Currently Trending:

Find your space in nature with our April issue

Book review: the hidden fires – a cairngorms journey with nan shepherd by merryn glover, give me shelter: 8 of the best bothy walks in britain, creator of the month: appreciating the outdoors with city girl in nature, can campwild’s paid ‘wild camping’ help deliver the land justice revolution, how to stay dry when hiking, the great outdoors reader awards 2024, foot care for hikers: how to protect your feet on hillwalks, mountain weather phenomena: fogbows, inversions, aurora, brocken spectres and more, hike further: long-distance trails in the uk and ireland, 7 quiet hikes in snowdonia/eryri, access to nature is not a luxury – history proves it’s a necessity for a world-weary population, book review – in her nature: how women break boundaries in the great outdoors by rachel hewitt.

Advertisement

PHD M.Degree 400 K custom-made review

Overall Rating

: 4 out of 5

Pros: warmth, custom-fit and custom-made, weight

Cons: Price

Manufacturer:

The phd m.degree 400 k custom-made bags are for those who demand the best warmth-to-weight ratio, and who are prepared to pay for it, says fiona russell..

The PHD M.Degree 400k sleeping bag appeared on our guide to the Best sleeping bag for hiking . PHD makes all of its sleeping bags from start to finish in a UK factory. The company sources more than 95% of materials and components within Europe and minimises global transportation. The down is ethically sourced by PHD itself. This goes some way to explain the fairly eye-watering price of the PHD M.Degree 400 K custom-made, but it’s also a fully custom-made bag. As such, it fits me like a glove in width, length and at my feet.

Price: £882 | Weight: 560g (Standard Custom Made) Materials: 1000 fill power European goose down; shell and liner: 7X ripstop nylon with DWR | Temperature: comfort -9C | Features: Customised to suit customer size and needs; choice of four lengths and four widths; half and full-length zip, right or left, dual-construction design, oval-shaped footbox, various add-on options at extra cost including waterproof footbox/outer shell, stuff bag, mesh storage bag | Sizes: 16 sizes, depending on requests | Men’s version: Unisex

Slipping inside the bag is immediately cosy, and it’s easily the warmest bag I’ve tested. It’s also the lightest, and to achieve this PHD uses a different construction on the top compared to the underside to “optimise down lofting and shed excess bulk”. Weight is further reduced by the lightweight and wind-resistant nylon lining and shell fabric. I also chose a short zip.

The hood is smaller and more basic than other bags, and whilst it can be cinched around the neck it doesn’t have baffles. A couple of niggles include a sticky zip, and a drawcord for the hood adjuster that sits annoyingly in front of the face. Additionally, the narrow fit means stretching my legs whilst sleeping is not possible. PHD custom-made bags are for those who demand the best warmth-to-weight ratio, and who are prepared to pay for it.

You may also like...

25th April 2024

Smartwool Women’s Intraknit Active Full Zip Jacket Review

by laradunn

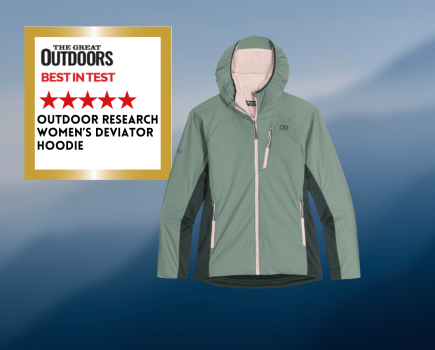

Outdoor Research Women’s Deviator Hoodie Review

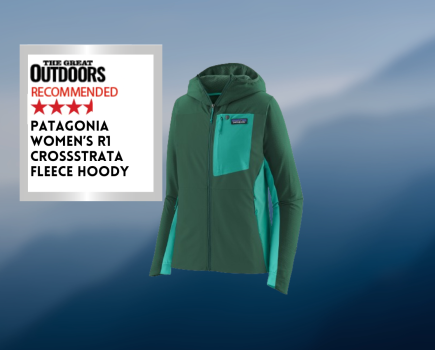

Patagonia Women’s R1 CrossStrata Fleece Hoody Review

Subscribe and save today! Enjoy every issue delivered directly to your door!

No thanks, I’m not interested!

How Long Does It Take to Get a Ph.D. Degree?

Earning a Ph.D. from a U.S. grad school typically requires nearly six years, federal statistics show.

How Long It Takes to Get a Ph.D. Degree

Caiaimage | Tom Merton | Getty Images

A Ph.D. is most appropriate for someone who is a "lifelong learner."

Students who have excelled within a specific academic discipline and who have a strong interest in that field may choose to pursue a Ph.D. degree. However, Ph.D. degree-holders urge prospective students to think carefully about whether they truly want or need a doctoral degree, since Ph.D. programs last for multiple years.

According to the Survey of Earned Doctorates, a census of recent research doctorate recipients who earned their degree from U.S. institutions, the median amount of time it took individuals who received their doctorates in 2017 to complete their program was 5.8 years. However, there are many types of programs that typically take longer than six years to complete, such as humanities and arts doctorates, where the median time for individuals to earn their degree was 7.1 years, according to the survey.

Some Ph.D. candidates begin doctoral programs after they have already obtained master's degrees, which means the time spent in grad school is a combination of the time spent pursuing a master's and the years invested in a doctorate. In order to receive a Ph.D. degree, a student must produce and successfully defend an original academic dissertation, which must be approved by a dissertation committtee. Writing and defending a dissertation is so difficult that many Ph.D. students drop out of their Ph.D. programs having done most of the work necessary for degree without completing the dissertation component. These Ph.D. program dropouts often use the phrase " all but dissertation " or the abbreviation "ABD" on their resumes.

According to a comprehensive study of Ph.D. completion rates published by The Council of Graduate Schools in 2008, only 56.6% of people who begin Ph.D. programs earn Ph.D. degrees.

Ian Curtis, a founding partner with H&C Education, an educational and admissions consulting firm, who is pursuing a Ph.D. degree in French at Yale University , says there are several steps involved in the process of obtaining a Ph.D. Students typically need to fulfill course requirements and pass comprehensive exams, Curtis warns. "Once these obligations have been completed, how long it takes you to write your dissertation depends on who you are, how you work, what field you're in and what other responsibilities you have in life," he wrote in an email. Though some Ph.D. students can write a dissertation in a single year, that is rare, and the dissertation writing process may last for several years, Curtis says.

Curtis adds that the level of support a Ph.D. student receives from an academic advisor or faculty mentor can be a key factor in determining the length of time it takes to complete a Ph.D. program. "Before you decide to enroll at a specific program, you’ll want to meet your future advisor," Curtis advises. "Also, reach out to his or her current and former students to get a sense of what he or she is like to work with."

Curtis also notes that if there is a gap between the amount of time it takes to complete a Ph.D. and the amount of time a student's funding lasts, this can slow down the Ph.D. completion process. "Keep in mind that if you run out of funding at some point during your doctorate, you will need to find paid work, and this will leave you even less time to focus on writing your dissertation," he says. "If one of the programs you’re looking at has a record of significantly longer – or shorter – times to competition, this is good information to take into consideration."

He adds that prospective Ph.D. students who already have master's degrees in the field they intend to focus their Ph.D. on should investigate whether the courses they took in their master's program would count toward the requirements of a Ph.D. program. "You’ll want to discuss your particular situation with your program to see whether this will be possible, and how many credits you are likely to receive as the result of your master’s work," he says.

How to Write M.D.-Ph.D. Application Essays

Ilana Kowarski May 15, 2018

Emmanuel C. Nwaodua, who has a Ph.D. degree in geology, says some Ph.D. programs require candidates to publish a paper in a first-rate, peer-reviewed academic journal. "This could extend your stay by a couple of years," he warns.

