- Advanced search

Advanced Search

National Dental Hygiene Research Agenda

- Figures & Data

- Info & Metrics

- Introduction

A profession involves the acquisition of knowledge and skills in a unique area through formal training. A discipline is a branch of knowledge studied and expanded through higher education and research, while a profession consists of persons educated in the discipline according to nationally regulated, defined and monitored standards. 1 The regulation of a profession and establishment of clinical standards are important aspects of the social contract between a profession and the society it serves.

The American Dental Hygienists' Association (ADHA) acknowledges the importance of a body of research unique to dental hygiene in defining it as a profession and developing it into a discipline. The aim of the dental hygiene research agenda is to provide a framework to guide those members of the profession who desire to add to the body of knowledge that defines the dental hygiene profession. In recognition of the importance of relevancy of the NDHRA to the dental hygiene profession, ADHA is committed to the ongoing updating of the NDHRA as the dental hygiene body of knowledge expands

ADHA defines the discipline of dental hygiene as the art and science of preventive oral health care including the management of behaviors to prevent oral disease and promote health. 2 The ADHA research agenda proposes to continue to develop and add to the body of knowledge that defines the profession. As research builds the discipline of dental hygiene, the profession demonstrates its value to society through the provision of service and care, and ultimately, improved oral health.

Historically, dental hygiene has drawn in part on other disciplines, such as the disciplines of periodontics and public health, for the evidence used to support its own practice and education. The generation of scientific knowledge and utilization of an interdisciplinary approach to knowledge benefits the profession through shared initiatives and perspectives. The goal of increasing dental hygienists' participation in research is to grow beyond reliance on research originating from other disciplines and, instead, build upon existing research so the knowledge base can emerge from within dental hygiene itself. 3 To this end, the framework of the dental hygiene research agenda directs dental hygiene researchers to contribute knowledge that is unique to dental hygiene. The 5 primary objectives that were the basis for the creation of the National Dental Hygiene Research Agenda still remain applicable today: 4

To give visibility to research activities that enhance the profession's ability to promote the health and well-being of the public;

To enhance research collaboration among members of the dental hygiene community and other professional communities;

To communicate research priorities to legislative and policy-making bodies;

To stimulate progress toward meeting national health objectives; and

To translate the outcomes of basic science and applied research into theoretical frameworks to form the basis for dental hygiene education and practice.

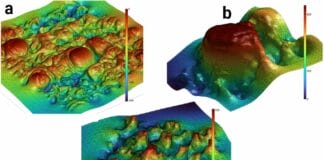

The updated research agenda visually illustrates how the areas of dental hygiene research move through discovery, testing and translation into education and practice. Discovery is the phase of research where ideas are generated, testing is where concepts and interventions are implemented and outcomes are generated and evaluated, and translation disseminates findings to the profession and to the scientific community at large.

Translational research aims to “translate” findings from basic science research into interprofessional medical, nursing and dental practice for improving health outcomes. Decisions for practice or subsequent research are based on all phases: discovery, testing and translation. For example, the discovery phase of research might document barriers, while the testing phase considers assessing interventions and improving application of science to practice. Within the translation level of research, the process of translating or moving findings from research into practice is examined. It verifies that the application of these findings results in improved health for clients and populations. Research hypothesis need to be tested and then applied (translated) in real life settings with outcomes measured and assessed.

Using the three phases of research changes the way we conceptualize the dental hygiene research agenda from a linear design with a list of objectives to a visual display showing the inter-relationship existing between the phases of research and themes or areas of research. The new visual display was designed recognizing that all research is interconnected and multifactorial, while also recognizing that results can influence future need for additional research.

- Perspectives on the ADHA Research Agenda

Dental hygiene and research have been linked since the early 1900s. In 1914, Dr. Fones' 5-year study in public schools demonstrated that dental hygienists can positively impact oral disease using education and preventive methods. 5 Dental hygienists today are increasingly becoming involved in research at all levels and are helping to provide data that will impact the profession for years to come.

The first ADHA National Dental Hygiene Research Agenda (NDHRA) was developed in 1993 by the ADHA Council on Research and adopted by the ADHA House of Delegates in 1994. 4 A Delphi study was used to establish consensus and focus the research topics for the agenda. 6 This was the first step to guide research efforts that support the ADHA strategic plan and goals. A research agenda provides direction for the development of a unique body of knowledge that is the foundation of any health care discipline and, as such, should be used to drive the activities of the profession.

In 2001, the Council on Research revised the agenda to reflect a changing environment based on two national reports: The Surgeon General's Report on Oral Health and Healthy People 2010. Input from the 2000 National Dental Hygiene Research Conference sponsored by ADHA was considered in the revision. The revised document was released in October 2001 and prioritized the key areas of research. 7

In 2007, the agenda was revised to reflect current research priorities aimed at meeting national health objectives and to systematically advance dental hygiene's unique body of knowledge. These revisions were based on a Delphi study that was conducted to gain consensus on research priorities. 8

A goal of the present (2016) revision is to allow greater usability of the agenda across the profession and interprofessionally. The cohesive, coherent visual illustration that constitutes this revision might assist educators in disseminating research concepts to students. By showing the relationships among the priorities, the themes and the research process, the Council on Research hopes to improve understanding of how dental hygienists can use the research agenda. Research is an ongoing process. Contributions can be made to it, and priorities can be revised, at any phase in the model, from discovery through testing, evaluation, dissemination and translation.

In this revision, the Council on Research has integrated feedback on the revised presentation of the agenda received from research meetings with representatives of the International Federation of Dental Hygiene, the Canadian Dental Hygienists Association and The National Center for Dental Hygiene Research and Practice. Feedback from graduate dental hygiene program directors and dental hygiene researchers was included. The revised research agenda allows for ongoing study of specific questions to support the growth of the profession. It also allows for investigation and testing of ideas that will further the transformation of dental hygiene as a profession and facilitates interprofessional collaborations.

- Research as a Foundation for Dental Hygiene Education and Practice

Research provides a foundation for continued development of dental hygiene practice guidelines and, ultimately, optimizes care for individuals, groups, communities and global populations through the use of evidence-based practices. Such a foundation supports the development of position papers that inform practice parameters and standards. Clinicians, researchers and educators can thus use the revised research agenda to generate and publish data to support the ongoing transformation of the profession in the various areas proposed, and to drive activities to build upon other areas not yet defined that might emerge as a result of transformation. Educators can use the agenda to support the ongoing growth and development of both clinicians and junior researchers to guide efforts to advance the profession while identifying new research directions that emerge. 9

Research supports ongoing investigation into fundamental topics of concern to clinicians such as oral and craniofacial diseases and their mechanisms and causation, including inflammation, infection, genetics, neoplasm and the microbiome. Findings might be used to identify strategies to manage or eliminate localized or systemic disease through clinical care; improve delivery of preventive and oral health care services; and identify ways to improve access to care for individuals, groups and populations.

In the same way, research supports transformation of the process of dental hygiene education. It seeks new methods for basic and advanced education of dental hygiene professionals and investigates the outcomes of different programs. For example, research might assess differences between baccalaureate and associate level education with respect to outcomes in the areas of patient care, dental hygiene scope of practice, access to vulnerable populations and career satisfaction.

