Research: Overview & Approaches

- Getting Started with Undergraduate Research

- Planning & Getting Started

- Building Your Knowledge Base

- Locating Sources

- Reading Scholarly Articles

- Creating a Literature Review

- Productivity & Organizing Research

- Scholarly and Professional Relationships

- Empirical Research

- Interpretive Research

- Action-Based Research

Introduction to Creative Research

Databases for finding creative research, journals for finding creative research, guided search, examples of creative research, sources and further reading, your librarian.

- Introductory Video This video covers what creative research is, what kinds of questions and methods creative researchers use, and some tips for finding creative research articles in your discipline.

- International Journal of Performance Arts and Digital Media

- International Journal of Education and the Arts

- Journal for Artistic Research

- Guided Search: Finding Creative Research Articles This is a hands-on tutorial that will allow you to use your own search terms to find resources.

- Finding Your Way Through the Woods - Experience of Artistic Research

- One Motorbike, One Arm, Two Cameras.

- Collaborative Creativity in STEAM: Narratives of Art Education Students' Experiences in Transdisciplinary Spaces

- Mobile Social Choreographies: Choreographic Insight as a Basis for Artistic Research into Mobile Technologies

- Performing Citizen Arrest: Surveillance Art and the Passerby

- How Art and Research Inform One Another, or Choose Your Own Adventure

- Hannula, M., Suoranta, J., & Vadén, T. (2014). Artistic research methodology: narrative, power and the public. Critical Qualitative Research, 15.

- << Previous: Action-Based Research

- Last Updated: May 29, 2024 3:30 PM

- URL: https://guides.lib.purdue.edu/research_approaches

What is Creative Research?

What is "creative" or "artistic" research how is it defined and evaluated how is it different from other kinds of research who participates and in what ways - and how are its impacts understood across various fields of inquiry.

After more than two decades of investigation, there is no singular definition of “creative research,” no prescribed or prevailing methodology for yielding practice-based research outcomes, and no universally applied or accepted methodology for assessing such outcomes. Nor do we think there should be.

We can all agree that any type of serious, thoughtful creative production is vital. But institutions need rubrics against which to assess outcomes. So, with the help of the Faculty Research Working Group, we have developed a working definition of creative research which centers inquiry while remaining as broad as possible:

Creative research is creative production that produces new knowledge through an interrogation/disruption of form vs. creative production that refines existing knowledge through an adaptation of convention. It is often characterized by innovation, sustained collaboration and inter/trans-disciplinary or hybrid praxis, challenging conventional rubrics of evaluation and assessment within traditional academic environments.

This is where Tisch can lead.

Artists are natural adapters and translators in the work of interpretation and meaning-making, so we are uniquely qualified to create NEW research paradigms along with appropriate and rigorous methods of assessment. At the same time, because of Tisch's unique position as a professional arts-training school within an R1 university, any consideration of "artistic" or "creative research" always references the rigorous standards of the traditional scholarship also produced here.

The long-term challenge is two-fold. Over the long-term, Tisch will continue to refine its evaluative processes that reward innovation, collaboration, inter/trans-disciplinary and hybrid praxis. At the same time, we must continue to incentivize faculty and student work that is visionary and transcends the obstacles of convention.

As the research nexus for Tisch, our responsibility is to support the Tisch community as it embraces these challenges and continues to educate the next generation of global arts citizens.

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences

A practical guide.

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: Policy Press

- Copyright year: 2015

- Audience: College/higher education;

- Main content: 224

- Published: April 10, 2015

- ISBN: 9781447320258

Search form

Creative methods, creative methods in research & community engagement.

This database of methods is intended to help action-researchers put creative inquiry and engagement methods to practical use. It provides a compendium of detailed methods, but is also meant to inspire users to adapt them for their context and create their own.

Creative methods engage participants outside the parameters of traditional qualitative data collection and analysis. They often include empathetic, artistic, narrative, or aesthetic expression as the basis for investigating, intervening, creating knowledge, and sharing information. Such methods are intended to evoke deeper research insights and richer or more nuanced interpretations. They can facilitate meaning making and highlight alternative types of knowledge and ways of knowing.

It is widely agreed that new ways of thinking and doing can create new constellations of possibilities for change. Thus, in our collective work towards more just, sustainable, and regenerative societies, creative methods can support transformative practices on multiple levels. For example, they can:

- support more inclusive engagements by making sure that a wide range of voices are heard and valued.

- spark disruptive ideas and imaginaries through lateral thinking and radical speculation

- evoke mental models by highlighting metaphors and narratives that are aligned with people’s deepest values.

What are creative methods?

In order to access or communicate information and knowledge not easily attainable through traditional methods, creative methods use:

- lateral & metaphorical thinking

- arts-based, aesthetic, or "maker” approaches

- storytelling/affective narratives (visual, verbal, or other)

The creative or artistic dimensions may be used during data collection, analysis, interpretation, and/or dissemination.

Why is Recoms focusing on creative methods?

The Recoms research network is focused on supporting vulnerable communities to become more resourceful and resilient by strengthening people’s capacity to adapt and transform in the face of social and ecological crises.

Generative forms of inquiry, a strong emphasis on inclusivity, and a commitment to co-production and action-learning (learning by doing) can all contribute to this goal.

Creative methods have the potential to help uncover and nourish the inherent resourcefulness and wisdom already existing amongst groups of people.

They can do this by creating the conditions to deepen reflexivity and openness to new perspectives and possibilities as well as draw greater attention to the process of knowledge creation as developed within specific social-ecological-cultural contexts.

Why use creative methods?

Support collaboration & connection.

- Engage diverse people with different styles of learning and participating

- Flatten hierarchies, encouraging all voices in the room (and sometimes outside the room!) to be heard and valued

- Expand spheres of empathy (i.e. for other humans, for non-humans, and for future generations)

- Co-create knowledge

Surface Inner-dimensions

- Uncover and make visible hidden elements of systems and structures

- Bring to light beliefs, values, worldviews & paradigms

- Reveal and engage with emotional and affective dimensions

- Acknowledge and give space to uncertainties

Spark fresh perspectives

- Disrupt habituated ways of thinking and doing

- Evoke cognitive frames that open new spaces of possibility (i.e. more than human perspectives, complexity thinking, expanded sense of time)

- Imagine new futures

- Inspire creative and innovative ideas and solutions

- Address complexity and support complexity thinking

Empower adaptation and transformation

- Creative practices can open new spaces of possibility, which can support new pathways of action.

- They can help people confront and process the realities of social-ecological crises, not just intellectually, but also emotionally and affectively.

- Creative practices can be used to access hidden layers of emotion and meaning and create context for people to surface unspoken issues or fears, which then leads to increased capacity for action.

Criteria for selection of methods

- Methods which have the potential to flatten tacit hierarchies and create space for diverse voices and methods in which all people can participate equally were prioritized.

- Most methods have both an inner focus (quiet solo work) and an outer focus (sharing and discussing) in order to energize people who think best alone and those who think best in dynamic interactions.

- Methods that target a range of learning and expressing styles. Different people will shine or feel empowered by different forms for reflection, analysis, and communication. For example, some people thrive in debate and linear analysis, others through visualization and visual communication, others through insights gained through creative/ lateral & metaphorical thinking.

