- Research Skills

50 Mini-Lessons For Teaching Students Research Skills

Please note, I am no longer blogging and this post hasn’t updated since April 2020.

For a number of years, Seth Godin has been talking about the need to “ connect the dots” rather than “collect the dots” . That is, rather than memorising information, students must be able to learn how to solve new problems, see patterns, and combine multiple perspectives.

Solid research skills underpin this. Having the fluency to find and use information successfully is an essential skill for life and work.

Today’s students have more information at their fingertips than ever before and this means the role of the teacher as a guide is more important than ever.

You might be wondering how you can fit teaching research skills into a busy curriculum? There aren’t enough hours in the day! The good news is, there are so many mini-lessons you can do to build students’ skills over time.

This post outlines 50 ideas for activities that could be done in just a few minutes (or stretched out to a longer lesson if you have the time!).

Learn More About The Research Process

I have a popular post called Teach Students How To Research Online In 5 Steps. It outlines a five-step approach to break down the research process into manageable chunks.

This post shares ideas for mini-lessons that could be carried out in the classroom throughout the year to help build students’ skills in the five areas of: clarify, search, delve, evaluate , and cite . It also includes ideas for learning about staying organised throughout the research process.

Notes about the 50 research activities:

- These ideas can be adapted for different age groups from middle primary/elementary to senior high school.

- Many of these ideas can be repeated throughout the year.

- Depending on the age of your students, you can decide whether the activity will be more teacher or student led. Some activities suggest coming up with a list of words, questions, or phrases. Teachers of younger students could generate these themselves.

- Depending on how much time you have, many of the activities can be either quickly modelled by the teacher, or extended to an hour-long lesson.

- Some of the activities could fit into more than one category.

- Looking for simple articles for younger students for some of the activities? Try DOGO News or Time for Kids . Newsela is also a great resource but you do need to sign up for free account.

- Why not try a few activities in a staff meeting? Everyone can always brush up on their own research skills!

- Choose a topic (e.g. koalas, basketball, Mount Everest) . Write as many questions as you can think of relating to that topic.

- Make a mindmap of a topic you’re currently learning about. This could be either on paper or using an online tool like Bubbl.us .

- Read a short book or article. Make a list of 5 words from the text that you don’t totally understand. Look up the meaning of the words in a dictionary (online or paper).

- Look at a printed or digital copy of a short article with the title removed. Come up with as many different titles as possible that would fit the article.

- Come up with a list of 5 different questions you could type into Google (e.g. Which country in Asia has the largest population?) Circle the keywords in each question.

- Write down 10 words to describe a person, place, or topic. Come up with synonyms for these words using a tool like Thesaurus.com .

- Write pairs of synonyms on post-it notes (this could be done by the teacher or students). Each student in the class has one post-it note and walks around the classroom to find the person with the synonym to their word.

- Explore how to search Google using your voice (i.e. click/tap on the microphone in the Google search box or on your phone/tablet keyboard) . List the pros and cons of using voice and text to search.

- Open two different search engines in your browser such as Google and Bing. Type in a query and compare the results. Do all search engines work exactly the same?

- Have students work in pairs to try out a different search engine (there are 11 listed here ). Report back to the class on the pros and cons.

- Think of something you’re curious about, (e.g. What endangered animals live in the Amazon Rainforest?). Open Google in two tabs. In one search, type in one or two keywords ( e.g. Amazon Rainforest) . In the other search type in multiple relevant keywords (e.g. endangered animals Amazon rainforest). Compare the results. Discuss the importance of being specific.

- Similar to above, try two different searches where one phrase is in quotation marks and the other is not. For example, Origin of “raining cats and dogs” and Origin of raining cats and dogs . Discuss the difference that using quotation marks makes (It tells Google to search for the precise keywords in order.)

- Try writing a question in Google with a few minor spelling mistakes. What happens? What happens if you add or leave out punctuation ?

- Try the AGoogleADay.com daily search challenges from Google. The questions help older students learn about choosing keywords, deconstructing questions, and altering keywords.

- Explore how Google uses autocomplete to suggest searches quickly. Try it out by typing in various queries (e.g. How to draw… or What is the tallest…). Discuss how these suggestions come about, how to use them, and whether they’re usually helpful.

- Watch this video from Code.org to learn more about how search works .

- Take a look at 20 Instant Google Searches your Students Need to Know by Eric Curts to learn about “ instant searches ”. Try one to try out. Perhaps each student could be assigned one to try and share with the class.

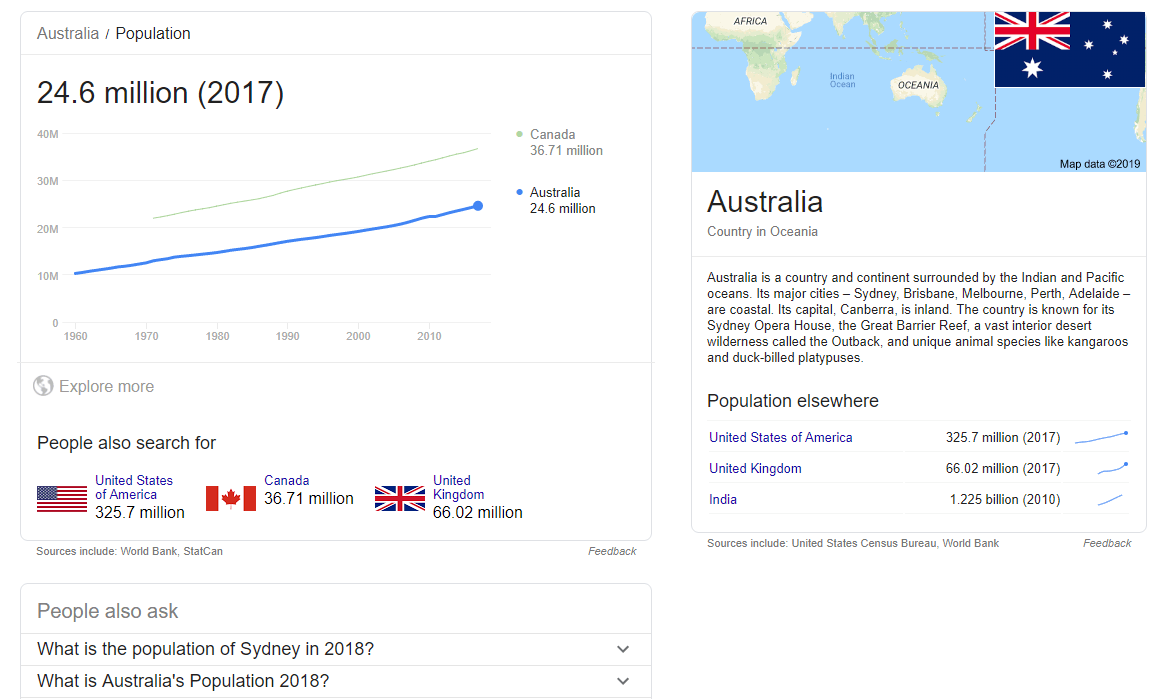

- Experiment with typing some questions into Google that have a clear answer (e.g. “What is a parallelogram?” or “What is the highest mountain in the world?” or “What is the population of Australia?”). Look at the different ways the answers are displayed instantly within the search results — dictionary definitions, image cards, graphs etc.

- Watch the video How Does Google Know Everything About Me? by Scientific American. Discuss the PageRank algorithm and how Google uses your data to customise search results.

- Brainstorm a list of popular domains (e.g. .com, .com.au, or your country’s domain) . Discuss if any domains might be more reliable than others and why (e.g. .gov or .edu) .

- Discuss (or research) ways to open Google search results in a new tab to save your original search results (i.e. right-click > open link in new tab or press control/command and click the link).

