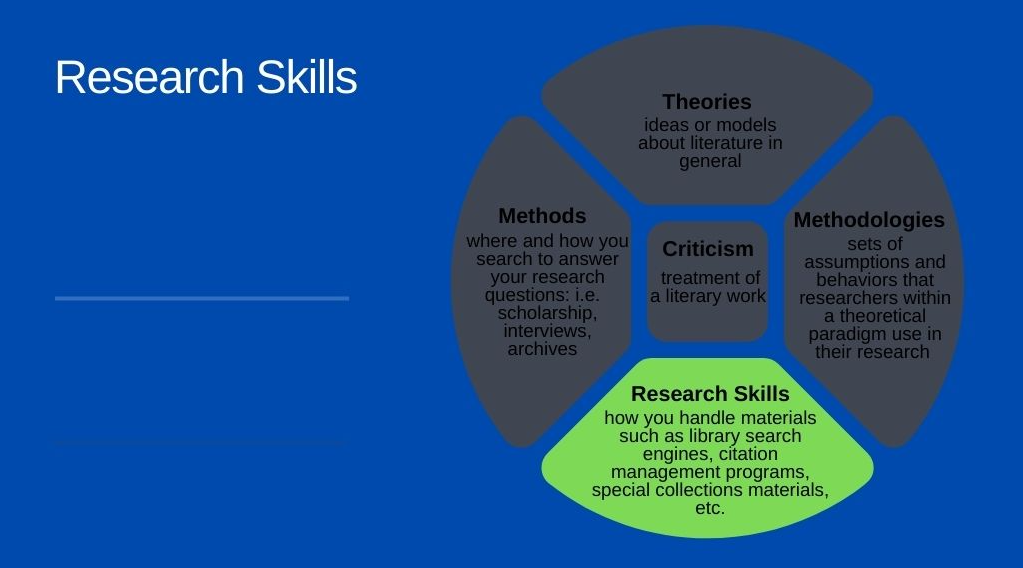

Research Skills

Barry Mauer and John Venecek

We discuss the following topic on this page:

We also provide the following activity:

Research Skills [Refresher]

Research skills are all about gathering evidence. This evidence , composed of facts and the reasoning that connects them, aims to convince your audience to accept your conclusions about the literary work. The most important piece of evidence you need to discuss is the literary work itself, which is a “fact” that you and your audience can examine together. Research means finding additional facts about the literary work and tying them together with reasoning to reach a significant and convincing conclusion.

Literature often presents us with factual difficulties. Sometimes authors revised their works and multiple versions exist. William Blake printed his own works and often changed illustrations and words between each printing. If we are reading a translated work, there may be more than one translation. In other words, we first need to identify which literary “object” we are studying. Electronic databases, such as the William Blake Archive , provide scholars with multiple versions of literary works, as well as plenty of reference sources. They are great places to begin a study!

The kind of evidence we need is directly related to the kind of claim we are making. If we want to claim that a literary work has seen a resurgence of public interest, we will look for historical evidence and quantitative evidence (statistics) to show that sales of the work (or database searches, or library checkouts, etc.) have increased. We may also seek qualitative evidence (such as interviews with booksellers and readers) to report on their impressions. We may look to see if there has been an increase in the number and kinds of adaptations. One example of such a work is Denis Perry’s and Carl Sederholm’s edited volume, Adapting Poe: Re-imaginings in Popular Culture (Spring 2012). If we are claiming that a literary work has a special relationship to a geographic region, we will look for textual evidence, geographic evidence, and historical evidence. See for example, Tom Conley’s The Self-Made Map (University of Minnesota Press 1996), which argues that geographic regions of France played a key role in Miguel de Montaigne’s Essais.

Types of Evidence [1]

Your choice of problem, theory, methodology, and method impact the kinds of evidence you will be seeking. Wendy Belcher identifies the following types:

- Qualitative Evidence: D ata on human behavior collected through direct observation, interviews, documents, and basic ethnography (191). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research (2005) is a helpful guide. This area also encompasses audience research. Examples include the journal Reception: Texts, Readers, Audiences, History, the edited volume The Reader in the Text: Essays on Audience and Interpretation (Suleiman, Crosman, eds. 1980), and Media and Print Cultural Consumption in Nineteenth-Century Britain ( Rooney and Gasperini, eds. 2016).

- Quantitative Evidence: Data collected from standardized instruments and statistics, common to education, medicine, sociology, political sciences, psychology, and economics (191). Guides include Best Practices in Quantitative Methods (Osbourne 2007) and Statistics for People Who (Think that They) Hate Statistics (Salkind 2007).

- Historical Evidence: D ata collected from examinations of historical records to uncover the relationship of people to each other and to periods and events, common to all disciplines and collected from archives of primary materials (191). Guides include Historical Evidence and Argument (Henige 2006) and Evidence Explained: Citing History Sources from Artifacts to Cyberspace, 2nd Edition (Mills 2009).

- Geographic Evidence: D ata about people’s relationship to places and environments in fields such as archaeology (191). Guides include Qualitative Research Methods in Human Geography, 5th Edition (Hay and Cope 2021) and Creative Methods for Human Geographers (Benzon, Holton, Wilkinson, eds. 2021).

- Textual Evidence: Data collected from texts about form (genre, plot, etc.), language (diction, rhetoric), purpose (message, function), meaning (symbolism, themes, etc.) and milieu (sources, culture, identity, etc.) (191). Guides include Introduction to Literary Hermeneutics (Szondi 1995) and The Hermeneutic Spiral and Interpretation in Literature and the Visual Arts (O’Toole 2018).

- Artistic Evidence: D ata from images, live performances, etc., used to study physical properties of a work (size, material, form, etc.), purpose (message, function, etc.) meaning (symbolism, etc.), and milieu (sources, culture, etc.) (191). Guides include Interpreting Objects and Collections (Pearce 1994) and Material Culture Studies in America (Schlereth, ed. 1982).

In the following chapters, five through nine, we present instruction for numerous research skills including how to gather research from literary works and from scholarly literature, and other skills such as how to use library search engines, citation management, google scholar, and source evaluation. The main thing to keep in mind for now is that you are gathering quality evidence and putting it together to construct a convincing and compelling argument about a literary work (or works).

For more advice on how to Reason with Evidence, consider the following from WritingCommons.org: [2]

Once you’ve spent sufficient time researching a topic —once you’re familiar with the ongoing scholarly conversation about a topic—then you’re ready to begin thinking about how to reason with the evidence you’ve gathered.

