What the Longest Study on Human Happiness Found Is the Key to a Good Life

The Harvard Study of Adult Development has established a strong correlation between deep relationships and well-being. The question is, how does a person nurture those deep relationships?

This article was featured in One Story to Read Today, a newsletter in which our editors recommend a single must-read from The Atlantic , Monday through Friday. Sign up for it here.

T urn your mind for a moment to a friend or family member you cherish but don’t spend as much time with as you would like. This needn’t be your most significant relationship, just someone who makes you feel energized when you’re with them, and whom you’d like to see more regularly.

How often do you see that person? Every day? Once a month? Once a year? Do the math and project how many hours annually you spend with them. Write this number down and hang on to it.

For us, Bob and Marc, though we work closely together and meet every week by phone or video call, we see each other in person for only a total of about two days (48 hours) every year.

How does this add up for the coming years? Bob is 71 years old. Marc is 60. Let’s be (very) generous and say we will both be around to celebrate Bob’s 100th birthday. At two days a year for 29 years, that’s 58 days that we have left to spend together in our lifetimes.

Fifty-eight out of 10,585 days.

Of course, this is assuming a lot of good fortune, and the real number is almost certainly going to be lower.

Since 1938, the Harvard Study of Adult Development has been investigating what makes people flourish. After starting with 724 participants—boys from disadvantaged and troubled families in Boston, and Harvard undergraduates—the study incorporated the spouses of the original men and, more recently, more than 1,300 descendants of the initial group. Researchers periodically interview participants, ask them to fill out questionnaires, and collect information about their physical health. As the study’s director (Bob) and associate director (Marc), we’ve been able to watch participants fall in and out of relationships, find success and failure at their jobs, become mothers and fathers. It’s the longest in-depth longitudinal study on human life ever done, and it’s brought us to a simple and profound conclusion: Good relationships lead to health and happiness. The trick is that those relationships must be nurtured.

From the June 2009 issue: What makes us happy?

We don’t always put our relationships first. Consider the fact that the average American in 2018 spent 11 hours every day on solitary activities such as watching television and listening to the radio. Spending 58 days over 29 years with a friend is infinitesimal compared with the 4,851 days that Americans will spend interacting with media during that same time period. Distractions are hard to avoid.

Thinking about these numbers can help us put our own relationships in perspective. Try figuring out how much time you spend with a good friend or family member. We don’t have to spend every hour with our friends, and some relationships work because they’re exercised sparingly. But nearly all of us have people in our lives whom we’d like to see more. Are you spending time with the people you most care about? Is there a relationship in your life that would benefit both of you if you could spend more time together? Many of these are untapped resources, waiting for us to put them to use. And, enriching these relationships can in turn nourish our minds and bodies.

Y ou don’t have to examine scientific findings to recognize that relationships affect you physically. All you have to do is notice the invigoration you feel when you believe that someone has really understood you during a good conversation, or the tension and distress you feel after an argument, or how little sleep you get during a period of romantic strife.

In this sense, having healthy, fulfilling relationships is its own kind of fitness—social fitness—and like physical fitness, it takes work to maintain. Unlike stepping on the scale, taking a quick look in the mirror, or getting readouts for blood pressure and cholesterol, assessing our social fitness requires a bit more sustained self-reflection. It requires stepping back from the crush of modern life, taking stock of our relationships, and being honest with ourselves about where we’re devoting our time and whether we are tending to the connections that help us thrive. Finding the time for this type of reflection can be hard, and sometimes it’s uncomfortable. But it can yield enormous benefits.

Many of our Harvard Study participants have told us that filling out questionnaires every two years and being interviewed regularly have given them a welcome perspective on their life and relationships. We ask them to really think about themselves and the people they love, and that process of self-reflection helps some of them.

Read: 10 practical ways to improve happiness

This is a practice that could help anyone. Looking in the mirror and thinking honestly about where your life stands is a first step in trying to live a good life. Noticing where you are can help put into relief where you would like to be. Having some reservations about this kind of self-reflection is understandable. Our study participants were not always keen on filling out our questionnaires, or eager to consider the larger picture of their life. Some would skip difficult questions or leave entire pages blank, and some would just not return certain surveys. Some even wrote comments in the margins of their questionnaires about what they thought of our requests. “What kinds of questions are these!?” is a response we received occasionally, often from participants who preferred not to think about difficulties in their life. The experiences of the people who skipped questions or entire questionnaires were also important, though—they were just as crucial in understanding adult development as the experiences of people eager to share. A lot of useful data and gems of experience were buried in the shadowed corners of their lives. We just had to go through a little extra effort to excavate them.

One of these people was a man we’ll call Sterling Ainsley. (We are using a pseudonym to protect his confidentiality as a study participant.)

S terling Ainsley was a hopeful guy. He graduated from Harvard in the 1940s and then served in World War II. After he left the service, he got a job as a scientist and retired in his 60s. When asked to describe his philosophy for getting through hard times, he said, “You try not to let life get to you. You remember your victories and take a positive attitude.”

The year was 1986. George Vaillant, the then-director of the study, was on a long interview trek, driving through the Rocky Mountains to visit the study’s participants who lived in Colorado, Utah, Idaho, and Montana. Sterling had not returned the most recent survey, and there was some catching up to do. He met Vaillant at a hotel to give him a ride to the diner where Sterling wanted to do his scheduled interview. When Vaillant buckled himself into the passenger seat of Sterling’s car, the seat belt left a stripe of dust across his chest. “I was left to wonder,” he wrote, “the last time somebody had used it.”

Sterling was technically married, but his wife lived far away, and they hadn’t slept in the same room in years. They spoke only every few months.

Read: The six forces that fuel friendship

When asked why they had not gotten a divorce, he said, “I wouldn’t want to do that to the children,” even though his kids were grown and had children of their own. Sterling was proud of his kids and beamed when he spoke of them, saying they were the most important thing in his life. But he rarely saw them and seemed to prefer to keep his relationships with them thriving mostly in his imagination. Vaillant noted that Sterling seemed to be using optimism to push away some of his fears and avoid challenges in his life. Putting a positive spin on every matter and then pushing it out of his mind made it possible for him to believe that nothing was wrong, he was fine, he was happy, his kids didn’t need him.

He didn’t travel to see his son’s new home abroad, because he didn’t “want to be a burden”—even though he’d been learning a new language to prepare for the trip. He had another child who lived closer, but he hadn’t visited in more than a year. He didn’t have a relationship with his grandchildren, and he wasn’t in contact with any friends.

When asked about his older sister, Sterling seemed startled. “My sister?” he said.

Yes, the sister he had told the study so much about when he was younger.

Sterling thought about it for a long time, and then told Vaillant that it must have been decades since he last spoke with her. A frightened expression came over his face. “Would she still be living?” he said.

Sterling tried not to think about his relationships, and he was even less inclined to talk about them. This is a common experience. We don’t always know why we do things or why we don’t do things, and we may not understand what is holding us at a distance from the people in our life. Taking some time to look in the mirror can help. Sometimes there are needs inside of us that are looking for a voice, a way to get out. They might be things that we have never seen or articulated to ourselves.

This seemed to be the case with Sterling. Asked how he spent his evenings, he said he spent time with an elderly woman who lived in a nearby trailer. Each night he would walk over, and they’d watch TV and talk. Eventually she would fall asleep, and he would help her into bed and wash her dishes and close the shades before walking home. She was the closest thing he had to a confidant.

“I don’t know what I’ll do if she dies,” he said.

Listen to Robert Waldinger in conversation with Arthur Brooks and Rebecca Rashid on "How to Build a Happy Life":

L oneliness has a physical effect on the body. It can render people more sensitive to pain, suppress their immune system, diminish brain function, and disrupt sleep, which in turn can make an already lonely person even more tired and irritable. Research has found that, for older adults, loneliness is far more dangerous than obesity. Ongoing loneliness raises a person’s odds of death by 26 percent in any given year. A study in the U.K., the Environmental Risk (E-Risk) Longitudinal Twin Study, recently reported on the connections between loneliness and poorer health and self-care in young adults. This ongoing study includes more than 2,200 people born in England and Wales in 1994 and 1995. When they were 18, the researchers asked them how lonely they were. Those who reported being lonelier had a greater chance of facing mental-health issues, partaking in unsafe physical-health behaviors, and coping with stress in negative ways. Add to this the fact that a tide of loneliness is flooding through modern societies, and we have a serious problem. Recent stats should make us take notice.

In a study conducted online that sampled 55,000 respondents from across the world, one out of every three people of all ages reported that they often feel lonely. Among these, the loneliest group were 16-to-24-year-olds, 40 percent of whom reported feeling lonely “often or very often.” In the U.K., the economic cost of this loneliness—because lonely people are less productive and more prone to employment turnover—is estimated at more than £2.5 billion (about $3.1 billion) annually and helped lead to the establishment of a U.K. Ministry of Loneliness.

Read: Why do we look down on lonely people?

In Japan, 32 percent of adults expected to feel lonely most of the time during 2020. In the United States, a 2019 study suggested that three out of four adults felt moderate to high levels of loneliness. As of this writing, the long-term effects of the coronavirus pandemic, which separated us from one another on a massive scale and left many feeling more isolated than ever, are still being studied.

Alleviating this epidemic of loneliness is difficult because what makes one person feel lonely might have no effect on someone else. We can’t rely entirely on easily observed indicators such as whether or not one lives alone, because loneliness is a subjective experience. One person might have a significant other and too many friends to count and yet feel lonely, while another person might live alone and have a few close contacts and yet feel very connected. The objective facts of a person’s life are not enough to explain why someone is lonely. Regardless of your race or class or gender, the feeling resides in the difference between the kind of social contact you want and the social contact you actually have.

I t never hurts —especially if you’ve been feeling low—to take a minute to reflect on how your relationships are faring and what you wish could be different about them. If you’re the scheduling type, you could make it a regular thing; perhaps every year on New Year’s Day or the morning of your birthday, take a few moments to draw up your current social universe, and consider what you’re receiving, what you’re giving, and where you would like to be in another year. You could keep your chart or relationships assessment in a special place, so you know where to look the next time you want to peek at it to see how things have changed.

If nothing else, doing this reminds us of what’s most important. Repeatedly, when the participants in our study reached old age, they would make a point to say that what they treasured most were their relationships. Sterling Ainsley himself made that point. He loved his older sister deeply—but he lost touch with her. Some of his fondest memories were of his friends—whom he never contacted. There was nothing he cared more about than his children—whom he rarely saw. From the outside it might look like he didn’t care. That was not the case. Sterling was quite emotional in his recounting of his most cherished relationships, and his reluctance to answer certain study questions was clearly connected to the pain that keeping his distance had caused him over the years. Sterling never sat down to really think about how he might conduct his relationships or what he might do to properly care for the people he loved most.

Sterling’s life reminds us of the fragility of our connections, and it echoes the lessons of science: Relationships keep us happier and healthier throughout our life spans. We neglect our connections with others at our peril. Investing in our social fitness is possible each day, each week of our lives. Even small investments today in our relationships with others can create long-term ripples of well-being.

This article is adapted from Robert Waldinger and Marc Schulz’s new book, The Good Life: Lessons From the World’s Longest Scientific Study of Happiness .

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.

- Skip to main content

- Keyboard shortcuts for audio player

Consider This from NPR

- LISTEN & FOLLOW

- Apple Podcasts

- Google Podcasts

- Amazon Music

Your support helps make our show possible and unlocks access to our sponsor-free feed.

The Key To Happiness, According To A Decades-Long Study

Sending a text to a friend can bring a smile to your face. Now, research suggests it could also help bring long-term health benefits. guoya/Getty Images hide caption

Sending a text to a friend can bring a smile to your face. Now, research suggests it could also help bring long-term health benefits.

If you could change one thing in your life to become a happier person — like your income, a job, your relationships or your health — what would make the biggest difference? That's the question Harvard psychiatrist Dr. Robert Waldinger has been attempting to answer through decades of research. He's the director of "the world's longest-running scientific study of happiness," and he spoke with Ari Shapiro about the factor that appears to make the biggest difference in people's lives. Waldinger is a co-author of The Good Life: Lessons from the world's longest scientific study of happiness . In participating regions, you'll also hear a local news segment to help you make sense of what's going on in your community. Email us at [email protected] .

