Intellectual Property Law Research Paper Topics

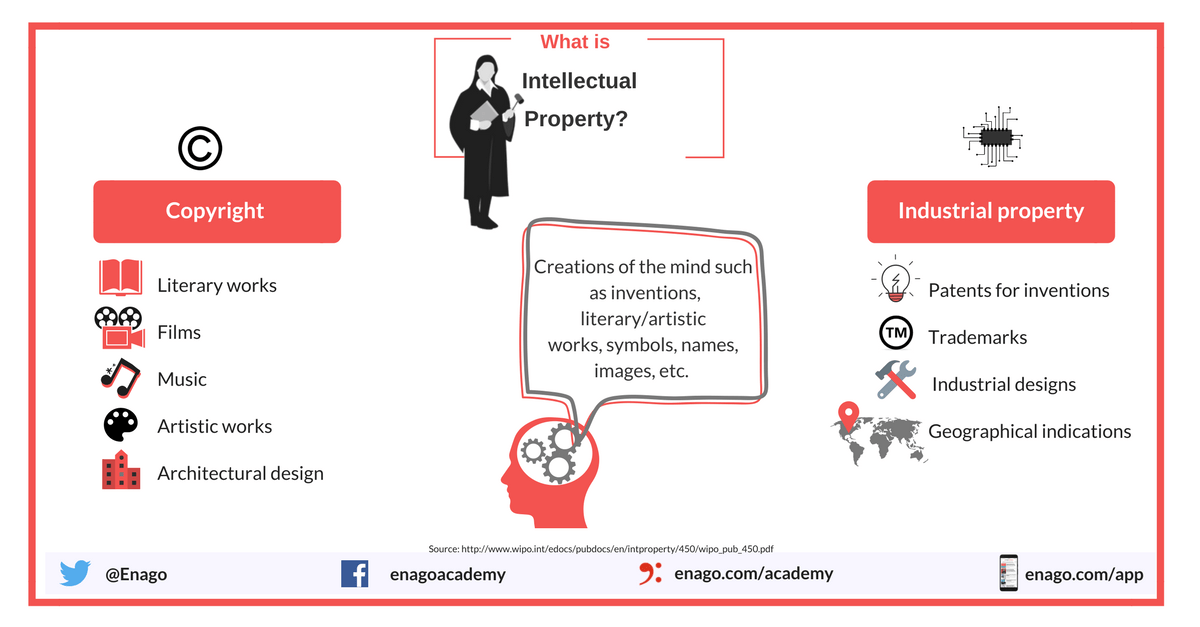

Welcome to the realm of intellectual property law research paper topics , where we aim to guide law students on their academic journey by providing a comprehensive list of 10 captivating and relevant topics in each of the 10 categories. In this section, we will explore the dynamic field of intellectual property law, encompassing copyrights, trademarks, patents, and more, and shed light on its significance, complexities, and the diverse array of research paper topics it offers. With expert tips on topic selection, guidance on crafting an impactful research paper, and access to iResearchNet’s custom writing services, students can empower their pursuit of excellence in the domain of intellectual property law.

100 Intellectual Property Law Research Paper Topics

Intellectual property law is a dynamic and multifaceted field that intersects with various sectors, including technology, arts, business, and innovation. Research papers in this domain allow students to explore the intricate legal framework that governs the creation, protection, and enforcement of intellectual property rights. To aid aspiring legal scholars in their academic pursuits, this section presents a comprehensive list of intellectual property law research paper topics, categorized to encompass a wide range of subjects.

Academic Writing, Editing, Proofreading, And Problem Solving Services

Get 10% off with 24start discount code.

- Fair Use Doctrine: Balancing Creativity and Access to Knowledge

- Copyright Infringement in the Digital Age: Challenges and Solutions

- The Role of Copyright Law in Protecting Creative Works of Art

- The Intersection of Copyright and AI: Legal Implications and Challenges

- Copyright and Digital Education: Analyzing the Impact of Distance Learning

- Copyright and Social Media: Addressing Infringement and User Rights

- Copyright Exceptions for Libraries and Educational Institutions

- Copyright Law and Virtual Reality: Emerging Legal Issues

- Copyright and Artificial Intelligence in Music Creation

- Copyright Termination Rights and Authors’ Works Reversion

- Patentable Subject Matter: Examining the Boundaries of Patent Protection

- Patent Trolls and Innovation: Evaluating the Impact on Technological Advancement

- Biotechnology Patents: Ethical Considerations and Policy Implications

- Patent Wars in the Pharmaceutical Industry: Balancing Access to Medicine and Innovation

- Standard Essential Patents: Analyzing the Role in Technology Development and Market Competition

- Patent Thickets and the Challenges for Startups and Small Businesses

- Patent Pooling and Collaborative Innovation: Advantages and Legal Considerations

- Patent Litigation and Forum Shopping: Analysis of Jurisdictional Issues

- Patent Law and Artificial Intelligence: Implications for Inventorship and Ownership

- Patent Exhaustion and International Trade: Legal Complexities in Global Markets

- Trademark Dilution: Protecting the Distinctiveness of Brands in a Global Market

- Trademark Infringement and the Online Environment: Challenges and Legal Remedies

- The Intersection of Trademark Law and Freedom of Speech: Striking a Balance

- Non-Traditional Trademarks: Legal Issues Surrounding Sound, Color, and Shape Marks

- Trademark Licensing: Key Considerations for Brand Owners and Licensees

- Trademark Protection for Geographical Indications: Preserving Cultural Heritage

- Trademark Opposition and Cancellation Proceedings: Strategies and Legal Considerations

- Trademark Law and Counterfeiting: Global Enforcement Challenges

- Trademark and Domain Name Disputes: UDRP and Legal Strategies

- Trademark Law and Social Media Influencers: Disclosure and Endorsement Guidelines

- Trade Secrets vs. Patents: Choosing the Right Intellectual Property Protection

- Trade Secret Misappropriation: Legal Protections and Remedies for Businesses

- Protecting Trade Secrets in the Digital Age: Cybersecurity Challenges and Best Practices

- International Trade Secret Protection: Harmonization and Enforcement Challenges

- Whistleblowing and Trade Secrets: Balancing Public Interest and Corporate Secrets

- Trade Secret Licensing and Technology Transfer: Legal and Business Considerations

- Trade Secret Protection in Employment Contracts: Non-Compete and Non-Disclosure Agreements

- Trade Secret Misappropriation in Supply Chains: Legal Implications and Risk Mitigation

- Trade Secret Law and Artificial Intelligence: Ownership and Trade Secret Protection

- Trade Secret Protection in the Era of Open Innovation and Collaborative Research

- Artificial Intelligence and Intellectual Property: Ownership and Liability Issues

- 3D Printing and Intellectual Property: Navigating the Intersection of Innovation and Copyright

- Blockchain Technology and Intellectual Property: Challenges and Opportunities

- Digital Rights Management: Addressing Copyright Protection in the Digital Era

- Open Source Software Licensing: Legal Implications and Considerations

- Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality: Legal Issues in Content Creation and Distribution

- Internet of Things (IoT) and Intellectual Property: Legal Challenges and Policy Considerations

- Big Data and Intellectual Property: Privacy and Data Protection Concerns

- Artificial Intelligence and Patent Offices: Automation and Efficiency Implications

- Intellectual Property Implications of 5G Technology: Connectivity and Innovation Challenges

- Music Copyright and Streaming Services: Analyzing Legal Challenges and Solutions

- Fair Use in Documentary Films: Balancing Copyright Protection and Freedom of Expression

- Intellectual Property in Video Games: Legal Issues in the Gaming Industry

- Digital Piracy and Copyright Enforcement: Approaches to Tackling Online Infringement