- engage in rhetorical analysis of the outside source(s)

- evaluate the currency, relevance, authority, accuracy, purpose of the outside source(s)

- use evidence (e.g., quoting , paraphrasing , summarizing ) to bolster claims

- introduce sources and clarifying their authority

- use an appropriate citation style

For more advice on how to Connect Evidence to your Claims, consider the following from WritingCommons.org: [3]

We can’t, as writers, just stop at a quote, because our readers won’t necessarily know the connection between the point of your project and the quote. As such, we must make the connection for our reader. Here are a few ways to make such a connection:

- Break down ideas

- Connect back to the thesis

- Connect back to the paragraph’s main point

- Point to the author’s purpose

- In the “Back Matter” of this book, you will find a page titled “Rubrics.” On that page, we provide a rubric for Using Evidence for a Research Project. ↵

- Writing Commons. “Logos - Logos Definition.” Writing Commons , 11 Mar. 2022, https://writingcommons.org/article/logos/ . ↵

- Janechek, Jennifer, and Eir-Anne Edgar. “Connecting Evidence to Your Claims.” Writing Commons , 15 May 2021, https://writingcommons.org/section/citation/how-to-cite-sources-in-academic-and-professional-writing/citation-how-to-cnnect-evidence-to-your-claims/ . ↵

Research Skills Copyright © 2021 by Barry Mauer and John Venecek is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates

Published on January 2, 2023 by Shona McCombes . Revised on September 11, 2023.

What is a literature review? A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources on a specific topic. It provides an overview of current knowledge, allowing you to identify relevant theories, methods, and gaps in the existing research that you can later apply to your paper, thesis, or dissertation topic .

There are five key steps to writing a literature review:

- Search for relevant literature

- Evaluate sources

- Identify themes, debates, and gaps

- Outline the structure

- Write your literature review

A good literature review doesn’t just summarize sources—it analyzes, synthesizes , and critically evaluates to give a clear picture of the state of knowledge on the subject.

Instantly correct all language mistakes in your text

Upload your document to correct all your mistakes in minutes

Table of contents

What is the purpose of a literature review, examples of literature reviews, step 1 – search for relevant literature, step 2 – evaluate and select sources, step 3 – identify themes, debates, and gaps, step 4 – outline your literature review’s structure, step 5 – write your literature review, free lecture slides, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions, introduction.

- Quick Run-through

- Step 1 & 2

When you write a thesis , dissertation , or research paper , you will likely have to conduct a literature review to situate your research within existing knowledge. The literature review gives you a chance to:

- Demonstrate your familiarity with the topic and its scholarly context

- Develop a theoretical framework and methodology for your research

- Position your work in relation to other researchers and theorists

- Show how your research addresses a gap or contributes to a debate

- Evaluate the current state of research and demonstrate your knowledge of the scholarly debates around your topic.

Writing literature reviews is a particularly important skill if you want to apply for graduate school or pursue a career in research. We’ve written a step-by-step guide that you can follow below.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

Writing literature reviews can be quite challenging! A good starting point could be to look at some examples, depending on what kind of literature review you’d like to write.

- Example literature review #1: “Why Do People Migrate? A Review of the Theoretical Literature” ( Theoretical literature review about the development of economic migration theory from the 1950s to today.)

- Example literature review #2: “Literature review as a research methodology: An overview and guidelines” ( Methodological literature review about interdisciplinary knowledge acquisition and production.)

- Example literature review #3: “The Use of Technology in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Thematic literature review about the effects of technology on language acquisition.)

- Example literature review #4: “Learners’ Listening Comprehension Difficulties in English Language Learning: A Literature Review” ( Chronological literature review about how the concept of listening skills has changed over time.)

You can also check out our templates with literature review examples and sample outlines at the links below.

Download Word doc Download Google doc

Before you begin searching for literature, you need a clearly defined topic .

If you are writing the literature review section of a dissertation or research paper, you will search for literature related to your research problem and questions .

Make a list of keywords

Start by creating a list of keywords related to your research question. Include each of the key concepts or variables you’re interested in, and list any synonyms and related terms. You can add to this list as you discover new keywords in the process of your literature search.

- Social media, Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, TikTok

- Body image, self-perception, self-esteem, mental health

- Generation Z, teenagers, adolescents, youth

Search for relevant sources

Use your keywords to begin searching for sources. Some useful databases to search for journals and articles include:

- Your university’s library catalogue

- Google Scholar

- Project Muse (humanities and social sciences)

- Medline (life sciences and biomedicine)

- EconLit (economics)

- Inspec (physics, engineering and computer science)

You can also use boolean operators to help narrow down your search.

Make sure to read the abstract to find out whether an article is relevant to your question. When you find a useful book or article, you can check the bibliography to find other relevant sources.

You likely won’t be able to read absolutely everything that has been written on your topic, so it will be necessary to evaluate which sources are most relevant to your research question.

For each publication, ask yourself:

- What question or problem is the author addressing?

- What are the key concepts and how are they defined?

- What are the key theories, models, and methods?

- Does the research use established frameworks or take an innovative approach?

- What are the results and conclusions of the study?

- How does the publication relate to other literature in the field? Does it confirm, add to, or challenge established knowledge?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of the research?

Make sure the sources you use are credible , and make sure you read any landmark studies and major theories in your field of research.

You can use our template to summarize and evaluate sources you’re thinking about using. Click on either button below to download.

Take notes and cite your sources

As you read, you should also begin the writing process. Take notes that you can later incorporate into the text of your literature review.

It is important to keep track of your sources with citations to avoid plagiarism . It can be helpful to make an annotated bibliography , where you compile full citation information and write a paragraph of summary and analysis for each source. This helps you remember what you read and saves time later in the process.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

To begin organizing your literature review’s argument and structure, be sure you understand the connections and relationships between the sources you’ve read. Based on your reading and notes, you can look for:

- Trends and patterns (in theory, method or results): do certain approaches become more or less popular over time?

- Themes: what questions or concepts recur across the literature?

- Debates, conflicts and contradictions: where do sources disagree?

- Pivotal publications: are there any influential theories or studies that changed the direction of the field?

- Gaps: what is missing from the literature? Are there weaknesses that need to be addressed?

This step will help you work out the structure of your literature review and (if applicable) show how your own research will contribute to existing knowledge.

- Most research has focused on young women.

- There is an increasing interest in the visual aspects of social media.

- But there is still a lack of robust research on highly visual platforms like Instagram and Snapchat—this is a gap that you could address in your own research.

There are various approaches to organizing the body of a literature review. Depending on the length of your literature review, you can combine several of these strategies (for example, your overall structure might be thematic, but each theme is discussed chronologically).

Chronological

The simplest approach is to trace the development of the topic over time. However, if you choose this strategy, be careful to avoid simply listing and summarizing sources in order.

Try to analyze patterns, turning points and key debates that have shaped the direction of the field. Give your interpretation of how and why certain developments occurred.

If you have found some recurring central themes, you can organize your literature review into subsections that address different aspects of the topic.

For example, if you are reviewing literature about inequalities in migrant health outcomes, key themes might include healthcare policy, language barriers, cultural attitudes, legal status, and economic access.

Methodological

If you draw your sources from different disciplines or fields that use a variety of research methods , you might want to compare the results and conclusions that emerge from different approaches. For example:

- Look at what results have emerged in qualitative versus quantitative research

- Discuss how the topic has been approached by empirical versus theoretical scholarship

- Divide the literature into sociological, historical, and cultural sources

Theoretical

A literature review is often the foundation for a theoretical framework . You can use it to discuss various theories, models, and definitions of key concepts.

You might argue for the relevance of a specific theoretical approach, or combine various theoretical concepts to create a framework for your research.