This episode was produced by Lee Hale and Megan Lim. It was edited by William Troop and Christopher Intagliata. Our executive producer is Sami Yenigun.

Featured Topics

Featured series.

A series of random questions answered by Harvard experts.

Explore the Gazette

Read the latest.

Exercise cuts heart disease risk in part by lowering stress, study finds

How to realize immense promise of gene editing

Women rarely die from heart problems, right? Ask Paula.

Good genes are nice, but joy is better.

Harvard Staff Writer

Harvard study, almost 80 years old, has proved that embracing community helps us live longer, and be happier

Part of the Tackling Issues of Aging series

A series on how Harvard researchers are tackling the problematic issues of aging.

W hen scientists began tracking the health of 268 Harvard sophomores in 1938 during the Great Depression, they hoped the longitudinal study would reveal clues to leading healthy and happy lives.

They got more than they wanted.

After following the surviving Crimson men for nearly 80 years as part of the Harvard Study of Adult Development , one of the world’s longest studies of adult life, researchers have collected a cornucopia of data on their physical and mental health.

Of the original Harvard cohort recruited as part of the Grant Study, only 19 are still alive, all in their mid-90s. Among the original recruits were eventual President John F. Kennedy and longtime Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee. (Women weren’t in the original study because the College was still all male.)

In addition, scientists eventually expanded their research to include the men’s offspring, who now number 1,300 and are in their 50s and 60s, to find out how early-life experiences affect health and aging over time. Some participants went on to become successful businessmen, doctors, lawyers, and others ended up as schizophrenics or alcoholics, but not on inevitable tracks.

“Loneliness kills. It’s as powerful as smoking or alcoholism.” Robert Waldinger, psychiatrist, Massachusetts General Hospital

During the intervening decades, the control groups have expanded. In the 1970s, 456 Boston inner-city residents were enlisted as part of the Glueck Study, and 40 of them are still alive. More than a decade ago, researchers began including wives in the Grant and Glueck studies.

Over the years, researchers have studied the participants’ health trajectories and their broader lives, including their triumphs and failures in careers and marriage, and the finding have produced startling lessons, and not only for the researchers.

“The surprising finding is that our relationships and how happy we are in our relationships has a powerful influence on our health,” said Robert Waldinger , director of the study, a psychiatrist at Massachusetts General Hospital and a professor of psychiatry at Harvard Medical School . “Taking care of your body is important, but tending to your relationships is a form of self-care too. That, I think, is the revelation.”

Close relationships, more than money or fame, are what keep people happy throughout their lives, the study revealed. Those ties protect people from life’s discontents, help to delay mental and physical decline, and are better predictors of long and happy lives than social class, IQ, or even genes. That finding proved true across the board among both the Harvard men and the inner-city participants.

“The people who were the most satisfied in their relationships at age 50 were the healthiest at age 80,” said Robert Waldinger with his wife Jennifer Stone.

Rose Lincoln/Harvard Staff Photographer

The long-term research has received funding from private foundations, but has been financed largely by grants from the National Institutes of Health, first through the National Institute of Mental Health, and more recently through the National Institute on Aging.

Researchers who have pored through data, including vast medical records and hundreds of in-person interviews and questionnaires, found a strong correlation between men’s flourishing lives and their relationships with family, friends, and community. Several studies found that people’s level of satisfaction with their relationships at age 50 was a better predictor of physical health than their cholesterol levels were.

“When we gathered together everything we knew about them about at age 50, it wasn’t their middle-age cholesterol levels that predicted how they were going to grow old,” said Waldinger in a popular TED Talk . “It was how satisfied they were in their relationships. The people who were the most satisfied in their relationships at age 50 were the healthiest at age 80.”

He recorded his TED talk, titled “What Makes a Good Life? Lessons from the Longest Study on Happiness,” in 2015, and it has been viewed 13,000,000 times.

The researchers also found that marital satisfaction has a protective effect on people’s mental health. Part of a study found that people who had happy marriages in their 80s reported that their moods didn’t suffer even on the days when they had more physical pain. Those who had unhappy marriages felt both more emotional and physical pain.

Those who kept warm relationships got to live longer and happier, said Waldinger, and the loners often died earlier. “Loneliness kills,” he said. “It’s as powerful as smoking or alcoholism.”

According to the study, those who lived longer and enjoyed sound health avoided smoking and alcohol in excess. Researchers also found that those with strong social support experienced less mental deterioration as they aged.

In part of a recent study , researchers found that women who felt securely attached to their partners were less depressed and more happy in their relationships two-and-a-half years later, and also had better memory functions than those with frequent marital conflicts.

“When the study began, nobody cared about empathy or attachment. But the key to healthy aging is relationships, relationships, relationships.” George Vaillant, psychiatrist

“Good relationships don’t just protect our bodies; they protect our brains,” said Waldinger in his TED talk. “And those good relationships, they don’t have to be smooth all the time. Some of our octogenarian couples could bicker with each other day in and day out, but as long as they felt that they could really count on the other when the going got tough, those arguments didn’t take a toll on their memories.”

Since aging starts at birth, people should start taking care of themselves at every stage of life, the researchers say.

“Aging is a continuous process,” Waldinger said. “You can see how people can start to differ in their health trajectory in their 30s, so that by taking good care of yourself early in life you can set yourself on a better course for aging. The best advice I can give is ‘Take care of your body as though you were going to need it for 100 years,’ because you might.”

The study, like its remaining original subjects, has had a long life, spanning four directors, whose tenures reflected their medical interests and views of the time.

Under the first director, Clark Heath, who stayed from 1938 until 1954, the study mirrored the era’s dominant view of genetics and biological determinism. Early researchers believed that physical constitution, intellectual ability, and personality traits determined adult development. They made detailed anthropometric measurements of skulls, brow bridges, and moles, wrote in-depth notes on the functioning of major organs, examined brain activity through electroencephalograms, and even analyzed the men’s handwriting.

Now, researchers draw men’s blood for DNA testing and put them into MRI scanners to examine organs and tissues in their bodies, procedures that would have sounded like science fiction back in 1938. In that sense, the study itself represents a history of the changes that life brings.

6 factors predicting healthy aging According to George Vaillant’s book “Aging Well,” from observations of Harvard men in long-term aging study

Physically active.

Absence of alcohol abuse and smoking

Having mature mechanisms to cope with life’s ups and downs

Healthy weight

Stable marriage.

Psychiatrist George Vaillant, who joined the team as a researcher in 1966, led the study from 1972 until 2004. Trained as a psychoanalyst, Vaillant emphasized the role of relationships, and came to recognize the crucial role they played in people living long and pleasant lives.

In a book called “Aging Well,” Vaillant wrote that six factors predicted healthy aging for the Harvard men: physical activity, absence of alcohol abuse and smoking, having mature mechanisms to cope with life’s ups and downs, and enjoying both a healthy weight and a stable marriage. For the inner-city men, education was an additional factor. “The more education the inner city men obtained,” wrote Vaillant, “the more likely they were to stop smoking, eat sensibly, and use alcohol in moderation.”

Vaillant’s research highlighted the role of these protective factors in healthy aging. The more factors the subjects had in place, the better the odds they had for longer, happier lives.

“When the study began, nobody cared about empathy or attachment,” said Vaillant. “But the key to healthy aging is relationships, relationships, relationships.”

“We want to find out how it is that a difficult childhood reaches across decades to break down the body in middle age and later.” Robert Waldinger

The study showed that the role of genetics and long-lived ancestors proved less important to longevity than the level of satisfaction with relationships in midlife, now recognized as a good predictor of healthy aging. The research also debunked the idea that people’s personalities “set like plaster” by age 30 and cannot be changed.

“Those who were clearly train wrecks when they were in their 20s or 25s turned out to be wonderful octogenarians,” he said. “On the other hand, alcoholism and major depression could take people who started life as stars and leave them at the end of their lives as train wrecks.”

The study’s fourth director, Waldinger has expanded research to the wives and children of the original men. That is the second-generation study, and Waldinger hopes to expand it into the third and fourth generations. “It will probably never be replicated,” he said of the lengthy research, adding that there is yet more to learn.

“We’re trying to see how people manage stress, whether their bodies are in a sort of chronic ‘fight or flight’ mode,” Waldinger said. “We want to find out how it is that a difficult childhood reaches across decades to break down the body in middle age and later.”

Lara Tang ’18, a human and evolutionary biology concentrator who recently joined the team as a research assistant, relishes the opportunity to help find some of those answers. She joined the effort after coming across Waldinger’s TED talk in one of her classes.

“That motivated me to do more research on adult development,” said Tang. “I want to see how childhood experiences affect developments of physical health, mental health, and happiness later in life.”

Asked what lessons he has learned from the study, Waldinger, who is a Zen priest, said he practices meditation daily and invests time and energy in his relationships, more than before.

“It’s easy to get isolated, to get caught up in work and not remembering, ‘Oh, I haven’t seen these friends in a long time,’ ” Waldinger said. “So I try to pay more attention to my relationships than I used to.”

Share this article

Also in this series:.

Probe of Alzheimer’s follows paths of infection

Starting with microbes, Harvard-MGH researchers outline a devastating chain of events

To age better, eat better

Much of life is beyond our control, but dining smartly can help us live healthier, longer

The balance in healthy aging

To grow old well requires minimizing accidents, such as falling, as well as ailments

How old can we get? It might be written in stem cells

No clock, no crystal ball, but lots of excitement — and ambition — among Harvard scientists

Plotting the demise of Alzheimer’s

New study is major test for power of early action

You might like

Benefits nearly double for people with depression

Nobel-winning CRISPR pioneer says approval of revolutionary sickle-cell therapy shows need for more efficient, less expensive process

New book traces how medical establishment’s sexism, focus on men over centuries continues to endanger women’s health, lives

So what exactly makes Taylor Swift so great?

Experts weigh in on pop superstar's cultural and financial impact as her tours and albums continue to break records.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 20 July 2023

A systematic review of the strength of evidence for the most commonly recommended happiness strategies in mainstream media

- Dunigan Folk ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6728-2776 1 &

- Elizabeth Dunn ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1214-7512 1

Nature Human Behaviour volume 7 , pages 1697–1707 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

9552 Accesses

10 Citations

1562 Altmetric

Metrics details

- Social sciences

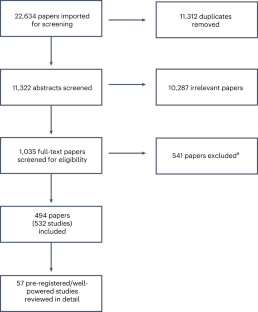

We conducted a systematic review of the evidence underlying some of the most widely recommended strategies for increasing happiness. By coding media articles on happiness, we first identified the five most commonly recommended strategies: expressing gratitude, enhancing sociability, exercising, practising mindfulness/meditation and increasing nature exposure. Next, we conducted a systematic search of the published scientific literature. We identified well-powered, pre-registered experiments testing the effects of these strategies on any aspect of subjective wellbeing (that is, positive affect, negative affect and life satisfaction) in non-clinical samples. A total of 57 studies were included. Our review suggests that a strong scientific foundation is lacking for some of the most commonly recommended happiness strategies. As the effectiveness of these strategies remains an open question, there is an urgent need for well-powered, pre-registered studies investigating strategies for promoting happiness.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Buy this article

- Purchase on Springer Link

- Instant access to full article PDF

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Similar content being viewed by others

A systematic review and multivariate meta-analysis of the physical and mental health benefits of touch interventions

Julian Packheiser, Helena Hartmann, … Frédéric Michon

Anger is eliminated with the disposal of a paper written because of provocation

Yuta Kanaya & Nobuyuki Kawai

Adults who microdose psychedelics report health related motivations and lower levels of anxiety and depression compared to non-microdosers

Joseph M. Rootman, Pamela Kryskow, … Zach Walsh

Data Availability

The results of the media search are available on the Open Science Framework at https://tinyurl.com/2kkayzh9 .