Pierre Huguet, the CEO and co-founder of H&C Education, says prospective Ph.D. students should be aware that a Ph.D. is designed to prepare a person for a career as a scholar. "Most of the jobs available to Ph.D. students upon graduation are academic in nature and directly related to their fields of study: professor, researcher, etc.," Huguet wrote in an email. "The truth is that more specialization can mean fewer job opportunities. Before starting a Ph.D., students should be sure that they want to pursue a career in academia, or in research. If not, they should make time during the Ph.D. to show recruiters that they’ve traveled beyond their labs and libraries to gain some professional hands-on experience."

Jack Appleman, a business writing instructor, published author and Ph.D. candidate focusing on organizational communication with the University at Albany—SUNY , says Ph.D. programs require a level of commitment and focus that goes beyond what is necessary for a typical corporate job. A program with flexible course requirements that allow a student to customize his or her curriculum based on academic interests and personal obligations is ideal, he says.

Joan Kee, a professor at the University of Michigan with the university's history of art department, says that the length of time required for a Ph.D. varies widely depending on what subject the Ph.D. focuses on. "Ph.D. program length is very discipline and even field-specific; for example, you can and are expected to finish a Ph.D, in economics in under five years, but that would be impossible in art history (or most of the humanities)," she wrote in an email.

Kee adds that humanities Ph.D. programs often require someone to learn a foreign language, and "fields like anthropology and art history require extensive field research." Kee says funding for a humanities Ph.D. program typically only lasts five years, even though it is uncommon for someone to obtain a Ph.D. degree in a humanities field within that time frame. "Because of this, many if not most Ph.D. students must work to make ends meet, thus further prolonging the time of completion," she says.

Jean Marie Carey, who earned her Ph.D. degree in art history and German from the University of Otago in New Zealand, encourages prospective Ph.D. students to check whether their potential Ph.D. program has published a timeline of how long it takes a Ph.D. student to complete their program. She says it is also prudent to speak with Ph.D. graduates of the school and ask about their experience.

Online Doctoral Programs: What to Expect

Ronald Wellman March 23, 2018

Kristin Redington Bennett, the founder of the Illumii educational consulting firm in North Carolina, encourages Ph.D. hopefuls to think carefully about whether they want to become a scholar. Bennett, who has a Ph.D. in curriculum and assessment and who previously worked as an assistant professor at Wake Forest University , says a Ph.D. is most appropriate for someone who is a "lifelong learner." She says someone contemplating a Ph.D. should ask themselves the following questions "Are you a very curious person... and are you persistent?"

Bennett urges prospective Ph.D. students to visit the campuses of their target graduate programs since a Ph.D. program takes so much time that it is important to find a school that feels comfortable. She adds that aspiring Ph.D. students who prefer a collaborative learning environment should be wary of graduate programs that have a cut-throat and competitive atmosphere, since such students may not thrive in that type of setting.

Alumni of Ph.D. programs note that the process of obtaining a Ph.D. is arduous, regardless of the type of Ph.D. program. "A Ph.D. is a long commitment of your time, energy and financial resources, so it'll be easier on you if you are passionate about research," says Grace Lee, who has a Ph.D. in neuroscience and is the founder and CEO of Mastery Insights, an education and career coaching company, and the host of the Career Revisionist podcast.

"A Ph.D. isn't about rehashing years of knowledge that is already out there, but rather it is about your ability to generate new knowledge. Your intellectual masterpiece (which is your dissertation) takes a lot of time, intellectual creativity and innovation to put together, so you have to be truly passionate about that," Lee says.

Curtis says a prospective Ph.D. student's enthusiasm for academic work, teaching and research are the key criteria they should use to decide whether to obtain a Ph.D. degree. "While the time it takes to complete a doctorate is an understandable concern for many, my personal belief is that time is not the most important factor to consider," he says. "Good Ph.D. programs provide their students with generous stipends, health care and sometimes even subsidized housing."

Erin Skelly, a graduate admissions counselor at the IvyWise admissions consulting firm, says when a Ph.D. students struggles to complete his or her Ph.D. degree, it may have more to do with the student's academic interests or personal circumstances than his or her program.

"The time to complete a Ph.D. can depend on a number of variables, but the specific discipline or school would only account for a year or two's difference," she wrote in an email. "When a student takes significantly longer to complete a Ph.D. (degree), it's usually related to the student's coursework and research – they need to take additional coursework to complete their comprehensive exams; they change the focus of their program or dissertation, requiring extra coursework or research; or their research doesn't yield the results they hoped for, and they need to generate a new theory and conduct more research."

Skelly warns that the average completion time of a Ph.D. program may be misleading in some cases, if the average is skewed based on one or two outliers. She suggests that instead of focusing on the duration of a particular Ph.D. program, prospective students should investigate the program's attritition and graduation rates.

"It is worthwhile to look at the program requirements and the school's proposed timeline for completion, and meet current students to get their input on how realistic these expectations for completion are," Skelly says. "That can give you an honest idea of how long it will really take to complete the program."

Searching for a grad school? Access our complete rankings of Best Graduate Schools.

Tags: graduate schools , education , students

You May Also Like

How to win a fulbright scholarship.

Cole Claybourn and Ilana Kowarski April 26, 2024

What to Ask Law Students and Alumni

Gabriel Kuris April 22, 2024

Find a Strong Human Rights Law Program

Anayat Durrani April 18, 2024

Environmental Health in Medical School

Zach Grimmett April 16, 2024

How to Choose a Law Career Path

Gabriel Kuris April 15, 2024

Questions Women MBA Hopefuls Should Ask

Haley Bartel April 12, 2024

Law Schools With the Highest LSATs

Ilana Kowarski and Cole Claybourn April 11, 2024

MBA Programs That Lead to Good Jobs

Ilana Kowarski and Cole Claybourn April 10, 2024

B-Schools With Racial Diversity

Sarah Wood April 10, 2024

Law Schools That Are Hardest to Get Into

Sarah Wood April 9, 2024

PHD Minim 500 Review

- £272 with M1 Outer (Correct on 01/09/10)

- Sale price £176 (M1 Outer) and £196 (Drishell Outer) (Correct on 01/09/10)

- PHD – 810g (M1 Outer) or 855g (Drishell Outer)

- Weighed – 908g (Drishell Outer)

Minimum Temperature rating:

The Review The PHD Minim 500 is a stripped down lightweight minimalist sleeping bag. PHD Clothing has a reputation for producing uncompromising designs for maximum performance and the Minim 500 is the absolute epitome of this.

It has been stripped of almost all extraneous features such as zips and a neck baffle; but retains high quality down (800 fill power) and lightweight fabrics to create a sub 1kg sleeping bag with a minimum temp rating of -10°C. Its lack of features continues with a simple oval foot piece and standard hood design.

As PHD Clothing say of the lighter minimus it “is a single purpose down sleeping bag, effective warmth at the least possible weight”. This extreme approach to weight saving also results in reduced pack size.

Many people have criticized the PHD Minim 500 sleeping bag for not achieving its -10°C minimum temperate rating. Whilst this is only a guideline figure, it is as a result of the weight/feature saving that the minimum temperature rating is hard to achieve.

For example, the omission of a neck baffle means you have to be extremely fastidious to create an effective heat seal around your head and neck to trap heat in. This can be achieved with careful use of a jacket or tucking the sleeping bag in around your shoulders.

Likewise the hood and foot piece do not fit as snugly as a more complex anatomical mummy hood or trapezoid/ovoid foot piece. Collectively these differences mean you have to work harder to get it to perform to its potential.

One final note on the minimum temperature rating; whilst many factors contribute to this the warmth/insulation of your sleeping mat can be one of the largest differences. To achieve a comfort rating of -10°C you will need a sleeping mat capable of insulating you from the ground at these temperatures (R-value >3.5 as a rough guide).

PHD Clothing offers the choice of outer fabrics across the Minim range; the Minim 500 being reviewed features a Drishell outer, this is a ripstop nylon with a ultra-light coating providing good water resistance.

Whilst keeping a down sleeping bag dry is essential to maintain its performance, having a water resistant outer alleviates some of the anxiety of getting it wet, e.g. drips from a tent or snowhole can be easily brushed off.