Like any other academic text , your literature review should have an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion . What you include in each depends on the objective of your literature review.

The introduction should clearly establish the focus and purpose of the literature review.

Depending on the length of your literature review, you might want to divide the body into subsections. You can use a subheading for each theme, time period, or methodological approach.

As you write, you can follow these tips:

- Summarize and synthesize: give an overview of the main points of each source and combine them into a coherent whole

- Analyze and interpret: don’t just paraphrase other researchers — add your own interpretations where possible, discussing the significance of findings in relation to the literature as a whole

- Critically evaluate: mention the strengths and weaknesses of your sources

- Write in well-structured paragraphs: use transition words and topic sentences to draw connections, comparisons and contrasts

In the conclusion, you should summarize the key findings you have taken from the literature and emphasize their significance.

When you’ve finished writing and revising your literature review, don’t forget to proofread thoroughly before submitting. Not a language expert? Check out Scribbr’s professional proofreading services !

This article has been adapted into lecture slides that you can use to teach your students about writing a literature review.

Scribbr slides are free to use, customize, and distribute for educational purposes.

Open Google Slides Download PowerPoint

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Sampling methods

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A literature review is a survey of scholarly sources (such as books, journal articles, and theses) related to a specific topic or research question .

It is often written as part of a thesis, dissertation , or research paper , in order to situate your work in relation to existing knowledge.

There are several reasons to conduct a literature review at the beginning of a research project:

- To familiarize yourself with the current state of knowledge on your topic

- To ensure that you’re not just repeating what others have already done

- To identify gaps in knowledge and unresolved problems that your research can address

- To develop your theoretical framework and methodology

- To provide an overview of the key findings and debates on the topic

Writing the literature review shows your reader how your work relates to existing research and what new insights it will contribute.

The literature review usually comes near the beginning of your thesis or dissertation . After the introduction , it grounds your research in a scholarly field and leads directly to your theoretical framework or methodology .

A literature review is a survey of credible sources on a topic, often used in dissertations , theses, and research papers . Literature reviews give an overview of knowledge on a subject, helping you identify relevant theories and methods, as well as gaps in existing research. Literature reviews are set up similarly to other academic texts , with an introduction , a main body, and a conclusion .

An annotated bibliography is a list of source references that has a short description (called an annotation ) for each of the sources. It is often assigned as part of the research process for a paper .

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, September 11). How to Write a Literature Review | Guide, Examples, & Templates. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/dissertation/literature-review/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, what is a theoretical framework | guide to organizing, what is a research methodology | steps & tips, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, what is your plagiarism score.

ALA User Menu

- ALA JobLIST

- Contact ACRL

Breadcrumb navigation

Research competency guidelines for literatures in english.

- Share This Page

Association of College and Research Libraries Literatures in English Section

Originally implemented, October 2004 Revised and approved, June 2007

Replaced by Companion Document to the ACRL Framework for Information Literacy for Higher Education: Research Competencies in Writing and Literature , November 2021

"Research Competency Guidelines for Literatures in English" was first developed for use within the Literatures in English Section (LES) of ACRL. Although based on framework of the "ACRL Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education" (2000), these guidelines address the need for a more specific and source-oriented approach within the discipline of English literatures, including a concrete list of research skills. The original list was compiled by Anne Jordan-Baker (Elmhurst College). The guidelines were further developed by the ACRL Literatures in English Section Ad hoc Committee on Literary Research Competencies.*

On December 10, 2001, the draft guidelines were posted to LES-L, the electronic discussion group, for comments. A revision based on those comments was discussed at the 2002 ALA Midwinter Meeting. The guidelines were also published in the fall 2002 issue of "Biblio-Notes", the LES newsletter, and readers were encouraged to submit comments. A draft based on all information and comments to date was posted to the LES-L group for further review on April 12, 2002. A final draft was presented at the 2002 ALA Annual Conference and was approved by the LES Executive Committee. An updated version of the 2002 draft was distributed to the LES-L members and the Information Literacy Advisory Committee as well as posted on the ACRL Web site. At the 2005 ALA Midwinter Meeting, a hearing was held and the document was further revised to reflect the advice received.

The "Research Competency Guidelines for Literatures in English" draft has been under review and revision during the years in which ACRL was developing policies and procedures for subject-specific information literacy standards. Because of the independent development of these guidelines and ACRL policies, the format and framework of guidelines do not follow the current patterns of information literacy standards. The guidelines draft document has served primarily to facilitate the collaboration of teaching faculty with subject librarians to create effective teaching structures for literary research. An ACRL roundtable discussion at the 11th National Conference is just one example of many in which the subject librarians have shared their success in using the guidelines to improve communication with the faculty they serve.

ACRL Literatures in English Section Planning Committee Chair Kathleen Kluegel, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign January 2007

* ACRL Literatures in English Section Ad hoc Committee on Literary Research Competencies (1999-2001)

Heather Martin, University of Alabama at Birmingham, Chair; Austin Booth, University at Buffalo, SUNY; Charlotte Droll, Wright State University; Louise Greenfield, University of Arizona; Anne Jordan-Baker, Elmhurst College; Jeanne Pavy, University of New Orleans; Judy Reynolds, San Jose State University

Purpose of the Guidelines

- To aid students of literatures in English in the development of thorough and productive research skills

- To encourage the development of a common language for librarians, faculty, and students involved with research related to literatures in English

- To encourage librarian and faculty collaboration in the teaching of research methods to students of literatures in English

- To aid librarians and faculty in the development of instructional sessions and programs

- To assist in the development of a shared understanding of student competencies and needs

- To aid librarians and faculty in the development of research methods courses at the undergraduate and graduate levels

Because teaching methods, course content, and undergraduate requirements vary by institution, librarians and faculty may apply these guidelines in different ways to meet the needs of their students. For guidelines on helping students develop general research skills, librarians and faculty may refer to the "ACRL Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education" at www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlstandards/informationliteracycompetency.htm .

Introduction

Most research in literary studies begins with the text, whether it is a paperback novel, the electronic text of a poem on an author’s Web site, or an illuminated manuscript in a library’s collection. Educators encourage students to gain a deeper understanding of a text by exploring the context of the writing and the interpretations of others, and by developing and supporting their own interpretations. Limited only by their imaginations, students face almost endless opportunities for interpretation of a text.

Research plays an indispensable role in the textual discovery process for students. Good research skills help the literary explorer learn more about the author and the author’s world, examine scholarly interpretations of the text, and create new studies and interpretations to add to a body of knowledge. Sometimes the goals of textual discovery and interpretation can get lost in the minutiae of database searching and conforming to specific citation styles. However, it is important for librarians and other educators to remember these goals when helping students develop the research skills necessary for literary exploration.