How to be happy, how to get rich - Explore. Google Trends (2021); https://trends.google.com/trends/explore?geo=CA&q=how to be happy,how to get rich

Nelson, L. D., Simmons, J. & Simonsohn, U. Psychology’s Renaissance. Annu. Rev. Psychol. 69 , 511–534 (2018).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Simmons, J. P., Nelson, L. D. & Simonsohn, U. False-positive psychology: undisclosed flexibility in data collection and analysis allows presenting anything as significant. Psychol. Sci. 22 , 1359–1366 (2011).

Nuzzo, R. Scientific method: statistical errors. Nature 506 , 150–152 (2014).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Wagenmakers, E.-J., Wetzels, R., Borsboom, D., van der Maas, H. L. J. & Kievit, R. A. An agenda for purely confirmatory research. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 7 , 632–638 (2012).

Nosek, B. A., Ebersole, C. R., DeHaven, A. C. & Mellor, D. T. The preregistration revolution. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 115 , 2600–2606 (2018).

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Fraley, R. C. & Vazire, S. The N-pact factor: evaluating the quality of empirical journals with respect to sample size and statistical power. PLoS ONE 9 , e109019 (2014).

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

John, L. K., Loewenstein, G. & Prelec, D. Measuring the prevalence of questionable research practices with incentives for truth telling. Psychol. Sci. 23 , 524–532 (2012).

Collaboration, O. S. Estimating the reproducibility of psychological science. Science 349 , aac4716 (2015).

Article Google Scholar

Wagenmakers, E. J. et al. Registered Replication Report: Strack, Martin, & Stepper (1988). Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 11 , 917–928 (2016).

Myers, D. G. & Diener, E. The scientific pursuit of happiness. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13 , 218–225 (2018).

Diener, E. et al. Findings all psychologists should know from the new science on subjective well-being. Can. Psychol. 58 , 87–104 (2017).

Hunt, J. T., Howell, A. J. & Passmore, H.-A. In vivo nature exposure as a positive psychological intervention: a review of the impact of nature interventions on wellbeing. Nat. Health https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003154419-12 (2021).

Funder, D. C. et al. Improving the dependability of research in personality and social psychology: recommendations for research and educational practice. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Rev. 18 , 3–12 (2014).

Carr, A. et al. Effectiveness of positive psychology interventions: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Posit. Psychol. 16 , 749–769 (2021).

Bolier, L. et al. Positive psychology interventions: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health 13 , 119 (2013).

Simonsohn, U., Simmons, J. & Nelson, L. D. Above averaging in literature reviews. Nat. Rev. Psychol. 1 , 551–552 (2022).

Kvarven, A., Strømland, E. & Johannesson, M. Comparing meta-analyses and preregistered multiple-laboratory replication projects. Nat. Hum. Behav. 4 , 423–434 (2019).

Richard, F. D., Bond, C. F. & Stokes-Zoota, J. J. One hundred years of social psychology quantitatively described. Rev. Gen. Psychol. 7 , 331–363 (2003).

Diener, E. Subjective well-being. Psychol. Bull. 95 , 542–575 (1984).

Watson, C., Clark, L. A. & Tellegen, A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: the PANAS scales. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 54 , 1063–1070 (1988).

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, R. & Griffin, S. The satisfaction with life scale. J. Pers. Assess. 49 , 71–75 (1985).

Lyubomirsky, S. & Lepper, H. A measure of subjective happiness: preliminary reliability and construct validation. Soc. Indic. Res. 46 , 137–155 (1999).

Diener, E. & Ryan, K. Subjective well-being: a general overview. South Afr. J. Psychol. 39 , 391–406 (2009).

Nelson-Coffey, S. K., Johnson, C. & Coffey, J. K. Safe haven gratitude improves emotions, well-being, and parenting outcomes among parents with high levels of attachment insecurity. J. Posit. Psychol. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1991454 (2021).

Walsh, L. C., Regan, A., Twenge, J. M. & Lyubomirsky, S. What is the optimal way to give thanks? Comparing the effects of gratitude expressed privately, one-to-one via text, or publicly on social media. Affect. Sci. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42761-022-00150-5 (2022).

Atad, O. I. & Russo-Netzer, P. The effect of gratitude on well-being: should we prioritize positivity or meaning? J. Happiness Stud. 23 , 1245–1265 (2022).

Toepfer, S. M., Cichy, K. & Peters, P. Letters of gratitude: further evidence for author benefits. J. Happiness Stud. 13 , 187–201 (2012).

Shin, L. J. et al. Gratitude in collectivist and individualist cultures. J. Posit. Psychol. 15 , 598–604 (2020).

Titova, L., Wagstaff, A. E. & Parks, A. C. Disentangling the effects of gratitude and optimism: a cross-cultural investigation. J. Cross-Cult. Psychol. 48 , 754–770 (2017).

Walsh, L. C., Regan, A. & Lyubomirsky, S. The role of actors, targets, and witnesses: examining gratitude exchanges in a social context. J. Posit. Psychol. 17 , 233–249 (2022).

Fritz, M. M., Armenta, C. N., Walsh, L. C. & Lyubomirsky, S. Gratitude facilitates healthy eating behavior in adolescents and young adults. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 81 , 4–14 (2019).

Armenta, C. N., Fritz, M. M., Walsh, L. C. & Lyubomirsky, S. Satisfied yet striving: gratitude fosters life satisfaction and improvement motivation in youth. Emotion 22 , 1004–1016 (2020).

Lyubomirsky, S., Dickerhoof, R., Boehm, J. K. & Sheldon, K. M. Becoming happier takes both a will and a proper way: an experimental longitudinal intervention to boost well-being. Emotion 11 , 391–402 (2011).

Oltean, L. E., Miu, A. C., Șoflău, R. & Szentágotai-Tătar, A. Tailoring gratitude interventions. How and for whom do they work? The potential mediating role of reward processing and the moderating role of childhood adversity and trait gratitude. J. Happiness Stud. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00530-5 (2022).

Oishi, S., Koo, M., Lim, N. & Suh, E. M. When gratitude evokes indebtedness. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 11 , 286–303 (2019).

Oliveira, R., Baldé, A., Madeira, M., Ribeiro, T. & Arriaga, P. The impact of writing about gratitude on the intention to engage in prosocial behaviors during the COVID-19 outbreak. Front. Psychol. 12 , https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.588691 (2021).

Layous, K. et al. The proximal experience of gratitude. PLoS ONE 12 , 1–26 (2017).

Asebedo, S. D., Seay, M. C., Little, T. D., Enete, S. & Gray, B. Three good things or three good financial things? Applying a positive psychology intervention to the personal finance domain. J. Posit. Psychol. 16 , 481–491 (2021).

Neumeier, L. M., Brook, L., Ditchburn, G. & Sckopke, P. Delivering your daily dose of well-being to the workplace: a randomized controlled trial of an online well-being programme for employees. Eur. J. Work Organ. Psychol. 26 , 555–573 (2017).

Manthey, L., Vehreschild, V. & Renner, K. H. Effectiveness of two cognitive interventions promoting happiness with video-based online instructions. J. Happiness Stud. 17 , 319–339 (2016).

Cunha, L. F., Pellanda, L. C. & Reppold, C. T. Positive psychology and gratitude interventions: a randomized clinical trial. Front. Psychol. 10 , https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00584 (2019).

Regan, A., Walsh, L. C. & Lyubomirsky, S. Are some ways of expressing gratitude more beneficial than others? Results from a randomized controlled experiment. Affect. Sci. 4 , 72–81 (2022).

Layous, K., Kumar, S. A., Arendtson, M. & Najera, A. The effects of rumination, distraction, and gratitude on positive and negative affect. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 124 , 1053–1078 (2022).

Baumeister, R. F. & Leary, M. R. The need to belong: desire for interpersonal attachments as a fundamental human motivation. Psychol. Bull. 117 , 497–529 (1995).

Dunbar, R. I. M. & Shultz, S. Evolution in the social brain. Science 317 , 1344–1347 (2007).

Ryan, R. M. & Deci, E. L. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am. Psychol. 55 , 68–78 (2000).

Kardas, M., Schroeder, J. & Brien, E. O. Keep talking: (mis)understanding the hedonic trajectory of conversation. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. , 123 , 717–740 (2022).

Schroeder, J., Lyons, D. & Epley, N. Hello, stranger? Pleasant conversations are preceded by concerns about starting one. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 151 , 1141–1153 (2022).

Jacques-Hamilton, R., Sun, J. & Smillie, L. D. Costs and benefits of acting extraverted: a randomized controlled trial. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 148 , 1538–1556 (2018).

Margolis, S. & Lyubomirsky, S. Experimental manipulation of extraverted and introverted behavior and its effects on well-being. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 149 , 719–731 (2020).

Gunaydin, G., Oztekin, H., Karabulut, D. H. & Salman-Engin, S. Minimal social interactions with strangers predict greater subjective well-being. J. Happiness Stud. Interdiscip. Forum Subj. Well-Being 22 , 1839–1853 (2021).

Google Scholar

Van Dam, N. T. et al. Mind the hype: a critical evaluation and prescriptive agenda for research on mindfulness and meditation. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 13 , 36–61 (2018).

Kabat-Zinn, J. Mindfulness-based interventions in context: past, present, and future. Clin. Psychol. Sci. Pract. 10 , 144–156 (2003).

Brown, K. W. & Ryan, R. M. The benefits of being present: mindfulness and its role in psychological well-being. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 84 , 822–848 (2003).

Noone, C. & Hogan, M. J. A randomised active-controlled trial to examine the effects of an online mindfulness intervention on executive control, critical thinking and key thinking dispositions in a university student sample. BMC Psychol. 6 , 1–18 (2018).

Krick, A. & Felfe, J. Who benefits from mindfulness? The moderating role of personality and social norms for the effectiveness on psychological and physiological outcomes among police officers. J. Occup. Health Psychol. 25 , 99–112 (2019).

De Vibe, M. et al. Mindfulness training for stress management: a randomised controlled study of medical and psychology students. BMC Med. Educ. 13 , 107 (2013).

Solhaug, I. et al. Long-term mental health effects of mindfulness training: a 4-year follow-up study. Mindfulness 10 , 1661–1672 (2019).

Gallegos, A., Hoerger, M., Talbot, N., Moynihan, J. & Duberstein, P. Emotional benefits of mindfulness-based stress reduction in older adults: the moderating roles of age and depressive symptom severity. Aging Ment. Health 17 , 823–829 (2013).

Fredrickson, B., Cohn, M. & Al, E. Open hearts build lives: positive emotions, induced through loving-kindness meditation, build consequential personal resources. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 95 , 1045–1062 (2008).

Pandya, S. P. Meditation program mitigates loneliness and promotes wellbeing, life satisfaction and contentment among retired older adults: a two-year follow-up study in four South Asian cities. Aging Ment. Health 25 , 286–298 (2021).

Bojanowska, A., Kaczmarek, Ł. D., Urbanska, B. & Puchalska, M. Acting on values: a novel intervention enhancing hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. J. Happiness Stud. 23 , 3889–3908 (2022).

Cheung, R. Y. M., Chan, S. K. C., Chui, H., Chan, W. M. & Ngai, S. Y. S. Enhancing parental well-being: initial efficacy of a 21-day online self-help mindfulness-based intervention for parents. Mindfulness 13 , 2812–2826 (2022).

Chen, S. & Jordan, C. H. Incorporating ethics into brief mindfulness practice: effects on well-being and prosocial behavior. Mindfulness 11 , 18–29 (2020).

Rhodes, R. E., Janssen, I., Bredin, S. S. D., Warburton, D. E. R. & Bauman, A. Physical activity: health impact, prevalence, correlates and interventions. Psychol. Health 32 , 942–975 (2017).

Kokkinos, P. Physical activity, health benefits, and mortality risk. ISRN Cardiol. 2012 , 1–14 (2012).

Haskell, W. L., Blair, S. N. & Hill, J. O. Physical activity: health outcomes and importance for public health policy. Prev. Med. 49 , 280–282 (2009).

Matzer, F., Nagele, E., Lerch, N., Vajda, C. & Fazekas, C. Combining walking and relaxation for stress reduction—a randomized cross-over trial in healthy adults. Stress Health 34 , 266–277 (2018).

Bernstein, E. E. & McNally, R. J. Acute aerobic exercise hastens emotional recovery from a subsequent stressor. Health Psychol. 36 , 560–567 (2017).