- Personality Rights in Media: Balancing Privacy and Freedom of the Press

- Streaming Services and Copyright Licensing: Legal Challenges and Royalty Distribution

- Fair Use in Parody and Satire: Analyzing the Boundaries of Creative Expression

- Copyright Protection for User-Generated Content: Balancing Authorship and Ownership

- Media Censorship and Intellectual Property: Implications for Freedom of Information

- Virtual Influencers and Copyright: Legal Challenges in the Age of AI-Generated Content

- Intellectual Property Protection in Developing Countries: Promoting Innovation and Access to Knowledge

- Cross-Border Intellectual Property Litigation: Jurisdictional Challenges and Solutions

- Trade Agreements and Intellectual Property: Impact on Global Innovation and Access to Medicines

- Harmonization of Intellectual Property Laws: Prospects and Challenges for International Cooperation

- Indigenous Knowledge and Intellectual Property: Addressing Cultural Appropriation and Protection

- Intellectual Property and Global Public Health: Balancing Innovation and Access to Medicines

- Geographical Indications in International Trade: Legal Framework and Market Exclusivity

- International Licensing and Technology Transfer: Legal Considerations for Multinational Corporations

- Intellectual Property Enforcement in the Digital Marketplace: Comparative Analysis of International Laws

- Digital Copyright and Cross-Border E-Commerce: Legal Implications for Online Businesses

- Intellectual Property Strategy for Startups: Maximizing Value and Mitigating Risk

- Licensing and Franchising: Legal Considerations for Expanding Intellectual Property Rights

- Intellectual Property Due Diligence in Mergers and Acquisitions: Key Legal Considerations

- Non-Disclosure Agreements: Safeguarding Trade Secrets and Confidential Information

- Intellectual Property Dispute Resolution: Arbitration and Mediation as Alternative Methods

- Intellectual Property Valuation: Methods and Challenges for Business and Investment Decisions

- Technology Licensing and Transfer Pricing: Tax Implications for Multinational Corporations

- Intellectual Property Audits: Evaluating and Managing IP Assets for Businesses

- Trade Secret Protection and Non-Compete Clauses: Balancing Employer and Employee Interests

- Intellectual Property and Startups: Strategies for Funding and Investor Relations

- Intellectual Property and Access to Medicines: Ethical Dilemmas in Global Health

- Gene Patenting and Human Dignity: Analyzing the Moral and Legal Implications

- Intellectual Property and Indigenous Peoples: Recognizing Traditional Knowledge and Culture

- Bioethics and Biotechnology Patents: Navigating the Intersection of Science and Ethics

- Copyright, Creativity, and Freedom of Expression: Ethical Considerations in the Digital Age

- Intellectual Property and Artificial Intelligence: Ethical Implications for AI Development and Use

- Genetic Engineering and Intellectual Property: Legal and Ethical Implications

- Intellectual Property and Environmental Sustainability: Legal and Ethical Perspectives

- Cultural Heritage and Intellectual Property Rights: Preservation and Repatriation Efforts

- Intellectual Property and Social Justice: Access and Equality in the Innovation Ecosystem

- Innovation Incentives and Intellectual Property: Examining the Relationship

- Intellectual Property and Technology Transfer: Promoting Innovation and Knowledge Transfer

- Intellectual Property Rights in Research Collaborations: Balancing Interests and Collaborative Innovation

- Innovation Policy and Patent Law: Impact on Technology and Economic Growth

- Intellectual Property and Open Innovation: Collaborative Models and Legal Implications

- Intellectual Property and Startups: Fostering Innovation and Entrepreneurship

- Intellectual Property and University Technology Transfer: Challenges and Opportunities

- Open Access and Intellectual Property: Balancing Public Goods and Commercial Interests

- Intellectual Property and Creative Industries: Promoting Cultural and Economic Development

- Intellectual Property and Sustainable Development Goals: Aligning Innovation with Global Priorities

The intellectual property law research paper topics presented here are intended to inspire students and researchers to delve into the complexities of intellectual property law and explore emerging issues in this ever-evolving field. Each topic offers a unique opportunity to engage with legal principles, societal implications, and practical challenges. As the landscape of intellectual property law continues to evolve, there remains an exciting realm of uncharted research areas, waiting to be explored. Through in-depth research and critical analysis, students can contribute to the advancement of intellectual property law and its impact on innovation, creativity, and society at large.

Exploring the Range of Topics in Human Rights Law

Human rights law is a vital field of study that delves into the protection and promotion of fundamental rights and freedoms for all individuals. As a cornerstone of international law, human rights law addresses various issues, ranging from civil and political rights to economic, social, and cultural rights. It aims to safeguard the inherent dignity and worth of every human being, regardless of their race, religion, gender, nationality, or other characteristics. In this section, we will explore the diverse and expansive landscape of intellectual property law research paper topics, shedding light on its significance and the vast array of areas where students can conduct meaningful research.

- Historical Perspectives on Human Rights : Understanding the historical evolution of human rights is essential to comprehend the principles and norms that underpin modern international human rights law. Research papers in this category may explore the origins of human rights, the impact of significant historical events on the development of human rights norms, and the role of key figures and organizations in shaping the human rights framework.

- Human Rights and Social Justice : This category delves into the intersection of human rights law and social justice. Intellectual property law research paper topics may encompass the role of human rights in addressing issues of poverty, inequality, discrimination, and marginalization. Researchers can analyze how human rights mechanisms and legal instruments contribute to advancing social justice and promoting inclusivity within societies.

- Gender Equality and Women’s Rights : Gender equality and women’s rights remain crucial subjects in human rights law. Research papers in this area may explore the legal protections for women’s rights, the challenges in achieving gender equality, and the impact of cultural and societal norms on women’s human rights. Intellectual property law research paper topics may also address specific issues such as violence against women, gender-based discrimination, and the role of women in peacebuilding and conflict resolution.

- Freedom of Expression and Media Rights : The right to freedom of expression is a fundamental human right that forms the basis of democratic societies. In this category, researchers can examine the legal dimensions of freedom of expression, including its limitations, the role of media in promoting human rights, and the challenges in balancing freedom of expression with other rights and interests.

- Human Rights in Armed Conflicts and Peacebuilding : Armed conflicts have severe implications for human rights, necessitating robust legal frameworks for protection. Topics in this category may focus on humanitarian law, the rights of civilians during armed conflicts, and the role of international organizations in peacebuilding and post-conflict reconstruction.

- Refugee and Migration Rights : With the global refugee crisis and migration challenges, this category addresses the legal protections and challenges faced by refugees and migrants. Research papers may delve into the rights of asylum seekers, the principle of non-refoulement, and the legal obligations of states in providing humanitarian assistance and protection to displaced populations.

- Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights : Economic, social, and cultural rights are integral to human rights law, ensuring the well-being and dignity of individuals. Topics may explore the right to education, health, housing, and adequate standards of living. Researchers may also examine the justiciability and enforcement of these rights at national and international levels.

- Human Rights and Technology : The digital age presents new challenges and opportunities for human rights. Research in this category can explore the impact of technology on privacy rights, freedom of expression, and the right to access information. Intellectual property law research paper topics may also cover the use of artificial intelligence and algorithms in decision-making processes and their potential implications for human rights.

- Environmental Justice and Human Rights : Environmental degradation has significant human rights implications. Researchers can investigate the intersection of environmental protection and human rights, examining the right to a healthy environment, the rights of indigenous communities, and the role of human rights law in addressing climate change.

- Business and Human Rights : The responsibilities of corporations in upholding human rights have gained increasing attention. This category focuses on corporate social responsibility, human rights due diligence, and legal mechanisms to hold businesses accountable for human rights violations.

