Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

Introduction

2 A Short History of Media and Culture

Learning Objectives

- Discuss events that impacted the adaptation of mass media.

- Explain how different technological transitions have shaped media industries.

Until Johannes Gutenberg’s 15th-century invention of the movable type printing press, books were painstakingly handwritten, and no two copies were exactly the same. The printing press made the mass production of print media possible. Not only was it much cheaper to produce written material, but new transportation technologies also made it easier for texts to reach a wide audience. It’s hard to overstate the importance of Gutenberg’s invention, which helped usher in massive cultural movements like the European Renaissance and the Protestant Reformation. In 1810, another German printer, Friedrich Koenig, pushed media production even further when he essentially hooked the steam engine up to a printing press, enabling the industrialization of printed media. In 1800, a hand-operated printing press could produce about 480 pages per hour; Koenig’s machine more than doubled this rate. (By the 1930s, many printing presses had an output of 3000 pages an hour.) This increased efficiency helped lead to the rise of the daily newspaper.

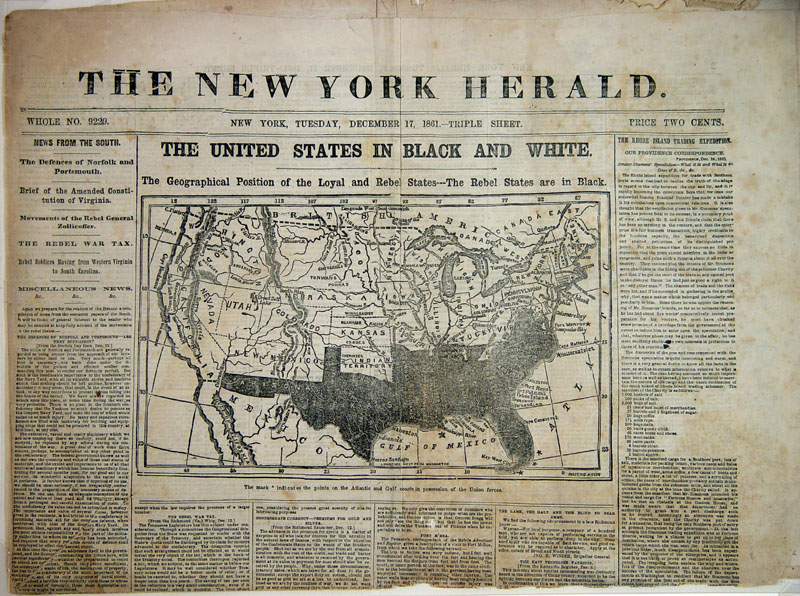

As the first Europeans settled the land that would come to be called the United States of America, the newspaper was an essential medium. At first, newspapers helped the Europeans stay connected with events back home. But as the people developed their own way of life—their own culture —newspapers helped give expression to that culture. Political scientist Benedict Anderson has argued that newspapers also helped forge a sense of national identity by treating readers across the country as part of one unified group with common goals and values. Newspapers, he said, helped create an “imagined community.”

The United States continued to develop, and the newspaper was the perfect medium for the increasingly urbanized Americans of the 19th century, who could no longer get their local news merely through gossip and word of mouth. These Americans were living in an unfamiliar world, and newspapers and other publications helped them negotiate the rapidly changing world. The Industrial Revolution meant that people had more leisure time and more money, and media helped them figure out how to spend both.

In the early decades of the 20th century, the first major non-print forms of mass media—film and radio—exploded in popularity. Radios, which were less expensive than telephones and widely available by the 1920s, especially had the unprecedented ability of allowing huge numbers of people to listen to the same event at the same time.

The reach of radio also further helped forge an American culture. The medium was able to downplay regional differences and encourage a unified sense of the American lifestyle—a lifestyle that was increasingly driven and defined by consumer purchases. “Americans in the 1920s were the first to wear ready-made, exact-size clothing…to play electric phonographs, to use electric vacuum cleaners, to listen to commercial radio broadcasts, and to drink fresh orange juice year round.In countless ways, large and small, American life was transformed during the 1920s, at least in urban areas. Cigarettes, cosmetics, and synthetic fabrics such as rayon became staples of American life. Newspaper gossip columns, illuminated billboards, and commercial airplane flights were novelties during the 1920s. The United States became a consumer society.” [1]

The post-World War II era in the United States was marked by prosperity, and by the introduction of a seductive new form of mass communication: television. In 1946, there were about 17,000 televisions in the entire United States. Within seven years, two-thirds of American households owned at least one set. As the United States’ gross national product (GNP) doubled in the 1950s, and again in the 1960s, the American home became firmly ensconced as a consumer unit. Along with a television, the typical U.S. family owned a car and a house in the suburbs, all of which contributed to the nation’s thriving consumer-based economy.

Broadcast television was the dominant form of mass media. There were just three major networks, and they controlled over 90 percent of the news programs, live events, and sitcoms viewed by Americans. On some nights, close to half the nation watched the same show! Some social critics argued that television was fostering a homogenous, conformist culture by reinforcing ideas about what “normal” American life looked like. But television also contributed to the counterculture of the 1960s. The Vietnam War was the nation’s first televised military conflict, and nightly images of war footage and war protestors helped intensify the nation’s internal conflicts.

Broadcast technology, including radio and television, had such a hold of the American imagination that newspapers and other print media found themselves having to adapt to the new media landscape. Print media was more durable and easily archived, and allowed users more flexibility in terms of time—once a person had purchased a magazine, he could read it whenever and wherever he’d like. Broadcast media, in contrast, usually aired programs on a fixed schedule, which allowed it to both provide a sense of immediacy but also impermanence—until the advent of digital video recorders in the 21st century, it was impossible to pause and rewind a television broadcast.

The media world faced drastic changes once again in the 1980s and 1990s with the spread of cable television. During the early decades of television, viewers had a limited number of channels from which to choose. In 1975, the three major networks accounted for 93 percent of all television viewing. By 2004, however, this share had dropped to 28.4 percent of total viewing, thanks to the spread of cable television. Cable providers allowed viewers a wide menu of choices, including channels specifically tailored to people who wanted to watch only golf, weather, classic films, sermons, or videos of sharks. Still, until the mid-1990s, television was dominated by the three large networks. The Telecommunications Act of 1996, an attempt to foster competition by deregulating the industry, actually resulted in many mergers and buyouts of small companies by large companies. The broadcast spectrum in many places was in the hands of a few large corporations. In 2003, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) loosened regulation even further, allowing a single company to own 45 percent of a single market (up from 25 percent in 1982).

Technological Transitions Shape Media Industries

New media technologies both spring from and cause cultural change. For this reason, it can be difficult to neatly sort the evolution of media into clear causes and effects. Did radio fuel the consumerist boom of the 1920s, or did the radio become wildly popular because it appealed to a society that was already exploring consumerist tendencies? Probably a little bit of both. Technological innovations such as the steam engine, electricity, wireless communication, and the Internet have all had lasting and significant effects on American culture. As media historians Asa Briggs and Peter Burke note, every crucial invention came with “a change in historical perspectives.” [2] Electricity altered the way people thought about time, since work and play were no longer dependent on the daily rhythms of sunrise and sunset. Wireless communication collapsed distance. The Internet revolutionized the way we store and retrieve information.

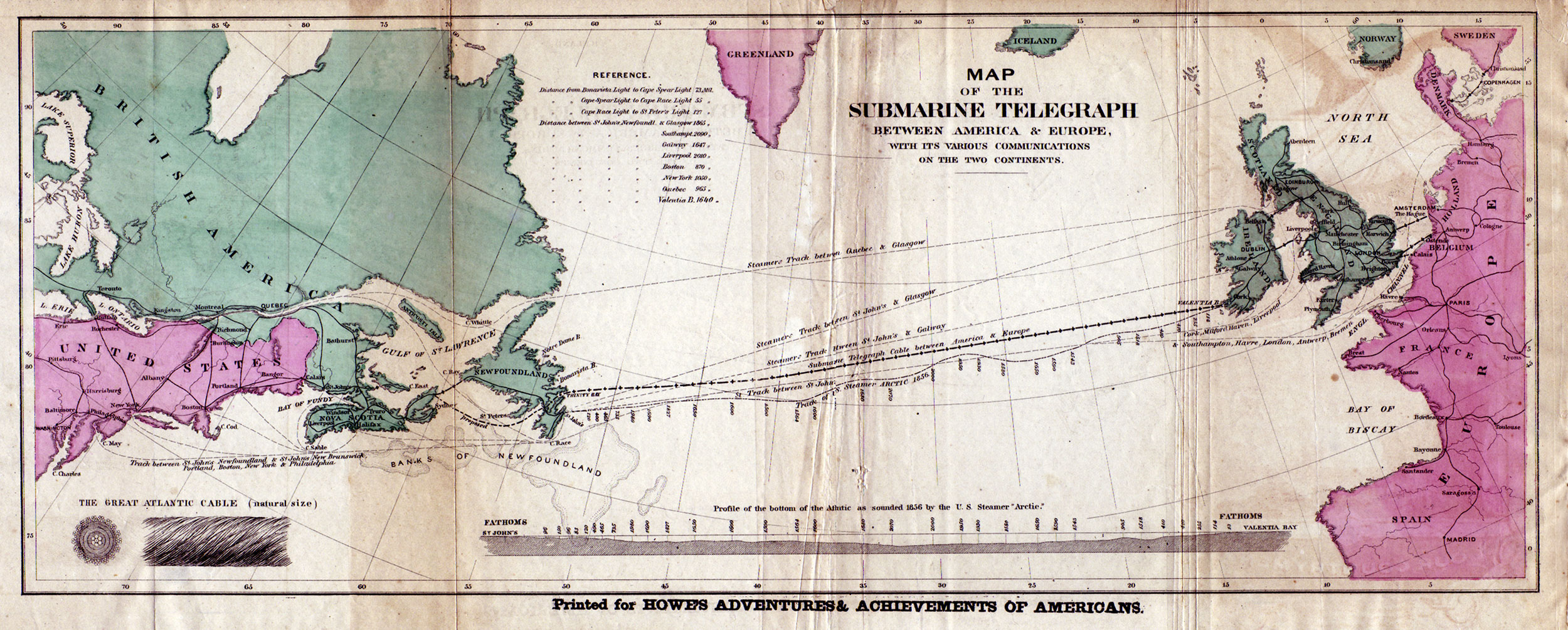

The contemporary media age can trace its origins back to the electrical telegraph, patented in the United States by Samuel Morse in 1837. Thanks to the telegraph, communication was no longer linked to the physical transportation of messages. Suddenly, it didn’t matter whether a message needed to travel five or five hundred miles. Suddenly, information from distant places was nearly as accessible as local news. When the first transatlantic cable was laid in 1858, allowing near-instantaneous communication from the United States to Europe, The London Times described it as “the greatest discovery since that of Columbus, a vast enlargement…given to the sphere of human activity.” [2] Celebrations broke out in New York as people marveled at the new media. Telegraph lines began to stretch across the globe, making their own kind of world wide web.