Miller, J. C. & Krizan, Z. Walking facilitates positive affect (even when expecting the opposite). Emotion 16 , 775–785 (2016).

Bryan, A., Hutchison, K. E., Seals, D. R. & Allen, D. L. A transdisciplinary model integrating genetic, physiological, and psychological correlate of voluntary exercise. Health Psychol. 26 , 30–39 (2007).

Müller, C. et al. Effects of a single physical or mindfulness intervention on mood, attention, and executive functions: results from two randomized controlled studies in university classes. Mindfulness 12 , 1282–1293 (2021).

Steinberg, H. et al. Exercise enhances creativity independently of mood. Br. J. Sports Med. 31 , 240–245 (1997).

Hui, B. P. H., Parma, L., Kogan, A. & Vuillier, L. Hot yoga leads to greater well-being: a six-week experience-sampling RCT in healthy adults. Psychosoc. Inter. 31 , 67–82 (2022).

Brailovskaia, J., Swarlik, V. J., Grethe, G. A., Schillack, H. & Margraf, J. Experimental longitudinal evidence for causal role of social media use and physical activity in COVID-19 burden and mental health. J. Public Health https://doi.org/10.1007/s10389-022-01751 (2022).

Tse, M. M. Y., Tang, S. K., Wan, V. T. C. & Vong, S. K. S. The effectiveness of physical exercise training in pain, mobility, and psychological well-being of older persons living in nursing homes. Pain. Manag. Nurs. 15 , 778–788 (2014).

Lai, A. Y. K. et al. A community-based lifestyle-integrated physical activity intervention to enhance physical activity, positive family communication, and perceived health in deprived families: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Front. Public Health 8 , https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00434 (2020).

Sjögren, T. et al. Effects of a physical exercise intervention on subjective physical well-being, psychosocial functioning and general well-being among office workers: a cluster randomized-controlled cross-over design. Scand. J. Med. Sci. Sports 16 , 381–390 (2006).

Courneya, K. S., McNeil, J., O’Reilly, R., Morielli, A. R. & Friedenreich, C. M. Dose–response effects of aerobic exercise on quality of life in postmenopausal women: results from the Breast Cancer and Exercise Trial in Alberta (BETA). Ann. Behav. Med. 51 , 356–364 (2017).

de Kort, Y. A. W., Meijnders, A. L., Sponselee, A. A. G. & IJsselsteijn, W. A. What’s wrong with virtual trees? Restoring from stress in a mediated environment. J. Environ. Psychol. 26 , 309–320 (2006).

Zelenski, J. M., Dopko, R. L. & Capaldi, C. A. Cooperation is in our nature: nature exposure may promote cooperative and environmentally sustainable behavior. J. Environ. Psychol. 42 , 24–31 (2015).

Tyrväinen, L. et al. The influence of urban green environments on stress relief measures: a field experiment. J. Environ. Psychol. 38 , https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2013.12.005 (2014).

Vert, C. et al. Physical and mental health effects of repeated short walks in a blue space environment: a randomised crossover study. Environ. Res. 188 , 109812 (2020).

Izenstark, D., Ravindran, N., Rodriguez, S. & Devine, N. The affective and conversational benefits of a walk in nature among mother–daughter dyads. Appl. Psychol. Health Well-Being 13 , 299–316 (2021).

Passmore, H. A. & Holder, M. D. Noticing nature: Individual and social benefits of a two-week intervention. J. Posit. Psychol. 12 , 537–546 (2017).

McEwan, K., Richardson, M., Sheffield, D., Ferguson, F. J. & Brindley, P. A smartphone app for improving mental health through connecting with urban nature. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 16 , 1–15 (2019).

Chambers, C. D. Registered reports: a new publishing initiative at Cortex. Cortex https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cortex.2012.12.016 (2013).

Tversky, A. & Kahneman, D. Availability: a heuristic for judging frequency and probability. Cogn. Psychol. 5 , 207–232 (1973).

Buettner, D., Nelson, T. & Veenhoven, R. Ways to greater happiness: a Delphi study. J. Happiness Stud. 21 , 2789–2806 (2020).

Yarkoni, T. The generalizability crisis. Behav. Brain Sci. 45 , e1 (2022).

Henrich, J., Heine, S. J. & Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 33 , 61–83 (2010).

Lyubomirsky, S. & Layous, K. How do simple positive activities increase well-being? Curr. Dir. Psychol. Sci. 22 , 57–62 (2013).

Blake, K. R. & Gangestad, S. On attenuated interactions, measurement error, and statistical power: guidelines for social and personality psychologists. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 46 , 1702–1711 (2020).

Wood, A. M. et al. in The Wiley Handbook of Positive Clinical Psychology (eds Wood, A. M. & Johnson, J.) 137–151 (John Wiley & Sons, 2016).

Fritz, M. M. & Lyubomirsky, S. in The Social Psychology of Living Well (eds Forgas, J. P. & Baumeister, R. F.) Chap 7 (Routledge, 2018).

Farias, M., Maraldi, E., Wallenkampf, K. C. & Lucchetti, G. Adverse events in meditation practices and meditation‐based therapies: a systematic review. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 142 , 374–393 (2020).

Landis, J. R. & Koch, G. G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 33 , 159 (1977).

Download references

Acknowledgements

We thank S. Lyubomirsky and H. Passmore for comments on a previous version of this manuscript, and M. Smith for providing guidance on conducting the systematic literature search. We also thank J. Tan, P. Ramachadran, R. Li, R. Kaur, C. Peretz and C. Cardle for assistance with the media and scholarly literature searches. Our work was supported by grant #GR012572 from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada (SSHRC; E.D.) and the SSHRC Doctoral Award #6567 (D.F.). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish or preparation of the manuscript.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Psychology Department, The University of British Columbia, Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada

Dunigan Folk & Elizabeth Dunn

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

D.F. and E.D. both contributed to the conceptualization and writing of the manuscript. D.F. managed the literature review and effect size extraction.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Dunigan Folk .

Ethics declarations

Competing interests.

The authors have no competing interests to declare.

Peer review

Peer review information.

Nature Human Behaviour thanks Kirk Brown, Jessie Sun, Katie Hobbs and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. Peer reviewer reports are available.

Additional information

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

Supplementary information.

Supplemental Tables 1–6.

Reporting Summary

Peer review file, rights and permissions.

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

Folk, D., Dunn, E. A systematic review of the strength of evidence for the most commonly recommended happiness strategies in mainstream media. Nat Hum Behav 7 , 1697–1707 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01651-4

Download citation

Received : 04 February 2022

Accepted : 09 June 2023

Published : 20 July 2023

Issue Date : October 2023

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-023-01651-4

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

This article is cited by

Long-term analysis of a psychoeducational course on university students’ mental well-being.

- Catherine Hobbs

- Sarah Jelbert

Higher Education (2024)

Centenary Personality: Are There Psychological Resources that Distinguish Centenarians?

- Mª Dolores Merino

- Marta Sánchez-Ortega

- Inmaculada Mateo-Rodríguez

Journal of Happiness Studies (2023)

Mindfulness and Happiness

- Bassam Khoury

Mindfulness (2023)

Worker Well-Being: A Continuous Improvement Framework

- Lisa C. Walsh

- Madison Montemayor-Dominguez

- Sonja Lyubomirsky

Applied Research in Quality of Life (2023)

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

Sign up for the Nature Briefing newsletter — what matters in science, free to your inbox daily.

Happiness and Life Satisfaction

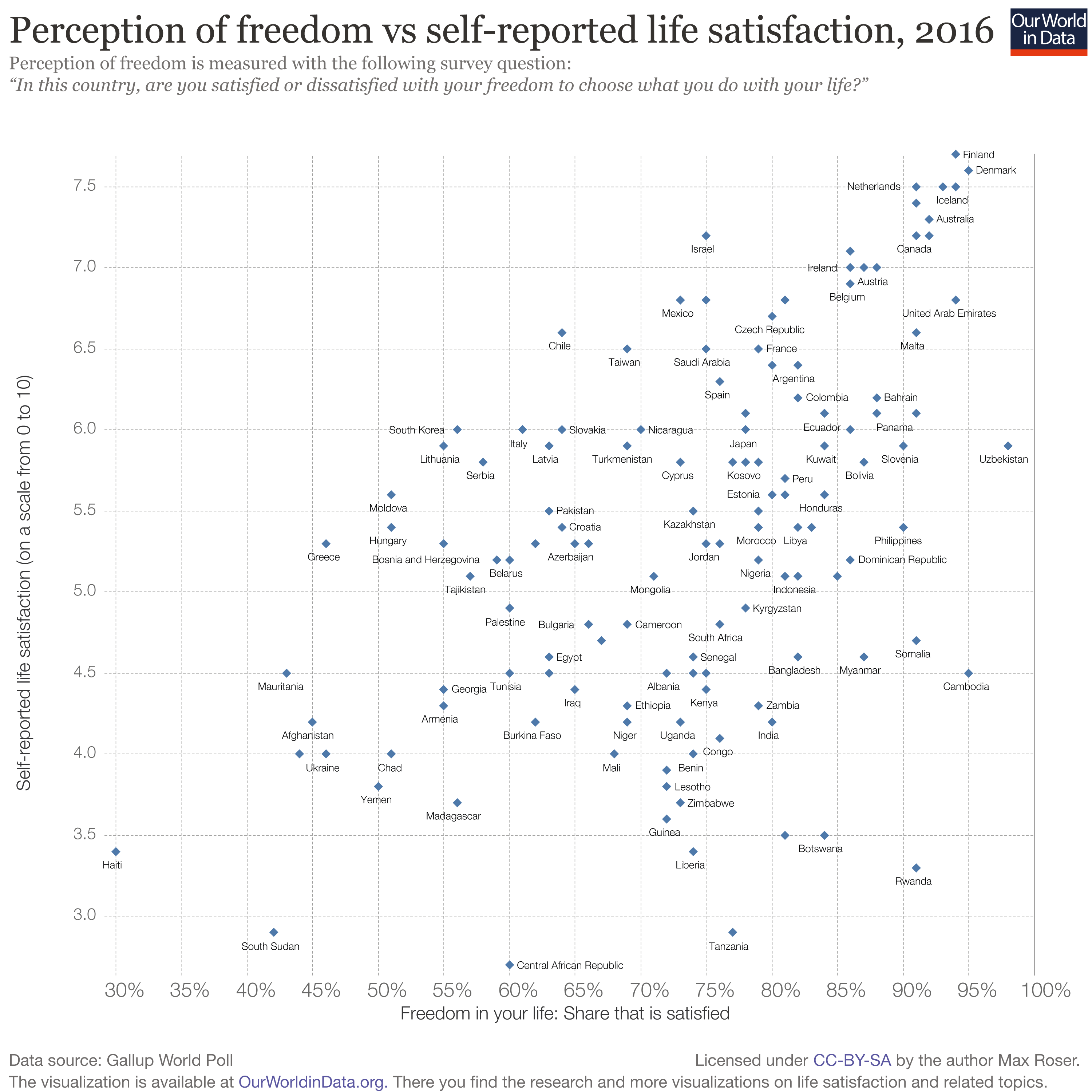

Self-reported life satisfaction differs widely between people and between countries. What explains these differences?

By Esteban Ortiz-Ospina and Max Roser

First published in 2013; most recent substantive revision February 2024.

How happy are people today? Were people happier in the past? How satisfied with their lives are people in different societies? And how do our living conditions affect all of this?

These are difficult questions to answer, but they are questions that undoubtedly matter for each of us personally. Indeed, today, life satisfaction and happiness are central research areas in the social sciences, including in ‘mainstream’ economics.

Social scientists often recommend that measures of subjective well-being should augment the usual measures of economic prosperity, such as GDP per capita . 1 But how can happiness be measured? Are there reliable comparisons of happiness across time and space that can give us clues regarding what makes people declare themselves ‘happy’?

In this topic page, we discuss the data and empirical evidence that might answer these questions. Our focus here will be on survey-based measures of self-reported happiness and life satisfaction. Here is a preview of what the data reveals.

- Surveys asking people about life satisfaction and happiness do measure subjective well-being with reasonable accuracy.

