You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser or activate Google Chrome Frame to improve your experience.

Foreign Language Teaching Methods and How to Choose the Best for You

How do you teach your foreign language students?

Consider for a moment the manners in which you teach reading , writing, listening, speaking, grammar and culture . Why do you use those methods?

In my experience, knowing the history of how your subject has been taught will help you understand your teaching methods.

It will also help you learn to select the best ones for your students at any given moment.

Read on for the most common foreign language teaching methods of today, as well as how to choose which ones to employ.

Grammar-translation

Audio-lingual, total physical response, communicative, task-based learning, community language learning, the silent way, functional-notional, other methods, how to choose a foreign language teaching method.

Download: This blog post is available as a convenient and portable PDF that you can take anywhere. Click here to get a copy. (Download)

Those who’ve studied an ancient language like Latin or Sanskrit have likely used this method . It involves learning grammar rules, reading original texts and translating both from and into the target language.

You don’t really learn to speak—although, to be fair, it’s hard to practice speaking languages that have no remaining native speakers.

For the longest time, this approach was also commonly used for teaching modern foreign languages. Though it’s fallen out of favor, there are some benefits to it for occasional use.

With grammar-translation , you might give your students a brief passage in the target language, provide the new vocabulary and give them time to try translating. The reading might include a new verb tense, a new case or a complex grammatical construction.

When it occurs, speaking might only consist of a word or phrase and is typically in the context of completing the exercises. Explanations of the material are in the native language.

After the assignment, you could give students a series of translation sentences or a brief paragraph in the native language for them to translate into the target language as homework.

The direct method , also known as the natural approach, was a response to the grammar-translation method. Here, the emphasis is on the spoken language.

Based on observations of children learning their native tongues, this approach centers on listening and comprehension at the beginning of the language learning process.

Lessons are taught in the target language —in fact, the native language is strictly forbidden. A typical lesson might involve viewing pictures while the teacher repeats the vocabulary words, then listening to recordings of these words used in a comprehensible dialogue.

Once students have had time to listen and absorb the sounds of the target language, speaking is encouraged at all times, especially because grammar instruction isn’t taught explicitly.

Rather, students should learn grammar inductively. Allow them to use the language naturally, then gently correct mistakes and give praise to proper language usage. (Note that many have found this method of grammar instruction insufficient.)

Direct method activities might include pantomiming, word-picture association, question-answer patterns, dialogues and role playing.

The theory behind the audio-lingual approach is that repetition is the mother of all learning. This methodology emphasizes drill work in order to make answers to questions instinctive and automatic.

This approach gives highest priority to the spoken form of the target language. New information is first heard by students; written forms come only after extensive drilling. Classes are generally held in the target language.

An example of an audio-lingual activity is a substitution drill. The instructor might start with a basic sentence, such as “I see the ball.” Then they hold up a series of other photos for students to substitute for the word “ball.” These exercises are drilled into students until they get the pronunciations and rhythm right.

The audio-lingual approach borrows from the behaviorist school of psychology, so languages are taught through a system of reinforcement . Reinforcements are anything that makes students feel good about themselves or the situation—clapping, a sticker, etc.

Full immersion is difficult to achieve in a foreign language classroom—unless, of course, you’re teaching that language in a country where it’s spoken and your students are doing everything in the target language.

For example, ESL students have an immersion experience if they’re studying in an Anglophone country. In addition to studying English, they either work or study other subjects in English for the complete experience.

Attempts at this methodology can be seen in foreign language immersion schools, which are becoming popular in certain districts in the US. The challenge is that, as soon as students leave school, they are once again surrounded by the native language.

One way to get closer to the core of this method is to use an online language immersion program, such as FluentU . The authentic videos are made by and for native speakers and come with a multitude of learning tools.

Try FluentU for FREE!

Expert-vetted, interactive subtitles provide definitions, photo references, example sentences and more. Each lesson contains a quiz personalized to every individual student.

You can also import your own flashcard lists and assign tasks directly to learners with FluentU in order to encourage immersive learning outside of class.

Also known as TPR , this teaching method emphasizes aural comprehension. Gestures and movements play a vital role in this approach.

Children learning their native language hear lots of commands from adults: “Catch the ball,” “Pick up your toy,” “Drink your water.” TPR aims to teach learners a second language in the same manner with as little stress as possible.

The idea is that when students see movement and move themselves, their brains create more neural connections, which makes for more efficient language acquisition.

In a TPR-based classroom, students are therefore trained to respond to simple commands: stand up, sit down, close the door, open your book, etc.

The teacher might demonstrate what “jump” looks like, for example, and then ask students to perform the action themselves. Or, you might simply play Simon Says!

This style can later be expanded to storytelling , where students act out actions from an oral narrative, demonstrating their comprehension of the language.

The communicative approach is the most widely used and accepted approach to classroom-based foreign language teaching today.

It emphasizes the learner’s ability to communicate various functions, such as asking and answering questions, making requests, describing, narrating and comparing.

Task assignment and problem solving —two key components of critical thinking—are the means through which the communicative approach operates.

A communicative classroom includes activities where students can work out a problem or situation through narration or negotiation—composing a dialogue about when and where to eat dinner, for instance, or creating a story based on a series of pictures.

This helps them establish communicative competence and learn vocabulary and grammar in context. Error correction is de-emphasized so students can naturally develop accurate speech through frequent use. Language fluency comes through communicating in the language rather than by analyzing it.

Task-based learning is a refinement of the communicative approach and focuses on the completion of specific tasks through which language is taught and learned.

The purpose is for language learners to use the target language to complete a variety of assignments. They will acquire new structures, forms and vocabulary as they go. Typically, little error correction is provided.

In a task-based learning environment, three- to four-week segments are devoted to a specific topic, such as ecology, security, medicine, religion, youth culture, etc. Students learn about each topic step-by-step with a variety of resources.

Activities are similar to those found in a communicative classroom, but they’re always based around the theme. A unit often culminates in a final project such as a written report or presentation.

In this type of classroom, the teacher serves as a counselor rather than an instructor.

It’s called community language learning because the class learns together as one unit —not by listening to a lecture, but by interacting in the target language.

For instance, students might sit in a circle. You don’t need a set lesson since this approach is learner-led; the students will decide what they want to talk about.

Someone might say, “Hey, why don’t we talk about the weather?” The student will turn to the teacher ( standing outside the circle ) and ask for the translation of this statement. The teacher will provide the translation and ask the student to say it while guiding their pronunciation.

When the pronunciation is correct, the student will repeat the statement to the group. Another student might then say, “I had to wear three layers today!” And the process repeats.

These conversations are always recorded and then transcribed and mined for lesson continuations featuring grammar, vocabulary and subject-related content.

Proponents of this approach believe that teaching too much can sometimes get in the way of learning. It’s argued that students learn best when they discover rather than simply repeat what the teacher says.

By saying as little as possible, you’re encouraging students to do the talking themselves to figure out the language. This is seen as a creative, problem-solving process —an engaging cognitive challenge.

So how does one teach in silence ?

You’ll need to employ plenty of gestures and facial expressions to communicate with your students.

You can also use props. A common prop is Cuisenaire Rods —rods of different colors and lengths. Pick one up and say “rod.” Pick another, point at it and say “rod.” Repeat until students understand that “rod” refers to these objects.

Then, you could pick a green one and say “green rod.” With an economy of words, point to something else green and say, “green.” Repeat until students get that “green” refers to the color.

The functional-notional approach recognizes language as purposeful communication. That is, we use it because we need to communicate something.