Not long after the telegraph, wireless communication (which eventually led to the development of radio, television, and other broadcast media) emerged as an extension of telegraph technology. Although many 19th-century inventors, including Nikola Tesla, had a hand in early wireless experiments, it was Italian-born Guglielmo Marconi who is recognized as the developer of the first practical wireless radio system. This mysterious invention, where sounds seemed to magically travel through the air, captured the world’s imagination. Early radio was used for military communication, but soon the technology entered the home. The radio mania that swept the country inspired hundreds of applications for broadcasting licenses, some from newspapers and other news outlets, while other radio station operators included retail stores, schools, and even cities. In the 1920s, large media networks—including the National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS)—were launched, and they soon began to dominate the airwaves. In 1926, they owned 6.4 percent of U.S. broadcasting stations; by 1931, that number had risen to 30 percent. [2]

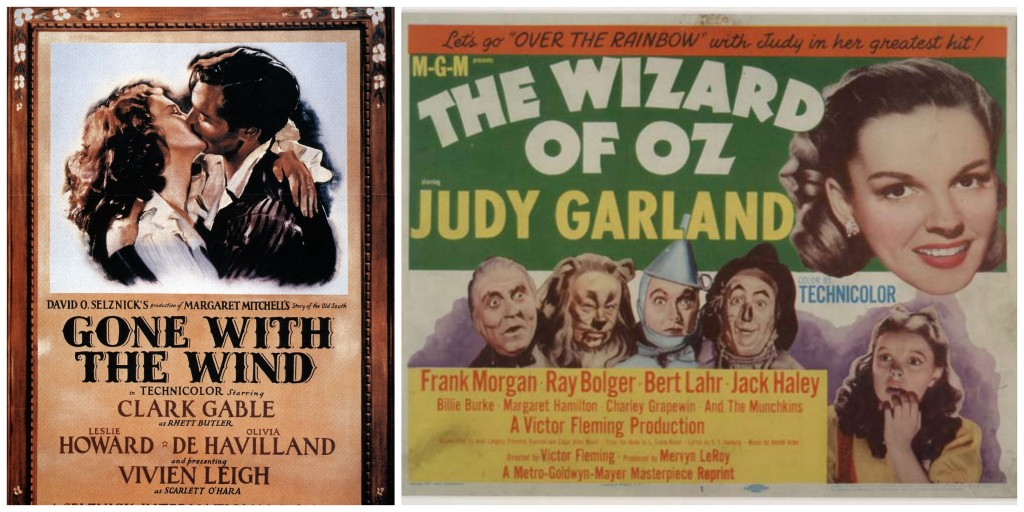

The 19th-century development of photographic technologies would lead to the later innovations of cinema and television. As with wireless technology, several inventors independently came up with photography at the same time, among them the French inventors Joseph Niepce and Louis Daguerre, and British scientist William Henry Fox Talbot. In the United States, George Eastman developed the Kodak camera in 1888, banking on the hope that Americans would welcome an inexpensive, easy-to-use camera into their homes, as they had with the radio and telephone. Moving pictures were first seen around the turn of the century, with the first U.S. projection hall opening in Pittsburgh in 1905. By the 1920s, Hollywood had already created its first stars, most notably Charlie Chaplin. By the end of the 1930s, Americans were watching color films with full sound, including Gone with the Wind and The Wizard of Oz .

Television, which consists of an image being converted to electrical impulses, transmitted through wires or radio waves, and then reconverted into images, existed before World War II but really began to take off in the 1950s. In 1947, there were 178,000 television sets made in the United States; five years later, there were 15 million. Radio, cinema, and live theater all saw a decline in the face of this new medium that allowed viewers to be entertained with sound and moving pictures without having to leave their homes.

For the last stage in this fast history of media technology, how’s this for a prediction? In 1969, management consultant Peter Drucker predicted that the next major technological innovation after television would be an “electronic appliance” that would be “capable of being plugged in wherever there is electricity and giving immediate access to all the information needed for school work from first grade through college.” He said it would be the equivalent of Edison’s light bulb in its ability to revolutionize how we live. He had, in effect, predicted the computer. He was prescient about the effect that computers and the Internet would have on education, social relationships, and the culture at large. The inventions of random access memory (RAM) chips and microprocessors in the 1970s were important steps along the way to the Internet age. As Briggs and Burke note, these advances meant that “hundreds of thousands of components could be carried on a microprocessor.” The reduction of many different kinds of content to digitally stored information meant that “print, film, recording, radio and television and all forms of telecommunications [were] now being thought of increasingly as part of one complex.” This process, also known as convergence, will be discussed in later chapters and is a force that is shaping the face of media today.

Key Takeaways

- Gutenberg’s invention of the printing press enabled the mass production of media, which was then industrialized by Friedrich Koenig in the early 1800s. These innovations enabled the daily newspaper, which united the urbanized, industrialized populations of the 19th century.

- In the 20th century, radio allowed advertisers to reach a mass audience and helped spur the consumerism of the 1920s—and the Great Depression of the 1930s. After World War II, television boomed in the United States and abroad, though its concentration in the hands of three major networks led to accusations of conformity. The spread of cable and subsequent deregulation in the 1980s and 1990s led to more channels, but not necessarily more diverse ownership.

- Technological transitions have also had great effect on the media industry, although it is difficult to say whether technology caused a cultural shift or rather resulted from it. The ability to make technology small and affordable enough to fit into the home is an important aspect of the popularization of new technologies.

[1] “The Consumer Economy and Mass Entertainment,” https://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtID=2&psid=3396 (accessed July 11, 2023).

[2] Asa Briggs and Peter Burke, A Social History of the Media: From Gutenberg to the Internet, Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2005.

This chapter is adapted from Chapter 1 of Understanding Media and Culture: An Introduction to Mass Communication by The Saylor Foundation.

Media and Cultural Studies Copyright © by Cathie LeBlanc is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

- school Campus Bookshelves

- menu_book Bookshelves

- perm_media Learning Objects

- login Login

- how_to_reg Request Instructor Account

- hub Instructor Commons

Margin Size

- Download Page (PDF)

- Download Full Book (PDF)

- Periodic Table

- Physics Constants

- Scientific Calculator

- Reference & Cite

- Tools expand_more

- Readability

selected template will load here

This action is not available.

9.3: The Evolution of the Media

- Last updated

- Save as PDF

- Page ID 82235

\( \newcommand{\vecs}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vecd}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash {#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\) \( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\) \( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\) \( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\) \( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\inner}[2]{\langle #1, #2 \rangle}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\)

\( \newcommand{\id}{\mathrm{id}}\)

\( \newcommand{\kernel}{\mathrm{null}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\range}{\mathrm{range}\,}\)

\( \newcommand{\RealPart}{\mathrm{Re}}\)

\( \newcommand{\ImaginaryPart}{\mathrm{Im}}\)

\( \newcommand{\Argument}{\mathrm{Arg}}\)

\( \newcommand{\norm}[1]{\| #1 \|}\)

\( \newcommand{\Span}{\mathrm{span}}\) \( \newcommand{\AA}{\unicode[.8,0]{x212B}}\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorA}[1]{\vec{#1}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorAt}[1]{\vec{\text{#1}}} % arrow\)

\( \newcommand{\vectorB}[1]{\overset { \scriptstyle \rightharpoonup} {\mathbf{#1}} } \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorC}[1]{\textbf{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorD}[1]{\overrightarrow{#1}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectorDt}[1]{\overrightarrow{\text{#1}}} \)

\( \newcommand{\vectE}[1]{\overset{-\!-\!\rightharpoonup}{\vphantom{a}\smash{\mathbf {#1}}}} \)

Learning Objectives

By the end of this section, you will be able to:

- Discuss the history of major media formats

- Compare important changes in media types over time

- Explain how citizens learn political information from the media

The evolution of the media has been fraught with concerns and problems. Accusations of mind control, bias, and poor quality have been thrown at the media on a regular basis. Yet the growth of communications technology allows people today to find more information more easily than any previous generation. Mass media can be print, radio, television, or Internet news. They can be local, national, or international. They can be broad or limited in their focus. The choices are tremendous.

Print Media

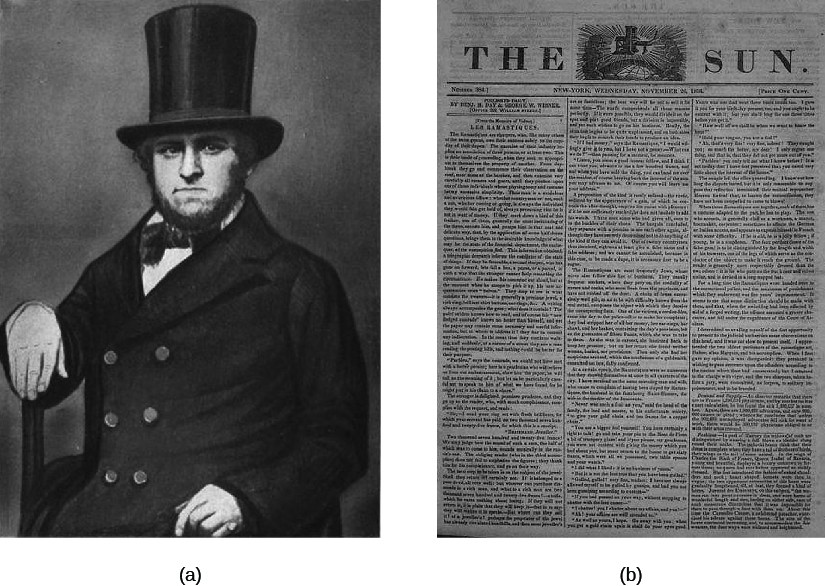

Early news was presented to local populations through the print press. While several colonies had printers and occasional newspapers, high literacy rates combined with the desire for self-government made Boston a perfect location for the creation of a newspaper, and the first continuous press was started there in 1704. [1]

Newspapers spread information about local events and activities. The Stamp Tax of 1765 raised costs for publishers, however, leading several newspapers to fold under the increased cost of paper. The repeal of the Stamp Tax in 1766 quieted concerns for a short while, but editors and writers soon began questioning the right of the British to rule over the colonies. Newspapers took part in the effort to inform citizens of British misdeeds and incite attempts to revolt. Readership across the colonies increased to nearly forty thousand homes (among a total population of two million), and daily papers sprang up in large cities. [2]

Although newspapers united for a common cause during the Revolutionary War, the divisions that occurred during the Constitutional Convention and the United States’ early history created a change. The publication of the Federalist Papers , as well as the Anti-Federalist Papers, in the 1780s, moved the nation into the party press era , in which partisanship and political party loyalty dominated the choice of editorial content. One reason was cost. Subscriptions and advertisements did not fully cover printing costs, and political parties stepped in to support presses that aided the parties and their policies. Papers began printing party propaganda and messages, even publicly attacking political leaders like George Washington. Despite the antagonism of the press, Washington and several other founders felt that freedom of the press was important for creating an informed electorate. Indeed, freedom of the press is enshrined in the Bill of Rights in the first amendment.