- Life satisfaction and happiness vary widely both within and among countries. It only takes a glimpse at the data to see that people are distributed along a wide spectrum of happiness levels.

- Richer people tend to say they are happier than poorer people; richer countries tend to have higher average happiness levels; and across time, most countries that have experienced sustained economic growth have seen increasing happiness levels. So, the evidence suggests that income and life satisfaction tend to go together (which still doesn’t mean they are one and the same).

- Important life events such as marriage or divorce do affect our happiness but have surprisingly little long-term impact. The evidence suggests that people tend to adapt to changes.

See all interactive charts on Happiness and Life Satisfaction ↓

Other research and writing on happiness and life satisfaction on Our World in Data:

- Are Facebook and other social media platforms bad for our well-being?

- Are people more likely to be lonely in so-called 'individualistic' societies?

- Are we happier when we spend more time with others?

- Collective pessimism and our inability to guess the happiness of others

- How important are social relations for our health and well-being?

- Is there a loneliness epidemic?

- There is a 'happiness gap' between East and West Germany

Happiness across the world today

The World Happiness Report is a well-known source of cross-country data and research on self-reported life satisfaction. The map here shows, country by country, the ‘happiness scores’ published this report.

The underlying source of the happiness scores in the World Happiness Report is the Gallup World Poll —a set of nationally representative surveys undertaken in more than 160 countries in over 140 languages.

The main life evaluation question asked in the poll is: “Please imagine a ladder, with steps numbered from 0 at the bottom to 10 at the top. The top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you, and the bottom of the ladder represents the worst possible life for you. On which step of the ladder would you say you personally feel you stand at this time?” (This is also known as the “Cantril Ladder”.)

The map plots the average answer that survey respondents provided to this question in different countries. As with the steps of the ladder, values in the map range from 0 to 10.

There are large differences across countries. According to the most recent figures, European countries top the ranking: Finland, Denmark, Iceland, Switzerland, and the Netherlands have the highest scores. In the same year, the lowest national scores correspond to Afghanistan, South Sudan, and other countries in central Sub-Saharan Africa.

You can click on any country on the map to plot time series for specific countries.

Self-reported life satisfaction tends to correlate with other measures of well-being—richer and healthier countries tend to have higher average happiness scores. (More on this in the section below .)

Happiness over time

Findings from the integrated values surveys.

In addition to the Gallup World Poll (discussed above), the Integrated Values Surveys provides cross-country data on self-reported life satisfaction. These are the longest available time series of cross-country happiness estimates that include non-European nations.

The Integrated Values Surveys collect data from a series of representative national surveys covering almost 100 countries, with the earliest estimates dating back to 1981. In these surveys, respondents are asked: “Taking all things together, would you say you are (i) Very happy, (ii) Rather happy, (iii) Not very happy, or (iv) Not at all happy”. This visualization plots the share of people answering they are “very happy” or “rather happy”.

As we can see, in most countries, the trend is positive: In most countries with data from two or more surveys, the most recent observation is higher than the earliest. In some cases, the improvement has been very large; in Albania, for example, the share of people who reported being ‘very happy’ or ‘rather happy’ went from 33.4% in 1998 to 73.9% in 2022.

Findings from Eurobarometer

The Eurobarometer survey collects data on life satisfaction as part of their public opinion surveys. For several countries, these surveys have been conducted at least annually for more than 40 years. The visualization here shows the share of people who report being ‘very satisfied’ or ‘fairly satisfied’ with their standards of living.

Two points are worth emphasizing. First, estimates of life satisfaction often fluctuate around trends. In France, for example, we can see that the overall trend is positive, yet there is a pattern of ups and downs. And second, despite fluctuations, decade-long trends have been generally positive for most European countries.

In most cases, the share of people who say they are ‘very satisfied’ or ‘fairly satisfied’ with their life has gone up over the full survey period. 2 Yet there are some clear exceptions, of which Greece is the most notable example. In 2007, around 67% of the Greeks said they were satisfied with their life, but five years later, after the financial crisis struck, the corresponding figure was down to 32.4%. Despite recent improvements, Greeks today are, on average, much less satisfied with their lives than they were before the financial crisis. No other European country in this dataset has gone through a comparable negative shock.

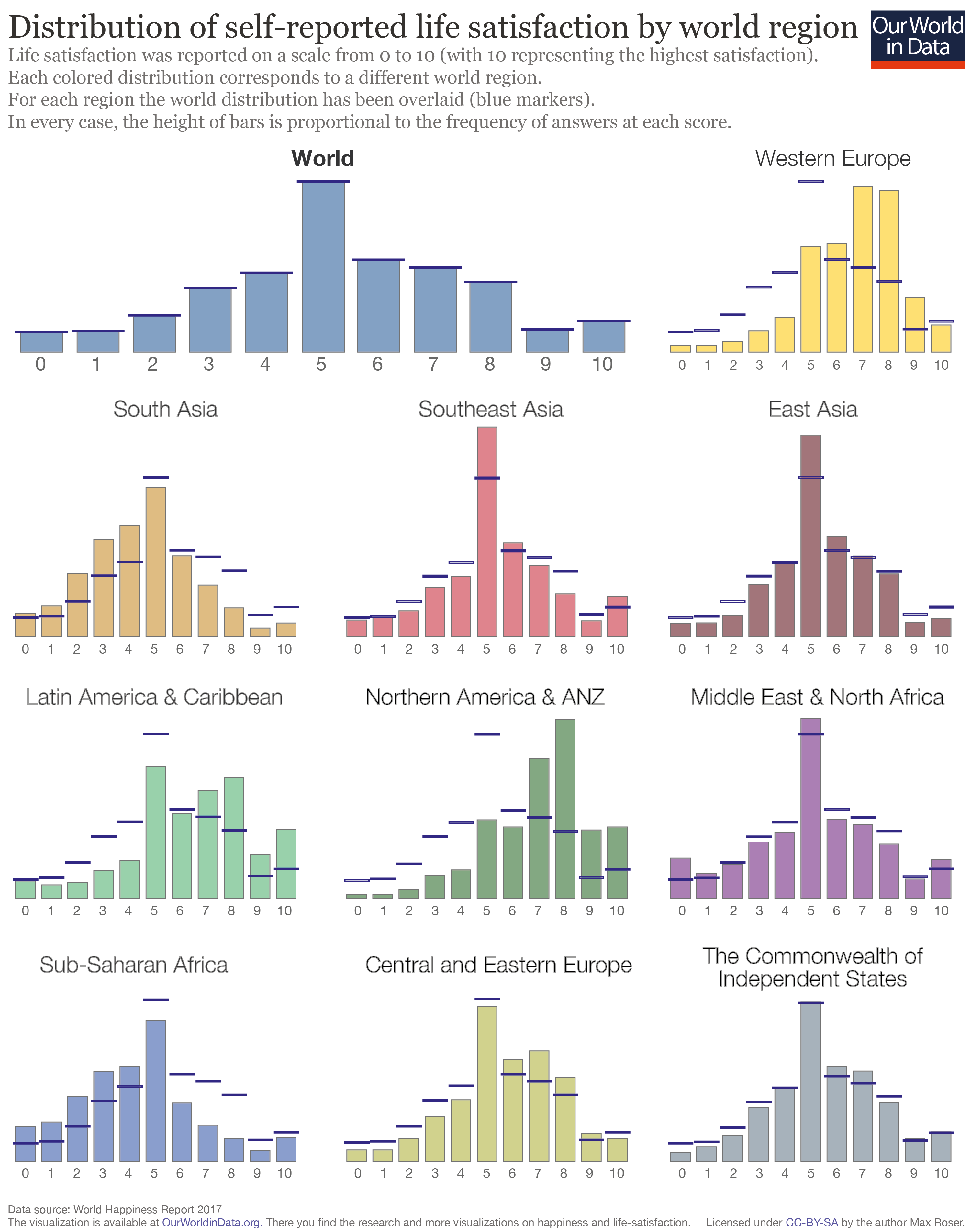

The distribution of life satisfaction

More than averages — the distribution of life satisfaction scores.

Most of the studies comparing happiness and life satisfaction among countries focus on averages. However, distributional differences are also important.

Life satisfaction is often reported on a scale from 0 to 10, with 10 representing the highest possible level of satisfaction. This is the so-called ‘Cantril Ladder’. This visualization shows how responses are distributed across steps in this ladder. In each case, the height of the bars is proportional to the fraction of answers at each score. Each differently-colored distribution refers to a world region, and for each region, we have overlaid the distribution for the entire world as a reference.

These plots show that in Sub-Saharan Africa—the region with the lowest average scores—the distributions are consistently to the left of those in Europe.

This means that the share of people who are ‘happy’ is lower in Sub-Saharan Africa than in Western Europe, independently of which score in the ladder we use as a threshold to define ‘happy’. Similar comparisons can be made by contrasting other regions with high average scores (e.g., North America, Australia, and New Zealand) against those with low average scores (e.g., South Asia).

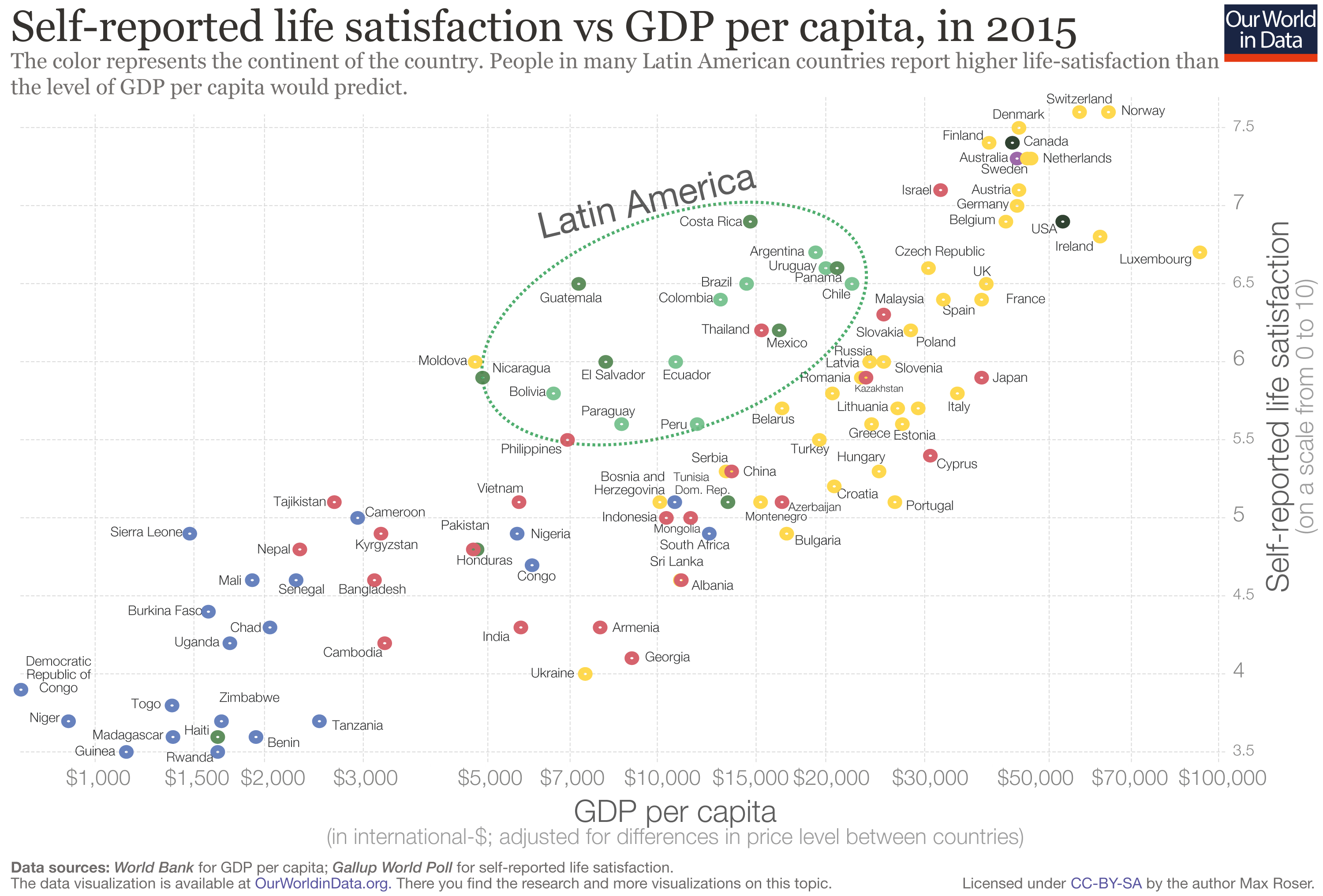

Another important point to notice is that the distribution of self-reported life satisfaction in Latin America and the Caribbean is high across the board—it is consistently to the right of other regions with roughly comparable income levels, such as Central and Eastern Europe.

