- Search Menu

- Browse content in Arts and Humanities

- Browse content in Archaeology

- Archaeological Methodology and Techniques

- Biblical Archaeology

- Environmental Archaeology

- Historical Archaeology

- Landscape Archaeology

- Prehistoric Archaeology

- Browse content in Art

- History of Art

- Browse content in Classical Studies

- Classical History

- Classical Literature

- Greek and Roman Epigraphy

- Greek and Roman Archaeology

- Late Antiquity

- Religion in the Ancient World

- Browse content in History

- Colonialism and Imperialism

- Diplomatic History

- Historical Geography

- History by Period

- History of Gender and Sexuality

- Intellectual History

- Legal and Constitutional History

- Military History

- Political History

- Regional and National History

- Revolutions and Rebellions

- Slavery and Abolition of Slavery

- Social and Cultural History

- Theory, Methods, and Historiography

- World History

- Language Teaching and Learning

- Browse content in Linguistics

- Grammar, Syntax and Morphology

- Historical and Diachronic Linguistics

- Language Reference

- Language Variation

- Language Families

- Linguistic Anthropology

- Linguistic Theories

- Linguistic Typology

- Sociolinguistics

- Browse content in Literature

- Literary Studies (European)

- Literary Studies - World

- Literary Studies (1500 to 1800)

- Literary Studies (19th Century)

- Literary Studies (20th Century onwards)

- Literary Studies (British and Irish)

- Literary Studies (Early and Medieval)

- Literary Studies (Fiction, Novelists, and Prose Writers)

- Literary Studies (Poetry and Poets)

- Literary Studies (Travel Literature)

- Literary Studies (Women's Writing)

- Literary Theory and Cultural Studies

- Mythology and Folklore

- Browse content in Media Studies

- Browse content in Music

- Ethnomusicology

- Music Cultures

- Music and Culture

- Music Theory and Analysis

- Musical Structures, Styles, and Techniques

- Musicology and Music History

- Browse content in Philosophy

- History of Western Philosophy

- Metaphysics

- Philosophy of Science

- Philosophy of Mind

- Philosophy of Religion

- Philosophy of Mathematics and Logic

- Social and Political Philosophy

- Browse content in Religion

- Biblical Studies

- Christianity

- History of Religion

- Religion and Education

- Religion and Art, Literature, and Music

- Religious Studies

- Browse content in Society and Culture

- Cultural Studies

- Browse content in Law

- Constitutional and Administrative Law

- Criminal Law

- Environment and Energy Law

- Human Rights and Immigration

- Browse content in International Law

- Public International Law

- Legal System and Practice

- Browse content in Science and Mathematics

- Browse content in Psychology

- Cognitive Psychology

- Evolutionary Psychology

- Social Psychology

- Browse content in Social Sciences

- Browse content in Anthropology

- Regional Anthropology

- Social and Cultural Anthropology

- Criminology and Criminal Justice

- Browse content in Economics

- Economic History

- Economic Development and Growth

- Labour and Demographic Economics

- Browse content in Education

- Educational Strategies and Policy

- Browse content in Human Geography

- Political Geography

- Browse content in Politics

- Comparative Politics

- Conflict Politics

- Environmental Politics

- International Relations

- Political Philosophy

- Political Sociology

- Political Economy

- Political Theory

- UK Politics

- Browse content in Sociology

- Health, Illness, and Medicine

- Migration Studies

- Occupations, Professions, and Work

- Organizations

- Population and Demography

- Race and Ethnicity

- Social Movements and Social Change

- Social Research and Statistics

- Social Stratification, Inequality, and Mobility

- Sociology of Education

- Urban and Rural Studies

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Marxist History-writing for the Twenty-first Century

- Cite Icon Cite

Since 1989, there have been many claims that Marxist approaches to history are out of date, but history has not stopped, and historical change continues to need explanation. There is still plenty of space for structural analysis of how history in all periods develops, and a Marxism un-linked to the Soviet past offers to many the most rigorous of these approaches. This volume explores from a wide variety of perspectives what Marxism has done for history-writing, and what it can, or cannot, still do. Eight historians and social scientists give their perspectives, both from Marxist and from non-Marxist positions, on history and what role Marxist analysis has in it.

Signed in as

Institutional accounts.

- GoogleCrawler [DO NOT DELETE]

- Google Scholar Indexing

Personal account

- Sign in with email/username & password

- Get email alerts

- Save searches

- Purchase content

- Activate your purchase/trial code

Institutional access

- Sign in with a library card Sign in with username/password Recommend to your librarian

- Institutional account management

- Get help with access

Access to content on Oxford Academic is often provided through institutional subscriptions and purchases. If you are a member of an institution with an active account, you may be able to access content in one of the following ways:

IP based access

Typically, access is provided across an institutional network to a range of IP addresses. This authentication occurs automatically, and it is not possible to sign out of an IP authenticated account.

Sign in through your institution

Choose this option to get remote access when outside your institution. Shibboleth/Open Athens technology is used to provide single sign-on between your institution’s website and Oxford Academic.

- Click Sign in through your institution.

- Select your institution from the list provided, which will take you to your institution's website to sign in.

- When on the institution site, please use the credentials provided by your institution. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

- Following successful sign in, you will be returned to Oxford Academic.

If your institution is not listed or you cannot sign in to your institution’s website, please contact your librarian or administrator.

Sign in with a library card

Enter your library card number to sign in. If you cannot sign in, please contact your librarian.

Society Members

Society member access to a journal is achieved in one of the following ways:

Sign in through society site

Many societies offer single sign-on between the society website and Oxford Academic. If you see ‘Sign in through society site’ in the sign in pane within a journal:

- Click Sign in through society site.

- When on the society site, please use the credentials provided by that society. Do not use an Oxford Academic personal account.

If you do not have a society account or have forgotten your username or password, please contact your society.

Sign in using a personal account

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members. See below.

A personal account can be used to get email alerts, save searches, purchase content, and activate subscriptions.

Some societies use Oxford Academic personal accounts to provide access to their members.

Viewing your signed in accounts

Click the account icon in the top right to:

- View your signed in personal account and access account management features.

- View the institutional accounts that are providing access.

Signed in but can't access content

Oxford Academic is home to a wide variety of products. The institutional subscription may not cover the content that you are trying to access. If you believe you should have access to that content, please contact your librarian.

For librarians and administrators, your personal account also provides access to institutional account management. Here you will find options to view and activate subscriptions, manage institutional settings and access options, access usage statistics, and more.

Our books are available by subscription or purchase to libraries and institutions.

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Rights and permissions

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Marxist Historiography

A brief overview of marxist beliefs, development, and expansion., by heath skroch.

From the bloodshed of the Bolshevik Revolution to the fall of dynastic China, Marxist values have had a massive impact on the course of human history. This economic theory requires a deep understanding of social interactions. Marxist ideologies have their core in human interaction as well as the struggle between economic and social classes.

Karl Marx and Fredrich Engles

Karl Marx and Fredrich Engles were two German philosophers who lived in the 19th century. The two met in Cologne, Germany and would ultimately become close friends and partners with the goal of furthering the growing socialist movement. The two were instrumental in helping with the formation of the Communist League; and later at the second communist congress in London (1903) they drafted the Communist Manifesto. After this, the two continued to work towards the full implementation of their ideologies across Europe. The Revolutions of 1848, an attempt by the Germans to overthrow their authoritarian government, proved to be an opportunity for spreading their economic and political beliefs that ultimately failed along with the Revolutions themselves. The two continued publishing books on Marxism and spreading their thoughts until their deaths.