It also allows you to turn the sleeping bag inside out if you are damp but your surroundings are not; helping to keep the down dry and preserving its loft.

- Minimal features help to create a lightweight sleeping bag with small pack size.

- Drishell outer fabric helps to keep down dry and lofting.

- Omission of key features and simplicity of others mean you must work harder to get the most from the bag.

- Design and styling is not as cosmetically appealing as many other brands. Whilst only psychological, things which look better often perform better in the eyes of the user.

The verdict The PHD Minim 500 is an excellent lightweight down sleeping bag. Although a small weight penalty, the addition of a Drishell outer is highly recommended. However the user needs to be careful to ensure that they prevent as much heat as possible from escaping due to the lack of neck baffle and simplistic hood design if they are using it in colder conditions.

PHD designs Software M.Degree 300 K Down Sleeping Bag

- Condition: Neu mit Etikett

- Brand: Degree

- Type: Sleeping Bag

- Size: STANDARD

PicClick Insights - PHD designs Software M.Degree 300 K Down Sleeping Bag PicClick Exclusive

- Popularity - 8 watchers, 4.0 new watchers per day , 2 days for sale on eBay. Super high amount watching. 1 sold, 0 available. More

Popularity - PHD designs Software M.Degree 300 K Down Sleeping Bag

8 watchers, 4.0 new watchers per day , 2 days for sale on eBay. Super high amount watching. 1 sold, 0 available.

- Best Price -

Price - PHD designs Software M.Degree 300 K Down Sleeping Bag

- Seller - 737+ items sold. 12.8% negative feedback. OK seller. eBay Money Back Guarantee: Get the item you ordered, or your money back! More

Seller - PHD designs Software M.Degree 300 K Down Sleeping Bag

737+ items sold. 12.8% negative feedback. OK seller. eBay Money Back Guarantee: Get the item you ordered, or your money back!

Recent Feedback

People also loved picclick exclusive.

- SM and ME Course Requirements

[Part of the Policies of the CHD, August 2019]

The following course requirements apply to all SEAS S.M. and M.E. degrees. Note that the term "course" refers to a standard Harvard semester-length "half course", i.e., a 4-unit FAS course or its equivalent. 2-unit courses such as AP 299qr count as "half of a course" in the context of these requirements.

- Eight letter-graded courses are required for the degree (or twelve for the S.M. in Data Science. ). As many of these as possible should be SEAS 200-level courses. M.E. students must take eight additional non-letter-graded research-oriented courses at the 300-level that result in the completion of the required M.E. thesis.

- At least four of the eight courses must be offered through SEAS or taught by a SEAS faculty member in another FAS department.

- At least five of the eight courses must be 200-level SEAS/FAS technical courses, not including reading and research courses (299r), seminar/project courses (298, 297, 294, possibly with letter postfixes), or innovation or communication courses. The remaining three courses should be from SEAS, FAS departments, other Harvard schools, or MIT. (Note: for MIT courses students should attach the course syllabus and the catalog description when submitting their program plan, indicating MIT G-level status).

- Up to three of the eight courses may be 100-level SEAS/FAS courses. As a guideline, having one 100-level course will generally not lead to any concern; having two 100-level courses requires at least some justification (i.e., that the courses are necessary prerequisites for 200-level courses); having three will generally lead to close examination by the CHD. Courses at lower than the 100-level, including all General Education courses, may not be counted towards the degree.

- Only one reading and research (299r), seminar/project (298, 297, 294, possibly with letter postfixes), innovation, or communication course can count among the eight courses. An exception is that two such courses are allowed in a CSE S.M. program plan. S.M. students who are writing a thesis may include up to two 299r courses.

- Harvard Extension School courses may not be included in the program plan.

- Transfer credit is not accepted toward the degree.

- No 300-level courses may be included in the program plan. ES 399-TIME and AC 399-TIME may not be included in an S.M. or M.E. Program Plan.

- Exceptions to these requirements are considered by petition to the CHD.

S.M. and M.E. degree grade and area-specific course requirements

In addition to fulfilling the SEAS-wide course requirements, S.M. and M.E. students are required to satisfy the applicable area-specific requirements described in the drop-down lists that follow, as well as the grade expectations in the final drop-down listing.

Consistent with other SEAS Master of Science programs, in order to count towards the Master of Science degree requirements, elective course plans for MS/MBA: Engineering Sciences students must be approved by the SEAS Committee on Higher Degrees (CHD). 300-level courses and sub-100-level courses may not be included in the Program Plan. No course completed with a grade less than C may be included, and students must achieve a B or better average letter grade in the courses for the degree.

Class of 2023

I. Master of Science Course Requirements - eight letter-graded four-credit courses:

A. ES 280: Designing Technology Ventures

B. ES 234: Technology Venture Immersion

C. ES 285: Design Theory and Practice

D. ES 292a: Launch Lab/Capstone I

E. ES 292b: Launch Lab/Capstone II

F. One 200- or 100-level SEAS or SEAS-equivalent technical elective (see II below)

G-H. Two additional technical electives chosen from SEAS or FAS 200/2000-levels or MIT G-levels (see III below)

- If elective F is not a 100-level, one of the remaining electives could be 100/1000-level or a class from another Harvard school.

II. Technical Courses - By default, the following are considered to be 200-level SEAS or SEAS-equivalent technical electives:

- Exceptions include seminar, project, or reading and research courses (e.g., any 294, 297, 298, or 299 course whether or not the number is followed by letters), courses focusing on innovation, entrepreneurship, or written/verbal communication, and “Great Papers”-type courses (e.g. AC 221, AP 227, ES 236a/b, ES 238, ES 239, ES 256).

- Any FAS 200-level technical course taught by a SEAS ladder faculty member ("SEAS-equivalent"). Most 200-level courses in natural sciences and quantitative fields will be technical, with similar exceptions as for SEAS courses (although FAS departments do not follow the same numbering conventions for seminar and project classes).

- Physics 223 (Electronics for Scientists)

III. MIT Courses

- Two G-level MIT technical courses may be taken as electives, pending review by the Committee on Higher Degrees (CHD) for approval for technical graduate-level rigor and adherence to the applicable section of the CHD Policies: "Courses taken by cross-registration should cover subjects not otherwise available in FAS: that is, they should not be taken in place of or in addition to any comparable FAS course without good and sufficient reasons."

- In order to be equivalent to a 4-credit FAS course, an MIT class must count for 9-21 units.

Ph.D students in Applied Mathematics may receive the S.M. in Applied Mathematics en route to the Ph.D by completing 8 courses from their approved Ph.D. Program Plan that meet the SEAS S.M. requirements described above.

A.B./S.M. students who are candidates for the S.M. in Applied Mathematics, and Ph.D. students in other subjects who wish to receive the S.M. in Applied Mathematics en route to the Ph.D., must fulfill the following minimum area requirements:

- Four 200-level AM courses, including AM 201 and AM 205 (unless one or both are not offered in a timely fashion). Note that AM 104 and AM 105 are prerequisites for AM 201, and are effectively prerequisites for many other 200-level Applied Mathematics classes.

- Two additional SEAS or FAS 200-level technical classes, whether from Applied Mathematics or not.

- Demonstration of breadth across the mathematical sciences. At least one course in Statistics is strongly recommended, at the 100 or 200 level.

- At least two of the non-AM classes must represent a specific application area.

Students seeking an S.M. in Applied Mathematics should construct a coherent Applied Mathematics program plan with their assigned SEAS graduate advisor.

- The AB/SM program is for currently enrolled Harvard College students only. Follow this link for more information.

- PhD students' questions can be directed to the Director of Graduate Education, John Girash .

Harvard Ph.D. and A.B/S.M. students seeking an S.M. in Applied Physics must fulfill the following area requirements:

- Four of the eight required courses must be 200-level Applied Physics courses or 200-level Physics courses taught by SEAS faculty. ES 240, ES 273, ES 274 and ES 277 count as 200-level Applied Physics courses toward this requirement.

- The remaining four courses must be technical/scientific.