This is part of a broader pattern: Latin American countries tend to have a higher subjective well-being than other countries with comparable levels of economic development. As we will see in the section on the social environment , culture, and history matter for self-reported life satisfaction.

If you want data on country-level distributions of scores, the Pew Global Attitudes Survey provides such figures for more than 40 countries.

Differences in happiness within countries

Happiness inequality, happiness inequality in the us and other rich countries.

The General Social Survey (GSS) in the US is a survey administered to a nationally representative sample of about 1,500 respondents each year since 1972 and is an important source of information on long-run trends of self-reported life satisfaction in the country. 3

Using this source, Stevenson and Wolfers (2008) 4 show that while the national average has remained broadly constant, inequality in happiness has fallen substantially in the US in recent decades.

The authors further note that this is true both when we think about inequality in terms of the dispersion of answers, and also when we think about inequality in terms of gaps between demographic groups. They note that two-thirds of the black-white happiness gap has been eroded (although today, white Americans remain happier on average, even after controlling for differences in education and income), and the gender happiness gap has disappeared entirely (women used to be slightly happier than men, but they are becoming less happy, and today there is no statistical difference once we control for other characteristics). 5

The results from Stevenson and Wolfers are consistent with other studies looking at changes of happiness inequality (or life satisfaction inequality) over time. In particular, researchers have noted that there is a correlation between economic growth and reductions in happiness inequality—even when income inequality is increasing at the same time. The visualization here uses data from Clark, Fleche, and Senik (2015) 6 shows this. It plots the evolution of happiness inequality within a selection of rich countries that experienced uninterrupted GDP growth.

In this chart, happiness inequality is measured by the dispersion — specifically the standard deviation — of answers in the World Values Survey . As we can see, there is a broad negative trend. In their paper, the authors show that the trend is positive in countries with falling GDP.

Why could it be that happiness inequality falls with rising income inequality?

Clark, Fleche, and Senik argue that part of the reason is that the growth of national income allows for the greater provision of public goods, which in turn tightens the distribution of subjective well-being. This can still be consistent with growing income inequality since public goods such as better health affect incomes and well-being differently.

Another possibility is that economic growth in rich countries has translated into a more diverse society in terms of cultural expressions (e.g., through the emergence of alternative lifestyles), which has allowed people to converge in happiness even if they diverge in incomes, tastes, and consumption. Steven Quartz and Annette Asp explain this hypothesis in a New York Times article , discussing evidence from experimental psychology.

The link between happiness and income

The link across countries, higher national incomes go together with higher average life satisfaction.

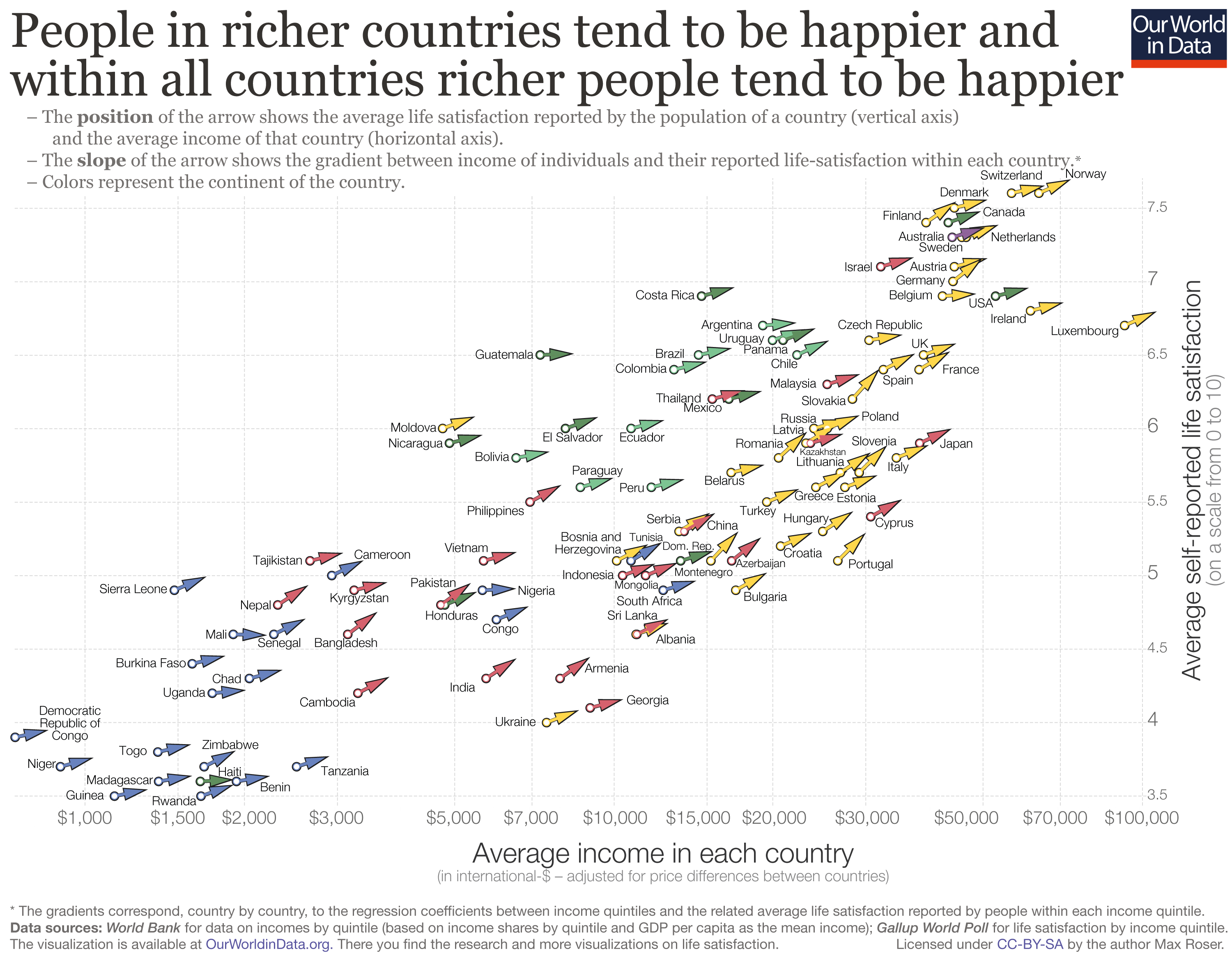

If we compare life satisfaction reports from around the world at any given point in time, we immediately see that countries with higher average national incomes tend to have higher average life satisfaction scores. In other words, people in richer countries tend to report higher life satisfaction than people in poorer countries. The scatter plot here shows this.

Each dot in the visualization represents one country. The vertical position of the dots shows the national average self-reported life satisfaction in the Cantril Ladder (a scale ranging from 0-10 where 10 is the highest possible life satisfaction), while the horizontal position shows GDP per capita based on purchasing power parity (i.e., GDP per head after adjusting for inflation and cross-country price differences).

This correlation holds even if we control for other factors: Richer countries tend to have higher average self-reported life satisfaction than poorer countries that are comparable in terms of demographics and other measurable characteristics. You can read more about this in the World Happiness Report 2017 , specifically the discussion in Chapter 2.

As we show below, income and happiness also tend to go together within countries and across time .

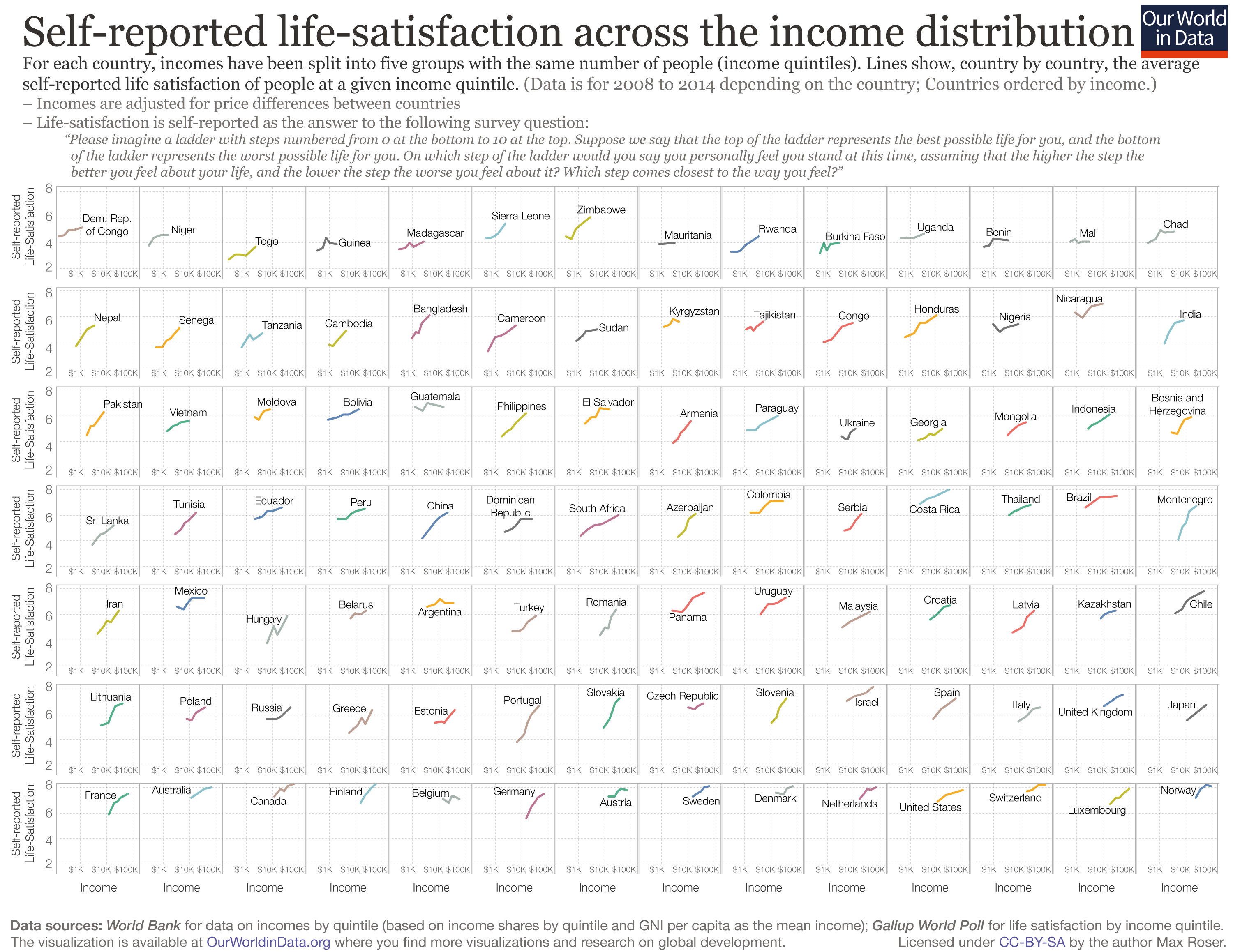

The link within countries

Higher personal incomes go together with higher self-reported life satisfaction.

Above; we point out that richer countries tend to be happier than poorer countries. Here, we show that the same tends to be true within countries: richer people within a country tend to be happier than poorer people in the same country. The visualizations here show us this by looking at happiness by income quintiles.

Firstly, we show each country in individual panels: within each panel is a connected scatter plot for a specific country. This means that for each country, we observe a line joining five points: each point marks the average income within an income quintile (horizontal axis) against the average self-reported life satisfaction of people at that income quintile (vertical axis).