Various parts of speech exist because we need them to express functions like informing, persuading, insinuating, agreeing, questioning, requesting, evaluating, etc. We also need to express notions (concepts) such as time, events, action, place, technology, process, emotion, etc.

Teachers using the functional-notional method must evaluate how the students will be using the language .

For example, very young kids need language skills to help them communicate with their parents and friends. Key social phrases like “thank you,” “please” or “may I borrow” are ideal here.

For business professionals, you might want to teach the formal forms of the target language, how to delegate tasks and how to vocally appreciate a job well done. Functions could include asking a question, expressing interest or negotiating a deal. Notions could be prices, quality or quantity.

You can teach grammar and sentence patterns directly, but they’re always subsumed by the purpose for which the language will be used.

A student who wants to learn with the reading method probably never intends to interact with native speakers in the target language.

Perhaps they’re a graduate student who simply needs to read scholarly articles. Maybe they’re a culinary student who only wants to understand the French techniques in her cookbook.

Whoever it is, these students only require one linguistic skill: reading comprehension.

Do away with pronunciation and dialogues. No need to practice listening or speaking, or even much (if any) writing.

With the reading approach, simply help your students build their vocabulary. They’ll likely need a lot of specialized words in a specific field, though they’ll also need to know elements like conjunctions and negation—enough grammar to make it through a standard article in their field.

These approaches are not necessarily as common in the classroom setting but deserve a mention nonetheless:

- Computer Assisted Language Learning (CALL): A number of commercial products ( Pimsleur , Rosetta Stone ) and online products ( Duolingo , Babbel ) use the CALL method. With careful planning, you can likely employ some in the classroom as well.

- Cognitive-code: Developed in response to the audio-lingual method , this approach requires essential language structures to be explicitly laid out in examples (dialogues, readings) by the teacher, with lots of opportunities for students to practice .

- Suggestopedia: The idea here is that the more relaxed and comfortable students feel, the more open they are to learning , which therefore makes language acquisition easier.

Now that you know a number of methodologies and how to use them in the classroom, how do you choose the best?

You should always try to choose the methods and approaches that are most effective for your students. After all, our job as teachers is to help our students to learn in the best way for them— not for us or for researchers or for administrators.

So, the best teachers choose the best methodology and the best approach for each lesson or activity. They aren’t wedded to any particular methodology but rather use principled eclecticism:

- Ever taught a grammatical construction that only appears in written form? Had your students practice it by writing? Then you’ve used the grammar-translation method.

- Ever talked to your students in question/answer form, hoping they’d pick up the grammar point? Then you’ve used the direct method.

- Every repeatedly drilled grammatical endings, or numbers, or months, perhaps before showing them to your students? Then you’ve used the audio-lingual method.

- Ever played Simon Says? Or given your students commands to open their textbook to a certain page? Then you’ve used the total physical response method.

- Ever written a thematic unit on a topic not covered by the textbook, incorporating all four skills and culminating in a final assignment? Then you’ve used task-based learning.

If you’ve already done all of these, then you’re already practicing principled eclecticism!

The point is: The best teachers make use of all possible approaches at the appropriate time, for the appropriate activities and for those students whose learning styles require that approach.

The ultimate goal is to choose the foreign language teaching methods that best fit your students, not to force them to adhere to a particular or method.

Remember: Teaching is always about our students! You got this!

Enter your e-mail address to get your free PDF!

We hate SPAM and promise to keep your email address safe

ESL Speaking

Games + Activities to Try Out Today!

in Activities for Adults · Activities for Kids · ESL Speaking Resources

Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching: CLT, TPR

Teaching a foreign language can be a challenging but rewarding job that opens up entirely new paths of communication to students. It’s beneficial for teachers to have knowledge of the many different language learning techniques including ESL teaching methods so they can be flexible in their instruction methods, adapting them when needed.

Keep on reading for all the details you need to know about the most popular foreign language teaching methods. Some of the ESL pedagogy ideas covered are the communicative approach, total physical response, the direct method, task-based language learning, suggestopedia, grammar-translation, the audio-lingual approach and more.

Language teaching methods

Most Popular Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching

Here’s a helpful rundown of the most common language teaching methods and ESL teaching methods. You may also want to take a look at this: Foreign language teaching philosophies .

#1: The Direct Method

In the direct method ESL, all teaching occurs in the target language, encouraging the learner to think in that language. The learner does not practice translation or use their native language in the classroom. Practitioners of this method believe that learners should experience a second language without any interference from their native tongue.

Instructors do not stress rigid grammar rules but teach it indirectly through induction. This means that learners figure out grammar rules on their own by practicing the language. The goal for students is to develop connections between experience and language. They do this by concentrating on good pronunciation and the development of oral skills.

This method improves understanding, fluency , reading, and listening skills in our students. Standard techniques are question and answer, conversation, reading aloud, writing, and student self-correction for this language learning method. Learn more about this method of foreign language teaching in this video:

#2: Grammar-Translation

With this method, the student learns primarily by translating to and from the target language. Instructors encourage the learner to memorize grammar rules and vocabulary lists. There is little or no focus on speaking and listening. Teachers conduct classes in the student’s native language with this ESL teaching method.

This method’s two primary goals are to progress the learner’s reading ability to understand literature in the second language and promote the learner’s overall intellectual development. Grammar drills are a common approach. Another popular activity is translation exercises that emphasize the form of the writing instead of the content.

Although the grammar-translation approach was one of the most popular language teaching methods in the past, it has significant drawbacks that have caused it to fall out of favour in modern schools . Principally, students often have trouble conversing in the second language because they receive no instruction in oral skills.

#3: Audio-Lingual

The audio-lingual approach encourages students to develop habits that support language learning. Students learn primarily through pattern drills, particularly dialogues, which the teacher uses to help students practice and memorize the language. These dialogues follow standard configurations of communication.

There are four types of dialogues utilized in this method:

- Repetition, in which the student repeats the teacher’s statement exactly

- Inflection, where one of the words appears in a different form from the previous sentence (for example, a word may change from the singular to the plural)

- Replacement, which involves one word being replaced with another while the sentence construction remains the same

- Restatement, where the learner rephrases the teacher’s statement

This technique’s name comes from the order it uses to teach language skills. It starts with listening and speaking, followed by reading and writing, meaning that it emphasizes hearing and speaking the language before experiencing its written form. Because of this, teachers use only the target language in the classroom with this TESOL method.

Many of the current online language learning apps and programs closely follow the audio-lingual language teaching approach. It is a nice option for language learning remotely and/or alone, even though it’s an older ESL teaching method.

#4: Structural Approach

Proponents of the structural approach understand language as a set of grammatical rules that should be learned one at a time in a specific order. It focuses on mastering these structures, building one skill on top of another, instead of memorizing vocabulary. This is similar to how young children learn a new language naturally.

An example of the structural approach is teaching the present tense of a verb, like “to be,” before progressing to more advanced verb tenses, like the present continuous tense that uses “to be” as an auxiliary.

The structural approach teaches all four central language skills: listening, speaking, reading, and writing. It’s a technique that teachers can implement with many other language teaching methods.

Most ESL textbooks take this approach into account. The easier-to-grasp grammatical concepts are taught before the more difficult ones. This is one of the modern language teaching methods.

Most popular methods and approaches and language teaching

#5: Total Physical Response (TPR)

The total physical response method highlights aural comprehension by allowing the learner to respond to basic commands, like “open the door” or “sit down.” It combines language and physical movements for a comprehensive learning experience.

In an ordinary TPR class, the teacher would give verbal commands in the target language with a physical movement. The student would respond by following the command with a physical action of their own. It helps students actively connect meaning to the language and passively recognize the language’s structure.