- Methods selected are relatively simple, short, and can be used in a wide variety of contexts.

- Methods were designed to leave tangible (written or visual) records that can be useful for sharing insights with broader communities and for data collection and analysis.

Note: It is important to remember that not all people will like all methods, just as not all people like the standard “business as usual” format of brainstorming and planning meetings

What is Appreciative Inquiry?

Appreciative Inquiry (AI) was developed by David Cooperrider of Case Western University as a way to build on and strengthen what people are already doing well in groups, communities, or organizations. It starts with the premise that people will benefit from a strengths-based or affirmative approach, as opposed to a deficit-based approach, which emphasizes what is wrong or what needs to be fixed. AI assumes that each human system has a positive core of strengths and that the values, beliefs, and capabilities of the system when it’s at its best can be nurtured and expanded.

The AI framework offers a semi-structured process for creating a collective understanding of the groups positive core and using that as a basis for visioning and planning and acting. It consists of five phases: Define, Discover, Dream, Design, Destiny, all which are fed by the Positive Core of the process.

Appreciative Inquiry Framework

- Define: These methods help clarify the collective topic of inquiry or the scope or intention of work. Why are we doing this work? What is the purpose and what needs to be achieved?

- Discover: Methods in this category can help participants rediscover, remember, or uncover the group or community's successes, strengths, resources, and periods of excellence. The idea here is to appreciate and acknowledge the best of what already exists and what already works.

- Dream: These methods help people express their dreams for the future of a community or organization, based on strengths and past successes.

- Design: In this phase, dreams are refined and grounded and the group converges on a specific vision or visions.

- Destiny: These methods can help people creatively figure out a concrete path forward - how, in concrete terms, to embed new designs into the community, group, or organization.

- Positive Core: A cornerstone of AI is maintaining and feeding the underlying positive energy of the people involved with the project or initiative. These methods should help “excite, empower, and engage” participants.

Search Category Descriptions

When to Use

Warm-ups are intended to set the tone of the event, to engage people in the topic at hand, and align with and evoke the deeper values and principles of the group. They are an opportunity to start an event with coherence between goals, theory, and practice.

Generating Ideas

These methods can be used to generate many ideas from multiple perspectives. Often the wilder, the better, as diversity and far-flung imaginative ideas can provoke new and unexpected insights. It is important to be clear that one’s critical voice should be suspended in this generative stage, and saved for the converging, or decision making phase of the workshop.

The act of taking a structured pause to reflect and process input and information is often missing from collective engagements, which tend to leap straight from discussion to solutions or action. Giving time, space, and loose structure to periods of reflection throughout engagement processes can result in deeper and more transformative insights and commitments. New ideas or practices have a chance to root and disrupt habituated ways of thinking and doing.

Harvesting Results

During a workshop many different outputs emerge: ideas, insights, stories, key points, actions, accountabilities, resources needed, resources available, etc. A good harvesting method can capture these outputs and process to share with others, as a reminder for oneself, as a collective record, for future analysis, or to facilitate future action. The harvest should be designed to be integrated into the structure of the engagement, rather than as an add-on. Harvest methods can be fun and creative.

Making Decisions

These methods can be used to converge upon a plan of action, a narrower theme of inquiry, or other decisions. At this stage, the method should ensure that all voices are heard and valued, rather than defaulting to the loudest voice in the room.

Preparation

including materials and time

Can be done with a range of materials and preparation, depending on adaptation.

little to no advanced preparation.

some simple materials and preparation of slides and/or instructions.

require facilitator to gather materials, print documents, prepare graphics, do advanced research, etc.

Method Filter

- Follow us on social media

© RECOMS 2021. All rights Reserved.

- Research groups

- Latest Posts

- LSE Authors

- Choose a Book for Review

- Submit a Book for Review

- Bookshop Guides

Dr Helen Kara

March 26th, 2021.

Creative Research Methods – Writing the Second Edition

0 comments | 7 shares

Estimated reading time: 10 minutes

Helen Kara reflects on writing the second edition of her book, Creative Research Methods: A Practical Guide , following the publication of the first edition in 2015. In this feature essay, she explores the differences between the two editions and also discusses the processes of updating the content, changing the structure and title, submitting the proposal and receiving and responding to reviewer comments.

The first edition of Creative Research Methods , published in 2015, conceptualised the field under four headings. These were not mutually exclusive but provided a useful way to think and talk about creative methods: arts-based research; mixed-methods research; research using technology; and transformative research frameworks. Since then, work with mobile and sensory methods in particular, and embodied research in general, had expanded dramatically, meaning I needed to add embodied research as a fifth heading for the second edition. Also in the first edition, led by the literature, I had classified decolonising methods within transformative research frameworks. After publication I met some Indigenous researchers who taught me that the Indigenous research paradigm stands alone and predates the Euro-Western research paradigm, and that decolonising methods belong within the Indigenous paradigm. So I needed to correct that error. And I wanted to include more examples of work from the Global South.

I wrote a proposal on that basis which was reviewed by four very helpful people (if you were one of them: thank you!). They were all familiar with the first edition and most were positive, though one thought it might be too soon to write a second edition. One particularly useful point was that despite the four headings, the first edition gave much less weight to research using technology than to the other three – something that had completely escaped me. So I worked hard to rebalance that in the second edition, which led to a total restructure of the second part of the book. In the first edition, Chapters Five to Eight covered data gathering, data analysis, research reporting and presenting findings, respectively. In the second edition, each of these was split into two, to form Chapters Six to Thirteen: arts-based and embodied data gathering, using technology and mixing methods in data gathering and so on. I also added a new Chapter Three on transformative research frameworks and Indigenous research.

I was fascinated by the reviewers’ views of the audience for this book, from a list of options provided by the publisher. The only thing they all agreed on was that the audience would not include policymakers. Three agreed it would include academics, postgraduates and professional students. Two also suggested undergraduates and independent researchers, and one added methods teachers and academic researchers. I hear from readers in all of these categories apart from undergraduates, but I do hear from lecturers who use the book with undergraduates. When I wrote the first edition, I thought only doctoral students, early career researchers and maybe some doctoral supervisors would be interested. I am very glad to have been so wrong about that!

After some thought and discussions with my editor at Policy Press, I revised my proposal in May 2019 to suggest fifteen chapters instead of ten, and 100,000 words instead of 80,000. If I had written that sentence at the time, it might have occurred to me that 50 per cent more chapters would be unlikely to fit into 25 per cent more words. It didn’t – which meant that by September 2019 I needed to write a desperate email to my editor, begging for more words. Fortunately she was receptive and granted me an extra 7,000.

Another thing I didn’t foresee was just how much had been written on creative research methods, in one form or another, in the five years since I had put together the first edition. I spent hundreds of pounds on books, and downloaded dozens of journal articles to add to the dozens I already had in my ‘second edition’ folder (created when the first edition was published, to store all the information people kindly emailed and tweeted to me when they knew of my interest). In the inevitable writer’s trade-off between breadth and depth, I was always going to go for breadth, so it was important to reference heavily to help readers follow up their topics of interest. But references use up so many words … I was a professional academic copy-editor in a former life, and I’m good at distilling and condensing my own prose, but I can’t do anything to reduce the wordiness of references.

