You are using an outdated browser. Please upgrade your browser to improve your experience and security.

Enhanced Page Navigation

- Rudyard Kipling - Facts

Rudyard Kipling

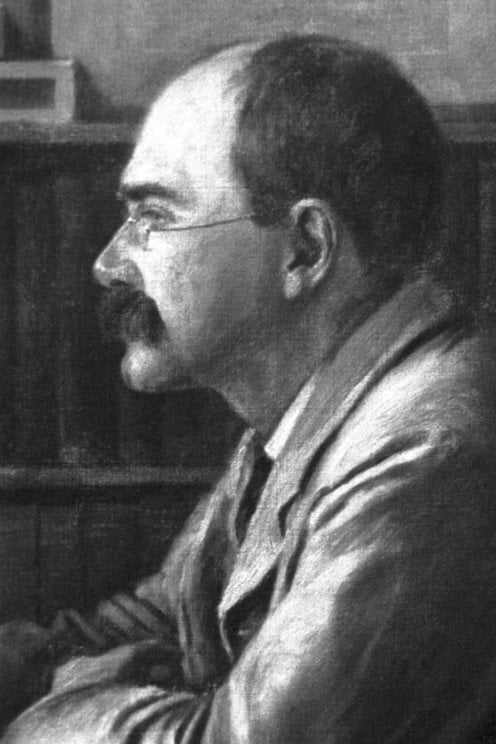

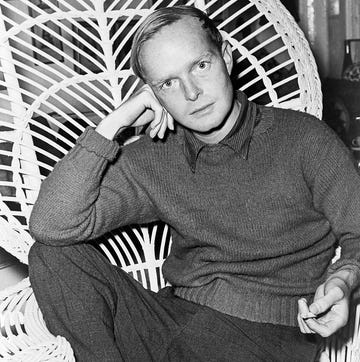

Photo from the Nobel Foundation archive.

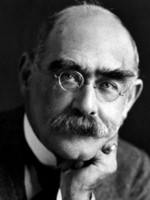

Rudyard Kipling The Nobel Prize in Literature 1907

Born: 30 December 1865, Bombay, British India (now Mumbai, India)

Died: 18 January 1936, London, United Kingdom

Residence at the time of the award: United Kingdom

Prize motivation: “in consideration of the power of observation, originality of imagination, virility of ideas and remarkable talent for narration which characterize the creations of this world-famous author”

Language: English

Prize share: 1/1

Rudyard Kipling was born in Mumbai and lived with relatives in England between the ages of 6 and 17, when he returned to India. As a child he spoke English, Hindi and Portuguese. This is evident in his writing, which revolves around issues of language and identity. After returning to India, Kipling traveled around the country as a correspondent. Contemporary Great Britain appreciated him for his depictions of life, religions, traditions and nature in what was then the British colony of India.

As a poet, short story writer, journalist and novelist, Rudyard Kipling described the British colonial empire in positive terms, which made his poetry popular in the British Army. The Jungle Book (1894) has made him known and loved by children throughout the world, especially thanks to Disney’s 1967 film adaptation. The Swedish Academy pointed out that Kipling’s special strengths were his personal portraits and descriptions of social settings that “penetrate to the essence of things” rather than just reproducing the transitory.

Nobel Prizes and laureates

Nobel prizes 2023.

Explore prizes and laureates

- Poem Guides

- Poem of the Day

- Collections

- Harriet Books

- Featured Blogger

- Articles Home

- All Articles

- Podcasts Home

- All Podcasts

- Glossary of Poetic Terms

- Poetry Out Loud

- Upcoming Events

- All Past Events

- Exhibitions

- Poetry Magazine Home

- Current Issue

- Poetry Magazine Archive

- Subscriptions

- About the Magazine

- How to Submit

- Advertise with Us

- About Us Home

- Foundation News

- Awards & Grants

- Media Partnerships

- Press Releases

- Newsletters

Rudyard Kipling

- Share on Twitter

- Share on Facebook

- Print this page

- Email this page

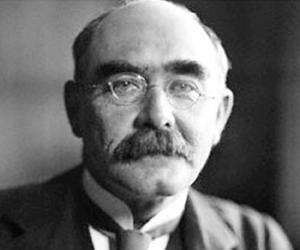

Rudyard Kipling is one of the best-known of the late Victorian poets and story-tellers. Although he was awarded the Nobel Prize for literature in 1907, his political views, which grew more toxic as he aged, have long made him critically unpopular. In the New Yorker, Charles McGrath remarked “Kipling has been variously labelled a colonialist, a jingoist, a racist, an anti-Semite, a misogynist, a right-wing imperialist warmonger; and—though some scholars have argued that his views were more complicated than he is given credit for—to some degree he really was all those things. That he was also a prodigiously gifted writer who created works of inarguable greatness hardly matters anymore, at least not in many classrooms, where Kipling remains politically toxic.” However, Kipling’s works for children, above all his novel The Jungle Book, first published in 1894, remain part of popular culture through the many movie versions made and remade since the 1960s.