Marxist Beliefs

Marxist ideology is based on a Philosophical Anthropology, a theory of history, and an economic and political program. The core of this philosophy lies within the interaction between social and economic classes. Their original ideas were based in economic aspects of society in which they divided the population into the Bourgeoise, capitalists who owned the means of production, and the Proletariat, the working class who had no other means to survive than by selling their labor. It was the belief of Marx that the Bourgeoise was exploiting the Proletariat by making a profit from their labor. These two classes as well as their social and political arrangements are what encompass the “relations of production.” These relations are what make up the superstructure of society, that being the laws and governmental situations that allow the continuation of capitalism.

Although postmodernism did not appear untill the mid 20th century, when it comes to Historiography, Marxists adopt a structuralist view of society with certain elements of postmodernism. This can be seen firstly in the understanding that history is often written by the upper class of a society for specific purposes. These include justifying their position over the lower classes, or in the case of Marxist beliefs, to continue the capitalist system. In this way Marxist beliefs are extremely postmodernist as they question the biases and goals of those writing history. Marxist believe the upper class has created both history and the various structures contained within it.

Historiographical progressivism can be described as a belief that throughout history humanity has been on a gradual incline, in terms of development, towards an overall end goal. The way in which Marxism embodies this characteristic can be most clearly seen in actual Marxist texts. For example, in Marxist History of the World: From Neanderthals to Neoliberals Faulkner states: “For the last 5,000 years, ever since the Agricultural Revolution first made possible substantial accumulations of surplus wealth, humanity has been engaged in an uneven and uncertain ascent towards the abolition of want.” (Faulkner) In the case of Marxism, this end goal is the eradication of poverty under the capitalist system. The ultimate goal lies at the end of humanities linear progression through early economic systems such as feudalism and Mercantalism, to Capitalism, through Socialism, and finally culminating with Communism.

This Marxist progressivism ties together many historical events especially those having to do with class conflicts and developments in capitalism, in a way these can be seen as the “engine” of change. Many Marxist histories focus on the Mercantilist Revolution as the first “version” of capitalism. This is because it is marks the first time non-noble individuals could accumulate vast wealth and thus invest it. Through Marxist progressivism this singular even can be tied to all others having to do with the progression from capitalism to communism. In that way the invention of the mercantilist system is the predecessor of Industrialized Capitalism, Regulated Capitalism and especially of countries in the modern day that have socialist and even communist systems.

Marxism and Government

As previously stated, Marxism holds a certain degree of contempt for any capitalist society’s government. This can best be explained in Marx’s own words in the preface to his 1859 writing, A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy. Here he states: “Legal relation as well as forms of state are to be grasped neither by themselves nor from the so-called general development of the human mind, but rather have their roots in the material conditions of life…” Marx explains that it is the material conditions of life, otherwise known as the social and economic class are what ultimately shape the laws and government of a society. He then connects this to the writing of history saying, “Economic production and the structure of society uprising there from constitute the foundation for the political and intellectual history of that epoch…”

Problems around the writing of history, such as the purpose of writing and bias of the author, were nothing new; however, Marxist Historiography places this criticism at the core of its beliefs, going as far as to differentiate itself from “regular history’ by calling it “bourgeois history.” In this case Marxists assert that this “bourgeois history” is created by the government in order to justify the capitalist system. It is for this reason that for Marxists, non-Marxist historians should be, first and foremost, “denounced” as ‘falsifiers of history’—made positive evaluation of bourgeois authors dependent on their politics and on their affinity to an orthodox materialistic understanding of history. (Mogilnitsky, pg 414)

Karl Kautsky (1854-1938) was a Marxist theoretician who lived from the mid 19th century to the mid 20th century. Despite disapproval by Karl Marx, who used the word “mediocrity” to describe him, Kautsky was a leader within the Marxist community. He began his career as an editor for Marx working on such publications as Theories of Surplus Value . He did such an impressive job that he later became the editor of Marx’s estate after Fredrich Engles’ death. He was so effective at his job that he quickly became known as the most important theorists in the Marxist World; doing so much to popularize Marxism in the west that he earned the title “The Pope of Marxism.” Kautsky wouldn’t hold a high title in the Marxist party for long as several disagreements with Lenin over the Bolshevik rebellion and support of the first world war led to the end of his political career. It was due to his more available schedule that he would be able to write more philosophy and ultimately create a new branch of Marxism that is often called Kautskism.

Kautskism can be seen as a more strict adherence to the historiographical belief that society was ever progressing towards a lower class uprising. This originated from Kautsky’s claim that Russia was not ready for a socialist revolution as the country had never had an unrestricted capitalist economy. This embodies the linear history of his ideology as, in his opinion, a country couldn’t skip a step on the path to communism, especially if it surpassed his own. This view lead many critics of his time to label Kautsky as a “determinist” or “Darwinist.” Kautsky made sure to emphasize that his position was grounded in the human agency throughout history being the driving force behind the inevitable Proletarian uprising. Kautskism only slightly avoids the label of determinist in that it doesn’t advocate for “inevitable, linear history” but rather that the workers of the proletariat would eventually overthrow the upper class.

Marxism-Leninism

Almost the entire twentieth century of Russian History was defined by Marxism. This reign of Marxist ideology began in 1917 with the Bolshevik Revolution, (also known as the Russian Revolution) lead by Vladamir Lenin. This event is extremely important as it led to the rise of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR or Soviet Union). Lenin placed himself as dictator of this new government and pushed for the classic Marxist support of a proletarian democracy. Additionally, he pushed to nationalize banks and much of the Russian economy.

Shortly after Lenin’s death in 1924, Joseph Stalin rose to replace him as Soviet dictator. Propaganda under the new dictator became extremely common, all of which sought to justify Stalin’s position and Marxism as the correct ideology. With the use of a police state Stalin was able to nationalize agriculture and industrialize Russia; with the threat of death for all those who refused to comply. Additionally, Stalin pushed for rewrites of history, mythologizing his early life and increasing his role in the Bolshevik Revolution.

The importance of Marxism in Russia is that it served as the first place that the ideology could truly be tested. Furthermore, it allowed the ideology to spread with the expansion of the Soviet Union and its sphere of influence.

Marxist History in China

For the vast majority of history in China, dynastic monarchy was the only form of government. This system of government was shortly broken by the Republic of China from 1912-1949, before ultimately being succeeded by a communist state. Marxism greatly expanded in the two decades before the Chinese Communist revolution. Fan Wenlan lead the Marxist view of Chinese History, opposing historians who followed a more nationalist view. Firstly, Wenlan believed in the classic linear Marxist view of history, believing that the communist revolution would be the culmination of the centuries long struggle of the Chinese people against feudalism and imperialism. (Li, pg 272) Oddly enough, in a way the short period of The Republic of China was required for this linear history to work. In juxtaposition of Kautsky’s view of the Russian Marxist Revolution, China had fully experienced the “steps” to becoming a communist state.

After the success of the communist in the civil war, Fan Wenlan became the foremost authority on Chinese history; with his revolutionary narrative becoming the accepted story of Modern Chinese History. With the rise of Marxism, the nationalist viewpoint became known as “bourgeoise history.” Additionally, western powers began to be viewed as malicious for the various acts of violence committed under imperialist policies. The greatest of these was the opium wars, in which the Chinese attempted to stop the trade of Opium from European merchants; being easily defeated by the far more militarily advanced Western powers. These wars offered the perfect chance to highlight Marxist beliefs due to the corruption of the Chinese government at the time. Chinese Aristocrats worked with European Opium traders to make massive amounts of profit at the expense of the welfare of the Chinese population; even going as far as to oppose the legalization of opium in order to keep its price high. This allowed for the demonization of the Chinese government and acted as an example of the injustices suffered by the Proletariat from the Bourgeoise. Fan capitalized on this, citing it as another reason that the Marxist Revolution was inevitable.