Many instructors use TPR alongside other methods of language learning. While TPR can help learners of all ages, it is used most often with young students and beginners. It’s a nice option for an English teaching method to use alongside some of the other ones on this list.

An example of a game that could fall under TPR is Simon Says. Or, do the following as a simple review activity. After teaching classroom vocabulary, or prepositions, instruct students to do the following:

- Pick up your pencil.

- Stand behind someone.

- Put your water bottle under your chair.

Are you on your feet all day teaching young learners? Consider picking up some of these teacher shoes .

#6: Communicative Language Teaching (CLT)

These days, CLT is by far one of the most popular approaches and methods in language teaching. Keep reading to find out more about it.

This method stresses interaction and communication to teach a second language effectively. Students participate in everyday situations they are likely to encounter in the target language. For example, learners may practice introductory conversations, offering suggestions, making invitations, complaining, or expressing time or location.

Instructors also incorporate learning topics outside of conventional grammar so that students develop the ability to respond in diverse situations.

- Amazon Kindle Edition

- Bolen, Jackie (Author)

- English (Publication Language)

- 301 Pages - 12/21/2022 (Publication Date)

CLT teachers focus on being facilitators rather than straightforward instructors. Doing so helps students achieve CLT’s primary goal, learning to communicate in the target language instead of emphasizing the mastery of grammar.

Role-play , interviews, group work, and opinion sharing are popular activities practiced in communicative language teaching, along with games like scavenger hunts and information gap exercises that promote student interaction.

Most modern-day ESL teaching textbooks like Four Corners, Smart Choice, or Touchstone are heavy on communicative activities.

#7: Natural Approach

This approach aims to mimic natural language learning with a focus on communication and instruction through exposure. It de-emphasizes formal grammar training. Instead, instructors concentrate on creating a stress-free environment and avoiding forced language production from students.

Teachers also do not explicitly correct student mistakes. The goal is to reduce student anxiety and encourage them to engage with the second language spontaneously.

Classroom procedures commonly used in the natural approach are problem-solving activities, learning games , affective-humanistic tasks that involve the students’ own ideas, and content practices that synthesize various subject matter, like culture.

#8: Task-Based Language Teaching (TBL)

With this method, students complete real-world tasks using their target language. This technique encourages fluency by boosting the learner’s confidence with each task accomplished and reducing direct mistake correction.

Tasks fall under three categories:

- Information gap, or activities that involve the transfer of information from one person, place, or form to another.

- Reasoning gap tasks that ask a student to discover new knowledge from a given set of information using inference, reasoning, perception, and deduction.

- Opinion gap activities, in which students react to a particular situation by expressing their feelings or opinions.

Popular classroom tasks practiced in task-based learning include presentations on an assigned topic and conducting interviews with peers or adults in the target language. Or, having students work together to make a poster and then do a short presentation about a current event. These are just a couple of examples and there are literally thousands of things you can do in the classroom. In terms of ESL pedagogy, this is one of the most popular modern language teaching methods.

It’s considered to be a modern method of teaching English. I personally try to do at least 1-2 task-based projects in all my classes each semester. It’s a nice change of pace from my usually very communicative-focused activities.

One huge advantage of TBL is that students have some degree of freedom to learn the language they want to learn. Also, they can learn some self-reflection and teamwork skills as well.

#9: Suggestopedia Language Learning Method

This approach and method in language teaching was developed in the 1970s by psychotherapist Georgi Lozanov. It is sometimes also known as the positive suggestion method but it later became sometimes known as desuggestopedia.

Apart from using physical surroundings and a good classroom atmosphere to make students feel comfortable, here are some of the main tenants of this second language teaching method:

- Deciphering, where the teacher introduces new grammar and vocabulary.

- Concert sessions, where the teacher reads a text and the students follow along with music in the background. This can be both active and passive.

- Elaboration where students finish what they’ve learned with dramas, songs, or games.

- Introduction in which the teacher introduces new things in a playful manner.

- Production, where students speak and interact without correction or interruption.

TESOL methods and approaches

#10: The Silent Way

The silent way is an interesting ESL teaching method that isn’t that common but it does have some solid footing. After all, the goal in most language classes is to make them as student-centred as possible.

In the Silent Way, the teacher talks as little as possible, with the idea that students learn best when discovering things on their own. Learners are encouraged to be independent and to discover and figure out language on their own.

Instead of talking, the teacher uses gestures and facial expressions to communicate, as well as props, including the famous Cuisenaire Rods. These are rods of different colours and lengths.

Although it’s not practical to teach an entire course using the silent way, it does certainly have some value as a language teaching approach to remind teachers to talk less and get students talking more!

#11: Functional-Notional Approach

This English teaching method first of all recognizes that language is purposeful communication. The reason people talk is that they want to communicate something to someone else.

Parts of speech like nouns and verbs exist to express language functions and notions. People speak to inform, agree, question, persuade, evaluate, and perform various other functions. Language is also used to talk about concepts or notions like time, events, places, etc.

The role of the teacher in this second language teaching method is to evaluate how students will use the language. This will serve as a guide for what should be taught in class. Teaching specific grammar patterns or vocabulary sets does play a role but the purpose for which students need to know these things should always be kept in mind with the functional-notional Approach to English teaching.

#12: The Bilingual Method

The bilingual method uses two languages in the classroom, the mother tongue and the target language. The mother tongue is briefly used for grammar and vocabulary explanations. Then, the rest of the class is conducted in English. Check out this video for some of the pros and cons of this method:

#13: The Test Teach Test Approach (TTT)

This style of language teaching is ideal for directly targeting students’ needs. It’s best for intermediate and advanced learners. Definitely don’t use it for total beginners!

There are three stages:

- A test or task of some kind that requires students to use the target language.

- Explicit teaching or focus on accuracy with controlled practice exercises.

- Another test or task is to see if students have improved in their use of the target language.

Want to give it a try? Find out what you need to know here:

Test Teach Test TTT .

#14: Community Language Learning

In Community Language Learning, the class is considered to be one unit. They learn together. In this style of class, the teacher is not a lecturer but is more of a counsellor or guide.

In general, there is no set lesson for the day. Instead, students decide what they want to talk about. They sit in the a circle, and decide on what they want to talk about. They may ask the teacher for a translation or for advice on pronunciation or how to say something.

The conversations are recorded, and then transcribed. Students and teacher can analyze the grammar and vocabulary, as well as subject related content.

While community language learning may not comprehensively cover the English language, students will be learning what they want to learn. It’s also student-centred to the max. It’s perhaps a nice change of pace from the usual teacher-led classes, but it’s not often seen these days as the only method of teaching a class.M

#15: The Situational Approach

This approach loosely falls under the behaviourism view of language as habit formation. The situational approach to teaching English was popular in England, starting in the 1930s. Find out more about it:

Language Teaching Approaches FAQs

There are a number of common questions that people have about second or foreign language teaching and learning. Here are the answers to some of the most popular ones.

What is language teaching approaches?

A language teaching approach is a way of thinking about teaching and learning. An approach produces methods, which is the way of teaching something, in this case, a second or foreign language using techniques or activities.

What are method and approach?

Method and approach are similar but there are some key differences. An approach is the way of dealing with something while a method involves the process or steps taken to handle the issue or task.

What is presentation practice production?

How many approaches are there in language learning?

Throughout history, there have been just over 30 popular approaches to language learning. However, there are around 10 that are most widely known including task-based learning, the communicative approach, grammar-translation and the audio-lingual approach. These days, the communicative approach is all the rage.