- Download figure

- Open in new tab

- Download powerpoint

Phases of Research

- Framework for Dental Hygiene Practice and the Discipline

As dental hygiene research advances, it is important to formulate research questions within the conceptual framework of dental hygiene theory. Some theoretical models have been developed, but many have yet to be tested. Rogers' theory of diffusion of innovations is an example of a model that might benefit dental hygienists wishing to study the translation or possibly the implementation of research into practice. 10 Models or theoretical frameworks of care delivery allow the profession to develop from the discipline. Before posing a research question, it is important to consider from a conceptual level the approach to be used for any given area or phase of research. Using dental hygiene theory to frame individual research questions will assist in building a strong, scientifically sound foundation.

- ADHA Dental Hygiene Conceptual Research Model

The ADHA Dental Hygiene Conceptual Research Model illustrates the interrelationship of the areas of dental hygiene research as they progress through the phases of research and move from the level of professional development to influence client-level care and ultimately population health. As Figure 1 illustrates, the phases of research are not linear; each phase asks and answers questions that are intended to allow progression to the next phase, with the study of dissemination and translation effectiveness ultimately circling back to questions of discovery in the search for better answers and methods. It is important to note that in any of these phases of investigation, there may be a need to go back to an earlier level to re-frame or reconsider moving forward. In other words, this model is dynamic, not static.

Conceptual Research Model

Areas of research are equally dynamic. Professional development begins with education, which influences how the profession of dental hygiene is regulated and vice versa. Both influence client-level care and ultimately population-level health. As new methods for health services and access to care are realized, the profession must circle back to evaluate the education and regulation of dental hygiene. As illustrated in Figure 2 , at the intersection of Areas of Research and each Phase of Research, topics of emphasis are illustrated.

As early as 1994, ADHA selected five paradigm concepts to study and has used these concepts to organize previous agendas. The five major concepts are: Health Promotion / Disease Prevention, Health Services Research, Professional Education and Development, Clinical Dental Hygiene Care and Occupational Health and Safety. The dental hygiene conceptual research model captures these five paradigm concepts and illustrates how they might be approached at different phases in the research process.

Researchers can enter into the process at the intersection of any area of research and any phase to ask and answer questions of importance to the discipline of dental hygiene. The model is intended to help researchers frame how their research has been influenced by a preceding phase of research and how it will lead to the next phase. Additionally, it aims to illustrate how their area of research relates to other areas where research might be conducted. The following descriptions of the topics of emphasis from the conceptual research model ( Figure 2 ) are organized by area of research and include an explanation of how the topic fits into the phase of research where it appears.

- Professional Development

Education 11 - 19

Dental hygiene is based on a specific body of knowledge transferred to new professionals through educational processes. Areas of research associated with education include evaluation of current educational processes during the discovery phase, implementing new educational models during the testing and evaluation phase, and exploration of how interprofessional education as part of the ongoing evolution of dental hygiene as a profession is associated with the translation phase of research. 9

Evaluation within the discovery phase of research for education includes ongoing as-sessment of curricular content, delivery and adaptation of educational programming for addressing evolving models of health care and practice; assessing educational institutional investment in alternative delivery models; alternative educational programming; community return on investment; articulation; transferability and academic educational laddering for ongoing growth of the profession.

Educational models during the testing phase of research for education requires implementation and evaluation of new or redesigned educational delivery models based on evolving global public health needs, direct and indirect assessment of both learners' and educators' performance, examining research associated with the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning (SoTL) and alternative career pathways.

Interprofessional education considers more broadly the translation of dental hygiene education as a component of allied health education, the ability of educators to work collaboratively with other health care disciplines, recognizing diversity of faculty backgrounds for creating synergy, promoting lifelong learning and expanding access to care through all means of delivery of health care for global populations.

Regulation research occurs at the dental hygiene profession level. It encompasses the body of knowledge related to the practice of the profession of dental hygiene.

Emerging workforce models involve discovery. Each state in the nation is a potential source of new models for dental hygiene care delivery. The discovery and development of regulations and rules affect the profession of dental hygiene. Regulation discovery includes new workforce models such as, but not limited to, mid-level providers, advanced dental hygiene practitioners and advanced dental hygiene therapists, as well as their effects on public health and well-being.

Scope of practice involves testing and evaluation of potential changes to professional regulations, often through pilot programs. These regulations may have significant impact on the health of the public and ability of dental hygienists to provide the care they are educated and trained to deliver.

Interprofessional collaborations involve professional regulations that translate knowledge into practice through collaborations with other care providers. Collaborations are an endpoint of regulation at the professional level. Areas of interprofessional collaborations include delivery of care in all practice settings, including pediatrician offices, schools and other health care settings that may include hospitals, medical offices, federally qualified health centers and holistic Complementary and Alternative Medicine settings.

Occupational Health

Research in this area focuses predominately on practitioners and their exposure to risks in the oral health care environment. It includes prevention and behavioral issues, as well as compliance with safety measures and workforce recruitment and retention.

Determination and assessment of risks for occupational injury is the discovery phase of research. Uncovering potential hazards to occupational health in the workplace may involve investigating ergonomic impacts, as well as those of aerosols, chemicals, latex, nitrous oxide, noise and infectious diseases.

Methods to reduce occupational stressors involve testing and evaluation of techniques to reduce or eliminate hazards to occupational health. This includes assessing prevention methods, behaviors, compliance with safety measures and error reduction.

Career satisfaction and longevity research assesses the dissemination and translation into practice of methods that reduce the harmful effects of occupational stressors on practitioners. Additionally, it seeks to determine if the successful translation of these methods into practice and the reduction of occupational stressors results in improved careers for dental hygienists.

- Client Level

Basic Science

Basic science research is important at the client level for understanding the mechanisms of health and disease, and investigating the links between oral and systemic health. Areas of research range from caries and periodontal disease to immunology, genetics, cancer, nutrition, pharmacology and exposure to environmental stressors.

Diagnostic testing and assessments in basic science research is discovery of new tools for diagnosis of conditions and diseases and new methods of risk assessment prior to development of disease.

Dental hygiene diagnosis is the testing phase where research is used to evaluate the use of knowledge of emerging science to determine client conditions or needs as related to dental hygiene care.

Clinical decision support tools are the outcome of research validating dental hygiene diagnosis and the translation of those outcomes into tools that can be used broadly in clinical practice. Research in this area confirms the usefulness of the tools developed for this purpose.

Oral Health Care

Research regarding the dental hygienist's role in oral health care encompasses all aspects of the process of care at the client level, including assessment, diagnosis, treatment planning, implementation, evaluation and documentation.

New therapies and prevention modalities for oral health care are developed or improved in the discovery phase of research. This may include new procedures, treatments, behavioral interventions, and instruments/tools/products for delivering client care, new oral self-care products or improved ergonomics.

Health promotion: treatments, behaviors, products in the testing phase means evaluating clinical care products, services, behavioral interventions, and new and alternative treatments developed for these purposes at the client level, often through clinical trials, for safety and effectiveness.

Clinical guidelines are developed as a result of successful treatment and prevention methods and are derived from a strong body of evidence that reflects improved client outcomes. These in turn need translation into routine clinical practice and need to be evaluated through research to assess both their adoption and effectiveness.

- Population Level

Health Services

Health services research is included as part of the population-level area of research. Past agendas identified many objectives in this area. The revised agenda reorganizes health services and access to care to better show the relationship among the phases of research.

