Experimental Design: Types, Examples & Methods

Saul Mcleod, PhD

Editor-in-Chief for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MRes, PhD, University of Manchester

Saul Mcleod, PhD., is a qualified psychology teacher with over 18 years of experience in further and higher education. He has been published in peer-reviewed journals, including the Journal of Clinical Psychology.

Learn about our Editorial Process

Olivia Guy-Evans, MSc

Associate Editor for Simply Psychology

BSc (Hons) Psychology, MSc Psychology of Education

Olivia Guy-Evans is a writer and associate editor for Simply Psychology. She has previously worked in healthcare and educational sectors.

On This Page:

Experimental design refers to how participants are allocated to different groups in an experiment. Types of design include repeated measures, independent groups, and matched pairs designs.

Probably the most common way to design an experiment in psychology is to divide the participants into two groups, the experimental group and the control group, and then introduce a change to the experimental group, not the control group.

The researcher must decide how he/she will allocate their sample to the different experimental groups. For example, if there are 10 participants, will all 10 participants participate in both groups (e.g., repeated measures), or will the participants be split in half and take part in only one group each?

Three types of experimental designs are commonly used:

1. Independent Measures

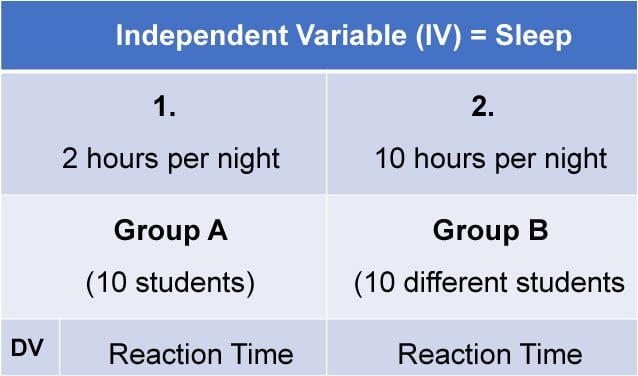

Independent measures design, also known as between-groups , is an experimental design where different participants are used in each condition of the independent variable. This means that each condition of the experiment includes a different group of participants.

This should be done by random allocation, ensuring that each participant has an equal chance of being assigned to one group.

Independent measures involve using two separate groups of participants, one in each condition. For example:

- Con : More people are needed than with the repeated measures design (i.e., more time-consuming).

- Pro : Avoids order effects (such as practice or fatigue) as people participate in one condition only. If a person is involved in several conditions, they may become bored, tired, and fed up by the time they come to the second condition or become wise to the requirements of the experiment!

- Con : Differences between participants in the groups may affect results, for example, variations in age, gender, or social background. These differences are known as participant variables (i.e., a type of extraneous variable ).

- Control : After the participants have been recruited, they should be randomly assigned to their groups. This should ensure the groups are similar, on average (reducing participant variables).

2. Repeated Measures Design

Repeated Measures design is an experimental design where the same participants participate in each independent variable condition. This means that each experiment condition includes the same group of participants.

Repeated Measures design is also known as within-groups or within-subjects design .

- Pro : As the same participants are used in each condition, participant variables (i.e., individual differences) are reduced.

- Con : There may be order effects. Order effects refer to the order of the conditions affecting the participants’ behavior. Performance in the second condition may be better because the participants know what to do (i.e., practice effect). Or their performance might be worse in the second condition because they are tired (i.e., fatigue effect). This limitation can be controlled using counterbalancing.

- Pro : Fewer people are needed as they participate in all conditions (i.e., saves time).

- Control : To combat order effects, the researcher counter-balances the order of the conditions for the participants. Alternating the order in which participants perform in different conditions of an experiment.

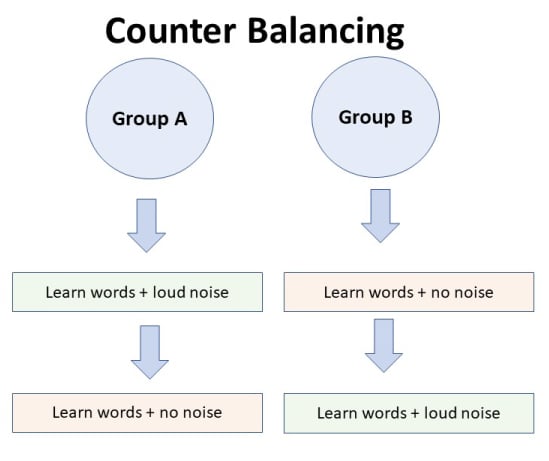

Counterbalancing

Suppose we used a repeated measures design in which all of the participants first learned words in “loud noise” and then learned them in “no noise.”

We expect the participants to learn better in “no noise” because of order effects, such as practice. However, a researcher can control for order effects using counterbalancing.

The sample would be split into two groups: experimental (A) and control (B). For example, group 1 does ‘A’ then ‘B,’ and group 2 does ‘B’ then ‘A.’ This is to eliminate order effects.

Although order effects occur for each participant, they balance each other out in the results because they occur equally in both groups.

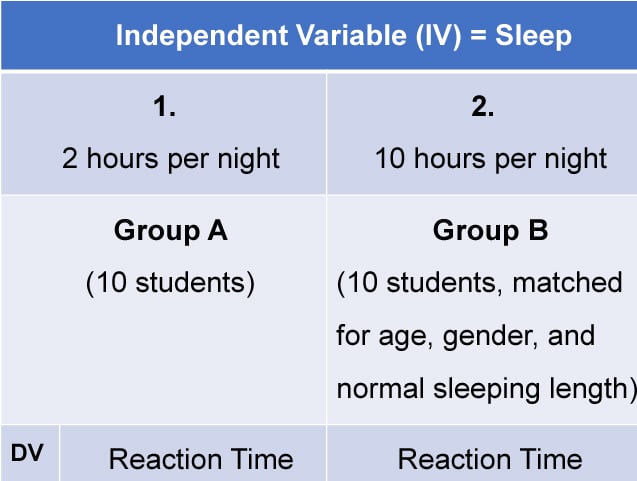

3. Matched Pairs Design

A matched pairs design is an experimental design where pairs of participants are matched in terms of key variables, such as age or socioeconomic status. One member of each pair is then placed into the experimental group and the other member into the control group .