Marxist History in Japan

With the close of the second World War, Japan found itself defeated and placed under military occupation by the United States. This occupation involved nearly one million Allied soldiers and present a fertile opportunity for Marxist enthusiasm to grow. When the occupation did finally end, many Marxists argued that American “colonization” had worsened under the system of capitalism and imperialism. They saw American influence as a negative, understanding themselves to be in the Proletariat position and the United States to be the Bourgeoise. Historians such as, Ishimoda Shô saw the solution to this external influence to be a strengthening of the “cultural core” of the Japanese people. This would hopefully lead to the country no longer having classes and being free from the influence of capitalism. The outbreak of the Korean war in 1950 increased anti-colonial fever in Asia which greatly boosted Marxist ideals.

Oddly enough, the recent Marxist revolution in China served as an example for the Japanese Marxist despite the Chinese Revolution being heavily driven by Japanese imperialism during World War II. (Gayle, pg 86) This strange colonizer and colonized relationship required Japanese Marxist historians to argue that the nation, comprised only of the people and their culture, was indeed separable from the state, or government.

Marxist Historiography stands at the core of Marx’s economic philosophy. With its view of linear history, social class structures, and almost prophetic view of the future Marxism continues to be relevant today. This way of viewing the past and thus preparing for the future can best be seen in communist societies; and those of socialist socialist economic systems which are understood to be “on the path to communism.” Its greatest impact is brining proletariat struggles to the forefront of modern thought. With many countries experiencing Marxism with various historians, the belief systems impact on the world continues to grow.

Bibliography

Blackledge, Paul, and School of Social Sciences. “Karl Kautsky and Marxist Historiography.” 1 Aug. 2006

Chalcraft, John T. “Pluralizing capital, challenging Eurocentrism: Toward post-Marxist historiography.” 2005.91 (2005): 13-39.

Faulkner, N. (2013). Marxist History of the World : From Neanderthals to Neoliberals.

Gayle, Curtis Anderson. Marxist History and Postwar Japanese Nationalism. 1st ed, 2002.

Irfan Habib. Problems of Marxist Historiography. 1988;16(12):3-13.

Li, Huaiyin, Between Tradition and Revolution: Fan Wenlan and the Origins of the Marxist Historiography of Modern China, 2010, 0097-7004

“Marxism.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica

Mogilnitsky, B. G. (1992). Non-Marxist Historiography of Today: The Evolution of Its Theoretical and Methodological Principles¹.

Nolte, Ernst. “The Relationship between ‘Bourgeois’ and ‘Marxist’ Historiography.” History and Theory

Wang, Q. “Marxist Historiographies: A Global Perspective.”

Zahoor, Muhammad Abrar, and Fakhar Bilal. “Marxist Historiography: An Analytical Exposition of Major Themes and Premises .” 2013.

Permalink: /essays/thematic/Marxist-Historiography.html

- Table of Contents

- New in this Archive

- Chronological

- Editorial Information

- About the SEP

- Editorial Board

- How to Cite the SEP

- Special Characters

- Support the SEP

- PDFs for SEP Friends

- Make a Donation

- SEPIA for Libraries

- Entry Contents

Bibliography

Academic tools.

- Friends PDF Preview

- Author and Citation Info

- Back to Top

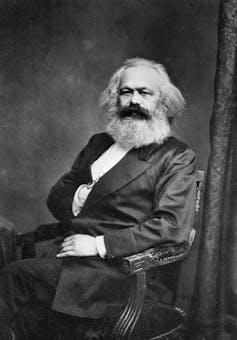

Karl Marx (1818–1883) is best known not as a philosopher but as a revolutionary, whose works inspired the foundation of many communist regimes in the twentieth century. It is hard to think of many who have had as much influence in the creation of the modern world. Trained as a philosopher, Marx turned away from philosophy in his mid-twenties, towards economics and politics. However, in addition to his overtly philosophical early work, his later writings have many points of contact with contemporary philosophical debates, especially in the philosophy of history and the social sciences, and in moral and political philosophy. Historical materialism — Marx’s theory of history — is centered around the idea that forms of society rise and fall as they further and then impede the development of human productive power. Marx sees the historical process as proceeding through a necessary series of modes of production, characterized by class struggle, culminating in communism. Marx’s economic analysis of capitalism is based on his version of the labour theory of value, and includes the analysis of capitalist profit as the extraction of surplus value from the exploited proletariat. The analysis of history and economics come together in Marx’s prediction of the inevitable economic breakdown of capitalism, to be replaced by communism. However Marx refused to speculate in detail about the nature of communism, arguing that it would arise through historical processes, and was not the realisation of a pre-determined moral ideal.

1. Marx’s Life and Works

- 2.1. On The Jewish Question

- 2.2. Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right: Introduction

- 2.3. 1844 Manuscripts

- 2.4. Theses on Feuerbach

3. Economics

4.1 the german ideology, 4.2 1859 preface, 4.3 functional explanation, 4.4 rationality, 4.5 alternative interpretations, 5. morality, other internet resources, related entries.

Karl Marx was born in Trier, in the German Rhineland, in 1818. Although his family was Jewish they converted to Christianity so that his father could pursue his career as a lawyer in the face of Prussia’s anti-Jewish laws. A precocious schoolchild, Marx studied law in Bonn and Berlin, and then wrote a PhD thesis in Philosophy, comparing the views of Democritus and Epicurus. On completion of his doctorate in 1841 Marx hoped for an academic job, but he had already fallen in with too radical a group of thinkers and there was no real prospect. Turning to journalism, Marx rapidly became involved in political and social issues, and soon found himself having to consider communist theory. Of his many early writings, four, in particular, stand out. ‘Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Introduction’, and ‘On The Jewish Question’, were both written in 1843 and published in the Deutsch-Französische Jahrbücher. The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts , written in Paris 1844, and the ‘Theses on Feuerbach’ of 1845, remained unpublished in Marx’s lifetime.

The German Ideology , co-written with Engels in 1845, was also unpublished but this is where we see Marx beginning to develop his theory of history. The Communist Manifesto is perhaps Marx’s most widely read work, even if it is not the best guide to his thought. This was again jointly written with Engels and published with a great sense of excitement as Marx returned to Germany from exile to take part in the revolution of 1848. With the failure of the revolution Marx moved to London where he remained for the rest of his life. He now concentrated on the study of economics, producing, in 1859, his Contribution to a Critique of Political Economy . This is largely remembered for its Preface, in which Marx sketches out what he calls ‘the guiding principles’ of his thought, on which many interpretations of historical materialism are based. Marx’s main economic work is, of course, Capital (Volume 1), published in 1867, although Volume 3, edited by Engels, and published posthumously in 1894, contains much of interest. Finally, the late pamphlet Critique of the Gotha Programme (1875) is an important source for Marx’s reflections on the nature and organisation of communist society.

The works so far mentioned amount only to a small fragment of Marx’s opus, which will eventually run to around 100 large volumes when his collected works are completed. However the items selected above form the most important core from the point of view of Marx’s connection with philosophy, although other works, such as the 18 th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852), are often regarded as equally important in assessing Marx’s analysis of concrete political events. In what follows, I shall concentrate on those texts and issues that have been given the greatest attention within the Anglo-American philosophical literature.