Candidates for a terminal S.M. degree in Applied Physics (including the A.B./S.M.) are advised against including a 299r class in their Program Plan. Ph.D. students seeking the S.M. en route may include one 299r as a “technical/scientific” course in #2 above.

Harvard Ph.D. and AB/SM students seeking an S.M. in Computer Science must fulfill the following area requirements:

- Five of the eight required courses must be 200-level courses specifically covering topics in computer science. Generally this means they must be offered as courses in Computer Science. AM 220 is also considered to be a computer science course in this context. In particular, for Computer Science graduate degrees, Applied Computation courses may be counted as 100-level courses, not 200-level courses. The CHD may approve exceptions.

- At least one of these five 200-level courses must be in Theory. There is no specific list of Theory courses; this rule is enforced by the faculty advisors and the CHD. However, in almost all cases, any class with a course number CS 22x or CS 231 is acceptable as a theory course.

- Just as we expect all students obtaining a S.M. to have experience with the theoretical foundations of computer science, we expect all students to have some knowledge of how to build large software or hardware systems, on the order of thousands of lines of code, or the equivalent complexity in hardware. That experience will be evidenced by coursework. In almost all cases a course numbered CS 26x or CS 24x will satisfy the requirement (exceptions will be noted in the course description on my.harvard). Students may also petition to use CS 161 for this requirement. For projects in other courses, the student is expected to write a note explaining the project, include a link to any relevant artifacts or outcomes, describe the student's individual contribution, and where appropriate obtain a note from their class instructor.

- CS 290, 290a/b, 290hfa/b or 2091/2092 cannot be used towards the S.M. degree.

Please note that 200-level courses in fields outside SEAS will be examined carefully. Generally, the CHD is looking for two things in such courses. First, it is expected that the course will be comparable in technical level to a SEAS course. Second, the overall program must be coherent. Taking a course in economics because it might apply to computing is not automatically considered coherent. Taking an economics course in game theory along with appropriate relevant 200-level computer science courses in Artificial Intelligence that apply that theory could be part of a coherent program.

- PhD students' questions can be directed to the Director of Graduate Education, John Girash or to the Computer Science Director of Graduate Studies at [email protected] .

Students seeking an S.M. in Computational Science and Engineering or in Data Science should refer to the programs' specific requirements . Questions can be directed to the Daniel Weinstock , Director for Master's Education.

There are no additional course requirements beyond the SEAS-wide requirements. Harvard Ph.D. and AB/SM students seeking an S.M. in Engineering Sciences should construct a cohesive program plan in the appropriate subfield ( Bioengineering, Electrical Engineering , Environmental Science and Engineering, or Materials Science and Mechanical Engineering) with their assigned SEAS graduate advisor.

In Academic Programs

- Non-Resident and Part-Time Study

- CHD Meeting Schedule

- PhD Overview and Timeline

- PhD Course Requirements

- PhD Program Plans

- Teaching: G2 year

- Qualifying Exam: by end of G2 year

- Research Advisors, Committees, and Meetings

- Dissertation and Final Oral Exam

- SM and ME Program Plans

- Masters Thesis and Supervisor

- SM degree en route to the PhD

- Graduate Student Forms

- Teaching Fellows

- External Fellowships List

- COVID-19 Graduate Program Changes (archived)

No course completed with a grade less than C (for the S.M. degree) or B- (for the M.E.) may be included in the Program Plan; the average grade of the courses on the Program Plan must be a “B” or higher.

For regular (terminal) masters students, failure to maintain a cumulative 3.00 or better average grade or receipt of any unsatisfactory grade may require that the student withdraw from the program, thus terminating degree candidacy.

A regular S.M. candidate whose average grade at the end of the first semester is between 2.50 and 3.00 normally will be warned that they will not complete the requirements for the degree at the end of the second semester unless a cumulative 3.00 or better average grade is achieved. Should the student fail to satisfy the requirements for the S.M. degree at the end of the second semester, continuation for a third and final semester will be granted provided there is reasonable assurance that the degree requirements can be completed at the end of that semester. A regular S.M. candidate whose SEAS average grade at the end of the first semester is less than 2.50 but who could achieve a cumulative 3.00 or better average grade at the end of the second semester, working as a full-time student, normally will be warned that continuation for a third and final semester is contingent upon a marked improvement in performance sufficient to provide reasonable assurance that the requirements for the S.M. degree will be completed at the end of the third semester. A regular S.M. candidate who could not achieve a cumulative 3.00 or better average grade at the end of the second semester normally will be required to withdraw at the end of the first semester, thus terminating degree candidacy.

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- HHS Author Manuscripts

EXPLORING REASONS THAT U.S. MD-PHD STUDENTS ENTER AND LEAVE THEIR DUAL-DEGREE PROGRAMS

Devasmita chakraverty.

Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad, Ahmedabad, India

Donna B. Jeffe

Washington University in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO, U.S.A.

Katherine P. Dabney

Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, VA, U.S.A.

Robert H. Tai

University of Virginia, Charlottesville, VA, U.S.A.

Aim/Purpose

In response to widespread efforts to increase the size and diversity of the biomedical-research workforce in the U.S., a large-scale qualitative study was conducted to examine current and former students’ training experiences in MD (Doctor of Medicine), PhD (Doctor of Philosophy), and MD-PhD dual-degree programs. In this paper, we aimed to describe the experiences of a subset of study participants who had dropped out their MD-PhD dual-degree training program, the reasons they entered the MD-PhD program, as well as their reasons for discontinuing their training for the MD-PhD.

The U.S. has the longest history of MD-PhD dual-degree training programs and produces the largest number of MD-PhD graduates in the world. In the U.S., dual-degree MD-PhD programs are offered at many medical schools and historically have included three phases—preclinical, PhD-research, and clinical training, all during medical-school training. On average, it takes eight years of training to complete requirements for the MD-PhD dual-degree. MD-PhD students have unique training experiences, different from MD-only or PhD-only students. Not all MD-PhD students complete their training, at a cost to funding agencies, schools, and students themselves.

Methodology

We purposefully sampled from 97 U.S. schools with doctoral programs, posting advertisements for recruitment of participants who were engaged in or had completed PhD, MD, and MD-PhD training. Between 2011-2013, semi-structured, one-on-one phone interviews were conducted with 217 participants. Using a phenomenological approach and inductive, thematic analysis, we examined students’ reasons for entering the MD-PhD dual-degree program, when they decided to leave, and their reasons for leaving MD-PhD training.

Contribution

Study findings offer new insights into MD-PhD students’ reasons for leaving the program, beyond what is known about program attrition based on retrospective analysis of existing national data, as little is known about students’ actual reasons for attrition. By more deeply exploring students’ reasons for attrition, programs can find ways to improve MD-PhD students’ training experiences and boost their retention in these dual-degree programs to completion, which will, in turn, foster expansion of the biomedical-research-workforce capacity.

Seven participants in the larger study reported during their interview that they left their MD-PhD programs before finishing, and these were the only participants who reported leaving their doctoral training. At the time of interview, two participants had completed the MD and were academic-medicine faculty, four were completing medical school, and one dropped out of medicine to complete a PhD in Education. Participants reported enrolling in MD-PhD programs to work in both clinical practice and research. Very positive college research experiences, mentorship, and personal reasons also played important roles in participants’ decisions to pursue the dual MD-PhD degree. However, once in the program, positive mentorship and other opportunities that they experienced during or after college, which initially drew candidates to the program was found lacking. Four themes emerged as reasons for leaving the MD-PhD program: 1) declining interest in research, 2) isolation and lack of social integration during the different training phases, 3) suboptimal PhD-advising experiences, and 4) unforeseen obstacles to completing PhD research requirements, such as loss of funding.

Recommendations for Practitioners

Though limited by a small sample size, findings highlight the need for better integrated institutional and programmatic supports for MD-PhD students, especially during PhD training.

Recommendations for Researchers

Researchers should continue to explore if other programmatic aspects of MD-PhD training (other than challenges experienced during PhD training, as discussed in this paper) are particularly problematic and pose challenges to the successful completion of the program.