Kipling was born in Bombay, India, in 1865. His father, John Lockwood Kipling, was principal of the Jeejeebyhoy School of Art, an architect and artist who had come to the colony, writes Charles Cantalupo in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, “to encourage, support, and restore native Indian art against the incursions of British business interests.” He meant to try, Cantalupo continues, “to preserve, at least in part, and to copy styles of art and architecture which, representing a rich and continuous tradition of thousands of years, were suddenly threatened with extinction.” His mother, Alice Macdonald, had connections through her sister’s marriage to the artist Sir Edward Burne-Jones with important members of the Pre-Raphaelite movement in British arts and letters. Kipling spent the first years of his life in India, remembering it in later years as almost a paradise. “My first impression,” he wrote in his posthumously published autobiography Something of Myself for My Friends Known and Unknown, “is of daybreak, light and colour and golden and purple fruits at the level of my shoulder.” In 1871, however, his parents sent him and his sister Beatrice—called “Trix”—to England, partly to avoid health problems, but also so that the children could begin their schooling. Kipling and his sister were placed with the widow of an old Navy captain named Holloway at a boarding house called Lorne Lodge in Southsea, a suburb of Portsmouth. Kipling and Trix spent the better part of the next six years in that place, which they came to call the “House of Desolation.” 1871 until 1877 were miserable years for Kipling. “In addition to feelings of bewilderment and abandonment” from being deserted by his parents, writes Mary A. O’Toole in the Dictionary of Literary Biography, “Kipling had to suffer bullying by the woman of the house and her son.” Kipling may have brought some of this treatment on himself—he was a formidably aggressive and pampered child. He once stamped down a quiet country road shouting: “Out of the way, out of the way, there’s an angry Ruddy coming!,” reports J.I.M. Stewart in his biography Rudyard Kipling, which led an aunt to reflect that “the wretched disturbances one ill-ordered child can make is a lesson for all time to me.” In Something of Myself, however, he recounted punishments that went far beyond correction. “I had never heard of Hell,” he wrote, “so I was introduced to it in all its terrors. … Myself I was regularly beaten.” On one occasion, after having thrown away a bad report card rather than bring it home, “I was well beaten and sent to school through the streets of Southsea with the placard ‘Liar’ between my shoulders.” At last, Kipling suffered a sort of nervous breakdown. An examination showed that he badly needed glasses—which helped explain his poor performance in school—and his mother returned from India to care for him. “She told me afterwards,” Kipling stated in Something of Myself, “that when she first came up to my room to kiss me good-night, I flung up an arm to guard off the cuff that I had been trained to expect.” Kipling did have some happy times during those years. He and his sister spent each December time with his mother’s sister, Lady Burne-Jones, at The Grange, a meeting-place frequented by English artisans such as William Morris—or “our Deputy ‘Uncle Topsy’” as Kipling called him in Something of Myself. Sir Edward Burne-Jones occasionally entered into the children’s play, Kipling recalled: “Once he descended in broad daylight with a tube of ‘Mummy Brown’ [paint] in his hand, saying that he had discovered it was made of dead Pharaohs and we must bury it accordingly. So we all went out and helped—according to the rites of Mizraim and Memphis, I hope—and—to this day I could drive a spade within a foot of where that tube lies.” “But on a certain day—one tried to fend off the thought of it—the delicious dream would end,” he concluded, “and one would return to the House of Desolation, and for the next two or three mornings there cry on waking up.” In 1878, Kipling was sent off to school in Devon, in the west of England. The institution was the United Services College, a relatively new school intended to educate the sons of army officers, and Kipling was probably sent there because the headmaster was one Cormell Price, “one of my Deputy-Uncles at The Grange … ‘Uncle Crom.’” There Kipling formed three close friends, whom he later immortalized in his collection of stories Stalky Co, published in 1899. “We fought among ourselves ‘regular an’ faithful as man an’ wife,’” Kipling reported in Something of Myself, “but any debt which we owed elsewhere was faithfully paid by all three of us.” “I must have been ‘nursed’ with care by Crom and under his orders,” Kipling recalled. “Hence, when he saw I was irretrievably committed to the ink-pot, his order that I should edit the School Paper and have the run of his Library Study. … Heaven forgive me! I thought these privileges were due to my transcendent personal merits.” Since his parents could not afford to send him to one of the major English universities, in 1882 Kipling left the Services College, bound for India to rejoin his family and to begin a career as a journalist. For five years he held the post of assistant editor of the Civil and Military Gazette at Lahore. During those years he also published the stories that became Plain Tales from the Hills, works based on British lives in the resort town of Simla, and Departmental Ditties, his first major collection of poems. In 1888, the young journalist moved south to join the Allahabad Pioneer, a much larger publication. At the same time, his works had begun to be published in cheap editions intended for sale in railroad terminals, and he began to earn a strong popular following with collections such as The Phantom ‘Rickshaw and Other Tales, The Story of the Gadsbys, Soldiers Three, Under the Deodars, and “Wee Willie Winkie” and Other Child Stories. In March 1889 Kipling left India to return to England, determined to pursue his future as a writer there. The young writer’s reputation soared after he settled in London. “Kipling’s official biographer, C.E. Carrington,” declares Cantalupo, “calls 1890 ‘Rudyard Kipling’s year. There had been nothing like his sudden rise to fame since Byron.’” “His poems and stories,” writes O’Toole, “elicited strong reactions of love and hate from the start—almost none of his advocates and detractors were temperate in praise or in blame. Ordinary readers liked the rhythms, the cockney speech, and the imperialist sentiments of his poems and short stories; critics generally damned the works for the same reasons.” Many of his works were originally published in periodicals and later collected in various editions as Barrack-Room Ballads; famous poems such as “The Ballad of East and West,”“ Danny Deever ,” “Tommy,” and “The Road to Mandalay” date from this time. Kipling’s literary life in London brought him to the attention of many people. One of them was a young American publisher named Wolcott Balestier, who became friends with Kipling and persuaded him to work on a collaborative novel. The result, writes O’Toole, entitled The Naulahka, “reads more like one of Kipling’s travel books than like a novel” and “seems rather hastily and opportunistically concocted.” It was not a success. Balestier himself did not live to see the book published—he died on December 6, 1891—but he influenced Kipling strongly in another way. Kipling married Balestier’s sister, Caroline, in January, 1892, and the couple settled near their family home in Brattleboro, Vermont. The Kiplings lived in America for several years, in a house they built for themselves and called “Naulahka.” Kipling developed a close friendship with Theodore Roosevelt, then Under Secretary of the Navy, and often discussed politics and culture with him. “I liked him from the first,” Kipling recalled in Something of Myself, “and largely believed in him. … My own idea of him was that he was a much bigger man than his people understood or, at that time, knew how to use, and that he and they might have been better off had he been born twenty years later.” Both of Kipling’s daughters were born in Vermont—Josephine late in 1892, and Elsie in 1894—as was one of the classic works of juvenile literature: The Jungle Books, which are ranked among Kipling’s best works. The adventures of Mowgli, the foundling child raised by wolves in the Seeonee Hills of India, are “the cornerstones of Kipling’s reputation as a children’s writer,” declared William Blackburn in Writers for Children , “and still among the most popular of all his works.” The Mowgli stories and other, unrelated works from the collection—such as “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi” and “The White Seal”—have often been filmed and adapted into other media. In Something of Myself, Kipling traced the origins of these stories to a book he had read when he was young “about a lion-hunter in South Africa who fell among lions who were all Freemasons, and with them entered into a confederacy against some wicked baboons.” Martin Seymour-Smith, writing in Rudyard Kipling: A Biography, identifies another of the major sources as “the Jataka tales of India. Some of these fables go back as early as the fourth century BC and incorporate material of even earlier eras. One version, Jatakamala, was composed in about 200 AD by the poet Aryasura. They are Buddhist birth-stories— Jatakamala means ‘Garland of Birth Stories’—which the 19th-century scholar Rhys Davids described as ‘the most important collection of ancient folk-lore extant.’ Each of the 550 stories tells of the Buddha in some previous incarnation, and each is a story of the past occasioned by some incident in the present. … Some of the beast fables resemble Aesop’s, but the Jataka tales are more deliberately brutal. They teach not merely that men should be more tender towards animals, but the equivalence of all life.” The Kiplings left Vermont in 1896 after a fierce quarrel with Beatty Balestier, Kipling’s surviving brother-in-law. The writer’s unwillingness to be interviewed made him unpopular with the American press, and he was savagely ridiculed when the facts of the case became public. Rather than remain in America, Kipling and his wife returned to England, settling for a time in Rottingdean, Sussex, near the home of Kipling’s parents. The writer soon published another novel, drawing on his knowledge of New England life: Captains Courageous, the story of Harvey Cheney, a spoiled young man who is washed overboard while on his way to Europe and is rescued by fishermen. Cheney spends the summer learning about human nature and self-discipline. “After the ship has docked in Gloucester and Harvey’s parents have come to take him home,” explains O’Toole, “his father, a self-made man, is pleased to see that his son has grown from a snobbish boy to a self-reliant young man who has learned how to make his own way through hard work and to judge people by their own merits rather than by their bank balances.” The Kiplings returned to America on several occasions, but this practice ended in 1899 when the whole family came down with pneumonia and Josephine, his eldest daughter, died from it. She had been, writes Seymour-Smith, “by all accounts … unusually lively, witty and enchanting,” and her loss was deeply felt. Kipling sought solace in his work. In 1901 he published what many critics believe is his finest novel: Kim, the story of an orphaned Irish boy who grows up in the streets of Lahore, is educated at the expense of his father’s old Army regiment, and enters into “the Great Game,” the “cold war” of espionage and counter-espionage on the borders of India between Great Britain and Russia in the late 19th century. In many ways, Kipling suggested in Something of Myself, the book was a collaboration between himself and his father: “He would take no sort of credit for any of his suggestions, memories or confirmations,” the writer recalled, but “there was a good deal of beauty in it, and not a little wisdom; the best in both sorts being owed to my Father.” “The glory of Kim, ” declares O’Toole, “lies not in its plot nor in its characters but in its evocation of the complex Indian scene. The great diversity of the land—its castes; its sects; its geographical, linguistic, and religious divisions; its numberless superstitions; its kaleidoscopic sights, sounds, colors, and smells—are brilliantly and lovingly evoked.” In 1902 the Kiplings settled in their permanent home, a 17th-century house called “Bateman’s” in East Sussex. “In the years following the move,” O’Toole explains, “Kipling for the most part turned away from the types of stories he had written early in his career and explored new subjects and techniques.” One example, completed before the Kiplings occupied Bateman’s, was the collection called the Just So Stories, perhaps Kipling’s best-remembered and best-loved work. The stories, written for his own children and intended to be read aloud, deal with the beginnings of things: “How the Camel Got His Hump,” “The Elephant’s Child,” “The Sing-Song of Old Man Kangaroo,” “The Cat That Walked by Himself,” and many others. In these works, Kipling painted rich, vivid word-pictures that honor and at the same time parody the language of traditional Eastern stories such as the Jataka tales and the Thousand and One Arabian Nights. “In no other collection of children’s stories,” writes Elisabeth R. Choi in her foreword to the 1978 Crown edition of the Just So Stories, “is there such fanciful and playful language.” The area around Bateman’s, rich in English history, inspired Kipling’s last works for children, Puck of Pook’s Hill and its sequel, Rewards and Fairies. The main sources of their inspiration, Kipling explained in Something of Myself, came from artifacts discovered in a well they were drilling on the property: “When we stopped at twenty-five feet, we had found a Jacobean tobacco-pipe, a worn Cromwellian latten spoon and, at the bottom of all, the bronze cheek of a Roman horse-bit.” At the bottom of a drained pond, they “dredged two intact Elizabethan ‘sealed quarts’ … all pearly with the patina of centuries. Its deepest mud yielded us a perfectly polished Neolithic axe-head with but one chip on its still venomous edge.” From these artifacts—and a suggestion made by a cousin, the ruins of an ancient forge, and the playing of his children—Kipling constructed a series of related stories of how Dan and Una come to meet Puck, the last remaining Old Thing in England, and from him learn the history of their land. Kipling wrote many other works during the periods that he produced his children’s classics. He was actively involved in the Boer War in South Africa as a war correspondent, and in 1917 he was assigned the post of “Honorary Literary Advisor” to the Imperial War Graves Commission—the same year that his son John, who had been missing in action for two years, was confirmed dead. In his last years, explains O’Toole, he became even more withdrawn and bitter, losing much of his audience because of his unpopular political views—such as compulsory military service—and a “cruelty and desire for vengeance [in his writings] that his detractors detested.” Modern critical opinions, O’Toole continues, “are contradictory because Kipling was a man of contradictions. He had enormous sympathy for the lower classes … yet distrusted all forms of democratic government.” He declined awards offered him by his own government, yet accepted others from foreign nations. He finally succumbed to a painful illness early in 1936.