One member of each matched pair must be randomly assigned to the experimental group and the other to the control group.

- Con : If one participant drops out, you lose 2 PPs’ data.

- Pro : Reduces participant variables because the researcher has tried to pair up the participants so that each condition has people with similar abilities and characteristics.

- Con : Very time-consuming trying to find closely matched pairs.

- Pro : It avoids order effects, so counterbalancing is not necessary.

- Con : Impossible to match people exactly unless they are identical twins!

- Control : Members of each pair should be randomly assigned to conditions. However, this does not solve all these problems.

Experimental design refers to how participants are allocated to an experiment’s different conditions (or IV levels). There are three types:

1. Independent measures / between-groups : Different participants are used in each condition of the independent variable.

2. Repeated measures /within groups : The same participants take part in each condition of the independent variable.

3. Matched pairs : Each condition uses different participants, but they are matched in terms of important characteristics, e.g., gender, age, intelligence, etc.

Learning Check

Read about each of the experiments below. For each experiment, identify (1) which experimental design was used; and (2) why the researcher might have used that design.

1 . To compare the effectiveness of two different types of therapy for depression, depressed patients were assigned to receive either cognitive therapy or behavior therapy for a 12-week period.

The researchers attempted to ensure that the patients in the two groups had similar severity of depressed symptoms by administering a standardized test of depression to each participant, then pairing them according to the severity of their symptoms.

2 . To assess the difference in reading comprehension between 7 and 9-year-olds, a researcher recruited each group from a local primary school. They were given the same passage of text to read and then asked a series of questions to assess their understanding.

3 . To assess the effectiveness of two different ways of teaching reading, a group of 5-year-olds was recruited from a primary school. Their level of reading ability was assessed, and then they were taught using scheme one for 20 weeks.

At the end of this period, their reading was reassessed, and a reading improvement score was calculated. They were then taught using scheme two for a further 20 weeks, and another reading improvement score for this period was calculated. The reading improvement scores for each child were then compared.

4 . To assess the effect of the organization on recall, a researcher randomly assigned student volunteers to two conditions.

Condition one attempted to recall a list of words that were organized into meaningful categories; condition two attempted to recall the same words, randomly grouped on the page.

Experiment Terminology

Ecological validity.

The degree to which an investigation represents real-life experiences.

Experimenter effects

These are the ways that the experimenter can accidentally influence the participant through their appearance or behavior.

Demand characteristics

The clues in an experiment lead the participants to think they know what the researcher is looking for (e.g., the experimenter’s body language).

Independent variable (IV)

The variable the experimenter manipulates (i.e., changes) is assumed to have a direct effect on the dependent variable.

Dependent variable (DV)

Variable the experimenter measures. This is the outcome (i.e., the result) of a study.

Extraneous variables (EV)

All variables which are not independent variables but could affect the results (DV) of the experiment. Extraneous variables should be controlled where possible.

Confounding variables

Variable(s) that have affected the results (DV), apart from the IV. A confounding variable could be an extraneous variable that has not been controlled.

Random Allocation

Randomly allocating participants to independent variable conditions means that all participants should have an equal chance of taking part in each condition.

The principle of random allocation is to avoid bias in how the experiment is carried out and limit the effects of participant variables.

Order effects

Changes in participants’ performance due to their repeating the same or similar test more than once. Examples of order effects include:

(i) practice effect: an improvement in performance on a task due to repetition, for example, because of familiarity with the task;

(ii) fatigue effect: a decrease in performance of a task due to repetition, for example, because of boredom or tiredness.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, generate accurate citations for free.

- Knowledge Base

Methodology

- What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples

Published on June 7, 2021 by Shona McCombes . Revised on November 20, 2023 by Pritha Bhandari.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall research objectives and approach

- Whether you’ll rely on primary research or secondary research

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research objectives and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, other interesting articles, frequently asked questions about research design.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities—start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed-methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Receive feedback on language, structure, and formatting

Professional editors proofread and edit your paper by focusing on:

- Academic style

- Vague sentences

- Style consistency

See an example

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types.

- Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships

- Descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analyzing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study—plants, animals, organizations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

- Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalize your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study , your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalize to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question .

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviors, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews .

Observation methods

Observational studies allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviors or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what kinds of data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected—for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

Here's why students love Scribbr's proofreading services

Discover proofreading & editing

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are high in reliability and validity.

Operationalization

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalization means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in—for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced, while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method , you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample—by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method , it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method , how will you avoid research bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organizing and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymize and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well-organized will save time when it comes to analyzing it. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings (high replicability ).

On its own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyze the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarize your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarize your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analyzing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

If you want to know more about the research process , methodology , research bias , or statistics , make sure to check out some of our other articles with explanations and examples.

- Simple random sampling

- Stratified sampling

- Cluster sampling

- Likert scales

- Reproducibility

Statistics

- Null hypothesis

- Statistical power

- Probability distribution

- Effect size

- Poisson distribution

Research bias

- Optimism bias

- Cognitive bias

- Implicit bias

- Hawthorne effect

- Anchoring bias

- Explicit bias

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question . It defines your overall approach and determines how you will collect and analyze data.

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims, that you collect high-quality data, and that you use the right kind of analysis to answer your questions, utilizing credible sources . This allows you to draw valid , trustworthy conclusions.

Quantitative research designs can be divided into two main categories:

- Correlational and descriptive designs are used to investigate characteristics, averages, trends, and associations between variables.

- Experimental and quasi-experimental designs are used to test causal relationships .

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible. Common types of qualitative design include case study , ethnography , and grounded theory designs.