2. The Early Writings

The intellectual climate within which the young Marx worked was dominated by the influence of Hegel, and the reaction to Hegel by a group known as the Young Hegelians, who rejected what they regarded as the conservative implications of Hegel’s work. The most significant of these thinkers was Ludwig Feuerbach, who attempted to transform Hegel’s metaphysics, and, thereby, provided a critique of Hegel’s doctrine of religion and the state. A large portion of the philosophical content of Marx’s works written in the early 1840s is a record of his struggle to define his own position in reaction to that of Hegel and Feuerbach and those of the other Young Hegelians.

2.1 ‘On The Jewish Question’

In this text Marx begins to make clear the distance between himself and his radical liberal colleagues among the Young Hegelians; in particular Bruno Bauer. Bauer had recently written against Jewish emancipation, from an atheist perspective, arguing that the religion of both Jews and Christians was a barrier to emancipation. In responding to Bauer, Marx makes one of the most enduring arguments from his early writings, by means of introducing a distinction between political emancipation — essentially the grant of liberal rights and liberties — and human emancipation. Marx’s reply to Bauer is that political emancipation is perfectly compatible with the continued existence of religion, as the contemporary example of the United States demonstrates. However, pushing matters deeper, in an argument reinvented by innumerable critics of liberalism, Marx argues that not only is political emancipation insufficient to bring about human emancipation, it is in some sense also a barrier. Liberal rights and ideas of justice are premised on the idea that each of us needs protection from other human beings who are a threat to our liberty and security. Therefore liberal rights are rights of separation, designed to protect us from such perceived threats. Freedom on such a view, is freedom from interference. What this view overlooks is the possibility — for Marx, the fact — that real freedom is to be found positively in our relations with other people. It is to be found in human community, not in isolation. Accordingly, insisting on a regime of rights encourages us to view each other in ways that undermine the possibility of the real freedom we may find in human emancipation. Now we should be clear that Marx does not oppose political emancipation, for he sees that liberalism is a great improvement on the systems of feud and religious prejudice and discrimination which existed in the Germany of his day. Nevertheless, such politically emancipated liberalism must be transcended on the route to genuine human emancipation. Unfortunately, Marx never tells us what human emancipation is, although it is clear that it is closely related to the idea of non-alienated labour, which we will explore below.

2.2 ‘Contribution to a Critique of Hegel’s Philosophy of Right, Introduction’

This work is home to Marx’s notorious remark that religion is the ‘opiate of the people’, a harmful, illusion-generating painkiller, and it is here that Marx sets out his account of religion in most detail. Just as importantly Marx here also considers the question of how revolution might be achieved in Germany, and sets out the role of the proletariat in bringing about the emancipation of society as a whole.

With regard to religion, Marx fully accepted Feuerbach’s claim in opposition to traditional theology that human beings had invented God in their own image; indeed a view that long pre-dated Feuerbach. Feuerbach’s distinctive contribution was to argue that worshipping God diverted human beings from enjoying their own human powers. While accepting much of Feuerbach’s account Marx’s criticizes Feuerbach on the grounds that he has failed to understand why people fall into religious alienation and so is unable to explain how it can be transcended. Feuerbach’s view appears to be that belief in religion is purely an intellectual error and can be corrected by persuasion. Marx’s explanation is that religion is a response to alienation in material life, and therefore cannot be removed until human material life is emancipated, at which point religion will wither away. Precisely what it is about material life that creates religion is not set out with complete clarity. However, it seems that at least two aspects of alienation are responsible. One is alienated labour, which will be explored shortly. A second is the need for human beings to assert their communal essence. Whether or not we explicitly recognize it, human beings exist as a community, and what makes human life possible is our mutual dependence on the vast network of social and economic relations which engulf us all, even though this is rarely acknowledged in our day-to-day life. Marx’s view appears to be that we must, somehow or other, acknowledge our communal existence in our institutions. At first it is ‘deviously acknowledged’ by religion, which creates a false idea of a community in which we are all equal in the eyes of God. After the post-Reformation fragmentation of religion, where religion is no longer able to play the role even of a fake community of equals, the state fills this need by offering us the illusion of a community of citizens, all equal in the eyes of the law. Interestingly, the political liberal state, which is needed to manage the politics of religious diversity, takes on the role offered by religion in earlier times of providing a form of illusory community. But the state and religion will both be transcended when a genuine community of social and economic equals is created.

Of course we are owed an answer to the question how such a society could be created. It is interesting to read Marx here in the light of his third Thesis on Feuerbach where he criticises an alternative theory. The crude materialism of Robert Owen and others assumes that human beings are fully determined by their material circumstances, and therefore to bring about an emancipated society it is necessary and sufficient to make the right changes to those material circumstances. However, how are those circumstances to be changed? By an enlightened philanthropist like Owen who can miraculously break through the chain of determination which ties down everyone else? Marx’s response, in both the Theses and the Critique, is that the proletariat can break free only by their own self-transforming action. Indeed if they do not create the revolution for themselves — in alliance, of course, with the philosopher — they will not be fit to receive it.

2.3 Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts

The Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts cover a wide range of topics, including much interesting material on private property and communism, and on money, as well as developing Marx’s critique of Hegel. However, the manuscripts are best known for their account of alienated labour. Here Marx famously depicts the worker under capitalism as suffering from four types of alienated labour. First, from the product, which as soon as it is created is taken away from its producer. Second, in productive activity (work) which is experienced as a torment. Third, from species-being, for humans produce blindly and not in accordance with their truly human powers. Finally, from other human beings, where the relation of exchange replaces the satisfaction of mutual need. That these categories overlap in some respects is not a surprise given Marx’s remarkable methodological ambition in these writings. Essentially he attempts to apply a Hegelian deduction of categories to economics, trying to demonstrate that all the categories of bourgeois economics — wages, rent, exchange, profit, etc. — are ultimately derived from an analysis of the concept of alienation. Consequently each category of alienated labour is supposed to be deducible from the previous one. However, Marx gets no further than deducing categories of alienated labour from each other. Quite possibly in the course of writing he came to understand that a different methodology is required for approaching economic issues. Nevertheless we are left with a very rich text on the nature of alienated labour. The idea of non-alienation has to be inferred from the negative, with the assistance of one short passage at the end of the text ‘On James Mill’ in which non-alienated labour is briefly described in terms which emphasise both the immediate producer’s enjoyment of production as a confirmation of his or her powers, and also the idea that production is to meet the needs of others, thus confirming for both parties our human essence as mutual dependence. Both sides of our species essence are revealed here: our individual human powers and our membership in the human community.

It is important to understand that for Marx alienation is not merely a matter of subjective feeling, or confusion. The bridge between Marx’s early analysis of alienation and his later social theory is the idea that the alienated individual is ‘a plaything of alien forces’, albeit alien forces which are themselves a product of human action. In our daily lives we take decisions that have unintended consequences, which then combine to create large-scale social forces which may have an utterly unpredicted, and highly damaging, effect. In Marx’s view the institutions of capitalism — themselves the consequences of human behaviour — come back to structure our future behaviour, determining the possibilities of our action. For example, for as long as a capitalist intends to stay in business he must exploit his workers to the legal limit. Whether or not wracked by guilt the capitalist must act as a ruthless exploiter. Similarly the worker must take the best job on offer; there is simply no other sane option. But by doing this we reinforce the very structures that oppress us. The urge to transcend this condition, and to take collective control of our destiny — whatever that would mean in practice — is one of the motivating and sustaining elements of Marx’s social analysis.