The first edition was called ‘ Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences ’. It should really have been ‘ Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences, Arts, and Humanities ’, but that was too long. Also, even the first edition contained several examples of creative methods from science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) disciplines. As I read for the second edition, I found more and more examples of creative methods from STEM disciplines, and enjoyed including them in the book. In February 2020 I was teaching creative research methods at Dublin City University to a group of doctoral students from right across the disciplines: engineering, law, business, sociology and so on. During our discussions I had a light-bulb moment and, while they were involved in doing an exercise, I fired off an email to my editor: for the second edition, could we drop the ‘in the social sciences’ part of the title? Within hours I had a positive reply.

Eventually I finished the manuscript and it was reviewed by three very helpful people (if you were one of them: thank you!). Again, they were very positive about the book, making some lovely comments: ‘It’s a model of accessible communication’ is one of my favourites. They also all read the manuscript very thoroughly and made some really useful points about structure, chapters, sections, paragraphs and even specific words. One made the point that ‘multi-modal’ is taking over from ‘mixed-methods’ for good reason, so I changed that in the text, and made a bunch of other revisions before handing the manuscript over to Policy Press with a sigh of relief.

The second edition does include more examples from the Global South, but not as many more as I would have liked. As I was reading for the second edition, I learned that in some countries in the Global South creative research methods are not yet acceptable in academia. I wrote about this in the introductory chapter, asking readers to pass on any good examples of creative research methods from countries or regions that are under-represented in my book. I haven’t received any yet, but I have more examples, and more contacts, through the more recent work I have done with Su-ming Khoo on researching in the age of COVID-19 . So I will definitely be able to improve this further in the third edition.

So I have written two second editions now, and they were very different experiences. The first was quite straightforward, the second was much more difficult than I anticipated. This makes it tricky to come up with a neat set of tips for others who may be planning their first second edition. The publisher’s proposal form will provide some guidance. I should say, though, that it’s definitely worth doing, because even when it’s complicated, producing a second edition is a lot less work than writing a whole new book!

Note: This feature essay gives the views of the author, and not the position of the LSE Review of Books blog, or of the London School of Economics.

Image Credit: Photo by Dstudio Bcn on Unsplash .

About the author

Dr Helen Kara has been an independent researcher since 1999, focusing on social care and health, partnership working and the third sector. She teaches and writes on research methods. Her most recent full-length book is Research Ethics in the Real World: Euro-Western and Indigenous Perspectives (Policy, 2018). She is also the author of the PhD Knowledge series of short e-books for doctoral students. Helen is an Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the University of Manchester, and a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences

Leave a Reply Cancel reply

Related posts.

Reading List: 8 Books on Indigenous Research Methods recommended by Helen Kara

July 26th, 2017.

Book Review: Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide

June 17th, 2015.

Twelve Top Tips for Writing an Academic Book Blurb

March 19th, 2020.

Book Review: Research Ethics in the Real World by Helen Kara

June 21st, 2019, subscribe via email.

Enter your email address to subscribe to this blog and receive notifications of new posts by email.

Email Address

This website uses cookies to ensure you get the best experience on our website. Without cookies your experience may not be seamless.

- Creative Research Methods in the Social Sciences: A Practical Guide

In this Book

- Kara, Helen

- Published by: Bristol University Press

Table of Contents

- Title Page, Copyright

- List of figures and tables

- Debts of gratitude

- pp. vii-viii

- How this book can help

- 1. Introducing creative research

- 2. Creative research methods in practice

- 3. Creative research methods and ethics

- 4. Creative thinking

- 5. Gathering data

- 6. Analysing data

- 7. Writing for research

- pp. 121-136

- 8. Presentation

- pp. 137-160

- 9. Dissemination, implementation and knowledge exchange

- pp. 161-178

- 10. Conclusion

- pp. 179-182

- pp. 183-212

- pp. 213-221

Additional Information

Project MUSE Mission

Project MUSE promotes the creation and dissemination of essential humanities and social science resources through collaboration with libraries, publishers, and scholars worldwide. Forged from a partnership between a university press and a library, Project MUSE is a trusted part of the academic and scholarly community it serves.

2715 North Charles Street Baltimore, Maryland, USA 21218

+1 (410) 516-6989 [email protected]

©2024 Project MUSE. Produced by Johns Hopkins University Press in collaboration with The Sheridan Libraries.

Now and Always, The Trusted Content Your Research Requires

Built on the Johns Hopkins University Campus

- Politics & Social Sciences

- Social Sciences

Enjoy fast, free delivery, exclusive deals, and award-winning movies & TV shows with Prime Try Prime and start saving today with fast, free delivery

Amazon Prime includes:

Fast, FREE Delivery is available to Prime members. To join, select "Try Amazon Prime and start saving today with Fast, FREE Delivery" below the Add to Cart button.

- Cardmembers earn 5% Back at Amazon.com with a Prime Credit Card.

- Unlimited Free Two-Day Delivery

- Streaming of thousands of movies and TV shows with limited ads on Prime Video.

- A Kindle book to borrow for free each month - with no due dates

- Listen to over 2 million songs and hundreds of playlists

- Unlimited photo storage with anywhere access

Important: Your credit card will NOT be charged when you start your free trial or if you cancel during the trial period. If you're happy with Amazon Prime, do nothing. At the end of the free trial, your membership will automatically upgrade to a monthly membership.

Buy new: .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $42.95 $ 42 . 95 FREE delivery Friday, June 7 Ships from: Amazon.com Sold by: Amazon.com

Return this item for free.

Free returns are available for the shipping address you chose. You can return the item for any reason in new and unused condition: no shipping charges

- Go to your orders and start the return

- Select your preferred free shipping option

- Drop off and leave!

Save with Used - Good .savingPriceOverride { color:#CC0C39!important; font-weight: 300!important; } .reinventMobileHeaderPrice { font-weight: 400; } #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPriceSavingsPercentageMargin, #apex_offerDisplay_mobile_feature_div .reinventPricePriceToPayMargin { margin-right: 4px; } $14.67 $ 14 . 67 $3.99 delivery June 10 - 14 Ships from: HPB-Red Sold by: HPB-Red

Download the free Kindle app and start reading Kindle books instantly on your smartphone, tablet, or computer - no Kindle device required .

Read instantly on your browser with Kindle for Web.

Using your mobile phone camera - scan the code below and download the Kindle app.

Image Unavailable

- To view this video download Flash Player

Follow the author

Creative research methods in the social sciences: A Practical Guide 1st Edition

There is a newer edition of this item:.

Purchase options and add-ons

- ISBN-10 1447316274

- ISBN-13 978-1447316275

- Edition 1st

- Publisher Policy Press

- Publication date April 10, 2015

- Language English

- Dimensions 6.77 x 0.53 x 9.45 inches

- Print length 232 pages

- See all details

Customers who viewed this item also viewed

Editorial Reviews

About the author, product details.