The realm of human rights law offers an expansive and dynamic platform for research and exploration. As the international community continues to grapple with pressing human rights issues, students have a unique opportunity to contribute to the discourse and advance human rights protections worldwide. Whether examining historical perspectives, social justice, gender equality, freedom of expression, or other critical areas, research in human rights law is a compelling endeavor that can make a positive impact on the lives of people globally.

How to Choose an Intellectual Property Law Topic

Choosing the right intellectual property law research paper topic is a crucial step in the academic journey of law students. Intellectual property law is a multifaceted and rapidly evolving field that covers a wide range of subjects, including patents, copyrights, trademarks, trade secrets, and more. With such diversity, selecting a compelling and relevant research topic can be both challenging and exciting. In this section, we will explore ten practical tips to help students navigate the process of choosing an engaging and impactful intellectual property law research paper topic.

- Identify Your Interests and Passion : The first step in selecting a research paper topic in intellectual property law is to identify your personal interests and passion within the field. Consider what aspects of intellectual property law resonate with you the most. Are you fascinated by the intricacies of patent law and its role in promoting innovation? Or perhaps you have a keen interest in copyright law and its influence on creative expression? By choosing a topic that aligns with your passions, you are more likely to stay motivated and engaged throughout the research process.

- Stay Updated on Current Developments : Intellectual property law is a dynamic area with continuous developments and emerging trends. To choose a relevant and timely research topic, it is essential to stay updated on recent court decisions, legislative changes, and emerging issues in the field. Follow reputable legal news sources, academic journals, and intellectual property law blogs to remain informed about the latest developments.

- Narrow Down the Scope : Given the vastness of intellectual property law, it is essential to narrow down the scope of your research paper topic. Focus on a specific subfield or issue within intellectual property law that interests you the most. For example, you may choose to explore the legal challenges of protecting digital copyrights in the music industry or the ethical implications of gene patenting in biotechnology.

- Conduct Preliminary Research : Before finalizing your research paper topic, conduct preliminary research to gain a better understanding of the existing literature and debates surrounding the chosen subject. This will help you assess the availability of research material and identify any gaps or areas for further exploration.

- Review Case Law and Legal Precedents : In intellectual property law, case law plays a crucial role in shaping legal principles and interpretations. Analyzing landmark court decisions and legal precedents in your chosen area can provide valuable insights and serve as a foundation for your research paper.

- Consult with Professors and Experts : Seek guidance from your professors or intellectual property law experts regarding potential intellectual property law research paper topics. They can offer valuable insights, suggest relevant readings, and provide feedback on the feasibility and relevance of your chosen topic.

- Consider Practical Applications : Intellectual property law has real-world implications and applications. Consider choosing a research topic that has practical significance and addresses real challenges faced by individuals, businesses, or society at large. For example, you might explore the role of intellectual property in facilitating technology transfer in developing countries or the impact of intellectual property rights on access to medicines.

- Analyze International Perspectives : Intellectual property law is not confined to national boundaries; it has significant international dimensions. Analyzing the differences and similarities in intellectual property regimes across different countries can offer a comparative perspective and enrich your research paper.

- Propose Solutions to Existing Problems : A compelling research paper in intellectual property law can propose innovative solutions to existing problems or challenges in the field. Consider focusing on an area where there are unresolved debates or conflicting interests and offer well-reasoned solutions based on legal analysis and policy considerations.

- Seek Feedback and Refine Your Topic : Once you have narrowed down your research paper topic, seek feedback from peers, professors, or mentors. Be open to refining your topic based on constructive criticism and suggestions. A well-defined and thoughtfully chosen research topic will set the stage for a successful and impactful research paper.

Choosing the right intellectual property law research paper topic requires careful consideration, passion, and a keen awareness of current developments in the field. By identifying your interests, staying updated on legal developments, narrowing down the scope, conducting preliminary research, and seeking guidance from experts, you can select a compelling and relevant topic that contributes to the academic discourse in intellectual property law. A well-chosen research topic will not only showcase your expertise and analytical skills but also provide valuable insights into the complexities and challenges of intellectual property law in the modern world.

How to Write an Intellectual Property Law Research Paper

Writing an intellectual property law research paper can be an intellectually stimulating and rewarding experience. However, it can also be a daunting task, especially for students who are new to the intricacies of legal research and academic writing. In this section, we will provide a comprehensive guide on how to write an effective and impactful intellectual property law research paper. From understanding the structure and components of the paper to conducting thorough research and crafting compelling arguments, these ten tips will help you navigate the writing process with confidence and proficiency.

- Understand the Paper Requirements : Before diving into the writing process, carefully review the requirements and guidelines provided by your professor or institution. Pay attention to the paper’s length, formatting style (APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, Harvard, etc.), citation guidelines, and any specific instructions regarding the research paper topic or research methods.

- Conduct In-Depth Research : A strong intellectual property law research paper is built on a foundation of comprehensive and credible research. Utilize academic databases, legal journals, books, and reputable online sources to gather relevant literature and legal precedents related to your chosen topic. Ensure that your research covers a wide range of perspectives and presents a well-rounded analysis of the subject matter.

- Develop a Clear Thesis Statement : The thesis statement is the central argument of your research paper. It should be concise, specific, and clearly convey the main point you will be arguing throughout the paper. Your thesis statement should reflect the significance of your research topic and its contribution to the field of intellectual property law.

- Create an Outline : An outline is a roadmap for your research paper, helping you organize your thoughts and ideas in a logical and coherent manner. Divide your paper into sections, each representing a key aspect of your argument. Within each section, outline the main points you will address and the evidence or analysis that supports your claims.

- Introduction : Engage and Provide Context: The introduction of your research paper should captivate the reader’s attention and provide essential context for your study. Start with a compelling opening sentence or anecdote that highlights the importance of the topic. Clearly state your thesis statement and provide an overview of the main points you will explore in the paper.

- Literature Review : In the early sections of your research paper, include a literature review that summarizes the existing research and scholarship on your topic. Analyze the key theories, legal doctrines, and debates surrounding the subject matter. Use this section to demonstrate your understanding of the existing literature and to identify gaps or areas where your research will contribute.

- Legal Analysis and Argumentation : The heart of your intellectual property law research paper lies in your legal analysis and argumentation. Each section of the paper should present a well-structured and coherent argument supported by legal reasoning, case law, and relevant statutes. Clearly explain the legal principles and doctrines you are applying and provide evidence to support your conclusions.

- Consider Policy Implications : Intellectual property law often involves complex policy considerations. As you present your legal arguments, consider the broader policy implications of your research findings. Discuss how your proposed solutions or interpretations align with societal interests and contribute to the advancement of intellectual property law.

- Anticipate Counterarguments : To strengthen your research paper, anticipate potential counterarguments to your thesis and address them thoughtfully. Acknowledging and refuting counterarguments demonstrate the depth of your analysis and the validity of your position.

- Conclusion : Recapitulate and Reflect: In the conclusion of your research paper, recapitulate your main arguments and restate your thesis statement. Reflect on the insights gained from your research and highlight the significance of your findings. Avoid introducing new information in the conclusion and instead, offer recommendations for further research or policy implications.

Writing an intellectual property law research paper requires meticulous research, careful analysis, and persuasive argumentation. By following the tips provided in this section, you can confidently navigate the writing process and create an impactful research paper that contributes to the field of intellectual property law. Remember to adhere to academic integrity and proper citation practices throughout your research, and seek feedback from peers or professors to enhance the quality and rigor of your work. A well-crafted research paper will not only demonstrate your expertise in the field but also provide valuable insights into the complexities and nuances of intellectual property law.

iResearchNet’s Research Paper Writing Services

At iResearchNet, we understand the challenges that students face when tasked with writing complex and comprehensive research papers on intellectual property law topics. We recognize the importance of producing high-quality academic work that meets the rigorous standards of legal research and analysis. To support students in their academic endeavors, we offer custom intellectual property law research paper writing services tailored to meet individual needs and requirements. Our team of expert writers, well-versed in the intricacies of intellectual property law, is committed to delivering top-notch, original, and meticulously researched papers that can elevate your academic performance.