Outcomes for Undergraduate English or American Literature Majors

I. understand the structure of information within the field of literary research:.

I.1 Differentiate between primary and secondary sources

I.1.i. Learn to discover and use primary source materials in print and in digital repositories, e.g., ECCO and EEBO

I.2 Understand that literary scholarship is produced and disseminated in a variety of formats, including monographs, journal articles, conference proceedings, dissertations, reference sources, and Web sites

I.3 Learn the significant features (e.g., series title, volume number, imprint) of different kinds of documents (e.g., journal articles, monographs, essays from edited collections)

I.4 Differentiate between reviews of literary works and literary criticism

I.5 Understand the concept and significance of peer-reviewed sources of information

I.6 Understand that literary texts exist in a variety of editions, some of which are more authoritative or useful than others

I.7 Understand the authorship, production, dissemination, or availability of literary production. This includes understanding the meanings and distinctions of the concepts of editions, facsimiles, and authoritative editions

II. Identify and use key literary research tools to locate relevant information:

II.1 Effectively use library catalogs to identify relevant holdings at local institutions and print and online catalogs and bibliographic tools to identify holdings at other libraries

II.2 Distinguish among the different types of reference works (e.g., catalogs, bibliographies, indexes, concordances, etc.) and understand the kind of information offered by each

II.3 Identify, locate, evaluate, and use reference sources and other appropriate information sources about authors, critics, and theorists

II.4 Use subjective and objective sources such as book reviews, citation indexes, and surveys of research to determine the relative importance of an author and/or the relevance of the specific work

II.5 Use reference and other appropriate information resources to provide background information and contextual information about social, intellectual, and literary culture

II.6 Understand the range of physical and virtual locations and repositories and how to navigate them successfully

II.7 Understand the uses of all available catalogs and services

III. Plan effective search strategies and modify search strategies as needed:

III.1 Identify the best indexes and databases

III.2 Use appropriate commands (such as Boolean operators) for database searches

III.3 Identify broader, narrower, and related terms or concepts when initial searches retrieve few or no results

III.4 Identify and use subject terms from the MLA International Bibliography and other specialized indexes and bibliographies

III.5 Identify and use Library of Congress subject headings for literature and authors

IV. Recognize and make appropriate use of library services in the research process:

IV.1 Identify and use librarians and reference services in the research process

IV.2 Use interlibrary loan and document delivery to acquire materials not available at one's own library

IV.3 Use digital resource service centers to read and create literary and critical documents in a variety of digital forms

V. Understand that some information sources are more authoritative than others and demonstrate critical thinking in the research process:

V.1 Know about Internet resources (e.g., electronic discussion lists, Web sites) and how to evaluate them for relevancy and credibility

V.2 Differentiate between resources provided free on the Internet and subscription electronic resources

V.3 Develop and use appropriate criteria for evaluating print resources

V.4 Learn to use critical bibliographies as a tool in evaluating materials

VI. Understand the technical and ethical issues involved in writing research essays:

VI.1 Document sources ethically

VI.2 Employ the MLA or other appropriate documentation style

VI.3 Understand the relationship between received knowledge and the production of new knowledge in the discipline of literary studies

VI.4 Analyze and ethically incorporate the work of others to create new knowledge

VII. Locate information about the literary profession itself:

VII.1 Access information about graduate programs and specialized programs in film study, creative writing, and other related fields, and about workshops and summer study opportunities

VII.2 Access information about financial assistance and scholarships available for literary study and related fields

VII.3 Access information on careers in literary studies and use of these skills in other professions

VII.4 Access information on professional associations

Altick, Richard D., and John J. Fenstermaker. The Art of Literary Research . 4th ed. New York: Norton, 1993.

Association of College and Research Libraries, American Library Association. "Information Literacy Competency Standards for Higher Education." Chicago, IL: ACRL, 2000. 22 March 2007 www.ala.org/ala/acrl/acrlstandards/informationliteracycompetency.htm

Gibaldi, Joseph. MLA Handbook for Writers of Research Papers . 6th ed. New York: Modern Language Association, 2003.

Grafstein, Ann. "A Discipline-Based Approach to Information Literacy." Journal of Academic Librarianship 28 (2002): 197-204.

Jones, Cheryl, Carla Reichard, and Kouider Mokhtari. "Are Students’ Learning Styles Discipline Specific?" Community College Journal of Research & Practice 27 (2003): 363-375.

Leckie, Gloria J. "Desperately Seeking Citations: Uncovering Faculty Assumptions about the Undergraduate Research Process." Journal of Academic Librarianship 22 (1996): 201-208.

Literary Research: LR. College Park, MD : Literary Research Association , 1986-1990.

Literary Research Newsletter. Brockport, N.Y.: Literary Research Newsletter Association, 1976-1985.

Pastine, Maureen. "Teaching the Art of Literary Research." Conceptual Frameworks for Bibliographic Education: Theory into Practice . Ed. Mary Reichel and Mary Ann Ramey. Littleton, Colo.: Libraries Unlimited, 1987. 134-44.

Reynolds, Judy. "The MLA International Bibliography and Library Instruction in Literature and the Humanities." Literature in English: A Guide for Librarians in the Digital Age . Ed. Betty H. Day and William A. Wortman. Chicago: Association of College and Research Libraries, 2000. 213-247.

Introduction to research skills: Home

- Learning from lectures

- Managing your time

- Effective reading

- Evaluating Information

- Critical thinking

- Presentation skills

- Studying online

- Writing home

- Maths and Statistics Support

- Problem solving

- Maths skills by discipline

- Introduction to research skills

- Primary research

- Research methods

- Managing data

- Research ethics

- Citing and referencing

- Searching the literature

- What is academic integrity?

- Referencing software

- Integrity Officer/Panel

- Intellectual property and copyright

- Digital skills home

Research skills allow you to find information and use it effectively. It includes creating a strategy to gather facts and reach conclusions so that you can answer a question.

Starting your research

think about your topic – don’t be too vague or too specific (try mind mapping or keyword searching).

read broadly around your subject (don’t just use Google and Wikipedia). Think about a research question that is clearly structured and builds on literature already produced.

find information using the subject databases. View the Database Orientation Program to learn about databases and using search strategies to refine your search and limit results. View our library tutorial on planning your literature search and look at our library subject guides for resources on your specific topic.

Another good starting point for finding information is our library catalogue Library Search which allows you to search across the library's electronic resources as well as major subject databases and indexes.

carry out a literature review . You may want to include journals, books, websites, grey literature or data and statistics for example. See the list of sources below for more information. Keep a record and organise your references and sources. If you are intending to carry out a systematic review then take a look at the systematic review page on our Research Support library guide.

evaluate your resources – use the CRAAP test (Currency, Relevancy, Authority, Accuracy, Purpose - watch the video, top right).

reach considered conclusions and make recommendations where necessary.

Your research journey.

Why do I need research skills?

they enable you to locate appropriate information and evaluate it for quality and relevance

they allow you to make good use of information to resolve a problem

they give you the ability to synthesize and communicate your ideas in written and spoken formats

they foster critical thinking

they are highly transferable and can be adapted to many settings including the workplace

You can access more in depth information on areas such as primary research, literature reviews, research methods, and managing data, from the drop down headings under Research Skills on the Academic Skills home page. The related resources in the right-hand column of this page also contain useful supporting information.

- Conference proceedings

- Data & statistics

- Grey literature

- Official publications

Books are good for exploring new subject areas. They help define a topic and provide an in-depth account of a subject.