Additional insight on Kipling’s life, career, and views can be gleaned from the three volumes of The Letters of Rudyard Kipling. The volumes contain selected surviving letters written by Kipling between 1872 and 1910; it is believed that both Kipling and his wife destroyed many of Kipling’s other letters. Kipling’s chief correspondent was Edmonia Hill, who was his counselor and confidante beginning during his days as a journalist in India. Reviewers note that all of the letters reflect Kipling’s distinctive literary style. Jonathan Keates in the Observer wrote, “this gathering of survivors shows that Kipling, with his gift for the resonant, throat-grabbing phrase and his obsessive interest in watching and listening, could never write a dud letter.” John Bayley points out in the Times Literary Supplement : “[Kipling] wrote his letters, as he did his stories and early sketches, in an amalgam of Wardour Street and schoolboyese, with biblical overtones, often transposed into a sort of Anglo-Indian syntax. … Kipling is inimitable: at his innocently aesthetic worst, he can be deeply embarrassing; and the letters, like the stories, contain both sorts.” Writing in the Observer, Amit Chaudhuri remarks that the third volume of letters reveals “the contractions of a unique writer; a loving father and husband who was also deeply interested in the asocial, predominantly male pursuit of Empire; a conservative who succumbed to the romance of the new technology [the automobile]; an apologist for England for whom England was, in a fundamental and positive way, a ‘foreign country.’”

The Bell Buoy

The benefactors, the children.

- See All Poems by Rudyard Kipling

The Victorian Era

Following the impulse of the brush, poetic presidents.

- See All Related Content

- Asia, South

- Poems by This Poet

Bibliography

The city of sleep, danny deever, a death-bed, epitaphs of the war, "for all we have and are", harp song of the dane women, the long trail, mesopotamia, a pict song, recessional, the secret of the machines, sestina of the tramp-royal, the song of the banjo, song of the galley-slaves, "the trade", the verdicts.

An introduction to a period of seismic social change and poetic expansion.

A conversation with Kimiko Hahn, winner of the 2023 Ruth Lilly Poetry Prize.

By Rudyard Kipling, read by James Barbour

Behind the mask of Rudyard Kipling’s confidence.

We’ve matched 12 commanders-in-chief with the poets that inspired them.

By Rudyard Kipling

- Schoolboy Lyrics, privately printed, 1881.

- (With sister, Beatrice Kipling) Echoes: By Two Writers, Civil and Military Gazette Press (Lahore), 1884.

- Departmental Ditties and Other Verses, Civil and Military Gazette Press, 1886, 2nd edition, enlarged, Thacker, Spink (Calcutta), 1886, 3rd edition, further enlarged, 1888, 4th edition, still further enlarged, W. Thacker (London), 1890, deluxe edition, 1898.

- Departmental Ditties, Barrack-Room Ballads and Other Verses (contains the fifty poems of the fourth edition of Departmental Ditties and Other Verses and seventeen new poems later published as Ballads and Barrack-Room Ballads ), United States Book Co., 1890, revised edition published as Departmental Ditties and Ballads and Barrack-Room Ballads, Doubleday McClure, 1899.

- Ballads and Barrack-Room Ballads, Macmillan, 1892, new edition, with additional poems, 1893, published as The Complete Barrack-Room Ballads of Rudyard Kipling, edited by Charles Carrington, Methuen, 1973, reprint published as Barrack Room Ballads and Other Verses, White Rose Press, 1987.

- The Rhyme of True Thomas, D. Appleton, 1894.

- The Seven Seas, D. Appleton, 1896, reprinted, Longwood Publishing Group, 1978.

- Recessional (Victorian ode in commemoration of Queen Victoria's Jubilee), M. F. Mansfield, 1897.

- Mandalay, drawings by Blanche McManus, M. F. Mansfield, 1898, reprinted, Doubleday, Page, 1921.

- The Betrothed, drawings by McManus, M. F. Mansfield and A. Wessells, 1899.

- Poems, Ballads, and Other Verses, illustrations by V. Searles, H. M. Caldwell, 1899.

- Belts, A. Grosset, 1899.

- Cruisers, Doubleday McClure, 1899.

- The Reformer, Doubleday, Page, 1901.

- The Lesson, Doubleday, Page, 1901.

- The Five Nations, Doubleday, Page, 1903.

- The Muse among the Motors, Doubleday, Page, 1904.

- The Sons of Martha, Doubleday, Page, 1907.

- The City of Brass, Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- Cuckoo Song, Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- A Patrol Song, Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- A Song of the English, illustrations by W. Heath Robinson, Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- If, Doubleday, Page, 1910, reprinted, Doubleday, 1959.

- The Declaration of London, Doubleday, Page, 1911.

- The Spies' March, Doubleday, Page, 1911.

- Three Poems (contains The River's Tale, The Roman Centurion Speaks, and The Pirates in England ), Doubleday, Page, 1911.

- Songs from Books, Doubleday, Page, 1912.

- An Unrecorded Trial, Doubleday, Page, 1913.

- For All We Have and Are, Methuen, 1914.

- The Children's Song, Macmillan, 1914.

- A Nativity, Doubleday, Page, 1917.

- A Pilgrim's Way, Doubleday, Page, 1918.

- The Supports, Doubleday, Page, 1919.

- The Years Between, Doubleday, Page, 1919.

- The Gods of the Copybook Headings, Doubleday, Page, 1919, reprinted, 1921.

- The Scholars, Doubleday, Page, 1919.

- Great-Heart, Doubleday, Page, 1919.

- Danny Deever, Doubleday, Page, 1921.

- The King's Pilgrimage, Doubleday, Page, 1922.

- Chartres Windows, Doubleday, Page, 1925.

- A Choice of Songs, Doubleday, Page, 1925.

- Sea and Sussex, with an introductory poem by the author and illustrations by Donald Maxwell, Doubleday, Page, 1926.

- A Rector's Memory, Doubleday, Page, 1926.

- Supplication of the Black Aberdeen, illustrations by G. L. Stampa, Doubleday, Doran, 1929.

- The Church That Was at Antioch, Doubleday, Doran, 1929.

- The Tender Achilles, Doubleday, Doran, 1929.

- Unprofessional, Doubleday, Page, 1930.

- The Day of the Dead, Doubleday, Doran, 1930.

- Neighbours, Doubleday, Doran, 1932.

- The Storm Cone, Doubleday, Doran, 1932.

- His Apologies, illustrations by Cecil Aldin, Doubleday, Doran, 1932.

- The Fox Meditates, Doubleday, Doran, 1933.

- To the Companions, Doubleday, Doran, 1933.

- Bonfires on the Ice, Doubleday, Doran, 1933.

- Our Lady of the Sackcloth, Doubleday, Doran, 1935.

- Hymn of the Breaking Strain, Doubleday, Doran, 1935.

- Doctors, The Waster, The Flight, Cain and Abel, [and] The Appeal, Doubleday, Doran, 1939.

- A Choice of Kipling's Verse, selected and introduced by T. S. Eliot, Faber, 1941, Scribner, 1943.

- B.E.L., Doubleday, Doran, 1944.

- Poems of Rudyard Kipling, Avenel, 1995.

SHORT STORIES

- In Black and White, A. H. Wheeler (Allahabad), 1888, 1st American edition, Lovell, 1890.

- Plain Tales from the Hills, Thacker, Spink, 1888 , 2nd edition, revised, 1889, 1st English edition, revised, Macmillan, 1890, 1st American edition, revised, Doubleday McClure, 1899, reprint edited by H. R. Woudhuysen, Penguin, 1987.

- The Phantom 'Rickshaw and Other Tales, A. H. Wheeler, 1888, revised edition, 1890, reprinted, Hurst, 1901.

- The Story of the Gadsbys: A Tale With No Plot, A. H. Wheeler, 1888, 1st American edition, Lovell, 1890.

- Soldiers Three: A Collection of Stories Setting Forth Certain Passages in the Lives and Adventures of Privates Terence Mulvaney, Stanley Ortheris, and John Learoyd, A. H. Wheeler, 1888, 1st American edition, revised, Lovell, 1890, reprinted, Belmont, 1962.

- Under the Deodars, A. H. Wheeler, 1888, 1st American edition, enlarged, Lovell, 1890.

- The Courting of Dinah Shadd and Other Stories, with a biographical and critical sketch by Andrew Lang, Harper, 1890, reprinted, Books for Libraries, 1971.

- His Private Honour, Macmillan, 1891.

- The Smith Administration, A. H. Wheeler, 1891.

- Mine Own People, introduction by Henry James, United States Book Co., 1891.

- Many Inventions, D. Appleton, 1893, reprinted, Macmillan, 1982.

- Mulvaney Stories, 1897, reprinted, Books for Libraries, 1971.

- The Day's Work, Doubleday McClure, 1898, reprinted, Books for Libraries, 1971, reprinted with introduction by Constantine Phipps, Penguin, 1988.

- The Drums of the Fore and Aft, illustrations by L. J. Bridgman, Brentano's, 1898.

- The Man Who Would Be King, Brentano's, 1898.

- Black Jack, F. T. Neely, 1899.

- Without Benefit of Clergy, Doubleday McClure, 1899.