Impact on Society

The MD-PhD workforce comprises a small, but highly -trained cadre of physician-scientists with the expertise to conduct clinical and/or basic science research aimed at improving patient care and developing new diagnostic tools and therapies. Although MD-PhD graduates comprise a small proportion of all MD graduates in the U.S. and globally, about half of all MD-trained physician-scientists in the U.S. federally funded biomedical-research workforce are MD-PhD-trained physicians. Training is extensive and rigorous. Improving experiences during the PhD-training phase could help reduce MD-PhD program attrition, as attrition results in substantial financial cost to federal and private funding agencies and to medical schools that fund MD-PhD programs in the U.S. and other countries.

Future Research

Future research could examine, in greater depth, how communications among students, faculty and administrators in various settings, such as classrooms, research labs, and clinics, might help MD-PhD students become more fully integrated into each new program phase and continue in the program to completion. Future research could also examine experiences of MD-PhD students from groups underrepresented in medicine and the biomedical-research workforce (e.g., first-generation college graduates, women, and racial/ethnic minorities), which might serve to inform interventions to increase the numbers of applicants to MD-PhD programs and help reverse the steady decline in the physician-scientist workforce over the past several decades.

Introduction

Traditional doctoral training for the PhD involves time for trainees to learn to combine their knowledge of course content and research skills to produce original research, culminating with a doctoral dissertation ( Lovitts, 2005 ). Typically, the average time of PhD-degree completion varies from 4-6 years ( Bourke et al., 2004 ). The MD-PhD (Doctor of Medicine and Doctor of Philosophy) physician-scientist workforce comprises a relatively small cadre of well-trained physician-scientists with the research skills to address clinical and/or basic science research questions aimed at improving patient care ( Goldstein & Kohrt, 2012 ; Varki & Rosenberg, 2002 ). In the U.S., MD-PhD training during medical school is extensive and lengthy, typically lasting for eight or more years ( Brass et al., 2010 ; Jeffe et al., 2014a ), and MD-PhD program attrition is a cause of concern. To our knowledge, only one study has been conducted to examine factors associated with MD-PhD program attrition ( Jeffe et al., 2014a ), and no studies have purposely examined MD-PhD students’ own reasons for leaving their MD-PhD program.

To fill a gap in the literature, we examined attrition from MD-PhD training programs in the U.S., where such training programs were first developed in the 1950s to increase the number of physician-scientists in the biomedical-research workforce (Harding et al., 2017) and where integrated dual-degree MD-PhD programs are the most prevalent. For the award period from July 1, 2019 through June 30, 2020, 50 of 154 U.S. Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)-accredited medical schools had dual-degree MD-PhD programs that were funded by the U.S. National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences (NIH NIGMS) Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) ( National Institute of General Medical Sciences, 2020 ). Many, if not all, MSTP-funded MD-PhD programs as well as non-MSTP-funded MD-PhD programs in U.S. medical schools receive training support from non-federal governmental and private funding organizations, other NIH institutes, and institutional funds to support MD-PhD training ( AAMC, 2009 ; Jeffe et al., 2014a ; Jeffe & Andriole, 2011 ). MD-PhD programs in other countries are small in number relative to the number of MD-PhD programs in the U.S. ( Jones et al., 2016 ; Kuehnle et al., 2009 ; Twa et al., on behalf of the Canadian MD/PhD Program Investigation Group, 2017 ), and many of the nationally supported MD-PhD programs in other countries, such as Switzerland ( Kuehnle et al, 2009 ) and Germany ( Bossé et al., 2011 ), allow for PhD training to begin after receipt of the MD. A 2016-2017 survey of the European MD/PhD Association programs in multiple countries examined MD-PhD program characteristics in association with MD-PhD students’ and graduates’ opinions about the program, their career choices and outcomes ( dos Santos Rocha et al., 2020 ); but we found no studies published that examined MD-PhD students’ self-reported reasons for leaving the MD-PhD program prior to completion.

This exploratory study therefore sought to answer the following research questions: “For MD-PhD students who discontinued their training, what motivated them to pursue MD-PhD training? Additionally, at what point during training and for what reasons did they discontinue their training?”

Literature Review

Md-phd programs typically involve three phases:.

two years of pre-clinical training in medical school, at least four years of PhD research training in graduate school, and two more years of clinical training after returning to medical school ( Brass et al., 2010 ; Jeffe et al., 2014a ). Acceptance to MD-PhD dual-degree programs is very competitive, and MD-PhD graduates have a greater planned career involvement in research at the time of medical-school graduation compared with all other MD graduates ( Andriole et al., 2008 ), especially in disease-oriented and clinical research ( Ahn et al., 2007 ; Andriole et al., 2008 ).

Not all students who matriculate into MD-PhD programs complete the program ( Jeffe et al., 2014a ; National Institutes of Health National Institute of General Medical Sciences [NIH-NIGMS], 1998 ). In an earlier survey study, more than one-fourth of enrolled MD-PhD students seriously considered leaving the program ( Ahn et al., 2007 ). In a survey of 24 MD-PhD programs ( Brass et al., 2010 ), attrition rates were reported to range from 3-34%. In a national cohort study of MD-PhD program enrollees at time of matriculation, the attrition rate was observed to be 27% ( Jeffe et al., 2014a ). By comparison, the attrition rate among MD-only students in the U.S. is about 3% ( Association of American Medical Colleges [AAMC], 2012 ; Garrison et al., 2007 ). PhD enrollment and completion rates vary across universities, fields, countries, and demographic factors such as sex ( Dabney et al., Tai, 2016 ); national-level data on PhD-program attrition is not well-documented. An Australian study collected data from approximately 1,200 students enrolled at one university to find a completion rate of 70% ( Bourke et al., 2004 ). In another study, attrition data were collected in 2013-2014 in a survey of more than 1,500 psychology programs in the U.S. and found doctoral attrition rates between 5-13% ( Michalski et al., 2016 ). Dropout rates during PhD training have been reported to be between 40% and 60% ( Geiger, 1997 ; Tinto, 1987 ). The odds of PhD student dropout in STEM is most in the first year and greater for women ( Lott et al., 2009 ). One study about underrepresented racial/ethnic minority (URM, including Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, and American Indian/Native American) students in STEM that collated PhD completion rates for ten years found Black and Hispanic students to have PhD completion rates of 50% and 58%, respectively ( Okahana et al., 2016 ).

While navigating the preclinical, research, and clinical phases of training, MD-PhD students face unique challenges different from MD-only or PhD-only students ( Chakraverty et al., 2018 ). More MD-PhD than MD students anticipate or experience challenges to balancing training and family life ( Kwan et al., 2017 ). Students also find that the tripartite model of MD-PhD dual-degree programs in the U.S. and Canada creates challenges, having to navigate two transitions between training phases ( Bossé et al., 2011 ; Chakraverty et al., 2018 ), which most students in MD-only or PhD-only programs do not experience. Among the challenges experienced by MD-PhD students having to transition between the phases are time away from the clinical environment, which could impact students’ preparedness for clinical clerkships ( Goldberg & Insel, 2013 ) as well as a lack of desired mentoring (especially mentoring by MD-PhD faculty), a perceived lack of curricular integration and of awareness of phase-specific cultural differences, and difficulties assimilating with other trainees during the research- and clinical-training phases, who are not from their original cohort of peers ( Chakraverty et al., 2018 ).