- Try out a few Google searches (perhaps start with things like “car service” “cat food” or “fresh flowers”). A re there advertisements within the results? Discuss where these appear and how to spot them.

- Look at ways to filter search results by using the tabs at the top of the page in Google (i.e. news, images, shopping, maps, videos etc.). Do the same filters appear for all Google searches? Try out a few different searches and see.

- Type a question into Google and look for the “People also ask” and “Searches related to…” sections. Discuss how these could be useful. When should you use them or ignore them so you don’t go off on an irrelevant tangent? Is the information in the drop-down section under “People also ask” always the best?

- Often, more current search results are more useful. Click on “tools” under the Google search box and then “any time” and your time frame of choice such as “Past month” or “Past year”.

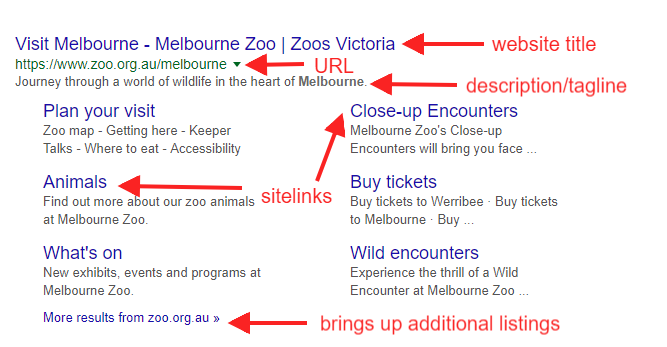

- Have students annotate their own “anatomy of a search result” example like the one I made below. Explore the different ways search results display; some have more details like sitelinks and some do not.

- Find two articles on a news topic from different publications. Or find a news article and an opinion piece on the same topic. Make a Venn diagram comparing the similarities and differences.

- Choose a graph, map, or chart from The New York Times’ What’s Going On In This Graph series . Have a whole class or small group discussion about the data.

- Look at images stripped of their captions on What’s Going On In This Picture? by The New York Times. Discuss the images in pairs or small groups. What can you tell?

- Explore a website together as a class or in pairs — perhaps a news website. Identify all the advertisements .

- Have a look at a fake website either as a whole class or in pairs/small groups. See if students can spot that these sites are not real. Discuss the fact that you can’t believe everything that’s online. Get started with these four examples of fake websites from Eric Curts.

- Give students a copy of my website evaluation flowchart to analyse and then discuss as a class. Read more about the flowchart in this post.

- As a class, look at a prompt from Mike Caulfield’s Four Moves . Either together or in small groups, have students fact check the prompts on the site. This resource explains more about the fact checking process. Note: some of these prompts are not suitable for younger students.

- Practice skim reading — give students one minute to read a short article. Ask them to discuss what stood out to them. Headings? Bold words? Quotes? Then give students ten minutes to read the same article and discuss deep reading.

All students can benefit from learning about plagiarism, copyright, how to write information in their own words, and how to acknowledge the source. However, the formality of this process will depend on your students’ age and your curriculum guidelines.

- Watch the video Citation for Beginners for an introduction to citation. Discuss the key points to remember.

- Look up the definition of plagiarism using a variety of sources (dictionary, video, Wikipedia etc.). Create a definition as a class.

- Find an interesting video on YouTube (perhaps a “life hack” video) and write a brief summary in your own words.

- Have students pair up and tell each other about their weekend. Then have the listener try to verbalise or write their friend’s recount in their own words. Discuss how accurate this was.

- Read the class a copy of a well known fairy tale. Have them write a short summary in their own words. Compare the versions that different students come up with.

- Try out MyBib — a handy free online tool without ads that helps you create citations quickly and easily.

- Give primary/elementary students a copy of Kathy Schrock’s Guide to Citation that matches their grade level (the guide covers grades 1 to 6). Choose one form of citation and create some examples as a class (e.g. a website or a book).

- Make a list of things that are okay and not okay to do when researching, e.g. copy text from a website, use any image from Google images, paraphrase in your own words and cite your source, add a short quote and cite the source.

- Have students read a short article and then come up with a summary that would be considered plagiarism and one that would not be considered plagiarism. These could be shared with the class and the students asked to decide which one shows an example of plagiarism .

- Older students could investigate the difference between paraphrasing and summarising . They could create a Venn diagram that compares the two.

- Write a list of statements on the board that might be true or false ( e.g. The 1956 Olympics were held in Melbourne, Australia. The rhinoceros is the largest land animal in the world. The current marathon world record is 2 hours, 7 minutes). Have students research these statements and decide whether they’re true or false by sharing their citations.

Staying Organised

- Make a list of different ways you can take notes while researching — Google Docs, Google Keep, pen and paper etc. Discuss the pros and cons of each method.

- Learn the keyboard shortcuts to help manage tabs (e.g. open new tab, reopen closed tab, go to next tab etc.). Perhaps students could all try out the shortcuts and share their favourite one with the class.

- Find a collection of resources on a topic and add them to a Wakelet .

- Listen to a short podcast or watch a brief video on a certain topic and sketchnote ideas. Sylvia Duckworth has some great tips about live sketchnoting

- Learn how to use split screen to have one window open with your research, and another open with your notes (e.g. a Google spreadsheet, Google Doc, Microsoft Word or OneNote etc.) .

All teachers know it’s important to teach students to research well. Investing time in this process will also pay off throughout the year and the years to come. Students will be able to focus on analysing and synthesizing information, rather than the mechanics of the research process.

By trying out as many of these mini-lessons as possible throughout the year, you’ll be really helping your students to thrive in all areas of school, work, and life.

Also remember to model your own searches explicitly during class time. Talk out loud as you look things up and ask students for input. Learning together is the way to go!

You Might Also Enjoy Reading:

How To Evaluate Websites: A Guide For Teachers And Students

Five Tips for Teaching Students How to Research and Filter Information

Typing Tips: The How and Why of Teaching Students Keyboarding Skills

8 Ways Teachers And Schools Can Communicate With Parents

10 Replies to “50 Mini-Lessons For Teaching Students Research Skills”

Loving these ideas, thank you

This list is amazing. Thank you so much!

So glad it’s helpful, Alex! 🙂

Hi I am a student who really needed some help on how to reasearch thanks for the help.

So glad it helped! 🙂

seriously seriously grateful for your post. 🙂

So glad it’s helpful! Makes my day 🙂

How do you get the 50 mini lessons. I got the free one but am interested in the full version.

Hi Tracey, The link to the PDF with the 50 mini lessons is in the post. Here it is . Check out this post if you need more advice on teaching students how to research online. Hope that helps! Kathleen

Best wishes to you as you face your health battler. Hoping you’ve come out stronger and healthier from it. Your website is so helpful.

Comments are closed.

Join my VIP teacher email club!

Finally, a guide for upper elementary teachers that will show you how to teach research reports in a step-by-step format!

If you are struggling with teaching the research report process, you are not alone. Seriously, we’ve all been there!

I spent several years avoiding research reports for my 5th grade writers or simply depending on the Library-Media Specialist to teach the research process.

One year, I decided to take the plunge and teach my students how to research a topic and write a research report.

The process was clunky at first, but I learned a lot about how students approach research and how to guide them from choosing a topic to completing their final copies.

Before we discuss the HOW , let’s talk about the WHY .

Why You Should Be Assigning Research Reports to Your 5th and 6th Grade Students

I have three main reasons for assigning research reports to my students.

First, the skill involved in finding reliable sources and citing sources is valuable.

Beginning in 5th grade, and possibly even before, students need to be able to discern the reliability of a source . They should be able to spot propaganda and distinguish between reputable sources and phony ones.

Teaching the procedure for citing sources is important because my 5th grade students need to grasp the reality of plagiarism and how to avoid it.

By providing information about the sources they used, students are consciously avoiding copying the work of authors and learning to give credit where credit is due.