- The Brushwood Boy, illustrations by Orson Lowell, Doubleday & McClure, 1899, reprinted, with illustrations by F. H. Townsend, Doubleday, Page, 1907.

- Railway Reform in Great Britain, Doubleday, Page, 1901.

- Traffics and Discoveries, Doubleday, Page, 1904, reprinted, Penguin, 1987.

- They, Scribner, 1904.

- Abaft the Funnel, Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- Actions and Reactions, Doubleday, Page, 1909.

- A Diversity of Creatures, Doubleday, Page, 1917, reprinted, Macmillan, 1966, reprinted, Penguin, 1994.

- "The Finest Story in the World" and Other Stories, Little Leather Library, 1918.

- Debits and Credits, Doubleday, Page, 1926, reprinted, Macmillan, 1965.

- Thy Servant a Dog, Told by Boots, illustrations by Marguerite Kirmse, Doubleday, Doran, 1930.

- Beauty Spots, Doubleday, Doran, 1931.

- Limits and Renewals, Doubleday, Doran, 1932.

- The Pleasure Cruise, Doubleday, Doran, 1933.

- Collected Dog Stories, illustrations by Kirmse, Doubleday, Doran, 1934.

- Ham and the Porcupine, Doubleday, Doran, 1935.

- Teem: A Treasure-Hunter, Doubleday, Doran, 1935.

- The Maltese Cat: A Polo Game of the 'Nineties, illustrations by Lionel Edwards, Doubleday, Doran, 1936.

- "Thy Servant a Dog" and Other Dog Stories, illustrations by G. L. Stampa, Macmillan, 1938, reprinted, 1982.

- Their Lawful Occasions, White Rose Press, 1987.

- John Brunner Presents Kipling's Science Fiction: Stories, T. Doherty Associates (New York, NY), 1992.

- John Brunner Presents Kipling's Fantasy: Stories, T. Doherty Associates (New York, NY), 1992.

- The Man Who Would Be King, and Other Stories, Dover, 1994.

- The Science Fiction Stories of Rudyard Kipling, Carol, 1994.

- Collected Stories, edited by John Brunner, Knopf, 1994.

- The Works of Rudyard Kipling, Longmeadow Press, 1995.

- The Haunting of Holmescraft , Books of Wonder (New York, NY), 1998.

- The Mark of the Beast, and Other Horror Tales , Dover Publications (Mineola, NY), 2000.

- The Metaphysical Kipling , Aeon (Mamaroneck, NY), 2000.

- L. L. Owens, Tales of Rudyard Kipling: Retold Timeless Classics , Perfection Learning (Logan, IA), 2000.

- Craig Raine, editor and author of introduction, Selected Stories of Rudyard Kipling , Modern Library (New York, NY), 2002.

- The Light That Failed, J. B. Lippincott, 1891, revised edition, Macmillan, 1891, reprinted, Penguin, 1988.

- (With Wolcott Balestier) The Naulahka: A Story of West and East, Macmillan, 1892, reprinted, Doubleday, Page, 1925.

- Kim, illustrations by father, J. Lockwood Kipling, Doubleday, Page, 1901, new edition, with illustrations by Stuart Tresilian, Macmillan, 1958, reprinted, with introduction by Alan Sandison, Oxford University Press, 1987.

CHILDREN'S BOOKS

- "Wee Willie Winkie" and Other Child Stories, A. H. Wheeler, 1888, 1st American edition, Lovell, 1890, reprinted, Penguin, 1988.

- The Jungle Book (short stories and poems; also see below), illustrations by John Lockwood Kipling, W. H. Drake, and P. Frenzeny, Macmillan, 1894, adapted and abridged by Anne L. Nelan, with illustrations by Earl Thollander, Fearon, 1967 , reprinted, with illustrations by John Lockwood Kipling and Drake, Macmillan, 1982, adapted by G. C. Barrett, with illustrations by Don Daily, Courage Books, 1994, reprinted, with illustrations by Fritz Eichenberg, Grosset Dunlap, 1995, reprinted, with illustrations by Kurt Wiese, Knopf, 1994.

- The Second Jungle Book (short stories and poems), illustrations by John Lockwood Kipling, Century Co., 1895, reprinted, Macmillan, 1982.

- "Captains Courageous": A Story of the Grand Banks, Century Co., 1897, abridged edition, illustrated by Rafaello Busoni, Hart Publishing, 1960, reprinted, with an afterword by C. A. Bodelsen, New American Library, 1981, reprinted, Oxford University Press, 1995.

- Stalky Co. (short stories), Doubleday McClure, 1899, reprinted, Bantam, 1985, new and abridged edition, Pendulum Press, 1977.

- Just So Stories for Little Children (short stories and poems), illustrations by the author, Doubleday, Page, 1902, reprinted, Silver Burdett, 1986, revised edition, edited by Lisa Lewis, Oxford University Press, 1995, reprinted, with illustrations by Barry Moser, Books of Wonder, 1996.

- Puck of Pook's Hill (short stories and poems), Doubleday, 1906, reprinted, New American Library, 1988.

- Rewards and Fairies (short stories and poems), illustrations by Frank Craig, Doubleday, Page, 1910, revised edition, with illustrations by Charles E. Brock, Macmillan, 1926, reprinted, Penguin, 1988.

- Toomai of the Elephants, Macmillan, 1937.

- The Miracle of Purun Bhagat, Creative Education, 1985.

- Gunga Din, Harcourt, 1987.

- Mowgli Stories from "The Jungle Book," illustrated by Thea Kliros, Dover, 1994.

- The Elephant's Child, illustrated by John A. Rowe, North-South Books, 1995.

- The Beginning of the Armadillos, illustrated by John A. Rowe, North-South Books, 1995.

- Thomas Pinney, editor and author of introduction, The Jungle Play , Allen Lane/Penguin Press (New York, NY), 2000.

- How the Camel Got His Hump , North-South Books (New York, NY), 2001.

- The Classic Tale of the Jungle Book: A Young Reader's Edition of the Classic Story , Courage Books (Philadelphia, PA), 2003.

TRAVEL WRITINGS

- Letters of Marque (also see below), A. H. Wheeler, 1891.

- American Notes, M. J. Ivers, 1891, reprinted, Ayer Co., 1974, revised edition published as American Notes: Rudyard Kipling's West, University of Oklahoma Press, 1981.

- From Sea to Sea and Other Sketches, two volumes, Doubleday & McClure, 1899, published as one volume, Doubleday, Page, 1909, reprinted, 1925.

- Letters to the Family: Notes on a Recent Trip to Canada, Macmillan of Canada, 1908.

- Letters of Travel, 1892-1913, Doubleday, Page, 1920.

- Land and Sea Tales for Scouts and Guides, Macmillan (London), 1923, published as Land and Sea Tales for Boys and Girls, Doubleday, Page, 1923.

- Souvenirs of France, Macmillan, 1933.

- Brazilian Sketches, Doubleday, Doran, 1940.

- Letters from Japan, edited with an introduction and notes by Donald Richie and Yoshimori Harashima, Kenkyusha, 1962.

NAVAL AND MILITARY WRITINGS

- A Fleet in Being: Notes of Two Trips With the Channel Squadron, Macmillan, 1899.

- The Army of a Dream, Doubleday, Page, 1904, reprinted, White Rose Press, 1987.

- The New Army, Doubleday, Page, 1914.

- The Fringes of the Fleet, Doubleday, Page, 1915.

- France at War: On the Frontier of Civilization, Doubleday, Page, 1915.

- Sea Warfare, Macmillan, 1916, Doubleday, Page, 1917.

- Tales of "The Trade," Doubleday, Page, 1916.

- The Eyes of Asia, Doubleday, Page, 1918.

- The Irish Guards, Doubleday, Page, 1918.

- The Graves of the Fallen, Imperial War Graves Commission, 1919.

- The Feet of the Young Men, photographs by Lewis R. Freeman, Doubleday, Page, 1920.

- The Irish Guards in the Great War: Edited and Compiled from Their Diaries and Papers, two volumes, Doubleday, Page, 1923, Volume I: The First Battalion, Volume II: The Second Battalion and Appendices.

- The City of Dreadful Night and Other Places (articles; also see below), A. H. Wheeler, 1891.

- Out of India: Things I Saw, and Failed to See, in Certain Days and Nights at Jeypore and Elsewhere (includes The City of Dreadful Night and Other Places and Letters of Marque ), Dillingham, 1895.

- (With Charles R. L. Fletcher) A History of England, Doubleday, Page, 1911, published as Kipling's Pocket History of England, with illustrations by Henry Ford, Greenwich, 1983.

- How Shakespeare Came to Write "The Tempest," introduction by Ashley H. Thorndike, Dramatic Museum of Columbia University, 1916.

- London Town: November 11, 1918-1923, Doubleday, Page, 1923.

- The Art of Fiction, J. A. Allen, 1926.

- A Book of Words: Selections from Speeches and Addresses Delivered between 1906 and 1927, Doubleday, Doran, 1928.

- Mary Kingsley, Doubleday, Doran, 1932.

- Proofs of Holy Writ, Doubleday, Doran, 1934.