Between 1830 and 1860, machines and manufacturing made the production of newspapers faster and less expensive. Benjamin Day’s paper, the New York Sun , used technology like the linotype machine to mass-produce papers. Roads and waterways were expanded, decreasing the costs of distributing printed materials to subscribers. New newspapers popped up. The popular penny press papers and magazines contained more gossip than news, but they were affordable at a penny per issue. Over time, papers expanded their coverage to include racing, weather, and educational materials. By 1841, some news reporters considered themselves responsible for upholding high journalistic standards, and under the editor (and politician) Horace Greeley, the New-York Tribune became a nationally respected newspaper. By the end of the Civil War, more journalists and newspapers were aiming to meet professional standards of accuracy and impartiality. [3]

Yet readers still wanted to be entertained. Joseph Pulitzer and the New York World gave them what they wanted. The tabloid-style paper included editorial pages, cartoons, and pictures, while the front-page news was sensational and scandalous. This style of coverage became known as yellow journalism . Ads sold quickly thanks to the paper’s popularity, and the Sunday edition became a regular feature of the newspaper. As the New York World’s circulation increased, other papers copied Pulitzer’s style in an effort to sell papers. Competition between newspapers led to increasingly sensationalized covers and crude issues.

In 1896, Adolph Ochs purchased the New York Times with the goal of creating a dignified newspaper that would provide readers with important news about the economy, politics, and the world rather than gossip and comics. The New York Times brought back the informational model, which exhibits impartiality and accuracy and promotes transparency in government and politics. With the arrival of the Progressive Era, the media began muckraking : the writing and publishing of news coverage that exposed corrupt business and government practices. Investigative work like Upton Sinclair’s serialized novel The Jungle led to changes in the way industrial workers were treated and local political machines were run. The Pure Food and Drug Act and other laws were passed to protect consumers and employees from unsafe food processing practices. Local and state government officials who participated in bribery and corruption became the centerpieces of exposés.

Some muckraking journalism still appears today, and the quicker movement of information through the system would seem to suggest an environment for yet more investigative work and the punch of exposés than in the past. However, at the same time there are fewer journalists being hired than there used to be. The scarcity of journalists and the lack of time to dig for details in a 24-hour, profit-oriented news model make investigative stories rare. [4]

There are two potential concerns about the decline of investigative journalism in the digital age. First, one potential shortcoming is that the quality of news content will become uneven in depth and quality, which could lead to a less informed citizenry. Second, if investigative journalism in its systematic form declines, then the cases of wrongdoing that are the objects of such investigations would have a greater chance of going on undetected. In the twenty-first century, newspapers have struggled to stay financially stable. Print media earned $44.9 billion from ads in 2003, but only $16.4 billion from ads in 2014. [5]

Given the countless alternate forms of news, many of which are free, newspaper subscriptions have fallen. Advertising and especially classified ad revenue dipped. Many newspapers now maintain both a print and an Internet presence in order to compete for readers. The rise of free news blogs, such as the Huffington Post , have made it difficult for newspapers to force readers to purchase online subscriptions to access material they place behind a digital paywall . Some local newspapers, in an effort to stay visible and profitable, have turned to social media, like Facebook and Twitter. Stories can be posted and retweeted, allowing readers to comment and forward material. [6]

Yet, overall, newspapers have adapted, becoming leaner—though less thorough and investigative—versions of their earlier selves.

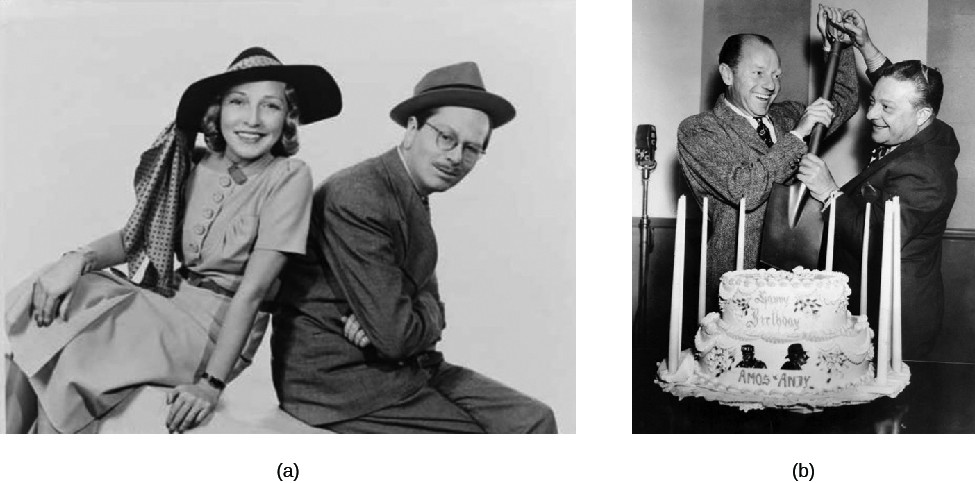

Radio news made its appearance in the 1920s. The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) and the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS) began running sponsored news programs and radio dramas. Comedy programs, such as Amos ’n’ Andy , The Adventures of Gracie , and Easy Aces , also became popular during the 1930s, as listeners were trying to find humor during the Depression. Talk shows, religious shows, and educational programs followed, and by the late 1930s, game shows and quiz shows were added to the airwaves. Almost 83 percent of households had a radio by 1940, and most tuned in regularly. [7]

Not just something to be enjoyed by those in the city, the proliferation of the radio brought communications to rural America as well. News and entertainment programs were also targeted to rural communities. WLS in Chicago provided the National Farm and Home Hour and the WLS Barn Dance . WSM in Nashville began to broadcast the live music show called the Grand Ole Opry , which is still broadcast every week and is the longest live broadcast radio show in U.S. history. [8]

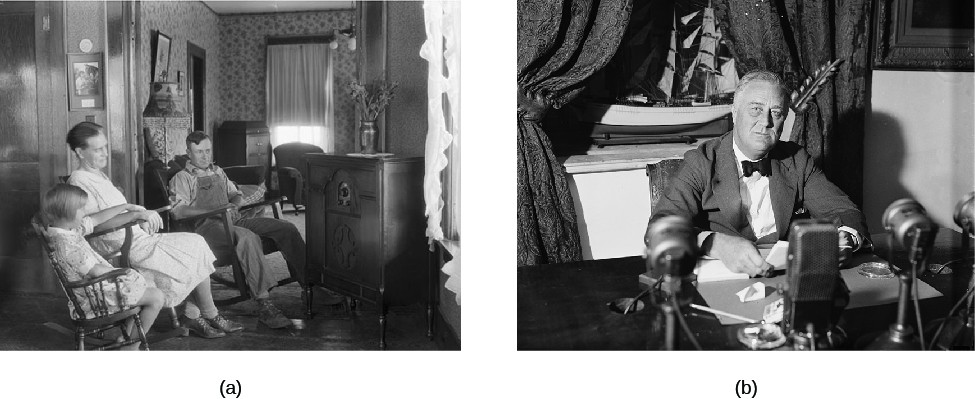

As radio listenership grew, politicians realized that the medium offered a way to reach the public in a personal manner. Warren Harding was the first president to regularly give speeches over the radio. President Herbert Hoover used radio as well, mainly to announce government programs on aid and unemployment relief. [9]

Yet it was Franklin D. Roosevelt who became famous for harnessing the political power of radio. On entering office in March 1933, President Roosevelt needed to quiet public fears about the economy and prevent people from removing their money from the banks. He delivered his first radio speech eight days after assuming the presidency:

Roosevelt spoke directly to the people and addressed them as equals. One listener described the chats as soothing, with the president acting like a father, sitting in the room with the family, cutting through the political nonsense and describing what help he needed from each family member. [11]

Roosevelt would sit down and explain his ideas and actions directly to the people on a regular basis, confident that he could convince voters of their value. [12]

His speeches became known as “ fireside chats ” and formed an important way for him to promote his New Deal agenda. Roosevelt’s combination of persuasive rhetoric and the media allowed him to expand both the government and the presidency beyond their traditional roles. [13]

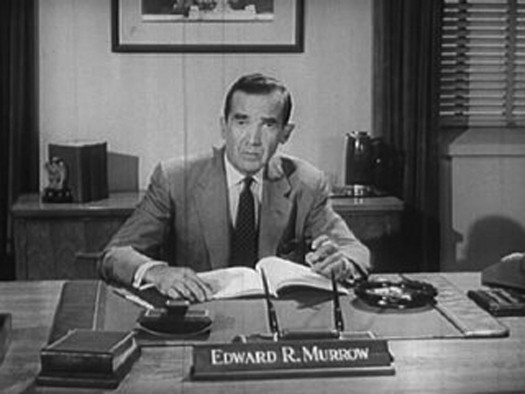

During this time, print news still controlled much of the information flowing to the public. Radio news programs were limited in scope and number. But in the 1940s the German annexation of Austria, conflict in Europe, and World War II changed radio news forever. The need and desire for frequent news updates about the constantly evolving war made newspapers, with their once-a-day printing, too slow. People wanted to know what was happening, and they wanted to know immediately. Although initially reluctant to be on the air, reporter Edward R. Murrow of CBS began reporting live about Germany’s actions from his posts in Europe. His reporting contained news and some commentary, and even live coverage during Germany’s aerial bombing of London. To protect covert military operations during the war, the White House had placed guidelines on the reporting of classified information, making a legal exception to the First Amendment’s protection against government involvement in the press. Newscasters voluntarily agreed to suppress information, such as about the development of the atomic bomb and movements of the military, until after the events had occurred. [14]

The number of professional and amateur radio stations grew quickly. Initially, the government exerted little legislative control over the industry. Stations chose their own broadcasting locations, signal strengths, and frequencies, which sometimes overlapped with one another or with the military, leading to tuning problems for listeners. The Radio Act (1927) created the Federal Radio Commission (FRC), which made the first effort to set standards, frequencies, and license stations. The Commission was under heavy pressure from Congress, however, and had little authority. The Communications Act of 1934 ended the FRC and created the Federal Communications Commission (FCC), which continued to work with radio stations to assign frequencies and set national standards, as well as oversee other forms of broadcasting and telephones. The FCC regulates interstate communications to this day. For example, it prohibits the use of certain profane words during certain hours on public airwaves.

Prior to WWII, radio frequencies were broadcast using amplitude modulation (AM). After WWII, frequency modulation (FM) broadcasting, with its wider signal bandwidth, provided clear sound with less static and became popular with stations wanting to broadcast speeches or music with high-quality sound. While radio’s importance for distributing news waned with the increase in television usage, it remained popular for listening to music, educational talk shows, and sports broadcasting. Talk stations began to gain ground in the 1980s on both AM and FM frequencies, restoring radio’s importance in politics. By the 1990s, talk shows had gone national, showcasing broadcasters like Rush Limbaugh and Don Imus.

In 1990, Sirius Satellite Radio began a campaign for FCC approval of satellite radio. The idea was to broadcast digital programming from satellites in orbit, eliminating the need for local towers. By 2001, two satellite stations had been approved for broadcasting. Satellite radio has greatly increased programming with many specialized offerings, such as channels dedicated to particular artists. It is generally subscription-based and offers a larger area of coverage, even to remote areas such as deserts and oceans. Satellite programming is also exempt from many of the FCC regulations that govern regular radio stations. Howard Stern, for example, was fined more than $2 million while on public airwaves, mainly for his sexually explicit discussions. [15] Stern moved to Sirius Satellite in 2006 and has since been free of oversight and fines.

Television combined the best attributes of radio and pictures and changed media forever. The first official broadcast in the United States was President Franklin Roosevelt’s speech at the opening of the 1939 World’s Fair in New York. The public did not immediately begin buying televisions, but coverage of World War II changed their minds. CBS reported on war events and included pictures and maps that enhanced the news for viewers. By the 1950s, the price of television sets had dropped, more televisions stations were being created, and advertisers were buying up spots.