Epidemiology in health services research involves discovery. Epidemiological research includes surveys of oral health status and related needs of specific populations and other important health services data related to oral health and dental hygiene.

Community interventions are critical to understanding the testing and impact of oral care interventions on population health. Community interventions have the potential to improve oral health by treating groups rather than individuals. Such programs include school-based oral care programs and public health nutritional campaigns to eliminate or reduce caries, periodontal disease and other preventable oral health problems.

Assurances and evaluation combine as an ongoing strategy to improve translation of population health and community interventions. All programs benefit from the knowledge derived from evaluation of program effectiveness and quality and from assuring that best practices represent outcomes data.

Access to Care

Access to care research involves identifying populations that are challenged to achieve positive health outcomes including good oral health due to recognized and unrecognized barriers to care. Systems of health delivery can be developed, adapted, improved and evaluated for effectiveness in improving access to care and health outcomes in identified populations.

Vulnerable populations are identified in the discovery phase of research through population-level data that link poor health outcomes to various group characteristics. This phase of research also seeks to discover possible barriers to care.

Interventions are developed and implemented in the testing phase of research on access to care. Supporting research might evaluate methods designed to overcome barriers to access or use of risk-reduction strategies in special at-risk populations such as people with diabetes, tobacco users, pregnant women or those identified as genetically susceptible to disease.

Outcomes assessment is a critical aspect of translation of research into population-level health. This phase of research involves verification of improved population health outcomes when presumed barriers or risk-reduction strategies have been addressed across a broad group or identified population.

- ADHA's Strategic Plan Drives Research Priorities

Based on the ADHA's Conceptual Research Model and Strategic Plan, priority areas that researchers are encouraged to investigate include:

Differences between baccalaureate- and associate-level educated dental hygienists.

The impact of dental hygiene mid-level practitioners on oral health outcomes.

Development and testing of conceptual models distinct to dental hygiene that will guide education, practice and research.

Efficacy of preventive interventions across the lifespan including oral health behaviors.

Patient outcomes in varying delivery systems (this can include cost effectiveness, workforce models, telehealth, access to care, direct access etc.).

Focus on these priorities has the potential to accelerate the pace of transformation of the profession to improve the public's oral and overall health. Within these priority areas are research questions to be asked and answered that will impact the future of the profession and the direction of ADHA. Investigators are strongly encouraged to consider how their research might contribute to these priority areas.

- Additional Resources

ADHA's Research Center http://www.adha.org/research-center

Institute for Oral Health, Research Grants http://www.adha.org/ioh-research-grants-main

National Center for Dental Hygiene Research & Practice https://dent-web10.usc.edu/dhnet/

National Center for Dental Hygiene Research & Practice, Dental Hygiene Research Toolkit https://dent-web10.usc.edu/dhnet/research_kit.pdf

The National Dental Practice-Based Research Network http://www.nationaldentalpbrn.org/

American Association for Dental Research (AADR), Student Research Fellowships http://www.aadronline.org/i4a/pages/index.cfm?pageid=3569#.VT_Er7l0xtQ

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Division of Oral Health http://www.cdc.gov/oralhealth/

Centre for Evidence Based Dentistry http://www.cebd.org/

The goal of the revised National Dental Hygiene Research Agenda is to lead the transformation of the dental hygiene profession to improve the public's oral and overall health. The revised research agenda is intended to guide researchers, educators, clinicians and students who seek to support ADHA priorities for advancing the profession through research and the generation of new knowledge within the discipline of dental hygiene. The model provides novice investigators, especially students, as well as junior and experienced researchers, with a visual framework for conceptualizing how their research topic addresses identified priorities. Additionally, this revision prepares the profession to evolve by acknowledging that dental hygiene research is necessary for advancing the profession and improving the health of the public.

The revised research agenda was led by the ADHA 2014-2016 Council on Research, in collaboration with ADHA staff. The members of the Council on Research are:

Deborah M. Lyle, RDH, BS, MS, New Jersey, Chair; Ashley Grill, RDH, BSDH, MPH, New York; Jodi Olmsted, RDH, PhD, Wisconsin; Marilynn Rothen, RDH, MS, Washington.

- Copyright © 2016 The American Dental Hygienists’ Association

- Rizzo Parse R

- ↵ Policy Manual . ADHA Framework for Theory Development . American Dental Hygienists' Association [Internet] . [cited 2016 May 18]. Available from : https://www.adha.org/resources-docs/7614_Policy_Manual.pdf

- Cobban SL ,

- Edgington EM ,

- Spolarich AE ,

- Peterson-Mansfield S ,

- McCarthy MC

- Forrest JL ,

- Gitlin LN ,

- Gadbury-Amyot CC ,

- Doherty F ,

- Connolly I ,

- Spolarich AE

- van Manen M

- Cobban SJ ,

- Zarkowski P

- Overman P ,

- Gurenlian J ,

- Shepard K ,

- Steinbach P ,

- Eshenaur Spolarich A

- Idaho State University. Division of Health Sciences. Department of Dental Hygiene

- Englander R ,

- Cameron T ,

- Ballard AJ ,

- Aschenbrener CA

- ↵ Dental Hygiene Education: Transforming a Profession for the 21st Century . American Dental Hygienists' Association [Internet] . 2015 September [cited 2015 October 12]. Available from : http://www.adha.org/adha-transformational-whitepaper

In this issue

- Table of Contents

- Index by author

- Complete Issue (PDF)

Thank you for your interest in spreading the word on Journal of Dental Hygiene.

NOTE: We only request your email address so that the person you are recommending the page to knows that you wanted them to see it, and that it is not junk mail. We do not capture any email address.

Citation Manager Formats

- EndNote (tagged)

- EndNote 8 (xml)

- RefWorks Tagged

- Ref Manager

- Tweet Widget

- Facebook Like

Jump to section

Similar articles, related articles.

- No related articles found.

- Google Scholar

Articles on Dental hygiene

Displaying all articles.

Caring for older Americans’ teeth and gums is essential, but Medicare generally doesn’t cover that cost

Frank Scannapieco , University at Buffalo and Ira Lamster , Stony Brook University (The State University of New York)

No, it’s not just sugary food that’s responsible for poor oral health in America’s children, especially in Appalachia

Daniel W. McNeil , West Virginia University and Mary L. Marazita , University of Pittsburgh

How did people clean their teeth in the olden days?

Jane Cotter , Texas A&M University

Related Topics

- Curious Kids US

- Dental care

- Dental insurance

- Health inequity

- Older people

- Oral health

- Periodontitis

- US Medicare

Top contributors

Professor and Chair of Oral Biology, University at Buffalo

Clinical Professor of Periodontics and Endodontics, Stony Brook University (The State University of New York)

Assistant Professor of Dental Hygiene, Texas A&M University

Director, Center for Craniofacial and Dental Genetics; Professor of Oral Biology and of Human Genetics, University of Pittsburgh

Eberly Distiniguished Professor Emeritus, Clinical Professor Emeritus of Dental Public Health & Professional Practice, West Virginia University

- X (Twitter)

- Unfollow topic Follow topic

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 01 March 2019

Research dental hygienist - whoever knew there was such a role?

- Rachael England 1

BDJ Team volume 6 , pages 21–23 ( 2019 ) Cite this article

1775 Accesses

5 Altmetric

Metrics details

You have full access to this article via your institution.