Second, by taking notes and organizing their notes into an outline, students are exercising their ability to find main ideas and corresponding details.

Being able to organize ideas is crucial for young writers.

Third, when writing research reports, students are internalizing the writing process, including organizing, writing a rough draft, proofreading/editing, and writing a final draft.

When students write research reports about topics of interest, they are fine-tuning their reading and writing skills.

How to Teach Step-By-Step Research Reports in Grades 5 & 6

As a veteran upper elementary teacher, I know exactly what is going to happen when I tell my students that we are going to start research reports.

There will be a resounding groan followed by students voicing their displeasure. (It goes something like this…. “Mrs. Bazzit! That’s too haaaaaaard!” or “Ugh. That’s boring!” *Sigh* I’ve heard it all, lol.)

This is when I put on my (somewhat fictional) excited teacher hat and help them to realize that the research report process will be fun and interesting.

Step 1: Help Students to Choose a Topic and Cite Sources for Research Reports

Students definitely get excited when they find out they are allowed to choose their own research topic. Providing choice leads to higher engagement and interest.

It’s best practice to provide a list of possible research topics to students, but also allow them to choose a different topic.

Be sure to make your research topics narrow to help students focus on sources. If students choose broad topics, the sources they find will overwhelm them with information.

Too Broad: American Revolution

Just Right: The Battle of Yorktown

Too Broad: Ocean Life

Just Right: Great White Shark

Too Broad: Important Women in History

Just Right: The Life of Abigail Adams

Be sure to discuss appropriate, reliable sources with students.

I suggest projecting several examples of internet sources on your technology board. Ask students to decide if the sources look reliable or unreliable.

While teaching students about citing sources, it’s a great time to discuss plagiarism and ways to avoid it.

Students should never copy the words of an author unless they are properly quoting the text.

In fact, I usually discourage students from quoting their sources in their research reports. In my experience, students will try to quote a great deal of text and will border on plagiarism.

I prefer to see students paraphrase from their sources because this skill helps them to refine their summarization skills.

Citing sources is not as hard as it sounds! I find that my students generally use books and internet sources, so those are the two types of citations that I focus on.

How to cite a book:

Author’s last name, First name. Title of Book. City of Publication: Publisher, Date.

How to cite an internet article:

Author’s last name, First name (if available). “Title of Article or Page.” Full http address, Date of access.

If you continue reading to the bottom of this post, I have created one free screencast for each of the five steps of the research process!

Step 2: Research Reports: Take Notes

During this step, students will use their sources to take notes.

I do provide instruction and examples during this step because from experience, I know that students will think every piece of information from each source is important and they will copy long passages from each source.

I teach students that taking notes is an exercise in main idea and details. They should read the source, write down the main idea, and list several details to support the main idea.

I encourage my students NOT to copy information from the source but instead to put the information in their own words. They will be less likely to plagiarize if their notes already contain their own words.

Additionally, during this step, I ask students to write a one-sentence thesis statement. I teach students that a thesis statement tells the main point of their research reports.

Their entire research report will support the thesis statement, so the thesis statement is actually a great way to help students maintain a laser focus on their research topic.

Step 3: Make a Research Report Outline

Making an outline can be intimidating for students, especially if they’ve never used this organization format.

However, this valuable step will teach students to organize their notes into the order that will be used to write the rough draft of their reports.

Because making an outline is usually a new concept for my 5th graders, we do 2-3 examples together before I allow students to make their outlines for their research reports.

I recommend copying an outline template for students to have at their fingertips while creating their first outline.

Be sure to look over students’ outlines for organization, order, and accuracy before allowing them to move on to the next step (writing rough drafts).

Step 4: Write a Research Report Draft

During this step, each student will write a rough draft of his/her research report.

If they completed their outlines correctly, this step will be fairly simple.

Students will write their research reports in paragraph form.

One problem that is common among my students is that instead of writing in paragraphs, they write their sentences in list format.

I find that it’s helpful to write a paragraph in front of and with students to remind them that when writing a paragraph, the next sentence begins immediately after the prior sentence.

Once students’ rough drafts are completed, it’s time to proofread/edit!

To begin, I ask my students to read their drafts aloud to listen for their own mistakes.

Next, I ask my students to have two individuals look over their draft and suggest changes.

Step 5: Research Reports – Students Will Write Their Final Drafts!

It’s finally time to write final drafts!

After students have completed their rough drafts and made edits, I ask them to write final drafts.

Students’ final drafts should be as close to perfect as possible.

I prefer a typed final draft because students will have access to a spellchecker and other features that will make it easier to create their final draft.

Think of a creative way to display the finished product, because they will be SO proud of their research reports after all the hard work that went into creating them!

When grading the reports, use a rubric similar to the one shown in the image at the beginning of this section.

A detailed rubric will help students to clearly see their successes and areas of needed improvement.

Once students have completed their first research projects, I find that they have a much easier time with the other research topics assigned throughout the remainder of the school year.

If you are interested in a no-prep, step-by-step research report instructional unit, please click here to visit my Research Report Instructional Unit for 5th Grade and 6th Grade.

This instructional unit will guide students step-by-step through the research process, including locating reliable sources, taking notes, creating an outline, writing a report, and making a “works cited” page.

I’d like to share a very special free resource with you. I created five screencast videos, one for each step of the research report process. These screencasts pair perfectly with my Research Report Instructional Unit for 5th Grade and 6th Grade!

Research Report Step 1 Screencast

Research Report Step 2 Screencast

Research Report Step 3 Screencast

Research Report Step 4 Screencast

Research Report Step 5 Screencast

To keep this post for later, simply save this image to your teacher Pinterest board!

Hi, If i purchase your complete package on grade 5/6 writing does it come with your wonderful recordings on how to teach them? Thanks

Hi Gail! The recordings on this blog post can be used by anyone and I will leave them up 🙂 The writing bundle doesn’t come with any recordings but I did include step-by-step instructions for teachers. I hope this helps!

Thank you for sharing your information with everyone. I know how to write (I think, haha), but I wanted to really set my students up for success with their research and writing. Your directions and guides are just what I needed to jar my memory and help my students become original writers. Be blessed.

You are very welcome, Andrea! Thank you for this comment 🙂

Hi Andrea, I am a veteran teacher who has taught nothing but primary for 25 years. However, this is my first year in 5th. I’m so excited to have found your post. Can you direct me to how I can purchase your entire bundle for writing a 5-paragraph essay. Thanks, Sue

Sure, Susan, I can help with that! Here is the link for the 5th Grade Writing Bundle: https://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Product/5th-Grade-Writing-Bundle-3611643

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

You may also enjoy...

How to Teach the Civil War in Upper Elementary

Tips for Working with a Difficult Teaching Partner

Help! My Students Hate Social Studies Class!

How to Teach the Lost Colony of Roanoke

How to Teach Writing Using Paired Passages

How to Use Google Resources in Upper Elementary – A Growing Post

What can i help you teach, find it here, let's connect, i'd love to connect with you.

Enter your first name and email address to join my exclusive VIP email club.

Copyright © 2020 | Thrive in Grade Five | All Rights Reserved

Quick Links

Teaching Research Skills to K-12 Students in The Classroom

Research is at the core of knowledge. Nobody is born with an innate understanding of quantum physics. But through research , the knowledge can be obtained over time. That’s why teaching research skills to your students is crucial, especially during their early years.

But teaching research skills to students isn’t an easy task. Like a sport, it must be practiced in order to acquire the technique. Using these strategies, you can help your students develop safe and practical research skills to master the craft.

What Is Research?

By definition, it’s a systematic process that involves searching, collecting, and evaluating information to answer a question. Though the term is often associated with a formal method, research is also used informally in everyday life!

Whether you’re using it to write a thesis paper or to make a decision, all research follows a similar pattern.