As on the radio, quiz shows and games dominated the television airwaves. But when Edward R. Murrow made the move to television in 1951 with his news show See It Now , television journalism gained its foothold. As television programming expanded, more channels were added. Networks such as ABC, CBS, and NBC began nightly newscasts, and local stations and affiliates followed suit.

Even more than radio, television allows politicians to reach out and connect with citizens and voters in deeper ways. Before television, few voters were able to see a president or candidate speak or answer questions in an interview. Now everyone can decode body language and tone to decide whether candidates or politicians are sincere. Presidents can directly convey their anger, sorrow, or optimism during addresses.

The first television advertisements, run by presidential candidates Dwight D. Eisenhower and Adlai Stevenson in the early 1950s, were mainly radio jingles with animation or short question-and-answer sessions. In 1960, John F. Kennedy ’s campaign used a Hollywood-style approach to promote his image as young and vibrant. The Kennedy campaign ran interesting and engaging ads, featuring Kennedy, his wife Jacqueline, and everyday citizens who supported him.

Television was also useful to combat scandals and accusations of impropriety. Republican vice presidential candidate Richard Nixon used a televised speech in 1952 to address accusations that he had taken money from a political campaign fund illegally. Nixon laid out his finances, investments, and debts and ended by saying that the only election gift the family had received was a cocker spaniel the children named Checkers. [16]

The “Checkers speech” was remembered more for humanizing Nixon than for proving he had not taken money from the campaign account. Yet it was enough to quiet accusations. Democratic vice presidential nominee Geraldine Ferraro similarly used television to answer accusations in 1984, holding a televised press conference to answer questions for over two hours about her husband’s business dealings and tax returns. [17]

In addition to television ads, the 1960 election also featured the first televised presidential debate. By that time most households had a television. Kennedy’s careful grooming and practiced body language allowed viewers to focus on his presidential demeanor. His opponent, Richard Nixon, was still recovering from a severe case of the flu. While Nixon’s substantive answers and debate skills made a favorable impression on radio listeners, viewers’ reaction to his sweaty appearance and obvious discomfort demonstrated that live television had the potential to make or break a candidate. [18]

In 1964, Lyndon B. Johnson was ahead in the polls, and he let Barry Goldwater’s campaign know he did not want to debate. [19] Nixon, who ran for president again in 1968 and 1972, declined to debate. Then in 1976, President Gerald Ford, who was behind in the polls, invited Jimmy Carter to debate, and televised debates became a regular part of future presidential campaigns. [20]

Between the 1960s and the 1990s, presidents often used television to reach citizens and gain support for policies. When they made speeches, the networks and their local affiliates carried them. With few independent local stations available, a viewer had little alternative but to watch. During this “Golden Age of Presidential Television,” presidents had a strong command of the media. [21]

Some of the best examples of this power occurred when presidents used television to inspire and comfort the population during a national emergency. These speeches aided in the “rally ’round the flag” phenomenon, which occurs when a population feels threatened and unites around the president. [22] During these periods, presidents may receive heightened approval ratings, in part due to the media’s decision about what to cover. [23]

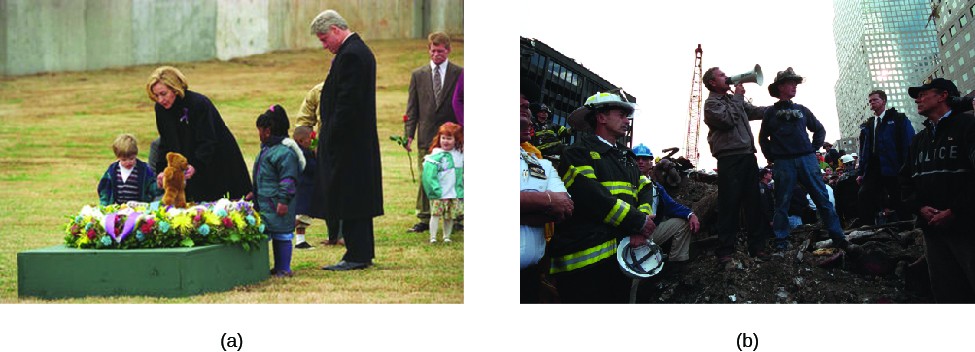

In 1995, President Bill Clinton comforted and encouraged the families of the employees and children killed at the bombing of the Oklahoma City Federal Building. Clinton reminded the nation that children learn through action, and so we must speak up against violence and face evil acts with good acts. [24]

Following the terrorist attacks in New York and Washington on September 11, 2001, President George W. Bush’s bullhorn speech from the rubble of Ground Zero in New York similarly became a rally. Bush spoke to the workers and first responders and encouraged them, but his short speech became a viral clip demonstrating the resilience of New Yorkers and the anger of a nation. [25] He told New Yorkers, the country, and the world that Americans could hear the frustration and anguish of New York, and that the terrorists would soon hear the United States.

Following their speeches, both presidents also received a bump in popularity. Clinton’s approval rating rose from 46 to 51 percent, and Bush’s from 51 to 90 percent. [26]

New Media Trends

The invention of cable in the 1980s and the expansion of the Internet in the 2000s opened up more options for media consumers than ever before. Viewers can watch nearly anything at the click of a button, bypass commercials, and record programs of interest. The resulting saturation, or inundation of information, may lead viewers to abandon the news entirely or become more suspicious and fatigued about politics. [27]

This effect, in turn, also changes the president’s ability to reach out to citizens. For example, viewership of the president’s annual State of the Union address has decreased over the years, from sixty-seven million viewers in 1993 to thirty-two million in 2015. [28]

Citizens who want to watch reality television and movies can easily avoid the news, leaving presidents with no sure way to communicate with the public. [29] Other voices, such as those of talk show hosts and political pundits, now fill the gap.

Electoral candidates have also lost some media ground. In horse-race coverage , modern journalists analyze campaigns and blunders or the overall race, rather than interviewing the candidates or discussing their issue positions. Some argue that this shallow coverage is a result of candidates’ trying to control the journalists by limiting interviews and quotes. In an effort to regain control of the story, journalists begin analyzing campaigns without input from the candidates. [30]

The First Social Media Candidate

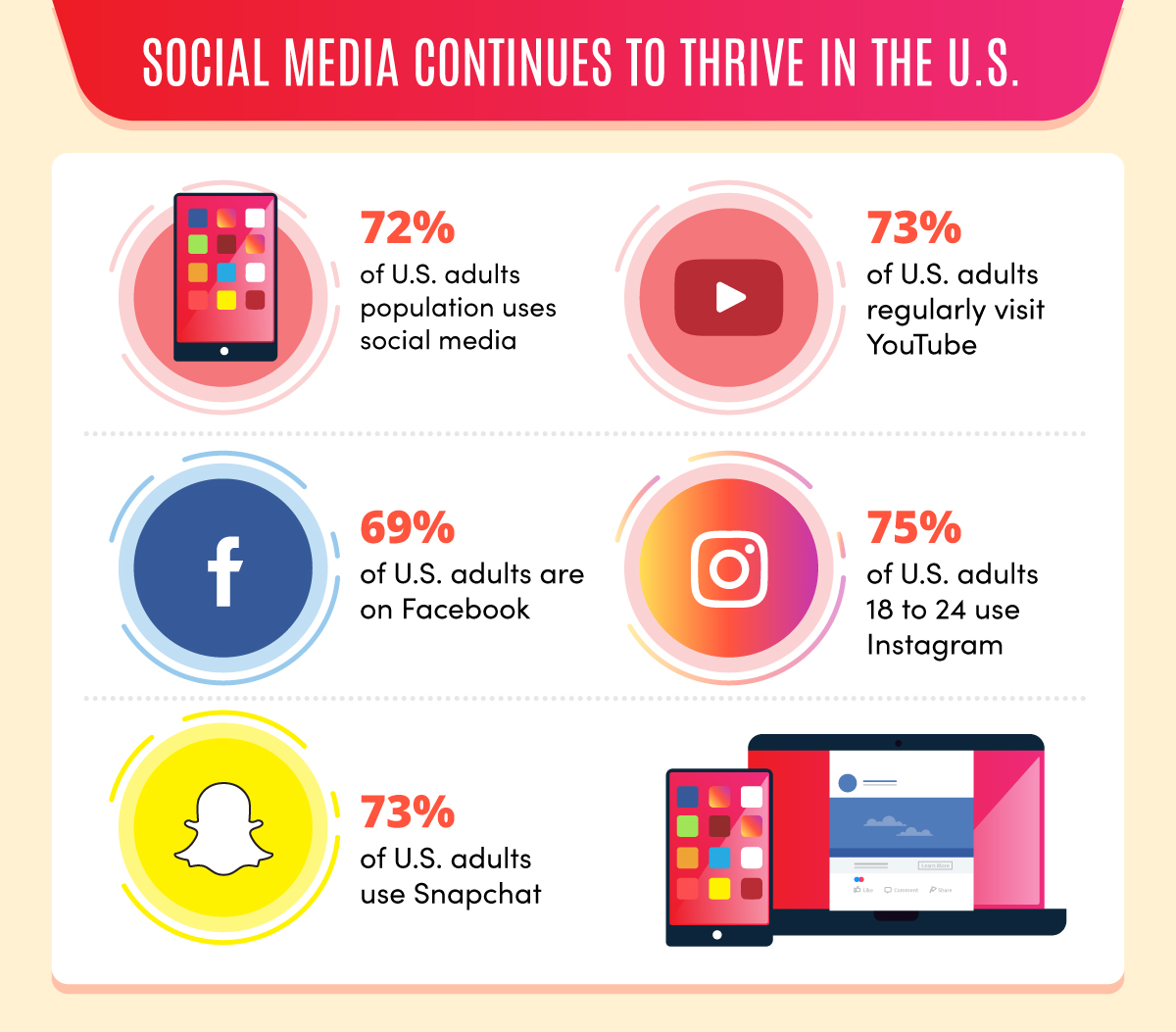

When president-elect Barack Obama admitted an addiction to his Blackberry, the signs were clear: A new generation was assuming the presidency. [31] Obama’s use of technology was a part of life, not a campaign pretense. Perhaps for this reason, he was the first candidate to fully embrace social media.

While John McCain, the 2008 Republican presidential candidate, focused on traditional media to run his campaign, Obama did not. One of Obama’s campaign advisors was Chris Hughes, a cofounder of Facebook. The campaign allowed Hughes to create a powerful online presence for Obama, with sites on YouTube, Facebook, MySpace, and more. Podcasts and videos were available for anyone looking for information about the candidate. These efforts made it possible for information to be forwarded easily between friends and colleagues. It also allowed Obama to connect with a younger generation that was often left out of politics.

By Election Day, Obama’s skill with the web was clear: he had over two million Facebook supporters, while McCain had 600,000. Obama had 112,000 followers on Twitter, and McCain had only 4,600. Matthew Fraser and Soumitra Dutta, “Obama’s win means future elections must be fought online,” Guardian , 7 November 2008.

Are there any disadvantages to a presidential candidate’s use of social media and the Internet for campaign purposes? Why or why not?