What is the best method of English language teaching?

It’s difficult to choose the best single approach or method for English language teaching as the one used depends on the age and level of the students as well as the material being taught. Most teachers find that a mix of the communicative approach, audio-lingual approach and task-based teaching works well in most cases.

What is micro teaching?

What are the most effective methods of learning a language?

The most effective methods for learning a language really depends on the person, but in general, here are some of the best options: total immersion, the communicative approach, extensive reading, extensive listening, and spaced repetition.

The Modern Methods of Teaching English

There are several modern methods of teaching English that focus on engaging students and making learning more interactive and effective. Some of these methods include:

Communicative Language Teaching (CLT)

This approach emphasizes communication and interaction as the main goals of language learning. It focuses on real-life situations and encourages students to use English in meaningful contexts.

Task-Based Learning (TBL)

TBL involves designing activities or tasks that require students to use English to complete a specific goal or objective. This approach helps students develop language skills while focusing on the task at hand.

Technology-Enhanced Learning

Using technology such as computers, tablets, and smartphones can make learning more engaging and interactive. Online resources, apps, and educational games can be used to supplement traditional teaching methods.

Flipped Classroom

In a flipped classroom, students learn new material at home through videos or online resources, and then use class time for activities, discussions, and practice exercises. This approach allows for more individualized learning and interaction in the classroom.

Project-Based Learning (PBL)

PBL involves students working on projects or tasks that require them to use English in a real-world context. This approach helps students develop critical thinking and problem-solving skills while improving their language abilities.

Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL)

CLIL involves teaching subjects such as science or history in English, rather than teaching English as a separate subject. This approach helps students learn English while also learning about other subjects.

Gamification

Using game elements such as points, badges, and leaderboards can make learning English more fun and engaging. Educational games can help students practice language skills in a playful and interactive way.

These modern methods of teaching English focus on making learning more student-centered, interactive, and engaging, leading to better outcomes for students.

Have your say about Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching

What’s your top pick for a language teaching method? Is it one of the options from this list or do you have another one that you’d like to mention? Leave a comment below and let us know what you think. We’d love to hear from you. And whatever approach or method you use, you’ll want to check out these top 1o tips for new English teachers .

Also, be sure to give this article a share on Facebook, Pinterest, or Twitter. It’ll help other busy teachers, like yourself, find this useful information about approaches and methods in language teaching and learning.

Last update on 2024-04-25 / Affiliate links / Images from Amazon Product Advertising API

About Jackie

Jackie Bolen has been teaching English for more than 15 years to students in South Korea and Canada. She's taught all ages, levels and kinds of TEFL classes. She holds an MA degree, along with the Celta and Delta English teaching certifications.

Jackie is the author of more than 100 books for English teachers and English learners, including 101 ESL Activities for Teenagers and Adults and 1001 English Expressions and Phrases . She loves to share her ESL games, activities, teaching tips, and more with other teachers throughout the world.

You can find her on social media at: YouTube Facebook TikTok Pinterest Instagram

This is wonderful, I have learned a lot!

You’re welcome!

What year did you publish this please?

Recently! Only a few months ago.

Wonderful! Thank you for sharing such useful information. I have learned a lot from them. Thank you!

I am so grateful. Thanks for sharing your kmowledge.

Hi thank you so much for this amazing article. I just wanted to confirm/ask is PPP one of the methods of teaching ESL if so was there a reason it wasn’t included in the article(outdated, not effective etc.?).

PPP is more of a subset of these other ones and not an approach or method in itself.

Good explanation, understandable and clear. Congratulations

That’s good, very short but clear…👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾👏🏾

I meant the naturalistic approach

This is amazing! Thank you for writing this article, it helped me a lot. I hoped this will reach more people so I will definitely recommend this to others.

Thank you, sir! I just used this article in my PPT presentation at my Post Grad School. More articles from you!

I think this useful because it is teaching me a lot about english. Thank you bro! 😀👍

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Our Top-Seller

As an Amazon Associate, I earn from qualifying purchases.

More ESL Activities

Animal Names: Animals that Start with the Letter I

No Prep Games Without Materials for ESL/EFL Teachers

What are Silent Letter Words and Common Examples

B Adjectives List | Describing Words that Start with B

About, contact, privacy policy.

Jackie Bolen has been talking ESL speaking since 2014 and the goal is to bring you the best recommendations for English conversation games, activities, lesson plans and more. It’s your go-to source for everything TEFL!

About and Contact for ESL Speaking .

Privacy Policy and Terms of Use .

Email: [email protected]

Address: 2436 Kelly Ave, Port Coquitlam, Canada

Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Contemporary Education, Social Sciences and Humanities (ICCESSH 2019)

Exploration and Research on Oral Presentation in Classroom Teaching in Foreign Language Teaching

The oral presentation teaching mode introduced from the West has been widely used in foreign language teaching in universities of China. This student-centered teaching method can greatly mobilize students' learning enthusiasm, exercise foreign language comprehensive level, improve their speaking ability, and enhance the feelings between teachers and students at the same time. However, due to many factors, oral presentation in the classroom often cannot effectively play its role in practice. On the basis of years of research and practice, the author puts forward four suggestions for improving the effectiveness of oral presentation in the classroom: firstly, the goal should be clear, and the topic should be combined with the content of the class; secondly, the group cooperation display that is reasonably divided can mobilize the enthusiasm of the students. And through the group assessment method, it helps to improve the overall foreign language level of the whole class; in addition, the teacher's guidance and evaluation level is directly related to the quality and effect of the display; finally, peer assessment is used to guide the whole class to actively participate and achieve common progress.

Download article (PDF)

Cite this article

- Getting Started

- Introduction

- The Teacher

- The Learner

Foreign Language Teaching Methods: Introduction

- Meet the Class

An Online Methods Course for Foreign Language Teachers

This professional development resource focuses on practical aspects of foreign language teaching in a virtual classroom setting. You, the foreign language teacher, will be transported into a real-life methods course to watch and listen to instructors at the University of Texas at Austin and think critically about the ensuing classroom discussions.

Foreign language teachers learn:

- best practices for instruction that can be applied to any language,

- practical design for activities and lesson plans that can be adapted for any language classroom,

- analysis of classroom materials and classroom interactions, and

- opportunities to learn by observing the development of actual foreign language teachers.

In this introduction, you will meet the course instructors and beginning teachers, and learn about the components and features of this online resource.

Tell us what you think and help us improve this page.

Send a comment

Name (optional)

Email (optional)

Comment or Message

CC BY-NC-SA 2010 | COERLL | UT Austin | Copyright & Legal | Help | Credits | Contact

CC BY-NC-SA | 2010 | COERLL | UT Austin | http://coerll.utexas.edu/methods

The Oral Approach and Situational Language Teaching

Published by awalls86 on january 29, 2021 january 29, 2021.

This is post 4 of 6 in the series “Methods and Approaches”

- Grammar Translation Method

- The Series Method

The Direct Method

The audiolingual method, total physical response.

Join my telegram channel for teachers.

The biggest criticism of the direct method was the lack of any educational principles to underpin it. The oral approach, or situational language teaching as it came to be known, was therefore an attempt to base a teaching approach on clear principles.