2.4 ‘Theses on Feuerbach’

The Theses on Feuerbach contain one of Marx’s most memorable remarks: “the philosophers have only interpreted the world, the point is to change it” (thesis 11). However the eleven theses as a whole provide, in the compass of a couple of pages, a remarkable digest of Marx’s reaction to the philosophy of his day. Several of these have been touched on already (for example, the discussions of religion in theses 4, 6 and 7, and revolution in thesis 3) so here I will concentrate only on the first, most overtly philosophical, thesis.

In the first thesis Marx states his objections to ‘all hitherto existing’ materialism and idealism. Materialism is complimented for understanding the physical reality of the world, but is criticised for ignoring the active role of the human subject in creating the world we perceive. Idealism, at least as developed by Hegel, understands the active nature of the human subject, but confines it to thought or contemplation: the world is created through the categories we impose upon it. Marx combines the insights of both traditions to propose a view in which human beings do indeed create — or at least transform — the world they find themselves in, but this transformation happens not in thought but through actual material activity; not through the imposition of sublime concepts but through the sweat of their brow, with picks and shovels. This historical version of materialism, which transcends and thus rejects all existing philosophical thought, is the foundation of Marx’s later theory of history. As Marx puts it in the 1844 Manuscripts, ‘Industry is the real historical relationship of nature … to man’. This thought, derived from reflection on the history of philosophy, together with his experience of social and economic realities, as a journalist, sets the agenda for all Marx’s future work.

Capital Volume 1 begins with an analysis of the idea of commodity production. A commodity is defined as a useful external object, produced for exchange on a market. Thus two necessary conditions for commodity production are the existence of a market, in which exchange can take place, and a social division of labour, in which different people produce different products, without which there would be no motivation for exchange. Marx suggests that commodities have both use-value — a use, in other words — and an exchange-value — initially to be understood as their price. Use value can easily be understood, so Marx says, but he insists that exchange value is a puzzling phenomenon, and relative exchange values need to be explained. Why does a quantity of one commodity exchange for a given quantity of another commodity? His explanation is in terms of the labour input required to produce the commodity, or rather, the socially necessary labour, which is labour exerted at the average level of intensity and productivity for that branch of activity within the economy. Thus the labour theory of value asserts that the value of a commodity is determined by the quantity of socially necessary labour time required to produce it. Marx provides a two stage argument for the labour theory of value. The first stage is to argue that if two objects can be compared in the sense of being put on either side of an equals sign, then there must be a ‘third thing of identical magnitude in both of them’ to which they are both reducible. As commodities can be exchanged against each other, there must, Marx argues, be a third thing that they have in common. This then motivates the second stage, which is a search for the appropriate ‘third thing’, which is labour in Marx’s view, as the only plausible common element. Both steps of the argument are, of course, highly contestable.

Capitalism is distinctive, Marx argues, in that it involves not merely the exchange of commodities, but the advancement of capital, in the form of money, with the purpose of generating profit through the purchase of commodities and their transformation into other commodities which can command a higher price, and thus yield a profit. Marx claims that no previous theorist has been able adequately to explain how capitalism as a whole can make a profit. Marx’s own solution relies on the idea of exploitation of the worker. In setting up conditions of production the capitalist purchases the worker’s labour power — his ability to labour — for the day. The cost of this commodity is determined in the same way as the cost of every other; i.e. in terms of the amount of socially necessary labour power required to produce it. In this case the value of a day’s labour power is the value of the commodities necessary to keep the worker alive for a day. Suppose that such commodities take four hours to produce. Thus the first four hours of the working day is spent on producing value equivalent to the value of the wages the worker will be paid. This is known as necessary labour. Any work the worker does above this is known as surplus labour, producing surplus value for the capitalist. Surplus value, according to Marx, is the source of all profit. In Marx’s analysis labour power is the only commodity which can produce more value than it is worth, and for this reason it is known as variable capital. Other commodities simply pass their value on to the finished commodities, but do not create any extra value. They are known as constant capital. Profit, then, is the result of the labour performed by the worker beyond that necessary to create the value of his or her wages. This is the surplus value theory of profit.

It appears to follow from this analysis that as industry becomes more mechanised, using more constant capital and less variable capital, the rate of profit ought to fall. For as a proportion less capital will be advanced on labour, and only labour can create value. In Capital Volume 3 Marx does indeed make the prediction that the rate of profit will fall over time, and this is one of the factors which leads to the downfall of capitalism. (However, as pointed out by Marx’s able expositor Paul Sweezy in The Theory of Capitalist Development , the analysis is problematic.) A further consequence of this analysis is a difficulty for the theory that Marx did recognise, and tried, albeit unsuccessfully, to meet also in Capital Volume 3. It follows from the analysis so far that labour intensive industries ought to have a higher rate of profit than those which use less labour. Not only is this empirically false, it is theoretically unacceptable. Accordingly, Marx argued that in real economic life prices vary in a systematic way from values. Providing the mathematics to explain this is known as the transformation problem, and Marx’s own attempt suffers from technical difficulties. Although there are known techniques for solving this problem now (albeit with unwelcome side consequences), we should recall that the labour theory of value was initially motivated as an intuitively plausible theory of price. But when the connection between price and value is rendered as indirect as it is in the final theory, the intuitive motivation of the theory drains away. A further objection is that Marx’s assertion that only labour can create surplus value is unsupported by any argument or analysis, and can be argued to be merely an artifact of the nature of his presentation. Any commodity can be picked to play a similar role. Consequently with equal justification one could set out a corn theory of value, arguing that corn has the unique power of creating more value than it costs. Formally this would be identical to the labour theory of value. Nevertheless, the claims that somehow labour is responsible for the creation of value, and that profit is the consequence of exploitation, remain intuitively powerful, even if they are difficult to establish in detail.

However, even if the labour theory of value is considered discredited, there are elements of his theory that remain of worth. The Cambridge economist Joan Robinson, in An Essay on Marxian Economics , picked out two aspects of particular note. First, Marx’s refusal to accept that capitalism involves a harmony of interests between worker and capitalist, replacing this with a class based analysis of the worker’s struggle for better wages and conditions of work, versus the capitalist’s drive for ever greater profits. Second, Marx’s denial that there is any long-run tendency to equilibrium in the market, and his descriptions of mechanisms which underlie the trade-cycle of boom and bust. Both provide a salutary corrective to aspects of orthodox economic theory.

4. Theory of History

Marx did not set out his theory of history in great detail. Accordingly, it has to be constructed from a variety of texts, both those where he attempts to apply a theoretical analysis to past and future historical events, and those of a more purely theoretical nature. Of the latter, the 1859 Preface to A Critique of Political Economy has achieved canonical status. However, The German Ideology , co-written with Engels in 1845, is a vital early source in which Marx first sets out the basics of the outlook of historical materialism. We shall briefly outline both texts, and then look at the reconstruction of Marx’s theory of history in the hands of his philosophically most influential recent exponent, G.A. Cohen, who builds on the interpretation of the early Russian Marxist Plekhanov.