- Publisher : Policy Press; 1st edition (April 10, 2015)

- Language : English

- Paperback : 232 pages

- ISBN-10 : 1447316274

- ISBN-13 : 978-1447316275

- Item Weight : 14.4 ounces

- Dimensions : 6.77 x 0.53 x 9.45 inches

- #733 in Social Sciences Methodology

- #1,500 in Social Sciences Research

- #59,388 in Unknown

About the author

Helen Kara is a leading independent researcher, author, teacher and speaker specialising in creative research methods, radical research ethics, and creative academic writing. With over 25 years’ experience as an independent researcher Helen teaches doctoral students and staff at higher education institutions worldwide. She is a prolific academic author with over 25 titles; notably Creative Research Methods: A Practical Guide (2nd edn) and Research and Evaluation for Busy Students and Practitioners (3rd edn). Besides her regular blogs and videos, she also writes comics and fiction. Helen is a Visiting Fellow at the National University of Australia and a Fellow of the Academy of Social Sciences. In 2021, at the age of 56, she was diagnosed autistic. Her neurodiversity explains her lifelong fascination with, and ability to focus on, words, language and writing.

Customer reviews

Customer Reviews, including Product Star Ratings help customers to learn more about the product and decide whether it is the right product for them.

To calculate the overall star rating and percentage breakdown by star, we don’t use a simple average. Instead, our system considers things like how recent a review is and if the reviewer bought the item on Amazon. It also analyzed reviews to verify trustworthiness.

- Sort reviews by Top reviews Most recent Top reviews

Top reviews from the United States

Top reviews from other countries.

- Amazon Newsletter

- About Amazon

- Accessibility

- Sustainability

- Press Center

- Investor Relations

- Amazon Devices

- Amazon Science

- Sell on Amazon

- Sell apps on Amazon

- Supply to Amazon

- Protect & Build Your Brand

- Become an Affiliate

- Become a Delivery Driver

- Start a Package Delivery Business

- Advertise Your Products

- Self-Publish with Us

- Become an Amazon Hub Partner

- › See More Ways to Make Money

- Amazon Visa

- Amazon Store Card

- Amazon Secured Card

- Amazon Business Card

- Shop with Points

- Credit Card Marketplace

- Reload Your Balance

- Amazon Currency Converter

- Your Account

- Your Orders

- Shipping Rates & Policies

- Amazon Prime

- Returns & Replacements

- Manage Your Content and Devices

- Recalls and Product Safety Alerts

- Conditions of Use

- Privacy Notice

- Consumer Health Data Privacy Disclosure

- Your Ads Privacy Choices

Privacy Policy

Creative Research Methods Ltd does not use cookies or any kind of user tracking mechanisms on its website.

Information solicited from users (for example, for bursary applications or event bookings) is never used for advertising or promotion, and is never shared with third parties other than as necessary to fulfil your wish to apply for a bursary or take up a place at an event.

You can contact Creative Research Methods Ltd by email via [email protected]

Our postal address is:

The Office St Mary's Crescent Uttoxeter Staffordshire ST14 7BH United Kingdom

Terms & Conditions

Our contact email address for comments, complaints, and compliments is provided in our contact details .

Our business is organising and running events such as the International Creative Research Methods Conference, and academic and research writing retreats.

A place at one of our events is secured by payment, which must be made via this website, by card or by bank transfer. We cannot accept cheques. You have the right to cancel and receive a full refund within 15 days of making payment, including the day that payment is made. After that date no refunds will be available. You may transfer your place to another person and if you do so, you must notify us of that person’s name and email address.

Invoice payment terms are 30 days from date of invoice. If a 30-day invoice is not paid within 60 days, we will cancel the invoice, issue a credit note, and the place at the event will no longer be reserved for you. It is your responsibility to ensure that the invoice for your place is paid within this time frame.

How do you set the prices?

We work to keep prices as low as possible while making the events financially viable.

Are your prices negotiable?

Can you invoice my organisation for payment?

No, we can only take payment by card or bank transfer, in advance. This is because payment for invoices often needs to be chased up, sometimes via outsourced suppliers of invoice management with no named person to contact, and this can be very time consuming. We are a small organisation and we do not have enough person-power to do this unpaid work. Also we cannot afford the risk of invoices going unpaid.

Can I book Helen Kara to speak at or run an event at my organisation?

Yes, subject to her availability; she is usually booked up several months ahead. Send us an email saying what you want and when, and someone will get back to you, usually within five working days.

A Creative Research Methods project

"researchers who use creative methods are at risk of finding ways to express themselves, learn, and have fun. " ( kara 2020 :237), date: 9-10 september 2024, venue: the studio , 51 lever st, manchester m1 1fn.

Helen Kara founded this two-day hybrid conference to bring together people with an interest in creative research methods. Keynote speakers for 2024 are the renowned experts in creative practices Su-ming Khoo from the University of Galway, and Dawn Mannay of Cardiff University in Wales. There will also be presentations and activities in breakout rooms, and scope for going out into the city to try creative outdoor methods.

Conference Programme

We are delighted to bring you the our programme for 2024 - this may change slightly between now and the conference, so please make sure you download the latest version by CLICKING HERE . It was last updated on April 9th 2024

If you will be attending online and would like to see the online-only programme, you can download it by CLICKING HERE . This document was last updated on April 9th 2024

If you would like to see more details of the contributions to the conference, you can download those by CLICKING HERE . This document was last updated on April 19th 2024

Registration and Tickets

Ticket prices are in five categories. These are:

In-person prices include plentiful drinks, snacks, and lunches at the conference, and a choice of four or five activities in each session. The in-person prices do not include access to recordings of the online sessions; that access can be purchased for an extra £75.

The Online price includes a choice of two activities in most sessions, plus one extra online-only session, and access to recordings of all the live-streamed sessions for a calendar month after we get them uploaded in the autumn.

Unfortunately we cannot offer childcare, but babies and breastfeeding are welcome.

Attending the Conference

Our conference registrations are being handled by our partner, NomadIT. To register for our conference, please click the link below to go to the NomadIT signup page and create an account.

Once you have registered, you will receive an invoice which you can pay by bank transfer or by card - please see our payment page . If possible we would prefer to receive payment by bank transfer.

Zoom links for online attendees will be sent by email in advance of the conference. If you have not received your link by noon BST Saturday 7th September, please email [email protected] .

If you are attending in person, please come to the venue at 10 am on Monday 9 September for registration.

Helping Others To Attend

We are also asking those who can afford a little extra to make adonation. We will use these donations to fund bursaries which will enable people who need financial help to receive a free online place. If you would like to make a donation by bank transfer, please see our payment page for details.

If you would like to make a donation payment by card, please click the button below or scan the QR code to go to our Donations page:

Donations paid by card will be processed via the Stripe payment gateway.

Some bursaries for in-person attendance will be available thanks to the generosity of the UK's National Centre for Research Methods . Other bursaries for online and in-person attendance will be available, funded by donations. If you would like to apply for a bursary please visit our Bursary page:

We are hugely grateful to our sponsors for 2024:

Watch the Keynotes from 2023!

Enormous thanks to all who came to our 2023 conference, which was a stunning success. Our two keynote speakers delivered wonderful sessions, which are now available on YouTube:

Pam Burnard: Performing a Rebel Yell: Doing Rebellious Research In and Beyond the Academy

Caroline Lenette: The Importance of Being Disruptive: On Decolonising Creative Research Methods

If you would rather read than watch, there are blog posts by Helen Kara , Dawn Wink and Victoria Bartle .