- Something of Myself for My Friends Known and Unknown (autobiography), Doubleday, Doran, 1937, reprinted, Penguin Classics, 1989.

- Rudyard Kipling to Rider Haggard: The Record of a Friendship, edited by Morton Cohen, Hutchinson, 1965.

- The Portable Kipling, edited by Irving Howe, Viking, 1982.

- "O Beloved Kids": Rudyard Kipling's Letters to His Children, selected and edited by Elliot L. Gilbert, Harcourt, 1984.

- The Letters of Rudyard Kipling, Vols. 1-3, edited by Thomas Pinney, University of Iowa Press (Iowa City, IA), 1990.

- Writings of Literature by Rudyard Kipling, edited by Sandra Kemp and Lisa Lewis, Cambridge University Press, 1995.

- Writings on Writing, edited by Kemp and Lewis, Cambridge University Press, 1996.

Also author of The Harbor Watch (one-act play; unpublished), 1913, and The Return of Imray (play; unpublished), 1914. Many of Kipling's works first appeared in periodicals, including four Anglo-Indian newspapers, the Civil and Military Gazette, the Pioneer, Pioneer News, Week's News; the Scots Observer and its successor, the National Observer; London Morning Post, the London Times, the English Illustrated Magazine, Macmillan's Magazine, McClure's Magazine, Pearson's Magazine, Spectator, Atlantic, Ladies' Home Journal, and Harper's Weekly. The recently discovered short story "Scylla and Charybdis" was published in the Spring, 2004 issue of the Kipling Society Journal. His works are collected in more than one hundred omnibus volumes. Collections of his papers may be found in many libraries, including the Houghton Library at Harvard University, the New York Public Library, the Library of Congress, and the Pierpoint Morgan Library.

Further Readings

- Amis, Kingsley, Rudyard Kipling and His World, Thames Hudson, 1975, Scribner, 1975.

- Bauer, Helen Pike, Rudyard Kipling: A Study of the Short Fiction, Maxwell Macmillan, 1994.

- Benfey, Christopher, If: The Untold Story of Kipling’s American Years, Penguin Press, 2019.

- Bingham, Jane H., editor, Writers for Children: Critical Studies of Major Authors since the Seventeenth Century, Scribner, 1988, pp. 329-26.

- Birkenhead, Frederick, Lord, Rudyard Kipling, Random House, 1978.

- Bodelsen, C. A., Aspects of Kipling's Art, Barnes Noble, 1964.

- Carrington, Charles Edmund, The Life of Rudyard Kipling, Doubleday, 1955, published as Rudyard Kipling, Penguin, 1989.

- Chandler, Lloyd H., A Summary of the Work of Rudyard Kipling, Grolier Club, 1930.

- Coates, John, The Day's Work: Kipling and the Idea of Sacrifice, Fairleigh Dickinson University Press, 1997.

- Cornell, Louis L., Kipling in India, St. Martin's, 1966.

- Durand, Ralph, A Handbook to the Poetry of Rudyard Kipling, Hodder Stoughton, 1914.

- Dictionary of Literary Biography, Gale, Volume 19: British Poets, 1840-1914, 1983, pp. 247-73, Volume 34: British Novelists, 1890-1929: Traditionalists, 1985, pp. 208-20.

- Dobree, Bonamy, Rudyard Kipling: Realist and Fabulist, Oxford University Press, 1967.

- Fido, Martin, Rudyard Kipling, Viking, 1974.

- Gilbert, Elliot L., editor, Kipling and the Critics, New York University Press, 1965.

- Gilbert, Elliot L., editor, The Good Kipling: Studies in the Short Story, Ohio University Press, 1970.

- Greene, Carol, Rudyard Kipling: Author of The Jungle Books, Childrens Press, 1994.

- Gross, John, editor, The Age of Kipling, Simon Schuster, 1972.

- Gross, John, editor, Rudyard Kipling: The Man, His Work, and His World, Weidenfeld Nicolson, 1972.

- Harrison, James, Rudyard Kipling, Twayne, 1982.

- Henn, T. R., Kipling, Oliver Boyd, 1967.

- Hopkirk, Peter, Quest for Kim: In Search of Kipling's Great Game, Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Islam, Shamsul, Kipling's "Law": A Study of His Philosophy of Life, foreword by J. M. S. Tompkins, Macmillan (London), 1975.

- Kamen, Gloria, Kipling: Storyteller of East and West, Atheneum, 1985.

- Kipling, Rudyard, Just So Stories for Little Children foreword by Elisabeth R. Choi, Crown Publishers, 1978.

- Kipling, Rudyard, Something of Myself for My Friends Known and Unknown, Doubleday, Doran, 1937.

- Moss, Robert F., Rudyard Kipling and the Fiction of Adolescence, St. Martin's Press, 1982.

- Murray, Stuart, Rudyard Kipling in Vermont: Birthplace of the Jungle Books, Images of the Past (Bennington, VT), 1997.

- Orel, Harold, editor, Kipling: Interviews and Recollections, two volumes, Barnes Noble, 1983.

- Poetry Criticism, Volume 3, Gale, 1992.

- Rutherford, Andrew, editor, Kipling's Mind and Art: Selected Critical Essays, Stanford University Press, 1964.

- Seymour-Smith, Martin, Rudyard Kipling: A Biography, St. Martin's Press, 1989.

- Short Story Criticism, Volume 5, Gale, 1990.

- Stewart, James McGregor, Rudyard Kipling: A Bibliographical Catalogue, edited by A. W. Yeats, Dalhousie University Press and University of Toronto Press, 1959.

- Stewart, J. I. M., Rudyard Kipling, Dodd, 1966.

- Tompkins, Joyce Marjorie Sanxter, The Art of Rudyard Kipling, Methuen, 1959.

- Twentieth-Century Literary Criticism, Gale, Volume 8, 1982; Volume 17, 1985.

- Wilson, Angus, The Strange Ride of Rudyard Kipling: His Life and Works, Secker Warburg, 1977, Viking, 1978.

- Zaidan, Samira H., A Comparative Study of Haiu Bnu Yakdhan, Mowgli, and Tarzan, Red Squirrel Books, 1998.

PERIODICALS

- American Scholar, autumn, 1995, p. 599.

- Dalhousie Review, fall, 1960.

- Detroit Free Press, July 7, 1986.

- Horn Book, March-April, 1994, p. 199; January-February, 1996, p. 99.

- London Review of Books, March 21, 1991, p. 13.

- Los Angeles Times Book Review, August 5, 1984, March 31, 1991, p. 4.

- Modern Fiction Studies, summer, 1961, summer, 1984.

- Observer, December 2, 1990, March 17, 1996.

- Proceedings of the British Academy, Volume 51, 1965.

- School Library Journal, February, 1994, p. 102; May, 1995, p. 86; November, 1995, p. 112.

- Sewanee Review, winter, 1944.

- Times (London), December 6, 1984.

- Times Literary Supplement, January 15, 1960, September 2, 1960, December 21-27, 1990, p. 1367.

- Audio Poems

- Audio Poem of the Day

- Twitter Find us on Twitter

- Facebook Find us on Facebook

- Instagram Find us on Instagram

- Facebook Find us on Facebook Poetry Foundation Children

- Twitter Find us on Twitter Poetry Magazine

- Privacy Policy

- Terms of Use

- Poetry Mobile App

- 61 West Superior Street, Chicago, IL 60654

- © 2024 Poetry Foundation

- Games & Quizzes

- History & Society

- Science & Tech

- Biographies

- Animals & Nature

- Geography & Travel

- Arts & Culture

- On This Day

- One Good Fact

- New Articles

- Lifestyles & Social Issues

- Philosophy & Religion

- Politics, Law & Government

- World History

- Health & Medicine

- Browse Biographies

- Birds, Reptiles & Other Vertebrates

- Bugs, Mollusks & Other Invertebrates

- Environment

- Fossils & Geologic Time

- Entertainment & Pop Culture

- Sports & Recreation

- Visual Arts

- Demystified

- Image Galleries

- Infographics

- Top Questions

- Britannica Kids

- Saving Earth

- Space Next 50

- Student Center

Rudyard Kipling summary

Rudyard Kipling , (born Dec. 30, 1865, Bombay, India—died Jan. 18, 1936, London, Eng.), Indian-born British novelist, short-story writer, and poet. The son of a museum curator, he was reared in England but returned to India as a journalist. He soon became famous for volumes of stories, beginning with Plain Tales from the Hills (1888; including “The Man Who Would Be King”), and later for the poetry collection Barrack-Room Ballads (1892; including “Gunga Din” and “Mandalay”). His poems, often strongly rhythmic, are frequently narrative ballads. During a residence in the U.S., he published a novel, The Light That Failed (1890); the two Jungle Book s (1894, 1895), stories of the wild boy Mowgli in the Indian jungle that have become children’s classics; the adventure story Captains Courageous (1897); and Kim (1901), one of the great novels of India. He wrote six other volumes of short stories and several other verse collections. His children’s books include the famous Just So Stories (1902) and the fairy-tale collection Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906). He was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1907. His extraordinary popularity in his own time declined as his reputation suffered after World War I because of his widespread image as a jingoistic imperialist.