The availability of the Internet and social media has moved some control of the message back into the presidents’ and candidates’ hands. Politicians can now connect to the people directly, bypassing journalists. When Barack Obama’s minister, the Reverend Jeremiah Wright, was accused of making inflammatory racial sermons in 2008, Obama used YouTube to respond to charges that he shared Wright’s beliefs. The video drew more than seven million views. [32] To reach out to supporters and voters, the White House maintains a YouTube channel and a Facebook site, as did the recent Republican Speaker of the House of Representatives, John Boehner.

Social media, like Facebook, also placed journalism in the hands of citizens: citizen journalism occurs when citizens use their personal recording devices and cell phones to capture events and post them on the Internet. In 2012, citizen journalists caught both presidential candidates by surprise. Mitt Romney was taped by a bartender’s personal camera saying that 47 percent of Americans would vote for President Obama because they were dependent on the government. [33]

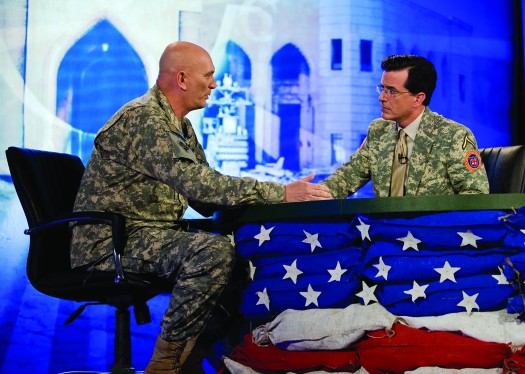

Obama was recorded by a Huffington Post volunteer saying that some Midwesterners “cling to guns or religion or antipathy to people who aren’t like them” due to their frustration with the economy. [34] These statements became nightmares for the campaigns. As journalism continues to scale back and hire fewer professional writers in an effort to control costs, citizen journalism may become the new normal. [35] Another shift in the new media is a change in viewers’ preferred programming. Younger viewers, especially members of generation X and millennials, like their newscasts to be humorous. The popularity of The Daily Show and The Colbert Report demonstrate that news, even political news, can win young viewers if delivered well. [36]

Such soft news presents news in an entertaining and approachable manner, painlessly introducing a variety of topics. While the depth or quality of reporting may be less than ideal, these shows can sound an alarm as needed to raise citizen awareness. [37]

Viewers who watch or listen to programs like John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight are more likely to be aware and observant of political events and foreign policy crises than they would otherwise be. [38] They may view opposing party candidates more favorably because the low-partisan, friendly interview styles allow politicians to relax and be conversational rather than defensive. [39]

Because viewers of political comedy shows watch the news frequently, they may, in fact, be more politically knowledgeable than citizens viewing national news. In two studies researchers interviewed respondents and asked knowledge questions about current events and situations. Viewers of The Daily Show scored more correct answers than viewers of news programming and news stations. [40] That being said, it is not clear whether the number of viewers is large enough to make a big impact on politics, nor do we know whether the learning is long term or short term. [41]

Becoming a Citizen Journalist

Local government and politics need visibility. College students need a voice. Why not become a citizen journalist? City and county governments hold meetings on a regular basis and students rarely attend. Yet issues relevant to students are often discussed at these meetings, like increases in street parking fines, zoning for off-campus housing, and tax incentives for new businesses that employ part-time student labor. Attend some meetings, ask questions, and write about the experience on your Facebook page. Create a blog to organize your reports or use Storify to curate a social media debate. If you prefer videography, create a YouTube channel to document your reports on current events, or Tweet your live video using Periscope or Meerkat.

Not interested in government? Other areas of governance that affect students are the university or college’s Board of Regents meetings. These cover topics like tuition increases, class cuts, and changes to student conduct policies. If your state requires state institutions to open their meetings to the public, consider attending. You might be the one to notify your peers of changes that affect them.

What local meetings could you cover? What issues are important to you and your peers?

Newspapers were vital during the Revolutionary War. Later, in the party press era, party loyalty governed coverage. At the turn of the twentieth century, investigative journalism and muckraking appeared, and newspapers began presenting more professional, unbiased information. The modern print media have fought to stay relevant and cost-efficient, moving online to do so.

Most families had radios by the 1930s, making it an effective way for politicians, especially presidents, to reach out to citizens. While the increased use of television decreased the popularity of radio, talk radio still provides political information. Modern presidents also use television to rally people in times of crisis, although social media and the Internet now offer a more direct way for them to communicate. While serious newscasts still exist, younger viewers prefer soft news as a way to become informed.

Practice Questions

- Why did Franklin D. Roosevelt’s fireside chats help the president enact his policies?

- How have modern presidents used television to reach out to citizens?

- Why is soft news good at reaching out and educating viewers?

[reveal-answer q=”32555″]Show Selected Answer[/reveal-answer] [hidden-answer a=”32555″]

2. The State of the Union address and “rally ’round the flag” speeches help explain policies and offer comfort after crises.

[/hidden-answer]

https://assessments.lumenlearning.co...sessments/1936

[reveal-answer q=”741677″]Show Glossary[/reveal-answer] [hidden-answer a=”741677″]

citizen journalism video and print news posted to the Internet or social media by citizens rather than the news media

digital paywall the need for a paid subscription to access published online material

muckraking news coverage focusing on exposing corrupt business and government practices

party press era period during the 1780s in which newspaper content was biased by political partisanship

soft news news presented in an entertaining style

yellow journalism sensationalized coverage of scandals and human interest stories

- Fellow. American Media History . ↵

- "Population in the Colonial and Continental Periods," http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/00165897ch01.pdf (November 18, 2015); Fellow. American Media History . ↵

- Lars Willnat and David H. Weaver. 2014. The American Journalist in the Digital Age: Key Findings . Bloomington, IN: School of Journalism, Indiana University. ↵

- Michael Barthel. 29 April 2015. "Newspapers: Factsheet," http://www.journalism.org/2015/04/29/newspapers-fact-sheet/ . ↵

- "Facebook and Twitter—New but Limited Parts of the Local News System," Pew Research Center , 5 March 2015. ↵

- "1940 Census," http://www.census.gov/1940census (September 6, 2015). ↵

- Steve Craig. 2009. Out of the Dark: A History of Radio and Rural America . Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ↵

- "Herbert Hoover: Radio Address to the Nation on Unemployment Relief," The American Presidency Project , 18 October 1931, http://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/ws/?pid=22855 . ↵

- "Franklin Delano Roosevelt: First Fireside Chat," http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/fdrfirstfiresidechat.html (August 20, 2015). ↵

- "The Fireside Chats," https://www.history.com/topics/fireside-chats (November 20, 2015); Fellow. American Media History , 256. ↵

- "FDR: A Voice of Hope," http://www.history.com/topics/fireside-chats (September 10, 2015). ↵

- Mary E. Stuckey. 2012. "FDR, the Rhetoric of Vision, and the Creation of a National Synoptic State." Quarterly Journal of Speech 98, No. 3: 297–319. ↵

- Sheila Marikar, "Howard Stern’s Five Most Outrageous Offenses," ABC News, 14 May 2012. ↵

- Lee Huebner, "The Checkers Speech after 60 Years," The Atlantic , 22 September 2012. ↵

- Joel K. Goldstein, "Mondale-Ferraro: Changing History," Huffington Post , 27 March 2011. ↵

- Shanto Iyengar. 2016. Media Politics: A Citizen’s Guide , 3rd ed. New York: W.W. Norton. ↵

- Bob Greene, "When Candidates said ‘No’ to Debates," CNN , 1 October 2012. ↵

- "The Ford/Carter Debates," http://www.pbs.org/newshour/spc/debatingourdestiny/doc1976.html (November 21, 2015); Kayla Webley, "How the Nixon-Kennedy Debate Changed the World," Time , 23 September 2010. ↵

- Matthew A. Baum and Samuel Kernell. 1999. "Has Cable Ended the Golden Age of Presidential Television?" The American Political Science Review 93, No. 1: 99–114. ↵

- Alan J. Lambert1, J. P. Schott1, and Laura Scherer. 2011. "Threat, Politics, and Attitudes toward a Greater Understanding of Rally-’Round-the-Flag Effects," Current Directions in Psychological Science 20, No. 6: 343–348. ↵

- Tim Groeling and Matthew A. Baum. 2008. "Crossing the Water’s Edge: Elite Rhetoric, Media Coverage, and the Rally-Round-the-Flag Phenomenon," Journal of Politics 70, No. 4: 1065–1085. ↵

- "William Jefferson Clinton: Oklahoma Bombing Memorial Prayer Service Address," 23 April 1995, http://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/wjcoklahomabombingspeech.htm . ↵

- Ian Christopher McCaleb, "Bush tours ground zero in lower Manhattan," CNN , 14 September 2001. ↵

- "Presidential Job Approval Center," http://www.gallup.com/poll/124922/presidential-job-approval-center.aspx (August 28, 2015). ↵

- Alison Dagnes. 2010. Politics on Demand: The Effects of 24-hour News on American Politics . Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger. ↵

- "Number of Viewers of the State of the Union Addresses from 1993 to 2015 (in millions)," http://www.statista.com/statistics/252425/state-of-the-union-address-viewer-numbers (August 28, 2015). ↵

- Baum and Kernell, "Has Cable Ended the Golden Age of Presidential Television?" ↵

- Shanto Iyengar. 2011. "The Media Game: New Moves, Old Strategies," The Forum: Press Politics and Political Science 9, No. 1, http://pcl.stanford.edu/research/2011/iyengar-mediagame.pdf . ↵

- Jeff Zeleny, "Lose the BlackBerry? Yes He Can, Maybe," New York Times , 15 November 2008. ↵

- Iyengar, "The Media Game." ↵

- David Corn. 29 July 2013. "Mitt Romeny’s Incredible 47-Percent Denial," http://www.motherjones.com/mojo/2013/07/mitt-romney-47-percent-denial . ↵

- Ed Pilkington, "Obama Angers Midwest Voters with Guns and Religion Remark," Guardian , 14 April 2008. ↵

- Amy Mitchell, "State of the News Media 2015," Pew Research Center , 29 April 2015. ↵

- Tom Huddleston, Jr., "Jon Stewart Just Punched a $250 Million Hole in Viacom’s Value," Fortune , 11 February 2015. ↵

- John Zaller. 2003. "A New Standard of News Quality: Burglar Alarms for the Monitorial Citizen," Political Communication 20, No. 2: 109–130. ↵

- Matthew A. Baum. 2002. "Sex, Lies and War: How Soft News Brings Foreign Policy to the Inattentive Public," American Political Science Review 96, no. 1: 91–109. ↵

- Matthew Baum. 2003. "Soft News and Political Knowledge: Evidence of Absence or Absence of Evidence?" Political Communication 20, No. 2: 173–190. ↵

- "Public Knowledge of Current Affairs Little Changed by News and Information Revolutions," Pew Research Center , 15 April 2007; "What You Know Depends on What You Watch: Current Events Knowledge across Popular News Sources," Fairleigh Dickinson University , 3 May 2012, http://publicmind.fdu.edu/2012/confirmed/ . ↵

- Markus Prior. 2003. "Any Good News in Soft News? The Impact of Soft News Preference on Political Knowledge," Political Communication 20, No. 2: 149–171. ↵

- American Government. Authored by : OpenStax. Provided by : OpenStax; Rice University. Located at : https://cnx.org/contents/[email protected]:Y1CfqFju@5/Preface . License : CC BY: Attribution . License Terms : Download for free at http://cnx.org/contents/9e28f580-0d1...c48329947ac2@1 .