After spotting a job advertisement for a research dental hygienist, Rachael England soon found herself in the job and out on the road .

After 13 years of working clinically, I was feeling the need for a new role outside the surgery and with a Master's in Public Health under my belt, I was particularly interested in academia. When I saw a role advertised for 'research dental hygienist' at University College London, the timing couldn't have been better.

I was joining the British Regional Heart Study (BRHS) as a member of the field team. This longitudinal study began in 1978 to understand why high numbers of men were dying prematurely. Around 7,500 men aged 40-60 were recruited via their local GP surgeries. Over the following 40 years the men have undergone several health screenings, activity monitoring, completed annual questionnaires and every two years the office team liaise with their GP surgeries to check for serious health events. At the outset, the team looked at hard water, cardiovascular disease and socioeconomic factors in 24 towns around the UK. The men are now aged 77-97, making it one of the longest running cohort studies in the UK.

In 2012, Dr. Sheena Ramsay joined the research team as Principal Investigator. Her early career as a dentist meant the study developed a more dental theme. As we know, the effects of oral-systemic disease are significant with this age group who may suffer from chronic diseases such as diabetes and cardiovascular disease. Also in this cohort, we could examine the self-reported diet sheets and carry out frailty assessments and dental health checks to see any associations between the remaining dentition and how 'well' the men are now.

The health screenings were to examine the remaining 1,400 men who are well enough to attend the mobile clinic in the town where they were originally recruited (see figure 1 ). The field team comprised a nurse, a phlebotomist and a dental hygienist (me). In addition to a dental examination, the men would have the following recorded:

blood pressure,

arm, calf and waist circumference

frailty measurements (ie grip strength)

walking speed

time of standing to sitting

lung function.

The participants would also complete a memory test while they waited. The office-based team would find premises suitable for the mobile clinic, contact the participants, send reminders, deal with all administration and book hotels for the field team to stay in.

The first two weeks were spent at University College London training and organising the equipment and, most importantly, developing the study protocol and calibrating the dental measurements. Working with Dr. Ramsay, I developed a coded dental chart that would record:

pocket depth

loss of attachment

number of teeth

functional pairs of dentition,

xerostomia score

any other pathology.

I was also responsible for carrying out the lung function assessment using a Vitalograph machine. This is used to assess how well your lungs work by measuring how much air you inhale and how much and how quickly you exhale. The data it delivers - spirometry - diagnoses asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and other conditions that affect breathing. This is especially appropriate among older people who may have been exposed to damaging substances in their earlier lives. The research manager thought the Vitalograph would fit well with the dental station and I only needed a day of training to get to grips with.

As health professionals we all have heard about the North/South divide and have discussed determinants of health during our training. Yet to see it so starkly, in real life, in front of my eyes was staggering.

Despite it being a relatively simple piece of equipment, the training didn't prepare me for the challenge of instructing patients who have experienced cognitive decline. Thankfully, the patient management skills I had learned through being a dental hygienist helped me through.

We then carried out a pilot study. Our statistician belongs to a church in North London and very kindly recruited members of the congregation. This allowed us to tweak the dental protocol, making it easier to record and ensure the whole set up worked smoothly with the right equipment. After a small electrical fire and an urgently purchased new Vitalograph, we were ready to head to the first town!

©RapidEye/E+/Getty Images Plus

Anxiously heading out of London to Bedford we navigated together. The first venue was a community centre, where we set up the mobile clinic in a conference room. Early the next morning the men started arriving.

Each day we had capacity to see 20 men. However, the number who came in varied greatly. Bedford proved to be quite busy, with fit, well and active men aged 80+, mostly still with the majority of their own dentition - albeit heavily restored. After three days we returned to London for a debrief. These sessions allowed us to deal with any challenges, make some input to the next stage and chat about the results.

Next, we headed off for two weeks in Scotland and the North-West. Dunfermline, Falkirk, Ayr and Carlisle. Far fewer participants attended and they were much frailer and mostly had broken or missing teeth or faded, plastic dentures.

As health professionals we have all heard about the North/South divide and have discussed determinants of health during our training. Yet, to see it so starkly, in real life, in front of my eyes was staggering.

Every town holds its own unique history that has shaped the health of these men and their rate of decline into old age. Taking a walk around in an evening I could observe the ghosts of past industry, Burnley's now converted cotton mills and the traces of a mining history, Scunthorpe's steel mills, Lowestoft's deep-sea fishing and Hartlepool, once a thriving port with ship building and steel making industries. With the decimation of the North-East's industrial age, 10,000 jobs were lost, leaving a town the hallmarks of endemic deprivation - substance abuse, urban decay, crime and twice the national average rate of unemployment.

One participant told me 'you'll never get rich working with your back', a testament to the tough, working lives these men have led. Despite this, I have never spent such precious time with people before, older participants who had served in World War II as well as those slightly younger who regaled us with stories of their National Service. We laughed with them over crazy adventures and cried with them when they described the passing of their beloved wives.

What really struck me was the poor state of dental health in every town - except (perhaps predictably), Guildford, Bedford and Southport. Nothing could prepare me for seeing such terrible neglect in so many men, I kept asking myself - how does this happen? How have we reached a state where our elderly are somehow managing without a functional dentition?

Some of the participants shared their barriers to treatment, such as a lack of:

time - due to being the primary carer for their spouse

availability of NHS access

commitment to caring for themselves.

Many were just happy to maintain the status-quo and have regular check-ups and what we probably consider to be palliative dentistry. Is this acceptable with our current knowledge of the oral-systemic link and frailty in old age related to an ability to eat nutritious food?

Taking a walk around in an evening I could observe the ghosts of past industry, Burnley's now converted cotton mills and the traces of a mining history, Scunthorpe's steel mills, Lowestoft's deep-sea fishing, Hartlepool - once a thriving port with ship building and steel making industries.

We need to improve awareness in this age group that their oral health affects their general health and how important it is to see a dental professional regularly.

The role is intense as you see a participant every 10-15 minutes on a busy day. Ergonomics are pretty much out of the window as you lean over a masseuse bed to complete the examination.

Moving between towns was our greatest challenge, packing the equipment back into the van, driving several hundred miles, finding a new location and setting the clinic back up. The facilities varied from doctors' surgeries and church halls to community centres and conference halls. Being greeted with a friendly smile and a cup of tea was the reassurance we needed the session would run smoothly.

©Mark Waugh / Alamy Stock Photo

After 6 months the data collection was complete. It has been sent for entry and processing which takes up to 12 months before the research teams can begin analysis of the findings.

As a career option this role was a refreshing change from working in a clinic, without being too dissimilar.

Although dental hygienists can get involved with research through epidemiological data collection, I would really encourage dental therapists and dental hygienists to look into the role of Research Dental Hygienist. For me, it is wonderful to be a part of such a historic study that has made an impact on so many lives.

It is both fascinating and disturbing to witness first-hand the inequities in health the population suffer and how the determinants of health shape our lives. Our elderly population have amazing lives to share; we should all take the time to listen.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

FDI, Geneva, Schweiz

Rachael England

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Rachael England .

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Cite this article.