Conference hashtag: #ICRMC

Privacy Policy - Contact Us - Terms and Conditions - FAQ

Website copyright © Creative Technology (MicroDesign) Ltd 2024

Research Methodologies for the Creative Arts & Humanities: Practice-based & practice-led research

Practice-based & practice-led research.

Known by a variety of terms, practice-led research is a conceptual framework that allows a researcher to incorporate their creative practice, creative methods and creative output into the research design and as a part of the research output.

Smith and Dean note that practice-led research arises out of two related ideas. Firstly, "that creative work in itself is a form of research and generates detectable research outputs" ( 2009, p5 ). The product of creative work itself contributes to the outcomes of a research process and contributes to the answer of a research question. Secondly, "creative practice -- the training and specialised knowledge that creative practitioners have and the processes they engage in when they are making art -- can lead to specialised research insights which can then be generalised and written up as research" ( 2009, p5 ). Smith and Dean's point here is that the content and processes of a creative practice generate knowledge and innovations that are different to, but complementary with, other research styles and methods. Practice-led research projects are undertaken across all creative disciplines and, as a result, the approach is very flexible in its implementation able to incorporate a variety of methodologies and methods within its bounds.

Most commonly, a practice-led research project consists of two components: a creative output and a text component, commonly referred to as an exegesis . The two components are not independent, but interact and work together to address the research question. The ECU guidelines for examiners states that the practice-led approach to research is

... based upon the perspective that creative art practices are alternative forms of knowledge embedded in investigation processes and methodologies of the various disciplines of performance … the visual and audio arts, design and creative writing ( "Guidelines and Examination Report for Examination of Doctor of Philosophy theses in creative research disciplines," para. 1 ).

A helpful way to understand this is to think of practice-led research as an approach that allows you to incorporate your creative practices into the research, legitimises the knowledge they reveal and endorses the methodologies, methods and research tools that are characteristic of your discipline.

Additional advice and guidance on the nature and implementation of a practice-led research project may be sought from your supervisors and from the research consultants .

- Boyes, E. Masquerade of the feminine (2006)

- Clarke, R. What feels true? (2012)

- Ellis, S. Indelible (2005)

- Grocott, L. Design research & reflective practice (2010)

- Hicks, T. Path to abstraction (2011)

- Mafe, D. Rephrasing voice (2009)

- Noon, D. The pink divide (2012)

- Wilkinson, T. Uncertain surrenders (2012)

ECU Library Resources - Practice-Based/ Practice-Led Research

- Art practice as research : inquiry in visual arts

- Art practice in a digital culture

- Artistic practice as research in music : theory, criticism, practice

- Creative research

- Design research through practice : from the lab, field, and showroom

- Live research : methods of practice-led inquiry in performance

- Method meets art : arts-based research practice

- Mapping landscapes for performance as research

- Thinking through practice: art as research in the academy

- Digital research in the arts and humanities

Further Reading

- Practice Based Research: A Guide

- The practical implications of applying a theory of practice based research: a case study

- Evaluating quality practice - led research: still a moving target?

- Creative and practice-led research: current status, future plans

- Developing a Research Procedures Programme for Artists & Designers

- Inquiry through Practice: developing appropriate research strategies

- Illuminating the Exegesis

- A Manifesto for Performative Research.

- The art object does not embody a form of knowledge

- From Practice to the Page: Multi-Disciplinary Understandings of the Written Component of Practice-Led Studies

- Scholarly design as a paradigm for practice-based research

- << Previous: Positivism

- Next: Qualitative research >>

- Action Research

- Case studies

- Constructivism

- Constructivist grounded theory

- Content analysis

- Critical discourse analysis

- Ethnographic research

- Focus groups research

- Grounded theory research

- Historical research

- Longitudinal analysis

- Life histories/ autobiographies

- Media Analysis

- Mixed methodology

- Narrative inquiry research method

- Other related creative arts research methodologies

- Participant observation research

- Practice-based & practice-led research

- Qualitative research

- Quasi-experimental design

- Social constructivism

- Survey research

- Usability studies

- Theses, Books & eBooks

- Subject Headings

- Academic Skills & Research Writing

- Last Updated: May 23, 2024 10:35 AM

- URL: https://ecu.au.libguides.com/research-methodologies-creative-arts-humanities

Edith Cowan University acknowledges and respects the Noongar people, who are the traditional custodians of the land upon which its campuses stand and its programs operate. In particular ECU pays its respects to the Elders, past and present, of the Noongar people, and embrace their culture, wisdom and knowledge.

Creative research methods: the story so far

Creative research methods are often treated as though they are new, yet people have always used creative ways of solving problems. We say, ‘necessity is the mother of invention,’ and indeed all research methods were invented once. Some research texts write of methods as if they are static and fixed, but this is far from the case.

Creativity is closely linked with problem-solving and with uncertainty, both key elements of research. Any research project is made up of hundreds or thousands of decisions and each decision holds space for creativity. Perhaps more surprisingly, there is also evidence of a close relationship between ethical decision-making and creative thinking 1 .

So all research is creative. We talk about ‘doing’ research as if it was like doing the dishes, but I would argue that we make research as if it was like making a tapestry. Having said that, some research projects are more creative than others. Creativity in research can be stifled by regulations, constraints of time and budget, lack of knowledge, skill, or courage. Some of these factors are easier to influence than others, and perhaps the easiest is the knowledge factor. I have always used creative methods in my own research, wherever I was able to do so and it was appropriate for the work in hand. This is a crucial point: methods must flow from the research question, and should be those most likely to help provide an answer. Newly learned methods may seem very tempting to try out, but it is never good practice to be seduced by an attractive young method when an older, more familiar one would serve you better.

In early 2012 I was considering how to address a particularly complex research question, and I began to think I might not have enough tools in my methodology box. I went looking online for a book on creative research methods. Surely, I thought, someone must have written one by now. It would be really useful... I searched and searched, until a realisation crept over my skin and into my brain: if I wanted to read that book, I was going to have to write it first.

As usual, writing involved reading. Lots of reading. I read over 800 reports of research, in journals and books; about 500 made it into the book, and just over 100 were showcased as examples of creative research. As I read, I slowly came to understand that creative research methods could be conceptualised under four broad headings: arts-based methods, research using technology, mixed-methods research, and transformative research frameworks.

Arts-based methods include visual and performative arts, creative writing, music, textile arts and crafts – pretty much any art form can be used in the service of research. In fact, the arts and research are closely linked, as artists of all kinds use research in support of their work. And arts-based methods, like all creative methods, apply to both quantitative and qualitative research. One of my favourite examples is that of a mathematician researching hyperbolic geometry, i.e. the geometry of frilly things like lettuce and jellyfish. Male mathematicians had tried and failed to model this for centuries, and it wasn’t until the American mathematician Daina Taimina was musing on the problem while crafting that she realised it could be done using crochet. I recommend her TED talk.

As researchers, we all use technology, and have done for centuries. But technological advances offer new opportunities. We can now use apps, mash-ups, data visualisations, APIs – though while this proliferation excites some people, it is daunting for others. Some fear that technology will change their research practice, and it will, though this seems to me not a cause for fear, but for care and thought.