- Choose a topic : Think about general topics of interest. Do some preliminary research to make sure there’s enough information available for you to work with and to explore subtopics within your subject.

- Develop a research question : Give your research a purpose; what are you hoping to solve or find?

- Collect data : Find sources related to your topic that will help answer your research questions.

- Evaluate your data : Dissect the sources you found. Determine if they’re credible and which are most relevant.

- Make your conclusion : Use your research to answer your question!

Why Do We Need It?

Research helps us solve problems. Trying to answer a theoretical question? Research. Looking to buy a new car? Research. Curious about trending fashion items? Research!

Sometimes it’s a conscious decision, like when writing an academic paper for school. Other times, we use research without even realizing it. If you’re trying to find a new place to eat in the area, your quick Google search of “food places near me” is research!

Whether you realize it or not, we use research multiple times a day, making it one of the most valuable lifelong skills to have. And it’s why — as educators —we should be teaching children research skills in their most primal years.

Teaching Research Skills to Elementary Students

In elementary school, children are just beginning their academic journeys. They are learning the essentials: reading, writing, and comprehension. But even before they have fully grasped these concepts, you can start framing their minds to practice research.

According to curriculum writer and former elementary school teacher, Amy Lemons , attention to detail is an essential component of research. Doing puzzles, matching games, and other memory exercises can help equip students with this quality before they can read or write.

Improving their attention to detail helps prepare them for the meticulous nature of research. Then, as their reading abilities develop, teachers can implement reading comprehension activities in their lesson plans to introduce other elements of research.

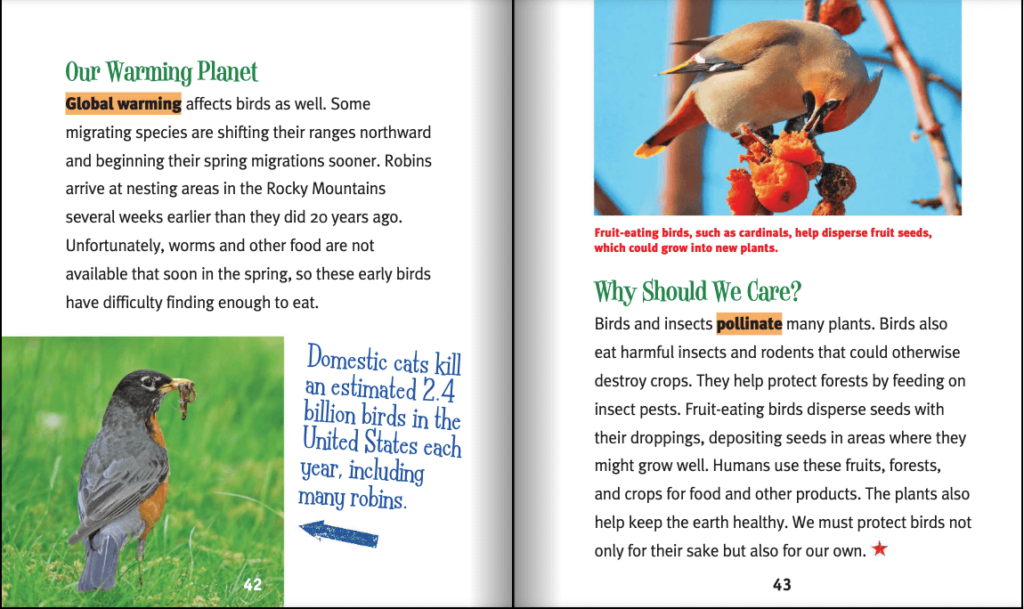

One of the best strategies for teaching research skills to elementary students is practicing reading comprehension . It forces them to interact with the text; if they come across a question they can’t answer, they’ll need to go back into the text to find the information they need.

Some activities could include completing compare/contrast charts, identifying facts or questioning the text, doing background research, and setting reading goals. Here are some ways you can use each activity:

- How it translates : Step 3, collect data; Step 4, evaluate your data

- Questioning the text : If students are unsure which are facts/not facts, encourage them to go back into the text to find their answers.

- How it translates : Step 3, collect data; Step 4, evaluate your data; Step 5, make your conclusion

- How it translates : Step 1, choose your topic

- How it translates : Step 2, develop a research question; Step 5, make your conclusion

Resources for Elementary Research

If you have access to laptops or tablets in the classroom, there are some free tools available through Pennsylvania’s POWER Kids to help with reading comprehension. Scholastic’s BookFlix and TrueFlix are 2 helpful resources that prompt readers with questions before, after, and while they read.

- BookFlix : A resource for students who are still new to reading. Students will follow along as a book is read aloud. As they listen or read, they will be prodded to answer questions and play interactive games to test and strengthen their understanding.

- TrueFlix : A resource for students who are proficient in reading. In TrueFlix, students explore nonfiction topics. It’s less interactive than BookFlix because it doesn’t prompt the reader with games or questions as they read. (There are still options to watch a video or listen to the text if needed!)

Teaching Research Skills to Middle School Students

By middle school, the concept of research should be familiar to students. The focus during this stage should be on credibility . As students begin to conduct research on their own, it’s important that they know how to determine if a source is trustworthy.

Before the internet, encyclopedias were the main tool that people used for research. Now, the internet is our first (and sometimes only) way of looking information up.

Unlike encyclopedias which can be trusted, students must be wary of pulling information offline. The internet is flooded with unreliable and deceptive information. If they aren’t careful, they could end up using a source that has inaccurate information!

How To Know If A Source Is Credible

In general, credible sources are going to come from online encyclopedias, academic journals, industry journals, and/or an academic database. If you come across an article that isn’t from one of those options, there are details that you can look for to determine if it can be trusted.

- The author: Is the author an expert in their field? Do they write for a respected publication? If the answer is no, it may be good to explore other sources.

- Citations: Does the article list its sources? Are the sources from other credible sites like encyclopedias, databases, or journals? No list of sources (or credible links) within the text is usually a red flag.

- Date: When was the article published? Is the information fresh or out-of-date? It depends on your topic, but a good rule of thumb is to look for sources that were published no later than 7-10 years ago. (The earlier the better!)

- Bias: Is the author objective? If a source is biased, it loses credibility.

An easy way to remember what to look for is to utilize the CRAAP test . It stands for C urrency (date), R elevance (bias), A uthority (author), A ccuracy (citations), and P urpose (bias). They’re noted differently, but each word in this acronym is one of the details noted above.

If your students can remember the CRAAP test, they will be able to determine if they’ve found a good source.

Resources for Middle School Research

To help middle school researchers find reliable sources, the database Gale is a good starting point. It has many components, each accessible on POWER Library’s site. Gale Litfinder , Gale E-books , or Gale Middle School are just a few of the many resources within Gale for middle school students.

Teaching Research Skills To High Schoolers

The goal is that research becomes intuitive as students enter high school. With so much exposure and practice over the years, the hope is that they will feel comfortable using it in a formal, academic setting.

In that case, the emphasis should be on expanding methodology and citing correctly; other facets of a thesis paper that students will have to use in college. Common examples are annotated bibliographies, literature reviews, and works cited/reference pages.

- Annotated bibliography : This is a sheet that lists the sources that were used to conduct research. To qualify as annotated , each source must be accompanied by a short summary or evaluation.

- Literature review : A literature review takes the sources from the annotated bibliography and synthesizes the information in writing.

- Works cited/reference pages : The page at the end of a research paper that lists the sources that were directly cited or referenced within the paper.

Resources for High School Research

Many of the Gale resources listed for middle school research can also be used for high school research. The main difference is that there is a resource specific to older students: Gale High School .

If you’re looking for some more resources to aid in the research process, POWER Library’s e-resources page allows you to browse by grade level and subject. Take a look at our previous blog post to see which additional databases we recommend.

Visit POWER Library’s list of e-resources to start your research!