England, R. Research dental hygienist - whoever knew there was such a role?. BDJ Team 6 , 21–23 (2019). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41407-019-0004-y

Download citation

Published : 01 March 2019

Issue Date : March 2019

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1038/s41407-019-0004-y

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

Quick links

- Explore articles by subject

- Guide to authors

- Editorial policies

- Open access

- Published: 10 April 2024

Dental patients as partners in promoting quality and safety: a qualitative exploratory study

- Enihomo Obadan-Udoh 1 ,

- Vyshiali Sundararajan 1 ,

- Gustavo A. Sanchez 1 ,

- Rachel Howard 1 ,

- Siddardha Chandrupatla 2 &

- Donald Worley 3

BMC Oral Health volume 24 , Article number: 438 ( 2024 ) Cite this article

145 Accesses

Metrics details

Active patient involvement in promoting quality and safety is a priority for healthcare. We investigated how dental patients perceive their role as partners in promoting quality and safety across various dental care settings.

Focus group sessions were conducted at three dental practice settings: an academic dental center, a community dental clinic, and a large group private practice, from October 2018-July 2019. Patients were recruited through flyers or word-of-mouth invitations. Each session lasted 2.5 h and patients completed a demographic and informational survey at the beginning. Audio recordings were transcribed, and a hybrid thematic analysis was performed by two independent reviewers using Dedoose.

Forty-seven participants took part in eight focus group sessions; 70.2% were females and 38.3% were aged 45-64 years. Results were organized into three major themes: patients’ overall perception of dental quality and safety; patients’ reaction to an adverse dental event; and patients’ role in promoting quality and safety. Dental patients were willing to participate in promoting quality and safety by careful provider selection, shared decision-making, self-advocacy, and providing post-treatment provider evaluations. Their reactions towards adverse dental events varied based on the type of dental practice setting. Some factors that influenced a patient’s overall perception of dental quality and safety included provider credentials, communication skills, cleanliness, and durability of dental treatment.

The type of dental practice setting affected patients’ desire to work as partners in promoting dental quality and safety. Although patients acknowledged having an important role to play in their care, their willingness to participate depended on their relationship with their provider and their perception of provider receptivity to patient feedback.

Peer Review reports

Introduction

In recent years, there has been a surge in research related to dental quality and safety from various parts of the world [ 1 , 2 , 3 , 4 , 5 , 6 , 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 ]. These studies have investigated how adverse events occur in dentistry, identified methodologies for detecting adverse safety events, and focused on developing strategies to reduce the occurrence of adverse events [ 3 , 5 , 6 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 , 14 ].

Patient involvement in quality and safety-promoting activities is an emerging area of interest. Dentistry findings from several studies suggest that patient reports can provide meaningful insight and breadth regarding the quest to understand such adverse events [ 15 , 16 , 17 , 18 , 19 ]. In dentistry, previous studies have demonstrated that patients are apprehensive about safety at the dental office and are willing to participate in activities that promote quality and safety when properly engaged by providers [ 7 , 8 , 15 , 16 , 17 ]. However, majority of these studies focused solely on patients attending a single academic institution. We proposed a study that recruited patients from three different dental care settings to provide an array of diverse perspectives. Through this study, we assessed how dental patients perceive their role as partners in promoting quality and safety across various dental care settings.

Study sites

The study was conducted at three different dental practice settings: an academic dental center (Site U), a community dental clinic (Site I), and a large group dental private practice (Site H). Site H is in Minnesota, while both Sites U and I are located in Texas. The academic dental center (Site U) consists of a pre-doctoral teaching clinic, a resident/postgraduate clinic, and a faculty group practice. Patients visiting this center are from diverse racial and ethnic backgrounds. The community dental clinic (Site I) is comprised of a network of small to medium-sized dental offices scattered throughout the city. Affiliated with a religious non-profit organization, this site primarily serves low income and indigent families who lack access to health care. The large group dental private practice (Site H) encompasses over 70 dentists working across 21 dental office locations. The group serves a large range of patients from various demographic and socioeconomic backgrounds.

Study participants

Participants were recruited using a purposive sampling approach. Patients from the study sites were invited to participate through flyers and word-of-mouth invitations. Interested participants were screened by a local site coordinator to confirm that they met the following inclusion criteria: English-speaking, over 18 years of age, able to give informed consent, and attended at least one dental visit at a participating site. Enrolled participants selected one of eight focus group sessions: three of which were hosted at the academic dental center, three at the large group dental practice, and two at the community dental clinic. Ethical approval was obtained from the UCSF institutional review board (#18–25467). A unique participant’s ID was created for each participant using their site name and sex. Females were represented by “X” and males by “Y”.

Study procedures

Eight focus group sessions were held from October 2018 through July 2019. Researchers were provided with a quiet conference room within each dental site to host the sessions. Sessions lasted about 2.5 h and were recorded using two voice recorders. Participants completed an anonymous demographic questionnaire, an informational survey, and an evaluation form at the beginning or end of the session. Prior to the start of each session, ground rules were provided to participants about taking turns, refrainment from disclosure of comments to external parties, and the need to tolerate dissenting opinions. Name introductions were also done prior to starting the recording to ensure privacy. Participants provided verbal consent after reading the study information sheet. All audio recordings were stored safely on a password-protected laptop and de-identified for analysis. Participants received a $30 gift card along with food and beverage in appreciation of their time. The first author (EO-U) served as the lead facilitator/moderator for all the sessions. There were no conflicts of interest, given the authors do not provide patient care at any of the participating dental institutions.

Study instrument

A focus group discussion guide and informational survey were developed using questions from our previous qualitative study and publications by Davis et al. [ 8 , 16 , 17 ]. The discussion guide consisted of eight main topics with sub-topics and probing questions (see Additional file 1 ). The topics were:

Patients’ understanding about “patient safety” and “quality”

Current practices to ensure high quality care in dental care settings

Perceptions about dental patients contributing to dental quality and safety

Approaches to improve patient engagement in dental quality and safety activities

Factors affecting patients’ willingness to participate in dental quality and safety activities

Factors affecting the reporting of poor quality or adverse safety incidents

Features of a “safe” incident reporting system or platform

Patient considerations about the quality and safety of dental offices

The 45-item informational survey comprised six sections that assessed interactional and non-interactional behavior between patients and the dental care team including: asking factual or challenging questions, notifying the team, providing information, gaining information, and adverse event reporting.

Data analysis

Frequencies and descriptive statistics for demographic characteristics of the participants and survey responses were calculated, and audio recordings from the focus group discussions were professionally transcribed using Rev.com. The transcripts were verified against the original audio recordings for completeness by one co-author (VS).

Using Dedoose, two co-authors (VS, GS) independently analyzed each transcript using the following steps:

Repeated reading : After verifying the transcripts, data was read multiple times and memo writing was performed in Microsoft® Word. The research question served as a guide during this step.

Data coding : Bucket codes were created, and relevant texts from transcripts were selected for initial codes and coded for as many potential themes as feasible.

Exploring for themes : After completion of the initial coding process, a list of different codes identified across the data was generated. Within a code, common themes based on similarities, differences, topics, demographics, and approaches were extracted from the content of the focus group discussions. Opinions expressed by individuals that diverged from group consensus were also identified.

Discussing themes and sub-themes : Both primary coders discussed their initial codes. Similar or duplicate codes were merged into sub-themes. All codes were organized into three major themes based on the study objectives:

Patients’ overall perception of dental quality and safety (Theme 1)

Patients’ reaction to poor quality dental care and adverse events (Theme 2)

Patients’ perception of their role in promoting quality and safety (Theme 3)

Tie-breaking : Any code names or code applications that were discordant between both reviewers, were discussed with a third researcher (EO-U) who acted as a tiebreaker in finalizing the themes, sub-themes, and codes. This was only needed once in the study.