Large national cohort studies have examined educational experiences of MD-PhD students as well as variables associated with MD-PhD enrollment ( Jeffe et al., 2014b ), attrition ( Jeffe et al., 2014a ), and graduation ( Andriole et al., 2008 ). Individuals who reported participating in high school and college laboratory research apprenticeships, and who highly valued research and finding disease cures as the most important reason to study medicine were more likely to enroll in MD-PhD programs, demonstrating alignment of students’ attitudes and interests with MD-PhD program goals ( Jeffe et al., 2014b ; Tai et al., 2017 ). Students who planned substantial career involvement in research at graduation were more likely to be MD-PhD program graduates than all other-MD program graduates; controlling for other variables in the regression model, women and URM students were less likely to graduate from MD-PhD (vs. other-MD) programs ( Andriole et al., 2008 ). In another study of 2,582 MD-PhD program enrollees, 1,885 (73%) had completed the MD-PhD program, 597 (23%) dropped out of the program but completed the MD, and 100 (4%) left medical school entirely ( Jeffe et al., 2014a ). Although students who enrolled in MD-PhD programs at medical-school matriculation and planned substantial career involvement in research at that time were less likely to leave the MD-PhD program, students who had lower Medical College Admission Test scores, attended medical schools without NIH NIGMS MSTP-funded MD-PhD programs, and were older at matriculation were more likely to leave their MD-PhD program. Notably, women and URM students were neither more nor less likely to leave the MD-PhD program and graduate with only an MD degree ( Jeffe et al., 2014a ). Students’ MD-PhD program satisfaction was reported to be higher at the beginning of the program and lower during the research phase, due to the unpredictability of time to complete the PhD ( Ahn et al., 2007 ).

Although research has examined challenges faced by potential MD-PhD program applicants ( Kersbergen et al., 2020 ) and by MD-PhD students during their training as described above, to our knowledge, no study has examined the reasons why MD-PhD students leave the program before completing their training using a qualitative research approach. Qualitative research can help explain the decision-making process of individuals ( Marshall & Rossman, 2006 ), adding to our understanding of reasons for leaving the program from participants’ perspectives of their personal experiences. We examined attrition from MD-PhD dual-degree programs using a lens of integration and interaction ( Kong et al., 2013 ) to better understand why some U.S. MD-PhD students ultimately discontinued their training.

The data for this paper were collected for a larger qualitative study (Transitions in the Education of Minorities Underrepresented in Research) conducted in the U.S. between 2010 and 2014. This larger study examined training experiences of doctoral students and postdoctoral trainees planning to pursue careers in the biomedical-research workforce to identify factors that served to facilitate or impede progress along this career path ( Andriole et al., 2015 ; Chakraverty, 2013 ; Chakraverty et al., 2018 ; Jeffe et al., 2014a ; Jeffe et al., 2014b ; Tai et al., 2017 ). In all, we conducted 217 interviews with PhD, MD, and MD-PhD students, postdocs, physician-scientists, and faculty in U.S. higher education biomedical-science PhD programs and in MD-PhD dual-degree programs in U.S. medical schools.

Methodological considerations for conducting a qualitative study were governed by the aims of the larger study to more deeply understand participants’ reasons for considering doctoral-level training in the biomedical sciences in pursuit of a research career and for attrition from MD-PhD training specifically, if applicable, which is the focus of the current study. Using a phenomenological approach, we examined how participants made their decisions to enter or leave their training programs ( Marshall & Rossman, 2006 ). Semi-structured, in-depth interviews allowed us to gather detailed narratives to learn more about all participants’ decision-making processes to enter and either complete or leave their doctoral training ( DiCicco-Bloom & Crabtree, 2006 ). Although this paper focuses on attrition from the MD-PhD program, we also analyzed data for these participants’ reasons for enrolling in the MD-PhD program, to gain a more holistic understanding of their experiences and decision-making processes.

Data Collection and Analysis

Study sample and eligibility.

Following Institutional Review Board approval at the University of Virginia and Washington University in St. Louis, we purposefully sampled ( Marshall & Rossman, 2006 ; Miles & Huberman, 1994 ) U.S. public and private higher education institutions offering biomedical-science PhD degrees and medical schools with dual-degree MD-PhD programs. We sought to interview individuals training for or currently engaged in biomedical research; we also wanted to interview MD-PhD program trainees who dropped out of their program before graduation. We included higher education institutions with the Carnegie classification ( The Carnegie Classification of Institutions of Higher Education, n.d. ), indicating high or very high research activity. Deans and department chairs disseminated information about the study with our contact information, using emails, announcements, posters, and flyers. We also recruited participants through snowball sampling (Bogdan & Biklen, 2007; Sadler et al., 2010 ), asking current participants if they would be willing to share our contact information with their colleagues or other students in their program, as well as with individuals who had left their program, and to encourage them to participate in this study. We scheduled phone interviews with individuals who contacted us expressing an interest to participate.

Of 217 participants interviewed in the larger study, 29 students were then currently enrolled in an MD-only program, 20 in a PhD-only program, and 68 in an MD-PhD program; in addition, 25 participants were postdoctoral trainees at the time of the study. Participants no longer in school included 56 faculty, 14 non-scientists, 4 scientists outside academia, and one participant who dropped out of the MD-PhD program before completing either degree. For the current study about MD-PhD program attrition, anyone who had once enrolled in an MD-PhD program but did not complete it was eligible to participate. Overall, seven participants had been enrolled in dual-degree MD-PhD programs but subsequently discontinued MD-PhD training, six of whom continued their training for the MD. The current analysis examines the training experiences of those seven participants and reasons for discontinuing MD-PhD training, which was a specific aim of the larger study.

Semi-structured interviews

A semi-structured interview format allowed us some flexibility in asking question better tailored to an individual’s life experiences ( Cohen & Crabtree, 2006 ), although we asked everyone a basic set of questions, ( Table 1 ). Each participant completed one, 45-60 minute semi-structured telephone interview following their informed consent. The interview questions were developed based on the overall study aims, one of which focused on reasons for MD-PhD attrition. The interview protocol and questions were developed by the principal investigators and co-investigators based on their knowledge of gaps in the literature and understanding of the field; interview questions were reviewed by content experts and pilot tested before the initiation of data collection.

Interview Questions Asked of Participants

Specially trained interviewers, including faculty and PhD students on the research team, conducted interviews for this study. Demographic data such as age, sex, race/ethnicity, and current program were collected at the beginning of each interview. Interviews were audio-recorded with permission, transcribed verbatim through a professional company, and assigned an alpha-numeric code prior to analysis. For this aim of the study focusing on MD-PhD students’ reasons for leaving the MD-PhD program, in-depth interviews were conducted to gain insight into participants’ backgrounds, experiences, reasons for enrolling in MD-PhD programs, and when and why they discontinued their MD-PhD training through their own narratives ( Kvale & Brinkmann, 2009 ). We sought to identify aspects of the training that might have been particularly problematic for these participants. Probing questions were asked based on participants’ responses. All the authors have directly conducted or aided in medical education research for varying lengths of time. At the end of each interview, participants were asked to broadly share information about the study in their professional and personal networks, so that people from a wider network would become aware of this study using snowball sampling (Bogdan & Biklen, 2007; Sadler et al., 2010 ).

Analytic strategy

Each interview transcript was open-coded by two authors, both for narratives about their reasons for enrolling in the MD-PhD program and for leaving the program. The coders created a single codebook after discussing and resolving disagreements about codes, compiling all the codes into a final list that was used to reanalyze all the interviews. Since attrition MD-PhD program attrition is a relatively understudied topic, codes were based on participant transcripts rather than existing literature. Using an inductive, thematic approach as the primary analysis strategy ( Miles & Huberman, 1994 ; Pope et al., 2000 ) and the constant comparative method of coding ( Glaser & Strauss, 1967 ), the codes were systematically organized into themes ( Thomas, 2006 ). Themes that emerged from the analysis are presented if experiences fitting in a theme were discussed by multiple participants. Although some reasons described during the interview were unique for a participant, we elaborate only on those recurrent themes and experiences that were common across multiple participants. Both coders were mindful of the fact that their worldviews and positionalities could differ from those of the participants, interviewers, and from each other, which could influence how the interviews were conducted and data were analyzed ( Antin et al., 2015 ). Both coders were a part of the interview team and are educational researchers with a background in higher education and medical education research; they used a reflective journal, recording memos to document their coding decisions during analysis and acknowledge any disconfirming evidence. The coders also consulted with each other to ensure agreement on coding. They resolved coding disagreements through a discussion and consensus. The coding and analysis process lasted roughly seven months. We present representative quotes that exemplified the emergent themes, adding content in brackets to clarify a participant’s narrative. We used pseudonyms for those participants whose results are described in this manuscript.