Rudyard Kipling: Biography

The story of Rudyard Kipling is a tale of paradise lost. It is the story of a literary genius who wrote some of the world's best known and enduring books yet whose own life was filled with tragedy.

Kipling was a literary giant of the twentieth century, a man whose remarkable range of work captivated not just a nation but an empire. He was the nations laureate, the voice of the people and he became an international superstar.

His work continues to fascinate and enchant. ‘The Jungle Book’ and the famous poem, ‘If’, remain as popular today as they were when published one hundred years ago.

Less well-known is the private life of the man who produced such masterpieces. Kipling endured an appalling childhood, a domineering wife, and the devastating loss of two of his children.

Most Recent

11 facts about legendary viking warrior Ragnar Lothbrok

9 most dangerous British crime gangs

'We will always represent the entire LGBTQ+ community': Interview with Gaydio's Kriss Herbert-Noble

The 1854 Broad Street cholera outbreak

More from history.

8 celebrities related to historical figures

Eurovision Song Contest: 'It's the history of Europe through television'

The most dramatic television interviews of all time

When is World Book Day 2024?

Keep reading.

Roald Dahl's secret life as a WW2 spy

Storage Wars: Barry's Best Buys

Storage Wars: Miami Series 1

Storage Wars: Texas Series 6

You might be interested in.

Did Shakespeare Really Die From a Hangover?

Great minds who triumphed in lockdown

How the Stonewall riots changed the world

Unidentified: Tom DeLonge and Luis Elizondo interview

In order to continue enjoying our site, we ask that you confirm your identity as a human. Thank you very much for your cooperation.

Rudyard Kipling Biography: Life, Achievements, and Legacy

{ Read his poems }

Rudyard Kipling, born on December 30, 1865, in Bombay, India, was an English author, poet, and journalist whose extensive body of work has made him one of the most influential literary figures of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His vivid storytelling and unforgettable characters brought to life the culture and spirit of the British Empire and the Indian subcontinent, earning him a dedicated and widespread readership.

Kipling’s work spans various literary genres, including short stories, novels, and poetry, which have been celebrated for their exceptional narrative quality, captivating characters, and profound exploration of human nature. With classics like The Jungle Book, Kim, and the Just So Stories, Kipling introduced readers to rich, fantastical worlds while also addressing the complex social and political issues of his time.

His writings continue to inspire and provoke discussions on subjects such as colonialism, race, and the human experience, while also influencing countless authors and artists that followed him. As a testament to his literary prowess, Kipling was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1907, further solidifying his position as a towering figure in the realm of English literature.

Table of Contents

Early Life and Influences

Birth and family background.

Rudyard Kipling was born on December 30, 1865, in Bombay (now Mumbai), India, to John Lockwood Kipling and Alice Macdonald Kipling. His father, an artist and educator, was the principal and professor of architectural sculpture at the Jeejeebhoy School of Art in Bombay. His mother, Alice, was a vivacious woman with a strong social circle, which included many influential figures of the time. Rudyard was named after the picturesque Rudyard Lake in Staffordshire, England, where his parents had met and courted.

Education and formative experiences

United services college.

At the age of six, Kipling was sent to England to receive a British education, as was customary for children of British colonial officials. He attended the United Services College in Westward Ho!, Devon, a boarding school that primarily prepared boys for military service. It was here that Kipling experienced the harsh realities of British boarding school life, which he later chronicled in his semi-autobiographical novel, Stalky & Co. (1899). Kipling’s time at the United Services College helped shape his outlook on life and instilled in him a deep appreciation for discipline, order, and loyalty.

Influence of India on his work

Kipling’s childhood years in India had a lasting impact on his writing, as he was captivated by the country’s vibrant culture, folklore, and diverse landscape. The sights, sounds, and experiences of his early years in Bombay permeated his work, providing rich and authentic details that set his stories apart. Kipling’s deep connection to India would later serve as the backdrop for some of his most acclaimed works, including The Jungle Book, Kim, and many of his short stories.

Apprenticeship as a journalist

Work at the civil and military gazette.

At the age of 16, Kipling returned to India to work as a journalist at the Civil and Military Gazette, an English-language newspaper in Lahore (now in Pakistan). During his time there, he honed his writing skills and developed a keen eye for observing and capturing the subtleties of human nature. He also began publishing his poetry and short stories in the newspaper, marking the beginning of his literary career.

Work at The Pioneer

In 1887, Kipling moved to Allahabad to work for The Pioneer, another prominent English-language newspaper in India. This new position allowed him to further develop his journalistic and literary skills, while also offering him the opportunity to travel extensively throughout the Indian subcontinent. These experiences further enriched his writing, as he gained invaluable insights into the lives, customs, and struggles of the diverse people who inhabited the region.

Literary Career

Early writings and poetry, departmental ditties (1886).

Kipling’s first collection of verse, Departmental Ditties, was published in 1886. It contained satirical poems that humorously depicted the bureaucracy and daily life of British colonial administration in India. The poems showcased Kipling’s wit and keen observational skills, highlighting the foibles and eccentricities of the characters he encountered during his journalistic career.

Plain Tales from the Hills (1888)

In 1888, Kipling published his first collection of short stories, Plain Tales from the Hills. The stories, initially published in the Civil and Military Gazette, offered a unique glimpse into the lives of British colonial officers, their families, and the local Indian population. Kipling’s vivid descriptions and engaging storytelling made the collection an instant success, both in India and England.

The Barrack-Room Ballads (1892)

In 1892, Kipling released The Barrack-Room Ballads, a collection of poems that captured the experiences of British soldiers in India. Among the most famous of these poems is “Gunga Din,” which tells the story of an Indian water-bearer who bravely saves a British soldier’s life despite facing discrimination and ill-treatment.

Danny Deever

Another notable poem from The Barrack-Room Ballads is “Danny Deever,” which recounts the execution of a British soldier for murdering a fellow comrade. The poem’s somber tone and vivid imagery struck a chord with readers and further demonstrated Kipling’s versatility as a writer.

The Jungle Book (1894) and The Second Jungle Book (1895)

Mowgli’s story.

Kipling’s most famous work, The Jungle Book, was published in 1894, followed by The Second Jungle Book in 1895. The books consist of a series of short stories, with the most well-known centering on Mowgli, a young boy raised by wolves in the Indian jungle. Mowgli’s adventures and encounters with various animals, including the wise panther Bagheera and the villainous tiger Shere Khan, have captivated readers for generations.

Rikki-Tikki-Tavi

Another beloved story from The Jungle Book is “Rikki-Tikki-Tavi,” which tells the tale of a courageous mongoose who protects a human family from two deadly cobras. The story is a testament to Kipling’s ability to create memorable characters and weave engaging tales that transcend time and culture.

Captains Courageous (1897)

Captains Courageous, published in 1897, is a coming-of-age novel that follows the journey of Harvey Cheyne, a spoiled American boy who is transformed through his experiences working on a fishing schooner. The novel showcases Kipling’s talent for capturing the human spirit and the challenges faced by individuals in unique circumstances.

Kim, published in 1901, is Kipling’s most acclaimed novel. Set in colonial India, it tells the story of Kimball O’Hara, a young orphan who becomes embroiled in the “Great Game” of espionage and political intrigue between the British and Russian Empires. The novel is a rich exploration of the complexities of identity, loyalty, and friendship, as well as a vivid portrayal of the Indian subcontinent’s diverse culture and landscape.

Just So Stories (1902)

In 1902, Kipling published the Just So Stories, a collection of imaginative and humorous tales for children that explain how various animals acquired their unique features, such as “How the Leopard Got His Spots” and “The Elephant’s Child.”

Puck of Pook’s Hill (1906) and Rewards and Fairies (1910)

Puck of Pook’s Hill, published in 1906, is a collection of short stories and poems centered around the adventures of two English children, Dan and Una, who encounter Puck, a mischievous and wise fairy from ancient English folklore. This collection of short stories introduces the children to a series of historical figures, transporting them through various eras of English history. The stories are woven together with Kipling’s deep love for his country and its rich heritage. Rewards and Fairies, the sequel published in 1910, continues the adventures of Dan and Una with Puck as their guide, providing further insights into England’s history and mythology.

Later writings and poetry

A diversity of creatures (1917).

A Diversity of Creatures, published in 1917, is a collection of short stories and poems that reflect Kipling’s diverse literary interests and talents. The collection includes tales that delve into the human condition, explore the natural world, and touch upon the social and political issues of the time. Some of the notable stories in this collection include “Mary Postgate,” a chilling tale of revenge, and “The Eye of Allah,” which explores the consequences of the discovery of a powerful scientific invention.

Debits and Credits (1926)

Debits and Credits, published in 1926, is another collection of short stories and poems that showcase Kipling’s versatility as a writer. This collection touches on a wide range of themes, from the complexities of human relationships to the moral dilemmas faced by individuals in wartime. The poignant tale “The Gardener,” for instance, tells the story of a woman’s quest to find her nephew’s grave after World War I. These later works by Kipling further demonstrate his ability to captivate readers with his storytelling and to delve deeply into the human experience.