The priorities of a research design can vary depending on the field, but you usually have to specify:

- Your research questions and/or hypotheses

- Your overall approach (e.g., qualitative or quantitative )

- The type of design you’re using (e.g., a survey , experiment , or case study )

- Your data collection methods (e.g., questionnaires , observations)

- Your data collection procedures (e.g., operationalization , timing and data management)

- Your data analysis methods (e.g., statistical tests or thematic analysis )

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population . Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research. For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

In statistics, sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population.

Operationalization means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioral avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalize the variables that you want to measure.

A research project is an academic, scientific, or professional undertaking to answer a research question . Research projects can take many forms, such as qualitative or quantitative , descriptive , longitudinal , experimental , or correlational . What kind of research approach you choose will depend on your topic.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the “Cite this Scribbr article” button to automatically add the citation to our free Citation Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, November 20). What Is a Research Design | Types, Guide & Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved April 2, 2024, from https://www.scribbr.com/methodology/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

Other students also liked, guide to experimental design | overview, steps, & examples, how to write a research proposal | examples & templates, ethical considerations in research | types & examples, what is your plagiarism score.

Have a language expert improve your writing

Run a free plagiarism check in 10 minutes, automatically generate references for free.

- Knowledge Base

- Methodology

Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples

Published on 5 May 2022 by Shona McCombes . Revised on 20 March 2023.

A research design is a strategy for answering your research question using empirical data. Creating a research design means making decisions about:

- Your overall aims and approach

- The type of research design you’ll use

- Your sampling methods or criteria for selecting subjects

- Your data collection methods

- The procedures you’ll follow to collect data

- Your data analysis methods

A well-planned research design helps ensure that your methods match your research aims and that you use the right kind of analysis for your data.

Table of contents

Step 1: consider your aims and approach, step 2: choose a type of research design, step 3: identify your population and sampling method, step 4: choose your data collection methods, step 5: plan your data collection procedures, step 6: decide on your data analysis strategies, frequently asked questions.

- Introduction

Before you can start designing your research, you should already have a clear idea of the research question you want to investigate.

There are many different ways you could go about answering this question. Your research design choices should be driven by your aims and priorities – start by thinking carefully about what you want to achieve.

The first choice you need to make is whether you’ll take a qualitative or quantitative approach.

Qualitative research designs tend to be more flexible and inductive , allowing you to adjust your approach based on what you find throughout the research process.

Quantitative research designs tend to be more fixed and deductive , with variables and hypotheses clearly defined in advance of data collection.

It’s also possible to use a mixed methods design that integrates aspects of both approaches. By combining qualitative and quantitative insights, you can gain a more complete picture of the problem you’re studying and strengthen the credibility of your conclusions.

Practical and ethical considerations when designing research

As well as scientific considerations, you need to think practically when designing your research. If your research involves people or animals, you also need to consider research ethics .

- How much time do you have to collect data and write up the research?

- Will you be able to gain access to the data you need (e.g., by travelling to a specific location or contacting specific people)?

- Do you have the necessary research skills (e.g., statistical analysis or interview techniques)?

- Will you need ethical approval ?

At each stage of the research design process, make sure that your choices are practically feasible.

Prevent plagiarism, run a free check.

Within both qualitative and quantitative approaches, there are several types of research design to choose from. Each type provides a framework for the overall shape of your research.

Types of quantitative research designs

Quantitative designs can be split into four main types. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs allow you to test cause-and-effect relationships, while descriptive and correlational designs allow you to measure variables and describe relationships between them.

With descriptive and correlational designs, you can get a clear picture of characteristics, trends, and relationships as they exist in the real world. However, you can’t draw conclusions about cause and effect (because correlation doesn’t imply causation ).

Experiments are the strongest way to test cause-and-effect relationships without the risk of other variables influencing the results. However, their controlled conditions may not always reflect how things work in the real world. They’re often also more difficult and expensive to implement.

Types of qualitative research designs

Qualitative designs are less strictly defined. This approach is about gaining a rich, detailed understanding of a specific context or phenomenon, and you can often be more creative and flexible in designing your research.

The table below shows some common types of qualitative design. They often have similar approaches in terms of data collection, but focus on different aspects when analysing the data.

Your research design should clearly define who or what your research will focus on, and how you’ll go about choosing your participants or subjects.

In research, a population is the entire group that you want to draw conclusions about, while a sample is the smaller group of individuals you’ll actually collect data from.

Defining the population

A population can be made up of anything you want to study – plants, animals, organisations, texts, countries, etc. In the social sciences, it most often refers to a group of people.

For example, will you focus on people from a specific demographic, region, or background? Are you interested in people with a certain job or medical condition, or users of a particular product?

The more precisely you define your population, the easier it will be to gather a representative sample.

Sampling methods

Even with a narrowly defined population, it’s rarely possible to collect data from every individual. Instead, you’ll collect data from a sample.

To select a sample, there are two main approaches: probability sampling and non-probability sampling . The sampling method you use affects how confidently you can generalise your results to the population as a whole.

Probability sampling is the most statistically valid option, but it’s often difficult to achieve unless you’re dealing with a very small and accessible population.

For practical reasons, many studies use non-probability sampling, but it’s important to be aware of the limitations and carefully consider potential biases. You should always make an effort to gather a sample that’s as representative as possible of the population.

Case selection in qualitative research

In some types of qualitative designs, sampling may not be relevant.

For example, in an ethnography or a case study, your aim is to deeply understand a specific context, not to generalise to a population. Instead of sampling, you may simply aim to collect as much data as possible about the context you are studying.

In these types of design, you still have to carefully consider your choice of case or community. You should have a clear rationale for why this particular case is suitable for answering your research question.

For example, you might choose a case study that reveals an unusual or neglected aspect of your research problem, or you might choose several very similar or very different cases in order to compare them.

Data collection methods are ways of directly measuring variables and gathering information. They allow you to gain first-hand knowledge and original insights into your research problem.

You can choose just one data collection method, or use several methods in the same study.

Survey methods

Surveys allow you to collect data about opinions, behaviours, experiences, and characteristics by asking people directly. There are two main survey methods to choose from: questionnaires and interviews.

Observation methods

Observations allow you to collect data unobtrusively, observing characteristics, behaviours, or social interactions without relying on self-reporting.