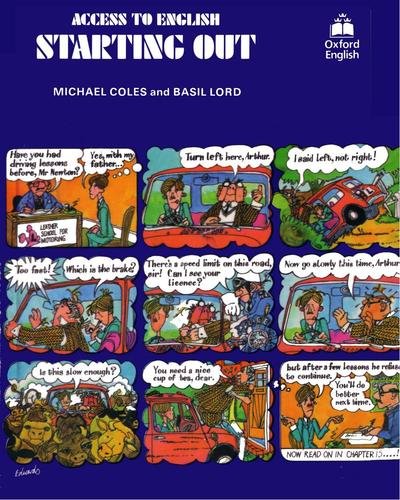

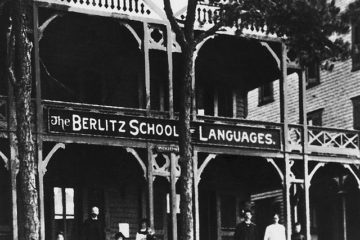

The principles for this approach were developed between the 1930s and 1960s by British linguists including A.S. Hornby, Harold Palmer and Michael West. Despite being developed some 60 years ago, this approach was nevertheless the basis of many course books in the 1970s and 1980s, and may still be in use even today in some parts of the world (Richards and Rogers, 2014). Well-known course book series which use situational language teaching include Streamline (Hartley and Viney), Access to English (Coles and Lord) and Kernel Lessons Plus (O’Neill).

Beliefs About Language

Speaking and listening.

As the name “the Oral Approach” suggests, one of the key beliefs was that speaking and listening are more important than reading and writing. As a result, language would always be presented and practised orally first, with reading and writing only coming towards the end of a lesson and only when it was felt students were ready.

This point was to come once students had a sufficient grasp of the lexis and grammar structures. These structures, along with content words, formed the basis of a syllabus for the situational basis, being selected for their frequency, graded by complexity and organised around “situations”.

Michael West was one proponent for focusing more on vocabulary due to his experience teaching Indian students to improve their reading proficiency. In this time, he was involved in a study noting the frequency of words across texts. This led to the publication of the Interim Report on Vocabulary Selection for the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language in 1936 and the revised 1953 a General Service List of English Words .

According to West (1954), some 2.5 to 5 million words were counted in preparing these lists. Considering that such a task would now be accomplished in seconds by a corpus, it may be difficult for some to imagine the time this would have taken back in the 1950s! The goal was to aid teachers in defining a minimum adequate vocabulary their students would need. Interestingly, West (ibid) notes that this minimum adequate vocabulary may depend upon the students’ circumstances and therefore the general service list should be viewed as no more than a guide.

In addition to lexis, grammar was still considered necessary to be taught. Palmer (Richards & Rogers 2014) viewed grammar as the underlying patterns of conversation. This marks a deviation from the view, or perhaps unquestioned acceptance, that the grammar of speech is the same as that of written English.

Palmer, Hornby and other linguists analysed English and drew up substitution tables to help students internalise these patterns. Palmer & Redman (1969) compared these to using railway schedules to figure out your route. In their analogy, the routes more often travelled are more easily remembered and therefore no longer require the substitution tables.

Based on these substitution tables and the analysis of these patterns, the first dictionary for English students was published in 1948 (The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English).

Beliefs About Learning

As briefly mentioned above, one of the features of the situational approach is the organisation of structures into a syllabus. These were graded in order that students encounter simpler structures before more complex ones. A further important point on the syllabus however is the organisation of language into situations.

According to Richards and Rogers (2014), situation was intended here to mean the use of concrete objects, pictures, realia, gestures and actions to demonstrate meaning. In the course book Access to English (Coles & Lord, 1975) mentioned earlier, you can see the use of situations through a dialogue and series of pictures relating to it. As with the direct method then, vocabulary and structures were to be learned inductively without explanation or L1 translation. L1 was still not allowed in the classroom.

Lesson Structure

The situational or oral approach understood learning a language to be habit formation, and therefore relied upon behaviourist principles. Essentially, this involves language being received, fixed in memory and practised.

One of the common methods to practise new structures and lexis was therefore drilling, which was believed to help both memorisation and habit formation. In order for correct habits to form, it was believed errors needed to be avoided at all costs, and thus a focus on accuracy remained.

Since the main practice activity was drilling, lessons in a situational approach are largely teacher-led. Students typically listen to the teacher, repeat and may in some cases respond to commands or questions.

A typical situational lesson may therefore be organised as such:

- pronunciation

- revision of previous structures

- presentation of new structures and lexis

- reading or writing exercises

Oral / Situational Principles

The principles of the oral approach or situational language teaching can therefore be summarised as:

- Speaking and listening were considered of primary importance.

- Building up a minimum adequate vocabulary was necessary before tackling reading and writing.

- Grammar should be based on spoken language and taught as patterns.

- New language should be sequenced by complexity and learned inductively in situations.

- Learning a language is habit formation and therefore drilling is helpful.

- L1 should not be used in lessons.

- Mistakes should be avoided at all costs.

Criticisms of Situational Language Teaching

The main criticism of situational language teaching comes from Chomsky’s refutation of structuralist and behaviourist theories of language learning. Learning a language is not simply habit formation, and this is clearly evidenced by the fact that any person can build completely novel sentences despite having never heard that sentence before.

While this is the main criticism, it is not the only criticism of situational language teaching:

- The delay of dealing with reading and writing may not suit all students. Some may need these skills more than the ability to speak or listen in the language.

- Not all language can be suitably demonstrated in clear situations. This language is likely to neglected.

- The approach requires a fluent and confident teacher.

- Teacher-centred lessons may become boring for students very quickly.

Established as an approach by the 1960s, situational language teaching was soon called into question by communicative language teaching. That didn’t stop it being practised until at least the beginning of the 21st Century in some contexts.

Some of the features of the situational approach have not gone away and can be seen in the PPP model that is taught on CELTA courses.

Key Takeaways

The Oral Approach or Situational Language Teaching was an approach in Britain that attempted to base language learning on principles.

Speaking and listening were considered of paramount importance. Reading and writing were considered less important.

Vocabulary took on a greater role as students tried to learn a minimum adequate vocabulary.

Grammar was taught inductively as patterns using situations.

Delivery of lessons was based on behaviourist principles which are now criticised.

Coles, M. & Lord, B. (1975) Access to English: Getting On . Oxford University Press.

Faucett, L., Palmer, H., Thorndike, E. & West, M. (1953). Interim Report on Vocabulary Selection for the Teaching of English as a Foreign Language . P.S. King & Son Ltd.

Hartley, B. & Viney, P. (1994). New American Streamline Departures . Oxford University Press.

Hornby, A., Cowie, A. & Windsor Lewis, J. (1948). The Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary of Current English . Oxford University Press.

O’Neill, R. (1974). Kernel Lessons – Plus: Laboratory Drills and Tapescript . Longman.

Palmer, H. & Redman, H. (1969). This Language-Learning Business . Oxford University Press.

Richards, J. & Rodgers, T. (2014). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching . Cambridge University Press.

West, M. (1953). A General Service List of English Words . Longman.

West, M. (1954). Vocabulary Selection and the Minimum Adequate Vocabulary . ELT Journal 8(4), Summer 1954.

Related Posts

Methodology.