What does this visualization tell us? We see that in all cases, lines are upward sloping: people in higher income quintiles tend to have higher average life satisfaction. Yet in some countries, the lines are steep and linear (e.g., in Costa Rica, richer people are happier than poorer people across the whole income distribution), while in some countries, the lines are less steep and non-linear (e.g., the richest group of people in the Dominican Republic is as happy as the second-richest group).

In a second visualization, we present the same data, but instead of plotting each country separately, showing all countries in one grid.

The resulting connected scatter plot may be messy, resembling a ‘spaghetti’ chart, but it is helpful to confirm the overall pattern: despite kinks here and there, lines are, by and large, upward-sloping.

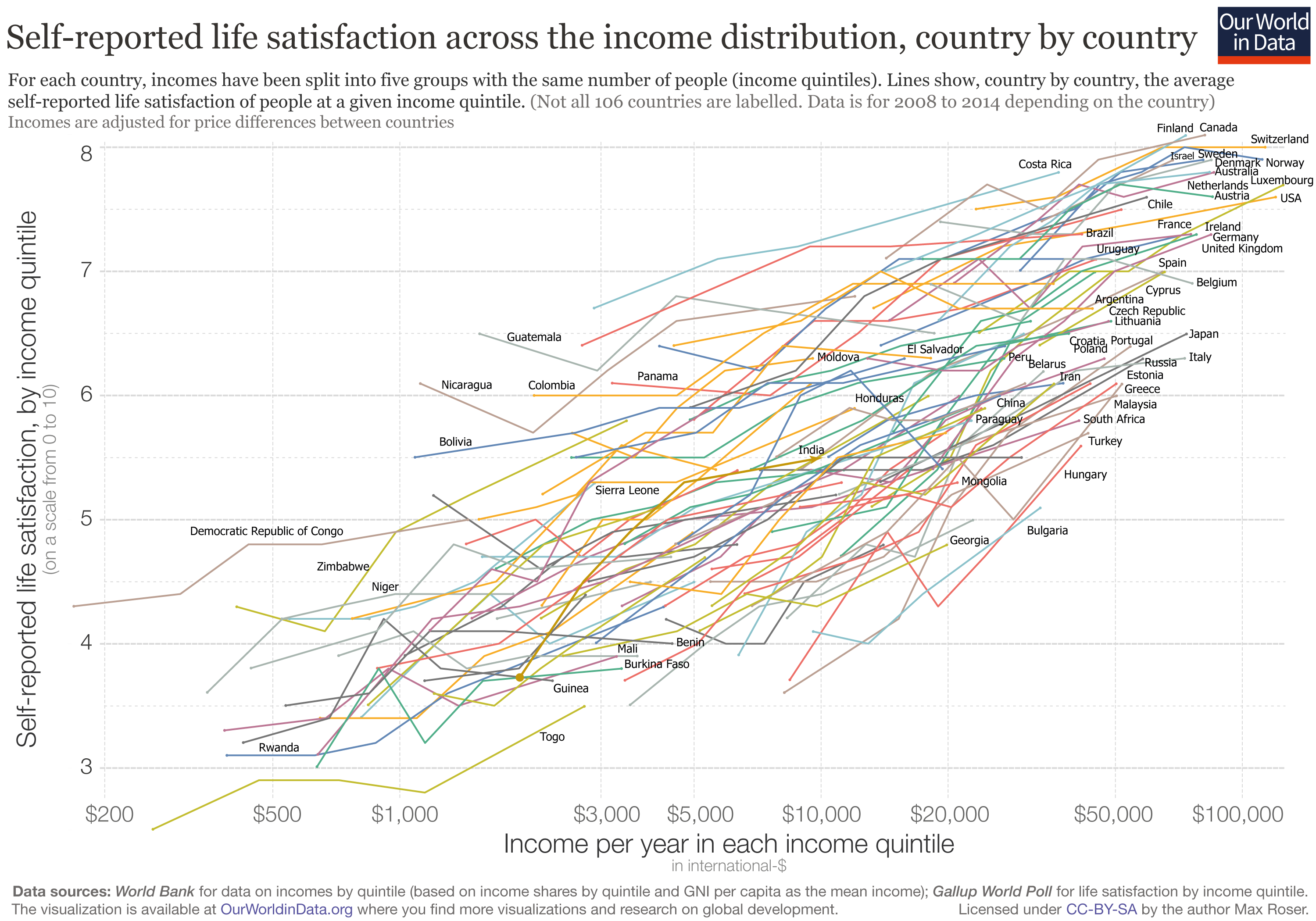

Looking across and within countries

A snapshot of the correlation between income and happiness—between and within countries.

Do income and happiness tend to go together? The visualization here shows that the answer to this question is yes, both within and across countries.

It may take a minute to wrap your head around this visualization, but once you do, you can see that it handily condenses the key information from the previous three charts into one.

To show the income-happiness correlation across countries, the chart plots the relationship between self-reported life satisfaction on the vertical axis and GDP per capita on the horizontal axis. Each country is an arrow on the grid, and the location of the arrow tells us the corresponding combination of average income and average happiness.

To show the income-happiness correlation within countries, each arrow has a slope corresponding to the correlation between household incomes and self-reported life satisfaction within that country. In other words, the slope of the arrow shows how strong the relationship between income and life satisfaction is within that country. ( This chart gives you a visual example of how the arrows were constructed for each country). 7

If an arrow points northeast, that means richer people tend to report higher life satisfaction than poorer people in the same country. If an arrow is flat (i.e., points east), that means rich people are, on average, just as happy as poorer people in the same country.

As we can see, there is a very clear pattern: richer countries tend to be happier than poorer countries (observations are lined up around an upward-sloping trend), and richer people within countries tend to be happier than poorer people in the same countries (arrows are consistently pointing northeast).

It’s important to note that the horizontal axis is measured on a logarithmic scale. The cross-country relationship we would observe on a linear scale would be different since, at high national income levels, slightly higher national incomes are associated with a smaller increase in average happiness than at low levels of national incomes. In other words, the cross-country relationship between income and happiness is not linear on income (it is ‘log-linear’). We use the logarithmic scale to highlight two key facts: (i) at no point in the global income distribution is the relationship flat, and (ii) a doubling of the average income is associated with roughly the same increase in the reported life satisfaction, irrespective of the position in the global distribution.

These findings have been explored in more detail in a number of recent academic studies. Importantly, the much-cited paper by Stevenson and Wolfers (2008) 8 shows that these correlations hold even after controlling for various country characteristics, such as the demographic composition of the population, and are robust to different sources of data and types of subjective well-being measures.

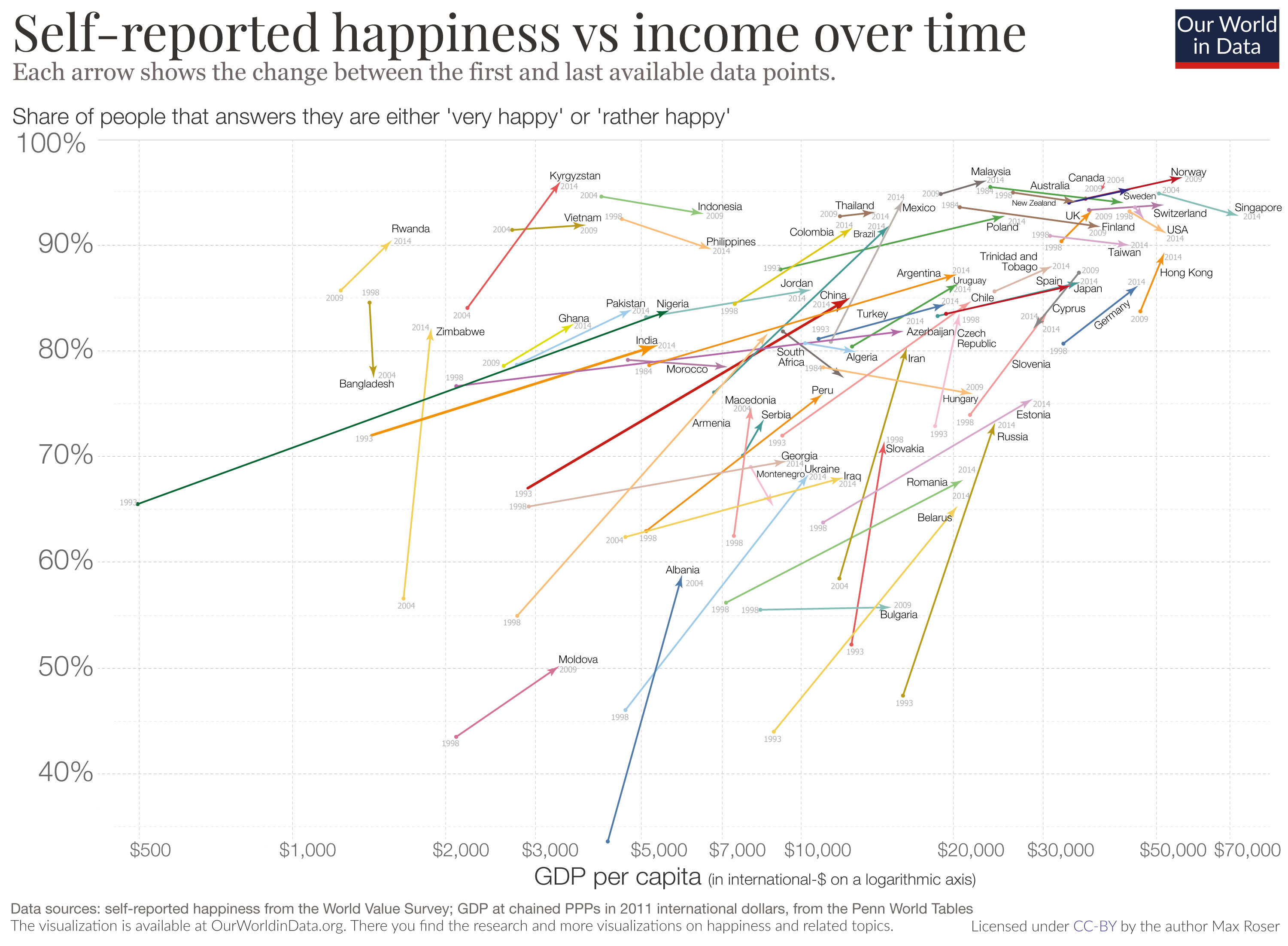

Economic growth and happiness

In the charts above, we show that there is robust evidence of a strong correlation between income and happiness across and within countries at fixed points in time. Here, we want to show that, while less strong, there is also a correlation between income and happiness across time. Or, put differently, as countries get richer, the population tends to report higher average life satisfaction.

The chart shown here uses data from the World Values Survey to plot the evolution of national average incomes and national average happiness over time. To be specific, this chart shows the share of people who say they are ‘very happy’ or ‘rather happy’ in the World Values Survey (vertical axis) against GDP per head (horizontal axis). Each country is drawn as a line joining the first and last available observations across all survey waves. 9

As we can see, countries that experience economic growth also tend to experience happiness growth across waves in the World Values Survey. This is a correlation that holds after controlling for other factors that also change over time (in this chart from Stevenson and Wolfers (2008), you can see how changes in GDP per capita compare to changes in life satisfaction after accounting for changes in demographic composition and other variables).

An important point to note here is that economic growth and happiness growth tend to go together on average . Some countries, in some periods, experience economic growth without increasing happiness. The experience of the US in recent decades is a case in point. These instances may seem paradoxical given the evidence—we explore this question in the following section.