Observations may be conducted in real time, taking notes as you observe, or you might make audiovisual recordings for later analysis. They can be qualitative or quantitative.

Other methods of data collection

There are many other ways you might collect data depending on your field and topic.

If you’re not sure which methods will work best for your research design, try reading some papers in your field to see what data collection methods they used.

Secondary data

If you don’t have the time or resources to collect data from the population you’re interested in, you can also choose to use secondary data that other researchers already collected – for example, datasets from government surveys or previous studies on your topic.

With this raw data, you can do your own analysis to answer new research questions that weren’t addressed by the original study.

Using secondary data can expand the scope of your research, as you may be able to access much larger and more varied samples than you could collect yourself.

However, it also means you don’t have any control over which variables to measure or how to measure them, so the conclusions you can draw may be limited.

As well as deciding on your methods, you need to plan exactly how you’ll use these methods to collect data that’s consistent, accurate, and unbiased.

Planning systematic procedures is especially important in quantitative research, where you need to precisely define your variables and ensure your measurements are reliable and valid.

Operationalisation

Some variables, like height or age, are easily measured. But often you’ll be dealing with more abstract concepts, like satisfaction, anxiety, or competence. Operationalisation means turning these fuzzy ideas into measurable indicators.

If you’re using observations , which events or actions will you count?

If you’re using surveys , which questions will you ask and what range of responses will be offered?

You may also choose to use or adapt existing materials designed to measure the concept you’re interested in – for example, questionnaires or inventories whose reliability and validity has already been established.

Reliability and validity

Reliability means your results can be consistently reproduced , while validity means that you’re actually measuring the concept you’re interested in.

For valid and reliable results, your measurement materials should be thoroughly researched and carefully designed. Plan your procedures to make sure you carry out the same steps in the same way for each participant.

If you’re developing a new questionnaire or other instrument to measure a specific concept, running a pilot study allows you to check its validity and reliability in advance.

Sampling procedures

As well as choosing an appropriate sampling method, you need a concrete plan for how you’ll actually contact and recruit your selected sample.

That means making decisions about things like:

- How many participants do you need for an adequate sample size?

- What inclusion and exclusion criteria will you use to identify eligible participants?

- How will you contact your sample – by mail, online, by phone, or in person?

If you’re using a probability sampling method, it’s important that everyone who is randomly selected actually participates in the study. How will you ensure a high response rate?

If you’re using a non-probability method, how will you avoid bias and ensure a representative sample?

Data management

It’s also important to create a data management plan for organising and storing your data.

Will you need to transcribe interviews or perform data entry for observations? You should anonymise and safeguard any sensitive data, and make sure it’s backed up regularly.

Keeping your data well organised will save time when it comes to analysing them. It can also help other researchers validate and add to your findings.

On their own, raw data can’t answer your research question. The last step of designing your research is planning how you’ll analyse the data.

Quantitative data analysis

In quantitative research, you’ll most likely use some form of statistical analysis . With statistics, you can summarise your sample data, make estimates, and test hypotheses.

Using descriptive statistics , you can summarise your sample data in terms of:

- The distribution of the data (e.g., the frequency of each score on a test)

- The central tendency of the data (e.g., the mean to describe the average score)

- The variability of the data (e.g., the standard deviation to describe how spread out the scores are)

The specific calculations you can do depend on the level of measurement of your variables.

Using inferential statistics , you can:

- Make estimates about the population based on your sample data.

- Test hypotheses about a relationship between variables.

Regression and correlation tests look for associations between two or more variables, while comparison tests (such as t tests and ANOVAs ) look for differences in the outcomes of different groups.

Your choice of statistical test depends on various aspects of your research design, including the types of variables you’re dealing with and the distribution of your data.

Qualitative data analysis

In qualitative research, your data will usually be very dense with information and ideas. Instead of summing it up in numbers, you’ll need to comb through the data in detail, interpret its meanings, identify patterns, and extract the parts that are most relevant to your research question.

Two of the most common approaches to doing this are thematic analysis and discourse analysis .

There are many other ways of analysing qualitative data depending on the aims of your research. To get a sense of potential approaches, try reading some qualitative research papers in your field.

A sample is a subset of individuals from a larger population. Sampling means selecting the group that you will actually collect data from in your research.

For example, if you are researching the opinions of students in your university, you could survey a sample of 100 students.

Statistical sampling allows you to test a hypothesis about the characteristics of a population. There are various sampling methods you can use to ensure that your sample is representative of the population as a whole.

Operationalisation means turning abstract conceptual ideas into measurable observations.

For example, the concept of social anxiety isn’t directly observable, but it can be operationally defined in terms of self-rating scores, behavioural avoidance of crowded places, or physical anxiety symptoms in social situations.

Before collecting data , it’s important to consider how you will operationalise the variables that you want to measure.

The research methods you use depend on the type of data you need to answer your research question .

- If you want to measure something or test a hypothesis , use quantitative methods . If you want to explore ideas, thoughts, and meanings, use qualitative methods .

- If you want to analyse a large amount of readily available data, use secondary data. If you want data specific to your purposes with control over how they are generated, collect primary data.

- If you want to establish cause-and-effect relationships between variables , use experimental methods. If you want to understand the characteristics of a research subject, use descriptive methods.

Cite this Scribbr article

If you want to cite this source, you can copy and paste the citation or click the ‘Cite this Scribbr article’ button to automatically add the citation to our free Reference Generator.

McCombes, S. (2023, March 20). Research Design | Step-by-Step Guide with Examples. Scribbr. Retrieved 2 April 2024, from https://www.scribbr.co.uk/research-methods/research-design/

Is this article helpful?

Shona McCombes

- Technical Support

- Find My Rep

You are here

Research Methods and Design in Psychology

- Paul Richardson - Sheffield Hallam University, UK

- Allen Goodwin - Sheffield Hallam University, UK

- Emma Vine - Sheffield Hallam University, UK

- Description

Activities help readers build the underpinning generic critical thinking and transferable skills they need in order to become independent learners, and to meet the relevant requirements of their programme of study.