- Expert Degree-Holding Writers : Our team consists of experienced writers with advanced degrees in law and expertise in intellectual property law. They possess the necessary knowledge and research skills to create well-crafted research papers that showcase a profound understanding of the subject matter.

- Custom Written Works : We take pride in producing custom-written research papers that are unique to each client. When you place an order with iResearchNet, you can be assured that your paper will be tailored to your specific instructions and requirements.

- In-Depth Research : Our writers conduct thorough and comprehensive research to ensure that your intellectual property law research paper is well-supported by relevant legal sources and up-to-date literature.

- Custom Formatting : Our writers are well-versed in various citation styles, including APA, MLA, Chicago/Turabian, and Harvard. We will format your research paper according to your specified citation style, ensuring accuracy and consistency throughout the paper.

- Top Quality : We are committed to delivering research papers of the highest quality. Our team of editors reviews each paper to ensure that it meets the required academic standards and adheres to your instructions.

- Customized Solutions : At iResearchNet, we recognize that each research paper is unique and requires a tailored approach. Our writers take the time to understand your specific research objectives and create a paper that aligns with your academic goals.

- Flexible Pricing : We offer competitive and flexible pricing options to accommodate students with varying budget constraints. Our pricing is transparent, and there are no hidden fees or additional charges.

- Short Deadlines : We understand that students may face tight deadlines. Our writers are skilled in working efficiently without compromising the quality of the research paper. We offer short turnaround times, including deadlines as tight as 3 hours.

- Timely Delivery : Punctuality is a priority at iResearchNet. We ensure that your completed research paper is delivered to you on time, allowing you ample time for review and any necessary revisions.

- 24/7 Support : Our customer support team is available 24/7 to assist you with any queries or concerns you may have. Feel free to contact us at any time, and we will promptly address your needs.

- Absolute Privacy : We value your privacy and confidentiality. Your personal information and order details are treated with the utmost confidentiality, and we never share your data with third parties.

- Easy Order Tracking : Our user-friendly platform allows you to easily track the progress of your research paper. You can communicate directly with your assigned writer and stay updated on the status of your order.

- Money-Back Guarantee : We are committed to customer satisfaction. If, for any reason, you are not satisfied with the quality of the research paper, we offer a money-back guarantee.

When it comes to writing an exceptional intellectual property law research paper, iResearchNet is your reliable partner. With our team of expert writers, commitment to quality, and customer-centric approach, we are dedicated to helping you succeed in your academic pursuits. Whether you need assistance with choosing a research paper topic, conducting in-depth research, or crafting a compelling argument, our custom writing services are designed to provide you with the support and expertise you need. Place your order with iResearchNet today and unlock the full potential of your intellectual property law research.

Unlock Your Full Potential with iResearchNet

Are you ready to take your intellectual property law research to new heights? Look no further than iResearchNet for comprehensive and professional support in crafting your research papers. Our custom writing services are tailored to cater to your unique academic needs, ensuring that you achieve academic excellence and stand out in your studies. Let us be your trusted partner in the journey of intellectual exploration and legal research.

Take the first step toward unleashing the full potential of your intellectual property law research. Place your order with iResearchNet and experience the difference of working with a professional and reliable custom writing service. Our team of dedicated writers and exceptional customer support are here to support you every step of the way. Don’t let the challenges of intellectual property law research hold you back; empower yourself with the assistance of iResearchNet and set yourself up for academic success.

ORDER HIGH QUALITY CUSTOM PAPER

- Browse All Articles

- Newsletter Sign-Up

IntellectualProperty →

No results found in working knowledge.

- Were any results found in one of the other content buckets on the left?

- Try removing some search filters.

- Use different search filters.

- How it works

Useful Links

How much will your dissertation cost?

Have an expert academic write your dissertation paper!

Dissertation Services

Get unlimited topic ideas and a dissertation plan for just £45.00

Order topics and plan

Get 1 free topic in your area of study with aim and justification

Yes I want the free topic

Intellectual Property Law Dissertation Topics

Published by Ellie Cross at December 29th, 2022 , Revised On August 15, 2023

A dissertation or a thesis in the study area of intellectual property rights can be a tough nut to crack for students. Masters and PhD students of intellectual property rights often struggle to come up with a relevant and fulfilling research topic; this is where they should seek academic assistance from experts.

An individual, a group, an association, an organisation or a company that wants to claim ownership of a particular design, piece of art, piece of technology, piece of literature, or physical or virtual property must adhere to a specific set of rules. Without these regulations, known as intellectual property rights, concerning parties will not be secure, and anyone could easily steal from them. If someone else attempts to take the property, the original owners are guaranteed the right to keep and reclaim it.

So let’s take a look at the below list of unique and focused intellectual property law dissertation topics, so you can select one more suitable to your requirements and get started with your project without further delay. Don’t forget to read our free guide on writing a dissertation step by step after you have finalised the topic.

A List Of Intellectual Property Law Dissertation Topics Is Provided Below

- How can virtual companies ensure that copyright rules are followed while creating their logos, websites, goods, and designs?

- What does it mean legally to own an original work of art or piece of property?

- Can the most recent technical developments coexist peacefully with the present patent rules and system?

- Does the UK’s intellectual property legislation protect the owners and users fairly and securely?

- Is there a connection between European and British intellectual property laws?

- Comparison of the institutions and regulations governing intellectual property in the US and the UK

- What do fair pricing and fair dealing with copyright regulations mean?

- Can a business or individual assert ownership of a colour scheme or hue?

- The conflict between business law and trade secrets

- The Difficult Relationship Between Intellectual Property and Contemporary Art

- Trade-Related Aspects of IP Rights: A Workable Instrument for Enforcing Benefit Sharing

- A US-UK Comparison of the Harmonization of UK Copyright and Trademark Damages

- The difficulties brought by digitalisation and the internet are beyond the capacity of the copyright system to appropriately address them. Discuss

- Which copyright laws can be cited as protecting software?

- The law on online copyright infringement facilitation

- The necessity for companies to safeguard their brand value should serve as the primary

- Justification for trademark protection. The general welfare is only a secondary concern. Discuss

- Intellectual property rights are being directly used by businesses and investors: IP privateering and contemporary letters of marque and reprisal

- Decisions and dynamics in understanding the role of intellectual property in digital technology-based startups

- Investigating conflicts between appropriable and collaborative openness in innovation

- Assessing the strength and scope of our system for protecting the intellectual property rights of indigenous people

- Assessing legal protections for intellectual property rights online

- Does EU copyright legislation adequately balance the requirements of consumers and inventors?

- A case study of the US is used to evaluate fair dealing in terms of copyright law.

- Contrasting and comparing the US and UK intellectual property systems

- Are consumers and owners protected and treated fairly under EU intellectual property law?

- What effects has EU legislation had on the UK’s intellectual property system?

- What more should be done to increase the efficacy of the US’s present intellectual property laws?

- Analyzing how Brexit may affect the UK’s protection of intellectual property rights

- An in-depth analysis of the UK’s invention and patenting system: Can the existing, rigid system stimulate innovation?

Order a Proposal

Worried about your dissertation proposal? Not sure where to start?

- Choose any deadline

- Plagiarism free

- Unlimited free amendments

- Free anti-plagiarism report

- Completed to match exact requirements

When choosing a topic in intellectual property law, make sure your selection is based on your interests.

As an intellectual property rights law student, there are many areas you might base your thesis or dissertation on. For example, a copyright lawyer can defend the rights of creative works; a patent lawyer can provide lawful protection for inventors; and a trademark lawyer can assist with the protection of trademarks. There are also rights related to plant varieties, trade dresses, and industrial designs that you could investigate.