Demographic characteristics

A total of 47 patients ( n = 20 (Site I), n = 16 (Site H), n = 11 (Site U)) were successfully recruited to participate in eight focus group sessions (Table 1 ). Participants in the focus group sessions were mostly female (70.2%), and Caucasian (40.4%). Asians (23.4%) and Latinos (21.3%) were the second and third largest ethnicities represented, respectively. The educational level varied among participants, with nearly 50% having at least a bachelor’s degree. Most participants were aged between 25 – 64 years (68.1%).

Informational survey

The informational survey results were analyzed using descriptive statistics (Table 2 ). Patients were asked to assess willingness to engage in various activities at the dental office using a Likert scale (1 = “Definitely Will” through 7 = “Definitely Not”). Thus, lower mean scores represent patients’ willingness to play an active role in promoting quality and safety and higher scores represented an unwillingness to engage in that activity. While patients appeared willing and comfortable to ask factual questions from dental assistants/hygienists and dentists, patients were less willing to ask challenging questions of such providers unless the provider encouraged it (Table 2 ; Sections 1a, 1b, 2a, and 2b). Patients also reported feeling relatively willing to notify their providers as concerns arose regarding their care (Table 2 ; Sections 3a, 3b). Furthermore, while patients were willing to provide or gain pertinent information about their care or dental office, they were less willing to participate in reporting an adverse event occurrence unless it was encouraged by the dental care team (Table 2 ; Section 4, 5, and 6). We defined an adverse event as “the occurrence of any event that the patient perceived as negative or harmful while receiving care”. There was no significant difference between patients’ willingness to engage in safety behaviors with different members of the dental care team (i.e. dental assistant/ hygienist versus dentist).

Theme 1: patients’ overall perception of dental quality and safety (Table 3 , Section 1)

Provider training and qualifications.

Patients trusted that providers who possessed the proper dental licenses and credentials had received adequate training and education needed to provide high quality dental care. Patients found reassurance in public displays of the provider certificates and necessary clinic approvals, many of whom also inquired the names of their provider’s dental school and their experience performing certain procedures.

Patients at the private dental practice and community health center placed more value on the providers’ experience, years of practice, and reviews through websites, such as Yelp. These patients preferred providers who were not recent graduates; however, they also wanted providers to be familiar with recent clinical procedures and guidelines. In contrast, patients who received care at the academic center had tempered expectations about quality. These patients were comfortable with students’ performing treatments because supervising faculty oversaw every procedure.

Communication

Patients emphasized the importance of clear communication in promoting trust between patients and their dental providers. Participants also wanted providers to be honest about the necessary procedures, and their comfort level with performing those procedures. They preferred that providers educated them appropriately about their oral health and the necessary dental treatment using various methods (e.g., pictures, pre-visit videos, after-visit summaries) to facilitate informed decision making.

Unsurprisingly, exemplifying polite and courteous behavior (good chairside manners) as well as establishing a good rapport were often associated with high quality dental care. Older patients preferred more direct or in-person communication, while younger patients preferred more on-demand or virtual communication. Although the preferred communication methods varied, the theme of clear communication was unanimously expressed as a marker of quality dental care across all dental practice settings.

Cleanliness and clinic environment

Irrespective of the dental practice setting, most patients believed that cleanliness and sanitation were important indicators of dental quality and safety. Markers of cleanliness included: sterile instruments within sealed pouches, clean restrooms, clean floors and office space, constant use of gloves around patients, and the physical appearance of dental staff. Markers of uncleanliness included: foul smells, blood on syringes or instruments used for previous patients left lying around, opened sterilization pouches, and re-using dropped instruments.

Durability of dental treatment

Given patients expected their procedures to last, there was a perception of poor-quality care if patients needed to return for repeat procedures or treatment within a short time period.

Dental patients based their overall perception of dental quality and safety on the professional credentialing of providers, their individual dental care experience, the quality of provider-patient communication, the cleanliness of the dental office environment, and the durability of their treatments. Although patients from all dental settings emphasized the importance of cleanliness, perception of other sub-themes varied by dental practice setting. Whereas patients attending the academic dental center gave the benefit of doubt to the student providers and assumed a degree of risk with receiving poor quality dental care and experiencing adverse events, patients at the private dental office placed more emphasis on the quality of provider training and qualifications.

Theme 2: patients’ reaction to poor quality dental care and adverse events (Table 3 , Section 2)

Breach of trust.

When a patient visits a healthcare provider, they expect to receive adequate treatment to ensure good health. In the focus group sessions, patients expressed that experiencing an adverse event negatively impacted their ability to trust their providers, leaving them uncertain about how best to proceed. Some patients chose not to return to the culpable provider and looked for service elsewhere. Others decided to stop seeking dental treatment altogether due to the anxiety from the negative experience.

Fear and embarrassment

During the focus group sessions, some patients indicated that they were afraid to speak up after a perceived adverse event (i.e., received poor quality care or were harmed by dental treatment). Patients also reported feeling embarrassed for their lack of dental health literacy regarding the dental procedure when an incident occurred.

Clinic response to adverse events

Good communication and provider attitude influenced how patients reacted to adverse situations. Patients expressed the importance of dental practices providing a patient support advocate with whom patients can voice their concerns and/or opinions. However, some patients were concerned that speaking with a patient advocate could lead to provider backlash.

Patients had varying reactions to adverse events and receiving poor quality dental care. Most patients across all institutions expressed that they received adequate support from the provider/clinic team whereas others (predominantly from the community health center) described a reluctance to report their experience due to fear of retribution.

Theme 3: patients’ perception of their role in promoting quality and safety (Table 3 , Section 3)

Rationale for participation.

Dental patients had mixed reactions about their role in promoting dental quality and safety. Those who were positively disposed towards engagement activities believed that participation made them feel empowered about their care, stay informed about their choices, and play an active role in improving their oral health. Some believed reporting safety incidents helped make dental care safer for everyone. Patients who were hesitant about their role in promoting dental safety indicated they felt active participation was unnecessary unless they had received poor quality or unsafe dental care.

Timing of participation

Patient willingness to participate in different types of engagement activities depended on the dental care setting. For example, patients at the academic dental center preferred to deliver feedback immediately or shortly after receiving dental treatment, whereas patients at the private dental practice and community-based dental clinic preferred to wait until after they left the clinic or completed their procedure.

Format of participation

Quality and safety-promoting activities that patients were willing to participate in included: advocating for self when they felt that something was going awry, actively tracking their medical/dental health information, writing reviews, participating in dental research, educating themselves about their oral health conditions and dental procedures, and asking their dental providers questions about their dental procedures or safety practices (e.g., hand washing, sterilized instruments, post-procedural instructions). Patients were more hesitant to ask questions that could potentially appear confrontational. Conversely, patients indicated they were more comfortable speaking when providers invited and encouraged their feedback.

Patients also expressed willingness to participate in focus groups, which provide opportunities to voice opinions without fear of any repercussions from the dentist. Others preferred to have fill out surveys, provide comment cards, or speak directly with a dentist or office staff. Patients from the private practice setting appeared more willing to be involved in promoting the quality and safety of their experiences.