Empowering students to develop research skills

February 8, 2021

This post is republished from Into Practice , a biweekly communication of Harvard’s Office of the Vice Provost for Advances in Learning

Terence D. Capellini, Richard B Wolf Associate Professor of Human Evolutionary Biology, empowers students to grow as researchers in his Building the Human Body course through a comprehensive, course-long collaborative project that works to understand the changes in the genome that make the human skeleton unique. For instance, of the many types of projects, some focus on the genetic basis of why human beings walk on two legs. This integrative “Evo-Devo” project demands high levels of understanding of biology and genetics that students gain in the first half of class, which is then applied hands-on in the second half of class. Students work in teams of 2-3 to collect their own morphology data by measuring skeletons at the Harvard Museum of Natural History and leverage statistics to understand patterns in their data. They then collect and analyze DNA sequences from humans and other animals to identify the DNA changes that may encode morphology. Throughout this course, students go from sometimes having “limited experience in genetics and/or morphology” to conducting their own independent research. This project culminates in a team presentation and a final research paper.

The benefits: Students develop the methodological skills required to collect and analyze morphological data. Using the UCSC Genome browser and other tools, students sharpen their analytical skills to visualize genomics data and pinpoint meaningful genetic changes. Conducting this work in teams means students develop collaborative skills that model academic biology labs outside class, and some student projects have contributed to published papers in the field. “Every year, I have one student, if not two, join my lab to work on projects developed from class to try to get them published.”

“The beauty of this class is that the students are asking a question that’s never been asked before and they’re actually collecting data to get at an answer.”

The challenges: Capellini observes that the most common challenge faced by students in the course is when “they have a really terrific question they want to explore, but the necessary background information is simply lacking. It is simply amazing how little we do know about human development, despite its hundreds of years of study.” Sometimes, for instance, students want to learn about the evolution, development, and genetics of a certain body part, but it is still somewhat a mystery to the field. In these cases, the teaching team (including co-instructor Dr. Neil Roach) tries to find datasets that are maximally relevant to the questions the students want to explore. Capellini also notes that the work in his class is demanding and hard, just by the nature of the work, but students “always step up and perform” and the teaching team does their best to “make it fun” and ensure they nurture students’ curiosities and questions.

Takeaways and best practices

- Incorporate previous students’ work into the course. Capellini intentionally discusses findings from previous student groups in lectures. “They’re developing real findings and we share that when we explain the project for the next groups.” Capellini also invites students to share their own progress and findings as part of class discussion, which helps them participate as independent researchers and receive feedback from their peers.

- Assign groups intentionally. Maintaining flexibility allows the teaching team to be more responsive to students’ various needs and interests. Capellini will often place graduate students by themselves to enhance their workload and give them training directly relevant to their future thesis work. Undergraduates are able to self-select into groups or can be assigned based on shared interests. “If two people are enthusiastic about examining the knee, for instance, we’ll match them together.”

- Consider using multiple types of assessments. Capellini notes that exams and quizzes are administered in the first half of the course and scaffolded so that students can practice the skills they need to successfully apply course material in the final project. “Lots of the initial examples are hypothetical,” he explains, even grounded in fiction and pop culture references, “but [students] have to eventually apply the skills they learned in addressing the hypothetical example to their own real example and the data they generate” for the Evo-Devo project. This is coupled with a paper and a presentation treated like a conference talk.

Bottom line: Capellini’s top advice for professors looking to help their own students grow as researchers is to ensure research projects are designed with intentionality and fully integrated into the syllabus. “You can’t simply tack it on at the end,” he underscores. “If you want this research project to be a substantive learning opportunity, it has to happen from Day 1.” That includes carving out time in class for students to work on it and make the connections they need to conduct research. “Listen to your students and learn about them personally” so you can tap into what they’re excited about. Have some fun in the course, and they’ll be motivated to do the work.

ChatGPT for Teachers

Trauma-informed practices in schools, teacher well-being, cultivating diversity, equity, & inclusion, integrating technology in the classroom, social-emotional development, covid-19 resources, invest in resilience: summer toolkit, civics & resilience, all toolkits, degree programs, trauma-informed professional development, teacher licensure & certification, how to become - career information, classroom management, instructional design, lifestyle & self-care, online higher ed teaching, current events, web research skills: teaching your students the fundamentals.

It is ironic that in the era of the Internet anyone should have any issues concerning basic research skills. The Internet, after all, is the richest, most versatile, and most complete information repository in the history of mankind. While the Internet has greatly increased choices for and the quality of research tools, it has also brought with it some challenges and impediments.

Simply put, the Internet is overwhelming people with information. Even so-called “information experts” and research skills teacher are struggling to keep up with all the changes and the multi-faceted new choices. Information overload, therefore, is one of the most powerful reasons why some students are struggling with their research conducting abilities.

What about the student basics or fundamentals?

The biggest reason why some students are not doing well in the area of research abilities is probably because many of them have not acquired the fundamental or student basics necessary for doing any kind of research—whether on or off the Internet. Some of these important, but often overlooked, student basics (skills) include:

- Good listening skills: Students today have to be as good at processing oral/spoken input as written communication. What is happening, however, is that more and more students are depending on/using spoken/oral communication (e.g., YouTube) and when they do turn to written communication, it usually involves newscasts and social media. The listening skills required for these tools are, simply put, different than those needed for serious academic communication.

- Lack of focus: In this microwaving, fast-food society many people want things to happen too fast. Their attention is being pulled in too many directions. This is a problem when complicated subjects are being studied.

- Lack of familiarity with databases: Some people don’t even realize that their local libraries have a place meant specifically for serious research (as opposed for the lighthearted research you can conduct with a search engine.

- Poor writing skills: Many times it’s not the research that’s lacking but the ability to translate what students discover into coherent, well-organized extrapolations.

How are students currently doing with basic research?

The most recent Project Information Literacy Progress Report posits that about 84 percent of students have difficulty getting course-related research off the ground; they also express having difficulty figuring out the difference between scholarly sources and non-scholarly sources. As for the latter, the problem is that scholarly research can be found through search engines (such as Google) but, also, much of the material on these popular search engines is not suitable for scholarly work.

How can you help students develop better research skills?

Don’t assume students know how to use the Internet for scholarly research. Here are some tips to get started.

- Take students by the hand and teach them about each specific research tool one at a time.

- Give students written instructions on preferred research tools.

- Encourage students to use databases as much as possible.

- Make sure your school/program has classes on research skills development.

- Work with other professionals in order to set up proactive research skills-building tools.

- Before classes get going, test each student to see where he/she stands individually on research skills.

- Stay abreast of the latest information/technology on the subject.

- Work to enhance/increase the number of research skills development programs.

- Encourage students to use resources beyond the Internet.

There are not enough of what we call a “research skills teacher.” Actually, every instructor needs to become a research skills teacher. Students can develop the skills they need but only if they are taught them at every stage of their education.

You may also like to read

- How to Help Middle School Students Develop Research Skills

- Five Free Websites for Students to Build Research Skills

- Beyond the Test: How Teaching Soft Skills Helps Students Succeed

- Essential Skills for the 21st Century: Teaching Students to Curate Content

- 5 Methods to Teach Students How to do Research Papers

- Building Math Skills in High School Students

Categorized as: Tips for Teachers and Classroom Resources

Tagged as: Engaging Activities

- Master's in Education Technology & Learning D...

- Online & Campus Master's in Secondary Educati...

- Master's in Trauma-Informed Education and Car...

What are research skills?

Last updated

26 April 2023

Reviewed by

Broadly, it includes a range of talents required to:

Find useful information

Perform critical analysis

Form hypotheses

Solve problems

It also includes processes such as time management, communication, and reporting skills to achieve those ends.

Research requires a blend of conceptual and detail-oriented modes of thinking. It tests one's ability to transition between subjective motivations and objective assessments to ensure only correct data fits into a meaningfully useful framework.