We should, however, be aware that Cohen’s interpretation is not universally accepted. Cohen provided his reconstruction of Marx partly because he was frustrated with existing Hegelian-inspired ‘dialectical’ interpretations of Marx, and what he considered to be the vagueness of the influential works of Louis Althusser, neither of which, he felt, provided a rigorous account of Marx’s views. However, some scholars believe that the interpretation that we shall focus on is faulty precisely for its lack of attention to the dialectic. One aspect of this criticism is that Cohen’s understanding has a surprisingly small role for the concept of class struggle, which is often felt to be central to Marx’s theory of history. Cohen’s explanation for this is that the 1859 Preface, on which his interpretation is based, does not give a prominent role to class struggle, and indeed it is not explicitly mentioned. Yet this reasoning is problematic for it is possible that Marx did not want to write in a manner that would engage the concerns of the police censor, and, indeed, a reader aware of the context may be able to detect an implicit reference to class struggle through the inclusion of such phrases as “then begins an era of social revolution,” and “the ideological forms in which men become conscious of this conflict and fight it out”. Hence it does not follow that Marx himself thought that the concept of class struggle was relatively unimportant. Furthermore, when A Critique of Political Economy was replaced by Capital , Marx made no attempt to keep the 1859 Preface in print, and its content is reproduced just as a very much abridged footnote in Capital . Nevertheless we shall concentrate here on Cohen’s interpretation as no other account has been set out with comparable rigour, precision and detail.

In The German Ideology Marx and Engels contrast their new materialist method with the idealism that had characterised previous German thought. Accordingly, they take pains to set out the ‘premises of the materialist method’. They start, they say, from ‘real human beings’, emphasising that human beings are essentially productive, in that they must produce their means of subsistence in order to satisfy their material needs. The satisfaction of needs engenders new needs of both a material and social kind, and forms of society arise corresponding to the state of development of human productive forces. Material life determines, or at least ‘conditions’ social life, and so the primary direction of social explanation is from material production to social forms, and thence to forms of consciousness. As the material means of production develop, ‘modes of co-operation’ or economic structures rise and fall, and eventually communism will become a real possibility once the plight of the workers and their awareness of an alternative motivates them sufficiently to become revolutionaries.

In the sketch of The German Ideology , all the key elements of historical materialism are present, even if the terminology is not yet that of Marx’s more mature writings. Marx’s statement in 1859 Preface renders much the same view in sharper form. Cohen’s reconstruction of Marx’s view in the Preface begins from what Cohen calls the Development Thesis, which is pre-supposed, rather than explicitly stated in the Preface. This is the thesis that the productive forces tend to develop, in the sense of becoming more powerful, over time. This states not that they always do develop, but that there is a tendency for them to do so. The productive forces are the means of production, together with productively applicable knowledge: technology, in other words. The next thesis is the primacy thesis, which has two aspects. The first states that the nature of the economic structure is explained by the level of development of the productive forces, and the second that the nature of the superstructure — the political and legal institutions of society— is explained by the nature of the economic structure. The nature of a society’s ideology, which is to say the religious, artistic, moral and philosophical beliefs contained within society, is also explained in terms of its economic structure, although this receives less emphasis in Cohen’s interpretation. Indeed many activities may well combine aspects of both the superstructure and ideology: a religion is constituted by both institutions and a set of beliefs.

Revolution and epoch change is understood as the consequence of an economic structure no longer being able to continue to develop the forces of production. At this point the development of the productive forces is said to be fettered, and, according to the theory once an economic structure fetters development it will be revolutionised — ‘burst asunder’ — and eventually replaced with an economic structure better suited to preside over the continued development of the forces of production.

In outline, then, the theory has a pleasing simplicity and power. It seems plausible that human productive power develops over time, and plausible too that economic structures exist for as long as they develop the productive forces, but will be replaced when they are no longer capable of doing this. Yet severe problems emerge when we attempt to put more flesh on these bones.

Prior to Cohen’s work, historical materialism had not been regarded as a coherent view within English-language political philosophy. The antipathy is well summed up with the closing words of H.B. Acton’s The Illusion of the Epoch : “Marxism is a philosophical farrago”. One difficulty taken particularly seriously by Cohen is an alleged inconsistency between the explanatory primacy of the forces of production, and certain claims made elsewhere by Marx which appear to give the economic structure primacy in explaining the development of the productive forces. For example, in The Communist Manifesto Marx states that: ‘The bourgeoisie cannot exist without constantly revolutionising the instruments of production.’ This appears to give causal and explanatory primacy to the economic structure — capitalism — which brings about the development of the forces of production. Cohen accepts that, on the surface at least, this generates a contradiction. Both the economic structure and the development of the productive forces seem to have explanatory priority over each other.

Unsatisfied by such vague resolutions as ‘determination in the last instance’, or the idea of ‘dialectical’ connections, Cohen self-consciously attempts to apply the standards of clarity and rigour of analytic philosophy to provide a reconstructed version of historical materialism.

The key theoretical innovation is to appeal to the notion of functional explanation (also sometimes called ‘consequence explanation’). The essential move is cheerfully to admit that the economic structure does indeed develop the productive forces, but to add that this, according to the theory, is precisely why we have capitalism (when we do). That is, if capitalism failed to develop the productive forces it would disappear. And, indeed, this fits beautifully with historical materialism. For Marx asserts that when an economic structure fails to develop the productive forces — when it ‘fetters’ the productive forces — it will be revolutionised and the epoch will change. So the idea of ‘fettering’ becomes the counterpart to the theory of functional explanation. Essentially fettering is what happens when the economic structure becomes dysfunctional.

Now it is apparent that this renders historical materialism consistent. Yet there is a question as to whether it is at too high a price. For we must ask whether functional explanation is a coherent methodological device. The problem is that we can ask what it is that makes it the case that an economic structure will only persist for as long as it develops the productive forces. Jon Elster has pressed this criticism against Cohen very hard. If we were to argue that there is an agent guiding history who has the purpose that the productive forces should be developed as much as possible then it would make sense that such an agent would intervene in history to carry out this purpose by selecting the economic structures which do the best job. However, it is clear that Marx makes no such metaphysical assumptions. Elster is very critical — sometimes of Marx, sometimes of Cohen — of the idea of appealing to ‘purposes’ in history without those being the purposes of anyone.

Cohen is well aware of this difficulty, but defends the use of functional explanation by comparing its use in historical materialism with its use in evolutionary biology. In contemporary biology it is commonplace to explain the existence of the stripes of a tiger, or the hollow bones of a bird, by pointing to the function of these features. Here we have apparent purposes which are not the purposes of anyone. The obvious counter, however, is that in evolutionary biology we can provide a causal story to underpin these functional explanations; a story involving chance variation and survival of the fittest. Therefore these functional explanations are sustained by a complex causal feedback loop in which dysfunctional elements tend to be filtered out in competition with better functioning elements. Cohen calls such background accounts ‘elaborations’ and he concedes that functional explanations are in need of elaborations. But he points out that standard causal explanations are equally in need of elaborations. We might, for example, be satisfied with the explanation that the vase broke because it was dropped on the floor, but a great deal of further information is needed to explain why this explanation works. Consequently, Cohen claims that we can be justified in offering a functional explanation even when we are in ignorance of its elaboration. Indeed, even in biology detailed causal elaborations of functional explanations have been available only relatively recently. Prior to Darwin, or arguably Lamark, the only candidate causal elaboration was to appeal to God’s purposes. Darwin outlined a very plausible mechanism, but having no genetic theory was not able to elaborate it into a detailed account. Our knowledge remains incomplete to this day. Nevertheless, it seems perfectly reasonable to say that birds have hollow bones in order to facilitate flight. Cohen’s point is that the weight of evidence that organisms are adapted to their environment would permit even a pre-Darwinian atheist to assert this functional explanation with justification. Hence one can be justified in offering a functional explanation even in absence of a candidate elaboration: if there is sufficient weight of inductive evidence.

At this point the issue, then, divides into a theoretical question and an empirical one. The empirical question is whether or not there is evidence that forms of society exist only for as long as they advance productive power, and are replaced by revolution when they fail. Here, one must admit, the empirical record is patchy at best, and there appear to have been long periods of stagnation, even regression, when dysfunctional economic structures were not revolutionised.