- Share icon. Authored by : Quan Do. Provided by : The Noun Project. Located at : https://thenounproject.com/term/share/7671/ . License : CC BY: Attribution

International Journal of Communication

Founding Editor

- Larry Gross

Founding Managing Editor

- Arlene Luck

- Silvio Waisbord

Managing Editor

- Kady Bell-Garcia

Managing Editor, Special Sections

- Mark Mangoba-Agustin

Editorial Board

- Sean Aday George Washington University

- Omar Al-Ghazzi London School of Economics and Political Science

- Ilhem Allagui Northwestern University-Qatar

- Abeer Al-Najjar American University Of Sharjah

- Meryl Alper Northeastern University

- Adriana Amaral Universidade Paulista

- Hector Amaya University of Southern California

- Melissa Miriam Aronczyk Rutgers University

- Jonathan David Aronson University of Southern California

- Karen Arriaza Ibarra Universidad Complutense de Madrid Spain

- Hanan Badr Paris Lodron University of Salzburg

- Sandra Ball-Rokeach University of Southern California

- Sarah Banet-Weiser University of Pennsylvania/University of Southern California

- Francois Bar University of Southern California

- Emma Baulch Monash University Malaysia

- Yochai Benkler Harvard Law School

- Lance Bennett University of Washington

- TJ Billard Northwestern University

- Bruce Bimber UC Santa Barbara

- Pablo Javier Boczkowski Northwestern University

- Mark Boukes University of Amsterdam

- Nicholas David Bowman Syracuse University

- danah boyd Microsoft Research / Data & Society

- Michael Brüggemann University of Hamburg

- Gustavo Cardoso University of Lisbon

- Manuel Castells

- Lik Sam Chan Chinese University of Hong Kong

- Michael Chan Chinese University of Hong Kong

- Jaeho Cho University of California, Davis

- Lilie Chouliaraki London School of Economics and Political Science

- Renita Coleman University of Texas

- Simon Cottle Cardiff University

- Sasha Costanza-Chock Massachusetts Institute of Technology

- Nick Couldry London School of Economics and Political Science

- Robert T. Craig University of Colorado at Boulder

- Nick Cull University of Southern California

- Afonso de Albuquerque Universidade Federal Fluminense

- Michael X. Delli Carpini University of Pennsylvania

- Claes de Vreese University of Amsterdam

- Marco Deseriis Scuola Normale Superiore

- Alexander Dhoest University of Antwerp

- Susan Douglas University of Michigan

- John D.H. Downing Southern Illinois University

- William Dutton Michigan State University

- Stephen Duncombe New York University

- Richard Dyer University of London

- John Nguyet Erni Hong Kong Baptist University

- Lewis Allen Friedland University of Wisconsin-Madison

- Anthony Y.H. Fung Chinese University of Hong Kong

- Oscar Gandy University of Pennsylvania

- Dilip Gaonkar Northwestern University

- Myria Georgiou London School of Economics and Political Science

- Homero Gil de Zúñiga University of Salamanca Pennsylvania State University

- Ian Glenn University of Cape Town

- Sergio Godoy Universidad Catolica de Chile

- Guy J. Golan Texas Christian University

- Trudy Govier University of Lethbridge

- Mary L. Gray Microsoft Research & Indiana University

- Larry Grossberg University of North Carolina

- Manuel Alejandro Guerrero Universidad Iberoamericana

- Lei Guo Fudan University

- Dan Hallin University of California, San Diego

- James Hamilton Stanford University

- Eszter Hargittai University of Zurich

- John Hartley Curtin University

- Francois Heinderyckx Université Libre de Bruxelles

- Andreas Hepp University of Bremen

- David Hesmondhalgh University of Leeds

- Tom Hollihan University of Southern California

- Yu Hong Zhejiang University

- Kathleen Hall Jamieson University of Pennsylvania

- Henry Jenkins University of Southern California

- Min Jiang University of North Carolina at Charlotte

- Dal Yong Jin Simon Fraser University

- Steve Jones University of Illinois-Chicago

- Douglas Kellner UCLA

- Su Jung Kim University of Southern California

- Marwan M. Kraidy Northwestern University in Qatar

- Josh Kun University of Southern California

- Chin-Chuan Lee National Chengchi University

- Chul-joo Lee Seoul National University

- Francis Lee Chinese University of Hong Kong

- Justin Lewis Cardiff University

- Sonia Livingstone London School of Economics

- Robin Elizabeth Mansell London School of Economics

- Alice E. Marwick University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

- Jorg Matthes University of Vienna

- Robert McChesney University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

- Max McCombs The University of Texas at Austin

- Christine Meltzer Hanover University for Music, Theater and Media

- Kaitlynn Mendes Western University

- Oren Meyers University of Haifa

- Toby Miller Universidad de La Frontera

- Peter R. Monge University of Southern California

- Seungahn Nah University of Florida

- Thomas Nakayama Northeastern University

- Philip Napoli Duke University

- Horace Newcomb University of Georgia

- Zhongdang Pan University of Wisconsin - Madison

- Zizi Papacharissi University of Illinois at Chicago

- Cinzia Padovani Southern Illinois University

- John Durham Peters Yale University

- Victor Pickard University of Pennsylvania

- Alejandro Piscitelli University of Buenos Aires

- Dana Polan New York University

- Marshall Scott Poole University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

- Adam Powell University of Southern California

- Shawn Mathew Powers Georgia State

- Monroe Price University of Pennsylvania

- Jack Linchuan Qiu National University of Singapore

- Janice Radway Northwestern University

- N. Bhaskara Rao Centre for Media Studies, New Delhi

- Michael Renov USC Cinematic Arts

- Allissa V. Richardson University of Southern California

- Eric Rothenbuhler Webster University

- Michael Schudson Columbia University

- Ellen Seiter USC Cinematic Arts

- Brian Semujju Makerere University

- James Shanahan Indiana University

- Limor Shifman Hebrew University of Jerusalem

- Aram Sinnreich American University

- Jonathan Sterne McGill University

- Joseph Straubhaar University of Texas at Austin

- Lukasz Szulc University of Manchester

- John Thompson Cambridge University

- Kjerstin Thorson Michigan State University

- Katrin Tiidenberg Tallinn University

- Florian Toepfl University of Passau

- Yariv Tsfati University of Haifa

- Joseph Turow University of Pennsylvania

- Nikki Usher University of Illinois

- Derek W. Vaillant University of Michigan

- Baldwin Van Gorp Ku Leuven University

- Jorge Vázquez-Herrero Universidade de Santiago de Compostela

- Ingrid Volkmer University of Melbourne

- Jay Wang University of Southern California

- James Webster Northwestern University

- Chris Wells Boston University

- Dmitri Williams University of Southern California

- Angela Xiao Wu New York University

- Guobin Yang University of Pennsylvania

- Dannagal G. Young University of Delaware

- Barbie Zelizer Annenberg/ University of Pennsylvania

- Juyan Zhang University of Texas at San Antonio

- Yuezhi Zhao Simon Fraser University

- Ying Zhu College of Staten Island, CUNY

- For Readers

- For Authors

- For Librarians

PUBLISHED BY:

EDITORIAL STAFF Yvonne Gonzales Sui Wang Josh Widera Assistant Editors

ISSN: 1932-8036

Follow @IJoC_USC

Media Evolution: Emergence, Dominance, Survival and Extinction in the Media Ecology

This article presents an integrated model for understanding the evolution of media, aiming to go beyond the traditional reflections—which tend to reduce media history to a linear succession of technologies—to propose an integrated view of media evolution. Constructing a model of media evolution means going beyond the concepts used up until now—such as Bolter and Grusin’s remediation—to integrate into a single framework analytical categories such as emergence, adaptation, survival, and extinction. In this theoretical context, the article pays particular attention to the simulation processes that occur in the different phases of the evolution of a medium. Finally, a series of critical reflections on the sequential-linear and genealogical-branched evolution models are presented to propose alternatives that represent the complexity of the media ecosystem more closely.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

11.2 The Evolution of the Internet

Learning objectives.

- Define protocol and decentralization as they relate to the early Internet.

- Identify technologies that made the Internet accessible.

- Explain the causes and effects of the dot-com boom and crash.

From its early days as a military-only network to its current status as one of the developed world’s primary sources of information and communication, the Internet has come a long way in a short period of time. Yet there are a few elements that have stayed constant and that provide a coherent thread for examining the origins of the now-pervasive medium. The first is the persistence of the Internet—its Cold War beginnings necessarily influencing its design as a decentralized, indestructible communication network.

The second element is the development of rules of communication for computers that enable the machines to turn raw data into useful information. These rules, or protocols , have been developed through consensus by computer scientists to facilitate and control online communication and have shaped the way the Internet works. Facebook is a simple example of a protocol: Users can easily communicate with one another, but only through acceptance of protocols that include wall posts, comments, and messages. Facebook’s protocols make communication possible and control that communication.

These two elements connect the Internet’s origins to its present-day incarnation. Keeping them in mind as you read will help you comprehend the history of the Internet, from the Cold War to the Facebook era.