The text provides core information on designing psychology research studies with key chapters on both quantitative and qualitative designs. Other chapters look at ethics, common problems, and advances and innovations.

See what’s new to this edition by selecting the Features tab on this page. Should you need additional information or have questions regarding the HEOA information provided for this title, including what is new to this edition, please email [email protected] . Please include your name, contact information, and the name of the title for which you would like more information. For information on the HEOA, please go to http://ed.gov/policy/highered/leg/hea08/index.html .

For assistance with your order: Please email us at [email protected] or connect with your SAGE representative.

SAGE 2455 Teller Road Thousand Oaks, CA 91320 www.sagepub.com

Excellent book that will be recommended for my students preparing a research project.

Great resource for those new to research

Thanks. Very interesting overview with good examples.

What a perfect text book for level 4? Absolutely what i was looking for.

This is a great starting point for students who want a clear and basic introduction to \research methods. Each chapter takes you through an understanding of the various components you will need to consider in a Undergraduate Reseach project.

A thorough grounding in the key areas of research design and the application of various research methods. well structured and very easy to follow. A good text for social work students to see the range of methods and how they can be used.

Complete, accessible, very well structured

A powerpack for starting researchers. Really informative introductions to a couple of different resarch designs and into data analysis.

Not a suitable scholarly level for our students

Our existing texts had this material covered.

Preview this book

For instructors, select a purchasing option, related products.

Research Methods in Psychology - 4th American Edition

(40 reviews)

Carrie Cuttler, Washington State University

Rajiv S. Jhangiani, Kwantlen Polytechnic University

Dana C. Leighton, Texas A&M University, Texarkana

Copyright Year: 2019

ISBN 13: 9781999198107

Publisher: Kwantlen Polytechnic University

Language: English

Formats Available

Conditions of use.

Learn more about reviews.

Reviewed by Beth Mechlin, Associate Professor of Psychology & Neuroscience, Earlham College on 3/19/24

This is an extremely comprehensive text for an undergraduate psychology course about research methods. It does an excellent job covering the basics of a variety of types of research design. It also includes important topics related to research... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 5 see less

This is an extremely comprehensive text for an undergraduate psychology course about research methods. It does an excellent job covering the basics of a variety of types of research design. It also includes important topics related to research such as ethics, finding journal articles, and writing reports in APA format.

Content Accuracy rating: 5

I did not notice any errors in this text.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 5

The content is very relevant. It will likely need to be updated over time in order to keep research examples relevant. Additionally, APA formatting guidelines may need to be updated when a new publication manual is released. However, these should be easy updates for the authors to make when the time comes.

Clarity rating: 5

This text is very clear and easy to follow. The explanations are easy for college students to understand. The authors use a lot of examples to help illustrate specific concepts. They also incorporate a variety of relevant outside sources (such as videos) to provide additional examples.

Consistency rating: 5

The text is consistent and flows well from one section to the next. At the end of each large section (similar to a chapter) the authors provide key takeaways and exercises.

Modularity rating: 5

This text is very modular. It is easy to pick and choose which sections you want to use in your course when. Each section can stand alone fairly easily.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 5

The text is very well organized. Information flows smoothly from one topic to the next.

Interface rating: 5

The interface is great. The text is easy to navigate and the images display well (I only noticed 1 image in which the formatting was a tad off).

Grammatical Errors rating: 5

I did not notice any grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 5

The text is culturally relevant.

This is an excellent text for an undergraduate research methods course in the field of Psychology. I have been using the text for my Research Methods and Statistics course for a few years now. This text focuses on research methods, so I do use another text to cover statistical information. I do highly recommend this text for research methods. It is comprehensive, clear, and easy for students to use.

Reviewed by William Johnson, Lecturer, Old Dominion University on 1/12/24

This textbook covers every topic that I teach in my Research Methods course aside from psychology careers (which I would not really expect it to cover). read more

This textbook covers every topic that I teach in my Research Methods course aside from psychology careers (which I would not really expect it to cover).

I have not noticed any inaccurate information (other than directed students to read Malcolm Gladwell). I appreciate that the textbook includes information on research errors that have not been supported by replication efforts, such as embodied cognition.

Many of the basic concepts of research methods are rather timeless, but I appreciate that the text includes newer research as examples while also including "classic" studies that exemplify different methods.

The writing is clear and simple. The keywords are bolded and reveal a definition when clicked, which students often find very helpful. Many of the figures are very helpful in helping students understand various methods (I really like the ones in the single-subject design subchapter).

The book is very consistent in its terminology and writing style, which I see as a positive compared to other open psychology textbooks where each chapter is written by subject matter experts (such as the NOBA intro textbook).

Modularity rating: 4

I teach this textbook almost entirely in order (except for moving chapters 12 & 13 earlier in the semester to aid students in writing Results sections in their final papers). I think that the organization and consistency of the book reduces its modularity, in that earlier chapters are genuinely helpful for later chapters.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 4

I preferred the organization of previous editions, which had "Theory in Research" as its own chapter. If I were organizing the textbook, I am not sure that I would have out descriptive or inferential statistics as the final two chapters (I would have likely put Chapter 11: Presenting Your Research as the final chapter). I also would not have put information about replicability and open science in the inferential statistics section.

The text is easy to read and the formatting is attractive. My only minor complaint is that some of the longer subchapters can be a pretty long scroll, but I understand the desire for their only to be one page per subchapter/topic.

I have not noticed any grammatical errors.

Cultural Relevance rating: 3

I do not think the textbook is insensitive, but there is not much thought given to adapting research instruments across cultures. For instance, talking about how different constructs might have different underlying distributions in different cultures would be useful for students. In the survey methods section, a discussion of back translation or emic personality trait measurement/development for example might be a nice addition.

I choose to use this textbook in my methods classes, but I do miss the organization of the previous American editions. Overall, I recommend this textbook to my colleagues.