Dissertations take a lot of time and effort to complete. It is essential to seek writing assistance if you are struggling to complete the paper on time to ensure you don’t end up failing the module.

ResearchProspect is an affordable dissertation writing service with a team of expert writers who have years of experience in writing dissertations and are familiar with the ideal format. P lace your order now !

Free Dissertation Topic

Phone Number

Academic Level Select Academic Level Undergraduate Graduate PHD

Academic Subject

Area of Research

Frequently Asked Questions

How to find intellectual property law dissertation topics.

To find Intellectual Property Law dissertation topics:

- Study recent IP developments.

- Examine emerging technologies.

- Analyze legal debates and cases.

- Explore global IP issues.

- Consider economic implications.

- Select a topic aligning with your passion and career goals.

You May Also Like

There are a wide range of topics in sports management that can be researched at the national and international levels. International sports are extremely popular worldwide, making sports management research issues very prominent as well.

Even though event management seems easy, it is actually quite complex once you study it. If you study event management with an instructor who is committed to teaching you with integrity, it can be manageable.

For any company and organisation, one of the most important yet sensitive assets is its information. Therefore, it is essential to keep the data secured from getting stolen and avoid getting it used for malicious activities.

USEFUL LINKS

LEARNING RESOURCES

COMPANY DETAILS

- How It Works

- Search Menu

- Advance articles

- Author Guidelines

- Submission Site

- Open Access Options

- About Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice

- Editorial Board

- Advertising and Corporate Services

- Journals Career Network

- Self-Archiving Policy

- Dispatch Dates

- Journals on Oxford Academic

- Books on Oxford Academic

Eleonora Rosati

Stefano Barazza

Marius Schneider

Managing Editor

Sarah Harris

About the journal

JIPLP is a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to intellectual property law and practice.

Why Publish with JIPLP ?

The Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice publishes a full range of IP topics and practice-related, offering the opportunity to maximise the impact of your research with a global audience, Open Access publishing and more. Find out more about the benefits of publishing with our journal.

Find out more .

Case Law Round-Ups

An updated collection on the latest round-ups published in the Journal of Intellectual Property Law and Practice on important topics.

Explore the full collection

DSM Special Issue Webinar

Watch a free webinar on the new DSM Special Issue, featuring the issue's authors and discussions of the Directive's most important provisions.

Watch now

The JIPLP Blog is where editorial panellists, readers and contributors all come together to share their view on all aspects of IP law and practice.

Explore the JIPLP Blog

Latest articles

Latest posts on x, jiplp on the oupblog, much ado about nothing the us supreme court’s warhol opinion.

“Is there any future guidance in the opinion about other fair use disputes? Yes, but not in the majority opinion.” William Patry’s latest blog post discusses future guidance for fair use disputes from the Andy Warhol Foundation v. Goldsmith US Supreme Court case.

View the blog post

Not only food and drinks: how EU (and UK) law could also protect handicrafts

On the EU and UK's GI Quality schemes and what classes of products are protected, from Andrea Zappalaglio.

The traps of social media: to 'like' or not to 'like'

“A recent Swiss case reported in the media has raised the spectre of criminal liability and/or defamation for merely ‘liking’ a 3rd party post on Facebook.”

Explore Gill Grassie's blog post here.

Rihanna, the Court of Appeal, and a Topshop t-shirt

“Can a fashion retailer take a photograph of a celebrity, print it on a t-shirt and sell it without the celebrity’s approval? Yes, but sometimes no.”

Read the rest of the post from Darren Meale here.

Related Titles

- About Journal of Intellectual Property Law & Practice

- JIPLP Weblog

- Recommend to your Library

Affiliations

- Online ISSN 1747-1540

- Print ISSN 1747-1532

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- About Oxford Academic

- Publish journals with us

- University press partners

- What we publish

- New features

- Open access

- Institutional account management

- Rights and permissions

- Get help with access

- Accessibility

- Advertising

- Media enquiries

- Oxford University Press

- Oxford Languages

- University of Oxford

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University's objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide

- Copyright © 2024 Oxford University Press

- Cookie settings

- Cookie policy

- Privacy policy

- Legal notice

This Feature Is Available To Subscribers Only

Sign In or Create an Account

This PDF is available to Subscribers Only

For full access to this pdf, sign in to an existing account, or purchase an annual subscription.

Innovations in intellectual property rights management: Their potential benefits and limitations

European Journal of Management and Business Economics

ISSN : 2444-8494

Article publication date: 9 April 2019

Issue publication date: 16 July 2019

The purpose of this paper is to evaluate innovations in intellectual property rights (IPR) databases, techniques and software tools, with an emphasis on selected new developments and their contribution towards achieving advantages for IPR management (IPRM) and wider social benefits. Several industry buzzwords are addressed, such as IPR-linked open data (IPR LOD) databases, blockchain and IPR-related techniques, acknowledged for their contribution in moving towards artificial intelligence (AI) in IPRM.

Design/methodology/approach

The evaluation, following an original framework developed by the authors, is based on a literature review, web analysis and interviews carried out with some of the top experts from IPR-savvy multinational companies.

The paper presents the patent databases landscape, classifying patent offices according to the format of data provided and depicting the state-of-art in the IPR LOD. An examination of existing IPR tools shows that they are not yet fully developed, with limited usability for IPRM. After reviewing the techniques, it is clear that the current state-of-the-art is insufficient to fully address AI in IPR. Uses of blockchain in IPR show that they are yet to be fully exploited on a larger scale.

Originality/value

A critical analysis of IPR tools, techniques and blockchain allows for the state-of-art to be assessed, and for their current and potential value with regard to the development of the economy and wider society to be considered. The paper also provides a novel classification of patent offices and an original IPR-linked open data landscape.

- Artificial intelligence

- Software tools

- Social benefits

- Intellectual property rights management

- Linked open databases

Modic, D. , Hafner, A. , Damij, N. and Cehovin Zajc, L. (2019), "Innovations in intellectual property rights management: Their potential benefits and limitations", European Journal of Management and Business Economics , Vol. 28 No. 2, pp. 189-203. https://doi.org/10.1108/EJMBE-12-2018-0139

Emerald Publishing Limited

Copyright © 2019, Dolores Modic, Ana Hafner, Nadja Damij and Luka Cehovin Zajc

Published in European Journal of Management and Business Economics . Published by Emerald Publishing Limited. This article is published under the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) licence. Anyone may reproduce, distribute, translate and create derivative works of this article (for both commercial and non-commercial purposes), subject to full attribution to the original publication and authors. The full terms of this licence may be seen at http://creativecommons.org/licences/by/4.0/legalcode

1. Introduction

The world today seems to be characterised by the effects of information and communication technology (ICT) on every aspect of our lives, including that of intellectual property rights (IPR) ( Modic, 2017 ). Freeman and Louca (2002 , p. 301) wrote that “even those who have disputed the revolutionary character of earlier waves of technological change, have little difficulty accepting that a vast technological revolution is now taking place”. The surge of intellectual property is mirrored in rising IPR numbers with dissemination efforts dependent upon the available data, channels and skills. IPR data are big data, as its characteristics are high volume, high variety and high velocity of changes ( Ciccatelli, 2017 ). Consequently, merging different types of IPR data from various databases presents a challenge ( Stading, 2017 ; Abbas et al. , 2014 ).

When huge amounts of IPR data are connected, a new ecosystem for (open) innovation emerges. It is important to examine the best available IPR data sources, and their merge-readiness, in order to extract the maximum value. Furthermore, it is important to ensure the availability of appropriate IPR techniques and tools if we are to harness the benefits for IPR management (IPRM) and the wider social benefits of this new open IPR landscape and move towards knowledge creation assisted by artificial intelligence (AI). Examining the latest trends in technological solutions and their potential is the foci of our paper.

