW spread globally working in a large variety of roles. The remittances these workers returned to the Philippine economy added 146,029 million Philippine pesos, or roughly USD$2.78 billion in the year 2016. 29

There is great variety of industries in the Philippines, including vast manufacturing outputs. These range from one of the largest shipbuilding industries in the world, to a growing automotive and aerospace production. Construction is also a major employer as the country develops its economy and its population continues to grow, requiring more infrastructure. One of the main and more controversial industries of the Philippines is the mining and extraction industry. The Philippines has significant reserves of gold, nickel, copper, chromite, silver, coal, sulphur, and gypsum. While there has been significant debate over the legality of overseas mine ownership and mining procedures (as will be discussed later) the industry has continued to grow over the past year. The main contributors to the 8.8% expansion were stone quarrying, clay, and sandpits which grew by 17.7%, gold which grew by 16.5%, and crude oil, natural gas and condensate which grew by 7.4%. 30

Impacts of Industries on Environment

The impacts of many industries on the local environment make detecting and disentangling the impacts of climate change from the surrounding pressures very challenging, which is also reflected in the literature. 31

Many industries require access to fresh water, as a result, overexploitation of groundwater systems can result in land subsidence. When this is combined with the climate change driven impacts of coastal inundation and sea level rise, there is increased risks of worsened water quality. 32 Mining, in particular, poses a significant risk of water contamination. Mine tailings – the excess earth and chemicals used to obtain the target metal – are often permanently stored in large lakes or used to create structures such as dam walls and piers. However, if the tailings are not treated or sealed correctly, poisonous contaminants can leachate out and pollute the water surrounding them. As mining is such a prevalent industry in the Philippines, and with choices being made to economize the handling of these tailings (often at the expense of long-lasting safety), there have been examples of significant water contamination, including from the Palawan Quicksilver mine, 33 along the Naboc River area near Mindanao, 34 and in the water supplies to the villages of Sta. Lourdes and Tagburos. 35

Deforestation

Between 1990 and 2005, the Philippines lost a third of its primary forest cover. 36 This was due to a number of factors, one of which is the conversion of forest lands to promote growth and development. This is combined with high levels of poverty and landlessness in rural and urban populations, causing poorer families to move into less farmable uplands. This poverty is compounded by uncertain land rights, resulting in lack of long term investment in land and over-exploitation of its resources for short-term economic benefits. There is also a lack of policy and improper pricing of the land which results in poorly managed forestry practises, resulting in high capital intensity, low employment generation, and low investments in forest regeneration and protection.

There is an alarming feedback from forest cover to rainfall. Of course, without rain there is very little sustainable agriculture, including forestry. However, when forest cover is removed, it has been anticipated that rainfall patterns will also significantly change. 37 Consider that 25-56% of all rainfall in highly forested regions can be recycled in the ecosystem as tropical trees extract water from the soil and, through evapotranspiration, release it into the atmosphere, thus inducing rainfall. With the high rates of deforestation in the Philippines, we can assume that historic rainfall patterns will be significantly different in the future, not only through the broader forces of climate change, but also on a micro scale as a result of deforestation.