Reviewed by Brianna Ewert, Psychology Instructor, Salish Kootenai College on 12/30/22

This text includes the majority of content included in our undergraduate Research Methods in Psychology course. The glossary provides concise definitions of key terms. This text includes most of the background knowledge we expect our students to... read more

Comprehensiveness rating: 4 see less

This text includes the majority of content included in our undergraduate Research Methods in Psychology course. The glossary provides concise definitions of key terms. This text includes most of the background knowledge we expect our students to have as well as skill-based sections that will support them in developing their own research projects.

The content I have read is accurate and error-free.

The content is relevant and up-to-date.

The text is clear and concise. I find it pleasantly readable and anticipate undergraduate students will find it readable and understandable as well.

The terminology appears to be consistent throughout the text.

The modular sections stand alone and lend themselves to alignment with the syllabus of a particular course. I anticipate readily selecting relevant modules to assign in my course.

The book is logically organized with clear and section headings and subheadings. Content on a particular topic is easy to locate.

The text is easy to navigate and the format/design are clean and clear. There are not interface issues, distortions or distracting format in the pdf or online versions.

The text is grammatically correct.

Cultural Relevance rating: 4

I have not found culturally insensitive and offensive language or content in the text. For my courses, I would add examples and supplemental materials that are relevant for students at a Tribal College.

This textbook includes supplemental instructor materials, included slides and worksheets. I plan to adopt this text this year in our Research Methods in Psychology course. I expect it to be a benefit to the course and students.

Reviewed by Sara Peters, Associate Professor of Psychology, Newberry College on 11/3/22

This text serves as an excellent resource for introducing survey research methods topics to undergraduate students. It begins with a background of the science of psychology, the scientific method, and research ethics, before moving into the main... read more

This text serves as an excellent resource for introducing survey research methods topics to undergraduate students. It begins with a background of the science of psychology, the scientific method, and research ethics, before moving into the main types of research. This text covers experimental, non-experimental, survey, and quasi-experimental approaches, among others. It extends to factorial and single subject research, and within each topic is a subset (such as observational research, field studies, etc.) depending on the section.

I could find no accuracy issues with the text, and appreciated the discussions of research and cited studies.

There are revised editions of this textbook (this being the 4th), and the examples are up to date and clear. The inclusion of exercises at the end of each chapter offer potential for students to continue working with material in meaningful ways as they move through the book and (and course).

The prose for this text is well aimed at the undergraduate population. This book can easily be utilized for freshman/sophomore level students. It introduces the scientific terminology surrounding research methods and experimental design in a clear way, and the authors provide extensive examples of different studies and applications.

Terminology is consistent throughout the text. Aligns well with other research methods and statistics sources, so the vocabulary is transferrable beyond the text itself.

Navigating this book is a breeze. There are 13 chapters, and each have subsections that can be assigned. Within each chapter subsection, there is a set of learning objectives, and paragraphs are mixed in with tables and figures for students to have different visuals. Different application assignments within each chapter are highlighted with boxes, so students can think more deeply given a set of constructs as they consider different information. The last subsection in each chapter has key summaries and exercises.

The sections and topics in this text are very straightforward. The authors begin with an introduction of psychology as a science, and move into the scientific method, research ethics, and psychological measurement. They then present multiple different research methodologies that are well known and heavily utilized within the social sciences, before concluding with information on how to present your research, and also analyze your data. The text even provides links throughout to other free resources for a reader.

This book can be navigated either online (using a drop-down menu), or as a pdf download, so students can have an electronic copy if needed. All pictures and text display properly on screen, with no distortions. Very easy to use.

There were no grammatical errors, and nothing distracting within the text.

This book includes inclusive material in the discussion of research ethics, as well as when giving examples of the different types of research approaches. While there is always room for improvement in terms of examples, I was satisfied with the breadth of research the authors presented.

This text provides an overview of both research methods, and a nice introduction to statistics for a social science student. It would be a good choice for a survey research methods class, and if looking to change a statistics class into an open resource class, could also serve as a great resource.

Reviewed by Sharlene Fedorowicz, Adjunct Professor, Bridgewater State University on 6/23/21

The comprehensiveness of this book was appropriate for an introductory undergraduate psychology course. Critical topics are covered that are necessary for psychology students to obtain foundational learning concepts for research. Sections within... read more

The comprehensiveness of this book was appropriate for an introductory undergraduate psychology course. Critical topics are covered that are necessary for psychology students to obtain foundational learning concepts for research. Sections within the text and each chapter provide areas for class discussion with students to dive deeper into key concepts for better learning comprehension. The text covered APA format along with examples of research studies to supplement the learning. The text segues appropriately by introducing the science of psychology, followed by scientific method and ethics before getting into the core of scientific research in the field of psychology. Details are provided in quantitative and qualitative research, correlations, surveys, and research design. Overall, the text is fully comprehensive and necessary introductory research concepts.

The text appears to be accurate with no issues related to content.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 4

The text provided relevant research information to support the learning. The content was up-to-date with a variety of different examples related to the different fields of psychology. However, some topics such as in the pseudoscience section were not very relevant and bordered the line of beliefs. Here, more current or relevant solid examples would provide more relevancy in this part of the text. Bringing in more solid or concrete examples that are more current for students may have been more appropriate such as lack of connection between information found on social media versus real science.

The language and flow of the chapters accompanied by the terms, concepts, and examples of applied research allows for clarity of learning content. Terms were introduced at the appropriate time with the support of concepts and current or classic research. The writing style flows nicely and segues easily from concept to concept. The text is easy for students to understand and grasp the details related to psychological research and science.

The text provides consistency in the outline of each chapter. The beginning section chapter starts objectives as an overview to help students unpack the learning content. Key terms are consistently bolded followed by concept or definition and relevant examples. Research examples are pertinent and provide students with an opportunity to understand application of the contents. Practice exercises are provided with in the chapter and at the and in order for students to integrate learning concepts from within the text.

Sections and subsections are clearly organized and divided appropriately for ease-of-use. The topics are easily discernible and follow the flow of ideal learning routines for students. The sections and subsections are consistently outlined for each concept module. The modularity provides consistency allowing for students to focus on content rather than trying to discern how to pull out the information differently from each chapter or section. In addition, each section and subsection allow for flexibility in learning or expanding concepts within the content area.