Figure 1 presents two dimensions: the benefits and the technology. Looking at the technology dimension, all three layers represent issues companies face. IPR software tools and techniques should better respond to business requirements, and as such support changes in databases when dealing with IPR big data, such as the implementation of blockchain technology and linked open databases.

The benefits dimension is also facing several gaps. One refers to the identification of the accessibility of employees’ knowledge both in SMEs and IPR-savvy companies. In addition, there are inefficiencies when trying to transform tacit to explicit knowledge in order to further knowledge creation.

Both the technology and benefits dimensions are linked, as the technology aims to, largely unsuccessfully at the present time, to support the requirements of the IPRM, thus increasing the IPRM-derived benefits. These would consequently be translated, especially through the use of blockchain technology and IPR-linked open data (IPR LOD) databases, into increased social benefits. The question as to when, and if, the technology will become smart enough to create IPR software tools and techniques that will function in an intelligent manner remains open to debate, as we are faced with increasing transparency and inherently imbued trust.

If AI systems provide the best possible answer to every IPR-related business requirement, in order to maximise business potential, does this mean that the employees’ knowledge creation will become obsolete and AI systems will be able to effectively create new knowledge?

The paper offers a review and an interview-based analysis of the requirements and expectations of some of the top IPR experts from IPR-savvy multinationals, as well as a consideration of the potential social benefits. This is followed by a web-based analysis and data retrieval-based evaluation of the current evolution of IPR (LOD) databases. Furthermore, the practical solutions available have been critically evaluated with respect to IPR databases and IPR software tools. The results of the analysis of the state-of-the-art with the available techniques are presented. Finally, a debate-style conclusion is presented.

2. Background and prepositions

This paper investigates IPRM and IPR social benefits by answering what are the potential social and IPRM benefits of adopting new ICT solutions when dealing with IPR, and especially what is the current state of all three technological layers? The research is based on the following prepositions constructed following the literature review and the evidence-based approach.

The IPR-linked open data (IPR LOD) map is still in its infancy, thus the full potential of their social benefits are still not realized.

AI is a term used very broadly when connected to IPR techniques, to oversell various information retrieval (IR) and machine learning (ML) methods.

The tools do not correspond to the needs of users as expressed by top IPR managers.

Blockchain has the potential to produce both IPRM and IPR-connected social benefits if some issues are solved.

The outputs of this paper are the classifications of IPR databases and patent offices according to Berners-Lee Open Data Plan, and IPR LOD map as connected to patents as well as classification of tools and techniques. A mixed methods approach has been used, every part diligently designed with methodological notes.

3. Methodology

We derive our analysis of potential benefits of new solutions for IPR and the potential of IPR tools from interviews with ten prominent IP experts. First, interviews with ten prominent IP experts were conducted. Seven out of the ten IP experts were head IP managers within their respective companies. The companies selected are positioned highly in terms of patent applications and quality rankings. Furthermore, they appear on top innovation listings, such as MIT’s list of the 50 Smartest companies. All respondents are executives with years of experience; and one of the interviewees appeared twice in the 50 most influential people in IP, as listed by the Managing Intellectual Property magazine. Views expressed inside the interviews are their own and not the views of the companies they are affiliated with. Interviews were conducted either in person, via Skype or via similar VoIP during 2016 and with follow-ups in 2017. Transcripts were analysed using MAXQDA Analytics Pro 12 software. Interview questions were divided into three sections: IPRM (1), formalization (2) and optimisation of processes and gaps reduction (3)). In particular for this paper three topics and their related questions that were included in this semi-structured interview questionnaire are harnessed upon (pertaining to either part (1) or part (3): What is the missing information and/or resources?; Which software tools do you use inside your processes? What are their pros and cons?; What kind of (big) data analysis would be particularly interesting? Who can provide them?

The technologies section brings further methods. The classification of patent offices was done in the period January–February 2018 by conducting web searches and experimental searches with consequent search retrievals inside patent search machines either for full patent documents or at least bibliographical exports. The classification encompasses primarily EU Patent Offices as well as a selection of other relevant patent offices [1] . The framework for the patent map relies on The Linking Open Data cloud diagram, however, it has been significantly upgraded by including material gathered via web searches guided by discussions with various patent offices’ staff members. Analysis of techniques is based on critical literature review. We also reviewed websites of 11 top IPR tools providers as identified by interviewees and/or the Hyperion MarketView™ Report (2016) and Capterra’s review (2017 ). Analysis is based on reviews of websites (November, 2017) by Anaqua for Corporations, IP One (from CPA Global), InnovationQ (from ip.com), IPfolio, PatentSight, Unycom Enterprise, Wellspring’s IP management software, Patricia (form Patrix), Alt Legal, Inteum, Dennemeyer’s DIAMS iQ [2] .

4. The potential social and IPRM benefits of new advances in the field of IPR

One of the biggest problems of IPR data usability is the rapid growth of number of IPR, especially patents. They are written in different languages and it has become increasingly challenging to understand the state of the art, this consequently causing duplication of research and increasing the number of invalid patents granted. Once errors can be corrected, it will be easier to identify inherently invalid patents previously granted, and consequently leading to a natural rise in the quality of IPR.

Governments have a large quantity of IPR-related data, which can be of economic and social value to society. European Patent Office (EPO) sees the advantages of its new LOD patent databases, one of the outlets of the new open data trend, as increased availability of data from different sources via one channel, less “data friction” when combining different data sets, more effective linking with business information and increased trust thanks to provenance ( Kracker, 2017 ). The Korean Patent Office (KIPO) also saw its efforts in a similar manner ( KIPO, 2016 ).

The growing importance of IPR Open (linked) data is connected to better transparency making it easier for companies to understand their value. However, if we could not only have exploitable open databases, but if these could also be combined with IPR techniques with AI functionality, and additionally, IPR tools which supported the handling of IPR data by integrating some AI functionalities, we could be seeing a new form of tacit knowledge, the “Artificial intelligence knowledge” creation (see Figure 1 ). Therefore, the often problematic issue of tacit knowledge inside the IPR field embodied in individuals (note that the usual way of gaining IPRM, exploitation and other connected IPR knowledge is through apprenticeship and that the rotation of individuals presents a serious problem for especially company IPR departments, Modic and Damij, 2018 )) would be transformed into a latent explicit knowledge (knowledge available on recall as opposed to explicit knowledge, always available). Solutions, like IBM Watson, seem to also be a game changer in this area. Watson identified compounds on which the patent protection has already lapsed, and the pilot results suggest that Watson can accelerate identification of novel drug candidates and novel drug targets by harnessing the potential of patent (and connected) big data ( Chen et al. , 2016 ). The IBM team believes the insights provided by Watson technology are to be used as a guide, i.e., as augmented intelligence – which is capable of ingesting, digesting, understanding and analysing data and can be harnessed in various elements of IPR processes: from evidence of use, to prior art, patent landscapes and portfolio analysis ( Fleischman, 2018 ). If the technology was widely available with all its features, this could present a significant change, as it would enable smaller entities to access knowledge that is now tacit knowledge.

When discussing traceability, blockchain is one of the frequently debated issues. Several potential social benefits, as derived from the utilisation of blockchain in the field of IPR, are present. A tool for registration of IPRs could simplify registration and lower the costs ( Vella et al. , 2018 ; Morabito, 2017 ) or could be an alternative to IPR registration, especially patents. Thus, it has a potential particularly for small entities (independent inventors, SMEs, non-profit organisations), as well as inventors and organisations from less developed countries, who are unable to access the current world patent system simply because it is too expensive for them.