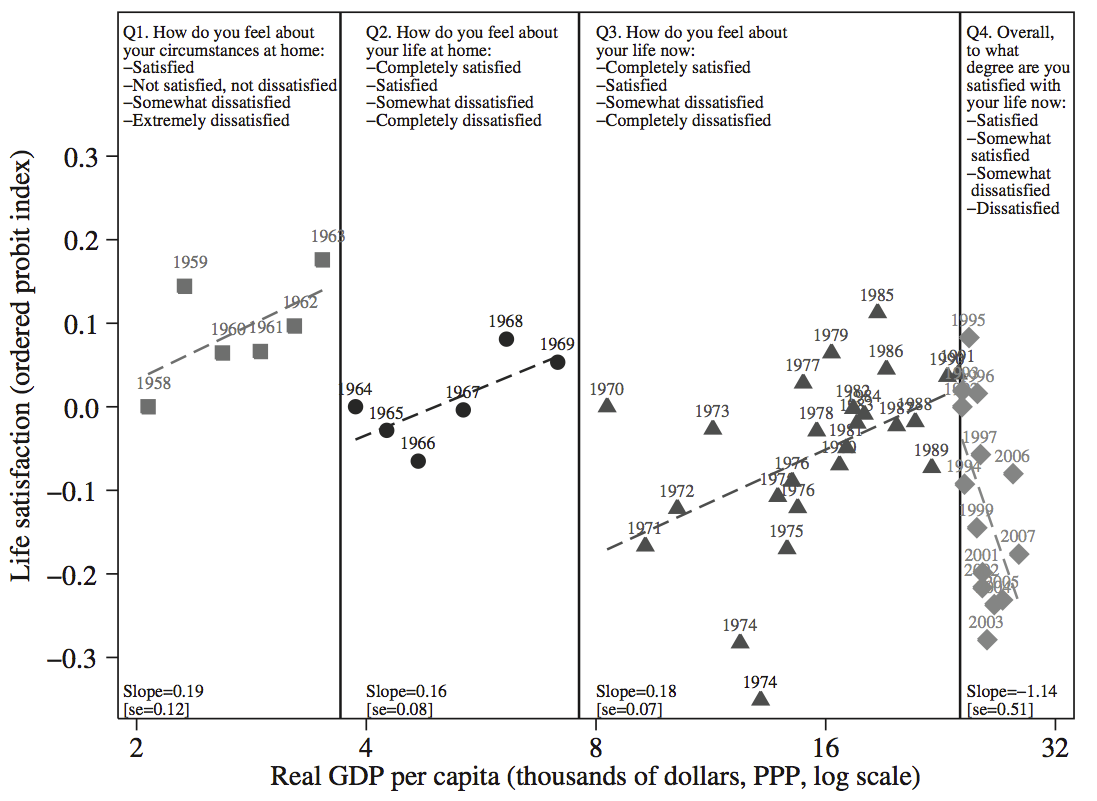

The Easterlin Paradox

The observation that economic growth does not always go together with increasing life satisfaction was first made by Richard Easterlin in the 1970s. Since then, there has been much discussion over what came to be known as the ‘Easterlin Paradox’.

At the heart of the paradox was the fact that richer countries tend to have higher self-reported happiness, yet in some countries for which repeated surveys were available over the course of the 1970s, happiness was not increasing with rising national incomes. This combination of empirical findings was paradoxical because the cross-country evidence (countries with higher incomes tended to have higher self-reported happiness) did not, in some cases, fit the evidence over time (countries seemed not to get happier as national incomes increased).

Notably, Easterlin and other researchers relied on data from the US and Japan to support this seemingly perplexing observation. If we look closely at the data underpinning the trends in these two countries, however, these cases are not, in fact, paradoxical.

Let us begin with the case of Japan. There, the earliest available data on self-reported life satisfaction came from the so-called ‘Life in Nation surveys’, which date back to 1958. At first glance, this source suggests that mean life satisfaction remained flat over a period of spectacular economic growth (see, for example, this chart from Easterlin and Angelescu 2011). 10 Digging a bit deeper, however, we find that things are more complex.

Stevenson and Wolfers (2008) 8 show that the life satisfaction questions in the ‘Life in Nation surveys’ changed over time, making it difficult—if not impossible—to track changes in happiness over the full period. The visualization here splits the life satisfaction data from the surveys into sub-periods where the questions remained constant. As we can see, the data is not supportive of a paradox: the correlation between GDP and happiness growth in Japan is positive within comparable survey periods. The reason for the alleged paradox is, in fact mismeasurement of how happiness changed over time.

In the US, the explanation is different but can once again be traced to the underlying data. Specifically, if we look more closely at economic growth in the US over the recent decades, one fact looms large: growth has not benefitted the majority of people. Income inequality in the US is exceptionally high and has been on the rise in the last four decades, with incomes for the median household growing much more slowly than incomes for the top 10%. As a result, trends in aggregate life satisfaction should not be seen as paradoxical: the income and standard of living of the typical US citizen have not grown much in the last couple of decades. (You can read more about this in our page on inequality and incomes across the distribution .)

Health and life satisfaction

Life expectancy and life satisfaction.

Health is an important predictor of life satisfaction, both within and among countries. In this visualization, we provide evidence of the cross-country relationship.

Each dot in the scatterplot represents one country. The vertical position of the dots shows national life expectancy at birth, and the horizontal position shows the national average self-reported life satisfaction in the Cantril Ladder (a scale ranging from 0-10, where 10 is the highest possible life satisfaction).

As we can see, there is a strong positive correlation: countries where people tend to live longer are also countries where people tend to say more often that they are satisfied with their lives. A similar relationship holds for other health outcomes (e.g., life satisfaction tends to be higher in countries with lower child mortality ).

The relationship plotted in the chart clearly reflects more than just the link between health and happiness since countries with high life expectancy also tend to be countries with many other distinct characteristics. However, the positive correlation between life expectancy and life satisfaction remains after controlling for observable country characteristics, such as income and social protection. You can read more about this in the World Happiness Report 2017 , specifically the discussion in Chapter 2.

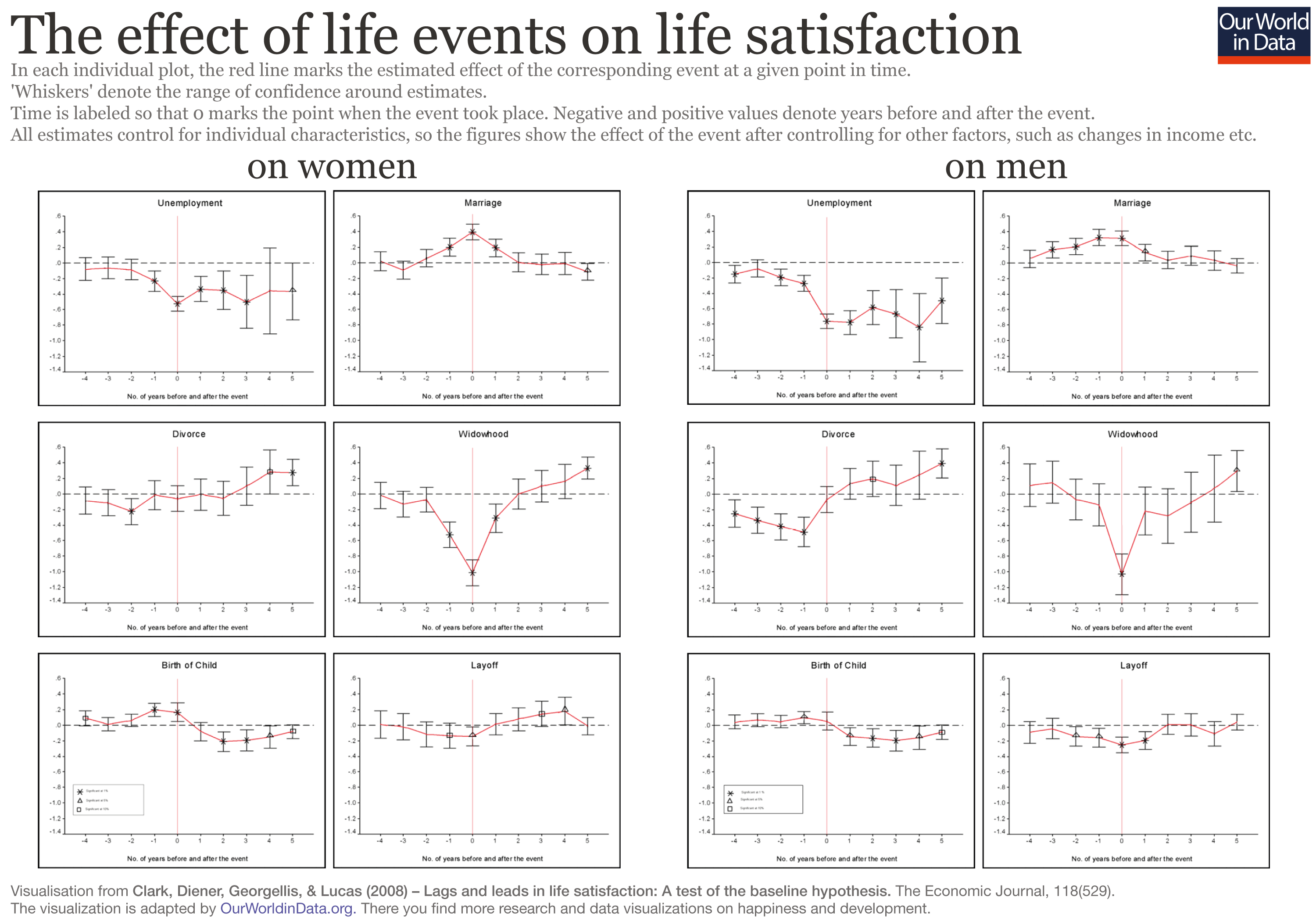

Life satisfaction through life events

How do common life events affect happiness.

Do people tend to adapt to common life events by converging back to a baseline level of happiness?

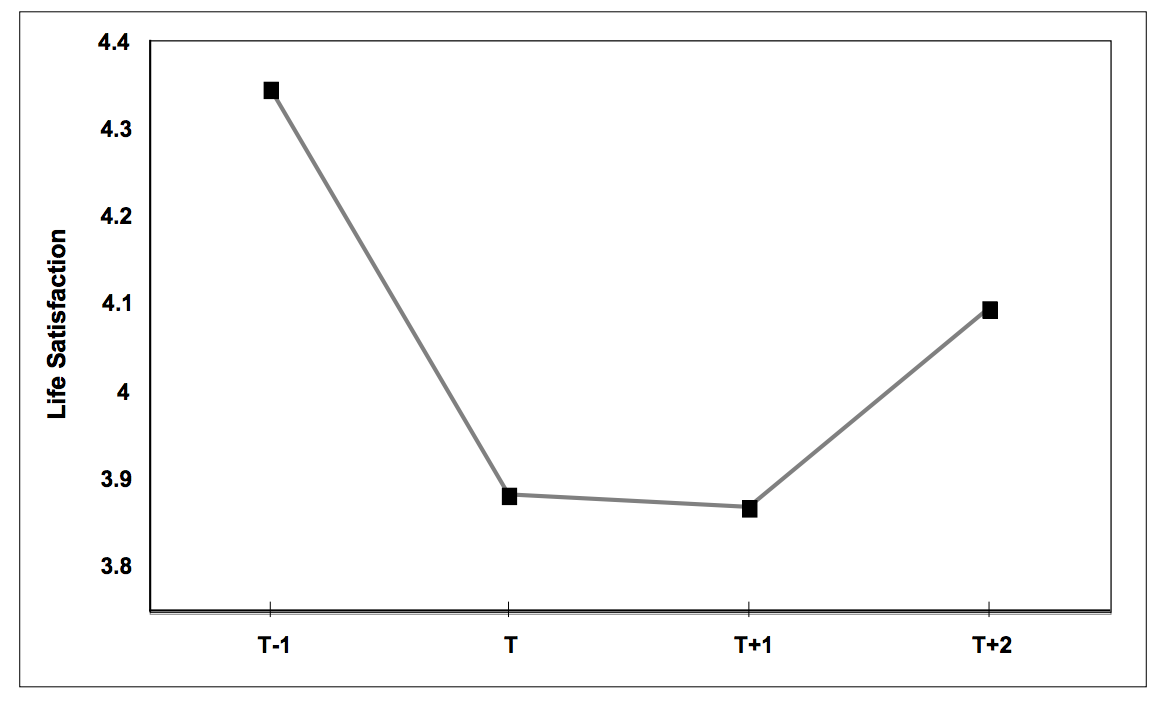

Clark et al. (2008) 12 use data from the German Socio-Economic Panel to identify groups of people experiencing significant life and labor market events and trace how these events affect the evolution of their life satisfaction. The visualization here shows an overview of their main findings. In each individual chart, the red lines mark the estimated effect of a different event at a given point in time (with ‘whiskers’ marking the range of confidence of each estimate).