Personal Life

Marriage to caroline balestier.

In 1892, Kipling married Caroline “Carrie” Balestier, the sister of his American publisher and collaborator Wolcott Balestier. Their union was marked by a deep mutual affection and understanding, with Carrie providing the emotional and practical support that Kipling needed to navigate the demands of his literary career. Together, they had three children: Josephine, Elsie, and John.

Life in the United States

Naulakha, their vermont home.

Shortly after their marriage, Kipling and Carrie moved to the United States, where they built a home called “Naulakha” in Dummerston, Vermont. This period in Kipling’s life was marked by both personal happiness and professional success, as he penned some of his most enduring works, including The Jungle Book and Captains Courageous, while enjoying the serenity and beauty of the Vermont countryside.

Relationship with American culture and people

Kipling’s time in the United States allowed him to develop an appreciation for American culture and its people, whom he found to be warm, friendly, and open-hearted. His experiences in America influenced his writing, as he incorporated American themes and characters into his works, such as the protagonist of Captains Courageous. However, Kipling’s relationship with America was not without its challenges, as he faced criticism for his views on imperialism and international politics.

Return to England

Bateman’s, their sussex home.

In 1896, after a legal dispute with Carrie’s brother, the Kiplings decided to return to England. They settled in a 17th-century house called Bateman’s in Burwash, East Sussex, where Kipling found solace and inspiration in the English countryside. Bateman’s would remain their home for the rest of Kipling’s life, serving as a sanctuary where he could write and reflect on the world around him.

Kipling’s later years and friendships

Kipling’s later years were marked by both personal tragedy and professional triumph. He faced the heartbreaking loss of his daughter Josephine to pneumonia in 1899 and his son John in World War I in 1915. Despite these challenges, Kipling continued to write and maintain friendships with notable figures of his time, including fellow authors H.G. Wells and Henry James. As Kipling aged, his literary output slowed, but he remained a respected and influential figure in the world of English literature until his death in 1936.

Literary Achievements and Honors

Nobel prize in literature (1907).

In 1907, Rudyard Kipling was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, making him the first English-language writer to receive this prestigious honor. The Swedish Academy lauded Kipling for his extraordinary narrative gifts and his ability to capture the essence of the human experience in a powerful and vivid manner. The Nobel Prize not only recognized Kipling’s exceptional body of work but also cemented his place as one of the most important literary figures of his time.

Influence on contemporary writers

Kipling’s innovative storytelling, unique characters, and masterful use of language have left an indelible mark on the world of literature. He has influenced countless authors, including Ernest Hemingway, George Orwell, and J.R.R. Tolkien, who have drawn inspiration from his vivid descriptions, moral themes, and compelling narratives. Kipling’s work has also been adapted for film, television, and stage, further attesting to the enduring appeal and relevance of his stories.

Criticisms and controversies

Accusations of racism and imperialism.

Despite his significant literary achievements, Kipling’s work has not been without controversy. Critics have accused him of promoting racism and imperialism, particularly in his portrayal of non-European cultures and his endorsement of British colonial rule. Kipling’s famous poem “The White Man’s Burden” has been widely criticized for its paternalistic and condescending tone towards colonized peoples.

Kipling’s response to critics

Kipling was not oblivious to the criticisms of his work and the controversy surrounding his views on race and imperialism. In some instances, he defended his position, arguing that he genuinely believed in the civilizing mission of the British Empire. In other cases, Kipling acknowledged the complexities and contradictions inherent in colonial rule, as evidenced by the nuanced portrayal of characters and situations in works like Kim. While Kipling’s views on race and imperialism remain a subject of debate, his literary contributions and their impact on generations of readers and writers cannot be denied.

Enduring Legacy

Adaptations of kipling’s work, film and television adaptations.

The enduring appeal of Rudyard Kipling’s stories is evident in the numerous film and television adaptations of his work. Among the most famous adaptations are the multiple versions of The Jungle Book, which have captivated audiences worldwide with their engaging characters and memorable songs. Additionally, other works like Kim, Captains Courageous, and Rikki-Tikki-Tavi have been brought to life on screen, introducing Kipling’s stories to new generations of viewers and solidifying his status as a beloved storyteller.

Influence on popular culture

Kipling’s work has also made a significant impact on popular culture, with phrases from his poems and stories becoming part of the common lexicon. For example, the expression “the law of the jungle” is derived from The Jungle Book, while “East is East, and West is West” comes from his poem “The Ballad of East and West.” Kipling’s characters, stories, and themes continue to resonate with contemporary audiences, demonstrating his enduring influence on our collective imagination.

Continued impact on literature

Themes and motifs in kipling’s work.

Kipling’s work is characterized by its exploration of themes such as the complexities of human nature, the struggle for survival, and the moral dilemmas faced by individuals in challenging situations. His stories often feature characters who must navigate the tensions between tradition and modernity, loyalty and betrayal, and duty and desire. These timeless themes continue to inspire and engage readers, while also providing a rich source of study for scholars and critics.

Kipling’s place in the literary canon

Despite the controversies surrounding some aspects of his work, Rudyard Kipling’s place in the literary canon remains secure. His unique storytelling style, evocative descriptions, and memorable characters have made him a towering figure in the world of English literature. Kipling’s work has been analyzed, interpreted, and celebrated for generations, and his influence on subsequent writers is undeniable. As a result, his stories and poems continue to be read, studied, and cherished, ensuring that his literary legacy will endure for years to come.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

- POET'S PAGE

Rudyard Kipling

Biography of rudyard kipling.

Rudyard Kipling was an English writer and winner of the Nobel Prize for Literature. He is best known for his poems and stories set in India during the period of British imperial rule.

Rudyard Kipling was born in Bombay, India, on 30 December 1865. His father was an artist and teacher. In 1870, Kipling was taken back to England to stay with a foster family in Southsea and then to go to boarding school in Devon. In 1882, he returned to India and worked as a journalist, writing poetry and fiction in his spare time. Books such as 'Plain Tales from the Hills' (1888) gained success in England, and in 1889 Kipling went to live in London.

In 1892, Rudyard Kipling married Caroline Balestier, the sister of an American friend, and the couple moved to Vermont in the United States, where her family lived. Their two daughters were born there and Kipling wrote 'The Jungle Book' (1894). In 1896, a quarrel with his wife's family prompted Kipling to move back to England and he settled with his own family in Sussex. His son John was born in 1897.

By now Rudyard Kipling had become an immensely popular writer and poet for children and adults. His books included 'Stalky and Co.' (1899), 'Kim' (1901) and 'Puck of Pook's Hill' (1906). The 'Just So Stories' (1902) were originally written for his daughter Josephine, who died of pneumonia aged six.

Rudyard Kipling turned down many honours in his lifetime, including a knighthood and the poet laureateship, but in 1907, he accepted the Nobel Prize for Literature, the first English author to be so honoured.

In 1902, Rudyard Kipling bought a 17th century house called Bateman's in East Sussex where he lived for the rest of his life. He also travelled extensively, including repeated trips to South Africa in the winter months.

In 1915, his son, John, went missing in action while serving with the Irish Guards in the Battle of Loos during World War One. Rudyard Kipling had great difficulty accepting his son's death - having played a major role in getting the chronically short-sighted John accepted for military service - and subsequently wrote an account of his regiment, 'The Irish Guards in the Great War'. He also joined the Imperial War Graves Commission and selected the biblical phrase inscribed on many British war memorials: 'Their Name Liveth For Evermore'.

Rudyard Kipling died on 18 January 1936 and is buried at Westminster Abbey.

See more of Poemist by logging in

Login required!

- Tools and Resources

- Customer Services

- Agriculture

- Armed forces and intelligence services

- Art and architecture

- Business and finance

- Education and scholarship

- Individuals

- Law and crime

- Manufacture and trade

- Media and performing arts

- Medicine and health

- Religion and belief

- Royalty, rulers, and aristocracy

- Science and technology

- Social welfare and reform

- Sports, games, and pastimes

- Travel and exploration

- Writing and publishing

- Christianity

- Download chapter (pdf)

- Share This Facebook LinkedIn Twitter

Article contents

Kipling, (joseph) rudyard.

- Thomas Pinney

- https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/34334

- Published in print: 23 September 2004

- Published online: 23 September 2004

- This version: 07 January 2016

- Previous version

(Joseph) Rudyard Kipling ( 1865–1936 )

by Sir Philip Burne-Jones , 1899

Kipling, (Joseph) Rudyard ( 1865–1936 ), writer and poet , was born in Bombay, India, on 30 December 1865, the son of John Lockwood Kipling (1837–1911) , professor of architectural sculpture in the Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy School of Art in Bombay, and his wife, Alice Kipling [ see under Macdonald sisters ]. The name Joseph (never used) was family tradition, elder sons being named Joseph or John in alternation; ‘Rudyard’ came from Lake Rudyard in Staffordshire, where his parents had first met. Both his father and his mother were the children of Methodist ministers, and both quietly rebelled against their evangelical origins. Kipling was brought up in indifference to organized religion; although he always believed in the reality of the spiritual, he never held any religious doctrine. His childish impressions of Muslim, Hindu, and Parsi—he recalled ' little Hindu temples ' with ' dimly-seen, friendly Gods ' ( Kipling , Something of Myself , chap. 1 )—made him more sympathetic to those forms than to the charmless protestantism he afterwards encountered in England.