Patients preferred different types of communication based on their demographic information. Older patients with less experience using computers preferred printed materials. No comparable differences were observed between male and female participants in the focus groups; although males participated less often than females in the study.

Most patients, especially those at the academic institution, were willing to participate in activities that promote better dental quality and safety and offered various strategies for increasing patient engagement. However, a few patients from the private group practice expressed concerns about “over-engagement” and suggested that patients should be left alone unless they experienced an adverse event. Reactions varied by dental practice setting, with patients at the private dental office indicating that they received more support when things went wrong than patients at the community dental clinic or academic dental center.

This study investigates factors that influence dental patients’ perceptions of their role in promoting quality and safety across various dental care settings. We used multiple focus group sessions to define patients’ understanding of quality and safety and summarize their past experiences of receiving poor quality or unsafe dental care. Given the scarcity of literature on this topic, this study provides novel insight from three diverse dental care settings to jumpstart the conversation about quality of care from the patient’s perspective.

Although patient safety is a complex, multifactorial matter [ 1 , 18 ], our study and others have found that patients consider cleanliness a key component of patient safety. Congruent with our previous work [ 8 ], patients described the term safety using words associated with cleanliness such as “sterilized or clean instruments.” Wearing clean gloves and sterilizing instruments were perceived as important hygienic practices for practitioners to follow. Additional research has concluded that patients view the cleanliness of their units and sterilization protocols, along with maintaining a “clean clinical environment,” as crucial components of patient safety and quality of care [ 20 , 21 , 22 ]. Other studies have reported that patients deemed the use of state-of-the-art equipment as a necessary requirement for ensuring patient safety [ 20 ].

Patients’ expectations for quality of care from their practitioners varied depending on the dental setting they attended. Our previous work found that patients belonging to academic care settings were concerned about how the inexperience of student providers might impact the quality of dental care they received; however, such apprehensions were eased by faculty member oversight [ 8 ]. This finding aligns with results from our present study where patients expressed comfort in receiving care at the academic dental care setting and were more forgiving of mistakes. Another previous study [ 21 ] revealed that the perceived clinical ability of a dental student and the presence of supervisor oversight and assistance with procedures played a critical role in reducing patient anxiety. However, these opinions were not shared by patients at private practices and the community health center in this study, because they expected higher standards of care from their providers and were less forgiving of mistakes.

Our study revealed that patients from the private dental clinic focused on the credentials and training of their providers and only felt safe if the provider had years of experience and extensive training from top tier institutions. This finding is reinforced by prior research that concludes most patients prefer older practitioners whom they perceive as more experienced with refined communication skills [ 20 ]. On the contrary, a separate study found that some patients preferred younger dentists due to their utilization of technology and innovative methods during treatments [ 22 ]. This study also found that patients preferred female dentists because they believed that they had better interpersonal skills than their male counterparts. Together, these studies highlight how the perceived skills of dentists and their demographic characteristics can impact a patient’s perception of receiving quality dental services [ 23 ].

Dental practitioners have experienced a high volume of complaints over the years. Different studies have found that these complaints originate from various sources. While one study found most complaints were made by parents or relatives of patients [ 24 ], another reported that the majority of complaints received were about personal dental treatment [ 25 ]. Nonetheless, most complaints were made by women [ 25 ]. Reasons for complaints included: post-treatment symptoms like pain and eating issues, emotional trauma, unprofessional conduct, and communication breaches [ 25 ]. In the present study, patients expressed the importance of having a patient advocate who could help them discuss negative experiences with their dentists. Others preferred to seek an alternative dentist rather than return to the same practitioner following an adverse event. Fear played a major role as patients decided whether to report their experiences at the dentist. These findings are in accordance with other studies where patients reported losing trust in their dentist and changing providers due to adverse incidents or perceived risks. However, most patients were able to report incidents through advocate mediums that helped advocate for financial compensations and detect preventable injuries [ 25 ].

Our study also revealed that clear and concise communication was an important strategy for improving the quality of patient care. Participants recommended that practitioners engage in open conversations with patients and give honest opinions on their current oral health status and treatment recommendations. They noted that these strategies could encourage active patient participation in promoting quality and safety by enabling them to make informed decisions. Given the importance of conveying information pre-, during, and post-treatment, study participants viewed failure to properly communicate as a major cause for concern. Similar findings have been reported in other studies, Caltabiano et al [ 21 ].found that 50% of dental patients cited “interpersonal skills” of dental students as a factor that decreased anxiety among their dental patients. Simple descriptions of a patient’s diagnosis and the available treatment options are necessary to attain patient satisfaction and participation [ 26 ]. Research studies have shown that clear explanations during consultations and active listening to patients enable them to grasp the expected outcome of the proposed treatment. Miscommunication, rudeness, and inattentiveness can cause a breach in the relationship between dentists and patients [ 27 ]. Adequate communication is necessary to properly assess a patient’s medical condition or medication use before treatment and to help manage patient behavior during treatments to prevent adverse incidents [ 28 ]. Unclear explanations or indications by professionals can result in poor treatment adherence by patients, thereby compromising effectiveness [ 20 ]. Findings from other studies revealed that patients considered good dental services to include key communication strategies such as empathetic words of encouragement and comfort during the treatment process [ 23 ]. A prior study showed that 40% of patients undergoing dental radiographic treatments never had their dentist explain negative side effects and risk of treatment. More than half of these patients (55%) never or hardly ever made enquiries into the safety measures before undergoing radiography [ 29 ].

Involving patients in the monitoring and reporting process gives them a key role to play in enhancing patient safety, as they can provide provider feedback and report adverse incidents [ 28 ]. Patients in the current study expressed willingness to participate in focus groups that allow them to voice their opinions without fear of repercussions from dentists. Similarly, another study found that patients were willing to actively participate in their care and safety by advocating for themselves and being involved in the decision-making process regarding their conditions. Patients’ participation in care and patient safety measures were used as determinants to assess whether they felt safe or ignored [ 30 ].

Different patients preferred different forms of communication based on certain demographic factors. Older patients preferred to receive printed copies of ‘before’ and ‘after-visit’ summaries and were not comfortable using technological gadgets, while younger patients preferred iPads and other mobile devices, as they considered them to be more effective educational devices for patient engagement during treatment. Though most participants were female, there was no gender-based differences of opinions. A study of internal medicine patients found no difference in participation in patient safety activities based on age, gender, or profession [ 18 ]. However, an alternative study indicated that younger patients with advanced education were more willing to participate in the decision-making process regarding their treatments [ 20 ].

Although our findings have limited generalizability due to the use of convenience sampling, our study provides critical information on the willingness of dental patients across various dental care settings to participate in activities that promote the quality and safety of dental care. This study builds upon the findings from our previous work investigating patient participation at a single academic dental center. The conclusions confirm that dental patients react differently to working as partners depending on the dental care setting in which they receive care. Future studies assessing the patient’s perspective should also assess their oral health literacy, since their knowledge of dentistry may impact their perception. Such studies will help determine accessible and feasible methods for improving patient engagement in quality and safety.