Scholarly books contain authoritative information including comprehensive accounts of research or scholarship and experts' views on themes and topics. Their bibliographies can lead readers to related books, articles and other sources.

Details on the electronic books held by the University of Southampton can be found using the library catalogue .

Journals are quicker to publish than books and are often a good source of current information. They are useful when you require information to support an argument or original research written by subject experts. The bibliographies at the end of journal articles should point you to other relevant research.

Academic journals go through a "peer-review" process. A peer-reviewed journal is one whose articles are checked by experts, so you can be more confident that the information they contain is reliable.

The Library's discovery service Library Search is a good place to start when searching for journal articles and enables access to anything that is available electronically.

Newspapers enable you to follow current and historical events from multiple perspectives. They are an excellent record of political, social, cultural, and economic events and history.

Newspapers are popular rather than scholarly publications and their content needs to be treated with caution. For example, an account of a particular topic can be biased in favour of that newspaper’s political affiliation or point of view. Always double-check the data/statistics or any other piece of information that a newspaper has used to support an argument before you quote it in your own work.

The library subscribes to various resources which provide full-text access to both current and historical newspapers. Find out more about these on the Library's Newspaper Resources page.

Websites provide information about every topic imaginable, and many will be relevant to your studies.

Use websites with caution as anyone can publish on the Internet and therefore the quality of the information provided is variable. When you’re researching and come across a website you think might be useful, consider whether or not it provides information that is reliable and authoritative enough to use in your work.

Proceedings are collections of papers presented by researchers at academic conferences or symposia. They may be printed volumes or in electronic format.

You can use the information in conference proceedings with a high degree of confidence as the quality is ensured by having external experts read & review the papers before they are accepted in the proceedings.

Find the data and statistics you need, from economics to health, environment to oceanography - and everywhere between - http://library.soton.ac.uk/data .

Grey literature is the term given to non-traditional publications (material not published by mainstream publishers). For example - leaflets, reports, conference proceedings, government documents, preprints, theses, clinical trials, blogs, tweets, etc..

The majority of Grey literature is generally not peer-reviewed so it is very important to critically appraise any grey literature before using it.

Most aspects of life are touched by national governments, or by inter-governmental bodies such as the European Union or the United Nations. Official publications are the documentary evidence of that interest.

Our main printed collections and online services are for British and EU official publications, but we can give advice on accessing official publications from other places and organisations. Find out more from our web pages http://library.soton.ac.uk/officialpublications .

Patents protect inventions - the owner can stop other people making, using or selling the item without their permission. This applies for a limited period and a separate application is needed for each country.

Patents can be useful since they contain full technical details on how an invention works. If you use an active patent outside of research - permission or a license is probably needed.

Related resources:

Checking for CRAAP - UMW New Media Archive

How to Develop a STRONG Research Question - Scribbr

Guide to dissertation and project writing - by University of Southampton (Enabling Services)

Guide to writing your dissertation - by the Royal Literary Fund

Guidance on the Conduct of Narrative Synthesis in Systematic Reviews - by ESRC Methods Programme

Guidelines for preparing a Research Proposal - by University of Southampton

Choosing good keywords - by the Open University

Developing a Research or Guided Question - a self-guided tutorial produced by Arizona State University

Evaluating information - a 7 minute tutorial from the University of Southampton which covers thinking critically, and understanding how to find quality and reliable information.

Hints on conducting a literature review - by the University of Toronto

Planning your literature search - a short tutorial by the University of Southampton

Using Overleaf for scientific writing and publishing - a popular LaTeX/Rich Text based online collaborative tool for students and researchers alike. It is designed to make the process of writing, editing, and producing scientific papers quicker and easier for authors.

Systematic reviews - by the University of Southampton.

Create your own research proposal - by the University of Southampton

- Last Updated: Mar 13, 2024 3:14 PM

- URL: https://library.soton.ac.uk/sash/introduction-to-research-skills

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

What is a literature review?

A literature review is a critical analysis of the literature related to your research topic. It evaluates and critiques the literature to establish a theoretical framework for your research topic and/or identify a gap in the existing research that your research will address.

A literature review is not a summary of the literature. You need to engage deeply and critically with the literature. Your literature review should show your understanding of the literature related to your research topic and lead to presenting a rationale for your research.

A literature review focuses on:

- the context of the topic

- key concepts, ideas, theories and methodologies

- key researchers, texts and seminal works

- major issues and debates

- identifying conflicting evidence

- the main questions that have been asked around the topic

- the organisation of knowledge on the topic

- definitions, particularly those that are contested

- showing how your research will advance scholarly knowledge (generally referred to as identifying the ‘gap’).

This module will guide you through the functions of a literature review; the typical process of conducting a literature review (including searching for literature and taking notes); structuring your literature review within your thesis and organising its internal ideas; and styling the language of your literature review.

The purposes of a literature review

A literature review serves two main purposes:

1) To show awareness of the present state of knowledge in a particular field, including:

- seminal authors

- the main empirical research

- theoretical positions

- controversies

- breakthroughs as well as links to other related areas of knowledge.

2) To provide a foundation for the author’s research. To do that, the literature review needs to:

- help the researcher define a hypothesis or a research question, and how answering the question will contribute to the body of knowledge;

- provide a rationale for investigating the problem and the selected methodology;

- provide a particular theoretical lens, support the argument, or identify gaps.

Before you engage further with this module, try the quiz below to see how much you already know about literature reviews.

Research and Writing Skills for Academic and Graduate Researchers Copyright © 2022 by RMIT University is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- USC Libraries

- Research Guides

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Paper

- 5. The Literature Review

- Purpose of Guide

- Design Flaws to Avoid

- Independent and Dependent Variables

- Glossary of Research Terms

- Reading Research Effectively

- Narrowing a Topic Idea

- Broadening a Topic Idea

- Extending the Timeliness of a Topic Idea

- Academic Writing Style

- Choosing a Title

- Making an Outline

- Paragraph Development

- Research Process Video Series

- Executive Summary

- The C.A.R.S. Model

- Background Information

- The Research Problem/Question

- Theoretical Framework

- Citation Tracking

- Content Alert Services

- Evaluating Sources

- Primary Sources

- Secondary Sources

- Tiertiary Sources

- Scholarly vs. Popular Publications

- Qualitative Methods

- Quantitative Methods

- Insiderness

- Using Non-Textual Elements

- Limitations of the Study

- Common Grammar Mistakes

- Writing Concisely

- Avoiding Plagiarism

- Footnotes or Endnotes?

- Further Readings

- Generative AI and Writing

- USC Libraries Tutorials and Other Guides

- Bibliography

A literature review surveys prior research published in books, scholarly articles, and any other sources relevant to a particular issue, area of research, or theory, and by so doing, provides a description, summary, and critical evaluation of these works in relation to the research problem being investigated. Literature reviews are designed to provide an overview of sources you have used in researching a particular topic and to demonstrate to your readers how your research fits within existing scholarship about the topic.

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . Fourth edition. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2014.

