Essay on Gender Bias

Students are often asked to write an essay on Gender Bias in their schools and colleges. And if you’re also looking for the same, we have created 100-word, 250-word, and 500-word essays on the topic.

Let’s take a look…

100 Words Essay on Gender Bias

Understanding gender bias.

Gender bias refers to the unequal treatment of people based on their gender. It can be seen in various areas like workplaces, schools, or homes. It is a significant issue that needs to be addressed.

Effects of Gender Bias

Gender bias can lead to discrimination and limit opportunities. It can affect a person’s self-esteem and potential. It can also perpetuate stereotypes, leading to unfair expectations.

Combating Gender Bias

To combat gender bias, we need to promote equality and fairness. Education about gender bias is crucial, as well as encouraging respect for all genders.

250 Words Essay on Gender Bias

Introduction.

Gender bias, a deeply entrenched social evil, permeates every layer of society. It is a prejudiced view or preferential treatment based on one’s gender, often favoring men over women. This essay explores the origins, manifestations, and implications of gender bias.

Origins of Gender Bias

Gender bias has roots in patriarchal societies where males were the primary authority figures. This bias is not merely a cultural artifact; it is often subtly propagated through language, education, and media, reinforcing stereotypical gender roles.

Manifestations of Gender Bias

Gender bias manifests in various forms, such as wage disparity, limited opportunities for women in leadership, and societal expectations about gender roles. In STEM fields, for example, women are often underrepresented, a phenomenon attributed to deep-seated biases.

Implications of Gender Bias

The implications of gender bias are far-reaching. It not only restricts individual growth but also hampers societal progress. By limiting opportunities based on gender, we lose out on the potential contributions of half the population.

To redress gender bias, we must challenge and change our societal norms and personal prejudices. Education plays a crucial role in this transformation, promoting gender equality and empowering everyone to contribute their skills and talents without bias. In the end, overcoming gender bias is not just about fairness; it’s about unlocking the full potential of human society.

500 Words Essay on Gender Bias

Gender bias is a deeply rooted issue in societies worldwide, manifesting in various forms, from subtle to blatant. It refers to the unequal treatment or perceptions of individuals based on their gender and often stems from traditional stereotypes and societal norms. This essay delves into the complexities of gender bias, its implications, and potential solutions.

Gender bias is often a product of cultural conditioning and institutionalized stereotypes. It can be explicit, such as discriminatory laws, or implicit, manifesting as unconscious bias. Gender bias is not restricted to any one gender; it affects all genders, leading to a skewed perception of abilities and roles.

The implications of gender bias are far-reaching and pervasive, affecting various aspects of life. In the workplace, it can lead to unequal pay or opportunities, contributing to the gender wage gap. In education, it can limit access to resources or opportunities for certain genders, shaping career paths and future prospects. It also influences societal expectations, dictating ‘appropriate’ behaviors and roles for different genders.

Gender Bias in Media and Popular Culture

Media and popular culture play a significant role in perpetuating gender bias. The portrayal of genders in movies, advertisements, and literature often reinforces stereotypes, shaping public perception. For instance, the underrepresentation of women in leadership roles in films may lead to the belief that women are less capable leaders.

Addressing Gender Bias

Addressing gender bias requires a multifaceted approach. Education is a powerful tool in this regard. By promoting gender equality and challenging stereotypes in educational settings, we can foster more equitable attitudes.

Moreover, policies should be implemented to ensure equal opportunities and fair treatment for all genders in workplaces, schools, and other institutions. For instance, implementing transparent salary structures can help address the gender wage gap.

Lastly, individuals can play a significant role in challenging gender bias. By becoming aware of our own biases and actively seeking to challenge them, we can contribute to a more equitable society.

Gender bias is a complex issue deeply ingrained in societal structures and attitudes. It impacts various aspects of life, from career opportunities to societal expectations. Addressing it requires a concerted effort from individuals, institutions, and society at large. Through education, policy changes, and personal commitment, we can challenge and overcome gender bias, paving the way for a more equitable society.

That’s it! I hope the essay helped you.

If you’re looking for more, here are essays on other interesting topics:

- Essay on Gender Stereotypes

- Essay on Gender Equality in India

- Essay on Gender Equality

Apart from these, you can look at all the essays by clicking here .

Happy studying!

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Blog Justice Digital

https://mojdigital.blog.gov.uk/2024/03/08/breaking-gender-stereotypes-a-personal-reflection/

Breaking Gender Stereotypes: A Personal Reflection

This International Women’s Day, I wanted to reflect on the power of role models to increase inclusion and inspire change in the workplace.

When he was five, my son asked me if men were ever allowed to be doctors. His question came from the world he knew - he had only ever seen or heard about women doctors. His aunt is a doctor, his granny a senior nurse, and of course Miss Rabbit in his favourite show, Peppa Pig, is a doctor, among her many other and varied professions.

I grew up in a family where traditional gender roles were ignored. My mum was the main earner whilst my dad stayed at home to look after the kids. It never once occurred to me that being a woman would limit my potential or my dreams. My mum was a daily role model of a strong, inspiring woman with a series of very senior jobs. She showed resilience, capability, and confidence. I saw first-hand that a woman could be a mum and have the career she wanted at the same time.

What I didn’t see at the time of course were the barriers that she and her generation, as well as the women before her, were forced to overcome to get to that position. Or indeed how difficult it was to succeed in a still very male-dominated environment. Gender discrimination, limited job opportunities, unequal pay, and pervasive sexual harassment were harsh realities for women in the 1980s and 1990s.

Thankfully, pioneering women persisted in their pursuit of equality and paved the way for future generations like mine to challenge traditional gender roles and advocate for workplace fairness and a seat at the table. I stand on the shoulders of these giants - the courageous women like my mum who defied societal norms, shattered glass ceilings, and fought tirelessly for gender equality. Their unwavering determination and resilience has paved the way for me and countless others to succeed without the constraints of gender stereotypes.

But despite my young son thinking that only women can be doctors, the battle isn’t yet won.

Gender equality is not just a female fight

It’s up to everyone as a collective to drive progress. Today, in 2024, despite advancements in gender equality, women continue to face obstacles such as the gender pay gap, under-representation in leadership roles, and workplace harassment.

The McKinsey’s 2002 report on Women in the Workplace showed that when managers actively advocate for gender diversity and provide support and mentorship to female employees, gender disparities in the workplace are significantly reduced. Supportive managers play a crucial role in dismantling barriers and biases.

We also need to actively push for more diversity in our teams, especially in management roles. To increase inclusivity of course but also because diverse voices and views make a better Civil Service able to serve our communities more effectively. To do this, we need to increase awareness and educate our colleagues about the unique challenges faced by women from different cultures, ethnicities, and sexualities in the workplace. This means proactive not passive allyship – speak out against bias, advocate for opportunities, and become mentors and sponsors.

Let's normalise diversity

In Justice Digital, we strive to build an inclusive talent pipeline. We want a workplace culture where women feel valued, respected, and supported, to reduce the prevalence and likelihood of microaggressions and biases. That means standing up to poor behaviour, advocating for flexible working, and promoting the benefits of feminine, people-focused, leadership.

Since August of last year, we've welcomed 92 incredible women to Justice Digital, and we're eager to see this number continue to rise! We have also recently signed up to the Talent Tech Charter which aims to help organisations look at the different lenses of diversity and how these lenses impact strategies like recruitment, retention, and creating an inclusive culture.

As we celebrate International Women’s Day, we pay tribute to the resilience and perseverance of women who have blazed trails for progress and have allowed us to feel we have a place (and a voice) at the table. Let us all play our part in advocating for an inclusive and equitable workplace that embraces diversity and empowers all women.

Sharing and comments

Share this page, leave a comment.

Cancel reply

By submitting a comment you understand it may be published on this public website. Please read our privacy notice to see how the GOV.UK blogging platform handles your information.

Related content and links

Justice digital.

A blog about using digital and technology to transform services in the justice system.

More about Justice Digital

Working at Justice Digital

- Justice Digital on Twitter

- Justice Digital on LinkedIn

Sign up and manage updates

Our vulnerability disclosure policy.

How we work with the security research community to improve our online security

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. Take the first step today

Here’s your new year gift, one app for all your, study abroad needs, start your journey, track your progress, grow with the community and so much more.

Verification Code

An OTP has been sent to your registered mobile no. Please verify

Thanks for your comment !

Our team will review it before it's shown to our readers.