Of the seven participants who had left the MD-PhD program before completion, two had completed their MD training and held academic-medicine faculty positions at the time of their interview; four were still in medical school completing the MD degree, and one was completing a PhD in Education ( Table 2 ). Since the sample size was small, our findings are exploratory; we did not expect to reach data saturation, a stage when no new themes emerge as a result of further data collection ( Faulkner & Trotter, 2017 ; Glaser & Strauss, 1967 ). Although there were similarities in the reasons that participants gave for entering MD-PhD training, each participant described slightly different circumstances and stages during which they left MD-PhD training.

Participant Demographics, Timing of MD-PhD-program Attrition, and Status at Time of Interview

Why participants entered MD-PhD training?

We asked participants what inspired them to pursue MD-PhD training in the first place. All seven participants provided reasons that included both a desire to help people on a day-to-day basis through clinical practice and to more deeply engage in research. Having the MD-PhD dual degree was perceived as a way to broaden research opportunities to participate in clinical and other types of research as well as get access to patient populations. For all participants, the desire to pursue a research career grew from undergraduate research opportunities that they had experienced; such opportunities led to publishing and presenting at conferences, networking with established researchers, and getting to know “what their careers were like” (Debbie). Ben had “a pretty thorough research experience” in college where he “worked every summer in the research lab” and had already published research by the time he finished college. Aaron described an undergraduate mentor who was “a very good chemist and a wonderful teacher” who taught him “how research is done and the rewards of doing research.” A fulfilling college research experience also provided participants with the skills to handle research responsibilities, independently decide what experiments to conduct, and develop ownership of the work—factors that made participants consider studying for an MD-PhD.

In college, it became much more concrete, this idea that I wanted to do research and medicine, and try and incorporate the two. The experience gave me this little niche to be working in and got me really excited about what scientists do. (Eva)

During college, participants reported having opportunities to give presentations at national conferences and to gain insight into clinical experiences by shadowing physicians, and volunteering to help children with special needs. Such experiences shaped one’s desire to pursue MD-PhD as opposed to MD-only or PhD-only. Eva, who wanted to combine medical training with research training shared, “as much as I like the research and thinking about science, I wasn’t cut out to just be in the lab all the time by myself.”

Participants were also influenced by undergraduate mentors who provided hands-on research experience by “letting me have my own little section of the project.… He said, ‘Here's a part of the project. I want you to figure this thing out.’ I think that’s what really sparked my enthusiasm for basic science” (Francesca). Overall, Eva realized that receiving both the MD and PhD would help “produce new knowledge and provide independence” and the “thrill of discovery.” College mentors also helped select and apply to MD-PhD programs and provided information about how one could combine patient care and research if they had the dual MD-PhD. Gerald noted, “The premed adviser at the house [dormitory] was an MD-PhD. He did have a relatively big influence on my decision to pursue MD-PhD.” A dual-degree meant that “I don’t have to give up one side of something that I find exciting and want to explore.”

Participants were motivated by a combination of positive research experiences and personal reasons to pursue the MD-PhD. For example, Debbie shared,

After college I worked as a research technician in a lab studying HIV, and I worked with a lot of physicians who also did research. I sort of liked the idea of the variety in their careers, so I was looking into programs that would allow me to see patients plus do research, and that was how I decided to apply to [the] MD-PhD program.

Personal or family reasons also was a motivation for pursuing MD-PhD. Gerald reasoned, “my grandma was often sick in the nursing home. Going back and forth from the hospital to the nursing home to home. I wanted to help people like her.”

In summary, participants wanted to pursue MD-PhD to be able to work in two worlds—clinical practice and research. Clearly, very positive college research experiences, mentorship, and personal reasons also played big roles in participants’ decisions to pursue the dual MD-PhD degree. And for some, the icing on the cake was the lure of opportunities to participate in a variety of professional activities that they could enjoy as an MD-PhD. So what happened to make these individuals change their minds?

Why participants left the MD-PhD training?

Aaron and Eva left their MD-PhD program at the end of second year without starting the PhD training phase at all; the other five participants completed some of their PhD training before discontinuing the MD-PhD program ( Table 2 ). Once in the program, the influence of positive role models and opportunities that drew candidates to the program was weakened by a variety of factors. Four recurrent themes emerged from the data with regard to participants’ reasons for leaving the MD-PhD program without completing the requirements for both degrees ( Table 3 ), which we describe below.

“Why participants left MD-PhD training?”: Frequency for Each Theme

Declining interest in research

Three participants (Aaron, Debbie, and Eva) shared that although they joined an MD-PhD program to pursue research as well as clinical care, their interest in research and earning a PhD declined shortly after starting the program, which contributed to their decisions to leave the program. At the time of the interview, Aaron was a faculty of clinical research at a medical school and in his sixties (describing experiences from his twenties), and Eva was a second-year medical student in her twenties. Yet, both shared similar experiences of a decline in interest in research following the first few research rotations during their MD-PhD training. Both left their MD-PhD program at the end of their second year of medical school, without formally starting PhD training at all, although both had pursued summer research opportunities during medical school.

For both, it was a combination of being exposed to interesting clinical problems during MD pre-clinical phase, summer rotations shortly after that did not yield research, and a declining interest in research, where “All of a sudden, the PhD just didn’t seem like the thing that I wanted to do anymore, even though when I applied a year and a half ago, I was super excited about it” (Eva). In both cases, lab rotations did not fit research interests, creating doubts about how attractive the PhD would be. Both had an enriching research experience in college that contributed to their decision of doing an MD-PhD. However, once the program started, the excitement:

sort of fizzled. I couldn’t really find something that would keep me interested in that same way. … I was less than thrilled about what I was doing. That was why I first started questioning what I am looking to get out of this. (Eva)

Aaron did not want to put his clinical training on hold after two years and “take off three or four years to go into a lab when I didn’t have a hot project that I was totally enthused about, having had my project from the prior summer sizzle out.” He felt frustrated “not having something [in research] that I had a lot of enthusiasm for. I’d heard about all these fascinating clinical issues and conditions and examined just a couple of patients and thought that was very exciting.” That led him to gravitate towards only the MD degree. The structure of MD-PhD program felt illogical, “giving you the preparation for going into clinics and then saying, ‘Okay, we’ll put that on hold for four years and let’s go do research,’” Aaron shared. At the end of two years, when their MD-PhD cohort split with the rest of the MD classmates, he decided to only continue his clinical training.

This was also largely as a result of positive pre-clinical experiences where both Aaron and Eva learnt a lot from the preceptorship in the first year, an elective mentored experience where one was paired up with a physician to shadow and be involved in doing interviews and physical exams with patients. Debbie, who left after the third year of the MD-PhD program (after two years of medical school and one year of PhD) did that due to the uncertainty of producing research results and lengthy training for the PhD. At the start of her MD-PhD program, she “loved the medical school curriculum and working with other medical students.” However, when she started her PhD training at the beginning of third year, she did not like research as much and felt underprepared for research compared to her MD-PhD peers. She was “leaning more towards medicine” and “didn’t quite fit the MD-PhD profile.” She shared being “not excited everyday by going to the lab, the way I am excited to go to the hospital every day. I just felt like I was missing something. I was unhappy and frustrated doing research.” She realized that she enjoyed clinical training more than research, did not feel as prepared or enthused about getting a PhD by the third year, and felt out of place in the research lab. Like Eva, Debbie would prefer conducting research during residency rather than continuing training for the PhD and ultimately being responsible for running a research lab as a principal investigator.

Isolation and lack of social integration during the different training phases

Social integration broadly describes the ways in which MD-PhD students were able to assimilate into the different cultures during the various training phases. Students described the challenges they experienced and ability to interact with other MD-PhD students as well as with PhD-only and MD-only students during the respective research- and clinical-training phases. Five participants (Ben, Carrie, Eva, Francesca, and Gerald) described challenges in integrating socially in different phases of the MD-PhD program that eventually contributed to their decision of leaving the MD-PhD program. Lack of both family and peer interaction contributed to feelings of isolation.