Blockchain provides a robust and trustworthy method of establishing business ownership on intangible assets, including IPR ( Morabito, 2017 ) and thus has the potential to enhance transparency of IPR transactions ( Vella et al. , 2018 ). Not only does this have positive effects for individual companies, but it can also streamline the costs of operations for patent offices, and reduced options for litigation can lower court case numbers and reduce court backlogs. Furthermore, it also has the potential to enable half open licensing, when royalties start only when IPR-based income is generated by downstream users; meaning that without income generation, the half open licenses allow for IPR-based solutions to be spread in an open environment. Moreover, it would allow tracking commons’ knowledge (under open licenses or not) incorporation into corporate IPR portfolios disallowing the privatisation of gains.

With regard to potential IPRM benefits, IPRM deals with managing IPR big data efficiently, and differently ( Braganza et al. , 2017 ; Davenport et al. , 2012 ). McAfee and Brynjolfsson (2012) argue that companies will not reap the full benefits of the transition made in exploiting big data, unless they are able to manage change effectively.

Analysis of the interviews showed a clear trend that IP executives are aware of the growing importance of ICT, and their role in IPRM, however, they continue to struggle with defining how to integrate IPR tools to achieve best outcome. A Senior IP Counsel at a German multinational chemical manufacturing corporation stated that, “IT developments will have a big impact in the near future on IP development, because the more transparent you make the IP, the easier it is for management to understand its value”.

Utilising the ICT in IPR processes is possible, however, doing it in the most efficient way to enable companies to achieve maximum benefits, is the ideal. Some companies use a range of different software tools connected to IPR and IPRM, whilst others try to find or develop software that integrates as many features and data sources as possible and are able to connect to other business processes and databases. Generally, the more comprehensive the tool, the less information is missing, and consequently, the higher the satisfaction level. Nonetheless, some experts, such as the Head of Legal Operations and IP Management at a European multinational pharmaceutical corporation, believe that IPR tools often promise more than they deliver. He states that they, “do not think there are any particularly good IP management tools on the market /…/the whole industry still lacks are real IP management tools, helping to relate to the business value more”. IPR experts are seeking a tool that would, in addition to being a comprehensive docketing system and simple interface retrieval of data from public IPR databases, also encompass supplying or channelling invention disclosures to pertinent individuals, providing functionality for IPR valuation, evaluation and analysis.

The next chapter will provide more detail deal with regard to the technological dimension, providing an analysis on the current state of linked open databases, software tools for IPRM and techniques that support IPR data correction and analytics.

5. Technology

5.1 databases and linked (open) data.

Since the Venetian patent statute of 1474, IPR have retained their connection to the concept of openness and dissemination of ideas in exchange for limited time monopolies. There are various types of databases and online sources connected with IPR constituting Layer 1 in the framework in Table I . Public patent databases as the original sources allow raw data retrieval and the use of interfaces by providing patent texts and some metadata. Related IPR databases include, for example, those related to patent disputes, patent citations. Business databases provide information on IPR owners, etc. Scientific databases provide us inter alia with data on inventors. Miscellaneous online data sources include less or more structured sources, e.g., business news, blogs-based IPR-related texts, information on IPR experts. Multi-source IPR databases provide broader information, e.g., on IPR quality and business connected data. Two examples of the latter are the data set linking the EPO and USPTO patent data to Amadeus business database and the Oxford Firm-Level IP Database ( Thoma and Torrisi, 2007 ; Helmers et al. , 2011 ).

Linked open data (IPR LOD) databases are the latest evolution in IPR databases, although the concept of LOD goes back to 2006, when principles such as using uniform resource identifiers as names for things and including links were put forward ( Berners-Lee, 2006 ). Linked data are data published on the web in a machine-readable format, which can be linked to or from external data ( Bizer et al. , 2009 ). LOD is in essence a format allowing for efficient (multi-source) database utilisation as the term refers to a set of practices for publishing and interlinking structured data ( Auer, 2014 ).

Combining this to ideas of open data, we get LOD, structured data made available for others to be reused ( Mezaour et al. , 2014 ). The concept is connected to the Open Data movement to ensure public government data are accessible in non-proprietary formats ( Bauer and Kaltenböck, 2012 ). However, LOD landscape includes databases provided by non-governmental entities. DBPedia, extracting structured knowledge from Wikipedia, is often seen as the “nucleus” of LOD ( Auer et al. , 2007 ). Furthermore, patent data of individual patent offices are sometimes provided by outside providers, such as in the case of USPTO or (formally) the EPO.

Table I shows the classification of patent offices and their data according to the Berners-Lee Five Star Open Data Plan. More stars indicate data formats more conducive to open data policies, as they allow for easier export and import of data, and more streamlined merging and analysis. The category **** is redundant as there is no standalone RDF providing databases; and, we would suggest an introduction of the *****+ category, where the additional criteria is the existence of linkages with other data, signalling the real uptake of the raw data by users (see Table I ). The Type indicates the most Open data friendly format, though patent offices often provide other formats simultaneously. They often also provide more than one database, and the degree of the export varies for bibliographical data (Swiss Patent Database offering up to 25 variables).

Five patent offices are leading in terms of IPR LOD; USPTO, EPO, KIPO, IPAustralia and IPO UK. Cooperation of national offices with Espacenet was also advantageous, as it produced the option of a limited bibliographic data download in .csv format (not taken into account above). However, most of the patent offices can still be categorised only as Type * or Type **, their data remaining in linkable open data unfriendly formats.

There are only a few databases that could be categorised as *****+, or that have shown other initiatives to make exporting, merging and analysing data easier. For example, KIPO has not only published the IPR LOD, but also included the owners’ corporate registration number and the Australian Patent Office IPR database includes information about companies’ size, technology and geographic location, making it easier for users to link data on patents to information on related business entities ( KIPO, 2016 ; Man, 2014 ).

Currently, EPO’s Linked open data is the newest of the few IPR LOD databases at users’ disposal. It builds upon their previous work in connecting patent-related data, such as their Deep Linking service, allowing users to consult the EP document’s legal status data. However, the IPR LOD database remains as a raw data product and without additional skills and resources cannot be fully utilised, which could potentially widen the gap between SMEs and IPR-savvy companies. For example, the linkage to DBPedia has also been carried out, but since then de-installed ( Kracker, 2017 ). This year the EPO also included in their Research grant call explicitly the field of linked open data and solutions therein, where at least one project will start end of this year linking EPO database with the Springer database ( IP LodB, 2018 ). The current LOD IPR landscape shown below is based on the The Linking Open Data cloud diagram and upgraded [3] .

Figure 2 shows patent LOD databases [4] we could call *****+, and their inbound and outbound links, as per The Linking Open Data cloud diagram ( LOD cloud, 2018 ) – a complex LOD ecosystem currently listing 1,164 data sets. They are also linked to the most inbound and outbound link-rich LOD databases, namely, the Comprehensive KAN and DBPedia. The new EP LOD and KIPO databases have no data on linkages, even though some attempts were made as mentioned above. There are, however, several LOD databases that this patent data could be linked to; e.g. the recently published bibliographic LOD database by Springer Nature SciGraph or the older New York Times LOD.