Mixed methods is perhaps the most well established area, with dedicated books and journals. But the potential – and the risks – of mixing methods are still not understood by most researchers. People often think in terms of gathering data using both quantitative and qualitative methods, but there is so much more scope for mixing, from using different theoretical perspectives to inform the same piece of research to multi-media presentation and dissemination.

Transformative research frameworks include participatory, decolonising, activist and community-based research. These are frameworks designed to reduce power imbalances within the research process and, ideally, to affect structural inequalities more widely. They are challenging to implement, requiring more time and other resources than more traditional frameworks for research, but when used well they can indeed transform aspects of our society for the better.

Of course these four areas are not mutually exclusive. There is exemplary research using them all, such as the work of Ashlee Cunsolo Willox and her colleagues in Canada 2 . They worked within a decolonising community-based framework to investigate the effects of climate change on Inuit people in Rigolet, a small settlement in northern Labrador. The method was digital storytelling, developed in week-long workshops which involved discussion, concept maps, interviews, art, music and photography.

Creative research methods, particularly en masse, can seem quite intimidating. Not every researcher can – or wants to – plan their project diagramatically, gather data from social media, conduct metaphor or life course analysis, and disseminate through a multi-media arts installation. But there are two key take-away points. First, any non-research skills you have may be useful in the service of research. Second, if you want to expand your methodological repertoire, you can do so one step at a time.

1 Mumford, D. et al. (2010) Creativity and Ethics: The Relationship of Creative and Ethical Problem-Solving. Creativity Research Journal, 22:1, 74-89

2 Willox, A. C. et al. (2012) Storytelling in a digital age : digital storytelling as an emerging narrative method for preserving and promoting indigenous oral wisdom. Qualitative Research, 13:2, 127-147

Effective schematic design phase in design process

- Open access

- Published: 29 May 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Samira Mohamed Ahmed Abdullah ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2523-0406 1 , 2 ,

- Naila Mohamed Farid Toulan 1 &

- Ayman Abdel-Hamid Amen 2

49 Accesses

Explore all metrics

Design thinking is a way to create solid designs that responds to design problems and solve it in a creative and suitable way. However, it is not widely recognized in architectural education pedagogy in Egypt for undergraduate. Despite being very efficient in several business avenues but not in architectural pedagogy. So, this paper aims to spot the light on design thinking and the possibility of its usage in design process to help students have a successful architectural project that solves the design problems and face the site challenges through the use of visualization design thinking tool. Where students face a challenge in translating the verbal language of their collected data in the research phase to the architectural language in the schematic phase. There is a recognized gap between the research students perform in the beginning of design project and the schematic designs that students deliver. The study proposes the possibility of using visualization as a tool for design thinking to have a sufficient and successful schematic design phase. The study will explain how students could apply design thinking in architectural design to benefit from their research phase in their schematic design. Moreover, come up with solutions and variable ideas using the tools of deign thinking as a way for helping in delivering design problem solution and have a more effective schematic design. At the end of the research paper the study concludes how the students can use visualization tool to translate the verbal language to architectural language and the possibility for using design thinking. That to help students realize the importance of analysis phase in synthesis. The research follows descriptive method and quantitative analysis where first the descriptive method is used in illustrating design process and design thinking. Then the quantitative analysis in the experiment is done followed by a survey to prove research problem and help in proposing the solution.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

To lead a successful architectural design the designer will need to go on and deal with very complicated and complex challenges that will face him during his design process. This requires the designer to be flexible and to have the required design skills and technical knowledge and sufficient information to go on with a successful project. From the most important skills that the designer must have is the creative thinking. Whatever faces the designer there must be that soul of having the power to think and identify the problem to come up with a solution. As, explained by Ghonim (Ghonim, 2016 ) design is an activity that requires to think out of the box and have creative ideas that create new outputs. Design stimulates the human brain to produce creative ideas and be more productive.

Students in the architectural design studio often grapple with a significant challenge which is effectively connecting their research endeavors with the practical application of findings in schematic designs. One central issue lies in the seamless integration of theoretical knowledge acquired during research into tangible design solutions. Developing the skills to translate abstract concepts into actionable design elements proves to be a hurdle for many students. The struggle extends to understanding the direct influence of research outcomes on design decisions, leading to a potential disconnect between theory and practice. Here lies the importance of performing this study.

Literature review

- Design thinking

Design thinking is seen as a way to solve problems that face architects in their designs and helps in finding creative solutions (Goldschmidt & Rodgers, 2013 ). Willemien Visser mentioned that design thinking is for designing activities in a cognitive way that designers use and apply during their design process. So, to be able to apply design thinking, there are main steps that designers apply to achieve their target for solving design problems which are (Tymkiewicz & Bielak-Zasadzka, 2016 ):

Designers need to first identify the problem that needs solution.

They need to identify the user's needs, which will be mainly through surveys or through the client if he is the direct user.

After that, the designer needs to brainstorm his ideas that should solve the design problem

Then comes the phase to evaluate the ideas and put them into practice to get the best solution out of them, which in return gives the door for using design thinking and helps in answering the research question.

There are two approaches for design thinking discussed as follows:

Vertical design thinking

Vertical thinking is mainly concerned with evidence, proves and for generating ideas that result from analysis and information gathering (Hernandez & Varkey, 2008 ). The designer in this approach puts an assumption or what is called as an initial assumption upon which he builds the design and take his decisions. This initial assumption or hypothesis is fixed and is known by the fixation effect (Eissa, 2019 ).

In this type the designer goes deeply and adheres to his solution and tries by all means to prove and validate it. He refuses going to other solutions or to even generate other new ideas than his initial assumption or idea. He tries making it work by all means which in return shows the weakness of this approach as this kind of thinking and rigidity is not acceptable in design process. (Goldschmidt & Rodgers, 2013 ).

Lateral design thinking

This approach is the opposite of vertical thinking. Here the designer tries to generate and come up with many ideas and creative solutions. The designer in this approach never adheres to that one single initial assumption, as there is always room for other ideas and alternatives. Which is known as a breaking out from the initial assumption, which is also known as frame of reference (FR). that opens the door for creativity in the design process (Akin & Akin, 1996 ).

When the time comes for coming up with solutions for design problem the design maps show up. That helps the designer throughout his journey to go through the phases for design solution. Although the vertical thinking is only concerned with adhering to one solution and refuses other alternatives, when thinking deeply it is found that the analysis and synthesis processes are mainly relying on this type of thinking (Goldschmidt & Rodgers, 2013 ). Markus/Maver design map is a good example for that as this kind of map mainly discusses the design process and its phases. As Lawson mentioned in his book “how designers think” this map takes the design process starting from analysis phase and briefing it then goes to synthesis phase following it with Evaluation then decision making (Lawson, 2005 ).

In this design map the first step as mentioned before is data gathering then analysis. through that the designer understands the requirements and needs of the client and identify his program and the understands the design problem (Lawson, 2005 ). That requires producing design solution through which the designer identify objectives and targets. After the analysis that in which the problem is clearly defined and the objectives and targets are set, comes the synthesis phase. that solves the design problem through an architectural drawings solution (Nazidizaji et al., 2015 ). At the end the designer will have the solution presented in architectural drawings that are ready for the evaluation phase, were it must meet the needs and objectives that accomplish the targets that were set in the analysis phase.