Family interaction:

There were feelings of isolation due to living far away from family and a cohesive community with which they were familiar. Eva shared that eventually, the novelty of MD-PhD went away and stress related to how long the training was going to take set in. None of the seven participants had an immediate family member in medicine, and four of them were first-generation college students. Having a physician parent might have provided participants with more opportunities and resources to understand and feel comfortable with the demands MD-PhD training. There was a “disconnect in how much my family understands about what I’m doing here at school,” shared Eva. Families sometimes did not understand the academic pressures or the purpose of undergoing such a long training. Although participants reported they did not get much family support while pursuing MD-PhD, Ben shared that he received family support when he decided to leave the program.

Peer interaction:

Isolation due to poor peer interactions started as early as by the second year of MD-PhD training. Socialization opportunities during PhD were inadequate and not as fulfilling, making “the cultural transition from medicine to science a very hard one” (Francesca). It was difficult to mingle with PhD-only students who had already gone through a year of classes and lab rotations with other PhD students and had formed their groups. Participants felt like outsiders in the PhD program. Francesca felt frustrated interacting “with the same five people all day, every day. I was feeling isolated from other people.”

I loved interacting with the patients. I loved the immediacy of medicine. It was a slow realization for me over the last year and a half that I was in the lab that I was much more passionate about the day-to-day work of medicine than I was about the day-to-day work of science. I think part of it as the sort of solitary nature of it [lab research]. I feel like I’m more of a people person than I could be while I was in the lab. (Francesca)

Lack of a social circle was also a challenge, Gerald shared not having “close friends who were doing it [completing MD-PhD training]. Maybe that would have given me more insight into the day-to-day life and might have swayed me a different way.” When a large cohort of MD-PhD students split up to go to different departments during their PhD training, daily interactions with fellow MD-PhD students decreased for him.

Ben felt like being in a difficult environment and a “strange, no-man’s land” to work where neither the MD nor the PhD students considered MD-PhD students one of their own.

[It was like a] cold war between the MD and the PhD faculty at a medical school. The PhDs feel that their degree is of slightly higher rank than an MD and should be treated thus. In a medical school, the MDs insist that [they rank higher]. Both sides feel that they should be in charge, and the other ones are the secondary people. (Ben)

Carrie felt that it would be less stressful if she left PhD training since she had not met a single MD-PhD graduate who was happy. MD students “looked down” on MD-PhD students, considering them to be poor clinicians “because you split your time doing research” and “the PhD did not help in the clinic,” she shared, adding that fellow PhD students did not consider MD-PhDs as serious researchers, saying that MD-PhD students’ “research training was watered down.” Both Carrie and Francesca felt that students in each phase were territorial. Carrie described an “us-against-them mentality”—where MD students considered the PhD-phase of the MD-PhD program as “getting a vacation,” and PhD students were of the opinion that “this isn’t med school where people will hold your hand and spoon-feed you what you need to know.” Francesca felt the cultural transition to the PhD program and the several-year-long gap in medical training were formidable challenges.

In addition to unsatisfactory peer-interactions, Eva eventually realized she enjoyed the daily interactions she experienced working in a hospital more than while conducting research, “which is very much sort of intellectual and introverted. What changed most were the internal factors about what I want out of my career and my life.”

Suboptimal PhD-advising experiences

Three participants (Ben, Carrie, and Gerald) described several challenges related to inadequate mentoring and PhD-advising that contributed to their decision to leave the program. Lack of adequate mentoring during a very regimented MD-PhD training was a widely discussed challenge. Those who left the program described the mentoring they received as minimal, inadequate, sparse, and hands-off. Advisers did not always help in coping with the stress of a long training process, especially during PhD when students had already spent a few years in the program. This was especially discouraging for first-generation students who had received no guidance at home. “Nobody asked if there were problems down there [in the PhD lab] until I did my resignation letter, and then they’re like, ‘Oh, well, what can we do to get you to stay?’ At this point, nothing,” shared Carrie.

Students lacked the bigger picture of what an MD-PhD would be doing ten years down the line, the MD-PhD’s perspective on career development and how to handle training challenges, which could only be provided by MD-PhD advisers (compared to advisers with an MD-only or PhD-only degree). Female MD-PhD students sought female MD-PhD advisers to understand how to achieve work-life balance, who were even rarer to find. Overall, MD-PhD advisers were hard to find.

In addition to bad experiences with PhD advisers and lack of MD-PhD advisers overall, a positive experience with an MD preceptor actually steered students away from a PhD towards an MD-only program. Overall, conflicts arose when adviser and student’s professional goals and values did not match. This happened when a PhD adviser only trained students to become the next generation of principal investigators in a basic science research lab, while that was not the goal for an MD-PhD student. This mismatch made the relationship uncomfortable, especially when advisers “expressed negative opinions of medical students” and treated them more like an employee, shared Gerald.

Ben shared that many PhD advisers were “hostile to the fact that I was an MD-PhD student” and “wore a chip on their shoulder all the time over their position vis-a-vis the doctors. That was just generally a difficult environment to function in.” PhD advisers especially made a difference in a good or bad way because the PhD training process itself was long, with years of research not always yielding publishable results. Given this uncertainty, having young, inexperienced, and pre-tenure PhD advisers further posed challenges, created negative experiences, and discouraged MD-PhD students from completing a PhD. Ben eventually lost his PhD support and was “kicked out against my will for having made inadequate progress” in research. He shared that PhD advisers had “full authority to judge on any criteria they want whether someone has made adequate progress,” and there was no legal defense against that, even if certain committee members did not agree with the decision to expel a student. Often, when a PhD collaboration between faculty and MD-PhD student did not work out, it was difficult to identify another PhD adviser because of smaller MD-PhD programs (compared to PhD-only programs) with fewer available faculty.

When there was lack of MD-PhD advisers, having a better adviser in one phase could disproportionately shift the balance and make students want to complete that part of the training. Gerald had issues working with his PhD adviser, but his MD mentor was very supportive and “willing to meet with me any time to discuss how things are going in medical school, getting back into study habits for medical school after being out for four years.”

Unforeseen obstacles to completing PhD research requirements

Four participants (Ben, Carrie, Francesca, and Gerald) described various unforeseen circumstances that they experienced while completing research requirements during the PhD-phase, which contributed to their decision to leave MD-PhD training. Gerald was in his sixth year (two years of MD and four years of PhD) when he left MD-PhD training. At the beginning of PhD training, none of the lab rotations culminated into a fruitful experience to facilitate completing PhD. Sometimes, “animal models did not work,” forcing one to abandon experiments after many years of effort.

It [the animal model] was still expressing the gene. It was still making the protein, but the phenotypes that…. were no longer there. After several generations of outbreeding were still not there. I was the only person using this model. (Gerald)

Experimental failures created tension between Gerald and committee members because “there was kind of a disconnect between what the rest of my committee expected and what my mentor was able to support.” Even when the program advised to start a new project, it was not possible; Gerald’s PhD adviser “didn’t really have the time or the energy to get that [a new project] off the ground.” Lack of time became a challenge.

I had two weeks to write a completely detailed proposal on this new project. Based on my experience just working with the phenotype and the amount of time and energy that went into that, then looking at [how to] be able to get this new project finished, it would’ve required even more time and energy. It no longer seemed feasible to me. (Gerald)

The possibility of joining a different lab was also eliminated due to time constraints. Francesca, who was in her eighth year of training (two years of MD and six years of PhD) when she left the program, continued to lose more time when the PhD adviser moved to a different university and there were facility-based technical problems.

They constructed [for] us a containment facility instead of a clean room for some of the work, so the airflow was backwards, and all the cultures got contaminated for months. I think I probably lost about nine months with the move and getting all these things straightened out again. (Francesca)