When considering the traceability of IPR data, some patent offices offer centralised solutions, such as i-DEPOT, which allows to trace the date of inventions’ creation. However, at the forefront of these debates is blockchain as a disruptive technology, due to its transparency, decentralisation and prevention of infringements and fraud. Blockchain is a chain of blocks of chronologically linked information, replicated in a distributed database. Information can be added, but never removed, changes are registered and validated. Individual blocks can be protected by cryptography, and only those authorised can access the information ( McPhee and Ljutic, 2017 ). Blockchain application to IPR can be either inside the registration or exploitation phases (related to issues of licensing, proving authenticity and piracy) ( Vella et al. , 2018 ; Morabito, 2017 ) as well as distribution. In case of licensing, the topic is connected to smart contracts, open licenses and IPR-based collaboration ( Pilkington, 2016 ; Morabito, 2017 ). Smart contracts are computer codes that reside in the blockchain and are implemented if certain conditions are met, which is confirmable by a number of computers to ensure truthfulness ( Morabito, 2017 ; Szabo, 1997 ). There are numerous potential applications of blockchain connected to IPR. Also, the Linked Data paradigm is evolving from an academic concept for addressing one of the biggest challenges in the area of information management the exploitation of the web as a platform for data and information integration; to practical applications in IPR field deriving from the transfer from the Web of Documents to a Web of Data. Yet, it is clear there is still much to be done, both in terms of the volume of IPR LOD-connected databases, as well as their functionality in linking to other LOD data sets as well as the real-life uptake of blockchain solutions.

5.2 Classification of tools and techniques

This chapter summarises the techniques and tools (technology Layers 2 and 3 as set out in Figure 1 ) that analyse large quantities of patent documents and other IPR data to provide useful information to various users.

The EPO’s database, Espacenet, on its own, currently contains over 100m patent documents from 90 patent authorities worldwide. Whilst patent data are exceptionally important, it is also very difficult to extract some useful information from it as patents are mostly stored as images; written in different languages; countries have different patent requirements; no uniform structural requirements; some patent figures are drawn by hand, some on computer; some patent attorneys intentionally use misleading language; incomprehensible language and grammatical mistakes can be also used inadvertently. How to deal with these issues remains a challenge.

There are several possible taxonomies of IPR software. Considering their functionalities we see tools supporting different phases of the innovation cycle, those supporting financial management (record and estimate costs), archiving documents (IPR portfolio) and enabling communication between users and IPR offices. Some tools have functionality to integrate data from external databases, such as patent litigation information and patent citation indexes. In terms of intended user-base we have IPR tools for companies, for IPR experts and for technology transfer offices.

There is an upward trend in the creation of new IPRM software in recent years. However, after reviewing the websites of the 13 most important IPR tools providers by Hyperion MarketView™ Report (2016) it appears that these tools only modestly respond to the challenges raised, and largely look like any project management software. Bonino et al. (2010) was optimistic with regard to semantic-based solutions, however, some of the tools he describes are currently in poor condition or unavailable.

In terms of techniques utilised in semantic analysis, Abbas et al. (2014) made a taxonomy of proposed computer-assisted patent analysis techniques where they distinguish between text mining and visualisation approaches. These two categories are based on frequent use-cases, whilst the underlying methods are primarily inspired by IR and ML. This is not unreasonable, as patent documents are similar to other types of documents in that they contain textual and visual data as well as references to other documents.

As seen in Figure 3 , a typical IR system consists of document pre-processing, feature extraction and feature analysis. Each of those steps can be based on heuristic rules or utilise machine learning methods. In the following paragraphs, we review the use of different techniques in the IPR research domain in the last decade, with a particular focus on the works referenced in recent literature reviews by Abbas et al. (2014) and Aristodemou and Tietze (2017) . The list is by no means complete, it is only focussed on key examples illustrating the diversity and potential of such methods.

The patent document pre-processing step involves scanning the unstructured data (text and images) and extracting useful information from it.

Due to the nature of the patent data, the approaches mainly focus around text mining techniques; meaning using some kind of natural language processing ( Wang et al. , 2015 ; Han et al. , 2017 ), such as subject–action–object analysis ( Park, Kim, Choi and Yoon, 2013 ; Park, Ree and Kim, 2013 ), property–function analysis ( Dewulf, 2013 ) or rule-based analysis to extract semantic primitives. Several authors have also proposed the utilisation of patent images and sketches in patent analysis, in order to determine similarities between patents ( Bhatti and Handbury, 2013 ). In terms of pre-processing, image analysis challenges involve localisation of images and sub-images, categorisation of images and label recognition ( Vrochidis et al. , 2010 ). The primary sources of inter-information are cross-patent citations ( Altuntas et al. , 2015 ).

The feature extraction methods transform low-level semantic primitives into a document-wide representation. By involving projection of each document into a high-dimensional feature space we can determine bounds between classes or proximity of documents. When processing textual data, the semantic primitives can be frequency vectors ( Chen and Yu-Ting, 2011 ), vectors of concepts that describe higher-level semantic information, or domain-specific hierarchical structures ( Lee, 2013 ). In analysis of patent sketches, content is frequently encoded with shape or texture descriptors ( Bhatti and Handbury, 2013 ) due to the line-art nature of visual information.

The method used in the feature analysis stage depends on the problem at hand, for example, retrieval of similar patents. In this case, IR techniques based on vector distances ( Lee, 2013 ) are used to infer which documents are most similar. Another task is automatic classification of patents using ML methods. Scenarios include patent quality analysis ( Wu et al. , 2016 ), patent categorisation ( Vrochidis et al. , 2010 ) and determining the impact of patents on other aspect of companies ( Chen et al. , 2013 ). Supervised learning methods, such as support vector machines ( Wu et al. , 2016 ) or artificial neural networks ( Chen et al. , 2013 ), are frequently used in such cases. In explorative analysis of the patent landscape for trend identification, people have also utilised unsupervised learning methods, like clustering ( Atzmüller and Landl, 2009 ; Madani and Weber, 2016 ) and network analysis ( Dotsika, 2017 ; Park, Kim, Choi and Yoon, 2013 ).

Despite the apparent contribution of IR methods in transforming access to information, they are harder to apply to semantic-sensitive fields, such as IPR analysis, with the same level of success. The crucial information in patent documents can be difficult to extract automatically because of objective (history, language) or subjective (intentional misuse of description) reasons. As noted by Lupu (2017) , the level of research interest in this field has, after more than a decade of increasing optimism, decreased in the past years. This can be in part attributed to the realisation that extracting high-level semantic content from sophisticated unstructured text and images is very a challenging problem. The most successful working cognitive computing system is IBM Watson, who has already been analysing patent information in the past, with a particular emphasis in the pharmaceutical sector. However, this system is proprietary and accessible only to a limited number of influential clients.

6. Discussion

Over the last years, activities around IPR Open Data, merging of IPR data with related data, IPR Linked Data, IPR-linked open databases and the debates over utilising the Semantic Web opportunities have gained momentum. However, this should go hand in hand with organisations (both public and private) publishing structured data (complying also with linked data standards/principles), the advances in new techniques, as well as IPR tools and their increased availability. Companies and other patent and IPR data users need to draw on those advanced technologies and tools in order to combine, query (and analyse) data as part of their business intelligence, as well as to improve their services and products.

In terms of the availability of data, the amount of IPR and IPR-connected data publically available is increasing. Responding to P1 , the new trends towards formats supporting more export-ready, merge-ready and analysis-ready data are also real, although the amount of patent data available (e.g. as LOD) is still relatively low. LOD means the data are “linkable”, not that it is already linked. This means that the uptake of these databases by the users can be slow and can even widen the gap between the IPR-savvy multinationals with sufficient resources and other smaller entities and individuals. The latter would defeat the purpose of publishing such databases, if the objective was to make IPR data more useful to more groups of users, especially also non-patent savvy users (data scientists, web developers, companies integrating IP into their products). Some steps are taken towards this, for example, IPNOVA (available at the moment as a beta version) which is the interface to the IPAustralia’s IPGOD database. Another route (contrasting somewhat with developing interfaces) is through sufficient dissemination and training workshop accompanying the releases of databases in new formats. On the other hand, the authors remain hopeful as new entities – including private and NGO entities – provide more and more LOD databases, and with growth of potential links, allowing greater potential for IPR.