However the design process is always found to be backward and forward as it is repeated in iterations for the reason of modifying. This will cause returning back to the synthesis phase where the design should be modified. That in return may require more analysis as there will be a change in the decisions taken in the design (Eissa, 2019 ).

Design thinking tools

Design thinking tools are techniques and methods employed in the design thinking process to encourage creativity, collaboration, and user-centered problem-solving. Design thinking tools can be effectively integrated into the architectural design process to enhance creativity, collaboration, and problem-solving. Integrating design thinking tools into the architectural design process encourages a holistic and user-centric approach. It helps architects generate innovative solutions, consider diverse perspectives, and refine designs based on user experiences and feedback (Plattner et al., 2011 ).

Visualization plays a pivotal role in the architectural design process, serving as a potent design thinking tool that aids architects in conveying ideas, exploring possibilities, and refining concepts. According to Cross, visualization is integral to the design thinking approach, allowing designers to externalize their thoughts and collaborate effectively (Cross, 2011 ).

In the context of architectural design, Moggridge emphasizes the power of visualization in translating abstract ideas into tangible representations (Moggridge, 2006 ). From early sketches and hand-drawn diagrams to sophisticated digital models using tools like SketchUp or Revit, architects leverage visualization to communicate spatial relationships, materiality, and the experiential qualities of spaces.

Another tool for design thinking is journey mapping which is valuable in understanding and expressing the user experience within the designed spaces. Brown suggests that journey mapping is particularly effective in uncovering hidden aspects of the user experience (Brown, 2008 ). By mapping each stage of a user's interaction with a space, architects can identify critical touchpoints and areas where improvements or enhancements are needed. Journey mapping involves creating visual representations of users' experiences as they navigate and engage with different elements of a space. This technique is emphasized in the human-centered design processes outlined by IDEO, where architects use journey maps to gain insights into user behaviors, pain points, and moments of delight.

Mind mapping is a versatile and creative design thinking tool that finds practical application in the architectural design process. It serves as a visual technique to organize thoughts, generate ideas, and explore relationships among various design elements. According to Cross, mind mapping is an effective mean for designers to externalize and structure their thinking (Cross, 2011 ).

Role of design thinking in design process

The designer's brain acts as an archive where he stores information and pictures of what he collects and analyzes. Therefore, thinking in its basic form is a mechanism processed in the designer’s mind relying on the information gathered and pictures he has seen (Cho, 2017 ). However, basic thinking does not acquire much effort, but it is considered as an important part of the thinking process done in the design process. As all information is proceeded in this stage from that collected in research, gained through lifetime experience and from designer's cultural background. Therefore, it can be said that this fundamental and initial step of thinking can lead to coming up with a solution, however it is not final but accepted. (Taneri & Dogan, 2021 ).

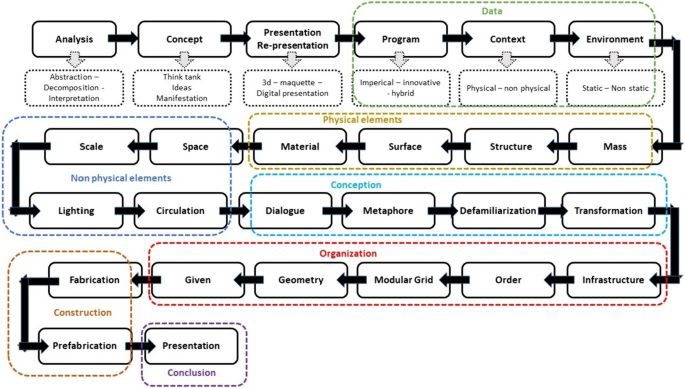

So, Design thinking can be involved in all design processes from problem solving to decision making as follows and shown in Fig. 1 (Lawson, 2005 ):

Problem solving in this step the problem must be clearly defined and identified. from the information collected in research. That’s to find out how to respond to the problem reasons and solve it in a way that responds to the needs and requirements of the project. Which will result in finding creative solutions and ideas for different solutions.

Design : this part includes the trial of conducting a design solution and proceeding it in a visual form and so developing while in process of designing self-criteria for evaluation before finishing the work.

Decision making here the designer has to come up with the previously generated design solutions and judge them visually and see their effect on the final solution however, their decision shouldn’t rely on personal taste.

The design process where design thinking can be involved, Source : Lawson (2005)

- Design process

The design process that Darke wrote about is considered to be the primary generator. She said that conjecture analysis can replace analysis and synthesis. She illustrated that by saying that the primary generator is a group of related ideas that helps in generating the solution (Darke, 1979 ). So, it helps the architect to focus on a group of objectives to define and know the starting point for his design (Smith & Schank Smith, 2014 ).

However, Schön gave another practice for design process, which he named as the reflective practitioner (Schön, 2017 ). He explained the RF as a reflective practice through it architects with experience are aware of the knowledge and the past experiences they gained from different projects and what they learnt from it (Daalhuizen et al., 2014 ). Besides what architects face from forward and backward in the process as they frame and reframe the design problem more and more again which in return affects the design decisions (Schön, 2017 ).

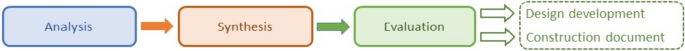

However, the design process is known for its main 4 phases that any architect must pass through to have a successful project at the end. They must be done with specific arrangement and relate to each other. These four phases are analysis, synthesis & evaluation (which is divided into (design development and construction documentation)) (Smith & Schank Smith, 2014 ) as shown in Fig. 2 and stated as follows:

First : The research phase (the analysis phase) is the first stage where data is collected. Everything about site is known and clear. Besides identifying and understanding the design problem and challenges (Abowardah, 2016 ). The designer in this stage determines the problem and know the goals which in turn requires to state clear objectives. Therefore, the methodology is set to achieve the goals to come up with a good design solution that responds to the design problem (Ulug, 2010 ).

Second : synthesis phase in this stage the designer usually comes up with solutions for the design problem and where ideas are translated to sketches. The designer usually starts to use the conceptual approach to state his idea for the solution (Daalhuizen et al., 2014 ). This stage is considered to be the problem-solving phase in an architectural language.

Third : the design development is where the designer starts to refine his drawings. The ideas start to take a clear and more defined shape in serving the solution in a proper architectural language(Ulug, 2010 ). In this stage the designer starts to evaluate and see clearly his design and how it responds to the design problem.

Fourth : The construction documents are more accurate than the previous. its where the location, dimensions, materials, sections, elevations and all other required building specifications are presented.

Design process, Source: Smith and Schank (2014)

Design learning in design process

Understanding how students act and go about their architectural design work in design studios is important for making architectural education better. Recent studies have investigated this in detail, giving us useful ideas about how to teach and create a good learning environment in design studios. These studies focused on different parts of the design process, including the early design stage. They checked how things like doing research, different ways of learning, and using technology affect how well students do (Hettithanthri et al., Nov. 2023 ).

The Learning by Design method lets students dive into designing and suggesting scientific investigations in a stronger way. However, many design approaches usually start with giving a specific design challenge. This can limit students from starting with their own questions that are worth investigating scientifically (Mehalik et al., 2008 ). As mentioned by Mehalik, Doppelt, and Schunn the system design-based approach is good for helping students learn design better. As, they learn to answer the questions that most of them ask themselves at the beginning, which is “why do I need to do this or why do I need to know this”. So, this helps students to understand their needs in the design and understand better how to deliver a better design (Mehalik et al., 2008 ). As mentioned by Gómez Puente that Design based learning DBL is an educational approach that helps in generating innovative solutions. So, through using it educators can help their students in the learning process to gain domain specific knowledge and the thinking activities relevant to the purpose of the solution (Gómez Puente et al., 2013 ).