This is post 6 of 6 in the series “Methods and Approaches” Grammar Translation Method The Series Method The Direct Method The Oral Approach and Situational Language Teaching The Audiolingual Method Total Physical Response Total Read more…

This is post 5 of 6 in the series “Methods and Approaches” Grammar Translation Method The Series Method The Direct Method The Oral Approach and Situational Language Teaching The Audiolingual Method Total Physical Response The Read more…

This is post 3 of 6 in the series “Methods and Approaches” Grammar Translation Method The Series Method The Direct Method The Oral Approach and Situational Language Teaching The Audiolingual Method Total Physical Response The Read more…

Promoting Oral Presentation Skills Through Drama-Based Tasks with an Authentic Audience: A Longitudinal Study

- Regular Article

- Open access

- Published: 15 March 2021

- Volume 31 , pages 253–267, ( 2022 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Yow-jyy Joyce Lee ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-7786-446X 1 &

- Yeu-Ting Liu ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-8055-0587 2

10k Accesses

4 Citations

Explore all metrics

Drama activities are reported to foster language learning, and may prepare learners for oral skills that mirror those used in real life. This year-long time series classroom-based quasi-experimental study followed a between-subjects design in which two classes of college EFL learners were exposed to two oral training conditions: (1) an experimental one in which drama-based training pedagogy was employed; and (2) the comparison one in which ordinary public speaking pedagogy was utilized. The experimental participants dramatized a picture book into a play, refined and rehearsed it for the classroom audience, and eventually performed it publicly as a theater production for community children. Diachronic comparisons of the participants’ oral presentation skills under the two conditions showed that a significant between-group difference began to become pronounced only after the experimental participants started to present for real-life audiences other than their classmates. This finding suggests that drama-mediated pedagogy effectively enhanced the experimental participants’ presentation performance and became more effective than the traditional approach only after a real-life audience was involved. In addition to the participants’ performance data, survey and retrospective protocols were utilized to shed light on how drama-based tasks targeting both classroom and authentic audiences influence college EFL learners’ presentation performance and their self-perceived oral presentation skills. Analysis of the survey and retrospective data indicated that the participants’ attention to three presentation skills—structure, audience adaptation and content—was significantly raised after their presentation involved a real-life audience. Based on these findings, pedagogical implications for drama for FL oral presentation instruction are discussed.

Similar content being viewed by others

Dialogues across time and space in a video-based collaborative learning environment

Not quite eye to A.I.: student and teacher perspectives on the use of generative artificial intelligence in the writing process

Impact of ChatGPT on ESL students’ academic writing skills: a mixed methods intervention study

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

This study explores drama-based activities as a vehicle for real-world situations to train foreign language (FL) oral presentation skills in tertiary education. One of the most effective ways of learning a target language is to apply it in a real-life context. It has been repeatedly proven that students acquire a foreign language best when they have a real purpose for learning, and when their use of language is meaningful and authentic (Chamot, 2009 ; Enright et al., 1988 ; Long, 2015 ). In the case of oral performance, however, while practicing their oral skills, FL learners in the classroom tend to target their presentation assignment on their peers and the teacher, and the presentations generated under such circumstances are often shaped by a restricted array of purposes and audience, and confined to the classroom-based activities and cohort. This issue speaks to the need to design effective authentic tasks that can better prepare FL learners for real-world oral communication.

So, how do language instructors and scholars perceive the concept of authenticity? According to Celce-Murcia ( 2008 ), communicative value is a telling sign of authenticity. Authenticity in the language education literature is often discussed in terms of three aspects: authenticity in language, task and situation (Beatty, 2015 ; Breen, 1985 ). Unfortunately, due to the demands of test-driven curricula, authenticity is often not inherent in the language pedagogy in many second language (L2) and FL classrooms (Widdowson, 1990 ). In line with this trend, many teaching and practice tasks in the classroom focus mainly on pedagogical or remedial activities that aim to prepare students for tests rather than on tasks that genuinely engage students with real-world language, tasks and situations that are rich in communicative characteristics, such as purposefulness, reciprocity, synchronicity, and unpredictability (Beatty, 2015 ; Thornbury, 2010 ; see also Widdowson, 1990 ). Consequently, in many FL classrooms, authenticity in language, task, and situation becomes a challenge because the pedagogical context of the language classroom makes what goes on inherently inauthentic, and the pedagogy in the language classroom lacks the genuine communicative value found in the real-world context (Beatty, 2015 ). The benefit of using drama and theater production with a real-life audience is mainly investigated and established in the domain of writing; studies have shown that the inclusion of an online audience prompted foreign and second language learners to develop an enhanced audience awareness (Hung, 2011 ; Warschauer, 1999 ), improve their writing outputs (Pilkington et al., 2000 ), and become more confident in their writing abilities (Choi, 2008 ; Phinney, 1991 ).

Despite the positive evidence from these studies, whether similar benefits also hold true in the domain of public oral presentation skills—a deliberate act of presenting a topic to a live audience to influence, educate, communicate, or entertain—is yet to be investigated. Spanning two academic semesters, this longitudinal study set out to explore the diachronic impacts that drama-based tasks may have on college students’ oral presentation outcomes and on their perceptions of their presentation skills.

Literature Review

Using drama/theater as an effective means of promoting oral skills.

Drama provides an authentic arena for real language use in real situations with an emphasis on reciprocal, synchronized, unpredictable audience interactions (Beatty, 2015 ; Thornbury, 2010 ; see also Widdowson, 1990 ). First-language (L1) research has shown that drama has the pedagogical potency to enhance listening comprehension (Thompson & Rubin, 1996 ), reinforce the tie between thought and expression in writing (Dunn et al., 2013 ), offer paralanguage and suprasegmental cues to enhance speaking skills (Di Pietro, 1987 ; Kao & O’Neill, 1998 ; Miccoli, 2003 ; Whiteson, 1996 ), strengthen reading comprehension (Cornett, 2003 ), and even facilitate vocabulary acquisition (Rose, 1987 ). Among these benefits, drama is particularly conducive to the development of various oral skills (Whiteson, 1996 ). To make a strong case for this view, Podlozny ( 2000 ) conducted an extensive meta-analysis of 80 studies published since 1950 which investigated the impact of drama on oral language outcomes. This meta-analysis shows that classroom drama significantly facilitated oral language development.

In the realm of FL and L2 research, Kao et al. ( 2011 ) reported that in the process of building the drama context, FL learners had the chance to critically evaluate and practice their listening and speaking skills; they claimed that drama is a tool with the potential to engage English FL learners and promote their oral proficiency (see also Hwang et al., 2016 ). Recently, Zhang et al. ( 2019 ) found that the interactions among peers in the form of collaboration and discussion during a drama-based learning process significantly promoted young English-as-a-foreign-language (EFL) learners’ storytelling skills.

The examples above illustrate that dramatic activities, if well-designed and well-handled, can significantly enhance various oral skills. Note, however, that not all studies have yielded unequivocal, positive evidence supporting this view. According to Lee et al.’s ( 2015 ) meta-analysis of 47 drama-based pedagogy (DBP) research studies, the mixed findings among existing studies may be attributed to the duration of drama-based language teaching/learning. Lee et al. thus posited that a “more positive effect [arising from DBP] will result when students experience [drama-based] interventions that include frequent…sessions that occur over [a] longer period compared [with] sessions [that are] infrequent or the intervention as a whole is brief” (Lee et al., 2015 , pp. 11–12). Specifically, while reviewing relevant works on drama-based language learning, Lee et al. observed that larger effect sizes and stronger effects were typically associated with studies “that span 12 weeks to a year or more” (Lee et al., 2015 , p. 38; see also Conard, 1992 for a similar view). However, many such studies are short-term projects, which usually span from 3 to 6 weeks (e.g., Hwang et al., 2016 ; Kao et al., 2011 ; Zhang et al., 2019 ). The above finding entails that oral presentation skills, which take time to develop, are more likely to be captured in longitudinal studies, and that the effects of drama-based language teaching on oratory or public speaking skills may be more manifest in long-term treatment that lasts at least 12 weeks. Hitherto, there has been a scarcity of longitudinal studies in drama-based language pedagogy (Stinson & Winston, 2011 ).