The organization of the textbook was easy to follow and each major topic was outlined clearly. However, the chapter on presenting research may be more appropriately placed toward the end of the book rather than in the middle of the chapters related to research and research design. In addition, more information could have been provided upfront around APA format so that students could identify the format of citations within the text as practice for students throughout the book.

The interface of the book lends itself to a nice layout with appropriate examples and links to break up the different sections in the chapters. Examples where appropriate and provided engagement opportunities for the students for each learning module. Images and QR codes or easily viewed and used. Key terms are highlighted in relevant figures, graphs, and tables were appropriately placed. Overall, the interface of the text assisted with the organization and flow of learning material.

No grammatical errors were detected in this book.

The text appears to be culturally sensitive and not offensive. A variety of current and classic research examples are relevant. However, more examples of research from women, minorities, and ethnicities would strengthen the culture of this textbook. Instructors may need to supplement some research in this area to provide additional inclusivity.

Overall, I was impressed by the layout of the textbook and the ease of use. The layout provides a set of expectations for students related to the routine of how the book is laid out and how students will be able to unpack the information. Research examples were relevant, although I see areas where I will supplement information. The book provides opportunities for students to dive deeper into the learning and have rich conversations in the classroom. I plan to start using the psychology textbook for my students starting next year.

Reviewed by Anna Behler, Assistant Professo, North Carolina State University on 6/1/21

The text is very thorough and covers all of the necessary topics for an undergraduate psychology research methods course. There is even coverage of qualitative research, case studies, and the replication crisis which I have not seen in some other... read more

The text is very thorough and covers all of the necessary topics for an undergraduate psychology research methods course. There is even coverage of qualitative research, case studies, and the replication crisis which I have not seen in some other texts.

There were no issues with the accuracy of the text.

The content is very up to date and relevant for a research methods course. The only updates that will likely be necessary in the coming years are updates to examples and modifications to the section on APA formatting.

The clarity of the writing was good, and the chapters were written in a way that was accessible and easy to follow.

I did not note any issues with consistency.

Each chapter is divided into multiple subsections. This makes the chapters even easier to read, as they are broken down into short and easy to navigate sections. These sections make it easy to assign readings as needed depending on which topics are being covered in class.

Organization/Structure/Flow rating: 3

The organization was one of the few areas of weakness, and I felt that the chapters were ordered somewhat oddly. However, this is something that is easily fixed, as chapters (and even subsections) can be assigned in whatever order is needed.

There were no issues of note with the interface, and the PDF of the text was easy to navigate.

The text was well written and there were no grammatical/writing errors of note.

Overall, the book did not contain any notable instances of bias. However, it would probably be appropriate to offer a more thorough discussion of the WEIRD problem in psychology research.

Reviewed by Seth Surgan, Professor, Worcester State University on 5/24/21

Pitched very well for a 200-level Research Methods course. This text provided students with solid basis for class discussion and the further development of their understanding of fundamental concepts. read more

Pitched very well for a 200-level Research Methods course. This text provided students with solid basis for class discussion and the further development of their understanding of fundamental concepts.

No issues with accuracy.

Coverage was on target, relevant, and applicable, with good examples from a variety of subfields within Psychology.

Clearly written -- students often struggle with the dry, technical nature of concepts in Research Methods. Part of the reason I chose this text in the first place was how favorably it compared to other options in terms of clarity.

No problems with inconsistent of shifting language. This is extremely important in Research Methods, where there are many closely related terms. Language was consistent and compatible with other textbook options that were available to my students.

Chapters are broken down into sections that are reasonably sized and conceptually appropriate.

The organization of this textbook fit perfectly with the syllabus I've been using (in one form or another) for 15+ years.

This textbook was easy to navigate and available in a variety of formats.

No problems at all.

Examples show an eye toward inclusivity. I did not detect any insensitive or offensive examples or undertones.

I have used this textbook for a 200-level Research Methods course run over a single summer session. This was my first experience using an OER textbook and I don't plan on going back.

Reviewed by Laura Getz, Assistant Professor, University of San Diego on 4/29/21

The topics covered seemed to be at an appropriate level for beginner undergraduate psychology students; the learning objectives for each subsection and the key takeaways and exercises for each chapter are also very helpful in guiding students’... read more

The topics covered seemed to be at an appropriate level for beginner undergraduate psychology students; the learning objectives for each subsection and the key takeaways and exercises for each chapter are also very helpful in guiding students’ attention to what is most relevant. The glossary is also thorough and a good resource for clear definitions. I would like to see a final chapter on a “big picture” or integrating key ideas of replication, meta-analysis, and open science.

Content Accuracy rating: 4

For the most part, I like the way information is presented. I had a few specific issues with definitions for ordinal variables being quantitative (1st, 2nd, 3rd aren’t really numbers as much as ranked categories), the lack of specificity about different forms of validity (face, content, criterion, and discriminant all just labeled “validity” whereas internal and external validity appear in different sections), and the lack of clear distinction between correlational and quasi-experimental variables (e.g., in some places, country of origin is listed as making a design quasi-experimental, but in other chapters it is defined as correlational).

Some of the specific studies/experiments mentioned do not seem like the best or most relevant for students to learn about the topics, but for the most part, content is up-to-date and can definitely be updated with new studies to illustrate concepts with relative ease.

Besides the few concepts I listed above in “accuracy”, I feel the text was very accessible, provides clear definitions, and many examples to illustrate any potential technical/jargon terms.

I did not notice any issues with inconsistent terms except for terms that do have more than one way of describing the same concept (e.g., 2-sample vs. independent samples t-test)

I assigned the chapters out of order with relative ease, and students did not comment about it being burdensome to navigate.

The order of chapters sometimes did not make sense to me (e.g., Experimental before Non-experimental designs, Quasi-experimental designs separate from other non-experimental designs, waiting until Chapter 11 to talk about writing), but for the most part, the chapter subsections were logical and clear.