Many studies have investigated how different ways of approaching design impact how well students do in their studies. In one study, they found two main ways students go about it: one where they focus on the big idea (concept-driven), and another where they use research a lot (research-driven) (Demirbaş & Demirkan, 2003 ). The research-driven way, which involves clear steps and guided exploration, led to better results for the students in the study. This suggests that having a clear plan in the design studio can help students handle the challenges of the design process and do better in their studies. Research has consistently highlighted the challenge of seamlessly integrating research findings into schematic designs within the architectural education context (Hosny et al., 2023 ). The transition from the analytical phase, where research is conducted, to the creative synthesis of design solutions can be a complex process.

Previous researchers have also investigated how using technology in the design process affects students. One study pointed out that bringing in digital tools and software during design can make students better at imagining and showing their ideas (Mirmoradi, 2023 ). This is especially important in the early design stages when clearly explaining spatial ideas is crucial. Even with all the progress in technology and how educators teach, students continue to find it hard to turn their thoughts from words into architectural drawings. This difficulty happens because design ideas are often abstract, demanding good technical skills, and there are challenges in expressing these ideas clearly through pictures (Nabih & Hosney, 2022 ). As a recurrent issue faced by students is the translation of verbal ideas into visual representations. This challenge arises as students struggle to articulate their conceptual understanding verbally and then face difficulties in transforming these ideas into architectural drawings.

Demirkan highlighted how it's crucial to blend research and critical thinking with the usual design techniques (Demirbaş & Demirkan, 2003 ). This method, shaped by research, urges students to dive deep into analysis, consider various viewpoints, and create inventive solutions. When research becomes part of the design process, educators can shape students into architects with a broad skill set, ready to make meaningful contributions to their field. The balance between creativity and practicality emerges as a central theme in the architectural design process. Some students may prioritize aesthetic aspects over functional requirements, leading to designs that lack practical viability.

Schematic design phase

Schematic design is the phase where the designer starts to translate his thoughts and ideas into sketches. It is where the program turns into the architectural language. The designer chooses the conceptual design approach to approach his design (AIA, 2007 ).

Major variables affecting design

In this stage, the designer starts to deal with the design problem in practice. Therefore, there are important factors that affects design process and decision making for design solution that needs to be taken into consideration stated as follows (AIA, 2007 ):

Program : The first factor that will affect the project is the program the client requires to be applied to his project. Usually, the program highly affects the spaces and the function. The designer will have to set his objectives according to the project program, as every program is unique to a specific project.

Codes and Regulations : When going deeply into design and starting to take action the designer will have to put in mind a very important factor that would simply destroy the whole project when it comes to reality. This factor most important factor is codes and regulations that simply supports safety and minimal land use (Djabarouti & O’Flaherty, 2018 ). The designer must follow the code and obey the regulations. For every country and even every area, there are codes and regulations that most designers consider as determinant in design.

Site : Then comes the site of the project, which has a great effect on the influence of the building design. There are physical factors in site, which will affect the design decisions like the topography, size and the geographical technical issues that will form challenges. There also could be any existing structure or some important environmental factors that should be taken into consideration. It is also very important to give a great attention to the surrounding environment. The context should have a great impact on the design’s identity. As any other built structure should feel homogenous with the other built environment. It will affect the form, concept, color and material (Daalhuizen et al., 2014 ). Most of projects requires dealing with existing structures that should be combined with the project.

Building Technology : Building technology is important to put into consideration when going with building design. The designer should respect the available structure system and the budget that will constrain the technology. Which may affect his idea if it is something related to structure and solving a problem related with area and size. However, every function or module for a specific building should have a criterion such as hotel is different from a theater or an office building (AIA, 2007 ).

Primary steps in schematic design

Despite constrains and factors mentioned above that the designer faces in the schematic phase, he would go through primary and initial steps that should include a fixed process, That is illustrated as follows (Djabarouti & O’Flaherty, 2018 ):

Analysis : which results the identification of the design problem

Synthesis : it’s the form of transferring the analysis into conceptual idea and proposing some solutions and setting objectives to achieve goals

Refinement : here the concept and idea is refined and the design solution is much clear

Documentation : the architectural project is in the stage where the architectural drawings are ready to be delivered.

Design thinking effect on schematic design phase

Design thinking can be illustrated as the knowledge that is understood and gained through which the designer will be able to understand the design problem. Then he will be able to think of the solution in a more reasonable way. That will result in a solution for the design problem that fulfils all the objectives set (Tymkiewicz & Bielak-Zasadzka, 2016 ).That will help in answering the research question RQ in return. Therefore, for the design thinking to take place there should be three steps to be done illustrated as follows:

Analyzing : the first and initial step is helping students to translate their ideas into drawings and visuals. In addition, it is very important to put assumptions at the beginning about the design problem and to classify all the collected data. Then they need to learn to know the objectives and know how to come up with ideas to solve problems. So, it's important to build upon old designs and always to develop ideas regularly (Lawson, 2005 ).

Criticizing : it is very important for designers and students at the very beginning to know how to criticize their works. The work needs to be assessed by its creator even before another peer or educator assessment (Mahmoodi, 2001 ). So, this will help in developing the skill to find solutions and develop it. Therefore, it will make it easy to judge and evaluate the solution. However, students still cannot do this perfectly as for the lake of qualifications compared to a skill architect.

Comparing : after that comes the comparison as the student or the designer needs to develop the skill of identifying reasonable solutions that responds positively with the design problem and solves it. That to be able to measure the success of the chosen solution. This will enable them to identify their thinking process.

However along with design thinking comes creative thinking that was proposed by Mahmoudi (Mahmoodi, 2001 ) which is mainly related to Visualization through the initial thinking and visuals that the designer develop in mind while subjected to design problem in the design process and how he deals with it which will help in answering the RQ in return. However, creative thinking is like design thinking in relation to identifying the problem and coming up with the solution. It differs in steps as it includes synthesis, elaborating and imagining in the design process. That are illustrated as follows (Cho, 2017 ):

Synthesizing : In this step, the student will need to be introduced to design types and thus know how to implement them that will in turn help them to generate solutions. When doing this it will be easy for students to apply the design strategy for the selected type to test the design idea.

Elaborating : students need to learn not to stuck to their initial ideas and develop them. Here comes the second step of elaboration. In this step, the student should be able to expand his thoughts and modify the basic ideas. This will enable the student to understand better the ideas of others.

Imagining : finally, students have to imagine the response to the design problem. That has to come up with the solution. As it affect the problem and project.

Guilfords’ thinking factors

In the realm of creativity and cognitive psychology, Dr. J.P. Guilford's groundbreaking work on the Structure of Intellect introduced a comprehensive model that identified key dimensions of human intelligence. Among these, four crucial factors: flexibility, originality, fluency, and elaboration, emerged as fundamental elements in understanding and assessing creative thinking.