The theoretical issue is whether a plausible elaborating explanation is available to underpin Marxist functional explanations. Here there is something of a dilemma. In the first instance it is tempting to try to mimic the elaboration given in the Darwinian story, and appeal to chance variations and survival of the fittest. In this case ‘fittest’ would mean ‘most able to preside over the development of the productive forces’. Chance variation would be a matter of people trying out new types of economic relations. On this account new economic structures begin through experiment, but thrive and persist through their success in developing the productive forces. However the problem is that such an account would seem to introduce a larger element of contingency than Marx seeks, for it is essential to Marx’s thought that one should be able to predict the eventual arrival of communism. Within Darwinian theory there is no warrant for long-term predictions, for everything depends on the contingencies of particular situations. A similar heavy element of contingency would be inherited by a form of historical materialism developed by analogy with evolutionary biology. The dilemma, then, is that the best model for developing the theory makes predictions based on the theory unsound, yet the whole point of the theory is predictive. Hence one must either look for an alternative means of producing elaborating explanation, or give up the predictive ambitions of the theory.

The driving force of history, in Cohen’s reconstruction of Marx, is the development of the productive forces, the most important of which is technology. But what is it that drives such development? Ultimately, in Cohen’s account, it is human rationality. Human beings have the ingenuity to apply themselves to develop means to address the scarcity they find. This on the face of it seems very reasonable. Yet there are difficulties. As Cohen himself acknowledges, societies do not always do what would be rational for an individual to do. Co-ordination problems may stand in our way, and there may be structural barriers. Furthermore, it is relatively rare for those who introduce new technologies to be motivated by the need to address scarcity. Rather, under capitalism, the profit motive is the key. Of course it might be argued that this is the social form that the material need to address scarcity takes under capitalism. But still one may raise the question whether the need to address scarcity always has the influence that it appears to have taken on in modern times. For example, a ruling class’s absolute determination to hold on to power may have led to economically stagnant societies. Alternatively, it might be thought that a society may put religion or the protection of traditional ways of life ahead of economic needs. This goes to the heart of Marx’s theory that man is an essentially productive being and that the locus of interaction with the world is industry. As Cohen himself later argued in essays such as ‘Reconsidering Historical Materialism’, the emphasis on production may appear one-sided, and ignore other powerful elements in human nature. Such a criticism chimes with a criticism from the previous section; that the historical record may not, in fact, display the tendency to growth in the productive forces assumed by the theory.

Many defenders of Marx will argue that the problems stated are problems for Cohen’s interpretation of Marx, rather than for Marx himself. It is possible to argue, for example, that Marx did not have a general theory of history, but rather was a social scientist observing and encouraging the transformation of capitalism into communism as a singular event. And it is certainly true that when Marx analyses a particular historical episode, as he does in the 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon , any idea of fitting events into a fixed pattern of history seems very far from Marx’s mind. On other views Marx did have a general theory of history but it is far more flexible and less determinate than Cohen insists (Miller). And finally, as noted, there are critics who believe that Cohen’s interpretation is entirely wrong-headed (Sayers).

The issue of Marx and morality poses a conundrum. On reading Marx’s works at all periods of his life, there appears to be the strongest possible distaste towards bourgeois capitalist society, and an undoubted endorsement of future communist society. Yet the terms of this antipathy and endorsement are far from clear. Despite expectations, Marx never says that capitalism is unjust. Neither does he say that communism would be a just form of society. In fact he takes pains to distance himself from those who engage in a discourse of justice, and makes a conscious attempt to exclude direct moral commentary in his own works. The puzzle is why this should be, given the weight of indirect moral commentary one finds.

There are, initially, separate questions, concerning Marx’s attitude to capitalism and to communism. There are also separate questions concerning his attitude to ideas of justice, and to ideas of morality more broadly concerned. This, then, generates four questions: (1) Did Marx think capitalism unjust?; (2) did he think that capitalism could be morally criticised on other grounds?; (3) did he think that communism would be just? (4) did he think it could be morally approved of on other grounds? These are the questions we shall consider in this section.

The initial argument that Marx must have thought that capitalism is unjust is based on the observation that Marx argued that all capitalist profit is ultimately derived from the exploitation of the worker. Capitalism’s dirty secret is that it is not a realm of harmony and mutual benefit but a system in which one class systematically extracts profit from another. How could this fail to be unjust? Yet it is notable that Marx never concludes this, and in Capital he goes as far as to say that such exchange is ‘by no means an injustice’.

Allen Wood has argued that Marx took this approach because his general theoretical approach excludes any trans-epochal standpoint from which one can comment on the justice of an economic system. Even though one can criticize particular behaviour from within an economic structure as unjust (and theft under capitalism would be an example) it is not possible to criticise capitalism as a whole. This is a consequence of Marx’s analysis of the role of ideas of justice from within historical materialism. That is to say, juridical institutions are part of the superstructure, and ideas of justice are ideological, and the role of both the superstructure and ideology, in the functionalist reading of historical materialism adopted here, is to stabilise the economic structure. Consequently, to state that something is just under capitalism is simply a judgement applied to those elements of the system that will tend to have the effect of advancing capitalism. According to Marx, in any society the ruling ideas are those of the ruling class; the core of the theory of ideology.

Ziyad Husami, however, argues that Wood is mistaken, ignoring the fact that for Marx ideas undergo a double determination in that the ideas of the non-ruling class may be very different from those of the ruling class. Of course it is the ideas of the ruling class that receive attention and implementation, but this does not mean that other ideas do not exist. Husami goes as far as to argue that members of the proletariat under capitalism have an account of justice which matches communism. From this privileged standpoint of the proletariat, which is also Marx’s standpoint, capitalism is unjust, and so it follows that Marx thought capitalism unjust.

Plausible though it may sound, Husami’s argument fails to account for two related points. First, it cannot explain why Marx never described capitalism as unjust, and second, it does not account for the distance Marx wanted to place between his own scientific socialism, and that of the utopian socialists who argued for the injustice of capitalism. Hence one cannot avoid the conclusion that the ‘official’ view of Marx is that capitalism is not unjust.

Nevertheless, this leaves us with a puzzle. Much of Marx’s description of capitalism — his use of the words ‘embezzlement’, ‘robbery’ and ‘exploitation’ — belie the official account. Arguably, the only satisfactory way of understanding this issue is, once more, from G.A. Cohen, who proposes that Marx believed that capitalism was unjust, but did not believe that he believed it was unjust (Cohen 1983). In other words, Marx, like so many of us, did not have perfect knowledge of his own mind. In his explicit reflections on the justice of capitalism he was able to maintain his official view. But in less guarded moments his real view slips out, even if never in explicit language. Such an interpretation is bound to be controversial, but it makes good sense of the texts.

Whatever one concludes on the question of whether Marx thought capitalism unjust, it is, nevertheless, obvious that Marx thought that capitalism was not the best way for human beings to live. Points made in his early writings remain present throughout his writings, if no longer connected to an explicit theory of alienation. The worker finds work a torment, suffers poverty, overwork and lack of fulfillment and freedom. People do not relate to each other as humans should.

Does this amount to a moral criticism of capitalism or not? In the absence of any special reason to argue otherwise, it simply seems obvious that Marx’s critique is a moral one. Capitalism impedes human flourishing.