As countless fields increasingly rely on data management and analysis, polishing your research skills is an important, near-universal way to improve your potential of getting hired and advancing in your career.

Make research less tedious

Dovetail streamlines research to help you uncover and share actionable insights

What are basic research skills?

Almost any research involves some proportion of the following fundamental skills:

Organization

Decision-making

Investigation and analysis

Creative thinking

What are primary research skills?

The following are some of the most universally important research skills that will help you in a wide range of positions:

Time management — From planning and organization to task prioritization and deadline management, time-management skills are highly in-demand workplace skills.

Problem-solving — Identifying issues, their causes, and key solutions are another essential suite of research skills.

Critical thinking — The ability to make connections between data points with clear reasoning is essential to navigate data and extract what's useful towards the original objective.

Communication — In any collaborative environment, team-building and active listening will help researchers convey findings more effectively through data summarizations and report writing.

What are the most important skills in research?

Detail-oriented procedures are essential to research, which allow researchers and their audience to probe deeper into a subject and make connections they otherwise may have missed with generic overviews.

Maintaining priorities is also essential so that details fit within an overarching strategy. Lastly, decision-making is crucial because that's the only way research is translated into meaningful action.

- Why are research skills important?

Good research skills are crucial to learning more about a subject, then using that knowledge to improve an organization's capabilities. Synthesizing that research and conveying it clearly is also important, as employees seek to share useful insights and inspire effective actions.

Effective research skills are essential for those seeking to:

Analyze their target market

Investigate industry trends

Identify customer needs

Detect obstacles

Find solutions to those obstacles

Develop new products or services

Develop new, adaptive ways to meet demands

Discover more efficient ways of acquiring or using resources

Why do we need research skills?

Businesses and individuals alike need research skills to clarify their role in the marketplace, which of course, requires clarity on the market in which they function in. High-quality research helps people stay better prepared for challenges by identifying key factors involved in their day-to-day operations, along with those that might play a significant role in future goals.

- Benefits of having research skills

Research skills increase the effectiveness of any role that's dependent on information. Both individually and organization-wide, good research simplifies what can otherwise be unwieldy amounts of data. It can help maintain order by organizing information and improving efficiency, both of which set the stage for improved revenue growth.

Those with highly effective research skills can help reveal both:

Opportunities for improvement

Brand-new or previously unseen opportunities

Research skills can then help identify how to best take advantage of available opportunities. With today's increasingly data-driven economy, it will also increase your potential of getting hired and help position organizations as thought leaders in their marketplace.

- Research skills examples

Being necessarily broad, research skills encompass many sub-categories of skillsets required to extrapolate meaning and direction from dense informational resources. Identifying, interpreting, and applying research are several such subcategories—but to be specific, workplaces of almost any type have some need of:

Searching for information

Attention to detail

Taking notes

Problem-solving

Communicating results

Time management

- How to improve your research skills

Whether your research goals are to learn more about a subject or enhance workflows, you can improve research skills with this failsafe, four-step strategy:

Make an outline, and set your intention(s)

Know your sources

Learn to use advanced search techniques

Practice, practice, practice (and don't be afraid to adjust your approach)

These steps could manifest themselves in many ways, but what's most important is that it results in measurable progress toward the original goals that compelled you to research a subject.

- Using research skills at work

Different research skills will be emphasized over others, depending on the nature of your trade. To use research most effectively, concentrate on improving research skills most relevant to your position—or, if working solo, the skills most likely have the strongest impact on your goals.

You might divide the necessary research skills into categories for short, medium, and long-term goals or according to each activity your position requires. That way, when a challenge arises in your workflow, it's clearer which specific research skill requires dedicated attention.

How can I learn research skills?

Learning research skills can be done with a simple three-point framework:

Clarify the objective — Before delving into potentially overwhelming amounts of data, take a moment to define the purpose of your research. If at any point you lose sight of the original objective, take another moment to ask how you could adjust your approach to better fit the original objective.

Scrutinize sources — Cross-reference data with other sources, paying close attention to each author's credentials and motivations.

Organize research — Establish and continually refine a data-organization system that works for you. This could be an index of resources or compiling data under different categories designed for easy access.

Which careers require research skills?

Especially in today's world, most careers require some, if not extensive, research. Developers, marketers, and others dealing in primarily digital properties especially require extensive research skills—but it's just as important in building and manufacturing industries, where research is crucial to construct products correctly and safely.

Engineering, legal, medical, and literally any other specialized field will require excellent research skills. Truly, almost any career path will involve some level of research skills; and even those requiring only minimal research skills will at least require research to find and compare open positions in the first place.

Get started today

Go from raw data to valuable insights with a flexible research platform

Editor’s picks

Last updated: 21 December 2023

Last updated: 16 December 2023

Last updated: 6 October 2023

Last updated: 25 November 2023

Last updated: 12 May 2023

Last updated: 15 February 2024

Last updated: 11 March 2024

Last updated: 12 December 2023

Last updated: 18 May 2023

Last updated: 6 March 2024

Last updated: 10 April 2023

Last updated: 20 December 2023

Latest articles

Related topics, log in or sign up.

Get started for free

- Skip to primary navigation

- Skip to main content

- Skip to primary sidebar

- Skip to footer

Teaching ELA with Joy

Middle School ELA Resources

6 Ideas for Teaching Research Skills

By Joy Sexton Leave a Comment

When thinking about ideas for teaching research skills, teachers can easily become overwhelmed. That’s mainly because our standards list so many requirements for students to master! If your school requires a major research paper, you might need to start off with some smaller practice pieces. Do your students know how to paraphrase? Can they judge if a website is credible? Do they know how to compose an open-ended question? How about citing sources? Check out these activities that will help your students gain essential practice with research skills.

Ideas for Teaching Research Skills

1. Say It Your Way – One great place to start is getting students in the habit of paraphrasing. Choose an interesting topic and a short article to demonstrate. An online encyclopedia comes in handy here. We worked with information on a particular dinosaur. Project the article and with class participation, highlight 5 pieces of key information. This is the information students will be “taking notes” on. Then query the students how each piece of information could be stated in bulleted notes (without copying full sentences!). Model the bulleted note-taking as students complete their own copy. When the bulleted notes are complete, engage the class in composing new sentences that are paraphrased. Again, model writing this paragraph as students follow suit. Now the process of note-taking and paraphrasing should seem “doable” in their own research.

2. Surprising Facts – A fun way for students to dive into research is to give them a topic and simply task them with finding facts that are surprising . This activity works great with partners. Topics could tie in with a current class novel or story (such as “elephant” from The Giver) or even an author. Surprising facts about Gary Paulsen, Kwame Alexander, or Edgar Alan Poe make an interesting class discussion! Students enjoy sharing their findings. I devised a free handout where students can record the topic, their surprising facts, and the website(s) they used. Grab it in Google Docs and copy to your drive by clicking the link: https://bit.ly/3Nah9UB

3. Give Credit Where It’s Due – Most students understand that sources need to be cited. However, many remain unclear on the process. A demonstration using a citation generator will help. I like www.bibme.org , but if you google “citation generator” you’ll find a slew of them. I open a few tabs in advance with animal websites. To demonstrate, grab the URLs and insert into the generator. Cut and paste the citations to a blank document. Then you can show students how to indent and alphabetize. For practice, give students a list of several websites. You could also include a magazine article and a book. With a partner, have them construct the works cited using a generator, indenting and alphabetizing correctly.

4. Support an Opinion – Students love to voice their opinions , but need practice supporting them with facts . Lucky for us, there are loads of argument topics available free online. You can offer several topic choices, and students choose one and respond with their opinion. Next, have them locate 2-3 important facts or statistics that specifically support their opinion. Make sure to emphasize that the information will need to be paraphrased. And since sources were used, a Works Cited should also be added.