Essay on Gender Discrimination

- Updated on

- Jul 14, 2022

One of the challenges present in today’s society is gender discrimination. Gender discrimination is when someone is treated unequally based on their gender. Gender discrimination is not just present in the workplace but in schools, colleges and communities as well. As per the Civil Rights Act of 1964, gender discrimination is illegal in India. This is also an important and common essay topic in schools and competitive exams such as IELTS , TOEFL , SAT , UPSC , etc. Let’s explore some samples of essay on gender discrimination and tips for writing an impactful essay.

Tips for Writing an Impactful Essay

If you want to write a scoring and deep impact essay, here are some tips for writing a perfect informative essay:

- The most important and first step is to write an introduction and background information about and related to the topic

- Then you are also required to use the formal style of writing and avoid using slang language

- To make an essay more impactful, write dates, quotations, and names to provide a better understanding

- You can use jargon wherever it is necessary as it sometimes makes an essay complicated

- To make an essay more creative, you can also add information in bulleted points wherever possible

- Always remember to add a conclusion where you need to summarise crucial points

- Once you are done read through the lines and check spelling and grammar mistakes before submission

Essay on Gender Discrimination in 200 Words

One of the important aspects of a democratic society is the elimination of gender discrimination. The root cause of this vigorous disease is the stereotypical society itself. When a child is born, the discrimination begins; if the child is male, he is given a car, bat and ball with blue, and red colour clothes, whereas when a child is female, she is given barbie dolls with pink clothes. We all are raised with a mentality that boys are good at sports and messy, but girls are not good at sports and are well organised. This discriminatory mentality has a deeper impact when girls are told not to work while boys are allowed to do much work. This categorising males and females into different categories discriminating based on gender are known as gender discrimination. Further, this discriminatory behaviour in society leads to hatred, injustice and much more. This gender discrimination is evident in every woman’s life at the workplace, in educational institutions, in sports, etc., where young girls and women are deprived of their rights and undervalued. This major issue prevailing in society can be solved only by providing equality to women and giving them all rights as given to men.

Essay on Gender Discrimination in 300 Words

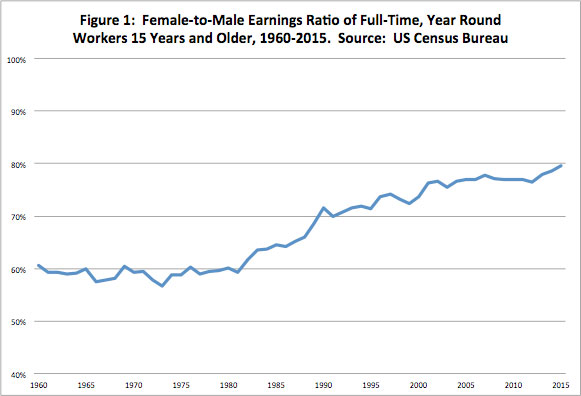

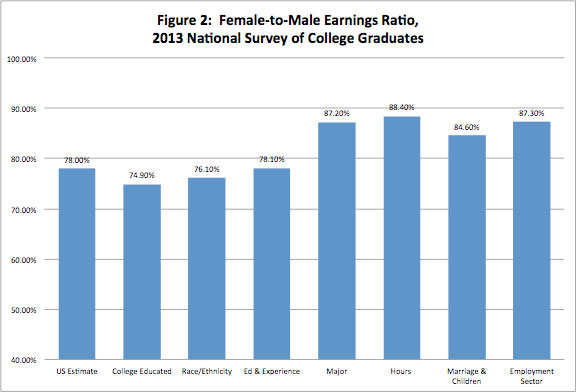

Gender Discrimination, as the term signifies, is discrimination or discriminatory behaviour based on gender. The stereotypical mindset of people in the past has led to the discrimination that women face today. According to Kahle Wolfe, in 2015, women earned 83% of the income paid to men by working the same hours. Almost all women are not only discriminated against based on their salaries but also on their looks.

Further, most women are allowed to follow a certain dress code depending upon the work field and the dress women wear also decides their future career.

This dominant male society teaches males that women are weak and innocent. Thus women are mostly victims and are targeted in crimes. For example, In a large portion of the globe, women are blamed for rapes despite being victims because of their clothes. This society also portrays women as weaker and not eligible enough to take a stand for themselves, leading to the major destruction of women’s personalities as men are taught to let women down. This mindset of people nowadays is a major social justice issue leading to gender discrimination in society.

Further, gender-based discrimination is evident across the globe in a plethora of things, including sports, education, health and law. Every 1 out of 3 women in the world is abused in various forms at some point in their lives by men. This social evil is present in most parts of the world; in India, women are burnt to death if they are incapable of affording financial requirements; in Egypt, women are killed by society if they are sensed doing something unclean in or out of their families, whereas in South Africa baby girls are abandoned or killed as they are considered as burden for the family. Thus gender discrimination can be only eliminated from society by educating people about giving equal rights and respect to every gender.

Top Universities for Gender Studies Abroad

UK, Canada and USA are the top three countries to study gender studies abroad. Here’s the list of top universities you can consider if you planning to pursue gender studies course abroad:

We hope this blog has helped you in structuring a terrific essay on gender discrimination. Planning to ace your IELTS, get expert tips from coaches at Leverage Live by Leverage Edu .

Sonal is a creative, enthusiastic writer and editor who has worked extensively for the Study Abroad domain. She splits her time between shooting fun insta reels and learning new tools for content marketing. If she is missing from her desk, you can find her with a group of people cracking silly jokes or petting neighbourhood dogs.

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Contact no. *

Leaving already?

8 Universities with higher ROI than IITs and IIMs

Grab this one-time opportunity to download this ebook

Connect With Us

25,000+ students realised their study abroad dream with us. take the first step today..

Resend OTP in

Need help with?

Study abroad.

UK, Canada, US & More

IELTS, GRE, GMAT & More

Scholarship, Loans & Forex

Country Preference

New Zealand

Which English test are you planning to take?

Which academic test are you planning to take.

Not Sure yet

When are you planning to take the exam?

Already booked my exam slot

Within 2 Months

Want to learn about the test

Which Degree do you wish to pursue?

When do you want to start studying abroad.

September 2024

January 2025

What is your budget to study abroad?

How would you describe this article ?

Please rate this article

We would like to hear more.

5 Powerful Essays Advocating for Gender Equality

Gender equality – which becomes reality when all genders are treated fairly and allowed equal opportunities – is a complicated human rights issue for every country in the world. Recent statistics are sobering. According to the World Economic Forum, it will take 108 years to achieve gender parity . The biggest gaps are found in political empowerment and economics. Also, there are currently just six countries that give women and men equal legal work rights. Generally, women are only given ¾ of the rights given to men. To learn more about how gender equality is measured, how it affects both women and men, and what can be done, here are five essays making a fair point.

Take a free course on Gender Equality offered by top universities!

“Countries With Less Gender Equity Have More Women In STEM — Huh?” – Adam Mastroianni and Dakota McCoy

This essay from two Harvard PhD candidates (Mastroianni in psychology and McCoy in biology) takes a closer look at a recent study that showed that in countries with lower gender equity, more women are in STEM. The study’s researchers suggested that this is because women are actually especially interested in STEM fields, and because they are given more choice in Western countries, they go with different careers. Mastroianni and McCoy disagree.

They argue the research actually shows that cultural attitudes and discrimination are impacting women’s interests, and that bias and discrimination is present even in countries with better gender equality. The problem may lie in the Gender Gap Index (GGI), which tracks factors like wage disparity and government representation. To learn why there’s more women in STEM from countries with less gender equality, a more nuanced and complex approach is needed.

“Men’s health is better, too, in countries with more gender equality” – Liz Plank

When it comes to discussions about gender equality, it isn’t uncommon for someone in the room to say, “What about the men?” Achieving gender equality has been difficult because of the underlying belief that giving women more rights and freedom somehow takes rights away from men. The reality, however, is that gender equality is good for everyone. In Liz Plank’s essay, which is an adaption from her book For the Love of Men: A Vision for Mindful Masculinity, she explores how in Iceland, the #1 ranked country for gender equality, men live longer. Plank lays out the research for why this is, revealing that men who hold “traditional” ideas about masculinity are more likely to die by suicide and suffer worse health. Anxiety about being the only financial provider plays a big role in this, so in countries where women are allowed education and equal earning power, men don’t shoulder the burden alone.

Liz Plank is an author and award-winning journalist with Vox, where she works as a senior producer and political correspondent. In 2015, Forbes named her one of their “30 Under 30” in the Media category. She’s focused on feminist issues throughout her career.

“China’s #MeToo Moment” – Jiayang Fan

Some of the most visible examples of gender inequality and discrimination comes from “Me Too” stories. Women are coming forward in huge numbers relating how they’ve been harassed and abused by men who have power over them. Most of the time, established systems protect these men from accountability. In this article from Jiayang Fan, a New Yorker staff writer, we get a look at what’s happening in China.

The essay opens with a story from a PhD student inspired by the United States’ Me Too movement to open up about her experience with an academic adviser. Her story led to more accusations against the adviser, and he was eventually dismissed. This is a rare victory, because as Fan says, China employs a more rigid system of patriarchy and hierarchy. There aren’t clear definitions or laws surrounding sexual harassment. Activists are charting unfamiliar territory, which this essay explores.

“Men built this system. No wonder gender equality remains as far off as ever.” – Ellie Mae O’Hagan

Freelance journalist Ellie Mae O’Hagan (whose book The New Normal is scheduled for a May 2020 release) is discouraged that gender equality is so many years away. She argues that it’s because the global system of power at its core is broken. Even when women are in power, which is proportionally rare on a global scale, they deal with a system built by the patriarchy. O’Hagan’s essay lays out ideas for how to fix what’s fundamentally flawed, so gender equality can become a reality.

Ideas include investing in welfare; reducing gender-based violence (which is mostly men committing violence against women); and strengthening trade unions and improving work conditions. With a system that’s not designed to put women down, the world can finally achieve gender equality.

“Invisibility of Race in Gender Pay Gap Discussions” – Bonnie Chu

The gender pay gap has been a pressing issue for many years in the United States, but most discussions miss the factor of race. In this concise essay, Senior Contributor Bonnie Chu examines the reality, writing that within the gender pay gap, there’s other gaps when it comes to black, Native American, and Latina women. Asian-American women, on the other hand, are paid 85 cents for every dollar. This data is extremely important and should be present in discussions about the gender pay gap. It reminds us that when it comes to gender equality, there’s other factors at play, like racism.

Bonnie Chu is a gender equality advocate and a Forbes 30 Under 30 social entrepreneur. She’s the founder and CEO of Lensational, which empowers women through photography, and the Managing Director of The Social Investment Consultancy.

You may also like

12 Ways Poverty Affects Society

15 Great Charities to Donate to in 2024

15 Quotes Exposing Injustice in Society

14 Trusted Charities Helping Civilians in Palestine

The Great Migration: History, Causes and Facts

Social Change 101: Meaning, Examples, Learning Opportunities

Rosa Parks: Biography, Quotes, Impact

Top 20 Issues Women Are Facing Today

Top 20 Issues Children Are Facing Today

15 Root Causes of Climate Change

15 Facts about Rosa Parks

Abolitionist Movement: History, Main Ideas, and Activism Today

About the author, emmaline soken-huberty.

Emmaline Soken-Huberty is a freelance writer based in Portland, Oregon. She started to become interested in human rights while attending college, eventually getting a concentration in human rights and humanitarianism. LGBTQ+ rights, women’s rights, and climate change are of special concern to her. In her spare time, she can be found reading or enjoying Oregon’s natural beauty with her husband and dog.

A global story

This piece is part of 19A: The Brookings Gender Equality Series . In this essay series, Brookings scholars, public officials, and other subject-area experts examine the current state of gender equality 100 years after the 19th Amendment was adopted to the U.S. Constitution and propose recommendations to cull the prevalence of gender-based discrimination in the United States and around the world.

The year 2020 will stand out in the history books. It will always be remembered as the year the COVID-19 pandemic gripped the globe and brought death, illness, isolation, and economic hardship. It will also be noted as the year when the death of George Floyd and the words “I can’t breathe” ignited in the United States and many other parts of the world a period of reckoning with racism, inequality, and the unresolved burdens of history.

The history books will also record that 2020 marked 100 years since the ratification of the 19th Amendment in America, intended to guarantee a vote for all women, not denied or abridged on the basis of sex.

This is an important milestone and the continuing movement for gender equality owes much to the history of suffrage and the brave women (and men) who fought for a fairer world. Yet just celebrating what was achieved is not enough when we have so much more to do. Instead, this anniversary should be a galvanizing moment when we better inform ourselves about the past and emerge more determined to achieve a future of gender equality.

Australia’s role in the suffrage movement

In looking back, one thing that should strike us is how international the movement for suffrage was though the era was so much less globalized than our own.

For example, how many Americans know that 25 years before the passing of the 19th Amendment in America, my home of South Australia was one of the first polities in the world to give men and women the same rights to participate in their democracies? South Australia led Australia and became a global leader in legislating universal suffrage and candidate eligibility over 125 years ago.

This extraordinary achievement was not an easy one. There were three unsuccessful attempts to gain equal voting rights for women in South Australia, in the face of relentless opposition. But South Australia’s suffragists—including the Women’s Suffrage League and the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union, as well as remarkable women like Catherine Helen Spence, Mary Lee, and Elizabeth Webb Nicholls—did not get dispirited but instead continued to campaign, persuade, and cajole. They gathered a petition of 11,600 signatures, stuck it together page by page so that it measured around 400 feet in length, and presented it to Parliament.

The Constitutional Amendment (Adult Suffrage) Bill was finally introduced on July 4, 1894, leading to heated debate both within the houses of Parliament, and outside in society and the media. Demonstrating that some things in Parliament never change, campaigner Mary Lee observed as the bill proceeded to committee stage “that those who had the least to say took the longest time to say it.” 1

The Bill finally passed on December 18, 1894, by 31 votes to 14 in front of a large crowd of women.

In 1897, Catherine Helen Spence became the first woman to stand as a political candidate in South Australia.

South Australia’s victory led the way for the rest of the colonies, in the process of coming together to create a federated Australia, to fight for voting rights for women across the entire nation. Women’s suffrage was in effect made a precondition to federation in 1901, with South Australia insisting on retaining the progress that had already been made. 2 South Australian Muriel Matters, and Vida Goldstein—a woman from the Australian state of Victoria—are just two of the many who fought to ensure that when Australia became a nation, the right of women to vote and stand for Parliament was included.

Australia’s remarkable progressiveness was either envied, or feared, by the rest of the world. Sociologists and journalists traveled to Australia to see if the worst fears of the critics of suffrage would be realised.

In 1902, Vida Goldstein was invited to meet President Theodore Roosevelt—the first Australian to ever meet a U.S. president in the White House. With more political rights than any American woman, Goldstein was a fascinating visitor. In fact, President Roosevelt told Goldstein: “I’ve got my eye on you down in Australia.” 3

Goldstein embarked on many other journeys around the world in the name of suffrage, and ran five times for Parliament, emphasising “the necessity of women putting women into Parliament to secure the reforms they required.” 4

Muriel Matters went on to join the suffrage movement in the United Kingdom. In 1908 she became the first woman to speak in the British House of Commons in London—not by invitation, but by chaining herself to the grille that obscured women’s views of proceedings in the Houses of Parliament. After effectively cutting her off the grille, she was dragged out of the gallery by force, still shouting and advocating for votes for women. The U.K. finally adopted women’s suffrage in 1928.

These Australian women, and the many more who tirelessly fought for women’s rights, are still extraordinary by today’s standards, but were all the more remarkable for leading the rest of the world.

A shared history of exclusion

Of course, no history of women’s suffrage is complete without acknowledging those who were excluded. These early movements for gender equality were overwhelmingly the remit of privileged white women. Racially discriminatory exclusivity during the early days of suffrage is a legacy Australia shares with the United States.

South Australian Aboriginal women were given the right to vote under the colonial laws of 1894, but they were often not informed of this right or supported to enroll—and sometimes were actively discouraged from participating.

They were later further discriminated against by direct legal bar by the 1902 Commonwealth Franchise Act, whereby Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people were excluded from voting in federal elections—a right not given until 1962.

Any celebration of women’s suffrage must acknowledge such past injustices front and center. Australia is not alone in the world in grappling with a history of discrimination and exclusion.

The best historical celebrations do not present a triumphalist version of the past or convey a sense that the fight for equality is finished. By reflecting on our full history, these celebrations allow us to come together, find new energy, and be inspired to take the cause forward in a more inclusive way.

The way forward

In the century or more since winning women’s franchise around the world, we have made great strides toward gender equality for women in parliamentary politics. Targets and quotas are working. In Australia, we already have evidence that affirmative action targets change the diversity of governments. Since the Australian Labor Party (ALP) passed its first affirmative action resolution in 1994, the party has seen the number of women in its national parliamentary team skyrocket from around 14% to 50% in recent years.

Instead of trying to “fix” women—whether by training or otherwise—the ALP worked on fixing the structures that prevent women getting preselected, elected, and having fair opportunities to be leaders.

There is also clear evidence of the benefits of having more women in leadership roles. A recent report from Westminster Foundation for Democracy and the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership (GIWL) at King’s College London, shows that where women are able to exercise political leadership, it benefits not just women and girls, but the whole of society.

But even though we know how to get more women into parliament and the positive difference they make, progress toward equality is far too slow. The World Economic Forum tells us that if we keep progressing as we are, the global political empowerment gender gap—measuring the presence of women across Parliament, ministries, and heads of states across the world— will only close in another 95 years . This is simply too long to wait and, unfortunately, not all barriers are diminishing. The level of abuse and threatening language leveled at high-profile women in the public domain and on social media is a more recent but now ubiquitous problem, which is both alarming and unacceptable.

Across the world, we must dismantle the continuing legal and social barriers that prevent women fully participating in economic, political, and community life.

Education continues to be one such barrier in many nations. Nearly two-thirds of the world’s illiterate adults are women. With COVID-19-related school closures happening in developing countries, there is a real risk that progress on girls’ education is lost. When Ebola hit, the evidence shows that the most marginalized girls never made it back to school and rates of child marriage, teen pregnancy. and child labor soared. The Global Partnership for Education, which I chair, is currently hard at work trying to ensure that this history does not repeat.

Ensuring educational equality is a necessary but not sufficient condition for gender equality. In order to change the landscape to remove the barriers that prevent women coming through for leadership—and having their leadership fairly evaluated rather than through the prism of gender—we need a radical shift in structures and away from stereotypes. Good intentions will not be enough to achieve the profound wave of change required. We need hard-headed empirical research about what works. In my life and writings post-politics and through my work at the GIWL, sharing and generating this evidence is front and center of the work I do now.

GIWL work, undertaken in partnership with IPSOS Mori, demonstrates that the public knows more needs to be done. For example, this global polling shows the community thinks it is harder for women to get ahead. Specifically, they say men are less likely than women to need intelligence and hard work to get ahead in their careers.

Other research demonstrates that the myth of the “ideal worker,” one who works excessive hours, is damaging for women’s careers. We also know from research that even in families where each adult works full time, domestic and caring labor is disproportionately done by women. 5

In order to change the landscape to remove the barriers that prevent women coming through for leadership—and having their leadership fairly evaluated rather than through the prism of gender—we need a radical shift in structures and away from stereotypes.

Other more subtle barriers, like unconscious bias and cultural stereotypes, continue to hold women back. We need to start implementing policies that prevent people from being marginalized and stop interpreting overconfidence or charisma as indicative of leadership potential. The evidence shows that it is possible for organizations to adjust their definitions and methods of identifying merit so they can spot, measure, understand, and support different leadership styles.

Taking the lessons learned from our shared history and the lives of the extraordinary women across the world, we know evidence needs to be combined with activism to truly move forward toward a fairer world. We are in a battle for both hearts and minds.

Why this year matters

We are also at an inflection point. Will 2020 will be remembered as the year that a global recession disproportionately destroyed women’s jobs, while women who form the majority of the workforce in health care and social services were at risk of contracting the coronavirus? Will it be remembered as a time of escalating domestic violence and corporations cutting back on their investments in diversity programs?

Or is there a more positive vision of the future that we can seize through concerted advocacy and action? A future where societies re-evaluate which work truly matters and determine to better reward carers. A time when men and women forced into lockdowns re-negotiated how they approach the division of domestic labor. Will the pandemic be viewed as the crisis that, through forcing new ways of virtual working, ultimately led to more balance between employment and family life, and career advancement based on merit and outcomes, not presentism and the old boys’ network?

This history is not yet written. We still have an opportunity to make it happen. Surely the women who led the way 100 years ago can inspire us to seize this moment and create that better, more gender equal future.

- December 7,1894: Welcome home meeting for Catherine Helen Spence at the Café de Paris. [ Register , Dec, 19, 1894 ]

- Clare Wright, You Daughters of Freedom: The Australians Who Won the Vote and Inspired the World , (Text Publishing, 2018).

- Janette M. Bomford, That Dangerous and Persuasive Woman, (Melbourne University Press, 1993)

- Cordelia Fine, Delusions of Gender: The Real Science Behind Sex Differences, (Icon Books, 2010)

This piece is part of 19A: The Brookings Gender Equality Series. Learn more about the series and read published work »

About the Author

Julia gillard, distinguished fellow – global economy and development, center for universal education.

Gillard is a distinguished fellow with the Center for Universal Education at the Brookings Institution. She is the Inaugural Chair of the Global Institute for Women’s Leadership at King’s College London. Gillard also serves as Chair of the Global Partnership for Education, which is dedicated to expanding access to quality education worldwide and is patron of CAMFED, the Campaign for Female Education.

Read full bio

MORE FROM JULIA GILLARD

Advancing women’s leadership around the world

More from the 19a series.

The gender revolution is stalling—What would reinvigorate it?

What’s necessary to reinvigorate the gender revolution and create progress in the areas where the movement toward equality has slowed or stalled—employment, desegregation of fields of study and jobs, and the gender pay gap?

The fate of women’s rights in Afghanistan

John R. Allen and Vanda Felbab-Brown write that as peace negotiations between the Afghan government and the Taliban commence, uncertainty hangs over the fate of Afghan women and their rights.

- Media Relations

- Terms and Conditions

- Privacy Policy

What does gender equality look like today?

Date: Wednesday, 6 October 2021

Progress towards gender equality is looking bleak. But it doesn’t need to.

A new global analysis of progress on gender equality and women’s rights shows women and girls remain disproportionately affected by the socioeconomic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic, struggling with disproportionately high job and livelihood losses, education disruptions and increased burdens of unpaid care work. Women’s health services, poorly funded even before the pandemic, faced major disruptions, undermining women’s sexual and reproductive health. And despite women’s central role in responding to COVID-19, including as front-line health workers, they are still largely bypassed for leadership positions they deserve.

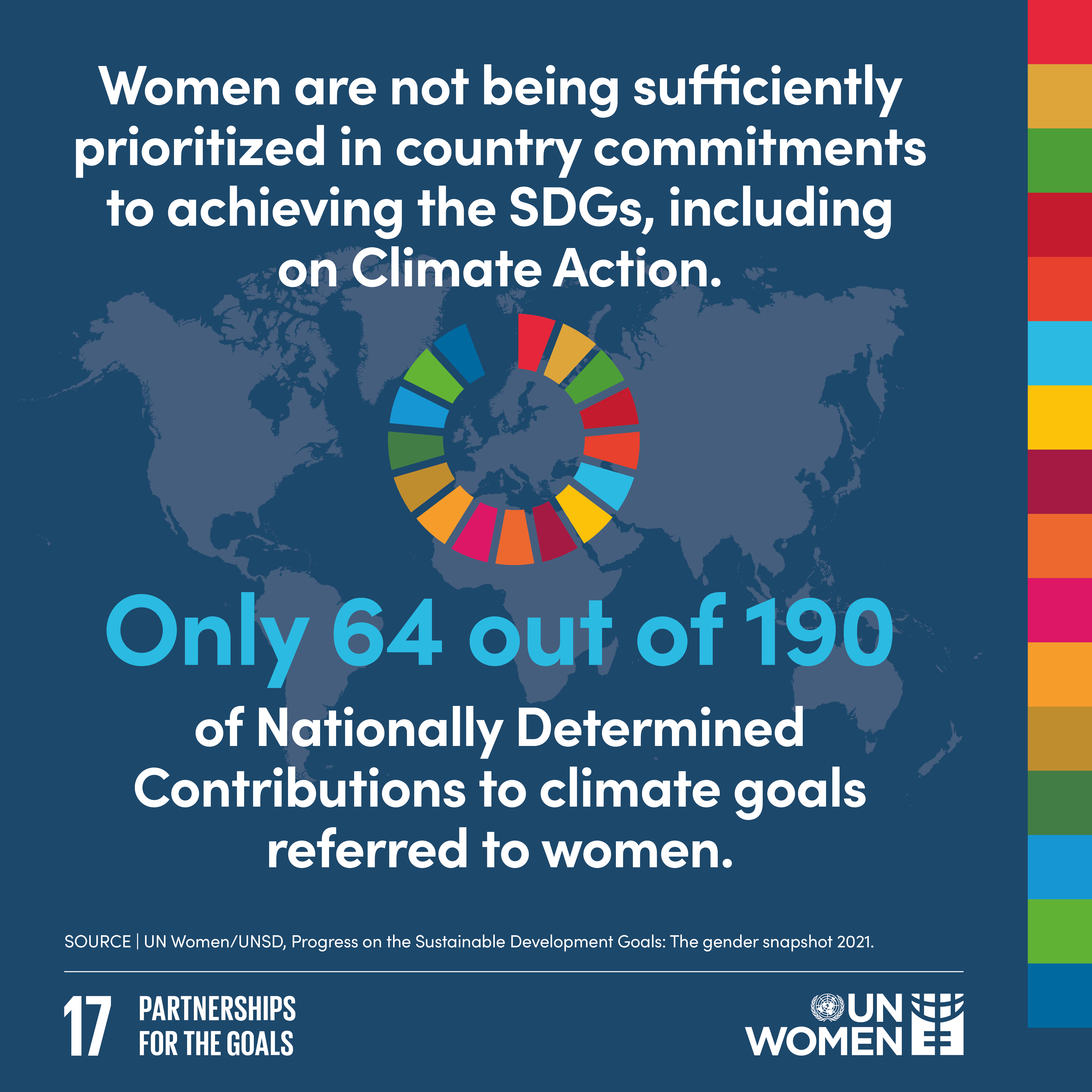

UN Women’s latest report, together with UN DESA, Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The Gender Snapshot 2021 presents the latest data on gender equality across all 17 Sustainable Development Goals. The report highlights the progress made since 2015 but also the continued alarm over the COVID-19 pandemic, its immediate effect on women’s well-being and the threat it poses to future generations.

We’re breaking down some of the findings from the report, and calling for the action needed to accelerate progress.

The pandemic is making matters worse

One and a half years since the World Health Organization declared COVID-19 a global pandemic, the toll on the poorest and most vulnerable people remains devastating and disproportionate. The combined impact of conflict, extreme weather events and COVID-19 has deprived women and girls of even basic needs such as food security. Without urgent action to stem rising poverty, hunger and inequality, especially in countries affected by conflict and other acute forms of crisis, millions will continue to suffer.

A global goal by global goal reality check:

Goal 1. Poverty

In 2021, extreme poverty is on the rise and progress towards its elimination has reversed. An estimated 435 million women and girls globally are living in extreme poverty.

And yet we can change this .

Over 150 million women and girls could emerge from poverty by 2030 if governments implement a comprehensive strategy to improve access to education and family planning, achieve equal wages and extend social transfers.

Goal 2. Zero hunger

The global gender gap in food security has risen dramatically during the pandemic, with more women and girls going hungry. Women’s food insecurity levels were 10 per cent higher than men’s in 2020, compared with 6 per cent higher in 2019.

This trend can be reversed , including by supporting women small-scale producers, who typically earn far less than men, through increased funding, training and land rights reforms.

Goal 3. Good health and well-being

Disruptions in essential health services due to COVID-19 are taking a tragic toll on women and girls. In the first year of the pandemic, there were an estimated 1.4 million additional unintended pregnancies in lower and middle-income countries.

We need to do better .

Response to the pandemic must include prioritizing sexual and reproductive health services, ensuring they continue to operate safely now and after the pandemic is long over. In addition, more support is needed to ensure life-saving personal protection equipment, tests, oxygen and especially vaccines are available in rich and poor countries alike as well as to vulnerable population within countries.

Goal 4. Quality education

A year and a half into the pandemic, schools remain partially or fully closed in 42 per cent of the world’s countries and territories. School closures spell lost opportunities for girls and an increased risk of violence, exploitation and early marriage .

Governments can do more to protect girls education .

Measures focused specifically on supporting girls returning to school are urgently needed, including measures focused on girls from marginalized communities who are most at risk.

Goal 5. Gender equality

The pandemic has tested and even reversed progress in expanding women’s rights and opportunities. Reports of violence against women and girls, a “shadow” pandemic to COVID-19, are increasing in many parts of the world. COVID-19 is also intensifying women’s workload at home, forcing many to leave the labour force altogether.

Building forward differently and better will hinge on placing women and girls at the centre of all aspects of response and recovery, including through gender-responsive laws, policies and budgeting.

Goal 6. Clean water and sanitation

In 2018, nearly 2.3 billion people lived in water-stressed countries. Without safe drinking water, adequate sanitation and menstrual hygiene facilities, women and girls find it harder to lead safe, productive and healthy lives.

Change is possible .

Involve those most impacted in water management processes, including women. Women’s voices are often missing in water management processes.

Goal 7. Affordable and clean energy

Increased demand for clean energy and low-carbon solutions is driving an unprecedented transformation of the energy sector. But women are being left out. Women hold only 32 per cent of renewable energy jobs.

We can do better .

Expose girls early on to STEM education, provide training and support to women entering the energy field, close the pay gap and increase women’s leadership in the energy sector.

Goal 8. Decent work and economic growth

The number of employed women declined by 54 million in 2020 and 45 million women left the labour market altogether. Women have suffered steeper job losses than men, along with increased unpaid care burdens at home.

We must do more to support women in the workforce .

Guarantee decent work for all, introduce labour laws/reforms, removing legal barriers for married women entering the workforce, support access to affordable/quality childcare.

Goal 9. Industry, innovation and infrastructure

The COVID-19 crisis has spurred striking achievements in medical research and innovation. Women’s contribution has been profound. But still only a little over a third of graduates in the science, technology, engineering and mathematics field are female.

We can take action today.

Quotas mandating that a proportion of research grants are awarded to women-led teams or teams that include women is one concrete way to support women researchers.

Goal 10. Reduced inequalities

Limited progress for women is being eroded by the pandemic. Women facing multiple forms of discrimination, including women and girls with disabilities, migrant women, women discriminated against because of their race/ethnicity are especially affected.

Commit to end racism and discrimination in all its forms, invest in inclusive, universal, gender responsive social protection systems that support all women.

Goal 11. Sustainable cities and communities

Globally, more than 1 billion people live in informal settlements and slums. Women and girls, often overrepresented in these densely populated areas, suffer from lack of access to basic water and sanitation, health care and transportation.

The needs of urban poor women must be prioritized .

Increase the provision of durable and adequate housing and equitable access to land; included women in urban planning and development processes.

Goal 12. Sustainable consumption and production; Goal 13. Climate action; Goal 14. Life below water; and Goal 15. Life on land

Women activists, scientists and researchers are working hard to solve the climate crisis but often without the same platforms as men to share their knowledge and skills. Only 29 per cent of featured speakers at international ocean science conferences are women.

And yet we can change this .

Ensure women activists, scientists and researchers have equal voice, representation and access to forums where these issues are being discussed and debated.

Goal 16. Peace, justice and strong institutions

The lack of women in decision-making limits the reach and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic and other emergency recovery efforts. In conflict-affected countries, 18.9 per cent of parliamentary seats are held by women, much lower than the global average of 25.6 per cent.

This is unacceptable .

It's time for women to have an equal share of power and decision-making at all levels.

Goal 17. Global partnerships for the goals

There are just 9 years left to achieve the Global Goals by 2030, and gender equality cuts across all 17 of them. With COVID-19 slowing progress on women's rights, the time to act is now.

Looking ahead

As it stands today, only one indicator under the global goal for gender equality (SDG5) is ‘close to target’: proportion of seats held by women in local government. In other areas critical to women’s empowerment, equality in time spent on unpaid care and domestic work and decision making regarding sexual and reproductive health the world is far from target. Without a bold commitment to accelerate progress, the global community will fail to achieve gender equality. Building forward differently and better will require placing women and girls at the centre of all aspects of response and recovery, including through gender-responsive laws, policies and budgeting.

- ‘One Woman’ – The UN Women song

- UN Under-Secretary-General and UN Women Executive Director Sima Bahous

- Kirsi Madi, Deputy Executive Director for Resource Management, Sustainability and Partnerships

- Nyaradzayi Gumbonzvanda, Deputy Executive Director for Normative Support, UN System Coordination and Programme Results

- Guiding documents

- Report wrongdoing

- Programme implementation

- Career opportunities

- Application and recruitment process

- Meet our people

- Internship programme

- Procurement principles

- Gender-responsive procurement

- Doing business with UN Women

- How to become a UN Women vendor

- Contract templates and general conditions of contract

- Vendor protest procedure

- Facts and Figures

- Global norms and standards

- Women’s movements

- Parliaments and local governance

- Constitutions and legal reform

- Preguntas frecuentes

- Global Norms and Standards

- Macroeconomic policies and social protection

- Sustainable Development and Climate Change

- Rural women

- Employment and migration

- Facts and figures

- Creating safe public spaces

- Spotlight Initiative

- Essential services

- Focusing on prevention

- Research and data

- Other areas of work

- UNiTE campaign

- Conflict prevention and resolution

- Building and sustaining peace

- Young women in peace and security

- Rule of law: Justice and security

- Women, peace, and security in the work of the UN Security Council

- Preventing violent extremism and countering terrorism

- Planning and monitoring

- Humanitarian coordination

- Crisis response and recovery

- Disaster risk reduction

- Inclusive National Planning

- Public Sector Reform

- Tracking Investments

- Strengthening young women's leadership

- Economic empowerment and skills development for young women

- Action on ending violence against young women and girls

- Engaging boys and young men in gender equality

- Sustainable development agenda

- Leadership and Participation

- National Planning

- Violence against Women

- Access to Justice

- Regional and country offices

- Regional and Country Offices

- Liaison offices

- UN Women Global Innovation Coalition for Change

- Commission on the Status of Women

- Economic and Social Council

- General Assembly

- Security Council

- High-Level Political Forum on Sustainable Development

- Human Rights Council

- Climate change and the environment

- Other Intergovernmental Processes

- World Conferences on Women

- Global Coordination

- Regional and country coordination

- Promoting UN accountability

- Gender Mainstreaming

- Coordination resources

- System-wide strategy

- Focal Point for Women and Gender Focal Points

- Entity-specific implementation plans on gender parity

- Laws and policies

- Strategies and tools

- Reports and monitoring

- Training Centre services

- Publications

- Government partners

- National mechanisms

- Civil Society Advisory Groups

- Benefits of partnering with UN Women

- Business and philanthropic partners

- Goodwill Ambassadors

- National Committees

- UN Women Media Compact

- UN Women Alumni Association

- Editorial series

- Media contacts

- Annual report

- Progress of the world’s women

- SDG monitoring report

- World survey on the role of women in development

- Reprint permissions

- Secretariat

- 2023 sessions and other meetings

- 2022 sessions and other meetings

- 2021 sessions and other meetings

- 2020 sessions and other meetings

- 2019 sessions and other meetings

- 2018 sessions and other meetings

- 2017 sessions and other meetings

- 2016 sessions and other meetings

- 2015 sessions and other meetings

- Compendiums of decisions

- Reports of sessions

- Key Documents

- Brief history

- CSW snapshot

- Preparations

- Official Documents

- Official Meetings

- Side Events

- Session Outcomes

- CSW65 (2021)

- CSW64 / Beijing+25 (2020)

- CSW63 (2019)

- CSW62 (2018)

- CSW61 (2017)

- Member States

- Eligibility

- Registration

- Opportunities for NGOs to address the Commission

- Communications procedure

- Grant making

- Accompaniment and growth

- Results and impact

- Knowledge and learning

- Social innovation

- UN Trust Fund to End Violence against Women

- About Generation Equality

- Generation Equality Forum

- Action packs

Gender Sensitivity and Its Relation to Gender Equality

- Reference work entry

- First Online: 01 January 2021

- Cite this reference work entry

- Juana Figueroa Vélez 6 &

- Susana Vélez Ochoa 6

Part of the book series: Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals ((ENUNSDG))

179 Accesses

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

Institutional subscriptions

Abrahams N (1996) Negotiating power, identity, family, and community: women’s community participation. Gend Soc 10(6):768–796

Article Google Scholar

Acker J (1990) Hierarchies, jobs, and bodies: a theory of gendered organizations. Gend Soc 4:139–158

Adler RD (2001) Women in the executive suite correlate to high profits. Harv Bus Rev 79(3). Retrieved from: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/267822127_Women_in_the_Executive_Suite_Correlate_to_High_Profits

Bertrand M (2018) The glass ceiling. Becker Friedman Institute for Research in Economics (38). https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3191467 . Accessed 19 May 2019

Blair IV, Banaji RM (1996) Automatic and controlled processes in stereotype priming. J Pers Soc Psychol 70(1):142–163

Google Scholar

Bookman A, Morgen S (eds) (1988) Women and the politics of empowerment. Temple University Press, Philadelphia

Brehm SS, Brehm JW (1981) Psychological reactance. Academic, New York

Burke MJ, Salvador RO, Smith-Crowe K, Cahn-Serafin S, Smith A, Sonesh S (2011) The dread factor: how hazards and safety training influence learning and performance. J Appl Psychol 96:46–70

Chattopadhyay R, Duflo E. (2004) Impact of reservation in Panchayati Raj: evidence from a nationwide randomised experiment. Economic and Political Weekly 39(9):979–986. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4414710

Christodoulou J (2005) Glossary of gender-related terms. Mediterranean Institute of Gender Studies. European Institute for Gender Equality. https://medinstgenderstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/Gender-Glossary-updated_final.pdf

Conway M (2000) Political participation in the United States, 3rd edn. CQ Press, Washington, DC

Conway M (2001) Women’s political participation. Polit Sci Polit 34(2):231–233

Conway M, Pizzamiglio MT, Mount L (1996) Status, communality, and agency: implications for stereotypes of gender and other groups. J Pers Soc Psychol 71:25–38

Article CAS Google Scholar

Crenshaw K (1991) Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev 43(6):1241–1299. https://doi.org/10.2307/1229039

Daniels AK (1988) Invisible careers. University of Chicago Press, Chicago

Davis (1989) Women, culture, and politics. Vintage, New York

EIGE (2015) European institute for gender equality. Gender Equality Commission of the Council of Europe. Gender Equality Glossary. http://www.coe.int/t/DGHL/STANDARDSETTING/EQUALITY/06resources/Glossarie… . Accessed 22 May 2019

Eubank D, Orzano J, Geffken D, Ricci R (2011) Teaching team membership to family medicine residents: what does it take? Fam Syst Health 29:29–43

Farrelly C (2011) Patriarchy and historical materialism. Hypatia 26(1):1–21. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23016676

Fowler L (1993) Candidates, congress, and the American democracy. University of Michigan Press, Ann Arbor

Book Google Scholar

Gilke CT (1980) “Holding back the ocean with a broom”: Black women and community work. In: La Frances Rodgers-Rose (ed) The Black woman. SAGE, Beverly Hills

Gilke CT (1994) If it wasn’t for the women…: African American women, community work, and social change. In: Zinn MB, Dill BT (eds) Women of color in U-S. Society. Temple University Press, Philadelphia

Glick P, Fiske ST (1999) Gender, power dynamics, and social interaction. In: Ferree M, Lorber J, Hess BB (eds) Revisioning gender. SAGE, Thousand Oaks

Glick P, Fiske ST (2001) An ambivalent alliance: hostile and benevolent sexism as complementary justifications for gender inequality. Am Psychol 56:109–118

Hardy-Fante C (1993) Latina politics, Latino politics. Temple University Press, Philadelphia

Hunnicutt G (2009) Varieties of patriarchy and violence against women: resurrecting “patriarchy” as a theoretical tool. Violence Against Women 15(5):553–573. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801208331246

IISD (2017) Achieve gender equality to deliver the SDG’s. http://sdg.iisd.org/commentary/policy-briefs/achieve-gender-equality-to-deliver-the-sdgs/ . Accessed 25 May 2019

Ito TA, Urland GR (2003) Race and gender on the brain: electrocortical measures of attention to the race and gender of multiply categorizable individuals. J Pers Soc Psychol 85:616–626

Kaminer W (1984) Women volunteering. Anchor, Garden City

Kattsoff LO (1948) What is behavior? Philos Phenomen Res 9(1):98–102. https://www.jstor.org/stable/2103854 . Accessed 03 June 2019 19:30 UTC

Keays T, McEvoy M, Murison S, Jennings M, Karim F (2001) Gender analysis, UNDP. Available via UNDP: https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/gender/Institutional%20Development/TLGEN1.6%20UNDP%20GenderAnalysis%20toolkit.pdf . Accessed 15 May 2019

Keeton M, Tate PJ (1978) In: Keeton M. Tate PJ (eds) Learning by experience-what, why, how. Jossey-Bass, San Francisco. In: Kolb DA. (2014) Introduction. In: Experiential learning: experience as the source of learning and development. (Kolb DA ed), Pearson Education Inc, Upper Saddle River, p 18

Klingorová K, Havlíček T (2015) Religion and gender inequality: the status of women in the societies of world religions. Moravian Geogr Rep 23(2):2–11. https://doi.org/10.1515/mgr-2015-0006

Kunda Z, Spencer SJ (2003) When do stereotypes come to mind and when do they color judgement? A goal- based theoretical framework for stereotype activation and application. Psychol Bull 129:522–544

Leduc B, Ahmad F (2009) Guidelines for gender sensitive programming. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242570417_Guidelines_for_Gender_Sensitive_Programming . Accessed 28 May 2019

Lorber J (1994) Paradoxes of gender. Yale University Press, New Haven

MacRae ER, Clasen T, Dasmohapatra M, Caruso BA (2019) ‘It’s like a burden on the head’: redefining adequate menstrual hygiene management throughout women's varied life stages in Odisha, India. PLoS One 14(8):e0220114. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220114

McGlen N, O’Connor K (1998) Women, politics, and public policy. Prentice Hall, Upper Saddle River

McIntosh P (1988) White privilege and male privilege: a personal account of coming to see correspondences through work in women’s studies, pp 94–105. https://www.collegeart.org/pdf/diversity/white-privilege-and-male-privilege.pdf . Accessed 13 May 2019

Merida LJ (2013) Breaking the glass ceiling: structural, cultural, and organizational barriers preventing women from achieving senior and executive positions. Perspect Health Inf Manag 10(Winter): 1e. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3544145/ . Accessed 8 May 2019

Nagel J (1994) Constructing ethnicity: creating and recreating ethnic identity and culture. Soc Probl 41:152–176

Naples NA (1991) “Just what needed to be done”: the political practice of women community workers in low income neighborhoods. Gend Soc 5:478–494. www.jstor.org/stable/190096 . Accessed 15 May 2019

Naples NA (1992) Activist mothering: cross-generational continuity in the community work of women from low-income urban neighborhoods. Gend Soc 6:441–463. https://doi.org/10.1177/089124392006003006

Rees T (2000) Mainstreaming equality in the European Union, education, training and labour market policies. Routledge, London

Ridgeway CL (2006) Gender as an organizing force in social relations: implications for the future of inequality. In: Blau FD, Brinton MC, Grusky DB (eds) The declining significance of gender? Russell Sage Foundation, New York

Ridgeway CL (2009) Framed before we know it: how gender shapes social relations. Gend Soc 23:145. http://gas.sagepub.com/content/23/2/145 . https://doi.org/10.1177/0891243208330313

Ridgeway CL, England P (2007) Sociological approaches to sex discrimination in employment. In: Crosby FM, Stockdale MS, Ropp AS (eds) Sex discrimination in the workplace: multidisciplinary perspectives. Blackwell, Oxford, UK

Ridgeway CL, Smith-Lovin L (1999) The gender system in interaction. Annu Rev Sociol 25:191–216. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.soc.25.1.191

Rinehart ST (1992) Gender consciousness and politics. Routledge, New York

Risman BJ (1998) Gender vertigo: American families in transition. Yale University Press, New Haven

Risman BJ (2004) Gender as a social structure: theory wrestling with activism. Gend Soc 18(4):429–451

Robbins CK, McGowan BL (2016) Intersectional perspectives on gender and gender identity development. New Dir Stud Serv (154):71–83. https://doi.org/10.1002/ss.20176

Rogers C (1967) On becoming a person. Constable, London

Sanz B, Evaluation Office, UN Women (2012) Steps to commission and carry out Gender Equality Evaluations. In: Workshop gender-sensitive evaluation: key ideas to commission and carry out it, 10th EES Biennial Conference

Sarikakis K, Shade LR (2012) Feminist interventions in international communication: minding the gap. Littlefield publishers, Toronto

Schilt K, Westbrook L (2009) Doing gender, doing heteronormativity: “Gender normals”, transgender people, and the social maintenance of heterosexuality. Gend Soc 23(4):440–464

Schulpen TWJ (2017) The glass ceiling: a biological phenomenon. Med Hypothesis 106:41–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mehy.2017.07.002

Sczesny S, Formanowics M, Moser F (2016) Can gender-fair language reduce gender sterotyping and discrimination? Front Psychol 7:25. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00025

Sinclair K (1986) Women and religion. In: Dudley MI, Edwards MI (eds) The cross-cultural study of women: a comprehensive guide. The Feminist Press, New York, pp 107–124

Snow DA, Burke Rochford E Jr, Wordden SK, Benford RD (1986) Frame alignment process, micromobilization, and movement participation. Am Sociol Rev 51:464–481

Sommer M, Hirsch JS, Nathanson C, Parker RG (2015) Comfortably, safely, and without shame: defining menstrual hygiene management as a public health issue. Am J Public Health 105(7):1302–1311. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2014.302525

Stangor C, Lynch L, Duan C, Glass B (1992) Categorization of individuals on the basis of multiple social features. J Pers Soc Psychol 62:207–218

Stump R (2008) The geography of religion: faith, place, and space. Rowman and Littlefield Publishers, Lanham. In: Klingorová K, Havlíček T, 2015. Religion and gender inequality: the status of women in the societies of world religions. Moravian Geographical Reports 23(2):2–11

Swim JK, Aiken KJ, Hall WS, hunter BA (1995) Sexism and racism: old-fashioned and modern prejudices. J Pers Soc Psychol 68:199–214

Thompson J, McGivern J (1995) Sexism in the seminar: strategies for gender sensitivity in management education. Gend Educ 7(3):341–350. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540259550039040

UN Women (2016) Scoring for gender equality through sport. https://lac.unwomen.org/en/noticias-y-eventos/articulos/2016/09/anotar-puntos-para-la-igualdad . Accessed 15 May 2019

UN Women (2019a) Equal pay for work of equal value. http://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/csw61/equal-pay . Accessed 15 May 2019

UN Women (2019b) Facts and figures: Leadership and political participation. https://www.unwomen.org/en/what-we-do/leadership-and-political-participation/facts-and-figures . Accesed 15 June 2019

UNDP (2001) Gender in development programme learning & information pack. https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/gender/Institutional%20Development/TLGEN1.6%20UNDP%20GenderAnalysis%20toolkit.pdf . Accessed 15 May 2019

UNESCO (2011) Priority gender equality guidelines. http://www.unesco.org/new/fileadmin/MULTIMEDIA/HQ/BSP/GENDER/GE%20Guidelines%20December%202_FINAL.pdf . Accessed 15 May 2019

UNIFEM (2007) United Nations Development Fund for Women. Policy briefing paper: gender sensitive police reform in post conflict societies. https://www.undp.org/content/dam/undp/library/gender/Gender%20and%20CPR/Policy%20briefing%20paper%20Gender%20Sensitive%20Police%20Reform%20in%20Post%20Conflict%20Societies.pdf . Accessed 10 May 2019

Verloo MMT (2001) Another velvet revolution? Gender mainstreaming and the politics of implementation. IWM Working paper (5).Vienna. https://repository.ubn.ru.nl/bitstream/handle/2066/129386/129386.pdf . Accessed 8 June 2020

Verveer M (2011) The political and economic power of women. Center for International Private Enterprise. http://www.state.gov/s/gwi/rls/rem/2011/167142.htm . Accessed 8 June 2020

Wagner DG, Berger J (1997) Gender and interpersonal task behaviors: status expectation accounts. Sociol Perspect 40:1–32

Young K (1987) Introduction. In: Sharma A (ed) Women in world religions. State University of New York Press, Albany, pp 1–36

Zawadzki M, Danube C, Shields S (2012) How to talk about gender inequity in the workplace: using WAGES as an experiential learning tool to reduce reactance and promote self-efficacy. Sex Roles 67(11–12):605–616. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-012-0181-z

Zobnina A (2009) Glossary of gender-related terms. Mediterranean Institute of Gender Studies. European Institute for Gender Equality. https://medinstgenderstudies.org/wp-content/uploads/Gender-Glossary-updated_final.pdf

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Gimnasio Femenino, Bogotá, Colombia

Juana Figueroa Vélez & Susana Vélez Ochoa

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Juana Figueroa Vélez .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

European School of Sustainability Science and Research, Hamburg University of Applied Sciences, Hamburg, Germany

Walter Leal Filho

Center for Neuroscience and Cell Biology, Institute for Interdisciplinary Research, University of Coimbra, Coimbra, Portugal

Anabela Marisa Azul

Faculty of Engineering and Architecture, The University of Passo Fundo, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Luciana Brandli

The University of Passo Fundo, Passo Fundo, Brazil

Amanda Lange Salvia

International Centre for Thriving, University of Chester, Chester, UK

Section Editor information

Council for Scientific and Industrial Research - Natural Resources and Environment, Johannesburg, South Africa

Julia Mambo

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this entry

Cite this entry.

Figueroa Vélez, J., Vélez Ochoa, S. (2021). Gender Sensitivity and Its Relation to Gender Equality. In: Leal Filho, W., Marisa Azul, A., Brandli, L., Lange Salvia, A., Wall, T. (eds) Gender Equality. Encyclopedia of the UN Sustainable Development Goals. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95687-9_46

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-95687-9_46

Published : 29 January 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-95686-2

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-95687-9

eBook Packages : Earth and Environmental Science Reference Module Physical and Materials Science Reference Module Earth and Environmental Sciences

Share this entry

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

A reflection on gender roles perception and inequality

- EDI-Priorities

- Project Period

- Athena SWAN

- University initiatives

- Characteristics

- Race Equality Charter

- Student and staff networks

- Staff guides

- Reasonable adjustments

- EDI data reporting

- Report an issue

- Useful links

- Email this Page

Introduction from Professor Sarah Sharples, Pro Vice-Chancellor for Equality, Diversity & Inclusion

I am delighted that this week’s EDI guest blog is written by Francesca Vinci School of Economics, who reflects on three powerful lectures on gender inequality delivered at the School by Professor Johanna Rickne of the Swedish Institute for Social Research at Stockholm University.

The debate on gender inequality has gained ever-growing attention in recent years, and this is true in academia, as well as industry and politics. Questions about what can be done to improve the representation of women in education as well as the work force are topical. As part of its efforts to contribute to this movement, the School of Economics had the pleasure to host three lectures on gender inequality, held by Professor Johanna Rickne (Swedish Institute for Social Research, Stockholm University and University of Nottingham). She shared insights from her own research and her expertise in the field, focusing on gender quotas, couple formation and harassment.

In the first lecture, she talked about the findings from research she conducted to assess the impact of the introduction of gender quotas in the local election process in Sweden. Prior to the change in policy, candidate lists on ballot papers were strongly influenced by party leaders and consistently had men ranking higher than women by a large margin, despite having access to information on individual’s competence, developed through years of participation in party activities.

The policy forced parties to modify the way they were forming candidate lists, by introducing a zipper quota, i.e. forcing them to alternate by gender throughout the list. Johanna and her co-authors found that the introduction of the quotas increased the overall competence of politicians elected, by increasing the quality of men selected, without affecting women’s. The authors interpret the results as evidence that mediocre men were pushed out because of the intervention and highlight that the previous status quo was the result of mediocre leaders choosing other mediocre individuals to increase the chances of their own survival.

In the first lecture, she talked about the findings from research she conducted to assess the impact of the introduction of gender quotas in the local election process in Sweden. Prior to the change in policy, candidate lists on ballot papers were strongly influenced by party leaders and consistently had men ranking higher than women by a large margin, despite having access to information on individual’s competence, developed through years of participation in party activities. The policy forced parties to modify the way they were forming candidate lists, by introducing a zipper quota, i.e. forcing them to alternate by gender throughout the list. Johanna and her co-authors found that the introduction of the quotas increased the overall competence of politicians elected, by increasing the quality of men selected, without affecting women’s. The authors interpret the results as evidence that mediocre men were pushed out because of the intervention and highlight that the previous status quo was the result of mediocre leaders choosing other mediocre individuals to increase the chances of their own survival.

In the second lecture, she discussed couple formation and women’s careers, focusing on the link between promotion to top jobs for women and the probability of divorce. She analysed Swedish data for local elections and found that women getting top jobs became more likely to divorce, whilst the result did not hold for men. Further analysis uncovered that the findings were driven by couple formation in which men were older, earned more to start with and had taken less parental leave, controlling for the couple’s ex-ante differences in background and earning potential. Johanna and her team interpreted these results as the result of a divergence in the expectations formed before the promotion within the couple. Although it is hard to draw definitive conclusions on something as intangible as expectations from quantitative analysis, this research seems to suggest that, at least for some couples, the expectations about traditional gender roles are still important for the equilibrium of a marriage. The professor also noted how a different study found that single MBA female students were less likely to report their true ambition in a context where their male peers would learn about them, as if their career-driven attitude would make them less desirable.

In the third lecture, Johanna tackled the role of harassment in perpetuating gender inequality and explained how this tends to increase with the share of the opposite sex in an occupation or workplace. A woman/man entering a male/female dominated environment breaks social norms, leading to retaliation through antagonistic behaviour. Interestingly, this suggests that men and women remain attached to some sort of identity categories, to some feeling of belonging they want to defend, and that leads them to hold on to the status quo. Moreover, as men tend to concentrate on highly paid specializations and women in lower wage sectors, this phenomenon has the effect of reinforcing segregation and income inequality.

These lectures were very insightful, they certainly had the effect of spurring debate across the department, and I hope beyond. I found myself talking in the common room with fellow PhD students as well as faculty members, as we all reflected on what we had learned and how we could use such knowledge. In my opinion, everything that was discussed in the lectures shared one common thread: the strong impact of gender role perceptions, affecting both men and women. Gender quotas were needed in Sweden because women were not selected for top ranking positions in local elections due to something other than their ability. They are also being introduced in many workplaces, as there is evidence that female candidates get overlooked due to being of childbearing age, for example. Beliefs about gender roles are also likely to affect behaviour: a woman might indeed leave her job when she becomes a mum if she feels compelled to do so by her family or her peers, and not just because of economic conditions and poor policy provisions. At the same time, a man who would like to stay at home to care for his child might feel the pressure to maintain his bread-winner role instead. Many couples conform with the traditional expectation that the man will be the provider whilst the woman will be the carer and they might crumble when gender roles get reversed, maybe because dynamics within the couple are challenged. In the lectures we also learned that men and women embrace their roles and professions and reject the outsiders as if they were threatening their identity. If gender norms and stereotypes become dogmas in people’s perception, men and women will feel lost and insecure outside them. In this case, the impact of policy efforts to level the playing field and combat bias would face the counteracting effect of gender rigid expectations and beliefs, even leading to more distortions maybe.

Achieving gender equality is a common goal, and policy makers as well as institutions such as universities can steer the ship in the right direction, but I believe we all have to put some hard work into this, by challenging our own beliefs of what gender roles are, and asking ourselves whether what we think we are supposed to do is what will make us happy.

All the Single Ladies: Job Promotions and the Durability of Marriage, (Olle Folke and Johanna Rickne) forthcoming, American Economic Journal: Applied Economics.

Gender Quotas and the Crisis of the Mediocre Man: Theory and Evidence from Sweden, (Johanna Rickne, Tim Besley, OllemFolke and Torsten Persson) American Economic Review 107(8): 2204-2242 (2017)

'Acting Wife:' Marriage Market Incentives and Labor Market Investments, (Leonardo Bursztyn, Thomas Fujiwara and Amanda Pallais) American Economic Review, 107(11): 3288-3319 (2017)

https://www.hrmagazine.co.uk/article-details/businesses-rejecting-maternity-age-candidates Francesca Vinci School of Economics

Monday 28 October 2019

Equality, Diversity and Inclusion

Trent Building University Park Campus Nottingham

Legal information

- Terms and conditions

- Posting rules

- Accessibility

- Freedom of information

- Charity gateway

- Cookie policy

Connect with the University of Nottingham through social media and our blogs .

- Child Participation

- End Violence Against Children

Reflecting on gender inequality and the disparity of rights

- Link for sharing

- Share on Facebook

- Share on LinkedIn

By Patricio Cuevas-Parra, World Vision International