Marx, though, once more refrained from making this explicit; he seemed to show no interest in locating his criticism of capitalism in any of the traditions of moral philosophy, or explaining how he was generating a new tradition. There may have been two reasons for his caution. The first was that while there were bad things about capitalism, there is, from a world historical point of view, much good about it too. For without capitalism, communism would not be possible. Capitalism is to be transcended, not abolished, and this may be difficult to convey in the terms of moral philosophy.

Second, and perhaps more importantly, we need to return to the contrast between scientific and utopian socialism. The utopians appealed to universal ideas of truth and justice to defend their proposed schemes, and their theory of transition was based on the idea that appealing to moral sensibilities would be the best, perhaps only, way of bringing about the new chosen society. Marx wanted to distance himself from this tradition of utopian thought, and the key point of distinction was to argue that the route to understanding the possibilities of human emancipation lay in the analysis of historical and social forces, not in morality. Hence, for Marx, any appeal to morality was theoretically a backward step.

This leads us now to Marx’s assessment of communism. Would communism be a just society? In considering Marx’s attitude to communism and justice there are really only two viable possibilities: either he thought that communism would be a just society or he thought that the concept of justice would not apply: that communism would transcend justice.

Communism is described by Marx, in the Critique of the Gotha Programme , as a society in which each person should contribute according to their ability and receive according to their need. This certainly sounds like a theory of justice, and could be adopted as such. However it is possibly truer to Marx’s thought to say that this is part of an account in which communism transcends justice, as Lukes has argued.

If we start with the idea that the point of ideas of justice is to resolve disputes, then a society without disputes would have no need or place for justice. We can see this by reflecting upon Hume’s idea of the circumstances of justice. Hume argued that if there was enormous material abundance — if everyone could have whatever they wanted without invading another’s share — we would never have devised rules of justice. And, of course, Marx often suggested that communism would be a society of such abundance. But Hume also suggested that justice would not be needed in other circumstances; if there were complete fellow-feeling between all human beings. Again there would be no conflict and no need for justice. Of course, one can argue whether either material abundance or human fellow-feeling to this degree would be possible, but the point is that both arguments give a clear sense in which communism transcends justice.

Nevertheless we remain with the question of whether Marx thought that communism could be commended on other moral grounds. On a broad understanding, in which morality, or perhaps better to say ethics, is concerning with the idea of living well, it seems that communism can be assessed favourably in this light. One compelling argument is that Marx’s career simply makes no sense unless we can attribute such a belief to him. But beyond this we can be brief in that the considerations adduced in section 2 above apply again. Communism clearly advances human flourishing, in Marx’s view. The only reason for denying that, in Marx’s vision, it would amount to a good society is a theoretical antipathy to the word ‘good’. And here the main point is that, in Marx’s view, communism would not be brought about by high-minded benefactors of humanity. Quite possibly his determination to retain this point of difference between himself and the Utopian socialists led him to disparage the importance of morality to a degree that goes beyond the call of theoretical necessity.

Primary Literature

- Marx, Karl and Friedrich Engels, Gesamtausgabe (MEGA), Berlin, 1975–.

- –––, Collected Works , New York and London: International Publishers. 1975.

- –––, Selected Works , 2 Volumes, Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1962.

- Marx, Karl, Karl Marx: Selected Writings , 2 nd edition, David McLellan (ed.), Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2000.

Secondary Literature

See McLellan 1973 and Wheen 1999 for biographies of Marx, and see Singer 2000 and Wolff 2002 for general introductions.

- Acton, H.B., 1955, The Illusion of the Epoch , London: Cohen and West.

- Althusser, Louis, 1969, For Marx , London: Penguin.

- Althusser, Louis, and Balibar, Etienne, 1970, Reading Capital , London: NLB.

- Arthur, C.J., 1986, Dialectics of Labour , Oxford: Basil Blackwell.

- Avineri, Shlomo, 1970, The Social and Political Thought of Karl Marx , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bottomore, Tom (ed.), 1979, Karl Marx , Oxford: Blackwell.

- Brudney, Daniel, 1998, Marx’s Attempt to Leave Philosophy . Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Carver, Terrell, 1982, Marx’s Social Theory , New York: Oxford University Press.

- Carver, Terrell (ed.), 1991, The Cambridge Companion to Marx , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carver, Terrell, 1998, The Post-Modern Marx , Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Cohen, Joshua, 1982, ‘Review of G.A. Cohen, Karl Marx’s Theory of History ’, Journal of Philosophy , 79: 253–273.

- Cohen, G.A., 1983, ‘Review of Allen Wood, Karl Marx ’, Mind , 92: 440–445.

- Cohen, G.A., 1988, History, Labour and Freedom , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Cohen, G.A., 2001, Karl Marx’s Theory of History: A Defence , 2nd edition, Oxford, Oxford University Press.

- Desai, Megnad, 2002, Marx’s Revenge , London: Verso.

- Elster, Jon, 1985, Making Sense of Marx, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Geras, Norman, 1989, ‘The Controversy about Marx and Justice,’ in A. Callinicos (ed.), Marxist Theory , Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1989.

- Hook, Sidney, 1950, From Hegel to Marx , New York: Humanities Press.

- Husami, Ziyad, 1978, ‘Marx on Distributive Justice’, Philosophy and Public Affairs , 8: 27–64.

- Kamenka, Eugene, 1962, The Ethical Foundations of Marxism London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Kolakowski, Leszek, 1978, Main Currents of Marxism , 3 volumes, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Leopold, David, 2007, The Young Karl Marx , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lukes, Stephen, 1987, Marxism and Morality , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Maguire, John, 1972, Marx’s Paris Writings , Dublin: Gill and Macmillan.

- McLellan, David, 1970, Marx Before Marxism , London: Macmillan.

- McLellan, David, 1973, Karl Marx: His Life and Thought , London: Macmillan.

- Miller, Richard, 1984, Analyzing Marx , Princeton NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Peffer, Rodney, 1990, Marxism, Morality and Social Justice , Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Plekhanov, G.V., (1947 [1895]), The Development of the Monist View of History London: Lawrence and Wishart.

- Robinson, Joan, 1942, An Essay on Marxian Economics , London: Macmillan.

- Roemer, John, 1982, A General Theory of Exploitation and Class , Cambridge Ma.: Harvard University Press.

- Roemer, John (ed.), 1986, Analytical Marxism , Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Rosen, Michael, 1996, On Voluntary Servitude , Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Sayers, Sean, 1990, ‘Marxism and the Dialectical Method: A Critique of G.A. Cohen’, in S.Sayers (ed.), Socialism, Feminism and Philosophy: A Radical Philosophy Reader , London: Routledge.

- Singer, Peter, 2000, Marx: A Very Short Introduction , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Sober, E., Levine, A., and Wright, E.O. 1992, Reconstructing Marx , London: Verso.

- Sweezy, Paul, 1942 [1970], The Theory of Capitalist Development , New York: Monthly Review Press.

- Wheen, Francis, 1999, Karl Marx , London: Fourth Estate.

- Wolff, Jonathan, 2002, Why Read Marx Today? , Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wolff, Robert Paul, 1984, Understanding Marx , Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Wood, Allen, 1981, Karl Marx , London: Routledge; second edition, 2004.

- Wood, Allen, 1972, ‘The Marxian Critique of Justice’, Philosophy and Public Affairs , 1: 244–82.

How to cite this entry . Preview the PDF version of this entry at the Friends of the SEP Society . Look up this entry topic at the Indiana Philosophy Ontology Project (InPhO). Enhanced bibliography for this entry at PhilPapers , with links to its database.

- Marxists Internet Archive

Bauer, Bruno | Feuerbach, Ludwig Andreas | Hegel, Georg Wilhelm Friedrich | history, philosophy of