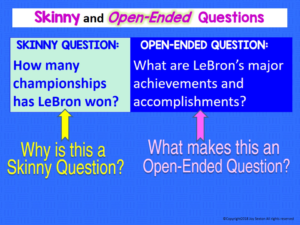

5. Good Question! – One purpose of research is to answer a question, so students need practice in formulating good questions . An open-ended question, one that requires more than just one answer, is the goal. Start by demonstrating the difference between an open-ended question and a “thin” or “skinny” question (not open-ended). One way is to project an image of a violin on your whiteboard. Then type or write out these questions: 1. How many strings does a violin have? 2. How is a violin made? Ask students which is the open-ended question and why. Then project another image. Ask for volunteers to formulate a thin question, and then an open-ended question. Once they understand this concept, let all students practice composing both thin and open-ended questions. This activity works well in groups. Each student contributes a topic.

6. Format is Key – A sure-fire way to get students excited about a research project is offering engaging formats for presentation. PowerPoint is well known by most students, but take time to demonstrate some other great options. Canva allows students to create awesome Infographics! Or how about a tri-fold brochure in Publisher? Students can make up a quick template with custom headings. Set a timer for 10-15 minutes and let students experiment with the possibilities. My students have enjoyed a Q & A format, using a template I created with PowerPoint. Even students who prefer typing their report in paragraphs can easily design a poster. Along with the paragraphs, just add images, captions, topic, and headings.

I hope I have broadened your ideas for teaching research skills. I think you’ll agree that students need time and mini-lessons to get comfortable with the procedures we require. A quick graphic organizer coupled with a short activity can help solidify the skills they’ll need.

Here’s another post I wrote that will give you more helpful ideas for teaching research skills: 10 Ideas to Make Teaching Research Easier

Join the Newsletter

Reader Interactions

Leave a reply cancel reply.

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Notify me of follow-up comments by email.

Notify me of new posts by email.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

Top Nav Breadcrumb

- Ask a question

Approaches to learning: supporting research skills among learners through the language of instruction

This article talks about the insights gathered (through a Visible Thinking Routine) from Grade 2 – 5 English learners when they expressed the ir struggles conducting research in their homeroom .

T hese reflec tions unearthed how language can be a barrier and how teachers can collaboratively play a role in bridging these gaps for learner s , for them to overcome these challenges with simple research strategies .

By Lamiya Bharmal

“ I was curious to know if teachers’ thinking is visible to students and if students’ thinking is visible to teachers and this was the catalyst for my research. “

The PYP Approaches to l earning, focuses on skills that students can develop to help them “learn how to learn”. One of the skills is Research skills and this connects with the subject I teach – Information Literacy.

Passionate about teaching and learning, I enrolled for a Making Thinking Visible course. I gained some fresh insight on how to develop my students’ research skills. I was curious to know if teachers’ thinking is visible to students and if students’ thinking is visible to teachers and this was the catalyst for my research.

This article talks about the insights gathered when Grade 2 – 5 students reflected on the challenges they face when assigned research tasks. Students’ voices unearthed how we as teachers can collaboratively play a role in bridging some gaps with simple strategies to support all learners when they are seeking information .

We can support EAL (English as an additional language) students in different ways. Learners are comfortable when paired to complete tasks using G oogle translate to research in their home language and to then present their findings with simplified expectations.

This served as a provocation to ‘Generate’ a response from all the students to express what their struggles and challenges were. Their responses were documented on sticky notes.

It surprised me that ALL students had struggles and that ALL were able to express their struggles. Their notes just showed the support that each student required from us and how.

When seeking permission from students to read their notes aloud, I initially experienced resistance from some EAL students and from the ‘not so confident’ students when having inhibitions and reservations of disclosing their struggles. Through modeling the expectation of respect when reading aloud from the few confident students who gave permission to share their work, the other EAL and ‘not so confident’ students realised the impact this could have on their learning and that they were not the only ones who had struggles/challenges. This turnaround in resistance was an “aha” moment for me .

Having ‘Generated’ a response from students I now ‘Sorted’ these into groups. This was valuable in moving their learning forward through creating a culture of learning for ALL students and in how they could support one another as many had common struggles.

“ While sorting their struggles, the role that language plays when conducting any research became evident. “

While sorting their struggles, the role that language plays when conducting any research became evident. It hinges on how students access and interpret information. This was validated as the teachers echoed the same notion.

We then ‘Connected’ with learners’ homeroom unit of inquiry to extend and ‘Elaborate’ on simple strategies we could apply.

Some simple strategies that we brainstormed and suggested -

W hen looking for information and even for images In a search, include words such as the following after the search term, ‘ for kids/primary children/junior/easy/beginners/simple/basic or a specific age 8-9 ’ , at the end after the search term . The results are more child friendly.

Ask an adult for meanings, look for meanings through the dictionary/phonetic dictionary, when you right click on the word you can explore its meaning or alternatively look for synonyms to help you find the word that fits best.

Read or watch video clips not once but twice , and reread or re-watch a couple more times if necessary.

To read the words you come across the first time – sound it out, decode/break the word into parts before you pronounce/sound the whole word, for example – com – pre – hend for comprehend.

Choose a quiet space or what works best for you, read aloud or read a bit slowly.

Pay careful attention to what you use as a keyword , and the correct spelling.

Change the way you use a keyword search by refram ing the question differently.

Reframe questions by using synonyms/different words.

Skim and scan – use a highlighter when you come across important relevant information.

Next to encourage students to empathise with how language impacts the way we access information, I made a word using shapes instead of letters – a triangle represented C, a square represented A and a circle represented T, alphabet. Students were then asked to read this.

Students were perplexed and reflected on how difficult reading in another language is, and this helped them to empathise with the EAL learners. Finding representations and translating information for EAL learners now made more sense to them.

F eedback by teachers included “Are students able to synthesize information when conducting research from various sources?”

Here I wanted students to know the meaning of the word ‘ synthesize ’ . To simplify this, I first asked 5 students about the places they visited during their holidays. These 5 students represented 5 different websites. I later asked one student to create a report when combining all that he gathered through these 5 students (5 websites). When this report was read aloud the 5 students then pointed out if their peer had forgotten to include the most important information or misinterpreted the information. This way each student was able to comprehend the concept of synthesizing.

“ Research skills can be learned and taught and improved as we practice and are developed as learners advance in age and in their levels of understanding . “

To conclude we brainstormed solutions for each of their struggles. We looked at possible strategies and steps to keep in mind when gathering information.

First step – Keyword strategies in the search box to include exactly what you are looking for with better spellings which will give better results.

Second step – taking notes of the information found

Third step – Paraphrasing and Synthesising when making meaning from the information.

Concept map strategies are also useful in organizing the information students find.

It was great to see students taking ownership of the way they could get better at information gathering research.

Research skills can be learned and taught and improved as we practice and are developed as learners advance in age and in their levels of understanding . By focus ing on language and its connection to information gathering , we can enhance students’ ‘Learning how to l earn’ to improve research skills.

Lamiya Bharmal has been a PYP Librarian and Information Literacy teacher working at Stonehill International School in Bangalore, India for 8 years. She has taught in IB PYP schools and n ational curriculum schools since 2001 and has been a homeroom teacher and primary librarian for an equal number of years . As the PYP emphasizes student voice, choice, ownership, reflection and r esearch skills, she aims to equip learners to research independently and take ownership of their learning

feedback , research , well-being

24 Responses to Approaches to learning: supporting research skills among learners through the language of instruction

Ms Lamia, I liked your process of identifying shortfall and expressing them on a sticknote.

I obeserve two things, number one identifying their own weakness and voiceout which helps the child to overcome their fear and secondly it’s a wonderful literacy activity on it’s own.