The History of the Internet

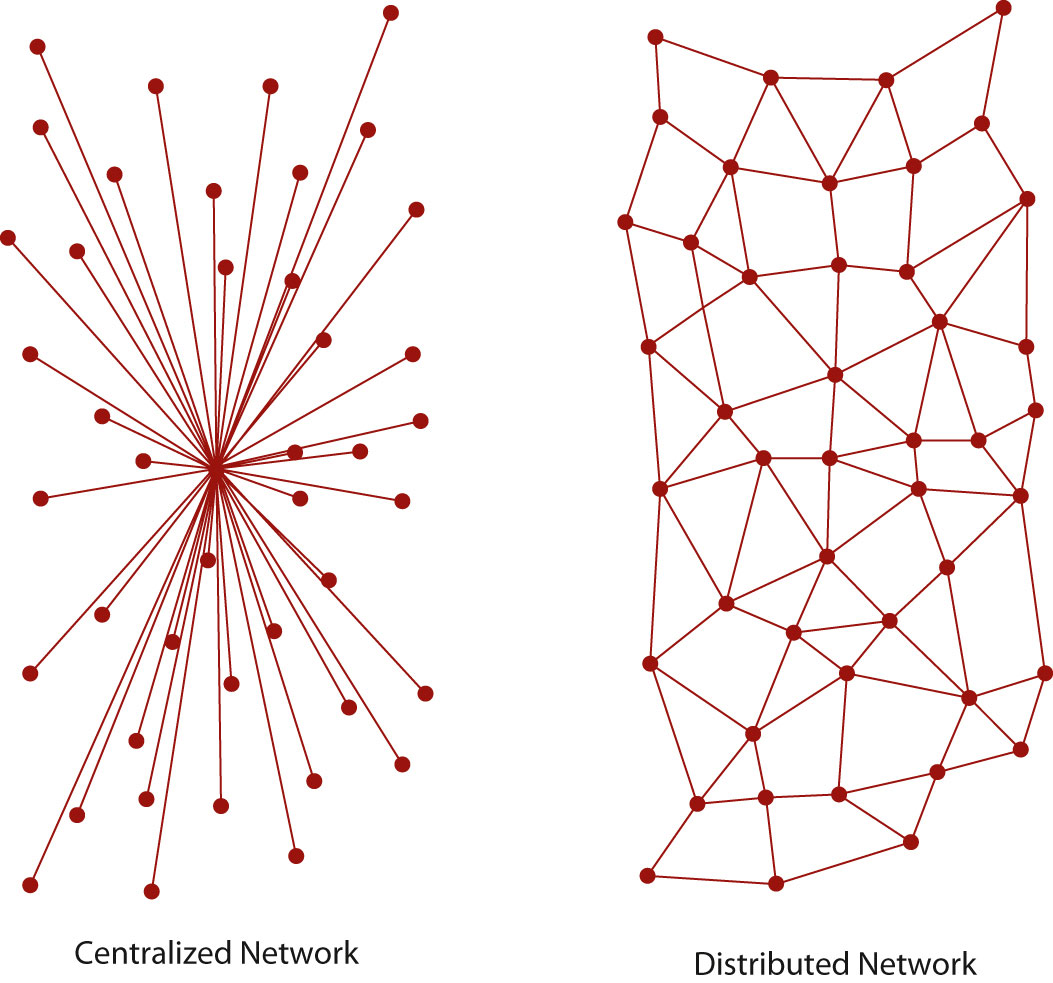

The near indestructibility of information on the Internet derives from a military principle used in secure voice transmission: decentralization . In the early 1970s, the RAND Corporation developed a technology (later called “packet switching”) that allowed users to send secure voice messages. In contrast to a system known as the hub-and-spoke model, where the telephone operator (the “hub”) would patch two people (the “spokes”) through directly, this new system allowed for a voice message to be sent through an entire network, or web, of carrier lines, without the need to travel through a central hub, allowing for many different possible paths to the destination.

During the Cold War, the U.S. military was concerned about a nuclear attack destroying the hub in its hub-and-spoke model; with this new web-like model, a secure voice transmission would be more likely to endure a large-scale attack. A web of data pathways would still be able to transmit secure voice “packets,” even if a few of the nodes—places where the web of connections intersected—were destroyed. Only through the destruction of all the nodes in the web could the data traveling along it be completely wiped out—an unlikely event in the case of a highly decentralized network.

This decentralized network could only function through common communication protocols. Just as we use certain protocols when communicating over a telephone—“hello,” “goodbye,” and “hold on for a minute” are three examples—any sort of machine-to-machine communication must also use protocols. These protocols constitute a shared language enabling computers to understand each other clearly and easily.

The Building Blocks of the Internet

In 1973, the U.S. Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) began research on protocols to allow computers to communicate over a distributed network . This work paralleled work done by the RAND Corporation, particularly in the realm of a web-based network model of communication. Instead of using electronic signals to send an unending stream of ones and zeros over a line (the equivalent of a direct voice connection), DARPA used this new packet-switching technology to send small bundles of data. This way, a message that would have been an unbroken stream of binary data—extremely vulnerable to errors and corruption—could be packaged as only a few hundred numbers.

Figure 11.2

Centralized versus distributed communication networks

Imagine a telephone conversation in which any static in the signal would make the message incomprehensible. Whereas humans can infer meaning from “Meet me [static] the restaurant at 8:30” (we replace the static with the word at ), computers do not necessarily have that logical linguistic capability. To a computer, this constant stream of data is incomplete—or “corrupted,” in technological terminology—and confusing. Considering the susceptibility of electronic communication to noise or other forms of disruption, it would seem like computer-to-computer transmission would be nearly impossible.

However, the packets in this packet-switching technology have something that allows the receiving computer to make sure the packet has arrived uncorrupted. Because of this new technology and the shared protocols that made computer-to-computer transmission possible, a single large message could be broken into many pieces and sent through an entire web of connections, speeding up transmission and making that transmission more secure.

One of the necessary parts of a network is a host. A host is a physical node that is directly connected to the Internet and “directs traffic” by routing packets of data to and from other computers connected to it. In a normal network, a specific computer is usually not directly connected to the Internet; it is connected through a host. A host in this case is identified by an Internet protocol, or IP, address (a concept that is explained in greater detail later). Each unique IP address refers to a single location on the global Internet, but that IP address can serve as a gateway for many different computers. For example, a college campus may have one global IP address for all of its students’ computers, and each student’s computer might then have its own local IP address on the school’s network. This nested structure allows billions of different global hosts, each with any number of computers connected within their internal networks. Think of a campus postal system: All students share the same global address (1000 College Drive, Anywhere, VT 08759, for example), but they each have an internal mailbox within that system.

The early Internet was called ARPANET, after the U.S. Advanced Research Projects Agency (which added “Defense” to its name and became DARPA in 1973), and consisted of just four hosts: UCLA, Stanford, UC Santa Barbara, and the University of Utah. Now there are over half a million hosts, and each of those hosts likely serves thousands of people (Central Intelligence Agency). Each host uses protocols to connect to an ever-growing network of computers. Because of this, the Internet does not exist in any one place in particular; rather, it is the name we give to the huge network of interconnected computers that collectively form the entity that we think of as the Internet. The Internet is not a physical structure; it is the protocols that make this communication possible.

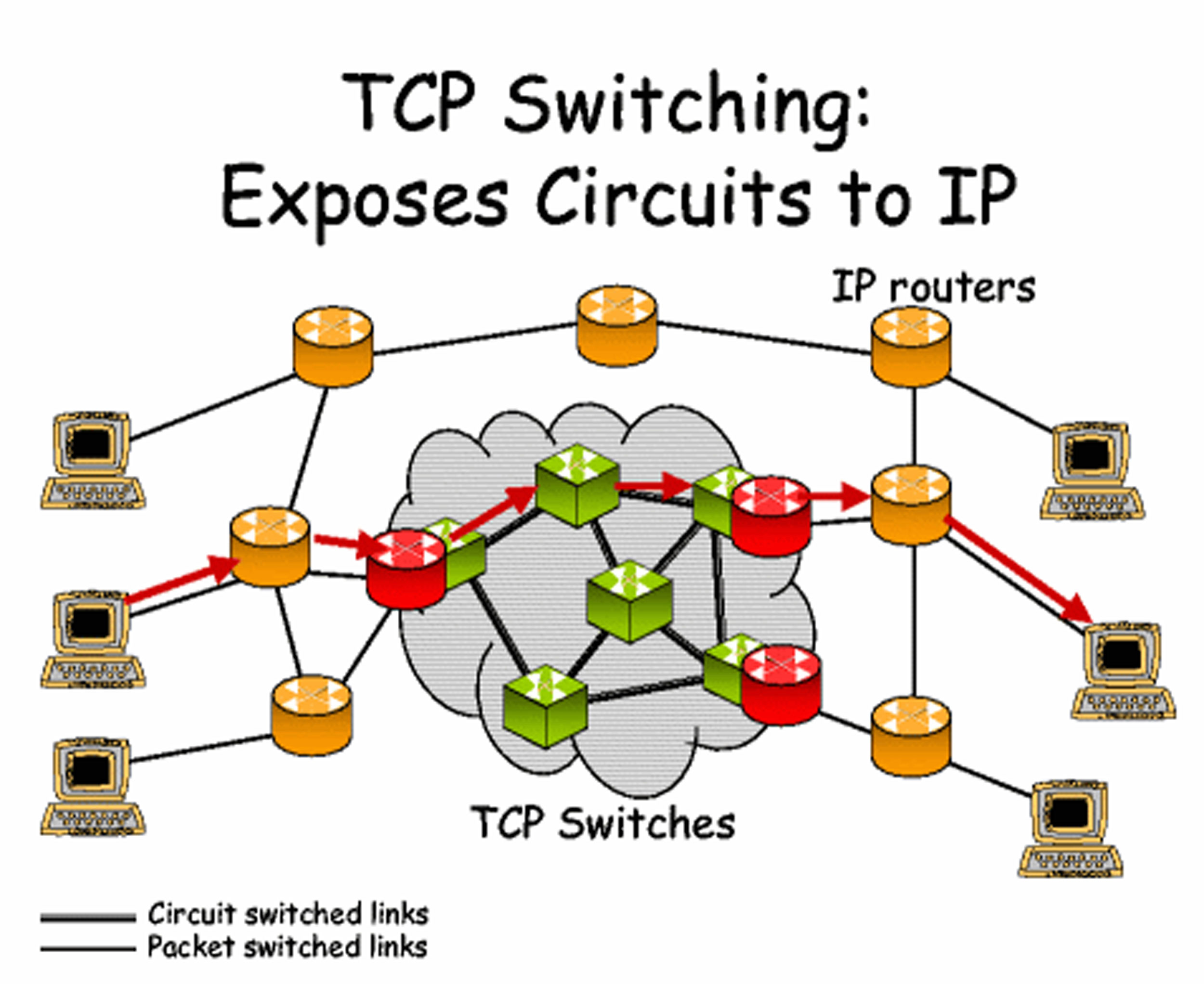

Figure 11.3

A TCP gateway is like a post office because of the way that it directs information to the correct location.

One of the other core components of the Internet is the Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) gateway. Proposed in a 1974 paper, the TCP gateway acts “like a postal service (Cerf, et. al., 1974).” Without knowing a specific physical address, any computer on the network can ask for the owner of any IP address, and the TCP gateway will consult its directory of IP address listings to determine exactly which computer the requester is trying to contact. The development of this technology was an essential building block in the interlinking of networks, as computers could now communicate with each other without knowing the specific address of a recipient; the TCP gateway would figure it all out. In addition, the TCP gateway checks for errors and ensures that data reaches its destination uncorrupted. Today, this combination of TCP gateways and IP addresses is called TCP/IP and is essentially a worldwide phone book for every host on the Internet.

You’ve Got Mail: The Beginnings of the Electronic Mailbox

E-mail has, in one sense or another, been around for quite a while. Originally, electronic messages were recorded within a single mainframe computer system. Each person working on the computer would have a personal folder, so sending that person a message required nothing more than creating a new document in that person’s folder. It was just like leaving a note on someone’s desk (Peter, 2004), so that the person would see it when he or she logged onto the computer.

However, once networks began to develop, things became slightly more complicated. Computer programmer Ray Tomlinson is credited with inventing the naming system we have today, using the @ symbol to denote the server (or host, from the previous section). In other words, [email protected] tells the host “gmail.com” (Google’s e-mail server) to drop the message into the folder belonging to “name.” Tomlinson is credited with writing the first network e-mail using his program SNDMSG in 1971. This invention of a simple standard for e-mail is often cited as one of the most important factors in the rapid spread of the Internet, and is still one of the most widely used Internet services.

The use of e-mail grew in large part because of later commercial developments, especially America Online, that made connecting to e-mail much easier than it had been at its inception. Internet service providers (ISPs) packaged e-mail accounts with Internet access, and almost all web browsers (such as Netscape, discussed later in the section) included a form of e-mail service. In addition to the ISPs, e-mail services like Hotmail and Yahoo! Mail provided free e-mail addresses paid for by small text ads at the bottom of every e-mail message sent. These free “webmail” services soon expanded to comprise a large part of the e-mail services that are available today. Far from the original maximum inbox sizes of a few megabytes, today’s e-mail services, like Google’s Gmail service, generally provide gigabytes of free storage space.