Importance of a Good Literature Review

A literature review may consist of simply a summary of key sources, but in the social sciences, a literature review usually has an organizational pattern and combines both summary and synthesis, often within specific conceptual categories . A summary is a recap of the important information of the source, but a synthesis is a re-organization, or a reshuffling, of that information in a way that informs how you are planning to investigate a research problem. The analytical features of a literature review might:

- Give a new interpretation of old material or combine new with old interpretations,

- Trace the intellectual progression of the field, including major debates,

- Depending on the situation, evaluate the sources and advise the reader on the most pertinent or relevant research, or

- Usually in the conclusion of a literature review, identify where gaps exist in how a problem has been researched to date.

Given this, the purpose of a literature review is to:

- Place each work in the context of its contribution to understanding the research problem being studied.

- Describe the relationship of each work to the others under consideration.

- Identify new ways to interpret prior research.

- Reveal any gaps that exist in the literature.

- Resolve conflicts amongst seemingly contradictory previous studies.

- Identify areas of prior scholarship to prevent duplication of effort.

- Point the way in fulfilling a need for additional research.

- Locate your own research within the context of existing literature [very important].

Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper. 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2011; Knopf, Jeffrey W. "Doing a Literature Review." PS: Political Science and Politics 39 (January 2006): 127-132; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012.

Types of Literature Reviews

It is important to think of knowledge in a given field as consisting of three layers. First, there are the primary studies that researchers conduct and publish. Second are the reviews of those studies that summarize and offer new interpretations built from and often extending beyond the primary studies. Third, there are the perceptions, conclusions, opinion, and interpretations that are shared informally among scholars that become part of the body of epistemological traditions within the field.

In composing a literature review, it is important to note that it is often this third layer of knowledge that is cited as "true" even though it often has only a loose relationship to the primary studies and secondary literature reviews. Given this, while literature reviews are designed to provide an overview and synthesis of pertinent sources you have explored, there are a number of approaches you could adopt depending upon the type of analysis underpinning your study.

Argumentative Review This form examines literature selectively in order to support or refute an argument, deeply embedded assumption, or philosophical problem already established in the literature. The purpose is to develop a body of literature that establishes a contrarian viewpoint. Given the value-laden nature of some social science research [e.g., educational reform; immigration control], argumentative approaches to analyzing the literature can be a legitimate and important form of discourse. However, note that they can also introduce problems of bias when they are used to make summary claims of the sort found in systematic reviews [see below].

Integrative Review Considered a form of research that reviews, critiques, and synthesizes representative literature on a topic in an integrated way such that new frameworks and perspectives on the topic are generated. The body of literature includes all studies that address related or identical hypotheses or research problems. A well-done integrative review meets the same standards as primary research in regard to clarity, rigor, and replication. This is the most common form of review in the social sciences.

Historical Review Few things rest in isolation from historical precedent. Historical literature reviews focus on examining research throughout a period of time, often starting with the first time an issue, concept, theory, phenomena emerged in the literature, then tracing its evolution within the scholarship of a discipline. The purpose is to place research in a historical context to show familiarity with state-of-the-art developments and to identify the likely directions for future research.

Methodological Review A review does not always focus on what someone said [findings], but how they came about saying what they say [method of analysis]. Reviewing methods of analysis provides a framework of understanding at different levels [i.e. those of theory, substantive fields, research approaches, and data collection and analysis techniques], how researchers draw upon a wide variety of knowledge ranging from the conceptual level to practical documents for use in fieldwork in the areas of ontological and epistemological consideration, quantitative and qualitative integration, sampling, interviewing, data collection, and data analysis. This approach helps highlight ethical issues which you should be aware of and consider as you go through your own study.

Systematic Review This form consists of an overview of existing evidence pertinent to a clearly formulated research question, which uses pre-specified and standardized methods to identify and critically appraise relevant research, and to collect, report, and analyze data from the studies that are included in the review. The goal is to deliberately document, critically evaluate, and summarize scientifically all of the research about a clearly defined research problem . Typically it focuses on a very specific empirical question, often posed in a cause-and-effect form, such as "To what extent does A contribute to B?" This type of literature review is primarily applied to examining prior research studies in clinical medicine and allied health fields, but it is increasingly being used in the social sciences.

Theoretical Review The purpose of this form is to examine the corpus of theory that has accumulated in regard to an issue, concept, theory, phenomena. The theoretical literature review helps to establish what theories already exist, the relationships between them, to what degree the existing theories have been investigated, and to develop new hypotheses to be tested. Often this form is used to help establish a lack of appropriate theories or reveal that current theories are inadequate for explaining new or emerging research problems. The unit of analysis can focus on a theoretical concept or a whole theory or framework.

NOTE : Most often the literature review will incorporate some combination of types. For example, a review that examines literature supporting or refuting an argument, assumption, or philosophical problem related to the research problem will also need to include writing supported by sources that establish the history of these arguments in the literature.

Baumeister, Roy F. and Mark R. Leary. "Writing Narrative Literature Reviews." Review of General Psychology 1 (September 1997): 311-320; Mark R. Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Kennedy, Mary M. "Defining a Literature." Educational Researcher 36 (April 2007): 139-147; Petticrew, Mark and Helen Roberts. Systematic Reviews in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide . Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishers, 2006; Torracro, Richard. "Writing Integrative Literature Reviews: Guidelines and Examples." Human Resource Development Review 4 (September 2005): 356-367; Rocco, Tonette S. and Maria S. Plakhotnik. "Literature Reviews, Conceptual Frameworks, and Theoretical Frameworks: Terms, Functions, and Distinctions." Human Ressource Development Review 8 (March 2008): 120-130; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Thinking About Your Literature Review

The structure of a literature review should include the following in support of understanding the research problem :

- An overview of the subject, issue, or theory under consideration, along with the objectives of the literature review,

- Division of works under review into themes or categories [e.g. works that support a particular position, those against, and those offering alternative approaches entirely],

- An explanation of how each work is similar to and how it varies from the others,

- Conclusions as to which pieces are best considered in their argument, are most convincing of their opinions, and make the greatest contribution to the understanding and development of their area of research.

The critical evaluation of each work should consider :

- Provenance -- what are the author's credentials? Are the author's arguments supported by evidence [e.g. primary historical material, case studies, narratives, statistics, recent scientific findings]?

- Methodology -- were the techniques used to identify, gather, and analyze the data appropriate to addressing the research problem? Was the sample size appropriate? Were the results effectively interpreted and reported?

- Objectivity -- is the author's perspective even-handed or prejudicial? Is contrary data considered or is certain pertinent information ignored to prove the author's point?

- Persuasiveness -- which of the author's theses are most convincing or least convincing?

- Validity -- are the author's arguments and conclusions convincing? Does the work ultimately contribute in any significant way to an understanding of the subject?

II. Development of the Literature Review

Four Basic Stages of Writing 1. Problem formulation -- which topic or field is being examined and what are its component issues? 2. Literature search -- finding materials relevant to the subject being explored. 3. Data evaluation -- determining which literature makes a significant contribution to the understanding of the topic. 4. Analysis and interpretation -- discussing the findings and conclusions of pertinent literature.