A well articulated article by Ms. Lamiya. This is so true to allow students to take ownership of research. At the same time not to forget our responsibility of mentoring and guiding them to explore different possibilities to unpack through research their own chosen topic. The exemplars are good reference for teachers and librarians for collaboration on multiple aspect of research along with ATL skills. Appreciate Ms. Lamiya sharing her absolutely empirical experience and best practice. Thanks for a very informative and useful article.

Lamiya, Thank you very much for sharing your knowledge with this amazing research which gives a very clear explanation of how we can encourage and inspire children carry our research at a very early age. I particularly resonated with the part about children’s struggle and how your tackled it using thinking strategies. Good learning for both students and teachers. Mina

Thanks Parimala for this feedback. Yes this shortfall was experienced by ALL students. As the article suggests there is a connection of language being a barrier for students to research better.

Thank you Anil for your feedback

Thank you Mina, I appreciate your feedback

Dear Lamiya, A nicely written article that addresses the ATLs in a specific way. Interesting to read the thought process of the children. The tips are well appreciated, thanks for sharing. Keep up the good work Regards Sharayu

Dear Lamiya, an interesting read, the mindset of children has been well looked into. Thanks for the tips, it will help us even when we try to build these skills in the Early Years class. Well done

Lamiya, yes, you are right; focusing on connection with language and other transdisciplinary concepts and ideas are important.

Information gathering, evaluating resources, inferencing, and providing evidence with writing are skills that need to be practised when interacting with complex information as students grow each year.

I like how you used the sticky notes and were able to match struggles with solutions. It was a cool way to map out strategies. I like to use sticky notes as a writing technique for plot structure and character development so the same “sticky” technique for organizing thoughts gets reinforced in different subjects and can become a habit for those students who connect with that technique.

Hello Ms.Lamiya, Awesome blog post. Lot of insights on the struggles the students face while researching. After reading your article, I wondered if it is only the EAL students who struggle or do all the students have some kind of struggle which might not be visible to the teacher. Thank you for this thought provoking blog post that made me think how best, we as educators can empower the student’s learning and research.

Dear Vicki, Thank you for your feedback. This was a whole circle complete for students to be able to come up with strategies to match their struggles.

Dear Sharayu, Thank you for your feedback. I think the Making Thinking Visible PD really helped me to gain this fresh insight

Thank you Sharayu for your feedback

Dear Heeru,

Thank you for your feedback. Yes language is important in gathering information and we need to provide learners with linguistic tools with which to learn as we are all language teachers as well.

Thanks Vinita for your feedback, In reply to your question – ALL students were facing struggles not only EAL which is why many times you will come across ALL written in capital letters

Thanks Vicki for your feedback. This was a whole circle complete for students to be able to come up with strategies to match their struggles. It served its purpose when students were able to reflect and to match this thus taking ownership as part of their learning.

Thanks Vicki for your feedback. A circle complete for students to be able to come up with strategies to match their struggles. It served its purpose when students were able to reflect and to match this, thus taking ownership of their learning.

Very lucid and insightful writing. I like the way you have brought out the the often ignored link between language competency and it’s consequent impact on effective research skills. On another level you could write an entire article that focuses on this critical aspect

Thank you Sapna for your encouraging words.

Excellent article Lamiya. You have given students a voice into the many ways they struggle with research. Once those struggles were identified you helped the students overcome their issues and gave them creative solutions. Very helpful article.

Thank you Sheryl for this valuable feedback, especially when it comes from someone who has been witness to this process.

I am a beginner in IB PYP. Reading this article gave me a good insight upon how ti build research skills in our learners. Moreover, I found that the pointers will help me to remember when I am actually implementing it in my classroom.

Hello Lamiya.. My PYPC just shared this article with me today – evening time. It is a very useful and insightful article both for IB or non IB school librarians. I read all the comments and I found a nice comment from a name who I look up too; Madam Heruu Bojwani. warm hi from Jakarta

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.

This site uses Akismet to reduce spam. Learn how your comment data is processed .

About the IB

The International Baccalaureate (IB) is a global leader in international education—developing inquiring, knowledgeable, confident, and caring young people. With more than 7,700 programmes being offered worldwide, across over 5,600 schools in 159 countries, an IB education is designed to develop well-rounded individuals who can respond to today’s challenges with optimism and an open mind. For over 50 years, our four programmes provide a solid, consistent framework and the flexibility to tailor students’ education according to their culture and context. To find out more, please visit www.ibo.org.

Stephanie Blog

The correct way to do your research: 5 tips for students.

Mastering the art of research is a fundamental skill that underpins academic success across all disciplines. Whether you’re embarking on a simple essay or delving into a complex thesis, the ability to conduct thorough and effective research is invaluable. Yet, many students find themselves overwhelmed by the sheer volume of information available, struggling to sift through data, discern credible sources, and organize their findings cohesively. This challenge underscores the need for a structured approach to research, one that simplifies the process while enhancing the quality of the outcomes.

Recognizing the critical role research plays in academic achievement, this article aims to demystify the process, offering five key tips to guide students toward more productive and less stressful research experiences. These strategies are designed to not only streamline your research process but also improve the caliber of your work, potentially transforming the daunting task of starting to dissertation writing help into a more manageable and even enjoyable endeavor. By applying these tips, students can develop a robust framework for research that supports academic growth and fosters confidence in their ability to tackle complex topics.

Tip 1: Define Your Research Question Clearly

A well-defined research question is the cornerstone of any successful research endeavor. It guides the direction of your study, helping to focus your efforts on finding relevant information. Start by identifying the main topic or issue you wish to explore, then narrow it down to a specific question that is both clear and concise. This question should be specific enough to provide direction but broad enough to allow for comprehensive exploration. Examples of effective research questions include “What impact does daily technology use have on teenagers’ social skills?” or “How do renewable energy sources affect global economic policies?”

Tip 2: Use Reliable Sources

The credibility of your research largely depends on the sources you choose. To ensure your work is grounded in reliable information, prioritize sources that are peer-reviewed, such as academic journals, books published by reputable publishers, and websites with authoritative domain extensions (e.g., .edu, .gov). Utilize academic databases like JSTOR, PubMed, and Google Scholar to find scholarly articles. Additionally, learning to assess the author’s credentials, the publication date and the presence of citations can help you determine the reliability of your sources.

Tip 3: Organize Your Research Efficiently

An organized research process is key to managing the wealth of information you’ll encounter. Digital tools and software, such as citation management software like Zotero or EndNote, can be incredibly helpful for keeping track of sources, notes, and bibliographies. Creating a structured outline early on, based on your preliminary findings, can guide your research and writing process, ensuring that you cover all necessary aspects of your topic systematically. This approach not only saves time but also helps maintain a clear focus throughout your project.

Tip 4: Take Effective Notes

Effective note-taking is crucial for capturing important information and ideas from your sources. Develop a system that works for you, whether it’s digital note-taking apps, traditional notebooks, or annotated bibliographies. Focus on summarizing key points in your own words, which aids comprehension and helps avoid unintentional plagiarism. Be sure to record bibliographic details for each source, making it easier to cite them correctly in your work. Highlighting or color-coding can also be useful for categorizing notes by theme or relevance.

By adhering to these foundational tips, students can enhance their research skills, leading to more insightful, well-supported academic papers. The next steps will delve into evaluating and synthesizing information, rounding out the comprehensive guide to conducting effective research.

Tip 5: Evaluate and Synthesize Information

Critical evaluation is essential to differentiate between information that genuinely supports your research question and data that is irrelevant or biased. Assess each source’s purpose, its context, and the evidence it presents. Look for patterns and relationships between the information gathered from various sources. Synthesizing this information involves integrating ideas from multiple sources to construct a comprehensive understanding of your topic. This step is crucial for developing a well-argued thesis or research paper that reflects a deep understanding of the subject matter.

Incorporating Feedback and Revising