Furthermore, the relevant studies have focused predominantly on elementary school children (Andresen, 2005 ; Kelner, 2002 ; Mages, 2008 ; McCaslin, 1990 ). More studies that involve older, cognitively mature FL learners (such as teenagers and college students) are needed to gain further insights into the effects of drama-based activities on FL learners’ oral presentation skills. The current research is designed to investigate the longitudinal impacts of drama-based tasks on college EFL learners’ oral presentation skills.

The Importance of Involving a Real-Life Audience Beyond the Classroom Setting

More than 2 decades ago, drama and theater scholars began to stress the importance of involving authentic audiences beyond the classroom walls. For instance, Brook ( 1996 ) claimed that the existence of a live audience in an act of theater may be all that is needed to “see the varying lengths of attention [an actor] could command” (p. 52). Etchells commented that actors and an audience are two irreducible facts of theater (Etchells, 1999 ). However, empirical validation of the above stipulation has only started to accumulate during the past decade, mostly in the realm of L2 writing. L2 writing studies have revealed that the inclusion of (online) audiences outside the classroom walls prompts English as a foreign language (EFL) learners to develop an enhanced audience awareness (Hung, 2011 ; Warschauer, 1999 ), improve their writing outputs (Chen & Brown, 2012 ; Lin et al., 2014 ; Pilkington et al., 2000 ; Wang, 2015 ), enhance their motivation (Chen & Brown, 2012 ; Lin et al., 2016 ) and develop confidence in their writing abilities (Choi, 2008 ; Phinney, 1991 ).

Among the aforementioned studies, Chen and Brown’s ( 2012 ) study is a case in point. In their canonical study, six L2 learners were asked to complete three writing tasks for a specific, authentic audience, using two internet-based applications ( Wikispaces and Weekbly ). Analysis of these learners’ interview data revealed that they were all highly motivated to learn, and had significantly positive perceptions of their progress; notably, they were all driven to improve their sentence precision and complexity, and to enlarge their vocabulary knowledge. Nevertheless, the generalizability of Chen and Brown’s study was constrained due to the small sample size, and a strong case about the imperative role of an authentic audience cannot be made because of the lack of a comparison or control group. The above issues were later addressed by Lin et al. ( 2014 ) in whose study learners were exposed to two writing conditions: (1) the experimental condition: learners wrote daily blogs for an authentic audience; and (2) the comparison condition: learners wrote their journals in their notebooks using pen and paper (without an authentic audience). Diachronic cross-group comparisons indicated that although the two groups did not differ significantly in their attitudes, the experimental participants exhibited a greater improvement over time, and experienced less anxiety. This finding was later replicated in Wang’s ( 2015 ) and Lin et al.’s ( 2016 ) studies which introduced L2 learners to authentic audiences using the University Teacher-Student Blog (TSB) freely offered to them, and Facebook, respectively. Online audiences beyond the classroom setting also exert a positive influence on students’ communicative competence shown in video-based artifacts (Hafner & Miller, 2011 ; Yeh, 2018 ).

Despite the positive evidence supporting the pivotal role of an authentic audience in promoting L2 writing, this issue has not been examined in the context of L2 speaking where learners face qualitatively different challenges (e.g., having time pressure and requiring different parsing strategies) in planning and production. In spite of the absence of empirical evidence in L2 speaking, Casteleyn ( 2019 ) stipulated the pivotal role of involving a real audience in promoting L2 oral skills. According to Casteleyn’s recent study (Casteleyn, 2019 ) on theater performance, drama and theater play can effectively help language learners “live the experience” and promote their oral presentation skills in real life due to the following three features:

Systematic desensitization: Casteleyn believes that regularly conducted activities (i.e., drama/theater training and performance) have the potency to desensitize students’ speaking anxiety by allowing them to constantly explore and experience the target language in various meaningful, realistic contexts (Purcell-Gates et al., 2002 )

Skills training: Casteleyn contends that activities such as drama/theater share numerous elements (voice, face, body language, structure, script content, audience, etc.) that are parallel to the communicative activities in real life. Thus, drama/theater practice and performance can effectively prepare students to develop the oratory skills required for meaningful communicative activities beyond the classroom setting

Cognitive modification: Casteleyn posits that drama and theater productions provide students with opportunities to connect to a real-life audience other than their classmates. Performing drama for an audience beyond the classroom setting is a useful way of fostering students’ incentive to practice/perform, and hence to develop a positive mindset for public speaking and performance beyond the classroom setting

Casteleyn’s ( 2019 ) view regarding systematic desensitization and skills training is familiar to many FL or L2 teachers who employ drama in their classrooms, especially those proponents of task-based language teaching (TBLT) (see Ekiert et al., 2018 ). Note, however, that the third feature proposed by Casteleyn ( 2019 ), namely fostering a positive state of mind throughout the involvement of an audience beyond the classroom, has not been sufficiently validated either in the research on drama/theater or that on language education. Consequently, whether the involvement of an authentic audience is facilitative in promoting L2 speaking and presentation skills is yet to be investigated. Nielsen ( 2015 ) argued that classroom tasks should transcend the school walls and involve an authentic audience other than their classmates, because this would give students an opportunity to immediately and clearly see the meaning of their work (Purcell-Gates et al., 2002 ). However, in the field of FL education, in particular with regard to the courses that prepare students for public speaking skills, the construct of an audience is often conveniently used to refer to the instructor or students’ classmates; the adoption of an extramural live audience for real-life meaningful tasks is seldom seen.

Research Questions

This study intended to establish that authentic activities that are designed and regularly implemented in consideration of the aforementioned three features noted by Casteleyn ( 2019 ) will equip students with the kind of mindset and oral presentation skills that are key to the success of communicative FL oral activities outside the classroom. To establish the above contention, this study incorporated drama-based activities into the teaching of FL presentation skills, and explored whether such a course design would enhance college students’ FL presentation skills as well as their self-perceived competence. Two research questions were explored:

Do drama-based tasks implemented with classroom and real-life audiences differentially promote learners’ FL oral presentation performance?

Do drama-based tasks implemented with classroom and real-life audiences differentially enhance learners’ self-perceived FL oral presentation performance?

Participants

This research spanned two consecutive semesters. It involved two presentation classes from an Applied English department in a Taiwanese university. The two classes consisted of 20 and 22 students, respectively, with one of them experiencing the drama-based teaching method (the experimental group) and the other going through a traditional (no-drama) presentation training (the comparison group). Irrespective of differences in training methods, the two classes each met for 2 h per week, 18 weeks a semester with the aim of helping the students acquire verbal and nonverbal presentation skills so as to present their ideas to an audience clearly, logically and comfortably. The instructor-as-researcher developed class activities within the domain of an oral discourse training class based on her specialty so as to achieve the aforementioned class goal. By comparing two groups of students using two different teaching methods, the researcher hoped to investigate which method promoted better oral outcomes, and whether there was a difference in the intended learning gains—a practice also seen in other classroom-based research (e.g., Wacha & Liu, 2017 ).

An IRB approval was obtained prior to the study. The study strictly adhered to the ethical procedures approved and prescribed by the IRB. All participants had sufficient time to review the content and syllabi of the two classes under investigation. Importantly, they could decide if they would allow the researcher to analyze their data; while going over the syllabi in the first meeting, the instructor clearly informed them of the grading criteria, and explicitly told them that whether or not they decided to be a part of the study would not have any impact on their grades. All class activities—including the ones used in the experimental or comparison groups—are pedagogical possibilities that instructors could imagine seeing in an oral-based class. In this study, all students voluntarily agreed to participate and express their interest in knowing the result of this study.