Consider the following issues before writing the literature review: Clarify If your assignment is not specific about what form your literature review should take, seek clarification from your professor by asking these questions: 1. Roughly how many sources would be appropriate to include? 2. What types of sources should I review (books, journal articles, websites; scholarly versus popular sources)? 3. Should I summarize, synthesize, or critique sources by discussing a common theme or issue? 4. Should I evaluate the sources in any way beyond evaluating how they relate to understanding the research problem? 5. Should I provide subheadings and other background information, such as definitions and/or a history? Find Models Use the exercise of reviewing the literature to examine how authors in your discipline or area of interest have composed their literature review sections. Read them to get a sense of the types of themes you might want to look for in your own research or to identify ways to organize your final review. The bibliography or reference section of sources you've already read, such as required readings in the course syllabus, are also excellent entry points into your own research. Narrow the Topic The narrower your topic, the easier it will be to limit the number of sources you need to read in order to obtain a good survey of relevant resources. Your professor will probably not expect you to read everything that's available about the topic, but you'll make the act of reviewing easier if you first limit scope of the research problem. A good strategy is to begin by searching the USC Libraries Catalog for recent books about the topic and review the table of contents for chapters that focuses on specific issues. You can also review the indexes of books to find references to specific issues that can serve as the focus of your research. For example, a book surveying the history of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict may include a chapter on the role Egypt has played in mediating the conflict, or look in the index for the pages where Egypt is mentioned in the text. Consider Whether Your Sources are Current Some disciplines require that you use information that is as current as possible. This is particularly true in disciplines in medicine and the sciences where research conducted becomes obsolete very quickly as new discoveries are made. However, when writing a review in the social sciences, a survey of the history of the literature may be required. In other words, a complete understanding the research problem requires you to deliberately examine how knowledge and perspectives have changed over time. Sort through other current bibliographies or literature reviews in the field to get a sense of what your discipline expects. You can also use this method to explore what is considered by scholars to be a "hot topic" and what is not.

III. Ways to Organize Your Literature Review

Chronology of Events If your review follows the chronological method, you could write about the materials according to when they were published. This approach should only be followed if a clear path of research building on previous research can be identified and that these trends follow a clear chronological order of development. For example, a literature review that focuses on continuing research about the emergence of German economic power after the fall of the Soviet Union. By Publication Order your sources by publication chronology, then, only if the order demonstrates a more important trend. For instance, you could order a review of literature on environmental studies of brown fields if the progression revealed, for example, a change in the soil collection practices of the researchers who wrote and/or conducted the studies. Thematic [“conceptual categories”] A thematic literature review is the most common approach to summarizing prior research in the social and behavioral sciences. Thematic reviews are organized around a topic or issue, rather than the progression of time, although the progression of time may still be incorporated into a thematic review. For example, a review of the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics could focus on the development of online political satire. While the study focuses on one topic, the Internet’s impact on American presidential politics, it would still be organized chronologically reflecting technological developments in media. The difference in this example between a "chronological" and a "thematic" approach is what is emphasized the most: themes related to the role of the Internet in presidential politics. Note that more authentic thematic reviews tend to break away from chronological order. A review organized in this manner would shift between time periods within each section according to the point being made. Methodological A methodological approach focuses on the methods utilized by the researcher. For the Internet in American presidential politics project, one methodological approach would be to look at cultural differences between the portrayal of American presidents on American, British, and French websites. Or the review might focus on the fundraising impact of the Internet on a particular political party. A methodological scope will influence either the types of documents in the review or the way in which these documents are discussed.

Other Sections of Your Literature Review Once you've decided on the organizational method for your literature review, the sections you need to include in the paper should be easy to figure out because they arise from your organizational strategy. In other words, a chronological review would have subsections for each vital time period; a thematic review would have subtopics based upon factors that relate to the theme or issue. However, sometimes you may need to add additional sections that are necessary for your study, but do not fit in the organizational strategy of the body. What other sections you include in the body is up to you. However, only include what is necessary for the reader to locate your study within the larger scholarship about the research problem.

Here are examples of other sections, usually in the form of a single paragraph, you may need to include depending on the type of review you write:

- Current Situation : Information necessary to understand the current topic or focus of the literature review.

- Sources Used : Describes the methods and resources [e.g., databases] you used to identify the literature you reviewed.

- History : The chronological progression of the field, the research literature, or an idea that is necessary to understand the literature review, if the body of the literature review is not already a chronology.

- Selection Methods : Criteria you used to select (and perhaps exclude) sources in your literature review. For instance, you might explain that your review includes only peer-reviewed [i.e., scholarly] sources.

- Standards : Description of the way in which you present your information.

- Questions for Further Research : What questions about the field has the review sparked? How will you further your research as a result of the review?

IV. Writing Your Literature Review

Once you've settled on how to organize your literature review, you're ready to write each section. When writing your review, keep in mind these issues.

Use Evidence A literature review section is, in this sense, just like any other academic research paper. Your interpretation of the available sources must be backed up with evidence [citations] that demonstrates that what you are saying is valid. Be Selective Select only the most important points in each source to highlight in the review. The type of information you choose to mention should relate directly to the research problem, whether it is thematic, methodological, or chronological. Related items that provide additional information, but that are not key to understanding the research problem, can be included in a list of further readings . Use Quotes Sparingly Some short quotes are appropriate if you want to emphasize a point, or if what an author stated cannot be easily paraphrased. Sometimes you may need to quote certain terminology that was coined by the author, is not common knowledge, or taken directly from the study. Do not use extensive quotes as a substitute for using your own words in reviewing the literature. Summarize and Synthesize Remember to summarize and synthesize your sources within each thematic paragraph as well as throughout the review. Recapitulate important features of a research study, but then synthesize it by rephrasing the study's significance and relating it to your own work and the work of others. Keep Your Own Voice While the literature review presents others' ideas, your voice [the writer's] should remain front and center. For example, weave references to other sources into what you are writing but maintain your own voice by starting and ending the paragraph with your own ideas and wording. Use Caution When Paraphrasing When paraphrasing a source that is not your own, be sure to represent the author's information or opinions accurately and in your own words. Even when paraphrasing an author’s work, you still must provide a citation to that work.

V. Common Mistakes to Avoid

These are the most common mistakes made in reviewing social science research literature.

- Sources in your literature review do not clearly relate to the research problem;

- You do not take sufficient time to define and identify the most relevant sources to use in the literature review related to the research problem;

- Relies exclusively on secondary analytical sources rather than including relevant primary research studies or data;

- Uncritically accepts another researcher's findings and interpretations as valid, rather than examining critically all aspects of the research design and analysis;

- Does not describe the search procedures that were used in identifying the literature to review;

- Reports isolated statistical results rather than synthesizing them in chi-squared or meta-analytic methods; and,

- Only includes research that validates assumptions and does not consider contrary findings and alternative interpretations found in the literature.