Early years and education

In 1871 the Kipling family, now including his younger sister Alice (always called Trix ), Rudyard's only sibling, returned to England on leave. On their return to India the parents left their children with people in Southsea, now part of Portsmouth, who had advertised their services in caring for the children of English parents in India. It was a usual practice for the children of the English in India to be thus separated from their parents, but Rudyard and his sister were not prepared for the event. ' We had had no preparation or explanation ', Kipling's sister wrote; ' it was like a double death, or rather, like an avalanche that had swept away everything happy and familiar ' ( Fleming , 171 ). Nor is it known why the parents chose to put them in the hands of paid guardians rather than with one or more members of Alice Kipling's family. One sister was married to Alfred Baldwin , a prosperous manufacturer: their child, about the same age as Rudyard , was Stanley Baldwin , afterwards prime minister; another sister had married Sir Edward Burne-Jones , the painter; a third sister had married Sir Edward Poynter , who became president of the Royal Academy. By 1871 all of these families would have been able and willing to receive the Kipling children.

Instead they went to Southsea, to a house now notorious as the House of Desolation (so-called in Kipling's 'Baa baa, black sheep' ). Kipling was not yet six years old; Trix was three. Here he attended ' a terrible little day-school ' ( Kipling , Something of Myself , chap. 1 ). The woman who cared for them, Mrs Pryse Agar Holloway , is, in Kipling's account of her as Aunty Rosa, a monster. Deliberately cruel and unjust, she tries to set sister against brother, systematically humiliates the young Kipling , allows her son to terrorize him mentally and physically, and denies him simple pleasures. She also introduces a Calvinistic protestantism into Kipling's experience: ' I had never heard of Hell, so I was introduced to it in all its terrors '. He took refuge in reading. One of his punishments was to be compelled to read devotional literature: in this way he acquired a mastery of biblical phrase and image. The Kipling children remained with Mrs Holloway for five and a half years: towards the end of that time, Kipling's eyesight began to fail, and to his other miseries were added ' the nameless terrors of broad daylight that were only coats on pegs after all '. Kipling's mother returned from India in April 1877, and for the rest of the year her children lived with her. At the beginning of the next year Kipling went off to public school; Trix returned to the care of Mrs Holloway .

The truth of Kipling's description of his childhood has been doubted: Mrs Holloway was not cruel but misunderstood by a spoiled, preternaturally imaginative child; 'Baa baa, black sheep' is fiction, not autobiography; or, if autobiography, then shamelessly self-indulgent. And how can one explain Trix's return to Southsea? We cannot now know the facts. The effects of Kipling's abandonment in the House of Desolation upon his psyche, and, in turn, upon his works, continues to be at the centre of biographical and interpretive arguments. Kipling's own judgement was that his sufferings ' drained me of any capacity for real, personal hate for the rest of my days ', a conclusion not generally agreed with. He also thought that the experience contributed to the growth of the artist: ' it demanded constant wariness, the habit of observation, and attendance on moods and tempers ' ( Kipling , Something of Myself , chap. 1 ). If he blamed his parents, that did not appear in his behaviour towards them; he was not merely dutiful and loving but seems genuinely to have admired them both.

Kipling believed that what ' saved ' him during his Southsea ordeal was an annual visit to his aunt, Georgiana Burne-Jones , at The Grange, in Fulham, London, where he ' possessed a paradise ' of ' love and affection ' ( Kipling , Something of Myself , chap. 1 ). He was also much interested at The Grange in the example of his uncle at work and by Burne-Jones's conversations with such friends as William Morris , interests that Kipling's own artist father must have helped to encourage. We know little about Kipling's imaginative development until rather late in his school-days, but the impact of Burne-Jones and of the group to which he belonged, devoted to the highest standards of craftsmanship and to an unembarrassed worship of beauty, must be allowed to have had an important part in forming Kipling .

At the beginning of 1878 Kipling was sent to the United Services College at Westward Ho!, Bideford, north Devon, founded in 1874 by army officers in order to provide an affordable public school for their sons. Most of the students had the army as their goal. The headmaster, Cormell Price , an Oxford graduate, was a friend from early days of both Burne-Jones and of Kipling's mother. The new, raw, impoverished school was an unlikely place, but, after a long period of unhappiness following his entry, Kipling thrived there. For this happy result he always credited Price , whose virtues he magnified in the figure of the Head in Stalky & Co. ; more practically, he remained devoted to Price to the end of his days, helping him financially in his retirement and, after Price's death, acting as a trustee for Price's son. It is now impossible to see Kipling's school-days uncoloured by Stalky & Co. (1899), Kipling's fictional version of his life at Westward Ho! The bare facts that we have are often mildly at variance with Stalky , but the energy of the Stalky version overwhelms all attempts to correct the record. One may safely say that Kipling did make friends with Lionel Dunsterville (Stalky), with G. C. Beresford (M'Turk), was himself a recognizable original for Beetle, and was impressed more than he knew by the example of William Carr Crofts (King) and his passion for Latin literature. He admired Price , was given the run of Price's library, and edited the school paper, revived by Price for the express purpose of allowing Kipling to edit it. He also began to experiment in poetry, the form of literature he loved first and best. The extent and variety of Kipling's precocious exercises in poetry have been made clear in Andrew Rutherford's edition, Early Verse by Rudyard Kipling (1986), which includes fluent imitations of popular ballads, Pope , Keats , Browning , and Swinburne , among many others. In 1881 his parents privately printed a selection of this work under the title Schoolboy Lyrics . Though it was produced without Kipling's knowledge, and though he was embarrassed by it then and afterwards, the book is technically Kipling's first and is now one of the rarissima in his bibliography.

Despite the army flavour of the United Services College, Kipling's interests at the time seem to have been almost wholly literary. His school-days ended in May 1882; an indifferent school record and his parents' lack of means put Oxford and Cambridge out of the question. For a brief time Kipling flirted with the idea of medicine (an admiration for doctors and an interest in the art of healing always remained with him). Kipling's parents were both occasional contributors to the Civil and Military Gazette (CMG) , published in Lahore, where, in 1875, John Lockwood Kipling had been appointed head of both the newly founded Mayo School of Art and of the Lahore Museum. Through his parents' influence with the proprietors of the paper Kipling was offered a position as sub-editor and went to India in September 1882, arriving in Lahore towards the end of October. For the next six years and four months Kipling was to work uninterruptedly on newspapers in India.

Journalist in India

Though he was at first kept to routine editorial work, gradually Kipling began to write more, and more variously, for the paper—verse, an irregular column of local gossip, summaries of official reports, news paragraphs, and the like. In March 1884 he was sent to Patiala to report a state visit of the viceroy, and his success in this trial was such that from that point on the flow of his writing in the CMG is unchecked. The overflow found other outlets. In 1884 he and his sister published a collection of verses titled Echoes , exhibiting English life in India in the form of parodies of standard poets: Kipling's knowledge of American literature appears in his parodies of Emerson , Longfellow , and Joaquin Miller . For Christmas 1885 all four Kiplings published an annual called Quartette , containing such distinguished early work as 'The Strange Ride of Morrowbie Jukes' and 'The Phantom 'Rickshaw' . These exhibit the remarkably precocious maturity— Kipling was not yet twenty when they were written—that prompted Henry James to write of Kipling as a youth who ' has stolen the formidable mask of maturity and rushes about making people jump with the deep sounds, the sportive exaggerations of tone, that issue from its painted lips ' ( James ).

In 1886 Kipling published Departmental Ditties , lightly satirical verses about official life in India reprinted from the CMG . This, which Kipling always regarded as his first book, had a great success among the community it satirized. It also drew a brief, friendly notice from Andrew Lang in London, Kipling's first recognition in England.

As a journalist, Kipling was neither a civil servant nor a military officer, but could move freely among the different levels of Lahore society. The capital of the Punjab, Lahore abounded in high officials. It was also an army post, and Kipling discovered a new pleasure in observing and making friends with the officers and men of the British troops stationed at Fort Lahore and at Mian Mir , the nearby barracks. He wandered through the streets of Lahore at night, and though he claimed afterwards to have seen perhaps more of native life than in fact he did, he certainly paid that life more sympathetic attention than usually allowed to the English in India. In 1886, while still under age, he joined the masonic lodge Hope and Perseverance of Lahore, and was active in its affairs while he remained in Lahore. The prominence of masonic lore and masonic symbolism in Kipling's work from this time on is a recognized critical topic, as is the attraction to fraternal or exclusive organizations (for example Stalky & Co., Soldiers Three, the Seonee Pack, the Janeites) witnessed by his membership in the freemasons.