Before the research, all participants had studied EFL for 8–12 years, and all were third-year college students admitted to the same department at the same university in Taiwan through standardized national examinations set at level B1 of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001 ). In their senior high school and college life, they had received training emphasizing English as the target FL. Importantly, they had similar weekly exposure to the target language, as gleaned from a screening survey administered prior to the onset of this study. Before they came to this class, they had not received formal training in oral presentation. Before the study began, all participants had to make a presentation. To avoid rating bias, two public speaking professionals who did not know the participants were invited to rate the participants’ performance on the presentation. Importantly, to enhance the validity of the two professionals’ ratings, the participants’ presentation recordings produced before and after the study were blindly presented to and scored by the two professionals without any time labels (such as pre- and/or post-study speech samples). The raters had no other interaction with the class and did not know the student participants personally. An independent t test ensured that no significant differences [ t (40) = − 0.65, p = 0.517] in the initial levels of oral presentation performance existed between the comparison and experimental groups. Additionally, the two groups’ self-perceptions of the six presentation techniques under investigation (i.e., structure, audience adaptation, speech content, posture, nonverbal delivery, visual aid handling) were not significantly different, showing skills homogeneity for the two groups of students at the beginning of the study.

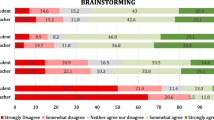

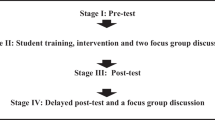

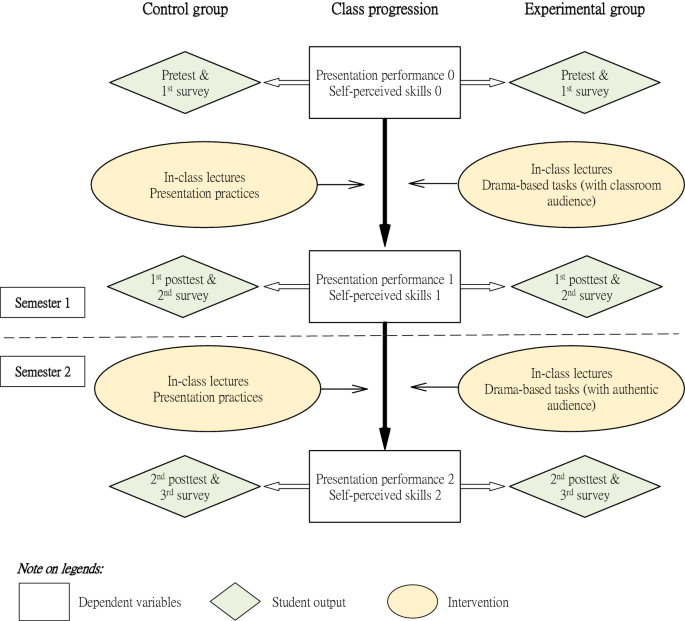

This research was a time-series classroom-based quasi-experimental study, recruiting students from two intact classes (see Rogers & Révész, 2020 ) and assigning them to the experimental condition (involving the drama-mediated treatment) and the comparison condition (involving the non-drama-mediated treatment consisting of ordinary public speaking training). Following the protocol of this type of research, the researcher collected the participants’ language samples assigned to these two conditions through multiple observations and made pairwise comparisons over a set period of time; as such it “allow[s] insight into the time course of language development, including changes that may be immediate, gradual, delayed, incubated, or residual…as well as the permanency of any effects resulting from a treatment” (p. 6). Addressing such a research method, Sato and Loewen ( 2019 ) noted that classroom-based quasi-experimental studies “[provide] learners with interventions that were seamlessly deployed in the genuine classroom contexts which permitted the examination of authentic classroom instruction with minimal disturbance” (p. 31). In this study, the comparison class received a standard regimen of presentation practice with lectures as supplemental sections; the experimental class received drama-based presentation practice, also with lectures as supplemental sections. The dependent variables under investigation were oral performance and six self-perceived presentation techniques (i.e., structure, audience adaptation, speech content, posture, nonverbal delivery, visual aid handling). Drama-based activities were the independent variable. The research design is summarized in Fig. 1 .

Flow chart of the research design

The Experimental Group

In the first semester, the experimental students practiced dramatic tasks that emphasized specific drama and oral presentation elements, while in the second semester they put their skills together for the production of a complete play for an outside-the-classroom audience. The experimental group treatment is described in more detail below.

At the beginning of the class, students in the experimental group were informed in advance that they needed to turn picture books in their mother tongue (Chinese) into cohesive scripted plays in English, and perform them for children from the neighborhood community. The students had to work in teams throughout the two-semester time span, each exploring and dramatizing a selected picture book under the scaffold and guidance of the instructor from each weekly meeting session. Created by Taiwanese writers and illustrators, all the picture books were written for children in Chinese. They were mostly fantasy, realistic fiction, and fables, ranging from 30 to 40 pages, with themes of friendship, sharing, family, love, or respecting differences—issues highly relevant to the life of the participants of this study. Chinese picture books were deliberately chosen so that the participating students worked on the English translation to create authentic lines from the original Chinese source materials rather than relying on readily available texts from English picture books. To this end, the experimental group received a series of drama-based tasks designed according to the principle of task dependency (Nunan, 2004 ), meaning one task building upon the preceding tasks. Specifically, the tasks for the experimental group were divided into two inter-related stages in the two semesters: (1) drama-based treatment, and (2) enactment of a theatrical play. During the first stage, the students were led to experience a series of drama-based tasks that were designed to incrementally foster their oratory skills and sensitivity to the six key elements of drama proposed by Aristotle ( 1984 ), namely, theme, plot, character, language/diction, music, and spectacle (see below for more details).

During the second stage of the treatment, while continuing building and polishing their team-scripted play, the students had to turn the play into a task of story theater, that is, a team production to be performed outside the classroom with community children as the authentic audience. While the time length and the story titles were pre-determined by the teacher, students were given extensive flexibility to extend the theme of the picture book and to work on the English translation of the lines from the original source materials in Chinese, the plot, dialogue production, character depiction, stage props, and the procedures of the play.

It is also worth noting that the first stage (drama-based treatment) primarily aims to attain “systematic desensitization” and “skill training”—the first two features for effective use of drama prescribed by Casteleyn ( 2019 ) through regularly conducted drama/theater training and performance within the classroom. Next, the second stage continued enhancing “systematic desensitization” and “skill training” by enacting a theatrical play. Importantly, the second stage attempted to foster a positive state of mind through the involvement of an audience beyond the classroom (cognitive modification)—the third feature prescribed by Casteleyn. The ensuing paragraphs will first detail how the drama-based treatment that took place in the first semester collectively and systematically equipped the students with the skill and competence that are key to the success of the second stage, namely enactment of a theatrical play.

First Stage: Drama-Based Treatment

During the first semester, the students were led to experience a variety of drama-based tasks, including storytelling, role play, character review, monologue, and play rehearsal in the classroom, which aimed to help the students think more deeply about the language and acting elements of their play production and characters. Details of these drama-based tasks, which aimed at fostering the aforementioned six drama elements proposed by Aristotle, are offered below:

Storytelling: each student chose or created a character in the story and told what happened in the story from his or her character’s point of view. This activity prompted the team to develop the plot of their final play production

Character review: each student made a self-introduction of his/her character’s part. In order to do so, the student must use imagination to consider onstage and offstage details about the character, such as age, physical attributes, personality characteristics, childhood, family history, education/work experience, habits, recreations, likes and dislikes, dreams, etc. This activity prompted the experimental group participants to make their characters come to life with a fuller form in the final play production