Based on our findings, we offer several recommendations on how to facilitate patient participation in safety and quality care activities. “What to expect” summaries for pre-, during, and post-dental treatment periods need to be developed and customized for each dental procedure. Practices should consider employing patient advocates to handle patient concerns and make the feedback process more approachable. While employing a patient advocate might not be feasible in smaller dental offices, some alternatives could be to designate an administrative staff member to manage patient concerns or partner with other local dental offices to outsource the handling of patient grievances to a third-party patient advocacy or mediation group for resolution. Results from our study emphasize that dental practitioners should be approachable and deliver the necessary information at the right time using various modalities depending on the patient’s needs and preferences. Altogether, implementing these strategies will improve patient participation in quality and safety activities in dental care settings.

Our study revealed that dental patients care about the quality and safety of care that they receive. Their willingness to participate in quality and safety activities depended on their relationship with the provider and their perception regarding the receptiveness of providers to accept feedback. Patients were less willing to participate if an activity if it could potentially be perceived as confrontational. The type of dental care setting slightly impacted how patients perceived their role as partners in improving the quality and safety of dental care.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets during and/or analyzed during the current study available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Bailey E, Tickle M, Campbell S, O’Malley L. Systematic review of patient safety interventions in dentistry. BMC Oral Health. 2015;15(1):152.

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Black I, Bowie P. Patient safety in dentistry: development of a candidate “never event” list for primary care. Br Dent J. 2017;222(10):782–8.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Kalenderian E, Obadan-Udoh E, Maramaldi P, et al. Classifying adverse events in the dental office. 2017.

Google Scholar

Kalenderian E, Obadan-Udoh E, Yansane A, et al. Feasibility of electronic health record–based triggers in detecting dental adverse events. Appl Clin Inform. 2018;9(3):646.

Maramaldi P, Walji MF, White J, et al. How dental team members describe adverse events. J Am Dent Assoc. 2016;147(10):803–11.

Obadan EM, Ramoni RB, Kalenderian E. Lessons learned from dental patient safety case reports. J Am Dent Assoc. 2015;146(5):318-326.e312.

Obadan-Udoh E, Panwar S, Yansane A-I, et al. Are dental patients concerned about safety? An exploratory study. J Evid Based Dent Pract. 2020;20(3):101424.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Obadan-Udoh EM, Gharpure A, Lee JH, Pang J, Nayudu A. Perspectives of dental patients about safety incident reporting: a qualitative pilot study. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(8):e874–82.

Wright S, Ucer C, Speechley S. The perceived frequency and impact of adverse events in dentistry. Fac Dent J. 2017;9(1):14–9.

Article Google Scholar

Walji M, Yansane A, Hebballi N, et al. Finding dental harm to patients through electronic health record-based triggers. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2020;5(3):271–7.

CAS Google Scholar

Kalenderian E, Obadan-Udoh E, Maramaldi P, et al. Classifying adverse events in the dental office. J Patient Saf. 2021;17(6):e540–56.

Franklin A, Kalenderian E, Hebballi N, et al. Building consensus for a shared definition of adverse events: a case study in the profession of dentistry. J Patient Saf. 2022;18(5):470–4.

Kalenderian E, Lee JH, Obadan-Udoh EM, Yansane A, White JM, Walji MF. Development of an inventory of dental harms: methods and rationale. J Patient Saf. 2022;10:1097.

Yansane A, Lee J, Hebballi N, et al. Assessing the patient safety culture in dentistry. JDR Clin Transl Res. 2020;5(4):399–408.

Vincent CA, Coulter A. Patient safety: what about the patient? Qual Saf Health Care. 2002;11(1):76–80.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Davis RE, Sevdalis N, Pinto A, Darzi A, Vincent CA. Patients’ attitudes towards patient involvement in safety interventions: results of two exploratory studies. Health Expect. 2013;16(4):e164–76.

Davis RE, Sevdalis N, Vincent CA. Patient involvement in patient safety: How willing are patients to participate? BMJ Qual Saf. 2011;20(1):108–14.

Sahlström M, Partanen P, Azimirad M, Selander T, Turunen H. Patient participation in patient safety—an exploration of promoting factors. J Nurs Manag. 2019;27(1):84–92.

Weingart SN, Price J, Duncombe D, et al. Patient-reported safety and quality of care in outpatient oncology. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2007;33(2):83–94.

PubMed Google Scholar

Henríquez-Tejo RB, Cartes-Velásquez RA. Patients’ perceptions about dentists: a literature review. Odontoestomatologia. 2016;18(27):15–22.

Caltabiano ML, Croker F, Page L, et al. Dental anxiety in patients attending a student dental clinic. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):1–8.

Furnham A, Swami V. Patient preferences for dentists. Psychol Health Med. 2009;14(2):143–9.

Luo JYN, Liu PP, Wong MCM. Patients’ satisfaction with dental care: a qualitative study to develop a satisfaction instrument. BMC Oral Health. 2018;18(1):1–10.

Thomas L, Tibble H, Too L, Hopcraft M, Bismark M. Complaints about dental practitioners: an analysis of 6 years of complaints about dentists, dental prosthetists, oral health therapists, dental therapists and dental hygienists in Australia. Aust Dent J. 2018;63(3):285–93.

Hiivala N, Mussalo-Rauhamaa H, Murtomaa H. Can patients detect hazardous dental practice? A patient complaint study. Int J Health Care Qual Assur. 2015;28:274.

Iqbal W, Faran F, Yashfika A, Shoro F. Evaluation of dental care through patient satisfaction feedback–a cross sectional study at Dental Institute of OJHA Hospital, Karachi. Pakistan Adv Dent & Oral Health. 2018;8(4):0083–91.

Dental Protection Limited. Handling Compliants-England. https://www.dentalprotection.org/docs/librariesprovider4/dental-advice-booklets/dental-advice-booklet-complaints-handling-england.pdf . Published 2016. Accessed 25 July 2022.

Hiivala N. Patient safety incidents, their contributing and mitigating factors in dentistry. 2016.

Al Faleh W, Mubayrik AB, Al Dosary S, Almthen H, Almatrafi R. Public perception and viewpoints of dental radiograph prescriptions and dentists’ safety protection practice. Clin Cosmet Investig Dent. 2020;12:533.

Ringdal M, Chaboyer W, Ulin K, Bucknall T, Oxelmark L. Patient preferences for participation in patient care and safety activities in hospitals. BMC Nurs. 2017;16(1):1–8.

Download references

This project was funded by the UCSF Hellman Family Fund. The views presented here are strictly those of the authors and do not represent the views of the sponsoring organization.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Preventive and Restorative Dental Sciences, University of California San Francisco, School of Dentistry, 707 Parnassus Avenue, D3214, Box #1361, San Francisco, CA, 94143, USA

Enihomo Obadan-Udoh, Vyshiali Sundararajan, Gustavo A. Sanchez & Rachel Howard

Ibn Sina Community Dental Clinic, Houston, TX, USA

Siddardha Chandrupatla

HealthPartners Institute, Bloomington, MN, USA

Donald Worley

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Contributions

E.O. was responsible for the study design, overall study execution, including obtaining IRB approvals, designing study instruments and recruitment flyers, data interpretation and manuscript, designing study instruments, recruitment flyers, data interpretation and man writing. V.S. assisted with data collection and analysis. G.S. performed data analysis and helped write the results section. RH revised the manuscript and prepared the tables. SC participated in patient recruitment. D.W. participated in study conceptualization, patient recruitment, and data collection. All authors reviewed and approved the final version of manuscript.

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Enihomo Obadan-Udoh .

Ethics declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate.