Book Reviews

What this handout is about.

This handout will help you write a book review, a report or essay that offers a critical perspective on a text. It offers a process and suggests some strategies for writing book reviews.

What is a review?

A review is a critical evaluation of a text, event, object, or phenomenon. Reviews can consider books, articles, entire genres or fields of literature, architecture, art, fashion, restaurants, policies, exhibitions, performances, and many other forms. This handout will focus on book reviews. For a similar assignment, see our handout on literature reviews .

Above all, a review makes an argument. The most important element of a review is that it is a commentary, not merely a summary. It allows you to enter into dialogue and discussion with the work’s creator and with other audiences. You can offer agreement or disagreement and identify where you find the work exemplary or deficient in its knowledge, judgments, or organization. You should clearly state your opinion of the work in question, and that statement will probably resemble other types of academic writing, with a thesis statement, supporting body paragraphs, and a conclusion.

Typically, reviews are brief. In newspapers and academic journals, they rarely exceed 1000 words, although you may encounter lengthier assignments and extended commentaries. In either case, reviews need to be succinct. While they vary in tone, subject, and style, they share some common features:

- First, a review gives the reader a concise summary of the content. This includes a relevant description of the topic as well as its overall perspective, argument, or purpose.

- Second, and more importantly, a review offers a critical assessment of the content. This involves your reactions to the work under review: what strikes you as noteworthy, whether or not it was effective or persuasive, and how it enhanced your understanding of the issues at hand.

- Finally, in addition to analyzing the work, a review often suggests whether or not the audience would appreciate it.

Becoming an expert reviewer: three short examples

Reviewing can be a daunting task. Someone has asked for your opinion about something that you may feel unqualified to evaluate. Who are you to criticize Toni Morrison’s new book if you’ve never written a novel yourself, much less won a Nobel Prize? The point is that someone—a professor, a journal editor, peers in a study group—wants to know what you think about a particular work. You may not be (or feel like) an expert, but you need to pretend to be one for your particular audience. Nobody expects you to be the intellectual equal of the work’s creator, but your careful observations can provide you with the raw material to make reasoned judgments. Tactfully voicing agreement and disagreement, praise and criticism, is a valuable, challenging skill, and like many forms of writing, reviews require you to provide concrete evidence for your assertions.

Consider the following brief book review written for a history course on medieval Europe by a student who is fascinated with beer:

Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600, investigates how women used to brew and sell the majority of ale drunk in England. Historically, ale and beer (not milk, wine, or water) were important elements of the English diet. Ale brewing was low-skill and low status labor that was complimentary to women’s domestic responsibilities. In the early fifteenth century, brewers began to make ale with hops, and they called this new drink “beer.” This technique allowed brewers to produce their beverages at a lower cost and to sell it more easily, although women generally stopped brewing once the business became more profitable.

The student describes the subject of the book and provides an accurate summary of its contents. But the reader does not learn some key information expected from a review: the author’s argument, the student’s appraisal of the book and its argument, and whether or not the student would recommend the book. As a critical assessment, a book review should focus on opinions, not facts and details. Summary should be kept to a minimum, and specific details should serve to illustrate arguments.

Now consider a review of the same book written by a slightly more opinionated student:

Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600 was a colossal disappointment. I wanted to know about the rituals surrounding drinking in medieval England: the songs, the games, the parties. Bennett provided none of that information. I liked how the book showed ale and beer brewing as an economic activity, but the reader gets lost in the details of prices and wages. I was more interested in the private lives of the women brewsters. The book was divided into eight long chapters, and I can’t imagine why anyone would ever want to read it.

There’s no shortage of judgments in this review! But the student does not display a working knowledge of the book’s argument. The reader has a sense of what the student expected of the book, but no sense of what the author herself set out to prove. Although the student gives several reasons for the negative review, those examples do not clearly relate to each other as part of an overall evaluation—in other words, in support of a specific thesis. This review is indeed an assessment, but not a critical one.

Here is one final review of the same book:

One of feminism’s paradoxes—one that challenges many of its optimistic histories—is how patriarchy remains persistent over time. While Judith Bennett’s Ale, Beer, and Brewsters in England: Women’s Work in a Changing World, 1300-1600 recognizes medieval women as historical actors through their ale brewing, it also shows that female agency had its limits with the advent of beer. I had assumed that those limits were religious and political, but Bennett shows how a “patriarchal equilibrium” shut women out of economic life as well. Her analysis of women’s wages in ale and beer production proves that a change in women’s work does not equate to a change in working women’s status. Contemporary feminists and historians alike should read Bennett’s book and think twice when they crack open their next brewsky.

This student’s review avoids the problems of the previous two examples. It combines balanced opinion and concrete example, a critical assessment based on an explicitly stated rationale, and a recommendation to a potential audience. The reader gets a sense of what the book’s author intended to demonstrate. Moreover, the student refers to an argument about feminist history in general that places the book in a specific genre and that reaches out to a general audience. The example of analyzing wages illustrates an argument, the analysis engages significant intellectual debates, and the reasons for the overall positive review are plainly visible. The review offers criteria, opinions, and support with which the reader can agree or disagree.

Developing an assessment: before you write

There is no definitive method to writing a review, although some critical thinking about the work at hand is necessary before you actually begin writing. Thus, writing a review is a two-step process: developing an argument about the work under consideration, and making that argument as you write an organized and well-supported draft. See our handout on argument .

What follows is a series of questions to focus your thinking as you dig into the work at hand. While the questions specifically consider book reviews, you can easily transpose them to an analysis of performances, exhibitions, and other review subjects. Don’t feel obligated to address each of the questions; some will be more relevant than others to the book in question.

- What is the thesis—or main argument—of the book? If the author wanted you to get one idea from the book, what would it be? How does it compare or contrast to the world you know? What has the book accomplished?

- What exactly is the subject or topic of the book? Does the author cover the subject adequately? Does the author cover all aspects of the subject in a balanced fashion? What is the approach to the subject (topical, analytical, chronological, descriptive)?

- How does the author support their argument? What evidence do they use to prove their point? Do you find that evidence convincing? Why or why not? Does any of the author’s information (or conclusions) conflict with other books you’ve read, courses you’ve taken or just previous assumptions you had of the subject?

- How does the author structure their argument? What are the parts that make up the whole? Does the argument make sense? Does it persuade you? Why or why not?

- How has this book helped you understand the subject? Would you recommend the book to your reader?

Beyond the internal workings of the book, you may also consider some information about the author and the circumstances of the text’s production:

- Who is the author? Nationality, political persuasion, training, intellectual interests, personal history, and historical context may provide crucial details about how a work takes shape. Does it matter, for example, that the biographer was the subject’s best friend? What difference would it make if the author participated in the events they write about?

- What is the book’s genre? Out of what field does it emerge? Does it conform to or depart from the conventions of its genre? These questions can provide a historical or literary standard on which to base your evaluations. If you are reviewing the first book ever written on the subject, it will be important for your readers to know. Keep in mind, though, that naming “firsts”—alongside naming “bests” and “onlys”—can be a risky business unless you’re absolutely certain.

Writing the review

Once you have made your observations and assessments of the work under review, carefully survey your notes and attempt to unify your impressions into a statement that will describe the purpose or thesis of your review. Check out our handout on thesis statements . Then, outline the arguments that support your thesis.

Your arguments should develop the thesis in a logical manner. That logic, unlike more standard academic writing, may initially emphasize the author’s argument while you develop your own in the course of the review. The relative emphasis depends on the nature of the review: if readers may be more interested in the work itself, you may want to make the work and the author more prominent; if you want the review to be about your perspective and opinions, then you may structure the review to privilege your observations over (but never separate from) those of the work under review. What follows is just one of many ways to organize a review.

Introduction

Since most reviews are brief, many writers begin with a catchy quip or anecdote that succinctly delivers their argument. But you can introduce your review differently depending on the argument and audience. The Writing Center’s handout on introductions can help you find an approach that works. In general, you should include:

- The name of the author and the book title and the main theme.

- Relevant details about who the author is and where they stand in the genre or field of inquiry. You could also link the title to the subject to show how the title explains the subject matter.

- The context of the book and/or your review. Placing your review in a framework that makes sense to your audience alerts readers to your “take” on the book. Perhaps you want to situate a book about the Cuban revolution in the context of Cold War rivalries between the United States and the Soviet Union. Another reviewer might want to consider the book in the framework of Latin American social movements. Your choice of context informs your argument.

- The thesis of the book. If you are reviewing fiction, this may be difficult since novels, plays, and short stories rarely have explicit arguments. But identifying the book’s particular novelty, angle, or originality allows you to show what specific contribution the piece is trying to make.

- Your thesis about the book.

Summary of content

This should be brief, as analysis takes priority. In the course of making your assessment, you’ll hopefully be backing up your assertions with concrete evidence from the book, so some summary will be dispersed throughout other parts of the review.

The necessary amount of summary also depends on your audience. Graduate students, beware! If you are writing book reviews for colleagues—to prepare for comprehensive exams, for example—you may want to devote more attention to summarizing the book’s contents. If, on the other hand, your audience has already read the book—such as a class assignment on the same work—you may have more liberty to explore more subtle points and to emphasize your own argument. See our handout on summary for more tips.

Analysis and evaluation of the book

Your analysis and evaluation should be organized into paragraphs that deal with single aspects of your argument. This arrangement can be challenging when your purpose is to consider the book as a whole, but it can help you differentiate elements of your criticism and pair assertions with evidence more clearly. You do not necessarily need to work chronologically through the book as you discuss it. Given the argument you want to make, you can organize your paragraphs more usefully by themes, methods, or other elements of the book. If you find it useful to include comparisons to other books, keep them brief so that the book under review remains in the spotlight. Avoid excessive quotation and give a specific page reference in parentheses when you do quote. Remember that you can state many of the author’s points in your own words.

Sum up or restate your thesis or make the final judgment regarding the book. You should not introduce new evidence for your argument in the conclusion. You can, however, introduce new ideas that go beyond the book if they extend the logic of your own thesis. This paragraph needs to balance the book’s strengths and weaknesses in order to unify your evaluation. Did the body of your review have three negative paragraphs and one favorable one? What do they all add up to? The Writing Center’s handout on conclusions can help you make a final assessment.

Finally, a few general considerations:

- Review the book in front of you, not the book you wish the author had written. You can and should point out shortcomings or failures, but don’t criticize the book for not being something it was never intended to be.

- With any luck, the author of the book worked hard to find the right words to express her ideas. You should attempt to do the same. Precise language allows you to control the tone of your review.

- Never hesitate to challenge an assumption, approach, or argument. Be sure, however, to cite specific examples to back up your assertions carefully.

- Try to present a balanced argument about the value of the book for its audience. You’re entitled—and sometimes obligated—to voice strong agreement or disagreement. But keep in mind that a bad book takes as long to write as a good one, and every author deserves fair treatment. Harsh judgments are difficult to prove and can give readers the sense that you were unfair in your assessment.

- A great place to learn about book reviews is to look at examples. The New York Times Sunday Book Review and The New York Review of Books can show you how professional writers review books.

Works consulted

We consulted these works while writing this handout. This is not a comprehensive list of resources on the handout’s topic, and we encourage you to do your own research to find additional publications. Please do not use this list as a model for the format of your own reference list, as it may not match the citation style you are using. For guidance on formatting citations, please see the UNC Libraries citation tutorial . We revise these tips periodically and welcome feedback.

Drewry, John. 1974. Writing Book Reviews. Boston: Greenwood Press.

Hoge, James. 1987. Literary Reviewing. Charlottesville: University Virginia of Press.

Sova, Dawn, and Harry Teitelbaum. 2002. How to Write Book Reports , 4th ed. Lawrenceville, NY: Thomson/Arco.

Walford, A.J. 1986. Reviews and Reviewing: A Guide. Phoenix: Oryx Press.

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

- Link to facebook

- Link to linkedin

- Link to twitter

- Link to youtube

- Writing Tips

How to Write an Academic Book Review

4-minute read

- 13th September 2019

For researchers and postgraduates , writing a book review is a relatively easy way to get published. It’s also a good way to refine your academic writing skills and learn the publishing process. But how do you write a good academic book review? We have a few tips to share.

1. Finding a Book to Review

Before you can write a book review, you need a suitable book to review. Typically, there are two main ways to find one:

- Look to see which books journal publishers are seeking reviews for.

- Find a book that interests you and pitch it to publishers.

The first approach works by finding a journal in your field that is soliciting reviews. This information may be available on the journal’s website (e.g., on a page titled “Books for Review”). However, you can also email the editor to ask if there are book review opportunities available.

Alternatively, you can find a book you want to review and pitch it to journal editors. If you want to take this approach, pick a book that:

- Is about a topic or subject area that you know well.

- Has been published recently, or at least in the last 2–3 years.

- Was published by a reputable publisher (e.g., a university printing press).

You can then pitch the review to a journal that covers your chosen subject.

Some publishers will even give reviewers access to new books. Springer, for example, has a scheme where reviewers can access books online and receive a print copy once a review is published. So this is always worth checking.

2. Follow the Style Guide

Once you know the journal you want to write for, look for the publisher’s style guide. This might be called the “Author Instructions” or “Review Guidelines,” but it should be available somewhere on the publisher’s website. If it is not obviously available, consider checking with the editor.

Find this useful?

Subscribe to our newsletter and get writing tips from our editors straight to your inbox.

When you have found the style guide, follow its instructions carefully. It should provide information on everything from writing style and the word count to submitting your review, making the process much simpler.

3. Don’t Make It About You!

You’d be surprised how often people begin by summarizing the book they’re reviewing, but then abandon it in favor of explaining their own ideas about the subject matter. As such, one important tip when reviewing an academic book is to actually review the book , not just the subject matter.

This isn’t to say that you can’t offer your own thoughts on the issues discussed, especially if they’re relevant to what the author has argued. But remember that people read reviews to find out about the book being reviewed, so this should always be your focus.

4. Questions to Answer in a Book Review

Finally, while the content of a review will depend on the book, there are a few questions every good book review should answer. These include:

- What is the book about? Does it cover the topic adequately? What does the author argue? Ideally, you will summarize the argument early on.

- Who is the author/editor? What is their field of expertise? How does this book relate to their past work? You might also want to mention relevant biographical details about the author, if there are any.

- How does the author support their argument? Do they provide convincing evidence? Do they engage with counterarguments? Try to find at least one strength (i.e., something the book does well) and one weakness (i.e., something that could be stronger) to write about.

- As a whole, has the book helped you understand the subject? Who would you recommend it to? This will be the concluding section of your review.

If you can cover all these points, you should end up with a strong book review. All you need then is to have it proofread by the professionals .

Share this article:

Post A New Comment

Got content that needs a quick turnaround? Let us polish your work. Explore our editorial business services.

3-minute read

What Is a Content Editor?

Are you interested in learning more about the role of a content editor and the...

The Benefits of Using an Online Proofreading Service

Proofreading is important to ensure your writing is clear and concise for your readers. Whether...

2-minute read

6 Online AI Presentation Maker Tools

Creating presentations can be time-consuming and frustrating. Trying to construct a visually appealing and informative...

What Is Market Research?

No matter your industry, conducting market research helps you keep up to date with shifting...

8 Press Release Distribution Services for Your Business

In a world where you need to stand out, press releases are key to being...

How to Get a Patent

In the United States, the US Patent and Trademarks Office issues patents. In the United...

Make sure your writing is the best it can be with our expert English proofreading and editing.

Organizing Your Social Sciences Research Assignments

- Annotated Bibliography

- Analyzing a Scholarly Journal Article

- Group Presentations

- Dealing with Nervousness

- Using Visual Aids

- Grading Someone Else's Paper

- Types of Structured Group Activities

- Group Project Survival Skills

- Leading a Class Discussion

- Multiple Book Review Essay

- Reviewing Collected Works

- Writing a Case Analysis Paper

- Writing a Case Study

- About Informed Consent

- Writing Field Notes

- Writing a Policy Memo

- Writing a Reflective Paper

- Writing a Research Proposal

- Generative AI and Writing

- Acknowledgments

A book review is a thorough description, critical analysis, and/or evaluation of the quality, meaning, and significance of a book, often written in relation to prior research on the topic. Reviews generally range from 500-2000 words, but may be longer or shorter depends on several factors: the length and complexity of the book being reviewed, the overall purpose of the review, and whether the review examines two or more books that focus on the same topic. Professors assign book reviews as practice in carefully analyzing complex scholarly texts and to assess your ability to effectively synthesize research so that you reach an informed perspective about the topic being covered.

There are two general approaches to reviewing a book:

- Descriptive review: Presents the content and structure of a book as objectively as possible, describing essential information about a book's purpose and authority. This is done by stating the perceived aims and purposes of the study, often incorporating passages quoted from the text that highlight key elements of the work. Additionally, there may be some indication of the reading level and anticipated audience.

- Critical review: Describes and evaluates the book in relation to accepted literary and historical standards and supports this evaluation with evidence from the text and, in most cases, in contrast to and in comparison with the research of others. It should include a statement about what the author has tried to do, evaluates how well you believe the author has succeeded in meeting the objectives of the study, and presents evidence to support this assessment. For most course assignments, your professor will want you to write this type of review.

Book Reviews. Writing Center. University of New Hampshire; Book Reviews: How to Write a Book Review. Writing and Style Guides. Libraries. Dalhousie University; Kindle, Peter A. "Teaching Students to Write Book Reviews." Contemporary Rural Social Work 7 (2015): 135-141; Erwin, R. W. “Reviewing Books for Scholarly Journals.” In Writing and Publishing for Academic Authors . Joseph M. Moxley and Todd Taylor. 2 nd edition. (Lanham, MD: Rowan and Littlefield, 1997), pp. 83-90.

How to Approach Writing Your Review

NOTE: Since most course assignments require that you write a critical rather than descriptive book review, the following information about preparing to write and developing the structure and style of reviews focuses on this approach.

I. Common Features

While book reviews vary in tone, subject, and style, they share some common features. These include:

- A review gives the reader a concise summary of the content . This includes a description of the research topic and scope of analysis as well as an overview of the book's overall perspective, argument, and purpose.

- A review offers a critical assessment of the content in relation to other studies on the same topic . This involves documenting your reactions to the work under review--what strikes you as noteworthy or important, whether or not the arguments made by the author(s) were effective or persuasive, and how the work enhanced your understanding of the research problem under investigation.

- In addition to analyzing a book's strengths and weaknesses, a scholarly review often recommends whether or not readers would value the work for its authenticity and overall quality . This measure of quality includes both the author's ideas and arguments and covers practical issues, such as, readability and language, organization and layout, indexing, and, if needed, the use of non-textual elements .

To maintain your focus, always keep in mind that most assignments ask you to discuss a book's treatment of its topic, not the topic itself . Your key sentences should say, "This book shows...,” "The study demonstrates...," or “The author argues...," rather than "This happened...” or “This is the case....”

II. Developing a Critical Assessment Strategy

There is no definitive methodological approach to writing a book review in the social sciences, although it is necessary that you think critically about the research problem under investigation before you begin to write. Therefore, writing a book review is a three-step process: 1) carefully taking notes as you read the text; 2) developing an argument about the value of the work under consideration; and, 3) clearly articulating that argument as you write an organized and well-supported assessment of the work.

A useful strategy in preparing to write a review is to list a set of questions that should be answered as you read the book [remember to note the page numbers so you can refer back to the text!]. The specific questions to ask yourself will depend upon the type of book you are reviewing. For example, a book that is presenting original research about a topic may require a different set of questions to ask yourself than a work where the author is offering a personal critique of an existing policy or issue.

Here are some sample questions that can help you think critically about the book:

- Thesis or Argument . What is the central thesis—or main argument—of the book? If the author wanted you to get one main idea from the book, what would it be? How does it compare or contrast to the world that you know or have experienced? What has the book accomplished? Is the argument clearly stated and does the research support this?

- Topic . What exactly is the subject or topic of the book? Is it clearly articulated? Does the author cover the subject adequately? Does the author cover all aspects of the subject in a balanced fashion? Can you detect any biases? What type of approach has the author adopted to explore the research problem [e.g., topical, analytical, chronological, descriptive]?

- Evidence . How does the author support their argument? What evidence does the author use to prove their point? Is the evidence based on an appropriate application of the method chosen to gather information? Do you find that evidence convincing? Why or why not? Does any of the author's information [or conclusions] conflict with other books you've read, courses you've taken, or just previous assumptions you had about the research problem?

- Structure . How does the author structure their argument? Does it follow a logical order of analysis? What are the parts that make up the whole? Does the argument make sense to you? Does it persuade you? Why or why not?

- Take-aways . How has this book helped you understand the research problem? Would you recommend the book to others? Why or why not?

Beyond the content of the book, you may also consider some information about the author and the general presentation of information. Question to ask may include:

- The Author: Who is the author? The nationality, political persuasion, education, intellectual interests, personal history, and historical context may provide crucial details about how a work takes shape. Does it matter, for example, that the author is affiliated with a particular organization? What difference would it make if the author participated in the events they wrote about? What other topics has the author written about? Does this work build on prior research or does it represent a new or unique area of research?

- The Presentation: What is the book's genre? Out of what discipline does it emerge? Does it conform to or depart from the conventions of its genre? These questions can provide a historical or other contextual standard upon which to base your evaluations. If you are reviewing the first book ever written on the subject, it will be important for your readers to know this. Keep in mind, though, that declarative statements about being the “first,” the "best," or the "only" book of its kind can be a risky unless you're absolutely certain because your professor [presumably] has a much better understanding of the overall research literature.

NOTE: Most critical book reviews examine a topic in relation to prior research. A good strategy for identifying this prior research is to examine sources the author(s) cited in the chapters introducing the research problem and, of course, any review of the literature. However, you should not assume that the author's references to prior research is authoritative or complete. If any works related to the topic have been excluded, your assessment of the book should note this . Be sure to consult with a librarian to ensure that any additional studies are located beyond what has been cited by the author(s).

Book Reviews. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Book Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Hartley, James. "Reading and Writing Book Reviews Across the Disciplines." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57 (July 2006): 1194–1207; Motta-Roth, D. “Discourse Analysis and Academic Book Reviews: A Study of Text and Disciplinary Cultures.” In Genre Studies in English for Academic Purposes . Fortanet Gómez, Inmaculada et al., editors. (Castellò de la Plana: Publicacions de la Universitat Jaume I, 1998), pp. 29-45. Writing a Book Review. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Book Reviews. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University; Suárez, Lorena and Ana I. Moreno. “The Rhetorical Structure of Academic Journal Book Reviews: A Cross-linguistic and Cross-disciplinary Approach .” In Asociación Europea de Lenguas para Fines Específicos, María del Carmen Pérez Llantada Auría, Ramón Plo Alastrué, and Claus Peter Neumann. Actas del V Congreso Internacional AELFE/Proceedings of the 5th International AELFE Conference . Zaragoza: Universidad de Zaragoza, 2006.

Structure and Writing Style

I. Bibliographic Information

Bibliographic information refers to the essential elements of a work if you were to cite it in a paper [i.e., author, title, date of publication, etc.]. Provide the essential information about the book using the writing style [e.g., APA, MLA, Chicago] preferred by your professor or used by the discipline of your major . Depending on how your professor wants you to organize your review, the bibliographic information represents the heading of your review. In general, it would look like this:

[Complete title of book. Author or authors. Place of publication. Publisher. Date of publication. Number of pages before first chapter, often in Roman numerals. Total number of pages]. The Whites of Their Eyes: The Tea Party's Revolution and the Battle over American History . By Jill Lepore. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2010. xii, 207 pp.)

Reviewed by [your full name].

II. Scope/Purpose/Content

Begin your review by telling the reader not only the overarching concern of the book in its entirety [the subject area] but also what the author's particular point of view is on that subject [the thesis statement]. If you cannot find an adequate statement in the author's own words or if you find that the thesis statement is not well-developed, then you will have to compose your own introductory thesis statement that does cover all the material. This statement should be no more than one paragraph and must be succinctly stated, accurate, and unbiased.

If you find it difficult to discern the overall aims and objectives of the book [and, be sure to point this out in your review if you determine that this is a deficiency], you may arrive at an understanding of the book's overall purpose by assessing the following:

- Scan the table of contents because it can help you understand how the book was organized and will aid in determining the author's main ideas and how they were developed [e.g., chronologically, topically, historically, etc.].

- Why did the author write on this subject rather than on some other subject?

- From what point of view is the work written?

- Was the author trying to give information, to explain something technical, or to convince the reader of a belief’s validity by dramatizing it in action?

- What is the general field or genre, and how does the book fit into it? If necessary, review related literature from other books and journal articles to familiarize yourself with the field.

- Who is the intended audience?

- What is the author's style? Is it formal or informal? You can evaluate the quality of the writing style by noting some of the following standards: coherence, clarity, originality, forcefulness, accurate use of technical words, conciseness, fullness of development, and fluidity [i.e., quality of the narrative flow].

- How did the book affect you? Were there any prior assumptions you had about the subject that were changed, abandoned, or reinforced after reading the book? How is the book related to your own personal beliefs or assumptions? What personal experiences have you had related to the subject that affirm or challenge underlying assumptions?

- How well has the book achieved the goal(s) set forth in the preface, introduction, and/or foreword?

- Would you recommend this book to others? Why or why not?

III. Note the Method

Support your remarks with specific references to text and quotations that help to illustrate the literary method used to state the research problem, describe the research design, and analyze the findings. In general, authors tend to use the following literary methods, exclusively or in combination.

- Description : The author depicts scenes and events by giving specific details that appeal to the five senses, or to the reader’s imagination. The description presents background and setting. Its primary purpose is to help the reader realize, through as many details as possible, the way persons, places, and things are situated within the phenomenon being described.

- Narration : The author tells the story of a series of events, usually thematically or in chronological order. In general, the emphasis in scholarly books is on narration of the events. Narration tells what has happened and, in some cases, using this method to forecast what could happen in the future. Its primary purpose is to draw the reader into a story and create a contextual framework for understanding the research problem.

- Exposition : The author uses explanation and analysis to present a subject or to clarify an idea. Exposition presents the facts about a subject or an issue clearly and as impartially as possible. Its primary purpose is to describe and explain, to document for the historical record an event or phenomenon.

- Argument : The author uses techniques of persuasion to establish understanding of a particular truth, often in the form of addressing a research question, or to convince the reader of its falsity. The overall aim is to persuade the reader to believe something and perhaps to act on that belief. Argument takes sides on an issue and aims to convince the reader that the author's position is valid, logical, and/or reasonable.

IV. Critically Evaluate the Contents

Critical comments should form the bulk of your book review . State whether or not you feel the author's treatment of the subject matter is appropriate for the intended audience. Ask yourself:

- Has the purpose of the book been achieved?

- What contributions does the book make to the field?

- Is the treatment of the subject matter objective or at least balanced in describing all sides of a debate?

- Are there facts and evidence that have been omitted?

- What kinds of data, if any, are used to support the author's thesis statement?

- Can the same data be interpreted to explain alternate outcomes?

- Is the writing style clear and effective?

- Does the book raise important or provocative issues or topics for discussion?

- Does the book bring attention to the need for further research?

- What has been left out?

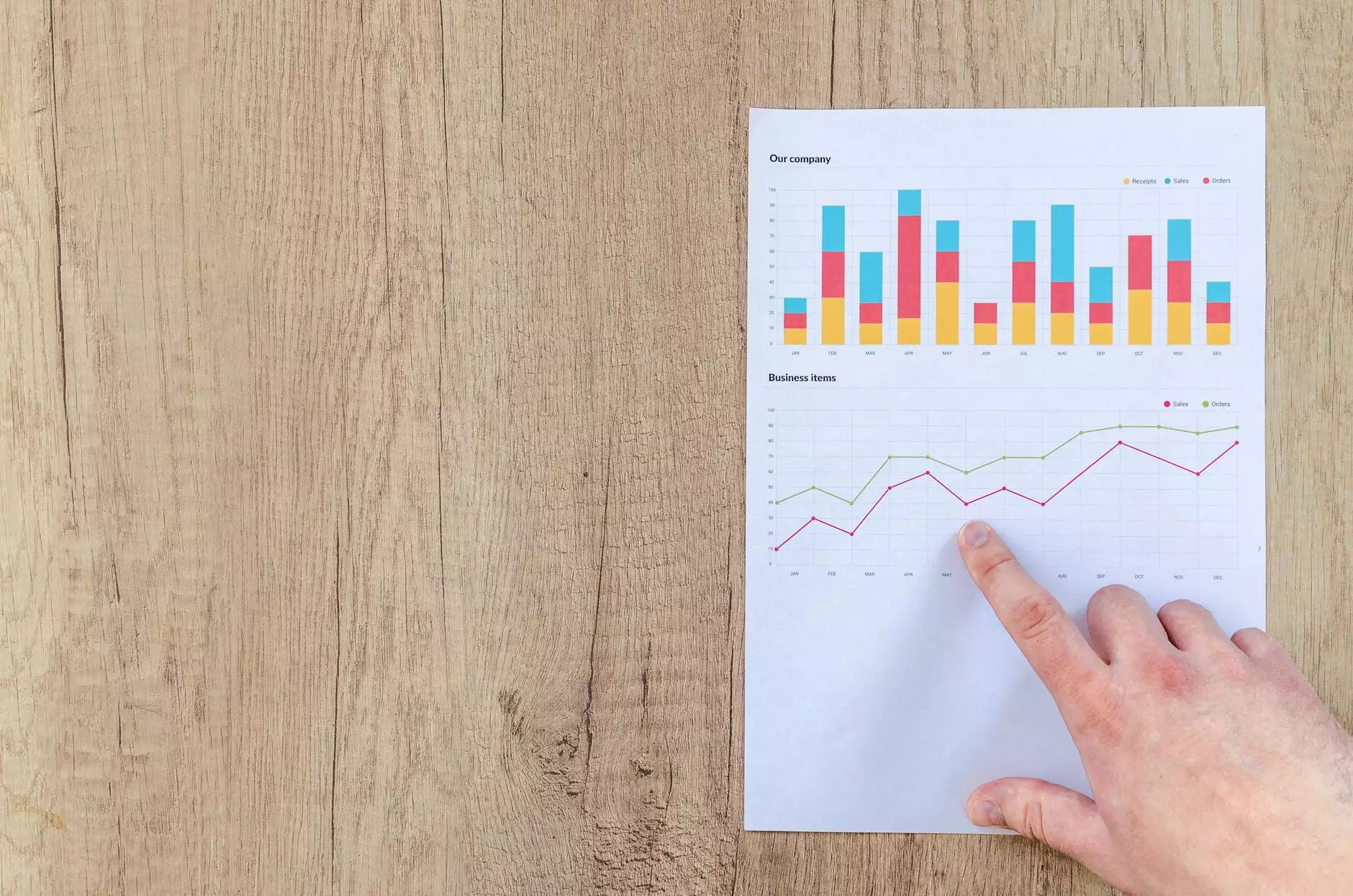

Support your evaluation with evidence from the text and, when possible, state the book's quality in relation to other scholarly sources. If relevant, note of the book's format, such as, layout, binding, typography, etc. Are there tables, charts, maps, illustrations, text boxes, photographs, or other non-textual elements? Do they aid in understanding the text? Describing this is particularly important in books that contain a lot of non-textual elements.

NOTE: It is important to carefully distinguish your views from those of the author so as not to confuse your reader. Be clear when you are describing an author's point of view versus expressing your own.

V. Examine the Front Matter and Back Matter

Front matter refers to any content before the first chapter of the book. Back matter refers to any information included after the final chapter of the book . Front matter is most often numbered separately from the rest of the text in lower case Roman numerals [i.e. i - xi ]. Critical commentary about front or back matter is generally only necessary if you believe there is something that diminishes the overall quality of the work [e.g., the indexing is poor] or there is something that is particularly helpful in understanding the book's contents [e.g., foreword places the book in an important context].

Front matter that may be considered for evaluation when reviewing its overall quality:

- Table of contents -- is it clear? Is it detailed or general? Does it reflect the true contents of the book? Does it help in understanding a logical sequence of content?

- Author biography -- also found as back matter, the biography of author(s) can be useful in determining the authority of the writer and whether the book builds on prior research or represents new research. In scholarly reviews, noting the author's affiliation and prior publications can be a factor in helping the reader determine the overall validity of the work [i.e., are they associated with a research center devoted to studying the problem under investigation].

- Foreword -- the purpose of a foreword is to introduce the reader to the author and the content of the book, and to help establish credibility for both. A foreword may not contribute any additional information about the book's subject matter, but rather, serves as a means of validating the book's existence. In these cases, the foreword is often written by a leading scholar or expert who endorses the book's contributions to advancing research about the topic. Later editions of a book sometimes have a new foreword prepended [appearing before an older foreword, if there was one], which may be included to explain how the latest edition differs from previous editions. These are most often written by the author.

- Acknowledgements -- scholarly studies in the social sciences often take many years to write, so authors frequently acknowledge the help and support of others in getting their research published. This can be as innocuous as acknowledging the author's family or the publisher. However, an author may acknowledge prominent scholars or subject experts, staff at key research centers, people who curate important archival collections, or organizations that funded the research. In these particular cases, it may be worth noting these sources of support in your review, particularly if the funding organization is biased or its mission is to promote a particular agenda.

- Preface -- generally describes the genesis, purpose, limitations, and scope of the book and may include acknowledgments of indebtedness to people who have helped the author complete the study. Is the preface helpful in understanding the study? Does it provide an effective framework for understanding what's to follow?

- Chronology -- also may be found as back matter, a chronology is generally included to highlight key events related to the subject of the book. Do the entries contribute to the overall work? Is it detailed or very general?

- List of non-textual elements -- a book that contains numerous charts, photographs, maps, tables, etc. will often list these items after the table of contents in the order that they appear in the text. Is this useful?

Back matter that may be considered for evaluation when reviewing its overall quality:

- Afterword -- this is a short, reflective piece written by the author that takes the form of a concluding section, final commentary, or closing statement. It is worth mentioning in a review if it contributes information about the purpose of the book, gives a call to action, summarizes key recommendations or next steps, or asks the reader to consider key points made in the book.

- Appendix -- is the supplementary material in the appendix or appendices well organized? Do they relate to the contents or appear superfluous? Does it contain any essential information that would have been more appropriately integrated into the text?

- Index -- are there separate indexes for names and subjects or one integrated index. Is the indexing thorough and accurate? Are elements used, such as, bold or italic fonts to help identify specific places in the book? Does the index include "see also" references to direct you to related topics?

- Glossary of Terms -- are the definitions clearly written? Is the glossary comprehensive or are there key terms missing? Are any terms or concepts mentioned in the text not included that should have been?

- Endnotes -- examine any endnotes as you read from chapter to chapter. Do they provide important additional information? Do they clarify or extend points made in the body of the text? Should any notes have been better integrated into the text rather than separated? Do the same if the author uses footnotes.

- Bibliography/References/Further Readings -- review any bibliography, list of references to sources, and/or further readings the author may have included. What kinds of sources appear [e.g., primary or secondary, recent or old, scholarly or popular, etc.]? How does the author make use of them? Be sure to note important omissions of sources that you believe should have been utilized, including important digital resources or archival collections.

VI. Summarize and Comment

State your general conclusions briefly and succinctly. Pay particular attention to the author's concluding chapter and/or afterword. Is the summary convincing? List the principal topics, and briefly summarize the author’s ideas about these topics, main points, and conclusions. If appropriate and to help clarify your overall evaluation, use specific references to text and quotations to support your statements. If your thesis has been well argued, the conclusion should follow naturally. It can include a final assessment or simply restate your thesis. Do not introduce new information in the conclusion. If you've compared the book to any other works or used other sources in writing the review, be sure to cite them at the end of your book review in the same writing style as your bibliographic heading of the book.

Book Reviews. Writing@CSU. Colorado State University; Book Reviews. The Writing Center. University of North Carolina; Gastel, Barbara. "Special Books Section: A Strategy for Reviewing Books for Journals." BioScience 41 (October 1991): 635-637; Hartley, James. "Reading and Writing Book Reviews Across the Disciplines." Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 57 (July 2006): 1194–1207; Lee, Alexander D., Bart N. Green, Claire D. Johnson, and Julie Nyquist. "How to Write a Scholarly Book Review for Publication in a Peer-reviewed Journal: A Review of the Literature." Journal of Chiropractic Education 24 (2010): 57-69; Nicolaisen, Jeppe. "The Scholarliness of Published Peer Reviews: A Bibliometric Study of Book Reviews in Selected Social Science Fields." Research Evaluation 11 (2002): 129-140;.Procter, Margaret. The Book Review or Article Critique. The Lab Report. University College Writing Centre. University of Toronto; Reading a Book to Review It. The Writer’s Handbook. Writing Center. University of Wisconsin, Madison; Scarnecchia, David L. "Writing Book Reviews for the Journal Of Range Management and Rangelands." Rangeland Ecology and Management 57 (2004): 418-421; Simon, Linda. "The Pleasures of Book Reviewing." Journal of Scholarly Publishing 27 (1996): 240-241; Writing a Book Review. The Writing Lab and The OWL. Purdue University; Writing Book Reviews. Writing Tutorial Services, Center for Innovative Teaching and Learning. Indiana University.

Writing Tip

Always Read the Foreword and/or the Preface

If they are included in the front matter, a good place for understanding a book's overall purpose, organization, contributions to further understanding of the research problem, and relationship to other studies is to read the preface and the foreword. The foreword may be written by someone other than the author or editor and can be a person who is famous or who has name recognition within the discipline. A foreword is often included to add credibility to the work.

The preface is usually an introductory essay written by the author or editor. It is intended to describe the book's overall purpose, arrangement, scope, and overall contributions to the literature. When reviewing the book, it can be useful to critically evaluate whether the goals set forth in the foreword and/or preface were actually achieved. At the very least, they can establish a foundation for understanding a study's scope and purpose as well as its significance in contributing new knowledge.

Distinguishing between a Foreword, a Preface, and an Introduction . Book Creation Learning Center. Greenleaf Book Group, 2019.

Locating Book Reviews

There are several databases the USC Libraries subscribes to that include the full-text or citations to book reviews. Short, descriptive reviews can also be found at book-related online sites such as Amazon , although it's not always obvious who has written them and may actually be created by the publisher. The following databases provide comprehensive access to scholarly, full-text book reviews:

- ProQuest [1983-present]

- Book Review Digest Retrospective [1905-1982]

Some Language for Evaluating Texts

It can be challenging to find the proper vocabulary from which to discuss and evaluate a book. Here is a list of some active verbs for referring to texts and ideas that you might find useful:

- account for

- demonstrate

- distinguish

- investigate

Examples of usage

- "The evidence indicates that..."

- "This work assesses the effect of..."

- "The author identifies three key reasons for..."

- "This book questions the view that..."

- "This work challenges assumptions about...."

Paquot, Magali. Academic Keyword List. Centre for English Corpus Linguistics. Université Catholique de Louvain.

- << Previous: Leading a Class Discussion

- Next: Multiple Book Review Essay >>

- Last Updated: Mar 6, 2024 1:00 PM

- URL: https://libguides.usc.edu/writingguide/assignments

How to Write Academic Book Review – a Complete Guide

Introduction

Welcome to The Knowledge Nest, your go-to resource for comprehensive guides on various academic subjects. In this guide, we will provide you with all the necessary information and steps to write an outstanding academic book review.

Why Write an Academic Book Review?

Before diving into the details, let's first understand why writing an academic book review is important. A book review allows you to critically analyze and assess the merit of a particular book. It not only helps you sharpen your analytical skills but also provides an opportunity to contribute to the academic community by sharing your insights and recommendations.

Step 1: Choose the Right Book

The first step in writing a high-quality academic book review is to select the right book. Identify a book that aligns with your area of interest or the subject you are studying. Ensure that the book is relevant, reputable, and has a substantial impact on the field you wish to explore.

Step 2: Read the Book Thoroughly

Once you have chosen the book, it's time to engage in a comprehensive reading. Read the book attentively, making notes of key arguments, main themes, and any significant evidence presented by the author. Pay close attention to the author's writing style, methodology, and the overall structure of the book.

Step 3: Analyze and Evaluate

After reading the book, critically analyze and evaluate its strengths and weaknesses. Consider the author's arguments, their supporting evidence, and how effectively they present their ideas. Assess the book's contribution to the field, its relevance, and its potential impact on future scholarship.

Step 4: Organize Your Thoughts

Before starting to write the actual review, it's essential to organize your thoughts and create an outline. Identify the main points and arguments you wish to address in your review. This will help you maintain a logical flow and structure in your writing.

Step 5: Start Writing

Now that you have a clear outline, it's time to put pen to paper and start writing your academic book review. Begin with a concise introduction that provides an overview of the book and its context. Clearly state your thesis or main argument regarding the book's strengths and weaknesses.

Step 6: Support Your Claims

As you progress with your review, make sure to back up your claims and arguments with supporting evidence from the book. Quote relevant passages, cite significant examples, and provide specific details to substantiate your viewpoints. Remember to analyze and critique the book's content objectively and fairly.

Step 7: Summarize and Conclude

In the final section of your review, summarize your main points and offer a concise conclusion. Highlight the book's significance and evaluate its contribution to the field. You can also provide recommendations for further research or suggest potential audiences who would benefit from reading the book.

Step 8: Revise and Refine

After completing your initial draft, take the time to revise and refine your review. Check for grammatical errors, ensure clarity in your arguments, and strengthen the overall structure of your writing. Edit ruthlessly to make your review concise, coherent, and compelling.

Step 9: Finalize and Submit

Once you are satisfied with the quality of your review, make any final adjustments and proofread carefully. Ensure that your content adheres to any specific submission guidelines provided by your academic institution or the platform where you plan to publish your review. Submit your review with confidence!

Writing an academic book review is a challenging task that requires careful analysis, critical thinking, and effective communication skills. By following the steps outlined in this guide, you will be well-equipped to craft a comprehensive and insightful book review that contributes to the scholarly discourse in your field.

About The Knowledge Nest

The Knowledge Nest is a community-driven platform dedicated to providing valuable educational resources and comprehensive guides across various academic disciplines. Our mission is to empower learners by sharing knowledge and enabling them to excel in their educational endeavors.

Tags: Academic Book Review, How to Write Academic Book Review, Writing Book Reviews, Writing Tips, The Knowledge Nest

Ph.D. Dissertation Help on Management

How to Start a Book Report - Studybay

An Overview of the Major Ethical Issues in Information Systems

All About Nike Shoes Manufacturing Process

Architecture Thesis Examples

Tips for Writing a Biography Book Report - Studybay

Economics Research Paper Examples & Study Documents

Dissertation Data Analysis Help - Studybay

Geography Homework Help for Stress-Free Studying - The Knowledge Nest

College Homework Help for Students - Studybay

How to Write an Academic Book Review

Learning objectives.

Upon completion of this comprehensive and engaging course, you will be able to:

- Identify the primary goals of an academic book review

- Describe the 5 key benefits of writing an academic book review

- List the 6 main audiences of an academic book review

- Apply strategies for deciding which academic book to review

- Choose the peer-reviewed journal with the best goodness-of-fit for your academic book review

- Successfully write the 5 main sections of an academic book review

- Differentiate between best practices in writing a review of an authored book versus an edited book

- Avoid the 6 most common mistakes made when preparing an academic book review

- Use an e-mail template to solicit an academic book review opportunity from a peer-reviewed journal’s Editor-in-Chief

Paul M. Sutter, PhD is Research Professor of Astrophysics at Stony Brook University, Guest Researcher at the Flatiron Institute in New York City, and contributing editor to Forbes , Space.com , and LiveScience , where his articles are syndicated to CBS News , Scientific American , and MSN , amongst others. Author of over 60 peer-reviewed articles as well as 2 books (published by Prometheus Books and Pegasus Books), he received his PhD in Physics as Department of Energy Computational Science Graduate Fellow at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign before completing post-doctoral fellowships in France at the Institut d’Astrophysique de Paris and in Italy at the Osservatorio Astronomico di Trieste. Since this time, Dr. Sutter has developed one of the most popular astrophysics podcasts in the world and has delivered over 100 conference presentations, seminars, and colloquia at prestigious institutions across the globe. A go-to expert for journalists and producers, he regularly appears on television, radio, and in print, including on the Discovery Channel, History Channel , Science Channel , and Weather Channel .

- Full Name *

- Contact Reason * -- General Inquiry -- Technical Support

- I consent to my data being stored according to the guidelines set out in the Privacy Policy *

- I consent to receiving e-mails with discounts and offers

- Phone This field is for validation purposes and should be left unchanged.

© 2021-2024 Publication Academy, Inc. All Rights Reserved

The Thursday Thinker Terms & Conditions Privacy Policy

This site uses cookies. By continuing to browse the site, you are agreeing to the use of cookies outlined in our Cookie Policy .

Book Reviews: What Should An Academic Book Review Look Like?

- Book Reviews

- Finding Existing Book Reviews

- What Should An Academic Book Review Look Like?

Academic Book Reviews Follow a General Format

Academic Book Reviews are written for two main readers, the academic scholars and specialized readers. Every book review will be different depending on assignment or the audience of review. Generally speaking a review should have the following four sections.

Introduction

- Middle or Body

- Critical Book Review Tip Sheet from University of Alberta Libraries This PDF Tip Sheet has several elements to keep in mind when writing a Academic Book Review.

- Brienza, Casey. “Writing Academic Book Reviews.” Inside Higher Ed, 27 Mar. 2015, https://www.insidehighered.com/advice/2015/03/27/essay-writing-academic-book-reviews.

Standardized citation (MLA, APA, Chicago etc.) also include ISBN, number of pages in book, format (hard cover, online, etc.), and price (check cover or publishers web site for cost)

Should generally cover three basic areas

- how this material fits into existing writings

- authors qualifications and standing in field

- history of topic

- state what the authors thesis is

- evaluate how this thesis compares with the field

- DO NOT just summarize, make sure to add your opinion as reader and expert (even if you don’t feel like one)

- give an overall value added commentary

Middle or Body – Method of Critique

- Author’s main argument

- Individual chapters and arguments

- Author’s methodology

- Accessibility / Readability

- Factual errors

- Appropriateness for intended audience

- Relationship to other research in field

- Originality

- Implications for future study

- Back up opinion with quotes from text

- Follow the Chapters : evaluate and group chapters together following the order of the book.

- Topic / Ideas : organize by the general topics covered in the book and evaluate each grouping as appropriate

- Criticism based : Each paragraph will address your critical points about the book. This can lead to a choppy review offering examples that jump around the text.

- End on a positive note but don’t lie or embellish

- Who should read and why

- Be Detailed but succinct

- Back up criticism with examples from the text.

- Stay away from minor points such as spelling/grammar mistakes, cover art, visual appeal and gossip.

- << Previous: Finding Existing Book Reviews

- Last Updated: Nov 20, 2023 11:38 AM

- URL: https://uscupstate.libguides.com/BookReviews

Writing an Academic Book Review

Book reviews aren’t only for novels. They are widely written and read in academic circles as well. Often, they are also set as assignments for courses in disciplines other than literature. While having to review books as an assignment may baffle some students, there are good reasons why book reviews should be written often in college.

The Purpose of Book Reviews

Reviews of popular books appear in several media, the most visible one being the newspaper. However, specialized academic journals concerned with any subject or discipline publish book reviews too. This is because reviews don’t just express the reviewer’s personal opinion of the book, but also act as a commentary on how well this particular work fulfills its declared aim. Reviews also delve into what and how much the piece of work contributes to the body of knowledge under that discipline.

Another purpose that writing book reviews serves, particularly for students, is that it promotes a deeper analysis and understanding of the book itself and the subject matter at large. It forces the student to be more engaged with the book in order to critically analyze it, rather than just read it passively. The importance of critical analysis and questioning is quite high in academia as it prompts further work on the subject and hence a better understanding of it. Demonstrating this critical analysis in a book review effectively is also just as crucial and further indicates the writer’s grasp of the ideas in the book.

Since book reviews are used as a means of learning, academic book reviews can be written for old texts as well, and not just the latest ones.

Writing a Book Review: How Long Does it Take?

The amount of time needed to write a book review depends on the book being reviewed and the writer.

The length of the book establishes the time needed to first read it. The complexity of the work too may determine to a certain extent how long it would take to understand and analyze it.

How quickly the writer is able to form an opinion of the book depends on their preexisting knowledge and their grasp of the subject matter being discussed. However, these elements don’t determine whether or not the writer should review a said book, especially for academic reasons, as book reviews help greatly in learning well. It is alright even if the questions raised by the reviewer are those that have been answered in previous literature on the subject, as this prompts them to look for those answers and hence expand their knowledge. That being said, having a base of information about the subject of the book is likely to reduce the time needed to review it.

Once a proper understanding of the book has been formed, the only time needed is to articulate and write the review.

Analyzing a Book

In popular book reviews what is foremost is the reviewer’s opinion. Such reviews are highly subjective, so it is possible that the same book receives a wide range of judgments based on who is writing the review.

This is true to a certain extent for academic reviews as well. However, these cannot be as subjective and dependent on the writer’s personal opinion of the work. The opinion needs to be objective – backed up with good reasons and, when needed, evidence as well.

While there is no set method to analyze anything, the following points should be kept in mind when analyzing a book for a book review:

- Before forming an opinion, the reviewer needs to understand the context of the work. This is usually provided within the book itself. In the rare instances this is missing, some preliminary research should be done.

- Assessment of the book should take into consideration the proclaimed aim of the book as well as the structure and construction of its argument.

- The answer to the question of how well the author has supported their various arguments, through either sound reasoning or other forms of evidence, is an important part of the review.

- Very often, the author of the book too has a bearing on the review. Their previous work, the stance they are known to hold, and their reputation and standing should be included when analyzing the work. This is especially important when they are well established and widely recognized as, for example, Noam Chomsky.

- The reviewer should also assess how well the text has helped them understand the main topic and the subject.

- Another element that needs to be clearly determined by the reviewer and indicated in the review is the particular lens through which they are analyzing the book. For instance, a book on the anti-globalization movement could be analyzed based on various perspectives within modern history, development, politics, economics, and many others.

How to Write a Book Review

As with the analysis and in fact most writing, there is no absolute or uniform format for writing a book review. However, the following layout is the most commonly recommended one, especially for beginners. As the writer reviews more books, they may personalize and change this basic format according to their needs and creativity.

- Title of the book along with the publisher’s name and the date of publication

- Introduction : Here, the book can be contextualized within the larger field as well as with regard to the author’s previous work (if any) and their reputation. The aims and the main argument of the text should be stated here as well.

- Summary: A quick précis of the work can be made here. It should outline the structure of the book without going into details. Very brief quotes from the book can be included here and, if required, paraphrasing can be done too. This article on how to paraphrase effectively can be of some help.

- Evaluation: This part includes the reviewer’s opinions of the book. This is the key component of the review. Most of the conclusions from the analysis are to be included here. This is also the space to highlight the specific points in the book that the reviewer appreciated and/or disliked. The reviewer’s answers to the questions of how well the author has fulfilled their aim and supported their arguments are to be given here. Possible gaps in the book can be pointed out, and suggestions can be made with respect to future work on the subject. If the reviewer has read other texts on similar or related subjects, comparisons with those can be made too.

- Conclusion: The writer can conclude their review with a comment on the book as a whole. They can also include their recommendation of the book here.

The language used by the reviewer should be in keeping with academic standards, and not slip into a very informal tone.

Ideally, the reviewer’s final evaluation of the book should be balanced and moderate and not swing to extremes of like or dislike. In certain cases, however, such subjective judgments can be expressed.

- Peterborough

How to Write Academic Reviews

- What is a review?

- Common problems with academic reviews

- Getting started: approaches to reading and notetaking

- Understanding and analyzing the work

- Organizing and writing the review

What Is a Review?

A scholarly review describes, analyzes, and evaluates an article, book, film, or performance (through this guide we will use the term “work” to refer to the text or piece to be reviewed). A review also shows how a work fits into its disciplines and explains the value or contribution of the work to the field.

Reviews play an important role in scholarship. They give scholars the opportunity to respond to one another’s research, ideas and interpretations. They also provide an up-to-date view of a discipline. We recommend you seek out reviews in current scholarly journals to become familiar with recent scholarship on a topic and to understand the forms review writing takes in your discipline. Published scholarly reviews are helpful models for beginner review-writers. However, we remind you that you are to write your own assessment of the work, not rely on the assessment from a review you found in a journal or on a blog.

As a review-writer, your objective is to:

- understand a work on its own terms (analyze it)

- bring your own knowledge to bear on a work (respond to it)

- critique the work while considering validity, truth, and slant (evaluate it)

- place the work in context (compare it to other works).

Common Problems with Academic Reviews

A review is not a research paper.

Rather than a research paper on the subject of the work,an academic review is an evaluation about the work’s message, strengths, and value. For example, a review of Finis Dunaway’s Seeing Green would not include your own research about media coverage of the environmental movement; instead, your review would assess Dunaway’s argument and its significance to the field.

A review is not a summary

It is important to synthesize the contents and significance of the work you review, but the main purpose of a review is to evaluate, critically analyze, or comment on the text. Keep your summary of the work brief, and make specific references to its message and evidence in your assessment of the work.

A review is not an off-the-cuff, unfair personal response

An effective review must be fair and accurate. It is important to see what is actually in front of you when your first reaction to the tone, argument, or subject of what you are reviewing is extremely negative or positive.

You will present your personal views on the work, but they must be explained and supported with evidence. Rather than writing, “I thought the book was interesting,” you can explain why the book was interesting and how it might offer new insights or important ideas. Further, you can expand on a statement such as “The movie was boring,” by explaining how it failed to interest you and pointing toward specific disappointing moments.

Getting Started: Approaches to Reading and Notetaking

Pre-reading.

Pre-reading helps a reader to see a book as a whole. Often, the acknowledgments, preface, and table of contents of a book offer insights about the book’s purpose and direction. Take time before you begin chapter one to read the introduction and conclusion, examine chapter titles, and to explore the index or references pages.

Read more about strategies for critical and efficient reading

Reverse outline

A reverse outline helps a reader analyze the content and argument of a work of non-fiction. Read each section of a text carefully and write down two things: 1) the main point or idea, and 2) its function in the text. In other words, write down what each section says and what it does. This will help you to see how the author develops their argument and uses evidence for support.

Double-entry notebook

In its simplest form, the double-entry notebook separates a page into two columns. In one column, you make observations about the work. In the other, you note your responses to the work. This notetaking method has two advantages. It forces you to make both sorts of notes — notes about the work and notes about your reaction to the work — and it helps you to distinguish between the two.

Whatever method of notetaking you choose, do take notes, even if these are scribbles in the margin. If you don’t, you might rely too heavily on the words, argument, or order of what you are reviewing when you come to write your review.

Understand and Analyze the Work

It is extremely important to work toward seeing a clear and accurate picture of a work. One approach is to try to suspend your judgment for a while, focusing instead on describing or outlining a text. A student once described this as listening to the author’s voice rather than to their own.

Ask questions to support your understanding of the work.

Questions for Works of Non-Fiction

- What is the subject/topic of the work? What key ideas do you think you should describe in your review?

- What is the thesis, main theme, or main point?

- What major claims or conclusions does the author make? What issues does the work illuminate?

- What is the structure of the work? How does the author build their argument?

- What sources does the author consult? What evidence is used to support claims? Do these sources in any way “predetermine” certain conclusions?

- Is there any claim for which the evidence presented is insufficient or slight? Do any conclusions rest on evidence that may be atypical?

- How is the argument developed? How do the claims relate? What does the conclusion reveal?

Questions for Works of Fiction

- What is the main theme or message? What issues does the book illuminate?

- How does the work proceed? How does the author build their plot?

- What kind of language, descriptions, or sections of plot alert you to the themes and significance of the book?

- What does the conclusion reveal when compared with the beginning?

Read Critically

Being critical does not mean criticizing. It means asking questions and formulating answers. Critical reading is not reading with a “bad attitude.” Critical readers do not reject a text or take a negative approach to it; they inquire about a text, an author, themselves, and the context surrounding all three, and they attempt to understand how and why the author has made the particular choices they have.

Think about the Author

You can often tell a lot about an author by examining a text closely, but sometimes it helps to do a little extra research. Here are some questions about the author that would be useful to keep in mind when you are reading a text critically:

- Who is the author? What else has the author written?

- What does the author do? What experiences of the author’s might influence the writing of this book?

- What is the author’s main purpose or goal for the text? Why did they write it and what do they want to achieve?

- Does the author indicate what contribution the text makes to scholarship or literature? What does the author say about their point of view or method of approaching the subject? In other words, what position does the author take?

Think about Yourself

Because you are doing the interpreting and evaluating of a text, it is important to examine your own perspective, assumptions, and knowledge (positionality) in relation to the text. One way to do this is by writing a position statement that outlines your view of the subject of the work you are reviewing. What do you know, believe, or assume about this subject? What in your life might influence your approach to this text?

Here are some prompts that might help you generate a personal response to a book:

- I agree that ... because ...

- I disagree that ... because ...

- I don’t understand ...

- This reminds me of …

- I’m surprised by …

Another way to examine your thoughts in relation to a text is to note your initial response to the work. Consider your experience of the text – did you like it? Why or why not?

- What did I feel when I read this book? Why?

- How did I experience the style or tone of the author? How would I characterize each?

- What questions would I ask this author if I could?

- For me, what are the three best things about this book? The three worst things? Why?

Consider Context

A reviewer needs to examine the context of the book to arrive at a fair understanding and evaluation of its contents and importance. Context may include the scholarship to which this book responds or the author’s personal motive for writing. Or perhaps the context is simply contemporary society or today’s headlines. It is certainly important to consider how the work relates to the course that requires the review.

Here are some useful questions:

- What are the connections between this work and others on similar subjects? How does it relate to core concepts in my course or my discipline?

- What is the scholarly or social significance of this work? What contribution does it make to our understanding?

- What, of relevance, is missing from the work: certain kinds of evidence or methods of analysis/development? A particular theoretical approach? The experiences of certain groups?

- What other perspectives or conclusions are possible?

Once you have taken the time to thoroughly understand and analyze the work, you will have a clear perspective on its strengths and weaknesses and its value within the field. Take time to categorize your ideas and develop an outline; this will ensure your review is well organized and clear.

Organizing and Writing the Review

A review is organized around an assessment of the work or a focused message about its value to the field. Revisit your notes and consider your responses to your questions from critical reading to develop a clear statement that evaluates the work and provides an explanation for that evaluation.

For example:

X is an important work because it provides a new perspective on . . .

X’s argument is compelling because . . . ; however, it fails to address . . .

Although X claims to . . ., they make assumptions about . . . , which diminishes the impact . . .

This statement or evaluation is presented in the introduction. The body of the review works to support or explain your assessment; organize your key ideas or supporting arguments into paragraphs and use evidence from the book, article, or film to demonstrate how the work is (or is not) effective, compelling, provocative, novel, or informative.

As with all scholarly writing, a well-organized structure supports the clarity of your review. There is not a rigid formula for organization, but you may find the following guidelines to be helpful. Note that reviews do not typically include subheadings; the headings listed here serve to help you think about the main sections of your academic review.

Introduction

Introduce the work, the author (or director/producer), and the points you intend to make about this work. In addition, you should

- give relevant bibliographic information

- give the reader a clear idea of the nature, scope, and significance of the work

- indicate your evaluation of the work in a clear 1-2 sentence thesis statement

Provide background information to help your readers understand the importance of the work or the reasons for your appraisal. Background information could include:

- why the issue examined is of current interest

- other scholarship about this subject

- the author’s perspective, methodology, purpose

- the circumstances under which the book was created

Sample Introduction