Cook, Kathleen E. and Elise Murowchick. “Do Literature Review Skills Transfer from One Course to Another?” Psychology Learning and Teaching 13 (March 2014): 3-11; Fink, Arlene. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper . 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage, 2005; Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1998; Jesson, Jill. Doing Your Literature Review: Traditional and Systematic Techniques . London: SAGE, 2011; Literature Review Handout. Online Writing Center. Liberty University; Literature Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016; Ridley, Diana. The Literature Review: A Step-by-Step Guide for Students . 2nd ed. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2012; Randolph, Justus J. “A Guide to Writing the Dissertation Literature Review." Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation. vol. 14, June 2009; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016; Taylor, Dena. The Literature Review: A Few Tips On Conducting It. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Writing a Literature Review. Academic Skills Centre. University of Canberra.

Writing Tip

Break Out of Your Disciplinary Box!

Thinking interdisciplinarily about a research problem can be a rewarding exercise in applying new ideas, theories, or concepts to an old problem. For example, what might cultural anthropologists say about the continuing conflict in the Middle East? In what ways might geographers view the need for better distribution of social service agencies in large cities than how social workers might study the issue? You don’t want to substitute a thorough review of core research literature in your discipline for studies conducted in other fields of study. However, particularly in the social sciences, thinking about research problems from multiple vectors is a key strategy for finding new solutions to a problem or gaining a new perspective. Consult with a librarian about identifying research databases in other disciplines; almost every field of study has at least one comprehensive database devoted to indexing its research literature.

Frodeman, Robert. The Oxford Handbook of Interdisciplinarity . New York: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Another Writing Tip

Don't Just Review for Content!

While conducting a review of the literature, maximize the time you devote to writing this part of your paper by thinking broadly about what you should be looking for and evaluating. Review not just what scholars are saying, but how are they saying it. Some questions to ask:

- How are they organizing their ideas?

- What methods have they used to study the problem?

- What theories have been used to explain, predict, or understand their research problem?

- What sources have they cited to support their conclusions?

- How have they used non-textual elements [e.g., charts, graphs, figures, etc.] to illustrate key points?

When you begin to write your literature review section, you'll be glad you dug deeper into how the research was designed and constructed because it establishes a means for developing more substantial analysis and interpretation of the research problem.

Hart, Chris. Doing a Literature Review: Releasing the Social Science Research Imagination . Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications, 1 998.

Yet Another Writing Tip

When Do I Know I Can Stop Looking and Move On?

Here are several strategies you can utilize to assess whether you've thoroughly reviewed the literature:

- Look for repeating patterns in the research findings . If the same thing is being said, just by different people, then this likely demonstrates that the research problem has hit a conceptual dead end. At this point consider: Does your study extend current research? Does it forge a new path? Or, does is merely add more of the same thing being said?

- Look at sources the authors cite to in their work . If you begin to see the same researchers cited again and again, then this is often an indication that no new ideas have been generated to address the research problem.

- Search Google Scholar to identify who has subsequently cited leading scholars already identified in your literature review [see next sub-tab]. This is called citation tracking and there are a number of sources that can help you identify who has cited whom, particularly scholars from outside of your discipline. Here again, if the same authors are being cited again and again, this may indicate no new literature has been written on the topic.

Onwuegbuzie, Anthony J. and Rebecca Frels. Seven Steps to a Comprehensive Literature Review: A Multimodal and Cultural Approach . Los Angeles, CA: Sage, 2016; Sutton, Anthea. Systematic Approaches to a Successful Literature Review . Los Angeles, CA: Sage Publications, 2016.

- << Previous: Theoretical Framework

- Next: Citation Tracking >>

- Last Updated: Apr 1, 2024 9:56 AM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide

- Cambridge Libraries

Study Skills

Research skills.

- Searching the literature

- Note making for dissertations

- Research Data Management

- Copyright and licenses

- Publishing in journals

- Publishing academic books

- Depositing your thesis

- Research metrics

- Build your online profile

- Finding support

Researchers interact with information every day. You might be looking for articles, evaluating sources, writing up work for publication or disseminating your work more widely. And of course the literature does not just consist of books or papers, there's also a lot of research data and grey literature that needs to be processed and distributed appropriately.

We're here to help you find your way in this landscape and make the most of your research opportunities. We have designed these online modules that you can take in your own time. Each one is packed with ideas and tips to help you succeed as a researcher at Cambridge.

Click on the titles on the left to access each module.

How did you find our Research Skills modules

We'd love to hear about your experience on this site to keep improving our offer and to compare it with face-to-face training. Please take the feedback survey , it should only take around 2 minutes to complete.

- Next: Searching the literature >>

- Last Updated: Sep 18, 2023 9:07 PM

- URL: https://libguides.cam.ac.uk/research-skills

© Cambridge University Libraries | Accessibility | Privacy policy | Log into LibApps

Academic Success in Online Programs pp 111–124 Cite as

Skills and Strategies for Research and Reading

- Jacqueline S. Stephen ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8949-5895 2

- First Online: 03 April 2024

Part of the book series: Springer Texts in Education ((SPTE))

In addition to study skills and study habits, students need to be able to effectively engage in the process of research and college-level reading. Chapter 8 explains the significance of effective research and reading skills on academic performance. There are many types of research activities that college and university students are expected to actively participate in to complete various course requirements. Similarly, there are many different forms of literature that a student will encounter while engaging in the research process. College and university libraries provide access to a many of resources to support students through the research process. Thus, this chapter introduces students to the different types of research activities they can expect to engage in through their courses, explains the different forms of literature that a student may encounter during the research process, and provides insight into the many resources that libraries often provide to support student research activities and student development of college-level research skills. One of the areas of student development is in reading skills. Hence, Chapter 8 explains the various types of reading materials that a student may encounter in college or university courses, provides information on the styles of reading academic texts, and presents strategies to promote effective research and reading, including best practices for evaluating the relevancy and credibility of information sources.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution .

Bauer-Kealey, M., & Mather, N. (2019). Use of an online reading intervention to enhance the basic reading skills of community college students. Community College Journal of Research and Practice, 43 (9), 631–647.

Article Google Scholar

Catts, H. W. (2022). Rethinking how to promote reading comprehension. American Educator, 45 (4), 26.

Google Scholar

Cornoldi, C., & Oakhill, J. V. (Eds.). (2013). Reading comprehension difficulties: Processes and intervention . Routledge.

Huddleston, B. S., Bond, J. D., Chenoweth, L. L., & Hull, T. L. (2019). Faculty perspectives on undergraduate research skills. Reference and User Services Quarterly, 59 (2), 118–130.

Locher, F., & Pfost, M. (2020). The relation between time spent reading and reading comprehension throughout the life course. Journal of Research in Reading, 43 (1), 57–77.

Long, D. L., & Freed, E. M. (2021). An individual differences examination of the relation between reading processes and comprehension. Scientific Studies of Reading, 25 (2), 104–122.

McLean, S., Stewart, J., & Batty, A. O. (2020). Predicting L2 reading proficiency with modalities of vocabulary knowledge: A bootstrapping approach. Language Testing, 37 (3), 389–411.

Ozturk, N. (2022). A pedagogy of metacognition for reading classrooms. International Journal of Education and Literacy Studies, 10 (1), 162–172.