E-mail has revolutionized written communication. The speed and relatively inexpensive nature of e-mail makes it a prime competitor of postal services—including FedEx and UPS—that pride themselves on speed. Communicating via e-mail with someone on the other end of the world is just as quick and inexpensive as communicating with a next-door neighbor. However, the growth of Internet shopping and online companies such as Amazon.com has in many ways made the postal service and shipping companies more prominent—not necessarily for communication, but for delivery and remote business operations.

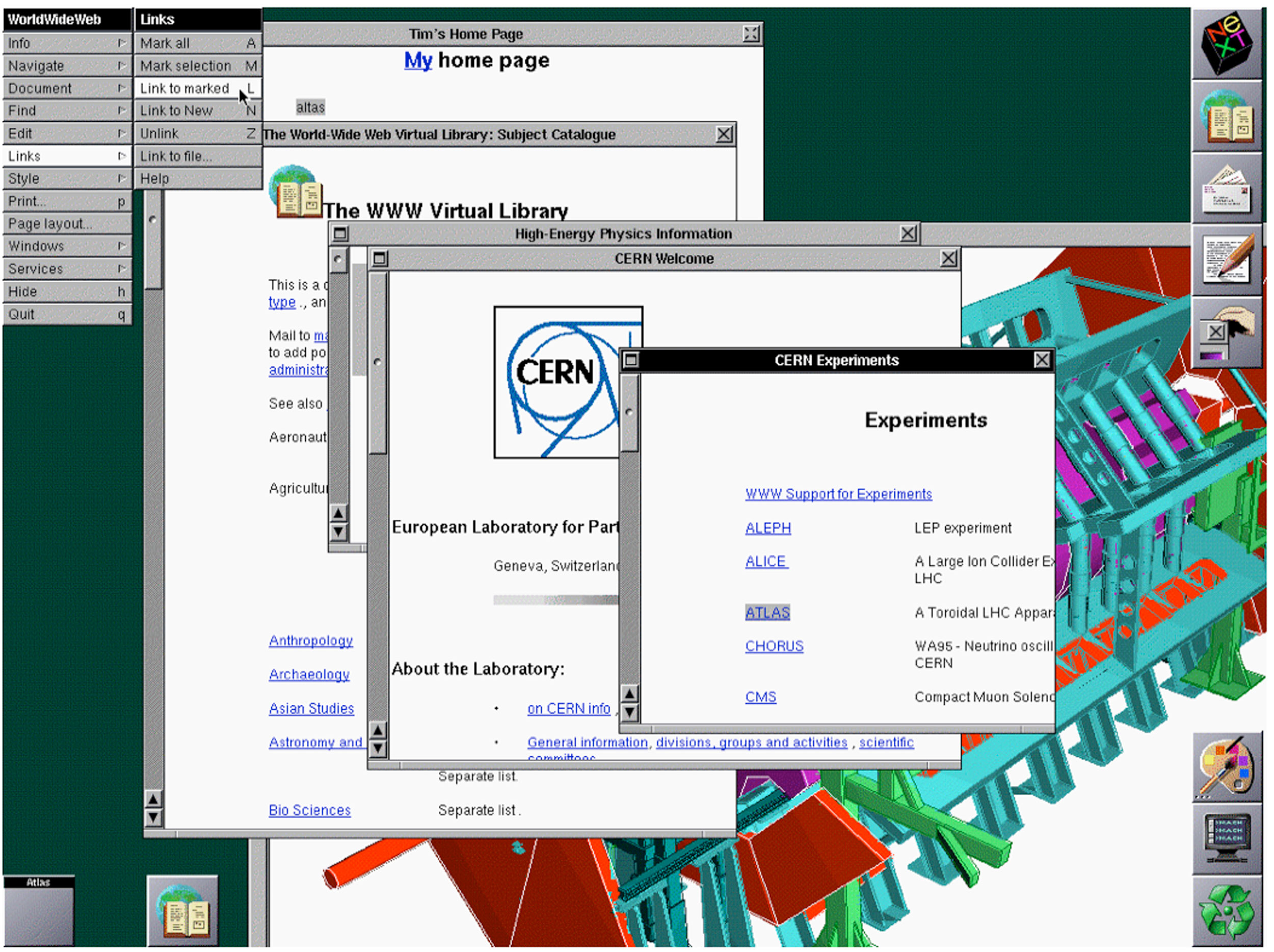

Hypertext: Web 1.0

In 1989, Tim Berners-Lee, a graduate of Oxford University and software engineer at CERN (the European particle physics laboratory), had the idea of using a new kind of protocol to share documents and information throughout the local CERN network. Instead of transferring regular text-based documents, he created a new language called hypertext markup language (HTML). Hypertext was a new word for text that goes beyond the boundaries of a single document. Hypertext can include links to other documents (hyperlinks), text-style formatting, images, and a wide variety of other components. The basic idea is that documents can be constructed out of a variety of links and can be viewed just as if they are on the user’s computer.

This new language required a new communication protocol so that computers could interpret it, and Berners-Lee decided on the name hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP). Through HTTP, hypertext documents can be sent from computer to computer and can then be interpreted by a browser, which turns the HTML files into readable web pages. The browser that Berners-Lee created, called World Wide Web, was a combination browser-editor, allowing users to view other HTML documents and create their own (Berners-Lee, 2009).

Figure 11.4

Tim Berners-Lee’s first web browser was also a web page editor.

Modern browsers, like Microsoft Internet Explorer and Mozilla Firefox, only allow for the viewing of web pages; other increasingly complicated tools are now marketed for creating web pages, although even the most complicated page can be written entirely from a program like Windows Notepad. The reason web pages can be created with the simplest tools is the adoption of certain protocols by the most common browsers. Because Internet Explorer, Firefox, Apple Safari, Google Chrome, and other browsers all interpret the same code in more or less the same way, creating web pages is as simple as learning how to speak the language of these browsers.

In 1991, the same year that Berners-Lee created his web browser, the Internet connection service Q-Link was renamed America Online, or AOL for short. This service would eventually grow to employ over 20,000 people, on the basis of making Internet access available (and, critically, simple) for anyone with a telephone line. Although the web in 1991 was not what it is today, AOL’s software allowed its users to create communities based on just about any subject, and it only required a dial-up modem—a device that connects any computer to the Internet via a telephone line—and the telephone line itself.

In addition, AOL incorporated two technologies—chat rooms and Instant Messenger—into a single program (along with a web browser). Chat rooms allowed many users to type live messages to a “room” full of people, while Instant Messenger allowed two users to communicate privately via text-based messages. The most important aspect of AOL was its encapsulation of all these once-disparate programs into a single user-friendly bundle. Although AOL was later disparaged for customer service issues like its users’ inability to deactivate their service, its role in bringing the Internet to mainstream users was instrumental (Zeller Jr., 2005).

In contrast to AOL’s proprietary services, the World Wide Web had to be viewed through a standalone web browser. The first of these browsers to make its mark was the program Mosaic, released by the National Center for Supercomputing Applications at the University of Illinois. Mosaic was offered for free and grew very quickly in popularity due to features that now seem integral to the web. Things like bookmarks, which allow users to save the location of particular pages without having to remember them, and images, now an integral part of the web, were all inventions that made the web more usable for many people (National Center for Supercomputing Appliances).

Although the web browser Mosaic has not been updated since 1997, developers who worked on it went on to create Netscape Navigator, an extremely popular browser during the 1990s. AOL later bought the Netscape company, and the Navigator browser was discontinued in 2008, largely because Netscape Navigator had lost the market to Microsoft’s Internet Explorer web browser, which came preloaded on Microsoft’s ubiquitous Windows operating system. However, Netscape had long been converting its Navigator software into an open-source program called Mozilla Firefox, which is now the second-most-used web browser on the Internet (detailed in Table 11.1 “Browser Market Share (as of February 2010)” ) (NetMarketshare). Firefox represents about a quarter of the market—not bad, considering its lack of advertising and Microsoft’s natural advantage of packaging Internet Explorer with the majority of personal computers.

Table 11.1 Browser Market Share (as of February 2010)

For Sale: The Web

As web browsers became more available as a less-moderated alternative to AOL’s proprietary service, the web became something like a free-for-all of startup companies. The web of this period, often referred to as Web 1.0, featured many specialty sites that used the Internet’s ability for global, instantaneous communication to create a new type of business. Another name for this free-for-all of the 1990s is the “dot-com boom.” During the boom, it seemed as if almost anyone could build a website and sell it for millions of dollars. However, the “dot-com crash” that occurred later that decade seemed to say otherwise. Quite a few of these Internet startup companies went bankrupt, taking their shareholders down with them. Alan Greenspan, then the chairman of the U.S. Federal Reserve, called this phenomenon “irrational exuberance (Greenspan, 1996),” in large part because investors did not necessarily know how to analyze these particular business plans, and companies that had never turned a profit could be sold for millions. The new business models of the Internet may have done well in the stock market, but they were not necessarily sustainable. In many ways, investors collectively failed to analyze the business prospects of these companies, and once they realized their mistakes (and the companies went bankrupt), much of the recent market growth evaporated. The invention of new technologies can bring with it the belief that old business tenets no longer apply, but this dangerous belief—the “irrational exuberance” Greenspan spoke of—is not necessarily conducive to long-term growth.

Some lucky dot-com businesses formed during the boom survived the crash and are still around today. For example, eBay, with its online auctions, turned what seemed like a dangerous practice (sending money to a stranger you met over the Internet) into a daily occurrence. A less-fortunate company, eToys.com , got off to a promising start—its stock quadrupled on the day it went public in 1999—but then filed for Chapter 11 “The Internet and Social Media” bankruptcy in 2001 (Barnes, 2001).

One of these startups, theGlobe.com , provided one of the earliest social networking services that exploded in popularity. When theGlobe.com went public, its stock shot from a target price of $9 to a close of $63.50 a share (Kawamoto, 1998). The site itself was started in 1995, building its business on advertising. As skepticism about the dot-com boom grew and advertisers became increasingly skittish about the value of online ads, theGlobe.com ceased to be profitable and shut its doors as a social networking site (The Globe, 2009). Although advertising is pervasive on the Internet today, the current model—largely based on the highly targeted Google AdSense service—did not come around until much later. In the earlier dot-com years, the same ad might be shown on thousands of different web pages, whereas now advertising is often specifically targeted to the content of an individual page.

However, that did not spell the end of social networking on the Internet. Social networking had been going on since at least the invention of Usenet in 1979 (detailed later in the chapter), but the recurring problem was always the same: profitability. This model of free access to user-generated content departed from almost anything previously seen in media, and revenue streams would have to be just as radical.

The Early Days of Social Media

The shared, generalized protocols of the Internet have allowed it to be easily adapted and extended into many different facets of our lives. The Internet shapes everything, from our day-to-day routine—the ability to read newspapers from around the world, for example—to the way research and collaboration are conducted. There are three important aspects of communication that the Internet has changed, and these have instigated profound changes in the way we connect with one another socially: the speed of information, the volume of information, and the “democratization” of publishing, or the ability of anyone to publish ideas on the web.