Interface rating: 4

I had no issues navigating the online version of the textbook other than taking a while to figure out how to move forward and back within the text itself rather than going back to the table of contents (this might just be a browser issue, but is still worth considering).

No grammatical errors of note.

There was nothing explicitly insensitive or offensive about the text, but there were many places where I felt like more focus on diversity and individual differences could be helpful. For example, ethics and history of psychological testing would definitely be a place to bring in issues of systemic racism and/or sexism and a focus on WEIRD samples (which is mentioned briefly at another point).

I was very satisfied with this free resource overall, and I recommend it for beginning level undergraduate psychology research methods courses.

Reviewed by Laura Stull, Associate Professor, Anderson University on 4/23/21

This book covers essential topics and areas related to conducting introductory psychological research. It covers all critical topics, including the scientific method, research ethics, research designs, and basic descriptive and inferential... read more

This book covers essential topics and areas related to conducting introductory psychological research. It covers all critical topics, including the scientific method, research ethics, research designs, and basic descriptive and inferential statistics. It even goes beyond other texts in terms of offering specific guidance in areas like how to conduct research literature searches and psychological measurement development. The only area that appears slightly lacking is detailed guidance in the mechanics of writing in APA style (though excellent basic information is provided in chapter 11).

All content appears accurate. For example, experimental designs discussed, descriptive and inferential statistical guidance, and critical ethical issues are all accurately addressed, See comment on relevance below regarding some outdated information.

Relevance/Longevity rating: 3

Chapter 11 on APA style does not appear to cover the most current version of the APA style guide (7th edition). While much of the information in Chapter 11 is still current, there are specifics that did change from 6th to 7th edition of the APA manual and so, in order to be current, this information would have to be supplemented with external sources.

The book is extremely well organized, written in language and terms that should be easily understood by undergraduate freshmen, and explains all necessary technical jargon.

The text is consistent throughout in terms of terminology and the organizational framework (which aids in the readability of the text).

The text is divided into intuitive and common units based on basic psychological research methodology. It is clear and easy to follow and is divided in a way that would allow omission of some information if necessary (such as "single subject research") or reorganization of information (such as presenting survey research before experimental research) without disruption to the course as a whole.

As stated previously, the book is organized in a clear and logical fashion. Not only are the chapters presented in a logical order (starting with basic and critical information like overviews of the scientific method and research ethics and progressing to more complex topics like statistical analyses).

No issues with interface were noted. Helpful images/charts/web resources (e.g., Youtube videos) are embedded throughout and are even easy to follow in a print version of the text.

No grammatical issues were noted.

No issues with cultural bias are noted. Examples are included that address topics that are culturally sensitive in nature.

I ordered a print version of the text so that I could also view it as students would who prefer a print version. I am extremely impressed with what is offered. It covers all of the key content that I am currently covering with a (non-open source) textbook in an introduction to research methods course. The only concern I have is that APA style is not completely current and would need to be supplemented with a style guide. However, I consider this a minimal issue given all of the many strengths of the book.

Reviewed by Anika Gearhart, Instructor (TT), Leeward Community College on 4/22/21

Includes the majority of elements you expect from a textbook covering research methods. Some topics that could have been covered in a bit more depth were factorial research designs (no coverage of 3 or more independent variables) and external... read more

Includes the majority of elements you expect from a textbook covering research methods. Some topics that could have been covered in a bit more depth were factorial research designs (no coverage of 3 or more independent variables) and external validity (or the validities in general).

Nothing found that was inaccurate.

Looks like a few updates could be made to chapter 11 to bring it up to date with APA 7. Otherwise, most examples are current.

Very clear, a great fit for those very new to the topic.

The framework is clear and logical, and the learning objectives are very helpful for orienting the reader immediately to the main goals of each section.

Subsections are well-organized and clear. Titles for sections and subsections are clear.

Though I think the flow of this textbook for the most part is excellent, I would make two changes: move chapter 5 down with the other chapters on experimental research and move chapter 11 to the very end. I feel that this would allow for a more logical presentation of content.

The webpage navigation is easy to use and intuitive, the ebook download works as designed, and the page can be embedded directly into a variety of LMS sites or used with a variety of devices.

I found no grammatical errors in this book.

While there were some examples of studies that included participants from several cultures, the book does not touch on ecological validity, an important external validity issue tied to cultural psychology, and there is no mention of the WEIRD culture issue in psychology, which seems somewhat necessary when orienting new psychology students to research methods today.

I currently use and enjoy this textbook in my research methods class. Overall, it has been a great addition to the course, and I am easily able to supplement any areas that I feel aren't covered with enough breadth.

Reviewed by Amy Foley, Instructor/Field & Clinical Placement Coordinator, University of Indianapolis on 3/11/21

This text provides a comprehensive overview of the research process from ideation to proposal. It covers research designs common to psychology and related fields. read more

This text provides a comprehensive overview of the research process from ideation to proposal. It covers research designs common to psychology and related fields.

Accurate information!

This book is current and lines up well with the music therapy research course I teach as a supplemental text for students to understand research designs.

Clear language for psychology and related fields.

The format of the text is consistent. I appreciate the examples, different colored boxes, questions, and links to external sources such as video clips.

It is easy to navigate this text by chapters and smaller units within each chapter. The only confusion that has come from using this text includes the fact that the larger units have roman numerals and the individual chapters have numbers. I have told students to "read unit six" and they only read the small chapter 6, not the entire unit for example.

Flows well!

I have not experienced any interface issues.

I have not found any grammar errors.

Book appears culturally relevant.

This is a great resource for research methods courses in psychology or related fields. I am glad to have used several chapters of this text within the music therapy research course I teach where students learn about research design and then create their own research proposal.

Reviewed by Veronica Howard, Associate Professor, University of Alaska Anchorage on 1/11/21, updated 1/11/21

VERY impressed by the coverage of single subject designs. I would recommend this content to colleagues. read more

VERY impressed by the coverage of single subject designs. I would recommend this content to colleagues.

Content appears accurate.